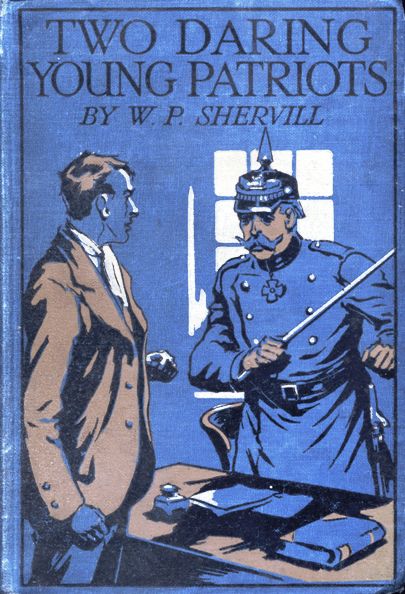

Title: Two Daring Young Patriots; or, Outwitting the Huns

Author: W. P. Shervill

Illustrator: Archibald Webb

Release date: September 17, 2008 [eBook #26645]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Lindy Walsh, Mary Meehan and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

CHAPTER I. Trouble in the Crew

CHAPTER II. The Races

CHAPTER III. Max Durend at Home

CHAPTER IV. The Cataclysm

CHAPTER V. The Fall of Liége

CHAPTER VI. A New Standpoint

CHAPTER VII. A Few Words with M. Schenk

CHAPTER VIII. Treachery!

CHAPTER IX. The Opening of the Struggle

CHAPTER X. Getting Ready for Bigger Things

CHAPTER XI. The Attack on the Power-house

CHAPTER XII. The Attack on the Munition-shops and its Sequel

CHAPTER XIII. The German Counter-stroke

CHAPTER XIV. Schenk at Work Again

CHAPTER XV. The Dash

CHAPTER XVI. In the Ardennes

CHAPTER XVII. Cutting the Line

CHAPTER XVIII. Reprisals

CHAPTER XIX. A Further Blow

CHAPTER XX. Across the Frontier

CHAPTER XXI. The Great Coup

Like a whirlwind they flung themselves upon the hated foe

Both lads began to hurl the great stones upon the German soldiery

A cloth was clapped over the soldier's nose and mouth

"It's all right; we're friends"

The two watchers gave a loud full-throated British cheer

"Here come Benson's!"

The speaker leaned over the edge of the tow-path and watched an eight-oared boat swing swiftly round a bend in the river a hundred yards away and come racing up to the landing-stage.

"Eee—sy all—l!" came in a sing-song from the coxswain, perched, for better sight, half upon the rear canvas, and eight oars instantly feathered the water as their boat slanted swiftly in towards the shore.

"Hold her, Seven."

With almost provoking sloth, after the smartly executed movements already described, Number Seven dug his oar deeply into the water, making up somewhat for his tardiness by the fierceness of the movement. The nose of the boat turned outwards almost with a jerk, and the craft slid in close to and parallel with the landing-stage.

"Seven's got the sulks again, Jones," commented the watcher on shore, a middle schoolboy named Walters, as he eyed the proceedings critically. "His time's bad. It's just as well they get to work to-morrow."

"Yes," assented his companion. "But, you know, it beats me why they didn't put Montgomery at stroke instead of seven. He's a far better oar than Durend—the best in the school—and it would have upset nobody."

"His style may be better," admitted Walters a little reluctantly, "but he hasn't got that tremendous shove off the stretcher that makes the other so useful a man to follow. Besides, he has too much temper to be able to nurse and humour the lame ducks and bring them on as Durend has done."

"Maybe—his temper certainly doesn't look sweet at the moment," replied Jones, gazing with a grim sort of amusement at Montgomery as the latter released his oar from the rowlock and stepped out of the boat, his handsome clean-cut face sadly marred by an undeniably ugly scowl.

"Durend's work isn't showy, but I hear that Benson thinks a lot of it," Walters went on. "It's a pity Monty takes it so badly, for the crew has come along immensely and with ordinary luck ought to make a cert of it."

"Riggers!" the stroke of the crew sang out, and the crew leaned out from the landing-stage and grasped the boat. "Lift!" and the boat was lifted clear of the water and up the slope to the boat-house hard by.

From bow to stern the faces of the crew were smiling and cheerful, albeit streaming with perspiration, as they passed through the admiring knot of their school-fellows assembled to watch them in. All, that is, save Seven, aforesaid, and Stroke, who looked downcast, and whose lips were set firmly as though he found his task no very pleasant one, but had nevertheless made up his mind to see it through.

In the dressing-room Montgomery vented his ill-humour somewhat pettishly, flinging his scarf and sweater anyhow into his locker and his dirty rowing boots violently after them. "I don't care a fig whether we win or lose," he growled. "I'm sick of being hectored by a coach who never was an oar, and a stroke who knows about as much about rowing as my grandmother."

"Shut up, Monty!" replied another member of the crew good-naturedly. "Another week and it will be all over, and we shall be at the Head of the River for the first time—what?"

The thought of Benson's first victory in its history seemed, if anything, to incense Montgomery still more, for he glared angrily at Durend's set face and went on: "It's always my time or my swing that's wrong, too, when everyone used to say that I was the best oar in the school. Bah! it's to cover up his own faults that he's always blaming me. For two pins I'd resign, Durend; and I will, too, if you're not a deal more careful."

"You needn't," replied Durend shortly, but with a significance that was not lost upon those present.

"What d'ye mean?" demanded Montgomery.

"You're no longer in the crew."

"What! You turn me out? I'll take that from Benson, and from no one else, my boy!"

"Mr. Benson has left it to me, and I say you're no longer in the crew," replied Durend coldly, and with no hint of triumph in his voice. He knew, in fact, that his action was probably the death-knell of all the hopes of his crew.

Montgomery's face blazed with passion, and he sprang violently upon Durend and struck fiercely at him. The two boys nearest grasped him and dragged him back, though not before he had left his mark in an angry-looking blotch upon the left cheek of his former chief. Through it all Durend said no word. He merely defended himself, looking, indeed, as though only half his mind were present, his interest in the matter being far out-weighed by concern for the threatened destruction of his beloved crew, the object of his deepest thoughts and hopes for a period of six crowded weeks.

The incident closed, for, Montgomery's first anger over, he saw the foolishness of making so much of losing a seat he had all along affected to despise. The crew dispersed, and soon the affair was the talk of the whole school. Benson's—the favourites—crippled by the loss of their Seven on the very eve of the race! Stroke and Seven at blows! Stroke licked, and no doubt spoiled for the race! The news, soon distorted out of all recognition, provided Hawkesley with matter for gossip such as it had not enjoyed for many a long day.

"Well, Stroke?" asked the Benson's cox, as the two slowly made their way from the boat-house towards the school. "What's to do now? I'm afraid we're done for. Mind," he went on in another tone, "I'm not blaming you. Any other fellow with a spark of spirit in him would have jibbed. But have you counted the cost?"

"Yes, Dale, I've counted the cost, and know what I'm going to do."

"So?"

"Three must come down to Seven and Franklin must come into the boat at Three. If only we had a week of practice before us I should not fear for the result, but to-morrow——"

Stroke's voice died away as he dug his hands deeply into his trousers pockets and walked moodily on. Suddenly he turned to his companion: "After all," he said, "we may stand a chance. If not on the first day or two of the races, then on the last. Rout out Franklin for me, Dale, and tell him what's afoot, and that we row at seven this evening with him at Three. Then tell the others. There'll be no hard work, only a paddle to help Franklin find the swing. One thing—he's fit enough."

"Yes, and I must say we have you to thank for that, old boy. Those runs before breakfast that used to make Monty so savage have done us a good turn by keeping Franklin fit, not to mention the occasional tubbing we have given him."

"Aye, he's not bad; and if the rest of the crew buck up well we may yet do things. Now good-bye, Dale, until seven o'clock! See that every man is ready stripped sharp to time for me, for I must now see Benson, and tell him all my plans."

The further news that Benson's were going out again with their spare man at Three, coming upon the sensational story of the quarrel between Stroke and Seven, spread like wildfire through the school. Every boy who was at all interested in the Eights—and who was not?—made a note of the matter, and promised himself that he would be there and see the fun for himself.

When seven o'clock arrived, therefore, the tow-path in front of Benson's boat-house was thronged with boys; some there in a spirit of foreboding, to see how their own crew shaped after its heavy misfortune, some to rejoice at the evidence they expected to see of the impending discomfiture of a redoubtable foe, some to jeer generally, and others—a few, but the more noisy—in out-and-out hostility to the crew which had turned out from among its number their favourite, Montgomery. So great was the crowd that the crew had almost to push its way through the press, at close quarters with a medley of cheers and groans that did not do the nerves of some of them much good.

The outing was a short one. Mr. Benson, who had coached the crew himself so far as his time permitted, did not put in an appearance, and Durend had the field to himself. All he did was to set an easy stroke, and to leave Dale, as cox, to keep a sharp watch upon the time and swing of Three and Seven. The change naturally upset the rhythm of the crew a little, but not so much as was generally expected. In fact, on the return to the boat-house, cheers predominated, as though others besides themselves had been agreeably surprised.

The Eights week at Hawkesley always stood out prominently from the rest of the year as a kind of landmark. It marked the highest point of the constant struggle between the several Houses into which the school was divided, and all energies were therefore concentrated upon it for weeks in advance. As may have been surmised, the Eights races were not direct contests, with heats, semi-finals, and finals, but bumping races, for the little River Suir would hardly permit of anything else. For a short stretch or two, perhaps, a couple of boats might have raced abreast, but it would not have been possible to have found a reasonably full course for a race to be decided in that way. Consequently the boats were anchored to the shore four boat-lengths behind one another, and by the rules of the game they were required to give chase to one another, and to touch or bump the boat in front to score a win.

A win meant that the victors and vanquished changed places, and the whole essence of the contest was that the stronger crews gradually fought their way forward into the van of the line of boats. There were six Houses to the school, and the same number of crews competed, for the honour of their respective Houses. Six days were allotted to the task, and it was no wonder that the crews had to see to it that they were in first-rate condition, for racing for six days out of seven was bound to try them hard.

The legacy left the Benson crew by their comrades of the year before was the position No. 3 in the line. The position the year before that had been No. 5, so it was not surprising that the Bensonites had great hopes that this year would see them higher still. Cradock's was just in front of them, with Colson's at the Head. Both were strong crews, and so was Johnson's, just behind—too strong, indeed, for Durend to feel very comfortable with an unknown quantity at his back.

The race was timed to start at eleven, and a minute or two before the hour all the crews had taken up their position, stripped and made ready. The crews were too far apart for signals by word of mouth or by pistol to be effective, so a gun was fired from the bank—one discharge "Get ready!" two "Off!" and three—after a lapse of ten minutes—as the "Finish".

"Boom!" went the first gun, and men ceased trying their stretchers or signalling to their friends on shore. A few words of caution from the stroke, and then all was still in tense expectation. The mooring-ropes were slipped, and the boats left free to move slowly forward with the stream.

"Boom!" Simultaneously forty-eight oars dipped and churned the water into foam. Like hounds suddenly unleashed, the six boats leapt forward and began their desperate chase upon the waters of the Suir.

The strongest point of Benson's crew had been its lightning start, and Durend had always counted upon this giving him at least half a length's advantage at the outset. Striking the water at his usual rate, he hoped—almost against hope—that this advantage still remained to him. Less than half a dozen strokes, however, were sufficient to convince him that the hope was a vain one. The perfect swing of the boat was marred by a jar that became more pronounced with every stroke. He knew well enough what it was: it was the new half-trained man, Franklin, vainly trying to keep up the pace of a trained crew.

It was a bitter disappointment, but Durend was not one to let such feelings cloud his judgment, and without a moment's hesitation he let his racing start fall away into a long, steady swing. Victory—for the moment, at any rate—must be left to others, while his crew were brought back once more to the swing and rhythm they had lost.

For some time Durend kept his stroke long and steady, and the boat travelled evenly and well, though at no great pace. By that time Cradock's, in front, were almost lost to sight, but Johnson's, behind, were very much within view, and coming up fast. The situation seemed so critical that Dale at last could contain himself no longer. For some minutes he had been nervously glancing back at the nose of the boat creeping up behind, and wondering when he must forsake his straight course for the forlorn hope of an attempt to elude the bump by a pull at the rudder line.

"Durend, they'll have us, if you don't draw away a little."

Durend nodded. He had not been unmindful of the boat creeping up behind, but he had a problem, and no easy one, to settle. Should he press his crew to the utmost, or should he hold his hand for another time? It was a terribly difficult thing to decide for the best, with Johnson's creeping up and every fibre in him revolting against surrender and calling out for a desperate spurt right up to the end.

Suddenly Durend quickened up. His men were waiting and longing for a spurt and caught it up at once. But again the swing was marred by Franklin's inability to support the terrific pace. After the first stroke or two the boat began to roll heavily, the form and time became ragged, and there was much splashing.

One glance at Dale's agonized face and Durend again allowed his stroke to drop back into its former steady swing, and doggedly, with sternly-set face, plugged away as before, refusing to look again at the crew drawing inexorably up behind. Twice the boats overlapped, but both times Dale managed, by skilful steering, to avoid a bump. The third time no trick of steering could avoid the issue, and the nose of the Johnson boat grated triumphantly along the side of Benson's.

At the touch, both crews ceased rowing. The race for them was ended for that day at least, and they could watch and see how the other crews had fared. But the other races were also over, for the third and last "Boom" rang out within a few seconds of the termination of their own.

Defeat is always hard to bear, and the Benson crew were no exception to the rule. It was obvious to every one of them that they had not been allowed to have their full fling, and angry and discontented thoughts surged into the brains of the disappointed men as they leaned over their oars and tried not to hear the jubilant chatter of those insufferable Johnsonites. Why had Stroke set so wretchedly slow a stroke that defeat was certain? The members of the beaten crew were, for the most part, fresher far than the winning crew. Why had not Stroke given them the opportunity of rowing themselves right out instead of tamely surrendering thus?

No answers to these discontented queries were forthcoming. Durend could have spoken, but would not. Dale might have spoken; for though he knew not the plans of his chief, his position at the rudder enabled him to conjecture a great deal. But he, too, was dumb. So it was that the Benson crew could answer the questions of their distressed friends only by referring them with disparaging shrugs of the shoulders to their worthy Stroke.

Durend had never been a popular boy. He was respected for his steady persistence and his capacity for unlimited hard work, but popular he could not be said to be, even with his crew. He held himself rather aloof, and never really took them into his confidence. He seemed to think that if he did his best as Stroke, both in rowing and in generalship, he had done all that was necessary. His plans, his hopes, and his fears he kept strictly to himself. Why worry his men about them? he reasoned, and in the main, no doubt, he was right, though he carried it much too far. As a consequence the crew, with the possible exception of Dale, were left to conjecture his reasons for all that he did, and in most cases to put a wrong construction upon them.

But, though they growled, they were too sportsmanlike and too loyal to their House to do more, and 11 a.m. next day saw them at their places every bit as eager as before. This time, without a doubt, they told one another, Durend would set them a faster stroke and give them a chance to show the stuff they were made of.

Unhappily they were doomed to fresh disappointment. Twice, indeed, Durend quickened up his stroke, but almost immediately he felt the time and swing of the crew again becoming ragged. In his judgment it was useless to persist in hope of an improvement; so, with the decisiveness that was one of his chief characteristics, he promptly dropped his stroke back into his old rate of striking. His men fretted and fumed behind him, and one or two even went so far as to shout aloud for a spurt. A sharp reprimand was all they got for their trouble, and in high dudgeon they relapsed again into a savage silence. Fortunately, though they saw nothing of the crew ahead, they managed to keep a length of clear water between them and the weak Crawford crew travelling in their wake.

No cheers heralded their return. The doings of Benson's attracted little attention now, for all interest had centred upon the desperate struggles between the three leading boats, Cradock's, Colson's, and Johnson's—for the first two had now changed places. It is almost as hard to be ignored as to be scoffed at, and it was a very sore crew indeed that put their craft upon its rack that day and filed upstairs to the dressing-room of Benson's boat-house.

Self-contained and preoccupied though he was, Durend could not help noticing that his conduct of the races was being severely and adversely commented upon. But he only shrugged his shoulders, hurried on his clothes, and left the building perhaps a little more quickly than usual. Some strokes would have given explanations to their crews, but it never occurred to Durend to do so. Dale followed him from the room.

"See here, Max," he said, as he overtook him, "I think you should know that our fellows are tremendously sick at the poor show we are making. They feel that your stroking of the crew is not giving them a fair chance."

Durend stopped abruptly. "So long as I am stroke, Dale, I shall set the stroke I think proper. I am doing what I think is best for the crew, and shall follow it out until the last race is over—lost or won."

"I know, I know, old man," replied Dale hastily. "But what is your game really? You must know you can't win races with a funereal stroke like that, so what's the good of trying it?"

Durend opened his lips as though about to make an angry reply. Apparently he thought better of it, for he closed them again, and for some minutes walked on in silence. When he spoke it was in the quiet measured tones of one who has thought out his subject and has no doubts in his own mind of the wisdom of his conclusions.

"After six weeks' hard work, Dale, we've managed to get the crew into pretty good form—everybody says so. Is it all to be lightly thrown away? Can we really expect Franklin to keep up the pace of the rest of us without rushing his slide, bucketing, or something of the sort? Can we now?"

Dale, but half convinced, returned to the charge. "Well, I don't know. Something's got to be done. I heard three of the fellows just now whispering something about asking Benson to put Montgomery back in the boat."

"Where?"

Dale hesitated.

"I see. At stroke. Well, I may be prejudiced, but I don't think it would answer, old man. Anyhow, we'll leave all that to Benson, and those three fellows too. Come, Dale, I'm sick of thinking about this, so let's try and talk about something a little more cheerful."

Dale was a light-hearted, cheery fellow enough, and found no difficulty in turning the talk into other and more pleasant topics. The two, though so opposite in point of character and physique, were very good friends. Dale was a slim, lightly-built young fellow of eighteen, with a fair complexion and an open boyish face. He was a general favourite, and, though not athletically inclined, was always ready to assist in acting cox or kindred work. Max Durend was dark-complexioned, somewhat reserved, and of a more thoughtful disposition. He also was eighteen years of age, was of medium height but strongly built, and possessed a great capacity for hard work. As has already been explained, he was not popular, and that may have been partly due to his reserve, and partly to the fact that he was only half English, namely on his mother's side.

The race on the following day was even less exhilarating than the last. Benson's still rowed at their provokingly slow stroke, simply retaining their position at No. 4, while Johnson's and Colson's, after a terrific struggle, changed places. Thus Cradock's remained at the Head with the Johnson and Colson crews second and third.

It needed all Dale's persuasion and plentiful supply of hopeful suppositions (partly derived from his talk with Durend, but mostly made up out of his own head) to keep the Benson crew from breaking out into open revolt. Every day they had finished the race half fresh, and not one of them could see the use of parading up and down the course as though uncertain whether they were in the race or not.

And through it all Mr. Benson just looked grimly on, indifferent, apparently, to all their woes, and said no word save a little—a very little—commendation, no doubt intended to keep them from entering the very last stages of despair. It seemed as though he had given the whole thing up as a bad job, and did not intend to interest himself further in the matter.

Another day came just like the last, and listlessly the dispirited crew turned their oars on the feather and waited for the signal to start. Quite suddenly they woke up to the fact that Stroke was leaning back towards them and speaking.

"Now, you fellows," he was saying in a quiet but tense voice, "I am going to give you a racing start at last. See to it, then, that you pick it up and keep it. Don't forget. Franklin, I rely upon you to do your utmost to keep up with us. Now, boys!"

"Boom!"

There was scarcely a soul about to see Benson's start; nearly everyone was watching the struggles going on ahead, where strong crews were striving in the last days to secure and hold a higher position for the Houses they had been called to represent. So it was that the Benson start passed unnoticed until it dawned upon Colson's, the crew ahead, that the Benson boat had drawn unaccountably nearer. And Benson's, too! It could only be a fluke, and with that conviction Colson's settled down grimly to the task of shaking them off.

But somehow or other it did not seem at all easy to shake them off. In fact, to their dismay, the end of the great spurt saw the gap between the boats no wider. Suddenly, too, Benson's spurted in their turn, and the nose of their boat drew closer at a speed that wellnigh paralysed Colson's.

Indeed, in the Benson boat, the pent-up energies of three days of enforced self-restraint were being let loose in a series of desperate spurts for the mastery. Even Durend could contain himself no longer, and Franklin, though he had not yet reached anything like the form of the rest of the crew, was yet able to do his part in the struggle with a fair measure of success. Within five minutes of the start Benson's had overlapped Colson's, and, almost immediately after, the bump came.

We need not describe the joy and relief in the Benson crew at their unexpected victory—unexpected to all of them, for even Durend, though he had hoped and planned, had not anticipated it so soon. To the rest of the school the whole affair was so unexpected as to be stupefying. Only the most penetrating and experienced observers could give a reason for their sudden recovery, and the remainder explained away the sensational victory by a disparaging reference to the utter weakness of Colson's. Had not Colson's dropped in three days from Head of the River to No. 3, and was that not enough proof of weakness? they argued. Gradually the general view crystallized down to the opinion that Benson's had had their fling, and could hope to make no impression upon the two really strong crews now in front of them.

Nevertheless, though this seemed the general opinion, the following morning found the whole school on the tow-path opposite the Benson boat. No one wanted to see the struggle between Cradock's and Johnson's, but everyone was anxious to see the start of the Benson crew, and to learn whether any fresh surprises were in store for them.

There could be no doubt about the spirit of the crew. Hope and confidence seemed to exude from every pore, and it was clear that for them the week was only just beginning. At the report of the gun, Durend took his men away with a racing start that recalled those they had made before Montgomery left the crew. The form was well kept; even Franklin, who had improved rapidly with every day's work, keeping well in with the swing of the rest of the crew. Dropping the stroke a little soon after the start, Durend led them along with a strong, lively stroke that was soon seen to be gaining them ground slowly, foot by foot, upon their old foe, the Johnson crew. The latter were, however, in no mood to yield an inch if they could help it, and made spurt after spurt in the desperate endeavour to keep well away.

For the first eight or nine minutes of the race, Durend did not allow himself to be flurried into any answering spurt. He knew that he was within reach, and to him that was, for the time, sufficient. His watch was strapped to the stretcher between his feet, and he was carefully measuring the time he could allow Johnson's before calling them to strict account.

It wanted one minute to the time when the finishing gun would boom out before Durend quickened up. His men were waiting in confident expectation for that moment, and answered like one man. From the very feel of the stroke they had known what a reserve of power their stroke and comrades possessed, and they flung themselves into the spurt with all the energy of conscious strength. The boat leapt to the touch, and up and up, nearer and nearer, the nose of their craft crept to the boat ahead.

A hoarse and frantic appeal from the stroke of the Johnson boat, and his men strove to answer and stave off that terrible spurt. But they had spurted too often already, and another and a greater was more than they could bear. Their time became ragged; some splashed and dragged, and the boat was a beaten one before the end came.

It was a thrilling moment when the boats bumped, and the straggling crowds upon the tow-path shouted and yelled with delight and deepest appreciation. Rarely had there been such a race in the school's annals; never one in which the winning crew had thus fought its way up from previous failure and defeat.

After witnessing that achievement, the opinion of the school veered completely round, and everyone confidently predicted that Benson's would win their way to the Head of the River on the following morning. It had now become as clear as noonday to all that the stroke of Benson's had been playing that most difficult of all games, the waiting game. He had held his crew inexorably in until the new man had had time to settle down into his place and catch the form and time of the rest of the crew. Clearly, too, the crew was rowing better every day, and no one believed that Cradock's would be able to keep them off in the full tide of their swing to victory.

This time the opinion of the school was right, and the following day Benson's caught up and bumped Cradock's within three minutes of the start. They had settled down and become a great crew, confident in themselves and even more confident in the power and judgment of their Stroke.

The ovation they received on the return to their boat-house they long remembered. The noisy and enthusiastic tumult was indeed something to remember and be proud of, but to Durend the few words of commendation of Mr. Benson counted for far more.

"Well done, Durend!" he said simply. "I saw you knew your business, and that is why I did not interfere. But even I did not expect so splendid a success. Your men have done well indeed, but it is to you and your fixity of purpose our win is mainly due. I have never known an apparently more hopeless chase; and, to you others, I say that it shows that there is almost nothing that fixity of purpose will not achieve in the long run."

Even more pleasurable were the words of Montgomery, touched with real contrition, as he grasped his old Stroke by the hand and begged his pardon for doubting his ability and power to stroke a crew to victory.

It was only two days after the close of the races when the head master called Durend into his room. He held a slip of paper in his hand, and in rather a grave voice informed the lad that his father was seriously ill. His mother had cabled for his return, and he was to get ready to catch the 2.15 train for Harwich at once.

Max obeyed. His preparations did not take long, and there was still a little time to spare before he needed to start; therefore he sought out Dale to say good-bye.

"But you will come back, of course, Durend?" the erstwhile cox protested, rather struck by the earnestness of his friend's adieu.

"I have a feeling that I shall not, Dale. I cannot help it, but I keep on acting almost unconsciously as though this were the last I shall see of Hawkesley."

"Don't say that, Max. Why should you think your father is so ill as all that? The cablegram doesn't say so. No, I can't take that. You simply must come back. There are lots of things we have promised to do together."

"Can't help it, Dale. But there's one thing you must promise me before I go, and that is, that if I should not come back you will come over and see me. Spend a fortnight at our place at Liége in the summer—eh?"

"You're coming back, old man," replied Dale with determination. "But all the same, I will give you the promise if you like. My uncle and aunt—all the relatives I have—would not mind, I know."

"Thanks, old man—you shall have a good time."

Presently Durend left, and in forty-eight hours he was back in his own home in Belgium on the outskirts of Liége. Prompt as he had been, he found he was too late, for his father had died at the time he was on the boat on the way to Antwerp.

Though not altogether unexpected, the blow was a severe one to Max Durend. He had been very fond of his father, who had latterly treated him more as a chum than anything else, and had talked much to him of his plans for the time when he could assist him in his business. His mother was, of course, even more upset, and though Max and his sister, a girl of twelve, did their best to comfort her, she was quite prostrated for some days.

It was now more than ever necessary that Max should enter his father's business, and, when old and experienced enough, endeavour to carry it on. From the nature of the business it was evident that this was no light task, and would require a great deal of training and an immense amount of hard work if it were to be done successfully. But the prospect of hard work did not appeal Max, and within a fortnight of his father's death he was busy learning the details of the vast business carried on under his name.

Monsieur Durend had been the proprietor of very large iron and steel foundries and workshops in Liége. The business was an immense one, and, beside the manufacture of all kinds of machinery and railway material, worked for its own benefit several coal and iron mines, all of which were in the district or on the outskirts of the town. The business had been a very flourishing one, and had been largely under the personal direction of the proprietor, assisted by his manager, M. Otto Schenk, to whose ability and energy, M. Durend was always ready to acknowledge, it owed much of its success. The latter was now, of course, the mainstay of the business, and it was with every confidence in his ability that Madame Durend appointed him general manager with almost unlimited powers.

M. Schenk was indeed a man to impress people at the outset with a sense of strength and of power to command. He was over six feet in height, broad, but with rather sloping shoulders, and very stoutly built. His head, large itself, almost seemed to merge in a greater neck, and both were held stiffly erect as he glowered at the world through cold and rather protruding eyes, much as a drill-instructor glares at his pupils. He was florid-complexioned, with short, closely-cropped grey hair and a short, stubby, dirty-white moustache. Of his grasp of the affairs of the firm and his business ability generally, people were not so immediately impressed as they were with his power to command, but they invariably learned to appreciate this side of his character in time.

The matter of the direction of the affairs of the firm settled to everyone's satisfaction, the question as to what was to be done with Max came up for discussion.

"I think it will be best, Max, if you go into M. Schenk's office and assist him there," said Madame Durend at last. "You will there pick up the threads of the business, and when you are two or three years older we can consider what we are going to do."

"But, Mother," replied Max, "that was not the way Father learned his business. You have often proudly told me how he used to work as a simple mechanic, going from shop to shop and learning all he could of the practical side of the different processes. How he then bought a small business, extended it and extended it, until it grew to its present size. And the whole secret of his success was that he knew the work so thoroughly from top to bottom that he could depend upon his own knowledge, and needed not to be in the hands of men with more knowledge of detail but vastly less capacity than himself."

"Yes, Max, that is true; but the business is now built up, and is so big that it does not seem necessary for you to go through all that. We have an able manager, and from him you can learn all that you will ever need to know of the work of directing the affairs of the firm."

"I should then never know the work thoroughly. I should always be dependent upon those who had learned the practical side of the work, Mother. Let me spend a year or two in learning it from the bottom. I shall enjoy the work, and shall then feel far more confidence in myself."

Max spoke earnestly, and his mother could see that he was longing to throw himself heart and soul into the work. It was, indeed, the spirit in which he had flung himself into the task of lifting Benson's to the Head of the River over again. Though she had a mother's dislike to the idea of her son's donning blouse and apron and working cheek by jowl with the workmen, she had also a clear perception that it would be a mistake to discourage such energy and thoroughness. She therefore resolved to consult M. Schenk on the morrow, and, if he saw no special objection, to allow Max to have his way.

M. Schenk did see several objections, foremost among which was his view that for the master's son to work like a common workman would tend to lessen the present extremely strict discipline in the workshops. Max, however, scouted such an idea as an unfair reflection on the men, and continued to press his point of view most strenuously. In the end he managed to get his way, and within a week had started work at the firm's smelting furnaces.

This story does not, however, deal with the experiences of Max Durend in learning the various activities of the great manufactory founded by his father. It will, therefore, suffice if we relate one incident that had, in the sequel, an important influence upon his career, an incident, too, that gives an insight into his character and that of the different classes of workmen that would, in the course of time, come under his control.

Max was at the time working at a huge turret lathe in one of the turning-shops. Around him were other workmen similarly engaged. Across the room ran numerous great leather driving-bands, running at high speed and driving the great machines with which the place was filled. Apparently the material of one of the driving-bands was faulty, for it suddenly parted, slipped off the driving-wheels, and became entangled in one of the other bands. As this spun round the loose band caught in the machine close by, wrenched it from its foundation and turned it over on its side, pinning down to the floor the workman attending to it.

The man gave a screech as he was borne down, a screech that was broken off short as the heavy machine fell partly upon his neck and chest, choking him with its fell weight. A straggling cry of alarm was raised by the other workmen who witnessed the tragic occurrence, and many pressed forward to his aid. But the great band which had done the mischief was being carried round and round by the driving-band in which it had become entangled, and was viciously flogging the air and floor all about the stricken man.

Some of the men shouted for the engines to be stopped, others ran for something that could be interposed to take the rain of blows from the flying band. Max, however, saw that something more prompt than this was necessary. From the look on the man's face it was clear that if the pressure on his throat and chest were not immediately relaxed he would be choked to death.

Crawling forward beneath the flogging band, and bowing his head to its pitiless flagellations, Max grasped the overturned machine and strove to lift it off the unfortunate man. The weight was altogether too great for him to lift unaided, but he found he could raise it a fraction of an inch and enable the man to gain a little breath.

Holding it thus, Max grimly stood his ground with his head down, his teeth firmly set, and his back arched against the rhythmic rain of blows from the great band. Soon the clothes were flogged from off his back, and the band touched the bare skin. Almost fainting, he held on, for the eyes of the man below him were staring up at him with a look of dumb and frightened entreaty that roused in him all the strength of mind and fixity of purpose he possessed.

The shouts for the engines to be stopped at last prevailed. The bands revolved more slowly, and then ceased altogether. Many willing hands were laid upon the overturned machine, and it was lifted off the prostrate man just as Max's strength gave out, and he sank limply to the floor in a deep swoon.

Neither Max nor the workman was seriously injured. Both had had a severe shock, and Max, in addition, had wounds that, while not dangerous, were extremely painful. After six weeks at Ostend, however, he was himself again, and ready to continue his work in yet another branch of the firm's activities. This time he was to learn the miner's craft, and to see for himself all that appertained to the trade of hewing out coal and iron from the interior of the earth and lifting it to the surface.

On the evening of his return to Liége from Ostend he was sitting in his study alone, reading up the subject that was to be unfolded in actual practice before his gaze on the morrow, when there came a knock at the door.

"Come in," he yelled.

The door opened, and the maid ushered in a middle-aged workman in his Sunday clothes, accompanied by a woman whom Max guessed to be his wife. The man he recognized at once as the workman he had succoured in the accident to the driving-band.

"Monsieur Dubec—he would come in," explained the servant deprecatingly, as she withdrew and closed the door.

The man looked furtively at Max, twisted his cap nervously in his hands, and stood gazing down at the floor in sheepish silence. His wife was less ill at ease, and, after nudging her spouse ineffectually once or twice, blurted out rapidly:

"He has come, Monsieur, to thank you for saving his life, and to tell you that he will work for you and serve you so long as he lives. He is my man, and I say the same, Monsieur, though I do not work in the shops, and cannot help. But if ever ye should want aught done, Monsieur, send for Madame Dubec, and she will serve you with all her heart in any way you wish."

The woman spoke in a trembling voice, and with a deep and earnest sincerity that showed how much she was moved. Her emotion, indeed, communicated itself to Max, and he felt as tongue-tied as the man Dubec himself. It had somehow not occurred to him that he would be thanked, and the whole thing took him by surprise. Still, he had to say something, and he struggled to find something that would put them at their ease.

"I am sure you will, Madame Dubec, and I will remember your offer indeed. But make not too much of what I have done. I was near at hand, and came forward first, but many of your husband's comrades were as ready, though not quite so quick. It was the aid of one comrade given to another, and one day it may be my turn to receive and your husband's to give."

The man shook his head vigorously in dissent, and in so doing seemed to find his tongue.

"Nay, sir, 'tis much more than that. Some there are who would have helped; but the more part of my fellow-workmen would not lift a hand to help another in distress. As ye must have noticed, sir, there are two classes of men in your father's works. There are the Belgians born and bred, who loved your father and hated, and still hate, the tyrant Schenk and the German-speaking workmen who have joined in such numbers of late that we others fear a time will soon come for us to go. The Belgians are good comrades, and would have come to my aid had they the quickness to have known what to do. The others would have seen me die unmoved—I know it."

"But they, too, are Belgians, are they not?"

"Aye, sir, they are Belgians so far as the law can tell; but they speak not our tongue, and are not really of us."

"They are good workmen, and M. Schenk thinks much of them."

"True. But they do not hold with the rest of us, and we do not like them. Nor do we trust them, sir."

The man spoke in an earnest, almost a warning, tone, and Max looked at him in some surprise. It seemed more than the mere jealousy of a Walloon at the presence of so many men, alien in tongue and race, in a business which had once been exclusively their own. Max had himself noticed the two classes of workmen, but had, if he thought about it at all, put it down as inevitable in a town so near the frontiers of three States.

"Well, never mind them, Monsieur Dubec," he replied reassuringly. "They have not been with us long, and it may be they will be better comrades in a few years' time. And now good-bye! Think not too much of your accident, and it will be the better for you and me."

"Good-bye, and may the bon Dieu bless you, sir!" replied both Monsieur and Madame Dubec in a fashion that told Max that he had gained two friends at least, and friends whose staunchness could be depended upon to the utmost.

M. Schenk's view of the whole affair was blunt and to the point. "You are foolish," he said to Max, "to trouble yourself about these workmen. They are cattle, and it is always best to treat them as such. That has always been my way, and it has answered well. Consider them and humour them, and the next minute they want to strike for more. Bah! Keep them in their place; it is best so."

"But," urged Max, quite distressed as he thought of Dubec, and recalled the accents of trembling sincerity of his spouse—"but surely many of them are better led than driven—the best of them, at any rate? I know little of business as yet, but something tells me that it is well for us to get the goodwill of our men."

"It is not worth a straw," replied M. Schenk with conviction. "The goodwill, as you call it, of your managers, and perhaps even of your foremen, is of value, but the goodwill of your men—your rank and file—is of no account. So long as they obey, and obey promptly, you have all that is necessary to carry on even a great undertaking like this successfully."

"Well," replied Max rather hotly, "all I can say is that when I direct the affairs of the firm, I shall give the other thing a trial. I don't like the idea of treating men as cattle, and I cannot help thinking too many men have been discharged of late because they have shown a little spirit."

M. Schenk looked at Max in a way that made the latter momentarily think he would like to strike him. Then the manager half turned away, as he replied in an almost contemptuous tone: "You will be older and wiser soon, and we shall then see whether any change will be made. Until then it is I who direct the affairs of the firm, and it is my policy which must prevail."

Max felt uncommonly angry. He had been conscious for some time past that M. Schenk was acting as though he expected to rule the affairs of the firm for all time, and the thought galled him greatly. Was not he, Max, sweating and struggling through every workshop solely in order that he might fit himself to direct affairs? How was it, then, that this man, in his own mind, practically ignored him? Was it because he was so incompetent that the manager thought he never would be fit to take his place? Max certainly felt more angry than he had ever done before, and, unable to trust himself to speak, abruptly left the manager's presence and walked rapidly away.

One good result the conversation had, and that was to redouble Max's ardour to learn, and learn thoroughly, every branch of the work in every part of the vast concern.

The second summer since Max Durend had left Hawkesley had come, and for the second time Max invited his friend Dale to come over to Liége and spend a few weeks with him. The previous summer they had spent most pleasantly on a walking-tour through the Ardennes, and they were now going to do the same thing along the Middle and Upper Rhine. Max had originally planned a tour in Holland, but M. Schenk recommended the Rhine valley as much more varied and picturesque, and Max had agreed readily enough to follow his recommendation.

Behold them then setting out from Bonn railway station, knapsack on back and walking-stick in hand, full of spirits and go, for a four or five weeks' tramp, first through the Drachenfels and then on through the pretty Rhine-side villages, making a detour here and there to visit the more picturesque and broken country through which the Rhine made its way. They marched light, their only baggage besides their knapsacks being a large Gladstone shared between them. This they did not take with them, but used, merely to replenish their knapsacks occasionally with clean linen, by sending it along a week or so ahead of them to such towns as they expected to visit later on.

Their days were full of happiness, peace, and contentment, and the last days of July, 1914, drew to a close all too rapidly for them. They knew next to nothing of the fearful storm brewing, until Dale happened, towards the end of the second week of their holidays, to take up and glance down the columns of a German newspaper lying on the table of the hotel at which they were about to dine. His knowledge of German was small, but was sufficient to enable him to grasp the purport of the thick headlines with which the journal was plentifully supplied.

"Hullo, Max, look at this," he cried, pointing to the thick type. "German ultimatum to Russia. Immediate demobilization demanded." "That looks serious, eh?"

"Phew! It does," cried Max, taking the paper and rapidly scanning the chief columns. "You may be sure that if Russia is in it France will be too. My hat! what a war it will be!"

"Yes, and——By the way, this explains why those two Frenchmen we met at the hotel yesterday were in such a hurry to be off without waiting for breakfast. They had seen the news and were afraid that, if they didn't get back at once, they wouldn't get back at all."

"That's it. There's one comfort, anyway, Dale, and that is, that neither of us is likely to be concerned. There seems no earthly reason why England or Belgium should come into this."

"No, and a good job too. We have enough troubles of our own all over the world without butting in on the Continent."

For the next few days Max and his friend were again more or less buried from the outer world. They had not, however, altogether forgotten the great events that were taking place, and on reaching Bingen went so far (for them) as to purchase a paper. Matters, they found, had grown far more serious. Germany was already at war with Russia and France, and had demanded of Belgium free passage for her troops to enter and attack France.

Max was thunderstruck. He had never expected anything like this. That Belgium, peace-loving Belgium, with her neutrality guaranteed by practically all the great civilized Powers, should, in spite of it, be about to be forced into a great European war had seemed unthinkable. Yet so it was, and it seemed that war was inevitable, for Max did not believe Belgium would ever allow foreign troops to cross her territory to attack a country with which she was at peace. With Belgium, then, on the verge of war, it behoved him to look to his own safety; for it was obvious he was not safe where he was.

"I think we had better make tracks for home, Dale," he said soberly. "I dare say I can pass with you as an Englishman, but it won't do to take risks. Our bag should be at the Central Post Office, so let us get it and take the first train back to Liége."

"If there are any trains bound for the frontier that are not crammed with troops," responded Dale somewhat significantly.

"Oh, shut up! Come along and let's see."

They lost not a moment in getting their bag and having it conveyed to the railway station. Fully alive to the situation, they now kept their eyes well open and noticed things they would never have noticed before. For one thing, it struck them that the post office official who handed their bag over to them seemed decidedly over-curious, and remarked that he supposed they were going to the railway station. That was disconcerting enough, but when they arrived at the station, and were almost immediately accosted by a man whom they both remembered seeing inside the post office, they felt almost as though they were already under lock and key.

Not that the man was unfriendly. He was quite the reverse. He seemed anxious to strike up an acquaintance, wished to know exactly where they were going, and gave them to understand that there was nothing he desired more than to be allowed the privilege of making a part of the journey with them.

Max presently gave Dale a meaning glance. It was all very well for an Englishman like Dale, he felt, but for him, virtually a Belgian, the situation was wellnigh desperate.

"I say, Dale," he said casually, "we must have some sandwiches to eat in the train. Stay here by the bag while I get some—or perhaps this gentleman wouldn't mind looking after it for a moment?"

The young German hesitated a second, and then nodded. Max and his friend strolled coolly off, arm in arm, towards the refreshment buffet. Neither looked back, but their conversation was far from being as airy and unconcerned as their manner might have seemed to indicate.

"We must leave the bag and get clear at once," cried Max emphatically. "The fellow has been set to watch us and see that we don't get out of the country. I think he must believe we are both English, and it therefore looks as though the Germans think England is on the point of coming in too. See, now, let us stroll quietly in at this door and slip out again at the end one. Then into the street and somewhere—no matter where—so long as it is out of the way of spying eyes."

They did so with an unhurried celerity that might have deceived a smarter man than the supposed spy. Soon they were clear of the town and in the open country beyond, and it was not till then that they felt as though they could talk unrestrainedly together.

"Now what shall we do, Max? Walk to the next station out from Bingen and see if we can get a train for home?" enquired Dale, not too hopefully.

"No, old man; we must keep clear of railways and railway stations. Let us make tracks for the frontier as we are, and go all out."

"It will be dark in another hour."

"Never mind. We must foot it all night. We have no time to lose, and we must not throw away a single hour. In fact, it is hardly safe for us to be about in daylight anywhere. You look as English as they are made, and I'm not much better."

"All right! I'm game for an all-night tramp. Come on."

"We have about seven hours of darkness before us, and I reckon we ought to be able to do four miles an hour. That gives us about thirty miles. It's less than that to the frontier, and we ought to be able to manage it, even if we have to leave the road and cut straight across country. Come along; we'll keep to the road while we can, but if too risky we must go helter-skelter, plumb for the frontier."

That night march neither of them is ever likely to forget. For an hour or so they tramped along the road unmolested. Then they began to find soldiers and policemen very much in evidence, and, fearing to be questioned, they left the road and took to the fields and open country. It was desperately rough going in many places, and instead of doing four miles an hour they could oftentimes do no more than two. But they stuck gamely to their task, and plodded steadily on all through the night, realizing more surely with every step they took that it was a plain case of now or never.

For every time they neared a road they found it alive with soldiers, all marching steadily in one direction—towards the Belgian frontier. The still night air resounded with the tramp of innumerable feet, and now and again they could catch the distant rumble of heavy guns.

When day broke they were still in Germany, but near the frontier, and in a sparsely peopled district. They were both nearly dead-beat, covered with mud from head to foot, and with their clothes torn half off their backs. It seemed a risky business to let themselves be seen anywhere in that condition, but finally Max chose a lonely farm-house, and, after cleaning himself up as much as possible, managed to make a purchase of a good supply of food. They then tramped on for another mile or two, ate a good meal, hid themselves in a dry ditch, and instantly dropped asleep.

It was ten o'clock when they awoke, and after some discussion they decided to make the few miles between them and the border at once, and then to purchase cycles and press for home. This they did exactly as they planned, and, though often delayed and compelled to make wide detours to avoid bodies of German cavalry, they managed to reach Liége safely in the evening of the same day.

The sights that met their gaze on the latter part of their journey made them doubly eager to get within the safety of the ring of forts surrounding Liége. Peasants were fleeing from the frontier villages, and their tales of what the Germans had done to their homes and dear ones made the blood of Max and his friend alternately freeze with horror and boil with rage. Their tales were a long catalogue of deeds of ruthless barbarity, cold-blooded cruelty, lust, and rapine. The smoke of burning houses seen in the distance gave emphasis to their tales of horror, and Max and Dale at last felt as though the world must be coming to an end. Indeed, the world of make-believe German civilization was coming to an end in a wild outburst of unrestrained cruelty and lust.

But at Liége, they told one another, things would be different. There the invaders would come against something more than villages peopled with frightened peasants and trustful countryfolk, and would realize in their turn something of the terribleness of war.

Arrived at his home, Max was astonished to find that his mother and sister had fled over the border to Maastricht, taking two of the servants with them. A letter had been left for him, however, and this he tore feverishly open. In a few words his mother explained why she, as an Englishwoman and one getting on in years, preferred to seek safety in Holland to remaining in a city which obviously would soon be the storm-centre of a terrible struggle. She then reminded Max that he had not yet reached a man's age, and could not be expected to take a man's part. Would he not leave the affairs of the firm to M. Schenk and join her in Holland? But his conscience must decide, she finally conceded, though it was clear how her own desires ran. But whether he left or stayed, she expected him to take no part in the fighting that was bound to come.

Questioning the servants, Max found that his mother's flight had been arranged at the urgent solicitation of M. Schenk, and without more ado he left the house and hastened to the works to see the manager, and gather what further particulars he could. He did not doubt the wisdom of his mother's precipitate flight, for even now scouting parties of the Germans had appeared before the eastern forts, and no one could doubt that the city was on the point of being invested and besieged.

M. Schenk was clearly surprised to see Max and his friend, and was at no pains to hide it.

"A letter was left for you, Monsieur Max," he said in his ponderous way, "telling you that your mother wished you to join her instantly. Did they not hand it to you?"

"Yes," replied Max, "I have received the letter, and I have come to learn something more about their flight. Have they taken money enough for what may be a long stay? And can we send them more before the city is invested?"

"All that is seen to, Monsieur Max. I have had a large sum of money transferred to a bank in Maastricht for their use. They will be safe and well there, and I strongly advise you to join them. You will certainly not be safe here."

"Why not? Why should I go if you can stay—if you are staying?"

"Because, sir, you are half an Englishman, and before the day is out England will have joined in this conflict. No Englishman will be safe here if the Germans enter, and I strongly urge you and your friend to escape before the city is surrounded. I will carry on the business, and do my best in the interests of the firm and your good mother."

"Yes, yes, I know; but I am a Belgian as much as an Englishman, and I am not going to fly the country like that. If I cannot yet fight for her I can work for her, and I have made up my mind to stay, Monsieur Schenk."

"As you will," replied M. Schenk, shrugging his shoulders in indifference, "but do not blame me if things do not go as you wish."

"That's all right," replied Max quickly. "Now, as to the work of the firm. I have been thinking that we might use our great works to assist in the defence of the town. Soon the forts will be in action, and if the city is invested they can only replenish their stores from within the town itself. Why should we not begin to cast shells instead of rails, and see whether we cannot make rifles and machine-guns instead of machinery? There are many things we could do at once, and many others in a little while."

"That is true, sir, and you will find that I have not been behindhand. I have already seen the commandant, and our casting-shops are almost ready to begin casting shells. I am not letting the grass grow under my feet, I can assure you, and in a week or two we shall be able to do great things in the defence of the town. Come down to the works with Monsieur Dale, and see the preparations we are making for turning out shells for big guns. You will see that the Durend workshops are going to be well to the fore here as elsewhere, and I prophesy that they will be so until the end of the war."

As they made the tour of the works, Max was both astonished and delighted at the evidence he saw of the energy and ability displayed in turning over the vast manufacturing resources of the firm from peace to war. The rapidity with which the works had been transformed was indeed remarkable, and his opinion of M. Schenk's capacity, already great, became almost profound.

"Now, Dale, what are you going to do?" demanded Max as the two friends parted company with the manager at the door of the last shop. "I think you had better get clear while you can. This place is my home and I must stand by it, but you are not concerned and ought to get out of it, if only for your people's sake."

"My people! My uncle and aunt, you mean. They won't bother their heads about me," replied Dale decidedly. "No, Max, I came over here to see the sights, and I am going to see 'em, come what may. If England is in it, well and good; it will then be my quarrel as much as yours, and we will work or fight against Germany together. Hurrah!"

Max grasped his friend's hand. "I ought not to encourage you, Dale, but I can't help it, and I'm jolly glad. Let us go into this business together—it will seem like old times. D'ye remember the fight we put up for Benson's?"

"Who could forget it?" cried Dale with enthusiasm.

"And how it ended?"

"Aye—and it was fixity of purpose that did it, so said Benson. Well, let us do something of the sort again. Hark! d'ye hear that?"

"Rifle-shots. The fun has commenced. Come along, and we will see what we can of it before the day is out. To-morrow I am going to start work in the casting-shops, and I hope you will come and help me."

"I will. Come along."

The sound of rifle-shots was quickly succeeded by the distant boom of guns. Then the sound was swallowed up in the roar of the big guns of the forts, and it seemed as though a tremendous attack was in progress. The streets of the town instantly began to fill with excited people, until it appeared as though everyone had left his work to discuss the situation and listen to the noise of battle. Through the crowds pressed small bodies of soldiers dispatched as reinforcements to the ring of forts surrounding the town.

Max and Dale followed one of these parties at a respectful distance, and climbed with them from the cup-like hollow in which Liége is situated to the hills beyond. The soldiers were bound for one of the forts on the eastward side, and, as they reached the higher ground, the two lads caught their first glimpse of the fighting. Darkness was coming on, and away in the distance they could see the intensely bright flashes of high-explosive shells bursting on or around the forts, as well as the flame of the fortress guns belching forth their replies. As it grew darker the duel grew more intense, and lasted without intermission throughout the night till three or four o'clock in the morning.

By that time the forts were apparently thought to have been sufficiently damaged to permit of an assault, and the German infantry were flung against them in massed formation. Unfortunately for them, however, the guns had not been heavy enough to make any impression on the steel cupolas which sheltered the big guns of the forts, and, as the infantry pressed forward to the attack, they were literally swept away by a devastating shell-fire from the forts attacked and those flanking them.

Again and again fresh masses were sent forward to the assault, only to meet with a similar fate. In the attack on one of the forts the infantry, favoured no doubt by the formation of the ground, were able to get so close that the guns could not be depressed sufficiently to reach them. They believed the fort as good as won, and with cheers of exultation pressed on to the final assault. But at the corners of the forts quick-firing guns were stationed, and these and the infantry lining the parapets mowed them down as surely as the big guns.

In the wide spaces between the forts the Belgian field army had entrenched, and with rifle-fire and frequent bayonet attacks frustrated every attempt of the German infantry to break through.

The infantry assaults lasted until eight o'clock in the morning, when the Germans withdrew, heavily shaken. They had hoped to rush the forts with heavy masses of infantry, supported only by light artillery, and they had failed. They now waited for the heavy guns, which were already on the road, to arrive, and very soon forts Fléron and Chaudfontaine were deluged with an accurate fire of enormous shells, so powerful as to overturn the massive cupolas and to pierce concrete walls twelve feet thick as though they were made of butter. Such shells as these they had never been built to withstand, and it was not long before they succumbed, thus opening a way for the invaders towards the town itself.

Forts Evegnée and Barchon soon shared the same fate, and the Belgian field army, which had continued to maintain an heroic resistance, began to fall back on the town.

Max and Dale had not been allowed to see much of these events. Before midnight they were accosted by a patrol and ordered to return to the safety of the town.

Early the following day, before the fall of the forts and the retreat of the Belgian army, Max and Dale carried out their intention of presenting themselves at the casting-shops and lending a hand in the making of shells. To their satisfaction they found the work going forward with splendid energy and smoothness, and, with their own ardour kindled by the sights they had seen the previous night, they joined zealously in the work.

Presently it came home to Max that there had been considerable changes in the personnel of the shop since he had last worked there. The men he looked out for—those with whom he had been on most friendly terms when he was there—were gone, and their places were taken by other and, for the most part, younger men, all quite strangers to the place so far as he could see.

But, most strange of all, the language of the shop was German. The Walloon, or Flemish-speaking Belgians, were the men who had gone, and German-speaking workmen had taken their places.

On making a few cautious enquiries, Max learned that the men who had gone had been transferred to shops which were still engaged in executing peace-time orders, rails, axles, wheels, and the like, and that the whole of the shell output was being handled by the newer German-speaking workmen.

Max felt no particular resentment at this. He did not like it, but he knew the manager's preference for these men as workmen, and he could not deny that they were a hard-working, docile lot, nor that the work was well organized and being carried on with splendid spirit and energy.

It seemed hard, however, that the Belgian-born men should not have a chance of directly working for their country's benefit, and, as soon as he could, Max took an opportunity of representing the matter to M. Schenk.

"Why have you withdrawn all the older men from the shell-shops, Monsieur Schenk? They were good men, and have served the firm well. Upon my word, while working there and hearing naught but the German tongue, one might have fancied oneself in the enemy's country."

"They are loyal Belgians, Monsieur Max," replied M. Schenk reassuringly. "They are as ready as Flemings or Walloons to work to the utmost, casting shells for our gallant army. That speaks sufficiently for their sentiments. I have filled the shop with them because they work well together, and there is no jealousy. We must do our best for Belgium in this crisis, and should be swayed by no consideration save that of finding the best men for each of our great tasks."

"Well done, Monsieur Schenk!" cried Max impulsively. "I also will go where you think best. Where shall it be?"

"Thank you!" replied the manager, smiling. "I think you are doing so well where you are that I cannot improve upon it. Remain at work in the casting-shop and aid me to increase the output of shells. It is my belief that we can turn out double the number with no increase of staff, and I shall leave no stone unturned to make my opinion good."

Greatly heartened by this evidence of the manager's energy and patriotism, Max and his friend did stick to their work and fling themselves into it even more whole-heartedly than they had done before.

On the morrow, the 7th August, however, events happened that entirely changed the aspect of affairs. Forts Fléron, Chaudfontaine, Evegnée, and Barchon had fallen, and early in the morning of that day German infantry entered Liége. The forts on the north, south, and west of the town still held out for a time, but the town from that moment remained in German hands. To the people, and especially the workers of Liége, this made a vital difference. The output of the numerous factories, in so far as it was useful to the German armies, was at any moment liable to be requisitioned by them; and it was as clear as noonday that all who toiled in the manufacture of such articles were assisting the enemy in their attack upon their own kith and kin, and strengthening the grip he had already laid upon their native land.

To Max and his chum these were days charged high with excitement. Their day's toil in the shops over, they raced away to the points where the most exciting events were to be seen. They were witnesses of most that went forward, and actually lent a hand in the rounding-up, from among the civil population of the city, of the band of armed Germans who attempted to assassinate the commandant of the fortress, General Leman.

The entry of the Germans was to both of them a fearful blow. They knew little of military matters, and vaguely believed that the town and forts were strong enough to stand a regular siege. And yet on the third day after the attack the town had fallen! As they watched the young German troops marching into the town they could not help feeling deeply disappointed and discouraged.

"I wish now that you had gone home, Dale," remarked Max in a gloomy voice as they slowly made their way towards the works. "Now that the place has fallen you can do no good here. And as you are not a native you may be taken for a spy and shot off-hand."

"Shut up, Max! We've agreed to go through this business together, and there's an end of it. Liége is lost, but the war's still on, and it will be hard if we can't find some way of giving our side a shove forward."

"Aye to that, Dale. Well, if you don't mind being here in a conquered town I'm jolly glad to have you. Now, I suppose we can still go on helping to cast shells—why no, Dale! We simply can't do any more of that work; it's absolutely useless."

"Of course it is. You may be sure the Germans won't let shells be sent away from Liége except to Germany. Your works had better get on with the other work. Shells are out of the question."

"I must see Schenk about this," replied Max thoughtfully. "It needs thinking out what work—if any at all—we can do without helping the Germans. It's an awkward business, but I have no doubt Schenk can see daylight through it."

"I should think so, but—hallo! What's that?"

Dale stopped suddenly, and stood gazing down a side street, the end of which they were just about to cross. A sudden burst of screams and shouts, quite startling in its intensity, assailed their ears, and made them look and look with a feeling of foreboding new to them. At the far end of the street they could see a group of men in the grey-green uniform surging to and fro before a house from which the screams seemed to issue.

"The Germans—doing the same dirty work as they did at Visé!" gasped Max, turning away his head and clenching his fists in his pockets. "I hardly know how to keep from rushing down there, utterly useless though it is."

"It is women they are ill-treating—how can we walk away?" cried Dale in acute distress. "Let us go down, and if we cannot fight, let us beg them to desist. Perhaps if we offered them money——?"

"Useless," muttered Max, though he stopped and gazed down the road in irresolution. "And yet how can we pass by, Dale?" he went on with a groan. "I know I shall always call myself a coward if I do nothing. Let's walk a little closer, and see if we can do anything."

Dale eagerly agreed, and they walked quickly down the road towards the group of soldiers and their victims. As they drew nearer, and could see something of what was happening, their anger increased, until they were almost ready to throw themselves upon the soldiers and oppose their bayonets with their bare fists.

The house before which the outrage was taking place seemed, for some reason, to have been singled out from the others which lined both sides of the street, possibly because the head of the house was well known as an opponent of the Germans or because of some act of hostility committed against the soldiers. At any rate, an elderly man, evidently dragged from the house, had been tied to the front railings, and was being subjected to treatment so cruel that it almost amounted to torture.

The womenfolk of the house had apparently rushed out and endeavoured to intervene, but had been forcibly held back, and were at that moment being subjected to brutal indignities that angered Max and Dale even more than the cold-blooded cruelty to the man himself.

The two had arrived within some forty yards of the scene, and were still pressing on as though drawn by a magnet, although neither knew what he was going to do, when one of the soldiers drew the attention of his fellows to the two young men advancing towards them. At the same time he picked up his rifle, took quick aim, and discharged it directly at them.

The bullet whizzed between them, and, on the impulse, Max seized Dale by the arm and dragged him through the open doorway of the nearest house. A roar of laughter from the soldiers at their rapid exit followed them, and made the anger of one at least of them burn with a still fiercer resentment.

"Right through and out at the back," cried Max in urgent tones, and the two passed through the house, which appeared to be deserted, and found themselves in an open space intersected only by low garden fences.

Max laid his hand on his friend's arm. "I am going to move quietly along until I reach the back of the house where those curs are at work," he said in a hard, suppressed voice. "I must do something, but do not you come, Dale. There is no need for you——"

"I am already in it, I tell you," almost shouted Dale as he impatiently shook him off. "It's as much my affair as yours. Come on."

The two made their way rapidly but cautiously along until they reached the house they sought. The doors were open at the back, and the shouts and screams were almost as audible there as at the front.

"We have no weapons; let us arm ourselves with these," cried Max, pointing to some blocks of ornamental quartz bordering a little fernery. Even in the midst of his excitement it struck Max how strangely the orderliness of the tiny, well-kept garden seemed to contrast with the deeds of violence being committed outside.

Rapidly but quietly the two lads filled hands and pockets with the heavy missiles. Then they crept inside the house and up the stairs to the floor above. The house was quite empty, for all within had rushed or been dragged to the scene in front.

The bedroom windows were wide open, and the instant they entered both lads began with one impulse to hurl with all their strength the great stones upon the German soldiery below. They were both wild with rage at what they had witnessed, and utterly reckless what fate might ultimately be theirs, so long as they could inflict some punishment upon the cowardly wrongdoers.

The soldiers, completely taken aback by this sudden rain of missiles almost from the skies, immediately scattered to the opposite side of the road and took refuge in the gardens there. Not one of them had his rifle to hand, for their arms had been stacked against the wall of the house they were attacking, and even the man who had fired at Max and Dale had put down his rifle once more. Thus, for the moment, the soldiers were impotent, and Max shouted rapidly in the Walloon dialect to the women below to release the man tied to the railings and escape through the house.

With a promptitude that was wholly admirable, one of the women drew a pair of scissors from her pocket and cut the cords that bound the man to the fence. With a cry of joy the poor fellow staggered to his feet. But, stiffened by his bonds or exhausted by the cruel treatment he had received, he could barely stand, and had to be half supported and half dragged by two of the women back into the house.

"Tell them to be off, Dale," cried Max rapidly. "I will hold back these men for a minute. Take them right through into the street beyond and get them out of sight. I will follow in a moment."

Dale obeyed, and under his guidance the whole party made their way rapidly through the house, into the gardens, and through the houses opposite into the road beyond. At the disappearance of their prey the soldiers set up a howl of rage, and made a concerted rush for their weapons. But Max redoubled his efforts, and, his supply of quartz exhausted, rained down upon them jugs, mirrors, pictures, and everything movable he could lay hands upon, holding them in check for a few precious moments. Then, after one final fling, he bolted from the room into the bedroom at the back and leapt out of the window. Landing in a flower-bed unhurt, he rushed without a pause at the low garden fence in front of him, cleared it at a bound, and dashed through the house opposite in the wake of Dale and the fugitive people.