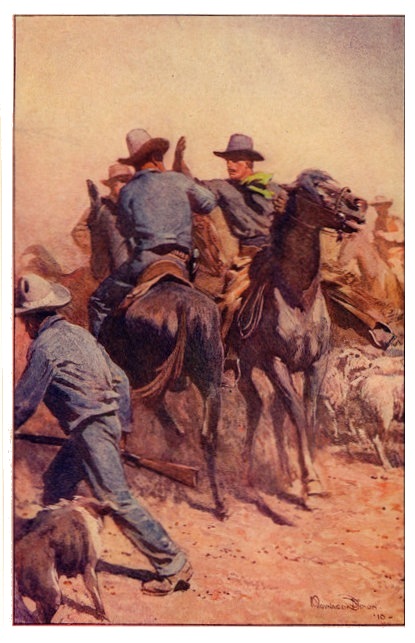

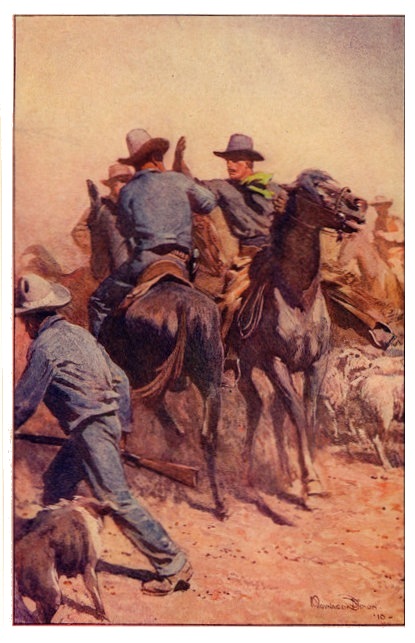

“I never saw a sheepman yet that would fight, but you’ve got to”

Title: Hidden Water

Author: Dane Coolidge

Illustrator: Maynard Dixon

Release date: August 9, 2009 [eBook #29642]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

“I never saw a sheepman yet that would fight, but you’ve got to”

HIDDEN WATER

By DANE COOLIDGE

With Four Illustrations in Color

By MAYNARD DIXON

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

COPYRIGHT

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1910

Published October 29, 1910

Second Edition, December 3, 1910

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London, England

All rights reserved

| ”I never saw a sheepman yet that would fight, but you’ve got to” | Frontispiece |

| “Put up them guns, you gawky fools! This man ain’t going to eat ye!” | 177 |

| “No!” said Kitty, “you do not love me” | 287 |

| Threw the sand full in his face | 462 |

After many long, brooding days of sunshine, when the clean-cut mountains gleamed brilliantly against the sky and the grama grass curled slowly on its stem, the rain wind rose up suddenly out of Papaguería and swooped down upon the desolate town of Bender, whirling a cloud of dust before it; and the inhabitants, man and horse, took to cover. New-born clouds, rushing out of the ruck of flying dirt, cast a cold, damp shadow upon the earth and hurried past; white-crested thunder-caps, piling-up above the Four Peaks, swept resolutely down to meet them; and the storm wind, laden with the smell of greasewood and wetted alkali, lashed the gaunt desert bushes mercilessly as it howled across the plain. Striking the town it jumped wickedly against the old Hotel Bender, where most of the male population had taken shelter, buffeting its false front until the glasses tinkled and the bar mirrors swayed dizzily from their 12 moorings. Then with a sudden thunder on the tin roof the flood came down, and Black Tex set up the drinks.

It was a tall cowman just down from the Peaks who ordered the round, and so all-embracing was his good humor that he bid every one in the room drink with him, even a sheepman. Broad-faced and huge, with four months’ growth of hair and a thirst of the same duration, he stood at the end of the bar, smiling radiantly, one sun-blackened hand toying with the empty glass.

“Come up, fellers,” he said, waving the other in invitation, “and drink to Arizona. With a little more rain and good society she’d be a holy wonder, as the Texas land boomer says down in hell.” They came up willingly, cowpunchers and sheepmen, train hands, prospectors, and the saloon bums that Black Tex kept about to blow such ready spenders as he, whenever they came to town. With a practised jolt of the bottle Tex passed down the line, filling each heavy tumbler to the brim; he poured a thin one for himself and beckoned in his roustabout to swell the count––but still there was an empty glass. There was one man over in the corner who had declined to drink. He sat at a disused card table studiously thumbing over an old magazine, and as he raised his dram the barkeeper glowered at him intolerantly.

“Well,” said the big cowboy, reaching for his liquor, “here’s how––and may she rain for a week!” He shoved back his high black sombrero as he spoke, but before he signalled the toast his eye caught the sidelong glance of Black Tex, and he too noticed the little man in the corner.

“What’s the matter?” he inquired, leaning over toward Tex and jerking his thumb dubiously at the corner, and as the barkeeper scowled and shrugged his shoulders he set down his glass and stared.

The stranger was a small man, for Arizona, and his delicate hands were almost as white as a woman’s; but the lines in his face were graven deep, without effeminacy, and his slender neck was muscled like a wrestler’s. In dress he was not unlike the men about him––Texas boots, a broad sombrero, and a canvas coat to turn the rain,––but his manner was that of another world, a sombre, scholarly repose such as you would look for in the reference room of the Boston Public Library; and he crouched back in his corner like a shy, retiring mouse. For a moment the cowman regarded him intently, as if seeking for some exculpating infirmity; then, leaving the long line of drinkers to chafe at the delay, he paused to pry into the matter.

“Say, partner,” he began, his big mountain voice 14 tamed down to a masterful calm, “won’t you come over and have something with us?”

There was a challenge in the words which did not escape the stranger; he glanced up suddenly from his reading and a startled look came into his eyes as he saw the long line of men watching him. They were large clear eyes, almost piercing in their intentness, yet strangely innocent and childlike. For a moment they rested upon the regal form of the big cowboy, no less a man than Jefferson Creede, foreman of the Dos S, and there was in them something of that silent awe and worship which big men love to see, but when they encountered the black looks of the multitude and the leering smile of Black Tex they lit up suddenly with an answering glint of defiance.

“No, thank you,” he said, nodding amiably to the cowman, “I don’t drink.”

An incredulous murmur passed along the line, mingled with sarcastic mutterings, but the cowman did not stir.

“Well, have a cigar, then,” he suggested patiently; and the barkeeper, eager to have it over, slapped one down on the bar and raised his glass.

“Thank you just as much,” returned the little man politely, “but I don’t smoke, either. I shall have to ask you to excuse me.”

“Have a glass of milk, then,” put in the barkeeper, 15 going off into a guffaw at the familiar jest, but the cowboy shut him up with a look.

“W’y, certainly,” he said, nodding civilly to the stranger. “Come on, fellers!” And with a flourish he raised his glass to his lips as if tossing off the liquor at a gulp. Then with another downward flourish he passed the whiskey into a convenient spittoon and drank his chaser pensively, meanwhile shoving a double eagle across the bar. As Black Tex rang it up and counted out the change Creede stuffed it into his pocket, staring absently out the window at the downpour. Then with a muttered word about his horse he strode out into the storm.

Deprived of their best spender, the crowd drifted back to the tables; friendly games of coon-can sprang up; stud poker was resumed; and a crew of railroad men, off duty, looked out at the sluicing waters and idly wondered whether the track would go out––the usual thing in Arizona. After the first delirium of joy at seeing it rain at all there is an aftermath of misgiving, natural enough in a land where the whole surface of the earth, mountain and desert, has been chopped into ditches by the trailing feet of cattle and sheep, and most of the grass pulled up by the roots. In such a country every gulch becomes a watercourse almost before the dust is laid, the arroyos turn to rivers and the rivers to broad floods, drifting with trees 16 and wreckage. But the cattlemen and sheepmen who happened to be in Bender, either to take on hands for the spring round-up or to ship supplies to their shearing camps out on the desert, were not worrying about the railroad. Whether the bridges went out or held, the grass and browse would shoot up like beanstalks in to-morrow’s magic sunshine; and even if the Rio Salagua blocked their passage, or the shearers’ tents were beaten into the mud, there would still be feed, and feed was everything.

But while the rain was worth a thousand dollars a minute to the country at large, trade languished in the Hotel Bender. In a land where a gentleman cannot take a drink without urging every one within the sound of his voice to join in, the saloon business, while running on an assured basis, is sure to have its dull and idle moments. Having rung up the two dollars and a half which Jefferson Creede paid for his last drink––the same being equivalent to one day’s wages as foreman of the Dos S outfit––Black Tex, as Mr. Brady of the Bender bar preferred to be called, doused the glasses into a tub, turned them over to his roustabout, and polished the cherrywood moodily. Then he drew his eyebrows down and scowled at the little man in the corner.

In his professional career he had encountered a great many men who did not drink, but most of them 17 smoked, and the others would at least take a cigar home to their friends. But here was a man who refused to come in on a treat at all, and a poor, miserable excuse for a man he was, too, without a word for any one. Mr. Brady’s reflections on the perversity of tenderfeet were cut short by a cold blast of air. The door swung open, letting in a smell of wet greasewood, and an old man, his hat dripping, stumbled in and stood swaying against the bar. His aged sombrero, blacksmithed along the ridge with copper rivets, was set far back on a head of long gray hair which hung in heavy strings down his back, like an Indian’s; his beard, equally long and tangled, spread out like a chest protector across his greasy shirt, and his fiery eyes roved furtively about the room as he motioned for a drink. Black Tex set out the bottle negligently and stood waiting.

“Is that all?” he inquired pointedly, as the old man slopped out a drink.

“Well, have one yourself,” returned the old-timer grudgingly. Then, realizing his breach of etiquette, he suddenly straightened up and included the entire barroom in a comprehensive sweep of the hand.

“Come up hyar, all of yoush,” he said drunkenly. “Hev a drink––everybody––no, everybody––come up hyar, I say!” And the graceless saloon bums dropped their cards and came trooping up together. 18 A few of the more self-respecting men slipped quietly out into the card rooms; but the studious stranger, disdaining such puny subterfuges, remained in his place, as impassive and detached as ever.

“Hey, young man,” exclaimed the old-timer jauntily, “step up hyar and nominate yer pizen!”

He closed his invitation with an imperative gesture, but the young man did not obey.

“No, thank you, Uncle,” he replied soberly, “I don’t drink.”

“Well, hev a cigar, then,” returned the old man, finishing out the formula of Western hospitality, and once more Black Tex glowered down upon this guest who was always “knocking a shingle off his sign.”

“Aw, cut it out, Bill,” he sneered, “that young feller don’t drink ner smoke, neither one––and he wouldn’t have no truck with you, nohow!”

They drank, and the stranger dropped back into his reading unperturbed. Once more Black Tex scrubbed the bar and scowled at him; then, tapping peremptorily on the board with a whiskey glass, he gave way to his just resentment.

“Hey, young feller,” he said, jerking his hand arbitrarily, “come over here. Come over here, I said––I want to talk with you!”

For a moment the man in the corner looked up in 19 well-bred surprise; then without attempting to argue the point he arose and made his way to the bar.

“What’s the matter with you, anyway?” demanded Brady roughly. “Are you too good to drink with the likes of us?”

The stranger lowered his eyes before the domineering gaze of his inquisitor and shifted his feet uneasily.

“I don’t drink with anybody,” he said at last. “And if you had any other waiting-room in your hotel,” he added, “I’d keep away from your barroom altogether. As it is, maybe you wouldn’t mind leaving me alone.”

At this retort, reflecting as it did upon the management, Black Tex began to breathe heavily and sway upon his feet.

“I asked you,” he roared, thumping his fist upon the bar and opening up his eyes, “whether you are too good to drink with the likes of us––me, f’r instance––and I want to git an answer!”

He leaned far out over the bar as if listening for the first word before he hit him, but the stranger did not reply immediately. Instead, with simple-minded directness he seemed to be studying on the matter. The broad grin of the card players fell to a wondering stare and every man leaned forward when, raising his sombre eyes from the floor, the little man spoke.

“Why, yes,” he said quietly, “I think I am.”

“Yes, what?” yelled the barkeeper, astounded. “You think you’re what?”

“Now, say,” protested the younger man. Then, apparently recognizing the uselessness of any further evasion, he met the issue squarely.

“Well, since you crowd me to it,” he cried, flaring up, “I am too good! I’m too good a man to drink when I don’t want to drink––I’m too good to accept treats when I don’t stand treat! And more than that,” he added slowly and impressively, “I’m too good to help blow that old man, or any other man, for his money!”

He rose to his utmost height as he spoke, turning to meet the glance of every man in the room, and as he faced them, panting, his deep eyes glowed with a passion of conviction.

“If that is too good for this town,” he said, “I’ll get out of it, but I won’t drink on treats to please anybody.”

The gaze of the entire assembly followed him curiously as he went back to his corner, and Black Tex was so taken aback by this unexpected effrontery on the part of his guest that he made no reply whatever. Then, perceiving that his business methods had been questioned, he drew himself up and frowned darkly.

“Hoity-toity!” he sniffed with exaggerated concern. “Who th’ hell is this, now? One of them little white-ribbon boys, fresh from the East, I bet ye, travellin’ for the W. P. S. Q. T. H’m-m––tech me not––oh deah!” He hiked up his shoulders, twisted his head to a pose, and shrilled his final sarcasms in the tones of a finicky old lady; but the stranger stuck resolutely to his reading, whereupon the black barkeeper went sullen and took a drink by himself.

Like many a good mixer, Mr. Brady of the Hotel Bender was often too good a patron of his own bar, and at such times he developed a mean streak, with symptoms of homicidal mania, which so far had kept the town marshal guessing. Under these circumstances, and with the rumor of a killing at Fort Worth to his credit, Black Tex was accustomed to being humored in his moods, and it went hard with him to be called down in the middle of a spectacular play, and by a rank stranger, at that. The chair-warmers of the Hotel Bender bar therefore discreetly ignored the unexpected rebuke of their chief and proceeded noisily with their games, but the old man who had paid for the drinks was no such time-server. After tucking what was left of his money back into his overalls he balanced against the bar railing for a while and then steered straight for the dark corner.

“Young feller,” he said, leaning heavily upon the 22 table where the stranger was reading, “I’m old Bill Johnson, of Hell’s Hip Pocket, and I wan’er shake hands with you!”

The young man looked up quickly and the card players stopped as suddenly in their play, for Old Man Johnson was a fighter in his cups. But at last the stranger showed signs of friendliness. As the old man finished speaking he rose with the decorum of the drawing-room and extended his white hand cordially.

“I’m very glad to meet you, Mr. Johnson,” he said. “Won’t you sit down?”

“No,” protested the old man, “I do’ wanner sit down––I wanner ask you a question.” He reeled, and balanced himself against a chair. “I wanner ask you,” he continued, with drunken gravity, “on the squar’, now, did you ever drink?”

“Why, yes, Uncle,” replied the younger man, smiling at the question, “I used to take a friendly glass, once in a while––but I don’t drink now.” He added the last with a finality not to be mistaken, but Mr. Johnson of Hell’s Hip Pocket was not there to urge him on.

“No, no,” he protested. “You’re mistaken, Mister––er––Mister––”

“Hardy,” put in the little man.

“Ah yes––Hardy, eh? And a dam’ good name, 23 too. I served under a captain by that name at old Fort Grant, thirty years ago. Waal, Hardy, I like y’r face––you look honest––but I wanner ask you ’nuther question––why don’t you drink now, then?”

Hardy laughed indulgently, and his eyes lighted up with good humor, as if entertaining drunken men was his ordinary diversion.

“Well, I’ll tell you, Mr. Johnson,” he said. “If I should drink whiskey the way you folks down here do, I’d get drunk.”

“W’y sure,” admitted Old Man Johnson, sinking shamelessly into a chair. “I’m drunk now. But what’s the difference?”

Noting the black glances of the barkeeper, Hardy sat down beside him and pitched the conversation in a lower key.

“It may be all right for you, Mr. Johnson,” he continued confidentially, “and of course that’s none of my business; but if I should get drunk in this town, I’d either get into a fight and get licked, or I’d wake up the next morning broke, and nothing to show for it but a sore head.”

“That’s me!” exclaimed Old Man Johnson, slamming his battered hat on the table, “that’s me, Boy, down to the ground! I came down hyar to buy grub f’r my ranch up in Hell’s Hip Pocket, but look at 24 me now, drunk as a sheep-herder, and only six dollars to my name.” He shook his shaggy head and fell to muttering gloomily, while Hardy reverted peacefully to his magazine.

After a long pause the old man raised his face from his arms and regarded the young man searchingly.

“Say,” he said, “you never told me why you refused to drink with me a while ago.”

“Well, I’ll tell you,” answered Hardy, honestly, “and I’m sure you’ll understand how it is with me. I never expect to take another drink as long as I live in this country––not unless I get snake-bit. One drink of this Arizona whiskey will make me foolish, and two will make me drunk, I’m that light-headed. Now, if I had taken a drink with you a minute ago I’d be considered a cheap sport if I didn’t treat back, wouldn’t I? And then I’d be drunk. Yes, that’s a fact. So I have to cut it out altogether. I like you just as well, you understand, and all these other gentlemen, but I just naturally can’t do it.”

“Oh, hell,” protested the old man, “that’s all right. Don’t apologize, Boy, whatever you do. D’yer know what I came over hyar fer?” he asked suddenly reaching out a crabbed hand. “Well, I’ll tell ye. I’ve be’n lookin’ f’r years f’r a white man that I c’d swear off to. Not one of these pink-gilled preachers but a man that would shake hands with me on the squar’ 25 and hold me to it. Now, Boy, I like you––will you shake hands on that?”

“Sure,” responded the young man soberly. “But I tell you, Uncle,” he added deprecatingly, “I just came into town to-day and I’m likely to go out again to-morrow. Don’t you think you could kind of look after yourself while I’m gone? I’ve seen a lot of this swearing-off business already, and it don’t seem to amount to much anyhow unless the fellow that swears off is willing to do all the hard work himself.”

There was still a suggestion of banter in his words, but the old man was too serious to notice it.

“Never mind, boy,” he said solemnly, “I can do all the work, but I jist had to have an honest man to swear off to.”

He rose heavily to his feet, adjusted his copper-riveted hat laboriously, and drifted slowly out the door. And with another spender gone the Hotel Bender lapsed into a sleepy quietude. The rain hammered fitfully on the roof; the card players droned out their bids and bets; and Black Tex, mechanically polishing his bar, alternated successive jolts of whiskey with ill-favored glances into the retired corner where Mr. Hardy, supposedly of the W. P. S. Q. T., was studiously perusing a straw-colored Eastern magazine. Then, as if to lighten the gloom, the sun flashed out suddenly, and before the shadow of the scudding 26 clouds had dimmed its glory a shrill whistle from down the track announced the belated approach of the west-bound train. Immediately the chairs began to scrape; the stud-poker players cut for the stakes and quit; coon-can was called off, and by the time Number Nine slowed down for the station the entire floating population of Bender was lined up to see her come in.

Rising head and shoulders above the crowd and well in front stood Jefferson Creede, the foreman of the Dos S; and as a portly gentleman in an unseasonable linen duster dropped off the Pullman he advanced, waving his hand largely.

“Hullo, Judge!” he exclaimed, grinning jovially. “I was afraid you’d bogged down into a washout somewhere!”

“Not at all, Jeff, not at all,” responded the old gentleman, shaking hands warmly. “Say, this is great, isn’t it?” He turned his genial smile upon the clouds and the flooded streets for a moment and then hurried over toward the hotel.

“Well, how are things going up on the range?” he inquired, plunging headlong into business and talking without a stop. “Nicely, nicely, I don’t doubt. I tell you, Mr. Creede, that ranch has marvellous possibilities––marvellous! All it needs is a little patience, a little diplomacy, you 27 understand––and holding on, until we can pass this forestry legislation. Yes, sir, while the present situation may seem a little strained––and I don’t doubt you are having a hard time––at the same time, if we can only get along with these sheepmen––appeal to their better nature, you understand––until we get some protection at law, I am convinced that we can succeed yet. I want to have a long talk with you on this subject, Jeff––man to man, you understand, and between friends––but I hope you will reconsider your resolution to resign, because that would just about finish us off. It isn’t a matter of money, is it, Jefferson? For while, of course, we are not making a fortune––”

He paused and glanced up at his foreman’s face, which was growing more sullen every minute with restrained impatience.

“Well, speak out, Jeff,” he said resignedly. “What is it?”

“You know dam’ well what it is,” burst out the tall cowboy petulantly. “It’s them sheepmen. And I want to tell you right now that no money can hire me to run that ranch another year, not if I’ve got to smile and be nice to those sons of––well, you know what kind of sons I mean––that dog-faced Jasper Swope, for instance.”

He spat vehemently at the mention of the name 28 and led the way to a card room in the rear of the barroom.

“Of course I’ll work your cattle for you,” he conceded, as he entered the booth, “but if you want them sheepmen handled diplomatically you’d better send up a diplomat. I’m that wore out I can’t talk to ’em except over the top of a six-shooter.”

The deprecating protestations of the judge were drowned by the scuffle of feet as the hangers-on and guests of the hotel tramped in, and in the round of drinks that followed his presence was half forgotten. Not being a drinking man himself, and therefore not given to the generous practice of treating, the arrival of Judge Ware, lately retired from the bench and now absentee owner of the Dos S Ranch, did not create much of a furore in Bender. All Black Tex and the bunch knew was that he was holding a conference with Jefferson Creede, and that if Jeff was pleased with the outcome of the interview he would treat, but if not he would probably retire to the corral and watch his horse eat hay, openly declaring that Bender was the most God-forsaken hell-hole north of the Mexican line––for Creede was a man of moods.

In the lull which followed the first treat, the ingratiating drummer who had set up the drinks, charging 29 the same to his expense account, leaned against the bar and attempted to engage the barkeeper in conversation, asking leading questions about business in general and Mr. Einstein of the New York Store in particular; but Black Tex, in spite of his position, was uncommunicative. Immediately after the arrival of the train the little man who had called him down had returned to the barroom and immersed himself in those wearisome magazines which a lunger had left about the place, and, far from being impressed with his sinister expression, had ignored his unfriendly glances entirely. More than that, he had deserted his dark corner and seated himself on a bench by the window from which he now looked out upon the storm with a brooding preoccupation as sincere as it was maddening. His large deer eyes were fixed upon the distance, and his manner was that of a man who studies deeply upon some abstruse problem; of a man with a past, perhaps, such as often came to those parts, crossed in love, or hiding out from his folks.

Black Tex dismissed the drummer with an impatient gesture and was pondering solemnly upon his grievances when a big, square-jowled cat rushed out from behind the bar and set up a hoarse, raucous mewing.

“Ah, shet up!” growled Brady, throwing him away 30 with his foot; but as the cat’s demands became more and more insistent the barkeeper was at last constrained to take some notice.

“What’s bitin’ you?” he demanded, peering into the semi-darkness behind the bar; and as the cat, thus encouraged, plunged recklessly in among a lot of empty bottles, he promptly threw him out and fished up a mouse trap, from the cage of which a slender tail was wriggling frantically.

“Aha!” he exclaimed, advancing triumphantly into the middle of the floor. “Look, boys, here’s where we have some fun with Tom!” And as the card players turned down their hands to watch the sport, the old cat, scenting his prey, rose up on his hind legs and clutched at the cage, yelling.

Grabbing him roughly by the scruff of the neck Black Tex suddenly threw him away and opened the trap, but the frightened mouse, unaware of his opportunity, remained huddled up in the corner.

“Come out of that,” grunted the barkeeper, shaking the cage while with his free hand he grappled the cat, and before he could let go his hold the mouse was halfway across the room, heading for the bench where Hardy sat.

“Ketch ’im!” roared Brady, hurling the eager cat after it, and just as the mouse was darting down a hole Tom pinned it to the floor with his claws.

“What’d I tell ye?” cried the barkeeper, swaggering. “That cat will ketch ’em every time. Look at that now, will you?”

With dainty paws arched playfully, the cat pitched the mouse into the air and sprang upon it like lightning as it darted away. Then mumbling it with a nicely calculated bite, he bore it to the middle of the floor and laid it down, uninjured.

“Ain’t he hell, though?” inquired Tex, rolling his eyes upon the spectators. The cat reached out cautiously and stirred it up with his paw; and once more, as his victim dashed for its hole, he caught it in full flight. But now the little mouse, its hair all wet and rumpled, crouched dumbly between the feet of its captor and would not run. Again and again the cat stirred it up, sniffing suspiciously to make sure it was not dead; then in a last effort to tempt it he deliberately lay over on his back and rolled, purring and closing his eyes luxuriously, until, despite its hurts, the mouse once more took to flight. Apparently unheeding, the cat lay inert, following its wobbly course with half-shut eyes––then, lithe as a panther, he leaped up and took after it. There was a rush and a scramble against the wall, but just as he struck out his barbed claw a hand closed over the mouse and the little man on the bench whisked it dexterously away.

Instantly the black cat leaped into the air, clamoring 32 for his prey, and with a roar like a mountain bull Black Tex rushed out to intercede.

“Put down that mouse, you freak!” he bellowed, charging across the room. “Put ’im down, I say, or I’ll break you in two!” He launched his heavy fist as he spoke, but the little man ducked it neatly and, stepping behind a table, stood at bay, still holding the mouse.

“Put ’im down, I tell you!” shouted the barkeeper, panting with vexation. “What––you won’t, eh? Well, I’ll learn you!” And with a wicked oath he drew his revolver and levelled it across the table.

“Put––down––that––mouse!” he said slowly and distinctly, but Hardy only shook his head. Every man in the room held his breath for the report; the poker players behind fell over tables and chairs to get out of range; and still they stood there, the barkeeper purple, the little man very pale, glaring at one another along the top of the barrel. In the hollow of his hand Hardy held the mouse, which tottered drunkenly; while the cat, still clamoring for his prize, raced about under the table, bewildered.

“Hurry up, now,” said the barkeeper warningly, “I’ll give you five. One––come on, now––two––”

At the first count the old defiance leaped back into Hardy’s eyes and he held the mouse to his bosom as a mother might shield her child; at the second he 33 glanced down at it, a poor crushed thing trembling as with an ague from its wounds; then, smoothing it gently with his hand, he pinched its life out suddenly and dropped it on the floor.

Instantly the cat pounced upon it, nosing the body eagerly, and Black Tex burst into a storm of oaths.

“Well, dam’ your heart,” he yelled, raising his pistol in the air as if about to throw the muzzle against his breast and fire. “What––in––hell––do you mean?”

Baffled and evaded in every play the evil-eyed barkeeper suddenly sensed a conspiracy to show him up, and instantly the realization of his humiliation made him dangerous.

“Perhaps you figure on makin’ a monkey out of me!” he suggested, hissing snakelike through his teeth; but Hardy made no answer whatever.

“Well, say something, can’t you?” snapped the badman, his overwrought nerves jangled by the delay. “What d’ye mean by interferin’ with my cat?”

For a minute the stranger regarded him intently, his sad, far-seeing eyes absolutely devoid of evil intent, yet baffling in their inscrutable reserve––then he closed his lips again resolutely, as if denying expression to some secret that lay close to his heart, turning it with undue vehemence to the cause of those who suffer and cannot escape.

“Well, f’r Gawd’s sake,” exclaimed Black Tex at last, lowering his gun in a pet, “don’t I git no satisfaction––what’s your i-dee?”

“There’s too much of this cat-and-mouse business going on,” answered the little man quietly, “and I don’t like it.”

“Oh, you don’t, eh?” echoed the barkeeper sarcastically; “well, excuse me! I didn’t know that.” And with a bow of exaggerated politeness he retired to his place.

“The drinks are on the house,” he announced, jauntily strewing the glasses along the bar. “Won’t drink, eh? All right. But lemme tell you, pardner,” he added, wagging his head impressively, “you’re goin’ to git hurt some day.”

After lashing the desert to a frazzle and finding the leaks in the Hotel Bender, the wind from Papaguería went howling out over the mesa, still big with rain for the Four Peaks country, and the sun came out gloriously from behind the clouds. Already the thirsty sands had sucked up the muddy pools of water, and the board walk which extended the length of the street, connecting saloon with saloon and ending with the New York Store, smoked with the steam of drying. Along the edge of the walk, drying out their boots in the sun, the casual residents of the town––many of them held up there by the storm––sat in pairs and groups, talking or smoking in friendly silence. A little apart from the rest, for such as he are a long time making friends in Arizona, Rufus Hardy sat leaning against a post, gazing gloomily out across the desert. For a quiet, retiring young man, interested in good literature and bearing malice toward no one, his day in the Bender barroom had been eventful out of all proportion to his deserts and wishes, and he was deep in somber meditation 36 when the door opened and Judge Ware stepped out into the sunshine.

In outward appearance the judge looked more like a large fresh-faced boy in glasses than one of San Francisco’s eminent jurists, and the similarity was enhanced by the troubled and deprecating glances with which he regarded his foreman, who towered above him like a mentor. There was a momentary conference between them at the doorway, and then, as Creede stumped away down the board walk, the judge turned and reluctantly approached Hardy.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” he began, as the young man in some confusion rose to meet him, “but I should like a few words with you, on a matter of business. I am Mr. Ware, the owner of the Dos S Ranch––perhaps you may have heard of it––over in the Four Peaks country. Well––I hardly know how to begin––but my foreman, Mr. Creede, was highly impressed with your conduct a short time ago in the––er––affray with the barkeeper. I––er––really know very little as to the rights of the matter, but you showed a high degree of moral courage, I’m sure. Would you mind telling me what your business is in these parts, Mr.––er––”

“Hardy,” supplied the young man quietly, “Rufus Hardy. I am––”

“Er––what?” exclaimed the judge, hastily focussing his glasses. “Hardy––Hardy––where have I heard that name before?”

“I suppose from your daughter, Miss Lucy,” replied the young man, smiling at his confusion. “Unless,” he added hastily, “she has forgotten about me.”

“Why, Rufus Hardy!” exclaimed the judge, reaching out his hand. “Why, bless my heart––to be sure. Why, where have you been for this last year and more? I am sure your father has been quite worried about you.”

“Oh, I hope not,” answered Hardy, shifting his gaze. “I guess he knows I can take care of myself by this time––if I do write poetry,” he added, with a shade of bitterness.

“Well, well,” said the judge, diplomatically changing the subject, “Lucy will be glad to hear of you, at any rate. I believe she––er––wrote you once, some time ago, at your Berkeley address, and the letter was returned as uncalled for.”

He gazed over the rims of his glasses inquiringly, and with a suggestion of asperity, but the young man was unabashed.

“I hope you will tell Miss Lucy,” he said deferentially, “that on account of my unsettled life I have not ordered my mail forwarded for some time.” He 38 paused and for the moment seemed to be considering some further explanation; then his manner changed abruptly.

“I believe you mentioned a matter of business,” he remarked bluffly, and the judge came back to earth with a start. His mind had wandered back a year or more to the mysterious disappearance of this same self-contained young man from his father’s house, not three blocks from his own comfortable home. There had been a servant’s rumor that he had sent back a letter or two postmarked “Bowie, Arizona”––but old Colonel Hardy had said never a word.

“Er––yes,” he assented absently, “but––well, I declare,” he exclaimed helplessly, “I’ve quite forgotten what it was about.”

“Won’t you sit down, then?” suggested Hardy, indicating the edge of the board walk with a courtly sweep of the hand. “This rain will make good feed for you up around the Four Peaks––I believe it was of your ranch there that you wished to speak.”

Judge Ware settled down against a convenient post and caught his breath, meanwhile regarding his companion curiously.

“Yes, that’s it,” he said. “I wanted to talk with you about my ranch, but I swear I’ll have to wait till Creede comes back, now.”

“Very well,” answered Hardy easily; “we can talk 39 about home, then. How is Miss Lucy succeeding with her art––is she still working at the Institute?”

“Yes, indeed!” exclaimed the judge, quite mollified by the inquiry. “Indeed she is, and doing as well as any of them. She had a landscape hung at the last exhibit, that was very highly praised, even by Mathers, and you know how hard he is to please. Tupper Browne won the prize, but I think Lucy’s was twice the picture––kind of soft and sunshiny, you know––it made you think of home, just to look at it.”

“Well, I’m glad to hear that,” said Hardy, looking up the ragged street a little wistfully. “I kind of lose track of things down here, knocking around from place to place.” He seated himself wearily on the edge of the sidewalk and drummed with his sinewy white hands against a boot leg. “But it’s a great life, sure,” he observed, half to himself. “And by the way, Mr. Ware,” he continued, “if it’s all the same to you I wish you wouldn’t say anything to your foreman about my past life. Not that there is anything disgraceful about it, but there isn’t much demand for college graduates in this country, you know, and I might want to strike him for a job.”

Judge Ware nodded, a little distantly; he did not approve of this careless young man in all his moods. For a man of good family he was hardly presentable, for one thing, and he spoke at times like an ordinary 40 working man. So he awaited the lumbering approach of his foreman in sulky silence, resolved to leave the matter entirely in his hands.

Jefferson Creede bore down upon them slowly, sizing up the situation as he came, or trying to, for everything seemed to be at a standstill.

“Well?” he remarked, looking inquiringly from the judge to Hardy. “How about it?”

There was something big and dominating about him as he loomed above them, and the judge’s schoolboy state of mind instantly returned.

“I––I really haven’t done anything about the matter, Jefferson,” he stammered apologetically. “Perhaps you will explain our circumstances to Mr. Hardy here, so that we can discuss the matter intelligently.” He looked away as he spoke, and the tall foreman grunted audibly.

“Well,” he drawled, “they ain’t much to explain. The sheepmen have been gittin’ so free up on our range that I’ve had a little trouble with ’em––and if I was the boss they’d be more trouble, you can bet your life on that. But the judge here seems to think we can kinder suck the hind teat and baby things along until they git that Forest Reserve act through, and make our winnin’ later. He wants to make friends with these sheepmen and git ’em to kinder go around a little and give us half a chanst. Well, 41 maybe it can be done––but not by me. So I told him either to get a superintendent to handle the sheep end of it or rustle up a new foreman, because I see red every time I hear a sheep-blat.

“Then come the question,” continued the cowman, throwing out his broad hand as if indicating the kernel of the matter, “of gittin’ such a man, and while we was talkin’ it over you called old Tex down so good and proper that there wasn’t any doubt in my mind––providin’ you want the job, of course.”

He paused and fixed his compelling eyes upon Hardy with such a mixture of admiration and good humor that the young man was won over at once, although he made no outward sign. It was Judge Ware who was to pass upon the matter finally, and he waited deferentially for him to speak.

“Well––er––Jefferson,” began the judge a little weakly, “do you think that Mr. Hardy possesses the other qualities which would be called for in such a man?”

“W’y, sure,” responded Creede, waving the matter aside impatiently. “Go ahead and hire him before he changes his mind.”

“Very well then, Mr. Hardy,” said the judge resignedly, “the first requisite in such a man is that he shall please Mr. Creede. And since he commends you so warmly I hope that you will accept the position. 42 Let me see––um––would seventy-five dollars a month seem a reasonable figure? Well, call it seventy-five, then––that’s what I pay Mr. Creede, and I want you to be upon an equality in such matters.

“Now as to your duties. Jefferson will have charge of the cattle, as usual; and I want you, Mr. Hardy, to devote your time and attention to this matter of the sheep. Our ranch house at Hidden Water lies almost directly across the river from one of the principal sheep crossings, and a little hospitality shown to the shepherds in passing might be like bread cast upon the waters which comes back an hundred fold after many days. We cannot hope to get rid of them entirely, but if the sheep owners would kindly respect our rights to the upper range, which Mr. Creede will point out to you, I am sure we should take it very kindly. Now that is your whole problem, Rufus, and I leave the details entirely in your hands. But whatever you do, be friendly and see if you can’t appeal to their better nature.”

He delivered these last instructions seriously and they were so taken by Hardy, but Creede laughed silently, showing all his white teeth, yet without attracting the unfavorable attention of the judge, who was a little purblind. Then there was a brief discussion of details, an introduction to Mr. Einstein of the New York Store, where Hardy was given 43 carte blanche for supplies, and Judge Ware swung up on the west-bound limited and went flying away toward home, leaving his neighbor’s son––now his own superintendent and sheep expert––standing composedly upon the platform.

“Well,” remarked Creede, smiling genially as he turned back to the hotel, “the Old Man’s all right, eh, if he does have fits! He’s good-hearted––and that goes a long ways in this country––but actually, I believe he knows less about the cattle business than any man in Arizona. He can’t tell a steer from a stag––honest! And I can lose him a half-mile from camp any day.”

The tall cattleman clumped along in silence for a while, smiling over some untold weakness of his boss––then he looked down upon Hardy and chuckled to himself.

“I’m glad you’re going to be along this trip,” he said confidentially. “Of course I’m lonely as a lost dog out there, but that ain’t it; the fact is, I need somebody to watch me. W’y, boy, I could beat the old judge out of a thousand dollars’ worth of cattle and he’d never know it in a lifetime. Did ye ever live all alone out on a ranch for a month or so? Well, you know how lawless and pisen-mean a man can git, then, associatin’ with himself. I’d’ve had the old man robbed forty times over if he wasn’t such a good-hearted 44 old boy, but between fightin’ sheepmen and keepin’ tab on a passel of brand experts up on the Tonto I’m gittin’ so ornery I don’t dare trust myself. Have a smoke? Oh, I forgot––”

He laughed awkwardly and rolled a cigarette.

“Got a match?” he demanded austerely. “Um, much obliged––be kinder handy to have you along now.” He knit his brows fiercely as he fired up, regarding Hardy with a furtive grin.

“Say,” he said abruptly, “I’ve got to make friends with you some way. You eat, don’t you? All right then, you come along with me over to the Chink’s. I’m going to treat you to somethin’, if it’s only ham ’n’ eggs.”

They dined largely at Charley’s and then drifted out to the feed corral. Creede threw down some hay to a ponderous iron-scarred roan, more like a war horse than a cow pony, and when he came back he found Hardy doing as much for a clean-limbed sorrel, over by the gate.

“Yourn?” he inquired, surveying it with the keen concentrated gaze which stamps every point on a cowboy’s memory for life.

“Sure,” returned Hardy, patting his pony carefully upon the shoulder.

“Kinder high-headed, ain’t he?” ventured Creede, as the sorrel rolled his eyes and snorted.

“That’s right,” assented Hardy, “he’s only been broke about a month. I got him over in the Sulphur Springs Valley.”

“I knowed it,” said the cowboy sagely, “one of them wire-grass horses––an’ I bet he can travel, too. Did you ride him all the way here?”

“Clean from the Chiricahuas,” replied the young man, and Jefferson Creede looked up, startled.

“What did you say you was doin’ over there?” he inquired slowly, and Hardy smiled quietly as he answered:

“Riding for the Cherrycow outfit.”

“The hell you say!” exclaimed Creede explosively, and for a long time he stood silent, smoking as if in deep meditation.

“Well,” he said at last, “I might as well say it––I took you for a tenderfoot.”

The morning dawned as clear on Bender as if there had never been storm nor clouds, and the waxy green heads of the greasewood, dotting the level plain with the regularity of a vineyard, sparkled with a thousand dewdrops. Ecstatic meadow larks, undismayed by the utter lack of meadows, sang love songs from the tops of the telegraph poles; and the little Mexican ground doves that always go in pairs tracked amiably about together in the wet litter of the corral, picking up the grain which the storm had laid bare. Before the early sun had cleared the top of the eastern mountains Jefferson Creede and Hardy had risen and fed their horses well, and while the air was yet chill they loaded their blankets and supplies upon the ranch wagon, driven by a shivering Mexican, and went out to saddle up.

Since his confession of the evening before Creede had put aside his air of friendly patronage and, lacking another pose, had taken to smoking in silence; for there is many a boastful cowboy in Arizona who has done his riding for the Cherrycow outfit on the 47 chuck wagon, swamping for the cook. At breakfast he jollied the Chinaman into giving him two orders of everything, from coffee to hot cakes, paid for the same at the end, and rose up like a giant refreshed––but beneath this jovial exterior he masked a divided mind. Although he had come down handsomely, he still had his reservations about the white-handed little man from Cherrycow, and when they entered the corral he saddled his iron-scarred charger by feeling, gazing craftily over his back to see how Hardy would show up in action.

Now, first the little man took a rope, and shaking out the loop dropped it carelessly against his horse’s fore-feet––and that looked well, for the sorrel stood stiffly in his tracks, as if he had been anchored. Then the man from Cherrycow picked up his bridle, rubbed something on the bit, and offered it to the horse, who graciously bowed his head to receive it. This was a new one on Creede and in the excitement of the moment he inadvertently cinched his roan up two holes too tight and got nipped for it, for old Bat Wings had a mind of his own in such matters, and the cold air made him ugly.

“Here, quit that,” muttered the cowboy, striking back at him; but when he looked up, the sorrel had already taken his bit, and while he was champing on it Hardy had slipped the headstall over his ears. 48 There was a broad leather blind on the hacamore, which was of the best plaited rawhide with a horsehair tie rope, but the little man did not take advantage of it to subdue his mount. Instead he reached down for his gaudy Navajo saddle blanket, offered it to the sorrel to smell, and then slid it gently upon his back. But when he stooped for his saddle the high-headed horse rebelled. With ears pricked suspiciously forward and eyes protruding he glared at the clattering thing in horror, snorting deep at every breath. But, though he was free-footed, by some obsession of the mind, cunningly inculcated in his breaking, the sorrel pony was afraid to move.

As the saddle was drawn toward him and he saw that he could not escape its hateful embrace he leaned slowly back upon his haunches, grunting as if his fore-feet, wreathed in the loose rope, were stuck in some terrible quicksands from which he tried in vain to extricate them; but with a low murmur of indifferent words his master moved the saddle resolutely toward him, the stirrups carefully snapped up over the horn, and ignoring his loud snorts and frenzied shakings of the head laid it surely down upon his back. This done, he suddenly spoke sharply to him, and with a final groan the beautiful creature rose up and consented to his fate.

Hardy worked quickly now, tightening the cinch, 49 lowering the stirrups, and gathering up the reins. He picked up the rope, coiled it deftly and tied it to the saddle––and now, relieved of the idea that he was noosed, the pony began to lift his feet and prance, softly, like a swift runner on the mark. At these signs of an early break Creede mounted hurriedly and edged in, to be ready in case the sorrel, like most half-broken broncos, tried to scrape his rider off against the fence; but Hardy needed no wrangler to shunt him out the gate. Standing by his shoulder and facing the rear he patted the sorrel’s neck with the hand that held the reins, while with his right hand he twisted the heavy stirrup toward him stealthily, raising his boot to meet it. Then like a flash he clapped in his foot and, catching the horn as his fiery pony shot forward, he snapped up into the saddle like a jumping jack and went flying out the gate.

“Well, the son of a gun!” muttered Creede, as he thundered down the trail after him. “Durned if he can’t ride!”

There are men in every cow camp who can rope and shoot, but the man who can ride a wild horse can hold up his head with the best of them. No matter what his race or station if he will crawl a “snake” and stay with him there is always room on the wagon for his blankets; his fame will spread quickly from camp to camp, and the boss will offer to raise him when he 50 shows up for his time. Jefferson Creede’s face was all aglow when he finally rode up beside Hardy; he grinned triumphantly upon horse and man as if they had won money for him in a race; and Hardy, roused at last from his reserve, laughed back out of pure joy in his possessions.

“How’s that for a horse?” he cried, raising his voice above the thud of hoofs. “I have to turn him loose at first––’fraid he’ll learn to pitch if I hold him in––he’s never bucked with me yet!”

“You bet––he’s a snake!” yelled Creede, hammering along on his broad-chested roan. “Where’d you git ’im?”

“Tom Fulton’s ranch,” responded Hardy, reining his horse in and patting him on the neck. “Turned in three months’ pay and broke him myself, to boot. I’ll let you try him some day, when he’s gentled.”

“Well, if I wasn’t so big ’n’ heavy I’d take you up on that,” said Creede, “but I’m just as much obliged, all the same. I don’t claim to be no bronco-buster now, but I used to ride some myself when I was a kid. But say, the old judge has got some good horses runnin’ on the upper range,––if you want to keep your hand in,––thirty or forty head of ’em, and wild as hawks. There’s some sure-enough wild horses too, over on the Peaks, that belong to any man that can git his rope onto ’em––how would that strike you? 51 We’ve been tryin’ for years to catch the black stallion that leads ’em.”

Try as he would to minimize this exaggerated estimate of his prowess as a horse-tamer Hardy was unable to make his partner admit that he was anything short of a real “buster,” and before they had been on the trail an hour Creede had made all the plans for a big gather of wild horses after the round-up.

“I had you spotted for a sport from the start,” he said, puffing out his chest at the memory of his acumen, “but, by jingo, I never thought I was drawin’ a bronco-twister. Well, now, I saw you crawl that horse this mornin’, and I guess I know the real thing by this time. Say,” he said, turning confidentially in his saddle, “if it’s none of my business you can say so, but what did you do to that bit?”

Hardy smiled, like a juggler detected in his trick. “You must have been watching me,” he said, “but I don’t mind telling you––it’s simply passing a good thing along. I learned it off of a Yaqui Mayo Indian that had been riding for Bill Greene on the Turkey-track––I rubbed it with a little salt.”

“Well, I’m a son of a gun!” exclaimed Creede incredulously. “Here we’ve been gittin’ our fingers bit off for forty years and never thought of a little thing like that. Got any more tricks?”

“Nope,” said Hardy, “I’ve only been in the Territory 52 a little over a year, this trip, and I’m learning, myself. Funny how much you can pick up from some of these Indians and Mexicans that can’t write their own names, isn’t it?”

“Umm, may be so,” assented Creede doubtfully, “but I’d rather go to a white man myself. Say,” he exclaimed, changing the subject abruptly, “what was that name the old man called you by when he was makin’ that talk about sheep––Roofer, or Rough House––or something like that?”

“Oh, that’s my front name––Rufus. Why? What’s the matter with it?”

“Nothin’, I reckon,” replied Creede absently, “never happened to hear it before, ’s all. I was wonderin’ how he knowed it,” he added, glancing shrewdly sideways. “Thought maybe you might have met him up in California, or somewheres.”

“Oh, that’s easy,” responded Hardy unblinkingly. “The first thing he did was to ask me my full name. I notice he calls you Jefferson,” he added, shiftily changing the subject.

“Sure thing,” agreed Creede, now quite satisfied, “he calls everybody that way. If your name is Jim you’re James, John you’re Jonathan, Jeff you’re Jefferson Davis––but say, ain’t they any f’r short to your name? We’re gittin’ too far out of town for 53 this Mister business. My name’s Jeff, you know,” he suggested.

“Why, sure,” exclaimed Hardy, brushing aside any college-bred scruples, “only don’t call me Rough House––they might get the idea that I was on the fight. But you don’t need to get scared of Rufus––it’s just another way of saying Red. I had a red-headed ancestor away back there somewhere and they called him Rufus, and then they passed the name down in the family until it got to me, and I’m no more red-headed than you are.”

“No––is that straight?” ejaculated the cowboy, with enthusiasm, “same as we call ’em Reddy now, eh? But say, I’d choke if I tried to call you Rufus. Will you stand for Reddy? Aw, that’s no good––what’s the matter with Rufe? Well, shake then, pardner, I’m dam’ glad I met up with you.”

They pulled their horses down to a Spanish trot––that easy, limping shuffle that eats up its forty miles a day––and rode on together like brothers, heading for a distant pass in the mountains where the painted cliffs of the Bulldog break away and leave a gap down to the river. To the east rose Superstition Mountain, that huge buttress upon which, since the day that a war party of Pimas disappeared within the shadow of its pinnacles, hot upon the trail of the Apaches, and never 54 returned again, the Indians of the valley have always looked with superstitious dread.

Creede told the story carelessly, smiling at the pride of the Pimas who refused to admit that the Apaches alone, devils and bad medicine barred, could have conquered so many of their warriors. To the west in a long fringe of green loomed the cottonwoods of Moroni, where the hard-working Mormons had turned the Salagua from its course and irrigated the fertile plain, and there on their barren reservation dwelt the remnant of those warlike Pimas, the unrequited friends of the white men, now held by them as of no account.

As he heard the history of its people––how the Apaches had wiped out the Toltecs, and the white men had killed off the Apaches, and then, after pushing aside the Pimas and the Mexicans, closed in a death struggle for the mastery of the range––Hardy began to perceive the grim humor of the land. He glanced across at his companion, tall, stalwart, with mighty arms and legs and features rugged as a mountain crag, and his heart leaped up within him at the thought of the battles to come, battles in which sheepmen and cattlemen, defiant of the law, would match their strength and cunning in a fight for the open range.

As they rode along mile after mile toward the north 55 the road mounted gently; hills rose up one by one out of the desert floor, crowned with towering sahuaros, and in the dip of the pass ahead a mighty forest of their misshapen stalks was thrust up like giant fingers against the horizon. The trail wound in among them, where they rose like fluted columns above the lesser cactus––great skin-covered tanks, gorged fat with water too bitter to quench the fieriest thirst, yet guarded jealously by poison-barbed spines. Gilded woodpeckers, with hearts red as blood painted upon their breasts, dipped in uneven flight from sahuaro to sahuaro, dodged into holes of their own making, dug deep into the solid flesh; sparrow hawks sailed forth from their summits, with quick eyes turned to the earth for lizards; and the brown mocking bird, leaping for joy from the ironwood tree where his mate was nesting, whistled the praise of the desert in the ecstatic notes of love. In all that land which some say God forgot, there was naught but life and happiness, for God had sent the rain.

The sun was high in the heavens when, as they neared the summit of the broad pass, a sudden taint came down the wind, whose only burden had been the fragrance of resinous plants, of wetted earth, and of green things growing. A distant clamor, like the babble of many voices or the surf-beats of a mighty sea, echoed dimly between the chuck-a-chuck of their 56 horses’ feet, and as Hardy glanced up inquiringly his companion’s lip curled and he muttered:

“Sheep!”

They rode on in silence. The ground, which before had been furred with Indian wheat and sprouting six weeks’ grass, now showed the imprints of many tiny feet glozed over by the rain, and Hardy noticed vaguely that something was missing––the grass was gone. Even where a minute before it had covered the level flats in a promise of maturity, rising up in ranker growth beneath the thorny trees and cactus, its place was now swept bare and all the earth trampled into narrow, hard-tamped trail. Then as a brush shed and corrals, with a cook tent and a couple of water wagons in the rear, came into view, the ground went suddenly stone bare, stripped naked and trampled smooth as a floor. Never before had Hardy seen the earth so laid waste and desolate, the very cactus trimmed down to its woody stump and every spear of root grass searched out from the shelter of the spiny chollas. He glanced once more at his companion, whose face was sullen and unresponsive; there was a well-defined bristle to his short mustache and he rowelled his horse cruelly when he shied at the blatting horde.

The shearing was in full blast, every man working with such feverish industry that not one of them 57 stopped to look up. From the receiving corral three Mexicans in slouched hats and jumpers drove the sheep into a broad chute, yelling and hurling battered oil cans at the hindmost; by the chute an American punched them vigorously forward with a prod, and yet another thrust them into the pens behind the shearers, who bent to their work with a sullen, back-breaking stoop. Each man held between his knees a sheep, gripped relentlessly, that flinched and kicked at times when the shears clipped off patches of flesh; and there in the clamor of a thousand voices they shuttled their keen blades unceasingly, stripping off a fleece, throwing it aside, and seizing a fresh victim by the foot, toiling and sweating grimly. By another chute a man stood with a paint pot, stamping a fresh brand upon every new-shorn sheep, and in a last corral the naked ones, their white hides spotted with blood from their cuts, blatted frantically for their lambs. These were herded in a small inclosure, some large and browned with the grime of the flock, others white and wobbly, newborn from mothers frightened in the shearing; and always that tremendous wailing chorus––Ba-a-a, ba-a-a, ba-a-a––and men in greasy clothes wrestling with the wool.

To a man used to the noise and turmoil of the round-up and branding pen and accustomed to the 58 necessary cruelties of stock raising there was nothing in the scene to attract attention. But Hardy was of gentler blood, inured to the hardships of frontier life but not to its unthinking brutality, and as he beheld for the first time the waste, the hurry, the greed of it all, his heart turned sick and his eyes glowed with pity, like a woman’s. By his side the sunburned swarthy giant who had taken him willy-nilly for a friend sat unmoved, his lip curled, not at the pity of it, but because they were sheep; and because, among the men who rushed about driving them with clubs and sacks, he saw more than one who had eaten at his table and then sheeped out his upper range. His saturnine mood grew upon him as he waited and, turning to Hardy, he shouted harshly:

“There’s some of your friends over yonder,” he said, jerking his thumb toward a group of men who were weighing the long sacks of wool. “Want to go over and get acquainted?”

Hardy woke from his dream abruptly and shook his head.

“No, let’s not stop,” he said, and Creede laughed silently as he reined Bat Wings into the trail. But just as they started to go one of the men by the scales hailed them, motioning with his hand and, still laughing cynically, the foreman of the Dos S turned back again.

“That’s Jim Swope,” he said, “one of our big sheep men––nice feller––you’ll like him.”

He led the way to the weighing scales, where two sweating Mexicans tumbled the eight-foot bags upon the platform, and a burly man with a Scotch turn to his tongue called off the weights defiantly. At his elbow stood two men, the man who had called them and a wool buyer,––each keeping tally of the count.

Jim Swope glanced quickly up from his work. He was a man not over forty but bent and haggard, with a face wrinkled deep with hard lines, yet lighted by blue eyes that still held a twinkle of grim humor.

“Hello, Jeff,” he said, jotting down a number in his tally book, “goin’ by without stoppin’, was ye? Better ask the cook for somethin’ to eat. Say, you’re goin’ up the river, ain’t ye? Well, tell Pablo Moreno and them Mexicans I lost a cut of two hundred sheep up there somewhere. That son of a––of a herder of mine was too lazy to make a corral and count ’em, so I don’t know where they are lost, but I’ll give two bits a head for ’em, delivered here. Tell the old man that, will you?”

He paused to enter another weight in his book, then stepped away from the scales and came out to meet them.

“How’s the feed up your way?” he inquired, smiling grimly.

“Dam’ pore,” replied Creede, carrying on the jest, “and it’ll be poorer still if you come in on me, so keep away. Mr. Swope, I’ll make you acquainted with Mr. Hardy––my new boss. Judge Ware has sent him out to be superintendent for the Dos S.”

“Glad to meet you, sir,” said Swope, offering a greasy hand that smelled of sheep dip. “Nice man, the old judge––here, umbre, put that bag on straight! Three hundred and fifteen? Well I know a dam’ sight better––excuse me, boys––here, put that bag on again, and weigh it right!”

“Well,” observed Creede, glancing at his friend as the combat raged unremittingly, “I guess we might as well pull. His busy day, you understand. Nice feller, though––you’ll like ’im.” Once more the glint of quiet deviltry came into his eyes, but he finished out the jest soberly. “Comes from a nice Mormon family down in Moroni––six brothers––all sheepmen. You’ll see the rest of the boys when they come through next month––but Jim’s the best.”

There was something in the sardonic smile that accompanied this encomium which set Hardy thinking. Creede must have been thinking too, for he rode past the kitchen without stopping, cocking his head up at the sun as if estimating the length of their journey.

“Oh, did you want to git somethin’ to eat?” he 61 inquired innocently. “No? That’s good. That sheep smell kinder turns my stomach.” And throwing the spurs into Bat Wings he loped rapidly toward the summit, scowling forbiddingly in passing at a small boy who was shepherding the stray herd. For a mile or two he said nothing, swinging his head to scan the sides of the mountains with eyes as keen as an eagle’s; then, on the top of the last roll, he halted and threw his hand out grandly at the panorama which lay before them.

“There she lays,” he said, as if delivering a funeral oration, “as good a cow country as God ever made––and now even the jack rabbits have left it. D’ye see that big mesa down there?” he continued, pointing to a broad stretch of level land, dotted here and there with giant cactus, which extended along the river. “I’ve seen a thousand head of cattle, fat as butter, feedin’ where you see them sahuaros, and now look at it!”

He threw out his hand again in passionate appeal, and Hardy saw that the mesa was empty.

“There was grass a foot high,” cried Creede in a hushed, sustained voice, as if he saw it again, “and flowers. Me and my brothers and sisters used to run out there about now and pick all kinds, big yaller poppies and daisies, and these here little pansies––and ferget-me-nots. God! I wish I could ferget ’em––but 62 I’ve been fightin’ these sheep so long and gittin’ so mean and ugly them flowers wouldn’t mean no more to me now than a bunch of jimson weeds and stink squashes. But hell, what’s the use?” He threw out his hands once more, palms up, and dropped them limply.

“That’s old Pablo Moreno’s place down there,” he said, falling back abruptly into his old way. “We’ll stop there overnight––I want to help git that wagon across the river when Rafael comes in bymeby, and we’ll go up by trail in the mornin’.”

Once more he fell into his brooding silence, looking up at the naked hills from habit, for there were no cattle there. And Rufus Hardy, quick to understand, gazed also at the arid slopes, where once the grama had waved like tawny hair in the soft winds and the cattle of Jeff Creede’s father had stood knee-high in flowers.

Now at last the secret of Arizona-the-Lawless and Arizona-the-Desert lay before him: the feed was there for those who could take it, and the sheep were taking it all. It was government land, only there was no government; anybody’s land, to strip, to lay waste, to desolate, to hog for and fight over forever––and no law of right; only this, that the best fighter won. Thoughts came up into his mind, as thoughts will in the silence of the desert; memories of other 63 times and places, a word here, a scene there, having no relation to the matter in hand; and then one flashed up like the premonitions of the superstitious––a verse from the Bible that he had learned at his mother’s knee many years before:

“Crying, Peace, Peace, when there is no peace.”

But he put it aside lightly, as a man should, for if one followed every vagrant fancy and intuition, taking account of signs and omens, he would slue and waver in his course like a toy boat in a mill pond, which after great labor and adventure comes, in the end, to nothing.

On the edge of the barren mesa and looking out over the sandy flats where the Salagua writhed about uneasily in its bed, the casa of Don Pablo Moreno stood like a mud fort, barricaded by a palisade of the thorny cactus which the Mexicans call ocotilla. Within this fence, which inclosed several acres of standing grain and the miniature of a garden, there were all the signs of prosperity––a new wagon under its proper shade, a storehouse strongly built where chickens lingered about for grain, a clean-swept ramada casting a deep shadow across the open doorway; but outside the inclosure the ground was stamped as level as a threshing floor. As Creede and Hardy drew near, an old man, grave and dignified, came out from the shady veranda and opened the gate, bowing with the most courtly hospitality.

“Buenos tardes, señores,” he pronounced, touching his hat in a military salute. “Pasa! Welcome to my poor house.”

In response to these salutations Creede made the 65 conventional replies, and then as the old man stood expectant he said in a hurried aside to Hardy:

“D’ye talk Spanish? He don’t understand a word of English.”

“Sure,” returned Hardy. “I was brought up on it!”

“No!” exclaimed Creede incredulously, and then, addressing the Señor Moreno in his native tongue, he said: “Don Pablo, this is my friend Señor Hardy, who will live with me at Agua Escondida!”

“With great pleasure, señor,” said the old gentleman, removing his hat, “I make your acquaintance!”

“The pleasure is mine,” replied Hardy, returning the salutation, and at the sound of his own language Don Pablo burst into renewed protestations of delight. Within the cool shadow of his ramada he offered his own chair and seated himself in another, neatly fashioned of mesquite wood and strung with thongs of rawhide. Then, turning his venerable head to the doorway which led to the inner court, he shouted in a terrible voice:

“Muchacho!”

Instantly from behind the adobe wall, around the corner of which he had been slyly peeping, a black-eyed boy appeared and stood before him, his ragged straw hat held respectfully against his breast.

“Sus manos!” roared the old man; and dropping 66 his hat the muchacho touched his hands before him in an attitude of prayer.

“Give the gentlemen a drink!” commanded Don Pablo severely, and after Hardy had accepted the gourd of cold water which the boy dipped from a porous olla, resting in the three-pronged fork of a trimmed mesquite, the old gentleman called for his tobacco. This the mozo brought in an Indian basket wrought by the Apaches who live across the river––Bull Durham and brown paper. The señor offered these to his guest, while Creede grinned in anticipation of the outcome.

“What?” exclaimed the Señor Moreno, astounded. “You do not smoke? Ah, perhaps it is my poor tobacco! But wait, I have a cigarro which the storekeeper gave me when I––No? No smoke nothing? Ah, well, well––no smoke, no Mexicano, as the saying goes.” He regarded his guest doubtfully, with a shadow of disfavor. Then, rolling a cigarette, he remarked: “You have a very white skin, Señor Hardy; I think you have not been in Arizona very long.”

“Only a year,” replied Hardy modestly.

“Muchacho!” cried the señor. “Run and tell the señora to hasten the dinner. And where,” he inquired, with the shrewd glance of a country lawyer, 67 “and where did you learn, then, this excellent Spanish which you speak?”

“At Old Camp Verde, to the north,” replied Hardy categorically, and at the name Creede looked up with sudden interest. “I lived there when I was a boy.”

“Indeed!” exclaimed Don Pablo, raising his eyebrows. “And were your parents with you?”

“Oh, yes,” answered Hardy, “my father was an officer at the post.”

“Ah, sí, sí, sí,” nodded the old man vigorously, “now I understand. Your father fought the Apaches and you played with the little Mexican boys, no? But now your skin is white––you have not lived long under our sun. When the Apaches were conquered your parents moved, of course––they are in San Francisco now, perhaps, or Nuevo York.”

“My father is living near San Francisco,” admitted Hardy, “but,” and his voice broke a little at the words, “my mother has been dead many years.”

“Ah, indeed,” exclaimed Don Pablo sympathetically, “I am very sorry. My own madre has been many years dead also. But what think you of our country? Is it not beautiful?”

“Yes, indeed,” responded Hardy honestly, “and you have a wonderful air here, very sweet and pure.”

“Seguro!” affirmed the old man, “seguro que sí! 68 But alas,” he added sadly, “one cannot live on air alone. Ah, que malo, how bad these sheep are!”

He sighed, and regarded his guest sadly with eyes that were bloodshot from long searching of the hills for cattle.

“I remember the day when the first sheep came,” he said, in the manner of one who begins a set narration. “In the year of ’91 the rain came, more, more, more, until the earth was full and the excess made lagunas on the plain. That year the Salagua left all bounds and swept my fine fields of standing corn away, but we did not regret it beyond reason for the grass came up on the mesas high as a horse’s belly, and my cattle and those of my friend Don Luís, the good father of Jeff, here, spread out across the plains as far as the eye could see, and every cow raised her calf. But look! On the next year no rain came, and the river ran low, yet the plains were still yellow with last year’s grass. All would have been well now as before, with grass for all, when down from the north like grasshoppers came the borregos––baaa, baaa, baaa––thousands of them, and they were starving. Never had I seen bands of sheep before in Arizona, nor the father of Don Jeff, but some say they had come from California in ’77, when the drought visited there, and had increased in Yavapai and fed out all the north country until, when this second año seco came 69 upon them, there was no grass left to eat. And now, amigo, I will tell you one thing, and you may believe it, for I am an old man and have dwelt here long: it is not God who sends the dry years, but the sheep!

“Mira! I have seen the mowing machine of the Americano cut the tall grass and leave all level––so the starved sheep of Yavapai swept across our mesa and left it bare. Yet was there feed for all, for our cattle took to the mountains and browsed higher on the bushes, above where the sheep could reach; and the sheep went past and spread out on the southern desert and were lost in it, it was so great.

“That was all, you will say––but no! In the Spring every ewe had her lamb, and many two, and they grew fat and strong, and when the grass became dry on the desert because the rains had failed again, they came back, seeking their northern range where the weather was cool, for a sheep cannot endure the heat. Then we who had let them pass in pity were requited after the way of the borregueros––we were sheeped out, down to the naked rocks, and the sheepmen went on, laughing insolently. Ay, que malo los borregueros, what devils they are; for hunger took the strength from our cows so that they could not suckle their calves, and in giving birth many mothers and their little ones died together. In that year we lost half our cows, Don Luís Creede and I, and those that 70 lived became thin and rough, as they are to this day, from journeying to the high mountains for feed and back to the far river for water.

“Then the father of Jeff became very angry, so that he lost weight and his face became changed, and he took an oath that the first sheep or sheep-herder that crossed his range should be killed, and every one thereafter, as long as he should live. Ah, what a buen hombre was Don Luís––if we had one man like him to-day the sheep would yet go round––a big man, with a beard, and he had no fear, no not for a hundred men. And when in November the sheep came bleating back, for they had promised so to do as soon as the feed was green, Don Luís met them at the river, and he rode along its bank, night and day, promising all the same fate who should come across––and, umbre, the sheep went round!”

The old man slapped his leg and nodded his head solemnly. Then he looked across at Creede and his voice took on a great tenderness. “My friend has been dead these many years,” he said, “but he was a true man.”

As Don Pablo finished his story the Señora opened the door of the kitchen where the table was already set with boiled beans, meat stewed with peppers, and thin corn cakes––the conventional frijoles, carne con chili, and tortillas of the Mexicans––and some fried 71 eggs in honor of the company. As the meal progressed the Señora maintained a discreet silence, patting out tortillas and listening politely to her husband’s stock of stories, for Don Pablo was lord in his own house. The big-eyed muchacho sat in the corner, watching the corn cakes cook on the top of the stove and battening on the successive rations which were handed out to him. There were stories, as they ate, of the old times, of the wars and revolutions of Sonora, wherein the Señor Moreno had taken too brave a part, as his wounds and exile showed; strange tales of wonders and miracles wrought by the Indian doctors of Altár; of sacred snakes with the sign of the cross blazoned in gold on their foreheads, worshipped by the Indians with offerings of milk and tender chickens; of primitive life on the haciendas of Sonora, where men served their masters for life and were rewarded at the end with a pension of beans and carne seco.

Then as the day waned they sat at peace in the ramada, Moreno and Creede smoking, and Hardy watching the play of colors as the sun touched the painted crags of the Bulldog and lighted up the square summit of Red Butte across the river, throwing mysterious shadows into the black gorge which split it from crown to base. Between that high cliff and the cleft red butte flowed the Salagua, 72 squirming through its tortuous cañon, and beyond them lay Hidden Water, the unknown, whither a single man was sent to turn back the tide of sheep.

In the silence the tinkle of bells came softly from up the cañon and through the dusk Hardy saw a herd of goats, led by a long-horned ram, trailing slowly down from the mesa. They did not pause, either to rear up on their hind feet for browse or to snoop about the gate, but filed dutifully into their own corral and settled down for the night.

“Your goats are well trained, Don Pablo,” said Hardy, by way of conversation. “They come home of their own accord.”

“Ah, no,” protested Moreno, rising from his chair. “It is not the goats but my goat dogs that are well trained. Come with me while I close the gate and I will show you my flock.”

The old gentleman walked leisurely down the trail to the corral, and at their approach Hardy saw two shaggy dogs of no breed suddenly detach themselves from the herd and spring defiantly forward.

“Quita se, quita se!” commanded Don Pablo, and at his voice they halted, still growling and baring their fangs at Hardy.

“Mira,” exclaimed the old man, “are they not bravo? Many times the borregueros have tried to steal my bucks to lead their timid sheep across the 73 river, but Tira and Diente fight them like devils. One Summer for a week the chivas did not return, having wandered far up into the mountains, but in the end Tira and Diente fetched them safely home. See them now, lying down by the mother goat that suckled them; you would not believe it, but they think they are goats.”

He laughed craftily at the idea, and at Hardy’s eager questions.

“Seguro,” he said, “surely I will tell you about my goat dogs, for you Americans often think the Mexicans are tonto, having no good sense, because our ways are different. When I perceived that my cattle were doomed by reason of the sheep trail crossing the river here at my feet I bought me a she-goat with kids, and a ram from another flock. These I herded myself along the brow of the hill, and they soon learned to rear up against the bushes and feed upon the browse which the sheep could not reach. Thus I thought that I might in time conquer the sheep, fighting the devil with fire; but the coyotes lay in wait constantly to snatch the kids, and once when the river was high the borregueros of Jeem Swopa stole my buck to lead their sheep across.