Title: Eyebright: A Story

Author: Susan Coolidge

Release date: November 10, 2008 [eBook #27223]

Most recently updated: January 4, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Adrian Mastronardi, Ruth and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | Lady Jane and Lord Guildford | 1 |

| II. | After School | 18 |

| III. | Mr. Joyce | 43 |

| IV. | A Day with the Shakers | 66 |

| V. | How the Black Dog had his Day | 85 |

| VI. | Changes | 104 |

| VII. | Between the Old Home and the New | 122 |

| VIII. | Causey Island | 143 |

| IX. | Shut up in the Oven | 166 |

| X. | A Long Year in a Short Chapter | 188 |

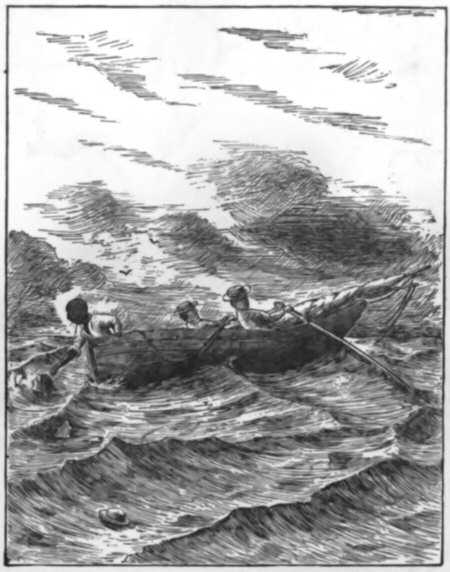

| XI. | A Storm on the Coast | 204 |

| XII. | Transplanted | 226 |

It wanted but five minutes to twelve in Miss Fitch's schoolroom, and a general restlessness showed that her scholars were aware of the fact. Some of the girls had closed their books, and were putting their desks to rights, with a good deal of unnecessary fuss, keeping an eye on the clock meanwhile. The boys wore the air of dogs who see their master coming to untie them; they jumped and quivered, making the benches squeak and rattle, and shifted their feet about on the uncarpeted floor, producing sounds of the kind most trying to a nervous teacher. A general expectation prevailed. Luckily, Miss Fitch was not nervous. She had that best of all gifts for teaching,—calmness; and she understood her pupils and their ways, and had sympathy with them. She knew how hard it is for feet with the dance of youth in them to keep still for three long hours on a June morning; and there was a pleasant, roguish look in her face as she laid her hand on the bell, and, meeting the twenty-two pairs of expectant eyes which were fixed on hers, rang it—dear Miss Fitch—actually a minute and a half before the time.

At the first tinkle, like arrows dismissed from the bow-string, two

girls belonging to the older class jumped from their seats and flew,

ahead of all the rest, into the entry, where hung the hats and caps of

the school, and their dinner-baskets. One seized a pink sun-bonnet from

its nail, the other a Shaker-scoop with a deep green cape; each

possessed herself of a small tin pail, and just as the little crowd

swarmed into the passage, they hurried out on the green, in the middle

of which the schoolhouse stood. It was a very small green, shaped like a

triangle, with half a dozen trees growing upon it; but

"Little things are great to little men,"

you know, and to Miss Fitch's little men and women "the Green" had all the importance and excitement of a park. Each one of the trees which stood upon it possessed a name of its own. Every crotch and branch in them was known to the boys and the most daring among the girls; each had been the scene of games and adventures without number. "The Castle," a low spreading oak with wide, horizontal branches, had been the favorite tree for fights. Half the boys would garrison the boughs, the other half, scrambling from below and clutching and tugging, would take the part of besiegers, and it had been great fun all round. But alas, for that "had been!" Ever since one unlucky day, when Luther Bradley, as King Charles, had been captured five boughs up by Cromwell and his soldiers, and his ankle badly sprained in the process, Miss Fitch had ruled that "The Castle" should be used for fighting purposes no longer. The boys might climb it, but they must not call themselves a garrison, nor pull nor struggle with each other. So the poor oak was shorn of its military glories, and forced to comfort itself by bearing a larger crop of acorns than had been possible during the stirring and warlike times, now for ever ended.

Then there was "The Dove-cote," an easily climbed beech, on which rows of girls might be seen at noon-times roosting like fowls in the sun. And there was "The Falcon's Nest," which produced every year a few small, sour apples, and which Isabella Bright had adopted for her tree. She knew every inch of the way to the top; to climb it was like going up a well-known staircase, and the sensation of sitting there aloft, high in air, on a bough which curved and swung, with another bough exactly fitting her back to lean against, was full of delight and fascination. It was like moving and being at rest all at once; like flying, like escape. The wind seemed to smell differently and more sweetly up there than in lower places. Two or three times lost in fancies as deep as sleep, Isabella had forgotten all about recess and bell, and remained on her perch, swinging and dreaming, till some one was sent to tell her that the arithmetic class had begun. And once, direful day! marked with everlasting black in the calendar of her conscience, being possessed suddenly, as it were, by some idle and tricksy demon, she stayed on after she was called, and, called again, she still stayed; and when, at last, Miss Fitch herself came out and stood beneath the tree, and in her pleasant, mild voice told her to come down, still the naughty girl, secure in her fastness, stayed. And when, at last, Miss Fitch, growing angry, spoke severely and ordered her to descend, Isabella shook the boughs, and sent a shower of hard little apples down on her kind teacher's head. That was dreadful, indeed, and dreadfully did she repent it afterward, for she loved Miss Fitch dearly, and, except for being under the influence of the demon, could never have treated her so. Miss Fitch did not kiss her for a whole month afterward,—that was Isabella's punishment,—and it was many months before she could speak of the affair without feeling her eyes fill swiftly with tears, for Isabella's conscience was tender, and her feelings very quick in those days.

This, however, was eighteen months ago, when she was only ten and a half. She was nearly twelve now, and a good deal taller and wiser. I have introduced her as Isabella, because that was her real name, but the children and everybody always called her Eyebright. "I. Bright" it had been written in the report of her first week at Miss Fitch's school, when she was a little thing not more than six years old. The droll name struck some one's fancy and from that day she was always called Eyebright because of that, and because her eyes were bright. They were gray eyes, large and clear, set in a wide, low forehead, from which a thick mop of hazel-brown hair, with a wavy kink all through it, was combed back, and tied behind with a brown ribbon. Her nose turned up a little; her mouth was rather wide, but it was a smiling, good-tempered mouth; the cheeks were pink and wholesome, and altogether, though not particularly pretty, Eyebright was a pleasant-looking little girl in the eyes of the people who loved her, and they were a good many.

The companion with whom she was walking was Bessie Mather, her most intimate friend just then. Bessie was the daughter of a portrait-painter, who didn't have many portraits to paint, so he was apt to be discouraged, and his family to feel rather poor. Eyebright was not old enough to perceive the inconveniences of being poor. To her there was a great charm in all that goes to the making of pictures. She loved the shining paint-tubes, the palette set with its ring of many-colored dots, and the white canvases; even the smell of oil was pleasant to her, and she often wished that her father, too, had been a painter. When, as once in a great while happened, Bessie asked her to tea, she went with a sort of awe over her mind, and returned in a rapture, to tell her mother that they had had biscuits and apple-sauce for supper, and hadn't done any thing in particular; but she had enjoyed it so much, and it had been so interesting! Mrs. Bright never could understand why biscuits and apple-sauce, which never created any enthusiasm in Eyebright at home, should be so delightful at Bessie Mather's, neither could Eyebright explain it, but so it was. This portrait-painting father was one of Bessie's chief attractions in Eyebright's eyes, but apart from that, she was sweet-tempered, pliable, and affectionate, and—a strong bond in friendship sometimes—she liked to follow and Eyebright to lead; she preferred to listen and Eyebright to talk; so they suited each other exactly. Bessie's hair was dark; she was not quite so tall as Eyebright; but their heights matched very well, as, with arms round each other's waist, they paced up and down "the green," stopping now and then to take a cookie, or a bit of bread and butter, from the dinner-pails which they had set under one of the trees.

Not the least attention did they pay to the rest of the scholars, but Eyebright began at once, as if reading from some book which had been laid aside only a moment before:

"At that moment Lady Jane heard a tap at the door.

"'See who it is, Margaret,' she said.

"Margaret opened the door, and there stood before her astonished eyes a knight clad in shining armor.

"'Who are you, Sir Knight, and wherefore do you come?' she cried, in amaze.

"'I am come to see the Lady Jane Grey,' he replied; 'I have a message for her from Lord Guildford Dudley.'

"'From my noble Guildford,' shrieked Lady Jane, rushing forward.

"'Even so, madam,' replied the knight, bowing profoundly."

Here Eyebright paused for a large bite of bread and butter.

"Go on—please go on," pleaded Bessie, whose mouth happened to be empty just then.

Mumble, mumble,—"the Lady Jane sank back on her couch"—resumed Eyebright, speaking rather thickly by reason of the bread and butter. "She was very pale, and one tear ran slowly down her pearly cheek.

"'What says my lord?' she faintly uttered.

"'He bids me to tell you to hope on, hope ever,' cried the knight; 'the jailer's daughter has promised to steal her father's keys to-night, unbar his door, and let him escape.'

"'Can this be true?' cried Margaret—that's you, you know, Bessie—be ready to catch me. 'Help! my lady is about to faint with joy.'"

Here Eyebright sank on the grass, while Bessie made a dash, and raised her head.

"'Is it? Can it be—true?' murmured the Lady Jane,"—her languid hand meanwhile stealing into the dinner-pail, and producing therefrom a big red apple.

"'It is true—the blessed news is indeed true,' cried the true-hearted Margaret.

"'I feel new life in my veins;' and the Lady Jane sprang to her feet." Here Eyebright scrambled to hers.

"'Come, Margaret,' she cried, 'we most decide in what garb we shall greet my dearest lord when he comes from prison. Don't you think the cram—cram—cramberry velvet, with a net-work of pearls, and,'—what else did they wear, Bessie?"

"Girdles?" ventured Bessie.

"'And a girdle of gems,'" went on Eyebright, easily, and quite regardless of expense. "'Don't you think that will be best, girl?'"

"Oh, Eyebright, would she say 'girl?'" broke in Bessie; "it doesn't sound polite enough for the Lady Jane."

"They all do,—I assure you they do. I can show you the place in Shakespeare. It don't sound so nice, because when people say 'girl,' now, it always means servant-girl, you know; but it was different then; and Lady Jane did say 'my girl.' And you mustn't interrupt so, Bessie, or we shan't get to the execution this recess, and after school I want to play the little Princes in the Tower."

"I won't interrupt any more," said Bessie; "go on."

"'Yes, the cramberry velvet is my choice,'" resumed Eyebright. "'Sir Knight, accept my grateful thanks.'

"He bent low and kissed her fair hand.

"'May naught but good tidings await you ever-more!' he murmured. 'Sorrow should never light on so fair a being.'

"'Ah,' she said, 'sorrow seems my portion. What is rank or riches or ducality to a happy heart!'"

"What did you say? What was that word, Eyebright?"

"Ducality. Lady Jane's father was a duke, you know."

"The knight sighed deeply, and withdrew.

"'Ah, Guildford,' murmured the Lady Jane, laying her head on the shoulder of her beloved Margaret, 'shall I indeed see you once more? It seems too good to be true.'"

Eyebright paused, and bit into her apple with an absorbed expression. She was meditating the next scene in her romance.

"So the next day and the next went by, and still the Lady Jane prayed and waited. Night came at last, and now Lord Guildford might appear at any moment. Margaret dressed her lovely mistress in the velvet robe, twined the pearls in her golden hair, and clasped the jewelled girdle round her slender waist. One snow-white rose was pinned in her bosom. Never had she looked so wildly beautiful. But still Lord Guildford came not. At last a tap at the door was heard.

"'It is he!' cried the Lady Jane, and flew to meet him.

"But alas! it was not he. A stern and gigantic form filled the door-way, and, entering, looked at her with fiery eyes. No, his helmet was shut tight. Wouldn't that be better, Bessie?"

"Oh yes, much better. Do have it shut," said the obliging Bessie.

"His lineaments were hidden by his helmet," resumed Eyebright, correcting herself; "but there was something in his aspect which made her heart thrill with terror.

"'You are looking to see if I am one who will never cross your path again,' he said, in a harsh tone. 'Lady Jane Grey—no! Guildford Dudley has this day expiated his crimes on Tower Hill. His headless trunk is already buried beneath the pavement where traitors lie.'

"'Oh no, no; in mercy unsay the word!' shrieked the Lady Jane, and with one quick sob she sank lifeless to the earth, while Margaret sank beside her. We won't really sink, I think, Bessie, because the grass stains our clothes so, and they get so mussed up. Wealthy says she can't imagine what I do to my things; there was so much grass-green in them that it greened all the water in the tub last wash, she told mother; that was when we played the Coramantic Captive, you know, and I had to keep fainting all the time. We'll just make believe we sank, I guess.

"'Rouse yourself, Lady,' went on the stern warrior 'I have more to communicate. You are my prisoner. Here is the warrant to arrest you, and the soldiers wait outside.'

"One dizzy moment, and Lady Jane rallied the spirit of her race. Her face was deadly pale, but she never looked more lovely.

"'I am ready,' she said, with calm dignity; 'only give me time to breathe one prayer,' and, sinking at the foot of her crucifix, she breathed an Ave Maria in such melodious tones that all present refrained from tears.

"'Lead on,' she murmured.

"We now pass to the scene of execution," proceeded Eyebright, whose greatest gift as a storyteller was her power of getting over difficult parts of the narrative in a sort of inspired, rapid way. "I guess we won't have any trial, Bessie, because trials are so hard, and I don't know exactly how to do them. It was a chill morning in early spring. The sun had hid his face from the awful spectacle. The bell was tolling, the crowd assembled, and the executioner stood leaning on the handle of his dreadful axe. The block was ready!—"

"Oh, Eyebright, it is awful!" interposed Bessie, on the point of tears.

"At last the door of the Tower opened," went on the relentless Eyebright, "and the slender form of the Lady Jane appeared, led by the captain of the guard, and followed by a long procession of monks and soldiers. Her faithful Margaret was by her side, drowned in tears. She was so young, so fair and so sweet that all hearts pitied her, and when she turned to the priest and said, 'Fa-ther, do not we-ep'—"

Eyebright here broke down and began to cry. As for Bessie, she had been sobbing hard, with her handkerchief over her eyes for nearly two minutes.

"'I am go-ing to hea-ven,'" faltered Eyebright, overcome with emotion. "'Thank my cousin, Bloody Mary, for sending me th-ere.'"

"Can you tell me the way to Mr. Bright's house?" said a voice just behind them.

The girls jumped and looked round. In the excitement of the execution, they had wandered, without knowing it, to the far edge of the green, which bordered on the public road. A gentleman on horseback had stopped close beside them, and was looking at them with an amused expression, which changed to one of pity, as the two tear-stained faces met his eye.

"Is any thing the matter? Are you in any trouble?" he asked, anxiously.

"Oh no, sir; not a bit. We are only playing; we are having a splendid time," explained Eyebright.

And then, anxious to change the subject, and also to get back to Lady Jane and her woes, she made haste with the direction for which the stranger had asked.

"Just down there, sir; turn the first street, and it's the fourth house from the corner. No, the fifth,—which is it, Bessie?"

"Let me see," replied Bessie, counting on her fingers. "Mrs. Clapp's, Mr. Potter's, Mr. Wheelwright's,—it's the fourth, Eyebright."

The gentleman thanked them and rode away. As he did so, the bell tinkled at the schoolhouse door.

"Oh, there's that old bell. I don't believe it's time one bit. Miss Fitch must have set the clock forward," declared Eyebright.

Alas, no; Miss Fitch had done nothing of the sort, for at that moment clang went the town-clock, which, as every one knew, kept the best of time, and by which all the clocks and watches in the neighborhood were set.

"Pshaw, it really is!" cried Eyebright. "How short recess seems! Not longer than a minute."

"Not more than half a minute," chimed in Bessie. "Oh, Eyebright, it was too lovely! I hate to go in."

The cheeks and eyelids of the almost executed Lady Jane and her bower maiden were in a sad state of redness when they entered the schoolroom, but nobody took any particular notice of them. Miss Fitch was used to such appearances, and so were the other boys and girls, when Eyebright and Bessie Mather had spent their recess, as they almost always did, in playing the game which they called "acting stories."

our o'clock seemed slow in coming; but it struck at last, as hours always will if we wait long enough; and Miss Fitch dismissed school, after a little bit of Bible-reading and a short prayer. People nowadays are trying to do away with Bibles and prayers in schools, but I think the few words which Miss Fitch said in the Lord's ear every night—and they were very few and simple—sent the little ones away with a sense of the Father's love and nearness which it was good for them to feel. All the girls and some of the boys waited to kiss Miss Fitch for good-night. It had been a pleasant day. Nobody, for a wonder, had received a fault-mark of any kind; nothing had gone wrong, and the children departed with a general bright sense that such days do not often come, and that what remained of this ought to be made the most of.

There were still three hours and a half of precious daylight. What should be done with them?

Eyebright and a knot of girls, whose homes lay in the same direction with hers, walked slowly down the street together. It was a beautiful afternoon, with sunshine of that delicious sort which only June knows how to brew,—warm, but not burning; bright, but not dazzling. It lay over the walk in broad golden patches, broken by soft, purple-blue shadows from the elms, which had just put out their light leaves and looked like fountains of green spray tossed high in air. There was a sweet smell of hyacinths and growing grass and cherry-blossoms; altogether it was not an afternoon to spend in the house, and the children felt the fact.

"I don't want to go home yet," said Molly Prime. "Let's do something pleasant all together instead."

"I wish my swing were ready, and we'd all have a swing in it," said Laura Wheelwright. "Tom said he would put it up to-day, but mother begged him not, because she said I had a cold and would be sure to run in the damp grass and wet my feet. What shall we do? We might go for a walk to Round Pond; will you?"

"No; I'll tell you," burst in Eyebright. "Don't let's do that, because if we do, the big boys will see us and want to come too, and then we sha'n't have any fun. Let's all go into our barn; there's lots of hay up in the loft, and we'll open the big window and make thrones of hay to sit on and tell stories. It'll be just as good as out-doors, and no one will know where we are or come to interrupt us. Don't you think it would be nice? Do come, Laura."

"Delicious! Come along, girls," answered Laura, crumpling her soft sun-bonnet into a heap, and throwing it up into the air, as if it had been a ball.

"Oh, may we come too?" pleaded little Tom and Rosy Bury.

"No, you can't," answered their sister, Kitty, sharply. "You'd be tumbling down and getting frightened, and all sorts of things. You'd better run right home by yourselves."

The little ones were silent, but they looked anxiously at Eyebright.

"I think they might come, Kitty," she said. "They're almost always good, and there's nothing in the loft to hurt them. Yes; they can come."

"Oh, very well, if you want the bother of them. I'm sure I don't mind," replied Kitty.

Then they all ran into the barn. The eight pairs of double-soled boots clattered on the stairs like a sudden hail-storm on a roof. Brindle, old Charley, and a strange horse who seemed to be visiting them, who were munching their evening hay, raised their heads, astonished; while a furtive rustle from some dim corner in the loft showed that Mrs. Top-knot or Mrs. Cochin-China, hidden away there, heard too, and did not like the sound at all.

"Oh, isn't this lovely!" cried Kitty Bury, kicking the fine hay before her till it rose in clouds. "Barns are so nice, I think."

"Yes, but don't kick that way," said Romaine Smith, choking and sneezing. "Oh dear, I shall smother. Eyebright, please open the window. Quick, I am strangling."

Eyebright, who was sneezing too, made haste to undo the rusty hook, and swing the big wooden shutter back against the outside wall of the barn. It made an enormous square opening, which seemed to let in all out-doors at once. Dark places grew light, the soft pure air, glad of the chance, flew in to mix with the sweet, heavy smell of the dried grasses; it was as good as being out-doors, as Eyebright had said.

The girls pulled little heaps of hay together for seats, and ranged themselves in a half-circle round the window, with Mr. Bright's orchard, pink and white with fruit blossoms, underneath them; and beyond that, between Mr. Bury's house and barn, a glimpse of valley and blue river, and the long range of wooded hills on the opposite bank. It was a charming out-look, and though the children could not have put into words what pleased them, they all liked it, and were the happier for its being there.

"Now we're ready. Who will tell the first story?" asked Molly Prime, briskly.

"I'll tell the first," said Eyebright, always ready to take the lead. "It's a splendid story. I read it in a book. Once upon a time, long, long ago, there was a little tailor, who was very good, and his name was Hans. He lived all alone in his little house, and had to work very hard because he was poor. One day as he sat sewing away, some one knocked at the door.

"'Come in,' said Hans, and an old, old man came in. He was wrapped up in a cloak, and looked very cold and tired.

"'Please may I warm myself by your fire?' he said.

"'Why of course you may,'—said good little Hans. 'A warm at the fire costs nothing, and you are welcome.'

"So the old man sat down and warmed himself.

"'Have you come a long way to-day?' Hans said.

"'Yes,' said the old man,—'a long, long way. And I'm ever so cold and hungry.'

"'Poor old fellow,' thought Hans. 'I wish I had something for him to eat; but I haven't, because there is nothing for my own dinner except a piece of bread and a cup of milk.' But then he thought, 'I can do with a little less for once. I'll give the old man half of that.' So he broke the bread in two, and poured half the milk into another cup, and gave them to the old man, who thanked him, and ate it up. But he still looked so hungry, that Hans thought, 'Poor fellow, he is a great deal older than I. I can go without a dinner for once, and I'll give him the rest.' Wasn't that good of Hans?"

"Yes, very good," replied the children, beginning to get interested.

"When the old man had eaten up all the bread and milk, he looked much better. And he got up to go, and said, 'You have been very good, and given me all your own dinner. I wish I had something to give you in return, but I have only got this,' and he took from under his cloak a shabby, old coffee-mill—the shabbiest old thing you ever saw, all cut up with jack-knives, you know, and scratched with pins, with ink-spots on it,"—Eyebright, drawing on her imagination for shabby particulars, was thinking, you see, of her desk at school, which certainly was shabby.

"Hans could hardly keep from laughing; but the old man said severely, 'Don't smile. This mill is better than it looks. It is a magic mill. Whenever you want any thing, you have only to give the handle one turn, and say, "Little mill, grind so and so, open sesame," and, no matter what it is, the mill will begin of itself and grind it for you. Then when you have enough, you must say, "Little mill, stop grinding, Abracadabra," and it will stop. Good-by,' and before Hans could say a word, the old man hurried out of the door and was gone, leaving the queer old mill behind him.

"Of course Hans thought he must be crazy."

"I should have thought so," said Bessie Mather, who was cuddled in the hay close to Eyebright.

"Well, he wasn't! Hans at first thought he would throw the mill away, it looked so dirty and horrid, but then he thought, 'I might as well try it. Let me see, what do I want most at this moment? why, my dinner to be sure. I gave mine to the old man. I'll ask for a goose—roast goose, with hot buttered rolls and coffee. That's a dinner for a prince, let alone a tailor like me.'

"So he gave the handle a turn, and said to the mill, 'Little mill, grind a fat roast goose, open sesame,'—not believing a bit that it would, you know. And, just think! all of a sudden, the handle began to fly round as fast as the wind, and, in one second, out of the top came a beautiful roast goose, all covered with stuffing and gravy. It came so fast that Hans had to catch hold of its drumsticks and take it in his hand, there wasn't time to fetch a dish. He was so surprised that he stood stock-still, staring at the mill with his mouth open, and the handle went on turning, and another goose began to come out of the top. Then Hans was frightened, for he thought, 'What shall I do with two roast geese at once?' and he shouted loudly, 'Little mill, stop grinding, Abracadabra,' and the mill stopped, and the other goose, which had only began to come out, you see, doubled itself up, and went back again into the inside of the mill as fast as it came.

"Then Hans fetched a pitcher, and he said, 'Little mill, grind hot coffee with cream and sugar,' and immediately a stream of coffee came pouring out, till the pitcher was full. Then he ground some delicious rolls and butter, and then he set the mill on his shelf, and danced about the shop for joy.

"'Hans,' he said, 'your fortune is made.'

"And so it was. Because, you know, if people came and asked, 'How soon could you make me a coat?' Hans just had to answer, 'Why, to-morrow of course;' and then, when they were gone, he would go to the mill, and say, 'Little mill, grind a coat to fit Mr. Jones,' and there it would be. The coats all fitted splendidly and wore twice as long as other coats, and all the town said that Hans was the best tailor that ever was, and they all came to him for things, and he got very rich and took a big shop. But he was just as kind to poor people as ever, and the mill did every thing he wanted. Wasn't it nice?"

"I wish there really was a mill like that; I know what I would grind," said Romaine.

"Well, what would you, Romy?"

"A guitar with a blue ribbon, like my cousin Clara Cunningham's. She puts the ribbon round her neck and sings, and it's just lovely."

"But you don't know how to play, do you?" inquired Molly.

"No, but afterwards I'd grind a big music-box, and just as I began to play—no, to pretend to play—I'd set it off, and it would sound as if I was playing."

"Pshaw, I'd grind something a great deal better than that," cried Kitty. "I'd grind a real piano, and I'd learn to play on it my own self. I wouldn't have any old make-believe music-boxes to play for me."

"You never saw a guitar, I guess," rejoined Romaine, pouting, "or you wouldn't think so."

"I'd grind a kitten," put in Rosy, "a white one, just like my Snowdrop. Snowdrop has runned away. I don't know where she is."

"How funny she'd look, coming out of the coffee-mill, mewing and purring," said Eyebright. "Now stop telling what you'd grind, and let me go on. Hans had a neighbor, a very bad man, whose name was Carl. When he saw how rich Hans was getting to be, he became very enverous."

"Very what?"

"Enverous. He didn't like it, you know."

"Don't you mean envious?" said Molly Prime.

"Yes, didn't I say so? Mother says I mispronounce awfully, and it's because I read so much to myself. I meant enver—envious, of course. Well,—Carl noticed that every day when people had gone home to their dinners, Hans shut his door, and stayed alone for an hour, and didn't let anybody come in. This made him suspect something. So one day he bored a little round hole in the back door of Hans' house, and he sat down and put his eye to it, and thought, 'Here I stay, if it is a month, till I find out what that little rascal does when he is alone.'

"So he watched and watched, and for a long time he didn't see any thing but Hans sewing away and waiting on his customers. But at last the clock struck twelve, and then Hans shut his door and locked it tight, and Carl said to himself, 'Ha, ha, now I have him!'

"Hans brought out the coffee-mill, and set it on the table, and Carl heard him say, 'Little mill, grind roast veal, open sesame,' and a nice piece of veal came out of the mill, and fell into a platter which Hans held to catch it, and then Carl snapped his fingers and jumped for joy, and ran off to the wharf, where there was a pirate ship whose captain was a friend of his, and he said to the pirate captain, 'Our fortunes are made.'

"'What do you mean?" asked the pirate.

"'I mean,' said Carl, 'that that little villain, Hans the tailor, has got a fairy mill which grinds every thing he asks for, and I know where he keeps it, and what he says to make it grind, and if you will go shares, I'll steal it this very night, and we'll sail off to a desert island, and there we'll grind gold and grind gold till we are as rich as all the people in the world put together. What do you say to that?'

"So the pirate captain was delighted, of course, because you know that's all that pirates want, just to get gold, and he said 'Yes,' and that very night, when Hans was asleep, Carl crept in, stole the mill, ran to the wharf, and he and the pirate captain sailed away, and Hans never saw his mill again."

"Oh, what a shame! Poor little Hans," cried the children.

"Well, it didn't make so much matter," explained Eyebright, comforting them, "because Hans by this time had got to be so well known, and people liked him so much, that he kept on getting richer and richer, and was always kind to the poor, and happy, so he didn't miss his mill much. The pirate ship sailed and sailed, and by and by, when they were 'way out at sea, the captain said to Carl, 'Suppose we try the mill, and see if it is really as good as you think.'

"'Very well,' said Carl, 'what shall we grind?'

"'We won't grind any gold yet,' said the captain, 'because gold is heavy, and we can do it better on the desert island. We'll just grind some little thing now for fun.' Then he called out to the cook, and said, 'Hollo, cook, is there any thing wanting there in your kitchen?'

"'Yes, sir, please,' said the cook, 'we're out of salt; we sailed so quick that I couldn't get any.'

"So Carl fetched the mill, and set it on the cabin table, and said, 'Little mill, grind salt, open sesame.'

"And immediately a stream of beautiful white salt came pouring out, till two bags which the cook had brought were quite full, and then the captain said, 'That's enough, now stop it.'

"Just at that moment Carl recollected that he didn't know how to stop the Mill."

Here Eyebright made a dramatic pause.

"Oh, what next? What did he do?" cried the others.

"He said all the words he could think of," continued Eyebright; "'Shut, sesame!' and 'Stop!' and 'Please stop!' and 'Don't!' and ever so many others; but he couldn't say the right one, because he didn't know it, you see! So the salt kept pouring on, and it filled all the bags, and boxes, and barrels, and—and—all the—salt-cellars, in the ship, and it ran on to the table, and it ran on to the floor; and the pirate captain caught hold of the handle and tried to keep it from turning; and it gave him such a pinch that he put his fingers into his mouth, and danced with pain. Then he was so mad that he got an axe and chopped the mill in two, to punish it for knocking him. But immediately another handle sprouted out on the half which hadn't any, and that made two mills, and the salt came faster than ever. At last, when it was up to their knees, Carl and the pirate captain ran to the deck to consult what they should do; and, while they were consulting, the mills went on grinding. And the ship got so full, and the salt was so heavy, that, all of a sudden, down they all sank, ship and Carl and the pirates and the mills and all, to the bottom of the sea."

Eyebright came to a full stop. The children drew long breaths.

"Didn't anybody ever get the mill again?" asked Bessie.

"No, never. There they both are at the bottom, grinding away as hard as they can; and that's the reason why the sea is so salt!"

"Is it salt?" asked little Rosy, who never had seen the sea.

"Why, Rosy, of course. Didn't you ever eat codfish? They come out of the sea, and they're just as salt as salt can be," said Tom, who was about a year older than Rosy.

"Now, Molly, you tell one," said Eyebright. "Tell us that one which your grandma told you,—the story about the Indian. Don't you recollect?"

"Oh, yes; the one I told you that day in the pasture. It's a true story, too, every bit of it. My grandma knew the lady it happened to. It was ever and ever so long ago, when the country was all over woods and Indians, you know, and this lady went to the West to live with her husband. He was a pio-nary,—no, pioneer,—no, missionary,—that was what he was. Missionaries teach poor people and preach, and this one was awfully poor himself, for all the money he had was just a little bit which a church in the East gave him.

"Well, after they had lived at the West for a year, the missionary had to come back, because some of the people said he wasn't orthodox. I don't know what that means. I asked father once, and he said it meant so many things that he didn't think he could explain them all; but ma, she said, it means 'agreeing with the neighbors.' Anyhow, the missionary had to come back to tell the folks that he was orthodox, and his wife and children had to stay behind, in the woods, with wolves and bears and Indians close by.

"The very day after he started, his wife was sitting by the fire with her baby in her lap, when the door opened, and a great, enormous Indian walked in and straight up to her.

"I guess she was frightened; don't you?

"'He gone?' asked the Indian in broken English.

"'Yes,' she said.

"Then the Indian held out his hands and said,—'Pappoose. Give.'"

"Oh, my!" cried Romaine. "I'd have screamed right out."

"Well, the lady didn't," continued Molly. "What was the use? There wasn't any one to scream to, you know. Beside, she thought perhaps the Indian was trying her to see if she trusted him. So she let him take the child, and he marched away with it, not saying another word.

"All that night, and all next day, she watched and waited, but he did not come back. She began to think all sorts of dreadful things,—that perhaps he had killed the child. But just at sunset he came with the baby in his arms, and the little fellow was dressed like a chief, in a suit of doe-skins which the squaws had made, with cunning little moccasins on his feet and a feather stuck in his hair. The Indian put him in his mother's lap, and said,—

"'Now red man know white squaw friend, for she not afraid give child.'

"And after that, all the time her husband was gone, the Indians brought venison and game, and were real kind to the lady. Wasn't it nice?"

The children drew long breaths of relief.

"I don't think I could have been so brave," declared Kitty.

"Now I'll tell you a story which I made up myself," said Romaine, who was of a sentimental turn. "It's called the Lady and the Barberry Bush.

"Once upon a time, long, long ago, there was a lady who loved a barberry bush, because its berries were so pretty, and tasted so nice and sour. She used to water it, and come at evening to lay her snow-white hand upon its leaves."

"Didn't they prick?" inquired Molly, who was as practical as Romaine was sentimental.

"No, of course they didn't prick, because the barberry bush was enchanted, you know. Nobody else cared for barberry bushes except the lady. All the rest liked roses and honeysuckles best, and the poor barberry was very glad when it saw the lady coming. At last, one night, when she was watering it, it spoke, and it said,—'The hour of deliverance has arrived. Lady, behold in me a Prince and your lover!' and it changed into a beautiful knight with barberries in his helmet, and knelt at her feet, and they were very happy for ever after."

"Oh, how short!" complained the rest. "Eyebright's was a great deal longer."

"Yes, but she read hers in a book, you know. I made mine up, all myself."

"I'll tell you a 'tory now," broke in little Rosy. "It's a nice 'tory,—a real nice one. Once there was a little girl, and she wanted some pie. She wanted some weal wich pie. And her mother whipped her because she wanted the weal wich pie. Then she kied. And her mother whipped her. Then she kied again. And her mother whipped her again. And the wich pie made her sick. And she died. She couldn't det well, 'cause the dottor he didn't come. He couldn't come. There wasn't any dottor. He was eated up by tigers. Isn't that a nice 'tory?"

The girls laughed so hard over Rosy's story that, much abashed, she hid her face in Kitty's lap, and wouldn't raise it for a long time. Eyebright tried to comfort her.

"It's a real nice story," she said. "The nicest of all. I'm so glad you came, Rosy, else you wouldn't have told it to us."

"Did you hear me tell how the dottor was eated up by tigers?" asked Rosy, peeping with one eye from out of the protection of Kitty's apron.

"Yes, indeed. That was splendid."

"I made that up!" said Rosy, triumphantly revealing her whole face, joyful again, and bright as a full moon.

"Who'll be next?" asked Eyebright.

"I will," said Laura. "Listen now, for it's going to be perfectly awful, I can tell you. It's about robbers."

As she spoke these words, Laura lowered her voice, into a sort of half-groan, half-whisper.

"There was once a girl who lived all alone by herself, with just one Newfoundland dog for company. He wasn't a big Newfoundland,—he was pretty small. One night, when it was all dark and she was just going to sleep, she heard a rustle underneath her bed."

The children had drawn closer together since Laura began, and at this point Romaine gave a loud shriek.

"What was that?" she asked.

All held their breaths. The loft was getting a little dusky now, and sure enough, an unmistakable rustle was heard among the hay in a distant corner!

"This loft would be a very bad place for a robber," said Eyebright, in a voice which trembled considerably, though she tried to keep it steady. "A robber wouldn't have much chance with all our men down below. James, you know, girls, and Samuel and John."

"Yes,—and Benjamin and Charles," chimed in the quick-witted Molly; "and your father, Eyebright, and Henry,—all down there in the barn."

While they recited this formidable list, the little geese were staring with wide-open, affrighted eyes into the corner where the rustle had been heard.

"And,—" continued Eyebright, her voice trembling more than ever, "they have all got pitchforks, you know, and guns, and—oh, mercy! what was that? The hay moved, girls, it did move, I saw it!"

All scrambled to their feet prepared to fly, but before any one could start, the hay in the corner parted, and, cackling and screaming, out flew Mrs. Top-knot, tired of her hidden nest, or of the story-telling, and resolved on escape. Eyebright ran after, and shoo-ed her downstairs. Then she came back laughing, and said,—

"How silly we were! Go on, Laura."

But the nerves of the party were too shaky still to enjoy robber-stories, and Eyebright, perceiving this, made a diversion.

"I know what we all want," she said; "some apples. Stay here all of you, and I'll run in and get them. I won't be but a minute."

"Mayn't I come too?" asked the inseparable Bessie.

"Yes, do, and you can help me carry 'em. Don't tell any stories while we're gone, girls. Come along, Bess."

Wealthy happened to be in the buttery, skimming cream, so no one spied them as they ran through the kitchen and down the cellar stairs. The cellar was a very large one. In fact, there were half a dozen cellars opening one into the other, like the rooms of a house. Wood and coal were kept in some of them, in others vegetables, and there was a swinging shelf where stood Wealthy's cold meat, and odds and ends of food. All the cellars were dark at this hour of the afternoon, very dark, and Bessie held Eyebright's hand tight, as, with the ease of one who knew the way perfectly, she sped toward the apple-room.

In the blackest corner of all, Eyebright paused, fumbled a little on an almost invisible shelf with a jar which had a lid and clattered, and then handed to her friend a dark something whose smell and taste showed it to be a pickled butternut.

"Wealthy keeps her pickles here," she said, "and she lets me take one now and then, because I helped to prick the butternuts when she made 'em. I got my fingers awfully stained too. It didn't come off for almost a month. Aren't they good?"

"Perfectly splendid!" replied Bessie, as her teeth met in the spicy acid oval. "I do think butternut pickles are just too lovely!"

The apple-room had a small window in it, so it was not so dark as the other cellars. Eyebright went straight to a particular barrel.

"These are the best ones that are left," she said. "They are those spotty russets which you said you liked, Bessie. Now, you take four and I'll take four. That'll make just one apiece for each of us."

"How horrid it would be," said Bessie, as the two went upstairs again with the apples in their aprons,—"how horrid it would be if a hand should suddenly come through the steps and catch hold of our ankles."

"Good gracious, Bessie Mather!" cried Eyebright, whose vivid imagination represented to her at once precisely how the hand on her ankle would feel, "I wish you wouldn't say such things,—at least till we're safely up," she added.

Another moment, and they were safely up and in the kitchen. Alas, Wealthy caught sight of them.

"Eyebright," she called after them, "tea will be ready in ten minutes. Come in and have your hair brushed and your face washed."

"Why, Wealthy Judson, what an idea! It's only twenty minutes past five."

"There's a gentleman to tea to-night, and your pa wants it early, so's he can get off by six," replied Wealthy. "I'm just wetting the tea now. Don't argue, Eyebright, but come at once."

"I've got to go out to the barn for one minute, anyhow," cried Eyebright, impatiently, and she and Bessie flashed out of the door and across the yard before Wealthy could say another word.

"It's too bad," she said, rushing upstairs into the loft and beginning to distribute the apples. "That old tea of ours is early to-night, and Wealthy says I must come in. I'm so sorry now that I went for the apples at all, because if I hadn't I shouldn't have known that tea was early, and then I needn't have gone! We were having such a nice time! Can't you all stay till I've done tea? I'll hurry!"

But the loft, with its rustles and dark corners, was not to be thought of for a moment without Eyebright's presence and protection.

"Oh, no, we couldn't possibly; we must go home," the children said, and down the stairs they all rushed.

Brindle and old Charley and the strange horse raised their heads and stared as the little cavalcade trooped by their stalls. Perhaps they were wondering that there was so much less laughing and talking than when it went up. They did not know, you see, about the "perfectly awful" robber story, or the mysterious rustle, or how dreadfully Mrs. Top-knot in the dark corner had frightened the merry little crowd.

ealthy was waiting at the kitchen-door, and pounced on Eyebright the moment she appeared. I want you to know Wealthy, so I must tell you about her. She was very tall and very bony. Her hair, which was black streaked with gray, was combed straight, and twisted round a hair-pin, so as to make a tight, solid knot, about the size of a half-dollar, on the back of her head. Her face was kind, but such a very queer face that persons who were not used to it were a good while in finding out the kindness. It was square and wrinkled, with small eyes, a wide mouth, and a nose that was almost flat, as if some one had given it a knock when Wealthy was a baby, and driven it in. She always wore dark cotton gowns and aprons, as clean as clean could be, but made after the pattern of Mrs. Japhet's in the Noah's arks,—straight up and straight down, with almost no folds, so as to use as little material as possible. She had lived in the house ever since Eyebright was a baby, and looked upon her almost as her own child,—to be scolded, petted, ordered about, and generally taken care of.

Eyebright could not remember any time in her life when her mother was not ill. She found it hard to believe that mamma ever had been young and active, and able to go about and walk and do the things which other people did. Eyebright's very first recollections of her were of a pale, ailing person always in bed or on the sofa, complaining of headache and backache, and general misery,—coming downstairs once or twice in a year perhaps, and even then being the worse for it. The room in which she spent her life had a close, dull smell of medicines about it, and Eyebright went past its door and down the entry on tiptoe, hushing her footsteps without being aware that she did so, so fixed was the habit. She was so well and strong herself that it was not easy for her to understand what sickness is, or what it needs; but her sympathies were quick, and though it was not hard to forget her mother and be happy when she was rioting out-of-doors with the other children, she never saw her without feeling pity and affection, and a wish that she could do something to please or to make her feel better.

Tea was so nearly ready that Wealthy would not let Eyebright go upstairs, but carried her instead into a small bedroom, opening from the kitchen, where she herself slept. It was a little place, bare enough, but very neat and clean, as all things belonging to Wealthy were sure to be. Then, she washed Eyebright's face and hands, and brushed her hair, retying the brown bow, crimping with her fingers the ruffle round Eyebright's neck, and putting on a fresh white apron to conceal the ravages of play in the school frock. Eyebright was quite able to wash her own face, but Wealthy was not willing yet to think so; she liked to do it herself, and Eyebright cared too little about the matter, and was too fond of Wealthy beside, to make any resistance.

When the little girl was quite neat and tidy,—"Go into the sitting-room," said Wealthy, with a final pat. "Tea will be ready in a few minutes. Your pa is in a hurry for it."

So Eyebright went slowly through the kitchen, which looked very bright and attractive with its crackling fire and the sunlight streaming through its open door, and which smelt delightfully of ham and eggs and new biscuit,—and down the narrow, dark passage, on one side of which was the sitting-room, and on the other a parlor, which was hardly ever used by anybody. Wealthy dusted it now and then, and kept her cake in a closet which opened out of it, and there were a mahogany sofa and some chairs in it, upon which nobody ever sat, and some books which nobody ever read, and a small Franklin stove, with brass knobs on top, in which a fire was never lighted, and an odor of mice and varnish, and that was all. The sitting-room on the other side of the entry was much pleasanter. It was a large, square room, wainscoted high with green-painted wood, and had a south window and two westerly ones, so that the sun lay on it all day long. Here and there in the walls, and upon either side of the chimney-piece, were odd, unexpected little cupboards, with small green wooden handles in their doors. The doors fitted so closely that it was hard to tell which was cupboard and which wall; anybody who did not know the room was always a long time in finding out just how many cupboards there were. The one on the left-hand side of the chimney-piece was Eyebright's special cupboard. It had been called hers ever since she was three years old, and had to climb on a chair to open the door. There she kept her treasures of all kinds,—paper dolls and garden seeds, and books, and scraps of silk for patchwork; and the top shelf of all was a sort of hospital for broken toys, too far gone to be played with any longer, but too dear, for old friendship's sake, to be quite thrown away. The furniture of the sitting-room was cherry-wood, dark with age; and between the west windows stood a cherry-wood desk, with shelves above and drawers below, where Mr. Bright kept his papers and did his writing.

He was sitting there now as Eyebright came in, busy over something, and in the rocking-chair beside the fire-place was a gentleman whom she did not recognize at first, but who seemed to know her, for in a minute he smiled and said:—

"Oho! here is my friend of this morning. Is this your little girl, Mr. Bright?"

"Yes," replied papa, from his desk; "she is mine—my only one. That is Mr. Joyce, Eyebright. Go and shake hands with him, my dear."

Eyebright shook hands, blushing and laughing, for now she saw that Mr. Joyce was the gentleman who had interrupted their play at recess. He kept hold of her hand when the shake was over, and began to talk in a very pleasant, kind voice, Eyebright thought.

"I didn't know that you were Mr. Bright's little daughter when I asked the way to his house," he said "Why didn't you tell me? And what was the game you were playing, which you said was so splendid, but which made you cry so hard? I couldn't imagine, and it made me very curious."

"It was only about Lady Jane Grey," answered Eyebright. "I was Lady Jane, and Bessie, she was Margaret; and I was just going to be beheaded when you spoke to us. I always cry when we get to the executions; they are so dreadful."

"Why do you have them, then? I think that's a very sad sort of play for two happy little girls like you. Why not have a nice merry game about men and women who never were executed? Wouldn't it be pleasanter?"

"Oh, no! It isn't half as much fun playing about people who don't have things happen to them," said Eyebright, eagerly. "Once we did, Bessie and I. We played at George and Martha Washington, and it wasn't amusing a bit,—just commanding armies, and standing on platforms to receive company, and cutting down one cherry-tree! We didn't like it at all. Lady Jane Grey is much nicer than that. And I'll tell you another splendid one, 'The Children of the Abbey.' We played it all through from the very beginning chapter, and it took us all our recesses for four weeks. I like long plays so much better than short ones which are done right off."

Mr. Joyce's eyes twinkled a little, and his lips twitched; but he would not smile, because Eyebright was looking straight into his face.

"I don't believe you are too big to sit on my knee," he said; and Eyebright, nothing loth, perched herself on his lap at once. She was such a fearless little thing, so ready to talk and to make friends, that he was mightily taken with her, and she seemed equally attracted by him, and chattered freely as to an old friend.

She told him all about her school, and the girls, and what they did in summer, and what they did in winter, and about Top-knot, and the other chickens, and her dolls,—for Eyebright still played with dolls by fits and starts, and her grand plan for making "a cave" in the garden, in which to keep label-sticks and bits of string and her cherished trowel.

"Won't it be lovely?" she demanded. "Whenever I want any thing, you know, I shall just have to dig a little bit, and take up the shingle which goes over the top of the cave, and put my hand in. Nobody will know that it's there but me. Unless I tell Bessie—," she added, remembering that almost always she did tell Bessie.

Mr. Joyce privately feared that the trowel would become very rusty, and Eyebright's cave be apt to fill with water when the weather was wet; but he would not spoil her pleasure by making these objections. Instead, he talked to her about his home, which was in Vermont, among the Green Mountains, and his wife, whom he called "mother," and his son, Charley, who was a year or two older than Eyebright, and a great pet with his father, evidently.

"I wish you could know Charley," he said; "you are just the sort of girl he would like, and he and you would have great fun together. Perhaps some day your father'll bring you up to make us a visit."

"That would be very nice," said Eyebright. "But"—shaking her head—"I don't believe it'll ever happen, because papa never does take me away. We can't leave poor mamma, you know. She'd miss us so much."

Here Wealthy brought in supper,—a hearty one, in honor of Mr. Joyce, with ham and eggs, cold beef, warm biscuit, stewed rhubarb, marmalade, and, by way of a second course, flannel cakes, for making which Wealthy had a special gift. Mr. Joyce enjoyed every thing, and made an excellent meal. He was amused to hear Eyebright say, "Do take some more rhubarb, papa. I stewed it my own self, and it's better than it was last time," and to see her arranging her mother's tea neatly on a tray.

"What a droll little pussy that is of yours!" he said to her father, when Eyebright had gone upstairs with the tray. "She seems all imagination, and yet she has a practical turn, too. It's an odd mixture. We don't often get the two things combined in one child."

"No, you don't," replied Mr. Bright. "Sometimes I think she has too much imagination. Her head is stuffed with all sorts of notions picked up out of books, and you'd think, to hear her talk, that she hadn't an idea beyond a fairy-tale. But she has plenty of common sense, too, and is more helpful and considerate than most children of her age. Wealthy says she is really useful to her, and has quite an idea of cooking and housekeeping. I'm puzzled at her myself sometimes. She seems two different children rolled into one."

"Well, if that is the case, I see no need to regret her vivid imagination," replied his friend. "A quick fancy helps people along wonderfully. Imagination is like a big sail. When there's nothing underneath it's risky; but with plenty of ballast to hold the vessel steady, it's an immense advantage and not a danger."

Eyebright came in just then, and as a matter of course went back to her perch upon her new friend's knee.

"Do you know a great many stories?" she asked suggestively.

"I know a good many. I make them up for Charley sometimes."

"I wish you'd tell me one."

"It will have to be a short one then," said Mr. Joyce, glancing at his watch. "Bright, will you see about having my horse brought round? I must be off in ten minutes or so." Then, turning to Eyebright,—"I'll tell you about Peter and the Wolves, if you like. That's the shortest story I know."

"Oh, do! I like stories about wolves so much," said Eyebright, settling herself comfortably to listen.

"Little Peter lived with his grandmother in a wood," began Mr. Joyce in a prompt way, as of one who has a good deal of business to get through in brief time.

"They lived all alone. He hadn't any other boys to play with, but once in a great while his grandmother let him go to the other side of the wood, where some boys lived, and play with them. Peter was glad when his grandmother said he might go.

"One day in the autumn, he said: 'Grandmother, may I go and see William and Jack?' Those were the names of the other boys.

"'Yes,' she said, 'you can go, if you will promise to come home at four o'clock. It gets dark early, and I am afraid to have you in the wood later than that.'

"So Peter promised. He had a nice time with William and Jack, and at four o'clock he started to go home; for he was a boy of his word.

"As he went along, suddenly, on the path before him, he saw a most beautiful gray squirrel, with a long bushy tail.

"'Oh, you beauty!' cried Peter. 'I must catch you and carry you home to grandmother.'

"Now, this was humbug in Peter, because grandmother did not care a bit about gray squirrels. But Peter did.

"So Peter ran to catch the squirrel, and the squirrel ran, too. He did not go very fast, but kept just out of reach. More than once, Peter thought he had laid hold of him, but the cunning squirrel always slipped through his fingers.

"At last the squirrel darted up into a thick tree, where Peter could not see him any more. Then Peter began to think of going home. To his surprise it was almost dark. He had been running so hard that he had not noticed this before, nor which way he had come, and when he looked about him, he saw that he had lost his way.

"This was bad enough, but worse happened; for, pretty soon, as he plodded on, trying to guess which way he ought to go, he heard a long, low howl far away in the wood,—the howl of a wolf. Peter had heard wolves howl before, and he knew perfectly well what the sound was. He began to run, and he ran and ran, but the howl grew louder, and was joined by more howls, and they sounded nearer every minute, and Peter knew that a whole pack of wolves was after him. Wolves can run much faster than little boys, you know. They had almost caught Peter, when he saw—"

Mr. Joyce paused to enjoy Eyebright's eyes, which had grown as round as saucers in her excitement.

"Oh, go on!" she cried, breathlessly.

"—when he saw a big hollow tree with a hole in one side. There was not a moment to spare; the hole was just big enough for him to get into; and in one second he had scrambled through and was inside the tree. There were some large pieces of bark lying inside, and he picked one up and nailed it over the hole with a hammer which he happened to have in his pocket. So there he was, in a safe little house of his own, and the wolves could not get at him at all."

"That was splendid," sighed Eyebright, relieved.

"All night the wolves stayed by the tree, and scratched and howled and tried to get in," continued Mr. Joyce. "By and by the moon rose, and Peter could see them putting their noses through the knotholes in the bark, and smelling at him. But the knotholes were too small, and, smell as they might, they could not get at him. At last, watching his chance he whipped out his jack-knife and cut off the tip of the biggest wolf's nose. Then the wolves howled awfully and ran away, and Peter put the nose-tip in his pocket, and lay down and went to sleep."

"Oh, how funny!" cried Eyebright, delighted. "What came next?"

"Morning came next, and he got out of the tree and ran home. His poor grandmother had been frightened almost to death, and had not slept a wink all night long; she hugged and kissed Peter for half an hour and then hurried to cook him a hot breakfast. That's all the story,—only, when Peter grew to be a man, he had the tip of the wolf's nose set as a breast pin, and he always wore it."

Here Mr. Joyce set Eyebright down, and rose from his chair, for he heard his horse's hoofs under the window.

"Oh, do tell me about the breast-pin before you go!" cried Eyebright. "Did he really wear it? How funny! Was it set in gold, or how?"

"I shall have to keep the description of the breast-pin till we meet again," replied Mr. Joyce. "My dear," and he stooped and kissed her, "I wish I had a little girl at home just like you. Charley would like it too. I shall tell him about you. And if you ever meet, you will be friends, I am sure."

Eyebright sat on the door-steps and watched him ride down the street. The sun was just setting, and all the western sky was flushed with pink, the very color of a rosy sea-shell.

"Mr. Joyce is the nicest man that ever came here, I think," she said to Wealthy, who passed through the hall with her hands full of tea-things. "He told me a lovely story about wolves. I'll tell it to you when you put me to bed, if you like. He's the nicest man I ever saw."

"Nicer than Mr. Porter?" asked Wealthy, grimly, walking down the hall.

Eyebright blushed and made no answer. Mr. Porter was a sore subject, though she was only six years old when she knew him, and had never seen him since.

He was a young man who for one summer had rented a vacant room in Miss Fitch's school building. He took a great fancy to Eyebright, who was a little girl then, and he used to play with her, and carry her about the green in his arms. Several times he promised her a doll, which he said he would fetch when he went home. At last, he went home and came back, but no doll appeared and whenever Eyebright asked after it, he replied that it was "in his trunk."

One day, he carelessly left open the door of his room and Eyebright, peeping in, spied it, and saw that his trunk was unlocked. Now was her chance, she thought, and, without consulting anybody, she went in, resolved to find the doll for herself.

Into the trunk she dived. It was full of things, all of which she pulled out and threw upon the floor, which had no carpet, and was pretty dusty. Boots, and shirts, and books, and blacking-bottles, and papers,—all were dumped one on top of the other; but though she went to the very bottom, no doll was to be found, and she trotted away, almost crying with disappointment, and leaving the things just as they lay, on the floor.

Mr. Porter did not like it at all, when he found his property in this condition, and Miss Fitch punished Eyebright, and Wealthy scolded hard; but Eyebright never could be made to see that she had done any thing naughty.

"He's a wicked man, and he didn't tell the trufe," was all she would say. Wealthy was deeply shocked at the affair, and never let Eyebright forget it, so that even now, after six years had passed, the mention of Mr. Porter's name made her feel uncomfortable. She left the door-step presently, and went upstairs to her mother's room, where she usually spent the last half-hour before going to bed.

It was one of Mrs. Bright's better days, and she was lying on the sofa. She was a pretty little woman still, though thin and faded, and had a gentle, helpless manner, which made people want to pet her, as they might a child. The room seemed very warm and close after the fresh door-step, and Eyebright thought, as she had thought many times before, "How I wish that mother liked to have her window open!" But she did not say so. "Was your tea nice, mamma?" she asked, a little doubtfully, for Mrs. Bright was hard to please with food, probably because her appetite was so fickle.

"Pretty good," her mother answered; "my egg was too hard, and I don't like quite so much sugar in rhubarb, but it did very well. What have you been about all day, Eyebright?"

"Nothing particular, mamma. School, you know; and after school, some of the girls came into our hayloft and told stories, and we had such a nice time. Then Mr. Joyce was here to tea. He's a real nice man, mamma. I wish you had seen him."

"How was he nice? It seems to me you didn't see enough of him to judge," said her mother.

"Why, mamma, I can always tell right away if people are nice or not. Can't you? Couldn't you, when you were well, I mean?"

"I don't think much of that sort of judging," said Mrs. Bright, languidly. "It takes a long time to find out what people really are,—years."

"Why, mamma!" cried Eyebright, with wide-open eyes. "I couldn't know but just two or three people in my whole life if I had to take such lots of time to find out! I'd a great deal rather be quick, even if I changed my mind afterward."

"You'll be wiser when you're older," said her mother. "It's time for my medicine now. Will you bring it, Eyebright? It's the third bottle from the corner of the mantel, and there's a tea-cup and spoon on the table."

Poor Mrs. Bright! Her medicine had grown to be the chief interest of her life! The doctor who visited her was one of the old-fashioned kind who believed in big doses and three pills at a time, and something new every week or two; but, in addition to his prescriptions, Mrs. Bright tried all sorts of queer patent physics which people told her of, or which she read about in the newspapers. She also took a great deal of herb tea of different sorts. There was always a little porringer of something steaming away on her stove,—camomile, or boneset, or wormwood, or snakeroot, or tansy, and always a long row of fat bottles with labels on the chimney-piece above it.

Eyebright fetched the medicine and the cup, and her mother measured out the dose.

"I can't help hoping that this is going to do me good," she said. "It's something new which I read about in the 'Evening Chronicle,'—Dr. Bright's Cosmopolitan Febrifuge. It seems to work the most wonderful cures. Mrs. Mulravy, a lady in Pike's Gulch, Idaho, got entirely well of consumptive cancer by taking only two bottles; and a gentleman from Alaska writes that his wife and three children, who were almost dead of cholera collapse and heart-disease, recovered entirely after taking the Febrifuge one month. It's very wonderful."

"I've noticed that those folks who get well in the advertisements always live in Idaho and Alaska and such like places, where people ain't very likely to go a-hunting after them," said Wealthy, who came in just then with a candle.

"Now, Wealthy, how can you say so! Both these cures are certified to by regular doctors. Let me see,—yes,—Dr. Ingham and Dr. H. B. Peters. Here are their names on the bottle!"

"It's easy enough to make up a name or two if you want 'em," muttered Wealthy. Then, seeing that Mrs. Bright looked troubled, she was sorry she had spoken, and made haste to add, "However, the medicine may be first-rate medicine, and if it does you good, Mrs. Bright, we'll crack it up everywhere,—that we will."

Eyebright's bedtime was come. She kissed her mother for good-night with the feeling which she always had, that she must kiss very gently, or some dreadful thing might happen,—her mother break in two, perhaps, or something. Wealthy, who was in rather a severe mood for some reason, undressed her in a sharp, summary way, declined to listen to the wolf story, and went away, taking the candle with her. But there was little need of a candle in Eyebright's room that night, for the shutters stood open, and a bright full moon shone in, making every thing as distinct, almost, as it was in the daytime. She was not a bit sleepy, but she didn't mind being sent to bed, at all, for bedtime often meant to her only a second playtime which she had all to herself. Getting up very softly, so as to make no noise, she crept to the closet, and brought out a big pasteboard box which was full of old ribbons and odds and ends of lace and silk. With these she proceeded to make herself fine; a pink ribbon went round her head, a blue one round her neck, a yellow and a purple round either ankle, and round her waist, over her night-gown a broad red one, very dirty, to serve as a sash. Each wrist was adorned with a bit of cotton edging, and, with a broken fan in her hand, Eyebright climbed into bed again, and putting one pillow on top of the other to make a seat, began to play, telling herself the story in a low, whispering tone.

"I am a Princess," she said; "the most beautiful Princess that ever was. But I didn't know that I was a Princess at all, because a wicked fairy stole me when I was little, and put me in a lonely cottage, and I thought I wasn't any thing but a shepherdess. But one day, as I was feeding my sheep, a ne-cro-answer he came by and he said:—

"'Princess, why don't you have any crown?'

"Then I stared, and said, 'I'm not a Princess.'

"'Oh, but you are,' he said; 'a real Princess.'

"Then I was so surprised you can't think, Bessie.—Oh, I forgot that Bessie wasn't here. And I said, 'I cannot believe such nonsense as that, sir.'

"Then the necroanswer laughed, and he said:—

"'Mount this winged steed, and I will show you your kingdom which you were stolen away from.'

"So I mounted."

Here Eyebright put a pillow over the foot-board of the bed, and climbed upon it, in the attitude of a lady on a side-saddle.

"Oh, how beautiful it is!" she murmured. "How fast we go! I do love horseback."

Dear silly little Eyebright! Riding there in the moonlight, with her scraps of ribbon and her bare feet and her night-gown, she was a fantastic figure, and looked absurd enough to make any one laugh. I laugh, too, and yet I love the little thing, and find it delightful that she should be so easily amused and made happy with small fancies. Imagination is like a sail, as Mr. Joyce had said that evening; but sails are good and useful things sometimes, and carry their owners over deep waters and dark waves, which else might dampen, and drench, and drown.

hree weeks after Mr. Joyce's visit, the long summer vacation began. The children liked school, but none the less did they rejoice over the coming of vacation. It brought a sense of liberty, of long-days-all-their-own-to-do-as-they-liked-with, which it was worth going to school the rest of the year to feel. Each new morning was like a separate beautiful gift, brought and laid in their hands by an invisible somebody, who must be kind and a friend, since he continually did this delightful thing for them.

One hot August afternoon, Eyebright and two or three of her special cronies had gone for coolness to the ice-house, a place which they had used as a playroom before on especially sultry days. It was a large, square underground cave, with a shingled roof set over it, whose eaves rested on the ground. The ice when first put in, filled all the space under the roof, and it was necessary to climb up to reach the top layer; later, ice and ground were on a level, but by August so much ice had been used or had melted away, that a ladder was wanted to help people down to the surface. The girls had left the door a little open, but still the place was dark, and they could only dimly see the tin chest in the corner where Wealthy kept her marketing, and the shapes of two or three yellow crocks which lay half buried, their round lids looking like the caps of droll little drowning Chinamen.

It was so hot outside, that the dullness of the ice was as refreshing as very cold water is to people who have been walking in the sun. The girls drew long breaths of relief as they entered. Such a sharp change from heat to cold is not quite safe, and I imagine Wealthy would probably have had a word to say on the subject, had she spied them going into the ice-house; but Wealthy happened to be looking another way that afternoon, so she did not interfere; and as, strange to say, it harmed nobody that time, we need not discuss the wisdom of the proceeding, only don't any of you who read this go and sit in an ice-house without getting leave from someone wiser than yourselves.

"Oh, this is delightful," said Romaine. "It's just like the North Pole and the Arctic regions which Pa read about in the book. Don't you come here sometimes and play shipwreck and polar bears, Eyebright? I should think you would."

"We did once, but Harry Prime broke a butter-jar, and Wealthy was as mad as hops, and said we must never play here again, and I must never let another boy come into the ice-house. She didn't say we girls mustn't come, though, and I'm glad she didn't; for it's lovely in hot weather, I think."

"I wish we had an ice-house," sighed Kitty Bury, "you do have such lots of nice things, Eyebright, ice-houses and hay-lofts and a great big garret, and a room to yourself; I wish I was an only child."

"I'd rather have some brothers and sisters than all the ice-houses in creation," said Eyebright, who never had agreed with Kitty as to the advantages of being 'only.' "It's a great deal nicer."

"That's because you don't know any thing about it. Brothers and sisters are nice enough sometimes, but other times they're nothing but a plague," snapped Kitty, who seemed out of sorts for some reason or other; "you can't imagine what a bother Sarah Jane is to me. She's always taking my things, and turning my drawers over, and tagging round after me when I don't want her; and if I bolt the door, and try to get a little peace and quiet, she comes and bangs, and says it's her room too, and I've no business to lock her out; and then mother takes her part, and it isn't nice a bit. I would a great deal rather be an only child than have Sarah Jane."

"But don't you have splendid times at night and in the morning? I always thought it must be so nice to wake up and find another girl there ready to play and talk." Eyebright's tone was a little wistful.

"Well, it's nice sometimes," admitted Kitty.

Just then the door at the top of the ladder opened, and a fresh face peeped in.

"Oh, it's Molly Prime," they all cried. "Here we are, Molly, come along."

Molly scrambled down the ladder.

"I guessed where you were," she said. "Wealthy didn't know, so I took care not to say a word to her, but just crept round and looked in. Oh, girls! what do you think is going to happen?—something nice."

"What?"

"Miss Fitch is going to have a picnic and take us to the Shakers."

The Shaker settlement was about ten miles from Tunxet. I am not sure that I have remembered to tell you that Tunxet was the name of the place where Eyebright and the other children lived, but it was, Tunxet Village. They were used to see the stout, sober-looking brethren in their broad-brimmed hats, driving about the place in wagons and selling vegetables, cheese, and apple-butter. But, as it happened, none of the children had ever visited the home of the community, and Molly's news produced a great excitement.

"Goody! goody!" they all cried, "when are we going, Molly, and how did you know?"

"Miss Fitch told father. She came to borrow our big wagon, and Ben to drive, and Pa said she could have it and welcome, because he thinks ever so much of Miss Fitch, and so does mother. We are going on Friday, and we are not to carry any thing to eat, because we're sure to get a splendid dinner over there. Mother says nobody makes such good things as the Shakers do. Won't it be lovely? All the school is going, little ones and all, except Washington Wheeler, and he can't, because he's got the measles."

"Oh, poor little Washington, that's too bad," said Eyebright, "but I'm too glad for any thing that we're going. I always did want to see the Shakers. Wealthy went once, and she told me about it. She says they're the cleanest people in the world, and that you might eat off their kitchen floor."

"Well, if Wealthy says that, you may be sure it is true," put in Laura Wheelwright. "Ma declares she's the cleanest person she ever saw."

"Oh, Wealthy says the Shakers wouldn't call her clean a bit," replied Eyebright. "They'd never eat off her floor, she says."

"Shall we really have to eat off a floor?" inquired Bessie, anxiously.

"Oh, no. That's only a way of saying very clean indeed!" explained Eyebright.

All was expectation from that time onward till Friday came. The children were afraid it might rain, and watched the clouds anxiously. Thursday evening brought a thunder-storm, and many were the groans and sighs; but next morning dawned fresh and fair, with clear sunshine, and dust thoroughly laid on the roads, so that every thing seemed to smile on the excursion. There was but one discord in the general joy, which was that poor little Washington Wheeler must be left behind, with his measles and his disappointment. Eyebright felt so sorry for him that she told Wealthy she was afraid she shouldn't enjoy herself; but bless her! no sooner were they fairly off, than she forgot Washington and every thing else, except the nice time they were having; and neither she nor any one beside noticed the very red and very tear-stained little face, pressed against the pane of the upper window of Mr. Wheeler's house, to watch the big wagon roll through the village.