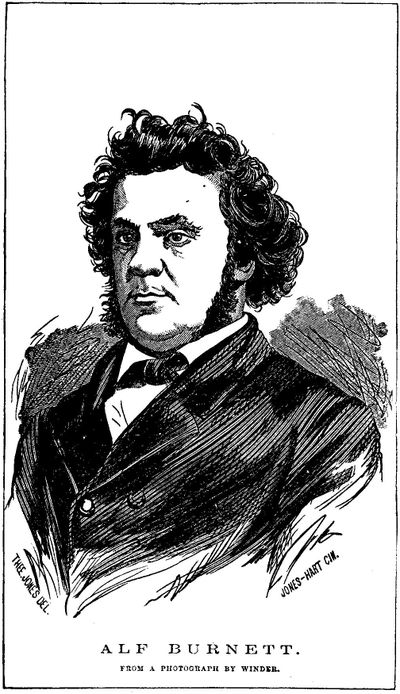

ALF BURNETT.

From A Photograph By Winder.

Title: Incidents of the War: Humorous, Pathetic, and Descriptive

Author: Alfred Burnett

Release date: December 4, 2007 [eBook #23733]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This book was produced from scanned images of public

domain material from the Google Print project.)

[Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. Author's spelling has been maintained.

Page 204: A word was missing after "The Major was right, for a little" "while" has been added.]

ALF BURNETT.

From A Photograph By Winder.

By

COMIC DELINEATOR, ARMY CORRESPONDENT, HUMORIST,

ETC., ETC.

CINCINNATI:

RICKEY & CARROLL, PUBLISHERS,

73 WEST FOURTH STREET.

1863.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1863, by

RICKEY & CARROLL,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United

States for the Southern District of Ohio.

STEREOTYPED AT THE

FRANKLIN TYPE FOUNDRY,

CINCINNATI.

The author of the following sketches, letters, etc., has been known to us for lo, these many years. We have always found him "a fellow of infinite jest," and one who, "though troubles assailed," always looked upon the bright side of life, leaving its reverse to those who could not behold the silver lining to the darkling clouds of their moral horizon. We could fill a good-sized volume with anecdotes illustrating the humorous in Mr. Burnett's composition, and his keen appreciation of the grotesque and ludicrous—relating how he has, many a time and oft, "set the table in a roar," by his quaint sayings and the peculiar manner in which they were said; but we are "admonished to be brief," four pages only being allotted to "do up" the veritable "Don Alfredus," better known by the familiar appellation "Alf."

Mr. Burnett has been a resident of Cincinnati for the past twenty-seven years, his parents removing thereto from Utica, New York, in 1836. Alf, at the Utica Academy, in his earliest youth, was quite noted as a declaimer; his "youth but gave promise of the man," Mr. B., at the present time, standing without a peer in his peculiar line of declamation and oratory. In 1845, he traveled with Professor De Bonneville, giving his (p. iv)wonderful rendition of "The Maniac," so as to attract the attention of the literati throughout the country.

Perhaps one great reason for Mr. Burnett's adopting his present profession was a remark made by the celebrated tragedian, Edwin Forrest. Mr. B. had been invited to meet Mr. Forrest at the residence of S. S. Smith, Esq. Mr. Burnett gave several readings, which caused Mr. Forrest to make the remark, that "Mr. B. had but to step upon the stage to reach fortune and renown." "Upon this hint" Mr. B. acted, and at once entered upon the duties of his arduous profession. In his readings and recitations he soon discovered that it was imperative, to insure a pleasant entertainment, that humor should be largely mingled with pathos; hence, he introduced a series of droll and comical pieces, in the rendition of which he is acknowledged to have no equal. As a mimic and ventriloquist he stands preeminent, and his entertainment is so varied with pathos, wit, and humor, that an evening's amusement of wonderful versatility is afforded.

Mr. Burnett is a remarkably ready writer—too ready, to pay that care and attention to the "rules," which is considered, and justly so, to be indispensable to a correct writer. To illustrate the rapidity with which he composes, we have but to repeat a story, which a mutual friend relates. He met Alf, one afternoon, about five o'clock, he being announced to deliver an original poem in the evening, of something less than a hundred verses. In the midst of the conversation which ensued, Alf suddenly recollected that he had not written a line thereof, and, making his excuses, declared he must go home and write up the "little affair." In the evening a voluminous poem was forthcoming, Alf, in all probability, (p. v)having "done it up" in half an hour "by Shrewsbury clock."

Mr. Burnett has contributed various poems to the literature of the country, which have stamped him as being possessed of a more than ordinary share of the divine afflatus. Among them is "The Sexton's Spade," which has gained a world-wide celebrity. The writer has been connected with Mr. Burnett in the publication of two or three papers, which, somehow or other, never won their way into popular favor: either the public had very bad taste, or the "combined forces" had not the ability to please, or the perseverance to continue until success crowned their labors.

In the commencement of the war, Mr. Burnett was on a tour of the State, in the full tide of prosperity. Immediately after Sumter fell, he summoned to him, by telegraph, his traveling agent, together with Mr. George Humphreys, who had, as an assistant, been with him for years. A consultation was held, which resulted in the determination of all three to enlist in the service of their country. The agent repaired to Chillicothe and joined the 27th Ohio; Humphreys joined the 5th Ohio, and Mr. Burnett enlisted as high private in the 6th Ohio, and served with his regiment in West Virginia, throughout that memorable campaign.

Mr. Burnett was subsequently engaged by the Cincinnati Press, Times, and Commercial, as war correspondent. His letters were read with great avidity, and were replete with wit, humor, and interesting anecdote. His extensive acquaintance enabled him to gather the earliest information, and his letters were always considered among the most reliable. A number of them will be found in the succeeding pages.

(p. vi)That "Incidents of the War" will be found instructive and entertaining, we can but believe, although Mr. Burnett's professional engagements precluded the possibility of his devoting that time and attention to its preparation which was almost imperative. It lays no particular claim to merit as a literary production—being a collection of letters and incidents, which Mr. B.'s publishers thought would be palatable to the public in their present form.

In the volume will be found several pieces for the superior rendition of which Mr. Burnett has been highly extolled. At the close will be found a famous debate, which, although not an incident of the war, is peculiarly spirited, and was delivered by Mr. Burnett before General Rosecrans.

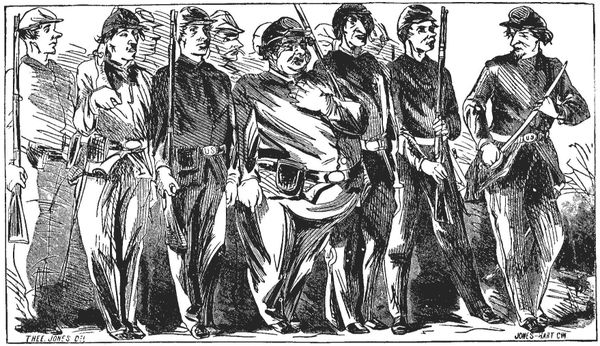

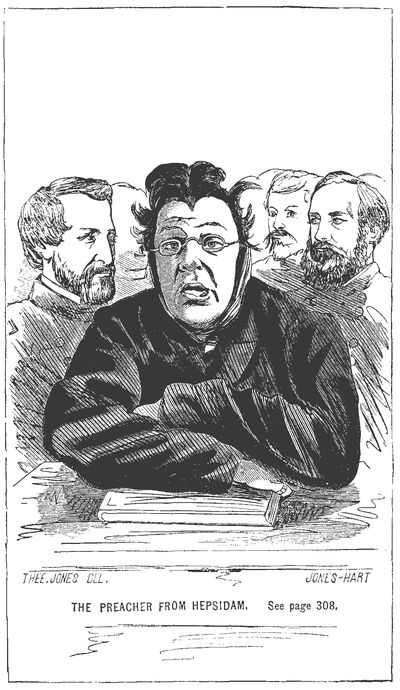

For the graphic illustrations accompanying the volume, Mr. Burnett is indebted to Messrs. Jones & Hart, engravers, and Messrs. Ball & Thomas, photographic artists.

Mr. Burnett is still engaged in giving readings and recitations, in city and village, and, since the death of Winchell, stands almost alone in his profession. Upon a visit to England, some years since, he gained the praise of the English press and public, as a correct delineator of the passions, mimic, and humorist. He is never so well pleased as when before an audience, and receiving the applause of the judicious.

In conclusion, let us hope that "Incidents of the War" may be welcomed by that large number who have had relatives in the armies of the Union, and whose names may, perchance, be found in its pages, while we know the numerous friends of Mr. Burnett will hail its appearance with unfeigned delight.

Page

CHAPTER I 13

Preparatory Remarks — Camp-Life — Incidents of the Battle of Perryville — Brigadier-General Lytle — Captain McDougal, of the 3d Ohio — Colonel Loomis — After the Battle — Rebels Playing 'Possum — Skeered! That Aint no Name for it — Camp Fun, in a Burlesque Letter to a Friend.

CHAPTER II 23

General Nelson — The General and the Pie-Women — The Watchful Sentinel of the 2d Kentucky — The Wagon-Master of the 17th Indiana — Death of General Nelson — His Funeral — Colonel Nick Anderson's Opinion of Nelson.

CHAPTER III 37

Description of a Battle — The 2d Ohio (Colonel Harris) at Perryville — Major-General McCook's Report — Major-General Rousseau's Report — Sketch of Major-General A. McD. McCook.

CHAPTER IV 47

Looking for the Body of a Dead Nephew on the Field of Murfreesboro — The 6th Ohio at Murfreesboro — The Dead of the 6th — The 36th Indiana — Putting Contrabands to Some Service — Anxiety of Owners to Retain their Slaves — Conduct of a Mistress — "Don't Shoot, Massa, here I Is!" — Kidd's Safeguard — "Always Been a Union Man" — Negroes Exhibiting their Preference for their Friends.

CHAPTER V 57

Cutting Down a Rebel's Reserved Timber — Home Again — Loomis and his Coldwater Battery — Secession Poetry — Heavy Joke on an "Egyptian" Regiment.

CHAPTER VI 64

General Turchin — Mrs. General Turchin in Command of the Vanguard of the 19th Illinois — The 18th Ohio at Athens — Children and Fools Always Tell the Truth — Picket Talk — About Soldiers Voting — Captain Kirk's Line of Battle.

(p. viii)CHAPTER VII 70

Comic Scenes — Importation of Yankees — Wouldn't Go Round — Major Boynton and the Chicken — Monotony of Camp-Life — Experience on a Scouting Expedition — Larz Anderson, Esq., in Camp — A Would-be Secessionist Caught in His Own Trap — Guthrie Gray Bill of Fare for a Rebel "Reception" — Pic Russell Among the Snakes.

CHAPTER VIII 80

Fun in the 123d Ohio — A Thrilling Incident of the War — General Kelley — Vote Under Strange Circumstances — Die, But Never Surrender.

CHAPTER IX 87

Our Hospitals — No Hope — A Short and Simple Story — A Soldier's Pride — The Last Letter — Soldierly Sympathy — The Hospitals at Gallatin, and Their Ministering Angels.

CHAPTER X 99

Sports in Camp — Anecdote of the 63d Ohio and Colonel Sprague — Soldier's Dream of Home — The Wife's Reply.

CHAPTER XI 107

The Atrocities of Slavery — The Beauties of the Peculiar Institution — A Few Well-substantiated Facts — Visit to Gallatin, Tennessee.

CHAPTER XII 124

General Schofield — Colonel Durbin Ward — Colonel Connell — Women in Breeches — Another Incident of the War — Negro Sermon.

CHAPTER XIII 135

Letter From Cheat Mountain — the Women of the South — Gilbert's Brigade.

CHAPTER XIV 143

Confessions of a Fat Man — Home-Guard — The Negro on the Fence — A Camp Letter of Early Times — "Sweetharts" Against War.

CHAPTER XV 156

The Winter Campaign in Virginia — Didn't Know of the Rebellion — General W. H. Lytle — Drilling — A Black Nightingale's Song.

CHAPTER XVI 167

Old Stonnicker and Colonel Marrow, of 3d Ohio — General Garnett and his Dogs — "Are You the Col-o-nel of This Post?" — Profanity in the Army — High Price of Beans in Camp — A Little Game of "Draw."

(p. ix)CHAPTER XVII 172

Hard on the Sutler: Spiritualism Tried — A Specimen of Southern Poetry — Singular — March to Nashville — General Steadman Challenged by a Woman — Nigger Question — "Rebels Returning."

CHAPTER XVIII 181

Going Into Battle — Letter To the Secesh — General Garfield, Major-General Rosecrans's Chief of Staff — General Lew Wallace — The Siege of Cincinnati — Parson Brownlow — Colonel Charles Anderson.

CHAPTER XIX 188

An Episode of the War — Laughable Incident — Old Mrs. Wiggles on Picket Duty — General Manson — God Bless the Soldiers — Negro's Pedigree of Abraham Lincoln — A Middle Tennessee Preacher — A Laconic Speech.

CHAPTER XX 194

Union Men Scarce — How They Are Dreaded — Incidents — The Wealthy Secessionists and Poor Union Widows — The John Morgans of Rebellion — A Contraband's Explanation of the Mystery — Accident at The South Tunnel — Impudence of the Rebels — A Pathetic Appeal, etc.

CHAPTER XXI 201

A Friendly Visit for Corn into an Egyptian Country — Ohio Regiments — "Corn Or Blood" — "Fanny Battles" — The Constitution Busted in Several Places — Edicts Against Dinner-horns, by Colonel Brownlow's Cavalry — A Signal Station Burned — Two Rebel Aids Captured.

CHAPTER XXII 207

Reward for a Master — Turning the Tables — Dan Boss and His Adventure — Major Pic Russell — A Visit To the Outposts With General Jeff C. Davis — Rebel Witticisms — Hight Igo, Ye Eccentric Quarter-Master — Fling Out to the Breeze, Boys.

CHAPTER XXIII 216

Defense of the Conduct of the German Regiments at Hartsville — To The Memory of Captain W. Y. Gholson — Colonel Toland Vs. Contraband Whisky.

CHAPTER XXIV 222

War and Romance — Colonel Fred Jones — Hanging in the Army — General A. J. Smith vs. Dirty Guns.

(p. x)CHAPTER XXV 232

A Trip into the Enemy's Country — The Rebels twice driven back by General Steadman — Incidents of the Charge of the 1st Tennessee Cavalry, under Major Tracy — The 35th and 9th Ohio in the Fight — Colonel Moody and the 74th Ohio — Colonel Moody on the Battle-field.

CHAPTER XXVI 240

A Wedding in the Army — A Bill of Fare in Camp — Dishonest Female Reb — Private Cupp — To the 13th Ohio.

CHAPTER XXVII 248

The Oath — A Conservative Darkey's Opinion of Yankees — Visit to the Graves of Ohio and Indiana Boys — Trip from Murfreesboro to Louisville — Nashville Convalescents — A Death in the Hospital — Henry Lovie Captured.

CHAPTER XXVIII 256

General Steadman Superseded by General Schofield, of Missouri — Colonel Brownlow's Regiment — His Bravery — A Rebel Officer Killed by a Woman — Discontent in East Tennessee — Picket Duty and Its Dangers — A Gallant Deed and a Chivalrous Return.

CHAPTER XXIX 263

An Incident at Holly Springs, Miss. — The Raid by Van Dorn — Cincinnati Cotton-dealers in Trouble — Troubles of a Reporter.

CHAPTER XXX 268

A Reporter's Idea of Mules — Letter from Kentucky — Chaplain Gaddis turns Fireman — Gaddis and the Secesh Grass-widow.

CHAPTER XXXI 279

A Visit To the 1st East Tennessee Cavalry — A Proposed Sermon — Its Interruption — How ye Preacher is Bamboozled out of $15 and a Gold Watch — Cavalry on the Brain — Old Stonnicker Drummed Out of Camp — Now and Then.

CHAPTER XXXII 289

An Incident of the 5th O. V. I. — How To Avoid the Draft — Keep the Soldiers' Letters — New Use of Blood-hounds — Proposition to Hang the Dutch Soldiers — The Stolen Stars.

Debate Between Slabsides and Garrotte. 303

Sermon From "Harp of a Thousand Strings." 308

Preparatory Remarks — Camp-Life — Incidents of the Battle of Perryville — Brigadier-General Lytle — Captain McDougal, of the 3d Ohio — Colonel Loomis — After the Battle — Rebels Playing 'Possum — Skeered! That Aint no Name for it.

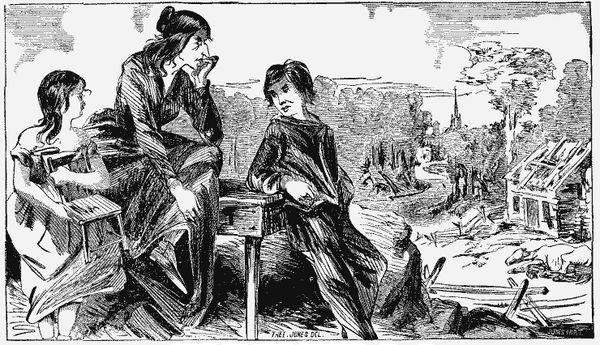

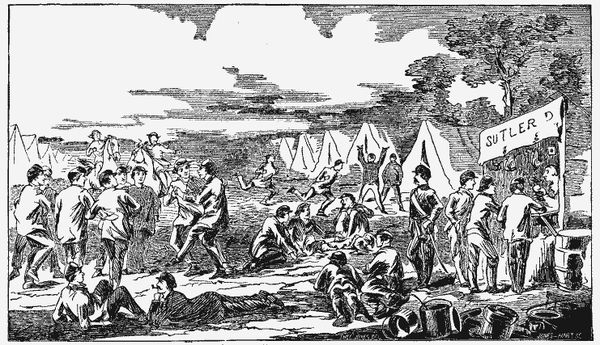

In a two-years' connection with the army, a man with the most ordinary capacity for garnering up the humorous stories of camp may find his repertoire overflowing with the most versatile of incidents. A connection with the daily press is, however, of great service, especially as a letter-writer is expected to know all that occurs in camp—and more too!

The stories that I shall relate are no fictions, but veritable facts, to most of which I was myself an eye-witness.

The hardships of camp-life have been so often depicted by other pens that it will be unnecessary for me to bring them anew before the public. A few jolly spirits in a regiment frequently sway the crowd, and render the hours pleasant to the boys which otherwise would prove exceedingly wearisome; and many a surgeon has remarked, that it would amply remunerate (p. 014)Government to hire good, wholesome amusement for the benefit of the soldiers when not on active duty. Frequently, when visiting various hospitals, have I noticed the brightening eye of the patients as I have told them some laughable incident, or given an hour's amusement to the crowd of convalescents—a far preferable dose, they told me, to quinine. A word of praise to the suffering hero is of great value.

I remember, the day after the battle of Perryville, visiting the hospital of which Dr. Muscroft was surgeon. I had assisted all day in bringing in the wounded from the field-hospital, in the rear of the battle-ground. The boys of the 10th and 3d Ohio were crowded into a little church, each pew answering for a private apartment for a wounded man. One of the surgeons in attendance requested me to assist in holding a patient while his leg was being amputated. This was my first trial, but the sight of the crowd of wounded had rendered my otherwise sensitive nerves adamant, and as the knife was hastily plunged, the circle-scribe and the saw put to its use, the limb off, scarce a groan escaped the noble fellow's lips. Another boy of the 10th had his entire right cheek cut off by a piece of a shell, lacerating his tongue in the most horrible manner: this wound had to be dressed, and again my assistance was required, and I could but notice the exhilarating effect a few words of praise that I bestowed upon his powers of endurance had. This was invariably the case with all those whom it was my painful duty to assist. The effect of a few words of praise seemed quite magical.

Men frequently fight on, though severely wounded, (p. 015)so great is the excitement of battle, and I am cognizant of several instances of men fainting from loss of blood, who did not know they were wounded, until, several minutes afterward, they were brought to a realization of the fact through a peculiar dizzy, sickening feeling. Brigadier-General (then Colonel) Lytle, who commanded a brigade during that battle, it is said, by boys who were near him, after the severe wound he received, fought on several minutes. A field-officer, whose name I have forgotten, being shot from his horse, requested to be lifted back into the saddle, and died shortly afterward. Captain McDougal, of Newark, Ohio, commanding a company in the 3d Ohio, who, with sword upraised, and cheering on his noble boys, received a fatal shot, actually stepped some eight or ten paces before falling. Colonel Loomis, of the celebrated Loomis Battery, who did such service in that engagement, says he saw no dead about him; yet there they lay, within a few feet of his battery. Loomis at one time sighted one of his favorite pieces, taking what he called a "fair, square, deliberate aim," and, sure enough, he knocked over the rebel gun, throwing it some feet in the air; at the sight of which he was so elated that he fairly jumped with delight, and cheer after cheer rang out from the men of his command, and it was not until a whizzing shot from the remaining guns of the rebels' battery warned him that they were not yet conquered, that his boys were again put to work, and eventually quieted their noisy antagonists. At one time, during that fight, the rebels tried to charge up the hill from "Bottom's farm-house," but were repulsed. At that time the 10th and 3d Ohio, aided by the 15th Kentucky Regiment, (p. 016)were holding the eminence; the rebels were protected by a stone wall that skirted the entire meandering creek, giving them, at times, the advantage of an enfilading fire; our boys were partly covered by what was known as "Bottom's barn." Many of our wounded had crawled into this barn for protection, but a rebel shell exploding directly among the hay set the barn on fire, and several of our poor wounded boys perished in the flames.

Colonel Reed, of Delaware, Ohio, was in command at Perryville, some time after the battle, and it is a disgraceful fact that the rebels left their dead unburied. At one spot, in a ravine, they had piled up thirty bodies in one heap, and thrown a lot of cornstalks over them; and on the Springfield road, to the right, as you entered the town of Perryville, a regular line of skirmishers lay dead, each one about ten paces from the other; they had evidently been shot instantly dead, and had fallen in their tracks; and there they laid for four days. One, a fine-looking man, with large, black, bushy whiskers, was within a few yards of the toll-gate keeper's house, (himself and family residing there,) who, apparently, was too lazy to dig a grave for the reception of the rebel's body.

As a matter of course, the first duty is to the wounded, but these people seemed to pay no attention to either dead or wounded. And it was not until a peremptory order from Colonel Reed was issued, that the rebel-sympathizing citizens condescended to go out and bury their Confederate friends; and this was accomplished by digging a deep hole beside the corpse, and the diggers, taking a couple of fence-rails, would (p. 017)pry the body over and let it fall to the bottom: thus these poor, deluded wretches found a receptacle in mother Earth.

Accompanied by Mr. A. Seward, the special correspondent of the Philadelphia Inquirer, the day after the fight I visited an improvised hospital in the woods in the rear of the battle-ground. There we found some twenty Secesh, who had strayed from their command, and were playing sick and wounded to anybody who came along. They had guards out watching, and, as I suspected they were playing sharp, I bethought me of trying "diamond cut diamond;" so I dismounted, and having on a Kentucky-jeans coat, I ventured a "How-de, Boys?"

They eyed us pretty severely, and ventured the remark that they needed food, and would like some coffee or sugar for the wounded boys. I went inside the log-house, telling them I would send some down; that we were farming close by there; "Dry-fork" was the place; we would send them bread. After we had gained their confidence, they wanted to know how they could get out of the State without being captured; said they had not been taken yet, although several of the Yanks had been there; but the "d—d fools" thought they were already paroled.

We told them that as soon as they got well we would pilot them safely out. They said they had already been promised citizens' clothing by Mrs. Thompson and some other rebel ladies. They then openly confessed that there was only one of them wounded, and that they had used his bloody rags for arm-bandages and head-bandages only for the brief period when they were (p. 018)visited by suspicious-looking persons; but, as we were all right, they had no hesitancy in telling us they were part of Hardee's corps, and were left there by accident when the rebel forces marched.

By a strange accident they were all taken prisoners that afternoon by a dozen Federal prowlers, who kindly took them in out of the wet.

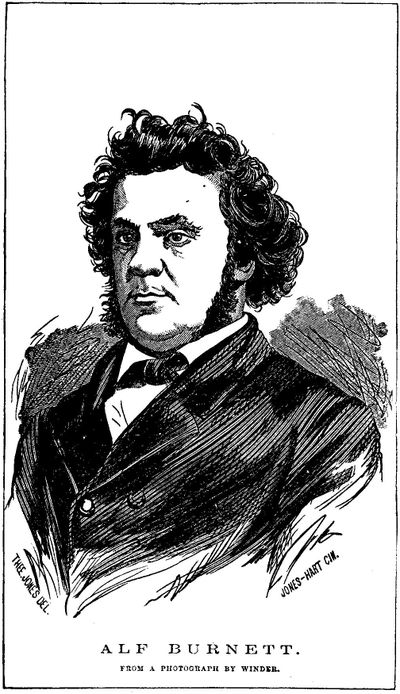

About a mile and a half to the rear of the field of battle there stands, in a large, open field, a solitary log-house containing two rooms. The house is surrounded by a fence inclosing a small patch of ground. The chimney had been partly torn away by a cannon-ball. A shell had struck the roof of the building, ripping open quite a gutter in the rafters. A dead horse lay in the little yard directly in front of the house, actually blocking up the doorway, while shot and shell were scattered in every direction about the field in front and rear of this solitary homestead. I dismounted, determined to see who or what was in the house—

"Darkness there, and nothing more."

A board had been taken from the floor, exhibiting a large hole between two solid beams or logs. An empty bedstead, a wooden cupboard, and three chairs were all the furniture the house contained. Hurrying across the field, we caught up with a long, lank, lean woman. She had two children with her: a little boy about nine, and a girl about four years of age. The woman had a table upon her head. The table, turned (p. 019)upside down, contained a lot of bedding. She had a bucket full of crockery-ware in one hand, and was holding on to the table with the other. The children were loaded down with household furniture of great convenience. As it was growing dark, I inquired the nearest road to Perryville. The woman immediately unloaded her head, and pointing the direction, set one leg on the table, and yelled to the boy—

"Whoray up, Jeems; you are so slow!"

"How far is it, madam?"

"O, about a mile and a half. It aint more nor that, no how."

"Who lived in that house?" said I, pointing to the log-cabin I had just left.

"I did."

"Were you there during the fight?"

"Guess I was."

"Where was your husband?"

"He wor dead."

"Was he killed in the battle?"

"No; he died with the measles."

"Why didn't you leave when you found there was going to be a fight?"

"I did start for to go, but I seed the Yankees comin' thick, and I hurried back t'other way; and jest as I e'enamost got to the brush yonder, I seed the 'Confeds' jest a swarmin' out of the woods. So, seeing I was between two fires, I rund back to the house."

"Wasn't you afraid you'd be killed?"

"Guess I was."

"What did you do when they commenced firing?"

(p. 020)"I cut a hole in the floor with the ax, and hid between the jists."

"Did they fight long upon your ground?"

"It seemed to me like it wor TWO WEEKS."

"You must have been pretty well scared; were you not?"

"Humph! skeered! Lor bless you, skeered! That aint no name for it!"

Skeered! That ain't no name for it.

The other morning I was standing by Billy Briggs, in our tent.

"Hand me them scabbards, Jimmy," said he.

"Scabbards!" said I, looking round.

"Yes; boots, I mean. I wonder if these boots were any relation to that beef we ate yesterday. If they will only prove as tough, they'll last me a long time. I say, Cradle!" he called out, "where are you?"

Cradle was our contraband, with a foot of extraordinary length, and heel to match.

"What do you call him Cradle for?" I inquired.

"What would you call him? If he aint a cradle, what's he got rockers on for?"

Cradle made his appearance, with a pair of perforated stockings.

"It's no use," said Billy, looking at them. "Them stockings will do to put on a sore throat, but won't do for feet. It is humiliating for a man like me to be without stockings. A man may be bald-headed, and it's genteel; but to be barefooted, it's ruination. The legs are good, too," he added, thoughtfully, "but the (p. 021)feet are gone. There is something about the heels of stockings and the elbows of stove-pipes, in this world, that is all wrong, Jimmy."

A supply of stockings had come that day, and were just being given out. A pair of very large ones fell to Billy's lot. Billy held them up before him.

"Jimmy," said he, "these are pretty bags to give a little fellow like me. Them stockings was knit for the President, or a young gorilla, certain!" and he was about to bestow them upon Cradle, when a soldier, in the opposite predicament, made an exchange. "Them stockings made me think of the prisoner I scared so the other day," said Billy.

"How's that?" said I.

"He saw a big pair of red leggings, with feet, hanging up before our tent. He never said a word, till he saw the leggings, and then he asked me what they were for. 'Them!' said I, 'them's General Banks's stockings.' He looked scared. 'He's a big man, is General Banks,' said I, 'but then he ought to be, the way he lives.' 'How?' said he. 'Why,' said I, 'his regular diet is bricks buttered with mortar.'"

The next day Billy got a present of a pair of stockings from a lady; a nice, soft pair, with his initials, in red silk, upon them. He was very happy. "Jimmy," said he, "just look at 'em," and he smoothed them down with his hand—"marked with my initials, too; 'B,' for my Christian name, and 'W' for my heathen name. How kind! They came just in the right time, too; I've got such a sore heel."

Orders came to "fall in." Billy was so overjoyed with his new stockings he didn't keep the line well.

(p. 022)"Steady, there!" growled the sergeant; "keep your place, and don't be moving round like the Boston post-office!"

We were soon put upon the double-quick. After a few minutes, Billy gave a groan.

"What is it, Billy?" said I.

"It's all up with 'em," said he.

I didn't know what he meant, but his face showed something bad had happened. When we broke ranks and got to the tent, he looked the picture of despair—shoes in hand, and his heels shining through his stockings like two crockery door-knobs.

"Them new stockings of yours is breech-loading, aint they, Billy?" said an unfeeling volunteer.

"Better get your name on both ends, so that you can keep 'em together," said another.

"Shoddy stockings," said a third.

Billy was silent. I saw his heart was breaking, and I said nothing. We held a council on them, and Billy, not feeling strong-hearted enough for the task, gave them to Cradle to sew up the small holes.

I saw him again before supper; he came to me looking worse than ever, the stockings in his hand.

"Jimmy," said he, "you know I gave them to Cradle, and told him to sew up the small holes; and what do you think he has done? He's gone and sewed up the heads."

"It's a hard case, Billy; in such cases, tears are almost justifiable."[Back to Contents]

General Nelson — The General and the Pie-Women — The Watchful Sentinel of the 2d Kentucky — The Wagon-Master of the 17th Indiana — Death of General Nelson — His Funeral — Colonel Nick Anderson's Opinion of Nelson.

A great many stories have been told about General Nelson, with whom the writer was upon the most intimate terms. That Nelson was a noble, warm-hearted, companionable man, those even most opposed to his rough manner, at times, will readily admit.

Nelson was strongly attached to the 6th Ohio. From his very first acquaintance he said he fell in love with it, and his feeling was reciprocated, for the 6th was as ardently devoted to him.

At Camp Wickliffe the General was very much annoyed by women coming into his camp, and he had given strict orders that none should be admitted on the following Sunday, as he intended reviewing the division that day. His chagrin and rage can only be imagined by those who knew him, when, upon this veritable occasion, he saw at least thirty women huddled together, on mares, mules, jacks, jennies, and horses. The General rode hastily to Lieutenant Southgate, exclaiming—

"Captain Southgate, I thought I ordered that no (p. 024)more of those d—d women should come into my camp. What are they doing here?"

"I promulgated your order, General," replied Captain Southgate.

"Well, by ——, what are they here for?" and riding up to the bevy of women in lathed and split bonnets, he inquired, in a ferocious manner, "What in —— are all you women doing here?"

Now, the party was pretty well frightened, but there was one with more daring than the rest, who sidled up to the General, and, with what was intended to be a smile, (but the General said he never saw a more "sardonic grin" in his life,) she answered for the party, and said:

"Sellin' pies, Gin'ral."

"Selling pies, eh! Selling pies, eh! Let me see 'em; let me see 'em, quick!"

The woman untied one end of a bolster-slip, and thrust her arm down the sack, and brought forth a specimen of the article, which Nelson seized, and vainly endeavored to break. It was like leather. The General gave it a sudden twist and broke it in two, when out dropped three or four pieces of dried apple.

"By ——, madam, you call them pies, do you? Pies, eh! Those things are just what are giving all my boys the colic! Get out of this camp every one of you! Clear yourselves!"

The camp was thus cleared of pie-venders, who escaped on the double-quick.

General Nelson was a strict disciplinarian, and frequently tested his pickets by a personal visit. Upon one occasion he rode through a drenching rain to the (p. 025)outposts; it was a dark night, and mud and water were knee-deep in some parts of the road. A portion of the 2d Kentucky was on guard, and as the General rode up he met the stern "Halt" of the sentinel, and the usual "Who comes there?"

"General Nelson," was the reply.

"Dismount, General Nelson, and give the countersign," was the sentinel's command.

"Do you know who you are talking to, sir? I tell you I am your General, and you have the impudence to order me to dismount, you scoundrel!"

"Dismount, and give the countersign, or I will fire upon you," was the stern rejoinder.

And Nelson did dismount, and gave the countersign, and at the same time inquired the sentinel's name, and to what regiment he belonged. The following day the man was sent for, to appear forthwith at head-quarters. The soldier went with great trepidation, anticipating severe treatment from the General for the previous night's conduct. Imagine his surprise when the General invited him in, complimented him highly, in the presence of his officers, and requested, if at any time he required any service from him, to just mention that he was the soldier of the 2d Kentucky who had made him dismount in mud and rain, and give the countersign.

On another occasion he was riding along the road, and was accosted by two waggish members of the 6th Ohio.

"Hallo! mister," said one of the boys, "won't you take a drink?"

"Where are you soldiers going to?" inquired the General.

(p. 026)"O, just over here a little bit."

"What regiment do you belong to?"

"Sixth Ohio."

"Well, get back to your camp, quick!"

The boys, although they knew him well, took advantage of the fact that the General displayed no insignia of his rank, and replied:

"They guessed they'd go down the road a bit, first."

"Come back! come back!" shouted the General. "How dare you disobey me? Do you know who I am, you scoundrels?"

"No, I don't," said one of the boys; and then, looking impudently and inquiringly into his face, said: "Why! ain't you the wagon-master of the 17th Indiana?"

Nelson thought activity the best cure for "ennui," and consequently kept his men busy. One day, calling his officers together, he ordered them to prepare immediately for a regular, old-fashioned day's work; "for," said he, "there has been so little work done here since the rain set in, that I fear drilling has fallen in the market; but if we succeed in keeping up that article, I am sure cotton must come down."

He was exceedingly bitter in his denunciations of the London Times and rebel British sympathizers, remarking to me, one evening, that he was exceedingly anxious this war should speedily end, "for," said he, "I would like nothing better than to see our people once more united as a nation; and then I want fifty thousand men at my command, so that I could march them to Canada, and go through those provinces like a dose of croton."

(p. 027)I was present at the Galt House, in Louisville, when General Nelson was shot by General Davis, and immediately telegraphed the sad news to the daily press of Cincinnati. The following was my dispatch:

General Nelson Shot by General Davis.

Louisville, September 29.

Eds. Times: I just witnessed General Jeff C. Davis shoot General Nelson. It occurred in the Galt House, in the entry leading from the office. The wound is thought to be mortal.

Alf.

Later.—General Nelson Dead.

Louisville, September 29, 10 A.M.

General Nelson is dead. I will telegraph particulars as soon as possible.

Alf.

THIRD DISPATCH.

Particulars of the Affair.

Louisville, September 29, 11 A.M.

Eds. Times: Jefferson C. Davis, of Indiana, went into the Galt House, at half-past eight o'clock this morning. He met General Nelson, and referred to the treatment he had received at his hands in ordering him to Cincinnati. Nelson cursed him, and struck Davis in the face several times. Nelson then retired a few paces, Davis borrowing a pistol from a friend, who, handing it to him, remarked, "It is a Tranter trigger—be careful."

I had just that moment been in conversation with the General.

Alf.

The particulars were afterward given in a letter, which is here inserted:

Louisville, September 29, 1862.

The greatest excitement of the day has been in discussing the death of General Nelson, and the causes which led to the terrible denouement.

(p. 028)Sauntering out in search of an "item"—my custom always in the morning—I happened to be in the Galt House just as the altercation between General Nelson and General Jeff C. Davis was reaching its climax, and of which I telegraphed you within ten minutes after its occurrence. From what I learn, from parties who saw the commencement, it would seem that General Davis felt himself grossly insulted by Nelson's overbearing manner at their former meeting; and seeing him standing talking to Governor Morton, Davis advanced and demanded an explanation, upon which Nelson turned and cursed him, calling him an infamous puppy, and using other violent language unfit for publication. Upon pressing his demand for an explanation, Nelson, who was an immensely powerful and large man, took the back of his hand and deliberately slapped General Davis's face. Just at this juncture I entered the office. The people congregated there were giving Nelson a wide berth. Recognizing the General, I said "Good morning, General," (at this time I was not aware of what had passed). His reply to me was: "Did you hear that d——d insolent scoundrel insult me, sir? I suppose he don't know me, sir. I'll teach him a lesson, sir." During this time he was retiring slowly toward the door leading to the ladies' sitting-room. At this moment I heard General Davis ask for a weapon, first of a gentleman who was standing near him, and then meeting Captain Gibson, who was just about to enter the dining-room, he asked him if he had a pistol? Captain Gibson replied, "I always carry the article;" and handed one to him, remarking, as Davis walked toward Nelson, "It is a Tranter trigger."

(p. 029)Nelson, by this time, reached the hall, and was evidently getting out of the way, to avoid further difficulty.

Davis's face was livid, and such a look of mingled indignation, mortification, and determination I never before beheld. His hand was slowly raised; and, as Nelson advanced, Davis uttered the one word, "Halt!" and fired. Nelson, with the bullet in his breast, completed the journey up the entire stairs, and then fell. As he reached the top, John Allen Crittenden met him and said, "Are you hurt, General?" He replied, "Yes, I am, mortally." "Can I do any thing for you?" continued Crittenden. "Yes; send for a surgeon and a priest, quick."

A rush was made by the crowd toward the place as soon as he was shot. No effort, as far as I can learn, has been made to arrest General Davis.

A few minutes after the occurrence I was introduced to the Aid of Governor Morton, who told me he saw it all, from the very commencement, and that, had not Davis acted as he did, after the gross provocation he received, Davis would have deserved to have been shot himself.

It is a great pity so brave a man should have had so little control over his temper. Although very severe in his discipline and rough in his language, the boys of his division were devotedly attached to him, because he was a fighting man. The 6th Ohio, especially, were his ardent admirers. He was hated here, bitterly hated, by all Secessionists; this of itself should have endeared him to Union men.

The Louisville Journal, this afternoon, in speaking of the affair, says:

(p. 030)"General Nelson, from the first, thought the wound was a mortal one, and expressed a desire to have the Rev. Mr. Talbott, of Calvary Church, summoned. This gentleman resides about three miles below the city, but was unable to get home on Sunday after service, and passed the night at the Galt House. He immediately obeyed the summons, as he was well acquainted with the General. The reverend gentleman informs us that the dying man spoke no word concerning the difficulty, and made no allusion to his temporal affairs, but was exceedingly solicitous as to the salvation of his soul, and desired Mr. Talbott to perform the rite of baptism, and receive him into the bosom of the Church.

"After five minutes' conversation, to ascertain his state of preparedness, the clergyman assented to his wish, and the solemn ordinance was administered with unusual impressiveness, in the presence of Dr. Murray, the medical director, Major-General Crittenden, and a few other personal friends. When the service concluded, he was calm, and sank into his last sleep quietly, with no apparent physical pain, but with some mental suffering. The last audible words that he uttered were a prayer for the forgiveness of his sins. That appeal was made to Almighty God. Let, then, his fellow-mortals be proud of his many virtues, his lofty patriotism, and undaunted courage, while they judge leniently of those faults, which, had they been curbed, might have been trained into virtues. Let it not be said of our friend—

"'The evil that men do lives after them,

The good is oft interred with their bones.'"

The funeral of General Nelson took place yesterday afternoon. The corpse of the General was incased in a most elegant rosewood coffin, mounted with silver. The American flag, that he had so nobly fought under at Shiloh, was wrapped about it; his sword, drawn for the last time by that once brave hand, lay upon the flag. Bouquets were strewed upon the coffin.

Major-General Granger, Major-General McCook, and Major-General Crittenden, and Brigadier-General Jackson, assisted by other officers, conveyed the remains from the hearse to the church-door, and down the aisle. As they entered the building, Dr. Craig commenced reading the burial service for the dead. As soon as they reached the pulpit, and set down the corpse, the choir chanted a requiem in the most impressive manner. Rev. Dr. Craig then read the 15th chapter of the First Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians, 21st to the 29th verses:

"For since by man came death, by man came also the resurrection of the dead.

"For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive."

After the reading of this, the Rev. Mr. Talbott, he whom General Nelson had sent for immediately upon being shot, and who had administered to his spiritual welfare, and received him into the Church, delivered one of the most beautiful and eulogistic discourses I ever heard.

He said that the General had been, in private life, one of the most congenial and warm-hearted of men; (p. 032)his hand ever open to the needy. He had known him well.

The last half-hour of his life was devoted entirely to the salvation of his soul; he did not refer to worldly matters. Mr. Talbott told him he must forgive all whom he thought had injured him. His reply was, "O! I do, I do forgive—I do forgive. Let me," said Nelson, "be baptized quick, for I feel I am fast going."

Mr. T. then administered to him the sacred rite, and in a few minutes, conscious to the last, smiling and serene, he passed to "that bourne from which no traveler returns."

"A more contrite heart and thorough Christian resignation," said the divine, "I never saw."

The discourse over, the body was conveyed again to the hearse.

Lieutenant-Colonel Anderson, of the 6th Ohio, had command of the escort, which consisted of two companies of the 2d Ohio, and two companies of the 6th, all being from his old and tried division. No relatives, I believe, were here, except Captain Davis, a foster-brother, belonging to the 2d Minnesota Regiment.

General Nelson's gray horse was led immediately behind the hearse, the General's boots reversed and fastened in the stirrups. An artillery company and cavalry squadron completed the cortège, which moved slowly down Second Street to the beat of the muffled drum.

He has gone to his long home! Though rash and impetuous at times, we must not forget our country has lost a noble defender, a man of true courage—one who was looked up to by his division.

(p. 033)To-day he was to join them; and as I went through the old Fourth Division, last Sunday, the boys were all in a jubilee, because Nelson was going to be with them, and they remarked, "If he is along, he'll take us where we'll have fighting!"

As I have before told you, everywhere Secessionists are rejoicing at his death, and Kentucky ones especially. The Union men of Kentucky have lost a noble defender.

Yesterday General Rousseau's division of ten thousand men was reviewed. They are a splendid body of men.

There will be no examination of Jeff C. Davis before the civil authorities, but the affair is to be investigated by a court-martial.

A singular incident is related of General Nelson. It is said that the Rev. Dr. Talbott, who resides a few miles from the city, wished to return home on Sunday night last. Nelson refused him the pass. On Monday morning it was this reverend gentleman who was sent for by Nelson, and received Nelson into the Church, and who performed the funeral services to-day.

Yours, Alf.

The gallant Colonel Nick Anderson, who so bravely led the 6th Ohio at Shiloh, and more recently at Murfreesboro, in speaking of Nelson, says:

"And what is said will be assented to by all who shared his familiar moments, that, outside of his military duties, he was a refined gentleman. Whatever may be said of his severe dealing with his subordinates, his violent manner when reprimanding them, (p. 034) every one who knew him will bear witness that it was only to exact that iron discipline which makes an army irresistible. His naval education, in which discipline is so mercilessly enforced, will explain clearly his intensity of manner when preparing his forces for the terrible trials of the march or the battle-field. However much he was disliked by subordinate and inefficient officers, he was beloved by his men, the private soldiers.

"How carefully he looked after all their wants, their clothing, their food—in short, whatever they needed to make them strong and brave! for it was a maxim with him, that, unless a man's back was kept warm and his stomach well supplied, he could not be relied upon as a soldier. All who know Buell's army will bear witness to the splendid condition of Nelson's division.

"General Nelson earned his rank as major-general by no mysterious influences at head-quarters, but by splendid achievements on the battle-field. It has been said that his division was the first to enter Nashville; so it was the first in Corinth; but these are the poorest of his titles to distinction. It was his success in Eastern Kentucky, in destroying the army of General Marshall; and, greatest of all, his arrival, by forced marches, at Pittsburg Landing, early enough on Sunday afternoon, the 9th of April, to stop the victorious progress of General Beauregard, that placed him among his country's benefactors and heroes, and which will 'gild his sepulcher, and embalm his name.'

"But for Nelson, Grant's army might have been destroyed. His forced march, wading deep streams, brought him to the field just in time. An hour later, and all might have been lost."

(p. 035)An officer of his division has recounted to me some thrilling incidents of that memorable conflict.

"It was nearly sunset when Nelson, at the head of his troops, landed on the west bank of the river, in the midst of the conflict. The landing and shore of the river, up and down, were covered by five thousand of our beaten and demoralized soldiers, whom no appeals or efforts could rally. Nelson, with difficulty, forced his way through the crowd, shaming them for their cowardice as he passed, and riding upon a knoll overlooking his disembarking men, cried out, in stentorian tones: 'Colonel A., have you your regiment formed?' 'In a moment, General,' was the reply. 'Be quick; time is precious; moments are golden.' 'I am ready now, General.' 'Forward—march!' was his command; and the gallant 6th Ohio was led quickly to the field.

"That night Nelson asked Captain Gwynne, of the 'Tyler,' to send him a bottle of wine and a box of cigars; 'for to-morrow I will show you a man-of-war fight.'

"During the night Buell came up and crossed the river, and by daylight next morning our forces attacked Beauregard, and then was fought the desperate battle of Shiloh. Up to twelve M. we had gained no decisive advantage; in fact, the desperate courage of the enemy had caused us to fall back. 'General Buell,' said my informant, 'now came to the front, and held a hasty consultation with his Generals. They decided to charge the rebels, and drive them back. Nelson rode rapidly to the head of his column, his gigantic figure conspicuous to the enemy in front, and in a voice that rang like a (p. 036)trumpet over the clangor of battle, he called for four of his finest regiments in succession—the 24th Ohio, 36th Indiana, 17th Kentucky, and 6th Ohio. 'Trail arms; forward; double-quick—march;' and away, with thundering cheers, went those gallant boys. The brave Captain (now Brigadier-General) Terrell, who alone was left untouched of all his battery, mounted his horse, and, with wild huzzas, rode, with Nelson, upon the foe.

"It was the decisive moment; it was like Wellington's 'Up, guards, and at them!' The enemy broke, and their retreat commenced. That was the happiest moment of my life when Nelson called my regiment to make that grand charge.

"Let the country mourn the sad fate of General Nelson. He was a loyal Kentuckian; fought gallantly the battles of his Government; earned all his distinction by gallant deeds. All his faults were those of a commander anxious to secure the highest efficiency of his troops by the most rigid discipline of his officers, and in this severe duty he has, at last, lost his life.

"His death, after all, was beautiful. He told Colonel Moody, in Nashville, that, though he swore much, yet he never went to bed without saying his prayers; and now, at last, we find him on his death-bed, not criminating or explaining, but seeking the consolations of religion. Requiescat in pace!"[Back to Contents]

Description of a Battle — The 2d Ohio (Colonel Harris) at Perryville — Major-General McCook's Report — Major-General Rousseau's Report — Sketch of Major-General A. McD. McCook.

"Then shook the hills with thunder riven,

Then rushed the steeds to battle driven,

And, louder than the bolts of heaven,

Far flashed the red artillery!"

Many of you have, no doubt, looked upon the field of battle where contending hosts have met in deadly strife. But there are those whose eyes have never gazed upon so sad a sight; and to such I may be enabled to present a picture that will at best give you but a faint idea of the terrible reality of a fiercely-contested field.

Imagine thousands upon thousands on either side, spreading over a vast expanse of ground, each armed with all the terrible machinery of modern warfare, and striving to gain the advantage of their opponents by some particular movement, studied long by those learned in the art of war.

Then comes the clang of battle; steel meets steel, drinking the blood of contending foes. The sabers flash and glitter in the sunlight, descending with terrible force upon devoted heads, which were once pillowed (p. 038)on the bosoms of fond and devoted mothers. Jove's dread counterfeit is heard on every hand; the balls and shells go whistling and screaming by, the most terrible music to ears not properly attuned to the melody of war. Thousands sink upon the ground overpowered, to be trodden under foot of the flying steed, or their bones to be left whitening the incarnadined field. Blows fall thick and heavy on every hand. The cries of the wounded and the orders of the commanders mingle together; and, to the uninitiated, all appears "confusion worse confounded."

But there is a method in all this seeming madness; and that which appears confusion is the result of well-laid plans. But as there is "many a slip 'twixt the cup and the lip," so there are slips in the actions of the best regulated armies. Gunpowder, shot, shell, and steel are not always to be implicitly relied upon: even they sometimes fail in carrying out what were conceded to be designs infallible; so true it is that "man proposes, but God disposes."

It has been my province to witness battles wherein Western men were the heroes; and that Western men will fight, has been pretty well authenticated during the present war. I have noticed the brave conduct of the gallant troops, the fighting boys of the various regiments of the West, and have never known them to falter in the hour of danger. They left their homes totally uneducated in warfare; they are now veterans—each a hero.

The conduct of the 2d Ohio at Perryville is spoken of thus by a correspondent:

"The brigade of Len Harris was in the center, and (p. 039)met the shock simultaneously with the left and right. The whole brigade was in the open fields, with the rebels in the woods before them. Long and gallantly did they sustain their exposed positions. An Illinois regiment, of Terrell's brigade, flying from the field, ran through this brigade, with terrible cries of defeat and disaster; but the gallant boys of the 2d Ohio and 38th Indiana only laughed at them, as, lying down, they were literally run over by the panic-stricken Illinoisans. Hardly had they disappeared in the woods in Harris's rear when the rebels appeared in the woods in his front. At the same time Rousseau came galloping along the line, and they received him with cheers, and the rebels with a terrible fire. Terrible was the shock on this part of the line, but gallant was the resistance. Up the hill came the rebels, and made as gallant a charge as ever was met by brave men. But, O! so terrible and bloody was the repulse! Along the line of the 2d Ohio and 38th Indiana and Captain Harris's battery, I saw a simultaneous cloud of smoke arise. One moment I waited. The cloud arose, and revealed the broken column of rebels flying from the field, but, in the distance, a second rapidly advancing. The shout that arose from our men drowned the roar of cannon, and sent dismay into the retreating, broken column."

In Major-General McCook's report of that battle, he says it was "the bloodiest battle in modern times for the number of troops engaged on our side," and "the battle was principally fought by Rousseau's division; and if there are, or ever were, better soldiers than the old troops engaged, I have neither seen nor read of (p. 040)them." Speaking of the new troops, General McCook points out those under the command of Colonel Harris, saying: "For instance, in the Ninth Brigade, where the 2d and 33d Ohio, 68th Indiana, and 10th Wisconsin fought so well, I was proud to see the 94th and 98th Ohio vie with their brethren in deeds of heroism." The 94th and 98th were new troops, and the example of the old soldiers in Colonel Harris's brigade, and the distinguished courage and good judgment of the Colonel, gave them confidence, and they stood in the storm like veterans.

... "I then returned to Harris's brigade, hearing that the enemy was close upon him, and found that the 33d Ohio had been ordered further to the front by General McCook, and was then engaged with the enemy, and needed support. General McCook, in person, ordered the 2d Ohio to its support, and sent directions to me to order up the 24th Illinois also, Captain Mauf commanding. I led the 24th Illinois, in line of battle, immediately forward, and it was promptly deployed as skirmishers by its commander, and went gallantly into action, on the left of the 33d Ohio. The 2d Ohio, moving up to support the 33d Ohio, was engaged before it arrived on the ground where the 33d was fighting. The 38th Indiana, Colonel B. F. Scribner commanding, then went gallantly into action, on the right of the 2d Ohio. Then followed in support the 94th Ohio, Colonel Frizell. I wish here to say that this regiment, although new, and but few weeks in the (p. 041) service, behaved most gallantly, under the steady lead of its brave Colonel Frizell. Colonel Harris's whole brigade—Simonson's battery on its right—was repeatedly assailed by overwhelming numbers, but gallantly held its position. The 38th Indiana and 2d Ohio, after exhausting their ammunition and that taken from the boxes of the dead and wounded on the field, still held their position, as did also, I believe, the 10th Wisconsin and 33d Ohio. For this gallant conduct these brave men are entitled to the gratitude of the country, and I thank them here, as I did on the field of battle....

"I had an opportunity of seeing and knowing the conduct of Colonel Starkweather, of the Twenty-eighth Brigade, Colonel Harris, of the Ninth Brigade, and of the officers and men under their command, and I can not speak too highly of their bravery and gallantry on that occasion. They did, cheerfully and with alacrity, all that brave men could do...."

"I herewith transmit the reports of Colonels Starkweather, Harris, and Pope, and also a list of casualties in my division, amounting, in all, to 1,950 killed and wounded. My division was about 7,000 strong when it went into the action. We fought the divisions of Anderson, Cheatham, and Buckner.

"I am, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

"Lovell H. Rousseau."

It will not be amiss here to give a brief outline of the early history, coming down to a recent date, of the renowned hero, Major-General A. McD. McCook, United States Volunteers.

He was born in Columbiana County, Ohio, April (p. 042)22, 1831. At the age of sixteen he entered the Military Academy at West Point, as a cadet. He graduated in July, 1852, and was commissioned Brevet Second Lieutenant, in the 3d Regiment United States Infantry. After being assigned to duty for a few months, at Newport Barracks, Ky., he was ordered, in April, 1853, to join his regiment, then serving in the Territory of New Mexico. Here he remained nearly five years, constantly on active duty in the field, and participating in all the Indian campaigns on that wild and remote frontier. His long services and good conduct were mentioned in General Orders by Lieutenant-General Winfield Scott. In January, 1858, he was ordered from New Mexico to West Point, and assigned to duty in the Military Academy, as instructor in Tactics and the Art of War. On the breaking out of the rebellion he was relieved from duty there, and ordered, in April, 1861, to Columbus, Ohio, to muster in volunteers. Before his arrival there he was elected Colonel of the 1st Ohio Volunteers, a three-months regiment, already on its way to the seat of war in Virginia; and hastening to join the command, to which he was elected without his knowledge or solicitation, soon had an opportunity of exhibiting those admirable qualities as a field-officer for which he has since become so justly distinguished. His coolness in the unfortunate affair at Vienna, and his consummate military skill in the management of his command at Bull Run, were universally commended. At the close of that eventful conflict he marched his regiment back to Centerville in the same good order in which it had left there, an honorable exception to the wide-spread (p. 043)confusion and disorder that prevailed elsewhere among the National forces.

When the three-months troops were mustered out of the service he received permission to raise the 1st Regiment Ohio Volunteers, a three-years regiment; but on the 3d of September, 1861, and before his command was ready to take the field, he was appointed Brigadier-General of Volunteers, and assigned to command the advance of the Federal forces then in Kentucky, at Camp Nevin. Here, and at Green River, he organized his splendid Second Division, with which he afterward marched to Nashville, and thence toward the Tennessee River.

On the 6th of April, 1862, alarmed by the sullen sound of distant artillery, and learning the precarious situation of Grant's army, he moved his division, over desperate roads, twenty-two miles, to Savannah, and there embarked on steamboats for Pittsburg Landing. After clearing a way with the bayonet through the army of stragglers that swarmed upon the bank of the river, soon after daylight on the morning of the 7th of April, the Second Division of the Army of the Ohio advanced through the sad scenes of our defeat the day before, and deployed, with stout hearts and cheers, upon the field of Shiloh. General McCook fought his troops that day with admirable judgment. He held them in hand; his line of battle was not once broken—it was not once retired; but was steadily and determinedly advanced until the enemy fled, and the reverse of the day before was more than redeemed by a splendid victory.

In the movement on Corinth, a few weeks after the (p. 044)battle of Shiloh, General McCook had the honor of being in the advance of General Buell's army corps, and his skirmishers were among the first to scale the enemy's works.

The rank of major-general of volunteers was soon after conferred upon him, in view of his distinguished services—a promotion not undeserved.

After the evacuation of Corinth, the command of General McCook was moved through Northern Alabama to Huntsville, thence to Battle Creek, where his forces remained for two months, in front of Bragg's army at Chattanooga. Upon the withdrawal of Buell's army from Alabama and Tennessee, General McCook moved his division, by a long march of four hundred miles, back to Louisville.

Here he was assigned to command the First Corps in the Army of the Ohio, and started on a new campaign, under Buell, in pursuit of Bragg. The enemy were met and engaged near Perryville, and two divisions of McCook's corps (one of them composed of raw recruits) bore the assault of almost the entire army of General Bragg. The unexpected and unannounced withdrawal of General Gilbert's forces on his right; the sad and early loss of those two noble soldiers, Terrell and Jackson, and the tardiness of reinforcements, made the engagement a desperate one, and resulted in a victory, incomplete but honorable, to the Union forces. After the battle of Chaplin Hills, Bragg's army, worn and broken, fled in dismay from Kentucky. The army corps of Major-General McCook was afterward moved to Nashville, and he assumed command of the Federal forces in that vicinity.

(p. 045)On the 6th of November, 1862, on the arrival of Major-General Rosecrans, who succeeded Major-General Buell in command, General McCook was assigned to command the right wing in the Department of the Cumberland. On the 26th of December, 1862, the Army of the Cumberland moved from Nashville to attack the enemy in position in front of Murfreesboro. General McCook commanded the right. On the evening of December 30 the two armies were in line of battle, confronting each other. Rosecrans had massed his reserves on the left, to crush the rebel right with heavy columns, and turn their position. Bragg, unfortunately, learning of his dispositions during the night, massed almost his entire army in front of McCook, and in the gray of the following morning, and before we had attacked on the left, advanced with desperate fury upon the right wing. Outnumbered, outflanked, and overpowered, the right was forced to retire, not, however, until its line of battle was marked with the evidences of its struggle and the fearful decimation of the enemy. To check the advancing rebel masses, already flushed with anticipated victory, the Federal reserves moved rapidly to the rescue. The furious onslaught of the enemy was resisted, and the right and the fortunes of the day were saved.

The rebels, whipped on the left and center, checked on the right, foiled in every attack, having lost nearly one-third of their numbers, fled from the field on the night of the 3d of January, and the victorious Union army advanced through their intrenchments into Murfreesboro. The great battle of Stone River, dearly won, and incomplete in its results, was yet a victory.

(p. 046)The right was turned and forced to retire in the first day's fight. Whether this was attributable to accidental causes, that decide so many important engagements, or to the superior generalship of the rebel commander, it is at least certain that generalship was not wanting in the disposition of the forces under General McCook; nor was courage wanting in his troops.

Major-General McCook now commands the Twentieth Army Corps.[Back to Contents]

Looking for the Body of a Dead Nephew on the Field of Murfreesboro — The 6th Ohio at Murfreesboro — The Dead of the 6th — The 35th Indiana — Putting Contrabands to Some Service — Anxiety of Owners to Retain their Slaves — Conduct of a Mistress — "Don't Shoot, Massa, here I Is!" — Kidd's Safeguard — "Always Been a Union Man" — Negroes Exhibiting their Preference for their Friends.

On the gory field of Murfreesboro, upon the ushering in of the new year, many a noble life was ebbing away. It was a rainy, dismal night; and, on traversing that field, I saw many a spot sacred to the memory of my loved companions of the glorious 6th Ohio. I incidentally heard of the death of a nephew in that fight. I thought of his poor mother. How could I break the news to her! Yes, there was I, surrounded by hundreds of dead and wounded, pitying the living. O, how true it is that—

Death's swift, unerring dart brings to its victim calm and peaceful rest,

While those who live mourn and live on—the arrow in their breast!

With anxious haste I sought his body during that night. Many an upturned face, some with pleasing smile, and others with vengeance depicted, seemed to meet my gaze.

Stragglers told me to go further to the left. "There's where Crittenden's boys gave 'em h—l!" Just to the (p. 048)right of the railroad I found young Stephens, of the 24th Ohio. His leg was shattered. He called me by name, and begged me to get him some water, as he was perishing. I went back to the river, stripped three or four dead of their canteens, and filled them, and returned. He told me that young Tommy Burnett was only wounded. He saw him carried back. This relieved my anxiety. The next day the dead were buried. There, amid the shot and shell and other debris of the battle-field, the dead heroes of the 6th lie, until the last trump shall call.

A few days afterward I met one of the officers of that regiment. Of him I eagerly inquired as to its fate. A tear fell from his manly eye as he exclaimed, "O, sad enough, Alf! Our boys were terribly cut up; but they fought like tigers—no flinching there; no falling out of line; shoulder to shoulder they stood amid the sheeted flame; and, though pressed by almost overwhelming numbers, no blanched cheek, no craven look, not the slightest token of fear was visible. The boys were there to do or die. They were Ohio boys, and felt a pride in battling for their country and her honor." And when I asked of names familiar, the loss, indeed, seemed fearful. "What became," said I, "of Olly Rockenfield?" "Dead!" was the reply. "And George Ridenour?" "Wounded—can not live!"

Dave Medary, a perfect pet of the regiment, a boy so childlike, so quiet in his deportment, yet with as brave a heart as Julius Cæsar—Little Dave was killed! I saw his grave a few days after. It was half a mile to the left of the railroad; and, although it was January, the leaves of the prairie-rose were full and (p. 049)green, bending over him as if in mourning for the early dead.

Jack Colwell—few of the typos of Cincinnati but knew Jack, or Add, as he was frequently called—poor Jack died from want of attention! His wound was in the leg, below the knee. I saw him a week after the battle, and the ball was not yet extracted.

Adjutant Williams, Lieutenant Foster, Captain McAlpin, Captain Tinker, Lieutenant Schaeffer, young Montaldo, Harry Simmonds, A. S. Shaw, John Crotty, and many others, were wounded or killed in the terrific storm of shot and shell sent by the rebel horde under Breckinridge. At one time every standard-bearer was wounded, and for a moment the flag of the 6th lay in the dust; but Colonel Anderson seized it and waved it in proud defiance, wounded though he was. The Colonel soon found claimants for the flag, and had to give it up to those to whose proud lot it fell to defend it.

O! the wild excitement of a fight! How completely carried away men become by enthusiasm! They know no danger; they see none—are oblivious to every thing but hope of victory! Men behold their boon companions fall, yet onward they dash with closed ranks, themselves the next victims.

There are few in the Army of the Cumberland who have not heard of the 35th Indiana, commanded by Colonel Mullen, of Madison, and as fine an Irish regiment as ever trod the poetic sod of the Emerald Isle. On their march up from Huntsville, Alabama, toward Louisville, Kentucky, on the renowned parallel run between Buell and Bragg, the command were short of provisions. Half-rations were considered a rarity. (p. 050)Father Cony, who is at all times assiduous in his duties to his flock, had called his regiment together, and was instilling into their minds the necessity of their trusting in Providence. He spoke of Jesus feeding the multitude upon three barley loaves and five small fishes. Just at this juncture an excitable, stalwart son of Erin arose and shouted: "Bully for him! He's the man we want for the quarter-master of this regiment!"

Early in January General Rosecrans issued his orders that all the men that could possibly be spared from detail duty should be immediately placed into the ranks, and that negroes should be "conscripted" or captured to take their places as teamsters, blacksmiths, cooks, etc. By this means the Third Division of the Army of the Cumberland, then under General James B. Steadman, was increased eight hundred men—men acclimated—men who could shoulder a musket. This was all done in less than three weeks. The negroes were all taken from rebel plantations.

One morning Colonel Vandeveer, of the 35th Ohio, commanding the Third Brigade, sent an orderly to my tent to inquire if I would not like to accompany an excursion into the enemy's country. As items were scarce, I at once assented; and, although scarce daybreak, off we went. The Colonel informed me that, as I was a good judge of darkeys, General Steadman had advised my going with the party.

We called first at Mrs. Carmichael's, and got two boys, aged, respectively, fifteen and seventeen. Mrs. Carmichael begged, and, finally, wept quite bitterly at the prospect of losing her boys—said those were all she had left—(she had sent the others South). She (p. 051)plead with us not to take "them boys"—said "they wern't no account—couldn't do nothing nohow." But the mother of these boys told our men a different story, and begged us to take the boys, "For," said she, "dey does all de plantin' corn and tendin' in de feel. Dey's my chill'n, and if I never sees 'em agin, I want de satisfaction of knowin' dey is free!"

Mrs. Carmichael's supplications for the negroes not to be taken from her were quite pitiful. She said they had been allers raised jest like as they were her own flesh and blood, and she just keered for 'em the same. But, as Mrs. Carmichael had two sons in the rebel army, the boys were taken. Upon the first order to come with us they seemed delighted, which caused the mistress to become very wrathy. I told the boys to go to their cabin and get their blankets, as they would need them. Judge my surprise when this kind-hearted woman, who had just informed me that she had "allers treated them boys as if they were her own flesh and blood"—this woman seized the blankets from the half-naked boys, and fairly shrieked at them: "You nasty, dirty little nigger thieves! if them Yankees want to steal you, let 'em find you in blankets; I'm not a-going to do it!" I merely inquired if that was the way in which she treated her other children—those in the rebel army?

From thence we went to Mrs. Kidd's, who had a husband and two sons in the rebel service. On our approach she endeavored to secrete some of the blacks, but they wouldn't "stay hid." The cause of the visit was explained. The rebels had been driving most of the likely negroes South. They were using them (p. 052)against the Government; and it was thought, by some, that they might as well work for as against the Union. They were raising their crops, running their mills, manufacturing their army-wagons, etc., besides supporting the families of the rebels, thus placing every able-bodied white man of the South in the hands of the government. The Federal service needed teamsters and hospital nurses and cooks.

Mrs. Kidd seemed quite a reasonable woman—said she thought she understood the policy of the North, and that the South knew that slavery was their strength. I made the remark, that, probably, if her husband knew she would be left without help, perhaps he would be induced to return and respect the old flag that had at all times, while he was loyal to it, defended him.

This little speech on my part elicited a rejoinder from a young miss, a daughter of Mrs. Kidd, sixteen or seventeen years of age, who flirted around, and with a nose that reached the altitude of at least "eighty-seven" degrees, exclaimed—

"I don't want my par nor my brothers to come home not till every one of you Yankees is driven from our sile!"

Some of the boys were busy hunting for a secreted negro, one whom this young lady had stored away for safety. A soldier opened a smoke-house door, at which the young Secesh fairly yelled—

"There aint no nigger there! You Yankees haint a bit o' sense! You don't know a smoke-house from a hut, nohow!"

Supposing the negro, who we felt almost sure was there, might possibly have escaped, we were about retiring (p. 053)with those already collected, when I suggested, loud enough for any one to hear about the building, that the whole squad should pour a volley through that rickety old dormer-window that projected from the room, when, much to our astonishment, and amid roars of laughter, appeared a woolly head, white eye-balls distended, the darkey yelling loud and fast—

"Don't shoot, massa! don't shoot! here I is! I's a comin'! De missus made me clime on dis roof. I wants to go wid you folks anyhow!"

Mr. Crossman's plantation was then visited; but, as the rebels had driven him away because of his Unionism, and taken his horses, his property was undisturbed by us.

From thence we visited Nolinsville—met a gang of twenty "likely-looking boys," stout, healthy fellows, who had clubbed together to come to the Union camp. They told us the rebs were only four miles off, "scriptin' all the niggers dar was in de fields, and a-runnin' 'em South." These were added to our stock in trade.

On our way back, a couple of old, sour-looking WOMEN were standing on the steps that were built for them to climb a fence, who, seeing so many blacks, inquired what we were taking them for. "To work," was the reply. "The rebels were about to run them South, and we wanted them to work for us."

"Now who told you that?" they inquired.

"The negroes themselves, madam. Many of them came voluntarily, to escape being sent South."

"O, yes! you Federals git your information from the niggers altogether."

"Yes, madam!" facetiously replied Captain Dickerson, (p. 054)of the 2d Minnesota Regiment, "that's a fact. All the reliable information does come from them."

On our homeward trip we called at what is known as "Kidd's Mills," between Concord Church and Nolinsville. There were there quite a number employed upon the lumber and grist. A selection was made from the lot. They all wanted to come, but some were too young, and others too old.

Old man Kidd said he had a "safeguard from the Gineral. The Gineral had been up to see his darters, Delilah and Susan, and give him a safeguard." Upon examination it was found to be a mere request. Requests don't stand in military (not arbitrary enough). Then the old man declared he had always been a Union man—"allers said this war wern't no good—that the South had better stand by the old flag."

I at once told him if such was the case he was all right—to just get his horse and come with me, and if he had "allers" been a "Union man" or a non-combatant, why, they would all be returned to him.

The negroes were grouped around with anxious faces, and with rather astonished looks; and, as Mr. Kidd went to the stable, a venerable, white-haired old darkey, who had been told to stand back—he was too old to join the Union teamsters—came forward, and begged to be taken. "Why, I does heap o' work. I tends dis mill; I drives a team fustrate. Please take de ole man, and let him die free!"

Another negro, too old to take, spoke up and said: "What was dat de old man Kidd told you?"

"Why," I replied, "he said he had always been a Union man."

(p. 055)"De Lor' bress my soul! Did he say dat he was a Union man?"

"Yes!"

"Well! well! well! Dat he was a Union man! Well! well! well! And he's gwine to de Gineral for to tell him dat; and dat ole man is a member ob de Church! Well! well! well! Why, look heah, my Men', when de rebs was here only a few weeks ago—when dey was here, dat ole man got on his white hoss, and took de seceshum flag, and rode, and rode, and waved dat rebel flag and shouted, and more dan hollered for Jeff Davis, and now he Union man! He wants de Gineral to gib up dese here colored people—dat's what's de matter wid him!"

In an hour after we arrived in camp, sure enough, the old Kidd and other parties were there, expecting or hoping to get their darkeys back; but General Steadman told them if the negroes wished to return, they could do so, but, if they chose rather to work for "Uncle Sam," why, his orders were to use them.

"Well, Gineral, you just tell my niggers that they can go home with me," said Kidd.

"O! they can if they want to." So, out goes Kidd, smiling as a "basket of chips."

"Boys, the Gineral says you can all go home with me."

"If you want to," was my addition to his sentence.

Not a negro stirred from the line. After a brief consultation, in an under tone, at which Kidd, I noticed, was becoming very impatient, Kidd broke the quietude by saying:

"Come on, boys—come, Jim."

(p. 056)Jim looked over to Bob and said: "Bob, what are you going to do?"

"Me! Ise gwine to stay for de Union!"

Old man Kidd looked beaten. "Well, Jim, what will you do?"

"O! I does what Bob does!"

This same old Kidd had been in the habit of going over the country enlisting recruits for the rebel service—telling them that he was an old man, or he would go himself; that the old folks expected to be taxed to take care of the soldiers' families; that if they wanted corn or any thing from his mill, while they were in the army, to come and get it. By such language he induced several men, who had only small families, to enlist. One of them was indebted to Kidd about thirteen dollars, and after he had been in the army a month or two, Kidd dunned him for the old bill, remarking:

"Well, John, you're in the army now, gittin' your regular pay now—guess you can pay that little bill now, can't you?"[Back to Contents]