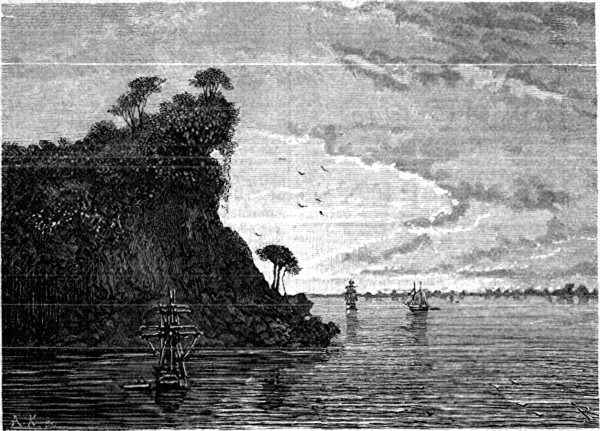

DIAMOND CLIFF: SUNSET.

DIAMOND CLIFF: SUNSET.

Title: Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Volume 15, No. 89, May, 1875

Author: Various

Release date: June 21, 2009 [eBook #29184]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Josephine Paolucci and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's notes: Minor typos have been corrected. Table of contents has been generated for HTML version.

UP THE PARANA AND IN PARAGUAY.

THREE FEATHERS.

CAMP-FIRE LYRICS.

OVERWORKED WOMEN.

SPRING JOY

HOW LADY LOUISA MOOR AMUSED HERSELF.

WALPURGIS NIGHT.

FRÉDÉRIC LEMAITRE.

THE SONG-WIND.

NORTHWARD TO HIGH ASIA.

BEHIND THEIR FANS.

A MODERN ART-WORKSHOP IN UMBRIA.

A STORY OF AMERICAN CHIVALRY.

WILLIAM, EARL OF SHELBURNE.

OUR MONTHLY GOSSIP.

LITERATURE OF THE DAY.

Books Received.

DIAMOND CLIFF: SUNSET.

DIAMOND CLIFF: SUNSET.

The lot of the foreigner in Buenos Ayres during the rainy season is not an enviable one. The Englishman who finds himself in that city when the rain falls for weeks at a time becomes a victim to the spleen, the American to "the blues," the Frenchman to ennui. The houses, built with a view mainly to protection against the torrid heats of summer, are not adapted to shelter their inmates from the dampness of winter, which penetrates through doors that do not fasten and windows that do not fit [Pg 522]as snugly as they should. The continual and monotonous drip of the rain, which ripples in streams or falls drop by drop on the pavement of the yards or of the street, is also highly depressing to the spirits when one is held an involuntary prisoner in the ground-floors of the houses, and must perforce listen to it for hours.

If, led by inclination or compelled by necessity, you go into the street, you find the space between the sidewalks transformed into a miniature river. In some of the streets the pavements are more than three feet high, and pedestrians walk on them as on the tow-path of a canal, passing from one side of the torrent to the other on small wooden crossings. The comfort that is derived elsewhere in inclement weather from fires may not be hoped for in Buenos Ayres, for the bed-rooms are rarely provided with fireplaces, and in cases where they do possess them the chimneys are liable to smoke dreadfully when the north-west wind sweeps over the city.

The natives, accustomed to these features of the rainy season in La Plata, look with indifference on the forlorn condition of the stranger within their gates, and the foreigner, thus left to struggle against the coalition of the elements with the thoughtless or selfish indifference of the native population, must resign himself with patience and resignation until the three months of watery affliction shall have passed away.

It was at a time when the reign of Pluvius was at its height, and Buenos Ayres daily wept blinding tears, as it were, from every roof and gable for its sins, that M. X——, the head of a commercial house in the city, put a most welcome question to one of the attachés of the establishment, M. Forgues, a Frenchman, who just then was suffering from the grievous burden of ennui.

"See here," he said: "I want somebody to go up into Paraguay to collect an outstanding debt. Are you the man for my purpose?"

M. Forgues readily accepted the commission, for as the head of the house spoke a vision passed through his mind of Paraguay with its old Jesuit missions, its mysterious and despotic dictators, and its legends of the terrible war waged by Lopez against Brazil, the Argentine Confederation and the Banda Oriental. And, moreover, the venture promised relief from the horrors of the rainy season in Buenos Ayres.

When Francisco Solano Lopez, late president of Paraguay, fell on the field on March 1, 1870, at the head of a few hundred followers, the survivors of that courageous army of sixty thousand men with which in 1865 he had begun his five years' struggle, he had left behind him a devastated country, a decimated people and an impoverished population. It is to this land, almost remote enough from the pathway of our modern civilization to partake of the mystery of an unknown interior; where Nature has lavished her beauties with open hand; where a brilliant vegetation alternates with noble forests, solitudes that have rarely echoed the footfall of civilized man, and vast plains dotted with palms—a country of mountainous reaches in which the jaguar roams at will, of great lagoons, the home of a primitive race dwelling for the most part in villages,—to this land it is that we shall follow M. Forgues on his journey of more than a thousand miles, and see with his eyes its life and scenery.

From Buenos Ayres the traveler, issuing from the Rio de la Plata, ascends the Parana by steamer to Asuncion, the capital of Paraguay; and on the morning after the conversation with his principal M. Forgues embarked on the Republica, a low-pressure steamboat furnished with a walking-beam, and similar in its architecture and equipments to the passenger steamers in use on the waters of the Northern and Middle States of the Union.

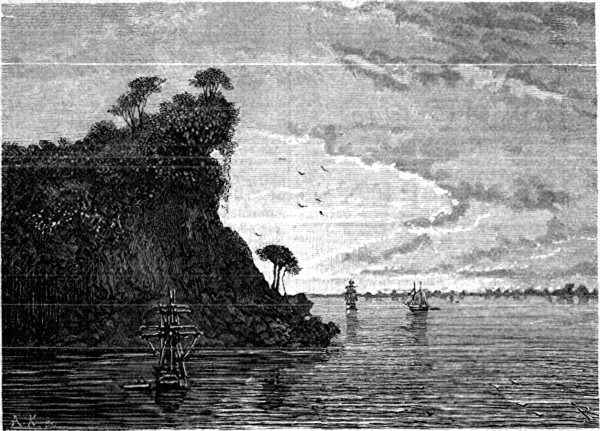

After steaming two hours the Republica reaches the vast delta of the Parana, skirting the Tigre Islands, a lovely group formed by the numerous winding mouths of the river. The month is August, and a charming effect is produced by the forests of palms, orange trees and wild peach trees, the latter rosy with blossoms, which cover the islands. The wild peach of the clingstone variety is almost the[Pg 523] only fruit of the province of Buenos Ayres, and when the season for gathering it comes, a multitude of boats from the city may be seen moored in the high grasses along the shores of the Tigre Islands, while the barqueros collect the peaches, which are free to whoever will pluck them, fill their boats and return to the capital to sell them.

DELTA OF THE PARANA.

DELTA OF THE PARANA.

TIGER ISLAND, MOUTH OF THE PARANA.

TIGER ISLAND, MOUTH OF THE PARANA.

The Republica ascends the river through the branch called the Parana de las Palmas, up which Sebastian Cabot sailed in 1525, when in a schooner of a hundred tons burden he penetrated to the heart of South America. It passes, to the left, a hamlet, Campana, the prominent feature of which is a handsome white building resembling a palazzo of Italy, and which, built on an elevation, dominates the other houses; Zarate, where are[Pg 525] situated a number of saladeros, or salting-places for the salting of the hides of the province; and finally the mouth of the Baradero River, a small stream which leads to a village of the same name, the home of a prosperous colony of Swiss settlers.

Higher up, on the right shore, lies the drowsy old town of San Pedro, founded in the middle of the seventeenth century, and which is chiefly noticeable as having been at a standstill since that period, although within the past three or four years it has begun to show signs of development, one of which is a project to cut a ship-canal across a narrow reach of sand which separates the lagoon on which the town is built from the river, so as to give passage to Transatlantic vessels.

At San Pedro the steamer emerges from the Parana de las Palmas and enters the main channel of the river. A notable locality a few leagues above San Pedro is the Obligado, where the Parana becomes so narrow that the channel lies within pistol-shot of the right bank. The Obligado is interesting in an historical point of view as having been the scene in 1845 of a fierce engagement wherein the English and French fleets ran the gauntlet of the Argentine batteries there, which attempted to prevent their passage. One of the English vessels, under a withering fire, cut a chain that barred the channel. A humorous sequel to this brilliant feat of arms is this, that since that occurrence every French sailor, and especially every deserter from the French merchant marine who goes to La Plata, boasts that he "assisted" at the affair. He will narrate all the details in the most bombastic manner to any pecuniarily prosperous fellow-countryman who will listen to him, and will then close with a proposition that he and his compatriot shall "take something." The payment for the score naturally falls to the lot of the listener or victim, and hence has arisen a saying among Frenchmen in La Plata: "Distrust the gentleman who was at the combat of the Obligado."

Twenty-four hours after leaving Buenos Ayres the steamer stops at Rosario, having previously passed the town of San Nicolas de los Arragos, with its ten thousand inhabitants, its picturesque cathedral flanked with a white tower on either side, its progressive tramways or horse-cars, and its reputation for furnishing an excellent article of hides, the province being celebrated for the quality of its cattle.

Rosario is the second port of the confederation. It stands a short distance away from the river on a barranca or cliff. Passengers on landing are conveyed in horse-cars to the town, which is laid out in handsome streets and built up with charming and comfortable houses. The barn-like church, of the "horrible Jesuit style," as M. Forgues calls it (the heavy style of architecture common to nearly all the church edifices of South America), is very ugly, and as to the "faithful élégantes" who worshiped in it, our traveler did not deem them as handsome as their sisters of Buenos Ayres. Much of Rosario's increasing prosperity is owing to the railroad which connects it with the interior town of Cordova to the west. This road also extends down the Parana to a point about half-way to Buenos Ayres. When completed to the latter city and to its western terminus, which will be at no distant day, Buenos Ayres, on the Atlantic, will be connected with Valparaiso, in Chili, on the Pacific. There is also a line of English steamers which ply directly between Rosario and the English ports.

At Rosario the Republica takes on passengers, coal and freight, and resumes her voyage. Above the city, the cliffs, increasing in height, attain an altitude of nearly one hundred and fifty feet. They are composed entirely of a hard brown earth having the appearance of pulverized chocolate; and the river, rushing between them, assumes a dirty, brownish hue for many miles. In their shadow, as the steamer passes, lie a Brazilian gunboat and two monitors of the same nationality: one of the latter is deeply dented in places where she was struck by Paraguayan cannon-balls.[Pg 526]

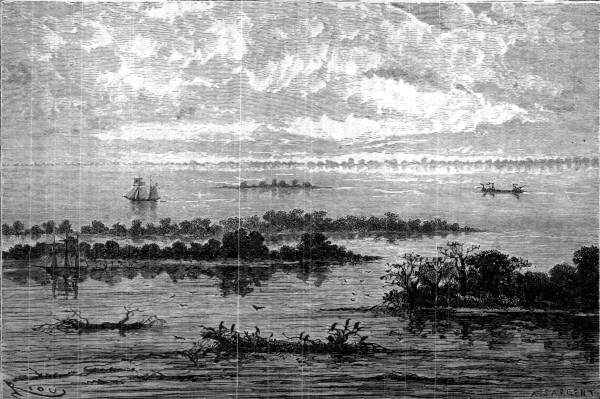

PUBLIC SQUARE IN PARANA.

PUBLIC SQUARE IN PARANA.

About twelve hours' distance from Rosario the Diamante, or Diamond Cliff, is reached. Here the cliffs that line the left bank culminate. They are especially interesting to the geologist because of their extraordinary richness in fossils of various kinds. Fragments of the megatherium and of the glyptodon have been found there, but the most important discovery of all was a very complete skeleton of the former animal—the most complete in existence, in fact—which now adorns the museum at Buenos Ayres. The village of Diamante, with a population of five or six hundred souls, is situated near by. Twenty hours later the Republica arrives at Parana, a handsome city, formerly the capital of the confederation. The removal of the seat of government to Buenos Ayres was a great blow to the prosperity of the old capital. Once the diplomatic corps had their residences there. The climate of the place is delicious, and under its balmy influence the orange tree flourishes in the open air and bears fruit of exquisite flavor. The country around Parana is very picturesque, and the town itself, though since it has ceased to be the Argentine capital it presents an appearance of emptiness, is very gay. Among its attractions are a theatre and a fine public square adorned with shade trees. The community has musical tastes, and nearly every second house contains a piano—a[Pg 527] fact of which the stranger strolling through the place is kept constantly aware. Many of the streets are paved and macadamized.

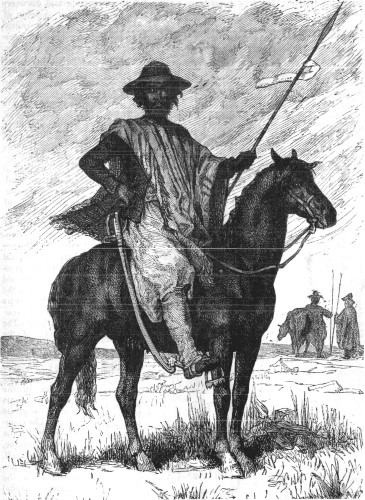

A BLANCO INSURGENT.

A BLANCO INSURGENT.

Parana is the chief city of the province of Entre Rios, the people of which are possessed of a fierce spirit of independence, and, like the Basques of Spain, claiming the right to administer their domestic affairs in their own way, they are often in insurrection against the central government at Buenos Ayres, which[Pg 528] resorts to force to check their "separatist" tendencies. Within four years two or three efforts at revolution have been made on the part of the people of Entre Rios under Lopez Jordan, their principal leader, General Mitre, and others. One year previous to the journey we are now describing our traveler had gone from Buenos Ayres to Parana on business. In consequence of a municipal election having gone in favor of the government candidates by a majority of thirty votes, a fresh insurrection had just broken out in the city, and when M. Forgues reached his destination he found the national troops in possession of Parana, which was closely besieged by the Blancos or "Whites," as the insurgents were called from their trappings, to distinguish them from the Colorados or "Reds," which was the name given to the Buenos Ayres party. On the occasion of this visit he had need to seek the insurgent camp in furtherance of his mission, which was to obtain possession of eight thousand hides that were within the insurgents' lines. He returned to Parana, after successfully conducting the negotiations, with a sketch of one of the mounted Blancos, a picturesque, stately fellow, with the proud bearing of a brigand, having enormous spurs on his heels, a white band around his hat, and armed with a lance and a long cavalry sword.

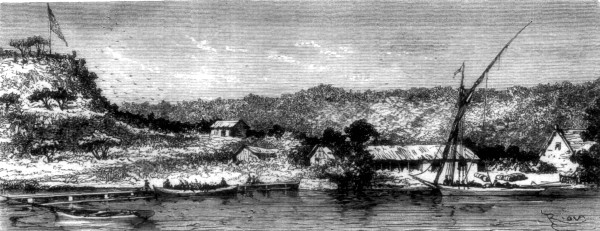

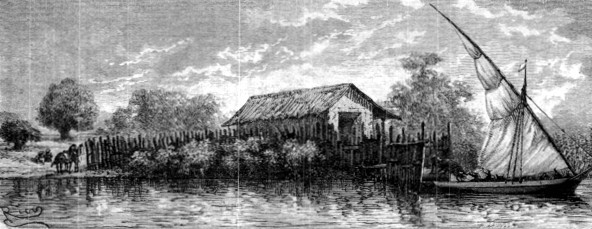

A SALADERO ON THE PARANA.

A SALADERO ON THE PARANA.

Immediately opposite Parana, on the other side of the river, which in this part is very wide, is the city of Santa Fé, the point of export for all the region occupied by the foreign agricultural colonies of the confederation—to wit, the Swiss, Piedmontese, Germans and Belgians. The chief industry in which these colonists are engaged is the cultivation of wheat, of which enormous quantities are raised and converted into flour on the spot, as there are several steam flour-mills in the district. The flour is shipped from Santa Fé and sold in Rosario or Buenos Ayres. These colonists number about thirteen thousand. Santa Fé is a remarkably indolent town—the[Pg 529] most indolent in the world, says M. Forgues. Its chief features are its great plaza, its church and the palace of the governor of Gran Chaco. Back of the country occupied by the colonists begins the land of the Chaco Indians. They enjoy the reputation of being savages, but as an example of the delicate line of demarkation in La Plata between the extreme of civilization and the extreme of savage life our traveler relates that riding thirty leagues to visit a tribe of wild Indians, he found the chief with a poncho of Manchester manufacture on his shoulders, a pair of gaiters from Latour, Rue Montorgueil, Paris, on his feet, and a hospitable glass of Hamburg gin in his hand.

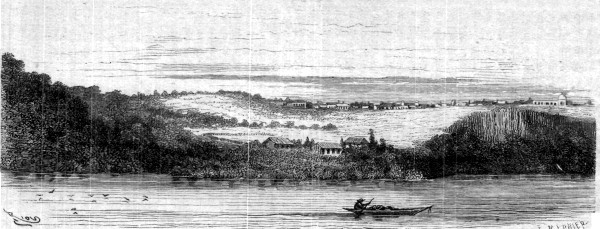

VIEW OF PARANA FROM THE RIVER.

VIEW OF PARANA FROM THE RIVER.

Leaving Parana, the steamer passes, at a short distance above the city, the saladero of Messrs. Carbo y Carril, a picturesque spot situated on a cliff. From this point a fine view is obtained of Parana in the distance, stretching along its high barranca, with its white houses and belfries in bold relief against the blue sky, and borrowing from the elevation on which it stands a delusively majestic aspect.

As the Republica ascends the river the cliffs continue to be the prevailing feature of the shore-scenery. A Brazilian passenger steamer, one of a line of steamers which ply between Cuyaba in the Brazilian province of Matto Grosso and Montevideo, is met descending the stream. This line, established by the government of Brazil to maintain communication between its central South American possessions and the large cities of the coast, receives an imperial subsidy of nine thousand francs a month. A saladero is passed, and then a village. The river is thick with trees with twisted roots and short branches, floating downward to the ocean. Then the appearance of the banks changes: the cliffs gradually slope to a level with the river, and vegetation begins to line the shore, first in the shape of bushes, next of undergrowth, and finally of lofty forest trees,[Pg 530] some of them dead, and with a wall of tangled foliage overhead.

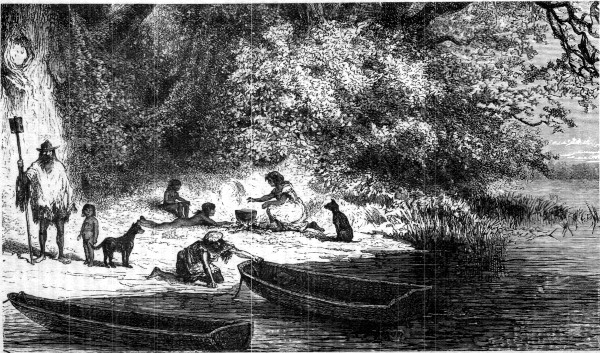

Passing Esquina, a hamlet at the mouth of the Rio Corrientes, vast volumes of smoke rising behind the trees on the right bank proclaim that the Indians of Gran Chaco are "burning a forest in order to roast a quarter of venison." Here the steamer's course lies among islands covered partly with undergrowth and partly with forests. In the shadow of the tall trees on one of the most lovely of these islands is seen from the deck a quaint, barefooted company consisting of two men, a woman and three small children, who have just stepped ashore from two boats made from the hollowed-out trunks of trees. Two dogs accompany them. The adults of the party are clothed in rags. These people are monteros, and are members of a tribe of gypsies who haunt the islands of the Parana. They live a life of lordly independence, subsisting as best they can, sleeping when fatigued wherever they may be when drowsiness overtakes them, eating whatever comes to hand, drinking the water of the river in the absence of anything stronger, and keeping themselves warm by firing a forest from time to time. At the moment the Republica hurries past they are preparing their evening meal, the material for which, a carpincho, a sort of aquatic hog, lies at their feet. The chief of the gypsy party stares at the steamer with bewildered eyes, and at the noise made by the paddles a great terror seizes on a colony of monkeys in the branches of the trees.

The town of La Goya, with a population of five thousand, is the next place of importance reached. A few miles above this point is a famous saladero, that of El Rincon de los Sotos (the "Fool's Corner"), which belongs to a fellow-countryman of M. Forgues, and which, after the saladero of Baron Liebig in Uruguay, is the most extensive in the valley of the Rio de la Plata. Here are slaughtered as many as fifteen hundred head of cattle a day. Nor far distant from it is the landing-place for the animals, a pretty spot which M. Forgues sketched en passant.

The Republica is approaching Corrientes, the last of the Argentine towns on the left bank of the Parana, and situated eighteen miles below the point at which the Paraguay unites with that stream. Now alligators appear, stretched lazily on the sand and basking in the sun, with their ugly black bodies resembling logs partly submerged. The river assumes a new aspect, widening into great sheets of water dotted with flat islands lying far apart, and in its lake-like proportions justifying the Guaranian meaning of its name—"like the sea." So far-reaching indeed are these expanses of water that when a brisk south-east wind rises large vessels in them roll and pitch as in the open bay. The belfries of Corrientes will loom before the eyes of the company on the Republica at ten o'clock the next morning, and in the mean time, and until the sun shall rise, the steamer is moored before a small island. In that balmy and odorous night myriads of insects cloistered in the leafy shades fill the air with murmurs and drowsy noises. Behind the dark foliage a swarm of fireflies illumines the gloom, until to the looker-on in the river the depths of the solitary island take to themselves the fantastic guise of a great city far away, with its gaslights twinkling merrily.

At Corrientes the Parana abruptly diverges to the east, marking the northern boundary of Argentine territory, and separating the latter from Paraguay. From the river the port presents a spectacle of groups of rocks of some beauty, and of palms and orange-trees growing close to the water's edge. Beyond the foliage are seen the belfries of several churches built after the prevailing fashion. Among them is visible also a handsome turret of Moorish architecture, which rears itself aloft with a charming effect. This building is the cabildo, or court-house, and dates from 1812. Near by is seen a white memorial pillar, built on the site of the cross that the first Spanish settlers planted in 1588. The population of Corrientes is about twenty thousand. From the country around are procured the best oranges grown in the confederation, and the city is the mart for the woods from the Paraguayan, Chaco and Corrientes forests which are exported for manufacturing purposes.[Pg 531]

GYPSIES OF THE ISLANDS IN THE PARANA.

GYPSIES OF THE ISLANDS IN THE PARANA.

The elbow formed by the junction of the Parana and the Paraguay is called by the natives Las Tres Bocas, or "The Three Mouths." From 1812 to 1865, under the rule of the dictators, this avenue of approach to Paraguay remained closed. But the fortunes of the last war opened it permanently, and the Republica quietly steams into the great water-highway that leads to Asuncion through the passes of the Cerrito. At the mouth of the river is the island of Cerrito, formerly the Paraguayan Gibraltar, and now the Gibraltar of the Brazilians, who maintain there a garrison and an arsenal for the equipment of their navy.

After passing the Cerrito the Paraguay winds in its course and becomes narrow—the width not exceeding twelve hundred feet—and of greater depth than the Parana. Hereabout and above are spots made memorable by the obstinate defence of the late President Lopez and the brave endurance of his people. On the right are the famous batteries of Curupaiti, where Lopez with thirty thousand Paraguayans and one hundred and fifty cannon resisted for eight months the attempts of the united Brazilian and Argentine forces to turn him out. But at last the condition of affairs became critical, and on a dark night he silently abandoned Curupaiti with his army, leaving his fires burning, wooden images of men on the ramparts, logs in the embrasures in lieu of cannon, and decamped to occupy a similar intrenched position at Humaita, six leagues above, where for five months longer he checked the advance of the allies. So adroitly was this change of position effected that the Brazilian commander was unaware of the abandonment of the place until four days after its desertion. To-day at Humaita a ruined belfry casts its melancholy shadow on the long-contested field of battle.

Leaving Humaita behind, the mouth of the Vermejo, a stream which tinges the Paraguay with the hue of its clay-colored waters, is reached and passed: then Villa del Pilar, a forlorn hamlet, where a few dejected inhabitants crouch in the shade of shattered houses. Next a magnificent forest of palms appears. In front the yellow sand of the shore is covered with alligators, which lie about in groups. From the boat M. Forgues fires at these, and a little later he tries his skill on a jaguar, which, however, with a fierce growl, scampers off, and is lost to sight in the mazes of the high grass beyond. These localities and Villa Oliva, which is next passed, are all on the left bank, the opposite side of the river being peopled only by the wandering Indians of Gran Chaco. A short distance above is the small and once prosperous town of Villeta, whence are shipped in season boatloads of oranges, but which at present is a mass of ruins that bear ample testimony to the excellent aim of the Brazilian gunners.

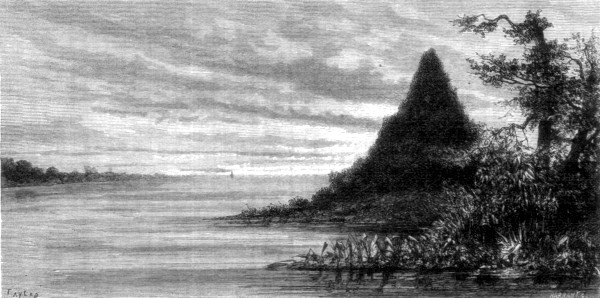

Just before a turn in the river reveals the presence of Asuncion the Republica steams by the Cerro de Lambare, a cone-shaped hill about three hundred and twenty feet high, covered with so dense a growth of bushes that no one has ever succeeded in climbing to its summit. The river-channel in its length between this elevation and Asuncion still contains remains of the obstructions which Lopez placed there to check the progress of the Brazilian fleet and protect the city. As the steamer rounds the bend the Paraguayan capital comes in sight. A prominent and historical object in the medley of houses is the high tower of Lopez's château, dominating the rest of the city, and now gilded with the rays of the setting sun. A portion of its top is missing, a shell having carried it away during the war. Two discharges of cannon from the deck of the Republica announce the arrival, and in due time the steamer, which draws too much water to approach the quay, is anchored two hundred yards from the shore, having happily concluded her voyage of a thousand miles, which has consumed nearly seven days.

The view from deck is a most picturesque one. In a little while a flotilla of small boats, headed by the armed tender of the port-captain, puts out from the[Pg 533] quay and swarms around the steamer. Some of the boats contain citizens who are expecting the arrival of friends, and in others are hucksters, who jabber and gesticulate in frantic recommendation of their fruits and small wares. Immediately in front is the custom-house with its colonnade of white pillars, resembling a cloister. To the left Lopez's palace rears its shattered tower, and on the right hand is the arsenal, which serves as the barracks for the three or four thousand troops composing the Brazilian army of occupation. Near it is the horse-car station, connected by the street-cars with the station of the Asuncion and Paraguari railroad, a line about twenty-five leagues in length. Carts drawn by horses move slowly to and fro on the quay. Here and there along the shore, with the look of skeletons about them, are frames of unfinished ships: one of them is an iron vessel which was in process of construction, under the orders of Lopez, at the breaking out of the war in 1865. The Brazilian conquerors have left these vessels in the condition in which they found them.

LANDING PLACE FOR CATTLE, PARANA RIVER.

LANDING PLACE FOR CATTLE, PARANA RIVER.

When the war supervened, Asuncion and all Paraguay, under the despotic but intelligent sway of Lopez, were moving rapidly in the path of progress. In fact, twelve years ago no country in La Plata was blessed with so flourishing and perfected a system of industry as Paraguay. But the war came, waged by the allies expressly to destroy for ever the dictatorial authority wielded by Lopez; Paraguay was invaded and overrun; and the fierce and destructive character of the contest has left shattered walls in the capital, and in the interior the blackened ruins of ranchos. These traces of the terrible conflict give a melancholy aspect to the city, and its future is further shadowed by the hopelessness of the people, who seem to have no heart to repair the damage done to the houses.[Pg 534]

THE HILL OF LAMBARE.

THE HILL OF LAMBARE.

In coming to Asuncion, M. Forgues had taken on himself a commission far more troublesome than that of collecting the money due to the commercial house with which he was connected; and this was to deliver into the hands of the French chargé d'affaires at Buenos Ayres, the comte A. de C——, who happened to be at the time in Asuncion, the despatch-bag of the legation, which had been consigned to his care by the French consul in the former city. Behold, then, our traveler, as, accompanied by the captain of the Republica, he sets foot on the quay, intent on relieving himself of his precious valise, the possession of which is doubly embarrassing because of its very preciousness. He has a hope that he may meet the chargé at the Progreso Club, whither he is going, but whether he is to be met or not, he does not dare to leave behind him the valise, which to him is a veritable Old Man of the Sea. Night has fallen when they leave the steamer. The dark, sandy streets are badly graded, and he stumbles repeatedly on the uneven brick pavements which line them, at every step anathematizing the valise, which is far from being a light burden. The club-house was the residence of Lopez before the allied armies occupied the city. From its seclusion he went forth to meet his death at Cerro Cora. In the[Pg 535] parlor is a large mirror with gilded mouldings, and the dining-room walls are hung with painted paper representing in vivid colors, and with much gilding and silvering, scenes from French history, in which musqueteers, courtiers and the cardinal de Richelieu figure. A large and notable company is present, among them many high civil functionaries, but the chargé d'affaires is not there. In the billiard-room the honorable minister of finance plays a game with the honorable minister of the interior. They are both of unpretending manners, polite and affable, and during the pauses of the game they call for and drink their beer in true democratic fashion. M. Forgues learns that his chargé lives two leagues out of town, and, hugging his exasperating valise—which, we may here remark, was delivered safely to the chargé next day—he returns in company with the captain to the steamer, where, seated on the deck, he listens with horror to the stories told by a citizen of divers murders committed in the town and vicinity, one of the victims, a French pioneer, having been slain lately at his quinta, or small farm, just on the other side of the river, by the fierce Indians of Gran Chaco, whose camp-fires, about six miles distant, even while they are conversing, light up one-fourth of the horizon in that direction.

M. Forgues, introduced to General Vedia, who commands the Argentine forces in Paraguay, is invited by that officer to go with him to Villa Occidental, a town situated a few miles above Asuncion on the river, and capital of the new province of Gran Chaco, claimed by the Argentine Confederation. He accepts. The voyage is made in a small Argentine gunboat, with its guard of thirty Argentine soldiers dressed in gray linen, with green facings to their coats, and armed with Minié rifles. This detachment is on its way to Villa Occidental to relieve the guard at that place, which has been on duty for eight days protecting the infant capital of Gran Chaco against the incursions of the Indians of the province. Around them are grouped a number of Paraguayan women, clad in the costume of the country—a chemise and a white rebozo—which gives them a certain statuesque appearance. The general and M. Forgues are received with military honors at Villa Occidental by the commandant of the place and his garrison of three soldiers. A walk of ten minutes brings them to the spot, a short distance out of the village, where twenty years ago was established a colony of Frenchmen who had been sent out from France by the late President Lopez at the time of the dictatorship of Carlos Antonio Lopez, his father. The elder Lopez, it appears, desired agriculturists from France, and the younger Lopez, who was then in that country, despatched to him two or three hundred bootblacks, organ-grinders, street vagabonds, etc. whom he had collected on the quays of Bordeaux and in the suburbs of Paris. Carlos Antonio was at first grieved to see the class of immigrants that had been forwarded as tillers of the soil, but he became furious when he discovered that his unwelcome colonists had brought with them certain dangerous ideas of liberty which threatened to excite a mutinous spirit among his docile Paraguayans. He therefore assembled them at a spot near Villa Occidental, and placed them under the control of the governor of the province of Gran Chaco, in spite of the protests of the French consul. Here they were treated with the utmost cruelty. They were bastinadoed and otherwise punished for the most trivial offences. Many died under these inflictions. Of the few survivors some endeavored to escape through the forests of Gran Chaco to Bolivia and Peru. Three were caught, brought back and tortured, while the others, of whom no tidings were ever received afterward, probably perished of hunger or were killed by the Indians or jaguars. All that now remains of this ill-starred enterprise is a few half-decayed palm-tree posts symmetrically planted in the ground on the site of the unfortunate colony of New Bordeaux.

Villa Occidental is at present merely a village of eight hundred or one thousand inhabitants. Its greatness, if it is ever to be great, lies in the future. General Vedia,[Pg 536] having ample room at his command for a metropolitan experiment, has laid it out in long avenues seventy-five feet wide, with a view to its future magnificence when it shall have become the outlet of the northern regions of the Argentine Confederation and the emporium of the Brazilian province of Matto Grosso.

A STREET IN ASCUNCION.

A STREET IN ASCUNCION.

At Villa Occidental, M. Forgues meets a fellow-countryman, who belongs to the class of adventurers who flourish in the wake of great wars. His name is Auriguau, and he was once a soldier in the Franco-Spanish free corps which fought against Lopez in the campaign of 1870. His head is filled with sublime ideas, and his pocket is empty. He has come to Villa Occidental to propose to General Vedia the formation of a military corps, of which he shall be chief, composed of his old companions-in-arms, to serve against the Indians of Gran Chaco. He explains his plan with much enthusiasm, and then begs our traveler to present him with his gun, his revolver, his money, his hat, and even his boots.

M. Forgues is of course General Vedia's guest for the night. As he is about to dismiss the soldier who has conducted him to his chamber, which is on the ground-floor of the house, an unexpected visitor[Pg 537] glides into the room through the open door. This visitor is a snake three feet long. The soldier kills him, turns him on his back, and calmly remarks that he is one of the most dangerous specimens of his kind in the neighborhood. M. Forgues's curiosity is aroused. "Are there many like this in the houses here?" he asks. "Sometimes yes, sometimes no," replies the soldier philosophically, retiring from the presence. M. Forgues goes to sleep to dream of a snake for a bedfellow, and to be bitten by mosquitoes of a peculiarly virulent kind through the cords of his hammock.

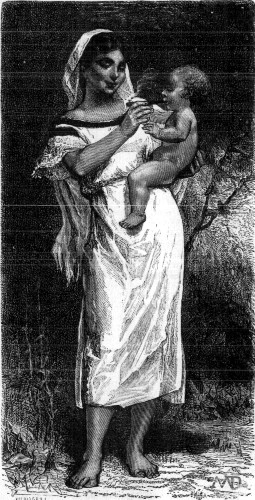

AN EARLY LESSON IN SMOKING.

AN EARLY LESSON IN SMOKING.

At early dawn our traveler is up and his toilet is made. Before the door silently file the women of the colony on their way to the bank of the river. Each bears on her head a large jug of red clay ornamented with fanciful designs, the clay resembling that of which the bowl of an Arab's pipe is made. When these jugs are empty the women carry them in a pretty way inclining to one side, as the French soldier wears his képi. This gives to their walk an air of ease and nonchalance that is extremely graceful. They are draped after a charming fashion in a piece of white cotton called the rebozo, which is scrupulously clean, and they walk one behind the other in bare feet and with elastic step. Their garment consists of[Pg 538] a white cotton chemise embroidered around the neck and at the top of the sleeves with black worsted. It is cut very low in the neck, leaving a part of the breast bare, and descends to a point below the knee. A cotton cord tied around the waist keeps the chemise to the figure, and serves as girdle and corset at the same time. The space between the top of the chemise and the belt is used as a receptacle for cigars, money, and generally for all the small objects that elsewhere people carry in their pockets. The rebozo is worn over the head and shoulders, with the ends thrown back over the left shoulder. As they thus pass in single file, the customary mode of walking with the Guaranian women, nothing can be more coquettish than the pose of the jugs on their heads. They resemble an ancient bas-relief. Some of them have admirable figures, and nearly all have fine teeth. Though the type of the race is not a handsome one, owing to the high cheek-bones and square chin, many individuals are pretty. Their large dark eyes are shaded with heavy eyebrows, and their hair is as black as the crow's wing, but very coarse, notwithstanding the constant attention which its owners devote to it. Add to this, and spoiling all, an immense cigar in each mouth, for the Paraguayan women all smoke incessantly. Even children of tender years smoke, and the only ones exempt from the habit are babes at the breast. Indeed, M. Forgues remembers to have seen a Guaranian mother, with her little one straddling her hip, endeavoring to quiet the child's cries by placing between its lips the half-chewed end of her cigar. Among the women of this class marriages are rare. Their principal characteristics are attachment to the companions whom they have chosen, a scrupulous cleanliness, great reserve in speaking, superstition, industry and intelligence.

The general awakes. Horses are brought bridled and saddled for a ride, and the two set out in the direction of the mouth of the Rio Confuso, about five miles distant from the village. The road crosses a vast plain shaded here and there with a few palms of small growth. After half an hour's ride they reach a saw-mill, the property of an eccentric Italian named Perucchino, who had served in his time as an officer of the Italian volunteers of Montevideo under Garibaldi, at the period of the latter's residence in South America. Perucchino receives them with evvivas, gestures, and with even more than the usual demonstrations of the Italian character, and invites them into his house, before which are planted three cannon mounted on a large piece of timber. His bed-room is an arsenal, supplied with enough old muskets, veterans of the war of independence, rusty swords and pikes, to arm fifteen men. He loves noise, and in proof thereof, after killing two chickens for breakfast with two separate discharges of a dangerous-looking double-barreled rifle—dangerous to him who fires it—he announces that the meal is ready with a discharge of one of the cannon at the door—a noisy proclamation which causes M. Forgues to jump in his seat. The breakfast, consisting of chicken and corn and rice omelettes, washed down with heavy Spanish wine, disappears as if by magic under the eager appetites of the guests. Perucchino has been dwelling in this solitude of Gran Chaco for three years with his wife, a Spanish woman. With two fellow-countrymen to assist him, he has worked indefatigably, and at the time of this visit his considerable property has greatly improved. In two years more, when his fields of corn, tobacco and sugar-cane shall begin to yield a return, the ex-beggar of Montevideo will be in the enjoyment of a yearly income of fifteen thousand francs.

At noon M. Forgues and the general return to Villa Occidental under a burning sun, and in the evening they embark for Asuncion on the gunboat, accompanied by the relieved garrison of thirty men. M. Forgues regretfully leaves this little colony, so peaceful and verdurous. As he is about to embark some one runs after him and overtakes him. It is Auriguau, who asks him for his traveling-bag and his pipe, and takes possession,[Pg 539] without asking, of his tobacco, promising him in return a present of an entire museum of curiosities, among which are enumerated tiger robes, dried butterflies and some enormous snakes, and in addition a complete collection of all the woods of Gran Chaco, the total approximate value of which is about forty thousand francs.

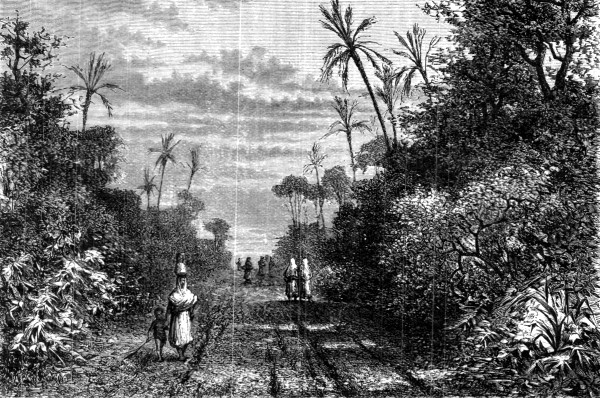

ROAD TO TRINIDAD.

ROAD TO TRINIDAD.

The return journey is along the Chaco[Pg 540] side of the Paraguay. Here and there on the sandbanks amid which the boat threads its way are sunk two or three hulls of vessels covered with a rich growth of vegetation. They represent so many incipient islands. It is amusing to observe the soldiers and their wives busily employed in extinguishing the burning cinders and sparks—small beginnings of conflagrations—which have been deposited in their hair and on their clothing and bundles from the wood-fed furnaces of the gunboat.

The scenery in the vicinity of Asuncion is very fine, and possesses a special feature of its own with the dark shadows of the trees falling on a reddish-yellow sand. Immense avenues lead out in a straight line from the city. They are from seventy to eighty feet wide, but the sand is so deep in them and in the streets that men and horses sink in it above the ankle. Since the war the people have had very few horses, and have been compelled to import them; and it very often happens that newly-arrived saddle and draught horses die from exhaustion consequent on their efforts to gallop in the streets and country roads. One of the most charming of these avenues leads to the church of the Trinidad in the outskirts of the town.

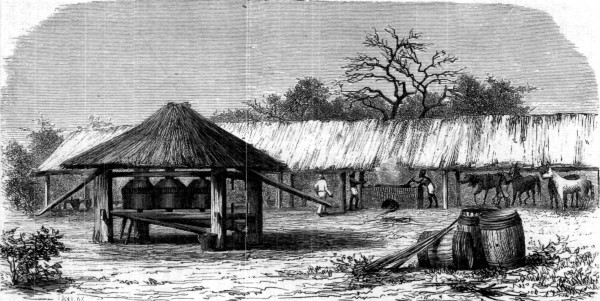

Sugar-cane grows to perfection in this part of Paraguay, but as the methods employed in the manufacture of sugar are of the most rudimentary kind, resulting in the loss of eighty per cent. of the juice the cane contains, and as the sugar is made chiefly by private individuals for their own use, and rarely reaches the market, this industry, which should be a great source of revenue to the country, languishes. The sugar used in Asuncion comes from Europe and Brazil. The cost of machinery probably has been the obstacle to the establishment of a sugar-house of sufficient importance to supply the people with all the sugar of home manufacture they may require. The cane when cut is ground between three large cylinders made of a hard wood—a process which, instead of extracting the juice from the cane, leaves two-thirds of it in the half-crushed stalk. The portion thus expressed flows through a sort of wooden trench into pails, which are emptied as fast as they become full into a large vat, under which a fire is constantly kept burning. In this receptacle it is boiled for a considerable time, but owing to the carelessness of those in charge of the vat about a third of it is spilled on the ground. What is left is reduced to a kind of sugary molasses, to which is given the name of "honey." Some of the cane-growers distill with rude alembics a sort of sweet liquor from the cane-juice, which is called caña. Another distillation is from the juice of oranges, and is called caña de naranja. In the manufacture of the latter birds of various kinds—ducks, paroquets, young chickens, etc.—are sometimes placed in the liquor to be distilled, and the curious mixture that results is known as caña de substancia, and is much affected by gourmets.

Life in Asuncion is remarkably monotonous. It is a long course of maté-drinking varied with meals, the inevitable siesta and cigars. The maté is the popular beverage of the country, as it is of nearly the whole of South America. It is a tea of less fragrance but more strength than the Chinese product, and is made of the yerba, the leaf of the Paraguayan holly, which grows in immense profusion in the Cordillera of Caaguazu in the interior. The Paraguayan women are active and industrious, but the men elevate the far niente into an institution. The people rise early to enjoy the freshness of the morning, but at noon they make up for their loss of sleep by indulging in a three hours' siesta in the heat of the day. A singular fact, however, regarding the climate is, that at Buenos Ayres, where the temperature is a third less heated than in Asuncion, the heat is more overpowering than in the latter city, and that one perspires far less in Asuncion than in the Argentine capital.

While in Asuncion, M. Forgues attended a Te Deum which was sung at the cathedral to celebrate the anniversary of the proclamation of Brazilian independence, and a ball given by the Brazilian general in the house that was formerly[Pg 541] the residence of the somewhat famous Madame Lynch, a star of the Parisian demi-monde whom the late President Lopez had brought with him from Paris and installed in Asuncion as his favorite. Each of these events was interesting in its way—the former as showing how completely Brazilian supremacy shadows Paraguayan authority even in the very capital of Paraguay, and the latter as offering our traveler a glimpse of Paraguayan "high life" under its most favorable auspices.

A SUGAR-HOUSE.

A SUGAR-HOUSE.

The cathedral is one of the masterpieces of M. Forgues's bête noire, the Jesuit style of architecture. On the occasion of the Te Deum the altar is brilliant with light. Silver plates cover it, as they do all its accessories. Behind it is a carved wainscoting painted red and green and gilded profusely, while in a niche is a small effigy of the Blessed Virgin. At the beginning of the service a curtain rises to the sound of music and exposes this niche to view. The Brazilian minister, M. d'Azambuja, is the "marquis of Carabas" of Asuncion, and hence, as the representative of the nation that conquered Paraguay, he enjoys his privileges, one of which, apparently, is to keep the ceremony waiting for half an hour, while the president of the republic, his cabinet[Pg 542] ministers, the foreign representatives and the officers of the army of occupation who are present twiddle their thumbs, the Paraguayan officials showing in their faces their sense of the Brazilian's want of respect. Finally the minister arrives in a coach-and-four. The vehicle is of the hackney-coach variety. The horses stop in the thick sand in the middle of the street, unable or unwilling to go farther, and the coachman in gold-lace livery jumps from his seat and opens the door of the coach, exhibiting as he does so, in consequence of the inopportune displacement of his coat-tails, a very undiplomatic spectacle in the way of soiled stockings. The minister, however, makes amends for the lackey's shortcomings, for he is brilliantly attired in white cassimere breeches and a marquis's coat with embroidery, while a three-cornered chapeau with white plumes adorns his head. As he descends from his carriage the guard presents arms, and a horrible noise ensues of two brass bands—one military and one marine—playing different tunes on every separate instrument in the hands of the performers, while the discharge of petards mingles with military commands. Amid all this tumult and under a broiling sun the Brazilian minister makes a majestic entrance into the cathedral, passing solemnly through the line of authorities to the place of honor.

The celebration of Brazil's independence opens with a salvo of petards at the door, after which follows a medley of trombones, flutes, triangles and big drums, the whole dominated by an exasperating tenor voice. With the exception of the president of the republic, his cabinet, who wear scarfs of the Paraguayan colors—blue, white and red—and the officiating priests, there is not a Paraguayan in the church. Lovers of noise and of the excitement of festivals though they be, the people thus protest mutely against a ceremony that exalts their conquerors and recalls their own powerless condition.

The ball given by the Brazilian general was, as before stated, at the house once occupied by Madame Lynch—Madame Elisa, as they call her in Paraguay—where that functionary resided. The best society of the capital, composed exclusively of the families of the higher officials, attended, and what was curious was that most of the women present in their ball-room attire, three years before, owing to the exigencies of war, had little more than a brief garment wherewith to protect themselves from the inclemencies of the weather. The dancing goes on in the parlor of the establishment and under the verandah which surrounds the courtyard. At the first glance, the parlor in its adornments presents the appearance of a salon of the Faubourg St. Germain, with silken hangings vivid in color on the walls, gilded stucco-work on the ceiling, and a brilliant carpet under foot. But on closer inspection all these splendors are seen to be merely a stage-decoration, for the effects—with the exception of the carpet—have been produced by some skillful wandering artist with his paintbrush and an adequate supply of gold-leaf. The illusion, however, is complete for a few minutes. The women—among whom are some handsome representatives of Paraguayan beauty—have wonderfully graceful manners. Their complexions are dark, their eyes large and black, and their hair of the color of ebony. The décolleté style prevails in the cut of the dresses, which are made simply, and generally present the combination of white and black. The dances are those of Europe, and as the women dance a smile parts their lips.

This is the bright side of the picture of the feminine element at the ball. The reverse of the medal is not so satisfactory, for at the door of entrance, seated on chairs or standing along the wall, are collected groups of old women with wrinkled faces and coarse gray hair negligently tucked on the tops of their heads with combs. These elders, rolled up, rather than wrapped, in shawls of various sombre hues, and who look on listlessly as if in a daze, are the mothers of the smiling dancers. It is dreadful, however, to observe their proceedings when refreshments are handed round, for suddenly a singular agitation is observable among them, their long thin arms shoot[Pg 543] from under their tightly-drawn shawls, they rush for the refreshments as they are carried past them, and swallow the liquids while stowing away supplemental cakes under their wrappings. Casting his eyes toward the centre of the room, where the young beauties are separating at the close of the dance, the observer notices that several of them are directing their steps away from the parlor to their retiring room. They have departed to smoke at their ease.

Reference has been made to the scantiness of the attire of the Paraguayan women at one period of the war. Some terrible facts are related in connection with this matter, showing the horrible desperation and sternness with which Lopez conducted his military operations, bringing untold woe on his own people in his savage resolve to retard at any cost the advance of the army of invasion. When the allies captured Humaita, Lopez, retreating, decided to convert the country lying in the enemy's front into a desert. He issued a proclamation ordering the entire population living south of Asuncion to retire with all their animals toward the interior, and to follow him into the cordillera, eighty leagues to the east of the city. This order applied to all classes without exception, the families of high dignitaries, ministers and superior officers being included as well as the humbler sort. The result was a terrified hegira of the people en masse, while behind them the Paraguayan rear-guard destroyed houses and whatever could afford shelter or subsistence to the enemy, leaving only bare fields where once had flourished prosperous estancias and peaceful villages. Terrible scenes ensued. Twenty-four hours' notice only was given to the people to leave their homes. Delinquents and laggards were sabred mercilessly or killed with lance-thrusts. This mode of massacre was preferred, as it was a saving of valuable powder and shot. Women and children were slaughtered in this way, as well as infirm old men. No provision had been made to feed the famishing multitude that sought the cordillera, and thousands of the homeless wretches died of starvation and exposure in the mountains, where all that the women and children could obtain in the way of food was oranges and roots. There were numerous instances of cannibalism among these starving people, and our traveler was shown a woman in Asuncion who had eaten a portion of her sister to allay the pangs of hunger.

The effect on the allies of this frightful course was to compel them to pay a fabulous price for provisions and for their transportation to the army. Another effect was that at times, in the heat of the pursuit of Lopez's forces, after an engagement the bodies of the soldiers who had been killed in the battle were left to rot where they fell, as there were no civilians to bury them. On one occasion, after a heavy skirmish, two or three hundred slain Argentines remained unburied, the army having marched forward in pursuit of the retreating Paraguayans. The horrors of this campaign were relieved by one prosaic fact, which in itself bridges the chasm between the terrible and the ridiculous: this was, that the allied troops were accompanied amid all these scenes of carnage by a poor Italian organ-grinder, carrying his organ on his back, who played during the halts in the march while the Brazilian soldiers danced to his music.

When the war ended with the death of Lopez at Cerro Cora, women, even of the richest and most influential families, returned to their homes nearly naked: the large majority made their reappearance in a still more forlorn plight. The population of the republic, which had numbered about one million three hundred thousand at the beginning of the conflict, had dwindled to two hundred thousand or two hundred and fifty thousand. These were mainly women and children, for the men were nearly all dead, and of the few male adults in the population the majority have immigrated to the country since the war. The national army, which under Lopez was sixty thousand strong, comprised at the time of M. Forgues's visit two hundred and fifty youths of fifteen or sixteen years of age, clad in[Pg 544] the cast-off uniform of the French mobiles of 1870 and 1871. Of the Paraguayan children made orphans by the war, hundreds now live in Argentine families, either as adopted children or as servants. They were picked up by the Argentine soldiers during the flight of their parents to the mountains, their mothers having perished of fatigue or hunger, and Lopez's horsemen having spared them through pity or indifference to continued slaughter.

The sequel of the resistance of Lopez surpasses in gloomy details almost any similar struggle recorded in history. It has already been shown how women and children died by thousands or survived to poverty and want. But to understand the melancholy story at its worst, one should visit the valley of the Aquidaban River, where Lopez fought his last fight, or follow the line of his army's march from its camp at Panadero to the encampment at Cerro Cora, where he perished miserably. A traveler in that part of Paraguay—not M. Forgues, but Keith Johnston, the geographer—who visited these localities in the summer and autumn of 1874, says that the march of the army in its final retreat can still be traced by the heaps of human bones, with rusty swords or guns or weather-stained saddles lying beside them, under every little shade-giving tree. These skeletons he saw everywhere at very short intervals. Cerro Cora is described as a splendid amphitheatre surrounded by hills, with precipitous sides of red sandstone, and crowned with dark forests. Here and there amid the undulations are grassy knolls flanked by palm trees, and in one of these Lopez, driven to desperation, pitched his tent with a handful of followers. Madame Lynch, his children and his brother were with him. The single pass that led to this hiding-place was guarded with cannon, but the Brazilian horsemen, strangely enough, entered the retreat unperceived and surprised its occupants. Exactly how Lopez died is a matter of dispute in Paraguay. There are those in that country who revere his memory, and their story of his death represents him as issuing from his tent at the approach of the enemy and valiantly engaging them single-handed, while he bade his few adherents seek safety in flight. According to this account, he fell gloriously after slaying many Brazilians, refusing quarter and declaring his devotion to his country with his dying breath. The generally accepted report, however, is that he made a fruitless endeavor to escape from his encampment, and, overtaken by a Brazilian horseman, died in a matter-of-fact way from a lance-thrust. His grave is in that wild and lonely valley. At first a wooden cross marked the spot where he lies, but this has disappeared, and a bush, one of many that grow around, is pointed out as growing above it.

Even at this day, though more than four years have elapsed since the enactment of that tragedy, the scene remains as the Brazilians left it. The wrecks of the camp lie thickly on every side—bones of men, broken weapons, ammunition and the débris of gun-carriages, baggage-carts and boxes. This region is the heart of the country occupied by the Cangua Indians, a peaceable tribe who speak the Guarani language, without the admixture of Spanish words which prevails in the language as spoken in the more civilized parts of Paraguay. They rarely leave their forest homes except to seek a market for their wax, which they exchange for tobacco and other commodities. Their complexion is a dark brown, and the men, who usually go armed with bows and iron-tipped lances, wear a splinter of a substance like amber, about two inches in length, run through a hole in their under lips. In the almost inaccessible country of these Indians is situated the great cascade of the Panama River, known as the Gran Salto de la Guayra. This Paraguayan Niagara is the object of a superstitious reverence on the part of the Indians, who deem it the gateway to the infernal regions, and hence fear to approach it. The waters fall into a deep gorge with a roaring sound which may be heard twelve miles away, while splendid rainbows are generated in the clouds of spray that rise from the depths.

When they heard that Wenna was coming down the road they left Mr. Roscorla alone: lovers like to have their meetings and partings unobserved.

She went into the room, pale and yet firm: there was even a sense of gladness in her heart that now she must know the worst. What would he say? How would he receive her? She knew that she was at his mercy.

Well, Mr. Roscorla at this moment was angry enough, for he had been deceived and trifled with in his absence; but he was also anxious, and his anxiety caused him to conceal his anger. He came forward to her with quite a pleasant look on his face: he kissed her and said, "Why, now, Wenna, how frightened you seem! Did you think I was going to scold you? No, no, no! I hope there is no necessity for that. I am not unreasonable, or over-exacting, as a younger man might be: I can make allowances. Of course I can't say I liked what you told me when I first heard of it; but then I reasoned with myself: I thought of your lonely position, of the natural liking a girl has for the attentions of a young man, of the possibility of any one going thoughtlessly wrong. And really I see no great harm done. A passing fancy—that is all."

"Oh, I hope that is so!" she cried suddenly with a pathetic earnestness of appeal. "It is so good of you, so generous of you to speak like that!" For the first time she ventured to raise her eyes to his face. They were full of gratitude.

Mr. Roscorla complimented himself on his knowledge of women: a younger man would have flown into a fury. "Oh dear, yes! Wenna," he said lightly, "I suppose all girls have their fancies stray a little bit from time to time; but is there any harm done? None whatever. There is nothing like marriage to fix the affections, as I hope you will discover ere long—the sooner the better, indeed. Now we will dismiss all those unpleasant matters we have been writing about."

"Then you do forgive me? You are not really angry with me?" she said; and then, finding a welcome assurance in his face, she gratefully took his hand and touched it with her lips.

This little act of graceful submission quite conquered Mr. Roscorla, and definitely removed all lingering traces of anger from his heart. He was no longer acting clemency when he said, with a slight blush on his forehead, "You know, Wenna, I have not been free from blame, either. That letter—it was merely a piece of thoughtless anger; but still it was very kind of you to consider it canceled and withdrawn when I asked you. Well, I was in a bad temper at that time. You cannot look at things so philosophically when you are far away from home: you feel yourself so helpless, and you think you are being unfairly—However, not another word. Come, let us talk of all your affairs, and all the work you have done since I left."

It was a natural invitation, and yet it revealed in a moment the hollowness of the apparent reconciliation between them. What chance of mutual confidence could there be between these two? He asked Wenna if she had been busy in his absence; and the thought immediately occurred to him that she had had at least sufficient leisure to go walking about with young Trelyon. He asked her about the sewing club, and she stumbled into the admission that Mr. Trelyon had presented that association with six sewing-machines. Always Trelyon, always the recurrence of that uneasy consciousness of past events which divided these two as completely as the Atlantic had done! It was a strange meeting after that long absence.

"It is a curious thing," he said rather[Pg 546] desperately, "how marriage makes a husband and wife sure of each other. Anxiety is all over then. We have near us, out in Jamaica, several men whose wives and families are here in England, and they accept their exile there as an ordinary commercial necessity. But then they put their whole minds into their work, for they know that when they return to England they will find their wives and families just as they left them. Of course, in the majority of cases the married men there have taken their wives out with them. Do you fear a long sea-voyage, Wenna?"

"I don't know," she said rather startled.

"You ought to be a good sailor, you know."

She said nothing to that: she was looking down, dreading what was coming.

"I am sure you must be a good sailor. I have heard of many of your boating adventures. Weren't you rather fond, some years ago, of going out at night with the Lundy pilots?"

"I have never gone a long voyage in a large vessel," Wenna said rather faintly.

"But if there was any reasonable object to be gained an ordinary sea-voyage would not frighten you?"

"Perhaps not."

"And they have really very good steamers going to the West Indies."

"Oh, indeed!"

"First rate! You get a most comfortable cabin."

"I thought you rather—in your description of it—in your first letter—"

"Oh," said he, hurriedly and lightly (for he had been claiming sympathy on account of the discomfort of his voyage out), "perhaps I made a little too much of that. Besides, I did not make a proper choice in time. One gains experience in such matters. Now, if you were going out to Jamaica, I should see that you had every comfort."

"But you don't wish me to go out to Jamaica?" she said, almost retreating from him.

"Well," said he with a smile, for his only object at present was to familiarize her with the idea, "I don't particularly wish it unless the project seems a good one to you. You see, Wenna, I find that my stay there must be longer than I expected. When I went out at first the intention of my partners and myself was that I should merely be on the spot to help our manager by agreeing to his accounts at the moment, and undertaking a lot of work of that sort, which otherwise would have consumed time in correspondence. I was merely to see the whole thing well started, and then return. But now I find that my superintendence may be needed there for a long while. Just when everything promises so well I should not like to imperil all our chances simply for a year or two."

"Oh no, of course not," Wenna said: she had no objection to his remaining in Jamaica for a year or two longer than he had intended.

"That being so," he continued, "it occurred to me that perhaps you might consent to our marriage before I leave England again, and that, indeed, you might even make up your mind to try a trip to Jamaica. Of course we should have considerable spells of holiday if you thought it was worth while coming home for a short time. I assure you you would find the place delightful—far more delightful than anything I told you in my letters, for I'm not very good at describing things. And there is a fair amount of society."

He did not prefer the request in an impassioned manner. On the contrary, he merely felt that he was satisfying himself by carrying out an intention he had formed on his voyage home. If, he had said to himself, Wenna and he became friends, he would at least suggest to her that she might put an end to all further suspense and anxiety by at once marrying him and accompanying him to Jamaica.

"What do you say?" he said with a friendly smile. "Or have I frightened you too much? Well, let us drop the subject altogether for the present."

Wenna breathed again.

"Yes," said he good-naturedly, "you can think over it. In the mean time do not harass yourself about that or anything[Pg 547] else. You know I have come home to spend a holiday."

"And won't you come and see the others?" said Wenna, rising with a glad look of relief on her face.

"Oh yes, if you like," he said; and then he stopped short, and an angry gleam shot into his eyes: "Wenna, who gave you that ring?"

"Oh, Mabyn did," was the frank reply; but all the same Wenna blushed hotly, for that matter of the emerald ring had not been touched upon.

"Mabyn did?" he repeated, somewhat suspiciously. "She must have been in a generous mood."

"When you know Mabyn as well as I do, you will find out that she always is," said Miss Wenna quite cheerfully: she was indeed in the best of spirits to find that this dreaded interview had not been so very frightful after all, and that she had done no mortal injury to one who had placed his happiness in her hands.

When Mr. Roscorla, some time after, set out to walk by himself up to Basset Cottage, whither his luggage had been sent before him, he felt a little tired. He was not accustomed to violent emotions, and that morning he had gone through a good deal. His anger and anxiety had for long been fighting for mastery, and both had reached their climax that morning. On the one hand, he wished to avenge himself for the insult paid him, and to show that he was not to be trifled with; on the other hand, his anxiety lest he should be unable to make up matters with Wenna led him to put an unusual value upon her. What was the result, now that he had definitely won her back to himself? What was the sentiment that followed on these jarring emotions of the morning?

To tell the truth, a little disappointment. Wenna was not looking her best when she entered the room: even now he remembered that the pale face rather shocked him. She was more insignificant—perhaps it is the best word—than he had expected. Now that he had got back the prize which he thought he had lost, it did not seem to him, after all, to be so wonderful.

And in this mood he went up and walked into the pretty little cottage which had once been his home. "What!" he said to himself, looking in amazement at the small, old-fashioned parlor, and at the still smaller study filled with books, "is it possible that I ever proposed to myself to live and die in a hole like this?—my only companion a cantankerous old fool of a woman, my only occupation reading the newspapers, my only society the good folks of the inn?"

He thanked God he had escaped. His knocking about the world for a bit had opened up his mind. The possibility of his having in time a handsome income had let in upon him many new and daring ambitions.

His housekeeper, having expressed her grief that she had just posted some letters to him, not knowing that he was returning to England, brought in a number of small passbooks and a large sheet of blue paper.

"If yü baint too tired, zor, vor to look over the accounts, 'tis all theear but the pultry that Mr.—"

"Good Heavens, Mrs. Cornish!" said he, "do you think I am going to look over a lot of grocers' bills?"

Mrs. Cornish not only hinted in very plain language that her master had been at one time particular enough about grocers' bills and all other bills, however trifling, but further proceeded to give him a full and minute account of the various incidental expenses to which she had been put through young Penny Luke having broken a window by flinging a stone from the road; through the cat having knocked down the best tea-pot; through the pig having got out of its stye, gone mad, and smashed a cucumber-frame; and so forth and so forth. In desperation Mr. Roscorla got up, put on his hat and went outside, leaving her at once astonished and indignant by his want of interest in what at one time had been his only care.

Was this, then, the place in which he had chosen to spend the rest of his life, without change, without movement, without interest? It seemed to him at the moment a living tomb. There was[Pg 548] not a human being within sight. Far away out there lay the gray-blue sea—a plain without a speck on it. The great black crags at the mouth of the harbor were voiceless and sterile: could anything have been more bleak than the bare uplands on which the pale sun of an English October was shining? The quiet crushed him: there was not a nigger near to swear at, nor could he, at the impulse of a moment, get on horseback and ride over to the busy and interesting and picturesque scene supplied by his faithful coolies at work.

What was he to do on this very first day in England, for example? Unpack his luggage, in which were some curiosities he had brought home for Wenna?—there was too much trouble in that. Walk about the garden and smoke a pipe, as had been his wont?—he had got emancipated from these delights of dotage. Attack his grocers' bills?—he swore by all his gods that he would have nothing to do with the price of candles and cheese, now or at any future time. The return of the exile to his native land had already produced a feeling of deep disappointment: when he married, he said to himself, he would take very good care not to sink into an oyster-like life in Eglosilyan.

About a couple of hours after, however, he was reminded that Eglosilyan had its small measure of society by the receipt of a letter from Mrs. Trelyon, who said she had just heard of his arrival, and hastened to ask him whether he would dine at the Hall, not next evening, but the following one, to meet two old friends of his, General and Lady Weekes, who were there on a brief visit.

"And I have written to ask Miss Rosewarne," Mrs. Trelyon continued, "to spare us the same evening, so that we hope to have you both. Perhaps you will kindly add your entreaties to mine."

The friendly intention of this post-script was evident, and yet it did not seem to please Mr. Roscorla. This Sir Percy Weekes had been a friend of his father's, and when the younger Roscorla was a young man about town, Lady Weekes had been very kind to him, and had nearly got him married once or twice. There was a great contrast between those days and these. He hoped the old general would not be tempted to come and visit him at Basset Cottage.

"Oh, Wenna," said he carelessly to her next morning, "Mrs. Trelyon told me she had asked you to go up there to-morrow evening."

"Yes," Wenna said, looking rather uncomfortable. Then she added quickly, "Would it displease you if I did not go? I ought to be at a children's party at Mr. Trewhella's."

This was precisely what Mr. Roscorla wanted; but he said, "You must not be shy, Wenna. However, please yourself: you need have no fear of vexing me. But I must go, for the Weekeses are old friends of mine."

"They stayed at the inn two or three days in May last," said Wenna innocently. "They came here by chance, and found Mrs. Trelyon from home."

Mr. Roscorla seemed startled. "Oh!" said he. "Did they—did they—ask for me?"

"Yes, I believe they did," Wenna said.

"Then you told them," said Mr. Roscorla with a pleasant smile—"you told them, of course, why you were the best person in the world to give them information about me?"

"Oh dear, no!" said Wenna, blushing hotly: "they spoke to Jennifer."

Mr. Roscorla felt himself rebuked. It was George Rosewarne's express wish that his daughters should not be approached by strangers visiting the inn as if they were officially connected with the place: Mr. Roscorla should have remembered that inquiries would be made of a servant.

But, as it happened, Sir Percy and his wife had really made the acquaintance of both Wenna and Mabyn on their chance visit to Eglosilyan; and it was of these two girls they were speaking when Mr. Roscorla was announced in Mrs. Trelyon's drawing-room the following evening. The thin, wiry, white-moustached old man, who had wonderfully bright eyes and a great vivacity of spirits for a veteran of seventy-four, was[Pg 549] standing in front of the fire, and declaring to everybody that two such well-accomplished, smart, talkative and lady-like young women he had never met with in his life: "What did you say the name was, my dear Mrs. Trelyon? Rosewarne, eh?—Rosewarne? A good old Cornish name—as good as yours, Roscorla. So they're called Rosewarne? Gad! if her ladyship wants to appoint a successor, I'm willing to let her choice fall on one of those two girls."

Her ladyship, a dark and silent old woman of eighty, did not like, in the first place, to be called her ladyship, and did not relish, either, having her death talked of as a joke.

"Roscorla, now—Roscorla, there's a good chance for you, eh?" continued the old general. "We never could get you married, you know—wild young dog! Don't you know the girls?"

"Oh yes, Sir Percy," Mr. Roscorla said with no great good-will: then he turned to the fire and began to warm his hands.

There was a tall young gentleman standing there who in former days would have been delighted to cry out on such an occasion, "Why, Roscorla's going to marry one of 'em!" He remained silent now.

He was very silent, too, throughout the evening, and almost anxiously civil toward Mr. Roscorla. He paid great attention when the latter was describing to the company at table the beauties of West Indian scenery, the delights of West Indian life, the change that had come over the prospects of Jamaica since the introduction of coolie labor, and the fashion in which the rich merchants of Cuba were setting about getting plantations there for the growth of tobacco. Mr. Roscorla spoke with the air of a man who now knew what the world was. When the old general asked him if he were coming back to live in Eglosilyan after he had become a millionaire, he laughed, and said that one's coffin came soon enough without one's rushing to meet it. No: when he came back to England finally, he would live in London; and had Sir Percy still that old walled-in house in Brompton?

Sir Percy paid less heed to these descriptions of Jamaica than Harry Trelyon did, for his next neighbor was old Mrs. Trelyon, and these two venerable flirts were talking of old acquaintances and old times at Bath and Cheltenham, and of the celebrated beauties, wits and murderers of other days, in a manner which her silent ladyship did not at all seem to approve. The general was bringing out all his old-fashioned gallantry—compliments, easy phrases in French, polite attentions: his companion began to use her fan with a coquettish grace, and was vastly pleased when a reference was made to her celebrated flight to Gretna Green.

"Ah, Sir Percy," she said, "the men were men in those days, and the women women, I promise you: no beating about the bush, but the fair word given and the fair word taken; and then a broken head for whoever should interfere—father, uncle or brother, no matter who; and you know our family, Sir Percy, our family were among the worst—"

"I tell you what, madam," said the general, hotly, "your family had among 'em the handsomest women in the west of England; and the handsomest men, too, by Gad! Do you remember Jane Swanhope—the Fair Maid of Somerset they used to call her—that married the fellow living down Yeovil way who broke his neck in a steeplechase?"

"Do I remember her?" said the old lady. "She was one of my bridemaids when they took me up to London to get married properly after I came back. She was my cousin on the mother's side, but they were connected with the Trelyons too. And do you remember old John Trelyon of Polkerris? and did you ever see a man straighter in the back than he was at seventy-one, when he married his second wife? That was at Exeter, I think. But there, now, you don't find such men and women in these times; and do you know the reason of that, Sir Percy? I'll tell you: it's the doctors. The doctors can keep all the sickly ones alive now: before it was only the strong ones that lived. Dear, dear me! when I hear some of those London women talk, it is nothing but a catalogue of illnesses and diseases.[Pg 550] No wonder they should say in church, 'There is no health in us:' every one of them has something the matter, even the young girls, poor things! and pretty mothers they're likely to make! They're a misery to themselves; they'll bring miserable things into the world; and all because the doctors have become so clever in pulling sickly people through. That's my opinion, Sir Percy. The doctors are responsible for five-sixths of all the suffering you hear of in families, either through illness or the losing of one's friends and relatives."

"Upon my word, madam," the general protested, "you use the doctor badly. He is blamed if he kills people, and he is blamed if he keeps them alive. What is he to do?"

"Do? He can't help saving the sickly ones now," the old lady admitted, "for relatives will have it done, and they know he can do it; but it's a great misfortune, Sir Percy, that's what it is, to have all these sickly creatures growing up to intermarry into the good old families that used to be famous for their comeliness and strength. There was a man—yes, I remember him well—that came from Devonshire: he was a man of good family too, and they made such a noise about his wrestling. Said I to myself, Wrestling is not a fit amusement for gentlemen, but if this man comes up to our country, there's one or other of the Trelyons will try his mettle. And well I remember saying to my eldest son George—you remember when he was a young man, Sir Percy, no older than his own son there?—'George,' I said, 'if this Mr. So-and-so comes into these parts, mind you have nothing to do with him, for wrestling is not fit for gentlemen.' 'All right, mother,' said he, but he laughed, and I knew what the laugh meant. My dear Sir Percy, I tell you the man hadn't a chance: I heard of it all afterward. George caught him up before he could begin any of his tricks and flung him on to the hedge; and there were a dozen more in our family who could have done it, I'll be bound."