Title: Hopes and Fears

Author: Charlotte M. Yonge

Release date: July 31, 2008 [eBook #26156]

Language: English

Credits: This ebook was transcribed by Les Bowler

This ebook was transcribed by Les Bowler.

or

SCENES FROM THE LIFE OF A SPINSTER

by

CHARLOTTE M. YONGE

ILLUSTRATED BY HERBERT GANDY

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

new york: the macmillan company

1899

All rights reserved

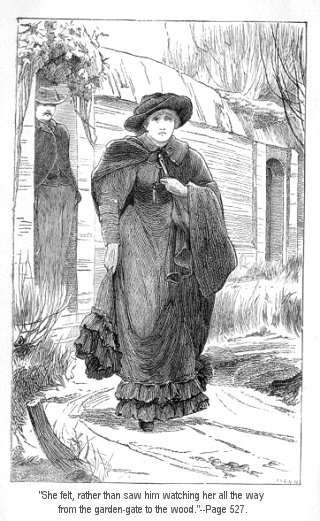

“She felt, rather than saw him watching her all the way from the garden-gate to the wood.” |

Frontispiece |

“I find I can’t spare you, Honora; you had better stay at the Holt for good.” |

Page 11 |

“He drew the paper before him. Lucilla started to her feet.” |

Page 296 |

Who ought to go then and who ought to stay!

Where do you draw an obvious border line?Cecil and Mary

Among the numerous steeples counted from the waters of the Thames, in the heart of the City, and grudged by modern economy as cumberers of the soil of Mammon, may be remarked an abortive little dingy cupola, surmounting two large round eyes which have evidently stared over the adjacent roofs ever since the Fire that began at Pie-corner and ended in Pudding-lane.

Strange that the like should have been esteemed the highest walk of architecture, and yet Honora Charlecote well remembered the days when St. Wulstan’s was her boast, so large, so clean, so light, so Grecian, so far surpassing damp old Hiltonbury Church. That was at an age when her enthusiasm found indiscriminate food in whatever had a hold upon her affections, the nearer her heart being of course the more admirable in itself, and it would be difficult to say which she loved the most ardently, her city home in Woolstone-lane, or Hiltonbury Holt, the old family seat, where her father was a welcome guest whenever his constitution required relaxation from the severe toils of a London rector.

Woolstone-lane was a locality that sorely tried the coachmen of Mrs. Charlecote’s West End connections, situate as it was on the very banks of the Thames, and containing little save offices and warehouses, in the midst of which stood Honora’s home. It was not the rectory, but had been inherited from City relations, and it antedated the Fire, so that it was one of the most perfect remnants of the glories of the merchant princes of ancient London. It had a court to itself, shut in by high walls, and paved with round-headed stones, with gangways of flags in mercy to the feet; the front was faced with hewn squares after the p. 2pattern of Somerset House, with the like ponderous sashes, and on a smaller scale, the Louis XIV. pediment, apparently designed for the nesting-place of swallows and sparrows. Within was a hall, panelled with fragrant softly-tinted cedar wood, festooned with exquisite garlands of fruit and flowers, carved by Gibbons himself, with all his peculiarities of rounded form and delicate edge. The staircase and floor were of white stone, tinted on sunny days with reflections from the windows’ three medallions of yellow and white glass, where Solomon, in golden mantle and crowned turban, commanded the division of a stout lusty child hanging by one leg; superintended the erection of a Temple worthy of Haarlem; or graciously welcomed a recoiling stumpy Vrow of a Queen of Sheba, with golden hair all down her back.

The river aspect of the house had come to perfection at the Elizabethan period, and was sculptured in every available nook with the chevron and three arrows of the Fletchers’ Company, and a merchant’s mark, like a figure of four with a curly tail. Here were the oriel windows of the best rooms, looking out on a grassplat, small enough in country eyes, but most extensive for the situation, with straight gravelled walks, and low lilac and laburnum trees, that came into profuse blossom long before their country cousins, but which, like the crocuses and snowdrops of the flower borders, had better be looked at than touched by such as dreaded sooty fingers. These shrubs veiled the garden from the great river thoroughfare, to which it sloped down, still showing traces of the handsome stone steps and balustrade that once had formed the access of the gold-chained alderman to his sumptuous barge.

Along those paths paced, book in hand, a tall, well-grown maiden, of good straight features, and clear, pale skin, with eyes and rich luxuriant hair of the same colour, a peculiarly bright shade of auburn, such as painters of old had loved, and Owen Sandbrook called golden, while Humfrey Charlecote would declare he was always glad to see Honor’s carrots.

More than thirty years ago, personal teaching at a London parish school or personal visiting of the poor was less common than at present, but Honora had been bred up to be helpful, and she had newly come in from a diligent afternoon of looking at the needlework, and hearing Crossman’s Catechism and Sellon’s Abridgment from a demurely dressed race of little girls in tall white caps, bibs and tuckers, and very stout indigo-blue frocks. She had been working hard at the endeavour to make the little Cockneys, who had never seen a single ear of wheat, enter into Joseph’s dreams, and was rather weary of their town sharpness coupled with their indifference and want of imagination, where any nature, save human nature, was concerned. ‘I will bring an ear of Hiltonbury wheat home with me—some of the best girls shall see me sow it, and I will take them to watch it growing up—the blade, the ear, the full corn in the ear—poor dears, if they only had a Hiltonbury to give them some tastes that p. 3are not all for this hot, busy, eager world! If I could only see one with her lap full of bluebells; but though in this land of Cockaigne of ours, one does not actually pick up gold and silver, I am afraid they are our flowers, and the only ones we esteem worth the picking; and like old Mr. Sandbrook, we neither understand nor esteem those whose aims are otherwise! Oh! Owen, Owen, may you only not be withheld from your glorious career! May you show this hard, money-getting world that you do really, as well as only in word, esteem one soul to be reclaimed above all the wealth that can be laid at your feet! The nephew and heir of the great Firm voluntarily surrendering consideration, ease, riches, unbounded luxury for the sake of the heathen—choosing a wigwam instead of a West End palace; parched maize rather than the banquet; the backwoods instead of the luxurious park; the Red Indian rather than the club and the theatre; to be a despised minister rather than a magnate of this great city; nay, or to take his place among the influential men of the land. What has this worn, weary old civilization to offer like the joy of sitting beneath one of the glorious aspiring pines of America, gazing out on the blue waters of her limpid inland seas, in her fresh pure air, with the simple children of the forest round him, their princely forms in attitudes of attention, their dark soft liquid eyes fixed upon him, as he tells them “Your Great Spirit, Him whom ye ignorantly worship, Him declare I unto you,” and then, some glorious old chief bows his stately head, and throws aside his marks of superstition. “I believe,” he says, and the hearts of all bend with him; and Owen leads them to the lake, and baptizes them, and it is another St. Sacrament! Oh! that is what it is to have nobleness enough truly to overcome the world, truly to turn one’s back upon pleasures and honours—what are they to such as this?’

So mused Honora Charlecote, and then ran indoors, with bounding step, to her Schiller, and her hero-worship of Max Piccolomini, to write notes for her mother, and practise for her father the song that was to refresh him for the evening.

Nothing remarkable! No; there was nothing remarkable in Honor, she was neither more nor less than an average woman of the higher type. Refinement and gentleness, a strong appreciation of excellence, and a love of duty, had all been brought out by an admirable education, and by a home devoted to unselfish exertion, varied by intellectual pleasures. Other influences—decidedly traceable in her musings—had shaped her principles and enthusiasms on those of an ardent Oxonian of the early years of William IV.; and so bred up, so led by circumstances, Honora, with her abilities, high cultivation, and tolerable sense, was a fair specimen of what any young lady might be, appearing perhaps somewhat in advance of her contemporaries, but rather from her training than from intrinsic force of character. The qualities of womanhood well developed, were so entirely the staple of her composition, that there is p. 4little to describe in her. Was not she one made to learn; to lean; to admire; to support; to enhance every joy; to soften every sorrow of the object of her devotion?

* * * * *

Another picture from Honora Charlecote’s life. It is about half after six, on a bright autumnal morning; and, rising nearly due east, out of a dark pine-crowned hill, the sun casts his slanting beams over an undulating country, clothed in gray mist of tints differing with the distance, the farther hills confounded with the sky, the nearer dimly traced in purple, and the valleys between indicated by the whiter, woollier vapours that rise from their streams, a goodly land of fertile field and rich wood, cradled on the bosoms of those soft hills.

Nestled among the woods, clothing its hollows on almost every side, rises a low hill, with a species of table land on the top, scattered over with large thorns and scraggy oaks that cast their shadows over the pale buff bents of the short soft grass of the gravelly soil. Looking southward is a low, irregular, old-fashioned house, with two tall gable ends like eyebrows, and the lesser gable of a porch between them, all covered with large chequers of black timber, filled up with cream-coloured cement. A straight path leads from the porch between beds of scarlet geraniums, their luxuriant horse-shoe leaves weighed down with wet, and china asters, a drop in every quilling, to an old-fashioned sun-dial, and beside that dial stands Honora Charlecote, gazing joyously out on the bright morning, and trying for the hundredth time to make the shadow of that green old finger point to the same figure as the hand of her watch.

‘Oh! down, down, there’s a good dog, Fly; you’ll knock me down! Vixen, poor little doggie, pray! Look at your paws,’ as a blue greyhound and rough black terrier came springing joyously upon her, brushing away the silver dew from the shaven lawn.

‘Down, down, lie down, dogs!’ and with an obstreperous bound, Fly flew to the new-comer, a young man in the robust strength of eight-and-twenty, of stalwart frame, very broad in the chest and shoulders, careless, homely, though perfectly gentleman-like bearing, and hale, hearty, sunburnt face. It was such a look and such an arm as would win the most timid to his side in certainty of tenderness and protection, and the fond voice gave the same sense of power and of kindness, as he called out, ‘Holloa, Honor, there you are! Not given up the old fashion?’

‘Not till you give me up, Humfrey,’ she said, as she eagerly laid her neatly gloved fingers in the grasp of the great, broad, horny palm, ‘or at least till you take your gun.’

‘So you are not grown wiser?’

‘Nor ever will be.’

‘Every woman ought to learn to saddle a horse and fire off a gun.’

p. 5‘Yes, against the civil war squires are always expecting. You shall teach me when the time comes.’

‘You’ll never see that time, nor any other, if you go out in those thin boots. I’ll fetch Sarah’s clogs; I suppose you have not a reasonable pair in the world.’

‘My boots are quite thick, thank you.’

‘Brown paper!’ And indeed they were a contrast to his mighty nailed soles, and long, untanned buskins, nor did they greatly resemble the heavy, country-made galoshes which, with an elder brother’s authority, he forced her to put on, observing that nothing so completely evinced the Londoner as her obstinacy in never having a pair of shoes that could keep anything out.

‘And where are you going?’

‘To Hayward’s farm. Is that too far for you? He wants an abatement of his rent for some improvements, and I want to judge what they may be worth.’

‘Hayward’s—oh, not a bit too far!’ and holding up her skirts, she picked her way as daintily as her weighty chaussure would permit, along the narrow green footway that crossed the expanse of dewy turf in which the dogs careered, getting their noses covered with flakes of thick gossamer, cemented together by dew. Fly scraped it off with a delicate forepaw, Vixen rolled over, and doubly entangled it in her rugged coat. Humfrey Charlecote strode on before his companion with his hands in his pockets, and beginning to whistle, but pausing to observe, over his shoulder, ‘A sweet day for getting up the roots! You’re not getting wet, I hope?’

‘I couldn’t through this rhinoceros hide, thank you. How exquisitely the mist is curling up, and showing the church-spire in the valley.’

‘And I suppose you have been reading all manner of books?’

‘I think the best was a great history of France.’

‘France!’ he repeated in a contemptuous John Bull tone.

‘Ay, don’t be disdainful; France was the centre of chivalry in the old time.’

‘Better have been the centre of honesty.’

‘And so it was in the time of St. Louis and his crusade. Do you know it, Humfrey?’

‘Eh?’

That was full permission. Ever since Honora had been able to combine a narration, Humfrey had been the recipient, though she seldom knew whether he attended, and from her babyhood upwards had been quite contented with trotting in the wake of his long strides, pouring out her ardent fancies, now and then getting an answer, but more often going on like a little singing bird, through the midst of his avocations, and quite complacent under his interruptions of calls to his dogs, directions to his labourers, and warnings to her to mind her feet and not her chatter. In the full stream of crusaders, he led her down one of the multitude of by-paths cleared out in the hazel coppice p. 6for sporting; here leading up a rising ground whence the tops of the trees might be overlooked, some flecked with gold, some blushing into crimson, and beyond them the needle point of the village spire, the vane flashing back the sun; there bending into a ravine, marshy at the bottom, and nourishing the lady fern, then again crossing glades, where the rabbits darted across the path, and the battle of Damietta was broken into by stern orders to Fly to come to heel, and the eating of the nuts which Humfrey pulled down from the branches, and held up to his cousin with superior good nature.

‘A Mameluke rushed in with a scimitar streaming with blood, and—’

‘Take care; do you want help over this fence?’

‘Not I, thank you—And said he had just murdered the king—’

‘Vic! ah! take your nose out of that. Here was a crop, Nora.’

‘What was it?’

‘You don’t mean that you don’t know wheat stubble?’

‘I remember it was to be wheat.’

‘Red wheat, the finest we ever had in this land; not a bit beaten down, and the colour perfectly beautiful before harvest; it used to put me in mind of your hair. A load to the acre; a fair specimen of the effect of drainage. Do you remember what a swamp it was?’

‘I remember the beautiful loose-strifes that used to grow in that corner.’

‘Ah! we have made an end of that trumpery.’

‘You savage old Humfrey—beauties that they were.’

‘What had they to do with my cornfields? A place for everything and everything in its place—French kings and all. What was this one doing wool-gathering in Egypt?’

‘Don’t you understand, it had become the point for the blow at the Saracen power. Where was I? Oh, the Mameluke justified the murder, and wanted St. Louis to be king, but—’

‘Ha! a fine covey, I only miss two out of them. These carrots, how their leaves are turned—that ought not to be.’

Honora could not believe that anything ought not to be that was as beautiful as the varied rosy tints of the hectic beauty of the exquisitely shaped and delicately pinked foliage of the field carrots, and with her cousin’s assistance she soon had a large bouquet where no two leaves were alike, their hues ranging from the deepest purple or crimson to the palest yellow, or clear scarlet, like seaweed, through every intermediate variety of purple edged with green, green picked out with red or yellow, or vice versâ, in never-ending brilliancy, such as Humfrey almost seemed to appreciate, as he said, ‘Well, you have something as pretty as your weeds, eh, Honor?’

‘I can’t quite give up mourning for my dear long purples.’

‘All very well by the river, but there’s no beauty in things p. 7out of place, like your Louis in Egypt—well, what was the end of this predicament?’

So Humfrey had really heard and been interested! With such encouragement, Honora proceeded swimmingly, and had nearly arrived at her hero’s ransom, through nearly a mile of field paths, only occasionally interrupted by grunts from her auditor at farming not like his own, when crossing a narrow foot-bridge across a clear stream, they stood before a farmhouse, timbered and chimneyed much like the Holt, but with new sashes displacing the old lattice.

‘Oh! Humfrey, how could you bring me to see such havoc? I never suspected you would allow it.’

‘It was without asking leave; an attention to his bride; and now they want an abatement for improvements! Whew!’

‘You should fine him for the damage he has done!’

‘I can’t be hard on him, he is more or less of an ass, and a good sort of fellow, very good to his labourers; he drove Jem Hurd to the infirmary himself when he broke his arm. No, he is not a man to be hard upon.’

‘You can’t be hard on any one. Now that window really irritates my mind.’

‘Now Sarah walked down to call on the bride, and came home full of admiration at the place being so lightsome and cheerful. Which of you two ladies am I to believe?’

‘You ought to make it a duty to improve the general taste! Why don’t you build a model farm-house, and let me make the design?’

‘Ay, when I want one that nobody can live in. Come, it will be breakfast time.’

‘Are not you going to have an interview?’

‘No, I only wanted to take a survey of the alterations; two windows, smart door, iron fence, pulled down old barn, talks of another. Hm!’

‘So he will get his reduction?’

‘If he builds the barn. I shall try to see his wife; she has not been brought up to farming, and whether they get on or not, all depends on the way she may take it up. What are you looking at?’

‘That lovely wreath of Traveller’s Joy.’

‘Do you want it?’

‘No, thank you, it is too beautiful where it is.’

‘There is a piece, going from tree to tree, by the Hiltonbury Gate, as thick as my arm; I just saved it when West was going to cut it down with the copsewood.’

‘Well, you really are improving at last!’

‘I thought you would never let me hear the last of it; besides, there was a thrush’s nest in it.’

By and by the cousins arrived at a field where Humfrey’s portly shorthorns were coming forth after their milking, under the pilotage of an old white-headed man, bent nearly double, p. 8uncovering his head as the squire touched his hat in response, and shouted, ‘Good morning.’

‘If you please, sir,’ said the old man, trying to erect himself, ‘I wanted to speak to you.’

‘Well.’

‘If you please, sir, chimney smokes so as a body can scarce bide in the house, and the blacks come down terrible.’

‘Wants sweeping,’ roared Humfrey, into his deaf ears.

‘Have swep it, sir; old woman’s been up with her broom.’

‘Old woman hasn’t been high enough. Send Jack up outside with a rope and a bunch o’ furze, and let her stand at bottom.’

‘That’s it, sir!’ cried the old man, with a triumphant snap of the fingers over his shoulder. ‘Thank ye!’

‘Here’s Miss Honor, John;’ and Honora came forward, her gravity somewhat shaken by the domestic offices of the old woman.

‘I’m glad to see you still able to bring out the cows, John. Here’s my favourite Daisy as tame as ever.’

‘Ay! ay!’ and he looked at his master for explanation from the stronger and more familiar voice. ‘I be deaf, you see, ma’am.’

‘Miss Honor is glad to see Daisy as tame as ever,’ shouted Humfrey.

‘Ay! ay!’ maundered on the old man; ‘she ain’t done no good of late, and Mr. West and I—us wanted to have fatted her this winter, but the squire, he wouldn’t hear on it, because Miss Honor was such a terrible one for her. Says I, when I hears ’em say so, we shall have another dinner on the la-an, and the last was when the old squire was married, thirty-five years ago come Michaelmas.’

Honora was much disposed to laugh at this freak of the old man’s fancy, but to her surprise Humfrey coloured up, and looked so much out of countenance that a question darted through her mind whether he could have any such step in contemplation, and she began to review the young ladies of the neighbourhood, and to decide on each in turn that it would be intolerable to see her as Humfrey’s wife; more at home at the Holt than herself. She had ample time for contemplation, for he had become very silent, and once or twice the presumptuous idea crossed her that he might be actually about to make her some confidence, but when he at length spoke, very near the house, it was only to say, ‘Honor, I wanted to ask you if you think your father would wish me to ask young Sandbrook here?’

‘Oh! thank you, I am sure he would be glad. You know poor Owen has nowhere to go, since his uncle has behaved so shamefully.’

‘It must have been a great mortification—’

‘To Owen? Of course it was, to be so cast off for his noble purpose.’

‘I was thinking of old Mr. Sandbrook—’

‘Old wretch! I’ve no patience with him!’

p. 9‘Just as he has brought this nephew up and hopes to make him useful and rest some of his cares upon him in his old age, to find him flying off upon this fresh course, and disappointing all his hopes.’

‘But it is such a high and grand course, he ought to have rejoiced in it, and Owen is not his son.’

‘A man of his age, brought up as he has been, can hardly be expected to enter into Owen’s views.’

‘Of course not. It is all sordid and mean, he cannot even understand the missionary spirit of resigning all. As Owen says, half the Scripture must be hyperbole to him, and so he is beginning Owen’s persecution already.’

It was one of Humfrey’s provoking qualities that no amount of eloquence would ever draw a word of condemnation from him; he would praise readily enough, but censure was very rare with him, and extenuation was always his first impulse, so the more Honora railed at Mr. Sandbrook’s interference with his nephew’s plans, the less satisfaction she received from him. She seemed to think that in order to admire Owen as he deserved, his uncle must be proportionably reviled, and though Humfrey did not imply a word save in commendation of the young missionary’s devotion, she went indoors feeling almost injured at his not understanding it; but Honora’s petulance was a very bright, sunny piquancy, and she only appeared the more glowing and animated for it when she presented herself at the breakfast-table, with a preposterous country appetite.

Afterwards she filled a vase very tastefully with her varieties of leaves, and enjoyed taking in her cousin Sarah, who admired the leaves greatly while she thought they came from Mrs. Mervyn’s hothouse; but when she found they were the product of her own furrows, voted them coarse, ugly, withered things, such as only the simplicity of a Londoner could bring into civilized society. So Honora stood over her gorgeous feathery bouquet, not knowing whether to laugh or to be scornful, till Humfrey, taking up the vase, inquired, ‘May I have it for my study?’

‘Oh! yes, and welcome,’ said Honora, laughing, and shaking her glowing tresses at him; ‘I am thankful to any one who stands up for carrots.’

Good-natured Humfrey, thought she, it is all that I may not be mortified; but after all it is not those very good-natured people who best appreciate lofty actions. He is inviting Owen Sandbrook more because he thinks it would please papa, and because he compassionates him in his solitary lodgings, than because he feels the force of his glorious self-sacrifice.

* * * * *

The northern slope of the Holt was clothed with fir plantations, intersected with narrow paths, which gave admission to the depths of their lonely woodland palace, supported on rudely straight columns, dark save for the snowy exuding gum, roofed p. 10in by aspiring beam-like arms, bearing aloft their long tufts of dark blue green foliage, floored by the smooth, slippery, russet needle leaves as they fell, and perfumed by the peculiar fresh smell of turpentine. It was a still and lonely place, the very sounds making the silence more audible (if such an expression may be used), the wind whispering like the rippling waves of the sea in the tops of the pines, here and there the cry of a bird, or far, far away, the tinkle of the sheep-bell, or the tone of the church clock; and of movement there was almost as little, only the huge horse ants soberly wending along their highway to their tall hillock thatched with pine leaves, or the squirrel in the ruddy, russet livery of the scene, racing from tree to tree, or sitting up with his feathery tail erect to extract with his delicate paws the seed from the base of the fir-cone scale. Squirrels there lived to a good old age, till their plumy tails had turned white, for the squire’s one fault in the eyes of keepers and gardeners was that he was soft-hearted towards ‘the varmint.’

A Canadian forest on a small scale, an extremely miniature scale indeed, but still Canadian forests are of pine, and the Holt plantation was fir, and firs were pines, and it was a lonely musing place, and so on one of the stillest, clearest days of ‘St. Luke’s little summer,’ the last afternoon of her visit at the Holt, there stood Honora, leaning against a tree stem, deep, very deep in a vision of the primeval woodlands of the West, their red inhabitants, and the white man who should carry the true, glad tidings westward, westward, ever from east to west. Did she know how completely her whole spirit and soul were surrendered to the worship of that devotion? Worship? Yes, the word is advisedly used; Honora had once given her spirit in homage to Schiller’s self-sacrificing Max; the same heart-whole veneration was now rendered to the young missionary, multiplied tenfold by the hero being in a tangible, visible shape, and not by any means inclined to thwart or disdain the allegiance of the golden-haired girl. Nay, as family connections frequently meeting, they had acted upon each other’s minds more than either knew, even when the hour of parting had come, and words had been spoken which gave Honora something more to cherish in the image of Owen Sandbrook than even the hero and saint. There then she stood and dreamt, pensive and saddened indeed, but with a melancholy trenching very nearly on happiness in the intensity of its admiration, and the vague ennobling future of devoted usefulness in which her heart already claimed to share, as her person might in some far away period on which she could not dwell.

A sound approached, a firm footstep, falling with strong elasticity and such regular cadences, that it seemed to chime in with the pine-tree music, and did not startle her till it came so near that there was distinctive character to be discerned in the tread, and then with a strange, new shyness, she would have p. 11slipped away, but she had been seen, and Humfrey, with his timber race in his hand, appeared on the path, exclaiming, ‘Ah, Honor, is it you come out to meet me, like old times? You have been so much taken up with your friend Master Owen that I have scarcely seen you of late.’

Honor did not move away, but she blushed deeply as she said, ‘I am afraid I did not come to meet you, Humfrey.’

‘No? What, you came for the sake of a brown study? I wish I had known you were not busy, for I have been round all the woods marking timber.’

‘Ah!’ said she, rousing herself with some effort, ‘I wonder how many trees I should have saved from the slaughter. Did you go and condemn any of my pets?’

‘Not that I know of,’ said Humfrey. ‘I have touched nothing near the house.’

‘Not even the old beech that was scathed with lightning? You know papa says that is the touchstone of influence; Sarah and Mr. West both against me,’ laughed Honora, quite restored to her natural manner and confiding ease.

‘The beech is likely to stand as long as you wish it,’ said Humfrey, with an unaccustomed sort of matter-of-fact gravity, which surprised and startled her, so as to make her bethink herself whether she could have behaved ill about it, been saucy to Sarah, or the like.

‘Thank you,’ she said; ‘have I made a fuss—?’

‘No, Honor,’ he said, with deliberate kindness, shutting up his knife, and putting it into his pocket; ‘only I believe it is time we should come to an understanding.’

More than ever did she expect one of his kind remonstrances, and she looked up at him in expectation, and ready for defence, but his broad, sunburnt countenance looked marvellously heated, and he paused ere he spoke.

‘I find I can’t spare you, Honora; you had better stay at the Holt for good.’ Her cheeks flamed, and her heart galloped, but she could not let herself understand.

‘Honor, you are old enough now, and I do not think you need fear. It is almost your home already, and I believe I can make you happy, with the blessing of God—’ He paused, but as she could not frame an answer in her consternation, continued, ‘Perhaps I should not have spoken so suddenly, but I thought you would not mind me; I should like to have had one word from my little Honor before I go to your father, but don’t if you had rather not.’

‘Oh, don’t go to papa, please don’t,’ she cried, ‘it would only make him sorry.’

Humfrey stood as if under an unexpected shock.

‘Oh! how came you to think of it?’ she said in her distress; ‘I never did, and it can never be—I am so sorry!’

‘Very well, my dear, do not grieve about it,’ said Humfrey, only bent on soothing her; ‘I dare say you are quite right, you p. 12are used to people in London much more suitable to you than a stupid homely fellow like me, and it was a foolish fancy to think it might be otherwise. Don’t cry, Honor dear, I can’t bear that!’

‘Oh, Humfrey, only understand, please! You are the very dearest person in the world to me after papa and mamma; and as to fine London people, oh no, indeed! But—’

‘It is Owen Sandbrook; I understand,’ said Humfrey, gravely.

She made no denial.

‘But, Honor,’ he anxiously exclaimed, ‘you are not going out in this wild way among the backwoods, it would break your mother’s heart; and he is not fit to take care of you. I mean he cannot think of it now.’

‘O no, no, I could not leave papa and mamma; but some time or other—’

‘Is this arranged? Does your father know it?’

‘Oh, Humfrey, of course!’

‘Then it is an engagement?’

‘No,’ said Honora, sadly; ‘papa said I was too young, and he wished I had heard nothing about it. We are to go on as if nothing had happened, and I know they think we shall forget all about it! As if we could! Not that I wish it to be different. I know it would be wicked to desert papa and mamma while she is so unwell. The truth is, Humfrey,’ and her voice sank, ‘that it cannot be while they live.’

‘My poor little Honor!’ he said, in a tone of the most unselfish compassion.

She had entirely forgotten his novel aspect, and only thought of him as the kindest friend to whom she could open her heart.

‘Don’t pity me,’ she said in exultation; ‘think what it is to be his choice. Would I have him give up his aims, and settle down in the loveliest village in England? No, indeed, for then it would not be Owen! I am happier in the thought of him than I could be with everything present to enjoy.’

‘I hope you will continue to find it so,’ he said, repressing a sigh.

‘I should be ashamed of myself if I did not,’ she continued with glistening eyes. ‘Should not I have patience to wait while he is at his real glorious labour? And as to home, that’s not altered, only better and brighter for the definite hope and aim that will go through everything, and make me feel all I do a preparation.’

‘Yes, you know him well,’ said Humfrey; ‘you saw him constantly when he was at Westminster.’

‘O yes, and always! Why, Humfrey, it is my great glory and pleasure to feel that he formed me! When he went to Oxford, he brought me home all the thoughts that have been my better life. All my dearest books we read together, and what used to look dry and cold, gained light and life after he touched it.’

His tone reminded her of what had passed, and she said, timidly, ‘I forgot! I ought not! I have vexed you, Humfrey.’

‘No,’ he said, in his full tender voice; ‘I see that it was vain to think of competing with one of so much higher claims. If he goes on in the course he has chosen, yours will have been a noble choice, Honor; and I believe,’ he added, with a sweetness of smile that almost made her forgive the if, ‘that you are one to be better pleased so than with more ordinary happiness. I have no doubt it is all right.’

‘Dear Humfrey, you are so good!’ she said, struck with his kind resignation, and utter absence of acerbity in his disappointment.

‘Forget this, Honora,’ he said, as they were coming to the end of the pine wood; ‘let us be as we were before.’

Honora gladly promised, and excepting for her wonder at such a step on the part of the cousin whose plaything and pet she had hitherto been, she had no temptation to change her manner. She loved him as much as ever, but only as a kind elder brother, and she was glad that he was wise enough to see his immeasurable inferiority to the young missionary. It was a wonderful thing, and she was sorry for his disappointment; but after all, he took it so quietly that she did not think it could have hurt him much. It was only that he wanted to keep his pet in the country. He was not capable of love like Owen Sandbrook’s.

* * * * *

Years passed on. Rumour had bestowed Mr. Charlecote of Hiltonbury on every lady within twenty miles, but still in vain. His mother was dead, his sister married to an old college fellow, who had waited half a lifetime for a living, but still he kept house alone.

And open house it was, with a dinner-table ever expanding for chance guests, strawberry or syllabub feasts half the summer, and Christmas feasts extending wide on either side of the twelve days. Every one who wanted a holiday was free of the Holt; young sportsmen tried their inexperienced guns under the squire’s patient eye; and mammas disposed of their children for weeks together, to enjoy the run of the house and garden, and rides according to age, on pony, donkey, or Mr. Charlecote. No festivity in the neighbourhood was complete without his sunshiny presence; he was wanted wherever there was any family event; and was godfather, guardian, friend, and adviser of all. Every one looked on him as a sort of exclusive property, yet he had room in his heart for all. As a magistrate, he was equally indispensable in county government, and a charity must be undeserving indeed that had not Humfrey Charlecote, Esq., on the committee. In his own parish he was a beneficent monarch; on his own estate a mighty farmer, owning that his relaxation and delight were his turnips, his bullocks, and machines; and p. 14so content with them, and with his guests, that Honora never recollected that walk in the pine woods without deciding that to have monopolized him would have been an injury to the public, and perhaps less for his happiness than this free, open-hearted bachelor life. Seldom did she recall that scene to mind, for she had never been by it rendered less able to trust to him as her friend and protector, and she stood in need of his services and his comfort, when her father’s death had left him the nearest relative who could advise or transact business for her and her mother. Then, indeed, she leant on him as on the kindest and most helpful of brothers.

Mrs. Charlecote was too much acclimatized to the city to be willing to give up her old residence, and Honor not only loved it fondly, but could not bear to withdraw from the local charities where her tasks had hitherto lain; and Woolstone-lane, therefore, continued their home, though the summer and autumn usually took them out of London.

Such was the change in Honora’s outward life. How was it with that inmost shrine where dwelt her heart and soul? A copious letter writer, Owen Sandbrook’s correspondence never failed to find its way to her, though they did not stand on such terms as to write to one another; and in those letters she lived, doing her day’s work with cheerful brightness, and seldom seeming preoccupied, but imagination, heart, and soul were with his mission.

Very indignant was she when the authorities, instead of sending him to the interesting children of the forests, thought proper to waste him on mere colonists, some of them Yankee, some Presbyterian Scots. He was asked insolent, nasal questions, his goods were coolly treated as common property, and it was intimated to him on all hands that as Englishman he was little in their eyes, as clergyman less, as gentleman least of all. Was this what he had sacrificed everything for?

By dint of strong complaints and entreaties, after he had quarrelled with most of his flock, he accomplished an exchange into a district where red men formed the chief of his charge; and Honora was happy, and watched for histories of noble braves, gallant hunters, and meek-eyed squaws.

Slowly, slowly she gathered that the picturesque deer-skins had become dirty blankets, and that the diseased, filthy, sophisticated savages were among the worst of the pitiable specimens of the effect of contact with the most evil side of civilization. To them, as Owen wrote, a missionary was only a white man who gave no brandy, and the rest of his parishioners were their obdurate, greedy, trading tempters! It had been a shame to send him to such a hopeless set, when there were others on whom his toils would not be thrown away. However, he should do his best.

And Honor went on expecting the wonders his best would work, only the more struck with admiration by hearing that p. 15the locality was a swamp of luxuriant vegetation, and equally luxuriant fever and ague; and the letter he wrote thence to her mother on the news of their loss did her more good than all Humfrey’s considerate kindness.

Next, he had had the ague, and had gone to Toronto for change of air. Report spoke of Mr. Sandbrook as the most popular preacher who had appeared in Toronto for years, attracting numbers to his pulpit, and sending them away enraptured by his power of language. How beautiful that a man of such talents, always so much stimulated by appreciation, should give up all this most congenial scene, and devote himself to his obscure mission!

Report said more, but Honora gave it no credit till old Mr. Sandbrook called one morning in Woolstone-lane, by his nephew’s desire, to announce to his friends that he had formed an engagement with Miss Charteris, the daughter of a general officer there in command.

Honor sat out all the conversation; and Mrs. Charlecote did not betray herself; though, burning with a mother’s wrath, she did nothing worse than hope they would be happy.

Yet Honor had not dethroned the monarch of her imagination. She reiterated to herself and to her mother that she had no ground of complaint, that it had been understood that the past was to be forgotten, and that Owen was far more worthily employed than in dwelling on them. No blame could attach to him, and it was wise to choose one accustomed to the country and able to carry out his plans. The personal feeling might go, but veneration survived.

Mrs. Charlecote never rested till she had learnt all the particulars. It was a dashing, fashionable family, and Miss Charteris had been the gayest of the gay, till she had been impressed by Mr. Sandbrook’s ministrations. From pope to lover, Honor knew how easy was the transition; but she zealously nursed her admiration for the beauty, who was exchanging her gaieties for the forest missions; she made her mother write cordially, and send out a pretty gift, and treated as a personal affront all reports of the Charteris disapprobation, and of the self-will of the young people. They were married, and the next news that Honora heard was, that the old general had had a fit from passion; thirdly, came tidings that the eldest son, a prosperous M.P., had not only effected a reconciliation, but had obtained a capital living for Mr. Sandbrook, not far from the family seat.

Mrs. Charlecote declared that her daughter should not stay in town to meet the young couple, and Honora’s resistance was not so much dignity, as a feverish spirit of opposition, which succumbed to her sense of duty, but not without such wear and tear of strained cheerfulness and suppressed misery, that when at length her mother had brought her away, the fatigue of the journey completed the work, and she was prostrated for weeks by low fever. The blow had fallen. He had put his hand to p. 16the plough and looked back. Faithlessness towards herself had been passed over unrecognized, faithlessness towards his self-consecration was quite otherwise. That which had absorbed her affections and adoration had proved an unstable, excitable being! Alas! would that long ago she had opened her eyes to the fact that it was her own lofty spirit, not his steadfastness, which had first kept it out of the question that the mission should be set aside for human love. The crash of her idolatry was the greater because it had been so highly pitched, so closely intermingled with the true worship. She was long ill, the past series of disappointments telling when her strength was reduced; and for many a week she would lie still and dreamy, but fretted and wearied, so as to control herself with difficulty when in the slightest degree disturbed, or called upon to move or think. When her strength returned under her mother’s tender nursing the sense of duty revived. She thought her youth utterly gone with the thinning of her hair and the wasting of her cheeks, but her mother must be the object of her care and solicitude, and she would exert herself for her sake, to save her grief, and hide the wound left by the rending away of the jewel of her heart. So she set herself to seem to like whatever her mother proposed, and she acted her interest so well that insensibly it became real. After all, she was but four-and-twenty, and the fever had served as an expression of the feeling that would have its way: she had had a long rest, which had relieved the sense of pent-up and restrained suffering, and vigour and buoyancy were a part of her character; her tone and manner resumed their cheerfulness, her spirits came back, though still with the dreary feeling that the hope and aim of life were gone, when she was left to her own musings; she was little changed, and went on with daily life, contented and lively over the details, and returning to her interest in reading, in art, poetry, and in all good works, while her looks resumed their brightness, and her mother congratulated herself once more on the rounded cheek and profuse curls.

At the year’s end Humfrey Charlecote renewed his proposal. It was no small shock to find herself guilty of his having thus long remained single, and she was touched by his kind forbearance, but there was no bringing herself either to love him, or to believe that he loved her, with such love as had been her vision. The image around which she had bound her heart-strings came between him and her, and again she begged his pardon, and told him she liked him too well as he was to think of him in any other light. Again he, with the most tender patience and humility, asked her to forgive him for having harassed her, and betrayed so little chagrin that she ascribed his offer to generous compassion at her desertion.

He who lets his feelings run

In soft luxurious flow,

Shrinks when hard service must be done,

And faints at every woe.

Seven years more, and Honora was in mourning for her mother. She was alone in the world, without any near or precious claim, those clinging tendrils of her heart rent from their oldest, surest earthly stay, and her time left vacant from her dearest, most constant occupation. Her impulse was to devote herself and her fortune at once to the good work which most engaged her imagination, but Humfrey Charlecote, her sole relation, since heart complaint had carried off his sister Sarah, interfered with the authority he had always exercised over her, and insisted on her waiting one full year before pledging herself to anything. At one-and-thirty, with her golden hair and light figure, her delicate skin and elastic step, she was still too young to keep house in solitude, and she invited to her home a friendless old governess of her own, sick at heart with standing for the Governess’s Institution, promising her a daughter’s care and attendance on her old age. Gentle old Miss Wells was but too happy in her new quarters, though she constantly averred that she knew she should not continue there; treated as injuries to herself all Honor’s assertions of the dignity of age and old maidishness, and remained convinced that she should soon see her married.

Honora had not seen Mr. Sandbrook since his return from Canada, though his living was not thirty miles from the City. There had been exchanges of calls when he had been in London, but these had only resulted in the leaving of cards; and from various causes she had been unable to meet him at dinner. She heard of him, however, from their mutual connection, old Mrs. Sandbrook, who had made a visit at Wrapworth, and came home stored with anecdotes of the style in which he lived, the charms of Mrs. Sandbrook, and the beauty of the children. As far as Honora could gather, and very unwillingly she did so, he was leading the life of an easy-going, well-beneficed clergyman, not neglecting the parish, according to the requirements of the day, indeed slightly exceeding them, very popular, good-natured, and charitable, and in great request in a numerous, demi-suburban neighbourhood, for all sorts of not unclerical gaieties. The Rev. O. Sandbrook was often to be met with in the papers, preaching everywhere and for everything, and whispers went about of his speedy promotion to a situation of greater note. In the seventh year of his marriage, his wife died, and Honora was told of his overwhelming grief, how he utterly refused all comfort or alleviation, and threw himself with all his soul into his parish and his children. People spoke p. 18of him as going about among the poor from morning to night, with his little ones by his side, shrinking from all other society, teaching them and nursing them himself, and endeavouring to the utmost to be as both parents in one. The youngest, a delicate infant, soon followed her mother to the grave, and old Mrs. Sandbrook proved herself to have no parent’s heart by being provoked with his agonizing grief for the ‘poor little sickly thing,’ while it was not in Honora’s nature not to feel the more tenderly towards the idol of her girlish days, because he was in trouble.

It was autumn, the period when leaves fall off and grow damp, and London birds of passage fly home to their smoky nests. Honora, who had gone to Weymouth chiefly because she saw Miss Wells would be disappointed if she did otherwise; when there, had grown happily at home with the waves, and in talking to the old fishermen; but had come back because Miss Wells thought it chilly and dreary, and pined for London warmth and snugness. The noonday sun had found the way in at the oriel window of the drawing-room, and traced the reflection of the merchant’s mark upon the upper pane in distorted outline on the wainscoted wall; it smiled on the glowing tints of Honora’s hair, but seemed to die away against the blackness of her dress, as she sat by the table, writing letters, while opposite, in the brightness of the fire, sat the pale, placid Miss Wells with her morning nest of sermon books and needlework around her.

Honor yawned; Miss Wells looked up with kind anxiety. She knew such a yawn was equivalent to a sigh, and that it was dreary work to settle in at home again this first time without the mother.

Then Honor smiled, and played with her pen-wiper. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘it is comfortable to be at home again!’

‘I hope you will soon be able to feel so, my dear,’ said the kind old governess.

‘I mean it,’ said Honor cheerfully; then sighing, ‘But do you know, Mr. Askew wishes his curates to visit at the asylum instead of ladies.’

Miss Wells burst out into all the indignation that was in her mild nature. Honor not to visit at the asylum founded chiefly by her own father!

‘It is a parish affair now,’ said Honor; ‘and I believe those Miss Stones and their set have been very troublesome. Besides I think he means to change its character.’

‘It is very inconsiderate of him,’ said Miss Wells; ‘he ought to have consulted you.’

‘Every one loves his own charity the best,’ said Honora; ‘Humfrey says endowments are generally a mistake, each generation had better do its own work to the utmost. I wish Mr. Askew had not begun now, it was the work I specially looked to, but I let it alone while—and he cannot be expected—’

p. 19‘I should have expected it of him though!’ exclaimed Miss Wells, ‘and he ought to know better! How have you heard it?’

‘I have a note from him this morning,’ said Honora; ‘he asks me Humfrey Charlecote’s address; you know he and Mr. Sandbrook are trustees,’ and her voice grew the sadder.

‘If I am not much mistaken, Mr. Charlecote will represent to him his want of consideration.’

‘I think not,’ said Honora; ‘I should be sorry to make the clergyman’s hard task here any harder for the sake of my feelings. Late incumbent’s daughters are proverbially inconvenient. No, I would not stand in the way, but it makes me feel as if my work in St. Wulstan’s were done,’ and the tears dropped fast.

‘Dear, dear Honora!’ began the old lady, eagerly, but her words and Honora’s tears were both checked by the sound of a bell, that bell within the court, to which none but intimates found access.

‘Strange! It is the thought of old times, I suppose,’ said Honor, smiling, ‘but I could have said that was Owen Sandbrook’s ring.’

The words were scarcely spoken, ere Mr. Sandbrook and Captain Charteris were announced; and there entered a clergyman leading a little child in each hand. How changed from the handsome, hopeful youth from whom she had parted! Thin, slightly bowed, grief-stricken, and worn, she would scarcely have known him, and as if to hide how much she felt, she bent quickly, after shaking hands with him, to kiss the two children, flaxen-curled creatures in white, with black ribbons. They both shrank closer to their father. ‘Cilly, my love, Owen, my man, speak to Miss Charlecote,’ he said; ‘she is a very old friend of mine. This is my bonny little housekeeper,’ he added, ‘and here’s a sturdy fellow for four years old, is not he?’

The girl, a delicate fairy of six, barely accepted an embrace, and clung the faster to her father, with a gesture as though to repel all advance. The boy took a good stare out of a pair of resolute gray eyes, with one foot in advance, and offered both hands. Honora would have taken him on her knee, but he retreated, and both leant against their father as he sat, an arm round each, after shaking hands with Miss Wells, whom he recollected at once, and presenting his brother-in-law, whose broad, open, sailor countenance, hardy and weather-stained, was a great contrast to his pale, hollow, furrowed cheeks and heavy eyes.

‘Will you tell me your name, my dear?’ said Honora, feeling the children the easiest to talk to; but the little girl’s pretty lips pouted, and she nestled nearer to her father.

‘Her name is Lucilla,’ he answered with a sigh, recalling that it had been his wife’s name. ‘We are all somewhat of little savages,’ he added, in excuse for the child’s silence. ‘We have seen few strangers at Wrapworth of late.’

p. 20‘I did not know you were in London.’

‘It was a sudden measure—all my brother’s doing,’ he said; ‘I am quite taken out of my own guidance.’

‘I went down to Wrapworth and found him very unwell, quite out of order, and neglecting himself,’ said the captain; ‘so I have brought him up for advice, as I could not make him hear reason.’

‘I was afraid you were looking very ill,’ said Honora, hardly daring to glance at his changed face.

‘Can’t help being ill,’ returned Captain Charteris, ‘running about the village in all weathers in a coat like that, and sitting down to play with the children in his wet things. I saw what it would come to, last time.’

Mr. Sandbrook could not repress a cough, which told plainly what it was come to.

Miss Wells asked whom he intended to consult, and there was some talk on physicians, but the subject was turned off by Mr. Sandbrook bending down to point out to little Owen a beautiful carving of a brooding dove on her nest, which formed the central bracket of the fine old mantelpiece.

‘There, my man, that pretty bird has been sitting there ever since I can remember. How like it all looks to old times! I could imagine myself running in from Westminster on a saint’s day.’

‘It is little altered in some things,’ said Honor. The last great change was too fresh!

‘Yes,’ said Mr. Sandbrook, raising his eyes towards her with the look that used to go so deep of old, ‘we have both gone through what makes the unchangeableness of these impassive things the more striking.’

‘I can’t see,’ said the little girl, pulling his hand.

‘Let me lift you up, my dear,’ said Honora; but the child turned her back on her, and said, ‘Father.’

He rose, and was bending, at the little imperious voice, though evidently too weak for the exertion, but the sailor made one step forward, and pouncing on Miss Lucilla, held her up in his arms close to the carving. The two little feet made signs of kicking, and she said in anything but a grateful voice, ‘Put me down, Uncle Kit.’

Uncle Kit complied, and she retreated under her papa’s wing, pouting, but without another word of being lifted, though she had been far too much occupied with struggling to look at the dove. Meantime her brother had followed up her request by saying ‘me,’ and he fairly put out his arms to be lifted by Miss Charlecote, and made most friendly acquaintance with all the curiosities of the carving. The rest of the visit was chiefly occupied by the children, to whom their father was eager to show all that he had admired when little older than they were, thus displaying a perfect and minute recollection and affection for the place, which much gratified Honora. p. 21The little girl began to thaw somewhat under the influence of amusement, but there was still a curious ungraciousness towards all attentions. She required those of her father as a right, but shook off all others in a manner which might be either shyness or independence; but as she was a pretty and naturally graceful child, it had a somewhat engaging air of caprice. They took leave, Mr. Sandbrook telling the children to thank Miss Charlecote for being so kind to them, which neither would do, and telling her, as he pressed her hand, that he hoped to see her again. Honora felt as if an old page in her history had been reopened, but it was not the page of her idolatry, it was that of the fall of her idol! She did not see in him the champion of the truth, but his presence palpably showed her the excitable weakness which she had taken for inspiration, while the sweetness and sympathy warmed her heart towards him, and made her feel that she had underrated his attractiveness. His implications that he knew she sympathized with him had touched her greatly, and then he looked so ill!

A note from old Mrs. Sandbrook begged her to meet him at dinner the next day, and she was glad of the opportunity of learning the doctor’s verdict upon him, though all the time she knew the meeting would be but pain, bringing before her the disappointment not of him, but in him.

No one was in the drawing-room but Captain Charteris, who came and shook hands with her as if they were old friends; but she was somewhat amazed at missing Mrs. Sandbrook, whose formality would be shocked by leaving her guests in the lurch.

‘Some disturbance in the nursery department, I fancy,’ said the captain; ‘those children have never been from home, and they are rather exacting, poor things.’

‘Poor little things!’ echoed Honora; then, anxious to profit by the tête-a-tête, ‘has Mr. Sandbrook seen Dr. L.?’

‘Yes, it is just as I apprehended. Lungs very much affected, right one nearly gone. Nothing for it but the Mediterranean.’

‘Indeed!’

‘It is no wonder. Since my poor sister died he has never taken the most moderate care of his health, perfectly revelled in dreariness and desolateness, I believe! He has had this cough about him ever since the winter, when he walked up and down whole nights with that poor child, and never would hear of any advice till I brought him up here almost by force.’

‘I am sure it was time.’

‘May it be in time, that’s all.’

‘Italy does so much! But what will become of the children?’

‘They must go to my brother’s of course. I have told him I will see him there, but I will not have the children! There’s not the least chance of his mending, if they are to be always lugging him about—’

The captain was interrupted by the entrance of Mrs. Sandbrook, who looked a good deal worried, though she tried to put p. 22it aside, but on the captain saying, ‘I’m afraid that you have troublesome guests, ma’am,’ out it all came, how it had been discovered late in the day that Master Owen must sleep in his papa’s room, in a crib to himself, and how she had been obliged to send out to hire the necessary articles, subject to his nurse’s approval; and the captain’s sympathy having opened her heart, she further informed them of the inconvenient rout the said nurse had made about getting new milk for them, for which Honor could have found it in her heart to justify her; ‘and poor Owen is just as bad,’ quoth the old lady; ‘I declare those children are wearing his very life out, and yet he will not hear of leaving them behind.’

She was interrupted by his appearance at that moment, as usual, with a child in either hand, and a very sad picture it was, so mournful and spiritless was his countenance, with the hectic tint of decay evident on each thin cheek, and those two fair healthful creatures clinging to him, thoughtless of their past loss, unconscious of that which impended. Little Owen, after one good stare, evidently recognized a friend in Miss Charlecote, and let her seat him upon her knee, listening to her very complacently, but gazing very hard all the time at her, till at last, with an experimental air, he stretched one hand and stroked the broad golden ringlet that hung near him, evidently to satisfy himself whether it really was hair. Then he found his way to her watch, a pretty little one from Geneva, with enamelled flowers at the back, which so struck his fancy that he called out, ‘Cilly, look!’ The temptation drew the little girl nearer, but with her hands behind her back, as if bent on making no advance to the stranger.

Honora thought her the prettiest child she had ever seen. Small and lightly formed, there was more symmetry in her little fairy figure than usual at her age, and the skin was exquisitely fine and white, tinted with a soft eglantine pink, deepening into roses on the cheeks; the hair was in long flaxen curls, and the eyelashes, so long and fair that at times they caught a glossy light, shaded eyes of that deep blue upon that limpid white, which is like nothing but the clear tints of old porcelain. The features were as yet unformed, but small and delicate, and the upright Napoleon gesture had something peculiarly quaint and pretty in such a soft-looking little creature. The boy was a handsome fellow, with more solidity and sturdiness, and Honora could scarcely continue to amuse him, as she thought of the father’s pain in parting with two such beings—his sole objects of affection. A moment’s wish flashed across her, but was dismissed the next moment as a mere childish romance.

Old Mr. Sandbrook came in, and various other guests arrived, old acquaintance to whom Owen must be re-introduced, and he looked fagged and worn by the time all the greetings had been exchanged and all the remarks made on his children. When dinner was announced, he remained to the last with them, and p. 23did not appear in the dining-room till his uncle had had time to look round for him, and mutter something discontentedly about ‘those brats.’ The vacant chair was beside Honora, and he was soon seated in it, but at first he did not seem inclined to talk, and leant back, so white and exhausted, that she thought it kinder to leave him to himself.

When, somewhat recruited, he said in a low voice something of his hopes that his little Cilly, as he called her, would be less shy another time, and Honora responding heartily, he quickly fell into the parental strain of anecdotes of the children’s sayings and doings, whence Honora collected that in his estimation Lucilla’s forte was decision and Owen’s was sweetness, and that he was completely devoted to them, nursing and teaching them himself, and finding his whole solace in them. Tender pity moved her strongly towards him, as she listened to the evidences of the desolateness of his home and his heavy sorrow; and yet it was pity alone, admiration would not revive, and indeed, in spite of herself, her judgment would now and then respond ‘unwise,’ or ‘weak,’ or ‘why permit this?’ at details of Lucilla’s mutinerie. Presently she found that his intentions were quite at variance with those of his brother. His purpose was fixed to take the children with him.

‘They are very young,’ said Honora.

‘Yes; but their nurse is a most valuable person, and can arrange perfectly for them, and they will always be under my eye.’

‘That was just what Captain Charteris seemed to dread.’

‘He little knows,’ began Mr. Sandbrook, with a sigh. ‘Yes, I know he is most averse to it, and he is one who always carries his point, but he will not do so here; he imagines that they may go to their aunt’s nursery, but,’ with an added air of confidence, ‘that will never do!’

Honora’s eyes asked more.

‘In fact,’ he said, as the flush of pain rose on his cheeks, ‘the Charteris children are not brought up as I should wish to see mine. There are influences at work there not suited for those whose home must be a country parsonage, if— Little Cilly has come in for more admiration there already than is good for her.’

‘It cannot be easy for her not to meet with that.’

‘Why, no,’ said the gratified father, smiling sadly; ‘but Castle Blanch training might make the mischief more serious. It is a gay household, and I cannot believe with Kit Charteris that the children are too young to feel the blight of worldly influence. Do not you think with me, Nora?’ he concluded in so exactly the old words and manner as to stir the very depths of her heart, but woe worth the change from the hopes of youth to this premature fading into despondency, and the implied farewell! She did think with him completely, and felt the more for him, as she believed that these Charterises had led him and his wife into the gaieties, which since her death he had forsworn and abhorred as temptations. She thought it hard p. 24that he should not have his children with him, and talked of all the various facilities for taking them that she could think of, till his face brightened under the grateful sense of sympathy.

She did not hold the same opinion all the evening. The two children made their appearance at dessert, and there began by insisting on both sitting on his knees; Owen consented to come to her, but Lucilla would not stir, though she put on some pretty little coquettish airs, and made herself extremely amiable to the gentleman who sat on her father’s other hand, making smart replies, that were repeated round the table with much amusement.

But the ordinance of departure with the ladies was one of which the sprite had no idea; Honor held out her hand for her; Aunt Sandbrook called her; her father put her down; she shook her curls, and said she should not leave father; it was stupid up in the drawing-room, and she hated ladies, which confession set every one laughing, so as quite to annihilate the effect of Mr. Sandbrook’s ‘Yes, go, my dear.’

Finally, he took the two up-stairs himself—the stairs which, as he had told Honora that evening, were his greatest enemies, and he remained a long time in their nursery, not coming down till tea was in progress. Mrs. Sandbrook always made it herself at the great silver urn, which had been a testimonial to her husband, and it was not at first that she had a cup ready for him. He looked even worse than at dinner, and Honora was anxious to see him resting comfortably; but he had hardly sat down on the sofa, and taken the cup in his hand, before a dismal childish wail was heard from above, and at once he started up, so hastily as to cough violently. Captain Charteris, breaking off a conversation, came rapidly across the room just as he was moving to the door. ‘You’re not going to those imps—’

Owen moved his head, and stepped forward.

‘I’ll settle them.’

Renewed cries met his ears. ‘No—a strange place—’ he said. ‘I must—’

He put his brother-in-law back with his hand, and was gone. The captain could not contain his vexation, ‘That’s the way those brats serve him every night!’ he exclaimed; ‘they will not attempt to go to sleep without him! Why, I’ve found him writing his sermon with the boy wrapped up in blankets in his lap; there’s no sense in it.’

After about ten minutes, during which Mr. Sandbrook did not reappear, Captain Charteris muttered something about going to see about him, and stayed away a good while. When he came down, he came and sat down by Honora, and said, ‘He is going to bed, quite done for.’

‘That must be better for him than talking here.’

‘Why, what do you think I found? Those intolerable brats would not stop crying unless he told them a story, and there was he with his voice quite gone, coughing every two minutes, p. 25and romancing on with some allegory about children marching on their little paths, and playing on their little fiddles. So I told Miss Cilly that if she cared a farthing for her father, she would hold her tongue, and I packed her up, and put her into her nursery. She’ll mind me when she sees I will be minded; and as for little Owen, nothing would satisfy him but his promising not to go away. I saw that chap asleep before I came down, so there’s no fear of the yarn beginning again; but you see what chance there is of his mending while those children are at him day and night.’

‘Poor things! they little know.’

‘One does not expect them to know, but one does expect them to show a little rationality. It puts one out of all patience to see him so weak. If he is encouraged to take them abroad, he may do so, but I wash my hands of him. I won’t be responsible for him—let them go alone!’

Honora saw this was a reproach to her for the favour with which she had regarded the project. She saw that the father’s weakness quite altered the case, and her former vision flashed across her again, but she resolutely put it aside for consideration, and only made the unmeaning answer, ‘It is very sad and perplexing.’

‘A perplexity of his own making. As for their not going to Castle Blanch, they were always there in my poor sister’s time a great deal more than was good for any of them, or his parish either, as I told him then; and now, if he finds out that it is a worldly household, as he calls it, why, what harm is that to do to a couple of babies like those? If Mrs. Charteris does not trouble herself much about the children, there are governesses and nurses enough for a score!’

‘I must own,’ said Honora, ‘that I think he is right. Children are never too young for impressions.’

‘I’ll tell you what, Miss Charlecote, the way he is going on is enough to ruin the best children in the world. That little Cilly is the most arrant little flirt I ever came across; it is like a comedy to see the absurd little puss going on with the curate, ay, and with every parson that comes to Wrapworth; and she sees nothing else. Impressions! All she wants is to be safe shut up with a good governess, and other children. It would do her a dozen times more good than all his stories of good children and their rocky paths, and boats that never sailed on any reasonable principle.’

‘Poor child,’ said Honora, smiling, ‘she is a little witch.’

‘And,’ continued the uncle, ‘if he thinks it so bad for them, he had better take the only way of saving them from it for the future, or they will be there for life. If he gets through this winter, it will only be by the utmost care.’

Honora kept her project back with the less difficulty, because she doubted how it would be received by the rough captain; but it won more and more upon her, as she rattled home through p. 26the gas-lights, and though she knew she should learn to love the children only to have the pang of losing them, she gladly cast this foreboding aside as selfish, and applied herself impartially as she hoped to weigh the duty, but trembling were the hands that adjusted the balance. Alone as she stood, without a tie, was not she marked out to take such an office of mere pity and charity? Could she see the friend of her childhood forced either to peril his life by his care of his motherless children, or else to leave them to the influences he so justly dreaded? Did not the case cry out to her to follow the promptings of her heart? Ay, but might not, said caution, her assumption of the charge lead their father to look on her as willing to become their mother? Oh, fie on such selfish prudery imputing such a thought to yonder broken-hearted, sinking widower! He had as little room for such folly as she had inclination to find herself on the old terms. The hero of her imagination he could never be again, but it would be weak consciousness to scruple at offering so obvious an act of compassion. She would not trust herself, she would go by what Miss Wells said. Nevertheless she composed her letter to Owen Sandbrook between waking and sleeping all night, and dreamed of little creatures nestling in her lap, and small hands playing with her hair. How coolly she strove to speak as she described the dilemma to the old lady, and how her heart leapt when Miss Wells, her mind moving in the grooves traced out by sympathy with her pupil, exclaimed, ‘Poor little dears, what a pity they should not be with you, my dear, they would be a nice interest for you!’

Perhaps Miss Wells thought chiefly of the brightening in her child’s manner, and the alert vivacity of eye and voice such as she had not seen in her since she had lost her mother; but be that as it might, her words were the very sanction so much longed for, and ere long Honora had her writing-case before her, cogitating over the opening address, as if her whole meaning were implied in them.

‘My dear Owen’ came so naturally that it was too like an attempt to recur to the old familiarity. ‘My dear Mr. Sandbrook?’ So formal as to be conscious! ‘Dear Owen?’ Yes that was the cousinly medium, and in diffident phrases of restrained eagerness, now seeming too affectionate, now too cold she offered to devote herself to his little ones, to take a house on the coast, and endeavour to follow out his wishes with regard to them, her good old friend supplying her lack of experience.

With a beating heart she awaited the reply. It was but few lines, but all Owen was in them.

‘My dear Nora—You always were an angel of goodness. I feel your kindness more than I can express. If my darlings were to be left at all, it should be with you, but I cannot contemplate it. Bless you for the thought!

‘Yours ever, O. Sandbrook.’

p. 27She heard no more for a week, during which a dread of pressing herself on him prevented her from calling on old Mrs. Sandbrook. At last, to her surprise, she received a visit from Captain Charteris, the person whom she looked on as least propitious, and most inclined to regard her as an enthusiastic silly young lady. He was very gruff, and gave a bad account of his patient. The little boy had been unwell, and the exertion of nursing him had been very injurious; the captain was very angry with illness, child, and father.

‘However,’ he said, ‘there’s one good thing, L. has forbidden the children’s perpetually hanging on him, sleeping in his room, and so forth. With the constitutions to which they have every right, poor things, he could not find a better way of giving them the seeds of consumption. That settles it. Poor fellow, he has not the heart to hinder their always pawing him, so there’s nothing for it but to separate them from him.’

‘And may I have them?’ asked Honor, too anxious to pick her words.

‘Why, I told him I would come and see whether you were in earnest in your kind offer. You would find them no sinecure.’

‘It would be a great happiness,’ said she, struggling with tears that might prevent the captain from depending on her good sense, and speaking calmly and sadly; ‘I have no other claims, nothing to tie me to any place. I am a good deal older than I look, and my friend, Miss Wells, has been a governess. She is really a very wise, judicious person, to whom he may quite trust. Owen and I were children together, and I know nothing that I should like better than to be useful to him.’

‘Humph!’ said the captain, more touched than he liked to betray; ‘well, it seems the only thing to which he can bear to turn!’

‘Oh!’ she said, breaking off, but emotion and earnestness looked glistening and trembling through every feature.

‘Very well,’ said Captain Charteris, ‘I’m glad, at least, that there is some one to have pity on the poor things! There’s my brother’s wife, she doesn’t say no, but she talks of convenience and spoilt children—Sandbrook was quite right after all; I would not tell him how she answered me! Spoilt children to be sure they are, poor things, but she might recollect they have no mother—such a fuss as she used to make with poor Lucilla too. Poor Lucilla, she would never have believed that “dear Caroline” would have no better welcome for her little ones! Spoilt indeed! A precious deal pleasanter children they are than any of the lot at Castle Blanch, and better brought up too.’

The good captain’s indignation had made away with his consistency, but Honora did not owe him a grudge for revealing that she was his pis aller, she was prone to respect a man who showed that he despised her, and she only cared to arrange the details. He was anxious to carry away his charge at once, since every day of this wear and tear of feeling was doing incalculable p. 28harm, and she undertook to receive the children and nurse at any time. She would write at once for a house at some warm watering-place, and take them there as soon as possible, and she offered to call that afternoon to settle all with Owen.

‘Why,’ said Captain Charteris, ‘I hardly know. One reason I came alone was, that I believe that little elf of a Cilly has some notion of what is plotting against her. You can’t speak a word but that child catches up, and she will not let her father out of her sight for a moment.’

‘Then what is to be done? I would propose his coming here; but the poor child would not let him go.’

‘That is the only chance. He has been forbidden the walking with them in his arms to put them to sleep, and we’ve got the boy into the nursery, and he’d better be out of the house than hear them roaring for him. So if you have no objection, and he is tolerable this evening, I would bring him as soon as they are gone to bed.’

Poor Owen was evidently falling under the management of stronger hands than his own, and it could only be hoped that it was not too late. His keeper brought him at a little after eight that evening. There was a look about him as if, after the last stroke that had befallen him, he could feel no more, the bitterness of death was past, his very hands looked woe-begone and astray, without the little fingers pressing them. He could not talk at first; he shook Honor’s hand as if he could not bear to be grateful to her, and only the hardest hearts could have endured to enter on the intended discussion. The captain was very gentle towards him, and talk was made on other topics but gradually something of the influence of the familiar scene where his brightest days had been passed, began to prevail. All was like old times—the quaint old silver kettle and lamp, the pattern of the china cups, the ruddy play of the fire on the polished panels of the room—and he began to revive and join the conversation. They spoke of Delaroche’s beautiful Madonnas, one of which was at the time to be seen at a print-shop—‘Yes,’ said Mr. Sandbrook, ‘and little Owen cried out as soon as he saw it, “That lady, the lady with the flowery watch.”’

Honora smiled. It was an allusion to the old jests upon her auburn locks, ‘a greater compliment to her than to Delaroche,’ she said; ‘I saw that he was extremely curious to ascertain what my carrots were made of.’

‘Do you know, Nora, I never saw more than one person with such hair as yours,’ said Owen, with more animation, ‘and oddly enough her name turned out to be Charlecote.’

‘Impossible! Humfrey and I are the only Charlecotes left that I know of! Where could it have been?’

‘It was at Toronto. I must confess that I was struck by the brilliant hair in chapel. Afterwards I met her once or twice. She was a Canadian born, and had just married a settler, whose name I can’t remember, but her maiden name p. 29had certainly been Charlecote; I remembered it because of the coincidence.’

‘Very curious; I did not know there had been any Charlecotes but ourselves.’

‘And Humfrey Charlecote has never married?’

‘Never.’