Title: The Spanish Jade

Author: Maurice Hewlett

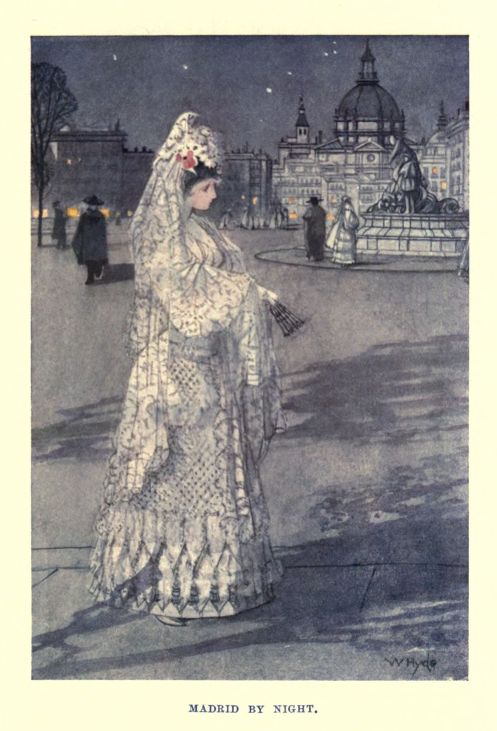

Illustrator: William Henry Hyde

Release date: July 29, 2009 [eBook #29545]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| INTRODUCTION | |

| I. | THE PLEASANT ERRAND |

| II. | THE TRAVELLER AT LARGE |

| III. | DIVERSIONS OF TRAVEL |

| IV. | TWO ON HORSEBACK |

| V. | THE AMBIGUOUS THIRD |

| VI. | A SPANISH CHAPTER |

| VII. | THE SLEEPER AWAKENED |

| VIII. | REFLECTIONS OF AN ENGLISHMAN |

| IX. | A VISIT TO THE JEWELLER'S |

| X. | FURTHER EPISODES IN THE LIFE OF DON LUIS RAMONEZ |

| XI. | GIL PEREZ DE SEGOVIA |

| XII. | A GLIMPSE OF MANUELA |

| XIII. | CHIVALRY OF GIL PEREZ |

| XIV. | TRIAL BY QUESTION |

| XV. | NEMESIS—DON LUIS |

| XVI. | THE HERALD |

| XVII. | LA RACOGIDA |

| XVIII. | THE NOVIO |

| XIX. | THE WAR OPENS |

| XX. | MEETING BY MOONLIGHT |

Cada puta hile (Let every jade go spin).—SANCHO PANZA.

Almost alone in Europe stands Spain, the country of things as they are. The Spaniard weaves no glamour about facts, apologises for nothing, extenuates nothing. Lo que ha de ser no puede faltar! If you must have an explanation, here it is. Chew it, Englishman, and be content; you will get no other. One result of this is that Circumstance, left naked, is to be seen more often a strong than a pretty thing; and another that the Englishman, inveterately a draper, is often horrified and occasionally heart-broken. The Spaniard may regret, but cannot mend the organ. His own will never suffer the same fate. Chercher le midi à quatorze heures is no foible of his.

The state of things cannot last; for the sentimental pour into the country now, and insist that the natives shall become as self-conscious as themselves. The Sud-Express brings them from England and Germany, vast ships convey them from New York. Then there are the newspapers, eager as ever to make bricks without straw. Against Teutonic travellers, and journalists, no idiosyncrasy can stand out. The country will run to pulp, as a pear, bitten without by wasps and within by a maggot, will get sleepy and drop. But that end is not yet, the Lord be praised, and will not be in your time or mine. The tale I have to tell—an old one, as we reckon news now—might have happened yesterday; for that was when I was last in Spain, and satisfied myself that all the concomitants were still in being. I can assure you that many a Don Luis yet, bitterly poor and bitterly proud, starves and shivers, and hugs up his bones in his capa between the Bidassoa and the Manzanares; many a wild-hearted, unlettered Manuela applies the inexorable law of the land to her own detriment, and, with a sob in the breath, sits down to her spinning again, her mouldy crust and cup of cold water, or worse fare than that. Joy is not for the poor, she says—and then, with a shrug, Lo que ha de ser...!

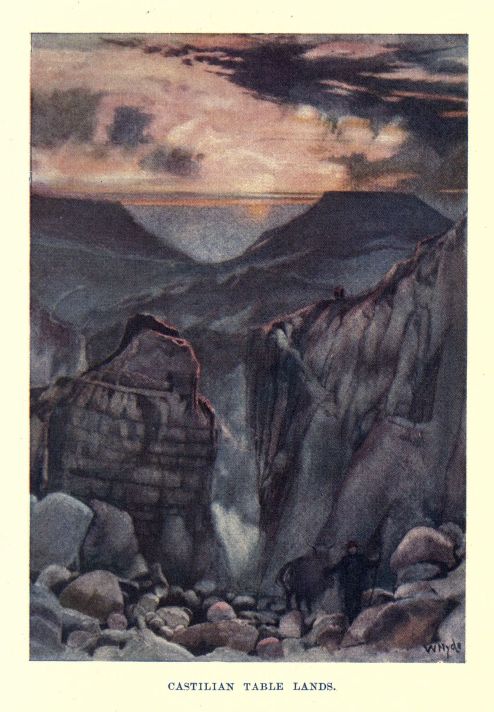

But, as a matter of fact, it belongs to George Borrow's day, this tale, when gentlemen rode a-horseback between town and town, and followed the river-bed rather than the road. A stranger then, in the plains of Castile, was either a fool who knew not when he was well off, or an unfortunate, whose misery at home forced him afield. There was no genus Tourist; the traveller was conspicuous and could be traced from Spain to Spain. When you get on you'll see; that is how Tormillo weaselled out Mr. Manvers, by the smell of his blood. A great, roomy, haggard country, half desert waste and half bare rock, was the Spain of 1860, immemorially old, immutably the same, splendidly frank, acquainted with grief and sin, shameless and free; like some brown gipsy wench of the wayside, with throat and half her bosom bare, who would laugh and show her teeth, and be free with her jest; but if you touched her honour, ignorant that she had one, would stab you without ruth, and go her free way, leaving you carrion in the ditch. Such was the Spain which Mr. Manvers visited some fifty years ago.

Into the plain beyond Burgos, through the sunless glare of before-dawn; upon a soft-padding ass that cast no shadow and made no sound; well upon the stern of that ass, and with two bare heels to kick him; alone in the immensity of Castile, and as happy as a king may be, rode a young man on a May morning, singing to himself a wailing, winding chant in the minor which, as it had no end, may well have had no beginning. He only paused in it to look before him between his donkey's ears; and then—"Arré, burra, hijo de perra!"—he would drive his heels into the animal's rump. In a few minutes the song went spearing aloft again .... "En batalla-a-a temero-o-sa-a....!"

I say that he was young; he was very young, and looked very delicate, with his transparent, alabaster skin, lustrous grey eyes and pale, thin lips. He had a sagging straw hat upon his round and shapely head, a shirt—and a dirty shirt—open to the waist. His faja was a broad band of scarlet cloth wound half a dozen times about his middle, and supported a murderous long knife. For the rest, cotton drawers, bare legs, and feet as brown as walnuts. All of him that was not whitey-brown cotton or red cloth was the colour of the country; but his cropped head was black, and his eyes were very light grey, keen, restless and bold. He was sharp-featured, careless and impudent; but when he smiled you might think him bewitching. His name he would give you as Estéban Vincaz—which it was not; his affair was pressing, pleasant and pious. Of that he had no doubt at all. He was intending the murder of a young woman.

His eyes, as he sang, roamed the sun-struck land, and saw everything as it should be. Life was a grim business for man and beast and herb of the field, no better for one than for the others. The winter corn in patches struggled sparsely through the clods; darnels, tares, deadnettle and couch, the vetches of last year and the thistles of next, contended with it, not in vain. The olives were not yet in flower, but the plums and sloes were powdered with white; all was in order.

When a clump of smoky-blue iris caught his downward looks, he slipped off his ass and snatched a handful for his hat. "The Sword-flower," he called it, and accepting the omen with a chuckle, jumped into his seat again and kicked the beast with his naked heels into the shamble that does duty for a pace. As he decorated his hat-string he resumed his song:—

"En batalla temerosa

Andaba el Cid castellano

Con Búcar, ese rey moro,

Que contra el Cid ha llegado

A le ganar a Valencia..."

He hung upon the pounding assonances, and his heart thumped in accord, as if his present adventure had been that crowning one of the hero's.

Accept him for what he was, the graceless son of his parents—horse-thief, sheep-thief, contrabandist, bully, trader of women—he had the look of a seraph when he sang, the complacency of an angel of the Weighing of Souls. And why not? He had no doubts; he could justify every hour of his life. If money failed him, wits did not; he had the manners of a gentleman—and a gentleman he actually was, hidalgo by birth—and the morals of a hyaena, that is to say, none at all. I doubt if he had anything worth having except the grand air; the rest had been discarded as of no account.

Schooling had been his, he had let it slip; if his gentlehood had been negotiable he had carded it away. Nowadays he knew only elementary things—hunger, thirst, fatigue, desire, hatred, fear. What he craved, that he took, if he could. He feared the dark, and God in the Sacrament. He pitied nothing, regretted nothing; for to pity a thing you must respect it, and to respect you must fear; and as for regret, when it came to feeling the loss of a thing it came naturally also to hating the cause of its loss; and so the greater lust swallowed up the less.

He had felt regret when Manuela ran away; it had hurt him, and he hated her for it. That was why he intended at all cost to find her again, and to kill her; because she had been his amiga, and had left him. Three weeks ago, it had been, at the fair of Pobledo. The fair had been spoiled for him, he had earned nothing, and lost much; esteem, to wit, his own esteem, mortally wounded by the loss of Manuela, whose beauty had been a mark, and its possession an asset; and time—valuable time—lost in finding out where she had gone.

Friends of his had helped him; he had hailed every arriero on the road, from Pamplona to La Coruña; and when he had what he wanted he had only delayed for one day, to get his knife ground. He knew exactly where she was, at what hour he should find her, and with whom. His tongue itched and brought water into his mouth when he pictured the meeting. He pictured it now, as he jogged and sang and looked contentedly at the endless plain.

Presently he came within sight, and, since he made no effort to avoid it, presently again into the street of a mud-built village. Few people were astir. A man slept in an angle of a wall, flies about his head; a dog in an entry scratched himself with ecstasy; a woman at a doorway was combing her child's hair, and looked up to watch him coming.

Entering in his easy way, he looked to the east to judge of the light. Sunrise was nearly an hour away; he could afford to obey the summons of the cracked bell, filling the place with its wrangling, with the creaking of its wheel. He hobbled his beast in the little plaza, and followed some straying women into church.

Immediately confronting him at the door was a hideous idol. A huge and brown, wooden Christ, with black horse-hair tresses, staring white eyeballs, staring red wounds, towered before him, hanging from a cross. Estéban knelt to it on one knee, and, remembering his hat, doffed it sideways over his ear. He said his two Paternosters, and then performed one odd ceremony more. Several people saw him do it, but no one was surprised. He took the long knife from his faja, running his finger lightly along the edge, laid it flat before the Cross, and looking up at the tormented God, said him another Pater. That done, he went into the church, and knelt upon the floor in company with kerchiefed women, children, a dog or two, and some beggars of incredible age and infirmities beyond description, and rose to one knee, fell to both, covered his eyes, watched the celebrant, or the youngest of the women, just as the server's little bell bade him. Simple ceremonies, done by rote and common to Latin Europe; certainly not learned of the Moors.

Mass over, our young avenger prepared to resume his journey by breaking his fast. A hunch of bread and a few raisins sufficed him, and he ate these sitting on the steps of the church, watching the women as they loitered on their way home. Estéban had a keen eye for women; pence only, I mean the lack of them, prevented him from being a collector. But the eye is free; he viewed them all from the standpoint of the cabinet. One he approved. She carried herself well, had fine ankles, and wore a flower in her hair like an Andalusian. Now, it was one of his many grudges against fate that he had never been in Andalusia and seen the women there. For certain, they were handsome; a Sevillana, for instance! Would they wear flowers in their hair—over the ear—unless they dared be looked at? Manuela was of Valencia, more than half gitana: a wonderfully supple girl. When she danced the jota it was like nothing so much as a snake in an agony. Her hair was tawny yellow, and very long. She wore no flower in it, but bound a red handkerchief in and out of the plaits. She was vain of her hair—heart of God, how he hated her!

Then the priest came out of church, fat, dewlapped, greasy, very short of breath, but benevolent. "Good-day, good-day to you," he said. "You are a stranger. From the North?"

"My reverence, from Burgos."

"Ha, from Burgos this morning! A fine city, a great city."

"Yes, sir, it's true. It is where they buried our lord the Campeador."

"So they say. You are lettered! And early afoot."

"Yes, sir. I am called to be early. I still go South."

"Seeking work, no doubt. You are honest, I hope?"

"Yes, sir, a very honest Christian. But I seek no work. I find it."

"You are lucky," said the priest, and took snuff. "And where is your work? In Valladolid, perhaps?"

Estéban blinked hard at that last question. "No, sir," he said. "Not there." Do what he might he could not repress the bitter gleam in his eyes.

The old priest paused, his fingers once more in the snuff-box. "There again you have a great city. Ah, and there was a time when Valladolid was one of the greatest in Castile. The capital of a kingdom! Chosen seat of a king! Pattern of the true Faith!" His eyelids narrowed quickly. "You do not know it?"

"No, sir," said Estéban gently. "I have never been there."

The priest shrugged. "Vaya! it is no affair of mine," he said. Then he waved his hand, wagging it about like a fan. "Go your ways," he added, "with God."

"Always at the feet of your reverence," said Estéban, and watched him depart. He stared after him, and looked sick.

Altogether he delayed for an hour and a quarter in this village: a material time. The sun was up as he left it—a burning globe, just above the limits of the plain.

Ahead of Estéban some five or six hours, or, rather converging upon a common centre so far removed from him, was one Osmund Manvers, a young English gentleman of easy fortune, independent habits and analytical disposition; also riding, also singing to himself, equally early afoot, but in very different circumstances. He bestrode a horse tolerably sound, had a haversack before him reasonably stored. He had a clean shirt on him, and another embaled, a brace of pistols, a New Testament and a "Don Quixote"; he wore brown knee-boots, a tweed jacket, white duck breeches, and a straw hat as little picturesque as it was comfortable or convenient. Neither revenge nor enemy lay ahead, of him; he travelled for his pleasure, and so pleasantly that even Time was his friend. Health was the salt of his daily fare, and curiosity gave him appetite for every minute of the day.

He would have looked incongruous in the elfin landscape—in that empty plain, under that ringing sky—if he had not appeared to be as extremely at home in it as young Estéban himself; but there was this farther difference to be noted, that whereas Estéban seemed to belong to the land, the land seemed to belong to Mr. Manvers—the land of the Spains and all those vast distances of it, the enormous space of ground, the dim blue mountains at the edge, the great arch of sky over all. He might have been a young squire at home, overlooking his farms, one eye for the tillage or the upkeep of fence and hedge, another for a covey, or a hare in a farrow. He was as serene as Estéban and as contented; but his comfort lay in easy possession, not in being easily possessed. Occasionally he whistled as he rode, but, like Estéban, broke now and again into a singing voice, more cheerful, I think, than melodious.

"If she be not fair for me,

What care I how fair she be?"

An old song. But Henry Chorley made a tone for it the summer before Mr. Manvers left England, and it had caught his fancy, both the air and the sentiment. They had come aptly to suit his scoffing mood, and to help him salve the wound which a Miss Eleanor Vernon had dealt his heart—a Miss Eleanor Vernon with her clear disdainful eyes. She had given him his first acquaintance with the hot-and-cold disease.

"If she be not fair for me!" Well, she was not to be that. Let her go spin then, and—"What care I how fair she be?" He had discarded her with the Dover cliffs, and resumed possession of himself and his seeing eye. By this time a course of desultory journeying through Brittany and the West of France, a winter in Paris, a packet from Bordeaux to Santander had cured him of his hurt. The song came unsought to his lips, but had no wounded heart to salve.

Mr. Manvers was a pleasant-looking young man, sanguine in hue, grey in the eye, with a twisted sort of smile by no means unattractive. His features were irregular, but he looked wholesome; his humour was fitful, sometimes easy, sometimes unaccountably stiff. They called him a Character at home, meaning that he was liable to freakish asides from the common rotted road, and could not be counted on. It was true. He, for his part, called himself an observer of Manvers, which implied that he had rather watch than take a side; but he was both hot-tempered and quick-tempered, and might well find himself in the middle of things before he knew it. His crooked smile, however, seldom deserted him, seldom was exchanged for a crooked scowl; and the light beard which he had allowed himself in the solitudes of Paris led one to imagine his jaw less square than it really was.

I suppose him to have been five foot ten in his boots, and strong to match. He had a comfortable income, derived from land in Somersetshire, upon which his mother, a widow lady, and his two unmarried sisters lived, and attended archery meetings in company of the curate. The disdain of Miss Eleanor Vernon had cured him of a taste for such simple joys, and now that, by travel, he had cured himself of Miss Eleanor, he was travelling on for his pleasure, or, as he told himself, to avoid the curate. Thus neatly he referred to his obligations to Church and State in Somersetshire.

By six o'clock on this fine May morning he had already ridden far—from Sahagun, indeed, where he had spent some idle days, lounging, and exchanging observations on the weather with the inhabitants. He had been popular, for he was perfectly simple, and without airs; never asked what he did not want to know, and never refused to answer what it was obviously desired he should. But man cannot live upon small talk; and as he had taken up his rest in Sahagun in a moment of impulse—when he saw that it possessed a church-dome covered with glazed green tiles—so now he left it.

"High Heaven!" he had cried, sitting up in bed, "what the deuce am I doing here? Nothing. Nothing on earth. Let's get out of it." So out he had got, and could not ask for breakfast at four in the morning.

He rode fast, desiring to make way before the heat began, and by six o'clock, with the sun above the horizon, was not sorry to see towers and pinnacles, or to hear across the emptiness the clangorous notes of a deep-toned bell. "The muezzin calls the faithful, but for me another summons must be sounded. That town will be Palencia. There I breakfast, by the grace of God. Coffee and eggs."

Palencia it was, a town of pretence, if such a word can be applied to anything Spanish, where things either are or are not, and there's an end. It was as drab as the landscape, as weatherworn and austere; but it had a squat officer sitting at the receipt of custom, which Sahagun had not, and a file of anxious peasants before him, bargaining for their chickens and hay.

Upon the horseman's approach the functionary raised himself, looking over the heads of the crowd as at a greater thing, saluted, and inquired for gate-dues with his patient eyes. "I have here," said Manvers, who loved to be didactic in a foreign language, "a shirt and a comb, the New Testament, the History of the Ingenious Gentleman, Don Quixote de la Mancha, and a toothbrush."

Much of this was Greek to the doganero, who, however, understood that the stranger was referring in tolerable Castilian to a provincial gentleman of degree. The name and Manvers' twisted smile together won him the entry. The officer just eased his peaked cap. "Go with God, sir," he directed.

"Assuredly," said Manvers, "but pray assist me to the inn."

The Providencia was named, indicated, and found. There was an elderly man in the yard of it, placidly plucking a live fowl, a barbarity with which our traveller had now ceased to quarrel.

"Leave your horrid task, my friend," he said. "Take my horse, and feed him."

The bird was released, and after shaking, by force of habit, what no longer, or only partially existed, rejoined its companions. They received it coldly, but it soon showed that it could pick as well as be picked.

"Now," said Manvers to the ostler, "give this horse half a feed of corn, then some water, then the other half feed; but give him nothing until you have cooled him down. Do these things, and I present you with one peseta. Omit any of them, and I give you nothing at all. Is that a bargain?"

The old man haled off the horse, muttering that it would be a bad bargain for his Grace, to which Manvers replied that we should see. Then he went into the Providencia for his coffee and eggs.

If Sahagun puts you out of conceit with Castile, you are not likely to be put in again by Palencia; for a second-rate town in this kingdom is like a piece of the plain enclosed by a wall, and only emphasises the desolation at the expense of the freedom; and as in a windy square all the city garbage is blown into corners, so the walled town seems to collect and set to festering all the disreputable creatures of the waste.

Mr. Manvers, his meal over, hankered after broad spaces again. He walked the arcaded streets and cursed the flies, he entered the Cathedral and was driven out by the beggars. He leaned over the bridge and watched the green river, and that set him longing for a swim. If his maps told him the truth, some few leagues on the road to Valladolid should discover him a fine wood, the wood of La Huerca, beyond which, skirting it, in fact, should be the Pisuerga. Here he could bathe, loiter away the noon, and take his merienda, which should be the best Palencia could supply.

"Muera Marta,

Y muera harta,"

"Let Martha die, but not on an empty stomach," he said to himself. He knew his Don Quixote better than most Spaniards.

He furnished his haversack, then, with bread, ham, sausages, wine and oranges, ordered out his horse, satisfied himself that the ostler had earned his fee, and departed at an ambling pace to seek his amusements. But, though he knew it not, the finger of Fate was upon him, and he was enjoying the last of that perfect leisure without which travel, love-making, the arts and sciences, gardening, or the rearing of a family, are but weariness and disgust. Just outside the gate of Palencia he had an adventure which occupied him until the end of this tale, and, indeed, some way beyond it.

The Puerta de Valladolid is really no gate at all, but a gateway. What walls it may once have pierced have fallen away from it in their fight with time, and now buttresses and rubbish-heaps, a moat of blurred outline and much filth, alone testify to former pretensions. Beyond was to be found a sandy waste, miscalled an alameda, a littered place of brown grass, dust and loose stones, fringed with parched acacias, and diversified by hillocks, upon which, in former days of strife, standards may have been placed, mangonels planted, perhaps Napoleonic cannon.

It was upon one of these mounds, which was shaded by a tree, that Manvers observed, and paused in the gateway to observe, the doings of a group of persons, some seven boys and lads, and a girl. A kind of uncouth courtship seemed to be in progress, or (as he put it) the holding of a rude Court. He thought to see a Circe of picaresque Spain with her swinish rout about her. To drop metaphor, the young woman sat upon the hillock, with the half dozen tatterdemalions round her in various stages of amorous enchantment.

He set the girl down for a gipsy, for he knew enough of the country to be sure that no marriageable maiden of worth could be courted in this fashion. Or if not a gipsy then a thing of nought, to be pitied if the truth were known, at any rate to be skirted. Her hair, which seemed to be of a dusty gold tinge, was knotted up in a red handkerchief; her gown was of blue faded to green, her feet were bare. If a gipsy, she was to be trusted to take care of herself; if but a sunburnt vagrant she could be let to shift; and yet he watched her curiously, while she sat as impassive as a young Sphinx, and wondered to himself why he did it.

Suppose her of that sort you may see any day at a fair, jigging outside a booth in red bodice and spangles, a waif, a little who-knows-who, suppose her pretty to death—what is she even then but an iridescent bubble, as one might say, thrown up by some standing pool of vice, as filmy, very nearly as fleeting, and quite as poisonous? It struck him as he watched—not the girl in particular, but a whole genus centred in her—as really extraordinary, as an obliquity of Providence, that such ephemerids must abound, predestined to misery; must come and sin, and wail and go, with souls inside them to be saved, which nobody could save, and bodies fair enough to be loved, which nobody could stoop to love. Had the scheme of our Redemption scope enough for this—for this trifle, along with Santa Teresa, and the Queen of Sheba, and Isabella the Catholic? He perceived himself slipping into the sententious on slight pretence—but presently found himself engaged.

Hatless, shoeless, and coatless were the oafs who surrounded the object of his speculations, some lying flat, with elbows forward and chins to fist; some creeping and scrambling about her to get her notice, or fire her into a rage; some squatting at an easy distance with ribaldries to exchange. But there was one, sitting a little above her on the mound, who seemed to consider himself, in a sort, her proprietor. He was master of the pack, warily on the watch, able by position and strength to prevent what he might at any moment choose to think on infringement of his rights. A sullen, grudging, silent, and jealous dog, Manvers saw him, and asked himself how long she would stand it. At present she seemed unaware of her surroundings.

He saw that she sat broodingly, as if ruminating on more serious things, such as famine or thirst, her elbows on her knees and her face in her two hands. That was the true gipsy attitude, he knew, all the world over. But so intent she was, that she was careless of her person, careless that her bodice was open at the neck and that more people than Manvers were aware of it. A flower was in her mouth, or he thought so, judging from the blot of scarlet thereabouts; her face was set fixedly towards the town—too fixedly that he might care, since she cared so little, whether she saw him there or not. And after all, not she, but the manners of the game centred about her, was what mattered.

Manners, indeed! The fastidious in our young man was all on edge; he became a critic of Spain. Where in England, France, or Italy could you have witnessed such a scene as this? Or what people but the Spaniards among the children of Noah know themselves so certainly lords of the earth that they can treat women, mules, prisoners, Jews, and bulls according to the caprices of appetite? That an Italian should make public display of his property in a woman, or his scorn of her, was a thing unthinkable; yet, if you came to consider it, so it was that a Spaniard should not. Set aside, said he to himself, the grand air, and what has the Spaniard which the brutes have not?

Hotly questioning the attendant heavens, Manvers saw just such an act of mastery, when the lumpish fellow above the girl put his hand upon her, and kept it there, and the others thereupon drew back and ceased their tricks, as if admitting possession had and seisin taken, as the lawyers call it. To Manvers a hateful thing. He felt his blood surge in his neck. "Damn him! I've a mind——! And they pray to a woman!"

But the girl did nothing—neither moved, nor seemed to be aware. Then the drama suddenly quickened, the actors serried, and the acts, down to the climax, followed fast.

Emboldened by her passivity, the oaf advanced by inches, visibly. He looked knowingly about him, collecting approval from his followers, he whispered in her ear, hummed gallant airs, regaled the company with snatches of salt song. Fixed as the Sphinx and unfathomable, she sat on broodingly until, piqued by her indifference, maybe, or swayed by some wave of desire, he caught her round the waist and buried his face in her neck; and then, all at once, she awoke, shivered and collected herself, without warning shook herself free, and hit her bully a blow on the nose with all her force.

He reeled back, with his hands to his face; the blood gushed over his fingers. Then all were on their feet, and a scuffle began, the most unequal you can conceive, and the most impossible. It was all against one, with stones flying and imprecations after them, and in the midst the tawny-haired girl fighting like one possessed.

A minute of this—hardly so much—was more than enough for Manvers, who, when he could believe his eyes, pricked headlong into the fray, and began to lay about him with his crop. "Dogs, sons of dogs, down with your hands!" he cried, in Spanish which was fluent, if imaginative. But his science with the whip was beyond dispute, and the diversion, coming suddenly from behind, scattered the enemy into headlong flight.

The field cleared, the girl was to be seen. She lay moaning on the ground, her arms extended, her right leg twitching. She was bleeding at the ear.

Now, Manvers was under fire; for the enemy, reinforced by stragglers from the town, had unmasked a battery of stones, and was making fine practice from the ruins of the wall. He was hit more than once, his horse more than he; both were exasperated, and he in particular was furious at the presence of spectators who, comfortably in the shade, watched, and had been watching, the whole affair with enviable detachment of mind and body. With so much to chafe him, he may be pardoned for some irritability.

He dismounted as coolly as he could, and led his horse about to cover her from the stones. "Come," he said, as he stooped to touch her, "I must move you out of this. Saint Stephen—blessed young man—has forestalled this particular means of going to Heaven. Oh, damn the stones!"

He used no ceremony, but picked her up as if she had been a dressmaker's dummy, and set her on her feet, where, after swaying about, and some balancing with her hands, she presently steadied herself, and stood, dazed and empty-eyed. Her cheek was cut, her ear was bleeding; her hair was down, the red handkerchief uncoiled; her dusky skin was stained with dirt and scratches, and her bosom heaved riotously as she caught for her breath.

"Take your time, my dear," said Manvers kindly. And she did, by tumbling into his arms. Here, then, was a situation for the student of Manners; a brisk discharge of stones from an advancing line of skirmishers, a strictly impartial crowd of sightseers, a fidgety horse, and himself embarrassed by a girl in a faint.

He called for help and, getting none, shook his fist at the callous devils who ignored him; he inspected his charge, who looked as pure as a child in her swoon, all her troubles forgotten and sins blotted out; he inquired of the skies, as if hopeful that the ravens, as of old, might bring him help; at last, seeing nothing else for it, he picked up the girl in both arms and pitched her on to the saddle. There, with some adjusting, he managed to prop her while he led the horse slowly away. He had to get the reins in his teeth before he had gone ten yards. The retreat began.

It was within two hours of noon, or nothing had saved him from a retirement as harassing as Sir John Moore's. It was the sun, not ravens, that came to his help. Meantime the girl had recovered herself somewhat, and, when they were out of sight of the town and its inhabitants, showed him that she had by sliding from the saddle and standing firmly on her feet.

"Hulloa!" said Manvers. "What's the matter now? Do you think you can walk back? You can't, you know." He addressed her in his best Castilian. "I am afraid you are hurt. Let me help——" but she held him off with a stiffening arm, while she wiped her face with her petticoat, and put herself into some sort of order.

She did it deftly and methodically, with the practised hands of a woman used to the public eye. She might have been an actress at the wings, about to go on. Nor would she look at him or let him see that she was aware of his presence until all was in order—her hair twisted into the red handkerchief, the neck of her dress pinned together, her torn skirt nicely hung. Her coquetry, her skill in adjusting what seemed past praying for, her pains with herself, were charming to see and very touching. Manvers watched her closely and could not deny her beauty.

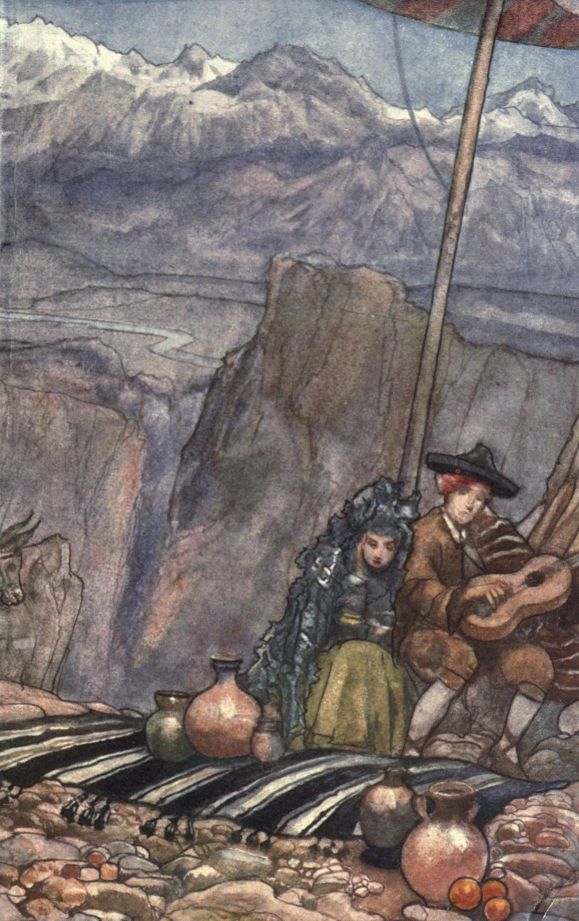

She was a vivid beauty, fiercely coloured, with her tawny gold hair, sunburnt skin, and jade-green, far-seeing eyes, her coiled crimson handkerchief and blue-green gown. She was finely made, slim, and in contour hardly more than a child; and yet she seemed to him very mature, a practised hand, with very various knowledge deep in her eyes, and a wide acquaintance behind her quiet lips. With her re-ordered toilette she had taken on self-possession and dignity, a reserve which baffled him. Without any more reason than this he felt for her a kind of respect which nothing, certainly, in what he had seen of her circumstances could justify. Yet he gave her her title—which marks his feeling.

"Señorita," he said, "I wish to be of service to you. Command me. Shall I take you back to Palencia?"

She answered him seriously. "I beg that you will not, sir."

"If you have friends——" he began, and she said at once, "I have none."

"Or parents——"

"None."

"Relatives——"

"None, none."

"Then your——"

"I know what you would say. I have no house."

"Then," said Manvers, looking vaguely over the plain, "what do you wish me to do for you?"

She was now sitting by the roadside, very collectedly looking down at her hands in her lap. "You will leave me here, if you must," she said; "but I would ask your charity to take me a little farther from Palencia. Nobody has ever been kind to me before."

She said this quite simply, as if stating a fact. He was moved.

"You were unhappy in Palencia?"

"Yes," she said, "I would rather be left here." The enormous plain of Castile, treeless, sun-struck, empty of living thing, made her words eloquent.

"Absurd," said Manvers. "If I leave you here you will die."

"In Palencia," said the girl, "I cannot die." And then her grave eyes pierced him, and he knew what she meant.

"Great God!" said Manvers. "Then I shall take you to a convent."

She nodded her head. "Where you will, sir," she replied. Her gravity, far beyond her seeming station, gave value to her confidence.

"That seems to me the best thing I can do with you," Manvers said; "and if you don't shirk it, there is no reason why I should. Now, can you stick on the saddle if I put you up?"

She nodded again. "Up you go then." He would have swung her up sideways, lady-fashion; but she laughed and cried, "No, no," put a hand on his shoulder, her left foot in the stirrup, and swung herself into the saddle as neatly as a groom. There she sat astride, like a circus-rider, and stuck her arm akimbo as she looked down for his approval.

"Bravo," said Manvers. "You have been a-horseback before this, my girl. Now you must make room for me." He got up behind her and took the reins from under her arm. With the other arm it was necessary to embrace her; she allowed it sedately. Then they ambled off together, making a Darby and Joan affair of it.

But the sun was now close upon noon, burning upon them out of a sky of brass. There was no wind, and the flies were maddening. After a while he noticed that the girl simply stooped her head to the heat, as if she were wilting like a picked flower. When he felt her heavy on his arm he saw that he must stop. So he did, and plied her with wine from his pocket-flask, feeding her drop by drop as she lay back against him. He got bread out of his haversack and made her eat; she soon revived, and then he learned the fact that she had eaten nothing since yesterday's noon. "How should I eat," she asked, "when I have earned nothing?"

"Nohow, but by charity," he agreed. "Had Palencia no compassion?" She grew dark and would not answer him at first; presently asked, had he not seen Palencia?

"I agree," he said. "But let me ask you, if I may without indiscretion, how did you propose to earn your bread in Palencia?"

"I would have worked in the fields for a day, sir," she told him; "but not longer, for I have to get on."

"Where do you wish to go?"

"Away from here."

"To Valladolid?"

She looked up into his face—her head was still near his shoulder. "To Valladolid? Never there."

This made him laugh. "To Palencia? Never there. To Valladolid? Never there. Where then, lady of the sea-green eyes?"

She veiled her eyes quickly. "To Madrid, I suppose. I wish to work."

"Can you find work there?"

"Surely. It is a great city."

"Do you know it?"

"Yes, I was there long ago."

"What did you do there?"

"I worked. I was very well there." She sat up and looked back over his shoulder. She had done that once or twice before, and now he asked her what she was looking for. She desisted at once: "Nothing" was her answer.

He made her drink from the flask again and gave her his pocket handkerchief to cover her head. When she understood she laughed at him without disguise. Did he think she feared the sun? She bade him look at her neck—which was walnut brown, and sleek as satin; but when he would have taken back his handkerchief she refused to give it, and put it over her head like a hood, and tied it under her chin. She then turned herself round to face him. "Is it so you would have it, sir?" she asked, and looked bewitching.

"My dear," said Manvers, "you are a beauty." Shall he be blamed if he kissed her? Not by me, since she never blamed him.

Her clear-seeing eyes searched his face; her kissed mouth looked very serious, and also very pure. Then, as he observed her ardently, she coloured and looked down, and afterwards turned herself the way they were to go, and with a little sigh settled into his arm.

Manvers spurred his horse, and for some time nothing was said between them. But he was of a talkative habit, with a trick of conversing with himself for lack of a better man. He asked her if he was forgiven, and felt her answer on his arm, though she gave him none in words. This was not to content him. "I see that you will not," he said, to tease her. "Well, I call that hard after my stoning. I had believed the ladies of Spain kinder to their cavaliers than to grudge a kiss for a cartload of stones at the head. Well, well, I'm properly paid. Laws go as kings will, I know. God help poor men!" He would have gone on with his baiting had she not surprised him.

She turned him a burning face. "Caballero, caballero, have done!" she begged him. "You rescued me from worse than death—and what could I deny you? See, sir, I have lived fifteen, seventeen years in the world, and nobody—nobody, I say—has ever done me a kindness before. And you think that I grudge you!" She was really unhappy, and had to be comforted.

They became close friends after that. She told him her name was Manuela, and that she was Valencian by birth. A Gitana? No, indeed. She was a Christian. "You are a very bewitching Christian, Manuela," he told her, and drew her face back, and kissed her again. I am told that there's nothing in kissing, once: it's the second time that counts. In the very act—for eyes met as well as lips—he noticed that hers wavered on the way to his, beyond him, over the road they had travelled; and the ceremony over, he again asked her why. She passed it off as before, saying that she had looked at nothing, and begged him to go forward.

Ahead of them now, through the crystalline flicker of the heat, he saw the dark rim of the wood, the cork forest of La Huerca for which he was looking, and which hid the river from his aching eyes. No foot-burnt wanderer in Sahara ever hailed his oasis with heartier thanksgiving; but it was still a league and a half away. He addressed himself to the task of reaching it, and we may suppose Manuela respected his efforts. At any rate, there was silence between the pair for the better part of an hour—what time the unwinking sun, vertically overhead, deprived them of so much as the sight of their own shadows, and drove the very crows with wings adust to skulk in the furrows. The shrilling of crickets, the stumbling hoofs of an overtaxed horse, and the creaking of saddle and girth made a din in the deadly stillness of this fervent noon, and, since there was no other sound to be heard, it is hard to tell how Manvers was aware of a traveller behind him, unless he was served by the sixth sense we all have, to warn as that we are not alone.

Sure enough, when he looked over his shoulder, he was aware of a donkey and his rider drawing smoothly and silently near. The pair of them were so nearly of the colour of the ground, he had to look long to be sure; and as he looked, Manuela suddenly leaned sideways and saw what he saw. It was just as if she had received a stroke of the sun. She stiffened; he felt the thrill go through her; and when she resumed her first position she was another person.

"God save your grace," said Estéban; for it was he who, sitting well back upon his donkey's rump, with exceedingly bright eyes and a cheerful grin, now forged level with Manvers and his burdened steed.

Manvers gave him a curt "Good-day," and thought him an impudent fellow—which was not justified by anything Estéban had done. He had been discretion itself; and, indeed, to his eyes there had been nothing of necessity remarkable in the pair on the horse. If a lady—Duchess or baggage—happened to be sharing the gentleman's saddle, an arrangement must be presumed, which could not possibly concern himself. That is the reasonable standpoint of a people who mind their own business and credit their neighbours with the same preoccupation.

But Manvers was an Englishman, and could not for the life of him consider Estéban as anything but a puppy for seeing him in a compromising situation. So much was he annoyed that he did not remark any longer that Manuela was another person, sitting stiffly, strained against his arm, every muscle on the stretch, as taut as a ship's cable in the tideway, her face in rigid profile to the newcomer.

Estéban was in no way put out. "Many good days light upon your grace!" he cheerfully repeated—so cheerfully that Manvers was appeased.

"Good-day, good-day to you," he said. "You ride light and I ride heavy, otherwise you had not overtaken us."

Estéban showed his fine teeth, and waved his hand towards the hazy distance; from the tail of his eye he watched Manuela in profile. "Who knows that, sir? Lo que ha de ser—as we say. Ah, who knows that?" Manuela strained her face forward.

"Well," said Manvers, "I do, for example. I have proved my horse. He's a Galician, and a good goer. It would want a brave borico to outpace him."

Estéban slipped into the axiomatic, as all Spaniards will. "There's a providence of the road, sir, and a saint in charge of travellers. And we know, sir, a cada puerco viene su San Martin." Manuela stooped her body forward, and peered ahead, as one strains to see in the dark.

"Your proverb is oddly chosen, it seems to me," said Manvers.

Estéban gave a little chuckle from his throat.

"A proverb is a stone flung into a pack of starlings. It may scare the most, but may hit one. By mine I referred to the ways of providence, under a figure. Destiny is always at work."

"No doubt," said Manvers, slightly bored.

"It might have been your destiny to have outpaced me: the odds were with you. On the other hand, as you have not, it must have been mine to have overtaken you."

"You are a philosopher?" asked Manvers, fatigue deliberately in his voice. Estéban's eyes shone intensely; he had marked the changed inflection.

"I studied the Humanities at Salamanca," he said carelessly. "That was when I was an innocent. Since then I have learned in a harder school. I am learning still—every day I learn something new. I am a gentleman born, as your grace has perceived: why not a philosopher?"

Manvers was rather ashamed of himself. "Of course, of course! Why not indeed? I am very glad to see you, while our ways coincide."

Estéban raised his battered straw. "I kiss the feet of your grace, and hope your grace's lady"—Manuela quivered—"is not disturbed by my company; for to tell you the truth, sir, I propose to enjoy your own as long as you and she are agreeable. I am used to companionship." He shot a keen glance at Manuela, who never moved.

"She will speak for herself, no doubt," said Manvers; but she did not. The gleam in Estéban's light eyes gave point to his next speech.

"I have a notion that the señora is not of your mind, sir," he said, "and am sorry. I can hardly remain as an unwelcome third in a journey. It would be a satisfaction to me if the señora would assure me that I am wrong." Manuela now turned her head with an effort and looked down upon the grinning youth.

"Why should I care whether you stay or go?" she said. Her eyelids flickered over her eyes as though he were dust in their light. He showed his teeth.

"Why indeed, señora? God knows I have no reputation to bring you, though the company of a gentleman, the son of a gentleman, never comes amiss, they say. But two is company, and three is a fair. I have found it so, and so doubtless has your ladyship."

She made him no answer, and had turned away her face long before he had finished. After that the conversation was mainly of his making; for Manuela would say nothing, and Manvers had nothing to say. The cork wood was plain in front of him now; he thanked God for the prospect of food and rest. In fifteen minutes, thought he, he should be swimming in the Pisuerga.

The forest began tentatively, with heath, sparse trees and mounds of cistus and bramble. Manvers followed the road, which ran through a portion of it, until he saw the welcome thickets on either hand, deep tunnels of dark and shadowy places where the sun could not stab; then he turned aside over the broken ground, and Estéban's donkey picked a dainty way behind him. When he had reached what seemed to him perfection, he pulled up.

"Now, young lady," he said; "I will give you food and drink, and then you shall go to sleep, and so will I. Afterwards we will consider what had best be done with you."

"Yes, sir," she replied in a whisper. Manvers dismounted and held out his hand to her. There was no more coquetting with the saddle. She scarcely touched his hand, and did not once lift her eyes to him—but he was busy with his haversack and had no thoughts for her.

Estéban meantime sat the donkey, looking gravely at his company, blinking his eyes, smiling quietly, recurring now and then to the winding minor air which had been in his head all day. He was perfectly unhampered by any doubts of his welcome, and watched with serious attention the preparations for a meal in the open which Manvers was making with the ease and despatch of one versed in camps.

Ham and sausage, rolls of bread, a lettuce, oranges, cheese, dates, a bottle of wine, another of water, salt, olives, a knife and fork, a plate, a corkscrew; every article was in its own paper, some were marked in pencil what they were. All were spread out upon a horse-blanket; in good enough order for a field-inspection. Nothing was wanting, and Estéban was as keen as a wolf. Even Manvers rubbed his hands. He looked shrewdly at his neighbour.

"Good alforjas, eh?"

"Excellent indeed, sir," said Estéban hoarsely. It was hard to see this food, and know that he could not eat of it. Manuela was sitting under a tree, her face in her hands.

"How far away," said Manvers, "is the water, do you suppose?"

The water? Estéban collected himself with a start. The water? He jerked his head towards the display on the blanket. "It is under your hand, caballero. That bottle, I take it, holds water."

Manvers laughed. "Yes, yes. I mean the river. I am going to swim in the river. Don't wait for me." He turned to the girl. "Take some food, my friend. I'll be back before long."

Her swift transitions bewildered him. She showed him now a face of extreme terror. She was on her feet in a moment, rigid, and her eyes were so pale that her face looked empty of eyes, like a mask. What on earth was the matter with her? He understood her to be saying, "I must go where you go. I must never leave you——" words like that; but they came from her mouthed rather than voiced, as the babbling of a mad woman. All that was clear was that she was beside herself with fright. Looking to Estéban for an explanation, he surprised a triumphant gleam in that youth's light eyes, and saw him grinning—as a dog grins, with the lip curled back.

But Estéban spoke. "I think the lady is right, sir. Affection is a beautiful thing." He added politely, "The loss will be mine."

Manvers looked from one to the other of these curious persons, so clearly conscious of each other, yet so strict to avoid recognition. His eyes rested on Manuela. "What's the matter, my child?" She met his glance furtively, as if afraid that he was angry; plainly she was ashamed of her panic. Her eyes were now collected, her brow cleared, and the tension of her arms relaxed.

"Nothing is the matter," she said in a low voice. "I will stay here." She was shaking still; she held herself with both her hands, and shook the more.

"I think that you are knocked over by the heat and all the rest of your troubles," said Manvers, "and I don't wonder. Repose yourself here—eat—drink. Don't spare the victuals, I beg. And as for you, my brother, I invite you too to eat what you please. And I place this young lady in your charge. Don't forget that. She's had a fright, and good reason for it; she's been hurt. I leave her in your care with every confidence that you will protect her."

Every word spoken was absorbed by Estéban with immense relish. The words pleased him, to begin with, by their Spanish ring. Manvers had been pleased himself. It was the longest speech he had yet made in Castilian; but he had no notion, of course, how exquisitely apposite to the situation they were.

Estéban became superb. He rose to the height of the argument, and to that of his inches, took off his old hat and held it out the length of his arm. "Let the lady fear nothing, señor caballero of my soul. I engage the honour of a gentleman that she shall have every consideration at my hands which her virtues merit. No more"—he looked at the sullen beauty between him and the Englishman—"No more, for that would be idolatrous; and no less, for that would be injustice. Vaya, señor caballero, vaya Vd con Dios." Manvers nodded and strolled away.

His removal snapped a chain. These two persons became themselves.

Manuela with eyes ablaze strode over to Estéban. "Well," she said. "You have found me. What is your pleasure?"

He sat very still on his donkey, watching her. He rolled himself a cigarette, still watching, and as he lighted it, looked at her over the flame.

"Speak, Estéban," she said, quivering; but he took two luxurious inhalations first, discharged in dense columns through his nose. Then he said, breathing smoke, "I have come to kill you, Manuelita—from Pobledo in a day and a half."

She had folded her arms, and now nodded. "I know it. I have expected you."

"Of course," said Estéban, inhaling enormously. He shot the smoke upwards towards the light, where it floated and spread out in radiant bars of blue. Manuela was tapping her foot.

"Well, I am here," she said. "I might have left you, but I have not. Why don't you do what you intend?"

"There is plenty of time," said Estéban, and continued to smoke. He began to make another cigarette.

"Do you know why I chose to stay with you?" she asked him softly. "Do you know, Estéban?"

He raised his eyebrows. "Not at all."

"It was because I had a bargain to make with you."

He looked at her inquiringly; but he shrugged. "It will be a hard bargain for you, my girl," he told her.

"I believe you will agree to it," she said quickly, "seeing that of my own will I have remained here. I will let you kill me as you please—on a condition."

"Name your condition," said Estéban. "I will only say now that it is my wish to strangle you with my hands."

She put both hers to her throat. "Good," she said. "That shall be your affair. But let the caballero go free. He has done you no harm."

"On the contrary," said Estéban, "I shall certainly kill him when he returns. Have no doubt of that. Then I shall have his horse."

Immediately, without fear, she went up to him where he sat his donkey. She saw the knife in his faja, but had no fear at all. She came quite close to him, with an ardent face, with eyes alight. She stretched out her arms like a man on a cross.

"Kill, kill, Estéban! But listen first. You shall spare that gentleman's life, for he has done you no wrong."

He laughed her down. "Wrong! And you come to me to swear that on the Cross of Christ? Daughter of swine, you lie."

Tears were in her eyes, which made her blink and shake her head—but she came closer yet in a passion of entreaty. She was so close that her bosom touched him. "Kill, Estéban, kill—but love me first!" Her arms were about him now, as if she must have love of him or die. "Estéban, Estéban!" she was whispering as if she hungered and thirsted for him. He shivered at a memory. "Love me once, love me once, Estéban!" Closer and closer she clung to him; her eyes implored a kiss.

"Loose me, you jade," he said, less sharply, but she clove the closer to him, and one hand crept downwards from his shoulder, as if she would embrace him by the middle. "Too late, Manuelita, too late," he said again, but he was plainly softening. She drew his face towards hers as if to kiss him, then whipped the long knife out of his girdle and drove it with all her sobbing force into his neck. Estéban uttered a thick groan, threw his head up and rocked twice. Then his head dropped, and he fell sideways off his donkey.

She stood staring at what she had done.

Manvers returned whistling from his bath, at peace with all the world of Spain, in a large mood of benevolence and charitable judgment. His mind dwelt pleasantly on Manuela, but pity mixed with his thought; and he added some prudence on his own account. "That child—she's no more—I must do something for her. Not a bad 'un, I'll swear, not fundamentally bad. I don't doubt her as I doubt the male: he's too glib by half... She's distractingly pretty—what nectarine colour! The mouth of a child—that droop at the corners—and as soft as a child's too." He shook his head. "No more kissing or I shall be in a mess."

When he reached his tree and his luncheon, to find his companions gone, he was a little taken aback. His genial proposals were suddenly chilled. "Queer couple—I had a notion that they knew something of each other. So they've made a match of it."

Then he saw a brass crucifix lying in the middle of his plate. "Hulloa!" He stooped to pick it up. It was still warm. He smiled and felt a glow come back. "Now that's charming of her. That's a pretty touch—from a pretty girl. She's no baggage, depend upon it." The string had plainly hung the thing round her neck, the warmth was that of her bosom. He held it tenderly while he turned it about. "I'll warrant now, that was all she had upon her. Not a maravedi beside. I know it's the last thing to leave 'em. I'm repaid, more than repaid. I'll wear you for a bit, my friend, if you won't scorch a heretic." Here he slipped the string over his head, and dropped the cross within his collar. "I'll treat you to a chain in Valladolid," was his final thought before he consigned Manuela to his cabinet of memories.

He poured and drank, hacked at his ham-bone and ate. "By the Lord," he went on commenting, "they've not had bite or sup. Too busy with their match-making? Too delicate to feast without invitation? Which?" He pondered the puzzle. He had invited Manuela, he was sure: had he included her swain? If not, the thing was clear. She wouldn't eat without him, and he couldn't eat without his host. It was the best thing he knew of Estéban.

He finished his meal, filled and lit a pipe, smoked half of it drowsily, then lay and slept. Nothing disturbed his three hours' rest, not even the gathering cloud of flies, whose droning over a neighbouring thicket must have kept awake a lighter sleeper. But Manvers was so fast that he did not hear footsteps in the wood, nor the sound of picking in the peaty ground.

It was four o'clock and more when he awoke, sat up and looked at his watch. Yawning and stretching at ease, he then became aware of a friar, with a brown shaven head and fine black beard, who was digging near by. This man, whose eyes had been upon him, waiting for recognition, immediately stopped his toil, struck his spade into the ground, and came towards him, bowing as he came.

"Good evening, señor caballero," he said. "I am Fray Juan de la Cruz, at your service; from the convent of N. S. de la Peña near by. I have to be my own grave-digger; but will you be so obliging as to commit the body while I read the office?"

To this abrupt invitation Manvers could only reply by staring. Fray Juan apologised.

"I imagined that you had perceived my business," he said, "which truly is none of yours. It will be an act of charity on your part—therefore its own reward."

"May I ask you," said Manvers, now on his feet, "what, or whom, you are burying?"

"Come," the friar replied. "I will show you the body." Manvers followed him into the thicket.

"Good God, what's this?" The staring light eyes of Estéban Vincaz had no reply for him. He had to turn away, sick at the sight.

Fray Juan de la Cruz told him what he knew. A young girl, riding an ass, had come to the church of the convent, where he happened to be, cleaning the sanctuary. The Reverend Prior was absent, the brothers were afield. She was in haste, she said, and the matter would not allow of delay. She reported that she had killed a man in the wood of La Huerca, to save the life of a gentleman who had been kind to her, who had, indeed, but recently imperilled his own for hers. "If you doubt me," she had said, "go to the forest, to such and such a part. There you will find the gentleman asleep. He has a crucifix of mine. The dead man lies not far away, with his own knife near him, with which I killed him. Now," she had said, "I trust you to report all I have said to that gentleman, for I must be off."

"Good God!" said Manvers again.

"God indeed is the only good," said Fray Juan, "and His ways past finding out. But I have no reason to doubt this girl's story. She told me, moreover, the name of the man—or his names, as you may say."

"Had he more than one then?" Manvers asked him, but without interest. The dead was nothing to him, but the deed was much. This wild girl, who had been sleek and kissing but a few hours before, now stood robed in tragic weeds, fell purpose in her green eyes! And her child's mouth—stretched to murder! And her youth—hardy enough to stab!

"The unfortunate young man," said Fray Juan, "was the son of a more unfortunate father; but the name that he used was not that of his house. His father, it seems——" but Manvers stopped him.

"Excuse me—I don't care about his father or his names. Tell me anything more that the girl had to say."

"I have told you everything, señor caballero," said Fray Juan; "and I will only add that you are not to suppose that I am violating the confidences of God. Far from that. She made no confession in the true sense, though she promised me that she would not fail to do so at the earliest moment. I had it urgently from herself that I should seek you out with her tale, and rehearse it to you. In justice to her, I am now to ask you if it is true, so far as you are concerned in it?"

Manvers replied, "It's perfectly true. I found her in bad company at Palencia; a pack of ruffians was about her, and she might have been killed. I got her out of their hands, knocked about and wounded, and brought her so far on the road to the first convent I could come at. That poor devil there overtook us about a league from the wood. She had nothing to say to him, nor he to her, but I remember noticing that she didn't seem happy after he had joined us. He had been her lover, I suppose?"

"She gave me to understand that," said Fray Juan gravely. Manvers here started at a memory.

"By the Lord," he cried, "I'll tell you something. When we got to the wood I wanted to bathe in the river, and was going to leave those two together. Well, she was in a taking about that. She wanted to come with me—there was something of a scene." He recalled her terror, and Estéban's snarling lip. "I might have saved all this—but how was I to know? I blame myself. But what puzzles me still is why the man should have wanted my life. Can you explain that?"

Fray Juan was discreet. "Robbery," he suggested, but Manvers laughed.

"I travel light," he said. "He must have seen that I was not his game. No, no," he shook his head. "It couldn't have been robbery."

Fray Juan, I say, was discreet; and it was no business of his.... But it was certainly in his mind to say that Estéban need not have been the robber, nor Manvers' portmanteau the booty. However, he was silent, until the Englishman muttered, "God in Heaven, what a country!" and then he took up his parable.

"All countries are very much the same, as I take it, since God made them all together, and put man up to be the master of them, and took the woman out of his side to be his blessing and curse at once. The place whence she was taken, they say, can never fully be healed until she is restored to it; and when that is done, it is not a certain cure. Such being the plan of this world, it does not become us to quarrel with its manifestations here or there. Señor caballero, if you are ready I will proceed. Assistance at the feet, a handful of earth at the proper moment are all I shall ask of you." He slipped a surplice over his head. The office was said.

"Fray Juan," said Manvers at the end, "will you take this trifle from me? A mass, I suppose, for that poor devil's soul would not come amiss."

Fray Juan took that as a sign of grace, and was glad that he had held his tongue. "Far from it," he said, "it would be extremely proper. It shall be offered, I promise you."

"Now," said Manvers after a pause, "I wonder if you can tell me this. Which way did she go off?"

Fray Juan shook his head. "No lo sé. She came to me in the church, and spoke, and passed like the angel of death. May she go with God!"

"I hope so," said Manvers. Then he looked into the placid face of the brown friar. "But I must find her somehow." Upon that addition he shut his mouth with a snap. The survey which he had to endure from Fray Juan's patient eyes was the best answer to it.

"Oh, but I must, you know," he said.

"Better not, my son," said Fray Juan. "It seems to me that you have seen enough. Your motives will be misunderstood."

Manvers laughed. "They are rather obscure to me—but I can't let her pay for my fault."

"You may make her pay double," said Fray Juan.

"No," said Manvers decisively, "I won't. It's my turn to pay now."

The Friar shrugged. "It is usually the woman who pays. But lo que ha de ser...!"

The everlasting phrase! "That proverb serves you well in Spain, Fray Juan," said Manvers, who was in a staring fit.

"It is all we have that matters. Other nations have to learn it; here we know it."

Manvers mounted his horse and stooping from the saddle, offered his hand. "Adios, Fray Juan."

"Vaya Vd con Dios!" said the friar, and watched him away. "Pobrecita!" he said to himself—"unhappy Manuela!"

But Manvers was well upon his way, riding with squared jaw, with rein and spur towards Valladolid. He neither whistled nor chanted to the air; he was vacuus viator no longer, travelled not for pleasure but to get over the leagues. For him this country of distances and great air was not Castile, but Broceliande; a land of enchantments and pain. He was no longer fancy-free, but bound to a quest.

Consider the issues of this day of his. From bathing in pastoral he had been suddenly soused into tragedy's seething-pot. His idyll of the tanned gipsy, with her glancing eyes and warm lips, had been spattered out with a brushful of blood; the scene was changed from sunny life to wan death. Here were the staring eyes of a dead man, and his mouth twisted awry in its last agony. He could not away with the shock, nor divest himself of a share in it. If he, by mischance, had taken up with Manuela, he had taken up with Estéban too.

The vanished players in the drama loomed in his mind larger for that fateful last act. The tragic sock and the mask enhanced them. What mystery lay behind Manuela's sidelong eyes? What sin or suffering? What knowledge, how gained, justified Estéban's wizened saws? These two were wise before their time; when they ought to have been flirting on the brink of life, here they were, breasting the great flood, familiar with death, hating and stabbing!

A pretty child with a knife in her hand; and a boy murdered—what a country! And where stood he, Manvers, the squire of Somerset, with his thirty years, his University education and his seat on the bench? Exactly level with the curate, to be counted on for an archery meeting! Well enough for diversion; but when serious affairs were on hand, sent out of the way. Was it not so, that he, as the child of the party, was dismissed to bathe while his elders fought out their deadly quarrel? I put it in the interrogative; but he himself smarted under the answer to it, and although he never formulated the thought, and made no plans, and could make none, I have no doubt but that his wounded self-esteem, seeking a salve, found it in the assurance that he would protect Manuela from the consequences of her desperate act; that his protection was his duty and her need. The English mind works that way; we cannot endure a breath upon our fair surface. We must direct the operations of this world, or the devil's in it.

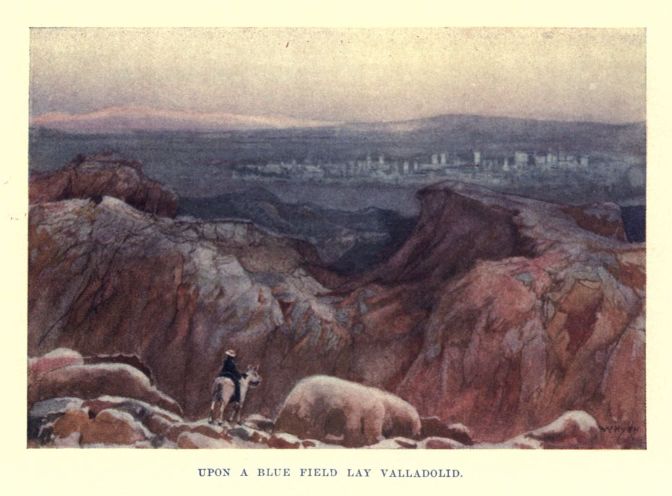

Manvers was not, of course, in love with Manuela. He was sentimentally engaged in her affairs, and very sure that they were, and must be, his own. Yet I don't know whether the waking dream which he had upon the summit of that plateau of brown rock which bounds Valladolid upon the north was the cause or consequence of his implication.

He had climbed this sharp ridge because a track wavered up it which cut off some miles of the road. It was not easy going by any means, but the view rewarded him. The land stretched away to the four quarters of the compass and disappeared into a copper-brown haze. He stood well above the plain, which seemed infinite. Corn-land and waste, river-bed and moor, were laid out below him as in a geographer's model. He thought that he stood up there apart, contemplating time and existence. He was indeed upon the convex of the world, projecting from it into illimitable space, consciously sharing its mighty surge.

This did not belittle him. On the contrary, he felt something of the helmsman's pride, something of the captain's on the bridge. He was driving the world. He soared, perched up there, apart from men and their concerns. All Spain lay at his feet; he marked the way it must go. It was possible for him now to watch a man crawl, like a maggot, from his cradle, and urge a painful way to his grave. And, to his exalted eye, from cradle to grave was but a span's length.

From such sublime investigation it was but a step to sublimity itself. His soul seemed separate from his body; he was dispassionate, superhuman, all-seeing and all-comprehending. Now he could see men as winged ants, crossing each other, nearing, drifting apart, interweaving, floating in a cloud, blown high, blown low by wafts of air; and here, presently, came one Manvers, and there, driven by a gust, went another, Manuela.

At these two insects, as one follows idly one gull out of a flock, he could look with interest, and without emotion. He saw them drift, touch and part, and each be blown its way, helpless mote in the dust of the great plain. From one to the other he turned his eyes. The Manvers gnat flew the straighter course, holding to an upper current; the Manuela wavered, but tended ever to a lower plane. The wind from the mountains of Asturias freshened and blew over him. In a singular moment of divination he saw the two insects of his vision caught in the draught and whirled together again. A spiral flight upwards was begun; in ever-narrowing circles they climbed, bid fair to soar. They reached a steadier stream, they sped along together; but then, as a gust took them, they dipped below it and steadily declined, wavering, whirling about each other. Down and down they went, until they were lost to his eye in the dust of heat. He saw them no more.

Manvers came to himself, and shook his senses back into his head. The sun was sinking over Portugal, the evening wind was chill. Had he been dreaming? What sense of fate was upon him? "Come up, Rosinante, take me out of the cave of Montesinos." He guided his horse in and out of the boulder-strewn track to the edge of the plateau; and there before him, many leagues away, like a patch of whitewash splodged down upon a blue field, lay Valladolid, the city of burning and pride.

If God in His majesty made the Spains and the nations which people them, perhaps it was His mercy that convoked the Spanish cities—as His servant Philip piled rock upon rock and called it Madrid—and made cess-pits for the cleansing of the country.

Behold the Castilian, the Valencian, the Murcian on his glebe, you find an exact relation established; the one exhales the other. The man is what his country is, tragic, hag-ridden, yet impassive, patient under the sun. He stands for the natural verities. You cannot change him, move, nor hurt him. He can earn neither your praises nor reproach. As well might you blame the staring noon of summer or throw a kind word to the everlasting hills. The bleak pride of the Castillano, the flint and steel of Aragon, the languor which veils Andalusian fire—travelling the lands which gave them birth, you find them scored in large over mountain and plain and riverbed, and bitten deep into the hearts of the indwellers. They are as seasonable there as the flowers of waste places, and will charm you as much. So Spanish travel is one of the restful relaxations, because nothing jars upon you. You feel that you are assisting a destiny, not breaking it. Not discovery is before you so much as realisation.

But in the city Spanish blood festers, and all that seemed plausible in the open air is now monstrous, full of vice and despair. Whereas, outside, the man stood like a rock, and let Fate seam or bleach him bare; here, within walls, he rages, shows his teeth, blasphemes, or sinks into sloth. You will find him heaped against the walls like ordure, hear him howl for blood in the bull-ring, appraise women, as if they were dainties, in the alamedas, loaf, scratch, pry where none should pry, go begging with his sores, trade his own soul for his mother's. His pride becomes insolence, his tragedy hideous revolt, his impassivity swinish, his rock of sufficiency a rook of offence. God in His mercy, or the Devil in his despite, made the cities of Spain.

And yet the man, so superbly at his ease in his enormous spaces, is his own conclusion when he goes to town; the permutation is logical. He is too strong a thing to break his nature; it will be aggravated but not deflected. Leave him to swarm in the plaza and seek his nobler brother. Go out by the gate, descend the winding suburb, which gives you the burnt plains and far blue hills, now on one hand, now on the other, as you circle down and down, with the walls mounting as you fall; touch once more the dusty earth, traverse the deep shade of the ilex-avenue; greet the ox-teams, the filing mules, as they creep up the hill to the town: you are bound for their true, great Spain. And though it may be ten days since you saw it, or fifty years, you will find nothing altered. The Spaniard is still the flower of his rocks. O dura tellus Iberiae!

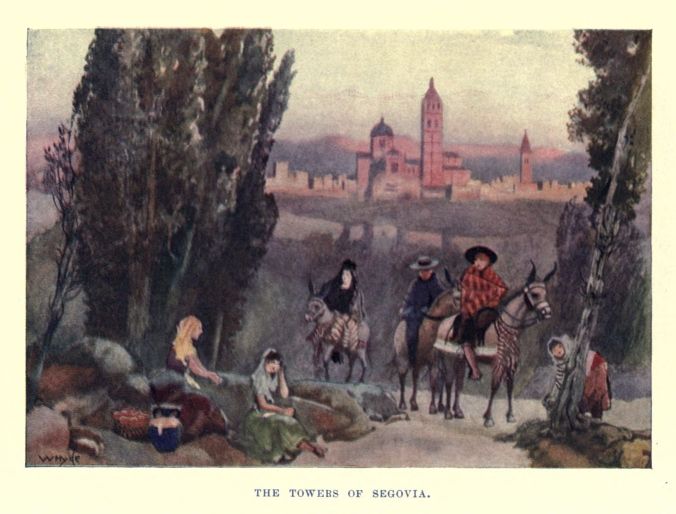

From the window of his garret Don Luis Ramonez de Alavia could overlook the town wall, and by craning his neck out sideways could have seen, if he had a mind, the cornice-angle of the palace of his race. It was a barrack in these days, and had been so since ruin had settled down on the Ramonez with the rest of Valladolid. That had been in the sixteenth century, but no Ramonez had made any effort to repair it. Every one of them did as Don Luis was doing now, and accepted misery in true Spanish fashion. Not only did he never speak of it, he never thought of it either. It was; therefore it had to be.

He rose at dawn, every day of his life, and took his sop in coffee in his bedgown, sitting on the edge of his bed. He heard mass in the Church of Las Angustias, in the same chapel at the same hour. Once a month he communicated, and then the sop was omitted. He was shaved in the barber's shop—Gomez the Sevillian kept it—at the corner of the plaza. Gomez, the little dapper, black-eyed man, was a friend of his, his newspaper and his doctor.

He took a high line with Gomez, as you may when you owe a man twopence a week.

That over, he took the sun in the plaza, up and down the centre line of flags in fine weather, up and down the arcade if it rained. He saw the diligence from Madrid come in, he saw the diligence for Madrid go out. He knew, and accepted the salutes of every arriero who worked in and out of the city, and passed the time of day with Micael the lame water-seller, who never failed to salute him.

At noon he ate an onion and a piece of cheese, and then he dozed till three. As the clock of the University struck that hour he put on his capa—summer and winter he wore it, with melancholy and good reason; by ten minutes past he was entering the shop of Sebastian the goldsmith, in the Plaza San Benito, in the which he sat till dusk, motionless and absorbed in thought, talking little, seeming to observe little, and yet judging everything in the light of strong common sense.

Summer or winter, at dusk he arose, flecked a mote or two of dust from his capa, seated his beaver upon his grey head, grasped his malacca, and departed with a "Be with God, my friend." To this Sebastian the goldsmith invariably replied, "At the feet of your grace, Don Luis."

He supped sparingly, and the last act of his day was his one act of luxury; his cup of chocolate or glass of agraz, according to season, at the Café de la Luna in the Plaza Mayor. This was his title to table and chair, and the respect of all Valladolid from dusk until nine—on the last stroke of which, saluting the company, who rose almost to a man, he retired to his garret and thin bed.

Pepe, the head waiter at the Luna, who had been there for thirty years, Gomez the barber, who was sixty-three and looked forty, Sebastian the goldsmith, well over middle age, and the old priest of Las Angustias, who had confessed him every Friday and said mass at the same altar every morning since his ordination (God knows how long ago), would have testified to the fact that Don Luis had never once varied his daily habits within time of memory.

They would have been wrong, of course, like all clean sweepers; for in addition to his inheritance of ruin, misfortunes had graved him deeply. Valladolid knew it well. His wife had left him, his son had gone to the devil. He bore the first blow like a stoic, not moving a muscle nor varying a habit: the second sent him on a journey. The barber, the water-seller, Pepe the waiter, Sebastian the deft were troubled about him for a week or more. He came back, and hid his wound, speaking to no one of it; and no one dared to pity him. And although he resumed his routine and was outwardly the same man, we may trace to that last stroke of Fortune the wasted splendour of his eyes, the look of a dying stag, which, once seen, haunted the observer. He was extraordinarily handsome, except for his narrow shoulders and hollow eyes, flawlessly clean in person and dress; a tall, straight, hawk-nosed, sallow gentleman. The Archbishop of Toledo was his first cousin, a cadet of his house. He was entitled to wear his hat in the presence of the Queen, and he lived upon fivepence a day.

Manvers, reaching Valladolid in the evening, reposed himself for a day or two, and recovered from his shock. He saw the sights, conversed with affability with all and sundry, drank agraz in the Café de la Luna. He must have beamed without knowing it upon Don Luis, for his brisk appearance, twisted smile and abrupt manner were familiar to that watchful gentleman by the time that, sweeping aside the curtain like a buffet of wind, he entered the goldsmith's shop in the Plaza San Benito. He came in a little before twilight one afternoon, holding by a string in one hand some swinging object, taking off his hat with the other as soon as he was past the curtain of the door.

"Can you," he said to Sebastian, in very fair Spanish, "take up a job for me a little out of the common?" As he spoke he swung the object into the air, caught it and enclosed it with his hand. Don Luis, in a dark corner of the shop, sat back in his accustomed chair, and watched him. He sat very still, a picture of mournful interest, shrouding his mouth in his hand.

Sebastian, first master of his craft in a city of goldsmiths, was far too much the gentleman to imply that any command of his customer need not be extraordinary. Bowing with gravity, and adjusting the glasses upon his fine nose, he replied that when he understood the nature of the business he should be better instructed for his answer. Thereupon Manvers opened his hand and passed over the counter a brass crucifix.

It is difficult to disturb the self-possession of a gentleman of Spain; Sebastian did not betray by a twitch what his feelings or thoughts may have been. He gravely scrutinised the battered cross, back and front, was polite enough to ignore the greasy string, and handed it back without a single word. It may have been worth half a real; to watch his treatment of it was cheap at a dollar.

Manvers, however, flushed with annoyance, and spoke somewhat loftily. "Am I to understand that you will, or will not oblige me?"