| THE STARRY FLAG SERIES,BY OLIVER OPTIC.

|

Title: Breaking Away; or, The Fortunes of a Student

Author: Oliver Optic

Illustrator: Samuel Smith Kilburn

Release date: August 29, 2007 [eBook #22433]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from scans of public domain material produced by

Microsoft for their Live Search Books site.)

| THE STARRY FLAG SERIES,BY OLIVER OPTIC.

|

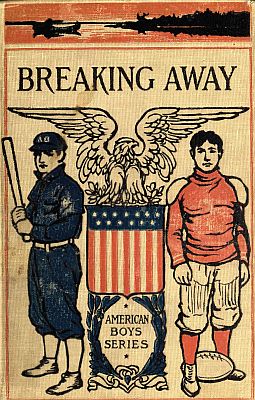

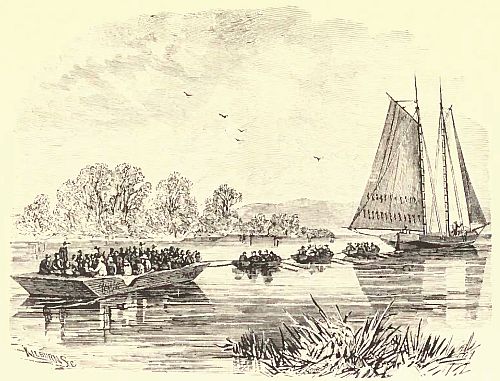

THE REBELLION IN THE PARKVILLE LITERARY INSTITUTE.—Page 30.

THE REBELLION IN THE PARKVILLE LITERARY INSTITUTE.—Page 30.

"Breaking Away" is the second of the series of stories published in "Our Boys and Girls," and the author had no reason to complain of the reception accorded to it by his young friends, as it appeared in the weekly issues of the Magazine; but, on the contrary, he finds renewed occasion cordially to thank them for their continued appreciation of his earnest efforts to please them.

After an experience of more than twenty years as a teacher, the writer did not expect his young friends to sympathize with the schoolmaster of this story, for doubtless many of them have known and despised a similar creature in real life. Mr. Parasyte is not a myth; but we are grateful that an enlightened public sentiment is every year rendering more and more odious the petty tyrant of the school-room, and we are too happy to give this retreating personage a parting blow as he retires from the scene of his fading glories.

Rebellions, either in the school or in the state, are always dangerous and demoralizing; but while we unequivocally condemn[6] the tyrant in our story, we cannot always approve the conduct of his pupils. One evil gives birth to another; but even a righteous end cannot justify immoral means, and we beg to remind our young and enthusiastic readers that Ernest Thornton and his friends were compelled to acknowledge that they had done wrong in many things, and that "Breaking Away" was deemed a very doubtful expedient for the redress even of a real wrong.

As it was impossible for Ernest to relate the whole of his eventful history in one volume, Breaking Away will be immediately followed by a sequel,—"Seek and Find,"—in which the hero will narrate his adventures in seeking and finding his mother, of whose tender care he was deprived from his earliest childhood.

Harrison Square, Mass.,

September 23, 1867.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| In which Ernest Thornton introduces Himself. | 11 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| In which there is Trouble in the Parkville Liberal Institute. | 22 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| In which Ernest is expelled from the Parkville Liberal Institute. | 33 |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| In which Ernest sails the Splash, and Takes a Bath. | 44 |

CHAPTER V. | |

| In which Ernest declines a Proposition. | 55 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| In which Ernest finds his Fellow-Students in open Rebellion. | 66 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| [8]In which Ernest attends the Trial of Bill Poodles and Dick Pearl. | 78 |

CHAPTER VIII. | |

| In which Ernest vanquishes the Schoolmaster. | 89 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

| In which Ernest strikes a heavy Blow, and wins another Victory. | 100 |

CHAPTER X. | |

| In which Ernest has an Interview with his Uncle. | 111 |

CHAPTER XI. | |

| In which Ernest is disowned and cast out. | 122 |

CHAPTER XII. | |

| In which Ernest raises the Splash, and there is a general Breaking Away among the Students. | 132 |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

| In which Ernest is chosen Commodore of the Fleet. | 144 |

CHAPTER XIV. | |

| In which Ernest is waited upon by a Deputy Sheriff. | 155 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

| In which Ernest and the Commissary visit Cannondale. | 166 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| [9]In which Ernest conveys the Students to Pine Island. | 177 |

CHAPTER XVII. | |

| In which Ernest finds there is Treason in the Camp. | 188 |

CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| In which Ernest and his Companions land at Cannondale. | 199 |

CHAPTER XIX. | |

| In which Ernest and his Friends are disgusted with Mr. Parasyte's Ingratitude. | 211 |

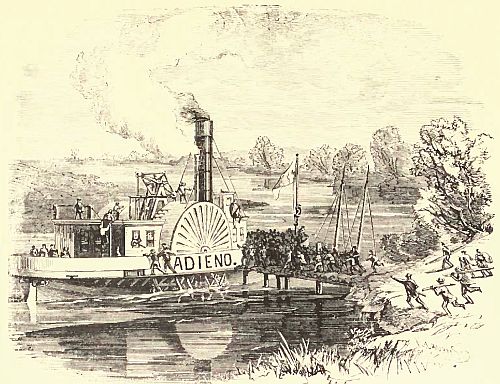

CHAPTER XX. | |

| In which Ernest takes the Wheel of the Adieno. | 222 |

CHAPTER XXI. | |

| In which Ernest continues to act as Pilot of the Steamer. | 233 |

CHAPTER XXII. | |

| In which Ernest pilots the Adieno to "The Sisters." | 244 |

CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| In which Ernest takes Command of the Expedition. | 255 |

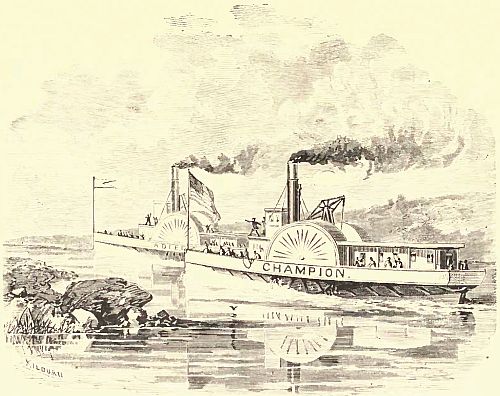

CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| In which Ernest engages in an Exciting Steamboat Race. | 266 |

CHAPTER XXV. | |

| In which Ernest pilots the Adieno to Parkville. | 277 |

CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| In which Ernest finds a Change in the Management of the Institute. | 287 |

"Ernest Thornton!" called Mr. Parasyte, the principal of the Parkville Liberal Institute, in a tone so stern and severe that it was impossible to mistake his meaning, or not to understand that a tempest was brewing. "Ernest Thornton!"

As that was my name, I replied to the summons by rising, and exhibiting my full length to all the boys assembled in the school-room—about one hundred in number.

"Ernest Thornton!" repeated Mr. Parasyte, not satisfied with the demonstration I had made.[12]

"Sir!" I replied, in a round, full, square tone, which was intended to convince the principal that I was ready to "face the music."

"Ernest Thornton, I am informed that you have been engaged in a fight," he continued, in a tone a little less sharp than that with which he had pronounced my name; and I had the vanity to believe that the square tone in which I had uttered the single word I had been called upon to speak had produced a salutary impression upon him.

"I haven't been engaged in any fight, sir," I replied, with all the dignity becoming a boy of fourteen.

"Sir! what do you mean by denying it?" added Mr. Parasyte, working himself up into a magnificent mood, which was intended to crush me by its very majesty—but it didn't.

"I have not engaged in any fight, sir," I repeated, with as much decision as the case seemed to require.

"Didn't you strike William Poodles?" demanded he, fiercely.

"Yes, sir, I did. Bill Poodles hit me in the head,[13] and I knocked him over in self-defence—that was all, sir."

"Don't you call that a fight, sir?" said Mr. Parasyte, knitting his brows, and looking savage enough to swallow me.

"No, sir; I do not. I couldn't stand still and let him pound me."

"You irritated him in the beginning, and provoked him to strike the blow. I hold you responsible for the fight."

"I had no intention to irritate him, and I did not wish to provoke him."

"I hold you responsible for the fight, Thornton," said the principal again.

I supposed he would, for Poodles was the son of a very wealthy and aristocratic merchant in the city of New York, while I belonged to what the principal regarded as an inferior order of society. At least twenty boys in the Parkville Liberal Institute came upon the recommendation of Poodle's father, while not a single one had been lured into these classic shades by the influence of my family—if I could be said to belong to any family.[14] Besides, I was but a day scholar, and my uncle paid only tuition bills for me, while most of the pupils were boarders at the Institute.

I am writing of events which took place years ago, but I have seen no reason to change the opinion then formed, that Mr. Parasyte, the principal, was a "toady" of the first water; that he was a narrow-minded, partial man, in whom the principle of justice had never been developed. He was a good teacher, an excellent teacher; by which I mean only to say that he had a rare skill and tact for imparting knowledge, the mere dry bones of art, science, and philosophy. He was a capital scholar himself, and a capital teacher; but that is the most that can be said of him.

I have no hesitation in saying that his influence upon the boys was bad, as that of every narrow-minded, partial, and unjust man must be; and if I had any boys to send away to a boarding school, they should go to a good and true man, even if I knew him to be, intellectually, an inferior teacher, rather than to such a person as Mr. Parasyte. He "toadied" to the rich boys, and oppressed the poorer[15] ones. Poodles was the most important boy in the school, and he was never punished for his faults, which were not few, nor compelled to learn his lessons, as other boys were. But I think Poodles hated the magnate of the Parkville Liberal Institute as much as any other boy.

Parkville is situated on Lake Adieno, a beautiful sheet of water, twenty miles in length, in the very heart of the State of New York. The town was a thriving place of four thousand inhabitants, at which a steamboat stopped twice every day in her trip around the lake. The academy was located at the western verge of the town, while my home was about a mile beyond the eastern line of the village.

I lived with my uncle, Amos Thornton. His residence was a vine-clad cottage, built in the Swiss style, on the border of the lake, the lawn in front of it extending down to the water's edge. My uncle was a strange man. He had erected this cottage ten years before the time at which my story opens, when I was a mere child. He had employed in the beginning, before the house was completed,[16] a man and his wife as gardener and housekeeper, and they had been residents in the cottage ever since.

I said that my uncle was a strange man; and so he was. He hardly ever spoke a word to any one, and never unless it was absolutely necessary to do so. He was not one of the talking kind; and old Jerry, the gardener, and old Betsey, the housekeeper, seemed to have been cast in the same mould. I never heard them talking to each other, and they certainly never spoke to me unless I asked them a question, and then only in the briefest manner.

I never knew what to make of my uncle Amos. He had a little room, which he called his library, in one corner of the house, which could be entered only by passing through his bedroom. In this apartment he spent most of his time, though he went out to walk every day, while I was at school; but, if he saw me coming, he always retreated to the house. He was gloomy and misanthropic; he never went to church himself, though he always compelled me to go, and also to attend the Sunday school. He did not go into society, and had little or noth[17]ing to do with, or to say to, the people of Parkville. He never troubled them, and they were content to let him alone.

As may well be supposed, my life at the cottage was not the pleasantest that could be imagined. It was hardly a home, only a stopping-place to me. It was gloom and silence there, and my uncle was the lord of the silent land. Such a life was not to my taste, and I envied the boys and girls of my acquaintance in Parkville, as I saw them talking and laughing with their fathers and mothers, their brothers and sisters, or gathered in the social circle around the winter fire. It seemed to me that their cup of joy was full, while mine was empty. I longed for friends and companions to share with me the cares and the pleasures of life.

Of myself I knew little or nothing. My memory hardly reached farther back than the advent of my uncle at Lake Adieno, and all my early associations were connected with the cottage and its surroundings. I had a glimmering and indistinct idea of something before our coming to Parkville. It seemed to me that I had once known a motherly lady[18] with a sweet and lovely expression on her face; and I had a faint recollection of looking out upon a dreary waste of waters; but I could not fix the idea distinctly in my mind. I supposed that the lady was my mother. I made several vain efforts to induce my uncle to tell me something about her; if he knew anything, he would not tell me.

Old Jerry and his wife evidently had no knowledge whatever in regard to me before my uncle brought me to Parkville. They could not tell me anything, and my uncle would not. Though I was a boy of only fourteen, this concealment of my birth and parentage troubled me. I was told that my father was dead; and this was all the information I could obtain. Where he had lived, when and where he died, I was not permitted to know. If I asked a question, my uncle turned on his heel and left me, with no reply.

The vision of the motherly lady, distant and indistinct as it was, haunted me like a familiar melody. If the person was my mother, why should her very name be kept from me? If she was still living, why could I not go to her? If she was dead,[19] why might I not water the green sod above her grave with my tears, and plant the sweetest flowers by her tombstone? I was dissatisfied with my lot, and I was determined, at no distant day, to wring from my silent uncle the particulars of my early history. I was so eager to get this knowledge that I was almost ready to take him by the throat, if need be, and force out the truth from between his closed lips.

I never had an opportunity to speak with him; but I could make the opportunity. He took no notice of me; he avoided me; he seemed hardly to be conscious of my existence. Yet he was not a hard man, in the common sense of the word. He clothed me as well as the best boys in the Institute. If I wanted anything for the table, old Jerry was ordered to procure it. When I was ten years old a little row-boat was furnished for me; but before I was fourteen I wanted something better, and told my uncle so. He made me no reply; but on my next birthday a splendid sail-boat floated on the lake before the house, which Jerry said had been built for me. I told my silent lord that I was much obliged[20] to him for his very acceptable present, when I happened to catch him on the lawn. He turned on his heel, and fled as though I had stung him with the sting of ingratitude.

If I wanted anything, I had only to mention it; and no one criticised my conduct, whatever I did. I was free to go and come when I pleased; and though in vacation I was absent three days at once in my boat, no one asked me where I had been, or what I had done. Neither my uncle nor his silent satellites ever expressed a fear that I might be drowned in my voyages in night and storm on the lake; and I came to the conclusion that no one would care if I were lost.

I do not know how, under such a home government, I ever became a decent fellow. I do not know why I am not now a pirate, a freebooter, a pickpocket, or a nuisance to myself and the world in some other capacity. I have come to believe since that my inherited good qualities saved me under such an utter neglect of all home influences. It is a marvel to me that I was not ruined before I was twenty-one; and from the deepest depths of my[21] heart I thank God for his mercy in sparing me from the fate which generally and naturally overtakes such a neglected child.

At the age of twelve, after I had passed through the common school of the town, I was admitted to the Parkville Liberal Institute, which I wished to attend because a friend of mine in the town was there. My uncle did not object—he never objected to anything. Without pride or vanity I may say that I was a good scholar, and I took the highest rank at the academy. When I was about twelve years old, some instructions which I received in the Sunday school produced a strong impression on my mind, and led me to take my stand for life. I tried to be true to God and myself, to be just and manly in all things. Whatever the world may sneeringly say of goodness and truth, I am sure that I owe my popularity among the boys of the Parkville Liberal Institute to these endeavors—not always successful—to do right.[22]

I wish to say in the beginning, and once for all, that I did not set myself up as a saint, or even as a model boy. I made no pretensions, but I did try to be good and true. I felt that I had no one in this world to rely upon for my future; everything depended upon myself alone, and I realized the responsibility of building up my own character. I do not mean to assert that I had all these ideas and purposes clearly defined in my own mind; only that I had a simple abstract desire to be good, and to do good, without knowing precisely in what the being and the doing consisted. My notions, many of them, I am now aware, were crude and undefined.

I have observed that I was a favorite among the[23] boys of the Institute, a kind of leader and oracle among them, though I was not fully conscious of the fact at the time. While I now think I owe the greater portion of the esteem and regard in which I was held by my companions to my desire to be good and true, I must acknowledge that other circumstances had their influence upon them. I was the owner of the best boat on Lake Adieno, and to the boys this was a matter of no small consequence. There were half a dozen row-boats belonging to the academy, but nothing that carried a sail.

I always had money. I had only to ask my uncle for any sum I wanted, and it was given me, without a question as to its intended use. I mention the fact to his discredit, and it would have been a luxury to me to have had him manifest interest enough in my welfare to refuse my request.

I was naturally enterprising and fearless, and was therefore foremost in all feats of daring, in all trials of skill in athletic games. Indeed, to sum up the estimate which was made of me by my associates in[24] school and the people of Parkville, I was "a smart boy." Perhaps my vanity was tickled once or twice by hearing this appellation applied to me; but I am sure I was not spoiled by the favor with which I was regarded.

Though I was not an unhappy boy, there was an aching void in my heart which I could not fill, a longing for such a home as hundreds of my young friends enjoyed; and I would gladly have exchanged the freedom from restraint for which others envied me for the poorest home in the town, where I could have been welcomed by a fond mother, where I could have had a kind father to feel an interest in me.

During the spring, summer, and autumn months, when the wind and weather would permit, I went to school in my sail-boat. My course lay along the shore, and if I was becalmed and likely to be tardy, I had only to moor my craft, and take to the road. At the noon intermission, therefore, my boat was available for use, and I always had a party.

On the day that I was called up charged with fighting, the Splash—for that was the suggestive[25] name I had chosen for my trim little craft—was lying at the boat pier on the lake in front of the Institute building. The forenoon session of the school had just closed, and I had gone to the boat to eat my dinner, which I always carried in the stern locker.

Before I had finished, Bill Poodles came down with an Arithmetic in his hand. It was the dinner hour of the boarding students, and I wondered that Bill was not in the refectory. Our class had a difficult lesson in arithmetic that day, which I had worked out in the solitude of my chamber at the cottage the preceding evening. The students had been prohibited, under the most severe penalty, from assisting each other; and it appeared that Bill had vainly applied to half a dozen of his classmates for help: none of them dared to afford it.

Bill Poodles was a disagreeable fellow, arrogant and "airy" as he was lazy and stupid. I doubt whether he ever learned a difficult task alone. The arithmetic lesson was a review of the principles which the class had gone over, and consisted of a dozen examples, printed on a slip of paper, to test the knowl[26]edge of the students; and it was intimated that those who failed would be sent down into a lower class. Bill dreaded anything like a degradation. He was proud, if he was lazy. He knew that I had performed the examples, and while his fellow-boarders were at dinner, he had stolen the opportunity to appeal to me for the assistance he so much needed.

Though Bill was a disagreeable fellow, and though, in common with a majority of the students, I disliked him, I would willingly have assisted him if the prohibition to do so had not been so emphatic. Mr. Parasyte was so particular in the present instance, that the following declaration had been printed on the examination paper, and each boy was required to sign it:—

"I declare upon my honor, that I have had no assistance whatever in solving these examples, and that I have given none to others."

Bill begged me to assist him. I reasoned with him, and told him he had better fail in the review than forfeit his honor by subscribing to a falsehood. He made light of my scruples; and then I told him[27] I had already signed my own paper, and would not falsify my statement.

"Humph!" exclaimed he, with a sneer. "You hadn't given any one assistance when you signed, but you can do it now, and it will be no lie."

I was indignant at the proposition, it was so mean and base; and I expressed myself squarely in regard to it. I had finished my dinner, and, closing the locker, stepped out of the boat upon the pier. Bill followed me, begging and pleading till I was disgusted with him. I told him then that I would not do what he asked if he teased me for a month. He was angry, and used insulting language. I turned on my heel to leave him. He interpreted this movement on my part as an act of cowardice, and, coming up behind me, struck me a heavy blow on the back of the head with his fist. He was on the point of following it up with another, when, though he was eighteen years old, and half a foot taller than I was, I hit him fairly in the eye, and knocked him over backwards, off the pier, and into the lake.

A madder fellow than Bill Poodles never floun[28]dered in shallow water. The lake where he fell was not more than two or three feet deep, and doubtless its soft bosom saved him from severe injury. He picked himself up, and, dripping from his bath, rushed to the shore. He was insane with passion. Seizing a large stone, he hurled it at me. I moved towards him, with the intention of checking his demonstration, when his valor was swallowed up in discretion, and he rushed towards the school building.

For this offence I was brought to the bar of Mr. Parasyte's uneven justice. Poodles had told his own story after changing his drabbled garments. It was unfortunate that there were no witnesses of the affray, for the principal would sooner have doubted the evidence of his own senses than the word of Bill Poodles, simply because it was not politic for him to do so. My accuser declared that he had spoken civilly and properly to me, and that I had insulted him. He had walked up to me, and placed his hand upon my shoulder, simply to attract my attention, when I had struck him a severe blow in the face, which had knocked him over backwards into the lake.[29]

In answer to this charge, I told the truth exactly as it was. Bill acknowledged that he had asked me some questions about the review lesson, which I had declined to answer. He was sorry he had offended so far, but was not angry at my refusal. He had determined to sacrifice his dinner, and his play during the intermission, to enable him to perform the examples. I persisted in the statement I had already made, and refused to modify it in any manner. It was the simple truth.

"Ernest Thornton," said Mr. Parasyte, solemnly, "hitherto I have regarded you with favor. I have looked upon you as a worthy and deserving boy, and I confess my surprise and grief at the event of to-day. Not content with the dastardly assault committed upon William Poodles,—whose devotion to his duty and his studies has been manifested by the sacrifice of his dinner,—you utter the most barefaced falsehood which it was ever my misfortune to hear a boy tell."

"I have told the truth, sir!" I exclaimed, my cheek burning with indignation.

"Silence, sir! Such conduct and such a boy[30] cannot be tolerated at the Parkville Liberal Institute. But in consideration of your former good conduct, I purpose to give you an opportunity to redeem your character."

"My character don't need any redeeming," I declared, stoutly.

"I see you are in a very unhappy frame of mind, and I fear you are incorrigible. But I must do my duty, and I proceed to pronounce your sentence, which is, that you be expelled from the Parkville Liberal Institute."

"Bill Poodles is the biggest liar in the school!" shouted a daring little fellow among my friends, who were astounded at the result of the examination, and at the sentence.

"That's so!" said another.

"Yes!" "Yes!" "Yes!" shouted a dozen more. "Throw him over! Bill Poodles is the liar!"

Mr. Parasyte was appalled at this demonstration—a demonstration which never could have occurred without the provocation of the grossest injustice. The boys were well disciplined, and the order of the Institute was generally unexceptionable. Such[31] a flurry had never before been known, and it was evident that the students intended to take the law into their own hands. They acted upon the impulse of the moment, and I judged that at least one half of them were engaged in the demonstration.

Poodles was a boy of no principle; he was notorious as a liar; and the boys regarded it as an outrage upon themselves and upon me that he should be believed, while my story appeared to have no weight whatever.

Mr. Parasyte trembled, not alone with rage, but with fear. The startling event then transpiring threatened the peace, if not the very existence, of the Parkville Liberal Institute. I folded my arms,—for I felt my dignity,—and endeavored to be calm, though my bosom heaved and bounded with emotion.

"Boys—young gentlemen, I—" the principal began.

"Throw him over! Put him out!" yelled the students, excited beyond measure.

"Young gentlemen!" shouted Mr. Parasyte.[32]

"Three cheers for Ernest Thornton!" hoarsely screamed Bob Hale, my intimate friend and longtime "crony."

They were given with an enthusiasm which bordered on infatuation.

"Will you hear me, students?" cried Mr. Parasyte.

"No!" "No!" "No!" "Throw him over!" "Put him out!"

The scene was almost as unpleasant to me as to the principal, proud as I was of the devotion of my friends. I did not wish to be vindicated in such a way, and I was anxious to put a stop to such disorderly proceedings. I raised my hand in an appealing gesture.

"Fellow-students," said I; and the school-room was quiet.[33]

"Fellow-students," I continued, when the school-room was still enough for me to be heard, "I am willing to submit to the rules of the Institute, and even to the injustice of the principal. For my sake, as well as for your own, behave like men."

I folded my arms, and was silent again. I felt that it was better to suffer than to resist, and such an exhibition of rowdyism was not to my taste. I glanced at Mr. Parasyte, to intimate to him that he could say what he pleased; and he took the hint.

"Young gentlemen, this is a new experience to me. In twenty years as a teacher, I have never been thus insulted."

This was an imprudent remark.[34]

"Be fair, then!" shouted Bob Hale; and the cry was repeated by others, until the scene of disorder promised to be renewed.

I raised my hand, and shook my head, deprecating the conduct of the boys. Once more they heeded, though it was evidently as a particular favor to me, rather than because it was in keeping with their ideas of right and justice.

"I intend to be fair, young gentlemen," continued Mr. Parasyte; "that is the whole study of my life. I am astonished and mortified at this unlooked-for demonstration. I was about to make a further statement in regard to Thornton, when you interrupted me. I told you that I purposed to give him an opportunity to redeem his character. I intend to do my duty on this painful occasion, though the walls of the Parkville Liberal Institute should crumble above my head, and crush me in the dust."

"Let her crumble!" said a reckless youth, as Mr. Parasyte waxed eloquent.

"Will you be silent, or will you compel me to resort to that which I abhor—to physical force?"

Some of the boys glanced at each other with a[35] meaning smile when this remark was uttered; but I shook my head, to signify my disapprobation of anything like resistance or tumult.

"Thornton," added Mr. Parasyte, turning to me, "I have fairly and impartially heard your story, and carefully weighed all your statements. I have come to the conclusion, deliberately and without prejudice, that you were the aggressor."

"I was not, sir," I replied, as gently as I could speak, and yet as firmly.

"It appears that Poodles placed his hand upon your arm merely to attract your attention; whereupon you struck him a severe blow in the face, which caused him to reel and fall over backward into the lake," said Mr. Parasyte, so pompously that I could not tell whether he intended to "back out" of his position or not.

"Poodles hit me in the head, and was on the point of repeating the blow, when I knocked him over in self-defence."

"It does not appear to me that Poodles, who is a remarkably gentlemanly student, would have struck you for simply refusing to assist him about his exam[36]ples. Such a course would not be consistent with the character of Poodles."

"No, sir, I did not strike him at any time," protested Poodles.

"I find it impossible to change my opinion of the merits of this case; and for the good of the Parkville Liberal Institute, I must adhere to the sentence I have already—with regret and sorrow—pronounced upon you. But—"

There were again strong signs of another outbreak among the pupils, and I begged them to be silent.

"The conduct of Thornton in this painful emergency merits and receives my approbation. His love of order and his efforts to preserve proper decorum in the school-room are worthy of the highest commendation," continued Mr. Parasyte; "and I would gladly remit the penalty I have imposed upon him without any conditions whatever; but I feel that such a course, after the extraordinary events of this day, would be subversive of the discipline and good order which have ever characterized the Parkville Liberal Institute. I shall, however, impose a merely nominal condition upon Thornton, his compliance[37] with which shall immediately restore him to the full enjoyment of his rights and privileges as a member of this academy. I wish to be as lenient as possible, and, as I observed, the penalty will be merely nominal.

"As the quarrel occurred when the parties were alone, so also may the reparation be made in private; for after Thornton's magnanimous behavior to-day, under these trying circumstances, I do not wish to humiliate or mortify him. I wish that it were consistent with my ideas of stern duty to impose no penalty."

Mr. Parasyte had certainly retreated a long way from his original position. I did not wish to be expelled, and I hailed with satisfaction his manifestation of leniency; and rather than lose the advantages of the school, I was willing to submit to the nominal penalty at which he hinted, supposing it would be a deprivation of some privilege.

"I have not resisted your authority, sir; and I do not mean to do so now," I replied, submissively; for, as the popular sentiment of the students sustained me, I could afford to yield.[38]

"Your conduct since the quarrel is entirely satisfactory; I may say that it merits my admiration." This was toadying to the boys, whom he feared. "I have sentenced you to expulsion, the severest penalty known in the discipline of the Parkville Liberal Institute; but, Thornton, I propose to remit this penalty altogether on condition that, in private, and at your own convenience, but within one week, you apologize to Poodles for your conduct. I could not make the condition any milder, I think."

Mr. Parasyte smiled as though he had entirely forgiven me; as though he had, in some mysterious manner, wiped out the stains of falsehood upon my character. I bowed, but made no reply. I was sentenced to expulsion; but the penalty was to be remitted on condition that I would apologize to Poodles.

Apologize to Poodles! For what? For his attack upon me, or for the lies he had told about me? It was no more possible for me to apologize for knocking him over when he assailed me than it would have been for me to leap across Lake Adieno in the widest place. I did not wish to deprive myself of[39] the advantages of attending the Parkville Liberal Institute; but if my remaining depended upon my humiliating myself before Poodles, upon my declaring that what I had done was wrong, when I believed it was right, I was no longer to be a student in the academy.

The exercises of the school proceeded as usual for a couple of hours, and there were no further signs of insubordination among the boys. At recess I purposely kept away from my more intimate friends, for I did not wish to tell them what course I intended to pursue, fearful that it would renew the disturbance.

An hour before the close of the session, the boys were required to bring in their examination papers in arithmetic. Every student, even to Poodles, handed in solutions to all the problems, and Mr. Parasyte and his assistants at once devoted themselves to the marking of them. In half an hour the principal was ready to report the result.

Half a dozen of the class had all the examples right, and I was one of the number. Very much to my astonishment, Poodles also was announced as one[40] of the six; and when his name was mentioned, a score of the students glanced at me.

I did not understand it. I was quite satisfied that Poodles could not do the problems himself, and it was certain that he had obtained assistance from some one, though the declaration on the paper was duly signed. He had found a friend less scrupulous than I had been. Some one must have performed the examples for him; and as he had them all correct, it was evident that one of the six, who alone had presented perfect papers, must have afforded the assistance. After throwing out Poodles and myself, there were but four left; and two of these, to my certain knowledge, had joined in the demonstration in my favor: indeed, they were my friends beyond the possibility of a doubt. Between the other two I had no means of forming an opinion.

During the afternoon Mr. Parasyte had been very uneasy and nervous. It was plain to him that he ruled the boys by their free will, rather than by his own power; and this was not a pleasant thing for a man like him to know. Doubtless he felt that he[41] had dropped the reins of his team, which, though going very well just then, might take it into its head to run away with him whenever it was convenient. Probably he felt the necessity of doing something to reëstablish his authority, and to obtain a stronger position than that he now occupied. If, with the experience I have since acquired, I could have spoken to him, I should have told him that justice and fairness alone would make him strong as a disciplinarian.

"Poodles," said Mr. Parasyte, just before the close of the session, "I see that all your examples were correctly performed, and that you signed the declaration on the paper."

"Yes, sir," replied Poodles.

"When did you perform them?"

"I did all but two of them last night."

"And when did you do those two?" continued the principal, mildly, but with the air of a man who expects soon to make a triumphant point.

"Between schools, at noon, while the students were at dinner and at play."[42]

"Very well. You had them all done but two when you met Thornton to-day noon?"

"Yes, sir."

"Thornton," added Mr. Parasyte, turning to me, "I have no disposition to hurry you in the unsettled case of to-day, though the result of Poodles's examination shows that he had no need of the assistance you say he asked of you; but perhaps it would be better that you should state distinctly whether or not you intend to apologize. It is quite possible that there was a misunderstanding between you and Poodles, which a mutual explanation might remove."

"I do not think there was any misunderstanding," I replied.

"If you wish to meet Poodles after school, I offer my services as a friend to assist in the adjustment of the dispute."

"I don't want to meet him," said Poodles.

Mr. Parasyte actually rebuked him for this illiberal sentiment; and while he was doing so, I added that I had no desire to meet Poodles, as proposed. I now think I was wrong; but I had a feeling that[43] the principal intended to browbeat me into an acknowledgment.

"Very well, Thornton; if you refuse to make peace, you must take the consequences. Do you intend to apologize to Poodles, or not?"

"I do not, sir," I replied, decidedly.

"Then you are expelled from the Parkville Liberal Institute."[44]

Difficult as the task was, I had thus far kept cool; but my sentence fell heavily upon me, and I could not help being angry, for I felt that I had been treated unfairly and unjustly. Poodles's statement had been accepted, and mine rejected; his word had been taken, while mine, which ought at least to have passed for as much as his, was utterly disregarded.

I turned upon my heel and went to my seat. My movement was sharp and abrupt, but I did not say anything.

"Stop!" said Mr. Parasyte, who evidently believed that the moment had come for him to vindicate his authority.

I did not stop.[45]

"Stop, I say!" repeated the principal.

I proceeded to pick up my books and papers, to enable me to comply literally with my sentence.

"Come here, Thornton."

I took no notice of the order, but continued to pack up my things.

"Do you hear me?" demanded Mr. Parasyte, in a loud and angry tone.

"I do hear you, sir. I have been expelled, and I don't care about listening to any more speeches."

"If you don't come here, I'll bring you here," added the principal, with emphasis.

Somewhat to my surprise, but greatly to my satisfaction, the boys made no demonstration in my favor. They seemed to think I was now in a mood to fight my own battle, though they were doubtless ready to aid me if I needed any help. Mr. Parasyte appeared to have begun in a way which indicated that he intended to maintain his authority, even at the risk of a personal encounter with me and the boys who had voluntarily espoused my cause.

Having packed up my books and papers, I took the bundle under my arm, and deliberately walked[46] out of the school-room. The principal ordered me to stop; but as he had already sentenced me to expulsion, I could see no reason why I should yield any further allegiance to the magnate of the institution. He was very angry, which was certainly an undignified frame of mind for a gentleman in his position; and I was smarting under the wrong and injustice done to me. Mr. Parasyte stopped to procure his hat, which gave me the advantage in point of time, and I reached the little pier at which my boat was moored before he overtook me.

I hauled in the painter, and pushed off, hoisting the mainsail as the boat receded from the wharf. Mr. Parasyte reached the pier while I was thus engaged.

"Stop, Thornton!" shouted he.

"I would rather not stop any longer," I replied, running up the foresail.

"Will you come back, or I shall bring you back?" demanded he, fiercely.

"Neither, if you please."

"If you wish to save trouble, you will come back," said he.[47]

"I'm not particular about saving trouble. If you have any business with me, I will return."

"I have business with you."

"Will you please to tell me what it is?"

"No, I will not."

"Then you will excuse me if I go home," I added, as I hoisted the jib.

There was only a very light breeze, and the Splash went off very slowly. I took my seat at the helm, trying to keep as cool as possible, though my bosom bounded with emotion. I was playing a strange part, and I was not at home in it. I could not help feeling that I was riding "a high horse;" but the injustice done me seemed to warrant it.

"Poodles, call the men," I heard Mr. Parasyte say to his flunky, and saw him run off to execute the command.

"Once more, Thornton, I ask you to come back," said the principal, still standing on the pier, from which the Splash had receded not more than a couple of rods.

"If you have any business with me, sir, I will do so," I replied. "You have expelled me from the[48] school, and I don't think you have anything more to do with me."

"I want no words or arguments. It will be better for you to come back."

"Perhaps it will; but I shall not come."

There was not breeze enough to enable me to make a mile an hour, and I had some doubts in regard to the result, if Mr. Parasyte persisted. He did persist, and presently Poodles returned with two men, who were employed upon the school estate, and whose services were so often required in the boats that they were good oarsmen. I comprehended the principal's plan at once. He intended to chase me in the boat, and bring me back by force. I was rather amused at the idea, and should have been more so if there had been a fair sailing breeze.

The Splash was the fastest boat on the lake, or, at least, faster than any with which I had had an opportunity to measure paces. But it made but little difference how fast she was, as long as there was hardly wind enough to stiffen the mainsail. Mr. Parasyte ordered the men to take their places on the thwarts, and ship their oars. I saw that a[49] little farther out from the shore there was a ripple on the water, and putting one of my oars out at the stern, I sculled till I caught the breeze, and the Splash went off at a little livelier pace.

By this time all the boys had gathered on the bank of the lake to see the fun, and it was fun to them. I knew that their sympathies were with me, and I only wished for a better breeze, that I might do justice to myself and to my boat. But the chances for me were improving as the Splash receded from the shore. Mr. Parasyte had taken his place in the stern sheets of the row-boat, and was urging forward the men at the oars, who were now pulling with all their might. I could not conceal from myself the fact that they were gaining rapidly upon me. Unless the wind increased, I should certainly be captured; for the two men with the principal would ask no better sport than to overhaul and roughly handle an unruly boy.

But the wind continued to increase as I went farther out upon the lake, and I soon had all that was necessary to enable me to keep a "respectful distance" between the Splash and the row-boat. By[50] this time my anger had abated, and I had begun to enjoy the affair. With a six-knot breeze I could have it all my own way. I could still see the boys on the shore, watching the chase with the liveliest interest and satisfaction. They were not silent observers, for an occasional cheer or shout was borne to my ears over the lake, and I could see the waving of hats, and the swinging of arms, with which my friends encouraged me to persevere.

Mr. Parasyte was resolute. He felt, doubtless, that the reputation of the Parkville Liberal Institute, and his own reputation as a disciplinarian, were at stake. The tumult in the school-room early in the afternoon would weaken his power and influence over the boys, unless its effects were counteracted by a triumph over me. Right or wrong, he probably felt that he must put me down, or be sacrificed himself; and he continued to urge his oarsmen forward, intent upon capturing and subduing me.

While I had the breeze I felt perfectly easy. I had stood out from the shore with the wind on the beam, and there was nothing to prevent my running before it directly to the cottage of my uncle. I was[51] disposed to tantalize my pursuer, and wear out his men. I knew that my silent guardian would not thank me for leading Mr. Parasyte into his presence, and I was willing to gratify him in this instance. Besides, the students on the shore seemed to derive too much enjoyment from the scene to have the sport cut short. Hauling aft the sheets, I stood down the lake, close to the wind, until I had brought my pursuer astern of me. I then brought the Splash up into the wind, and coolly waited for the row-boat to come up within hailing distance.

Mr. Parasyte, deceived by my position, thought his time had come. He was much excited, and with renewed zeal pressed his oarsmen to increase their efforts. When he had approached within a few rods of me, I put up the helm, and dashed away again towards the pier. Again I distanced him, and ran as near to the pier as I dared to go, fearful that I might lose the wind under the lee of a bluff below the school grounds. The boys hailed me with a cheer, which must have been anything but soothing to the feelings of Mr. Parasyte. Then, "wing and wing," I ran off before the wind; and, still unwilling[52] to deprive my friends of the excitement of witnessing the race, I again stood out towards the middle of the lake.

The principal could not give up the pursuit without abandoning the high position he had taken, and subjecting himself to the derision of the students. He followed me, therefore, and I led him over the same course he had gone before. On my return I unfortunately ran in a little too near the shore, and got under the lee of the bluff, which nearly becalmed me. I realized that I had made a fatal blunder, and I wished I had disappointed the boys, and continued on my course across the lake, where the wind favored me. I tried to scull the Splash out of the still water before Mr. Parasyte came up.

"Pull with all your might, men!" said the principal, excitedly; and they certainly did so.

Seeing that he was upon me, I attempted to come about, and run off before the wind; but I had lost my steerage-way. I suppose I was somewhat "flurried" by the danger of my situation, and did not do as well as I might have done.

"Pull! Pull!" shouted Mr. Parasyte, nervously, as he steered the row-boat.[53]

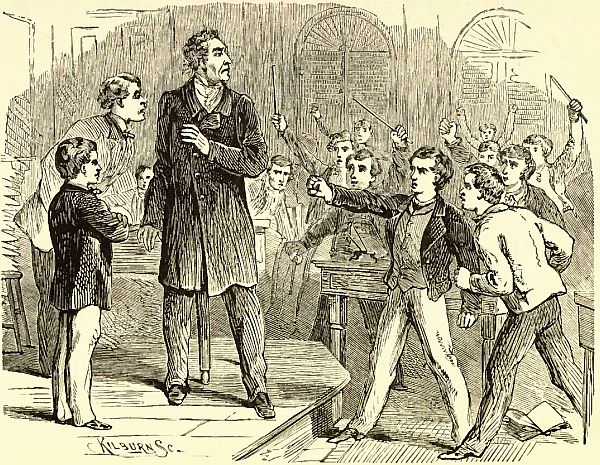

Thus urged, the men did pull better than I had ever known them to do before. The principal of the Parkville Liberal Institute was no boatman himself, and his calculations were miserably deficient, or else his intentions were more vicious than I had given him credit for. He was angry and excited; and as I looked at him, it seemed to me that he did not know what he was about. The Splash lay broadside to him. She was a beautiful craft, built light and graceful, rather than strong and substantial. On the other hand, the row-boat was a solid, sharp, ram-nosed craft, setting low in the water; and on it came at the highest speed to which it could be urged by the powerful muscles of the strong men at the oars.

"Pull! Pull!" repeated Mr. Parasyte, fiercely, under the madness of the excitement and the resentment caused by the hard chase I had led him.

"Down with your helm, or you will smash me!" I shouted, seeing that a collision was inevitable.

If Mr. Parasyte did not intend to run me down, my warning was too late. The row-boat came upon me like a whirlwind, striking the Splash on the[54] beam, below her water-line, and staving in her side as though she had been a card box. I do not know whether this was a part of the principal's programme or not; but my boat was most effectually smashed, and, being heavily ballasted, she went down like a rock. It was hardly an instant after the shock before I felt her sinking beneath me. The two men at the oars of the principal's boat, without any order from Mr. Parasyte,—for he knew not what to do,—backed water. I could swim like a fish; and as the Splash sank beneath me, I struck out from the wreck, and was left like a waif floating upon the glassy surface of the lake.

Ernest sails the Splash and takes a Bath. Page 54.

Ernest sails the Splash and takes a Bath. Page 54.

The battle had been fought and lost to me. Mr. Parasyte, roused to the highest pitch of anger and excitement, seemed to be determined to overwhelm me. He was reckless and desperate. He had smashed my boat apparently with as little compunction as he would snap a dead stick in his fingers. He was thoroughly in earnest now; and it was fully demonstrated that he intended to protect the discipline of the Parkville Liberal Institute, even if it cost a human life for him to do so.

I was then "lying round loose" in the lake. I had no idea that I was in any personal peril from the water; all that disturbed me was the fact that I could not swim fast enough to keep out of the principal's way. The treacherous breeze had deserted me in the midst of my triumph, and consigned me to the tender mercies of my persecutor.[56]

I swam away from the boat which had been pursuing me, as though from an instinct which prompted me to escape my oppressor; but Mr. Parasyte, without giving any attention to my sinking craft, ordered his men to pull again; and he steered towards me. Of course a few strokes enabled him to overtake me. If I had had the means, I would have resisted even then, and avoided capture; for I could easily have swum ashore. But it would have been childish for me to hold out any longer; and when one of the men held out his oar to me, I grasped it, and was assisted into the boat.

"Are you satisfied, Thornton?" said Mr. Parasyte, with a sneer, as I shook myself like a water dog, and took my seat in the boat.

"No, sir; I am not satisfied," I replied.

"What are you going to do about it?"

"I don't know about that; I will see in due time."

"You will see in due time, I trust, that the discipline of the Parkville Liberal Institute is not to be set at defiance with impunity."

"I have not set the discipline at defiance. I sub[57]mitted myself, and did what I could to make others do so. You can't say that I did anything wrong while I was a member of the academy. You turned me out, and I was going quietly and in order, when you began to browbeat me."

"I ordered you to come to me, and you did not come. That was downright disobedience."

"It was after you had turned me out; and all I had to do was to go."

"You were still on my premises, and were subject to my orders."

"I don't think I was."

"I shall not argue the matter with you. I am going to teach you the duty of obedience."

"Perhaps you will; but I don't believe you will," I replied, in a tone of defiance.

"We'll see."

"There's another thing we'll see, while we are about it; and that is, you will pay for smashing my boat."

"Pay for it!" exclaimed he.

"I think so."

"I think not."[58]

"You will, if there is any law in the land."

"Law!" ejaculated he; but his lips actually quivered with anger at the idea of such an outrage upon his magnificent dignity, as being sued, and compelled in a court of justice to pay for the boat he had destroyed.

"You had no right to run into my boat—no more right than I had to set your house on fire."

"We will see."

He relapsed into a dignified silence; but he was thinking, I fancy, how very pleasant it would be for him to pay three or four hundred dollars for the Splash; not that he would care much for the money, but it would make him appear so ridiculous in the eyes of the students.

The men were pulling for the shore; but I observed that Mr. Parasyte did not head the boat towards the pier, where the boys were waiting our return. Probably he feared that they would attempt to resist his mighty will, and deliver me from his hands. He intended, therefore, to land farther down the lake, and convey me to the Institute buildings by some unfrequented way.[59]

For my own part, I was not much disturbed by Mr. Parasyte's intentions or movements. The only thing that really distressed me was the loss of my boat; for the Splash had been one of my best and dearest friends. I was a little sentimental in regard to her; and her destruction gave me a pang of keen regret akin to anguish. I had cruised all over the lake in her; had eaten and slept in her for a week at a time, and I actually loved her. She was worthy to be loved, for she had served me faithfully in storm and sunshine. It is quite likely that I had some feelings of revenge towards the tyrant who had crushed her, and I was thinking how he could be compelled to pay for the damage he had done.

As soon as I had, in a measure, recovered my equanimity, I tried to obtain the bearings of the spot where the Splash had disappeared beneath the waters, so that, if I failed to obtain justice, I might possibly recover my boat. If raised, she was in very bad condition; for her side was stove in, and I feared she could not be repaired so as to be as good as she was before.[60]

As the row-boat neared the shore, I made my preparations to escape from my captor; for it was not my intention to be borne back in triumph to the Institute, as a sacrifice to the violated discipline of the establishment. When the boat touched the beach, I meant to jump into the water, and thus pass the men, who were too powerful for me. I changed my position so as to favor my purpose; but Mr. Parasyte had been a schoolmaster too many years not to comprehend the thought which was passing through my mind. He picked up the boat-hook, and it was clear to me that he intended with this instrument to prevent my escape.

The boat was beached; but I saw no good chance to execute my purpose, and was forced to wait till circumstances favored me. The spot where we had put in was over two miles distant from the Institute by the road, though not more than one by water. Mr. Parasyte directed one of the men to go to a stable, near the shore, and procure a covered carriage, compelling me to keep my seat in the stern of the boat near him, while the messenger was absent. He still held the boat-hook in his hand,[61] with which he could fasten to me if I made any movement.

When the vehicle came, the principal placed me on the back seat, and took position himself at my side. One of the men was to drive, while the other was directed to await his return, and then pull the boat back. I was forced to acknowledge to myself that Mr. Parasyte's strategy was excellent, and that I was completely baffled by it; but as I was satisfied that my time would soon come, I was content to submit, with what patience I could command, to the captivity from which I could not escape.

The vehicle was driven to the front door of the Institute; and the boys, who were still on the shore of the lake, watching for the return of the boat, did not have any notice of the arrival of the prisoner. I was conducted to the hall of the principal's apartments first, and then to a vacant chamber on the third floor. Mr. Parasyte performed this duty himself, being unwilling to intrust my person to the care of one his subordinate teachers. A suit of clothes belonging to a boy of my own[62] size was sent to me, and I was directed to put it on, while my own dress was dried at the laundry fire. This was proper and humane, and I did not object.

When I had changed my clothing, Mr. Parasyte presented himself. By this time he had thoroughly cooled off. He looked solemn and dignified as he entered the little room, and seated himself in one of the two chairs, which, with the bed, formed the furniture of the apartment. He had probably considered the whole subject of his relations with me, and was now prepared to give his final decision, to which I was also prepared to listen.

"Thornton," said he, with a kind of jerk in his voice.

"Sir."

"You have made more trouble in the Parkville Liberal Institute to-day than all the other boys together have made since the establishment was founded."

"I didn't make it," I replied, promptly, intending to give him an early assurance that I would not recede from the position I had taken.[63]

"Yes, you did. You provoked a quarrel, and refused to apologize—a very mild penalty for the offence you had committed."

"I deny that I provoked a quarrel, sir."

"That question has been settled, and we will not open it again. I have shown the students, by my prompt pursuit of you when you set my authority at defiance, that I intended to maintain the discipline of this institution. I have taken you and brought you back. So far I am satisfied, Thornton."

"I am not. You have smashed my boat, and you must pay for her," I added, calmly, but in the most uncompromising manner.

"This is not a matter of dollars and cents with me. I would rather have given a thousand dollars than had this trouble occur; and I would give half that sum now to have it satisfactorily settled."

Mr. Parasyte wiped his brow, for he was thrown into a violent perspiration by the mental effort which this acknowledgment caused him. It looked like "backing out."

"Thornton, you are a very popular young man among the students; it would be useless to deny[64] it, if I were disposed to do so. You have the sympathies of your companions, because Poodles is not popular."

"The boys don't like Poodles simply because he is not a good fellow. He is a liar and a cheat, and—"

"Nothing more of that kind need be said. What I have done cannot be undone."

"Very well, sir; I have been expelled. Let me go; that's all I ask."

"In due time you will have permission to go. I think I am, technically, legally liable for the destruction of your boat," he added, wiping his brow again; for it was hard work for him to say so much. "But you have defied me, and the well-being of this institution required that I should act promptly. I wish to make a proposition to you."

He paused and looked at me. I intimated that I was ready to hear him.

"In about an hour the boys will assemble for evening prayers," he continued, after rising from his chair and consulting his watch. "If at that time you will apologize to me for your conduct, in their[65] presence, and before that time to Poodles, privately, I will restore you to your rank and privileges in the Parkville Liberal Institute, and—and pay you for your boat."

"I will not do it, sir," I replied, without an instant's hesitation.

Mr. Parasyte gave me a glance of mingled anger and mortification, and turning on his heel, left the room, locking the door upon me.[66]

To apologize to Poodles was to acknowledge that I had done wrong. Had I done wrong so far as my fellow-student was concerned? Seriously and earnestly I asked myself this question. No; I had told the truth in regard to the affair exactly as it was, and it would be a lie for me to apologize to Poodles. I could not and would not do it. I would be cut to pieces, and have my limbs torn piecemeal from my body before I would do it.

As far as the principal was concerned, I felt that, provoked and irritated by his tyranny and injustice, I had exhibited a proud and defiant spirit, which was dangerous to the discipline of the school. I was sorry that, when he called me back, I had not[67] obeyed. While I was in the school-room, or on the premises of the academy, I should have yielded obedience, both in fact and in spirit; and I could not excuse my defiant bearing by the plea that I had been expelled. I was willing, after reflection, to apologize to Mr. Parasyte.

He proposed to pay for my boat. This was a great concession on his part, though it was called forth by the belief that he was legally liable for its destruction. He was willing to do me justice in that respect, if I would humiliate myself before Poodles, and publicly heal the wound which the discipline of the Institute had received at my hands. Even at that time it seemed to me to be noble and honorable to acknowledge an error and atone for it; and I am quite sure, if I could have felt that I had done wrong, I should have been glad to own it, and to make the confession in the presence of the students. There was a principle at stake, and something more than mere personal feeling.

While I was debating with myself what I should do, Mr. Parasyte appeared again. It was a matter of infinite importance to him. The prosperity, if not[68] the very existence, of his school depended upon the issue of this affair; and he was naturally nervous and excited. The students were in a state of incipient rebellion, as their conduct in the afternoon indicated, and it was of the highest moment to the Institute to have the matter amicably adjusted.

On the one hand, if I apologized to Poodles and the principal, the "powers that be" would be vindicated, and the authority of the master fully established. On the other hand, if I declined to do so, and the sentence of expulsion was carried out, the boys were in sympathy with me, and the rebellion might break out afresh, and end in the total dissolution of the establishment. Under these circumstances, it was not strange that Mr. Parasyte desired to see me again.

"I hope you have carefully considered your position, Thornton," said he.

"I have," I replied; "and I am willing to apologize to you, but not to Poodles."

"That is something gained," added he; and I could see his face brighten up under the influence of a hope.[69]

"My manner was defiant, and my conduct disobedient. I am willing to apologize to you for this, and to submit to such punishment as you think proper to inflict."

"That is very well; but it does not fully meet the difficulty. You must also apologize to Poodles, which you are aware may be done in private."

"I cannot do it, sir, either in public or in private. Poodles was wholly and entirely to blame."

"I think not; when I settled the case it was closed up, and it must not be opened again; at least not till some new testimony is obtained. I cannot eat my own words."

"You may obtain new testimony, if you desire," I suggested.

"What?"

"Poodles signed the declaration that he had performed the examples on the papers without assistance."

"He did. Have you any doubt that such is the case?" asked Mr. Parasyte, though he must have been satisfied that Poodles did not work out the examples.[70]

"I am entirely confident that he did not perform them. Mr. Parasyte," I continued, earnestly, "I desire to stay at the Institute. It would be very bad for me to be turned out, and I am willing to confess I have done wrong. If you give Poodles the paper with the examination on it, and he can perform one half of the examples, even now, without help, I will apologize to him in public or in private."

"That looks very fair, but it is not," replied the principal, rubbing his head, as if to stimulate his ideas.

"If Poodles can do the problems, I shall be willing to believe that I am mistaken. In my opinion, he cannot perform a single one of them, let alone the whole of them."

"I object to this proceeding," said he, impatiently. "It will be equivalent to my making a confession."

The bell rang for the boys to assemble for the evening devotions. It gave Mr. Parasyte a shock, for the business was still unsettled. I had submitted to him a method by which he could ascertain the truth or falsehood of Poodle's statements; but it involved an[71] acknowledgment that he, Mr. Parasyte, was in the wrong. He seemed to be afraid it would be proved that he had made a blunder; that he had given an unjust judgment. I was fully aware that the principal's position was a difficult and painful one, and I was even disposed to sympathize with him to a certain extent, though I was the victim of his partiality and injustice. The perils and discomforts of his situation, however, had been produced by his own hasty and unfair judgment; and it would have been far better for him even to apologize to me. He would have lost nothing with the boys by such a course; for never in my life did I have so exalted an opinion of a schoolmaster, as when, conscious that he had done wrong, he nobly and magnanimously acknowledged his error, and begged the forgiveness of the boy whom he had unintentionally misjudged.

I feel bound to say, in this connection, and after a longer experience of the world, that many schoolmasters, "armed with a little brief authority," are the most contemptible of petty tyrants. Their arrogance and oppression are intolerable; and I have often[72] wondered, that where such men have been planted, they have not produced more of the evil fruit of strife and rebellion. Mr. Parasyte was one of this class; and the fact that he was a splendid teacher did not help his influence in the slightest degree.

"There is the bell for evening prayers, Thornton, and it is necessary for me to know instantly what you intend to do," said the principal.

"I shall not apologize to Poodles; I will to you."

"Think well of it."

"I have done so. If Poodles can do one half the examples on the paper, I will apologize."

"I have decided that question, and shall not open it again."

"I have nothing more to say, Mr. Parasyte," I replied, with becoming dignity, as I braced myself for the consequences of the decision I had made.

"You are an obstinate and self-willed fellow!" exclaimed the principal, irritated by the result.

I made no reply.

"The consequences be upon your own head."

I bowed in silence.[73]

"You have lost your good character and your boat."

I glanced out of the window, and saw the boys filing into the school-room.

"I shall explain this matter to your fellow-students, and tell them what I proposed."

"Do so," I answered.

He could not help seeing that I was thoroughly in earnest, and that I did not intend to yield any more than I had indicated. He was vexed, annoyed, angry, and bolted out of the room, at last, in no proper frame of mind to conduct the religious exercises of the hour. It was quite dark now; and I lay down upon the bed, to think of what had passed, and to conjecture the result of my conduct. How I sighed then for some kind friend to advise me! How I wished that I had a father who would tell me what to do, and fight my battle for me! How I longed for a tender mother, into whose loving face I could gaze as I related the sad experience of that eventful day! Perhaps she would bid me apologize to Poodles, for the sake of saving my good name, and retaining my con[74]nection with the school. If so, though it would be weak and unworthy, I could humble myself for her sake.

I felt that I had done right. I had made all the concession which truth and justice required of me, and I was quite calm. I hardly inquired why Mr. Parasyte was keeping me a prisoner in the Institute after he had expelled me, or what he intended to do with me. About nine o'clock my own clothes were brought back to me by one of the servants; but the door was securely locked when he retired.

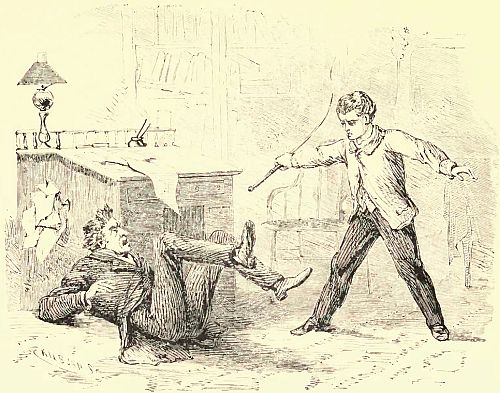

A few minutes later, and before the sound of the servant's retreating footsteps had ceased, I heard some one thrust a key into the door. It did not fit, and a dozen others were tried in like manner, but with no better success. I heard a whispered consultation; and then the door began to strain, and crack, until the bolt yielded, and it flew open. My sympathizing friends, the students, headed by Bob Hale, had broken it down.

"Come, Ernest," said Bob. "You needn't stay in here any longer. We want you down stairs."[75]

"What are you going to do?" I asked, quietly, of my excited deliverers.

"There is no law or justice in this concern; and we are going to put things to rights," replied Tom Rush, a good fellow, who had spent a week's vacation with me circumnavigating Lake Adieno in the Splash.

"You know I don't approve of any rows or riots," I added.

"No row nor riot about it. We have taken possession of this establishment, and we are going to straighten things out,—you can bet your life on that."

"Where is Mr. Parasyte?"

"He has gone up to see your uncle. He told us, at evening prayers, what an obstinate boy you were; how kind, and tender, and forgiving he had been to you, and how he had exhausted good nature in trying to bring you to a proper sense of duty."

"Did he say that?"

"He did, and much more. But come with us. The fellows have captured the citadel, and we hold the school-room now, waiting for you."[76]

"I will go with you; but I don't want the fellows to make a disturbance."

"No disturbance at all, Ernest; but we have turned the assistant teachers out, and mean to ascertain who is right and who is wrong in this matter."

The rebellion had actually broken out again; and the students, in the most high-handed manner, had established a tribunal in the school-room, to try the issue of my affair with the principal. I followed Bob Hale, Tom Rush, and half a dozen others, who constituted the committee to wait on me. They conducted me to the main school-room, which was a large hall. At every door and window were stationed two or three of the larger boys, with their hockies, bats, and rulers as weapons, to defend the court, as they called it, from any interruption.

About two thirds of the students were there assembled; and though the gathering was a riotous proceeding, the boys were in as good order as during the sessions of the school. In an arm-chair, on the platform, sat Henry Vallington, one[77] of the oldest and most dignified students of the Institute, who, it appeared, was to act as judge. Before him were Bill Poodles and Dick Pearl,—the latter being one of the six whose examples were all right,—arraigned for trial, and guarded by four stout students.[78]

I confess that I was appalled at the boldness and daring of my fellow-students, who had actually taken possession of the Parkville Liberal Institute, and purposed to mete out justice to me and to Bill Poodles. There was a certain kind of solemnity in the proceedings, which was not without its effect upon me. My companions were thoroughly in earnest, and the affair was not to be a farce.

Mr. Parasyte, after prayer, had made a statement to the students in regard to the unpleasant event of the day, in which he represented me as a contumacious offender, one who desired to make all the trouble he could; an obstinate, self-willed fellow, whose example was dangerous to the general[79] peace, and who had refused to be guided by reason and common sense. He told the students that he had even offered to pay for my boat—a concession on his part which had had no effect in softening my obdurate nature. He appealed to them to sustain the discipline of the Parkville Liberal Institute, which had always been celebrated as a remarkably orderly and quiet establishment. He then added that he should consult my uncle in regard to me, and be guided in some measure by his judgment.

The students heard him in silence; but Bob Hale assured me that it was with compressed lips, and a fixed determination to carry out the plan which had been agreed upon while the boys were watching the chase on the lake, and which had not been modified by the wilful destruction of the Splash.

I glanced around at my fellow-students as I entered the hall; and though they smiled as their gaze met mine, there was a look of earnestness and determination which could not be mistaken. Henry Vallington, the chairman, judge, or whatever the name of his office was, had the reputation of being[80] the steadiest boy in the school. It was understood that he intended to become a minister. He was about eighteen, and was nearly fitted to enter college. He never joined in what were called the "scrapes" of the Institute, but devoted himself with the closest attention to his studies. He was esteemed and respected by all who knew him; and when I saw him presiding over this irregular assemblage, I could not help regarding the affair as much more serious than it had before seemed, even to me, the chief actor therein.

Poodles and Pearl, I learned, had been captured in their rooms, and dragged by sheer force into the school-room, to be examined on the charges to be preferred against them. Poodles looked timid and terrified, while Pearl was dogged and resolute.

"Thornton," said Henry Vallington, as my conductors paused before the judge, "I have sent for you in order that we may ascertain the truth of the charges brought against you by Mr. Parasyte. If you provoked the quarrel to-day noon with Poodles, it is no more than fair and right that you should make the apology required of you. If[81] you did not, we intend to stand by you. Have you anything to say?"

"I wish to say, in the first place, that, guilty or innocent, I am willing to submit to whatever penalty the principal imposes upon me."

"That is very well for you, but it won't do for us," interposed the judge. "If such gross injustice is done to one, it may be to another. We act in self-defence."

"I don't know what you intend to do; but I am opposed to any disorderly conduct, and to any violation of the rules of the Institute."

"We know you are, Thornton; and you shall not be held responsible for what we do to-night. If you are willing to tell us what you know about this affair, all right. If not, we shall go on without you."

"I am willing to tell the truth here, as I have done to-day. As there seems to be some mistake in regard to what transpired between Mr. Parasyte and myself, up stairs, I will state the facts as they occurred. He agreed to pay for my boat on condition that I would apologize, privately, to Poodles,[82] and publicly to the principal. I offered to apologize to Mr. Parasyte, but not to Poodles, who was the aggressor in the beginning. I told him, if Poodles would perform half the examples now, I would make the apology to him."

"That's it!" shouted half a dozen boys.

"Order!" interposed the judge, sternly.

"I think that would be a good way to prove that Poodles did or did not tell the truth, when he said he had performed the examples," interposed Bob Hale.

"Capital!" added Tom Rush.

"I approve the method; but let us have no disorder," replied Vallington. "Conduct Poodles to the blackboard."

The custodians of the culprit promptly obeyed this order, and led him to the blackboard, which was cleaned for immediate use. The school-room was well lighted, and the expression on the faces of all could be distinctly seen.

"Poodles, we desire to have justice done to all," said Vallington, when the culprit had taken his place at the blackboard. "You shall have fair play[83] in every respect. You shall have a chance to prove that you were right, and Thornton wrong."

"Well, I was right," replied Poodles.

"Did you perform all the examples on your paper without any help?"

"Of course I did."

"Then of course you know how to perform them. Here is an examination paper. If you can perform five of the ten examples you shall be acquitted."

"Perhaps I don't choose to do them," said Poodles, looking around for some way to escape his fate.

"Are you not willing that the truth should come out?"

"I told the truth to-day."

"All right, if you did. You surely will not object to prove that you did. You shall have fair play, I repeat."

"Suppose I don't choose to do them?" asked Poodles, doubtfully.

"Then we shall take it for granted that you did not do them, as you declared on your paper."[84]

"You can take it for granted, then, if you like," answered Poodles, as he dropped the chalk.

"You refuse to perform the examples—do you?" demanded Vallington, sternly.

"Yes, I do."

"Then you may take the consequences. Either you shall be expelled from the Institute, or at least fifty of us will petition our parents to take us from this school. We have done with you."

Bill Poodles smiled, and was pleased to get off so easily; but I noticed that Dick Pearl turned pale, and looked very much troubled. He was a relative of Mr. Parasyte, and it was generally understood that he was a free scholar, his parents being too poor to pay his board and tuition. While he expected to be ducked in the lake, or subjected to some personal indignity, after the manner in which boys usually treat such cases, his courage was good. Now, it appeared that the boys simply intended to have Poodles expelled, or to ask their parents and guardians to remove them; and as most of the students were from fourteen to eighteen years of age, they would probably have influence enough to effect their design.[85]

"Pearl," said the judge, while the other culprit was apparently still attempting to figure out the result of the trial.

"I'm here," replied Pearl.

"We are entirely satisfied that Poodles had some assistance in performing his examples. It is believed that you gave him that assistance. If you did, own up."

"Who says I helped Poodles?"

"I say so, for one," added the judge, sharply.

"Can you prove it?"

"I will answer that question after you have confessed or refused to confess. You shall have fair play, as well as Poodles. If you wish to put yourself right on the record, you can do so; if not, you shall leave, or we will."

Pearl looked troubled. He was under very great obligations to Mr. Parasyte. If he denied that he had helped Poodles, and it was then proved against him, the boys would insist that he should be expelled. If he stood out, he must either be expelled or the Institute be broken up. He did not appear willing to take such a responsibility.[86]

"You can do as you please, Pearl; but tell the truth, if you say anything," continued Vallington.

"I did help Poodles," said he, looking down at the floor.

"How much did you help him?"

"I lent him my examination paper, and he copied all the solutions upon his own."

"And after that you were willing to declare that you had not assisted any one?" demanded the judge, with a look of supreme contempt on his fine features.

"I had not helped any one when I signed my paper."

"Humph!" exclaimed Vallington, with a withering sneer. "That is the meanest kind of a lie."

"I didn't mean to assist him; he teased me till I couldn't help myself," pleaded Pearl.

A further examination showed that Poodles had browbeaten and threatened him; and we were disposed to palliate Pearl's offence, in consideration of his poverty and his dependent position, after he had confessed his error.

"Are you willing to make this acknowledgment[87] to Mr. Parasyte?" asked the judge, in a tone of compassion.

"I don't want to; but I will. I suppose he will send me home then," replied the culprit.

"We will do what we can for you," added the judge.