Transcriber’s Notes:

1) For correct rendering of some diacritical marks please change browser default font

to Arial.

2) There are a number of words in the native language that appear to mean the

same thing, but have different accents. It is unknown if this is intentional

or a printing error - these have been left as printed.

eg: Nuleága / núleaga ... Takináka / takínaka / Takinaka ... Wáhok / wahok

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM

ANTHROPOLOGICAL PUBLICATIONS

Vol. VI No. 2

————————————————————————————

THE DANCE FESTIVALS OF THE

ALASKAN ESKIMO

BY

E. W. HAWKES

PHILADELPHIA

PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM

1914

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

This account of the Dance Festivals of the Alaskan Eskimo was written from material gathered in the Bering Strait District during three years’ residence: two on the Diomede Islands, and one at St. Michael at the mouth of the Yukon River. This paper is based on my observations of the ceremonial dances of the Eskimo of these two localities.

PHONETIC KEY

ā, ē, ī, ō, ū, long vowels.

a, e, i, o, u, short vowels.

ä, as in hat.

â, as in law.

ai, as in aisle.

au, as ow in how.

h, w, y, semivowels.

c, as sh in should.

f, a bilabial surd.

g, as in get.

ǵ, a post-palatal sonant.

k, as in pick.

l, as in lull.

m, as in mum.

n, as in nun.

ng, as ng in sing.

p, as in pipe.

q, a post-palatal surd.

ṙ, a uvular sonant spirant.

s, as in sauce.

t, an alveolar stop.

tc, as ch in chapter.

v, a bilabial sonant.

z, as in zone.

THE DANCE FESTIVALS OF THE ALASKAN ESKIMO

THE DANCE IN GENERAL

The ceremonial dance of the Alaskan Eskimo is a rhythmic pantomime—the story in gesture and song of the lives of the various Arctic animals on which they subsist and from whom they believe their ancient clans are sprung. The dances vary in complexity from the ordinary social dance, in which all share promiscuously and in which individual action is subordinated to rhythm, to the pantomime totem dances performed by especially trained actors who hold their positions from year to year according to artistic merit.[1] Yet even in the totem dances the pantomime is subordinate to the rhythm, or rather superimposed upon it, so that never a gesture or step of the characteristic native time is lost.

This is a primitive 2-4 beat based on the double roll of the chorus of drums. Time is kept, in the men’s dances, by stamping the foot and jerking the arm in unison, twice on the right, then twice on the left side, and so on, alternately. Vigorous dancers vary the program by leaping and jumping at intervals, and the shamans are noted for the dizzy circles which they run round the púgyarok, the entrance hole of the dance hall. The [Pg 10] women’s dance has the same measure and can be performed separately or in conjunction with the men’s dance, but has a different and distinctly feminine movement. The feet are kept on the ground, while the body sways back and forth in graceful undulations to the music and the hands with outspread palms part the air with the graceful stroke of a flying gull. Some of their dances are performed seated. Then they strip to the waist and form one long line of waving arms and swaying shoulders, all moving in perfect unison.

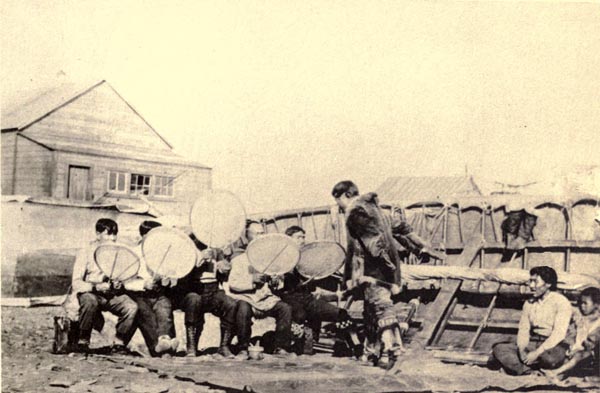

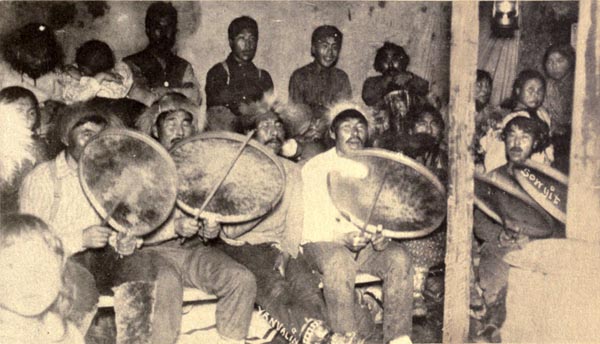

The Chorus

The chorus which furnishes the music, is composed of from six to ten men. They sit on the inǵlak, a raised shelf extending around the dance hall about five feet from the floor, and sing their dance songs keeping time on their drums. They usually sit in the rear of the room, which is the post of honor. Among the island tribes of Bering Strait this position is reversed and they occupy the front of the room. Some old man, the keeper of tribal tradition and song, acts as the leader, calling out the words of the dance songs a line ahead. He begins the proceedings by striking up a low chant, an invitation to the people assembled to dance. The chorus accompany him lightly on their drums. Then at the proper place, he strikes a crashing double beat; the drums boom out in answer; the song arises high and shrill; the dancers leap into their places, and the dance begins.

The first dances are usually simple exercises calculated to warm the blood and stretch stiffened muscles. They begin with leaping around the púǵyarok, jumping into the air with both [Pg 11] feet in the Eskimo high kick, settling down into the conventional movements of the men’s dance.[2]

Quite often a woman steps into the center of the circle, and goes through her own dance, while the men leap and dance around her. This act has been specialized in the Reindeer and Wolf Pack Dance of the Aithúkaguk, the Inviting-In Festival, where the woman wearing a reindeer crest and belt is surrounded by the men dancers, girt in armlets and fillets of wolf skin. They imitate the pack pulling down a deer, and the din caused by their jumping and howling around her shrinking form is terrific.

Participation of the Sexes

There appears to be no restriction against the women taking part in the men’s dances. They also act as assistants to the chief actors in the Totem Dances, three particularly expert and richly dressed women dancers ranging themselves behind the mask dancer as a pleasing background of streaming furs and glistening feathers. The only time they are forbidden to enter the kásgi is when the shaman is performing certain secret rites. They also have secret meetings of their own when all men are banished.[3] I happened to stumble on to one of these one time when they were performing certain rites over a pregnant woman, [Pg 12] but being a white man, and therefore unaccountable, I was greeted with a good-natured laugh and sent about my business.

On the other hand, men are never allowed to take part in the strictly women’s dances, although nothing pleases an Eskimo crowd more than an exaggerated imitation by one of their clowns of the movements of the women’s dance. The women’s dances are practiced during the early winter and given at the Aiyáguk, or Asking Festival, when the men are invited to attend as spectators. They result in offers of temporary marriage to the unmarried women, which is obviously the reason for this rite. Such dances, confined to the women, have not been observed in Alaska outside the islands of Bering Sea, and I have reason to believe are peculiar to this district, which, on account of its isolation, retains the old forms which have died out or been modified on the mainland. But throughout Alaska the women are allowed the utmost freedom in participating in the festivals, either as naskuks[4] or feast givers, as participants or as spectators.

In fact, the social position of the Eskimo woman has been misrepresented and misunderstood. At first sight she appears to be the slave of her husband, but a better acquaintance will reveal the fact that she is the manager of the household and the children, the business partner in all his trades, and often the “oomíalik,” or captain of the concern as well. Her husband is forbidden by tribal custom to maltreat her, and if she owns the house, she can order him out at any time. I have never known a woman being head of a tribe, but sometimes a woman is the most influential member of a tribe.

THE KÁSGI OR DANCE HOUSE

With few exceptions, all dances take place in the village kásgi or dance hall. This is the public meeting place where the old men gather to sit and smoke while they discuss the village welfare, where the married men bring their work and take their sweat baths, and where the bachelors and young men, termed kásgimiut, have their sleeping quarters. The kásgi is built and maintained at public expense, each villager considering it an honor to contribute something. Any tools or furnishings brought into the kásgi are considered public property, and used as such.

When a kásgi is to be built, announcement is made through messengers to neighboring villages, and all gather to assist in the building and to help celebrate the event. First a trench several feet deep is dug in which to plant the timbers forming the sides. These are usually of driftwood, which is brought by the ocean currents from the Yukon. The ice breaks up first at the head of that great stream, and the débris dams up the river, which overflows its banks, tearing down trees, buildings and whatever borders its course as it breaks its way out to the sea. The wreckage is scattered along the coast for over a hundred miles, and the islands of Bering Sea get a small share. The islanders are constantly on the lookout for the drifting timber, and put out to sea in the stormiest weather for a distant piece, be it large or small. They also patrol the coast after a high tide for stray bits of wood. When one considers the toil and pain with which material is gathered, the building of a kásgi becomes an important matter.

[Pg 14] After the timbers have been rough hewn with the adze (úlimon) they are set upright in the trench to a height of seven to eight feet and firmly bedded with rock. This is to prevent the fierce Polar winds which prevail in midwinter from tearing the houses to pieces. In the older buildings a protecting stone wall was built on the sides. Most of the houses are set in a side hill, or partly underground, for additional security, as well as for warmth. The roof is laid on top of the uprights, the logs being drawn in gradually in pyramid shape to a flat top. In the middle of the top is the ṙálok or smoke hole, an opening about two feet square. In a kásgi thirty feet square the rálok is twenty feet above the floor. It is covered with a translucent curtain of walrus gut. The dead are always taken out through this opening, and never by the entrance. The most important feature of the room is the inǵlak, a wide shelf supported by posts at intervals. It stands about five feet high extending around the room. This serves the double purpose of a seat and bed for the inmates of the kásgi. The rear, the káan, is the most desirable position, being the warmest, and is given to headmen and honored guests.[5] The side portions, káaklim, are given to the lesser lights and the women and children; and the front, the óaklim, being nearest the entrance and therefore cold and uncomfortable is left for the orphans and worthless men.

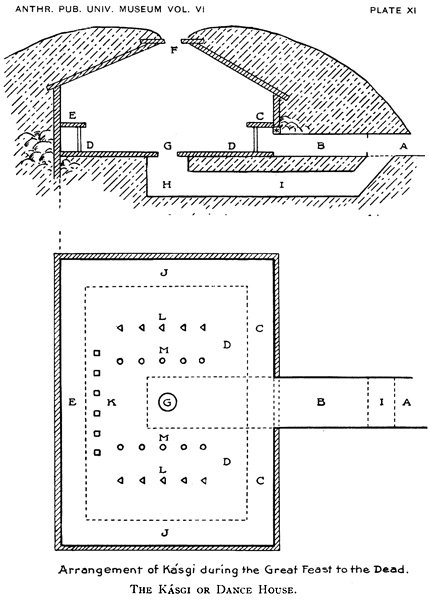

The floor of the kásgi is made of rough planking, and the boards in the center are left loose so that they may be easily removed. These cover the kēnéthluk or fireplace, an excavation [Pg 15] four feet square, and four feet deep, used in the sweat baths. It is thought to be the place where the spirits sit, when they visit the kásgi, during festivals held in their honor. Offerings are poured to them through the cracks in the planks. In the center of the floor is a round hole about two feet in diameter, called the entrance hole or púgyarok. This connects with a long tunnel, the aǵveak, which leads outside. The tunnel is usually so low that it is necessary to enter in a stooping position, which the Eskimo does by placing both hands on the sides of the púgyarok, and drawing himself through. Some dance-houses have another entrance directly into the room on a level with the ground, the underground passage being used only in winter. The diagram (Plate XI) gives an idea of this arrangement.

Paraphernalia

The drum (saúyit)[6] is the only instrument employed in the dances. It is made of a circular hoop about eighteen inches in width over which is stretched a resonant covering made from the bladder of the walrus or seal. It is held in place by a cord of rawhide (oḱlinok)[7] which fits into a groove on the outer rim. The cover can therefore be tightened at will. It is customary during the intermissions between the dances for the drummers to rub a handful of snow over the skins to prevent them from cracking under the heavy blows. The drum is held aloft and struck with a thin stick (múmwa).[8] It gives a deep boom in answer. The shaman uses a smaller baton with which he beats a continuous tattoo as an accompaniment to his songs. The [Pg 16] northerners strike the back of the rim with their sticks, while the Yukon people belabor the face of the drum.

The leader of the chorus frequently flourishes a baton, made from a fox tail or the skin of the ermine which is mounted on a stick. With this he marks the time of the dance. In Plate XIV, the white blur is the ermine at the end of his stick. It is very difficult to obtain a good picture in the ill lighted kásgi, and not often that the natives will allow one taken there.

One indispensable part of a male dancer’s outfit is his gloves. I have never seen a man dancing without them. These are usually of wolverine, or of reindeer with elaborate trimmings, but on ordinary occasions any kind will do. The women do not share this peculiarity. In place of gloves they wear handlets of grass decorated with feathers of duck or of ptarmigan. The men in the Totem Dances also wear handlets which are carved and painted to represent the particular totem they seek to honor. These too are fantastically decorated with feathers, usually of the loon. The central feather is stripped, and crowned with a tuft of white down. Both men and women wear armlets and fillets of skin or feathers according to the animal character they represent. When in the full swing of the dance with fur and feathers streaming they present a pleasing spectacle, a picture full of the same wild grace and poetic motion which characterizes the animal forbears from which they claim descent.

The chief characters in the Totem and Comic Dances wear masks and carry staves decorated with feathers. Occasionally the women assistants carry feathered wands (Kelízruk).

Of the masks there is a great variety ranging from the plain wooden masks to those of such great size that they are suspended [Pg 17] from the ceiling of the kásgi by a cord while the dancer performs behind them.

The Cape Prince of Wales (Kinígumiut) Eskimo construct complete figures of their totems. These are worked by means of concealed strings by the performers, a climax of art which is supposed to be particularly pleasing to the spirits addressed. Then the shaman (Túngalik)[9] has his own set of masks, hideous enough to strike terror to even the initiated. Each one of these represents a familiar spirit (túnghat)[10] which assists him in his operations.

Ordinary dance masks may be made by anyone, but the masks for the ceremonial dances are made by some renowned shaman, engaged for the occasion. These masks are burned at the close of the festival, but may be sold by the actors if they supply an equal amount of wood for the sacrificial fire.

Many of the masks are very complicated, having appendages of wood, fur and feathers. They are all fashioned with an idea of representing some feature in the mythology of the spirit (Inua) or animal shade (Tunghat) which they represent. In the latter case they are nearly always made double, the mythical beings who inhabited the early world being regarded as able to change from animal to human shape, by merely pushing up or pulling down the upper part of the face as a mask. Such masks are often hinged to complete the illusion, the actor changing the face at will.

It might be mentioned here that when the actor puts on the mask he is supposed to become imbued with the spirit of the being represented. This accounts, to the native mind, for the very lifelike imitation which he gives.

[Pg 18] The masks are painted along conventional lines; the favorite colors for the inua masks are red (Karékteoak),[11] black (Auktoak), green (Cúngokyoak), white (Katéktoak), and blue (Taúkrektoak), in the order named. These colors[12] may hold a sacred or symbolic significance. The inua masks are decorated with some regard to the natural colors of the human face, but in the masks of the túnghat the imagination of the artist runs riot. The same is true of the comic masks, which are rendered as grotesque and horrible as possible. A mask with distorted features, a pale green complexion, surrounded by a bristling mass of hair, amuses them greatly. The Eskimo also caricature their neighbors, the Dènè, in this same manner, representing them by masks with very large noses and sullen features.

THE DANCE FESTIVALS

The Dance Festivals of the Alaskan Eskimo are held during that cold, stormy period of the winter when the work of the year is over and hunting is temporarily at an end. At this season the people gather in the kásgi to celebrate the local rites, and at certain intervals invite neighboring tribes to join in the great inter-tribal festivals. This season of mirth and song is termed “Tcauyávik” the drum dance season, from “Tcaúyak” meaning drum. It lasts from November to March, and is a continuous succession of feasts and dances, which makes glad the heart of the Eskimo and serves to lighten the natural depression caused by day after day of interminable wind and darkness. A brisk exchange of presents at the local festivals promotes good feeling, and an interchange of commodities between the tribes at the great feasts stimulates trade and results in each being supplied with the necessities of life. For instance, northern tribes visiting the south bring presents of reindeer skins or múkluk to eke out the scanty supply of the south, while the latter in return give their visitors loads of dried salmon which the northerners feed to their dogs.

The festivals also serve to keep alive the religious feeling of the people, as evidenced in the Dance to the Dead, which allows free play to the nobler sentiments of filial faith and paternal love. The recital of the deeds of ancient heroes preserves the best traditions of the race and inspires the younger generation. To my mind, there is nothing which civilization can supply which can take the place of the healthy exercise, social enjoyment, commercial advantages, and spiritual uplift [Pg 20] of these dances. Where missionary sentiment is overwhelming they are gradually being abandoned; where there is a mistaken opinion in regard to their use, they have been given up altogether; but the tenacity with which the Eskimo clings to these ancient observances, even in places where they have been nominal christians for years, is an evidence of the vitality of these ancient rites and their adaptation to the native mind.

The festivals vary considerably according to locality, but their essential features are the same. Taken in order of celebration they are as follows

Local Festivals.

1. The Aiyáguk or Asking Festival.

2. The Tcaúiyuk or Bladder Feast.

3. The Ailī́gi or Annual Feast to the Dead.

Inter-tribal Festivals.

4. The Aíthukā́tukhtuk or Great Feast to the Dead.

5. The Aithúkaguk or Inviting-In Feast.

The Asking Festival, which begins the round of feasting and dancing, takes place during the November moon. It is a local ceremony in which gifts are exchanged between the men and women of the village, which result in offers of temporary marriage. It takes its name from the Aiyáguk or Asking Stick,[13] which is the wand of office of the messenger or go-between. The Annual Feast to the Dead is held during the December moon, and may be repeated again in spring after the Bladder Feast, if a large number of Eskimos have died in the interim. It consists of songs and dances accompanied by offerings of food and [Pg 21] drink to the dead. It is a temporary arrangement for keeping the dead supplied with sustenance (they are thought to imbibe the spiritual essence of the offerings) until the great Feast to the Dead takes place.

This is held whenever the relatives of the deceased have accumulated sufficient food, skins and other goods to entertain the countryside and are able to properly honor the deceased. At the same time the namesakes of the dead are richly clothed from head to foot and showered with presents. As this prodigal generosity entails the savings of years on the part of the feast givers (náskut), the feast occurs only at irregular intervals of several years. It has been termed the Ten Year Feast by the traders (Kágruska), but so far as I have been able to inquire, it has no fixed date among the Eskimo. It is by far the most important event in the life of the Alaskan native. By it he discharges all debts of honor to the dead, past, present and future. He is not obliged to take part in another festival of the kind unless another near relative dies. He pays off all old scores of hospitality and lays his friends under future obligations by his presents. He is often beggared by this prodigality, but he can be sure of welcome and entertainment wherever he goes, for he is a man who has discharged all his debts to society and is therefore deserving of honor for the rest of his days.

In the Bladder Feast which takes place in January, the bladders of the animals slain during the past season, in which the spirits of the animals are supposed to reside, are returned to the sea, after appropriate ceremonies in the kásgi. There they are thought to attract others of their kind and bring an increase to the village. This is essentially a coast festival. Among the tribes of the islands of Bering Sea and the Siberian Coast this festival is repeated in March, in conjunction with a [Pg 22] whaling ceremony performed at the taking down of the ūmiaks.

The dance contests in the Inviting-In Feast resemble the nith songs of Greenland. They are Comic and Totem Dances in which the best performers of several tribes contest singly or in groups for supremacy. The costumes worn are remarkably fine and the acting very realistic. This is essentially a southern festival for it gives an opportunity to the Eskimo living near the rivers to display their ingenious talent for mimicry and for the arrangement of feathers.

There are a few purely local ceremonies, the outgrowth of practices of local shamans. An example of this is the Aitekátah or Doll Festival of the Igomiut, which has also spread to the neighboring Dènè. Such local outgrowths, however, do not appear to spread among the conservative Eskimo, who resent the least infringement of the ancient practices handed down from dim ancestors of the race.

It is not often that they will allow a white man to witness the festival dances, but, owing to the friendliness of the chief of the Diomede tribes, who always reserved a seat for me next to him in the kásgi, I had the opportunity of seeing the local rites and the Great Dance to the Dead. The same favor continuing with the chief of the Unalit, during my residence on the Yukon, I witnessed the Inviting-In Feast as celebrated by the southern tribes. Having described the dances in general, I will proceed to a detailed account of each.

The Asking Festival

The Aiyáguk or Asking Festival is the first of the local feasts. It occurs about the middle of November when the Eskimo have all returned from their summer travels and made [Pg 23] their iglus secure against the storms of the coming winter. So, with caches full of fish, and houses packed with trade goods after a successful season at the southern camps, they must wait until the shifting ice pack settles and the winter hunting begins. Such enforced inaction is irksome to the Eskimo, who does not partake of the stolidity of the Indian, but like a nervous child must be continually employed or amused. So this festival, which is of a purely social character, has grown up.

My first intimation that there was a celebration taking place was being attracted by a tremendous uproar in the native village just as darkness had fallen. Suspecting that the Eskimo were making merry over a native brew, called “hoosch,”[14] I slipped down to the village to see what was the matter. I was met by the queerest procession I have ever seen. A long line of men and boys, entirely naked and daubed over with dots and figures of mingled oil and charcoal,[15] were proceeding from house to house with bowls in their hands. At each entrance they filed in, howling, stamping and grunting, holding out their dishes until they were filled by the women of the house.

All this time they were careful to keep their faces averted so that they would not be recognized. This is termed the “Tutúuk” or “going around.” Returning to the kásgi they washed off their marks with urine, and sat down to feast on their plunder.

[Pg 24] The next day the men gathered again in the kásgi and the Aiyáguk or Asking Stick was constructed. It was made by a man especially chosen for the purpose. It was a slender wand about three feet long with three globes made of thin strips of wood hanging by a strip of oḱlinok from the smaller end. It was carried by the messenger between the men and women during the feast, and was the visible sign of his authority. It was treated with scrupulous respect by the Eskimo and to disregard the wishes conveyed by means of it during the feast would have been considered a lasting disgrace. When not in use it was hung over the entrance to the kásgi.

The wand maker, having finished the Asking Stick, took his stand in the center of the room, and swaying the globes, to and fro, asked the men to state their wishes. Then any man present had the privilege of telling him of an article he wished and the name of the woman from whom he wished it. (Among the southern tribes the men made small wooden models of the objects they wished which were hung on the end of the Asking Stick.) The messenger then proceeded to the house of the woman in question, swinging the globes in front of her, repeated the wish and stood waiting for her answer. She in turn recollected something that she desired and told it to the messenger. Thereupon he returned to the kásgi, and standing in front of the first party, swung the globes, and told him what was desired in return. In this way he made the round of the village. The men then returned to their homes for the article desired, while the messenger blackened his face with charcoal and donned a costume betoking humility. This was considered the only proper attitude in presenting gifts. The costume consisted of wornout clothing, of which a disreputable raincoat (Kamleíka) and a dogskin belt with the tail behind were indispensable parts.

[Pg 25] Then the men and women gathered in the kásgi where the exchanges were made through the messenger. If anyone did not have the gift requested he was in honor bound to secure it as soon as possible and present it to his partner. Those exchanging gifts entered a relationship termed oīlóǵuk, and among the northern tribes where the ancient forms persevere, they continued to exchange presents throughout succeeding festivals.

After this exchange, a dance was performed by the women. They stripped to the waist, and taking their places on the ińglak, went through a series of motions in unison. These varied considerably in time and movement from the conventional women’s dance.

According to custom at the conclusion of the dance any man has the privilege of asking any unmarried woman through the messenger, if he might share her bed that night. If favorably inclined, she replies that he must bring a deerskin for bedding. He procures the deerskin, and presents it to her, and after the feast is over remains with her for the night.

Whether these temporary unions lead to permanent marriage I was unable to find out. The gift of reindeer skin is very like the suit of clothing given in betrothal and would furnish material for the parka which the husband presents to his bride. The fact that the privilege is limited to unmarried women might be also urged in turn. As the system of exchanging wives was formerly common among the Alaskan Eskimo, and as they distribute their favors at will, it is rather remarkable that the married women are not included, as in the licentious feasts recorded of the Greenlanders.[16] From talks with some of the older Eskimo I am led to regard this as a relic of an ancient custom similar [Pg 26] to those which have been observed among many nations of antiquity, in which a woman is open to violation at certain feasts. This privilege is taken advantage of, and may become a preliminary to marriage.

The Bladder Feast

The Bladder Feast (Tcaúiyuk) is held in December at the full of the moon. The object of this feast is the propitiation of the inua of the animals slain during the season past. These are believed to reside in the bladders, which the Eskimo carefully preserve. The ceremony consists in the purification of the bladders by the flame of the wild parsnip (Aíkituk). The hunters are also required to pass through the flame. They return the bladders then to the sea, where entering the bodies of their kind, they are reborn and return again, bringing continued success to the hunter.

The first three days are spent in preparation. They thoroughly clean the kásgi, particularly the kenéthluk or fireplace, the recognized abode of all spirits visiting the kásgi. Then the men bring in their harvest of bladders.[17] They tie them by the necks in bunches of eight to the end of their spears. These they thrust into the walls at the rear of the room leaving ample room for the dancers to pass under the swaying bladders in the rites of purification. Offerings of food and water are made to the inua, and they are constantly attended. One old man told me that they would be offended and take their departure if left alone for a moment. Dogs, being unclean, are not allowed to enter the kásgi. Neither is anyone permitted to do any work during the ceremony.

[Pg 27] Meanwhile four men,[18] especially chosen for the purpose, scour the adjoining country for parsnip stalks. They bind these into small bundles, and place them on top of the látorak, the outer vestibule to the entrance of the kásgi. In the evening they take these into the kásgi, open the bundles and spread out the stalks on the floor. Then each hunter takes a stalk, and they unite in a song to the parsnip, the burden of which is a request that the stalks may become dry and useful for purification. The heat of the seal oil lamps soon dries them, and they are tied into one large bundle. The third day the sheaf is opened, and two bundles made. The larger one is for the use of the dancers; the smaller is placed on a spear and stuck in front of the bladders.

The fourth day the bladders are taken down and painted. A grayish mixture is used which is obtained by burning a few parsnip stalks and mixing the ashes with oil. The designs are the series of bands and dots grouped to represent the totems of the hunters. When the paint is dry the bladders are returned to their places.

In the evening the men gather again in the kásgi, and the dancers proceed to strip off every vestige of clothing. Snatching a handful of stalks at the common pile they light them at the lamps, and join in a wild dance about the room. The resinous stalks shoot into flame with a frightful glare, lighting up the naked bodies of the dancers, and dusky interior of the kásgi. Waving the flaming torches over their heads, leaping, jumping, and screaming like madmen they rush around the room, thrusting the flame among the bladders and then into the faces of the [Pg 28] hunters. When the mad scene is at its height, they seize one another, and struggle toward the púgyarok (entrance hole). Here each is thrust down in succession until all the dancers have passed through. I am informed that this is a pantomime enactment, an indication to the inua it is time for them to depart.

The next day a hole is made in the ice near the kásgi, and each hunter dips his spear in the water, and, running back to the kásgi, stirs up the bladders with it. The presence of the sea water reminds the inua of their former home, and they make ready to depart. The bladders are then tied into one large bundle, and the people await the full moon.

At sunrise the morning after the full moon each hunter takes his load of bladders, and filing out of the kásgi starts for the hole in the ice on a dead run. Arriving there, he tears off the bladders one by one, and thrusts them under the water. This signifies the return of the inua to the sea.

As the bladders float or sink success is prophesied for the hunter by the shaman in attendance.

In the meantime the old men build a fire of driftwood on the ice in front of the kásgi. The small bundle of parsnip stalks which stood in front of the bladders is brought out and thrown on the fire, and as the stalks kindle to the flame, each hunter utters a shout, takes a short run, and leaps through in turn. This performance purifies the hunter of any matter offensive to the inua, and concludes the ceremony.

During the Bladder Feast all intercourse between the married men and their wives is tabooed. They are required to sleep in the kásgi with the bachelors. Neither is any girl who has attained puberty (Wingiktóak) allowed near the bladders. She is unclean (Wáhok).

[Pg 29] The Feasts to the Dead

The Eskimo idea of the life after death and the rationale for their most important ritual, the Feast to the Dead, is nowhere better illustrated than in a quaint tale current along the Yukon, in which the heroine, prematurely buried during a trancelike sleep, visited the Land of the Dead. She was rudely awakened from her deathlike slumber by the spirit of her grandmother shaking her and exclaiming, “Wake up. Do not sleep the hours away. You are dead!” Arising from her grave box, the maiden was conducted by her guide to the world beneath, where the dead had their dwellings in large villages grouped according to the localities from which they came. Even the animal shades were not forgotten, but inhabited separate communities in human shape.[19] After some travel the girl found the village allotted to her tribe, and was reclaimed by her departed relatives. She was recognized by the totem marks on her clothing, which in ancient times the Eskimo always wore. She found the inmates of this region leading a pleasant but somewhat monotonous life, free from hardships and from the sleet and cold of their earthly existence. They returned to the upper world during the feasts to the dead, when they received the spiritual essence of the food and clothing offered to their namesakes[20] by relatives. According to the generosity or stinginess of the feast givers there was a feast or a famine in spirit land, and those who were so unfortunate as to have no namesake, either through their [Pg 30] own carelessness[21] or the neglect of the community,[22] went hungry and naked. This was the worst calamity that could befall an Eskimo, hence the necessity of providing a namesake and of regularly feeding and clothing the same, in the interest of the beloved dead.

THE ANNUAL FEAST, AILĪ́GI

The Annual Feast to the Dead is a temporary arrangement, whereby the shades of those recently departed are sustained until the advent of the Great Feast to the Dead. The essence of the offerings of food and drink are supposed to satisfy the wants of the dead until they can be properly honored in the Great Festival. In the latter event the relative discharges all his social obligations to the dead, and the ghost is furnished with such an abundance that it can never want in the world below.

The makers of the feast (nä́skut) are the nearest relatives of those who have died during the past year, together with those villagers who have not yet given the greater festival. The day before the festival the male mourners go to the village burial ground and plant a newly made stake before the grave of their relative. The stake is surmounted by a wooden model of a spear, if the deceased be a man; or a wooden dish, if it be a woman. The totem mark of the deceased is carved upon it. In the north simple models of kayak paddles suffice. The sticks are a notification to the spirits in the land of the dead that the time for the festival is at hand. Accordingly they journey to the grave boxes, where they wait, ready to enter the kásgi at the song of invocation. To light their way from the other world lamps are brought into the kásgi and set before their accustomed places. When the invitation song arises they leave their graves and take their places in the fireplace (Kenéthluk), where they enjoy the songs and dances, and receive the offerings of their relatives.

[Pg 32] The Annual Feast is celebrated after the Bladder Feast during the December moon. By the Yukon tribes it is repeated just before the opening of spring. During the day of the festival a taboo is placed on all work in the village, particularly that done with any sharp pointed tool which might wound some wandering ghost and bring retribution on the people.

At midday the whole village gathers in the kásgi, and the ceremony begins. Soon the mourners enter bearing great bowls of food and drink which they deposit in the doorway. Then the chorus leader arises and begins the song of invitation accompanied by the relatives of the dead. It is a long minor chant, a constant reiteration of a few well worn phrases.

“Tukomalra-ā-, tung lík-a,

tis-ká-a a-a-yung-a-a-yung-a, etc.

Dead ones, next of kin,

come hither,

Túntum komúga thetámtatuk,

móqkapik thetámtatuk moqsúlthka.

Reindeer meat we bring you,

water we bring you for your thirst.”

When the song is completed the mourners arise, and going to the food in the doorway set it on the planks over the fireplace, after which they take a ladleful from each dish pouring it through the cracks in the floor, and the essence of this offering supplies the shades below with food until the next festival. The remainder of the food is distributed among those present. When the feast is over, the balance of the day is given over to songs and dances. Then the spirits are sent back to their homes by the simple expedient of stamping on the floor.

THE GREAT FEAST, AÍTHUKĀ́TUKHTUK

After making offerings to his relative at the annual feast the chief mourner begins saving up his skins, frozen meat, and other delicacies prized by the Eskimo, until, in the course of years, he has accumulated an enormous amount of food and clothing. Then he is prepared to give the great feast in honor of his kinsman. Others in the village, who are bereaved, have been doing the same thing. They meet and agree on a certain time to celebrate the feast together during the ensuing year. The time chosen is usually in January after the local feasts are over, and visitors from neighboring tribes are free to attend. There are no set intervals between these feasts as has been generally supposed. They are celebrated at irregular intervals according to the convenience of the givers.

At the minor festival preceding the Great Feast, the usual invitation stakes planted before the dead are supplemented by others placed before the graves of those in whose honor the festival is to be given. On these is a painted model of the totemic animals of the deceased. The feast giver sings an especial song of invitation, requesting the dead kinsman to be present at the approaching feast.

On the first day of the Great Feast the villagers welcome the guests. Early in the morning they begin to arrive. The messenger goes out on the ice and leads them into the village, showing each where to tie his team. During the first day the guests are fed in the kásgi. They have the privilege of demanding any delicacy they wish. After this they are quartered on various homes in the village. Salmon or meat [Pg 34] must also be provided for their dogs. This is no small item, and often taxes the resources of a village to the utmost. I have known of a village so poor after a period of prolonged hospitality that it was reduced to starvation rations for the rest of the winter.

Immediately on tying up their dogs, the guests go to the kásgi. On entering each one cries in set phraseology, “Ah-ka-ká Píatin, Pikeyútum.” “Oh, ho! Look here! A trifling present.” He throws his present on a common pile in front of the headman, who distributes them among the villagers. It is customary to make the presents appear as large as possible. One fellow has a bolt of calico which he unwinds through the entrance hole, making a great display. It may be thirty yards long. Sometimes they accompany the gift with a short dance. It is considered bad form for one coming from a distance[23] not to make the usual present, as in this way he purchases the right to join in the festival dances.

As soon as all are gathered in the kásgi, a feast is brought in for the tired travelers. Kantags of sealmeat, the blackskin of the bowhead, salmon berries swimming in oil, greens from the hillsides, and pot after pot of tea take off the edge of hunger. After gorging themselves, the guests seem incapable of further exertion, and the remainder of the day is spent in visiting.

The Feast Givers

The feast givers or nä́skut assemble in the kásgi the second day, and the ceremony proper begins. They range themselves around the púgyarok or entrance, the chorus and guests occupying [Pg 35] the back of the room and the spectators packing themselves against the walls.

Each feast giver is garbed according to the sex of his dead relative, not his own, so that some men wear women’s clothes and vice versa. Each bears in his right hand a wand about two feet long (Kelézruk).[24] This is a small stick of wood surmounted with tufts of down from ptarmigan (Okozregéwik). All are dressed to represent the totem to which the deceased belongs. One wears a fillet and armlet of wolfskin (Egóalik); others wear armlets of ermine (Táreak); still others are crowned with feathers of the raven (Tulúa) or the hawk (Tciakaúret).[25] After a short dance they withdraw and the day’s ceremony is finished.

The following day the nä́skut assemble again, but they have doffed their fine feathers, and are dressed in their oldest clothes. The suits of the day before they carry in a grass sack. They wear raincoats of sealgut tied about the waist with a belt of dogskin, and enter the kásgi with eyes cast on the floor. Even in the dances they keep their faces from the audience.

This attitude of humility is in accord with Eskimo ethics. They say that if they adopt a boastful air and fail to give as many presents as the other nä́skut they will be ashamed. So they safeguard themselves in advance.

The Ritual

Advancing with downcast eyes, the nä́skut creep softly across the kásgi and take their places before the funeral lamps. Then taking out their festival garments, they slip them on. [Pg 36] Immediately the drummers start tapping lightly on their drums, and at a signal from their leader the song of invitation begins. Each nä́skuk advances in turn, invoking the presence of his dead in a sad minor strain.

Toakóra ílyuga takína

Dead brother, come hither

A-yunga-ayunga-a-yunga.

Or:

Nuleága awúnga toakóra

Sister mine, dead one,

Takína, núleaga, takína,

Come hither, sister, come hither.

Or:

Akága awúnga takína

Mother mine, come hither.

Nanáktuk, takína,

We wait for you, come hither.

To which the chorus answer:

Ilyúga awúnga takína,

Our brother, come hither,

Takináka, ilyúga, takínaka,

Return, dead brother, return.

The women advance in line, holding their wands in the right hand, and singing in unison; then the men advance in their turn, then both nä́skut and chorus sing together:

Takinaka, awúnga, tungalika,

Return to us, our dead kinsmen,

Nanakátuk, kineáktuk tungalíka

We wait your home coming, our dead kinsmen.

[Pg 37] Suddenly the drummers cease and rap sharply on the inǵlak with their drumsticks. The dancers stop in the midst of their movements and stamp on the floor, first with one foot then with the other, placing their hands on their shoulders, bringing them down over their bodies as though wiping off some unseen thing. Then they slap their thighs and sit down. I am informed that this is to “wipe off” any uncleanness (wahok) that might offend the shades of the dead.

Then the namesakes of the dead troop into the kásgi, and take their places in the center of the room between the two lines. To each, the nä́skuk hands a bowl of water and a kantag of frozen reindeer meat cut into small pieces. The namesakes drop a small portion of the meat on the floor. The essence is evidently thought to pass below to the waiting inua. Then they finish the remainder. At the same time a large amount of frozen meat and fish is brought in and distributed among the guests. This is done at the end of each day.

The fourth day the chorus leader mounts the top of the kásgi and begins again the invitation song. The people scatter to the burying ground or to the ice along the shore according to the spot where they have lain their dead. They dance among the grave boxes so that the shades who have returned to them, when not in the kásgi, may see that they are doing them honor.

During the dancing the children of the village gather in the kásgi, carrying little kantags and sealskin sacks. The women on returning bring great bags of frozen blueberries and reindeer fat, commonly called “Eskimo Ice Cream,” with which they fill the bowls of the children, but the young rogues immediately slip their portions into their sacks (póksrut) and hold out their dishes for more, crying in a deafening chorus, “Wunga-Tū́k” (Me too). This part of the festival [Pg 38] is thoroughly enjoyed by the Eskimo, who idolize their children.

At the conclusion of the day’s feast many presents are given away by the nä́skut, the husbands of the female feast givers distributing them for the ladies, who assume a bashful air. During the distribution the nä́skut maintain their deprecatory attitude and pass disparaging remarks on their gifts. Sometimes the presents are attached to a long line of óklinok (seal thong) which the nä́skut haul down through the smokehole, making the line appear as long as possible. At the same time they sing in a mournful key bewailing their relative:

Ah-ka- ilyúga toakóra, tákin,

Oh! oh! dead brother, return,

Utiktutátuk, ilyúga awúnga,

Return to us, our brother,

Illearúqtutuk, ilyúga,

We miss you, dear brother,

Pikeyútum, kokítutuk,

A trifling present we bring you.

The Clothing of the Namesakes

The following day occurs the clothing of the namesakes. This is symbolical of clothing the dead, who ascend into the bodies of their namesakes during the ceremony and take on the spiritual counterpart of the clothing.

After a grand distribution of presents by the nä́skut, bags of fine clothing are lowered to the feast givers and the namesakes take the center of the floor, in front of their relatives, the feast givers. Then each nä́skuk calls out to the particular namesake of his dead kinsman: “Ītakín, illorahug-náka,” [Pg 39] “Come hither, my beloved,” and proceeds to remove the clothing of the namesake and put on an entirely new suit of mukluks, trousers, and parka, made of the finest furs. Then the feast giver gathers up the discarded clothing, and stamps vigorously on the floor, bidding the ghost begone to its resting place. It goes, well satisfied, and the dancers disperse until another great festival. Until the feast is concluded no one can leave the village.

THE INVITING-IN FESTIVAL

The Inviting-In Festival (Aithúkaguk) is a great inter-tribal feast, second in importance to the Great Feast to the Dead. It is a celebration on invitation from one tribe to her neighbors when sufficient provisions have been collected. It takes place late in the season, after the other festivals are over. Neighboring tribes act as hosts in rotation, each striving to outdo the other in the quality and quantity of entertainment offered. During this festival the dramatic pantomime dances for which the Alaskan Eskimo are justly famous, are performed by especially trained actors. For several days the dances continue, each side paying the forfeit as they lose in the dancing contests. In this respect the representations are somewhat similar to the nith contests of the Greenlanders. As I have noticed the dances at length elsewhere,[26] I shall only give a brief survey here, sufficient to show their place in the Eskimo festival dances.

The main dances of the Inviting-In Festival are totemic in character, performed by trained actors to appease the totems of the hunters, and insure success for the coming season. These are danced in pantomime and depict the life of arctic animals, the walrus, raven, bear, ptarmigan, and others. Then there are group dances which illustrate hunting scenes, like the Reindeer and Wolf Pack dance already described, also dances of a purely comic character, designed for the entertainment of the guests. During the latter performances the side which laughs has to pay a forfeit.

[Pg 41] Elaborate masks are worn in all of the dances. The full paraphernalia, masks, handmasks, fillets, and armlets, are worn by the chief actors. They are supported by richly garbed assistants. An old shaman acts as master of ceremonies. There is an interchange of presents between the tribes during the intervals but not between individuals, as in the Asking Festival. At the close of the festival the masks are burned.

KEY TO PLATE XI

A—Outer Vestibule. (Lā´torăk.)

B—Summer Entrance. (Amēk´.)

C—Front Platform. (Ṓaklim.) Seat of Orphans and Worthless.

D—Plank Floor. (Nā´tūk.)

E—Rear Platform. (Kā´an.) Seat of Honored Guests.

F—Smoke Hole. (Ṙa´lŏk.) Entrance for Gift-lines.

G—Entrance Hole. (Pug´yărăk.)

H—Fireplace. (Kēne´thluk.) Seat of Spirit-Guests.

I—Underground Tunnel. (Ag´vēak.)

J—Side Platforms. (Kā́aklim.) Seats for Spectators.

K—Chorus of Drummers.

L—Feast Givers. (Nä´skut.)

M—Namesakes of Dead.

KEY TO PLATE XII

A—First Movement. The Chief’s Son, Okvaíok is dancing.

B—Second Movement.

ANTHR. PUB. UNIV. MUSEUM VOL. VI PLATE XII

A

A

B

B

MEN’S DANCE

KEY TO PLATE XIII

C—Third Movement.

D—Fourth Movement.

ANTHR. PUB. UNIV. MUSEUM VOL. VI PLATE XIII

C

C

D

D

MEN’S DANCE

KEY TO PLATE XIV

Children’s Dance.

The Chorus. Leader in Center Beating Time With an Ermine Stick.

ANTHR. PUB. UNIV. MUSEUM VOL. VI PLATE XIV

CHILDREN’S DANCE

CHILDREN’S DANCE

THE CHORUS

THE CHORUS

KEY TO PLATE XV

Women’s Dance.

ANTHR. PUB. UNIV. MUSEUM VOL. VI PLATE XV

WOMEN’S DANCE

WOMEN’S DANCE