CERVANTES.

Title: Wit and Wisdom of Don Quixote

Author: Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

Release date: March 4, 2008 [eBook #24754]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Turgut Dincer, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Turgut Dincer,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

The most trivial act of the daily life of some men has a unique interest, independent of idle curiosity, which dissatisfies us with the meagre food of date, place, and pedigree. So in the "Cartas de Indias" was published, two years ago, in Spain, a facsimile letter from Cervantes when tax-gatherer to Philip II., informing him of the efforts he had made to collect the taxes in certain Andalusian villages.

It is difficult, from the slight social record that we have of Cervantes, to draw the line where imagination begins and facts end.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, the contemporary of Shakspeare, Galileo, Camoens, Rubens, Tasso, and Lope de Vega, was born obscurely and in poverty, but with good antecedents. His grandfather, Juan de Cervantes, was the corregidor, or mayor, of Ossuna, and our poet was the youngest son of Rodrigo and Leonora de Cortiños, of the Barajas family. On either side he belonged to illustrious houses. He speaks of his birthplace xxii as the "famous Henares,"—"Alcala de Henares," sometimes called Alcala de San Justo, from the saint San Justo having there suffered martyrdom under the traitor Daciamos. The town is beautifully situated on the borders of the Henares River, two thousand feet above the level of the sea.

He was born on Sunday, October 9, 1547, and was baptized in the church of Santa Maria la Mayor, receiving his name on the fête day of his patron Saint Miguel, which some biographers have confounded with that of his birthday.

We may be forgiven for a few words about Alcala de Henares, since, had it only produced so rare a man as was Cervantes, it would have had sufficient distinction; but it was a town of an eventful historical record. It was destroyed about the year 1000, and rebuilt and possessed by the Moors, was afterwards conquered by Bernardo, Archbishop of Toledo. Three hundred years later it was the favorite retreat of Ximenes, then Cardinal Archbishop of Toledo, who returned to it, after his splendid conquests, laden with gold and silver spoil taken from the mosques of Oran, and with a far richer treasure of precious Arabian manuscripts, intended for such a university as had long been his ambition to create, and the corner-stone of which he laid with his own hands in 1500. There was a very solemn ceremonial at the founding of this famous university, and a xxiii hiding away of coins and inscriptions under its massive walls, and a pious invocation to Heaven for a special blessing on the archbishop's design! At the end of eight years the extensive and splendid buildings were finished and the whole town improved. With the quickening of literary labor and the increase of opportunities of acquiring knowledge, the reputation of the university was of the highest.

The cardinal's comprehensive mind included in its professorships all that he considered useful in the arts. Emulation was encouraged, and every effort was made to draw talent from obscurity. To this enlightened ecclesiastic is the world indebted for the undertaking of the Polyglot Bible, which, in connection with other learned works, led the university to be spoken of as one of the greatest educational establishments in the world. From far and near were people drawn to it. King Ferdinand paid homage to his subject's noble testimonial of labor, by visiting the cardinal at Alcala de Henares, and acknowledging that his own reign had received both benefit and glory from it. The people of Alcala punningly said, the church of Toledo had never had a bishop of greater edification than Ximenes; and Erasmus, in a letter to his friend Vergara, perpetrates a Greek pun on the classic name of Alcala, intimating the highest opinion of the state of science there. The reclining statue of Ximenes, beautifully carved in alabaster, xxiv now ornaments his sepulchre in the College of St. Ildefonso.

Cervantes shared the honor of the birthplace with the Emperor Ferdinand; he of "blessed memory," who failed to obtain permission from the Pope for priests to marry, but who, in spite of turbulent times, maintained religious peace in Germany, and lived to see the closing of the Council of Trent, marking his reign as one of the most enlightened of the age.

Alcala also claims Antonio de Solis, the well-known historian, whose "Conquest of Mexico" has been translated into many languages, as well as Teodora de Beza, a zealous Calvinistic reformer and famous divine, a sharer of Calvin's labors in Switzerland and author of the celebrated manuscripts known as Beza's manuscripts.

Judging from the character of the town and the refining educational influence that so grand a university must have had over its inhabitants, we have a right to believe that Cervantes was early imbued with all that was noble and good, and it is difficult to understand why, with all the advantages which the College of St. Ildefonso opened to him, he should have been sent away from it to that of Salamanca. Even allowing that the supposition of early poverty was correct, it would have appeared an additional reason for his being educated in his native town, particularly as liberal founxxvdations were made for indigent students. The fact of his being sent to Salamanca would seem to disprove the supposition of pecuniary necessity. In its early days, the university of Salamanca was justly celebrated for its progress in astronomy and familiarity with Greek and Arabian writers; but, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it seems to have remained very stationary, little attention being paid to aught beside medicine and dogmatic theology.

After being two years at Salamanca he changed to Madrid, where he is supposed to have made great progress, under the care of Juan Lopez de Hoyos, a professor of belles lettres, who spoke of Cervantes as "our dear and beloved pupil." Hoyos was himself a poet, and occasionally published collections to which Cervantes contributed his pastoral "Filena," which was much admired at the time. He also wrote several ballads; but ballads generally belong to their own age, and those that remain to us of his have lost much of their poignancy. Two poems, written on the death of Isabella of Valois, wife of Philip II., specially pleased Hoyos, who at the time gave full credit to his promising pupil. That eighth wonder of the world, the Escurial, was in progress during Cervantes' time in Madrid; built as expiatory by the king, the husband of the same unfortunate Isabella. He was that subtle tyrant of Spain, who had the grace to say, on the destructionxxvi of the Invincible Armada, "I sent my fleet to combat with the English, not with the elements. God's will be done."

While he was yet a boy, bull-fights were introduced into Spain:—

The attention of the Cardinal Acquaviva was called to him through his composition of "Filena," and, in 1568 or 1569, he joined the household of the cardinal and accompanied him to Rome. It is sad to think that only a few meagre items are all that remain to tell us of his daily life at this important period of his life. By some of his biographers he is mentioned as being under the protection of the cardinal; by one as seeking to better his penniless condition; by another as having the place of valet de chambre; and still again, we find him mentioned as a chamberlain in the household. Monsignor Guilio Acquaviva, in 1568, went as ambassador to Spain to offer the king the condolences of the Pontiff on the death of Don Carlos. The cardinal was a man of high position, young, yet of great accomplishments, and with cultivated literary tastes. What then could have been more natural than that he should havexxvii found companionship in Cervantes, and have desired to attach him to himself as a friend or as a confidential secretary, to be always near him. It is more than probable that his impressions of Southern France, which he immortalized in his early pastoral romance of "Galatea" were imbibed while making the journey to Rome with the cardinal, in whose service he must have remained three years, as in October 7, 1571, we find him joining the united Venetian, Papal, and Spanish expedition commanded by Don John of Austria, against the Turks and the African corsairs.

In the naval engagement at Lepanto, Cervantes was badly wounded, and finally lost his left hand and part of the arm. For six months he was immured in the hospital at Messina. After his recovery, he joined the expedition to the Levant, commanded by Marco Antonio Colonna, Duke of Valiano. He joined at intervals various other expeditions, and not till after his prominence in the engagement at Tunis, did he, in 1575, start to return to Spain, the land of his heart, the theme of the poet, and the region supposed by the Moors to have dropped from heaven. Don John of Austria and Don Carlos of Arragon, Viceroy of Sicily, each bore the warmest testimony to the bravery and heroism of our poet, and each gave him strong letters of commendation to the king of Spain.

In company with his own brother Roderigo, and other xxviii wounded soldiers who were returning home, he started in the ship El Sol, which had the misfortune, September 26, 1575, to be captured by an Algerine squadron. Then it happened that the letters from the two kings, so highly prized and upon which he had built so many hopes, proved a great misfortune to him. The pirates cast lots for the captives. Cervantes fell to the share of the captain, Dali Mami by name, who, in consequence of finding these two letters, imagined he must be some Don of great importance and worth a heavy ransom. He was watched and guarded with great strictness, loaded with heavy fetters, and subjected to cruelties of every kind, till his captor, not finding him of so much account as he had supposed, and no money being offered for his ransom, the captain finally sold him for five hundred escudos to the Dey Azan.

Inasmuch as a change might lead to something better, Cervantes rejoiced. His gallant spirit, ever hopeful, looked for the open door in misfortune. But, alas! his increased sufferings with the Dey reached a climax almost beyond endurance. He made every struggle to escape; but even in the midst of all his own sufferings, he found ways of aiding his fellow-victims and inspiring them with the hopes denied to himself. Roderigo had escaped long before, and from that time was making constant exertion to raise the needful amount to redeem xxix Miguel from the Dey, but not till September, 1580, did he succeed in effecting his release; some biographers making it a still later date.

His father had long been dead, and his mother and sisters gathered what they could, but the combined family efforts were insufficient. There was a society of pious and generous monks, who made special exertions to assist in the liberation of Christian captives, and they finally made up the amount demanded by Azan for Cervantes' release.

Worn down in spirit, broken in health, crushed at heart, who may venture to speak of the effect upon him when he once more found himself at home and in the embraces of his family? He himself says: "What transport in life can equal that which a man feels on the restoration of his liberty?" There is probably no more thrilling or exact an account of the Algerine slavery than he has given in "Don Quixote." Whether his love for a military life still pursued him, whether he desired an opportunity for revenge upon his persecutors, or whether it was fatality,—maimed and ruined as he was he once more entered the army. We cannot analyze his motive. He makes his bachelor Sampson say, "The historian must pen things not as they ought to have been but as they really were, without adding to or diminishing aught from the truth." The lives of literary men are not always devoid of stirring incidents. xxx M. Viardot says of him: "Cervantes was an illustrious man before he became an illustrious author; the doer of great deeds before he produced an immortal book." Don Lope de Figueras then commanded a regiment of tried and veteran soldiers in the army of the Duke of Alva, in Portugal. His brother Roderigo was serving in it when he joined it; and as Figueras had known Cervantes in former campaigns, it is most probable he was in his regiment. Later on, we find Cervantes accompanying the Marquis de Santa Cruz on an expedition to the Azores, serving long and bravely under him. The conquest of the Azores is described as a fiercely won but brilliant victory over all the islands; and Cervantes immortalized the genius and gallantry of the admiral in a sonnet.

The spirit of adventure ran high among the Castilians, while the whole nation was at the same time in course of mental as well as moral development. We are obliged to acknowledge that Spain in many ways was far behind Italy, though hardly as some would have it, at the distance of half a century. We must remember that, in 1530, there were only two hundred printing-presses in the whole of Europe, and that when the first one was set up in London, the Westminster abbot exclaimed, "Brethren, this is a tremendous engine! We must control it, or it will conquer us." The first press in Spain was set up in Valencia, in 1474, and Clemencin xxxi says that more printing-presses in the infancy of the art were probably at work in Spain than there are at the present day.

A change seemed to have crept gradually over the whole national character of Spain after the brilliant and prosperous reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, commencing with the severity of the Inquisition and continuing under the tyranny of Philip II., predisposing the army to savage deeds, till even the women and children were infected and the literature of the period slightly tinged.

Cervantes is too often merged into Don Quixote as if he had no separate existence. He accomplished more for the improvement of Spanish literature with his well-timed satire than all the laws or sermons could effect. His remarkable mind seems to have escaped the influence of the times, unless we make an exception of his drama "Numancia," which, while it excites the imagination, fills us with horror at its details, and fails to touch our hearts, but is full of historical truths. Schlegel, however, reviews it with enthusiasm. He calls his "Life in Algiers" a comedy, but undoubtedly it is a true picture of his own captivity. We are touched and filled with gloom at its perusal, and only remember it as a tragedy. These two dramas were lost sight of till the end of the eighteenth century, and they are superior to later dramatic efforts. He was proud of his original xxxii conception of a tragedy composed of ideal and allegorical characters which he permitted to have part in the "Life in Algiers," as well as in "Numancia." Of the thirty plays spoken of as given to the stage but few now remain; but others may yet be found. The Spaniards say the faults of a great writer are not left in the ink-stand. Spain, in Cervantes' day, had passed the chivalric age, though many relics of it still remained in its legends, songs, and proverbs. Cervantes becomes his own critic in his "Supplement to a Journey to Parnassus," and speaking of his dramas, says: "I should declare them worthy the favor they have received were they not my own." Unfortunately, his comedy of "La Confusa" is among the lost ones. He alludes to it as a good one among the best.

We have known Cervantes as a student, a soldier, a captive, and an author, and now we have to imagine our maimed and bronzed soldier-poet, after his many fortunes of war, in the new character of a lover. In thought we trace his noble features, his intelligent look and expressive eye, combined with his dignified bearing and thoughtful manner, and in so tracing we find it congenial to imagine him as being well dressed and enveloped in the ample Spanish cloak thrown gracefully over his breast and left shoulder, concealing the poor mutilated arm, and at the same time making it all the more difficult to believe that the right one had ever xxxiii wielded a "Toledo blade" or sworn that very strongest vow of loyalty, "A fe de Rodrigo."1

We find him much interested in the quaint old-fashioned town of Esquivias, making many friends therein, and sometimes gossiping with the host of the fonda, so famed for the generous wines of Esquivias that it needed no "bush;" and while enjoying his cigarito and taking an occasional morsel from the dish of quisado before him, he is learning from the same gossiping host many items of interest about the very illustrious families of Esquivias,—for it was famed for its chivalrous prowess and its "claims of long descent." He had commenced his "Galatea," and in it he was painting living portraits, and with great delicacy he was, as the shepherd Elicio, portraying his passion for Catalina, the daughter of Fernando de Salazar ý Voxmediano and Catalina de Palacios, both of illustrious families. Her father was dead, and she had been educated by her uncle, Francisco de Salazar, who left her a legacy in his will.

The fair Catalina, like other Spanish señoritas, was under the espionage of a strict dueña, and his opportunities of seeing her were very limited. Sometimes we fancy him awaiting the passing of the hour of the siesta and knocking at the grating of the heavy door of the house of the Salazars, and in reply to the porter's question xxxiv of Quien es? answering, in his melodious tones, Gente de paz (literally, "a friend"),—a precaution which still continues in Spain. Meanwhile, his romance of "Galatea" and of his own life are both growing. The occasion inspires him. He is still in Esquivias, wandering through the olive groves and by the river side, sometimes resting, and drinking in the fragrance from an orange-tree while his untold wealth of brain was seeking for its exit. Sometimes he had Catalina for a companion, the dueña lingering slightly behind. Sometimes he saw her at the church like a fair saint, kneeling; but oftener he wandered alone with his now happy thoughts, scarce knowing that the night was closing about him, or scarce heeding the watchman who cried, "All hail, Mary, mother of Jesus! half past twelve o'clock and a cloudy morning!" and thus, to this day, are the Spaniards warned of the hour and the weather. His "Galatea" remains unfinished. He had not meant that all this song should be for the public ear. The end was for his love alone!

On the 12th of December, 1584, he was married to Catalina. Not many years ago, the marriage contract was found in the public registry of Esquivias. It contains an inventory of the marriage-dowry promised by the bride's mother, of "lands, furniture, utensils, and live-stock." Then follows the details, "several vineyards, amounting to twelve acres, beds, chairs, xxxv brooms, brushes, poultry, and sundry sacks of flour." It is spoken of as a very respectable dowry at a time when sacks of wheat were worth eight reals. Then follows, in the same document, his own settlement upon his wife, which is stated to be one hundred ducats. By the custom of the time that was one-tenth of his whole property, or to quote again, which "must have amounted to a thousand ducats, which at present would be equivalent to about four hundred and fifty pounds sterling." Gladly would we find some pleasant items of happy home life, though, for the next four years, he lived quietly at Esquivias, and cared for the vineyards like any landholder, till, perhaps, he tired and went on to Seville, where he took up some mercantile business, though never entirely giving up the pen; but from 1598 till 1605, there are no real traces of him, when it would appear that he had removed to Valladolid.

There is little doubt but that he suffered both in purse and feeling from want of appreciation; but the Spanish proverb says, "An author's work who looks to money is the coat of a tailor who works late on the vespers of Easter Sunday." He had too noble a mind to harbor so mean a sentiment as jealousy, and was far in advance of his age. His countrymen, with characteristic indolence, were ready to cry, manaña, manaña (to-morrow, to-morrow), and so it was left for later generations to honor his memory, for his power of invention and purity xxxvi of imagination can never be rivalled. While acting as clerk in Seville to Antonio de Guevara, the Commissary-General to the Indian and American dependencies, he must have been sadly disappointed, particularly as, during that time, he had been unjustly thrown into prison on the plea of not accounting for trust-money with satisfaction. Mr. Ticknor gives the following interesting account: "During his residence at Seville, Cervantes made an ineffectual application to the king for an appointment in America, setting forth by the exact documents a general account of his adventures, services, and sufferings while a soldier in the Levant, and of the miseries of his life while a slave in Algiers; but no other than a formal answer seems to have been returned to his application, and the whole affair leaves us to infer the severity of that distress which could induce him to seek relief in exile to a colony of which he has elsewhere spoken as the great resort for rogues." The appointment he desired was either corregidor (or mayor) of the city of Paz or the auditorship of New Grenada, the governorship of the province of Socunusco or that of the galleys of Carthagena. His removal to Valladolid seems to have been by command of the revenue authorities, where he still collected taxes for public and private persons. While collecting for the prior of the order of St. John, he was again ill-treated and thrown into prison.

xxxviiNot till he was fifty-eight years old did he give to the world his master-piece, and thus immortalizes La Mancha, in return for his inhospitable and cruel treatment. "Don Quixote" was licensed at Valladolid in 1604, and printed at Madrid in 1605. Its success was so great that, during his lifetime, thirty thousand volumes were printed, which in that day was little short of marvellous. Four editions were published the first year, two at Madrid, one at Valencia, and one at Lisbon. Byron says: "Cervantes laugh'd Spain's chivalry away!" So popular was it, that a spurious second part, under the fictitious authorship of Avellanada was published. Cervantes was furious, and called him a blockhead; but Germond de Lavigue, the distinguished Spanish scholar, rashly asserts that but for this Avellanada, he would never have finished "Don Quixote." Even before it was printed, jealousy evidently existed in the hearts of rival writers, for in one of Lope's letters he refers to it, and spitefully hints that no poet could be found to write commendatory verses on it.

He recognized the fact of universal selfishness when he makes Sancho Panza refuse to learn the Don's love-letter and say, "Write it, your worship, for it's sheer nonsense to trust anything to my memory."

Spain is so full of rich material for romance that from it his mature mind seemed to inaugurate a new xxxviii age in Spanish literature. After the gloomy intolerance of Philip II., the advent of Philip III. added much to the literary freedom of Spain, which still belonged to the "Age of Chivalry," and to this day the true Spaniard nourishes the lofty and romantic qualities which, combined with a tone of sentiment and gravity and nobility of conversation, embellishes the legitimate grandee. Sismondi de Sismondi says the style of "Don Quixote" is inimitable. Montesquieu says: "It is written to prove all others useless." To some it is an allegory, to some a tragedy, to some a parable, and to others a satire. As a satirist we think him unrivalled, and this spirit found a choice opportunity for vent when the troops of Don Carlos I. marched upon Rome, taking Pope Clement VII. prisoner, while at the same time the king was having prayers said in the churches of Madrid for the deliverance of the Pope, on the plea that "he was obliged to make war against the temporal sovereign of Rome, but not upon the spiritual head of the Church!" No wonder the king, after proving himself so good a Catholic, should end his days in a monastery, or that he should mortify himself by lying in a coffin, wrapped in a shroud, while funeral services were performed over him. What, again, could have appealed more to his sense of the ridiculous than the contest between the priests and the authorities over the funeral obsequies of Philip II., so intolerant a tyrant xxxix that he caused every Spaniard to breathe more freely as he ceased so to do. He used his people as

We can easily believe in the greater freedom during the reign of Philip III. "Viva el Rey."

The Count de Lemos was his near friend and protector when he brought out the second part of "Don Quixote," and ridiculed his rival imitator. He was a pioneer of so elevated a character as to preclude the possibility of followers. Every one is familiar with it as a story, and the mishaps of the gentle, noble-minded, kind-hearted old Don, as well as the delusions, simplicity, and selfishness of the devoted squire, will never lose their power to amuse. It may be extravagant, but it is not a burlesque. The strong character painting, the ideas, situations, and language, clothed in such simplicity that at times it becomes almost solemn, give it a grandeur that no other book, considered as a romance, possesses. The old anecdote of the king observing a student walking by the river side and bursting into involuntary fits of laughter over a book, exclaiming, "The man is either mad or reading 'Don Quixote,'" is well preserved. One peculiar feature of the book is that, even now, for some places, it would be a useful guide, many xl of the habits and customs of Spain three hundred years ago being still the same. What a volume of wit and wisdom is contained in the proverbs and aphorisms. One might quote from it indefinitely had he not told us that "without discretion there is no wit." His own motive in writing it we find in the last paragraph of the book, namely, "My sole object has been to expose to the contempt they deserved the extravagant and silly tricks of chivalry, which this my true and genuine 'Don Quixote' has nearly accomplished, their worldly credit being now actually tottering, and will doubtless soon sink, never to rise again."

Now, all languages have it. There are eight translations into English alone; but it is always impossible for the translator to render its true spirit or to give it full justice. With all its vivacity and drollery, its delicate satire and keen ridicule, it has a mournful tinge of melancholy running through, and here and there peeping out, only to have been gathered from such experience as his. He wrote with neither bitterness nor a diseased imagination, always realizing what is due to himself and with a full appreciation of and desire for fame. Many scenes of real suffering appear under a dramatic guise, and here and there creep out bits of personal history. His nature was chivalrous in the highest degree. His sorrows were greater than his joys. Born for the library, he prefers the camp, and xli abandons literature to fight the Turks. Does he not make the Don say, "Let none presume to tell me the pen is preferable to the sword." Again he says: "Allowing that the end of war is peace, and that in this it exceeds the end of learning, let us weigh the bodily labors the scholar undergoes against those the warrior suffers, and then see which are the greatest." Then he enumerates: "First, poverty; and having said he endures poverty, methinks nothing more need be urged to express his misery, for he that is poor enjoys no happiness, but labors under this poverty in all its guises, at one time in hunger, at another in cold, another in nakedness, and sometimes in all of them together." Later on he makes him say: "It gives me some concern to think that powder and lead may suddenly cut short my career of glory."

The world can only be grateful that "his career of glory" did not end in the military advancement he had the right to expect. Had he been a general, his Rozinante might still have been wandering without a name, and Sancho Panza have died a common laborer. Again he says: "Would to God I could find a place to serve as a private tomb for this wearisome burden of life which I bear so much against my inclination." Surviving almost unheard-of grievances only to emerge from them with greater power; depicting in his works true outlines of his own adventures, sometimes by a xlii proverb, often by a romance, he never loses one jot of his pride, giving golden advice to Sancho when a governor, and finishing with the expression, "So may'st thou escape the PITY of the world." In May, 1605, he was called upon as a witness in a case of a man who was mortally wounded and dragged at night into his apartment, which almost accidentally gives us his household, consisting of his wife; his natural daughter Isabel, twenty years of age, unmarried; his sister, a widow, above fifty years; her unmarried daughter, aged twenty-eight; his half-sister, a religieuse; and a maid-servant. His "Española Inglesa" appeared in 1611. His moral tales, the pioneers in Spanish literature, are a combination without special plan of serious and comic, romance and anecdote, evidently giving, under the guise of fiction, poetically colored bits of his own experience in Italy and Africa. In his story of "La Gitanilla" (the gipsy girl) may be found the argument of Weber's opera of "Preciosa." "Parnassus" was written two years before his death, after which he wrote eight comedies and a sequel to his twelve moral tales. In his story of "Rinconete ý Cortadilla" he evidently derives the names from rincon (a corner) and cortar (to cut). His last work was "Persiles and Sigismunda," the preface of which is a near presentiment of his closing labors. He says: "Farewell, gayety; farewell, humor; farewell, my pleasant friends. I must now die, and I desire xliii nothing more than to soon see you again happy in another world." His industry was wonderful. We can but have a grateful feeling towards the Count de Lemos for adding to his physical comfort for the last few years, and feel a regret that the Count, who had lingered in Naples, could not have arrived in time to see him once more when he so ardently desired it. In a dedication to the Count of his final romance, written only four days before his death, he very touchingly says: "I could have wished not to have been obliged to make so close a personal application of the old verses commencing 'With the foot already in the stirrup,' for with very little alteration I may truly say that with my foot in the stirrup, feeling this moment the pains of dissolution, I address this letter to you. Yesterday I received extreme unction. To-day I have resumed my pen. Time is short, my pains increase, my hopes diminish, yet I do wish my life might be prolonged till I could see you again in Spain." His wish was not to be gratified; the Count, unaware of the near danger of his friend, only returned to find himself overwhelmed with grief at his loss.

After sixty-nine years of varied fortunes and many struggles, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra breathed his last, unsoothed by the hands he had loved, for even this privilege seems to have been denied to him. At the near end of his life he had joined the kindly third order xliv of the Franciscan friars, and the brethren cared for him at the last. His remarkable clearness of intellect never failed him, and on April 23, 1616, the very day that Shakspeare died at Stratford, Cervantes died at Madrid. Unlike the great English contemporary, whose undisturbed bones have lain quietly under peril of his malediction, the bones of the great Spanish poet were irrevocably lost when the old Convent of the Trinity, in the Calle del Humilladero, was destroyed. Ungrateful Spain! the spot had never been marked with a common tombstone.

The old house2 in the Calle de Francos, where he died, was so dilapidated that, in 1835, it was destroyed. It was rebuilt, and a marble bust of Cervantes was placed over the entrance by the sculptor, Antonio Sola.

The "Madrid Epoca," under the heading of "The Prison of Cervantes," calls attention to the alarming state of decay of the house in Argamasilla del Alba, in the cellar of which, as an extemporized dungeon, tradition asserts that Cervantes was imprisoned, and where he penned at least a portion of his work. It was in this cellar that, a few years since, the Madrid publishing house of Rivadeneyra erected a press and xlv printed their edition de luxe of "Don Quijote." The house was, some years since, purchased by the late Infante Don Sebastian, with a view to a complete and careful restoration; but political changes and his death prevented a realization of his project. The "Epoca" now calls public attention to the state of decay of the house, with a view to an immediate restoration.

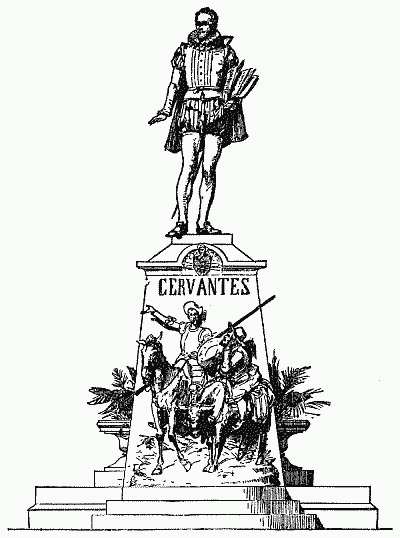

In the Plaza de las Cortes, the city of Madrid has placed a beautiful bronze statue of Cervantes upon a square pedestal of granite. Upon the sides are bas-reliefs representing subjects taken from "Don Quijote de la Mancha."

The present time honors his memory; and for all time he will live in the hearts of all true lovers of genius.

EMMA THOMPSON.

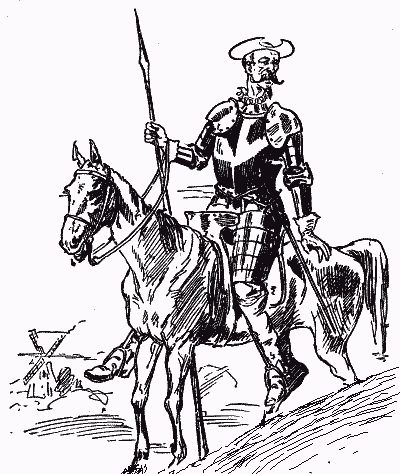

Down in a village of La Mancha, the name of which I have no desire to recollect, there lived, not long ago, one of those gentlemen who usually keep a lance upon a rack, an old buckler, a lean horse, and a coursing grayhound. Soup, composed of somewhat more mutton than beef, the fragments served up cold on most nights, lentils on Fridays, collops and eggs on Saturdays, and a pigeon by way of addition on Sundays, consumed three-fourths of his income; the remainder of it supplied him with a cloak of fine cloth, velvet breeches, with slippers of the same for holidays, and a suit of the best homespun, in which he adorned himself on week-days. His family consisted of a housekeeper above forty, a niece not quite twenty, and a lad who served him both in the field and at home, who could saddle the horse or handle the pruning-hook. The age of our gentleman bordered upon fifty years: he was of a strong constitution, spare-bodied, of a meagre visage, a very early riser, 2 and a lover of the chase. Some pretend to say that his surname was Quixada or Quesada, for on this point his historians differ; though, from very probable conjectures, we may conclude that his name was Quixana. This is, however, of little importance to our history; let it suffice that, in relating it, we do not swerve a jot from the truth.

In fine, his judgment being completely obscured, he was seized with one of the strangest fancies that ever entered the head of any madman; this was, a belief that it behooved him, as well for the advancement of his glory as the service of his country, to become a knight-errant, and traverse the world, armed and mounted, in quest of adventures, and to practice all that had been performed by knights-errant of whom he had read; redressing every species of grievance, and exposing himself to dangers, which, being surmounted, might secure to him eternal glory and renown. The poor gentleman imagined himself at least crowned Emperor of Trebisond, by the valor of his arm; and thus wrapped in these agreeable delusions and borne away by the extraordinary pleasure he found in them, he hastened to put his designs into execution.

The first thing he did was to scour up some rusty armor which had been his great-grandfather's, and had lain many years neglected in a corner. This he cleaned and adjusted as well as he could; but he found one grand defect,—the helmet was incomplete, having only the morion. This deficiency, however, he ingeniously supplied by making a kind of visor of 3 pasteboard, which, being fixed to the morion, gave the appearance of an entire helmet. It is true, indeed, that, in order to prove its strength, he drew his sword, and gave it two strokes, the first of which instantly demolished the labor of a week; but not altogether approving of the facility with which it was destroyed, and in order to secure himself against a similar misfortune, he made another visor, which, having fenced in the inside with small bars of iron, he felt assured of its strength, and, without making any more experiments, held it to be a most excellent helmet.

In the next place he visited his steed; and although this animal had more blemishes than the horse of Gonela, which, "tantum pellis et ossa fuit," yet, in his eyes, neither the Bucephalus of Alexander nor the Cid's Babieca, could be compared with him. Four days was he deliberating upon what name he should give him; for, as he said to himself, it would be very improper that a horse so excellent, appertaining to a knight so famous, should be without an appropriate name; he therefore endeavored to find one that should express what he had been before he belonged to a knight-errant, and also what he now was: nothing could, indeed, be more reasonable than that, when the master changed his state, the horse should likewise change his name and assume one pompous and high-sounding, as became the new order he now professed. So, after having devised, altered, lengthened, curtailed, rejected, and again framed in his imagination a variety of names, he finally determined upon Rozinante, a name in his opinion lofty, sonorous, and full of meaning; 4 importing that he had only been a rozin—a drudge horse—before his present condition, and that now he was before all the rozins in the world.

Having given his horse a name so much to his satisfaction, he resolved to fix upon one for himself. This consideration employed him eight more days, when at length he determined to call himself Don Quixote; whence some of the historians of this most true history have concluded that his name was certainly Quixada, and not Quesada, as others would have it. Then recollecting that the valorous Amadis, not content with the simple appellation of Amadis, added thereto the name of his kingdom and native country, in order to render it famous, styling himself Amadis de Gaul; so he, like a good knight, also added the name of his province, and called himself Don Quixote de la Mancha; whereby, in his opinion, he fully proclaimed his lineage and country, which, at the same time, he honored by taking its name.

His armor being now furbished, his helmet made perfect, his horse and himself provided with names, he found nothing wanting but a lady to be in love with, as he said,—

"A knight-errant without a mistress was a tree without either fruit or leaves, and a body without a soul!"

One morning before day, being one of the most sultry in the month of July, he armed himself cap-a-pie, mounted Rozinante, placed the helmet on his head, braced on his target, took his lance, and, through the private gate of his back yard, issued forth into the open 5 plain, in a transport of joy to think he had met with no obstacles to the commencement of his honorable enterprise. But scarce had he found himself on the plain when he was assailed by a recollection so terrible as almost to make him abandon the undertaking; for it just then occurred to him that he was not yet dubbed a knight; therefore, in conformity to the laws of chivalry, he neither could nor ought to enter the lists against any of that order; and, if he had been actually dubbed he should, as a new knight, have worn white armor, without any device on his shield, until he had gained one by force of arms. These considerations made him irresolute whether to proceed, but frenzy prevailing over reason, he determined to get himself made a knight by the first one he should meet, like many others of whom he had read. As to white armor, he resolved, when he had an opportunity, to scour his own, so that it should be whiter than ermine. Having now composed his mind, he proceeded, taking whatever road his horse pleased; for therein, he believed, consisted the true spirit of adventure. Everything that our adventurer saw and conceived was, by his imagination, moulded to what he had read; so in his eyes the inn appeared to be a castle, with its four turrets, and pinnacles of shining silver, together with its drawbridge, deep moat, and all the appurtenances with which such castles are visually described. When he had advanced within a short distance of it, he checked Rozinante, expecting some dwarf would mount the battlements, to announce by sound of trumpet the arrival of a knight-errant at the castle; but, finding them tardy, and Rozinante 6 impatient for the stable, he approached the inn-door, and there saw the two girls, who to him appeared to be beautiful damsels or lovely dames enjoying themselves before the gate of their castle.

It happened that, just at this time, a swineherd collecting his hogs (I make no apology, for so they are called) from an adjoining stubblefield, blew the horn which assembles them together, and instantly Don Quixote was satisfied, for he imagined it was a dwarf who had given the signal of his arrival. With extraordinary satisfaction, therefore, he went up to the inn; upon which the ladies, being startled at the sight of a man armed in that manner, with lance and buckler, were retreating into the house; but Don Quixote, perceiving their alarm, raised his pasteboard visor, thereby partly discovering his meagre, dusty visage, and with gentle demeanor and placid voice, thus addressed them: "Fly not, ladies, nor fear any discourtesy, for it would be wholly inconsistent with the order of knighthood, which I profess, to offer insult to any person, much less to virgins of that exalted rank which your appearance indicates." The girls stared at him, and were endeavoring to find out his face, which was almost concealed by the sorry visor; but hearing themselves called virgins, they could not forbear laughing, and to such a degree that Don Quixote was displeased, and said to them: "Modesty well becomes beauty, and excessive laughter proceeding from slight cause is folly."

This language, so unintelligible to the ladies, added to the uncouth figure of our knight, increased their laughter; consequently he grew more indignant, and 7 would have proceeded further but for the timely appearance of the innkeeper, a very corpulent and therefore a very pacific man, who, upon seeing so ludicrous an object, armed, and with accoutrements so ill-sorted as were the bridle, lance, buckler, and corselet, felt disposed to join the damsels in demonstrations of mirth; but, in truth, apprehending some danger from a form thus strongly fortified, he resolved to behave with civility, and therefore said, "If, Sir Knight, you are seeking for a lodging, you will here find, excepting a bed (for there are none in this inn), everything in abundance." Don Quixote, perceiving the humility of the governor of the fortress,—for such to him appeared the innkeeper,—answered, "For me, Signor Castellano, anything will suffice, since arms are my ornaments, warfare my repose." The host thought he called him Castellano because he took him for a sound Castilian, whereas he was an Andalusian of the coast of St. Lucar, as great a thief as Cacus and not less mischievous than a collegian or a page; and he replied, "If so, your worship's beds must be hard rocks, and your sleep continual watching; and that being the case, you may dismount with a certainty of finding here sufficient cause for keeping awake the whole year, much more a single night." So saying, he laid hold of Don Quixote's stirrup, who alighted with much difficulty and pain, for he had fasted the whole of the day. He then desired the host to take especial care of his steed, for it was the finest creature ever fed; the innkeeper examined him, but thought him not so good by half as his master had represented him. Having led the horse to 8 the stable he returned to receive the orders of his guest, whom the damsels, being now reconciled to him, were disarming; they had taken off the back and breast plates, but endeavored in vain to disengage the gorget, or take off the counterfeit beaver, which he had fastened with green ribbons in such a manner that they could not be untied, and he would upon no account allow them to be cut; therefore he remained all that night with his helmet on, the strangest and most ridiculous figure imaginable.

While these light girls, whom he still conceived to be persons of quality and ladies of the castle, were disarming him, he said to them, with infinite grace: "Never before was knight so honored by ladies as Don Quixote, after his departure from his native village! damsels attended upon him; princesses took charge of his steed! O Rosinante,—for that, ladies, is the name of my horse, and Don Quixote de la Mancha my own; although it was not my intention to have discovered myself until deeds performed in your service should have proclaimed me; but impelled to make so just an application of that ancient romance of Lanzarote to my present situation, I have thus prematurely disclosed my name: yet the time shall come when your ladyships may command, and I obey; when the valor of my arm shall make manifest the desire I have to serve you." The girls, unaccustomed to such rhetorical flourishes, made no reply, but asked whether he would please to eat anything. "I shall willingly take some food," answered Don Quixote, "for I apprehend it would be of much service to me." That day happened to be 9 Friday, and there was nothing in the house but some fish of that kind which in Castile is called Abadexo; in Andalusia, Bacallao; in some parts, Curadillo: and in others, Truchuela. They asked if his worship would like some truchuela, for they had no other fish to offer him. "If there be many troutlings," replied Don Quixote, "they will supply the place of one trout; for it is the same to me whether I receive eight single rials or one piece-of-eight. Moreover, these troutlings may be preferable, as veal is better than beef, and kid superior to goat. Be that as it may, let it come immediately, for the toil and weight of arms cannot be sustained by the body unless the interior be supplied with aliments." For the benefit of the cool air, they placed the table at the door of the inn, and the landlord produced some of his ill-soaked and worse-cooked bacallao, with bread as foul and black as the knight's armor. But it was a spectacle highly risible to see him eat; for his hands being engaged in holding his helmet on and raising the beaver, he could not feed himself, therefore one of the ladies performed that office for him; but to drink would have been utterly impossible had not the innkeeper bored a reed, and placing one end into his mouth at the other poured in the wine; and all this he patiently endured rather than cut the lacings of his helmet.

It troubled him to reflect that he was not yet a knight, feeling persuaded that he could not lawfully engage in 10 any adventure until he had been invested with the order of knighthood.

Agitated by this idea, he abruptly finished his scanty supper, called the innkeeper, and, shutting himself up with him in the stable, he fell on his knees before him and said, "Never will I arise from this place, valorous knight, until your courtesy shall vouchsafe to grant a boon which it is my intention to request,—a boon that will redound to your glory and to the benefit of all mankind." The innkeeper, seeing his guest at his feet and hearing such language, stood confounded and stared at him without knowing what to do or say; he entreated him to rise, but in vain, until he had promised to grant the boon he requested. "I expected no less, signor, from your great magnificence," replied Don Quixote; "know, therefore, that the boon I have demanded, and which your liberality has conceded, is that on the morrow you will confer upon me the honor of knighthood. This night I will watch my arms in the chapel of your castle, in order that, in the morning, my earnest desire may be fulfilled and I may with propriety traverse the four quarters of the world in quest of adventures for the relief of the distressed, conformable to the duties of chivalry and of knights-errant, who, like myself, are devoted to such pursuits."

The host, who, as we have said, was a shrewd fellow, and had already entertained some doubts respecting the wits of his guest, was now confirmed in his suspicions; and to make sport for the night, determined to follow his humor. He told him, therefore, that his desire was very reasonable, and that such pursuits were natural 11 and suitable to knights so illustrious as he appeared to be, and as his gallant demeanor fully testified; that he had himself in the days of his youth followed that honorable profession, and travelled over various parts of the world in search of adventures; failing not to visit the suburbs of Malaga, the isles of Riaran, the compass of Seville, the market-place of Segovia, the olive-field of Valencia, the rondilla of Grenada, the coast of St. Lucar, the fountain of Cordova, the taverns of Toledo, and divers other parts, where he had exercised the agility of his heels and the dexterity of his hands; committing sundry wrongs, soliciting widows, seducing damsels, cheating youths,—in short, making himself known to most of the tribunals in Spain; and that, finally, he had retired to this castle, where he lived upon his revenue and that of others, entertaining therein all knights-errant of every quality and degree solely for the great affection he bore them, and that they might share their fortune with him in return for his good will. He further told him that in his castle there was no chapel wherein he could watch his armor, for it had been pulled down in order to be rebuilt; but that, in cases of necessity, he knew it might be done wherever he pleased. Therefore, he might watch it that night in a court of the castle, and the following morning, if it pleased God, the requisite ceremonies should be performed, and he should be dubbed so effectually that the world would not be able to produce a more perfect knight. He then inquired if he had any money about him. Don Quixote told him he had none, having never read in their histories that knights-errant provided 12 themselves with money. The innkeeper assured him he was mistaken; for, admitting that it was not mentioned in their history, the authors deeming it unnecessary to specify things so obviously requisite as money and clean shirts, yet was it not therefore to be inferred that they had none; but, on the contrary, he might consider it as an established fact that all knights-errant, of whose histories so many volumes are filled, carried their purses well provided against accidents; that they were also supplied with shirts, and a small casket of ointments to heal the wounds they might receive, for in plains and deserts, where they fought and were wounded, no aid was near unless they had some sage enchanter for their friend, who could give them immediate assistance by conveying in cloud through the air some damsel or dwarf, with a phial of water possessed of such virtue that, upon tasting a single drop of it, they should instantly become as sound as if they had received no injury. But when the knights of former times were without such a friend, they always took care that their esquires should be provided with money and such necessary articles as lint and salves; and when they had no esquires—which very rarely happened—they carried these things themselves upon the crupper of their horse, in wallets so small as to be scarcely visible, that they might seem to be something of more importance; for, except in such cases, the custom of carrying wallets was not tolerated among knights-errant. He therefore advised, though, as his godson (which he was soon to be), he might command him, never henceforth to travel without money and the 13 aforesaid provisions, and he would find them serviceable when he least expected it. Don Quixote promised to follow his advice with punctuality: and an order was now given for performing the watch of the armor in a large yard adjoining the inn. Don Quixote, having collected it together placed it on a cistern which was close to a well; then, bracing on his target and grasping his lance, with graceful demeanor he paced to and fro before the pile, beginning his parade as soon as it was dark.

The innkeeper informed all who were in the inn of the frenzy of his guest, the watching of his armor, and of the intended knighting.

The host repeated to him that there was no chapel in the castle, nor was it by any means necessary for what remained to be done; that the stroke of knighting consisted in blows on the neck and shoulders, according to the ceremonial of the order, which might be effectually performed in the middle of the field; that the duty of watching his armor he had now completely fulfilled, for he had watched more than four hours, though only two were required. All this Don Quixote believed, and said that he was there ready to obey him, requesting him, at the same time, to perform the deed as soon as possible; because, should he be assaulted again when he found himself knighted, he was resolved not to leave one person alive in the castle, excepting those whom, out of respect to him, and at his particular request, he might be induced to spare. The constable, thus warned and alarmed, immediately brought forth a book in which he kept his account of the straw and 14 oats he furnished to the carriers, and attended by a boy, who carried an end of candle, and the two damsels before mentioned, went towards Don Quixote, whom he commanded to kneel down; he then began reading in his manual, as if it were some devout prayer, in the course of which he raised his hand and gave him a good blow on the neck, and, after that, a handsome stroke over the shoulders, with his own sword, still muttering between his teeth, as if in prayer. This being done, he commanded one of the ladies to gird on his sword, an office she performed with much alacrity, as well as discretion, no small portion of which was necessary to avoid bursting with laughter at every part of the ceremony; but indeed the prowess they had seen displayed by the new knight kept their mirth within bounds.

At girding on the sword, the good lady said: "God grant you may be a fortunate knight and successful in battle."

Don Quixote inquired her name, that he might thenceforward know to whom he was indebted for the favor received, as it was his intention to bestow upon her some share of the honor he should acquire by the valor of his arm. She replied, with much humility, that her name was Tolosa, and that she was the daughter of a cobbler at Toledo, who lived at the stalls of Sanchobienaya; and that, wherever she was, she would serve and honor him as her lord. Don Quixote, in reply, requested her, for his sake, to do him the favor henceforth to add to her name the title of don, and call herself Donna Tolosa, which she promised to do. 15 The other girl now buckled on his spur, and with her he held nearly the same conference as with the lady of the sword; having inquired her name, she told him it was Molinera, and that she was daughter to an honest miller of Antiquera: he then requested her likewise to assume the don, and style herself Donna Molinera, renewing his proffers of service and thanks.

These never-till-then-seen ceremonies being thus speedily performed, Don Quixote was impatient to find himself on horseback, in quest of adventures. He therefore instantly saddled Rozinante, mounted him, and, embracing his host, made his acknowledgments for the favor he had conferred by knighting him, in terms so extraordinary, that it would be in vain to attempt to repeat them. The host, in order to get rid of him the sooner, replied, with no less flourish, but more brevity; and, without making any demand for his lodging, wished him a good journey.

The tongue slow and the eyes quick.

Keep your mouth shut and your eyes open.

The brave man carves out his own fortune.

Very full of pain, yet soon as he was able to stir, he began to roll himself on the ground, and to repeat, in what they affirm was said by the wounded knight of the wood:—

16 "I know who I am," answered Don Quixote; "and I know, too, that I am not only capable of being those I have mentioned, but all the twelve peers of France, yea, and the nine worthies, since my exploits will far exceed all that they have jointly or separately achieved."

Long and heavy was the sleep of Don Quixote: meanwhile the priest having asked the niece for the key of the chamber containing the books, those authors of the mischief, which she delivered with a very good will, they entered, attended by the housekeeper, and found above a hundred large volumes well bound, besides a great number of smaller size. No sooner did the housekeeper see them than she ran out of the room in great haste, and immediately returned with a pot of holy water and a bunch of hyssop, saying: "Signor Licentiate, take this and sprinkle the room, lest some enchanter of the many that these books abound with should enchant us, as a punishment for our intention to banish them out of the world."

The priest smiled at the housekeeper's simplicity, and ordered the barber to reach him the books one by one, that they might see what they treated of, as they might perhaps find some that deserved not to be chastised by fire.

"No," said the niece, "there is no reason why any of them should be spared, for they have all been mischief-makers: so let them all be thrown out of the window into the courtyard; and having made a pile of 17 them, set fire to it; or else make a bonfire of them in the back yard, where the smoke will offend nobody."

The housekeeper said the same, so eagerly did they both thirst for the death of those innocents. But the priest would not consent to it without first reading the titles at least.

The first that Master Nicholas put into his hands was "Amadis de Gaul," in four parts; and the priest said: "There seems to be some mystery in this, for I have heard say that this was the first book of chivalry printed in Spain, and that all the rest had their foundation and rise from it; I think, therefore, as head of so pernicious a sect, we ought to condemn him to the fire without mercy."

"Not so," said the barber; "for I have heard also that it is the best of all the books of this kind: therefore, as being unequalled in its way, it ought to be spared."

"You are right," said the priest, "and for that reason its life is granted for the present. Let us see that other next to him."

"It is," said the barber, "the 'Adventures of Esplandian,' the legitimate son of 'Amadis de Gaul.'"

"Verily," said the priest, "the goodness of the father shall avail the son nothing; take him, Mistress Housekeeper; open that casement, and throw him into the yard, and let him make a beginning to the pile for the intended bonfire."

The housekeeper did so with much satisfaction, and good Esplandian was sent flying into the yard, there to wait with patience for the fire with which he was threatened.

18 "Proceed," said the priest.

"The next," said the barber, "is 'Amadis of Greece;' yea, and all these on this side, I believe, are of the lineage of Amadis."

"Then into the yard with them all!" quoth the priest; "for rather than not burn Queen Pintiquiniestra, and the shepherd Darinel with his eclogues, and the devilish perplexities of the author, I would burn the father who begot me, were I to meet him in the shape of a knight-errant."

"Of the same opinion am I," said the barber.

"And I too," added the niece.

"Well, then," said the housekeeper, "away with them all into the yard." They handed them to her; and, as they were numerous, to save herself the trouble of the stairs, she threw them all out of the window.

"What tun of an author is that?" said the priest.

"This," answered the barber, "is 'Don Olivante de Laura.'"

"The author of that book," said the priest, "was the same who composed the 'Garden of Flowers;' and in good truth I know not which of the two books is the truest, or rather, the least lying: I can only say that this goes to the yard for its arrogance and absurdity."

"This that follows is 'Florismarte of Hyrcania,'" said the barber.

"What! is Signor Florismarte there?" replied the priest; "now, by my faith, he shall soon make his appearance in the yard, notwithstanding his strange birth and chimerical adventures; for the harshness 19 and dryness of his style will admit of no excuse. To the yard with him, and this other, Mistress Housekeeper.

"With all my heart, dear sir," answered she, and with much joy executed what she was commanded.

"Here is the 'Knight Platir,'" said the barber.

"That," said the priest, "is an ancient book, and I find nothing in him deserving pardon: without more words, let him be sent after the rest;" which was accordingly done. They opened another book, and found it entitled the "Knight of the Cross." "So religious a title," quoth the priest, "might, one would think, atone for the ignorance of the author; but it is a common saying 'the devil lurks behind the cross:' so to the fire with him."

The barber, taking down another book, said, "This is 'The Mirror of Chivalry.'"

"Oh! I know his worship very well," quoth the priest. "I am only for condemning this to perpetual banishment because it contains some things of the famous Mateo Boyardo.

"If I find him here uttering any other language than his own, I will show no respect; but if he speaks in his own tongue, I will put him upon my head."

"I have him in Italian," said the barber, "but I do not understand him."

"Neither is it any great matter, whether you understand him or not," answered the priest; "and we would willingly have excused the good captain from bringing him into Spain and making him a Castilian; for he has deprived him of a great deal of his native value; which, 20 indeed, is the misfortune of all those who undertake the translation of poetry into other languages; for, with all their care and skill, they can never bring them on a level with the original production. This book, neighbor, is estimable upon two accounts; the one, that it is very good of itself; and the other, because there is a tradition that it was written by an ingenious king of Portugal. All the adventures of the castle of Miraguarda are excellent, and contrived with much art; the dialogue courtly and clear; and all the characters preserved with great judgment and propriety. Therefore, Master Nicholas, saving your better judgment, let this and 'Amadis de Gaul' be exempted from the fire, and let all the rest perish without any further inquiry."

"Not so, friend," replied the barber; "for this which I have here is the renowned 'Don Bellianis.'"

The priest replied: "This, and the second, third, and fourth parts, want a little rhubarb to purge away their excess of bile; besides, we must remove all that relates to the castle of Fame, and other absurdities of greater consequence; for which let sentence of transportation be passed upon them, and, according as they show signs of amendment, they shall be treated with mercy or justice. In the mean time, neighbor, give them room in your house; but let them not be read."

"With all my heart," quoth the barber; and without tiring himself any farther in turning over books of chivalry, bid the housekeeper take all the great ones and throw them into the yard. This was not spoken to the stupid or deaf, but to one who had a greater mind to be burning them than weaving the finest and largest web; 21 and therefore, laying hold of seven or eight at once, she tossed them out at the window.

But, in taking so many together, one fell at the barber's feet, who had a mind to see what it was, and found it to be the history of the renowned knight Tirante the White. "Heaven save me!" quoth the priest, with a loud voice, "is Tirante the White there? Give him to me, neighbor; for in him I shall have a treasure of delight, and a mine of entertainment. Here we have Don Kyrie-Eleison of Montalvan, a valorous knight, and his brother Thomas of Montalvan, with the knight Fonseca, and the combat which the valiant Tirante fought with the bull-dog, and the witticisms of the damsel Plazerdemivida; also the amours and artifices of the widow Reposada; and madam the Empress in love with her squire Hypolito. Verily, neighbor, in its way it is the best book in the world: here the knights eat and sleep, and die in their beds, and make their wills before their deaths; with several things which are not to be found in any other books of this kind. Notwithstanding this I tell you, the author deserved, for writing so many foolish things seriously, to be sent to the galleys for the whole of his life: carry it home, and read it, and you will find all I say of him to be true."

"I will do so," answered the barber: "but what shall we do with these small volumes that remain?"

"Those," said the priest, "are, probably, not books of chivalry, but of poetry." Then opening one he found it was the 'Diana' of George de Montemayor, and, concluding that all the others were of the same kind, he said, "These do not deserve to be burnt like the rest; 22 for they cannot do the mischief that those of chivalry have done; they are works of genius and fancy, and do injury to none."

"O sir," said the niece, "pray order them to be burnt with the rest; for should my uncle be cured of this distemper of chivalry, he may possibly, by reading such books, take it into his head to turn shepherd, and wander through the woods and fields, singing and playing on a pipe; and what would be still worse, turn poet, which, they say, is an incurable and contagious disease."

"The damsel says true," quoth the priest, "and it will not be amiss to remove this stumbling-block out of our friend's way. And, since we begin with the 'Diana' of Montemayor, my opinion is that it should not be burnt, but that all that part should be expunged which treats of the sage Felicia, and of the enchanted fountain, and also most of the longer poems; leaving him, in God's name, the prose and also the honor of being the first in that kind of writing."

"The next that appears," said the barber, "is the Diana, called the second, by Salmantino; and another, of the same name, whose author is Gil Polo."

"The Salmantinian," answered the priest, "may accompany and increase the number of the condemned—to the yard with him: but let that of Gil Polo be preserved, as if it were written by Apollo himself. Proceed, friend, and let us despatch; for it grows late."

"This," said the barber, opening another, "is the 'Ten Books of the Fortune of Love,' composed by Antonio de lo Frasso, a Sardinian poet."

23 "By the holy orders I have received!" said the priest, "since Apollo was Apollo, the muses muses, and the poets poets, so humorous and so whimsical a book as this was never written; it is the best, and most extraordinary of the kind that ever appeared in the world; and he who has not read it may be assured that he has never read anything of taste: give it me here, neighbor, for I am better pleased at finding it than if I had been presented with a cassock of Florence satin." He laid it aside, with great satisfaction, and the barber proceeded, saying:—

"These which follow are the 'Shepherd of Iberia,' the 'Nymphs of Enares,' and the 'Cure of Jealousy.'"

"Then you have only to deliver them up to the secular arm of the housekeeper," said the priest, "and ask me not why, for in that case we should never have done."

"The next is the 'Shepherd of Filida.'"

"He is no shepherd," said the priest, "but an ingenious courtier; let him be preserved, and laid up as a precious jewel."

"This bulky volume here," said the barber, "is entitled the 'Treasure of Divers Poems.'"

"Had they been fewer," replied the priest, "they would have been more esteemed: it is necessary that this book should be weeded and cleared of some low things interspersed amongst its sublimities: let it be preserved, both because the author is my friend, and out of respect to other more heroic and exalted productions of his pen."

"This," pursued the barber, "is 'El Cancionero' of Lopez Maldonado."

24 "The author of that book," replied the priest, "is also a great friend of mine: his verses, when sung by himself, excite much admiration; indeed such is the sweetness of his voice in singing them, that they are perfectly enchanting. He is a little too prolix in his eclogues; but there can never be too much of what is really good: let it be preserved with the select. But what book is that next to it?"

"The 'Galatea' of Miguel de Cervantes," said the barber.

"That Cervantes has been an intimate friend of mine these many years, and I know that he is more versed in misfortunes than in poetry. There is a good vein of invention in his book, which proposes something, though nothing is concluded. We must wait for the second part, which he has promised: perhaps, on his amendment, he may obtain that entire pardon which is now denied him; in the mean time, neighbor, keep him a recluse in your chamber."

"With all my heart," answered the barber. "Now, here come three together: the 'Araucana' of Don Alonzo de Ercilla, the 'Austriada' of Juan Rufo, a magistrate of Cordova, and the 'Monserrato' of Christoval de Virves, a poet of Valencia."

"These three books," said the priest, "are the best that are written in heroic verse in the Castilian tongue, and may stand in competition with the most renowned works of Italy. Let them be preserved as the best productions of the Spanish Muse."

The priest grew tired of looking over so many books, and therefore, without examination, proposed that all 25 the rest should be burnt; but the barber, having already opened one called the "Tears of Angelica," "I should have shed tears myself," said the priest, on hearing the name, "had I ordered that book to be burnt; for its author was one of the most celebrated poets, not only of Spain, but of the whole world: his translations from Ovid are admirable."

The same night the housekeeper set fire to and burnt all the books that were in the yard and in the house. Some must have perished that deserved to be treasured up in perpetual archives, but their destiny or the indolence of the scrutineer forbade it; and in them was fulfilled the saying, that—

"The just sometimes suffer for the unjust."

In the mean time Don Quixote tampered with a laborer, a neighbor of his, and an honest man (if such an epithet can be given to one that is poor), but shallow brained; in short, he said so much, used so many arguments, and made so many promises, that the poor fellow resolved to sally out with him and serve him in the capacity of a squire. Among other things, Don Quixote told him that he ought to be very glad to accompany him, for such an adventure might some time or the other occur, that by one stroke an island might be won, where he might leave him governor. With this and other promises, Sancho Panza (for that was the laborer's name) left his wife and children and engaged himself as squire to his neighbor.

Sancho Panza proceeded upon his ass, like a patriarch, with his wallet and leathern bottle, and with a 26 vehement desire to find himself governor of the island, which his master had promised him. Don Quixote happened to take the same route as on his first expedition, over the plain of Montiel, which he passed with less inconvenience than before, for it was early in the morning, and the rays of the sun, darting on them horizontally, did not annoy them. Sancho Panza now said to his master: "I beseech your worship, good sir knight-errant, not to forget your promise concerning that same island; for I shall know how to govern it, be it ever so large."

To which Don Quixote answered: "Thou must know, friend Sancho Panza, that it was a custom much in use among the knights-errant of old to make their squires governors of the islands or kingdoms they conquered, and I am determined that so laudable a custom, shall not be lost through my neglect; on the contrary, I resolve to outdo them in it: for they sometimes, and perhaps most times, waited till their squires were grown old; and when they were worn out in their service, and had endured many bad days and worse nights, they conferred on them some title, such as count, or at least marquis, of some valley or province of more or less account; but if you live, and I live, before six days have passed I may probably win such a kingdom as may have others depending on it, just fit for thee to be crowned king of one of them. And do not think this any extraordinary matter, for things fall out to knights by such unforeseen and unexpected ways, that I may easily give thee more than I promise."

"So then," answered Sancho Panza, "if I were a 27 king by some of those miracles your worship mentions, Joan Gutierrez, my duck, would come to be a queen, and my children infantas!"

"Who doubts it?" answered Don Quixote.

"I doubt it," replied Sancho Panza, "for I am verily persuaded that, if God were to rain down kingdoms upon the earth, none of them would sit well upon the head of Mary Gutierrez; for you must know, sir, she is not worth two farthings for a queen. The title of countess would sit better upon her, with the help of Heaven and good friends."

"Recommend her to God, Sancho," answered Don Quixote, "and he will do what is best for her, but do thou have a care not to debase thy mind so low as to content thyself with being less than a viceroy."

"Heaven grant us good success, and that we may speedily get this island which costs me so dear. No matter then how soon I die."

"I have already told thee, Sancho, to give thyself no concern upon that account; for, if an island cannot be had, there is the kingdom of Denmark or that of Sobradisa, which will fit thee like a ring to the finger. Besides, as they are upon terra firma, thou shouldst prefer them. But let us leave this to its own time, and see if thou hast anything for us to eat in thy wallet. We will then go in quest of some castle, where we may lodge this night and make the balsam that I told thee of, for I declare that my ear pains me exceedingly."

"I have here an onion and a piece of cheese, and I know not how many crusts of bread," said Sancho, "but they are not eatables fit for so valiant a knight as your worship."

28 "How little dost thou understand of this matter!" answered Don Quixote. "I tell thee, Sancho, that it is honorable in knights-errant not to eat once in a month; and, if they do taste food, it must be what first offers: and this thou wouldst have known hadst thou read as many histories as I have done; for, though I have perused many, I never yet found in them any account of knights-errant taking food, unless it were by chance and at certain sumptuous banquets prepared expressly for them. The rest of their days they lived, as it were, upon smelling. And though it is to be presumed they could not subsist without eating and satisfying all other wants,—as, in fact, they were men,—yet, since they passed most part of their lives in wandering through forests and deserts, and without a cook, their usual diet must have consisted of rustic viands, such as those which thou hast now offered me. Therefore, friend Sancho, let not that trouble thee which gives me pleasure, nor endeavor to make a new world, or to throw knight-errantry off its hinges."

"Pardon me, sir," said Sancho; "for, as I can neither read nor write, as I told you before, I am entirely unacquainted with the rules of the knightly profession; but henceforward I will furnish my wallet with all sorts of dried fruits for your worship, who are a knight; and for myself, who am none, I will supply it with poultry and other things of more substance."

There cannot be too much of a good thing.

What is lost to-day may be won to-morrow.

29 A saint may sometimes suffer for a sinner.

Many go out for wool and return shorn.

Matters of war are most subject to continual change.

Every man that is aggrieved is allowed to defend himself by all laws human and divine.

Truth is the mother of history, the rival of time, the depository of great actions, witness of the past, example and adviser of the present, and oracle of future ages.

Love, like knight-errantry, puts all things on a level.

He that humbleth himself God will exalt.3

After Don Quixote had satisfied his hunger, he took up a handful of acorns, and, looking on them attentively, gave utterance to expressions like these:—

"Happy times and happy ages were those which the ancients termed the Golden Age! Not because gold, so prized in this our Iron age, was to be obtained, in that fortunate period, without toil; but because they who then lived were ignorant of those two words, Mine and Thine. In that blessed age all things were in common; to provide their ordinary sustenance no other 30 labor was necessary than to raise their hands and take it from the sturdy oaks, which stood liberally inviting them to taste their sweet and relishing fruit. The limpid fountains and running streams offered them, in magnificent abundance, their delicious and transparent waters. In the clefts of rocks, and in hollow trees, the industrious and provident bees formed their commonwealths, offering to every hand, without interest, the fertile produce of their most delicious toil. The stately cork-trees, impelled by their own courtesy alone, divested themselves of their light and expanded bark, with which men began to cover their houses, supported by rough poles, only as a defence against the inclemency of the heavens. All then was peace, all amity, all concord. The heavy colter of the crooked plough had not yet dared to force open and search into the tender bowels of our first mother, who, unconstrained, offered from every part of her fertile and spacious bosom whatever might feed, sustain, and delight those, her children, by whom she was then possessed."

I think I see her now, with that goodly presence, looking as if she had the sun on one side of her and the moon on the other; and above all, she was a notable housewife, and a friend to the poor; for which I believe her soul is at this very moment in heaven.

A clergyman must be over and above good, who makes all his parishioners speak well of him.

Parents ought not to settle their children against their will.