Title: The Arena, Volume 4, No. 23, October, 1891

Author: Various

Editor: B. O. Flower

Release date: December 10, 2007 [eBook #23802]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Barbara Tozier, Bill Tozier, Richard J. Shiffer

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

| October, 1891 | |

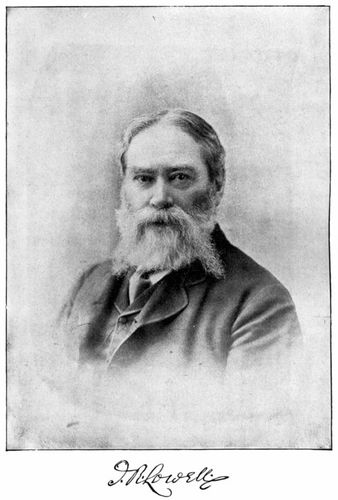

| James Russell Lowell | George Stewart, D. C. L., LL. D. |

| Healing Through Mind | Henry Wood |

| Mr. and Mrs. Herne | Hamlin Garland |

| Some Weak Spots in the French Republic | Theodore Stanton |

| Leaderless Mobs | H. C. Bradsby |

| Madame Blavatsky at Adyar | Moncure D. Conway |

| Emancipation by Nationalism | T. B. Wakeman |

| Recollections of Old Play-Bills | Charles H. Pattee |

| The Microscope from a Medical Point of View | Frederick Gaertner, A. M., M. D. |

| A Grain of Gold | Will Allen Dromgoole |

| Religious Intolerance To-day | Editorial |

| Social Conditions under Louis XV. | Editorial |

With loving breath of all the winds, his name

Is blown about the world; but to his friends

A sweeter secret hides behind his fame,

And love steals shyly through the loud acclaim

To murmur a God bless you! and there ends.

When Longfellow had reached his sixtieth year, James Russell Lowell, then in his splendid prime, sent him those lines as a birthday greeting. Lowell, since then, received in his turn many similar tributes of affection, but none that seemed to speak so promptly from the heart as those touching words of love to an old friend. To himself they might well have been applied in all truthfulness and sincerity. Of the famous group of New England singers, that gave strength and reality to American letters, but three names survived until the other day, when, perhaps the greatest of them all passed away. Whittier and Holmes remain, but Lowell, the younger of the three, and from whom so much was still expected, is no more to gladden, to delight, to enrich, and to instruct the age in which he occupied so eminent a place. Bryant was the first to go, and then Longfellow was called. Emerson followed soon after, and now it is Lowell’s hand which has dropped forever the pen. At first his illness did not cause much uneasiness, but those near him soon began to observe indications of the great change that was going on. At the last, dissolution was not slow in coming, and death relieved the 514patient of his sufferings in the early hours of Wednesday, August 12th. Practically, however, it was conceded that his life-work had been completed a few months ago, when his publishers presented the reading world with his writings in ten sumptuous volumes, six containing the prose works, and the other four the poems and satires. He was, with the single exception of Matthew Arnold, the foremost critic of his time. Everything he said was well said. The jewels abounded on all sides. His adroitness, his fancy, his insight, his perfect good-humor, and his rare scholarship and delicate art, emphasize themselves on every page of his books. His political and literary addresses were models of what those things should be. They were often graceful and epigrammatic, but always sterling in their value and full of thought. Long ago he established his claim to the title of poet, and as the years went by, his muse grew stronger, richer, fresher, and more original. As an English critic, writing pleasantly of him and his work, in the London Spectator said lately: “His books are delightful reading, with no monotony except a monotony of brilliance which an occasional lapse into dulness would almost diversify.”

James Russell Lowell was descended from a notable ancestry. His father was a clergyman, the pastor of the West Church in Boston. His mother was a woman of fine mind, a great lover of poetry, and mistress of several languages. From her, undoubtedly, the gifted son inherited his taste for belles-lettres and foreign tongues. He was born at Cambridge, Mass., on the 22d of February, 1819, and named after his father’s maternal grandfather, Judge James Russell. After spending a few years at the town school, under Mr. William Wells, a famous teacher in his day, he entered Harvard University, and in 1838 was graduated. He wrote the class poem of the year, and took up the study of law. But the latter he soon relinquished for letters. His first book was a small collection of verse entitled “A Year’s Life.” It gave indication of what followed. There were traces of real poetry in the volume, and none who read it doubted the poet’s future success in his courtship of the muse. In 1843 he tried magazine publishing, his partner in the venture being Robert Carter. Three numbers only of The Pioneer, a Literary and Critical515 Magazine, were published, and though it contained contributions by Hawthorne, Lowell, Poe, Dwight, Neal, Mrs. Browning, and Parsons, it failed to make its way, and the young editor prudently withdrew it. In the next year he published the “Legend of Brittany, Miscellaneous Poems and Sonnets.” A marked advance in his art was immediately noticed. His lyrical strength, his passion, his terse vocabulary, his exquisite fancy and tenderness illumed every page, giving it dignity and color. The legend reminded the reader of an Old World poem, and “Prometheus” too, might have been written abroad. “Rhœcus” was cast in the Greek mold, and told the story, very beautifully and very artistically, of the wood-nymph and the bee. But there were other poems in the collection, such as “To Perdita Singing,” “The Heritage,” and “The Forlorn,” which at once caught the ear of lovers of true melody. A volume of prose essays succeeded this book. It was entitled “Conversations on some of the Old Poets,” and when Mr. Lowell became Mr. Longfellow’s successor in the chair of modern languages and belles-lettres at Harvard, much of this material was used in his lectures to the students. But later on, we will concern ourselves more directly with the author’s prose.

In December, 1844, Mr. Lowell espoused Miss Maria White, of Watertown. She was a lady of gentle character, and a poet of singular grace. The marriage was a most happy one, and it was to her that many of the love poems of Lowell were inscribed. Once he wrote:—

“A lily thou wast when I saw thee first,

A lily-bud not opened quite,

That hourly grew more pure and white,

By morning, and noon-tide, and evening nursed:

In all of Nature thou had’st thy share;

Thou wast waited on

By the wind and sun;

The rain and the dew for thee took care;

It seemed thou never could’st be more fair.”

She died on the 27th of October, 1853, the day that a child was born to Mr. Longfellow. The latter’s touching and perfect poem, “The Two Angels,” refers to this death and birth:—

“‘T was at thy door, O friend! and not at mine,

The angel with the amaranthine wreath,

Pausing, descended, and with voice divine,

Whispered a word that had a sound like death.

Then fell upon the house a sudden gloom,

A shadow on those features fair and thin;

And softly, from that hushed and darkened room,

Two angels issued, where but one went in.

All is of God! If He but wave His hand,

The mists collect, the rain falls thick and loud,

Till with a smile of light on sea and land,

Lo! He looks back from the departing cloud.”

A privately printed volume of Mrs. Lowell’s poems appeared a year or two after her death. Mr. Lowell’s second wife was Miss Frances Dunlap, of Portland, Maine, whom he married in September, 1857. She died in February, 1885.

Mr. Lowell was ever pronounced in his hatred of wrong, and naturally enough he was found on the side of Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and Whittier, in their great battle against that huge blot on civilization, slavery in America. He spoke and wrote in behalf of the abolitionists at a time when the anti-slavery men were openly despised as heartily in the North as they were feared and detested in the South. He wrote with a pen which never faltered, and satire, irony, and fierce invective accomplished their work with a will, and moved many a heart, almost despairing, to renewed energy.

“The Vision of Sir Launfal” was published in 1848, and it will be read as long as men and women admire tales of chivalry and the stirring stories of King Arthur’s court. Tennyson’s “Idyls” will keep his fame alive, and Lowell’s Sir Launfal, which tells of the search for the Holy Grail, the cup from which Christ drank when he partook of the last supper with his disciples, will also have a place among the best of the Arthurian legends. It is said that Mr. Lowell wrote this strong poem in forty-eight hours, during which he hardly slept or ate. Stedman calls it “a landscape poem,” a term amply justified. It contains many quotable extracts, such as, “And what is so rare as a day in June,” “Down swept the chill wind from the mountain peak, from the snow five thousand summers old,” and “Earth gets its price for what earth gives us.” We are constantly meeting these in the magazines and in the newspapers. The vision did much to bring about a larger recognition of the author’s powers as a poet of the first order. He had to wait some time to gain this, and in that respect he resembled Robert517 Browning, at first so obscure, at last compelling approval from all.

The field of American literature, as it existed in 1848, was surveyed by Lowell in his happiest manner, as a satirist, in that clever production, by a wonderful Quiz, A Fable for Critics, “Set forth in October, the 31st day, in the year ‘48, G. P. Putnam, Broadway.” For some time the authorship remained a secret, though there were many shrewd guesses as to the paternity of the biting shafts of wit and delicately baited hooks. It was written mainly for the author’s own amusement, and with no thought of publication. Daily instalments of the poem were sent off, as soon as written, to a friend of the poet, Mr. Charles F. Briggs, of New York, who found the lines so irresistibly good, that he begged permission to hand them over to Putnam’s for publication. This, however, Mr. Lowell declined to do, until he found that the repeated urging of his friend would not be stayed. Then he consented to anonymous publication. The secret was kept, until, as the author himself tells us, “several persons laid claim to its authorship.” No poem has been oftener quoted than the fable. It is full of audacious things. The authors of the day, and their peculiar characteristics (Lowell himself not being spared in the least), are held up to admiring audiences with all their sins and foibles exposed to the public gaze. It was intended to have “a sting in his tale,” this “frail, slender thing, rhymey-winged,” and it had it decidedly. Some of the authors lampooned took the matter up, in downright sober earnest, and objected to the seat in the pillory which they were forced to occupy unwillingly. But they forgave the satirist, as the days went by, and they realized that, after all, the fun was harmless, nobody was hurt actually, and all were treated alike by the ready knife of the fabler. But what could they say to a man who thus wrote of himself?—

“There is Lowell, who’s striving Parnassus to climb

With a whole bale of isms tied together with rhyme,

He might get on alone, spite of brambles and boulders,

But he can’t with that bundle he has on his shoulders.

The top of the hill he will ne’er come nigh reaching

Till he learns the distinction ‘twixt singing and preaching;

His lyre has some chords that would ring pretty well,

But he’d rather by half make a drum of the shell,

And rattle away till he’s old as Methusalem,

At the head of a march to the last new Jerusalem.”

Apart from the humorous aspect of the fable, there is, certainly, a good deal of sound criticism in the piece. It may be brief, it may be inadequate, it may be blunt, but for all that it is truthful, and decidedly just, as far as it goes. Bryant, who was called cold, took umbrage at the portrait drawn of him. But his verse has all the cold glitter of the Greek bards, despite the fact that he is America’s greatest poet of nature, and some of his songs are both sympathetic and sweet, such as the “Lines to a Water-fowl,” “The Flood of Years,” “The Little People of the Snow,” and “Thanatopsis.”

But now we come to the book which gave Mr. Lowell his strongest place in American letters, and revealed his remarkable powers as a humorist, satirist, and thinker. We have him in this work, at his very best. The vein had never been thoroughly worked before. The Yankee of Haliburton appeared ten years earlier than the creations of Lowell. But Sam Slick was a totally different person from Hosea Biglow and Birdofredum Sawin. Slick was a very interesting man, and he has his place in fiction. His sayings and doings are still read, and his wise saws continue to be pondered over. But the Biglow type seems to our mind, more complete, more rounded, more perfect, more true, indeed, to nature. The art is well proportioned all through, and the author justifies Bungay’s assumption, that he had attained the rank of Butler, whose satire heads the list of all such productions. Butler, however, Lowell really surpassed. The movement is swift, and there is an individuality about the whole performance, which stamps it undeniably as a masterpiece. The down-east dialect is managed with consummate skill, the character-drawing is superlatively fine, and the sentiments uttered, ringing like a bell, carry conviction. The invasion of Mexico was a distasteful thing to many people because it was felt that that war was dishonorable, and undertaken solely for the benefit of the slaveholder, who was looking out for new premises, where he might ply his calling, and continue the awful trade of bondage, and his dealings in flesh and blood. Mr. Lowell’s heart was steeled against that expedition, and the first series of his Biglow papers, introduced to the world by the Reverend Homer Wilbur, showed how deeply earnest he was, and how terribly rigorous he could be, when the scalpel had to be used. The first knowledge that the 519reading world had of the curious, ingenuous, and quaint Hosea, was the communication which his father, Ezekiel Biglow, sent to the Boston Courier, covering a poem in the Yankee dialect, by the hand of the young down-easter. It at once commanded notice. The idea was so new, the homely truths were so well put, the language in print was so unusual, and the “hits” were so well aimed, that the critics were baffled. The public took hold immediately, and it soon spread that a strong and bold pen was helping the reformers in their unpopular struggle. The blows were struck relentlessly, but men and women laughed through their indignation. There were some who rebelled at the coarseness of the satire, but all recognized that the author, whoever he might be, was a scholar, a man of thought, and a genuine philanthropist, who could not be put down. Volunteers were wanted, and Boston was asked to raise her quota. But Hosea Biglow, in his charmingly scornful way said:—

“Thrash away, you’ll hev to rattle

On them kittle-drums o’ yourn,—

‘Taint a knowin’ kind o’ cattle

Thet is ketched with mouldy corn.

Put in stiff, you fifer feller,

Let folks see how spry you be,—

Guess you’ll toot till you are yaller

‘Fore you git ahold o’ me!”

The parson adds a note, sprinkled with Latin and Greek sentences, as is his wont. The letters from the first page to the last, in the collected papers, are amazingly clever. The reverend gentleman who edits the series is a type himself, full of pedantic and pedagogic learning, anxious always to show off his knowledge of the classics, and solemn and serious ever as a veritable owl. His notes and introductions, and scrappy Latin and Greek, are among the most admirable things in the book. Their humor is delicious, and the mock criticisms and opinions of the press, offered by Wilbur on the work of his young friend, and his magnificent seriousness, which constantly shows itself, give a zest to the performance, which lingers long on the mind. The third letter contains the often-quoted poem, “What Mr. Robinson Thinks.”

“Gineral C. is a dreffle smart man:

He’s ben on all sides that give place or pelf;

But consistency still wuz a part of his plan,—

He’s ben true to one party,—an’ thet is himself:—

So John P.

Robinson, he

Sez he shall vote for Gineral C.

. . . . . . . . .

Parson Wilbur sez he never heerd in his life

That th’ Apostles rigged out in their swaller tail coats,

An’ marched round in front of a drum an’ a fife,

To get some on ‘em office, an’ some on ‘em votes;

But John P.

Robinson, he

Says they didn’t know everything down in Judee.”

Despite the sometimes harsh criticism which the Biglow papers evoked, Mr. Lowell kept on sending them out at regular intervals, knowing that every blow struck was a blow in the cause of right, and every attack was an attack on the meannesses of the time. The flexible dialect seemed to add honesty to the poet’s invective. The satire was oftentimes savage enough, but the vehicle by which it was conveyed, carried it off. There was danger that Lowell might exceed his limit, but the excess so nearly reached, never came. The papers aroused the whole country, said Whittier, and did as much to free the slave, almost, as Grant’s guns. In one of the numbers, Mr. Lowell produced, quite by accident, as it were, his celebrated poem of “The Courtin’.” This was in the second series, begun in the Atlantic Monthly, of which he was, in 1857, one of the founders, and editor. This series was written during the time of the American Civil War, and the object was to ridicule the revolt of the Southern States, and show up the demon of secession in its true colors. Birdofredum Sawin, now a secessionist, writes to Hosea Biglow, and the poem is, of course, introduced as usual, by the parson. The humor is more grim and sardonic, for the war was a stern reality, and Mr. Lowell felt the need of making his work tell with all the force that he could put into it. In response to a request for enough “copy” to fill out a certain editorial page, Lowell wrote rapidly down the verses which became, at a bound, so popular. He added, from time to time, other lines. This is the story of the Yankee courtship of Zekle and Huldy:—

“The very room, coz she was in,

Seemed warm f’om floor to ceilin’,

An’ she looked full ez rosy agin

Ez the apples she was peelin’.

. . . . . .

He kin’ o’ l’itered on the mat,

Some doubtfle o’ the sekle,

His heart kep’ goin’ pity-pat,

But hern went pity Zekle.

An’ yit she gin her chair a jerk

As though she wished him furder,

An’ on her apples kep’ to work,

Parin’ away like murder.

‘You want to see my pa, I s’pose?’

‘Wall,—no—I come dasignin’—’

‘To see my ma? She’s sprinklin’ clo’s

Agin to-morrer’s i’nin.’

To say why gals acts so or so,

Or don’t ‘ould be prosumin’,

Mebby to mean yes an’ say no

Comes natural to women.

He stood a spell on one foot fust,

Then stood a spell on t’other,

An’ on which one he felt the wust

He couldn’t ha’ told ye nuther.

Says he, ‘I’d better call agin;’

Says she, ‘Think likely, mister;’

Thet last word pricked him like a pin,

An’—wall, he up an’ kist her.

When ma bimeby upon ‘em slips,

Huldy sot pale ez ashes,

All kin’ o’ smily roun’ the lips

An’ teary roun’ the lashes.

For she was jes’ the quiet kind

Whose natures never vary,

Like streams that keep a summer wind

Snow-hid in Janooary.

The blood clost roun’ her heart felt glued

Too tight for all expressin’,

Till mother see how matters stood,

An’ gin ‘em both her blessin’.

Then her red come back like the tide

Down to the Bay o’ Fundy,

An’ all I know is they war cried

In meetin’ come nex’ Sunday.”

During the war, Great Britain sided principally with the South. This the North resented, and the Trent affair only 522added fuel to the flame. It was in one of the Biglow papers that Mr. Lowell spoke to England, voicing the sentiments and feelings of the Northern people. That poem was called “Jonathan to John,” and it made a great impression on two continents. It was full of the keenest irony, and though bitter, there was enough common sense in it, to make men read it, and think. It closes thus patriotically:—

“Shall it be love, or hate, John?

It’s you thet’s to decide;

Ain’t your bonds held by Fate, John,

Like all the world’s beside?’

Ole Uncle S. sez he, ‘I guess

Wise men forgive,’ sez he,

‘But not forgit; an’ some time yit

Thet truth may strike J. B.,

Ez wal ez you an’ me!’

‘God means to make this land, John,

Clear, then, from sea to sea.

Believe an’ understand, John,

The wuth o’ bein’ free.’

Ole Uncle S. sez he, ‘I guess,

God’s price is high,’ sez he;

‘But nothin’ else than wut He sells

Wears long, an’ thet J. B.

May larn, like you an’ me!’”

The work concludes with notes, a glossary of Yankee terms, and a copious index. The chapter which tells of the death of Parson Wilbur is one of the most exquisite things that Lowell has done in prose. The reader who has followed the fortunes of the Reverend Homer, is profoundly touched by the reflection that he will see him no more. He had grown to be a real personage, and long association with him had made him a friend. On this point, Mr. Underwood relates an incident, which is worth quoting here:—

“The thought of grief for the death of an imaginary person is not quite so absurd as it might appear. One day, while the great novel of ‘The Newcomes’ was in course of publication, Lowell, who was then in London, met Thackeray on the street. The novelist was serious in manner, and his looks and voice told of weariness and affliction. He saw the kindly inquiry in the poet’s eyes, and said, ‘Come into Evan’s and I’ll tell you all about it. I have killed the Colonel.’”

So they walked in and took a table in a remote corner, and then Thackeray, drawing the fresh sheets of manuscript 523from his breast pocket, read through that exquisitely touching chapter which records the death of Colonel Newcome. When he came to the final Adsum, the tears which had been swelling his lids for some time trickled down upon his face, and the last word was almost an inarticulate sob.

The volume “Under the Willows,” which contains the poems written at intervals during ten or a dozen years, includes such well-remembered favorites as “The First Snowfall,” for an autograph “A Winter Evening Hymn to My Fire,” “The Dead House” (wonderfully beautiful it is), “The Darkened Mind,” “In the Twilight,” and the vigorous “Villa Franca” so full of moral strength. It appeared in 1869. Mr. Lowell’s pen was always busy about this time and earlier. He was a regular contributor to the Atlantic in prose and verse. He was lecturing to his students and helping Longfellow with his matchless translation of Dante, besides having other irons in the fire.

It is admitted that the greatest poem of the Civil War was, by all odds, Mr. Lowell’s noble commemoration ode. In that blood-red struggle several of his kinsmen were slain, among them Gen. C. R. Lowell, Lieut. I. I. Lowell, and Lieutenant Putnam, all nephews. His ode which was written in 1865, and recited July 21, at the Harvard commemoration services, is dedicated “To the ever sweet and shining memory of the ninety-three sons of Harvard College, who have died for their country in the war of nationality.” It is, in every way, a great effort, and the historic occasion which called it forth will not be forgotten. The audience assembled to listen to it was very large. No hall could hold the company, and so the ringing words were spoken in the open air. Meade, the hero of Gettysburg, stood at one side, and near him were Story, poet and sculptor, fresh from Rome, and General Devens, afterwards judge, and fellows of Lowell’s own class at college. The most distinguished people of the Commonwealth lent their presence to the scene. There was a hushed silence while Lowell spoke, and when he uttered the last grand words of his ode, every heart was full, and the old wounds bled afresh, for hardly one of that vast throng had escaped the badge of mourning, for a son, or brother, or father, lost in that war.

“Bow down, dear land, for thou hast found release!

Thy God, in these distempered days,

Hath taught thee the sure wisdom of His ways,

And through thine enemies hath wrought thy peace!

Bow down in prayer and praise!

No poorest in thy borders but may now

Lift to the juster skies a man’s enfranchised brow.

O Beautiful! My Country! ours once more!

Smoothing thy gold of war-disheveled hair

O’er such sweet brows as never other wore,

And letting thy set lips,

Freed from wrath’s pale eclipse,

The rosy edges of their smile lay bare.

What words divine of lover or of poet

Could tell our love and make thee know it,

Among the nations bright beyond compare?

What were our lives without thee?

What all our lives to save thee?

We reck not what we gave thee;

We will not dare to doubt thee,

But ask whatever else, and we will dare.

“The Cathedral,” dedicated most felicitously to the late James T. Fields, the author publisher, written in 1869, was published early in the following year in the Atlantic Monthly, and immediately won the applause of the more thoughtful reader. It is a poem of great grandeur, suggestive in the highest degree and rich in description and literary finish. Three memorial odes, one read at the one hundredth anniversary of the fight at Concord Bridge, one under the old elm, and one for the Fourth of July, 1876, followed. The Concord ode appears to be the more striking and brilliant of the three, but all are satisfactory specimens, measured by the standard which governs the lyric.

“Heartsease and Rue,” is the graceful title of Mr. Lowell’s last volume of verse. A good many of his personal poems are included in the collection, such as his charming epistle to George William Curtis, the elegant author of “Prue and I,” one of the sweetest books ever written, inscribed to Mrs. Henry W. Longfellow, in memory of the happy hours at our castles in Spain; the magnificent apostrophe to Agassiz; the birthday offering to Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes; the lines to Whittier on his seventy-fifth birthday; the verses on receiving a copy of Mr. Austin Dobson’s “Old World Idyls,” and Fitz Adam’s story, playful, humorous, and idyllic.

In his young days, Mr. Lowell wrote much for the newspapers and serials. To the Dial, the organ of the transcendentalists, he contributed frequently, and his poems and prose will be found scattered through the pages of The Democratic Review, The North American Review, of which he ultimately became editor, The Massachusetts Quarterly Review, and the Boston Courier. His prose was well received by scholars. It is terse and strong, and whatever position history may assign to him as a poet there can never be any question about his place among the ablest essayists of his century. “Fireside Travels,” the first of the brilliant series of prose works that we have, attract by their singular grace and graciousness. The picture of Cambridge thirty years ago, is full of charming reminiscences that must be very dear to Cambridge men and women. “The Moosehead Journal,” and “Leaves from the Journal in Italy, Happily Turned,” are rich in local color. “Among My Books,” and “My Study Windows,” the addresses on literary and political topics, and the really able paper on Democracy, which proved a formidable answer to his critics, fill out the list of Mr. Lowell’s prose contributions. The literary essays are especially well done. Keats tinged his poetry when he was quite a young man. He never lost taste of Endymion or the Grecian urn, and his estimate of the poet, whose “name was writ in water,” is in excellent form and full of sympathy. Wordsworth, too, he read and re-read with fresh delight, and it is interesting to compare his views of the lake poet with those of Matthew Arnold. The older poets, such as Chaucer, Shakespeare, Spenser, Milton, Dryden, and Pope in English, and Dante in Italian, find in Mr. Lowell a penetrating and helpful critic. His analyses are made with rare skill and nice discrimination. He is never hasty in giving expression to his opinion, and every view that he gives utterance to, exhibits the process by which it reached its development. The thought grows under his hand, apparently. The paper on Pope, with whose writings he was familiar at an early age, is a most valuable one, being especially rich in allusion and in quality. He finds something new to say about the bard of Avon, and says it in a way which emphasizes its originality. Indeed, every essay is a strong presentation of what Lowell had in his mind at the time. He is not content to confine his 526observation to the name before him. He enlarges always the scope of his paper, and runs afield, picking up here and there citations, and illustrating his points, by copious drafts on literature, history, scenery, and episode. He was well equipped for his task, and his wealth of knowledge, his fine scholarly taste, his remarkable grasp of everything that he undertook, his extensive reading, all within call, added to a captivating style, imparted to his writings the tone which no other essayist contemporary with him, save Matthew Arnold, was able to achieve. Thoreau and Emerson are adequately treated, and the library of old authors is a capital digest, which all may read with profit. The paper on Carlyle, which is more than a mere review of the old historian’s “Frederick the Great,” is a noble bit of writing, sympathetic in touch, and striking as a portrait. It was written in 1866. And then there are papers in the volumes on Lessing, Swinburne’s Tragedies, Rousseau, and the Sentimentalists, and Josiah Quincy, which bring out Mr. Lowell’s critical acumen even stronger. Every one who has read anything during the last fifteen years or so, must remember that bright Atlantic essay on “A Certain Condescension in Foreigners.” It is Mr. Lowell’s serenest vein, hitting right and left skilful blows, and asserting constantly his lofty Americanism. The essay was needed. A lesson had to be given, and no better hands could have imparted it. Mr. Lowell was a master of form in literary composition,—that is in his prose, for he has been caught napping, occasionally, in his poetry,—and his difficulty was slight in choosing his words.

As a speaker he was successful. His addresses before noted gatherings in Britain and elsewhere are highly artistic. In Westminster Abbey he pronounced two, one on Dean Stanley, and the other on Coleridge, which, though brief, could scarcely be excelled, so perfect, so admirable, so dignified are they. The same may be said of the addresses on General Garfield, Fielding, Wordsworth, and Don Quixote. Mr. Lowell on such occasions always acquitted himself gracefully. He had few gestures, his voice was sweet, and the beauty of his language, his geniality, and courteous manner drew every one towards him. He was a great student, and preacher, and teacher of reform. He was in favor of the copyright law, and did his utmost to bring it 527about. He worked hard to secure tariff reform, and a pet idea of his was the reformation of the American civil service system. On all these subjects he spoke and wrote to the people with sincerity and earnestness. When aroused he could be eloquent, and even in later life, sometimes, some of the fire of the early days when he fought the slaveholders and the oppressors, would burst out with its old time energy. He was ever outspoken and fearless, regardless, apparently, of consequences, so long as his cause was just.

As professor of belles-lettres at Harvard University, he had ample opportunity for cultivating his literary studies, and though he continued to take a lively interest always in the political changes and upheavals constantly going on about him, he never applied for office. In politics he was a Republican. His party offered him the mission to Russia, but he declined the honor. During the Hayes administration, however, when his old classmate, General Devens, had a seat in the Cabinet, the government was more successful with him. He was tendered the post of Minister to Spain. This was in 1877, and he accepted it, somewhat half-heartedly, to be sure, for he had misgivings about leaving his lovely home at Elmwood, the house he was born in, the pride and glory of his life, the locale of many of his poems, the historic relic of royalist days. And then again, he did not care to leave the then unbroken circle of friends, for Dr. Holmes, John Holmes, Agassiz, Longfellow, Norton, Fields, John Bartlett, Whipple, Hale, James Freeman Clarke, and others of the famous Saturday club, he saw almost every day. And then, yet again, there was the whist club, how could he leave that? But he was overcome, and he went to Spain, and began, among the grandees and dons, his diplomatic career. His fame had preceded him, and he knew the language and literature of Cervantes well. It was not long before he became the friend of all with whom he came into contact. But no great diplomatic work engaged his attention, for there was none to do. The Queen Mercedes died, during his term, much beloved, and Mr. Lowell wrote in her memory one of his most chaste and beautiful sonnets:—

“Hers all that earth could promise or bestow,—

Youth, Beauty, Love, a crown, the beckoning years,

Lids never wet, unless with joyous tears,

A life remote from every sordid woe,

And by a nation’s swelled to lordlier flow.

What lurking-place, thought we, for doubts or fears,

When, the day’s swan, she swam along the cheers

Of the Acalá, five happy months ago?

The guns were shouting Io Hymen then

That, on her birthday, now denounce her doom;

The same white steeds that tossed their scorn of men

To-day as proudly drag her to the tomb.

Grim jest of fate! yet who dare call it blind,

Knowing what life is, what our humankind?”

In 1880, he was transferred to London, as “his excellency, the ambassador of American literature to the court of Shakespeare,” as a writer in the Spectator deliciously put it. He had a good field to work in, but, as the duties were light, he had ample time on his hands. He went about everywhere, the idol of all, the most engaging of men. Naturally, his tastes led him among scholars who in their turn made much of him. He was asked frequently to speak or deliver addresses and he always responded with tact. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge conferred on him their highest honors and the ancient Scottish University of Saint Andrew elected him rector,—a rare compliment, Emerson only being the other citizen of the United States so marked out for academic distinction. Some of his compatriots hinted that his English life was making him un-American. Others more openly asserted that the United States minister was fast losing the republic feelings which he took from America, and was becoming a British Conservative. The reply to those innuendoes and charges will be found in his spirited address on Democracy, which proves undeniably his sturdy faith in American institutions, American principles, and American manhood. Mr. Lowell maintained to the letter the political and national views which had long guided his career. His admirable temper and agreeable manner won the hearts of the people, but no effort was made to win him away from his allegiance, nor would he have permitted it had it been tried. In addition to being a great man and a well-informed statesman, he was a gentleman of culture and refinement. His gentleness and amiability may have been misconstrued by some, but be that as it may, the fact remains, he never showed weakness in the discharge of his diplomatic duties. He represented the United States in the fullest sense of the term. In 1885, he returned to America, Mr. E. J. Phelps taking his place, under President Cleveland. Though a Republican, Mr.529 Lowell differed from his party on the presidential candidate question. He favored the election of the Democrat nominee. Had he been in America during the campaign, he would have been found with Mr. George William Curtis, and his friends, opposing the return of Mr. Blaine. From 1885 to the date of his death, he added little to the volume of his literary work. He spent part of his time in England, and part in the United States. A poem, a brief paper, or an address or two, came from his pen, at irregular intervals. He edited a complete edition of his writings in ten volumes, and left behind him an unfinished biography of Hawthorne, which he was preparing for the American Men of Letters Series.

Truth may be considered as a rounded unit. Truths have various and unequal values, but each has its peculiar place, and if it be missing or distorted, the loss is not only local but general. Unity is made up of variety, and therein is completeness. Any honest search after truth is profitable, for thereby is made manifest the Kingdom of the Real.

During the fifteen years just past, but more especially within the last third of that period, a widespread interest has been developed in the question: Can disease be healed through mental treatment? If so, under what conditions and subject to what limitations? Has mental healing a philosophical and scientific basis, or is it variously composed of quackery, superstition, and assumption? In the simplest terms, how much truth does it contain? Any candid inquirer will admit that even if a minimum of its claims can be established, the world needs it. If it can be of service in lessening or mitigating the appalling aggregation of human suffering, disease, and woe, it should receive not only recognition, but a cordial welcome.

At the outset, it is proper to state that I have no professional nor pecuniary interest in any method of healing. The evolution of truth is my only object. To this end, critical and impartial investigation is necessary. While a personal experience of great practical benefit first aroused my interest in the subject, I have cultivated conservatism and incredulity in forming opinions, which are made up from a careful investigation of its literature, its philosophy, and its practical demonstrations.

The first point noticeable is the peculiar attitude of popular sentiment toward this movement. The unreasonable prejudice which has been displayed, and the flippant condemnation that it has generally received in advance of any investigation, illy befit the boasted impartiality and liberality of the closing decade of the nineteenth 531century. When the “Fatherhood of God” and the “Brotherhood of Man” are so much on men’s lips, and when the spirit of altruism is supposed to be at the floodtide, here is what claims to be the essential quality of them all denied even a hearing. The testimony of hundreds of clergymen, philanthropists, Christians, and humanitarians, is classed as “delusion,” and the experience of thousands who have received demonstrations in their own persons [information of which is accessible to any candid investigator], is passed by as an idle tale. It furnishes material for satire to the writer for the religious weekly, and a prolific butt for jokes to the paragrapher of the daily journal. The news of its failures is spread broadcast in bold head-lines by the sensational press. The fact that other kinds of treatment denominated “regular” also fail, seems never to be thought of. The mental healer, regardless of his success, is looked upon as an enthusiast, or worse, and even the citizen who modestly accepts the theory of possible mind-healing, is regarded as credulous and visionary by those who pride themselves upon their practicality. Why does this prejudice exist, when advancement in physical science uniformly meets with a friendly reception?

Perhaps the most important reason why “there is no room in the inn” for truth of the higher realm, is the prevailing materialism. Our western civilization prides itself upon its practicality; but externality would better define it. We forget that immaterial forces rule not only the invisible but the visible universe. Things to look real to us must be cognizant to the physical senses. Matter, whether in the vegetable, animal, or human organism, is moulded, shaped, and its quality determined by unseen forces back of and higher than itself.

We rely upon the drug, because we can feel, taste, see, and smell it. We are color-blind to invisible potency of a higher order, and practically conclude that it is nonexistent.

One reason for the prevailing adverse prejudice is that this new thought disturbs the foundation-stones of existing and time-honored systems and creeds. The literalism and externality of formulated theology are rebuked by the simplicity of the spiritual and internal forces which are here brought to light. The barrenness of intellectual scholasticism 532is in sharp contrast with the overflowing love and simple transparency which reveal the image of God in every man, and as an incidental result, possible health and harmony.

History ever repeats itself in the uniform suspicion with which advanced thought has been received by existing institutions. It seems difficult to learn the lesson, that the human apprehension of truth is ever expanding, while creeds are but “arrested developments, frozen into fixed forms.” As might be inferred, the clergy and the religious press, as a rule, are distrustful of this advance, and see little that is good in it. It is fair to admit that this disposition is often due more to misunderstanding, than to intentional injustice.

Another cause for its unwelcome reception is that it distrusts the dominant medical systems. All honor to the multitude of noble and brave men who from the old standpoint have battled with disease, and who have ever been on the alert to utilize every possible balm, in order to restore disordered humanity. But systems are tenacious of life in proportion as they are hoary with age. They mould men to their own shape; to break with them is difficult: tradition, pride, professional honor, and loyalty, and often social and pecuniary status, are all like strong cords, which bind even great men to their conventional grooves.

A further ground for the general unbelief is found in the peculiarities of the apostles and exponents of the new departure. A division into schools and cliques, the out-cropping of personality, exclusiveness, and internal criticism, statements of doctrine in forms likely to be misunderstood, and a technical phraseology have, in a measure, prevented a free and full understanding of principles, which are really simple and transparent.

Popular distrust is also awakened by the fact that, as a rule, mental healers have not regularly studied pathology, nor even anatomy. But it will be seen that if the principle of mental causation for disease is once admitted, mentality rather than physiology should furnish the field for operations. In order to heal, the mind of the patient must be brought into unison with that of the practitioner, and therefore, the latter must wash his own mind clean of spectres and even of studies of disease, and fill it to overflowing with ideals of health and harmony.

Another reason for misapprehension is the fact that mind healing is not demonstrable by argument. It is not intellectually apprehended. It concerns the inner man and can only be grasped by the deeper vision of intuitional and spiritual sense. It is like a cyclorama, the beauty of which is all inside. An outside view is no view at all.

Is there a necessity for some radical reinforcement to conventional instrumentalities to aid us in our warfare with human ills? Is it desirable to find some new vantage ground, and some more effective weapons? There can be but one answer. While surgery has been making rapid strides toward the position of an exact science, confidence in materia medica is on the wane. The surgeon is only a marvellously skilful mechanic who adjusts the parts, and then the divine, recuperative forces vitalize and complete his work. He only makes the figures, while the principle solves the problem. The adaptability of drugs to heal disease is becoming a matter of doubt, even among many who have not yet studied deeper causation. Materia medica lacks the exact elements of a science. The just preponderance for good or ill of any drug upon the human system is an unsolved problem, and will so remain. The fact that a fresh remedy seems to work well while it is much talked about, and then gradually appears to lose its efficacy, suggests that it is the atmosphere of general belief in the medicine, and not the medicine itself that accomplishes the visible result. It is well known that bread pills sometimes prove to be a powerful cathartic, even from individual belief; but general belief would be necessary in order to make them always reliable. General beliefs often have a very slight original basis, but gradually grow until their cumulative power is enormous. If scientific, the same remedies once adopted should remain; but instead, there is a continual transition. Fashions and fads are not significant of exact science. Elixirs of life, lymphs, and other specifics have their short run, and then join the endless procession to the rear. Many lives are sacrificed in experiments, but no criticism is made because the treatment is administered by those who are within the limits of the “regular” profession. After centuries of professional research, in order to perfect the “art of healing,” diseases have steadily grown more subtle and numerous. Combinations, distillations, extracts, and decoctions of almost every known material substance have 534been experimented with, in order to discover their true bearing upon that ever-receding ideal, the banishment of disease. If materia medica were a science, disease should be in a process of extermination. It does not look as if this were expected, for doctors with diplomas are multiplying in a much greater ratio than the population, and already we have more than three times the proportionate quota of Germany. As our material civilization recedes from nature and grows more artificial, diseases, doctors, and remedies multiply. What can be more beautiful and perfect than the human eye; yet how commonly this organ requires artificial aid. The human senses are losing their tone, and if present tendencies continue, it seems almost as if the future man would be not only bald, but toothless and eyeless, unless he receives an entire artificial equipment. Only when internal, divine forces come to be relied upon, rather than outside reinforcement, will deterioration cease.

Scores of the most eminent physicians, who have risen above the trammels of system, have vigorously expressed themselves regarding the utterly unreliable character of the drug system. Emerson affirmed that “The best part of health is a fine disposition.” Said Plato, “You ought not to attempt to cure the body without the soul.” A distinguished doctor of to-day remarked, “Of the nature of disease, and from whence it comes, we still know nothing, but thanks to chemistry we have new supplies of ammunition. For every drug of our fathers, we have now a hundred. We have iodides, chlorides, and bromides without number; sulphates, nitrates, hydrochlorates, and prussiates beyond count. But we do not believe in heroic doses. We give but little medicine at a time and change it often.” With such supplies of “ammunition,” people within range are liable to get hit.

A mere sketch of the rise and progress of the mind-healing movement may be proper before considering its philosophy. Its novelty having worn off, it is perhaps less prominent as a current topic than formerly, but its progress, though quiet, has been remarkable during the past five years. Careful estimates by those in the best position to judge place the number of those who accept its leading principles, in the United States, at over a million. Owing to the distrust of public opinion, a large majority hold their views quietly but none the less firmly. But a small fraction of its adherents 535are identified with its organizations, and yet within the limits of one school [those distinctively known as Christian Scientists], there are about thirty organized churches, and also one hundred and twenty societies which maintain regular Sunday services, though not yet having church organization. There are also between forty and fifty dispensaries and reading rooms, and a rapidly increasing literature, both of standard works and periodicals. One of the other schools, distinctively known as Mind Cure, has also a large number of organizations similar in character. The number of regularly graduated practitioners cannot be accurately estimated, but they are numbered by the thousand. Of the million more or less of believers in the principles of mind healing, it may be admitted that perhaps a large majority, in the event of severe acute illness, would still make some use of old remedies, or would combine both where circumstances would allow. Life-long habits are tenacious; to defy the force of public opinion, the importunity of friends and the overwhelming aggregation of surrounding belief, is a trying ordeal. Until public opinion softens, mental healing in its purity will be mainly employed in chronic troubles, or at least for those which are not of a sudden and acute nature. Mind healers would differ in acute cases, as to how far those who have had no previous growth of trust in unseen forces should be left to those alone. In the present stage of progress in mind healing, there should be nothing which would require anyone to dispense with reasonable nursing nor with common sense. Some things which are ideally and abstractly true, can only be fully realized in the future, and it is not well to prematurely use them before the conditions are fully ripened.

All new innovations, no matter how much needed, have had to pass through a period when “they were everywhere spoken against.” The time is not distant when personal liberty in respect to choice in one’s method of healing may be enjoyed without unpleasant criticism or notoriety.

The more important schools which agree in the one cardinal principle of healing through mind, designate their respective systems as Christian Science, Mind Cure, and Christian Metaphysics. These terms, in common use, are somewhat interchangeable. There are also those who combine mind healing with Theosophy, and still others who differ in non-essentials.536 What is distinctively known as “Faith Cure” has little in common with those before named. Its theory is that disease is healed by special interposition in answer to prayer. None of the other systems accept anything as special, but believe in the universality and continuity of orderly law.

There are many leaders, authors, and workers in this movement, who are eminent; but as principles are more important than personality, their names need not be enumerated.

Why did this movement originate among women, and why have so large a proportion of its exponents belonged to the so-called weaker sex? Because the intuitional and spiritual senses of women are keener than those of men, and mental healing is not the result of profound reasoning. It is the seeming “weak things of the world which confound the strong.” Men are largely immersed in intellectual and formulated systems, and when the time was ripe for new light and attainment in spiritual evolution to dawn upon humanity, it might have been expected that its first delicate rays would be detected by woman.

The one great principle which underlies all mind healing is contained in the assumption that all primary causation relating to the human organism is mental or spiritual. The mind, which is the real man, is the cause, and the body the result. The mind is the expressor, and the body the expression. The inner life forces build the body, and not the body the life forces. The thought forms the brain, and not the brain the thought. The physical man is but the printed page, or external manifestation, of the intrinsic man which is higher and back of him.

Materia medica deals with effects rather than primary causes. It seeks to modify the expression, which can only be done through the expressor. It is axiomatic that to change results we deal with causes. This principle is so widely recognized that it is seen in an endless variety of phases, even among barbarous and half-civilized races. The charms and incantations used for healing among Indian tribes have this significance. With all their barbarism they are near to nature and keen in locating causation. With nothing more than a superstitious basis, charms, incantations, dances, images, ceremonies, and shrines have a wonderful influence for healing. They divert the mind from the ailment, 537and stimulate a strong faith which awakens the recuperative forces to action, and thus cause a rapid recovery.

A traveller in Algiers relates the following conversation he had with a Moorish woman of high class: “When ill do you go to the doctor?” he asked. “Oh, no; we go to the Marabout; he writes a few words from the Koran on a piece of paper, which we chew and swallow, with a little water from the sacred well at the Mosque. We need no more and soon recover.”

If a skilful exercise of baseless superstition upon mind can be so efficacious, what results are possible by a judicious use of the truth? Mental causation is abundantly proved by the well-known effects of fear, anger, envy, anxiety, and other passions and emotions, upon the physical organism. Acute fear will paralyze the nerve centres, and sometimes turn the hair white in a single night. A mother’s milk can be poisoned by a fit of anger. An eminent writer, Dr. Tuke, enumerates as among the direct products of fear, insanity, idiocy, paralysis of various muscles and organs, profuse perspiration, cholerina, jaundice, sudden decay of teeth, fatal anæmia, skin diseases, erysipelas, and eczema. Passion, sinful thought, avarice, envy, jealousy, selfishness, all press for external bodily expression. Even false philosophies, false theology, and false conceptions of God make their unwholesome influence felt in every bodily tissue. By infallible law, mental states are mirrored upon the body, but because the process is complex and gradual, we fail to observe the connection. Mind translates itself into flesh and blood.

What must be the physical result upon humanity of thousands of years of chronic fearing, sinning, selfishness, anxiety, and unnumbered other morbid conditions? These are all the time pulling down the cells and tissues, which only divine, harmonious, and wholesome thought can build up. Is it surprising that no one is perfectly healthy? If man were not linked to God, and unconsciously receiving an inflow of recuperative vital force, the multitudinous destroyers would soon disintegrate his physical organism. Can the building forces be strengthened, stimulated, and made more harmonious and divine? Yes, through mind. The mind surely but unconsciously pervades every physical tissue with its vital influence, and is present in every function; throbbing in the heart, breathing in the lungs, and weaving 538its own quality into nutrition, assimilation, sensation, and motion.

A conscious fear of any particular disease is not necessary to induce it. The accumulated strands of the unconscious fear of generations have been twisted into the warp and woof of our mentality, and we find ourselves on the plane of reciprocity with disease. Our door is open to receive it. What is disease? A mental spectre, which to material vision has terrible proportions. A kingly tyrant, crowned by our own beliefs. It has exactly that power which our fears, theories, and acceptances have conferred upon it. It is not an objective entity, but our sensuous beliefs have galvanized it into life. “As a man thinketh, so is he.” Realism to us may be conferred upon the most absolute non-entity, if we give it large thought space, and fear it. As a condition, disease is existent; but not as a God-created entity, in and of itself. It appears veritable to us, because we have unconsciously identified the Ego with the body.

The material standpoint is false. We are immaterial; not bodies, but spirits—even here and now. Having lost spiritual consciousness, we practically,—though not theoretically,—feel that we are bodies. To grasp our divine selfhood and steadily hold it, disarms fear and all its allies, and promotes recuperation and harmony. When the intrinsic man dethrones the false and sensuous claimant, and asserts his divine birthright of wholeness [holiness] the body as a correspondence falls into line and gradually expresses health on its own plane. Normally and logically, that which is higher should rule the lower. The body, instead of being the unrelenting despot, then becomes the docile and useful servant. In its subordinate position, where it rightfully belongs, it grows beautiful and harmonious. Men live mainly in their bodily sensations. Such living, though apparently real, is a false sense of life. There is a profound significance in the scriptural injunction, “Take no thought for your body.” The dyspeptic thinks of his stomach, and the more he has it in mind the more abnormally sensitive it becomes. The sound man has no knowledge of such an organ, except as a matter of theory. The body, when watched, petted, and idolized, soon assumes the character of a usurper and tyrant. Retribution is sure and inherent under such conditions.

A change of environment often cures, simply because novelty diverts thought which before has been centered upon the body. The improvement, however, is often credited to better climate, water, or air. Human pride seeks for its causation without rather than within. Secondary causation is really effect, though not often so diagnosed. The draft occasions the cold, but it gets its deadly qualities from cumulative belief and fear. Who has not seen persons in which this bondage and sensitiveness have become so intense that even a breath of God’s pure air alarms them. In this way a great mass of secondary causation has been invested with power for evil, and mistaken for that which is primary. Noting the tremendous power of grown-up accumulations of false belief, we may glance at the modus operandi of mental healing.

There are two distinct lines of treatment which may effect a cure; one by intelligent and persistent self-discipline and culture, and the other through the efforts of another person called a healer. Often there is a combination of both. The power does not lie in the personality of the healer, nor in the exercise of his will-power. Neither hypnotism nor mesmeric control are elements in true mind-healing. The healer, in reality, is but an interpreter and teacher. The divine recuperative forces which exist, but are latent, are awakened and called into action. The patient is like a discordant instrument containing great capabilities, only waiting to respond in unison to active harmony. His distorted thought must be elevated and harmonized, so that he will see things in their true perspective. The healer gently guides him up into the “mount of transfiguration,” where he feels the glow of the divine image within, and sees that wholeness is already his, and will be made manifest as he recognizes it. A successful healer must be an overflowing fountain of love and good-will. He is but a conduit through which flows the divine repletion. He makes ideal conditions present. He steadily holds a mental image of his patient as already whole, and silently appeals to the unconscious mind of the invalid, to induce him to accept the same view. The patient’s mental background is like a sensitive plate, upon which will gradually appear outlines of health as they are positively presented. Improved views of his own condition spring up from within, and seem to him to be original. As 540they grow into expression in the outer man, his cure is complete.

Do failures occur? Undoubtedly, and often. Even infallible principles can have but imperfect application because of local limitations. The failure of a particular field of grain does not disprove the universal principle of vegetable growth. The imperfection of the healer, and the lack of receptivity in the patient, are local limitations. There are sudden cures, but as a rule recovery will be in the nature of a progressive growth. Lack of immediate results often causes disappointment, and leads to an abandonment of the treatment before the seed has had time to take root. The healer is the sower, and the patient’s unconscious mind is the soil. Often rubbish must be cleared away before any fertile spot is found. The cure must come from within. Sometimes the patient is cherishing some secret sin, or giving place to trains of thought colored with envy, jealousy, avarice, or selfishness. These are all positive obstacles to both mental and physical improvement, for thoughts are real things. The patient must actively co-operate with the healer, and make himself transparent to the truth. That which is misshapen has to grow symmetrical. Even if the mind could be instantly permeated with the belief of health, the body will need a little time to completely change its expression. Should these limitations discourage anyone? Not in the least, but rather the reverse. The fact that the cure is in the nature of a growth, is evidence that it is normal and permanent, rather than magical or capricious. Limitations are present, but they can be surmounted.

The phenomenon of pain, so commonly regarded as an evil, is only a warning voice to summon our consciousness from its resting-place in the damp, morgue-like basement of our being, to the higher apartments, where sunshine and harmony are ever present. It is beneficent when its message is heeded, for it is thereby transformed into blessing. Our resistance to it, and misunderstanding of its significance, prevent that possible transformation. The process of cure through mind, though in itself a steady growth, often appears to the consciousness of the patient as vibratory and uneven.

Many could heal themselves without the aid of another, if they appreciated the tremendous power for good of concentrated 541mental delineation of the ideal. By such exercises of mind, a wholesome environment can be built up, even if at first the process seems almost mechanical. But instead of such self-building, out of an infinitude of divine material, the average man is inclined to vacate the control of his being, put his body into the keeping of his doctor, and his soul [himself] into the care of his priest or pastor.

Efficiency for self-treatment is increased as the power of abstraction is cultivated. Hold a firm consciousness of the spiritual self, and of the fact that the material form is only expression made visible. Firmly deny the validity of adverse sensuous evidence, and at length it will disappear. Silently but persistently affirm health, harmony, and the divine image. Give out good thought, for thoughts are real gifts. In proportion as you pour out, the divine repletion pours in. Look upon the physical self as only a false claimant for the Ego. Hold only the good in your field of vision, and let disease and evil fade out to their native nothingness, from lack of standing-room. Even a warfare against evils as objective realities, tends to make them more realistic. At convenient seasons, bar out the external world, and rivet the mind tenaciously to the loftiest ideals and aspirations, and for the time being forget that you possess a body. Oh, victim of nervous prostration and insomnia, test these principles and see if they are not superior to anodynes, opiates, bromides, and chorals, and be assured that they leave no sting behind. The great boon which they bestow is not limited to nervous and mental disorders; its virtue penetrates to the outermost physical limits.

The whole atmosphere of race thought in which we live is sensuous. This vast unconscious influence must be overcome. The mental healer is like one rowing against the current of a mighty river. Humanity is “bound in one bundle,” and it is with difficulty that a few can advance much faster than the rythmical step of the mass. Even the Great Exemplar in some places could not do many mighty works because of surrounding unbelief.

Man is peering into the dust for new supplies of life, which are stored around and above him. Is it not time that he should make a serious effort to throw off the galling yoke of cruel though intangible masters, and achieve freedom and emancipation?

Turning to the religious aspect of mental healing, it is seen to be in harmony with revelation, and also with the highest spiritual ideal in all religions. While rebuking scholastic and dogmatic systems on the one hand, and pseudo-scientific materialism on the other, it vitalizes and makes practical the principles of the Sermon on the Mount. The healing of to-day is the same in kind, though not equal in degree to that of the primitive church. It is in accord with spiritual law, which is ever uniformly the same under like conditions. The miracles of the Apostolic Age were real as transactions, but their miraculous hue was in the materialistic vision of the observers. Healing is the outward and practical attestation of the power and genuineness of spiritual religion, and ought not to have dropped out of the Church. The divine commission to preach the gospel and heal the sick, never rightly could have been severed in twain, because they are only different sides of one Whole. By what authority is one part declared binding through ages and the other ignored? Who will assert that God is changeable, so that any divinely bestowed boon to one age could be withdrawn from a subsequent one? The direct assurance of the Christ, that “these signs shall follow them that believe,” is perpetual in its scope, because “them that believe” are limited to no age, race, or condition. As ecclesiasticism and materialism crept into the early church, and personal ambitions and worldly policies sapped its vitality, spiritual transparency and brotherly love faded out, and with them went the power—or rather the recognition of the power—to heal.

Wonderful works are not limited alone to those who accept the Christian religion; but in proportion as other systems recognize the supremacy of the spiritual element, and catch even a partial glow of “that true light which lighteth every man that cometh into the world,” their intrinsic qualities will be made outwardly manifest. A right conception of God, as infinite present Good, strongly aids in producing the expression of health. “In Him we live, and move, and have our being.” An abiding concept of such truth directly promotes trust, harmony, healing. Seeming ills are not God-created powers, but human perversions and reflected images of subjective states. As a higher and spiritual standpoint is gained, apparent evils dissolve, and then in bold relief is seen the fair proportions of the Kingdom of the Real.

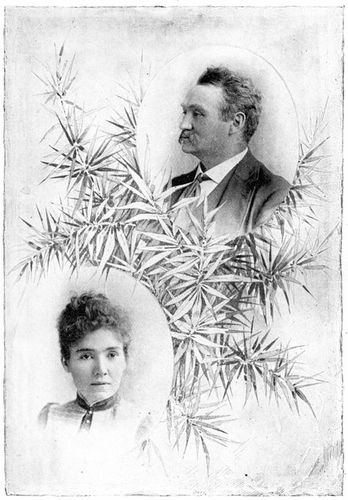

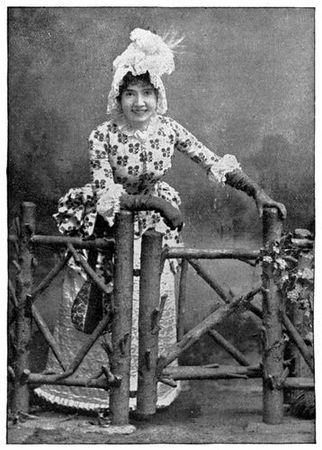

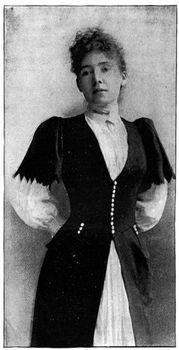

MR. AND MRS. JAS. A. HERNE.

MR. AND MRS. JAS. A. HERNE.

In May last, in a small hall in Boston, on a stage of planking, hung with drapery, was produced one of the most radical plays from a native author ever performed in America. Mr. and Mrs. James A. Herne, unable to obtain a hearing in the theatres for their play, which had been endorsed by some of the best known literary men of the day, were forced to hire a hall, and produce Margaret Fleming bare of all mechanical illusion, and shorn of all its scenic and atmospheric effects. Everybody, even their friends, prophesied disaster. In such surroundings failure seemed certain. But a few who knew the play and its authors better, felt confident that there was a public for them. It was a notable event, and the fame of Margaret Fleming is still on its travels across the dramatic world.

There were two reasons for this result, the magnificent art of Mrs. Herne, which “created illusion by its utter simplicity and absolute truth to life,” and second, because the play was, in fact, as one critic said, “an epoch-marking play.” It could afford to dispense with canvas, bunch-lights, machinery, as it dispensed with conventional plot and epithet, and as its actors discarded declamation and mere noise.

The phenomenal success of Mr. and Mrs. Herne brought them prominently before the literary public. Interest became very strong in them as persons as well as artists, and from an intimate personal acquaintance with them both, I have been asked to give this brief sketch of their work previous to Margaret Fleming, for epoch-marking as it was, it was only a logical latest outcome of the work the Hernes have been doing for the last ten years.

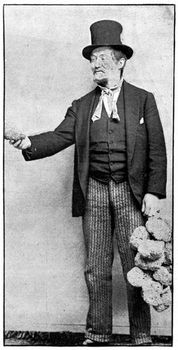

Mr. Herne is a man of large experience, having been on the stage for thirty years. He has been through all the legitimate lines. He has been a member of a stock company, manager of theatres, and author and manager of several plays of his own, previous to the writing of Margaret544 Fleming. His first real attempt at writing was Hearts of Oak. The home scenes, and notably the famous dinner scene, which became such a feature, showed the direction of his power. This play, produced about twelve years ago with Mrs. Herne as “Crystal,” was their first attempt to handle humble American life, and was very successful.

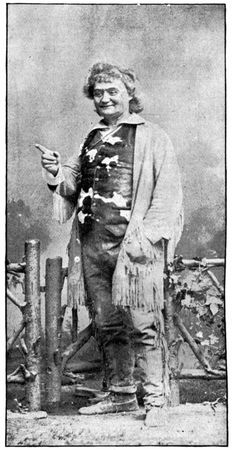

Mr. Herne’s next venture was an ambitious one. It was the writing of a play based upon the American Revolution. In the spring of ‘86 he produced at the Boston Theatre The Minute Men, where it was received with immense enthusiasm. It was somewhat conventional in plot, but in all its scenes of home life was true and fine. The central figures were Reuben (a backwoodsman), and Dorothy, his adopted daughter. Whatever concerned these two characters was keyed to the note of life. Like all Mr. Herne’s acting, Reuben was utterly unconscious of himself. He went about as a backwoodsman naturally does, without posturing or swagger. With the sweetness and quaintness of Sam Lawson, he had the comfortable aspect of a well-fed Pennsylvania Quaker.

Mrs. Herne’s Dorothy was a fitting companion piece, faultlessly true, and sweet, and natural. Her spontaneous laugh is as infectiously gleeful as Joe Jefferson’s chuckle. Those who have never seen her in this part can hardly realize how fine a comedienne she really is.

Mr. Herne’s next play was simpler, stronger, and better, though less picturesque. Drifting Apart was based upon the commonest of life’s tragedies—the home of a drunkard. It is the most effective of sermons, without one word of preaching. The drifting apart of husband and wife through the husband’s “failin’” is set forth with unexampled concreteness, and yet there is no introduction of horror. We understand it all by the sufferings of the wife, with whom we alternately hope and despair. I copy here what I wrote of it at the time when I knew neither Mr. and Mrs. Herne, nor any other of their plays.

The second act in this play for tenderness and truth has not been surpassed in any American play. A daring thing exquisitely done was that holiest of confidences between husband and wife. The vast audience sat hushed as death before that touching, almost sacred scene, as they do when sitting before some great tragedy.

What does this mean, if not that our dramatists have been too distrustful of the public? They have gone round the earth in search of 545material for plays, not knowing that the most moving of all life is that which lies closest at hand, after all.

Mrs. Herne’s acting of Mary Miller was my first realization of the compelling power of truth. It was so utterly opposed to the “tragedy of the legitimate.” Here was tragedy that appalled and fascinated like the great fact of living. No noise, no contortions of face or limbs, yet somehow I was made to feel the dumb, inarticulate, interior agony of a mother. Never before had such acting faced me across the footlights. The fourth act was like one of Millet’s paintings, with that mysterious quality of reserve—the quality of life again.

In this play, as in Hearts of Oak, there was no villain and no plot. The scene was laid in a fishing village near Gloucester. I can do no better than to give you a taste of the quaint second act.

It is Christmas eve and Jack and Mary have been married a year. Jack is preparing to go out. Mary is secretly disturbed over his going but hides it. “Mother” sits by the fire knitting. Mary is sewing by the window.

Jack. Say, Mary! D’you know, I can shave myself better’n any barber thet ever honed a razor?

Mary. I always told you you could, Jack, if you’d only try.

Jack. Feel my face now—ain’t it as smooth as any baby’s?

Mary. (Feeling his face.) Yes, Jack, as smooth as any old baby’s.

Jack. Oh! say, look here now, thet ain’t fair; a feller don’t know nothin’ till he’s forty, does he, mother? Old baby’s! (sitting on the arm of Mary’s chair) I ain’t too old to love you, Mary, that’s one thing. I’ve loved you ever since you was knee-high to a grasshopper. I rocked you in y’r cradle—I’m blessed if I didn’t make the cradle you was rocked in, didn’t I, mother?

Mother. Yes, Jack, an’ d’ye remember what yeh made it out of?

Jack. A herrin’ box. (General laugh.)

Mary. (Tenderly.) I married the man I love, Jack.

Jack. Honest?

Mary. Honest.

Jack. (Kissing her.) Then what’n thunder you want to talk about a feller’s gettin’ old for? Where’s my clean shirt? Say, mother, don’t you t’ hang up them stockin’s.

Mary. Oh! Jack, what nonsense.

Jack. No nonsense at all about it. Christmas is Christmas. It only comes once a year an’ I’m goin’ to have th’ stockin’s hung up. So for fear you’d forgit ‘em I’ll hang ‘em up myself.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary. Please, Jack, give me those stockings.

Jack. Now it ain’t no use, little woman. Them stockin’s is a-goin’ up. Mother, you give me three pins.

Mary. Don’t you give him any pins, mother. Suppose the neighbors should come in and see those stockings hangin’ up.

Jack. Let ‘em come in, I don’t care a continental cuss. Why, Mary, everybody wears stockin’s nowadays, everybody that can afford to. I want the neighbors to see ‘em, then they’ll know we’ve got stockin’s. (Holding up the three stockings.) Got one apiece anyhow.

Mother. Oh, Jack, Jack! you’ll never be anything but a great overgrown boy, if you live to be a hundred (goes off).

Mary. (Tenderly.) Jack!

Jack. Hey?

Mary. (Putting her arms about his neck.) Did you never think that perhaps next Christmas there might be another stocking, just a tiny one, to hang in the chimney corner?

Jack. Why, Mary, there’s tears in your eyes. (Goes to wipe her eyes with the work she has in her hands; it is a baby’s dress.) Bless my soul! What’s this, Mary?

Mary. (Falteringly.) Do you remember Bella and John in “Our Mutual Friend” that I read to you?

Jack. Yes. Warn’t they glorious?

Mary. Well, these are sails, Jack, sails for the little ship that’s coming across the water for you and me.

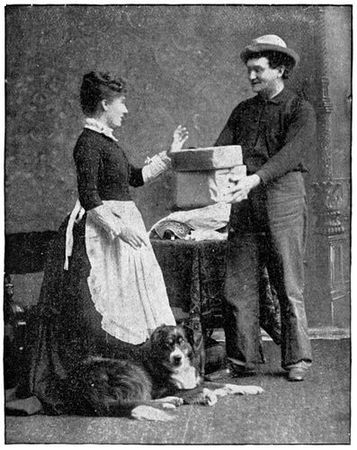

Mr. Herne as Reuben Foxglove in "The Minute Men." See page 544.

Mr. Herne as Reuben Foxglove in "The Minute Men." See page 544.

I quote a few lines from another scene.

Christmas morning. Hester and Silas, some young friends, have come in to take breakfast. All are seated at the table with much bustle and laughter. Lish Mead, Mary’s foster father, pokes his head in the door.

Lish Mead. Wish you Merry Christmas.

All. (Hilariously.) Merry Christmas! Come in.

Lish. Can’t less some on ye hol’s th’ door open.

Silas. I’ll hold it, Lish. (Lish enters, hauling a warehouse truck on which is a barrel of flour and a large hamper.)

Lish. Mister Seward wanted I should hand ye these with his complements.

Mary. Oh, how kind of Mr. Seward, and how good of you to bring ‘em.

Jack. Set down here, Lish, and have a bite o’ breakfast.

Lish. (Taking off mittens, cap, comforter, etc.) Whatcher got? Chicking? Waal, that’s good ‘nough. (Seats himself at table.) Say, Jack, d’ you know, you left a goose a-layin’ on Jim Adamses bar las’ night? I was goin’ to fetch it along but Jim said you gin it to him, swore you made him a present on it.

Mother. Jack Hepburn, did you give that goose—

Mary. (Interrupting her.) Have a cup of coffee, mother.

Lish. Jack, have you got the time o’ day? (Chuckles.) Here’s y’r new Waterbury. The boys wanted I should fetch her ‘round; ye went off las’ night without her.

Jack. Ye can take her back again; I don’t want her.

Mary. O Jack!

Jack. No, Mary, I don’t. I wish the durned ol’ Waterbury ‘d never been born.

Mary. The boys meant well, Jack; I wouldn’t send back their present.

Jack. All right, Mary, if you say so, I’ll take her. There’s one thing sure, every time I wind her up she’ll put me in mind how durn near I come to losin’ the best little wife in the whole world.

This play brought me to know Mr. and Mrs. Herne. It needed but an hour’s talk to convince me that I had met two of the most intellectual artists in the dramatic profession, and also to learn how great were the obstacles which lay in the way of producing a real play, each year adding to the insuperableness of the barriers. Mr. Herne was at that time (two years ago) working upon a new play, in some respects, notably in its theme, finer than Drifting Apart. It was the result of several summers spent on the coast of Maine, and is called Shore-Acres. The story is mainly that of two brothers, Nathaniel and Martin Berry, who own a fine “shore-acre” tract near a booming summer resort. An enterprising grocer in the little village gets Martin interested in booms and suggests that they form a company and cut the shore-acre tract up into lots and sell to summer residents.

Martin comes with the scheme to Nathaniel.

Martin. I’d like t’ talk to yeh, an’ I d’ know’s I’ll hev a better chance.

Uncle Nat. I d’ know’s yeh will.

Martin. (Hesitates, picks up a stick and whittles.) Mr. Blake’s ben here.

Uncle Nat. (Picks up a straw and chews it.) Hez ‘e?

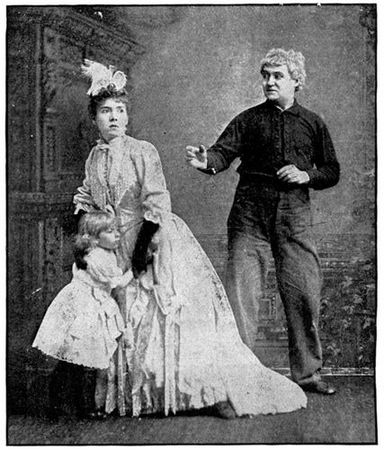

Mrs. Herne as Dorothy Foxglove in "The Minute Men." See page 544.

Mrs. Herne as Dorothy Foxglove in "The Minute Men." See page 544.

Martin. Yes. He ‘lows thet we’d ought to cut the farm up inter buildin’ lots.

Uncle Nat. Dooze ‘e?

Martin. Yes. He says there’s a boom a-comin’ here, an’ thet the lan’s too valu’ble to work.

Uncle Nat. I want t’ know ‘f he dooze. Where d’s he talk o’ beginnin’?