Title: Harper's Young People, March 9, 1880

Author: Various

Release date: March 25, 2009 [eBook #28404]

Most recently updated: January 4, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire

| Vol. I.—No. 19. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | Price Four Cents. |

| Tuesday, March 9, 1880. | Copyright, 1880, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

P.M. steam-ship Arizona sails this day at 4.30 p.m. for China and the East, viâ Suez Canal. Freight received until 4 p.m. Hands wanted.

"I guess that's what I want," muttered a boy, who was comparing the printed slip in his hand with the above notice, conspicuously displayed from the yard of a huge ocean steamer alongside one of the North River piers at New York.[Pg 234]

Not a very heroic figure, certainly, this young volunteer in the battle of life: tired, seemingly, by the way in which he dragged his feet; cold, evidently, for he shivered every now and then, well wrapped up as he was; hungry, probably, for he had looked very wistfully around him as he passed through the busy, well-lighted market, where many a merry group were laughing and joking over their purchase of the morrow's Christmas dinner. But with all this, there was something in his firm mouth and clear bright eye which showed that, as the Western farmer said, on seeing Washington's portrait, "You wouldn't git that man to leave 'fore he's ready."

Picking up the bag and bundle which he had laid down for a moment, our hero entered the wharf house.

"Clear the way there!"

"Look out ahead!"

"Stand o' one side, will yer?"

"Now, sir, hurry up—boat's jist a-goin!"

"Arrah, now, kape yer umbrelly out o' me ribs, can't ye? Sure I'm not fat enough for the spit yet!'

"Hallo, bub! it's death by the law to walk into the river without a license. Guess you want to keep farther off the edge o' the pier."

The boy's head seemed to reel with his sudden plunge into all this bustle and uproar, to which even that of the crowded streets outside was as nothing. Men were rushing hither and thither, as if their lives depended on it, with tools, coils of rope, bundles of clothing, and trucks of belated freight. Dockmen, sailors, stevedores, porters, hackmen, outward-bound passengers, and visitors coming ashore again after taking leave of their friends, jostled each other; and all this, seen under the fitful lamp-light, with the great black waste of the shadowy river behind it, seemed like the whirl of a troubled dream.

And the farther he went, the more did the confusion increase. Here stood a portly gray-beard shouting and storming over the loss of his purse, which he presently found safe in his inner pocket; there a timid old lady in spectacles was vainly screaming after a burly porter who was carrying off her trunk in the wrong direction; an unlucky dog, trodden on in the press, was yelling; and an enormously fat man, having in his hurry jammed his carpet-bag between two other men even fatter than himself, was roaring to them to move aside, while they in their turn were asking fiercely what he meant by "pushing in where he wasn't wanted."

Suddenly the clang of a bell pierced this Babel of mingled noises, while a hoarse voice shouted, "All aboard that's going! landsmen ashore!"

The boy sprang forward, flew across the gang-plank just as it began to move, and leaped on deck with such energy as to run his head full butt into the chest of a passing sailor, nearly knocking him down.

"Now, then, where are yer a-shovin' to?" growled the aggrieved tar, in gruff English accents. "If yer thinks yer 'ead was only made to ram into other folks' insides, it's my b'lief yer ought to ha' been born a cannon-ball."

But the lad had flown past, and darting through a hatchway, reached the upper deck, where a group of sailors were gathered round a cannon. On its breech an officer had spread a paper, which a big good-natured Connaught man was awkwardly endeavoring to sign. After several floundering attempts with his huge hairy right hand, he suddenly shifted the pen to his left.

"Are you left-handed, my man?" asked the officer.

"Faith, my mother used to say I was whiniver she gev me annything to do," answered Paddy, with a grin; "but this is my right hand, properly spaking, ounly it's got on the left side by mistake. 'Twas my ould uncle Dan (rest his sowl!) taught me that thrick. 'Dinnis, me bhoy,' he'd be always sayin', 'ye should aiven l'arn to clip yer finger-nails wid the left hand, for fear ye'd some day lose the right.'"

This "bull" drew a shout of laughter from all who heard it, and the officer, turning his head to conceal a smile, caught sight of our hero.

"Hallo! another landsman! Boatswain, hold that gang-plank a moment, or we'll be taking this youngster to sea with us."

"That's just what I want," cried the boy, vehemently. "Will you take me, sir?"

"Run away from home, of course," muttered the officer. "That's what comes of reading Robinson Crusoe—they all do it. Well, my lad, as I see it's too late to put you ashore now, what do you want to ship as? Ever at sea before?"

"No, sir; but I'll take any place you like to give me."

"Sign here, then."

And down went the name of "Frank Austin," under the printed heading of "Working Passenger." The officer went off with the paper, the sailors dispersed, and Frank was left alone.

Gradually the countless lights of New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City sank behind, as the vessel neared the great gulf of darkness beyond the Narrows. Tompkins Light, Fort Lafayette, Sandy Hook, slipped by one by one. The bar was crossed, the light-ship passed, and now no sound broke the dreary silence but the rush of the steamer through the dark waters, with the "Highland Lights" watching her like two steadfast eyes.

Of what was the lonely boy thinking as he stood there on the threshold of his first voyage? Did he picture to himself, swimming, through a hail of Dutch and English cannon-shot with the dispatch that turned the battle, the round black head of a little cabin-boy who was one day to be Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovel? Did he see a vast dreary ice-field outspread beneath the cold blue arctic sky, and midway across it the huge ungainly figure of a polar bear, held at bay with the butt of an empty musket by a young middy whose name was Horatio Nelson? Was it the low sandy shores of Egypt that he saw, reddened by the flames of a huge three-decker, aboard of which the boy Casabianca

"stood on the burning deck,

Whence all but him had fled"?

Or were his visions of an English "reefer" being thrashed on his own ship by a young American prisoner, who was thereafter to write his name in history as "Salamander" Farragut? Far from it. Frank's thoughts were busy with the home he had left; and amid the cold and darkness, its cozy fireside and bright circle of happy faces rose before him more distinctly than ever.

"Wonder if they've missed me yet? The boys'll be going out to the coasting hill presently to shout for me: and sister Kate (dear little pet!), she'll be wondering why brother Frankie don't come back to finish her sled as he promised. And what distress they'll all be in till they get my first letter! and—"

"Hallo, youngster! skulking already! Come out o' that, and go for'ard, where you belong."

"I didn't mean to skulk, sir," said Frank, startled from his day-dream by this rough salutation.

"What? answering back, are ye? None o' yer slack. Go for'ard and get to work—smart, now!"

Frank obeyed, wondering whether this could really be the pleasant officer of a few hours before. Down in the dark depths below him figures were flitting about under the dim lamp-light, sorting cargo and "setting things straight," as well as the rolling of the ship would let them; and our hero, wishing to be of some use, volunteered to help a grimy fireman in rolling up a hose-pipe.

But he soon repented his zeal. The hard casing bruised his unaccustomed hands terribly, and it really seemed as if the work would never end. It ended, however, too soon for him; for the pipe suddenly parted at the joint,[Pg 235] and splash came a jet of ice-cold water in poor Frank's face, drenching him from head to foot, and nearly knocking the breath out of his body.

"Why didn't you let go, then?" growled the ungrateful fireman, coolly disappearing through a dark doorway, hose and all, while Frank, wet and shivering, crawled away to the engine-room. Its warmth and brightness tempted him to enter and sit down in a corner; but he was hardly settled there when a man in a glazed cap roughly ordered him out again.

Off went the unlucky boy once more, with certain thoughts of his own as to the "pleasures" of a sea life, which made Gulliver and Sindbad the Sailor appear not quite so reliable as before. He dived into the "tween-decks" and sank down on a coil of rope, fairly tired out. But in another moment he was stirred up again by a hearty shake, and the gleam of a lantern in his eyes, while a hoarse though not unkindly voice said, "Come, lad, you're only in the way here; go below and turn in."

Frank could not help thinking that it was time to turn in, after being so often turned out. Down he went, and found himself in a close, ill-lighted, stifling place (where hardly anything could be seen, and a great deal too much smelled) lined with what seemed like monster chests of drawers, with a man in each drawer, while others were swinging in their hammocks. He crept into one of the bare wooden bunks, drew the musty blanket over him, and, taking his bundle for a pillow, was asleep in a moment, despite the loud snoring of some of his companions, and the half-tipsy shouting and quarrelling of the rest.

A fairy lived in a lily bell—

Ring, sing, columbine!

In frosts she stole a wood-snail's shell,

Till soft the sun should shine;

And spring-time comes again, my dear,

And spring-time comes again,

With rattling showers, and wakened flowers,

And bristling blades of grain.

And, oh! the lily bell was sweet—

Ring, swing, columbine!

But the snail shell pinched her little feet,

And suns were slow to shine.

It's long till spring-time comes, my dear,

Till spring-time comes again:

The year delays its smiling days,

And snow-drifts heap the plain.

The fairy caught a butterfly—

Swing, cling, columbine!

The last that dared to float and fly

When pale the sun did shine;

For spring is slow to come, my dear,

Is slow to come again,

And far away doth summer play,

Beyond the roaring main.

She mounted on her painted steed—

Ring, cling, columbine!

And well he served that fairy's need,

And hot the sun did shine.

The spring she followed fast, my dear,

She followed it amain;

Where blossoms throng the whole year long

She found the spring again.

Oh, fairy sweet! come back once more—

Ring, swing, columbine!

When grass is green on hill and shore,

And summer sunbeams shine.

What if the spring is late, my dear,

And comes with dropping rain?

When roses blow and rivers flow,

Come back to us again.

Music affects animals differently. Some rejoice, and are evidently happy when listening to it, while others show unmistakable dislike to the sound.

For some years my father lived in an old Hall in the neighborhood of one of our large towns, and there I saw the influence of music upon many animals. There was a beautiful horse, the pride and delight of us all, and like many others, he disliked being caught. One very hot summer day I was sitting at work in the garden, when old Willy the gardener appeared, streaming with perspiration.

"What is the matter, Willy?"

"Matter enough, miss. There's that Robert, the uncanny beast; he won't be caught, all I can do or say. I've give him corn, and one of the best pears off the tree; but he's too deep for me—he snatched the pear, kicked up his heels, and off he is, laughing at me, at the bottom of the meadow."

"Well, Willy, what can I do? He won't let me catch him, you know."

"Ay, but, miss, if you will only just go in and begin a toon on the peanner, cook says he will come up to the fence and hearken to you, for he is always a-doing that; and maybe I can slip behind and cotch him."

I went in at once, not expecting my stratagem to succeed. But in a few minutes the saucy creature was standing quietly listening while I played "Scots, wha hae wi' Wallace bled." The halter was soon round his neck, and he went away to be harnessed, quite happy and contented.

There was a great peculiarity about his taste for music. He never would stay to listen to a plaintive song. I soon observed this. If I played "Scots, wha hae," he would listen, well pleased. If I changed the measure and expression, playing the same air plaintively, he would toss his head and walk away, as if to say, "That is not my sort of music." Changing to something martial, he would return and listen to me.

In this respect he entirely differed from a beautiful cow we had. She had an awful temper. She never would go with the other cows at milking-time. She liked the cook, and, when not too busy, cook would manage Miss Nancy. When the cook milked her, it was always close to the fence, near the drawing-room. If I were playing, she would stand perfectly still, yielding her milk without any trouble, and would remain until I ceased. As long as I played plaintive music—the "Land o' the Leal," "Home, Sweet Home," "Robin Adair," any sweet, tender air—she seemed entranced. I have tried her, and changed to martial music, whereupon she invariably walked away.

"Professor," asked May, "are there more worlds with people on them like this one of ours?"

"That is a hard question," said he. "For many ages it was believed that there could be only one. More recently, when astronomers learned by the aid of their telescopes the countless number of the heavenly bodies, it began to be doubted whether such an immense creation could be destitute of intelligent creatures like man; and it was argued that most likely the Almighty had supplied the heavenly bodies with inhabitants, but had for some good reason thought best not to reveal the fact to us, perhaps because our attention might be too much drawn away from the truths that He wished us particularly to remember. At last, however, men of science, continuing their researches, seem to be settling back in the first opinion."

"Why is that?" asked Joe.

"Because they find reasons for thinking that our earth has had human beings on it only a very little while in[Pg 236] comparison with its own existence. And if this world was millions of years without man, then, of course, any or all the heavenly bodies may still be without any such creature on them."

"Is there no better reason than that?" asked Joe.

"Yes, there is considerable evidence that the bodies nearest to us can not be inhabited by any creatures at all like man. On the moon, for instance, there is no air to breathe and no water to drink. And without air and water there can be no grass, trees, or plants of any kind, and no food for any animal. And besides starving, all creatures that we know of would immediately freeze to death; for the moon is excessively cold. The nights are about thirty times as long as ours, and allow each portion of its surface to get so cold that nothing could live."

"How did the moon get so cold?" asked Joe. "What became of the heat?"

"It went off into the surrounding space, which is all very cold. Empty space does not get warmed by the sun, whose heat seems chiefly to lodge in solid bodies and dense fluids."

"But some of the planets are larger than the moon, are they not?" asked Joe.

"Yes, Jupiter, for instance, is very much larger than the moon and the earth; and Professor Proctor tells us it will take Jupiter millions of years to become as cool as the earth, while the moon was as cool as the earth millions of years ago. Here is a picture of the planet; but its surface is changing so constantly, that it seldom appears the same on two nights in succession. Jupiter at present is wrapped in enormous volumes of thin cloud that rises up from a melted and boiling mass in the centre. Professor Newcomb supposes that there is only a comparatively small core of liquid, the greater part of the planet being made up of seething vapor. So you see it would be about as difficult to live on Jupiter as in a steam-boiler, or a caldron of molten lead. Since last summer a great red spot has been noticed on the surface of the planet, which has attracted much attention. Some think it is an immense opening, large enough for our earth to be dropped through."

"Are the other planets such dreadful places?" asked May.

"Saturn seems to be in about the same condition as Jupiter. Mars is thought to be solid, and to have land, water, and air. It has also two brilliant white spots on opposite sides, which are supposed to be vast fields of ice and snow. But the water seems to be disappearing; and the time when the planet could be inhabited is thought to be long gone by."

"Where does the water go?" asked Joe.

"Probably it sinks into the cracks or fissures which form in the crust of the planet when it begins to shrivel up with the cold."

"Then it must be like a great frozen grave-yard," said May. "But is there no other planet that is pleasanter to think about?"

"The one that seems on the whole to be most like our own is Venus, and so Professor Proctor calls it our sister planet. It is so close to the sun that it is hidden most of the time, being only seen for a while before sunrise, and at other times a while after sunset. In the one case it is called the morning, and in the other the evening star. Also there is Mercury, still nearer the sun, and hidden almost all the time."

"Then," said May, "there seems to be no way of knowing anything about there being people like us in other worlds; and the more we look into it, the more uncertain we become."

"That is about the way the case stands," said the Professor. "But if science continues to make as rapid progress as it has lately done, we may hope that it will yet throw more light on the question."

"How many planets are there?" asked Joe.

"Until quite recent times there were supposed to be only the five we have mentioned. Since the beginning of the present century about two hundred little planets, called asteroids, have been discovered between the orbits, or paths, of Mars and Jupiter. Then there are Uranus and Neptune, very far off from the sun and from us, so much so that the latter was mistaken for a fixed star."

"Professor," said May, "you mentioned the moon as being near to us. Can you explain to us how its distance is measured, so that we can understand it?"

"And then, Professor," said Jack, "I would like to know what parallax means."

"There," said Gus, "is another big word of Jack's—pallylacks, knickknacks, gimcracks, slapjacks!"

"Hush, you goose."

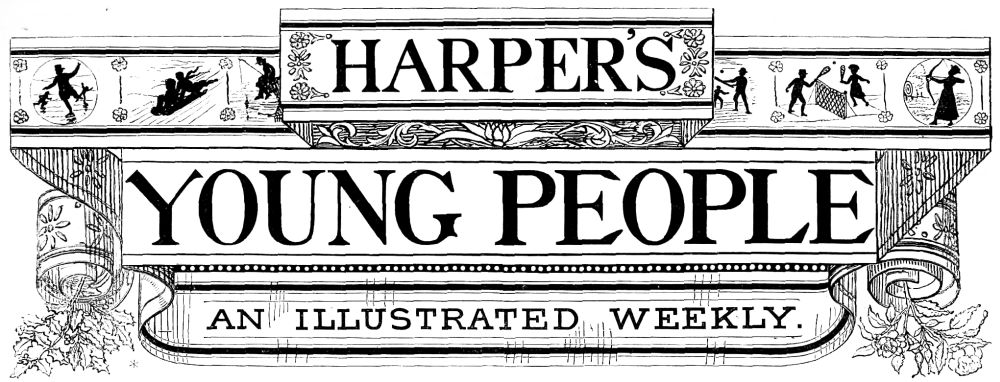

"I think," said the Professor, "I can answer May's and Jack's questions both at once, as they are very closely connected. Suppose that at night, when you look down the street, you see two gas lamps, one much farther off than the other. Then if you go across the street, the nearer lamp will seem to move in the opposite way from what you did. Thus, in the diagram, when you are at A, the nearer lamp is on the right of the other, and when you go over to B and look at it, it is on the left. This change in direction is called parallax. Now we can imagine the nearer one of the lights to be the moon, and that an observatory, or tower with a telescope in it, is located at A, from which the direction of the moon is carefully noted at six o'clock in the morning. Then by six in the evening the earth, spinning round on its axis, will have carried the observatory about 8000 miles away from A, and placed it at, say, B. If the moon's direction be again noted, it is very easy to calculate her distance by a branch of mathematics called trigonometry, which Jack, I have no doubt, has already studied."

THAT NAUGHTY, NAUGHTY BOY.

THAT NAUGHTY, NAUGHTY BOY.Just after the raising of the siege of Fort Stanwix, in the Mohawk Valley, the neighborhood continued to be infested with prowling bands of Indians.

Captain Gregg and a companion were out shooting one day, and were just preparing to return to the fort, when two shots were fired in quick succession, and Gregg saw his comrade fall, while he himself felt a wound in his side which so weakened him that he speedily fell.

Two Indians at the same time sprang out of the bushes, and rushed toward him. Gregg saw that his only hope was to feign death, and succeeded in lying perfectly still while the Indians tore off his scalp.

As soon as they had gone, he endeavored to reach his companion, but had no sooner got to his feet than he fell again. A second effort succeeded no better, but the third time he managed to reach the spot where his comrade lay, only to find him lifeless. He rested his head upon the bloody body, and the position afforded him some relief.

But the comfort of this position was destroyed by a small dog, which had accompanied him on his expedition, manifesting his sympathy by whining, yelping, and leaping around his master. He endeavored to force him away, but his efforts were in vain until he exclaimed, "If you wish so much to help me, go and call some one to my relief."

To his surprise, the animal immediately bounded off at his utmost speed.

He made his way to where three men were fishing, a mile from the scene of the tragedy, and as he came up to them began to whine and cry, and endeavored, by bounding into the woods and returning again and again, to induce them to follow him.

These actions of the dog convinced the men that there was some unusual cause, and they resolved to follow him.

They proceeded for some distance, but finding nothing, and darkness setting in, they became alarmed, and started to return. The dog now became almost frantic, and catching hold of their coats with his teeth, strove to force them to follow him.

The men were astonished at this pertinacity, and finally concluded to go with him a little further, and presently came to where Gregg was lying, still alive. They buried his companion, and carried the captain to the fort. Strange as it may seem, the wounds of Gregg, severe as they were, healed in time, and he recovered his perfect health.

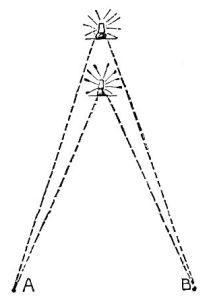

SHINNY ON THE ICE.

SHINNY ON THE ICE.

"Just like so many sheep!"

This was Will Brooks's exclamation, as he waited, with his elder brother Charlie, at the Northern Railroad station, in Paris. And truth to tell, the passengers were driven about and distributed somewhat after the manner of flocks, for, having purchased their tickets, they were obliged to pass along a corridor, opening into which were medium-sized waiting-rooms, separated from one another only by low partitions, and labelled, so to speak, as first, second, and third class. Here they were compelled to wait until five or ten minutes before the train was to leave, during which interval everybody endeavored to obtain the place nearest the door, so as to be sure of a choice of seats in the cars. Will and his brother had succeeded in getting pretty near the knob, where they were nearly suffocated with bad air, and much bruised by the satchels and umbrellas of their fellow-travellers.

"Now, Will, be ready," said Charlie, as a man was seen to approach with a key in his hand.

"All right; America to the front!" returned his patriotic brother; and at the same moment the doors were flung open, and in his nasal French tones the guard sang out, "Pour Liege, Aix-la-Chapelle, et Cologne!"

With a rush as of the sudden breaking away of a long pent-up mountain stream, the crowds surged forth from their "pens," and ran frantically up and down the long platform in search of the carriages for which they were respectively booked. The first-class compartment which Will and his brother had selected was speedily occupied by the six others required to fill it, their companions consisting of a gentleman and his wife, an old lady and a little boy, and two young men, evidently all French. Everybody had got nicely settled, the luggage was arranged in the racks overhead, and the train was just about to start, when a lady mounted to the doorway, with a little girl in one hand, and a bag, basket, and umbrella in the other. With a great volume of French she endeavored to thrust the child into the compartment, but was forced to desist from the attempt in deference to the remonstrances of the majority of those who already occupied it.

"C'est complet! c'est complet!" was the cry, and in the[Pg 238] midst of the confusion the guard approached to close the doors preparatory to starting. To him the distressed lady appealed in behalf of her offspring, for whom, she declared, there was no room in any of the carriages, and further stated that she herself was obliged to remain with her youngest, who was at present in charge of her next to the youngest in another car. The guard was finally obliged to settle matters by delaying the train, and adding thereto another carriage.

The conversation incidental to the foregoing episode had been interpreted to Will by his brother, whose French had been polished up considerably during his three weeks' stay in Paris. He and Will were over for an autumn tour in Europe, and having "done" the British Isles and the capital of France, they were now on their way to Germany.

Will had enjoyed his trip thus far immensely, even though he knew no modern language but his American English, and he now looked forward to seeing the wonders of the father-land with all the bright anticipations of fourteen.

"What's that for, I wonder?" he suddenly exclaimed, catching sight of a small triangular piece of looking-glass set in the upholstery at the back of the front seat of the compartment. "Read what it says underneath, Charlie;" which the latter accordingly did, reporting that it was a device for calling the guard in cases of emergency, the way of doing so being to break the glass and pull a cord which would be discovered in the recess thus exposed, which cord communicated with the engine. But if the glass be broken, the notice went on to state, without sufficient cause, a heavy fine would be imposed on the offender.

"But suppose I couldn't read French, as indeed I can't," surmised Will, "and were in here alone—that is, alone in company with a crazy man who was about to murder me—how could I ever imagine that by smashing that bit of glass I might stop the train, and so be rescued? Besides—"

"Nonsense!" interrupted his brother. "Don't you see the directions are repeated both in English and German underneath?" and Will looked and saw, and immediately turned his attention out of the window, leaving Charlie to peruse his French newspaper in peace.

There was, however, not much of interest to observe in the somewhat barren-looking country through which the railroad ran; and voting France (Paris excepted) a very slow place indeed, Will buried himself for the rest of the afternoon in a boy's book of travels. Nevertheless, the journey proved a very tedious one, and after stopping for dinner at six, the two brothers endeavored to bridge over the remaining hours with sleep.

"Verviers!" shouted out by the guard, was the sound that caused them both to awake with a start. The train had stopped, and all the passengers were preparing to "descend," as the French have it.

"Now, Will," said Charlie, sleepily, trying to read his guide-book by the light of the flickering lamp in the roof of the compartment, "this is the Belgian custom-house; but all trunks registered through to Cologne, as ours is, they allow to pass unopened; but it seems that everybody is required to get out and offer their satchels to the officers for examination; but, as we've only one between us, there's no use in our both rousing up, so you just take this, and follow the crowd."

"All right," responded Will, now thoroughly wide-awake; "then I can say I've been in Belgium;" and snatching the small hand-bag from the rack, he hurried off, leaving his brother to continue his nap.

"Wonder which room it is?" surmised Will, for the platform was deserted, and there were four waiting-apartments opening out on it. It did not take him long, however, to discover the proper one for him to enter, and he was soon among the jostling crowd that surrounded the low counter, behind which were the customs officials, who sometimes opened a bag and glanced over the contents, and then hastily marked on it with a piece of chalk, but oftener simply chalked it without examining anything whatever, which latter harmless operation was all to which Will's effects were subjected.

Rejoiced at getting through so easily, he turned to hasten out to the cars again, but the door by which he had entered was now closed, and guarded by a gendarme. From the gestures the latter made when he attempted to pass him, Will understood that he was to go out by another exit into an adjoining waiting-room, where he found most of the other passengers assembled in the true flock-of-sheep style; but while he was wondering where he might be driven to next, he saw through the window the train, containing his brother, his ticket, and his power of speech, whirl suddenly away into the darkness, and disappear.

"Hallo here! let me out!" cried Will, rushing up to the officer stationed at the door. "I'm going to Cologne on those cars, don't you understand?"

But the man evidently did not understand, for he shook his head in a most stupid fashion, at the same time feeling for his sword, as though afraid "le jeune Américain" were going to brush past him with the energy characteristic of the nation.

Seeing that it was now too late for him to catch the already vanished train, even if he should succeed in gaining the tracks, Will gave up the attempt, and resigned himself to his fate.

"But why are not the other passengers in as great a state of anxiety as I am?" he thought, as he looked around at his sleepy fellow-travellers, who had disposed themselves about the room in various attitudes of weariness and patience. "Perhaps, though, they're not going to Cologne; very likely they're all bound for some place in Belgium here, on another road. And now what's to become of me, a green American, with no French at my tongue's end but 'oui' and 'parlez-vous,' not a sign of a ticket, and with but six francs in my purse? Oh, Charlie, why did you send me out with this bag?" and Will paced nervously up and down the waiting-room, trying to think of a way out of his predicament. Suddenly a happy idea struck him.

"I'll go out by the door that opens into the town, and walk along till I come to the end of the station building, and then perhaps I can make my way around to the inside, and so see if the train really has gone off for good. Very likely it was only switched off, and will soon back down again."

Putting this plan into execution, Will was soon out in the streets of the queer Belgian city, wandering along in the darkness, striving to find the end of the dépôt, and then of a high board fence, which latter seemed to be interminable. At length, however, he reached an open space, and was about to leap across a telegraphic arrangement that ran beside the tracks, when one of the inevitable gens-d'armes sprang up from somewhere behind, and gave Will to understand that he was not allowed to put himself in the way of being killed by an engine.

Poor boy, he was now completely bewildered, and wished with all his might that he had studied French instead of Latin. As it was, he screamed out, "Cologne! Cologne!" with an energy born of desperation, and the officer, faintly comprehending his meaning, at last muttered a quick reply in his unknown tongue, and hurried Will off back to the dépôt with an alacrity that caused our young American to have some fears he might be taking him to quite another sort of station-house. But, notwithstanding their haste, when they entered the waiting-room it was empty, and the flashing of a red lamp on the rear car of a departing train told whither its former occupants had gone.

And now Will understood it all. The passengers had[Pg 239] been locked up while some switching was done, simply to prevent them from becoming confused.

"What a blockhead I was!" he thought, quite angry with himself. "If I'd just staid quietly where I was put, and not gone racing off, with the idea that I knew more about their railroads than the Belgians themselves, I'd never have gotten myself into such a scrape. And now what am I to do? I suppose Charlie's still fast asleep in the cars, being carried further and further away from me; and here am I, left at nine o'clock at night in an entirely foreign country, without a ticket, and, for the matter of that, without a tongue in my head. Why didn't some of the other passengers explain matters to me, and— But, pshaw! what good would it have done if they had? I couldn't have understood a word."

All this time the gendarme had been talking with the ticket agent, and pointing to Will as though the latter had been a stray dog not capable of saying anything in his own behalf. What should he do? where should he go? and how could he manage to pass away the time that might elapse till his brother should miss him and return in search of him? And now the officer came up, and began to question him, speaking very slowly, and in an extremely loud tone. Notwithstanding, poor Will could only understand a word here and there, and at length, in despair, he determined to try a new plan.

Taking out his purse, he showed the money therein to the gendarme, at the same time exclaiming, "Hotel! hotel!" and pointing to himself. The officer evidently comprehended this pantomime, for, with a nod to the ticket agent, who had all the while been grinning through his little wicket, he motioned for Will to follow him out into the street.

The Hôtel du Chemin de Fer (Railroad Hotel) was close at hand, and having in a few rapid sentences explained the situation to the landlord, the gendarme left Will to his own resources.

The latter thought for a moment that he had stepped into pandemonium itself, for opening on the right into the main hall of the hotel was a large apartment decorated with a sort of stage scenery to represent trees and lakes, the room itself being filled with little tables, around which were seated men smoking and drinking beer, while a thin-toned brass band discoursed popular music from a gallery overhead.

Will stared at this strange sight with all his eyes, and then suddenly became conscious at one and the same moment that he was hungry and being talked at by the proprietor. Encouraged by his former success with one-word speeches, Will simply said "Coffee," and then sat down at one of the little tables, where he was speedily served with a generous cup of the invigorating beverage, together with a plentiful supply of bread and butter.

"What a queer adventure!" thought the youth, his spirits much improved by the warm draughts of coffee, to say nothing of the lights and music. "But now how shall I ever be able to make the man understand that I want to stay here all night? Charlie's sure to come back for me in the morning. Oh, I have it! I'll register my name on a piece of paper, hand it to the landlord, and exhibit my purse again;" which plan succeeded admirably, and "William C. Brooks, New York, America," was immediately shown to a good-sized room on the second floor, where he lost no time in retiring to rest after his eventful evening.

His sleep, however, was not undisturbed, for all night long he imagined himself to be an American locomotive towing an English steamer across the Atlantic, and crashing into several icebergs on the way.

The next morning Will opened his eyes in a flood of sunshine, and at first could not recollect where he was, but the whistling of an engine near by soon recalled to him his situation, causing him at the same time to hurry with his dressing, that he might hasten over to the station for news of his brother. He did not have to go as far as that, however, for as he was going down stairs he ran against Charlie coming up, and Will had never been so glad to see anybody or anything since the time when he used to open his eyes on Christmas mornings to behold the well-filled stocking hanging from the mantel-piece.

Over the breakfast, which the brothers ate together in the theatrical dining-room, the elder explained how he had not missed Will till the train had left Verviers a good distance behind. "And then when I awoke from my nap," continued Charlie, "you can imagine the fright I was in when I found the cars going, and you gone. We had just passed Aix-la-Chapelle when I made the dreadful discovery, or I might have driven back here from there with a carriage, for it is only twenty miles off; but as it was, I could do nothing but fret till we arrived at Cologne, from which city I at once telegraphed to the station-master here, and ascertained that you were safe and sound, and fast asleep in bed."

"But why didn't they wake me up, and let me know that you knew that—" broke in Will, but choked the remainder of his speech with a swallow of coffee and a slice of bread, from a sudden remembrance of the crashing of icebergs, which might have been knocks on the door he had heard in his sleep.

"The whole thing was my fault, though," summed up Charlie, as, having settled with the smiling landlord, they walked over to the station. "I should not have let you go off alone in a new country; but then," he could not help adding, "you should not have left the rest of the flock, when you were shut up in the pen."

"I never will again," said Will, as they took their places in the train for Cologne; "I'll be in future the meekest lamb they ever drove. But anyway," he continued, as the cars rolled slowly away from the dépôt, "I can say I have been in Belgium, even though it was only by mistake, and so have experienced not an Arabian but a Belgian Night."

They were all in the sitting-room. Matilda Ann was trimming a bonnet to wear to the concert which was to take place that very evening in the Town-hall, and the roses did look so pretty that Hetty wished she was grown up enough to have some one come for her in a brand-new buggy, and take her to a concert; but where was the use of wishing? Every one told her she must not be too childish, and then every one said she mustn't think herself a young woman, and want long gowns and trains, and big braids and puffs—that there was "time enough yet." She wondered what "time enough" meant. It seemed to her as if it must be the time of freedom, and certainly that was a long way off.

Jane was sewing strips of woollen cloth together for the big balls that were to make carpet, and their mother was darning stockings, and they were all talking about the school-teacher who had lately come to the little brown house next to the district school. Jane said she was "hity-tity," mother said she didn't like to see so many furbelows, and Matilda Ann criticised her manner of wearing her hair; so Hetty ventured to say, "I don't think it matters much what she wears, or how she looks, if she can teach the children."

"Yes," said the mother, "it does matter; for children, need a good example."

"Of course she ought to be neat," said Hetty.

"Yes, and simple, and not be sticking on jewelry every day."

"For that matter, Aunt Maria says people in the city wear diamonds when they go to market."[Pg 240]

"That does not make it any more sensible; fools are to be found everywhere."

"But, mother, Miss Martin isn't a fool; she is very nice. I think you would like her."

"Perhaps so," said the mother, somewhat doubtfully; adding: "She had on a flounced skirt the last time I saw her. It takes a great deal of time to do them up nicely. Only rich folk ought to wear them."

"Suppose some one gave her her fine clothes?" said Hetty.

"Not very likely; but that would make it a little better."

Hetty went out to take a swing under the elm-tree, wondering why big people couldn't find something better to talk about than what other people wore. Then Jane spoke up:

"Hetty always hates to hear others spoken of when they can't take their own part."

"She's a good little thing, anyhow," said Matilda Ann, who was standing before the looking-glass, in high good humor, with the new bonnet on, and turning her head from side to side, so that she could the better survey the trimmings.

"Well," said Mrs. Hall, "you've stood there long enough, Matilda Ann. I never did see such an amazin' amount of vanity as there is nowadays."

"Oh, mother, I dare say you were just as silly when you were young," said Jane.

"No," said the mother, severely, "I never was given to fineries; my heart was set on higher things."

"I don't see, then, how father ever got the chance to do any courting."

"Jane," said Mrs. Hall, "Jedediah Hall would never have married me if I had been like the girls of the present day, who scorn to churn, and to wash, and to do housework of any sort. He respected a woman who could make her family comfortable."

"But the courting—did he ever talk nonsense, mother?"

"The courting was over in short meter, I can tell you. Nonsense?—no, there was no nonsense about him. Well, well, it's a long time ago." And she arose, and went out into the kitchen. The table was set for tea, and the biscuits were ready for the oven. She went to the cellar to skim the cream, and found a large bowl of custard had been left over from the dinner. There was more than would be eaten on their own table. What would she do with it? Pretty soon Hetty heard her mother calling her: "Hetty! Hetty!"

She ran in quickly from the garden.

"How would you like to take some of this custard to Miss Martin?"

"Splendid!" said Hetty. "But, mother," she said, hesitating, "I thought you didn't like her?"

"Pshaw, child, I didn't say so. I said I didn't approve of too much dress. Get your hat and a tin pail. Here;" and she poured out the custard. "Now go, and mind you come home in time for tea."

HETTY AND JIM—Drawn by T. Robinson.

HETTY AND JIM—Drawn by T. Robinson.

It was a level road, and the afternoon a pleasant one late in the fall. Hetty could not chase the squirrels, for fear of upsetting her pail; neither could she pick berries, for they were all gone. And so she trudged on silently, wishing she were as old as Matilda Ann, so that she might go to the concert. As she passed a lot which was covered with stubble, a boy appeared, leaning over the fence. He was a big fellow, and the son of an old neighbor, and Hetty liked him, but there were people who said he was mischievous, and told tales of him, which perhaps made him somewhat shy. He nodded pleasantly enough to her, however, and asked her where she was going.

"Down to Miss Martin's," was Hetty's reply.

"I say, Hetty," said Jim, "do you think Miss Martin thought it was me who tried to frighten her the other night?"[Pg 241]

"No," said Hetty.

"Well, I was afraid she did. Give a dog a bad name, you know, and he never gets rid of it."

"But, Jim, you don't mean to speak of yourself that way?" said Hetty.

"Yes, I do; people believe anything of me, and I half the time get the credit of doing things that never came into my head."

"I only heard a little about Miss Martin's fright; some one chased her, I believe."

"Yes, Sam Tompkins made believe he was a tramp, and scared her 'most out of her wits. He ought to have been shot. I licked him when I heard he had tried to make out it was me who did it, and I'll lick him again, too."

"Oh, don't, Jim; you had better forget all about it."

"Indeed I won't; I mean to make him repent it. See here, Hetty, I've got some tickets for the concert. Don't you want to go?"

"Don't I?" said Hetty; "I guess I do; but I can't, you know."

"Why not?"

"Oh, I am not big enough yet," said Hetty, blushing.

"Now I'll tell you what I'll do. If you will ask Miss Martin to go, I'll take you both, for, you see, I want to be sure that she doesn't hold any ill-will against me; and if she goes, all the people hereabouts will know that I was not the mean sneaking coward who tried to frighten her."

"All right," said Hetty. "I understand; and I will go on now as fast as I can, and coax Miss Martin to go."

"Let me know what she says when you come back, and I'll get the horse hitched, for father said he'd let me have the wagon."

"I will," said Hetty, already hastening on her way.

The teacher was sitting in rather a lonely and dejected mood at her window as Hetty's bright face appeared before her. She was a young girl, with soft brown eyes and a patient expression. It was her first experience at district-school teaching, and she found it laborious. Hetty soon told her errand, and in her eagerness so mixed up the concert and the custard and Matilda Ann's new bonnet that Miss Martin was bewildered, but after a while made out what it all meant.

"So James Stokes wants me to go to the concert?"

"Yes, ma'am, and me too."

"Have you permission?"

"I'll get it, Miss Martin. I'm sure mother'll say 'yes,'[Pg 242] and I sha'n't tell any one but her. I want to surprise Matilda Ann, and I will get ready and come here, so that Jim Stokes needn't go to our house."

"Please thank your mother kindly, Hetty, for the custard; it is so nice. And tell James I shall be happy to go. I knew he was not the one who frightened me."

Away Hetty flew, as fast as possible, to arrange the matter at home. Mrs. Hall could not say no, and Hetty soon exchanged her every-day clothes for her best gown and ribbons.

The Town-hall was crowded, and Hetty heard some one in a pink bonnet say, "Why, there's our Hetty; how did the child get here?" Then she turned her smiling face upon Matilda Ann in triumph.

When the concert was half over, and the singers were taking a rest, a very grand-looking person came to Miss Martin and said: "How do you do, my dear Amy? I am so glad to see you! And who is this little friend with you?"

Then the teacher spoke very kindly of Hetty as one of her best pupils, and Jim was also introduced, and the grand-looking lady said some very pleasant things to them.

"Who is that?" whispered Hetty.

"It is my aunt," replied Miss Martin—"the one who gives me so many pretty things. She would like me to live with her, but I prefer to maintain myself. I could never dress half so tastefully if she did not give me such nice clothes."

"Oh," said Hetty, much pleased to hear this confirmation of her own charitable supposition. "May I tell mother about it?" she asked.

"Certainly," said Miss Martin; "I wish you would, for I don't want to be thought extravagant."

From that time Miss Martin had no stancher friends than Jim and Hetty; and when one day Jim's big brother led her up the aisle of the village church as a bride, there were two young people behind her in white gloves and ribbons who looked almost as bright and happy as the chief actors of the day.

"STRAYS."—From a Painting by H. H. Cauty.

"STRAYS."—From a Painting by H. H. Cauty.

It was a beautiful clear day in October when I had my first view of Madeira. The high blue mountains, the green shores, and the white city of Funchal gleaming in the distance, looked very lovely to us as we approached the island.

About noon we anchored at a little distance from the city, and swarms of row-boats came around the ship. Some of them were full of half-naked brown boys, and if we threw a piece of money into the beautiful blue water, they would dive down and catch it before it reached the bottom. Some of the other boats were full of men, who came on board, bringing fans, canary-birds, parrots, feather flowers, basket-work, filigree jewelry, and many other things to sell.

We and some of the passengers got into a row-boat, after a good deal of trouble, because there is always a heavy swell there, so one minute the boat was very high up, and the next very low down. When we had managed to get in, we rowed to the city. There were great waves dashing up on the shore, and four or five bare-legged men rushed into the water, and drew the boat on land just as a wave came in.

What was our surprise to see waiting for us, instead of a horse and carriage, a great sleigh drawn by bullocks. This is called a bullock-car in English, and a carro in Portuguese. We got into one of them, with a great deal of laughter, and drove to the hotel. The driver walked by the side of the carro, and threw the end of a greasy rag first under one runner and then under the other, to make it run more easily.

When we arrived at the hotel, we found it was a great white building, with a lovely garden, which contained mango, guava, banana, custard-apple, and many other trees. Among them was what was called the moon-tree; it was covered with great white bell-like flowers, and was very beautiful. There were a great many gorgeous flowers and curious plants that we do not have in this country. The garden was surrounded by a wall eight feet high, and there were some fish-geraniums which reached above the top of it. There was a little arch covered with the night-blooming cereus, and that evening, when the buds had opened, we went out to see them in the moonlight. They were beautiful white blossoms, as large as your head, and had a faint perfume.

Next day we took a hammock ride about the town and surrounding country. Each hammock was fitted out with a mattress, pillows, and canopy, and slung on a long pole carried by two men. We reclined lazily against the pillows, and enjoyed the ride very much. The men, when they went up hill, carried us feet downward, but once they forgot, and carried us feet upward, and as the hill was very steep, we felt as if we were standing on our heads.

The houses of Funchal are low; and covered with white stucco, which looks very neat, but those of the poor have only one window without any glass, and are very dark and dismal inside. The streets are narrow, and some of them very steep. We often passed gardens surrounded by high walls, over which hung lovely flowering vines. Out in the country there were lantanas, geraniums, and fuchsias which seemed to be growing wild, and great cactus plants everywhere.

This beautiful and graceful art may be acquired by every girl and boy in the land who will take the necessary steps. And they are pleasant steps.

A pretty drawing-book, a nicely cut No. 2 Faber's drawing pencil, a piece of black India rubber, some pieces of tissue-paper to cover the drawings, unless the drawing-book is furnished with tissue-paper. These are the implements required. In this pencil drawing which I now recommend there are no lines, straight and slanting, repeated to utter weariness. This is object drawing, and drawing from nature also, and the objects are inexhaustible, being the leaves which nature gives to every plant and tree.

Drawings of leaves are beautiful when well done. The writer knew a young girl of twelve or thirteen years who began with drawing simple, easy leaves, and went on to more difficult ones season after season. Her drawing-books were charming; and not this alone, for she acquired a fund of pleasant knowledge, which loses none of its delight as time goes on. She began with leaves, picked from the house plants which her mother cultivated.

As the spring came on, she sought the wild leaves in the woods. No one who has not tried it can judge of the interest felt in the beauty and wonderful variety in the growth and shapes of leaves. They seem endless; and when to these are added the leaves of forest trees, the enchanting maples, beeches, birches, and hosts of others, it may be imagined that young fingers may find ample employment in portraying these, to say nothing of the wild flowers which come on in the New England woods—the early anemones, hepatica, bloodroot, and all the flowery train—as the season advances.

This young girl learned to draw with great accuracy, and to this day (for it is years since she began) her ready pencil can sketch any object with ease and skill, the beginning of which was the effort to draw a leaf of smilax.

I have a few simple outlines of leaves ready, but will reserve them for another time.[Pg 243]

Any one who had seen Biddy O'Dolan in the old hard days, when she was dirty and ragged and wretched and rude, and lived in the street, and slept in a cellar, would hardly have known her if he had seen her three weeks after she came to live with the Kennedys.

Biddy was not pretty, but she had a clear skin—now the dirt was washed off—and bright, earnest eyes. Now, too, she wore neat and pretty clothing. Her dark curly hair was nicely brushed, and tied with fresh ribbons. She had a small, pleasant room all for herself and her doll, and Miss Kennedy had taught her how to keep it in order.

Biddy had given a great deal of trouble to this gentle lady at first, because Biddy had many unpleasant habits. She used bad words; she did not seem to think it any harm to tell lies; she was not at all neat; she was sometimes willful and disobedient; she was often careless, broke dishes, tore her clothes, and put things out of order. These things were a much greater trouble to Miss Kennedy than Biddy knew. Miss Kennedy was so good and kind and true that Biddy's faults grieved her much, and carelessness and disorder were like pain to her, she was herself so neat and pure, like a fine white pearl.

But Miss Kennedy never forgot what poor Biddy's life had been, and Biddy was so affectionate and grateful, and tried so hard, that Miss Kennedy grew to love her dearly, and little by little Biddy conquered her old bad habits.

She did not see much of Mr. Kennedy, who was very busy, and was away a great deal. When she did see him, he had always a kind word and a pleasant smile for her, which made Biddy feel as if he took care of her.

Charley had brought her the doll, as Biddy said he would. But she could not make him come within a block of the house; and when he saw Biddy so fresh and clean in her pretty new garments, he had blushed and run away almost without speaking. She did not see much of him. She met him sometimes when she was out on an errand. The last time she had seen him he had looked very much pleased, but she had not been able to get him to speak to her. She thought him more bashful than ever.

Biddy did not forget Charley, or cease to wish he might have a nice home in the same house with her; but she was kept so busy with her easy but constant duties in waiting upon Miss Kennedy, who was also teaching her to read, that time flew very fast with Biddy, and it was midsummer when one day she went out on an errand, and—did not come back!

Miss Kennedy waited and wondered; and when it began to grow dark, and Biddy had not come back, she grew really alarmed. One of the servants had been sent out twice to look for Biddy, but in vain. At last, just as Miss Kennedy was about to send for him, Mr. Kennedy came in. As soon as he learned the cause of his sister's alarm, he comforted her in the very best way by starting out to search for Biddy himself.

He had not gone more than twenty steps before a boy, who had watched him come out, stopped him, and to his great surprise gave him a message from Biddy.

Mr. Kennedy ran back and spoke with his sister, and then went quickly away with the boy who had brought Biddy's message.

Now this is what had happened.

After Biddy had done her errand, she thought about Charley, and felt a great wish to see him. She was prettily dressed, and it came into her head that it would be a grand thing if she could walk by Mrs. Brown's stand, and see if the old woman would know her. For a long time after she ran away from Mrs. Brown, Biddy had been afraid to go near her old home for fear Mrs. Brown might claim her, and perhaps in some way be able to hide her from her new friends. But she had lost most of this fear, and now thought it would be great fun to step up to the stand and buy something, and see what the old woman would say.

The old days when she and Charley used to be so much together came into Biddy's mind as she walked along, swinging her parasol. She remembered a great many little things about him and his quiet kindnesses to her, which she had hardly noticed at the time, and she thought with new pleasure of Mr. Kennedy's words to her in the morning. He had passed her in the hall as he was going out, and had laid his hand on her head and said: "I think I shall be able to do something for Charley very soon. Will you like that, Biddy?" And Biddy, as usual, when her heart was very full, had not said a word. "I'll tell Charley," she thought to herself.

At last when there was only one more block to walk before reaching Mrs. Brown's stall, and Biddy was just beginning to think about what she should say to the old woman, she noticed an unusual stir down the street. People old and young were darting about, running around and forward, yelling at the tops of their voices; and there was another low hoarse sound Biddy could not make out. Nearest were some children running in her direction and screaming. Biddy stopped near a pile of empty boxes. She was full of wonder and fear. One of the children was Charley. He saw Biddy at the same moment she saw him, and it seemed as if he flew, he came toward her so fast. As he came up with her he grasped her arms, turned her around, and pushed her toward the boxes with one quick movement.

"Up wid 'ee, Biddy! Quick—oh, quick!" he called to her.

His white face and his piercing cry made Biddy obey him without a thought of asking why. She clutched at the boxes, and scrambled up, and Charley helped her by his hands and his shoulders. The boxes did not stand even, and they tottered as she climbed, but Charley leaned his little body against them, and stretched out his arms, and held them steady. Biddy was not a moment too quick. As she threw herself forward across the topmost box, the shuffle and clatter of many feet and the shouting and screaming seemed to be all around them. Biddy could not look down. She was so frightened, and had climbed so fast, she could hardly breathe, but she heard a snapping and crunching of jaws and a hoarse rattling breath beneath her. She was not able to think; she only clung with all her might, so dizzy that it seemed as if she and the boxes were swimming. Several shots were fired, and it seemed as if there were more noise and confusion than before. Then some one said,

"Poor children!"

Biddy felt herself lifted down. She was shaking all over. There were a great many people around her, but they didn't make so much noise now. She heard some one saying,

"It's Griffith's blood-hound—a good dog enough, too, if those idle scamps had let him alone. But it wouldn't stand no nonsense—that sort of dog never does. By heavens! it snapped that great chain like a pipe stem, and was after them like a tiger in no time!"

Then another voice said: "Did you see the little boy? He's almost the smallest little fellow you ever saw. But he was a hero. He saved the little girl's life; he gave up his own for it. I saw and heard the whole thing from the window overhead here, and I'll never see a braver deed done. I tell you, he's a hero; his father can be proud of him."[Pg 244]

"His father!" said another and rougher voice. "That boy hain't got anyone belongin' to him. Take a look at his clothes—what's left of 'em from that brute's teeth! He's never had too much to eat nor too much to wear, you kin just bet yer life on that. But you're right, mister; he was a hero, an' no' mistake. He held as still as a mouse, an' with a grip like death, while that durned critter chawed up his legs."

Biddy was beginning to understand; so were the other children, the little boys and girls who had known and laughed at and nicknamed Charley all his silent, bashful life.

They stood around, gazing horror-struck at the dead hound that lay just beyond the curb-stone, and at Charley, lying all mangled and perfectly still in the arms of a policeman. A cart with cushions in it backed up to the curb, and just as the policeman was trying to move Charley so as to lay him on the cushions, he moaned and opened his eyes. He looked at the children. They saw this look, and crowded up to the cart, sobbing.

One of them exclaimed, "Oh, Charley, we'll never call ye 'Polly' no more!"

Another boy leaned close over Charley, and said, "The men sez as ye're a real hero, Charley; jist ye brace up!"

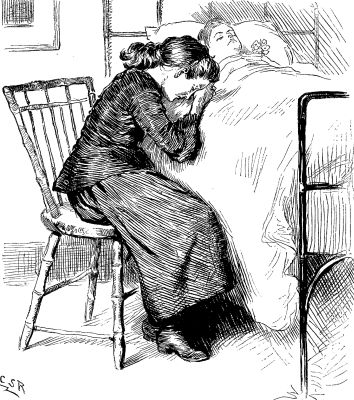

CHARLEY IN THE HOSPITAL.

CHARLEY IN THE HOSPITAL.

A faint smile passed over Charley's face. He turned his eyes, with the same kind, calm look in them, among the people, till he saw Biddy. Then the tired eyes flashed with joy. He saw that she was quite safe. He moved his hand a little toward her. Her lips quivered; she reached out her arms; and they placed her in the cart on the cushions by Charley's side. Just before it started, Biddy asked the little boy who had last spoken to Charley to go and tell Mr. Kennedy what had happened, and to say that she should stay with Charley till he got well. When Mr. Kennedy reached the hospital, Biddy was crying as if her heart would break, and poor, brave, tender, bashful little Charley had got quite well, and had gone home to be with his Father.

The shock and the sorrow of little Charley's death changed Biddy very much. It was long before Mr. and Miss Kennedy could persuade her that she was not to blame for it. It seemed to the poor child as if she had been cruel to climb into safety, leaving Charley to such a fate. But she had really not been at all to blame. She had obeyed Charley's startling and earnest cry, without thinking, or even having time to think, until it was too late to act in any other way.

After a time the sharpness of this sorrow passed away, and the thought of Charley became full of comfort and help to Biddy. As she grew older she could understand that if Charley had lived, he could not have been very happy, he was so feeble, and shrank from people so much. And she could feel, if she did not understand, that his death was a noble one, an act of love so simple and so whole that it was a gift, the gift of a great example, helping every one who knew of it to be more brave and true.

Biddy lived on with the Kennedys, and she has helped Mr. Kennedy from time to time to find out little children as wretched as she once was. In this way she has already been the means of getting six poor children into good homes, where they have a chance to learn how to live. She remembers so well her sad childhood that she understands, even better than you or I would, how to speak to and help these poor children when they first begin to do better, and get so discouraged because their old bad habits pull them down, and make it hard for them to do well. Biddy goes to see them, and talks with them so kindly, and with so much patience and love, that they are comforted and ready to try harder than ever. When she tells them that she was once just as dirty and rough and naughty as they have ever been, and they see how sweet and good she has become, it fills them with courage and hope. You can very well suppose that Biddy did not always find it an easy thing to help these children. Perhaps you think that any little girl would jump at the chance of being taken from the street and put in a good and pleasant home. Biddy thought so, until she tried to help Katy Kegan. She was the second little girl Biddy found for Mr. Kennedy. Biddy had known Katy Kegan all her life, and liked her better than any other little girl when they used to be living on the street. Yet when Biddy became better off, and tried to make things just as nice for Katy, that little girl didn't see it as Biddy did at all, and gave her more care and worry than all the other five. I'll tell you something about this.

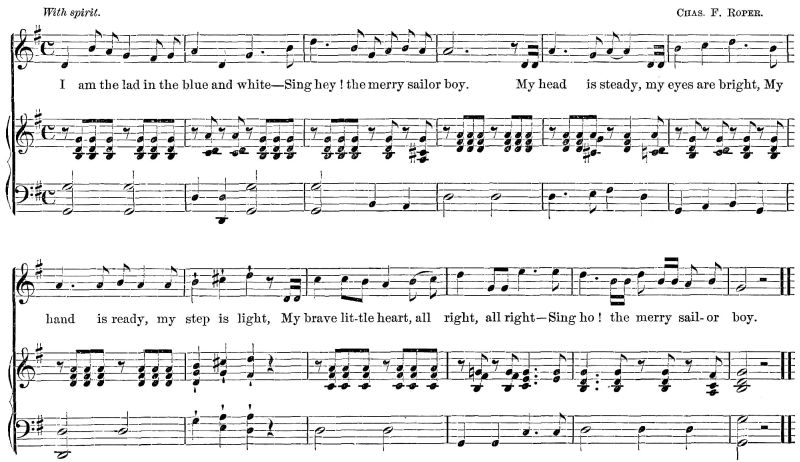

I am the lad in the blue and white—

Sing hey! the merry sailor boy.

My head is steady, my eyes are bright,

My hand is ready, my step is light,

My brave little heart, all right, all right—

Sing ho! the merry sailor boy.

I am the lad in the blue and white—

Sing hey! the merry sailor boy.

I sit in the shrouds when the soft winds blow,

The light waves rock me to and fro;

I run up aloft or down below—

Sing ho! the ready sailor boy.

I am the lad in the blue and white—

Sing ho! the merry sailor boy.

When the skies are blue and the sea is calm,

The air is full of spice and balm,

And the shore is set with shadowy palm,

Oh, glad is the merry sailor boy!

"What will you do when the great winds blow?

What will you do, my sailor boy?"—

When great winds blow, and are icy cold,

Never you fear, for my heart is bold:

I'll watch my captain, do what I'm told—

Sing ho! the ready sailor boy.

"If a foe should come—in such a plight,

What would you do, brave sailor boy?"—

Run up the "Stars and Stripes" in his sight,

Stand by my captain, wrong or right,

And give the foe an up-and-down fight—

Sing ho! the gallant sailor boy.

I am the lad in the blue and white—

Sing hey! the merry sailor boy.

I carry my country's flag and name;

I never will do her wrong or shame;

I'll fight her battles and share her fame—

Sing ho! the gallant sailor boy.

Everett Station, Georgia.

I want to tell you about a pet squirrel I had. My uncle was having some trees cut down, when the men found three young squirrels in one of them. One of the squirrels got killed, and one ran away, but my uncle caught the other and put it in his pocket, and forgot all about it. After a while he put his hand in his pocket for something, and the squirrel bit him. We tamed it, and it would run all over the trees in the yard, until one day some boys passing by shot it, thinking it was wild. My little brother cried, and I came near crying too. We buried it in the flower garden.

Chesly B. Howard, Jun.

February. 15, 1880.

I am nine years old. I was born in Boston, but for the last three years I have been living on a farm in Lakeville, Massachusetts. There are a number of lakes near here, and some of them have long Indian names, such as Assawampsett and Quiticus. Yesterday was a warm, spring-like day, and I saw two robins, and I heard the bluebirds singing.

Louis W. Clark.

Machias, Maine.

I like Young People very much. I have a summer-house, and in the summer I found a little humming-bird, with its wing broken, all tangled up in the flowers. I took it into the house, and fed it. It ate sugar and water. It had a funny little narrow tongue, and it put it out when it ate. It lived in the house two days, and then it died.

Nellie Longfellow (8 years old).

Sacramento, California.

My papa told me of a pretty way to designate the long months from the short ones. He learned it from a little girl when he was travelling in Oregon, and I think a good many little readers of Young People might be pleased with it. This is the way: close your hand, and point out the knuckle of the forefinger for January, and the depression between that and the middle knuckle for February. The middle knuckle designates March, and the next depression April; and so on to the small knuckle, which stands for July. Then go back to the forefinger for August, and proceed as before until all the months are named. It will be found that all the short ones fall between the fingers, while the knuckles stand for the long ones.

Phebe C. Brown.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I want to tell you about a young alligator and a water turtle papa had. He kept the turtle in the cellar, and the alligator in an earthen tank; but when it came winter he put that in the cellar too, in a tight box with air-holes. Some time afterward he went to look at the turtle and the alligator, and they had both disappeared. Where do you think they could have gone?

Puss.

Dixon Spring, Tennessee, February 18.

I am a subscriber to Young People, and I like it very much. I am ten years old. The creeks are in the way, so I can not go to school now, but I will go in the spring. Some of our flowers are in full bloom, and the weather is very pleasant. But we had a snow-storm last week, and I enjoyed it so much!

Fannie M. Young.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I know some little girls who live in the country. They set a little table in the yard, and put on it tin dishes with chicken food in them. Then they ring a toy bell, and the chickens have learned to come and stand round the table and eat. If a chicken hops on the table, it is not allowed to eat any more, and in this way they are taught to behave very nicely.

Sadie.

Decorah, Iowa.

I am a little Norwegian girl, though I was born in America. I am twelve years old. Not all the Norwegian ships in which Leif Ericsson and his company sailed to America were as small as the one described in "Ships Past and Present," in Young People No. 14, for one of them had sixty men and five women on board. Some of the ancient Norwegian ships were quite large. I have read in Traditions of Norwegian Kings, by Snorro Sturrleson, about Ormen Lange (the Long Serpent), a large and handsome ship which belonged to King Olaf Tryggveson. That part of the keel which touched the ground when the ship was being built measured 112 feet. The ship carried a crew of more than 600 men. It was Leif Ericsson, not Olaf Ericsson, who sailed to America.

E.

Tryggveson, who reigned in Norway a.d. 995-1000, had ships which were the wonder of the North. His largest war ship was the Long Serpent, supposed to be of the size of a frigate of forty-five guns. In a great sea-fight with the Kings of Denmark and Sweden, King Olaf Tryggveson was conquered, and is said to have sprung overboard from the famous Long Serpent into a watery grave.

Danville, Illinois.

Here is a recipe that some little girl may like to try. Two table-spoonfuls sugar; one table-spoonful butter; one table-spoonful milk; one well-beaten egg; four atoms of cream of tartar; two atoms of soda; flour enough to make a batter. You must get cook or mamma to measure the atoms. This recipe will make four little patty-pans of cake, and there will be some batter left to thicken for cookies. I cut out the cookies with mamma's thimble.

Puss Hunter.

Washington, D. C.

In our parlor there is a little mouse that has a hole in one corner of the fire-place. Before I fed it it was quite tame, and would run all about the room. I feed it now, and it only comes to get the crumbs I put close by its hole. Can any one among your correspondents tell me how to tame it?

E. L. M.

East Haven, Connecticut.

I have a rabbit, kitten, parrot, dog, canary, and a pair of chickens. I had a crow, but it died. I have a burying-ground for my pets, and in it there is the poor crow, a dog, two bantams, and seven canaries.

Susie D. B.

Buffalo, New York.

I want to tell you about my dog Joe. He is a setter. He does a great many capers. He watches for the boy who brings the evening paper, and takes it, and brings it up stairs to us. He plays hide-and-seek with me, and sometimes I tie a rope to his collar, and he draws me on my skates. How fast we do go! One day I hitched him to a sled for the first time, and he did not know what to make of it. He ran a little way, and then tipped me into a snow-bank, and made for home.

A. O. Thayer.

Barton, Maryland.

I had a pair of pet rabbits which I prized very much. Papa built a hutch for them, and they enjoyed their home very much. I fed them with clover, cabbage, and apples. Sometimes I gave them a dish of sweet milk to drink. They were growing so nice; but we had an old cat which I suppose thought if the rabbits were out of the way, she would get all the milk herself. One morning I fed them, and forgot to give Spiney her milk. (That was the old cat's name.) So she went down to the hutch and watched them drink their milk. When they had finished, they popped their little heads out between the bars. Old Spiney sprang on them, and that was the last of my poor rabbits.

Maggie Bermingham (10 years).

Bertha A. F. saw the bluebirds at Sag Harbor, Long Island, on the day before St. Valentine's, and on February 20 she picked willow "pussies." O. T. Mason says he found the "pussies" in Medway, Massachusetts, as early as January 18, but he neglected to report them.

Leon M. F.—If you dampen the skin under the feathers with water, and sprinkle on it a little finely pulverized sulphur, your pigeons will probably be relieved.

Aggie R. H.—Nourmahal, afterward called Nourjehan, or "Light of the World," was the wife of Selim, son of Akbar, Mogul Emperor of Hindostan. Selim succeeded his father in 1605, and was henceforth known as Jehanghir, or "Conqueror of the World." In the early part of his reign Selim was intemperate and cruel, but after his marriage with the beautiful Nourmahal his conduct greatly improved. Her influence over her husband was very great. He took no step without consulting her, and as she was an extraordinary and accomplished woman, her advice was always wise and judicious. Jehanghir died in 1627, and was succeeded by his son Shah Jehan, who was the father of Aurungzebe, whose beautiful daughter, Lalla Rookh, is the heroine of Moore's poem. The historical facts concerning the beautiful Nourmahal are very meagre, but a few glimpses into her life are given in the notes to the "Vale of Cashmere," the last story in Lalla Rookh.

W. Clarence.—To make a kite, the sticks must first be tied tightly and firmly together in the centre. A string is then put round the outside. The end of each stick should be notched to hold the string in place. The paper, which should be thin and tough, is now pasted on. A tail of pieces of paper or cloth tied at intervals in a string must be fastened at the bottom to balance the kite in the wind. The length of the tail depends on the size of the kite.

W. F. B.—O. N. T. is simply a trade-mark, and stands for "our new thread."

E. L. C.—There are so many French magazines, it is difficult to say which is the best. The Revue des Deux Mondes has a high literary character. Jewett's Spiers's French-and-English Dictionary is the best for ordinary use. Translating is not often remunerative.

"Patriotic Boys."—Scholarships, subject to certain conditions, can be obtained at nearly any college in the United States.

Johnny P.—The long-bow was the English national weapon in early times. It was originally used by the Norse tribes, and was brought into Western Europe by Rollo, first Duke of Normandy, a direct ancestor of William the Conqueror. When the Normans invaded England they carried the long-bow with them, and as the Saxons had no weapon so powerful, they readily adopted it. The proper length of the long-bow, which was made of yew or ash, was the height of the archer who used it. The largest ones, however, were six feet long, and as the arrow was always half the length of the bow, the longest arrows measured three feet, which is just a cloth yard. They were therefore given the name of "cloth-yard shaft." The arrows were made of oak, ash, or yew. They were tipped with steel, and ornamented at the other end with three gray goose feathers, from whence comes the name of "gray-goose shaft," usually applied to those arrows which were shorter than the cloth yard measure. The arrow or bolt of the cross-bow, or arbalast, was also tipped with steel, and varied in length according to the size of the cross-bow.

"Subscriber," New York.—It is not easy to stop a canary from moulting. The best way to treat it is to feed it with nothing but rapeseed, and two or three times a week give it a slice of hard-boiled egg. It should have plenty of fresh drinking water, in which you might put every morning a few drops of "bird tonic," which can be purchased at any bird store. Do not hang the cage in a very hot room.

Kate Williamson.—Your letter was very gratifying. Tell your little friend Madeleine we would be glad to receive a French letter from her.

Favors are received from Matthew Laflin, Clyde L. Kimball, Julia W., Florence D., Nettie Denniston, Emma Barnwell, Harry Moore, J. M. Brennan, Della L. G., George W. Herbert, C. L. C., S. Engle, Edward G., A. H. Ellard, Mary Valentine, Julia Grace T., Katie C. Yorke, Franklin J. Kaufman, Charles A. H., W. K. M., J. O. F., John L. Stillman, James A. S., George L. Bannister, Elwyn A. S., Dannie C. Douglass, Hattie H., Robert A. A., Herbert D. Stafford, Clarkie W. Lockwood, Dwight Ruggles.

Correct answers to puzzles are received from Anna and Charles O., Lulu Pearce, S. G. Rosenbaum, L. Mahler, E. M. Devoe, C. W. Hanner, Harry Austin, F. M. Richards, G. K. MacNaught, J. R. Glen, Addie Allen, "Puss," James Smith, Peter Slane, John B. Whitlock, Gordon Shelby, "Subscriber," Henry J. L., Mary, Sadie, E. Allen Cushing, Ernest B. Allen, E., Jack Gladwin, Lena E. S., Harry L. A., Lillie V. S., Allen N., Bertha A. F., G. C. Meyer, May Shepard, Clara B. C., Essie B.

I am composed of 14 letters.

My 9, 10, 7 is a tavern.

My 12, 9, 13, 14 is a heap.

My 6, 7, 8 is an insect.

My 11, 10, 14 is a unit.

My 1, 6, 4, 5 is to throw.

My 4, 2, 10, 3, 14, 8 is a short poem.

My whole is a city in Europe.

Chester B. F.

A measure of quantity. A valediction. A public speaker. A Jewish prophet. A well-known liquid. A nobleman. A town in Texas. Answer.—Two famous painters.

Charles L. B.

My first is in barn, but not in shed.

My second is in green, but not in red.

My third is in stone, but not in brick.

My fourth is in branch, but not in stick.

My fifth is in head, but not in feet.

My whole is something good to eat.

Mary.

First, not cold. Second, a surface. Third, true. Fourth, masculine.

M. L.

I am composed of 32 letters.

My 13, 22, 8, 12 is a wild animal.

My 9, 3, 21 is a tree.

My 19, 8, 9, 17 is not hard.

My 16, 3, 6 is what we all must do.

My 28, 14, 11 is what most all of us can do.

My 4, 23, 29, 2 is a number.

My 7, 20, 15 is a large body of water.

My 26, 27, 15, 16, 6, 21 is a school-book.

My 32, 24, 5, 10, 15, 12 is a ruler of a country.

My 1, 8, 18 is an adverb.

My 25, 15, 30, 31 is used for seasoning.

My whole is a proverb.