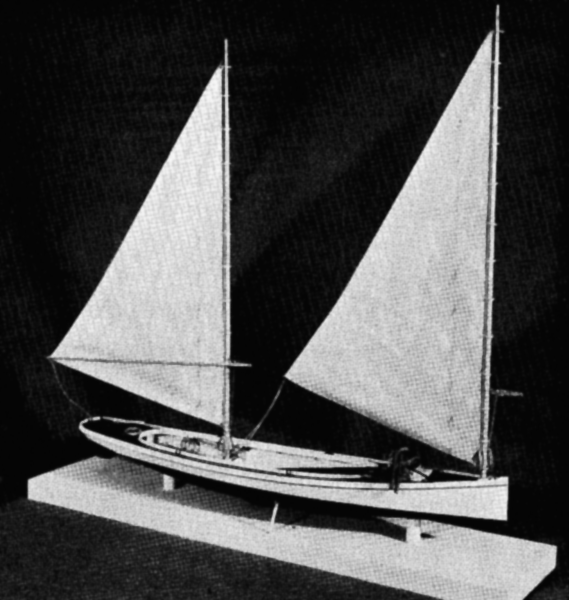

FIGURE 1.--Scale model of a New Haven sharpie of 1885,

complete with tongs. (_USNM 318023; Smithsonian photo 47033-C._)

FIGURE 1.--Scale model of a New Haven sharpie of 1885,

complete with tongs. (_USNM 318023; Smithsonian photo 47033-C._)

Title: The Migrations of an American Boat Type

Author: Howard Irving Chapelle

Release date: July 1, 2009 [eBook #29285]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Colin Bell, Woodie4, Joseph Cooper and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Contributions From

The Museum Of History And Technology:

Paper 25

The Migrations Of

An American Boat Type

Howard I. Chapelle

| THE NEW HAVEN SHARPIE | 136 |

| THE CHESAPEAKE BAY SHARPIE | 148 |

| THE NORTH CAROLINA SHARPIE | 149 |

| SHARPIES IN OTHER AREAS | 151 |

| DOUBLE-ENDED SHARPIES | 152 |

| MODERN SHARPIE DEVELOPMENT | 154 |

by Howard I. Chapelle

FIGURE 1.--Scale model of a New Haven sharpie of 1885,

complete with tongs. (_USNM 318023; Smithsonian photo 47033-C._)

FIGURE 1.--Scale model of a New Haven sharpie of 1885,

complete with tongs. (_USNM 318023; Smithsonian photo 47033-C._)

The New Haven sharpie, a flat-bottomed sailing skiff, was

originally developed for oyster fishing, about the middle of the

last century.

Very economical to build, easy to handle, maneuverable, fast and

seaworthy, the type was soon adapted for fishing along the eastern

and southeastern coasts of the United States and in other areas.

Later, because of its speed, the sharpie became popular for racing

and yachting.

This study of the sharpie type—its origin, development and

spread—and the plans and descriptions of various regional types

here presented, grew out of research to provide models for the hall

of marine transportation in the Smithsonian's new Museum of History

and Technology.

THE AUTHOR: Howard I. Chapelle is curator of transportation in the

U.S. National Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

For a commercial boat to gain widespread popularity and use, it must be suited to a variety of weather and water conditions and must have some very marked economic advantages over any other boats that might be used in the same occupation. Although there were more than 200 distinct types of small sailing craft employed in North American fisheries and in along-shore occupations during the last 60 years of the 19th century, only rarely was one of these boat types found to be so well suited to a particular occupation that its use spread to areas at any great distance from the original locale.

Those craft that were "production-built," generally rowing boats, were sold along the coast or inland for a variety of uses, of course. The New England dory, the seine boat, the Connecticut drag boat, and the yawl were such production-built boats.

In general, flat-bottomed rowing and sailing craft were the most widely used of the North American boat types. The flat-bottomed hull appeared in two basic forms: the scow, or punt, and the "flatiron," or sharp-bowed skiff. Most scows were box-shaped with raking or curved ends in profile; punts had their sides curved fore and aft in plan and usually had curved ends in profile. The rigs on scows varied with the size of the boat. A small scow might have a one-mast or two-mast spritsail rig, or might be gaff rigged; a large scow might be sloop rigged or schooner rigged. Flatiron skiffs were sharp-bowed, usually with square, raked transom stern, and their rigs varied according to their size and to suit the occupation in which they were employed. Many were sloop rigged with gaff mainsails; others were two-mast, two-sail boats, usually with leg-of-mutton sails, although occasionally some other kind of sail was used. If a skiff had a two-mast rig, it was commonly called a "sharpie"; a sloop-rigged skiff often was known as a "flattie." Both scows and flat-bottomed skiffs existed in Colonial times, and both probably originated in Europe. Their simple design permitted construction with relatively little waste of materials and labor.

Owing to the extreme simplicity of the majority of scow types, it is

usually impossible to determine whether scows used in different areas

were directly related in design and construction. Occasionally, however,

a definite relationship between scow types may be assumed because of

certain marked similarities in fitting and construction details. The

same occasion for doubt exists with regard to the relationships of

sharp-bowed skiffs of different areas, with one exception—the large,

flat-bottomed sailing skiff known as the "sharpie."

The sharpie was so distinctive in form, proportion, and appearance that her movements from area to area can be traced with confidence. This boat type was particularly well suited to oyster fishing, and during the last four decades of the 19th century its use spread along the Atlantic coast of North America as new oyster fisheries and markets opened. The refinements that distinguished the sharpie from other flat-bottomed skiffs first appeared in some boats that were built at New Haven, Connecticut, in the late 1840's. These craft were built to be used in the then-important New Haven oyster fishery that was carried on, for the most part, by tonging in shallow water.

The claims for the "invention" of a boat type are usually without the support of contemporary testimony. In the case of the New Haven sharpie two claims were made, both of which appeared in the sporting magazine Forest and Stream. The first of these claims, undated, attributed the invention of the New Haven sharpie to a boat carpenter named Taylor, a native of Vermont.[1] In the January 30, 1879, issue of Forest and Stream there appeared a letter from Mr. M. Goodsell stating that the boat built by Taylor, which was named Trotter, was not the first sharpie.[2] Mr. Goodsell claimed that he and his brother had built the first New Haven sharpie in 1848 and that, because of her speed, she had been named Telegraph. The Goodsell claim was never contested in Forest and Stream, and it is reasonable to suppose, in the circumstances, that had there been any question concerning the authenticity of this claim it would have been challenged.

No contemporary description of these early New Haven sharpies seems to be available. However, judging by records made in the 1870's, we may assume that the first boats of this type were long, rather narrow, open, flat-bottomed skiffs with a square stern and a centerboard; they were rigged with two masts and two leg-of-mutton sails. Until the appearance of the early sharpies, dugout canoes built of a single white pine log had been used at New Haven for tonging. The pine logs used for these canoes came mostly from inland Connecticut, but they were obtainable also in northern New England and New York. The canoes ranged from 28 to 35 feet in length, 15 to 20 inches in depth, and 3 feet to 3 feet 6 inches in beam. They were built to float on about 3 or 4 inches of water. The bottoms of these canoes were about 3 inches thick, giving a low center of gravity and the power to carry sail in a breeze. The canoes were rigged with one or two pole masts with leg-of-mutton sails stepped in thwarts. A single leeboard was fitted and secured to the hull with a short piece of line made fast to the centerline of the boat. With this arrangement the leeboard could be raised and lowered and also shifted to the lee side on each tack. This took the strain off the sides of the canoe that would have been created by the usual leeboard fitting.[3] Construction of such canoes ceased in the 1870's, but some remained in use into the present century.

The first New Haven sharpies were 28 to 30 feet long—about the same length as most of the log canoes. Although the early sharpie probably resembled the flatiron skiff in her hull shape, she was primarily a sailing boat rather than a rowing or combination rowing-sailing craft. The New Haven sharpie's development[4] was rapid, and by 1880 her ultimate form had been taken as to shape of hull, rig, construction fittings, and size. Some changes were made afterwards, but they were in minor details, such as finish and small fittings.

The New Haven sharpie was built in two sizes for the oyster fishery. One

carried 75 to 100 bushels of oysters and was 26 to 28 feet in length;

the other carried 150 to 175 bushels and was 35 to 36 feet in length.

The smaller sharpie was usually rigged with a single mast and sail,

though some small boats were fitted for two sails. The larger boat was

always fitted to carry two masts, but by shifting the foremast to a

second step more nearly amidships she could be worked with one mast and

sail. The New Haven sharpie retained its original proportions. It was

long, narrow, and low in freeboard and was fitted with a centerboard. In

its development it became half-decked. There was enough fore-and-aft

camber in the flat bottom so that, if the boat was not carrying[Pg 137] much

weight, the heel of her straight and upright stem was an inch or two

above the water. The stern, usually round, was planked with vertical

staving that produced a thin counter. The sheer was usually marked and

well proportioned. The New Haven sharpie was a handsome and graceful

craft, her straight-line sections being hidden to some extent by the

flare of her sides and the longitudinal curves of her hull.

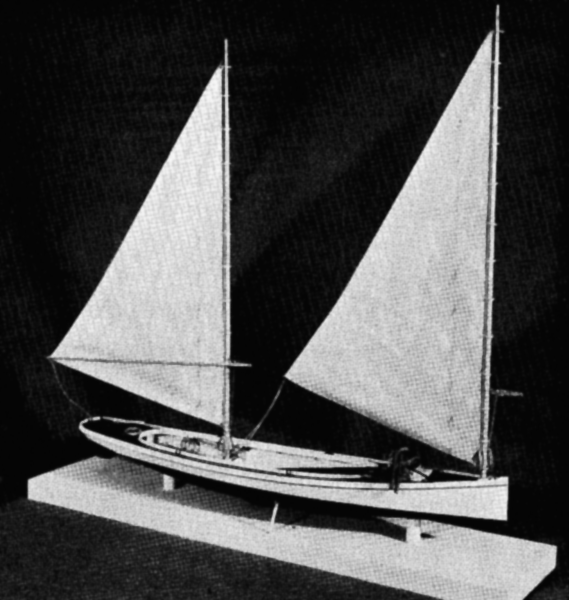

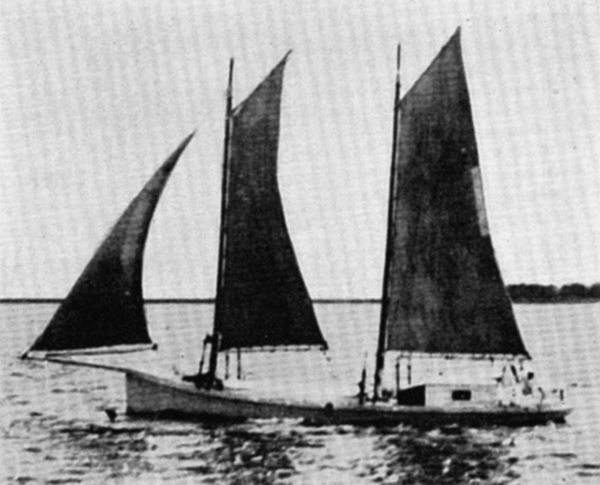

FIGURE 2.—A New Haven sharpie and dugouts on the

Quinnipiac River, New Haven, Connecticut, about the turn of the

century.

FIGURE 2.—A New Haven sharpie and dugouts on the

Quinnipiac River, New Haven, Connecticut, about the turn of the

century.

The structure of New Haven sharpies was strong and rather heavy, consisting of white pine plank and oak framing. The sides were commonly wide plank. Each side had two or three strakes that were pieced up at the ends to form the sheer. The sides of large sharpies were commonly 1½ inches thick before finishing, while those of the smaller sharpies were 1¼ inches thick. The sharpie's bottom was planked athwartships with planking of the same thickness as the sides and of 6 to 8 inches in width. That part of the bottom that cleared the water, at the bow and under the stern, was often made of tongue-and-groove planking, or else the seams athwartship would be splined. Inside the boat there was a keelson made of three planks, in lamination, standing on edge side by side, sawn to the profile of the bottom, and running about three-fourths to seven-eighths the length of the boat. The middle one of these three planks was omitted at the centerboard case to form a slot. Afore and abaft the slot the keelson members were cross-bolted and spiked. The ends of the keelson were usually extended to the stem and to the stern by flat planks that were scarphed into the bottom of the built-up keelson.

The chines of the sharpie were of oak planks that were of about the same

thickness as the side planks and 4 to 7 inches deep when finished. The

chine logs were sawn to the profile of the bottom and sprung to the

sweep of the sides in plan view. The side frames were mere cleats, 1½

by 3 inches. In the 1880's these cleats were shaped so that the inboard

face was 2 inches wide and the outboard face 3 inches wide, but later

this shaping was generally omitted.

At the fore end of the sharpie's centerboard case there was an edge-bolted bulkhead of solid white pine, 1¼ or 1½ inches thick, with scuppers cut in the bottom edge. A step about halfway up in this bulkhead gave easy access to the foredeck. In the 1880's that part of the bulkhead above the step was made of vertical staving that curved athwartships, but this feature was later eliminated. In the upper portion of the bulkhead there was often a small rectangular opening for ventilation.

The decking of the sharpie was made of white pine planks 1¼ inches thick and 7 to 10 inches wide. The stem was a triangular-sectioned piece of oak measuring 6 by 9 inches before it was finished. The side plank ran past the forward edge of the stem and was mitered to form a sharp cutwater. The miter was covered by a brass bar stemband to which was brazed two side plates 3/32 or ¼ inch thick. This stemband, which was tacked to the side plank, usually measured ½ or 5/8 inch by ¾ inch and it turned under the stem, running under the bottom for a foot or two. The band also passed over a stemhead and ran to the deck, having been shaped over the head of the stem by heating and molding over a pattern.

The sharpie's stern was composed of two horizontal oak frames, one at chine and one at sheer; each was about 1½ inches thick. The outer faces of these frames were beveled. The planking around the stern on these frames was vertical staving that had been tapered, hollowed, and shaped to fit the flare of the stern. This vertical staving was usually 1¾ inches thick before it was finished. The raw edges of the deck plank were covered by a false wale ½ to ¾ inch thick and 3 or 4 inches deep, and by an oak guard strip that was half-oval in section and tapered toward the ends. Vertical staving was used to carry the wale around the stern. The guard around the stern was usually of stemmed oak.

The cockpit ran from the bulkhead at the centerboard case to within 4 or

5 feet of the stern, where there was a light joiner bulkhead. A low

coaming was fitted around the cockpit and a finger rail ran along the

sides of the deck. The boat had a small square hatch in the foredeck and

two mast holes, one at the stem and one at the forward bulkhead. A tie

rod, 3/8 inch in diameter, passed through the hull athwartships, just

forward of the forward bulkhead; the ends of the tie rod were "up-set"

or headed over clench rings on the outside of the wale. The hull was

usually painted white or gray, and the interior color usually buff or

gray.[Pg 140]

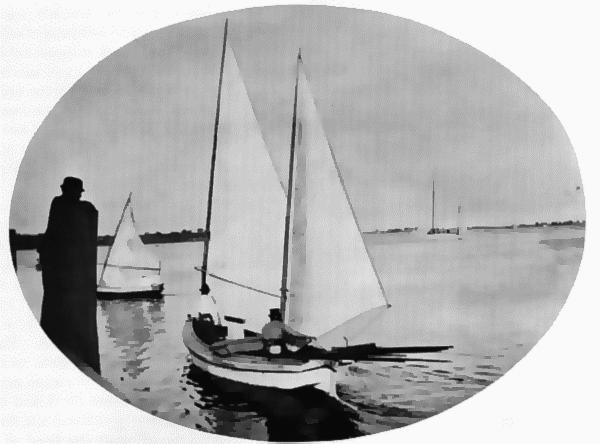

FIGURE 5.—Chesapeake Bay sharpie with daggerboard, about

1885. (Photo courtesy Wirth Munroe.)

FIGURE 5.—Chesapeake Bay sharpie with daggerboard, about

1885. (Photo courtesy Wirth Munroe.)

The two working masts of a 35-to 36-foot sharpie were made of spruce or white pine and had a diameter of 4½ to 5 inches at deck and 1½ inches at head. Their sail hoists were 28 to 30 feet, and the sail spread was about 65 yards. Instead of booms, sprits were used; these were set up at the heels with tackles to the masts. In most sharpies the sails were hoisted to a single-sheave block at the mast heads and were fitted with wood or metal mast hoops. Because of the use of the sprit and heel tackle, the conventional method of reefing was not possible. The reef bands of the sails were parallel to the masts, and reefing was accomplished by lowering a sail and tying the reef points while rehoisting. The mast revolved in tacking in order to prevent binding of the sprit under the tension of the heel tackle. The tenon at the foot of the mast was round, and to the shoulder of the tenon a brass ring was nailed or screwed. Another brass ring was fastened around the mast step. These rings acted as bearings on which the mast could revolve.

Because there was no standing rigging and the masts revolved, the sheets could be let go when the boat was running downwind, so that the sails would swing forward. In this way the power of the rig could be reduced without the bother of reefing or furling. Sometimes, when the wind was light, tonging was performed while the boat drifted slowly downwind with sails fluttering. The tonger, standing on the side deck or on the stern, could tong or "nip" oysters from a thin bed without having to pole or row the sharpie.

The unstayed masts of the sharpie were flexible and in heavy weather

spilled some wind, relieving the heeling moment of the sails to some

degree. In summer the 35-to 36-foot boats carried both masts, but in

winter, or in squally weather, it was usual to leave the mainmast ashore

and step the foremast in the hole just forward of the bulkhead at the

centerboard case, thereby balancing the rig in relation to the

centerboard. New Haven sharpies usually had excellent balance, and

tongers could sail them into a slip, drop the board so that it touched

bottom, and, using the large rudders, bring the boats into the wind by

spinning them almost within their length. This could be done because

there was no skeg. When sharpies[Pg 141] had skegs, as they did in some

localities, they were not so sensitive as the New Haven boats. If a

sharpie had a skeg, it was possible to use one sail without shifting the

mast, but at a great sacrifice in general maneuverability.

FIGURE 6.—North Carolina sharpie with one reef in

moderate gale, about 1885.

FIGURE 6.—North Carolina sharpie with one reef in

moderate gale, about 1885.Kunhardt[5]writing in the mid-1880's, described the New Haven sharpie as being 33 to 35 feet long, about 5 feet 9 inches to 6 feet wide on the bottom, and with a depth of about 36 inches at stem, 24 inches amidships, and 12 inches at stern. The flare increased rapidly from the bow toward amidships, where it became 3½ inches for every 12 inches of depth. The increase of flare was more gradual toward the stern, where the flare was equal to about 4 inches to the foot. According to Kunhardt, a 35-foot sharpie hull weighed 2,000 to 2,500 pounds and carried about 5 short tons in cargo.

The sharpie usually had its round stern carried out quite thin. If the

stern was square, the transom was set at a rake of not less than 45°.

Although it cost about $15 more than the transom stern, the round stern

was favored because tonging from it was easier; also, when the boat was

tacked, the round stern did not foul the main sheet and was also less

likely to ship a sea than was the square stern. Kunhardt remarks that

sharpies lay quiet when anchored by the stern, making the ground tackle

easier to handle.[Pg 142]

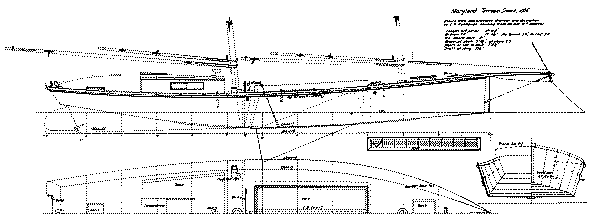

FIGURE 7.—Plan of a

Chesapeake Bay terrapin smack based on sketches and dimensions given by

C. P. Kunhardt in Small Yachts: Their Design and Construction,

Exemplified by the Ruling Types of Modern Practice, New York, 1886.

FIGURE 7.—Plan of a

Chesapeake Bay terrapin smack based on sketches and dimensions given by

C. P. Kunhardt in Small Yachts: Their Design and Construction,

Exemplified by the Ruling Types of Modern Practice, New York, 1886.The cost of the New Haven sharpie was very low. Hall stated that in 1880-1882 oyster sharpies could be built for as little as $200, and that large sharpies, 40 feet long, cost less than $400.[6]In 1886 a sharpie with a capacity for 150 to 175 bushels of oysters cost about $250, including spars and sails.[7]In 1880 it was not uncommon to see nearly 200 sharpies longside the wharves at Fairhaven, Connecticut, at nightfall.

The speed of the oyster sharpies attracted attention in the 1870's, and in the next decade many yachts were built on sharpie lines, being rigged either as standard sharpies or as sloops, schooners, or yawls.

Oyster tonging sharpies were raced, and often a sharpie of this type was built especially for racing. One example of a racing sharpie had the following dimensions:

| Length: | 35' | |

| Width on deck: | 8' | |

| Flare, to 1' of depth: | 4' | |

| Width of stern: | 4-1/2' | |

| Depth of stern: | 10" | |

| Depth at bow: | 36" | |

| Sheer: | 14" | |

| Centerboard: | 11' | |

| Width of washboards or sidedecks: |

12" | |

| Length of rudder: | 6' | |

| Depth of rudder: | 1'2" | |

| Height of foremast: | 45' | |

| Diameter of foremast: | 6" | |

| Head of foremast: | 1-1/2" | |

| Height of mainmast: | 40' | |

| Diameter of mainmast: | 5-1/2" | |

| Head of mainmast: | 1-1/2" |

The sharpie with the above dimensions was decked-over 10 feet foreward

and 4 feet aft. She carried a 17-foot plank bowsprit, to the ends of

which were fitted vertical clubs 8 to 10 feet long. When racing, this

sharpie carried a 75-yard foresail, a 60-yard mainsail, a 30-yard jib, a

40-yard squaresail, and a 45-yard main staysail; two 16-foot planks were

run out to windward and 11 members of the 12-man crew sat on them to

hold the boat from capsizing.

FIGURE 10.—North Carolina sharpie under sail.

FIGURE 10.—North Carolina sharpie under sail.

Figure 3 shows a plan of a sharpie built at the highest point in the development of this type boat. This plan makes evident the very distinct character of the sharpie in model, proportion, arrangement,[Pg 144] construction, and rig.[8] The sharpie represented by the plan is somewhat narrower and has more flare in the sides than indicated by the dimensions given by Kunhardt. The boatmen at New Haven were convinced that a narrow sharpie was faster than a wide one, and some preferred strongly flaring sides, though others thought the upright-sided sharpie was faster. These boatmen also believed that the shape of the bottom camber fore and aft was important, that the heel of the stem should not be immersed, and that the bottom should run aft in a straight line to about the fore end of the centerboard case and then fair in a long sweep into the run, which straightened out before it passed the after end of the waterline. Some racing sharpies had deeper sterns than tonging boats, a feature that produced a faster boat by reducing the amount of bottom camber.

The use of the sharpie began to spread to other areas almost immediately

after its appearance at New Haven. As early as 1855 sharpies of the

100-bushel class were being built on Long Island across the Sound from

New Haven and Bridgeport, and by 1857 there were two-masted, 150-bushel

sharpies in lower New York Harbor. Sloop-rigged sharpies 24 to 28 feet

long and retaining the characteristics of the New Haven sharpies in

construction and most of its basic design features, but with some

increase in proportion[Pg 145]ate beam, were extensively used in the small

oyster fisheries west of New Haven. There were also a few sloop-type

sharpies in the eastern Sound. In some areas this modification of the

sharpie eventually developed its own characteristics and became known as

the "flattie," a type that was popular on the north shore of Long

Island, on the Chesapeake Bay, and in Florida at Key West and Tampa.

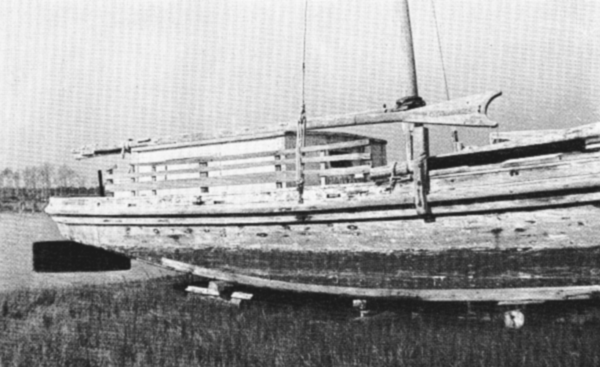

FIGURE 11.—North Carolina sharpie schooner hauled up for

painting.

FIGURE 11.—North Carolina sharpie schooner hauled up for

painting.

The sharpie's rapid spread in use can be accounted for by its low cost, light draft, speed, handiness under sail, graceful appearance, and rather astonishing seaworthiness. Since oyster tonging was never carried on in heavy weather, it was by chance rather than intent that the seaworthiness of this New Haven tonging boat was discovered. There is a case on record in which a tonging sharpie rescued the crew of a coasting schooner at Branford, Connecticut, during a severe gale, after other boats had proved unable to approach the wreck.

However, efforts to improve on the sharpie resulted in the construction of boats that had neither the beauty nor the other advantages of the original type. This was particularly true of sharpies built as yachts with large cabins and heavy rigs. Because the stability of the sharpie's shoal hull was limited, the added weight of high, long cabin trunks and attendant furniture reduced the boat's safety potential. Windage of the topside structures necessary on sharpie yachts also affected speed, particularly in sailing to windward. Hence, there was an immediate trend toward the addition of deadrise in the bottom of the yachts, a feature that sufficiently increased displacement and draft so that the superstructure and rig could be better carried. Because of its large cabin, the sharpie yacht when under sail was generally less workable than the fishing sharpie. Although it was harmful to the sailing of the boat, many of the sharpie yachts had markedly increased beam. The first sharpie yacht of any size was the Lucky, a half-model of which is in the Model Room of the New York Yacht Club. The Lucky, built in 1855 from a model by Robert Fish, was 51 feet long with a 13-foot beam; she drew 2 feet 10 inches with her centerboard raised. According to firsthand reports, she was a satisfactory cruiser, except that she was not very weatherly because her centerboard was too small.

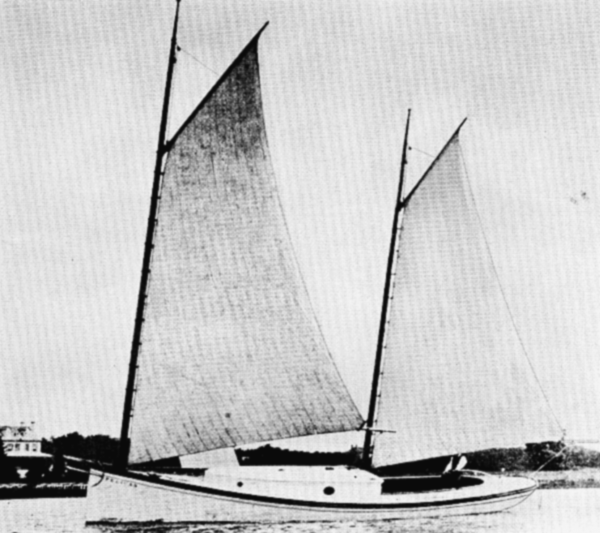

FIGURE 12.—North Carolina sharpie schooner converted to

yacht, 1937.

FIGURE 12.—North Carolina sharpie schooner converted to

yacht, 1937.

Kunhardt mentions the extraordinary sailing speed of some sharpies, as

does certain correspondence in Forest and Stream. A large sharpie was

reported to have run 11 nautical miles in 34 minutes, and a big sharpie

schooner is said to have averaged 16 knots in 3 consecutive hours of

sailing. Tonging sharpies with racing rigs were said to have sailed in

smooth water at speeds of 15 and 16 knots. Although such reports may be

exaggerations, there is no doubt that sharpies of the New Haven type

were among the fastest of American sailing fishing boats.

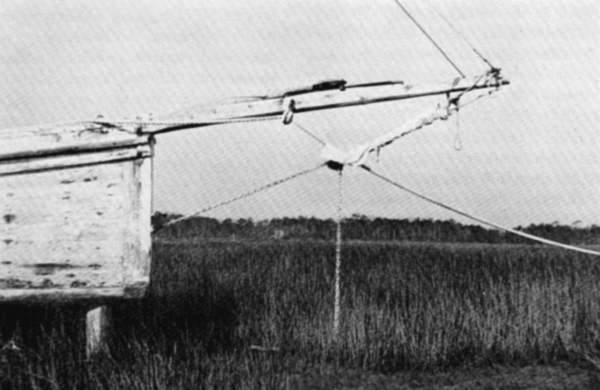

FIGURE 13.—Bow of North Carolina sharpie schooner

showing head rigging.

FIGURE 13.—Bow of North Carolina sharpie schooner

showing head rigging.

Sharpie builders in New Haven very early developed a "production"

method. In the initial stages of building, the hull was upside down.

First, the sides[Pg 147] were assembled and the planking and frames secured;

then the inner stem was built, and the sides nailed to it, after which

the bulkhead and a few rough temporary molds were made and put in place

and the boat's sides bent to the desired curve in plain view. For

bending the sides a "Spanish windlass" of rope or chain was used. The

chine pieces were inserted in notches in the molds inside the side

planking and fastened, then the keelson was made and placed in notches

in the molds and bulkhead along the centerline. Next, the upper and

lower stern frames were made and secured, and the stern staved

vertically. Plank extensions of the keelson were fitted, the bottom

laid, and the boat turned over. Sometimes the case was made and fitted

with the keelson structure, but sometimes this was not done until the

deck and inboard works were finished.

FIGURE 14.—The entrance of a North Carolina sharpie

schooner and details of her sharp lines and planking. Note scarphs in

plank.

FIGURE 14.—The entrance of a North Carolina sharpie

schooner and details of her sharp lines and planking. Note scarphs in

plank.

The son of Lester Rowe, a noted sharpie builder at New Haven, told me, in 1925, that it was not uncommon for his father and two helpers to build a sharpie, hull and spars, in 6 working days, and that one year his father and two helpers built 31 sharpies. This was at a time after power saws and planers had come into use, and the heavy cutting and finishing of timber was done at a mill, from patterns.

In spite of Barnegat Bay's extensive oyster beds and its proximity to

New Haven, the sharpie never became popular in that region, where a

small sailing scow known as the "garvey" was already in favor. The

garvey was punt-shaped, with its bow narrower than the stern; it had a

sledlike profile with moderately flaring sides and a half-deck; and it

was rigged with two spritsails, each with a moderate peak to the head

and the usual diagonal sprit.[9] The garvey was as fast and as well

suited to oyster tonging as the sharpie, if not so handsome; also, it

had an economic advantage over the New Haven boat because it was a

little cheaper to build and could carry the same load on[Pg 148] shorter

length. Probably it was the garvey's relative unattractiveness and the

fact that it was a "scow" that prevented it from competing with the

sharpie in areas outside of New Jersey.

FIGURE 15.—Midbody and stern of a North Carolina sharpie

schooner showing planking, molding, and other details.

FIGURE 15.—Midbody and stern of a North Carolina sharpie

schooner showing planking, molding, and other details.

The sharpie appeared on the Chesapeake Bay in the early 1870's, but she did not retain her New Haven characteristics very long. Prior to her appearance on the Bay, the oyster fishery there had used several boats, of which the log canoe appears to have been the most popular. Some flat-bottomed skiffs had also been used for tonging. There is a tradition that sometime in the early 1870's a New Haven sharpie named Frolic was found adrift on the Bay near Tangier Island. Some copies of the Frolic were made locally, and modifications were added later. This tradition is supported by certain circumstantial evidence.

Until 20 years ago Tangier Island skiffs certainly resembled the sharpie above the waterline, being long, rather narrow, straight-stem, round-stern, two-masted craft, although their bottoms were V-shaped rather than flat. The large number of boat types suitable for oyster fishery on the Bay probably prevented the adoption of the New Haven sharpie in a recognizable form. After the Civil War, however, a large sailing skiff did become popular in many parts of the Chesapeake. Boats of this type had a square stern, a curved stem in profile, a strong flare, a flat bottom, a sharply raking transom, and a center board of the "daggerboard" form. They were rigged with two leg-of-mutton sails. Sprits were used instead of booms, and there was sometimes a short bowsprit, carrying a jib. The rudder was outboard on a skeg. These skiffs ranged in length from about 18 feet to 28 feet. Those in the 24-to 28-foot range were half-decked; the smaller ones were entirely open.

In the late 1880's or early 1890's the V-bottomed hull became extremely popular on the Chesapeake, replacing the flat-bottom almost entirely, as at Tangier Island. Hence, very few flat-bottomed boats or their remains survive, although a few 18-foot skiffs are still in use.

Characteristics of the large flat-bottomed Chesapeake Bay skiff are

shown in figure 4. While it is possible that the narrow beam of this

skiff, the straightness of both ends of its bottom camber, and its rig

show some New Haven sharpie influence, these characteristics are so

similar to those of the flatiron skiff that it is doubtful that many of

the Bay sharpies had any real relation to the New Haven boats. As

indicated by figures 5 and 7, the Chesapeake flat-bottoms constituted a

distinct type of skiff. Except[Pg 149] for those skiffs used in the Tangier

Island area, it is not evident that the Bay skiffs were influenced by

the New Haven sharpie to any great degree, in form at least.

FIGURE 16.—Stern of a North Carolina sharpie schooner

showing planking, staving, molding, and balanced rudder.

FIGURE 16.—Stern of a North Carolina sharpie schooner

showing planking, staving, molding, and balanced rudder.

Schooner-rigged sharpies developed on Long Island Sound as early as 1870, and their hulls were only slightly modified versions of the New Haven hull in basic design and construction. These boats were, however, larger than New Haven sharpies, and a few were employed as oyster dredges. After a time it was found that sharpie construction proved weak in boats much over 50 feet. However, strong sharpie hulls of great length eventually were produced by edge-fastening the sides and by using more tie rods than were required by a smaller sharpie. Transverse tie rods set up with turnbuckles were first used on the New Haven sharpie, and they were retained on boats that were patterned after her in other areas. Because of this influence, such tie rods finally appeared on the large V-bottomed sailing craft on Chesapeake Bay.

The sharpie schooner seems to have been more popular on the Chesapeake Bay than on Long Island Sound. The rig alone appealed to Bay sailors, who were experienced with schooners. Of all the flat-bottomed skiffs employed on the Bay, only the schooner can be said to have retained much of the appearance of the Connecticut sharpies. Bay sharpie schooners often were fitted with wells and used as terrapin smacks (fig. 7). As a schooner, the sharpie was relatively small, usually being about 30 to 38 feet over-all.

Since the 1880's the magazine Forest and Stream and, later, magazines such as Outing, Rudder, and Yachting have been the media by which ideas concerning all kinds of watercraft from pleasure boats to work boats have been transmitted. By studying such periodicals, Chesapeake Bay boatbuilders managed to keep abreast of the progress in boat design being made in new yachts. In fact, it may have been because of articles in these publications that the daggerboard came to replace the pivoted centerboard in Chesapeake Bay skiffs and that the whole V-bottom design became popular so rapidly in the Bay area.

In the 1870's the heavily populated oyster beds of the North Carolina

Sounds began to be exploited. Following the Civil War that region had

become a depressed area with little boatbuilding industry. The small

boat predominating in the area was a modified yawl that had sprits for

mainsail and topsail, a jib set up to the stem head, a centerboard, and

waterways along the sides. This type of craft, known as the[Pg 150] "Albemarle

Sound boat" or "Croatan boat," had been developed in the vicinity of

Roanoke Island for the local shad fishery. Although it was seaworthy and

fast under sail, this boat was not particularly well suited for the

oyster fishery because of its high freeboard and lack of working deck

for tonging.

FIGURE 17.—Deck of a North Carolina sharpie schooner

showing U-shaped main hatch typical of sharpies used in the Carolina

Sounds.

FIGURE 17.—Deck of a North Carolina sharpie schooner

showing U-shaped main hatch typical of sharpies used in the Carolina

Sounds.

Because the oyster grounds in the Carolina Sounds were some distance from the market ports, boats larger than the standard 34-to 36-foot New Haven sharpie were desirable; and by 1881 the Carolina Sounds sharpie had begun to develop characteristics of its own. These large sharpies could be decked and, when necessary, fitted with a cabin. In all other respects the North Carolina sharpie closely resembled the New Haven boat. Some of the Carolina boats were square-sterned, but, as at New Haven, the round stern apparently was more popular.

Most Carolina sharpies were from 40 to 45 feet long. Some had a cramped forecastle under the foredeck, others had a cuddy or trunk cabin aft, and a few had trunk cabins forward and aft. Figure 6 is a drawing of a rigged model that was built to test the design before the construction of a full-sized boat was attempted.[10] The 1884 North Carolina sharpie shown in this plan has two small cuddies; it also has the U-shaped main hatch typical of the Carolina sharpie. It appears that the clubs shown at the ends of the sprits were very often used on the Carolina sharpies, but they were rarely used on the New Haven tongers except when the craft were rigged for racing. The Carolina Sounds sharpie shown under sail in figure 8 is from 42 to 45 feet long and has no cuddy.

The Carolina Sounds sharpies retained the excellent sailing qualities of

the New Haven type and were well finished. The two-sail, two-mast New

Haven rig was popular with tongers, but the schooner-rigged sharpie that

soon developed (figs. 9, 11-18) was preferred for dredging. It was

thought that a schooner rig allowed more adjustment of sail area and

thus would give better handling of the boat under all weather

condi[Pg 151]tions. This was important because oyster dredging could be carried

on in rough weather when tonging would be impractical. Like the Maryland

terrapin smack, the Carolina sharpie schooner adhered closely to New

Haven principles of design and construction. However, Carolina sharpie

schooners were larger than terrapin smacks, having an over-all length of

from 40 to 52 feet. These schooners remained in use well into the 20th

century and, in fact, did not go out of use entirely until about 1938.

In the 1920's and 1930's many such boats were converted to yachts. They

were fast under sail and very stiff, and with auxiliary engines they

were equally as fast and required a relatively small amount of power.

Large Carolina sharpie schooners often made long coasting voyages, such

as between New York and the West Indies.

FIGURE 18.—Deck of a North Carolina sharpie schooner

under sail showing pump box near rail and portion of afterhouse.

FIGURE 18.—Deck of a North Carolina sharpie schooner

under sail showing pump box near rail and portion of afterhouse.

The Carolina Sounds area was the last place in which the sharpie was

extensively employed. However, in 1876 the sharpie was introduced into

Florida by the late R. M. Munroe when he took to Biscayne Bay a sharpie

yacht that had been built for him by Brown of Tottenville, Staten

Island. Afterwards various types of modified sharpies were introduced in

Florida. On the Gulf Coast at Tampa two-masted[Pg 152] sharpies and sharpie

schooners were used to carry fish to market, but they had only very

faint resemblance to the original New Haven boat.

FIGURE 19.—Sharpie yacht Pelican built in 1885 for

Florida waters. She was a successful shoal-draft sailing cruiser. (Photo

courtesy Wirth Munroe.)

FIGURE 19.—Sharpie yacht Pelican built in 1885 for

Florida waters. She was a successful shoal-draft sailing cruiser. (Photo

courtesy Wirth Munroe.)

The sharpie also appeared in the Great Lakes area, but here its development seems to have been entirely independent of the New Haven type. It is possible that the Great Lakes sharpie devolved from the common flatiron skiff.

The sharpie yacht was introduced on Lake Champlain in the late 1870's by Rev. W. H. H. Murray, who wrote for Forest and Stream under the pen name of "Adirondack Murray." The hull of the Champlain sharpie retained most of the characteristics of the New Haven hull, but the Champlain boats were fitted with a wide variety of rigs, some highly experimental. A few commercial sharpies were built at Burlington, Vermont, for hauling produce on the lake, but most of the sharpies built there were yachts.

The use of the principles of flatiron skiff design in sharp-stern, or "double-ended," boats has been common. On the Chesapeake Bay a number of small, double-ended sailing skiffs, usually fitted with a centerboard and a single leg-of-mutton sail, were in use in the 1880's. It is doubtful, however, that these skiffs had any real relationship to the New Haven sharpie. They may have developed from the "three-plank" canoe[11] used on the Bay in colonial times.

The "cabin skiff," a double-ended, half-decked, trunk-cabin boat with a

long head and a cuddy forward, was also in use on the Bay in the 1880's.

This boat, which was rigged like a bugeye, had a bottom of planks that

were over 3 inches thick,[Pg 153] laid fore-and-aft, and edge-bolted. The

entire bottom was made on two blocks or "sleepers" placed near the ends.

The sides were bevelled, and heavy stones were placed amidships to give

a slight fore-and-aft camber to the bottom. The sides, washboards, and

end decks were then built, the stones removed, and the centerboard case

fitted. In spite of its slightly cambered flat bottom, this boat, though

truly a flatiron skiff in midsection form, had no real relation to the

New Haven sharpie; it probably owed its origin to the Chesapeake log

canoe, for which it was an inexpensive substitute.

FIGURE 20.—Florida sharpie yacht of about 1890.

FIGURE 20.—Florida sharpie yacht of about 1890.

R. M. Munroe built double-ended sharpies in Florida, and one of these was used to carry mail between Biscayne Bay and Palm Beach. Although Munroe's double-enders were certainly related to the New Haven sharpie, they were markedly modified and almost all were yachts.

A schooner-rigged, double-ended sharpie was used in the vicinity of San Juan Island, Washington, in the 1880's, but since the heels of the stem and stern posts were immersed it is very doubtful that this sharpie was related in any way to the New Haven boats.

The story of the New Haven sharpie presents an interesting case in the history of the development of small commercial boats in America. As has been shown, the New Haven sharpie took only about 40 years to reach a very efficient stage of development as a fishing sailboat. It was economical to build, well suited to its work, a fast sailer, and attractive in appearance.

When sailing vessels ceased to be used by the fishing industry, the sharpie was almost forgotten, but some slight evidence of its influence on construction remains. For instance, transverse tie rods are used in the large Chesapeake Bay "skipjacks," and Chesapeake motorboats still have round, vertically staved sterns, as do the "Hatteras boats" used on the Carolina Sounds. But the sharpie hull form has now almost completely disappeared in both areas, except in a few surviving flat-bottomed sailing skiffs.

Recently the flat-bottomed hull has come into use in small, outboard-powered commercial fishing skiffs, but, unfortunately, these boats usually are modeled after the primitive flatiron skiff and are short in length.

The New Haven sharpie proved that a long, narrow hull is most efficient

in a flat-bottomed boat, but no utilization has yet been made of its

design as the basis for the design of a modern fishing launch.

[1]Forest and Stream, January 23, 1879, vol. 11, no. 25, p. 504.

[2]Forest and Stream, January 30, 1879, vol. 11, no. 26, p. 500.

[3]Henry Hall, Special Agent, 10th U.S. Census, Report on the Shipbuilding Industry of the United States, Washington, 1880-1885, pp. 29-32.

[4]Howard I. Chapelle, American Small Sailing Craft, New York, 1951, pp. 100-133, figs. 38-48.

[5]C. P. Kunhardt, Small Yachts: Their Design and Construction, Exemplified by the Ruling Types of Modern Practice, New York, 1886 (rev. ed., 1891, pp. 287-298).

[6]Hall, op. cit.(footnote 3), pp. 30, 32.

[7]Kunhardt, op. cit.(footnote 5), pp. 225, 295.

[8]Full-scale examples of sharpies may be seen at the Mariners' Museum, Newport News, Virginia, and at the Mystic Marine Museum, Mystic, Connecticut.

[9] The foremast of the garvey was the taller and carried the larger

sail. At one time garveys had leeboards, but by 1850 they commonly had

centerboards and either a skeg aft with a rudder outboard or an

iron-stocked rudder, with the stock passing through the stern overhang

just foreward of the raking transom. The garvey was commonly 24 to 26

feet long with a beam on deck of 6 feet 4 inches to 6 feet 6 inches and

a bottom of 5 feet to 5 feet 3 inches.

[10] In building shoal draft sailing vessels, this practice was usually possible and often proved helpful. In the National Watercraft Collection at the United States National Museum there is a rigged model of a Piscataqua gundalow that was built for testing under sail before construction of the full-scale vessel.

[11] A primitive craft made of three wide planks, one of which formed the entire bottom.

Printer's errors have been corrected, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.