The Torch Bearer

Title: The Torch Bearer: A Camp Fire Girls' Story

Author: I. T. Thurston

Release date: December 23, 2007 [eBook #23987]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

| BY I. T. THURSTON |

|

The Torch Bearer A Camp Fire Girls’ Story. Illustrated, 12mo, net $1.00. The author of “The Bishop’s Shadow” and “The Scout Master of Troop 5” has scored another conspicuous success in this new story of girl life. She shows conclusively that she knows how to reach the heart of a girl as well as that of a boy. |

|

The Scout Master of Troop 5 By author of “The Bishop’s Shadow.” Illustrated, 12mo, cloth, net $1.00. “The daily life of the city boys from whom the scouts are recruited is related, and the succession of experiences afterward coming delightfully to them—country hikes, camp life, exploring expeditions, and the finding of real hidden treasure. The depiction of boy nature is unusually true to life, and there are many realistic scenes and complications to try out traits of character.”—N. Y. Sun. |

|

The Big Brother of Sabin Street Containing the story of Theodore Bryan (The Bishop’s Shadow). Illustrated, 12mo, cloth, net $1.00. “This volume is the sequel to the Story of Theodore Bryan, ‘The Bishop’s Shadow,’ which came into prominence as a classic among boys’ books and was written to supply the urgent demand for a story continuing the account of Theodore’s work among the boys.”—Western Recorder. |

|

The Bishop’s Shadow Illustrated, cloth, net $1.00. “A captivating story of dear Phillips Brooks and a little street gamin of Boston. The book sets forth the almost matchless character of the Christlike bishop in most loving and lovely lines.”—The Interior. |

|

THE TORCH BEARER A Camp Fire Girls’ Story BY I. T. THURSTON Author of “The Bishop’s Shadow,” “The Scout Master of Troop 5,” Etc., Etc. ILLUSTRATED

New York Chicago Toronto Fleming H. Revell Company London and Edinburgh |

Copyright, 1913, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

|

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue |

To

M. N. T.

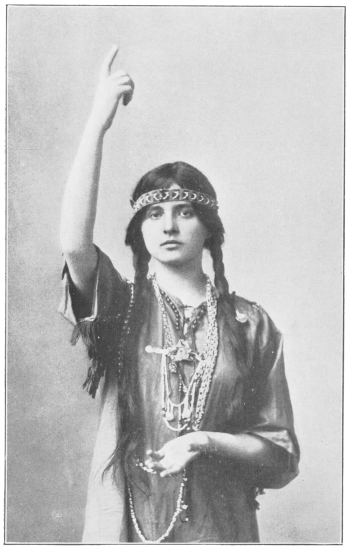

| The Torch Bearer | Frontispiece |

| “At Last a Tiny Puff of Smoke Arose” | 14 |

| “Soon the Flames Began to Blaze and Crackle, Filling the Air with a Spicy Fragrance” | 20 |

| A Group of Girls Busy Over Beadwork | 34 |

| “We Pull Long, We Pull Strong” | 78 |

| “Wood had Been Gathered Earlier in the Day” | 90 |

| A Favorite Rendezvous At the Camp | 212 |

| “Just Think of the Lookout This Very Minute!” | 220 |

| I. | The Camp in the Forest | 11 | |

| II. | Introducing the Problem | 24 | |

| III. | The Camp Coward Dares | 31 | |

| IV. | The Poor Thing | 44 | |

| V. | Wind and Weather | 65 | |

| VI. | A Water Cure | 77 | |

| VII. | Honours Won | 88 | |

| VIII. | Elizabeth At Home | 98 | |

| IX. | Jim | 119 | |

| X. | Sadie Page | 137 | |

| XI. | Boys and Old Ladies | 147 | |

| XII. | Nancy Rextrew | 155 | |

| XIII. | A Camp Fire Christmas | 168 | |

| XIV. | Lizette | 181 | |

| XV. | An Open Door For Elizabeth | 200 | |

| XVI. | Camp Fire Girls and the Flag | 212 | |

| XVII. | Sonia | 220 | |

| XVIII. | The Torch Uplifted | 233 | |

| XIX. | Clear Shining After Darkness | 243 |

“Wohelo—wohelo—wo-he-lo!”

The clear, musical call, rising from the green tangle of the forest that fringed the bay, seemed to float lingeringly above the treetops and out over the wide stretch of gleaming water, to a girl in a green canoe, who listened intently until the last faint echo died away, then began paddling rapidly towards the wooded slope. The sun, just dropping below the horizon, flooded the western sky with a blaze of colour that turned the wide waters into a sea of gold, through which the little craft glided swiftly, scattering from its slender prow showers of shining drops.

“I’m going to find out what that means,” the girl said under her breath. “It sounds like an Indian call, but I’m sure those were not Indian voices.”

On and on, steadily, swiftly, swept the green canoe, until, rounding a wooded point, it slipped suddenly into a beautiful little cove where there was a floating dock with a small fleet of canoes and rowboats surrounding it, and steps leading up the slope. The girl smiled as she stepped lightly out on the dock, and fastened her canoe to one of the rings.

“A girls’ camp it surely is,” she said to herself. “I’m going to get a glimpse of it anyhow.”

Running up the steps, she followed a well-trodden path through a pine grove, and in a few minutes, 12through the trees, she caught the gleam of white tents and stopped to reconnoitre. A dozen or more tents were set irregularly around an open space; also there was a large frame building with canvas instead of boarding on two sides, and adjoining this a small frame shack, evidently a kitchen—and girls were everywhere.

“O, I’m hungry for girls!” breathed the one peering through the green branches. “I wonder if I dare venture——” She broke off abruptly, staring in surprise at a group approaching her. Then she ran forward crying out, “Why, Anne Wentworth—to think of finding you here!”

“To think of finding you here, Laura Haven! Where did you drop from?” cried the other. The two were holding each other’s hands and looking into each other’s faces with eyes full of glad surprise.

“I? I didn’t drop—I climbed—up the steps from the landing,” Laura laughed. “I was out on the bay in my canoe—we came up yesterday in the yacht—and I heard that beautiful Indian call, and I just had to find out where it came from, and what it meant. I suspected a girls’ camp, but of course I never dreamed of finding you here. Do tell me all about it. It is a camp, isn’t it?”

“Yes, we are Camp Fire Girls,” Anne Wentworth replied. She glanced behind her, but the others had disappeared. “They vanished for fear they might be in the way,” she said. “O Laura, I’m so glad you’re here, for this is the night for our Council Fire. You can stay to it, can’t you—I’m sure you would be interested.”

“Stay—how long? It’s after sunset now.”

“O, stay all night with me, and all day to-morrow. 13You must stay to the Council Fire to-night, anyhow.”

“I’d love to dearly, but father won’t know where I am.” Laura’s voice was full of regret.

“Why can’t you go back and tell him? I’ll go with you,” Anne suggested.

“Will there be time before your Council Fire?”

“Yes, if we hurry—wait one minute.” Anne called to the nearest girl, gave her a brief message, and turned again to her friend. “Come on, we’ve no time to lose, but I know how you can make a canoe fly,” she said, and hand-in-hand the two went scurrying through the grove and down to the landing. Then while the canoe swept swiftly over the water, Anne Wentworth answered the eager questions of her friend.

“It’s a new organisation—the Camp Fire Girls,” she explained. “It is something like the Boy Scouts only, I think, planned on broader lines and with higher and finer ideals—at any rate it is better suited for girls. It aims to help them to be healthy, useful, trustworthy, and happy. Health—work—love—as shown in service—these are the ideals on which we try to build. We have three grades. First a girl becomes a Wood Gatherer; then after passing certain tests, a Fire Maker, then a Torch Bearer.”

“And which are you?” Laura asked.

“I’m a Guardian—that is, I am the head of one of our city Camp Fires. Mrs. Royall is our Chief Guardian.” She went on to explain about the work and play, the tests and rewards, ending with, “But you’ll understand it all so much better after our Council Fire to-night.”

14Laura nodded. “What kind of girls is it for—poor girls—working girls?” she asked.

“It is for any kind of girls—just girls, you know. Of course we can’t admit any bad ones, nothing else matters. Dorothy Groves is one of my twelve, and I’ve two dear little High School girls; all the rest are working girls. They can stay here at the camp only two weeks—some of them only ten days—the working girls, I mean, and it would make your heart ache to see how much those ten days mean to them, and how intensely they enjoy even the commonest pleasures of camping out.”

“Who pays for them?” Laura demanded.

“They pay for themselves. It’s no charity, and the charges are very low. They wouldn’t come if it were charity.”

Laura shook her head half impatiently. “It’s so hard to get a chance really to help the ones who need help most,” she said.

“Yes, it surely is,” Anne agreed; and then they were alongside the big white yacht with its shining brass, and Judge Haven was helping them up the steps.

Fifteen minutes later they were on their way back to the camp, but this time in a boat rowed by two of the crew. The last golden gleam of the afterglow was fading slowly in the West as the two girls came again through the pines into the open space between the tents. Mrs. Royall met them and made Laura cordially welcome.

“She’s just the right one—a real camp mother,” Anne said, as she led her friend over to a group gathered on the grass before one of the tents. “And these are my own girls,” she added, introducing each by name.

15“You’ve got to take me right in,” Laura told them. “I can’t help it if I am an odd number—I’m going to belong to this particular Camp Fire to-night.”

“Of course we’ll take you in, and love to. Aren’t you Miss Anne’s friend?” said one, as she snuggled down on the grass beside Laura. “It’s so nice you came on our Council Fire night!”

Laura’s eyes swept the group. “It must be nice—you all look so happy,” she answered.

Anne Wentworth excused herself for a few minutes, and Laura settled back against a tree with a little sigh of content. “I’ve been abroad for a year,” she said, “and it seems so good to be with girls again—American girls! Please, won’t you forget that I am here and talk just as if I were not? I want to sit still and enjoy the place and you and—everything, for a bit, before your Council begins.”

With ready courtesy they took her at her word, and chatted of camp plans and happenings until the talk was interrupted by a clear musical call that floated softly out of the gathering dusk.

“How beautiful! What is it?” Laura asked as all the girls started up.

“It’s the bugle call to the Council,” one explained, “and here comes Miss Anne.”

Laura glanced curiously at her friend’s dress. It was a long loose garment of dark brown, fringed at the bottom and the sleeves. A band of beadwork was fastened over her forehead, and she wore a long necklace of bright-coloured beads.

“What is it—a robe of state?” Laura inquired.

16“Yes, the ceremonial dress,” Anne told her, “but you can’t see in this light how pretty it is. Come on, we must join the procession.”

“What has become of your girls?” Laura asked. “They were here a moment ago.”

“They have gone to get their necklaces,” Anne returned. “My girls are all Wood Gatherers as yet—we’ve not been organised long, you know; but they’ve been working hard for honours, and for every honour they are entitled to add a bead to their necklaces.”

“Yours then must represent a great many honours.”

“Yes,” Anne replied. “You see it incites the girls to work for honours when they see that their Guardians have worked and won them. The red beads show that the wearer has won health honours by keeping free from colds, headaches, etc., for a number of months, or by sleeping out of doors, or doing some sort of athletics—walking, swimming, rowing, and the like. The blue ones are for nature study, the black and gold for business, and so on. Each bead has a meaning for the girl—it tells a story—and the more she wins, the finer her record, of course.”

“What a splendid idea! And how the girls will prize their necklaces by-and-by, and enjoy recalling the stories connected with them!”

“Yes,” Anne agreed, “they will hand them down to their daughters as a new kind of heirloom, but——” with a laugh she added, “that’s looking a long way ahead, isn’t it?”

By this time the two were in the midst of a merry procession of girls from twelve to twenty, perhaps a third of them wearing the ceremonial dress.

“What a gay company they are!” Laura commented, 17as the procession followed a winding path through the woods, a few carrying lanterns. “Is there anything in the world, Anne, lovelier than a crowd of happy girls?”

“Nothing,” her friend assented in a low tone. “And, Laura, if you could only see the difference a few days here make in some of the girls who have had all work and no play—like some of mine! It is so delightful to see them grow merry and glad day by day. But here we are. This is our Council Chamber.”

“I want as many eyes as a spider so that I can look every way at once,” Laura cried as the girls arranged themselves in a large circle. “What are those girls over there doing?”

“They are the Fire Makers. They were Wood Gatherers for over three months, and have met the requirements for the second class. Some of the others are to be made Fire Makers to-night. Watch Mary Walsh—the one rubbing two sticks. She will make fire without matches—or at least she will try to.”

The girl, with one knee on the ground, was rubbing one stick briskly back and forth in the groove of another. A little group beside her watched her with eager interest, two of them holding lanterns, and Mrs. Royall stood near her, watch in hand. The talk and laughter had ceased as the circle formed, and now in silence, all eyes were centred on the girl. Faster and faster her hands moved to the accompaniment of a whining, scraping sound that rose at intervals to a shrill squeak. At last a tiny puff of smoke arose, and the girl blew carefully until she had a glowing spark, which she fed with tiny shreds of wood, until 18suddenly it blazed up brightly. Then, springing lightly to her feet, she stood erect, the flaming wood in her outstretched hand distinctly revealing her happy, triumphant face against the dark background of the pines.

There was a quick clamour of applause as Mrs. Royall announced, “Thirty seconds within the time limit, Mary. Well done! Now light the Council Fire.”

The girl stepped forward and touched her flaming brand to the wood that had been made ready by the other Fire Makers, and soon the flames began to blaze and crackle, filling the air with a spicy fragrance, and sending a vivid glow across the circle of intent young faces. Laura caught her breath as she looked around the circle.

“What a picture!” she whispered. “It is lovely—lovely!”

At a signal from Mrs. Royall the girls now gathered closer about the fire and began to chant all together,

“‘Wohelo—wohelo—wohelo.

Wohelo means love.

We love love, for love is the heart of life.

It is light and joy and sweetness,

Comradeship and all dear kinship.

Love is the joy of service so deep

That self is forgotten.

Wohelo means love.’”

Then louder swelled the chorus,

“‘Wohelo for aye,

Wohelo for aye,

Wohelo, wohelo, wohelo for aye.’”

19The last note was followed by a moment of utter silence; then one side of the circle chanted,

“‘Wohelo for work!’”

and the opposite side flung back,

“‘Wohelo for health!’”

and all together they chorused exultantly,

“‘Wohelo, wohelo, wohelo for love!’”

Then in unison, led by Anne Wentworth, the beautiful Fire Ode was repeated,

“‘O Fire!

Long years ago when our fathers fought with great

animals you were their great protection.

When they fought the cold of the cruel winter you

saved them.

When they needed food you changed the flesh of beasts

into savoury meat for them.

During all the ages your mysterious flame has been

a symbol to them for Spirit.

So, to-night, we light our fire in grateful remembrance

of the Great Spirit who gave you to us.’”

In a few clear-cut sentences Mrs. Royall spoke of the Camp Fire symbolism—of fire as the living, renewing, all-pervading element—“Our brother the fire, bright and pleasant, and very mighty and strong,” as being the underlying spirit—the heart of this new order of the girls of America, as the hearth-fire is the heart of the home. She spoke of the brown chevron with the crossed sticks, the symbol of the Wood 20Gatherer, the blue and orange symbol of the Fire Maker, and the complete insignia combining both of these with the touch of white representing smoke from the flame, worn by the Torch Bearer, trying to make clear and vivid the beautiful meaning of it all.

When the roll-call was read, each girl, as she answered to her name, gave also the number of honours she had earned since the last meeting. It was then that Laura, watching the absorbed faces, shook her head with a sigh as her eyes met Anne’s; and Anne nodded with quick understanding.

“Yes,” she whispered, “there is some rivalry. It isn’t all love and harmony—yet. But we are working that way all the time.”

There was a report of the last Council, written in rather limping rhyme, and then each girl told of some kind or gentle deed she had seen or heard of since the last meeting—things ranging all the way from hunting for a lost glove to going for the doctor at midnight when a girl was taken suddenly ill in camp. Only one had no kindness to tell. And when she reported “Nothing” it was as if a shadow fell for a moment over all the young faces turned towards her.

“Who is that? Her voice sounds so unhappy!” Laura said, and her friend answered, “I’ll tell you about her afterwards. Her name is Olga Priest. There’s a new member to be received to-night. Here she comes.”

Laura watched the new member as she stepped out of the circle, and crossed over to the Chief Guardian.

21“What is your desire?” Mrs. Royall asked, and the girl answered,

“I desire to become a Camp Fire Girl and to obey the law of the Camp Fire, which is to

“‘Seek beauty,

Give service,

Pursue knowledge,

Hold on to health,

Glorify work,

Be happy.’

This law of the Camp Fire I will strive to follow.”

Slowly and impressively, Mrs. Royall explained to her the law, phrase by phrase, and as she ceased speaking, the candidate repeated her promise to keep it, and instantly every girl in the circle, placing her right hand over her heart, chanted slowly,

“‘This law of the fire I will strive to follow

With all the strength and endurance of my body,

The power of my will,

The keenness of my mind,

The warmth of my heart,

And the sincerity of my spirit.’”

And again after the last words—like a full stop in music—came the few seconds of utter silence.

It was broken by the Chief Guardian. “With this sign you become a Wood Gatherer,” and she laid the fingers of her right hand across those of her left. The candidate made the same sign; then she held out her hand, and Mrs. Royall slipped on her finger the silver ring, which all Camp Fire Girls are entitled to wear, and as she did so she said,

“‘As fagots are brought from the forest

Firmly held by the sinews which bind them,

So cleave to these others, your sisters,

Whenever, wherever you find them.

22Be strong as the fagots are sturdy;

Be pure in your deepest desire;

Be true to the truth that is in you;

And—follow the law of the fire.’”

The girl returned to her place in the circle, and at a sign from Anne Wentworth, four of her girls followed her as she moved forward and stood before Mrs. Royall. From a paper in her hand she read the names of the four girls, and declared that they had all met the tests for the second grade.

The Chief Guardian turned to the four.

“What is your desire?” she asked, and together they repeated,

“‘As fuel is brought to the fire

So I purpose to bring

My strength,

My ambition,

My heart’s desire,

My joy,

And my sorrow

To the fire

Of humankind.

For I will tend

As my fathers have tended,

And my father’s fathers

Since time began,

The fire that is called

The love of man for man,

The love of man for God.’”

As the young earnest voices repeated the beautiful words, Laura Haven’s heart thrilled again with the solemn beauty of it all, and tears crowded to her eyes in the silence that followed—a silence broken only by the whispering of the night wind high in the treetops.

23Then Mrs. Royall lifted her hand and soft and low the young voices chanted,

“‘Lay me to sleep in sheltering flame,

O Master of the Hidden Fire;

Wash pure my heart, and cleanse for me

My soul’s desire.

In flame of service bathe my mind,

O Master of the Hidden Fire,

That when I wake clear-eyed may be

My soul’s desire.’“

It was over, and the circle broke again into laughing, chattering groups. Lanterns were lighted, every spark of the Council Fire carefully extinguished, and then back through the woods the procession wound, laughing, talking, sometimes breaking into snatches of song, the lanterns throwing strange wavering patches of light into the dense darkness of the woods on either side.

“You did enjoy it, didn’t you?” Anne said as the two walked back through the woods-path to camp.

“I loved every bit of it,” was the enthusiastic response. “It’s so different from anything else—so fresh and picturesque and full of interest! I should think girls would be wild to belong.”

“They are. Camp Fires are being organised all over the country. The trouble is that there are not yet enough older girls trained for Guardians.”

“Where can they get the training?”

“In New York there is a regular training class, and there will soon be others in other cities,” Anne returned, and then, with a laugh, “I believe you’ve caught the fever already, Laura.”

“I have—hard. You know, Anne, all the time we were abroad I was trying to decide what kind of work I could take up, among girls, and this appeals to me as nothing else has done. It seems to me there are great possibilities in it. I’d like to be a Guardian. Do you think I’m fit?”

“Of course you’re fit, dear. O Laura, I’m so glad. We can work together when we go home.”

“But, Anne, I want to stay right here in this camp now. Do you suppose Mrs. Royall will be willing? Of course I’ll pay anything she says——”

25“She’ll be delighted. She needs more helpers, and I can teach you all I learned before I took charge of my girls. But will your father be willing?”

“I’m sure he will. He knows you, and everybody in Washington knows and honours Mrs. Royall. Father is going to Alaska on a business trip and I’ve been trying to decide where I would stay while he is gone. This will solve my problem beautifully.”

“Come then—we’ll see Mrs. Royall right now and arrange it,” Anne returned, turning back.

Mrs. Royall was more than willing to accede to Laura’s proposal. “Stay at the camp as long as you like,” she said, “and if you really want to be a Guardian, I will send your name to the Board which has the appointing power.”

“She is lovely, isn’t she?” Laura said as they left the Chief Guardian. “I don’t wonder you call her the Camp Mother.”

Something in the tone reminded Anne that her friend had long been motherless, and she slipped her arm affectionately around Laura’s waist as she answered, “She is the most motherly woman I ever met. She seems to have room in her big, warm heart for every girl that wants mothering, no matter who or what she is.” They were back at the camp now, and she added, “But we must get to bed quickly—there’s the curfew,” as a bugle sounded a few clear notes.

“O dear, I’ve a hundred and one questions to ask you,” sighed Laura.

“They’ll keep till morning,” replied the other. “It’s so hard for the girls to stop chattering after the curfew sounds! We Guardians have to set them a good example.”

26The cots in the sleeping tents were placed on wooden platforms raised three or four inches from the ground, and on clear nights the sides of the tents were rolled up. Laura, too interested and excited to sleep at once, lay in her cot looking out across the open space now flooded with light from the late-risen moon, and thought of the girls sleeping around her. Herself an only child, she had a great desire—almost a passion—for girls; girls who were lonely like herself—girls who had to struggle with ill-health, poverty, and hard work as she did not.

Suddenly she started up in bed, her eyes wide with half-startled surprise. Reaching over to the adjoining cot, she touched her friend, whispering, “Anne, Anne, look!” and as Anne opened drowsy eyes, Laura pointed to the moonlit space.

Anne stared for a moment, then she laughed softly and whispered back, “It’s a ghost dance, Laura. Some of those irrepressible girls couldn’t resist this moonlight. They’re doing an Indian folk dance.”

“Isn’t it weird—in the moonlight and in utter silence!” Laura said under her breath. “I should think somebody would giggle and spoil the effect.”

“That would be a signal for Mrs. Royall to ‘discover’ them and send them back to bed,” Anne returned. “So long as they do it in utter silence so as to disturb no one else, the Guardians wink at it. It is pretty, isn’t it?”

“Lovely!”

Anne turned over and went to sleep again, but Laura watched the slender graceful figures in their loose white garments till suddenly they melted into the shadows and were gone. Then she too slept till a 27shaft of sunlight, touching her eyelids, awakened her to a new day. She looked across at her friend, who smiled back at her. “I feel so well and so happy!” she exclaimed.

“It is sleeping in the open air,” Anne replied. “Almost everybody wakes happy here—except the Problem.”

“The Problem?” Laura echoed.

“I mean Olga Priest, the girl you asked about last night. We Guardians call her the Problem because no one has yet been able to do anything for her.”

“Tell me about her,” Laura begged, as, dropping the sides of the tent, Anne began to dress.

“Wait till we are outside—there are too many sharp young ears about us here,” Anne cautioned. “There’ll be time for a walk or a row before breakfast and we can talk then.”

“Good—let’s have a walk,” Laura said, and made quick work of her dressing.

“Now tell me about the Problem,” she urged, when they were seated on a rocky point overlooking the blue waters of the bay.

“Poor Olga,” Anne said. “I wonder sometimes if she has ever had a really happy day in the eighteen years of her life. Her mother was a Russian of good family and well educated. She married an American who made life bitter for her until he drank himself to death. There were three children older than Olga—two sons who went to the bad, following their father’s example. The older girl married a worthless fellow and disappeared, and there was no one left but Olga to support the sick mother and herself, and Olga was only thirteen then! She supported them, somehow, 28but of course she had to leave her mother alone all day, and one night when she went home she found her gone. She had died all alone.”

“O!” cried Laura.

“Yes, it was pitiful. I suppose the child was as nearly heartbroken as any one could be, for her mother was everything to her. Of course there were many who would have been glad to help had they known, but Olga’s pride is something terrible, and it seems as if she hates everybody because her father and her brothers and sister neglected her mother, and she was left to die alone. I don’t believe there is a single person in the world whom she likes even a little.”

“O, the poor thing!” sighed Laura. “Not even Mrs. Royall?”

“No, not even Mrs. Royall, who has been heavenly kind to her.”

“Is she in your Camp Fire?”

“No, Ellen Grandis is her Guardian, but Ellen is to be married next month and will live in New York, so that Camp Fire will have to have a new Guardian.”

“What about the other girls in it?”

“All but three are working girls—salesgirls in stores, I think, most of them.”

“How did Olga happen to join the Camp Fire?”

“I don’t know. I’ve wondered about that myself. She doesn’t make friends with any of the girls, nor join in any of the games; but work—she has a perfect passion for work, and it seems as if she can do anything. She has won twice as many honours as any other girl since she came, but she cares nothing for them—except to win them.”

“She must be a strange character, but she interests 29me,” Laura said thoughtfully. “Anne, maybe I can take Miss Grandis’ place when she leaves.”

Anne gave her friend a searching look. “Are you sure you would like it? Wouldn’t you rather have a different class of girls?” she asked.

Laura answered gravely, “I want the girls I can help most—those that need me most—and from what you say, I should think Olga needed—some one—as much as any girl could.”

“As much perhaps, but hardly more than some of the others. There’s that little Annie Pearson who thinks of nothing but her pretty face and ‘good times,’ and Myra Karr who is afraid of her own shadow and always clinging to the person she happens to be with. The Camp Fire is a splendid organisation, Laura, and it will do a deal for the girls, but still almost every one of them is some sort of ‘problem’ that we have to study and watch and labour over with heart and head and hands if we hope really to accomplish any permanent good. But come, we must go back or we shall be late for breakfast.”

“Then let’s hurry, for this air has given me a famous appetite,” Laura replied. But she did not find it easy to keep up with her friend’s steady stride.

“You’ll have to get in training for tramps if you are going to be a Camp Fire Girl,” Anne taunted gaily.

Laura’s eyes brightened as she entered the big dining-room with its canvas sides rolled high.

“Just in time,” Anne said, as she pulled out a chair for Laura and slipped into the next one herself.

The meal was cheerful, almost hilarious. “Mrs. Royall believes in laughter. She never checks the 30girls unless it’s really necessary,” Anne explained under cover of the merry chatter. “She——”

But Laura interrupted her. “O Anne, that must be Olga—the dark still girl, at the end of the next table, isn’t it?”

“Yes, and Myra Karr is next to her. All at that table belong to the Busy Corner Camp Fire.”

After breakfast Laura again paddled off to the yacht with Anne. It did not require much coaxing to secure her father’s permission for her to spend a month at the camp with Anne Wentworth and Mrs. Royall. He kept the girls on the yacht for luncheon, and after that they went back to camp, a couple of sailors following in another boat with Laura’s luggage.

“How still it is—I don’t hear a sound,” Laura said wonderingly, as she and her friend approached the camp through the pines.

Anne listened, looking a little perplexed, as they came out into the camp and found it quite deserted—not a girl anywhere in sight.

“I’ll go and find out where everybody is,” she said. “I see some one moving in the kitchen. The cook must be there.”

She came back laughing. “They’ve all gone berrying. That’s one of the charms of this camp—the spontaneous fashion in which things are done. Probably some one said, ‘There are blueberries over yonder—loads of them,’ and somebody else exclaimed, ‘Let’s go get some,’ and behold”—she waved her hand—“a deserted camp.”

Each girl at the camp was expected to make her own bed and keep her belongings in order. Each one also served her turn in setting tables, washing dishes, etc. Beyond this there were no obligatory tasks, but all the girls were working for honours, and most of them were trying to meet the requirements for higher rank. Some were making their official dresses. Girls who were skilful with the needle could secure beautiful and effective results with silks and beads, and of course every girl wanted a headband of beadwork and a necklace—all except Olga Priest. Olga was working on a basket of raffia, making it from a design of her own, when Ellen Grandis, her Guardian, came to her just after Anne Wentworth and Laura had left the camp.

“I’ve come to ask your help, Olga,” Miss Grandis began.

The girl dropped the basket in her lap, and waited.

Miss Grandis went on, “It is something that will require much patience and kindness——”

“Then you’d better ask some one else, Miss Grandis. You know that I do not pretend to be kind,” Olga interrupted, not rudely but with finality.

“But you are very patient and persevering, and—I don’t know why, but I have a feeling that you could do more for this one girl than any one else here could. 32She is coming to take the only vacant place in our Camp Fire. Shall I tell you about her, Olga?”

“If you like.” The girl’s tone was politely indifferent.

With a little sigh Miss Grandis went on, “Her name is Elizabeth Page. She is about a year younger than you, and she has had a very hard life.”

Olga’s lips tightened and a shadow swept across her dark eyes.

Miss Grandis continued, “You have superb health—this girl has perhaps never been really well for a single day. You have a brain and hands that enable you to accomplish almost what you will. Poor Elizabeth can do so few things well that she has no confidence in herself: yet I believe she might do many things if only she could be made to believe in herself a little. She needs—O, everything that the Camp Fire can do for a girl. Olga, won’t you help us to help her?”

“How can I?” There was no trace of sympathy in the cold voice, and suddenly the eager hopefulness faded out of Miss Grandis’ face.

“How can you indeed, if you do not care. I am afraid I made a mistake in coming to you, after all,” she said sadly. “I’m sorry, Olga—sorry even more on your account than on Elizabeth’s.”

With that she rose and went away, and Olga looked after her thoughtfully for a moment before she took up her work again.

A little later Myra Karr stood looking down at her with a curious expression in her wide blue eyes.

“I’m—I’m going to walk to Kent’s Corners,” she announced, with a little nervous catch in her voice.

33“Well, what of it? You’ve been there before, haven’t you?” Olga retorted.

“Yes, but this time I’m going all alone!”

Olga’s only reply was a swift mocking smile.

“I am—Olga Priest!” repeated Myra, stamping her foot angrily. “You all think me a coward—I’ll just show you!” and with that she whirled around and marched off, her chin up and her cheeks flushed.

As she passed a group of girls busy over beadwork, one of them called out, “What’s the matter, Bunny?”

Myra paused and faced them. “I’m going to walk to Kent’s Corners alone!” she cried defiantly.

A shout of incredulous laughter greeted that.

“Better give it up before you start, Bunny,” said one.

Another, with a mischievous laugh, whisked out her handkerchief and in a flash had twisted it into a rabbit with flopping ears. “Bunny, bunny, bunny!” she called, making the rabbit hop across her lap.

Myra’s blue eyes filled with angry tears. “You’re horrid, Louise Johnson!” she cried out. “You’re all horrid. But I’ll show you!” and with a glance that swept the whole laughing group, she threw back her head and marched on.

The girls looked after her and then at each other.

“Believe she’ll really do it?” one questioned doubtfully.

“Not she. Maybe she’ll get as far as the village,” replied another.

“She’d never dare pass Slabtown alone—never in the world,” a third declared with decision.

34“Poor Myra, I’m sorry for her. It must be awful to be scared at everything as she is!” This from Mary Hastings, a big blonde who did not know what fear was.

“Bunny certainly is the scariest girl in this camp,” laughed Louise Johnson carelessly. “She’s afraid of her own shadow.”

“Then she ought to have more credit than the rest of us when she does do a brave thing,” put in little Bess Carroll in her gentle way.

“We’ll give her credit all right if she goes to Kent’s Corners,” retorted Louise.

Just then another girl ran up to the group and announced that a blueberry picnic had been arranged. Somebody had discovered a pasture where the bushes were loaded with luscious fruit. They would carry lunch, and bring back enough for a regular blueberry festival.

“All who want to go, get baskets or pails and come on,” the girl ended.

In an instant the others were on their feet, work thrown aside, and five minutes later there was no one but the cook left in the camp.

35By that time Myra Karr was tramping steadily on towards Kent’s Corners. Scarcely another girl in the camp would have minded that walk, but never before had she dared to take it alone; now in spite of her nervous fears, she felt a little thrill of incredulous pride in herself. So many times she had planned to do this thing, but always before her courage had failed. Now, now she was really doing it! And if she went all the way perhaps—O, perhaps the girls would stop calling her Bunny. How she hated that name! She hurried on, her heart beating hard, her hands tight-clenched, her eyes fearfully searching the long sunny road before her and the woods or fields that bordered it. It was not so bad the first part of the way—the mile and a half to the little village of East Bassett. To be sure, she had never before been even that far alone, but she had been many times with other girls. She passed slowly and lingeringly through the village. Should she turn back now? Before her flashed the face of Olga with that little cold mocking smile, and she saw again Louise Johnson hopping her handkerchief rabbit across her lap. The incredulous laughter with which the others had greeted her announcement rang still in her ears. She was walking very very slowly, but—but no, she wouldn’t—she couldn’t turn back. She forced her unwilling feet to go on—to go faster, faster until she was almost running. She was beyond the village now and another mile and a half would bring her to Slabtown. Slabtown! She had forgotten Slabtown. The colour died swiftly out of her face as she remembered it now. Even with a crowd of girls she had never passed the place without a fearful shrinking, and now alone—could she pass those ugly cabins swarming with rough, dirty men and slovenly women and rude, staring children? Her knees trembled under her even at the thought, and her newborn courage melted like wax. It was no use. She could not do it. She wavered, stopped, and turned slowly around. As she did so a grey rabbit with a white tail scurried across the road before her, his ears flattened against his head and his eyes bulging with terror. The sight of him suddenly steadied the girl. She stood still looking after the tiny grey streak flying across a wide 36green pasture, and a queer crooked smile was on her trembling lips.

“A bunny—another bunny,” she said under her breath, “and just as scared as I am—at nothing. I won’t be a bunny any longer! I won’t be the camp coward—I won’t, won’t, won’t!” she cried aloud, and turning, went on again swiftly with her head lifted. A bit of colour drifted back to her white cheeks, and her heart stopped its heavy thumping as she drew a long deep breath. She would not let herself think of Slabtown. She counted the trees she passed, named the birds that wheeled and circled about her, even repeated the multiplication table—anything to keep Slabtown out of her thoughts; but all the while the black dread of it was there in the back of her mind. When she caught sight of the sawmill where the Slabtown men earned their bread, her feet began to drag again.

“I can’t—O, I can’t!” she sobbed out, two big tears rolling down her cheeks. Then across her mind flashed a vision of the little cottontail streaking madly across the road before her, and again some strange new power within urged her on. She went on slowly, reluctantly, with dragging feet, but still she went on. There were no men about the place at this hour—they were at work—but untidy women sat on their doorsteps or rocked at the windows, and a horde of ragged barefooted children catching sight of the girl swarmed out into the road to stare at her. Some begged for pennies, and getting none, yelled after her and threw stones till she took to her heels and ran “just like the other bunny!” she told herself in miserable scorn, when once she was safely past the settlement. Well, 37there was no other such place to pass, but—she shivered as she remembered that she must pass this one again on the way back.

She went on swiftly now with only occasionally a fearful glance on either side when the road cut through the woods. Once a farmer going by offered her a ride; but she shook her head and plodded on. It was half-past eleven when, with a great throb of relief and joy, she came in sight of the Corners. A few minutes more and she was in the village street with its homey-looking white houses and flower gardens. She longed to stop and rest on one of the vine-shaded porches, but she was too shy to ask permission. At the store she did stop, and rested a few minutes in one of the battered wooden chairs on the little porch, but it was sunny and hot there. Now for the first time she thought of lunch, but she had not a penny with her; she must go hungry until she got back to camp. A boy came up the steps munching a red apple, his pockets bulging with others. The storekeeper’s little girl ran out on the porch with a big molasses cooky just out of the oven, and the warm spicy odour of it made Myra realise how hungry she was. She looked so longingly at the cooky that the child, seeming to read her thoughts, crowded it all hastily into her own mouth. Myra laughed a bit at that, and after a little rest, set off on her return. She was tired and hungry, but a strange new joy was throbbing at her heart. She had come all the way to Kent’s Corners alone—they could not call her a coward now! That thought more than balanced her weariness and hunger. She had to walk all the way back—she had to pass Slabtown again. Yes, but now she was 38not afraid—not afraid! She drew herself up to her slender height, threw back her head, and laughed aloud in the joy of her deliverance from the fear that had held her in bondage all her life. She didn’t understand in the least how it had happened, but she knew that at last she was free—free—like the other girls whom she had envied; and dimly she began to realise that this was a big thing—something that would make all her life different. She walked as if she were treading on air. The loneliness of the woods, of the long stretch of empty road, no longer filled her with trembling terror.

As for the second time she approached Slabtown, her heart began to beat a little faster, but the newborn courage did not fail her now. She found herself whistling a gay tune and laughed. Whistling to keep her courage up? Was that what she was doing? Never mind—the courage was up. The women still sat on their doorsteps or stared from their windows, but this time the children did not swarm around her. They stood by the roadside and stared, but none called after her or followed her. She did not realise how great was the difference between the girl who now walked by with shining eyes and lifted head, and the white-faced trembling little creature with terror writ large in every line of her face and figure that had scurried by earlier in the day. But the children realised it. Instinctively now they knew her unafraid, and they did not venture to badger her. She even smiled and waved her hand to them as she went by, and at that a youngster of a dozen years suddenly broke out, “Three cheers fer the girl—now, fellers!” And with the echo of the shrill response ringing in her 39ears, Myra passed on, proud and happy as never before in her life.

All the rest of the way she went with the new happy consciousness making music in her heart—the consciousness of victory won. The last mile or two her feet dragged, but it was from weariness and lack of food. As she drew near the camp her steps quickened, her head went up again, and her eyes began to shine; but when she came to the white tents, she stood looking about in blank amazement. There was not a girl anywhere in sight; even the cook was missing.

Myra stood for a moment wondering where they had all gone; then she walked slowly across the camp to a hammock swung behind a clump of low-growing pines. Dropping into the hammock, she tucked a cushion under her head and, with a long sigh of delicious content and restfulness her eyes closed and in two minutes she was sound asleep—so sound asleep that when, an hour later, the girls came straggling back with pails and baskets full of big luscious berries, the gay cries and laughter and chatter of many voices did not arouse her.

The girls trooped over to the kitchen and delivered up their spoil to the cook.

“Now, Katie,” cried one, “you must make us some blueberry flapjacks for supper—lots and lots of ’em, too!”

“And blueberry gingerbread,” added another.

“And pies—fat juicy pies,” called a third.

“And rolypoly—blueberry rolypoly!” shouted yet another.

The cook, her arms on her hips, stood laughing into the sun-browned young faces before her.

40“Sure ye’re not askin’ me to make all them things fer ye to-night!” she protested gaily.

“We-ell, not all maybe. We can wait till to-morrow for some of them. But heaps and heaps of flapjacks, Katie dear, if you love us, and you know you do,” coaxed Louise Johnson.

“Love ye? Love ye, did ye say?” laughed the cook. “Be off wid ye now an’ lave me in pace or ye’ll not get a smirch of a flapjack to yer supper. Shoo!” and she waved them off with her apron.

As the laughing girls turned away from the kitchen, Mary Hastings came towards them from the other side of the camp.

“What’s the matter, Molly? You look as sober as an owl!” cried Louise who never looked sober.

“It’s Myra—she isn’t here. Miss Grandis and I have hunted all over the camp for her,” Mary answered. “You know she started for Kent’s Corners before we went berrying.”

“So she did,” cried another girl, the merriment dying out of her eyes. “You don’t suppose she really went there?”

“Myra Karr—alone—to Kent’s Corners? Never in the world,” Louise flung out carelessly. “She’s somewhere about. Let’s call her.” She lifted her voice and called aloud, “Myra, Myra, My-raa!”

At the call Mrs. Royall came hastily towards them. “Where is Myra? Didn’t she go berrying with us?” she inquired.

“No,” Louise explained lightly. “Bunny got her back up this morning and said she was going alone to Kent’s Corners, but of course she didn’t. She’s started 41that stunt half a dozen times and always backed out. She’s just around somewhere.”

But Mrs. Royall still looked troubled. “She must be found,” she said with quick decision. “Get the megaphone, Louise, and call her with that.”

Still laughing, Louise obeyed. Her clear voice carried well, and many keen young ears were strained for the response that did not come. In the silence that followed a second call, Mrs. Royall spoke to another girl.

“Edith, get your bugle and sound the recall. If that does not bring her, two of you must hurry over to the farm and harness Billy into the buggy; and I will drive to Kent’s Corners at once.”

The girls were no longer laughing. “You don’t think anything could have happened to Myra, Mrs. Royall?” one of them questioned anxiously. “Almost all of us have walked over there. I went alone and so did Mary.”

“I know, but Myra is such a timid little thing. She cannot do what most of you can.”

Edith Rue came running back with her bugle, and in a moment the notes of the recall floated out on the still summer air. It was a rigid rule of the camp that the recall should be promptly answered by any girl within hearing, so when, in the silence that followed, no response was heard, Mrs. Royall sent the two girls for the horse and buggy.

“Have them here as quickly as possible,” she called after them.

Before the messengers were out of sight, however, there was an outcry behind them.

“Why, there she is! There’s Myra now!” and 42every face turned towards the small figure coming from the clump of evergreens, her eyes still half-dazed with sleep.

With an exclamation of relief, Mrs. Royall hurried to meet her.

“Where were you, child? Didn’t you hear us calling you?” she asked.

“I—I—no. I heard the recall, and I came—I guess I was asleep,” stammered Myra bewildered by something tense in the atmosphere, and the eyes all centred on her.

“Asleep!” echoed Louise Johnson with a chuckle. “What did I tell you, girls?”

But Mrs. Royall saw that Myra looked pale and tired, and she noticed the change that came over her face as Louise spoke. A quick wave of colour swept the pale cheeks and the small head was lifted with an air that was new and strange—in Myra Karr. Mrs. Royall spoke again, laying her hand gently on the girl’s shoulder.

“Myra, how long have you been asleep? How long have you been back in camp?”

And Myra answered quietly, but with that new pride in her voice, “It was quarter of four by the kitchen clock when I came. There was nobody here—not even Katie——”

“I’d just run out a bit to see if anny of ye was comin’,” put in the cook from the kitchen door where she stood, as much interested as any one else in what was going on.

“And did you go to Kent’s Corners, my dear?” Mrs. Royall questioned gently.

It was Myra’s hour of triumph. She forgot Louise 43Johnson’s mocking laugh—forgot everything but her beautiful new freedom.

“O, I did—I did, Mrs. Royall!” she cried out. “I was awfully frightened at first, but coming home I wasn’t one bit afraid, and, please, you won’t let them call me Bunny any more, will you?”

“No, my child, no. You’ve won a new name and you shall have it at the next Council Fire. I’m so glad, Myra!” Mrs. Royall’s face was almost as radiant as the girl’s.

It was Louise Johnson who called out, “Three cheers for Myra Karr! She’s a trump!”

The cheers were given with a will. Tears filled Myra’s eyes, but they were happy tears, as the girls crowded around her with questions and exclamations, and Miss Grandis stood with a hand on her shoulder.

“That’s what Camp Fire has done for one girl,” Mrs. Royall said in a low tone to Laura Haven. “That child was afraid of the dark, afraid of the water, afraid to be alone a minute, when she came. It is a great triumph for her—a great victory.”

“Yes,” returned Laura thoughtfully, and Anne added,

“You’ve no idea how lonesome the camp looked when Laura and I came back and found you all gone. It was so still it seemed almost uncanny. Myra never would have dared to stay alone here before.”

A week later Miss Grandis was called home by illness in her family, and she asked Laura to drive to the station with her.

“I wanted the chance to talk with you,” she explained, as they drove along the quiet country road. “You know I should not have been able to stay here much longer anyhow, and now I shall not come back, and I want you to take charge of my girls. Will you?”

“O, I can’t yet—I haven’t had half enough training,” Laura protested.

“I know, but you’ve put so much into the time you have had in camp, and I know that Mrs. Royall will be glad to have you in my place. You can keep on with your training just the same. I want to tell you about the girls.” She told something of the environment of each one—enough to help Laura to understand their needs. “And there’s Elizabeth Page, who is coming to-morrow,” she went on. “I always think of her as the Poor Thing. O, I do so hope the Camp Fire will do a great deal for her—she’s had so pitifully little in her life thus far. Her mother died when she was a baby, and she has been just a drudge for her stepmother and the younger children, and she’s not strong enough for such hard work. She’s never had anything for herself. The camp will seem like paradise 45to her if she can only get in touch with things—I’m sure it will.”

“I’ll do my best for her,” Laura promised.

“I know you will. And you’ll meet her when she comes, to-morrow?”

“Of course,” Laura returned.

There was no time to spare when they reached the station, but Miss Grandis’ last word was of Elizabeth and her great need.

Laura was at the station early the next day, and would have recognised the Poor Thing even if she had not been the only girl leaving the train at that place. Elizabeth was seventeen, but she might have been taken for fourteen until one looked into her eyes—they seemed to mirror the pain and privation of half a century. Laura’s heart went out to her in a wave of pitying tenderness, but the girl drew back as if frightened by the warm friendliness of her greeting.

All the way back to camp she sat silent, answering a direct question with a nod or shake of the head, but never speaking; and when, at the camp, a crowd of girls came to meet the newcomer, she looked wildly around as if for refuge from all these strangers. Seeing this, Laura, with a whispered word, sent the girls away, and introduced Elizabeth only to Mrs. Royall and Anne Wentworth.

“Another scared rabbit?” giggled Louise Johnson.

“Don’t call her that, Louise,” said Bessie Carroll. “I’m awfully sorry for the poor thing.”

Laura, overhearing the low-spoken words, said to herself, “There it is—Poor Thing. That name is bound to cling to her, it fits so exactly.”

It did fit exactly, and within two days Elizabeth was 46the Poor Thing to every girl in the camp. Laura kept the child with her most of the first day; she was quiet and still as a ghost, did as she was told, and watched all that went on, but she spoke to no one and never asked a question. At night she was given a cot next to Olga’s. When Laura showed her her place at bedtime, she pointed to the adjoining tent.

“I sleep right there, Elizabeth,” she said, “and if you want anything in the night, just speak, and I shall hear you. But I hope you will sleep so soundly that you won’t know anything till morning. It’s lovely sleeping out of doors like this!”

Elizabeth said nothing, but she shivered as she cast a fearful glance into the shadowy spaces beyond the tents, and Laura hastened to add, “You needn’t be a bit afraid. Nothing but birds and squirrels ever come around here.”

Elizabeth went early to bed, and was apparently sound asleep when the other girls went to their cots. But after all was still and the camp lights out, she lay trembling, and staring wide-eyed into the darkness. A thousand strange small sounds beat on her strained ears, and when suddenly the hoot of an owl rang out from a nearby treetop, Elizabeth sprang up with a frightened cry and clutched wildly at the girl in the nearest cot.

Olga’s cold voice answered her cry. “It’s nothing but an owl, you goose! Go back to your bed!”

But Elizabeth was on her knees, clinging desperately to Olga’s hand.

“O, I’m afraid, I’m afraid!” she moaned. “Please please let me stay here with you. I never was in a p-place like this before.”

47Olga jerked her hand away from the clinging fingers. “Get back to your bed!” she ordered under her breath. “Anybody’d think you were a baby.”

“I don’t care what anybody’d think if you’ll only let me stay. I—I must touch s-somebody,” wailed the Poor Thing in a choked voice.

“Well, it won’t be me you’ll touch,” retorted Olga. “And if you don’t keep still I’ll report you in the morning. You’ll have every girl in the camp awake presently.”

“O, I don’t care,” sobbed Elizabeth under her breath. “I—I want to go home. I’d rather die than stay here!”

“Well, die if you like, but leave the rest of us to sleep in peace,” muttered Olga, and turning her face away from the wretched little creature crouching at her side, she went calmly to sleep.

When she awoke she gave a casual glance at the next cot. It was empty, but on the floor was a small huddled figure, one hand still clutching Olga’s blanket. Olga started to yank the blanket away, but the look of suffering in the white face stayed her impatient hand. She touched the thin shoulder of Elizabeth, and for once her touch was almost gentle. Elizabeth opened her eyes with a start as Olga whispered, “Get back to your bed. There’s an hour before rising time.”

Elizabeth crawled slowly back to her own cot, but she did not sleep again. Neither did Olga, and she was uncomfortably aware that a pair of timid blue eyes were on her face until she turned her back on them.

At ten o’clock that morning the girls all trooped down to the water. Some in full knickerbockers and 48middy blouses were going to row or paddle, but most wore bathing suits. With some difficulty Laura persuaded Elizabeth to put on a bathing suit that Miss Grandis had left for her, but no urging or coaxing could induce her to go into the water even to wade, though other girls were swimming and splashing and frolicking like mermaids. Elizabeth sat on the sand, her eyes following Olga’s dark head as the girl swept through the water like a fish—swimming, floating, diving—she seemed as much at home in the water as on land.

“You can do all those things too, Elizabeth, if you will,” Laura told her. “Look at Myra, there—she has always been afraid to try to swim, but she’s learning to-day, and see how she is enjoying it.”

Elizabeth drew further into her shell of silence. She cast a fleeting glance at Myra Karr, nervously trying to obey Mary Hastings’ directions and “act like a frog”—then her eyes searched again for Olga, now far out in the bay.

When she could not distinguish the dark head, anxiety at last conquered her timidity, and she turned to Laura:

“O, is she drowned?” she cried under her breath. “Olga—is she?”

Anne Wentworth laughed out at the question. “Why, Elizabeth,” she said, leaning towards her, “Olga’s a perfect fish in the water. She’s the best swimmer in camp. Look—there she comes now.”

She came swimming on her side, one strong brown arm cutting swiftly and steadily through the water. When presently she walked up on the beach, a pale smile glimmered over Elizabeth’s face, but it vanished 49at Olga’s glance as she passed with the scornful fling—“Haven’t even wet your feet—baby!”

Elizabeth’s face flushed and she drew her bare feet under her.

“Never mind, you’ll wet them to-morrow, won’t you, Elizabeth?” Laura said; but the Poor Thing made no reply; she only gulped down a sob as she looked after the straight young figure in the dripping bathing suit marching down the beach.

“She notices no one but Olga,” Laura said as she walked back to camp with her friend. “If Olga would only take an interest in her!”

“If only she would!” Anne agreed. “But she seems to have no more feeling than a fish!”

Many of the girls did their best to draw the Poor Thing out of her shell of scared silence, but they all failed. And Olga would do nothing. Yet Elizabeth followed Olga like her shadow day after day. Olga’s impatient rebuffs—even her angry commands—only made the Poor Thing hang back a little.

When things had gone on so for a week, Laura asked Olga to go with her to the village. She went, but they were no sooner on the road than she began abruptly, “I know what you want of me, Miss Haven, but it’s no use. I can’t be bothered with that Poor Thing—she makes me sick—always hanging around and wanting to get her hands on me. I can’t stand that sort of thing, and I won’t—that’s all there is about it. I’ll go home first.”

When Laura answered nothing, Olga glanced at her grave face and went on sulkily, “Nobody ought to expect me to put up with an everlasting trailer like that girl.”

50Still Laura was silent until Olga flung out, “You might as well say it. I know what you are thinking of me.”

“I wasn’t thinking of you, Olga. I was thinking of Elizabeth. If you saw her drowning you’d plunge in and save her without a moment’s hesitation.”

“Of course I would—but I wouldn’t have her hanging on to me like a leech after I’d saved her.”

“I suppose you have not realised that in ‘hanging on’ to you—as you express it—she is simply fighting for her life.”

“What do you mean, Miss Haven?”

“I mean that Elizabeth is—starving. Not food starvation, but a worse kind. Olga, this is the first time in her life that she has ever spent a day away from home—she told me that—or ever had any one try to make her happy. Is it any wonder that she doesn’t know how to be happy or make friends? It seems strange that, from among so many who would gladly be her friends here, she should have chosen you who are not willing to be a friend to any one—strange, and a great pity, it seems. It throws an immense responsibility upon you.”

“I don’t want any such responsibility. I don’t think any of you ought to put it on me,” Olga flung out sulkily.

“We are not putting it on you,” returned Laura gently.

Olga twitched her shoulder with an impatient gesture, and the two walked some distance before she spoke again. Then it was to say, “What are you asking me to do, anyhow?”

“I am not asking you to do anything,” Laura answered. 51“It is for you to ask yourself what you are going to do. I believe it is in your power to make over that poor girl mind and body—I might almost say, soul too. She thinks she can do nothing but household drudgery. She is afraid of everything. When I think of what you could do for her in the next month—Olga, I wonder that you can let such a wonderful opportunity pass you by.”

They went the rest of the way mostly in silence. When they returned to the camp, Elizabeth was watching for them, but the glance Olga gave her was so repellent that she shrank away, and went off alone to the Lookout. Later Laura tried to interest Elizabeth in the making of a headband of beadwork, but though she evidently liked to handle the bright-coloured beads, she would not try to do the work herself.

“I can’t. I can’t do things like that,” she said with gentle indifference, her eyes wandering off in search of Olga.

The next day, however, Laura came to Anne Wentworth, her eyes shining. “O Anne, what do you think?” she cried. “Olga had Elizabeth in wading this morning. Isn’t that fine?”

“Fine indeed—for a beginning. It shows what Olga might do with her if she would.”

“Yes, for she was so cross with her! I wondered that Elizabeth did not go away and leave her. No other girl in camp would let Olga speak to her as she speaks to that Poor Thing.”

“No, the others are not Poor Things, you see—that makes all the difference. But that Olga should take the trouble to make Elizabeth do anything is a big step in advance—for Olga.”

52“There is splendid material in Olga, Anne—I am sure of it,” Laura returned.

There was splendid persistence in her, anyhow. She had undertaken to overcome Elizabeth’s fear of the water, but it was a harder task than she had imagined. She did make the Poor Thing wade—clinging tightly to Olga’s fingers all the time—but further than that she could not lead her. Day after day Elizabeth would stand shivering and trembling in water up to her knees, her cheeks so white and her lips so blue that Olga dared not compel her to go further. Yet day after day Olga made her wade in that far at least; not once would she allow her to omit it.

One day she sat for a long time looking gravely at the Poor Thing, who flushed and paled nervously under that steady silent scrutiny. At last Olga said abruptly, “What do you like best, Elizabeth?”

“Like—best——” Elizabeth faltered uncertainly.

Olga frowned and repeated her question.

Elizabeth shook her head slowly. “I—I like Molly. And the other children—a little.”

“You mean your brothers and sisters?”

Elizabeth nodded.

“Which is Molly?”

“The littlest one. She’s four, and she’s real pretty,” Elizabeth declared proudly. “She’s prettier than Annie Pearson.”

“Yes, but what do you yourself like?” Olga persisted. “What would you like to have—pretty dresses, ribbons—what?”

“I—I never thought,” was the vague reply.

Again Olga’s brows met in a frown that made the 53Poor Thing shrink and tremble. She brought out her necklace and tossed it into the other girl’s lap.

“Think that’s pretty?” she asked.

“O yes!” Elizabeth breathed softly. She did not touch the necklace, but gazed admiringly at the bright-coloured beads as they lay in her lap.

“You can have one like it if you want,” Olga told her.

“O no! Who’d give me one?”

“Nobody. But you can get it for yourself. See here—I got all those blue beads by learning about the wild flowers that grow right around here, the weeds and stones and animals and birds. You can get as many in a few days. I got that green one for making a little bit of a basket, that—for making my washstand there out of a soap box—that, for trimming my hat. Every bead on that necklace is there because of some little thing I did or made—all things that you can do too.”

The Poor Thing shook her head. “O no,” she stammered in her weak gentle voice, “I can’t do anything. I—I ain’t like other girls.”

“You can be if you want to,” Olga flung out at her impatiently. “Say—what can you do? You can do something.”

“No—nothing.” The Poor Thing’s blue eyes filled slowly with big tears, and she looked through them beseechingly at the other. Olga drew a long exasperated breath. She wanted to take hold of the girl’s thin shoulders and shake the limpness out of her once for all.

“What did you do at home?” she demanded with harsh abruptness.

54“N—nothing,” Elizabeth answered with a miserable gulp.

“You did too! Of course you did something,” Olga flamed. “You didn’t sit and stare at Molly and the others all day the way you stare at me, did you? What did you do, I say?”

Elizabeth gave her a swift scared glance as she stammered, “I didn’t do anything but cook and sweep and wash and iron and take care of the children—truly I didn’t.”

Olga’s face brightened. “Good heavens—if you aren’t the limit!” she shrugged. Then she sprang up and got pencil and paper. “What can you cook?” she demanded, and proceeded to put Elizabeth through a rapid-fire examination on marketing, plain cooking, washing, ironing, sweeping, bed-making, and care of babies. At last she had found some things that even the Poor Thing could do. With flying fingers she scribbled down the girl’s answers. Finally she cried excitingly, “There! See what a goose you were to say you couldn’t do anything! Why, there are lots of girls here who couldn’t do half these things. Elizabeth Page, listen. You’ve got twelve orange beads like those,” she pointed to the necklace—“already, for a beginning. That’s more than I have of that colour. I don’t know anything about taking care of babies, nor half what you do about cooking and marketing.”

Elizabeth stared, her mouth half open, her eyes widened in incredulous wonder. “But—but,” she faltered, “I guess there’s some mistake. Just housework and things like that ain’t anything to get beads for—are they?”

55“They are that! I tell you Mrs. Royall will give you twelve honours and twelve yellow beads at the next Council Fire, and if you half try you can win some blue and brown and red ones too before that, and you’ve just got to do it. Do you understand?”

The other nodded, her eyes full of dumb misery. Then she began to whimper, “I—I—can’t ever do things like you and the rest do,” she moaned.

“Why not? You can walk, can’t you?”

“W—walk?”

“Yes—walk! Didn’t hurt you to walk to the village yesterday, did it?”

“No—but I couldn’t go—alone.”

“Who said anything about going alone? You’ll walk to Slabtown and back with me to-morrow.”

“O, I’d like that—with you,” said the Poor Thing, brightening.

Olga gave an impatient sniff. Sometimes she almost hated Elizabeth—almost but not quite.

“You’ll go with me to-morrow,” she declared, “but next day you’ll go with some other girl.”

Elizabeth shrank into herself, shaking her head.

Olga eyed her sternly. “Very well—if you won’t go with some other girl, you can’t go with me to-morrow,” she declared.

But the next day after breakfast the two set off for Slabtown. Halfway there, Elizabeth suddenly crumpled up and dropped in a limp heap by the roadside.

“What’s the matter?” Olga demanded, standing over her.

Elizabeth lifted tired eyes. “I don’t know. You walked so—fast,” she panted.

56“Fast!” echoed Olga scornfully; but she sat on a stone wall and waited until a little colour had crept back into the other girl’s thin cheeks, and went at a slower pace afterwards.

“There! Do that every day for a week and you’ll have one of your red beads,” was her comment when they were back at camp. “And now go lie in that hammock.”

When from the kitchen she brought a glass of milk and some crackers, she found Elizabeth sitting on the ground.

“Why didn’t you get into the hammock as I told you?” she demanded, and the Poor Thing answered vaguely that she “thought maybe they wouldn’t want” her to.

Olga poked the milk at her. “Drink it!” she ordered, “and eat those crackers,” and when Elizabeth had obeyed, added, “Now get into that hammock and lie there till dinner-time,” and meekly Elizabeth did so.

When, later in the day, some of the younger girls started a game of blindman’s buff, Olga seized Elizabeth’s hand. “Come,” she said, “we’re going to play too.”

“O, I can’t! I—I never did,” cried the Poor Thing, hanging back.

“I never did either, but I’m going to now and so are you. Come!” and Elizabeth yielded to the imperative command.

The other girls stared in amazement as the two joined them. It was little Bess Carroll who smiled a welcome as Louise Johnson cried out,

“Wonders will never cease--Olga Priest playing a game!”

57She spoke to Mary Hastings, who answered hastily, “Bless her heart—she’s doing it just to get that Poor Thing to play. Let’s take them right in, girls.”

The girls were quick to respond. Olga was the next one caught, and when she was blinded she couldn’t help catching Elizabeth, who stood still, never thinking of getting out of the way. Elizabeth didn’t want the handkerchief tied over her eyes, but she submitted meekly, at a look from Olga. Half a dozen girls flung themselves in her way, and the one on whom her limp grasp fell ignored the fact that Elizabeth could not name her, and gaily held up the handkerchief to be tied over her own eyes in turn. Nobody caught Olga again. She was as quick as a flash and as slippery as an eel. Elizabeth’s eyes followed her constantly, and a little glimmer of a smile touched her lips as Olga slipped safely out of reach of one catcher after another.

When she pulled Elizabeth out of the noisy merry circle, Olga glanced at the clock in the dining-room and made a swift calculation. “Three-quarters of an hour—blindman’s buff.”

“We’ve got to play at some game every day, Elizabeth,” she announced, with grim determination. She hated games, but Elizabeth must win her red beads and the red blood for which they stood. She had undertaken to make something out of this jellyfish of a girl and she did not mean to fail. That was all there was about it. So every day she led forth the reluctant Elizabeth and patiently stood over her while she blundered through a game of basket-ball, hockey, prisoner’s base, or whatever the girls were playing. But Elizabeth made small progress. Always she barely stumbled 58through her part, helped in every way by Olga and often by other girls who helped her for Olga’s sake.

It was Mary Hastings who broke out earnestly one day, looking after the two going down the road, “I say, girls, we’re just a lot of selfish pigs to leave that Poor Thing on Olga’s hands all the time. It must be misery to her to have Elizabeth hanging on to her as she does—a dead weight.”

“Right you are! I should think she’d hate the Poor Thing—I should. I should take her down to the dock some night and drown her,” said Louise Johnson with her inevitable giggle.

“I think Olga deserves all the honours there are for the way she endures that—jellyfish,” said Edith Rue.

“I never saw any one thaw out the way Olga has lately though. She really deigns to speak amiably now—sometimes,” Annie Pearson put in with a sniff.

“She ‘deigns’ to do anything under the sun that will help that Poor Thing to be a bit like other girls,” cried Mary. “Olga is splendid, girls! She makes me ashamed of myself twenty times a day. Do you realise what it means? She is trying to make that Poor Thing live. She just exists now. O, we must help her—we must—every single one of us!”

“But how, Molly? We’re willing enough to help, but we don’t know how. Elizabeth turns her back on every one of us except Olga—you know she does.”

“I know,” Mary admitted, “but if we really try we can find ways to help.”

When, compelled by Olga’s unyielding determination, the Poor Thing had taken a three-mile tramp 59every day for a week, she began to enjoy it, and did not object when another mile was added. She was always happy when she was with Olga, but at other times—when they were not walking—her content was marred by the consciousness that Olga was not really pleased with her because she could not do so many things that the others wanted her to do—like beadwork and basketwork, and above all, swimming. But Olga was pleased with her when she went willingly on these daily tramps.

The Poor Thing seemed to find something particularly attractive about the Slabtown settlement, and liked better to go in that direction than any other. She would often stop and watch the dirty half-naked babies playing in the bare yards; and as she watched them there would come into her face a look that Olga could not understand—Olga, who had never had a baby sister to love and cuddle.

One day when the two approached the little settlement, they saw half a dozen boys and girls walking along the top of a stone-wall that bordered the road. A baby girl—not yet three—was begging the others to help her up, but they refused.

“You can’t get up here, Polly John—you’re too little!” the boys shouted at her. But evidently Polly John had a will of her own, for she made such an outcry that at last her sister exclaimed, “We’ve got to take her up—she’ll yell till we do,” and to the baby she cried, “Now you hush up, Polly, an’ ketch hold o’ my hand.”

The baby held up her hand and with a jerk she was pulled to the top of the wall, but by no means did she “hush up.” She writhed and twisted and 60screamed, but there was a difference now—a note of pain and terror in the shrill cries.

“What ails her? What’s she yellin’ for now?” one boy demanded, and another shouted, “Take her down, Peggy. You get down with her.”

“I won’t, either!” Peggy retorted angrily, but she was sitting on the wall now, holding the baby half impatiently, half anxiously.

“Look at her arm. What makes her stick it out like that?” one boy questioned.

The big sister took hold of the small arm, but at her touch the baby’s cries redoubled, and a woman put her head out of a window and sharply demanded what they were doing to that child anyhow.

It was then that the Poor Thing suddenly darted across the road and caught the wailing child from the arms of her astonished sister.

“O, don’t touch her arm!” Elizabeth cried. “Don’t you see? It’s hurting her dreadfully. You slipped it out of joint when you pulled her up there.”

“I didn’t, either! Much you know about it!” the older girl flashed back, sticking out her tongue. But the fear in her eyes belied her impudence.

“Where’s her mother?” Elizabeth demanded.

“She ain’t got none,” chorused all the children.

Several women now came hurrying out to see what was the matter. One of them held out her arms to the child, but she hid her face on Elizabeth’s shoulder, and still kept up her frightened wailing.

“How d’ye know her arm’s out o’ joint?” one of the women demanded when Peggy had repeated what Elizabeth had said.

“I do know because I pulled my little sister’s arm 61out just that way once, lifting her over a crossing. O, I wish I knew how to slip it in again! It wouldn’t take a minute if we only knew how. Now we must get her to a doctor—quick. It is hurting her dreadfully, you know—that’s why she keeps crying so!”

“A doctor! Ain’t no doctor nearer’n East Bassett,” one woman said.

“East Bassett! Then we must take her there,” Elizabeth said to Olga, who for once stood by silent and helpless.

“We can get her there in twenty minutes—maybe fifteen if we walk fast,” she said.

“Then”—Elizabeth questioned the women—“can any of you take her there?”

The women exchanged glances. “It’s ’most dinner time—my man will be home,” said one. The others all had excuses; no one offered to take the child to East Bassett. No one really believed in the necessity. What did this white-faced slip of a girl know about children, anyhow?

“Then I’ll take her myself,” the Poor Thing declared. “I guess I can carry her that far.”

“An’ who’ll bring her back?” demanded the child’s sister gloomily.

“You must come with me and bring her back,” Elizabeth answered with decision. “Come quick! I tell you it’s hurting her awfully. Don’t you see how white she is?”

Peggy looked at the little face all white and drawn with pain, and surrendered.

“I’ll go,” she said meekly, and without more words, Elizabeth set off with the child in her arms. Olga followed in silence, and Peggy trailed along in the 62rear, but as she went she turned and shouted back to one of the boys, “Jimmy, you come along too with the wagon to bring her home in,” and presently a freckled-faced boy, with straw-coloured hair, had joined the procession. The wagon he drew was a soapbox fitted with a pair of wheels from a go-cart.

“Let me carry her, Elizabeth—she’s too heavy for you,” Olga said after a few minutes; but the child clung to Elizabeth, refusing to be transferred, and at the pressure of the little yellow head against her shoulder, Elizabeth smiled.

“I can carry her,” she said. “She’s not so very heavy. She makes me think of little Molly.”