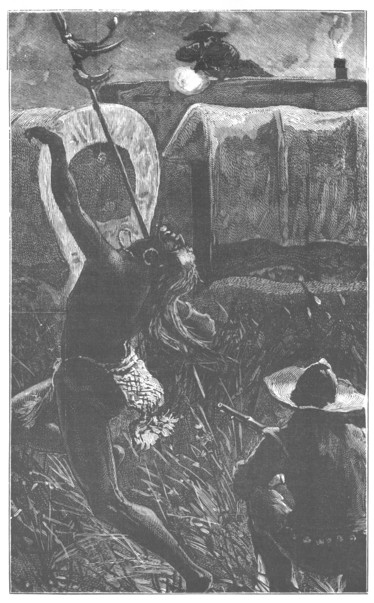

[See page 129.]

Title: Our Home in the Silver West: A Story of Struggle and Adventure

Author: Gordon Stables

Release date: March 9, 2009 [eBook #28291]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

OUR HOME IN THE SILVER WEST

A Story of Struggle and Adventure

BY

GORDON STABLES, C.M., M.D., R.N.

AUTHOR OF 'THE CRUISE OF THE SNOWBIRD,' 'WILD ADVENTURES ROUND THE POLE,'

ETC., ETC.

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56, Paternoster Row; 65, St. Paul's Churchyard

and 164 Piccadilly

Richard Clay and Sons, Limited,

london and bungay.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Highland Feud. | 11 |

| II. | Our Boyhood's Life. | 23 |

| III. | A Terrible Ride. | 30 |

| IV. | The Ring and the Book. | 44 |

| V. | A New Home in the West. | 54 |

| VI. | The Promised Land at Last. | 64 |

| VII. | On Shore at Rio. | 77 |

| VIII. | Moncrieff Relates His Experiences. | 86 |

| IX. | Shopping and Shooting. | 96 |

| X. | A Journey That Seems Like a Dream. | 106 |

| XI. | The Tragedy at the Fonda. | 115 |

| XII. | Attack by Pampa Indians. | 125 |

| XIII. | The Flight and the Chase. | 134 |

| XIV. | Life on an Argentine Estancia. | 146 |

| XV. | We Build our House and Lay Out Gardens. | 155 |

| XVI. | Summer in the Silver West. | 165 |

| XVII. | The Earthquake. | 175 |

| XVIII. | Our Hunting Expedition. | 185 |

| XIX. | In the Wilderness. | 197 |

| XX. | The Mountain Crusoe. | 209 |

| XXI. | Wild Adventures on Prairie and Pampas. | 221 |

| XXII. | Adventure With a Tiger. | 231 |

| XXIII. | A Ride for Life. | 244 |

| XXIV. | The Attack on the Estancia. | 255 |

| XXV. | The Last Assault. | 266 |

| XXV | Farewell to the Silver West. | 279 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE | |

| The Figure Springs into the Air | Frontispiece |

| Orla thrusts his Muzzle into my Hand | 10 |

| Ray lay Stark and Stiff | 18 |

| 'Look! He is Over!' | 33 |

| He pointed his Gun at me | 41 |

| 'I'll teach ye!' | 74 |

| Fairly Noosed | 99 |

| 'Ye can Claw the Pat' | 138 |

| Comical in the Extreme | 195 |

| Tries to steady himself to catch the Lasso | 203 |

| Interview with the Orang-outang | 214 |

| On the same Limb of the Tree | 236 |

| The Indians advanced with a Wild Shout | 268 |

OUR HOME IN THE SILVER WEST

Why should I, Murdoch M'Crimman of Coila, be condemned for a period of indefinite length to the drudgery of the desk's dull wood? That is the question I have just been asking myself. Am I emulous of the honour and glory that, they say, float halo-like round the brow of the author? Have I the desire to awake and find myself famous? The fame, alas! that authors chase is but too often an ignis fatuus. No; honour like theirs I crave not, such toil is not incumbent on me. Genius in a garret! To some the words may sound romantic enough, but—ah me!—the position seems a sad one. Genius munching bread and cheese in a lonely attic, with nothing betwixt the said genius and the sky and the cats but rafters and tiles! I shudder to think of it. If my will were omnipotent, Genius should never shiver beneath the tiles, never languish in an attic. Genius should be clothed in purple and fine linen, Genius should—— 'Yes, aunt, come in; I'm not very busy yet.'

My aunt sails into my beautiful room in the eastern tower of Castle Coila.

'I was afraid,' she says, almost solemnly, 'I might be 12 disturbing your meditations. Do I find you really at work?'

'I've hardly arrived at that point yet, dear aunt. Indeed, if the truth will not displease you, I greatly fear serious concentration is not very much in my line. But as you desire me to write our strange story, and as mother also thinks the duty devolves on me, behold me seated at my table in this charming turret chamber, which owes its all of comfort to your most excellent taste, auntie mine.'

As I speak I look around me. The evening sunshine is streaming into my room, which occupies the whole of one story of the tower. Glance where I please, nothing is here that fails to delight the eye. The carpet beneath my feet is soft as moss, the tall mullioned windows are bedraped with the richest curtains. Pictures and mirrors hang here and there, and seem part and parcel of the place. So does that dark lofty oak bookcase, the great harp in the west corner, the violin that leans against it, the jardinière, the works of art, the arms from every land—the shields, the claymores, the spears and helmets, everything is in keeping. This is my garret. If I want to meditate, I have but to draw aside a curtain in yonder nook, and lo! a little baize-covered door slides aside and admits me to one of the tower-turrets, a tiny room in which fairies might live, with a window on each side giving glimpses of landscape—and landscape unsurpassed for beauty in all broad Scotland.

But it was by the main doorway of my chamber that auntie entered, drawing aside the curtains and pausing a moment till she should receive my cheering invitation. And this door leads on to the roof, and this roof itself is a sight to see. Loftily domed over with glass, it is at once a conservatory, a vinery, and tropical aviary. Room here for trees even, for miniature palms, while birds of the rarest plumage flit silently from bough to bough among the oranges, or lisp out the sweet lilts that have descended to them from sires that sang in foreign lands. Yonder a 13 fountain plays and casts its spray over the most lovely feathery ferns. The roof is very spacious, and the conservatory occupies the greater part of it, leaving room outside, however, for a delightful promenade. After sunset coloured lamps are often lit here, and the place then looks even more lovely than before. All this, I need hardly say, was my aunt's doing.

I wave my hand, and the lady sinks half languidly into a fauteuil.

'And so,' I say, laughingly, 'you have come to visit Genius in his garret.'

My aunt smiles too, but I can see it is only out of politeness.

I throw down my pen; I leave my chair and seat myself on the bearskin beside the ample fireplace and begin toying with Orla, my deerhound.

'Aunt, play and sing a little; it will inspire me.'

She needs no second bidding. She bends over the great harp and lightly touches a few chords.

'What shall I play or sing?'

'Play and sing as you feel, aunt.'

'I feel thus,' my aunt says, and her fingers fly over the strings, bringing forth music so inspiriting and wild that as I listen, entranced, some words of Ossian come rushing into my memory:

'The moon rose in the East. Fingal returned in the gleam of his arms. The joy of his youth was great, their souls settled as a sea from a storm. Ullin raised the song of gladness. The hills of Inistore rejoiced. The flame of the oak arose, and the tales of heroes were told.'

Aunt is not young, but she looks very noble now—looks the very incarnation of the music that fills the room. In it I can hear the battle-cry of heroes, the wild slogan of clan after clan rushing to the fight, the clang of claymore on shield, the shout of victory, the wail for the dead. There are tears in my eyes as the music ceases, and my aunt turns once more towards me. 14

'Aunt, your music has made me ashamed of myself. Before you came I recoiled from the task you had set before me; I longed to be out and away, marching over the moors gun in hand and dogs ahead. Now I—I—yes, aunt, this music inspires me.'

Aunt rises as I speak, and together we leave the turret chamber, and, passing through the great conservatory, we reach the promenade. We lean on the battlement, long since dismantled, and gaze beneath us. Close to the castle walls below is a well-kept lawn trending downwards with slight incline to meet the loch which laps over its borders. This loch, or lake, stretches for miles and miles on every side, bounded here and there by bare, black, beetling cliffs, and in other places

|

'O'erhung by wild woods thickening green, |

a very cloudland of foliage. The easternmost horizon of this lake is a chain of rugged mountains, one glance at which would tell you the season was autumn, for they are crimsoned over with blooming heather. The season is autumn, and the time is sunset; the shadow of the great tower falls darkling far over the loch, and already crimson streaks of cloud are ranged along the hill-tops. So silent and still is it that we can hear the bleating of sheep a good mile off, and the throb of the oars of a boat far away on the water, although the boat itself is but a little dark speck. There is another dark speck, high, high above the crimson clouds. It comes nearer and nearer; it gets bigger and bigger; and presently a huge eagle floats over the castle, making homeward to his eyrie in the cliffs of Ben Coila.

The air gets cooler as the shadows fall; I draw the shawl closer round my aunt's shoulders. She lifts a hand as if to deprecate the attention.

'Listen, Murdoch,' she says. 'Listen, Murdoch M'Crimman.'

She seldom calls me by my name complete. 15

'I may leave you now, may I not?'

'I know what you mean, aunt,' I reply. 'Yes; to the best of my ability I will write our strange story.'

'Who else would but you, Murdoch M'Crimman, chief of the house of Crimman, chief of the clan?'

I bow my head in silent sorrow.

'Yes, aunt; I know. Poor father is gone, and I am chief.'

She touches my hand lightly—it is her way of taking farewell. Next moment I am alone. Orla thrusts his great muzzle into my hand; I pat his head, then go back with him to my turret chamber, and once more take up my pen.

A blood feud! Has the reader ever heard of such a thing? Happily it is unknown in our day. A blood feud—a quarrel 'twixt kith and kin, a feud oftentimes bequeathed from bleeding sire to son, handed down from generation to generation, getting more bitter in each; a feud that not even death itself seems enough to obliterate; an enmity never to be forgotten while hills raise high their heads to meet the clouds.

Such a feud is surely cruel. It is more, it is sinful—it is madness. Yet just such a feud had existed for far more than a hundred years between our family of M'Crimman and the Raes of Strathtoul.

There is but little pleasure in referring back to such a family quarrel, but to do so is necessary. Vast indeed is the fire that a small spark may sometimes kindle. Two small dead branches rubbing together as the wind blows may fire a forest, and cause a conflagration that shall sweep from end to end of a continent.

It was a hundred years ago, and forty years to that; the head of the house of Stuart—Prince Charles Edward, whom his enemies called the Pretender—had not yet set foot on Scottish shore, though there were rumours almost 16 daily that he had indeed come at last. The Raes were cousins of the M'Crimmans; the Raes were head of the clan M'Rae, and their country lay to the south of our estates. It was an ill-fated day for both clans when one morning a stalwart Highlander, flying from glen to glen with the fiery cross waving aloft, brought a missive to the chief of Coila. The Raes had been summoned to meet their prince; the M'Crimman had been solicited. In two hours' time the straths were all astir with preparations for the march. No boy or man who could carry arms, 'twixt the ages of sixteen and sixty, but buckled his claymore to his side and made ready to leave. Listen to the wild shout of the men, the shrill notes of bagpipes, the wailing of weeping women and children! Oh, it was a stirring time; my Scotch blood leaps in all my veins as I think of it even now. Right on our side; might on our side! We meant to do or die!

|

'Rise! rise! lowland and highland men! Bald sire to beardless son, each come and early. Rise! rise! mainland and island men, Belt on your claymores and fight for Prince Charlie. Down from the mountain steep— Up from the valley deep— Out from the clachan, the bothy and shieling; Bugle and battle-drum, Bid chief and vassal come, Loudly our bagpipes the pibroch are pealing.' |

M'Crimman of Coila that evening met the Raes hastening towards the lake.

'Ah, kinsman,' cried M'Crimman, 'this is indeed a glorious day! I have been summoned by letter from the royal hands of our bold young prince himself.'

'And I, chief of the Raes, have been summoned by cross. A letter was none too good for Coila. Strathtoul must be content to follow the pibroch and drum.'

'It was an oversight. My brother must neither fret nor fume. If our prince but asked me, I'd fight in the ranks for him, and carry musket or pike or pistol.'

'It's good being you, with your letter and all that. Kinsman though you be, I'd have you know, and I'd have our prince understand, that the Raes and Crimmans are one and the same family, and equal where they stand or fall.'

'Of that,' said the proud Coila, drawing himself up and lowering his brows, 'our prince is the best judge.'

'These are pretty airs to give yourself, M'Crimman! One would think your claymore drank blood every morning!'

'Brother,' said M'Crimman, 'do not let us quarrel. I have orders to see your people on the march. They are to come with us. I must do my duty.'

'Never!' shouted Rae. 'Never shall my clan obey your commands!'

'You refuse to fight for Charlie?'

'Under your banner—yes!'

'Then draw, dog! Were you ten times more closely related to me, you should eat your words or drown them in your blood!'

Half an hour afterwards the M'Crimmans were on the march southwards, their bold young chief at their head, banners streaming and pibroch ringing! but, alas! their kinsman Rae lay stark and stiff on the bare hillside.

There and then was established the feud that lasted so long and so bitterly. Surrounded by her vassals and retainers, loud in their wailing for their departed chief, the widowed wife had thrown herself on the body of her husband in a paroxysm of wild, uncontrollable grief.

But nought could restore life and animation to that lowly form. The dead chief lay on his back, with face up-turned to the sky's blue, which his eyes seemed to pierce. His bonnet had fallen off, his long yellow hair floated on the grass, his hand yet grasped the great claymore, but his tartans were dyed with blood.

Then a brother of the Rae approached and led the weeping woman gently away. Almost immediately the 20 warriors gathered and knelt around the corpse and swore the terrible feud—swore eternal enmity to the house of Coila—'to fight the clan wherever found, to wrestle, to rackle and rive with them, and never to make peace

|

'While there's leaf on the forest Or foam on the river.' |

We all know the story of Prince Charlie's expedition, and how, after victories innumerable, all was lost to his cause through disunions in his own camps; how his sun went down on the red field of Culloden Moor; how true and steadfast, even after defeat, the peasant Highlanders were to their chief; and how the glens and straths were devastated by fire and sword; and how the streams ran red with the innocent blood of old men and children, spilled by the brutal soldiery of the ruthless duke.

The M'Crimmans lost their estates. The Raes had never fought for Charlie. Their glen was spared, but the hopes of M'Rae—the young chief—were blighted, for after years of exile the M'Crimman was pardoned, and fires were once more lit in the halls of Castle Coila.

Long years went by, many of the Raes went abroad to fight in foreign lands wherever good swords were needed and lusty arms to wield them withal; but those who remained in or near Strathtoul still kept up the feud with as great fierceness as though it had been sworn but yesterday.

Towards the beginning of the present century, however, a strange thing happened. A young officer of French dragoons came to reside for a time in Glen Coila. His name was Le Roi. Though of Scotch extraction, he had never been before to our country. Now hospitality is part and parcel of the religion of Scotland; it is not surprising, therefore, that this young son of the sword should have been received with open arms at Coila, nor that, dashing, handsome, and brave himself, he should have fallen in love with the winsome daughter of the then chief of the M'Crimmans. 21 When he sought to make her his bride explanations were necessary. It was no uncommon thing in those days for good Scotch families to permit themselves to be allied with France; but there must be rank on both sides. Had a thunderbolt burst in Castle Coila then it could have caused no greater commotion than did the fact when it came to light that Le Roi was a direct descendant of the chief of the Raes. Alas! for the young lovers now. Le Roi in silence and sorrow ate his last meal at Castle Coila. Hospitality had never been shown more liberally than it was that night, but ere the break of day Le Roi had gone—never to return to the glen in propriâ personâ. Whether or not an aged harper who visited the castle a month thereafter was Le Roi in disguise may never be known; but this, at least, is fact—that same night the chief's daughter was spirited away and seen no more in Coila.

There was talk, however, of a marriage having been solemnized by torchlight, in the little Catholic chapel at the foot of the glen, but of this we will hear more anon, for thereby hangs a tale.

In course of time Coila presented the sad spectacle of a house without a head. Who should now be heir? The Scottish will of former chiefs notified that in event of such an occurrence the estates should pass 'to the nearest heirs whatever.'

But was there no heir of direct descent? For a time it seemed there would be or really was. To wit, a son of Le Roi, the officer who had wedded into the house of M'Crimman.

Now our family was brother-family to the M'Crimmans. M'Crimmans we were ourselves, and Celtic to the last drop of blood in our veins.

Our claim to the estate was but feebly disputed by the French Rae's son. His father and mother had years ago crossed the bourne from which no traveller ever returns, and he himself was not young. The little church or chapel in which the marriage had been celebrated was a ruin—it 22 had been burned to the ground, whether as part price of the terrible feud or not, no one could say; the priest was dead, or gone none knew whither; and old Mawsie, a beldame, lived in the cottage that had once been the Catholic manse.

Those were wild and strange times altogether in this part of the Scottish Highlands, and law was oftentimes the property of might rather than right.

At the time, then, our story really opens, my father had lived in the castle and ruled in the glens for many a long year. I was the first-born, next came Donald, then Dugald, and last of all our one sister Flora.

What a happy life was ours in Glen Coila, till the cloud arose on our horizon, which, gathering force amain, burst in storm at last over our devoted heads!

On our boyhood's life—that, I mean, of my brothers and myself—I must dwell no longer than the interest of our strange story demands, for our chapters must soon be filled with the relation of events and adventures far more stirring than anything that happened at home in our day.

And yet no truer words were ever spoken than these—'the boy is father of the man.' The glorious battle of Waterloo—Wellington himself told us—was won in the cricket field at home. And in like manner our greatest pioneers of civilisation, our most successful emigrants, men who have often literally to lash the rifle to the plough stilts, as they cultivate and reclaim the land of the savage, have been made and manufactured, so to speak, in the green valleys of old England, and on the hills and moors of bonnie Scotland.

Probably the new M'Crimman of Coila, as my father was called on the lake side and in the glens, had mingled more, far more, in life than any chief who had ever reigned before him. He would not have been averse to drawing the sword in his country's cause, had it been necessary, but my brothers and I were born in peaceful times, shortly after the close of the war with Russia. No, my father could have drawn the claymore, but he could also use the ploughshare—and did. 24

There were at first grumblers in the clans, who lamented the advent of anything that they were pleased to call new-fangled. Men there were who wished to live as their forefathers had done in the 'good old times'—cultivate only the tops of the 'rigs,' pasture the sheep and cattle on the upland moors, and live on milk and meal, and the fish from the lake, with an occasional hare, rabbit, or bird when Heaven thought fit to send it.

They were not prepared for my father's sweeping innovations. They stared in astonishment to see the bare hillsides planted with sheltering spruce and pine trees; to see moss and morass turned inside out, drained and made to yield crops of waving grain, where all was moving bog before; to see comfortable cottages spring up here and there, with real stone walls and smiling gardens front and rear, in place of the turf and tree shielings of bygone days; and to see a new school-house, where English—real English—was spoken and taught, pour forth a hundred happy children almost every weekday all the year round.

This was 'tempting Providence, and no good could come of it;' so spoke the grumblers, and they wondered indeed that the old warlike chiefs of M'Crimman did not turn in their graves. But even the grumblers got fewer and further between, and at last long peace and plenty reigned contentedly hand in hand from end to end of Glen Coila, and all around the loch that was at once the beauty and pride of our estate.

Improvements were not confined to the crofters' holdings; they extended to the castle farm and to the castle itself. Nothing that was old about the latter was swept away, but much that was new sprang up, and rooms long untenanted were now restored.

A very ancient and beautiful castle was that of Coila, with its one huge massive tower, and its dark frowning embattled walls. It could be seen from far and near, for even the loch itself was high above the level of the sea. 25 I speak of it, be it observed, in the past tense, solely because I am writing of the past—of happy days for ever fled. The castle is still as beautiful—nay, even more so, for my aunt's good taste has completed the improvements my father began.

I do not think any one could have come in contact with father, as I remember him during our early days at Coila, without loving and respecting him. He was our hero—my brothers' and mine—so tall, so noble-looking, so handsome, whether ranging over the heather in autumn with his gun on his shoulder, or labouring with a hoe or rake in hand in garden or meadow.

Does it surprise any one to know that even a Highland chieftain, descended from a long line of warriors, could handle a hoe as deftly as a claymore? I grant he may have been the first who ever did so from choice, but was he demeaned thereby? Assuredly not; and work in the fields never went half so cheerfully on as when father and we boys were in the midst of the servants. Our tutor was a young clergyman, and he, too, used to throw off his black coat and join us.

At such times it would have done the heart of a cynic good to have been there; song and joke and hearty laugh followed in such quick succession that it seemed more like working for fun than anything else.

And our triumph of triumphs was invariably consummated at the end of harvest, for then a supper was given to the tenants and servants. This supper took place in the great hall of the castle—the hall that in ancient days had witnessed many a warlike meeting and Bacchanalian feast.

Before a single invitation was made out for this event of the season every sheaf and stook had to be stored and the stubble raked, every rick in the home barn-yards had to be thatched and tidied; 'whorls' of turnips had to be got up and put in pits for the cattle, and even a considerable portion of the ploughing done. 26

'Boys,' my father would say then, pointing with pride to his lordly stacks of grain and hay, 'Boys,

|

'"Peace hath her victories, No less renowned than war." |

And now,' he would add, 'go and help your tutor to write out the invitations.'

So kindly-hearted was father that he would even have extended the right hand of peace and fellowship to the Raes of Strathtoul. The head of this house, however, was too proud; yet his pride was of a different kind from father's. It was of the stand-aloof kind. It was even rumoured that Le Roi, or Rae, had said at a dinner-party that my good, dear father brought disgrace on the warlike name of M'Crimman because he mingled with his servants in the field, and took a very personal interest in the welfare of his crofter tenantry.

But my father had different views of life from this semi-French Rae of Strathtoul. He appreciated the benefits and upheld the dignity, and even sanctity, of honest labour. Had he lived in the days of Ancient Greece, he might have built a shrine to Labour, and elevated it to the rank of goddess. Only my father was no heathen, but a plain, God-fearing man, who loved, or tried to love, his neighbour as himself.

If our father was a hero to us boys, not less so was he to our darling mother, and to little Sister Flora as well. So it may be truthfully said that we were a happy family. The time sped by, the years flew on without, apparently, ever a bit of change from one Christmas Day to another. Mr. Townley, our tutor, seemed to have little ambition to 'better himself,' as it is termed. When challenged one morning at breakfast with his want of desire to push,

'Oh,' said Townley, 'I'm only a young man yet, and really I do not wish to be any happier than I am. It will be a grief to me when the boys grow older and go out into the world and need me no more.' 27

Mr. Townley was a strict and careful teacher, but by no means a hard taskmaster. Indoors during school hours he was the pedagogue all over. He carried etiquette even to the extent of wearing cap and gown, but these were thrown off with scholastic duties; he was then—out of doors—as jolly as a schoolboy going to play at his first cricket-match.

In the field father was our teacher. He taught us, and the 'grieve,' or bailiff, taught us everything one needs to know about a farm. Not in headwork alone. No; for, young as we were at this time, my brothers and I could wield axe, scythe, hoe, and rake.

We were Highland boys all over, in mind and body, blood and bone. I—Murdoch—was fifteen when the cloud gathered that finally changed our fortunes. Donald and Dugald were respectively fourteen and thirteen, and Sister Flora was eleven.

Big for our years we all were, and I do not think there was anything on dry land, or on the water either, that we feared. Mr. Townley used very often to accompany us to the hills, to the river and lake, but not invariably. We dearly loved our tutor. What a wonderful piece of muscularity and good-nature he was, to be sure, as I remember him! Of both his muscularity and good-nature I am afraid we often took advantage. Flora invariably did, for out on the hills she would turn to him with the utmost sang-froid, saying, 'Townley, I'm tired; take me on your back.' And for miles Townley would trudge along with her, feeling her weight no more than if she had been a moth that had got on his shoulders by accident. There was no tiring Townley.

To look at our tutor's fair young face, one would never have given him the credit of possessing a deal of romance, or believed it possible that he could have harboured any feeling akin to love. But he did. Now this is a story of stirring adventure and of struggle, and not a love tale; so the truth may be as well told in this place as further 28 on—Townley loved my aunt. It should be remembered that at this time she was young, but little over twenty, and in every way she was worthy to be the heroine of a story.

Townley, however, was no fool. Although he was admitted to the companionship of every member of our family, and treated in every respect as an equal, he could not forget that there was a great gulf fixed between the humble tutor and the youngest sister of the chief of the M'Crimmans. If he loved, he kept the secret bound up in his own breast, content to live and be near the object of his adoration. Perhaps this hopeless passion of Townley's had much to do with the formation of his history.

Those dear old days of boyhood! Even as they were passing away we used to wish they would last for ever. Surely that is proof positive that we were very happy, for is it not common for boys to wish they were men? We never did.

For we had everything we could desire to make our little lives a pleasure long drawn out. Boys who were born in towns—and we knew many of these, and invited them occasionally to visit us at our Highland home—we used to pity from the bottom of our hearts. How little they knew about country sports and country life!

One part of our education alone was left to our darling mother—namely, Bible history. Oh, how delightful it used to be to listen to her voice as, seated by our bedside in the summer evenings, she told us tales from the Book of Books! Then she would pray with us, for us, and for father; and sweet and soft was the slumber that soon visited our pillows.

Looking back now to those dear old days, I cannot help thinking that the practice of religion as carried on in our house was more Puritanical in its character than any I 29 have seen elsewhere. The Sabbath was a day of such solemn rest that one lived as it were in a dream. No food was cooked; even the tables in breakfast-room and dining-hall were laid on Saturday; no horse left the stables, the servants dressed in their sombrest and best, moved about on tiptoe, and talked in whispers. We children were taught to consider it sinful even to think our own thoughts on this holy day. If we boys ever forgot ourselves so far as to speak of things secular, there was Flora to lift a warning finger and with terrible earnestness remind us that this was God's day.

From early morn to dewy eve all throughout the Sabbath we felt as if our footsteps were on the boundaries of another world—that kind, loving angels were near watching all our doings.

I am drawing a true picture of Sunday life in many a Scottish family, but I would not have my readers mistake me. Let me say, then, that ours was not a religion of fear so much as of love. To grieve or vex the great Good Being who made us and gave us so much to be thankful for would have been a crime which would have brought its own punishment by the sorrow and repentance created in our hearts.

Just one other thing I must mention, because it has a bearing on events to be related in the next chapter. We were taught then never to forget that a day of reckoning was before us all, that after death should come the judgment. But mother's prayers and our religion brought us only the most unalloyed happiness.

I have but to gaze from the window of the tower in which I am writing to see a whole fieldful of the daftest-looking long-tailed, long-maned ponies imaginable. These are the celebrated Castle Coila ponies, as full of mischief, fun, and fire as any British boy could wish, most difficult to catch, more difficult still to saddle, and requiring all the skill of a trained equestrian to manage after mounting. As these ponies are to-day, so they were when I was a boy. The very boys whom I mentioned in the last chapter would have gone anywhere and done anything rather than attempt to ride a Coila pony. Not that they ever refused, they were too courageous for that. But when Gilmore led a pony round, I know it needed all the pluck they could muster to put foot in stirrup. Flora's advice to them was not bad.

'There is plenty of room on the moors, boys,' she would say, laughing; and Flora always brought out the word 'boys' with an air of patronage and self-superiority that was quite refreshing. 'Plenty of room on the moors, so you keep the ponies hard at the gallop, till they are quite tired. Mind, don't let them trot. If you do, they will lie down and tumble.'

Poor Archie Bateman! I shall never forget his first wild scamper over the moorland. He would persist in riding in 31 his best London clothes, spotless broad white collar, shining silk hat, gloves, and all. Before mounting he even bent down to flick a little tiny bit of dust off his boots.

The ponies were fresh that morning. In fact, the word 'fresh' hardly describes the feeling of buoyancy they gave proof of. For a time it was as difficult to mount one as it would be for a fly to alight on a top at full spin. We took them to the paddock, where the grass and moss were soft. Donald, Dugald, and I held Flora's fiery steed vi et armis till she got into the saddle.

'Mind to keep them at it, boys,' were her last words, as she flew out and away through the open gateway. Then we prepared to follow. Donald, Dugald, and I were used to tumbles, and for five minutes or more we amused ourselves by getting up only to get off again. But we were not hurt. Finally we mounted Archie. His brother was not going out that morning, and I do believe to this day that Archie hoped to curry favour with Flora by a little display of horsemanship, for he had been talking a deal to her the evening before of the delights of riding in London.

At all events, if he had meant to create a sensation he succeeded admirably, though at the expense of a portion of his dignity.

No sooner was he mounted than off he rode. Stay, though, I should rather say that no sooner did we mount him than off he was carried. That is a way of putting it which is more in accordance with facts, for we—Donald, Dugald, and I—mounted him, and the pony did the rest, he, Archie, being legally speaking nolens volens. When my brothers and I emerged at last, we could just distinguish Flora waiting on the horizon of a braeland, her figure well thrown out against the sky, her pony curveting round and round, which was Flora's pet pony's way of keeping still. Away at a tangent from the proper line of march, Archie on his steed was being rapidly whirled. As soon as we came within sight of our sister, we observed her making signs in Archie's direction and concluded to follow. 32 Having duly signalled her wishes, Flora disappeared over the brow of the hill. Her intention was, we afterwards found out, to take a cross-cut and intercept, if possible, the mad career of Archie's Coila steed.

'Hurry up, Donald,' I shouted to my nearest brother; 'that pony is mad. It is making straight for the cliffs of Craigiemore.'

On we went at furious speed. It was in reality, or appeared to be, a race for life; but should we win? The terrible cliffs for which Archie's pony was heading away were perpendicular bluffs that rose from a dark slimy morass near the lake. Fifty feet high they were at the lowest, and pointed unmistakably to some terrible convulsion of Nature in ages long gone by. They looked like hills that had been sawn in half—one half taken, the other left.

Our ponies were gaining on Archie's. The boy had given his its head, but it was evident he was now aware of his danger and was trying to rein in. Trying, but trying in vain. The pony was in command of the situation.

On—on—on they rush. I can feel my heart beating wildly against my ribs as we all come nigher and nigher to the cliffs. Donald's pony and Dugald's both overtake me. Their saddles are empty. My brothers have both been unhorsed. I think not of that, all my attention is bent on the rider ahead. If he could but turn his pony's head even now, he would be saved. But no, it is impossible. They are on the cliff. There! they are over it, and a wild scream of terror seems to rend the skies and turn my blood to water.

But lo! I, too, am now in danger. My pony has the bit fast between his teeth. He means to play at an awful game—follow my leader! I feel dizzy; I have forgotten that I might fling myself off even at the risk of broken bones. I am close to the cliff—I—hurrah! I am saved! Saved at the very moment when it seemed nothing could save me, for dear Flora has dashed in front of me—has cut across my bows, as sailors would say, striking my pony with all 36 the strength of her arm as she is borne along. Saved, yes, but both on the ground. I extricate myself and get up. Our ponies are all panting; they appear now to realize the fearfulness of the danger, and stand together cowed and quiet. Poor Flora is very pale, and blood is trickling from a wound in her temple, while her habit is torn and soiled. We have little time to notice this; we must ride round and look for the body of poor Archie.

It was a ride of a good mile to reach the cliff foot, but it took us but a very short time to get round, albeit the road was rough and dangerous. We had taken our bearings aright, but for a time we could see no signs of those we had come to seek. But presently with her riding-whip Flora pointed to a deep black hole in the slimy bog.

'They are there!' she cried; then burst into a flood of tears.

We did the best we could to comfort our little sister, and were all returning slowly, leading our steeds along the cliff foot, when I stumbled against something lying behind a tussock of grass.

The something moved and spoke when I bent down. It was poor Archie, who had escaped from the morass as if by a miracle.

A little stream was near; it trickled in a half-cataract down the cliffs. Donald and Dugald hurried away to this and brought back Highland bonnetfuls of water. Then we washed Archie's face and made him drink. How we rejoiced to see him smile again! I believe the London accent of his voice was at that moment the sweetest music to Flora she had ever heard in her life.

'What a pwepostewous tumble I've had! How vewy, vewy stoopid of me to be wun away with!'

Poor Flora laughed one moment at her cousin and cried the next, so full was her heart. But presently she proved herself quite a little woman.

'I'll ride on to the castle,' she said, 'and get dry things ready. You'd better go to bed, Archie, when you come 37 home; you are not like a Highland boy, you know. Oh, I'm so glad you're alive! But—ha, ha, ha! excuse me—but you do look so funny!' and away she rode.

We mounted Archie on Dugald's nag and rode straight away to the lake. Here we tied our ponies to the birch-trees, and, undressing, plunged in for a swim. When we came out we arranged matters thus: Dugald gave Archie his shirt, Donald gave him a pair of stockings, and I gave him a cap and my jacket, which was long enough to reach his knees. We tied the wet things, after washing the slime off, all in a bundle, and away the procession went to Coila. Everybody turned out to witness our home-coming. Well, we did look rather motley, but—Archie was saved.

My own adventures, however, had not ended yet. Neither my brothers nor Flora cared to go out again that day, so in the afternoon I shouldered my fishing rod and went off to enjoy a quiet hour's sport.

What took my footsteps towards the stream that made its exit from the loch, and went meandering down the glen, I never could tell. It was no favourite stream of mine, for though it contained plenty of trout, it passed through many woods and dark, gloomy defiles, with here and there a waterfall, and was on the whole so overhung with branches that there was difficulty in making a cast. I was far more successful than I expected to be, however, and the day wore so quickly away that on looking up I was surprised to find that the sun had set, and I must be quite seven miles from home. What did that matter? there would be a moon! I had Highland legs and a Highland heart, and knew all the cross-cuts in the country side. I would try for that big trout that had just leapt up to catch a moth. It took me half an hour to hook it. But I did, and after some pretty play I had the satisfaction of landing a lovely three-pounder. I now reeled up, put my rod in its canvas case, and prepared to make the best of my way to the castle.

It was nearly an hour since the sun had gone down like 38 a huge crimson ball in the west, and now slowly over the hills a veritable facsimile of it was rising, and soon the stars came out as gloaming gave place to night, and moonlight flooded all the woods and glen.

The scene around me was lovely, but lonesome in the extreme, for there was not a house anywhere near, nor a sound to break the stillness except now and then the eerisome cry of the brown owl that flitted silently past overhead. Had I been very timid I could have imagined that figures were creeping here and there in the flickering shadows of the trees, or that ghosts and bogles had come out to keep me company. My nearest way home would be to cross a bit of heathery moor and pass by the neglected graveyard and ruined Catholic chapel; and, worse than all, the ancient manse where lived old Mawsie.

I never believed that Mawsie was a witch, though others did. She was said to creep about on moonlight nights like a dry aisk,[1] so people said, 'mooling' among heaps of rubbish and the mounds over the graves as she gathered herbs to concoct strange mixtures withal. Certainly Mawsie was no beauty; she walked 'two-fold,' leaning on a crutch; she was gray-bearded, wrinkled beyond conception; her head was swathed winter and summer in wraps of flannel, and altogether she looked uncanny. Nevertheless, the peasant people never hesitated to visit her to beg for herb-tea and oil to rub their joints. But they always chose the daylight in which to make their calls.

'Perhaps,' I thought, 'I'd better go round.' Then something whispered to me, 'What! you a M'Crimman, and confessing to fear!'

That decided me, and I went boldly on. For the life of me, however, I could not keep from mentally repeating those weird and awful lines in Burns' 'Tam o' Shanter,' descriptive of the hero's journey homewards on that 39 unhallowed and awful night when he forgathered with the witches:

|

'By this time he was 'cross the ford Whare in the snaw the chapman smo'red;[2] And past the birks[3] and meikle stane Whare drunken Charlie brak's neck-bane; And through the furze and by the cairn Where hunters found the murdered bairn, And near the thorn, aboon the well, Where Mungo's mither hanged hersel', When glimmering through the groaning trees, Kirk Alloway seemed in a bleeze.' |

I almost shuddered as I said to myself, 'What if there be lights glimmering from the frameless windows of the ruined chapel? or what if old Mawsie's windows be "in a bleeze"?'

Tall, ghostly-looking elder-trees grew round the old manse, which people had told me always kept moving, even when no breath of wind was blowing.

If I had shuddered before, my heart stood still now with a nameless dread, for sure enough, from both the 'butt' and the 'ben' of the so-called witch's cottage lights were glancing.

What could it mean? She was too old to have company, almost an invalid, with age alone and its attendant infirmities—so, at least, people said. But it had also been rumoured lately that Mawsie was up to doings which were far from canny, that lights had been seen flitting about the old churchyard and ruin, and that something was sure to happen. Nobody in the parish could have been found hardy enough to cross the glen-foot where Mawsie lived long after dark. Well, had I thought of all this before, it is possible that I might have given her house a wide berth. It was now too late. I felt like one in a dream, impelled forward towards the cottage. I seemed to be walking on the air as I advanced.

To get to the windows, however, I must cross the graveyard 40 yard and the ruin. This last was partly covered with tall rank ivy, and, hearing sounds inside, and seeing the glimmer of lanterns, I hid in the old porch, quite shaded by the greenery.

From my concealment I could notice that men were at work in a vault or pit on the floor of the old chapel, from which earth and rubbish were being dislodged, while another figure—not that of a workman—was bending over and addressing them in English. It was evident, therefore, those people below were not Highlanders, for in the face of the man who spoke I was able at a glance to distinguish the hard-set lineaments of the villain Duncan M'Rae. This man had been everything in his time—soldier, school-teacher, poacher, thief. He was abhorred by his own clan, and feared by every one. Even the school children, if they met him on the road, would run back to avoid him.

Duncan had only recently come back to the glen after an absence of years, and every one said his presence boded no good. I shuddered as I gazed, almost spellbound, on his evil countenance, rendered doubly ugly in the uncertain light of the lantern. Suppose he should find me! I crept closer into my corner now, and tried to draw the ivy round me. I dared not run, for fear of being seen, for the moonlight was very bright indeed, and M'Rae held a gun in his hand.

After a time, which appeared to be interminable, I heard Duncan invite the men into supper, and slowly they clambered up out of the pit, and the three prepared to leave together.

All might have been well now, for they passed me without even a glance in my direction; but presently I heard one of the men stumble.

'Hullo!' he said; 'is this basket of fish yours, Mr. Mac?'

'No,' was the answer, with an imprecation that made me quake. 'We are watched!' 41

In another moment I was dragged from my place of concealment, and the light was held up to my face.

'A M'Crimman of Coila, by all that is furious! And so, youngster, you've come to watch? You know the family feud, don't you? Well, prepare to meet your doom. You'll never leave here alive.'

He pointed his gun at me as he spoke.

'Hold!' cried one of the men. 'We came from town to do a bit of honest work, but we will not witness murder.'

'I only wanted to frighten him,' said M'Rae, lowering his gun. 'Look you, sir,' he continued, addressing me once more, 'I don't want revenge, even on a M'Crimman of Coila. I'm a poacher; perhaps I'm a distiller in a quiet way. No matter, you know what an oath is. You'll swear ere you leave here, not to breathe a word of what you've seen. You hear?'

'I promise I won't,' I faltered.

He handled his fowling-piece threateningly once again. Verily, he had just then a terribly evil look.

'I swear,' I said, with trembling lips.

His gun was again lowered. He seemed to breathe more freely—less fiercely.

'Go, now,' he said, pointing across the moor. 'If a poor man like myself wants to hide either his game or his private still, what odds is it to a M'Crimman of Coila?'

How I got home I never knew. I remember that evening being in our front drawing-room with what seemed a sea of anxious faces round me, some of which were bathed in tears. Then all was a long blank, interspersed with fearful dreams.

It was weeks before I recovered consciousness. I was then lying in bed. In at the open window was wafted the odour of flowers, for it was a summer's evening, and outside were the green whispering trees. Townley sat beside the bed, book in hand, and almost started when I spoke.

'Mr. Townley!'

'Yes, dear boy.'

'Have I been long ill?'

'For weeks—four, I think. How glad I am you are better! But you must keep very, very quiet. I shall go and bring your mother now, and Flora.'

I put out my thin hand and detained him.

'Tell me, Mr. Townley,' I said, 'have I spoken much in my sleep, for I have been dreaming such foolish dreams?'

Townley looked at me long and earnestly. He seemed to look me through and through. Then he replied slowly, almost solemnly,

'Yes, dear boy, you have spoken much.'

I closed my eyes languidly. For now I knew that Townley was aware of more than ever I should have dared to reveal. 44

My return to health was a slow though not a painful one. My mind, however, was clear, and even before I could partake of food I enjoyed hearing sister play to me on her harp. Sometimes aunt, too, would play. My mother seldom left the room by day, and one of my chief delights was her stories from Bible life and tales of Bible lands.

At last I was permitted to get up and recline in fauteuil or on sofa.

'Mother,' I said one day, 'I feel getting stronger, but somehow I do not regain spirits. Is there some sorrow in your heart, mother, or do I only imagine it?'

She smiled, but there were tears in her eyes.

'I'm sure we are all very, very happy, Murdoch, to have you getting well again.'

'And, mother,' I persisted, 'father does not seem easy in mind either. He comes in and talks to me, but often I think his mind is wandering to other subjects.'

'Foolish child! nothing could make your father unhappy. He does his duty by us all, and his faith is fixed.'

One day they came and told me that the doctor had ordered me away to the seaside. Mother and Flora were to come, and one servant; the rest of our family were to follow. 45

It was far away south to Rothesay we went, and here, my cheeks fanned by the delicious sea-breezes, I soon began to grow well and strong again. But the sorrow in my mother's face was more marked than ever, though I had ceased to refer to it.

The rooms we had hired were very pleasant, but looked very small in comparison with the great halls I had been used to.

Well, on a beautiful afternoon father and my brothers arrived, and we all had tea out on the shady lawn, up to the very edge of which the waves were lapping and lisping.

I was reclining in a hammock chair, listening to the sea's soft, soothing murmur, when father brought his camp-stool and sat near me.

'Murdoch, boy,' he said, taking my hand gently, almost tenderly, in his, 'are you strong enough to bear bad news?'

My heart throbbed uneasily, but I replied, bravely enough, 'Yes, dear father; yes.'

'Then,' he said, speaking very slowly, as if to mark the effect of every word, 'we are—never—to return—to Castle Coila!'

I was calm now, for, strange to say, the news appeared to be no news at all.

'Well, father,' I answered, cheerfully, 'I can bear that—I could bear anything but separation.'

I went over and kissed my mother and sister.

'So this is the cloud that was in your faces, eh? Well, the worst is over. I have nothing to do now but get well. Father, I feel quite a man.'

'So do we both feel men,' said Donald and Dugald; 'and we are all going to work. Won't that be jolly?'

In a few brief words father then explained our position. There had arrived one day, some weeks after the worst and most dangerous part of my illness was over, an advocate from Aberdeen, in a hired carriage. He had, he 46 said, a friend with him, who seemed, so he worded it, 'like one risen from the dead.'

His friend was helped down, and into father's private room off the hall.

His friend was the old beldame Mawsie, and a short but wonderful story she had to tell, and did tell, the Aberdeen advocate sitting quietly by the while with a bland smile on his face. She remembered, she said with many a sigh and groan, and many a doleful shake of head and hand, the marriage of Le Roi the dragoon with the Miss M'Crimman of Coila, although but a girl at the time; and she remembered, among many other things, that the priest's books were hidden for safety in a vault, where he also kept all the money he possessed. No one knew of the existence of this vault except her, and so on and so forth. So voluble did the old lady become that the advocate had to apply the clôture at last.

'It is strange—if true,' my father had muttered. 'Why,' he added, 'had the old lady not spoken of this before?'

'Ah, yes, to be sure,' said the Aberdonian. 'Well, that also is strange, but easily explained. The shock received on the night of the fire at the chapel had deprived the poor soul of memory. For years and years this deprivation continued, but one day, not long ago, the son of the present claimant, and probably rightful heir, to Coila walked into her room at the old manse, gun in hand. He had been down shooting at Strathtoul, and naturally came across to view the ruin so intimately connected with his father's fate and fortune. No sooner had he appeared than the good old dame rushed towards him, calling him by his grandfather's name. Her memory had returned as suddenly as it had gone. She had even told him of the vault. 'Perhaps,' continued he, with a meaning smile,

|

'"'Tis the sunset of life gives her mystical lore, And coming events cast their shadow before."' |

A fortnight after this visit a meeting of those concerned took place at the beldame's house. She herself pointed to the place where she thought the vault lay, and with all due legal formality digging was commenced, and the place was found not far off. At first glance the vault seemed empty. In one corner, however, was found, covered lightly over with withered ferns, many bottles of wine and—a box. The two men of law, Le Roi's solicitor and M'Crimman's, had a little laugh all to themselves over the wine. Legal men will laugh at anything.

'The priest must have kept a good cellar on the sly,' one said.

'That is evident,' replied the other.

The box was opened with some little difficulty. In it was a book—an old Latin Bible. But something else was in it too. Townley was the first to note it. Only a silver ring such as sailors wear—a ring with a little heart-shaped ruby stone in it. Book and ring were now sealed up in the box, and next day despatched to Edinburgh with all due formality. The best legal authorities the Scotch metropolis could boast of were consulted on both sides, but fate for once was against the M'Crimmans of Coila. The book told its tale. Half-carelessly written on fly-leaves, but each duly dated and signed by Stewart, the priest, were notes concerning many marriages, Le Roi's among the rest.

Even M'Crimman himself confessed that he was satisfied—as was every one else save Townley.

'The book has told one tale—or rather its binding has,' said Townley; 'but the ring may yet tell another.'

All this my father related to me that evening as we sat together on the lawn by the beach of Rothesay.

When he had finished I sat silently gazing seawards, but spoke not. My brothers told me afterwards that I looked as if turned to stone. And, indeed, indeed, my heart felt so. When father first told me we should go back no more to Coila I felt almost happy that the bad news was no 48 worse; but now that explanations had followed, my perplexity was extreme.

One thing was sure and certain—there was a conspiracy, and the events of that terrible night at the ruin had to do with it. The evil man Duncan M'Rae was in it. Townley suspected it from words I must have let fall in my delirium; but, worst of all, my mouth was sealed. Oh, why, why did I not rather die than be thus bound!

It must be remembered that I was very young, and knew not then that an oath so forced upon me could not be binding.

Come weal, come woe, however, I determined to keep my word.

The scene of our story changes now to Edinburgh itself. Here we had all gone to live in a house owned by aunt, not far from the Calton Hill. We were comparatively poor now, for father, with the honour and Christian feeling that ever characterized him, had even paid up back rent to the new owner of Coila Castle and Glen.

That parting from Coila had been a sad one. I was not there—luckily for me, perhaps; but Townley has told me of it often and often.

'Yes, Murdoch M'Crimman,' he said, 'I have been present at the funeral of many a Highland chief, but none of these impressed me half so much as the scene in Glen Coila, when the carriage containing your dear father and mother and Flora left the old castle and wound slowly down the glen. Men, women, and little ones joined in procession, and marched behind it, and so followed on and on till they reached the glen-foot, with the bagpipes playing "Farewell to Lochaber." This affected your father as much, I think, as anything else. As for your mother, she sat silently weeping, and Flora dared hardly trust herself to look up at all. Then the parting! The chief, your father, stood up and addressed his people—for "his people" he still would call them. There was not a tremor 49 in his voice, nor was there, on the other hand, even a spice of bravado. He spoke to them calmly, logically. In the old days, he said, might had been right, and many a gallant corps of heroes had his forefathers led from the glen, but times had changed. They were governed by good laws, and good laws meant fair play, for they protected all alike, gentle and simple, poor as well as rich. He bade them love and honour the new chief of Coila, to whom, as his proven right, he not only heartily transferred his lands and castle, but even, as far as possible, the allegiance of his people. They must be of good cheer, he said; he would never forget the happy time he had spent in Coila, and if they should meet no more on this earth, there was a Happier Land beyond death and the grave. He ended his brief oration with that little word which means so much, "Good-bye." But scarcely would they let him go. Old, bare-headed, white-haired men crowded round the carriage to bless their chief and press his hand; tearful women held children up that he might but touch their hair, while some had thrown themselves on the heather in paroxysms of a grief which was uncontrollable. Then the pipes played once more as the carriage drove on, while the voices of the young men joined in chorus—

|

"Youth of the daring heart, bright be thy doom As the bodings that light up thy bold spirit now. But the fate of M'Crimman is closing in gloom, And the breath of the grey wraith hath passed o'er his brow." |

'When,' added Townley, 'a bend of the road and the drooping birch-trees shut out the mournful sight, I am sure we all felt relieved. Your father, smiling, extended his hand to your mother, and she fondled it and wept no more.'

For a time our life, to all outward seeming, was now a very quiet one. Although Donald and Dugald were sent to that splendid seminary which has given so many great men and heroes to the world, the 'High School of 50 Edinburgh,' Townley still lived on with us as my tutor and Flora's.

What my father seemed to suffer most from was the want of something at which to employ his time, and what Townley called his 'talent for activity.' 'Doing nothing' was not father's form after leading so energetic a life for so many years at Coila. Like the city of Boston in America, Edinburgh prides itself on the selectness of its society. To this, albeit we had come down in the world, pecuniarily speaking, our family had free entrée. This would have satisfied some men; it did not satisfy father. He missed the bracing mountain air, he missed the freedom of the hills and the glorious exercise to which he had been accustomed.

He missed it, but he mourned it not. His was the most unselfish nature one could imagine. Whatever he may have felt in the privacy of his own apartment, however much he may have sorrowed in silence, among us he was ever cheerful and even gay. Perhaps, on the whole, it may seem to some that I write or speak in terms too eulogistic. But it should not be forgotten that the M'Crimman was my father, and that he is—gone. De mortuis nil nisi bonum.

The ex-chief of Coila was a gentleman. And what a deal there is in that one wee word! No one can ape the gentleman. True gentlemanliness must come from the heart; the heart is the well from which it must spring—constantly, always, in every position of life, and wherever the owner may be. No amount of exterior polish can make a true gentleman. The actor can play the part on the stage, but here he is but acting, after all. Off the stage he may or may not be the gentleman, for then he must not be judged by his dress, by his demeanour in company, his calmness, or his ducal bow, but by his actions, his words, or his spoken thoughts.

|

'Chesterfields and modes and rules For polished age and stilted youth. And high breeding's choicest school Need to learn this deeper truth: That to act, whate'er betide, Nobly on the Christian plan, This is still the surest guide How to be a gentleman.' |

About a year after our arrival in Edinburgh, Townley was seated one day midway up the beautiful mountain called Arthur's Seat. It was early summer; the sky was blue and almost cloudless; far beneath, the city of palaces and monuments seemed to sleep in the sunshine; away to the east lay the sea, blue even as the sky itself, except where here and there a cloud shadow passed slowly over its surface. Studded, too, was the sea with many a white sail, and steamers with trailing wreaths of smoke.

The noise of city life, faint and far, fell on the ear with a hum hardly louder than the murmur of the insects and bees that sported among the wild flowers.

Townley would not have been sitting here had he been all by himself, for this Herculean young parson never yet set eye on a hill he meant to climb without going straight to the top of it.

'There is no tiring Townley.' I have often heard father make that remark; and, indeed, it gave in a few words a complete clue to Townley's character.

But to-day my aunt Cecilia was with him, and it was on her account he was resting. They had been sitting for some time in silence.

'It is almost too lovely a day for talking,' she said, at last.

'True; it is a day for thinking and dreaming.'

'I do not imagine, sir, that either thinking or dreaming is very much in your way.'

He turned to her almost sharply.

'Oh, indeed,' he said, 'you hardly gauge my character aright, Miss M'Crimman.'

'No, if you only knew how much I think at times; if you only knew how much I have even dared to dream—'

There was a strange meaning in his looks if not in his words. Did she interpret either aright, I wonder? I know not. Of one thing I am sure, and that is, my friend and tutor was far too noble to seem to take advantage of my aunt's altered circumstances in life to press his suit. He might be her equal some day, at present he was—her brother's guest and domestic.

'Tell me,' she said, interrupting him, 'some of your thoughts; dreams at best are silly.'

He heaved the faintest sigh, and for a few moments appeared bent only on forming an isosceles triangle of pebbles with his cane.

Then he put his fingers in his pocket.

'I wish to show you,' he said, 'a ring.'

'A ring, Mr. Townley! What a curious ring! Silver, set with a ruby heart. Why, this is the ring—the mysterious ring that belonged to the priest, and was found in his box in the vault.'

'No, that is not the ring. The ring is in a safe and under seal. That is but a facsimile. But, Miss M'Crimman, the ring in question did not, I have reason to believe, belong to the priest Stewart, nor was it ever worn by him.'

'How strangely you talk and look, Mr. Townley!'

'Whatever I say to you now, Miss M'Crimman, I wish you to consider sacred.'

The lady laughed, but not lightly.

'Do you think,' she said, 'I can keep a secret?'

'I do, Miss M'Crimman, and I want a friend and occasional adviser.'

'Go on, Mr. Townley. You may depend on me.'

'All we know, or at least all he will tell us of Murdoch's—your nephew's—illness, is that he was frightened at the ruin that night. He did not lead us to infer—for this boy 53 is honest—that the terror partook of the supernatural, but he seemed pleased we did so infer.'

'Yes, Mr. Townley.'

'I watched by his bedside at night, when the fever was at its hottest. I alone listened to his ravings. Such ravings have always, so doctors tell us, a foundation in fact. He mentioned this ring over and over again. He mentioned a vault; he mentioned a name, and starting sometimes from uneasy slumber, prayed the owner of that name to spare him—to shoot him not.'

'And from this you deduce——'

'From this,' said Townley, 'I deduce that poor Murdoch had seen that ring on the left hand of a villain who had threatened to shoot him, for some potent reason or another, that Murdoch had seen that vault open, and that he has been bound down by sacred oath not to reveal what he did see.'

'But oh, Mr. Townley, such oath could not, cannot be binding on the boy. We must——'

'No, we must not, Miss M'Crimman. We must not put pressure on Murdoch at present. We must not treat lightly his honest scruples. You must leave me to work the matter out in my own way. Only, whenever I need your assistance or friendship to aid me, I may ask for it, may I not?'

'Indeed you may, Mr. Townley.'

Her hand lay for one brief moment in his; then they got up silently and resumed their walk.

Both were thinking now.

To-night, before I entered my tower-room study and sat down to continue our strange story, I was leaning over the battlements and gazing admiringly at the beautiful sunset effects among the hills and on the lake, when my aunt came gliding to my side. She always comes in this spirit-like way.

'May I say one word,' she said, 'without interrupting the train of your thoughts?'

'Yes, dear aunt,' I replied; 'speak as you please—say what you will.'

'I have been reading your manuscript, Murdoch, and I think it is high time you should mention that the M'Raes of Strathtoul were in no degree connected with or voluntarily mixed up in the villainy that banished your poor father from Castle Coila.'

'It shall be as you wish,' I said, and then Aunt Cecilia disappeared as silently as she had come.

Aunt is right. Nor can I forget that—despite the long-lasting and unfortunate blood-feud—the Strathtouls were and are our kinsmen. It is due to them to add that they ever acted honourably, truthfully; that there was but one villain, and whatever of villainy was transacted was his. Need I say his name was Duncan M'Rae? A M'Rae of Strathtoul? No; I am glad and proud to say he was not. 55 I even doubt if he had any right or title to the name at all. It may have been but an alias. An alias is often of the greatest use to such a man as this Duncan; so is an alibi at times!

I have already mentioned the school in the glen which my father the chief had built. M'Rae was one of its first teachers. He was undoubtedly clever, and, though he had not come to Coila without a little cloud on his character, his plausibility and his capability prevailed upon my father to give him a chance. There used at that time to be services held in the school on Sunday evenings, to which the most humbly dressed peasant could come. Humble though they were, they invariably brought their mite for the collection. It was dishonesty—even sacrilegious dishonesty—in Duncan to appropriate such moneys to his use, and to falsify the books. It is needless to say he was dismissed, and ever after he bore little good-will to the M'Crimmans of Coila.

He had now to live on his wits. His wits led him to dishonesty of a different sort—he became a noted poacher. His quarrels with the glen-keepers often led to ugly fights and to bloodshed, but never to Duncan's reform. He lived and lodged with old Mawsie. It suited him to do so for several reasons, one of which was that she had, as I have already said, an ill-name, and the keepers were superstitious; besides, her house was but half a mile from a high road, along which a carrier passed once a week on his way to a distant town, and Duncan nearly always had a mysterious parcel for him.

The poacher wanted a safe or store for his ill-gotten game. What better place than the floor of the ruined church? While digging there, to his surprise he had discovered a secret vault or cell; the roof and sides had fallen in, but masons could repair them. Such a place would be invaluable in his craft if it could be kept secret, and he determined it should be. After this, strange lights were said to be seen sometimes by belated travellers 56 flitting among the old graves; twice also a ghost had been met on the hill adjoining—some thing at least that disappeared immediately with eldritch scream.

It was shortly after this that Duncan had imported two men to do what they called 'a bit of honest work.' Duncan had lodged and fed them at Mawsie's; they worked at night, and when they had done the 'honest work,' he took them to Invergowen and shipped them back to Aberdeen.

But the poacher's discovery of the priest's Bible turned his thoughts to a plan of enriching himself far more effectually and speedily than he ever could expect to do by dealing in game without a licence.

At the same time Duncan had found the poor priest's modest store of wine. A less scientific villain would have made short work with this, but the poacher knew better at present than to 'put an enemy in his mouth to steal away his brains;' besides, the vault would look more natural, when afterwards 'discovered,' with a collection of old bottles of wine in it.

To forge an entry on one of the fly-leaves of the book was no difficult task, nor was it difficult to deal with Mawsie so as to secure the end he had in view in the most natural way. Once again his villain-wit showed its ascendency. A person of little acumen would have sought to work upon the old lady's greed—would have tried to bribe her to say this or that, or to swear to anything. But well Duncan knew how treacherous is the aged memory, and yet how easily acted on. He began by talking much about the Le Roi marriage which had taken place when she was a girl. He put words in the old lady's mouth without seeming to do so; he manufactured an artificial memory for her, and neatly fitted it.

'Surely, mother,' he would say, 'you remember the marriage that took place in the chapel at midnight—the rich soldier, you know, Le Roi, and the bonnie M'Crimman lady? You're not so very old as to forget that.' 57

'Heigho! it's a long time ago, ma yhillie og, a long time ago, and I was young.'

'True, but old people remember things that happened when they were young better than more recent events.'

They talked in Gaelic, so I am not giving their exact words.

'Ay, ay, lad—ay, ay! And, now that you mention it, I do remember it well—the lassie M'Crimman and the bonnie, bonnie gentleman.'

'Gave you a guinea—don't you remember?'

'Ay, ay, the dear man!'

'Is this it?' continued Duncan, holding up a golden coin.

Her eyes gloated over the money, her birdlike claw clutched it; she 'crooned' over it, sang to it, rolled it in a morsel of flannel, and put it away in her bosom.

A course of this kind of tuition had a wonderful effect on Mawsie. After the marriage came the vault, and she soon remembered all that. But probably the guinea had more effect than anything else in fixing her mind on the supposed events of the past.

You see, Duncan was a psychologist, and a good one, too. Pity he did not turn his talents to better use.

The poacher's next move was to hurry up to London, and obtain an interview with the chief of Strathtoul's son. He seldom visited Scotland, being an officer of the Guards—a soldier, as his grandfather had been.

Is it any wonder that Duncan M'Rae's plausible story found a ready listener in young Le Roi, or that he was only too happy to pay the poacher a large but reasonable sum for proofs which should place his father in possession of fortune and a fine estate?

The rest was easy. A large coloured sketch was shown to old Mawsie as a portrait of the Le Roi who had been married in the old chapel in her girlhood. It was that of his grandson, who shortly after visited the manse and the ruin. 58

Duncan was successful beyond his utmost expectations. Only 'the wicked flee when no man pursueth' them, and this villain could not feel easy while he remained at home. Two things preyed on his mind—first, the meeting with myself at the ruin; secondly, the loss of his ring. Probably had the two men not interfered that night he would have made short work of me. As for the ring, he blamed his own carelessness for losing it. It was a dead man's ring; would it bring him ill-luck?

So he fled—or departed—put it as you please; but, singular to say, old Mawsie was found dead in her house the day after he had been seen to take his departure from the glen. It was said she had met her death by premeditated violence; but who could have slain the poor old crone, and for what reason? It was more charitable and more reasonable to believe that she had fallen and died where she was found. So the matter had been allowed to rest. What could it matter to Mawsie?

Townley alone had different and less charitable views about the matter. Meanwhile Townley's bird had flown. But everything comes to him who can wait, and—there was no tiring Townley.

A year or two flew by quickly enough. I know what that year or two did for me—it made me a man!

Not so much in stature, perhaps—I was young, barely seventeen—but a man in mind, in desire, in ambition, and in brave resolve. Do not imagine that I had been very happy since leaving Coila; my mind was racked by a thousand conflicting thoughts that often kept me awake at night when all others were sunk in slumber. Something told me that the doings of that night at the ruin had undone our fortunes, and I was bound by solemn promise never to divulge what I had seen or what I knew. A hundred times over I tried to force myself to the belief that the poacher was only a poacher, and not a villain of deeper dye, but all in vain. 59

Time, however, is the edax rerum—the devourer of all things, even of grief and sorrow. Well, I saw my father and mother and Flora happy in their new home, content with their new surroundings, and I began to take heart. But to work I must go. What should I do? What should I be? The questions were answered in a way I had little dreamt of.

One evening, about eight o'clock, while passing along a street in the new town, I noticed well-dressed mechanics and others filing into a hall, where, it was announced, a lecture was to be delivered—

|

'A New Home in the West.' |

Such was the heading of the printed bills. Curiosity led me to enter with others.

I listened entranced. The lecture was a revelation to me. The 'New Home in the West' was the Argentine Republic, and the speaker was brimful of his subject, and brimful to overflowing with the rugged eloquence that goes straight to the heart.

There was wealth untold in the silver republic for those who were healthy, young, and willing to work—riches enough to be had for the digging to buy all Scotland up—riches of grain, of fruit, of spices, of skins and wool and meat—wealth all over the surface of the new home—wealth in the earth and bursting through it—wealth and riches everywhere.

And beauty everywhere too—beauty of scenery, beauty of woods and wild flowers; of forest stream and sunlit skies. Why stay in Scotland when wealth like this was to be had for the gathering? England was a glorious country, but its very over-population rendered it a poor one, and poorer it was growing every day.

|

'Hark! old Ocean's tongue of thunder, Hoarsely calling, bids you speed To the shores he held asunder Only for these times of need. Now, upon his friendly surges Ever, ever roaring "Come," All the sons of hope he urges To a new, a richer home. There, instead of festering alleys, Noisome dirt and gnawing dearth, Sunny hills and smiling valleys Wait to yield the wealth of earth. All she seeks is human labour, Healthy in the open air; All she gives is—every neighbour Wealthy, hale, and happy There!' |

Language like this was to me simply intoxicating. I talked all next day about what I had heard, and when evening came I once more visited the lecture-hall, this time in company with my brothers.

'Oh,' said Donald, as we were returning home, 'that is the sort of work we want.'

'Yes,' cried Dugald the younger; 'and that is the land to go to.'

'You are so young—sixteen and fifteen—I fear I cannot take you with me,' I put in.

Donald stopped short in the street and looked straight in my face.

'So you mean to go, then? And you think you can go without Dugald and me? Young, are we? But won't we grow out of that? We are not town-bred brats. Feel my arm; look at brother's lusty legs! And haven't we both got hearts—the M'Crimman heart? Ho, ho, Murdoch! big as you are, you don't go without Dugald and me!'

'That he sha'n't!' said Dugald, determinedly.

'Come on up to the top of the craig,' I said; 'I want a walk. It is only half-past nine.'

But it was well-nigh eleven before we three brothers had finished castle-building.

Remember, it was not castles in the air, either, we were piling up. We had health, strength, and determination, with a good share of honest ambition; and with these we 61 believed we could gather wealth. The very thoughts of doing so filled me with a joy that was inexpressible. Not that I valued money for itself, but because wealth, if I could but gain it, would enable me to in some measure restore the fortunes of our fallen house.

We first consulted father. It was not difficult to secure his acquiescence to our scheme, and he even told mother that it was unnatural to expect birds to remain always in the parent nest.

I have no space to detail all the outs and ins of our arguments; suffice it to say they were successful, and preparations for our emigration were soon commenced. One stipulation of dear mother's we were obliged to give in to—namely, that Aunt Cecilia should go with us. Aunt was very wise, though very romantic withal—a strange mixture of poetry and common-sense. My father and mother, however, had very great faith in her. Moreover, she had already travelled all by herself half-way over the world. She had therefore the benefit of former experiences. But in every way we were fain to admit that aunt was eminently calculated to be our friend and mentor. She was and is clever. She could talk philosophy to us, even while darning our stockings or seeing after our linen; she could talk half a dozen languages, but she could talk common-sense to the cook as well; she was fitted to mix in the very best society, but she could also mix a salad. She played entrancingly on the harp, sang well, recited Ossian's poems by the league, had a beautiful face, and the heart of a lion, which well became the sister of a chief.