RURAL LIFE

AND THE RURAL SCHOOL

BY

JOSEPH KENNEDY

DEAN OF THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION IN THE

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH DAKOTA

Title: Rural Life and the Rural School

Author: Joseph Kennedy

Release date: August 3, 2009 [eBook #29600]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Peter Vachuska, Val Wooff and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Copyright, 1915, by

JOSEPH KENNEDY

copyright, 1915, in Great Britain

Rural Life and the Rural School

W. P. 2.

This volume is addressed to the men and women who have at heart the interests of rural life and the rural school. I have tried to avoid deeply speculative theories on the one hand, and distressingly practical details on the other; and have addressed myself chiefly to the intelligent individual everywhere—to the farmer and his wife, to the teachers of rural schools, to the public spirited school boards, individually and collectively, and to the leaders of rural communities and of social centers generally. I have tried to avoid the two extremes which Guizot says are always to be shunned, viz.: that of the "visionary theorist" and that of the "libertine practician." The former is analogous to a blank cartridge, and the latter to the mire of a swamp or the entangled underbrush of a thicket. The legs of one's theories (as Lincoln said of those of a man) should be long enough to reach the earth; and yet they must be free to move upon the solid ground of fact and experience. Details must always be left to the person who is to do the work, whether it be that of the teacher, of the farmer, or of the school officer.

I am aware that there is a veritable flood of books on this and kindred topics, now coming from the presses of the country. My sole reasons for the publication of the present volume are the desire to deliver the [Pg 4]message which has come to fruition in my mind, and the hope that it may reach and interest some who have not been benefited by a better and more systematic treatise on this subject.

By way of credential and justification, I would say that the message of the book has in large measure grown out of my own life and thought; for I was born and brought up in the country, there I received my elementary education, and there I remained till man grown. Practically every kind of work known on the farm was familiar to me, and I have also taught and supervised rural schools. These experiences are regarded as of the highest value, and I revert in memory to them with a satisfaction and affection which words cannot express.

If there should seem to be a note of despair in some of the earlier chapters as to the desired outcome of the problems of rural life and the rural school, it is not intended that such impression shall be complete and final. An attempt is made simply to place the problem and the facts in their true light before the reader. There has been much "palavering" on this subject, as there has been much enforced screaming of the eagle in many of our Fourth of July "orations." I feel that the first requisite is to conceive the problems clearly and in all seriousness.

If these problems are to be solved, true conceptions of values must be established in the social mind. Many present conceptions, like those of the personality of the teacher, standards for teaching, supervision, school equipment, salary, etc., must first be dis-established, and then higher and better ones substituted. There will have to be a genuine and intelligent "tackling" of the problems, and not, as has been the case too often, a mere playing with them. There will have to be some real statesmanship[Pg 5] introduced into the present laissez-faire spirit, attitude, and methods of American rural life and rural education. The nation in this respect needs a trumpet call to action. There is need of a chorus, loud and long, and if the small voice of the present discussion shall add only a little—however little—to this volume of sound, there will be so much of gain. This is my aim and my hope.

JOSEPH KENNEDY

The University of North Dakota

| CHAPTER I | RURAL LIFE | 9 | |

| A generation ago; Chores and work; Value of work; Extremes; Yearly routine; Disliked in comparison; Other hard jobs; Harvesting; Threshing; Welcome events; Winter work; What the old days lacked; The result; The backward rural school; Women's condition unrelieved; The rural problem must be met; Facilities. | |||

| CHAPTER II | THE URBAN TREND | 19 | |

| Cityward; Attractive forces; Conveniences in cities; Urbanized literature; City schools; City churches; City work preferred; Retired farmers; Educational centers; Face the problem; Educational value not realized; Wrong standard in the social mind; Rural organization; Playing with the problem. | |||

| CHAPTER III | THE REAL AND THE IDEAL SCHOOL | 28 | |

| The building; No system of ventilation; The surroundings; The interior; Small, dead school; That picture and this; Architecture of building; Get expert opinion; Other surroundings; Number of pupils; It will not teach alone; The teacher; A good rural school; The problem. | |||

| CHAPTER IV | SOME LINES OF PROGRESS | 38 | |

| Progress; In reaping machines; The dropper; The hand rake; The self rake; The harvester; The wire binder; The twine binder; Threshing machine; The first machine; Improvements; The steam engine; Improvements in ocean travel; From hand-spinning to factory; The cost; Progress in higher education; Progress in normal schools; Progress in agricultural colleges; Progress in the high schools; How is the rural school? | |||

| CHAPTER V | A BACKWARD AND NEGLECTED FIELD | 49 | |

| Rural schools the same everywhere; Rural schools no better than formerly; Some improvements; Strong personalities in the older schools; More men needed; Low standard now; The survival of the unfittest; Short terms; Poor supervision; No decided movement; Elementary teaching not a profession; The problem difficult, but before us; Other educational interests should help; Higher standards necessary; Courses for teachers; The problem of compensation; Consolidation as a factor; Better supervision necessary; A model rural school; The teacher should lead; A good boarding place. | |||

| CHAPTER VI | CONSOLIDATION OF RURAL SCHOOLS | 63 | |

| The process; When not necessary; The district system; The township system; Consolidation difficult in district system; Easier in township system; Consolidation a special problem for each district; Disagreements on transportation; Each community must decide for itself; The distance to be transported; Responsible driver; Cost of consolidation; More life in the consolidated school; Some grading desirable; Better teachers; Better buildings and inspection; Longer terms; Regularity, punctuality, and attendance; Better supervision; The school as a social center; Better roads; Consolidation coming everywhere; The married teacher and permanence. | |||

| CHAPTER VII | THE TEACHER | 77 | |

| The greatest factor; What education is; What the real teacher is; A hypnotist; Untying knots; Too much kindness; The button illustration; The chariot race; Physically sound; Character; Well educated; Professional preparation; Experience; Choosing a teacher; A "scoop"; What makes the difference; A question of teachers. | |||

| CHAPTER VIII | THE THREE INSEPARABLES | 88 | |

| The "mode"; The "mode" in labor; The "mode" in educational institutions; No "profession"; Weak personalities; Low standard; The norm of wages too low; The inseparables; Raise the standard first; More men; Coöperation needed; The supply; Make it fashionable; The retirement system; City and country salaries—effects; The solution demands more; A good school board; Board and teacher; The ideal. | |||

| CHAPTER IX | THE RURAL SCHOOL CURRICULUM | 100 | |

| Imitation; The country imitates the city; Textbooks; An interpreting core; Rural teachers from the city; A course for rural teachers; All not to remain in the country; Mere textbook teaching; A rich environment; Who will teach these things?; The scientific spirit needed; A course of study; Red tape; Length of term; Individual work; "Waking up the mind"; The overflow of instruction; Affiliation; The "liking point"; The teacher, the chief factor. | |||

| CHAPTER X | THE SOCIAL CENTER | 114 | |

| The teacher, the leader; Some community activities; The literary society; Debates; The school program; Spelling schools; Lectures; Dramatic performances; A musical program; Slides and moving pictures; Supervised dancing; Sports and games; School exhibits; A public forum; Courtesy and candor; Automobile parties; Full life or a full purse; Organization; The inseparables. | |||

| CHAPTER XI | RURAL SCHOOL SUPERVISION | 127 | |

| Important; Supervision standardizes; Supervision can be overdone; Needed in rural schools; No supervision in some states; Nominal supervision; Some supervision; An impossible task; The problem not tackled; City supervision; The purpose of supervision; What is needed; The term; Assistants; The schools examined; Keep down red tape; Help the social centers; Conclusion. | |||

| CHAPTER XII | LEADERSHIP AND COÖPERATION | 139 | |

| The real leader; Teaching vs. telling; Enlisting the coöperation of pupils; Placing responsibility; How people remain children; On the farm; Renters; The owner; The teacher as a leader; Self-activity and self-government; Taking laws upon one's self; An educational column; All along the educational line. | |||

| CHAPTER XIII | THE FARMER AND HIS HOME | 152 | |

| Farming in the past; Old conceit and prejudice; Leveling down; Premises indicative; Conveniences by labor-saving devices; Eggs in several baskets; The best is the cheapest; Good work; Good seed and trees; A good caretaker; Family coöperation; An ideal life. | |||

| CHAPTER XIV | THE RURAL RENAISSANCE | 160 | |

| Darkest before the dawn; The awakening; The agricultural colleges; Conventions; Other awakening agencies; The farmer in politics; The National Commission; Mixed farming; Now before the country; Educational extension; Library extension work; Some froth; Thought and attitude. | |||

| CHAPTER XV | A GOOD PLACE AFTER ALL | 169 | |

| Not pessimistic; Fewer hours of labor than formerly; The mental factor growing; The bright side of old-time country life; The larger environment; Games; Inventiveness in rural life; Activity rather than passivity; Child labor; The finest life on earth. | |||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 182 | ||

| INDEX | 187 | ||

It is only within the past decade that rural life and the rural school have been recognized as genuine problems for the consideration of the American people. Not many years ago, a president of the United States, acting upon his own initiative, appointed a Rural School Commission to investigate country life and to suggest a solution for some of its problems. That Commission itself and its report were both the effect and the cause of an awakening of the public mind upon this most important problem. Within the past few years the cry "Back to the country" has been heard on every hand, and means are now constantly being proposed for reversing the urban trend, or at least for minimizing it.

A Generation Ago.—Rural life, as it existed a quarter of a century or more ago, was extremely severe and indeed to our mind quite repellent. In those days—and no doubt they are so even yet in many places—the conditions were too often forbidding and deterrent.[Pg 10] Otherwise how can we explain the very general tendency among the younger people to move from the country to the city?

Chores and Work.—The country youth, a mere boy in his teens, was, and still is, compelled to rise early in the morning—often at four o'clock—and to go through the round of chores and of work for a long day of twelve to fifteen hours. First, after rising, he had his team to care for, the stables were to be cleaned, cows to be milked, and hogs and calves to be fed.

After the chores were done the boy or the young man had to work all day at manual labor, usually close to the soil; he was allowed about one hour's rest at dinner time; in the evening after a day's hard labor, he had to perform the same round of chores as in the morning so that there was but a short time for play and recreation, if he had any surplus energy left. He usually retired early, for he was fatigued and needed sleep and rest in order to be refreshed for the following day, when he very likely would be required to repeat the same dull round.

Value of Work.—Of course work is a good thing. A moderate and reasonable amount of labor is usually the salvation of any individual. No nation or race has come up from savagery to civilization without the stimulating influence of labor. It is likewise true that no individual can advance from the savagery of childhood to the civilization of adult life except through work of some kind. Work in a reasonable amount is a[Pg 11] blessing and not a curse. It is probably due to this fact that so many men in our history have become distinguished in professional life, in the forum, on the bench, and in the national Congress; in childhood and youth they were inured to habits of work. This kept them from temptation, and endowed them with habits of industry, of concentration, and of purpose. The old adage that "Satan finds some mischief still for idle hands to do," found little application in the rural life of a quarter of a century ago.

Extremes.—Even with all its unrecognized advantages, the fact remains that farm life has been quite generally uninteresting to the average human being. There are individuals who become so accustomed to hard work that the habit really grows to be pleasant. This, no doubt, often happens. Habit accustoms the individual to accommodate himself to existing conditions, no matter how severe they may be. A very old man who was shocking wheat under the hot sun of a harvest day was once told that it must be hard work for him. He replied, "Yes, but I like it when the bundles are my own." So the few who are interested and accustomed by habit to this kind of life may enjoy it, but to the great majority of people the conditions would be decidedly unattractive.

Yearly Routine.—The yearly routine on the farm used to be about as follows: In early spring, before seeding time had come, all the seed wheat had to be put through the fanning mill. The seed was sown[Pg 12] by hand. A man carried a heavy load of grain upon his back and walked from one end of the field to the other, sowing it broadcast as he went. After the wheat had been sown, plowing for the corn and potatoes was begun and continued. These were all planted by hand, and when they came above ground they were hoed by hand and cultivated repeatedly by walking and holding the plow.

Disliked in Comparison.—All of this work implies, of course, that the person doing it was close to the soil; in fact, he was in the soil. He wore, necessarily, old clothes somewhat begrimed by dirt and dust. His shoes or boots were heavy and his step became habitually long and slow. Manual labor too frequently carries with it a neglect of cleanliness. The laborer on the farm necessarily has about him the odor of horses, of cows, and of barns. Such conditions are not bad, but they are nevertheless objectionable, when compared with the neatness and cleanliness of the clerk in the bank or behind the counter. We do not write these words in any spirit of disparagement, but merely from the point of view at which many young people in the country view them. We are trying to face the truth in order to understand the problem to be solved. It is essential to look at the situation squarely and to view it steadily and honestly. Hiding our heads in the sand will not clarify our vision.

Other Hard Jobs.—The next step in the yearly round was haymaking. Frequently, the grass was[Pg 13] cut with scythes. In any event the work of raking, curing, and stacking the hay, or the hauling it and pitching it into the barns was heavy work. There was no hayfork operated by machinery in those days. When not haying, the youth was usually put to summer-fallowing or to breaking new ground, to fencing or splitting rails,—all heavy work. No wonder that he always welcomed a rainy day!

Harvesting.—Then came the wheat-harvest time. Within the memory of the author some of the grain was cut with cradles; later, simple reaping machines of various kinds were used; but with them went the binding, shocking, and stacking, all performed by hand and all arduous pieces of work. These operations were interspersed with plowing and threshing. Then came corn cutting, potato digging, and corn husking.

Threshing.—In those days most of the work around a threshing machine was also done by hand. There was no self-feeding apparatus and no band-cutting device; there was no straw-blower and no measuring and weighing attachments. It usually required about a dozen "hands" to do all the work. These men worked strenuously and usually in dusty places. The only redeeming feature of the business was the opportunity given for social intercourse which accompanied the work. Men, being social by instinct, always work more willingly and more strenuously when others are with them.[Pg 14]

Welcome Events.—It is quite natural, as we have said, that under such conditions as these the youth longed for a rainy day. A trip to the city was always a delightful break in the monotony of his life, and a short respite from severe toil. Sunday was usually the only social occasion in rural life. It was always welcome, and the boys, even though tired physically from work during the week, usually played ball, or went swimming, or engaged in other sports on Sunday afternoons. Living in isolation all the week and engaged in hard labor, they instinctively craved companionship and society.

Winter Work.—When the fall work was done, winter came with its own occupations. There were usually about four months of school in the rural district, but even during this season there was much manual labor to be done. Trees were to be cut down and wood was to be chopped, sawed, and split for the coming summer. Land frequently had to be cleared to make new fields; the breaking of colts and of steers constituted part of the sport as well as of the labor of that season of the year.

What the Old Days Lacked.—There was little or no machinery as a factor in the rural life of days gone by. In these modern times, of course, many things have made country life more attractive than formerly. Twenty-five years ago there was no rural delivery, no motor cycle, no automobile; even horses and buggies were somewhat of a luxury, for in the remote country[Pg 15] districts the ox team or "Shanks' mares" formed the usual mode of travel.

The Result.—It is little wonder that under such circumstances discontent arose and that people who by nature are sociable longed to go where life was, in their opinion, more agreeable. Even with all the later conveniences and improvements, the trend cityward still continues and may continue indefinitely in the future. The American people may as well face the facts as they are. It is difficult if not impossible to make the country as attractive to young people as is the city; and consequently to reverse or even stop the urban trend will be most difficult. Indeed, some of the things which make rural life pleasant, like the automobile, favor this trend, which probably will continue until economic pressure puts on the brakes. Even now, with all our improvements, the social factors in rural life are comparatively small. Here is one of our greatest problems: How to increase the fullness of social life in rural communities so as to make country life and living everywhere more attractive.

The Backward Rural School.—Although the material conditions and facilities for work have improved by reason of various inventions in recent years, the rural school of former days was frequently as good as, if not better in some respects than, the school of to-day. Formerly there were many able men engaged in teaching who could earn as much in the schoolroom as they could earn elsewhere. There were consequently in the rural[Pg 16] schools many strong personalities, both men and women. Since that time new opportunities and callings have developed so rapidly that some of the most capable people have been enticed into other and more profitable callings, and the schools are left in a weakened condition by reason of their absence.

Women's Condition Unrelieved.—With all our improvements and conveniences, the work of women in country communities has been relieved but little. Farm life has always been and still is a hard one for women. It has been, in many instances, a veritable state of slavery; for women in the country have always been compelled to do not only their own proper work, but the work of two or three persons. The working hours for women are even longer than those for men; for breakfast must be prepared for the workmen, and household work must be done after the evening meal is eaten. It is little to be wondered at that women as a rule wish to leave the drudgery of rural life. Under the improved conditions of the present day, with all kinds of machinery, the work of women is lightened least.[1]

The Rural Problem Must Be Met.—I have given a short description of rural life in order to have a setting for the rural school. The school is, without doubt, the center of the rural life problem, and we[Pg 17] are face to face with it for a solution of some kind. The problems of both have been too long neglected. Now forced upon our attention, they should receive the thoughtful consideration of all persons interested in the welfare of society. They are difficult of solution, probably the most difficult of all those which our generation has to face. They involve the reduction of the repellent forces in rural life and the increase of such forces and agencies as will be attractive, especially to the young. The great problem is, how can the trend cityward be checked or reversed?

What attractions are possible and feasible in the rural communities? In each there should be some recognized center to provide these various attractions. There should be lectures and debates, plays of a serious character, musical entertainments, and social functions; even the moving picture might be made of great educational value. There is no reason why the people in the country are not entitled to all the satisfying mental food which the people of the city enjoy. These things can be secured, too, if the people will only awake to a realization of their value, and will show their willingness to pay for them. Something cannot be secured for nothing. In the last resort the solution of most problems, as well as the accomplishment of most aims, involves the expenditure of money. Wherever the people of rural communities have come to value the finer educational, cultural, civilizing, and intangible things more than they value money, the[Pg 18] problem is already being solved. It is certainly a question of values—in aims and means.

Facilities.—Many inventions might be utilized on the farm to better advantage than they are at present. But people live somewhat isolated lives in rural communities and there is not the active comparison or competition that one finds in the city; improvements of all kinds are therefore slower of realization. Values are not forced home by every-day discussion and comparison. People continue to do as they have been accustomed to do, and there are men who own large farms and have large bank accounts who continue to live without the modern improvements, and hence with but few comforts in life. A greater interest in the best things pertaining to country life needs to be awakened, and to this end rural communities should be better organized, socially, economically, and educationally.

[1] There is an illuminating article, entitled "The Farmer and His Wife," by Martha Bensley Bruère in Good Housekeeping Magazine, for June, 1914, p. 820.

In the preceding chapter we discussed those forces at work in rural life which tend to drive people from the farm to the city. It was shown that, on the whole, up to the present at least, farm life has not been as pleasant as it should or could be made. Some aspects of it are uncomfortable, if not painful. Hard manual labor, long hours of toil, and partial isolation from one's fellows usually and generally characterize it. Of course, there are many who by nature or habit, or who by their ingenuity and thrift, have made it serve them, and who therefore have come to love the life of the country; but we are speaking with reference to the average men and women who have not mastered the forces at hand, which can be turned to their service only by thought and thrift.

Cityward.—The trend toward the cities is unmistakable. So alarming has it become that it has aroused the American people to a realization that something must be done to reverse it or at least to minimize it. At the close of the Revolutionary War only three per cent of the total population of our country lived in what could be termed cities. In 1810 only about five[Pg 20] per cent of the whole population was urban; while in 1910 forty-six per cent of our people lived in cities. This means that, relatively, our forces producing raw materials are not keeping pace with the growth and demands of consumption. In some of the older Atlantic states, as one rides through the country, vast areas of uncultivated land meet the view. The people have gone to the city. Large cities absorb smaller ones, and the small towns absorb the inhabitants of the rural districts. Every city and town is making strenuous efforts to build itself up, if need be at the expense of the smaller towns and the rural communities. To "boom" its own city is assumed to be a large and legitimate part of the business of every commercial club. This must mean, of course, that smaller cities and towns and the rural communities suffer accordingly in business, in population, and in life.

Attractive Forces.—The attractive forces of the city are quite as numerous and powerful as the repellent forces of the country. The city is attractive from many points of view. It sets the pace, the standard, the ideals; even the styles of clothing and dress originate there. It is where all sorts of people are seen and met with in large numbers; its varied scenes are always magnetic. Both old and young are attracted by activities of all kinds; the "white way" in every city is a constant bid for numbers. In the city there is always more liveliness if not more life than in the country. Activity is apparent everywhere. Everything[Pg 21] seems better to the young person from the country; there is more to see and more to hear; the show windows and the display of lighting are a constant lure; there is an endless variety of experiences. Life seems great because it is cosmopolitan and not provincial or local. In any event, it draws the youth of the country. Things, they say, are doing, and they long to be a part of it all. There is no doubt that the mind and heart are motivated in this way.

Conveniences in Cities.—In the city there are more conveniences than in the country. There are sidewalks and paved streets instead of muddy roads; there are private telephones, and the telegraph is at hand in time of need; there are street cars which afford comfortable and rapid transportation. There are libraries, museums, and art galleries; there are free lectures and entertainments of various kinds; and the churches are larger and more attractive than those in the country. As in the case of teachers, the cities secure their pick of preachers. Doctors are at hand in time of need, and all the professions are centered there. Is it any wonder that people, when they have an opportunity, migrate to the city? There is a social instinct moving the human heart. All people are gregarious. Adults as well as children like to be where others are, and so where some people congregate others tend to do likewise. Country life as at present organized does not afford the best opportunity for the satisfaction of this social instinct. The great variety of social attractions[Pg 22] constitutes the lure of the city—it is the powerful social magnet.

Urbanized Literature.—Most books, magazines, and papers are published in cities, hence most of them have the flavor of city life about them. They are made and written by people who know the city, and the city doings are usually the subject matter of the literary output of the day. Children acquire from these, even in their primary school days, a longing for the city. The idea of seeing and possibly of living in the city becomes "set," and it tends sooner or later to realize itself in act and in life.

City Schools.—The city, as a rule, maintains excellent schools; and the most modern and serviceable buildings for school purposes are found there. Urban people seem willing to tax themselves to a greater extent; and so in the cities will be found comparatively better buildings, better teachers, more and better supervision, more fullness of life in the schools. Usually in the cities the leading and most enterprising men and women are elected to the school board, and the people, as we have said, acquiesce in such taxation as the board deems necessary. Cities endeavor to secure the choice of the output of normal schools, regardless of the demands of rural districts. Every city has a superintendent, and every building a principal; while, in the country, one county superintendent has to supervise a hundred or more schools, situated too, as they are, long distances apart.[Pg 23]

City Churches.—Something similar may be said with respect to the churches. In every city there are several, and people can usually go to the church of their choice. In many parts of the country the church is decadent, and in some places it is becoming extinct. Even the automobile contributes its influence against the country church as a rural institution, and in favor of the city; for people who are sufficiently well-to-do often like to take an automobile ride to the city on Sunday.

City Work Preferred.—Workingmen and servant girls also prefer the city. They dislike the long irregular hours of the country; they prefer to work where the hours are regular, where they do not come into such close touch with the soil, and where they do not have to battle with the elements. In the city they work under shelter and in accordance with definite regulations. Hence it is that the problem of securing workingmen and servant girls in the country is every day becoming more and more perplexing.

Retired Farmers.—Farmers themselves, when they have become reasonably well-to-do, frequently retire to the city, either to enjoy life the rest of their days or to educate their children. Individuals are not to be blamed. The lack of equivalent attractions and conveniences in the country is responsible.

Educational Centers.—As yet, it is seldom that good high schools are found in the country. To secure a high school education country people frequently have to avail themselves of the city schools. Many[Pg 24] colleges and universities are located in the cities and, consequently, much of the educational trend is in that direction.

Face the Problem.—The rural problem is a difficult one and we may as well face the situation honestly and earnestly. There has been too much mere oratory on problems of rural life. We have often, ostrich-like, kept our heads under the sand and have not seen or admitted the real conditions, which must be changed if rural life is to become attractive. Say what we will, people will go where their needs are best satisfied and where the attractions are greatest. People cannot be driven—they must be attracted and won. If "God made the country and man made the town," God's people must be neglecting to give God's country "such a face and such a mien as to be loved needs only to be seen." Where the element of nature is largest there should be a more truly and deeply attractive life than where the element of art predominates, however alluring that may be. How can country life and the country itself be made to attract?

Educational Value Not Realized.—People generally have never been able to estimate education fairly. The value of lands, horses, and money can easily be measured, for these are tangible things; but education is very difficult of appraisal, for it is intangible. Yet it is true that intangible things are frequently of greater worth than are tangible things. There are men who pay more to a jockey to train their horses[Pg 25] than they are willing to pay to a teacher to train their children. This is because the services of the jockey are more easily reckoned. The effects or results of the horse training are measured by the proceeds in dollars and cents on the racetrack, and so are easily realized; while the growth in education, refinement, and culture on the part of the child is difficult indeed to measure or estimate. And yet how much more valuable it is! The jockey gives the one, the teacher the other.

Wrong Standard in the Social Mind.—In some rural communities the idea exists that a teacher is worth about fifty dollars a month—perhaps not so much. This idea has been encouraged until it has been too generally accepted; and in many places the notion prevails that if a teacher is receiving more than that amount, she is being overpaid, and the school board is accused of extravagance. The rural school problem will never be solved until the standard of compensation is readjusted. There are many persons in the cities, who, for the performance of socially unimportant things, are receiving larger salaries than are usually paid to university professors and college presidents. Thus, the relative values of services are misjudged and the recompense of labor is not properly graded and proportioned. Unless there is, quite generally, a saner perspective in the social mind and until values are reëstimated, the solution of the rural school problem and indeed of many problems of rural life is well-nigh hopeless.[Pg 26] Before a solution is effected sufficient inducement must be held out to more strong persons to come into the rural life and into the rural schools. These persons would and could be leaders of strength among the people.

Rural Organization.—Until recently there has been little or no organization of rural life. Communities have been chaotic, socially, economically, and educationally. Real leaders have been wanting—men and women of strong and winning personality. The rural teacher, if he were a man of power and initiative, often proved to be a real savior and redeemer of social life in his community. But leaders of this type cannot now be secured without a reasonable incentive. Such men will seldom sacrifice themselves for the organization and uplift of a community except for proper compensation. If teachers—or at least the strong ones—were paid two or three times as much as they are to-day, and if the standards were raised accordingly, so as to secure really strong personalities as teachers, country life might be organized in different directions and made so much more attractive than at present, that the urban trend would be arrested or greatly minimized.

Playing with the Problem.—The possibilities of the organization of rural life and rural schools have not yet been realized; as a people we have really played with this problem. It has taken care of itself; it has been allowed to drift. Rural life at present is a kind of easy social adjustment on the basis of the minimum[Pg 27] of expense and of exertion toward a solution. We have not realized the value of genuine social, economic, and educational organization with all the activities in these lines which the terms imply. We have not grappled with the problem in an earnest, scientific way; we have never thought out systematically what is needed, and then decided to employ the necessary means to bring about the desired end. It may be that the problem will remain unsolved for generations to come; but if country life and country schools are to be made as attractive and pleasant as city life and city schools, the people will have to face the problem without flinching and use the only means which will bring about the desired result. The problem could be easily solved if the people realized the true value of rural life and of good rural schools. Where there is a will there is a way; but where there is no will there is no possible way. Country life can be made fully as pleasant as city life, and the rural schools can be made fully as good as the city schools. Of course some things will be lacking in the country which are found in the city; but, conversely, many things and probably better things will be found in the country than could be found in the city.

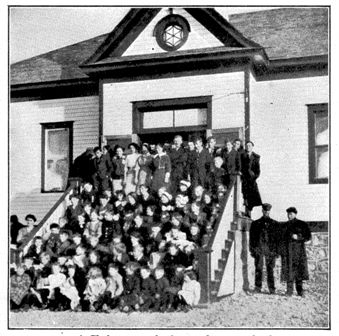

This chapter will have reference to the one-room rural school as it has existed in the past and as it still exists in many places; it will also discuss the rural school as it ought to be. It is assumed that, although consolidation is spreading rapidly, the one-room rural school as an institution will continue to exist for an indefinite time. Under favorable conditions it probably should continue to exist; for, as we shall see, it has many excellent features which are real advantages.

The Building.—The old-fashioned country schoolhouse was in many respects a pitiable object. The "little red schoolhouse" in story and song has been the object of much praise. As an ideal creation it may be deserving of admiration, but this cannot be asserted of it as a reality. The common type was an ordinary box-shaped building without architecture, without a plan, and, as a rule, without care or repair. Frequently it stood for years without being repainted, and in the midst of chaotic and ill-cared-for surroundings. The contract for building it was usually awarded to some carpenter who was also given carte blanche to do as he[Pg 29] pleased in regard to its construction, the only provision being that he keep within the amount of money allowed—probably eight hundred or a thousand dollars. The usual result was the plainest kind of building, without conveniences of any kind. If a blackboard were provided in the specifications (which were often oral rather than written), it was perhaps placed in such a position as to be useless. In the course of my experience as county superintendent of schools, I once visited a rural school in which the blackboard began at the height of a man's head and extended to the ceiling, the carpenter probably thinking that its one purpose was to display permanently the teacher's program.

No System of Ventilation.—No system of ventilation was provided in former days, and in some schoolhouses such is the condition to-day. Nevertheless, within the past fifteen years, there has been a gratifying improvement in this direction. It used to be necessary to secure fresh air, if at all, by opening windows. In some sections, where the climate is mild, this is the best method of ventilation; but certainly, in northern latitudes where the winters are long and cold, some system of forced or automatic ventilation should be provided. It may not be amiss to assert that it would be an excellent plan to decide first upon a good system of ventilation and then to build the schoolhouse around it. Without involving great expense there are simple systems of ventilation and heating combined[Pg 30] which are very efficient for such houses. In former times, and in some places even yet, the usual method of heating was by an unjacketed stove which made the pupils who sat nearest it uncomfortably warm, while those in the farther corners were shivering with cold. With new systems of ventilation there is an insulating jacket which equalizes the temperature of the room by heating the fresh air and distributing it evenly.

It is strange how slowly people change their habits and even their opinions. Many are ignorant of the fact that in an unventilated schoolroom each child is breathing over and over again an atmosphere vitiated by the air exhaled from the lungs of every child in the room. The fact that twenty to forty pupils are often housed in poorly-ventilated schools accounts for much sickness and disease among country children. Whatever it is that makes air "fresh," and healthful, that factor is not found under the conditions described. Changes in the temperature and movement of the air are, no doubt, important in securing a healthful physiological reaction, but air contaminated and befouled by bodies and lungs has stupefying effects which cannot be ignored. Frequent change of air is essential.

The Surroundings.—The typical country schoolhouse, as it existed in the past, and as it frequently exists to-day, has not sufficient land to form a good yard and a playground appropriate for its needs. The farmer who sold or donated the small tract of land often plows almost to the very foundation walls.[Pg 31] There are usually no trees near by to afford shelter or to give the place a homelike and attractive appearance. Some trees may have been planted, but owing to neglect they have all died out, and nothing remains but a few dead and unsightly trunks. There is usually no fence around the school yard, and the outbuildings are frequently a disgrace, if not a positive menace to the children's morals. If a choice had to be made it would be better to allow children to grow up in their native liberty and wildness without a school "education" than to have them subjected to mental and moral degradation by the vicious suggestions received in some of these places. Weak teachers have a false modesty in regard to such conditions and school boards are often thoughtless or negligent.

The Interior.—Within the building there is frequently no adequate equipment in the way of apparatus, supplementary reading, or reference books of any kind. There are no decorations on the walls except such as are put there by mischievous children. The whole situation both inside and out brings upon one a feeling of desolation. Men and women who live in reasonably comfortable homes near by allow the school home of their precious children to remain for years unattractive and uninspiring in every particular. Again this is the result of ignorance, thoughtlessness, or negligence—a negligence that comes alarmingly close to guilt.

Small, Dead School.—In many a lone rural schoolhouse[Pg 32] may be found ten to twenty small children; and behind the desk a teacher holding only a second or third grade elementary or county certificate. The whole institution is rather tame and weak, if not dead; it is anything but stimulating (and if education means anything it means stimulation). It is this kind of situation which has led in recent years to a discussion of the rural school as one of the problems most urgently demanding the attention of society.

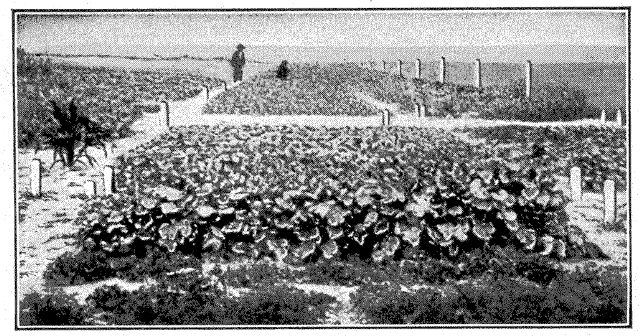

That Picture and This.—Let us now consider, after looking upon that picture, what the situation ought to be. In the first place, there should be a large school ground, or yard—not less than two acres. The schoolhouse should be properly located in this tract. The ground as a whole should be platted by a landscape architect, or at least by a person of experience and taste. Trees of various kinds should be planted in appropriate places, and groups of shrubbery should help to form an attractive setting. The school grounds should have a serviceable fence and gate and there should be a playground and a school garden.

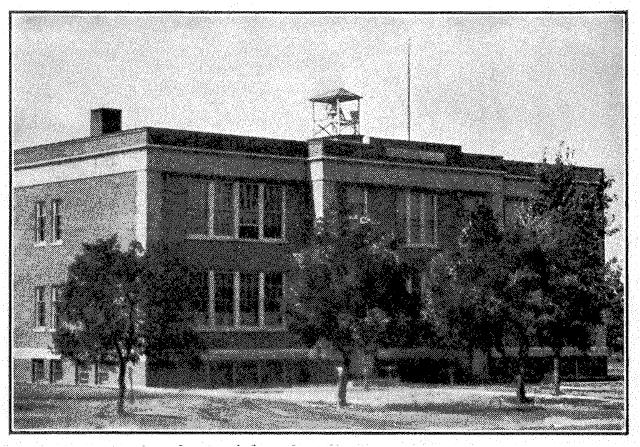

Architecture of Building.—No school building should be erected that has not first been planned or passed upon by an architect; this is now required by law in some states. A building with handsome appearance and with appropriate appointments is but a trifle, if any, more costly than one that has none. Art of all[Pg 33] kinds is a valuable factor in the education of children and of people generally; and a building, beautiful in construction, is no exception to the rule. Every person is educated by what impresses him. It is only within the last few years that much attention has been given to the necessity of special architecture in schoolhouses.

Men of intelligence sometimes draw up their own plans for a building and then, having become enamored of them, proceed to construct a residence or a schoolhouse along those lines. If they had shown their plans to an architect of experience he would probably have pointed out numerous defects which would have been admitted as soon as observed. Neither the individual nor the district school boards can afford, in justice to themselves and the community they represent, to ignore the wide and varied knowledge of the expert.

Get Expert Opinion.—Expert opinion should govern in the matter of heating and ventilating, in the kind of seating, in the arrangement of blackboards, in the decorations, and in all such technical and professional matters. Every rural school should have a carefully selected library, suited to its needs, including a sufficient number of reference books. The pupils should have textbooks without delay so that no time may be wasted in getting started after the opening of school. The walls should be adorned with a few appropriate and beautiful pictures.[Pg 34]

Other Surroundings.—On this school ground there should be a shop of some kind. The resourceful teacher would find a hundred uses for some such center of work. The closets should be so placed and so devised as to be easily supervised. This would prevent them from being moral plague spots, as is too often the case, as we have already said. There should be stables for sheltering horses, if the school is, as it should be, a social center for the community. There should be a flagpole in front of the schoolhouse, from the top of which the stars and stripes should be often unfurled to the breeze.

Number of Pupils.—In this architecturally attractive building, amid beautiful surroundings both inside and out, there should be, in order to have a good rural school, not less than eighteen or twenty pupils. Where there are fewer the school should be consolidated with a neighboring school. Twenty pupils would give an assurance of educational and social life, instead of the dead monotony which often prevails in the smaller rural school. There should be, during the year, at least eight, and preferably nine, months of school work.

It Will Not Teach Alone.—But with all of these conditions the school may still be far from effective. All the material equipment—the total environment of the pupils, both inside and outside the building—may be excellent, and still we may fail to find there a good school. Garfield said of his old teacher that Mark Hopkins on one end of a log and a pupil on the other[Pg 35] made the best kind of college. This indicates an essential factor other than the physical equipment.

I remember being once in a store when a man who had bought a saw a few days previously returned it in a wrathful mood. He was angry through and through and declared that the saw was utterly worthless. He had brought it back to reclaim his money. The merchant had a rich vein of humor in his nature and he listened smilingly to the outburst of angry language. Then he merely took the saw, opened his till and handed the man his money, quietly asking, with a twinkle in his eyes for those standing around, "Wouldn't it saw alone?"

Now, we may have a fine school ground, or site, with a variety of beautiful trees and clumps of shrubbery; we may have a playground and a school garden; we may have it all splendidly fenced; the schoolhouse may have an artistic appearance and may be kept in excellent repair; it may be well furnished inside with blackboards, seats, library, reference books, good textbooks, and all else that is needed; it may be beautifully decorated; it may have twenty or even more pupils, and yet we may not have a good school. It will not "saw alone"; the one indispensable factor may still be lacking.

The Teacher.—"As is the teacher, so is the school." Mark Hopkins on the end of a log made a good college, compared with the situation where the building is good and the teacher poor. The teacher is like the[Pg 36] mainspring in a watch. Without a good teacher there can be no good school. Live teacher, live school; dead teacher, dead school. The teacher and the school must be the center of life, of thought, and of conversation, in a good way, in the neighborhood. The teacher is the soul of the school; the other things constitute its body. What shall it profit a community to have a great building and lack a good teacher?

If we were obliged to choose between a good teacher and poor material conditions and environment on the one hand, and excellent material conditions and environment and a poor teacher on the other, we should certainly not hesitate in our choice.

A Good Rural School.—Now, if we suppose a really good teacher under the good conditions described above, we shall have a good rural school. There is usually better individual work done in such a school than is possible in a large system of graded schools in a city. In such a school there is more single-mindedness on the part of pupils and teacher. These pupils bring to such a school unspoiled minds, minds not weakened by the attractions and distractions, both day and night, of city life. In such a school the essentials of a good education are, as a rule, more often emphasized than in the city. There is probably a truer perspective of values. Things of the first magnitude are distinguished from things of the second, fifth, or tenth magnitude. This inability to distinguish magnitudes is one of the banes of common school[Pg 37] education everywhere—so many things are appraised at the same value.

The Problem.—We have tried in this discussion to put before the reader a fairly accurate picture, on the one hand, of the undesirable conditions which have too often prevailed, and, on the other, of a rural school which would be an excellent place in which to receive one's elementary education. The reader is asked to "look here, upon this picture, and on this." The transition from the one to the other is one of the great problems of rural life and of the rural school. Consolidation of schools, which we shall discuss more at length in a later chapter, will help to solve the problem of the rural school, and we give it our hearty indorsement. It is the best plan we know of where the conditions are favorable; but it is probable that the one-room rural school will remain with us for a long time to come. Indeed there are some good reasons why it should remain. Where the good rural school exists, whether non-consolidated or consolidated, it should be the center and the soul of rural life in that community—social, economical, and educational.

Progress.—The period covering the last sixty or seventy-five years has seen greater progress in all material lines than any other equal period of the world's history. Indeed, it is doubtful if a similar period of invention and progress will ever recur. It has been one of industrial revolution in all lines of activity.

In Reaping Machines.—Let us for a few moments trace this development and progress in some specific fields. Within the memory of many men now living the hand sickle was in common use in the cutting of grain. In the fifties and sixties the cradle was the usual implement for harvesting wheat, oats, and similar grains. One man did the cradling and another the gathering and the binding into sheaves. Then came rapid development of the reaping machine.

The "Dropper."—The most important step was probably the invention of the sickle-bar, a slender steel bar having V-shaped sections attached, to cut the grass and grain; this was pushed and pulled between what are called guards, by means of a rod called the "Pitman rod," attached to a small revolving wheel run by the gearing of the machine. This was a wonderful[Pg 39] invention and its principle has been extensively applied. The first reaping machine using the sickle and guard device was known as the "dropper." A reel, worked by machinery, revolved at a short distance above the sickle, beating the wheat backward upon a small platform of slats. This platform could be raised and lowered by the foot, by means of a treadle. When there was sufficient grain on this slat-platform it was lowered and the wheat was left lying in short rows on the ground, behind the machine. The bundles had to be bound by hand and removed before the machine could make the next round. This machine, though simple, was the forerunner of other important inventions.

The Hand Rake.—The next type of machine was the one in which the platform of slats was replaced by a stationary platform having a smooth board floor. A man sat at the side of the machine, near the rear, and raked the bundles off sidewise with a hand rake. A boy drove the team and the man raked off the grain in sufficient quantities to make bundles. These were thrown by the rake a sufficient distance from the standing grain to allow the machine to proceed round and round the field, even if these bundles of grain, so raked off, were not yet bound into sheaves.

The Self Rake.—The next advance consisted in what is known as the "self rake." This machine had a series of slats or wings which did both the work of the reel in the earlier machine and also that of the[Pg 40] man who raked the wheat off the later machine. This saved the labor of one man.

The Harvester.—The next improvement in the evolution of the reaping machine—if indeed an improvement it could be called—was what is known as the "harvester." In this there was a canvas elevator upon which the grain was thrown by the reel, and which brought the grain up to the platform on which two men stood for the purpose of binding it. Each man took his share, binding alternate bundles and throwing them, when bound, down on the ground. Such work was certainly one of the repellent factors in driving men and boys from the country to the city.

The Wire Binder.—Another step in advance was the invention of the wire binder. Everything was now done by machinery: the cutting, the elevating, the binding, and even the carrying of the sheaves into piles or windrows. There was an attachment upon the machine by which the bundles were carried along and deposited in bunches to make the "shocking" easier.

The Twine Binder.—But the wire was found to be an obstruction both in threshing and in the use of straw for fodder; and, as necessity is the mother of invention, the so-called twine "knotter" soon came into existence and with it the full-fledged twine binder with all its varied improvements as we have it to-day.

Threshing Machine.—The development of the perfected threshing machine was very similar. Fifty years[Pg 41] ago, the flail was an implement of common use upon the barn floor. Then came the invention called the "cylinder"; this was systematically studded with "teeth" and these, in the rapid revolutions of the cylinder, passed between corresponding teeth systematically set in what is known as "concaves." This tooth arrangement in revolving cylinder and in concave was as epochal in the line of progress in threshing machines as the sickle, with its "sections" passing or being drawn through guards, was in reaping machines.

The First Machine.—The earliest of these threshing machines containing a cylinder was run by a treadmill on which a horse was used. It was literally a "one-horse" affair. Of course the first type of cylinder was small and simple, and the work as a rule was poorly done. The chaff and the straw came out together and men had to attend to each by hand. The wheat was poorly cleaned and had to be run through a fanning-mill several times.

Improvements.—Then came some improvements and enlargements in the cylinder, and also the application of horse power by means of what was known as "tumbling rods" and a gearing attached to the cylinder. All this at first was on rather a small scale, only two, three, or four horses being used. But improvements and enlargements came step by step, until the ten and twelve horse power machine was achieved, resulting in the large separator that would thresh out several hundred bushels of wheat in a day. The[Pg 42] separator had also attached to it what was called the "straw carrier," which conveyed both the straw and the chaff to quite a distance from the machine. But even then most of the work around the machine was done by hand. The straw pile required the attention of three or four men; or if the straw were "bucked," as they said, it required a man with a horse or team hitched to a long pole. In this latter case the straw was spread in various parts of the field and finally burned.

The Steam Engine.—Then came the portable steam engine for threshing purposes. At first, however, this had to be drawn from place to place by teams. The power was applied to the separator by a long belt. Following this, came the devices for cutting the bands, the self-feeder, and finally the straw blower, as it is called, consisting of a long tube through which the straw is blown by the powerful separator fanning-mill. This blower can be moved in different directions, and consequently it saves the labor of as many men as were formerly required to handle the straw and chaff. About the same time, also, the device for weighing and measuring the grain was perfected. The "traction" engine has now replaced the one which had to be drawn by teams, and this not only propels itself but also draws the separator and other loads after it from place to place. In all this progress the machinery has constantly become more and more perfect and the cylinder and capacity of the machine greater and greater.[Pg 43] Not many years ago, six hundred bushels in a day was considered a big record in the threshing of wheat. Now the large machines separate, or thresh out, between three and four thousand bushels in one day. Such has been the development in reaping machines from the sickle to the self-binder, and in threshing machines from the flail to the modern marvel just described.

Improvement in Ocean Travel.—A similar story may be told in regard to ocean traffic and ocean travel. Our ancestors came from foreign lands on sailing ships that required from three weeks to several months to cross the Atlantic. I am acquainted with a German immigrant who, many years ago, left a seaport town of Germany on January 1st and landed at Castle Garden in New York City on the 4th of July. The inconvenience of travel under such circumstances was equal to the slowness of the journey. In those days leaving home in the old country meant never again seeing one's relatives and friends. If such conditions are compared with those of to-day we can readily realize the vast progress that has been made. To-day the great ocean liners cross the Atlantic in a little more than five days. These magnificent "ocean greyhounds" are fitted out with all modern conveniences and improvements, so that one is as comfortable in them and as safe as he is in one of the best hotels of the large cities.

From Hand-spinning to Factory.—Weaving in former[Pg 44] times was done entirely by hand. Fifty years ago private weavers were found in almost every community. Wool was raised, carded, spun, and woven, and the garments were all made, practically, within the household. All that is now past. In the great manufacturing establishments one man at a lever does the work of 250 or 500 people. This great industrial advancement has taken place within the memory of people now living. And similar progress has been made in almost every other line of human endeavor.

The Cost.—Very few people realize what it has cost the human race to pass from one condition to the other in these various lines. Hundreds and thousands of men have worked and died in the struggle and in the process of bringing about improvements. Every calamity due to inadequate machines or to poor methods has had its influence toward causing further advancements in inventions for the benefit of mankind.

Progress in Higher Education.—Let us now turn our attention to the progress that has been made in the field of academic education. It is true that many of the great universities were established centuries ago. These were at first endowed church institutions or theological seminaries; but the great state universities of this country are creations of the progressive period under consideration. General taxation for higher education is comparatively a modern practice. The University of Michigan was one of the first state universities established. Since then nearly[Pg 45] every commonwealth, whether it has come into the Union since that time or whether it is one of the older states, has established a university. There has been a great development of higher education by the states. No institutions of the country have grown more rapidly within the last thirty or forty years than the state universities. They have established departments of every kind. Besides the college of liberal arts there are in most of them colleges or schools of law, medicine, engineering in its several lines, education, pharmacy, dentistry, commerce, industrial arts, and fine arts. The state university is abroad in the land; it has, as a rule, an extension department by which it impresses itself upon the people of the state, outside its walls. The principle of higher education by taxation of all the people is no longer questioned; it is no longer an experiment. The state university is relied upon to furnish the country with the leaders of the future—and leaders will always be in demand, for they are always sorely needed.

Progress in Normal Schools.—While the state universities have been enjoying this marvelous development, nearly every state has been establishing normal schools for the professional preparation of teachers. The normal school as an institution is also modern. As an institution established and supported by state taxation it is, as a rule, more recent than the universities. Forty years ago many good people regarded the normal school idea as visionary and its realization[Pg 46] as a doubtful experiment. Indeed in one western state, as late as the eighties, its legislature debated the abolition of its normal schools on the ground that they were not fulfilling or accomplishing any useful mission. To-day, however, no such charge of inefficiency can be made. The normal schools, like the universities, have proved their right to exist. They have been weighed in the balance and have not been found wanting. It is now generally recognized that those who would teach should make some preparation for that high calling; and so the normal schools in every state have demonstrated their "right of domicile" in the educational system. It is now generally recognized that teaching, both as a science and as an art, is highly complicated, and that, if it is to be a profession, there must be special preparation for it. Consequently the normal schools of the country have had a wonderful and rapid development from the experimental stage to that in which they have well-nigh realized their ideals. School boards everywhere look to the normal schools for their supply of elementary teachers.

Progress in Agricultural Colleges.—Similar statements may be made concerning the agricultural colleges of the country. They are modern creations in the United States; and with the aid of both the state and the national government they have come to be vast institutions, devoting themselves to the teaching and the spreading of scientific farming among the people. Here there is a vast work to be done. On[Pg 47] account of the trend of population toward the cities, and on account of the vast tracts of country land lying idle, scientific agriculture should be brought in to aid in production and thus to keep down the cost of living. The agricultural colleges of the country have a large part to play in the solution of the problems of rural life.

Progress in the High Schools.—A similar development characterizes the high schools of the country. Education has extended downward from above. Universities everywhere have come into existence before the establishment of secondary schools. Not only are the universities, the normal schools, and the agricultural colleges of recent origin, but the high schools also are modern institutions, at least in their present systematized form. The high schools of the cities constitute to-day one of the most efficient forms of school organization. At the present time the better high schools of the cities are veritable colleges—in fact their curricula are as extensive as were those of the colleges of sixty years ago. Vast numbers attend them; their faculties are composed of college graduates or better; they have, as a rule, various departments, such as manual training, domestic science, agriculture, commercial subjects, normal courses, etc. In addition to the traditional curricula, the high schools, like the universities, normal schools, and agricultural colleges, have kept pace, in large measure, with the material progress described in the first part of this chapter.

How Is the Rural School?—We have described the[Pg 48] progress that has been made in various fields of the industrial world and also in several kinds of educational institutions. At this point the question may, with propriety, be asked whether the rural schools have generally kept pace in their progress with the other and higher institutions which we have mentioned. We believe that they have not. The rural schools have too often been the last to attract public interest and to receive the attention which their importance deserves.

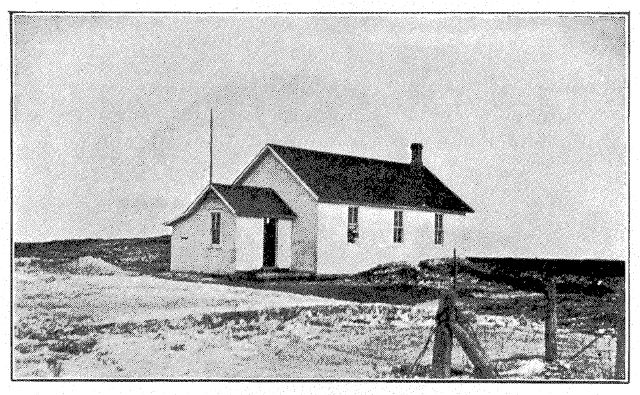

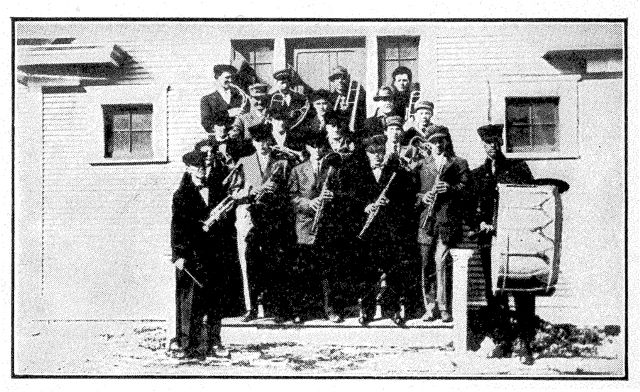

A neglected school in unattractive surroundings

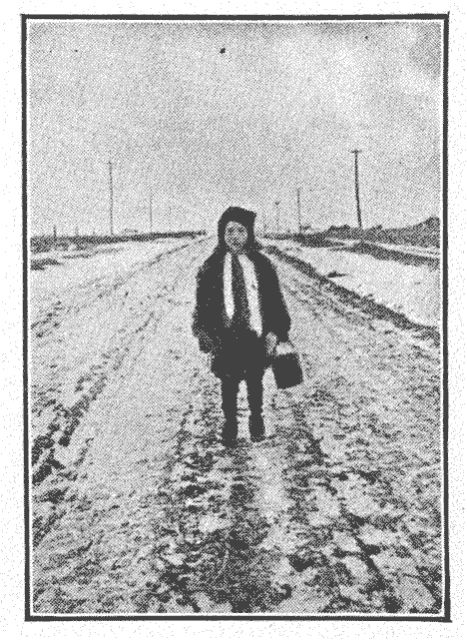

A lonely road to school. No conveyances provided

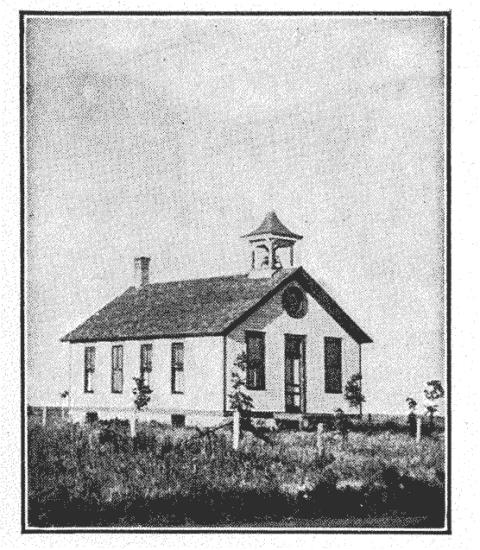

A better type of building with some attempt at improvements

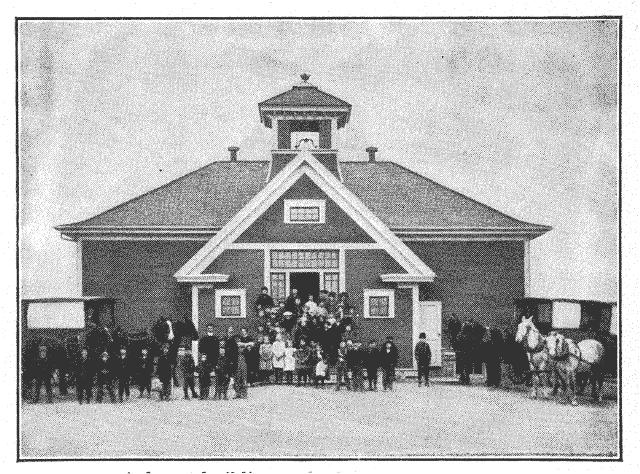

THE ONE-ROOM SCHOOL

Rural Schools the Same Everywhere.—The one-room country school of to-day is much the same the whole country over. Such schools are no better in Michigan, Wisconsin, or Minnesota than they are in the Dakotas, Montana, or Idaho. They are no better in Ohio or New York than they are in Minnesota or Wisconsin, and no better in the New England states than in New York and Ohio. There is a wonderful similarity in these schools in all the states.

Nevertheless, it may be maintained with some plausibility that the rural schools of the West are superior to those farther east. The East is conservative and slow to change. The West has fewer traditions to break. Many strong personalities of initiative and push have come out of the East and taken up their abode in the West. Young men continue to follow Horace Greeley's advice. Sometimes these young men file upon lands and teach the neighboring school; and while this may not be the highest professional aim and attitude, it remains true nevertheless that such teachers are often earnest, strong, and educated persons.[Pg 50]

Not long ago I had occasion to visit a teacher's institute in a northwestern state, in which there were enrolled 350 teachers. Some of these were college graduates and many of them were normal school graduates from various states. One had only to conduct a round table in order to experience a very spirited reaction. Colonel Homer B. Sprague, who was once president of the University of North Dakota, used to say that it always wrenched him to kick at nothing. There would be no danger, in such a body of teachers as I have referred to, of wrenching oneself. I have had occasion many times every year to meet these western teachers in local associations, in teachers' institutes, and in state conventions; and from my observations and experience I can truthfully state that they are fully as responsive and as progressive as the teachers in other parts of the country.

Rural Schools no Better than Formerly.—Notwithstanding all this, it is probably true that the rural schools of to-day are, on the whole, but little better than those of twenty years ago. About that time I served four years as county superintendent of schools in a western state. As I recall the condition of the schools of that day I feel sure that there has been but little real progress. Indeed, for reasons which will be stated later on, it can be safely asserted that in some parts of the country there has been a deterioration.

About thirty years ago I had the experience of teaching rural schools for several terms. Being acquainted[Pg 51] with my coworkers, I met them frequently in teachers' gatherings and in conventions of various kinds. If my memory is to be trusted I can again affirm that the teachers of those days do not compare unfavorably with the rural school teachers of the present time. And if the teacher is the measure of the school, the same may be said of the schools.

Nor is this all. About forty years ago I was attending a rural school myself. I received all of my elementary education in such schools and I am convinced that many of my teachers were stronger personalities than the teachers of to-day.

Some Improvement.—It is not intended here to assert or to convey the impression that there has been no progress in any direction in the rural schools. It is the personnel of the country school—the strength and power of initiative in the teachers of that day—that is here referred to. Although there has been some progress in many lines it has not been in the direction of stronger teachers. The textbooks in use to-day in various branches are decidedly superior to those used in former days, although some of these older books were by no means without their points of strength and excellence. Indeed, I sometimes think that textbooks are often rendered less efficient by being refined upon in a variety of ways to conform to the popular pedagogical ideas of the day.

It is no doubt true also that there has been, in the last thirty or forty years, much discussion along the[Pg 52] lines of psychology and pedagogy and the methods of teaching the various branches. The professional spirit has been in the air, and there has been much writing and much talking on the science and art of teaching. But it must be confessed that, while this is desirable and in fact indispensable, much of it may be little more than a mere whitewash; much of it is simply parrot-like imitation; much of it is only "words, words, words." Far be it from me to underestimate the value of this professional and pedagogical phase of the teacher's equipment. Nevertheless, when all is said and duly considered, it is personality that is the greatest factor in the teacher. A good, sound knowledge of the subjects to be taught comes next; and last, though probably not least, should come the professional preparation and training. Without the first two requisites, however, this last is worth little. It is a lamentable fact that, in almost every section of our country, there are persons engaged in teaching rural schools, who are not only deficient in personal power but whose academic education is not such as to afford an adequate foundation for professional training.

Strong Personalities in the Older Schools.—As an example of strong personalities I remember one teacher who in middle life was recognized as a leader in his community; another one, after serving an apprenticeship in the country schools, became a prominent and successful physician; a third became a leading architect; a fourth, a lawyer; a fifth went west and[Pg 53] became county judge in the state of his adoption; a sixth entered West Point Military Academy and rose rapidly in the United States army. These instances are given to show that many of the old-time country teachers were men of force and initiative. They became to their pupils ideals of manhood worthy to be patterned after. These all taught in one neighborhood, but similar strong characters were no doubt engaged in the schools of surrounding neighborhoods. What rural school of to-day in any state can boast of the uplifting presence of so many men teaching in one decade?

A. V. Storm, of the Minnesota Agricultural College, says:

"But we lack one thing nowadays that these old schools possessed. Twenty or thirty years ago the country schools were taught for the most part by men. Such men as Shaw and Dolliver, and a great many other leading men of to-day, were at one time country school teachers. They exercised a great influence upon the pupils. They were the angels who put the coals of fire upon the lips of the young men, giving them the ambition that made for future greatness. The country schools now are not so good as they were twenty years ago. The chief reason is that their teachers are not so capable."

More Men Needed.—To secure the best results, there should be fully as many men as women teaching in the rural schools. One hundred years ago both city and country schools were taught by men alone. Now[Pg 54] the rural schools and most of the city schools are taught by women alone. There is probably as much reason against all teachers being women as there is against all teachers being men.

Low Standard Now.—Thirty or forty years ago about half of the teachers were men and half women, both sexes representing the strong and the weak. Very many of the schools of to-day are under the charge of young girls from eighteen to twenty years of age who have had little more than a common elementary education. Some have just finished the eighth grade and have had a smattering of pedagogy or what is sometimes called "the theory and practice of teaching." This they could have secured in a six weeks' summer school, while reviewing the so-called "common branches." These teachers are holders merely of a second grade elementary, or county, certificate, which requires very little education. Almost any person who has taken the required course in reading, writing, spelling, arithmetic, grammar, geography, history, and hygiene of the elementary school can pass the usual examination and obtain a certificate to teach. In some states the matter is made still easier by the issuing of third grade county certificates, and even, in some cases, by the giving of special permits. Indeed, the standards are usually so low that the supply of teachers is far beyond the demand.

The Survival of the Unfittest.—Such is the standard which prevails extensively throughout the country in[Pg 55] respect to the qualifications of rural school teachers. As inferior goods sometimes drive out the better in the markets, so poor teachers holding the lowest grade of certificate will sometimes drive out the better, for they are ready to teach for "less than anybody else." The men and women of strength and initiative are constantly tempted to go out of the calling into other lines of work where progress is more pronounced and where salaries or wages are higher; and so the doors of the teachers' calling swing outward. The good teachers will desert us, or refuse to come, and the rural schools will be left with what might be called the survival of the unfittest.

Short Terms.—Add to the foregoing considerations the short terms of service which prevail in rural schools and we have indeed a pitiable condition. The average yearly duration of such schools in most states is about seven months—sometimes less. This leaves about five months of vacation, or of time between terms, when much that has been learned is forgotten. Under such conditions how is it possible to give the children of these communities an education which is at all comparable to that afforded by the city?

Poor Supervision.—Then, again, there is often little supervision of country schools. When a county superintendent has under his inspection from fifty to two hundred schools, it is utterly impossible for him to give to each the desired number of visits or to supervise and superintend the work of those schools in a manner[Pg 56] that can be called adequate in any true sense. Sometimes he can visit each school only once a year, or twice at most, and, even then, there may be two different teachers in the same school during the year; so that he sees each of his teachers at work probably only once. What can a supervising officer do for a school or for a teacher under such circumstances? Practically nothing. The county superintendent is usually elected to office by the people and frequently on a partisan ticket. This method of choosing naturally tends to make him give more attention to politics than he otherwise would think of giving. So the supervision or superintendency of country schools is too often slighted or neglected—and who is to blame? Of course there are many exceptional cases, but the exceptions only prove the rule.

No Decided Movement.—The whole movement of the rural school, whether it has been backward or forward, has been too frequently without definite or pronounced direction. It has moved along the line of least resistance, sometimes this way, sometimes that, in some places forward, in other places backward. Time, circumstances, and chance determine the work. School problems have been settled by convenience and circumstances. The whole situation has been one of laissez faire. It is only within the past few years that people have become awakened to the situation. They are beginning to be impressed with the progress that is being made in all other lines, not only outside of the[Pg 57] schools but also in the fields of higher and secondary education. The rural school interests have at last begun to ask, "Where do we come in?"

Elementary Teaching Not a Profession.—There has been as yet no real profession of teaching in the rural or elementary field. In about one third of the schools there is a new teacher every year; so that every three years the teaching force in any given county is practically renewed. A profession cannot be acquired in a day, or even in twelve months. The work to be done is regarded as an important public work, and the public is concerned in its own protection. Hence in every true profession there is a somewhat lengthy period of preparation and a standard of acquirements which must be attained. In other words, a true profession is a closed calling which it is impossible for everyone to join, and which only those can enter who have passed through a severe preparation and have successfully met the required standard. School teaching in the country is too frequently not a profession. It can be entered too easily; the required period of preparation is so short and the standard is placed so low that young and poorly prepared persons enter too easily.