Title: Bulgaria

Author: Frank Fox

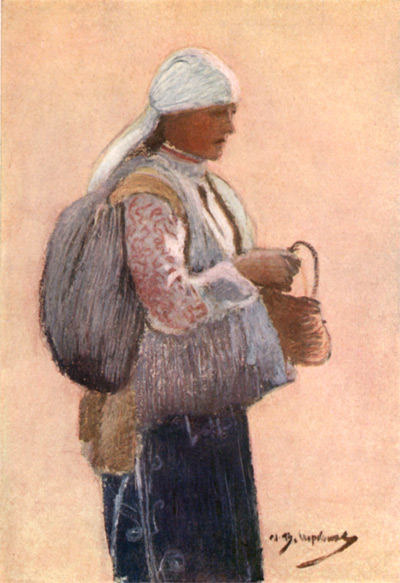

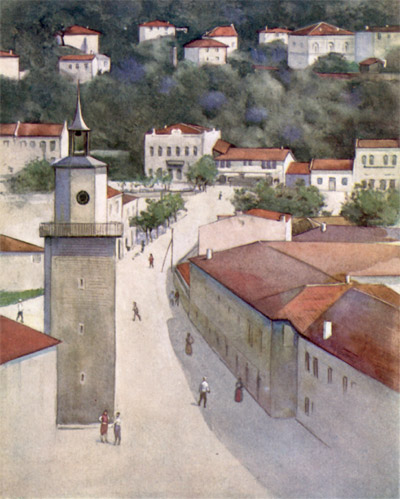

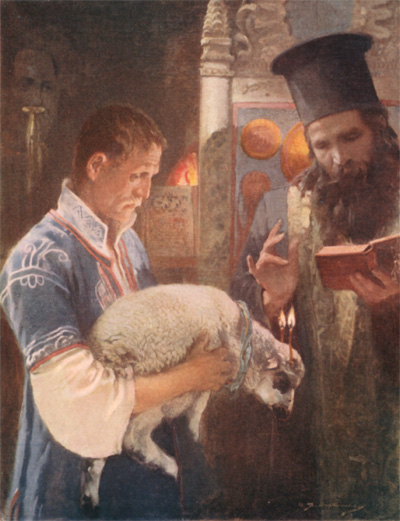

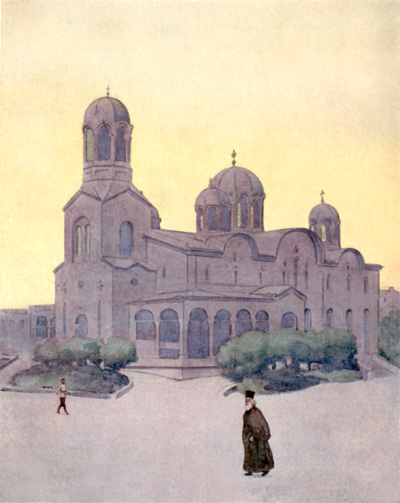

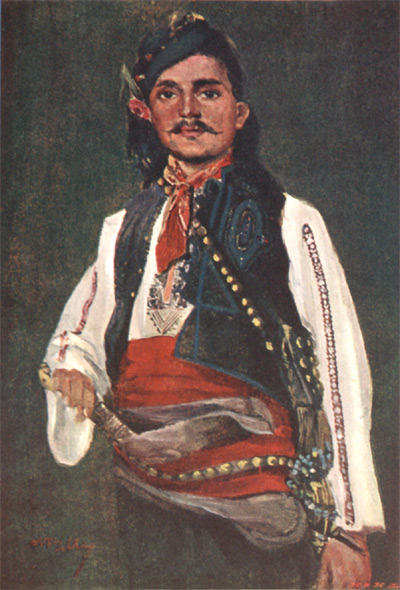

Illustrator: Jan Vaclav Mrkvicka

Noel Pocock

Release date: August 6, 2007 [eBook #22257]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bruce Albrecht, Jacqueline Jeremy and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Uniform with this Volume

AUSTRIA–HUNGARY

ENGLAND

FRANCE

ITALY

SWITZERLAND

a. and c. black, ltd.,

4 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W.

BULGARIA

BY

WITH 32 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR

LONDON

A. AND C. BLACK, LIMITED

1915

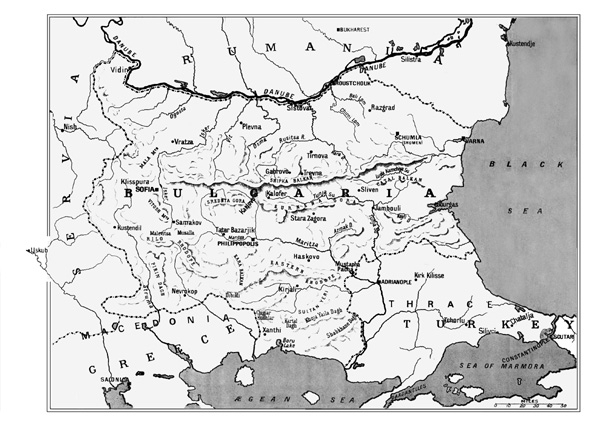

Sketch Map at end of Volume.

Instructed in the autumn of 1912 to join the Bulgarian army, then mobilising for war against Turkey, as war correspondent for the London Morning Post, I made my preparations with the thought uppermost that I was going to a cut-throat country where massacre was the national sport and human life was regarded with no sentimental degree of respect. The Bulgarians, a generation ago, had been paraded before the eyes of the British people by the fiery eloquence of Mr. Gladstone as a deeply suffering people, wretched victims of Turkish atrocities. After the wide sympathy that followed his Bulgarian Atrocities campaign there came a strong reaction. It was maintained that the Bulgarians were by [2]no means the blameless victims of the Turks; and could themselves initiate massacres as well as suffer from them. Some even charged that there was a good deal of party spirit to account for the heat of Mr. Gladstone's championship. I think that the average British opinion in 1912 was that, regarding the quarrels between Bulgar and Turk, there was a great deal to be said against both sides; and that no Balkan people was worth a moment's sentimental worry. "Let dogs delight to bark and bite, for 'tis their nature to," expressed the common view when one heard that there had been murders and village-burnings again in the Balkans.

Certainly there were enthusiasts who held to the old Gladstonian faith that there was some peculiar merit in the Bulgarian people which justified all that they did, and which would justify Great Britain in going into the most dangerous of wars on their behalf. These enthusiasts, as if to make more startlingly clear their love for Bulgaria, commonly took a profoundly pacific view of all other questions of international politics, and would become passionately indignant at the suggestion that the British Power should ever move navy or army in defence of any selfish [3]British interest. They were—they still are, it may be said—the leading lights of what is called the Peace-at-any-price party, detesting war and "jingoism," and viewing patriotism, when found growing on British soil, with dry suspicion. Patriotism in Bulgaria is, however, to their view a growth of a different order, worthy to be encouraged and sheltered at any cost.

As a counter-weight to these enthusiasts, Great Britain sheltered a little band, usually known as pro-Turks, who believed, with almost as passionate a sincerity as that of the pro-Bulgarians, that the Turk was the only gentleman in Europe, and that his mild and blameless aspirations towards setting up the perfect State were being cruelly thwarted by the abominable Bulgars and other Balkan riff-raff. Good government in the Balkans would come, they held, if the tide of Turkish rule flowed forward and the restless, semi-savage, murderous Balkan Christian states went back to peace and philosophic calm under the wise rule of Cadi administering the will of the Khalifate.

But pro-Bulgarian and pro-Turk made comparatively few converts in Great Britain. They formed influential little groups and inspired [4]debates in the House of Lords and the House of Commons, and published literature, and went out as missions to their beloved nationalities, and had all their affection confirmed again by the fine appreciation showered upon them. The great mass of British public opinion, however, they did not touch. There was never a second flaming campaign because of Turkish atrocities towards Bulgaria, and the pro-Turks never had a sufficient sense of humour to suggest a counter-campaign when Bulgarians made reprisals. In official circles the general attitude towards Balkan affairs was one of vexation alternating with indifference.

"Those detestable Balkans!" quoth one diplomat in an undiplomatic moment: and expressed well the official mind. "They are six of one and half a dozen of the other," said the man in the street when he heard of massacres, village-burnings, and tortures in the Balkans; and he turned to the football news with undisturbed mind, seeking something on which a fair opinion could be formed without too much worry.

The view of the man in the street was my view in 1912. I can recall being contented in my mind [5]to know that at any rate one's work as a war correspondent would not be disturbed by any sympathy for the one side or the other. Whichever side lost it would deserve to have lost, and whatever reduction in the population of the Balkan Peninsula was caused by the war would be ultimately a benefit to Europe. In parts of America where the race feeling is strongest, they say that the only good nigger is a dead nigger. So I felt about the Balkan populations. The feelings of a man with some interest in flocks of sheep on hearing that war had broken out between the wolves and the jackals would represent fairly well the attitude of mind in which I packed my kit for the Balkans.

It is well to put on record that mental foundation on which I built up my impressions of the Balkans generally, and of the Bulgarian people particularly, for at the present time (1914) I think it may safely be said that the Bulgarian people are somewhat under a cloud, and are not standing too high in the opinion of the civilised world. Yet, to give an honest record of my observations of them, I shall have to praise them very highly in some respects. Whilst it would be going too far to say that the praise is reluctant, [6]it is true that it has been in a way forced from me, for I went to Bulgaria with the prejudice against the Bulgarians that I have indicated. And—to make this explanation complete—I may add that I came back from the Balkans not a pro-Bulgarian in the sense that I was anti-Greek or anti-Servian or even anti-Turk; but with a feeling of general liking for all the peasant peoples whom a cruel fate has cast into the Balkans to fight out there national and racial issues, some of which are older than the Christian era.

Yes, even the Turk, the much-maligned Turk, proved to have decent possibilities if given a decent chance. Certainly he is no longer the Terrible Turk of tradition. Most of the Turks I encountered in Bulgaria were prisoners of war, evidently rather pleased to be in the hands of the Bulgarians who fed them decently, a task which their own commissariat had failed in: or were contented followers of menial occupations in Bulgarian towns. I can recall Turkish boot-blacks and Turkish porters, but no Turks who looked like warriors, and if they are cut-throats by choice (I do not believe they are) they are very mild-mannered cut-throats indeed.

Coming back from the lines of Chatalja towards [7]the end of 1912, I had, for one stage of five days, between Kirk Kilisse and Mustapha Pasha, a Turkish driver. He had been a Bulgarian subject (I gathered) before the war, and with his cart and two horses had been impressed into the transport service. At first with some aid from an interpreter, afterwards mostly by signs and broken fragments of language, I got to be able to converse with this Turk. (In the Balkans the various shreds of races have quaint crazy-quilt patchworks of conversational language. Somehow or other even a British citizen with more than the usual stupidity of our race as to foreign languages can make himself understood in the Balkan Peninsula, which is so polyglottic that its inhabitants understand signs very well.) My Turk friend, from the very first, filled my heart with sympathy because of his love for his horses. Since he had come under the war-rule of the Bulgarians, he complained to me, he had not been allowed to feed his horses properly. They were fading away. He wept over them. Actual tears irrigated the furrows of his weather-beaten and unwashed cheeks.

As a matter of fact the horses were in very good condition indeed, considering all the circum[8]stances; as good, certainly, as any horses I had seen since I left Buda-Pesth. But my heart warmed to this Turcoman and his love for his horses. I had been seeking in vain up to this point for the appearance of the Terrible Turk of tradition; the Turk, with his well-beloved Arabian steed, his quite-secondary-in-consideration Circassian harem; the fierce, unconquerable, disdainful, cruel Turk, manly in his vices as well as in his virtues. My Turk had at least one recognisable characteristic in his love for his horses. As he sorrowed over them I comforted him with a flagon—it was of brandy and water: and the Prophet, when he forbade wine, was ignorant of brandy, so Islam these days has its alcoholic consolation—and I stayed him with cigarettes. He had not had a smoke for a month and, put in possession of tobacco, he plunged into a mood of rapt exultation, rolling cigarette after cigarette, chuckling softly as he inhaled the smoke, turning towards me now and again with a gesture of thanks and of respect. I had taken over the reins and the little horses were doing very well.

That day, though we had started late, the horses carried us thirty-five miles, and I camped [9]at the site of a burned-out village. The Turk made no objection to this. Previously coming over the same route with an ox-cart, my Macedonian driver had objected to camping except in occupied villages where there were garrisons. He feared Bashi-Bazouks (the Turkish irregular bands which occasionally showed themselves in the rear of the Bulgarian army) and wolves. Probably, too, he feared ghosts, or was uneasy and lonely when out of range of the village smells. Now I preferred a burned village site, because the only clean villages were the burned ones; and for the reason of water it was necessary to camp at some village or village site. Mr. Turk went up hugely in my estimation when I found that he had no objections to the site of a burned village as a camping-place.

But the first night in camp shattered all my illusions. The Turk unharnessed and lit the camp fire. I cooked my supper and gave him a share. Then he squatted by the fire and resumed smoking. The horses over which he had shed tears waited. After the Turk's third cigarette I suggested that the horses should be watered and fed. The village well was about 300 yards away, and the Turk evidently did not like [10]the idea of moving from the fire. He did not move, but argued in Turkish of which I understood nothing. Finally I elicited the fact that the horses were too tired to drink and too tired to eat the barley I had brought for them. As a remedy for tiredness they were to be left without water and food all night.

As plainly as was possible I insisted to the Turk that the horses must be watered at once, and afterwards given a good ration of barley. I dragged him from the fire to the horses and made my meaning clear enough. The Turk was stubborn. Clearly either I was to water the horses myself or they were to be left without water, and my old traditions of horse-mastery would not allow me to have them fed without being watered. So this was the extent of the Turk's devotion to his horses!

It was necessary to be firm, and I took up the cart whip to the Turk and convinced him almost at once that the horses were not "too tired" to drink.

Mr. Turk did not resent the blows in the least. He refrained from cutting my throat as I slept that evening. Afterwards a mere wave of the hand towards the whip made him move with [11]alacrity. At the end of the journey, when I gave him a good "tip," he knelt down gallantly in the mud of Mustapha Pasha and kissed my hand and carried it to his forehead.

So faded away my last hope of meeting the Terrible Turk of tradition in the Balkans. Perhaps he exists still in Asia Minor. As I saw the Turk in Bulgaria and in European Turkey, he was a dull monogamic person with no fiery pride, no picturesque devilry, but a great passion for sweetmeats—not merely his own "Turkish Delight," but all kinds of lollipops: his shops were full of Scotch and English confectionery.

But the Bulgarian, not the Turk, is our theme. This introduction, however, will make it plain that, as the result of a direct knowledge of the Balkans, during some months in which I had the opportunity of sharing in Bulgarian peasant life, I came to the admiration I have now for the Bulgarian people in spite of a preliminary prejudice. And this conversion of view was not the result of becoming involved in some passionate political attitude regarding Balkan affairs. I am not now prepared to take up the view of the fanatic Bulgar-worshippers who must not only exalt the Bulgarian nation as a modern Chosen [12]People, but must represent Servian, Greek, and Turk as malignant and devilish in order to throw up in the highest light their ideas of Bulgarian saintliness.

The Balkans are apt to have strange effects on the traveller. Perhaps it is the blood-mist that hangs always over the Balkan plains and glens which gets into the head and intoxicates one: perhaps it is the call to the wild in us from the primitive human nature of the Balkan peoples. Whatever the reason, it is a common thing for the unemotional English traveller to go to the Balkans as a tourist and return as a passionate enthusiast for some Balkan Peninsula nationality. He becomes, perhaps, a pro-Turk, and thereafter will argue with fierceness that the Turk is the only man who leads an idyllic life in Europe to-day, and that the way to human regeneration is through a conversion to Turkishness. He fills his house with Turkish visitors and writes letters to the papers pointing out the savagery we show in the "Turk's Head" competition for our cavalry-men at military tournaments. Or he may become a pro-Bulgar with a taste for the company of highly flavoured Macedonian revolutionary priests and a grisly habit of turning [13]the conversation to the subject of outrage and massacre. To become a pro-Servian is not a common fashion, but pro-Albanians and pro-Montenegrins and Philhellenists are common enough.

The word "crank," if it can be read in a kindly sense and stripped of malice, covers all these folk. Exactly why the Balkans have such an effect in making "cranks" I have already confessed an inability to explain. The fact must stand as one of those things which we must believe—if we read Parliamentary debates and newspaper correspondence—but cannot comprehend.

But any "crank" view I disavow. Whether from a natural lack of a generous sense of partisanship, or a journalistic training (which crabs emotionalism: that acute observer of men, the late "General" Booth, said once of his Salvation Army work, "You can never 'save' a journalist"), I came back from the Balkans without a desire to join a society to exalt any one of the little nationalities struggling for national expression in its rowdy life. But I did get to a strong admiration of the Bulgarian people as soldiers, farmers, road-makers, and as friends. The evi[14]dence on which that admiration is based will be stated in these pages, and it is my hope that it will do a little to set the Bulgarian—who is sometimes much overpraised and often much over-abused—in a right light before my readers.

But before dealing with the Bulgarian of to-day we must look into his antecedents.

Probably not the least part of the interest which the traveller or the student will take in Bulgaria is the fact that it was the arena in which were fought the great battles of races declaring the doom of the Roman Empire. Fortunately, from old Gothic chronicles it is possible to get pictures—valuable for vivid colouring rather than strict accuracy—which bring very close to us that curious tragedy of civilisation, the destruction of the power of Rome and the overrunning of Europe by successive waves of barbarians.

In the fifth century before Christ, what is now Bulgaria was practically a Greek colony, and its trading relations with the North gave possibly the first hint to the Goths of the easiest path by which to invade the Roman Empire. The [16]present Bulgarian towns of Varna (on the Black Sea) and Kustendji (which has a literary history in that it was later a place of banishment for Ovid the poet) can be traced back as Greek trading towns through which passed traffic from the Mediterranean to the "Scythians," i.e. the Goths of the North. Amber and furs came from the north of the river valleys, and caravans from the south brought in return silver and gold and bronze.

Towards the dawn of the Christian era there began a swelling-over of the Goths from the Baltic shores, sending one wave of invasion down towards Italy, another towards the Black Sea and the Aegean. Jordanes, the earliest Gothic historian, writing in the sixth century gives this account—derived from Gothic folk-songs—of the movement of the invasion towards the Balkan Peninsula (probably about a.d. 170):

In the reign of the fifth King after Berig, Filimer, son of Gadariges, the people had so greatly increased in numbers that they all agreed in the conclusion that the army of the Goths should move forward with their families in quest of more fitting abodes. Thus they came to those regions of Scythia which in their tongue are called Oium, whose great fertility pleased them much. But there was a bridge there by which the army [17]essayed to cross a river, and when half of the army had passed, that bridge fell down in irreparable ruin, nor could any one either go forward or return. For that place is said to be girt round with a whirlpool, shut in with quivering morasses, and thus by her confusion of the two elements, land and water, Nature has rendered it inaccessible. But in truth, even to this day, if you may trust the evidence of passers-by, though they go not nigh the place, the far-off voices of cattle may be heard and traces of men may be discerned.

That part of the Goths therefore which under the leadership of Filimer crossed the river and reached the lands of Oium, obtained the longed-for soil. Then without delay they came to the nation of the Spali, with whom they engaged in battle and therein gained the victory. Thence they came forth as conquerors, and hastened to the farthest part of Scythia which borders on the Black Sea.

The people whom these Teutonic Goths displaced were Slavs. The Goths settled down first on the Black Sea between the mouths of the Danube and of the Dniester and beyond that river almost to the Don, becoming thus neighbours of the Huns on the east, of the Roman Empire's Balkan colonies on the west, and of the Slavs on the north. It is reasonable to suppose that to some extent they mingled their blood somewhat with the Slavs whom they dispossessed, and that they came into some contact with the Huns also. [18]It was in the third century of the Christian era that these Goths, who had been for some time subsidised by the Roman emperors on the condition that they kept the peace, crossed the Danube and devastated Moesia and Thrace. An incident of this invasion was the successful resistance of the garrison of Marcianople—now Schumla—to the invaders. In a following campaign the Goths crossed the Danube at Novae (now Novo-grad) and besieged Philippopolis, a city which still keeps its name and now, as then, is an important strategical point commanding the Thracian Plain. (It was Philippopolis which would have been the objective of the Turkish attack upon Bulgaria in 1912–13 if Turkey had been given a chance in that war to develop a forward movement.) This city was taken by the Goths, and the first notable Balkan massacre is recorded, over 100,000 people being put to the sword within its walls. Later in the campaign the Emperor Decius was defeated and killed by the Goths in a battle waged on marshy ground near the mouth of the Danube. This was the second of the three great disasters which marked the doom of the Roman Empire: the first was the defeat of Varus in Germany; the third was [19]to be the defeat and death of the Emperor Valens before Adrianople. Bulgaria, the scene of the second and third disasters, can accurately be described as having provided the death-arena for Rome.

From the defeat of Decius (A.D. 251) may be said to date the Gothic colonisation of the Balkan Peninsula. True, after that event the Goths often retired behind the Danube for a time, but, as a rule, thereafter they were steadily encroaching on the Roman territory, carrying on a maritime war in the Black Sea as well as land forays across the Danube. It was because of the successes of the Goths in the Balkans that the decision was ultimately arrived at to move the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to Constantinople. During the first Gothic attack, after the death of Decius, Byzantium itself was threatened, and the cities around the Sea of Marmora sacked. An incident of this invasion which has been chronicled is that the Goths enjoyed hugely the warm baths they found at Anchialus—"there were certain warm springs renowned above all others in the world for their healing virtues, and greatly did the Goths delight to wash therein. And having tarried there many days they thence [20]returned home." Now Anchialus is clearly identifiable as the present Bulgarian town of Bourgas, a flourishing seaport connected by rail with Jambouli and still noted for its baths.

In a later Gothic campaign (a.d. 262), based on a naval expedition from the Black Sea, Byzantium was taken, the Temple of Diana at Ephesus destroyed, and Athens sacked. A German historian pictures this last incident:

The streets and squares which at other times were enlivened only by the noisy crowds of the ever-restless citizens, and of the students who flocked thither from all parts of the Graeco-Roman world, now resounded with the dull roar of the German bull-horns and the war-cry of the Goths. Instead of the red cloak of the Sophists, and the dark hoods of the Philosophers, the skin-coats of the barbarians fluttered in the breeze. Wodan and Donar had gotten the victory over Zeus and Athene.

It was in regard to this capture of Athens that the story was first told—it has been told of half a dozen different sackings since—that a band of Goths came upon a library and were making a bonfire of its contents when one of their leaders interposed:

"Not so, my sons; leave these scrolls untouched, that the Greeks may in time to come, as they have in time [21]past, waste their manhood in poring over their wearisome contents. So will they ever fall, as now, an easy prey to the strong unlearned sons of the North."

In the ultimate result the Goths were driven out of Athens by a small force led by Dexippus, a soldier and a scholar whose exploit revived memory of the deeds of Greece in her greatness. The capture of Athens deeply stirred the civilised world of the day, and "Goth" still survives as a term of destructive barbarism.

A few years later (a.d. 269) the Goths began a systematic invasion of the Balkan provinces of the Roman Empire, attacking the Roman territory both by sea and by land. The tide of victory sometimes turned for a while, and at Naissus (now Nish in Servia, near the border of Bulgaria) the Goths were defeated by the Emperor Claudius. Their defeated army was then shut up in the Balkan Mountains for a winter, and the Gothic power in the Balkans temporarily crushed. The Emperor Claudius, who took the surname Gothicus in celebration of his victory, announced it grandiloquently to the governor of Illyricum:

Claudius to Brocchus.

We have destroyed 320,000 of the Goths; we have sunk 2000 of their ships. The rivers are bridged over [22]with shields; with swords and lances all the shores are covered. The fields are hidden from sight under the superincumbent bones; no road is free from them; an immense encampment of waggons is deserted. We have taken such a number of women that each soldier can have two or three concubines allotted to him.

But the succeeding Emperor, Aurelian, gave up all Dacia to the Goths and withdrew the Romanised Dacians into the province of Moesia—made up of what is now Eastern Servia and Western Bulgaria. This province was divided into two and renamed Dacia. One part, Dacia Mediterranea, had for its capital Sardica, now Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria. Then followed a period of comparative peace. The Roman emperors saw that on the Balkan frontier their Empire had to be won or lost, and strengthened the defences there. Thus Diocletian made his headquarters at Nicomedia. Finally, Constantine moved the capital altogether to Constantinople. Goth and Roman at this time showed a disposition to a peaceful amalgamation, and the Bulgarian population was rapidly becoming a Romano-Gothic one. Christianity had been introduced, and the Gothic historian Jordanes tells of a Gothic people living upon the northern side of the Balkan Mountains:

There were also certain other Goths, who are called Minores, an immense people, with their bishop and primate Vulfila, who is said, moreover, to have taught them letters; and they are at this day dwelling in Moesia, in the district called Nicopolitana[1] at the foot of Mount Haemus, a numerous race, but poor and unwarlike, abounding only in cattle of divers kinds, and rich in pastures and forest timber, having little wheat, though the earth is fertile in producing other crops. They do not appear to have any vineyards: those who want wine buy it of their neighbours; but most of them drink only milk.

[1] Around the modern town of Tirnova.

A contemporary of the saintly Ulfilas (who surely should be accepted as the first national hero of the Bulgarians) states that Ulfilas had originally lived on the other side of the Danube and had been driven by persecution to settle in Bulgaria. This contemporary, Auxentius, records:

And when, through the envy and mighty working of the enemy, there was kindled a persecution of the Christians by an irreligious and sacrilegious Judge of the Goths, who spread tyrannous affright through the barbarian land, it came to pass that Satan, who desired to do evil, unwillingly did good; that those whom he sought to make deserters became confessors of the faith; that the persecutor was conquered, and his victims wore the wreath of victory. Then, after the glorious martyrdom of many servants and handmaids of Christ, as the [24]persecution still raged vehemently, after seven years of his episcopate were expired, the blessed Ulfilas being driven from "Varbaricum" with a great multitude of confessors, was honourably received on the soil of Roumania by the Emperor Constantius of blessed memory. Thus as God by the hand of Moses delivered His people from the violence of Pharaoh and the Egyptians, and made them pass through the Red Sea, and ordained that they should serve Him [on Mount Sinai], even so by means of Ulfilas did God deliver the confessors of His only-begotten Son from the "Varbarian" land, and cause them to cross over the Danube, and serve Him upon the mountains [of Haemus] like his saints of old.

Ulfilas civilised as well as Christianised the Goths of Bulgaria, and was responsible for the earliest Gothic alphabet—the Moeso-Gothic. He translated most of the Scriptures into Gothic, leaving out of his translation only such war stories as "the Book of Kings," judging that these would be too exciting for his Gothic flock and would incite them to war.

After a century of peace war broke out again between the Goths and the Roman Empire—which may now be called rather the Greek Empire—in A.D. 369. The course of the war was at first favourable to the Emperor Valens. All the independent Goths were driven back behind the Danube boundary, but were allowed to live there [25]in peace. The Roman orator Themistius, in congratulating the Emperor Valens, put on record the extent of his achievement and of his magnanimity:

But now, along almost all the frontiers of the Empire, peace reigns, and all the preparation for war is perfect; for the Emperor knows that they most truly work for peace who thoroughly prepare for war. The Danube-shore teems with fortresses, the fortresses with soldiers, the soldiers with arms, the arms both beautiful and terrible. Luxury is banished from the legions, but there is an abundance of all necessary stores, so that there is now no need for the soldier to eke out his deficient rations by raids on the peaceful villagers. There was a time when the legions were terrible to the provincials, and afraid of the barbarians. Now all that is changed: they despise the barbarians and fear the complaint of one plundered husbandman more than an innumerable multitude of Goths.

To conclude, then, as I began. We celebrate this victory by numbering not our slaughtered foes but our living and tamed antagonists. If we regret to hear of the entire destruction even of any kind of animal, if we mourn that elephants should be disappearing from the province of Africa, lions from Thessaly, and hippopotami from the marshes of the Nile, how much rather, when a whole nation of men, barbarians it is true, but still men, lies prostrate at our feet, confessing that it is entirely at our mercy, ought we not instead of extirpating, to preserve it, and make it our own by showing it compassion?

[26]Valens restored Bulgaria to the position of a wholly Roman province, even the Gothic Minores being driven across the Danube. But there was now to come another racial element into the making of Bulgaria—the Huns.

I can still recall the resentment and indignation of the Bulgarian officers in 1913 because a French war correspondent had, in a despatch which had escaped the Censor, likened the crossing of the Thracian Plain by the great convoys of Bulgarian ox-wagons to the passage of the Danube by the Huns in the fourth century. The Bulgarians, always inclined to be sensitive, thought that the allusion made them out to be barbarians. But it was intended rather, I think, to show the writer's knowledge of the early history of the Balkan Peninsula and of the close racial ties between the Bulgarians of to-day and the original Huns. We have seen how the Gothic invasion, coming from the Baltic to the Black Sea, pushed on to the borders of the Hun people living east of the Volga. These Huns now prepared an answering wave of invasion.

To the Goths the Huns—the first of the Tartar hordes to invade Europe—were a source [27]of superstitious terror. The Gothic historian Jordanes writes with frank horror of them:

We have ascertained that the nation of the Huns, who surpassed all others in atrocity, came thus into being. When Filimer, fifth king of the Goths, after their departure from Sweden, was entering Scythia, with his people, as we have before described, he found among them certain sorcerer-women, whom they call in their native tongue Haliorunnas, whom he suspected and drove forth from his army into the wilderness. The unclean spirits that wander up and down in desert places, seeing these women, made concubines of them; and from this union sprang that most fierce people, the Huns, who were at first little, foul, emaciated creatures, dwelling among the swamps and possessing only the shadow of human speech by way of language.

According to Priscus they settled first on the eastern shore of the Sea of Azof, lived by hunting, and increased their substance by no kind of labour, but only by defrauding and plundering their neighbours.

Once upon a time when they were out hunting beside the Sea of Azof, a hind suddenly appeared before them, and having entered the water of that shallow sea, now stopping, now dashing forward, seemed to invite the hunters to follow on foot. They did so, through what they had before supposed to be trackless sea with no land beyond it, till at length the shore of Scythia lay before them. As soon as they set foot upon it, the stag that had guided them thus far mysteriously disappeared. This, I trow, was done by those evil spirits that begat them, for the injury of the Goths. But the hunters who had lived in complete ignorance of any other land beyond the Sea of Azof were struck with admiration [28]of the Scythian land and deemed that a path known to no previous age had been divinely revealed to them. They returned to their comrades to tell them what had happened, and the whole nation resolved to follow the track thus opened out before them. They crossed that vast pool, they fell like a human whirlwind on the nations inhabiting that part of Scythia, and offering up the first tribes whom they overcame, as a sacrifice to victory, suffered the others to remain alive, but in servitude.

With the Alani especially, who were as good warriors as themselves, but somewhat less brutal in appearance and manner of life, they had many a struggle, but at length they wearied out and subdued them. For, in truth, they derived an unfair advantage from the intense hideousness of their countenances. Nations whom they would never have vanquished in fair fight fled horrified from those frightful—faces I can hardly call them, but rather—shapeless black collops of flesh, with little points instead of eyes. No hair on their cheeks or chins gives grace to adolescence or dignity to age, but deep furrowed scars instead, down the sides of their faces, show the impress of the iron which with characteristic ferocity they apply to every male child that is born among them, drawing blood from its cheeks before it is allowed its first taste of milk. They are little in stature, but lithe and active in their motions, and especially skilful in riding, broad-shouldered, good at the use of the bow and arrows, with sinewy necks, and always holding their heads high in their pride. To sum up, these beings under the form of man hide the fierce nature of the beast.

That was a view very much coloured by race [29]prejudice and the superstitious fears of the time. It suggests that at a very early period of Balkan history the different races there had learned how to abuse one another. English readers might contrast it with Matthew Arnold's picture of a Tartar camp in Sohrab and Rustum:

The sun by this had risen, and clear'd the fog

From the broad Oxus and the glittering sands.

And from their tents the Tartar horsemen filed

Into the open plain; so Haman bade—

Haman, who next to Peran-Wisa ruled

The host, and still was in his lusty prime.

From their black tents, long files of horse, they stream'd;

As when some grey November morn the files,

In marching order spread, of long-neck'd cranes

Stream over Casbin and the southern slopes

Of Elburz, from the Aralian estuaries,

Or some frore Caspian reed-bed, southward bound

For the warm Persian sea-board—so they stream'd

.

The Tartars of the Oxus, the King's guard,

First, with black sheep-skin caps and with long spears;

Large men, large steeds; who from Bokhara come

And Khiva, and ferment the milk of mares.

Next, the more temperate Toorkmuns of the south,

The Tukas, and the lances of Salore,

And those from Attruck and the Caspian sands;

Light men and on light steeds, who only drink

The acrid milk of camels, and their wells.

And then a swarm of wandering horse, who came

From far, and a more doubtful service own'd;

The Tartars of Ferghana, from the banks

Of the Jaxartes, men with scanty beards

And close-set skull-caps; and those wilder hordes

[30]

Who roam o'er Kipchak and the northern waste,

Kalmucks and unkempt Kuzzaks, tribes who stray

Nearest the Pole, and wandering Kirghizzes,

Who come on shaggy ponies from Pamere;

These all filed out from camp into the plain.

Matthew Arnold gives to the Tartar camp tents of lattice-work, thick-piled carpets; to the Tartar leaders woollen coats, sandals, and the sheep-skin cap which is still the national head-dress of the Bulgarians. More important, in proof of his idea of their civilisation, he credits them with a high sense of chivalry and a faithful regard for facts. Sohrab and Rustum is, of course, a flight of poetic fancy; but its "local colour" is founded on good evidence. Probably the Huns, despite the terrors of their name, the echoes of which still come down the corridors of time; despite the awful titles which their leaders won (such as Attila, "the Scourge of God"), were not on a very much lower plane of civilisation than the Goths with whom they fought, or with the other barbarians who tore at the prostrate body of the Roman Empire. One may see people of very much the same type to-day on the outer edges of Islam in some desert quarters; one may see and, if one has such taste for the wild [31]and the free in life as has Cunninghame Graham, one may admire:

There in the Sahara the wild old life, the life in which man and the animals seem to be nearer to each other than in the countries where we have changed beasts into meat-producing engines deprived of individuality, still takes its course, as it has done from immemorial time. Children respect their parents, wives look at their husbands almost as gods, and at the tent door elders administer what they imagine justice, stroking their long white beards, and as impressed with their judicial functions as if their dirty turbans or ropes of camels' hair bound round their heads, were horse-hair wigs, and the torn mat on which they sit a woolsack or a judge's bench, with a carved wooden canopy above it, decked with the royal arms.

Thus, when the blue baft-clad, thin, wiry desert-dweller on his lean horse or mangy camel comes into a town, the townsmen look on him as we should look on one of Cromwell's Ironsides, or on a Highlander, of those who marched to Derby and set King George's teeth, in pudding time, on edge.

The Huns' movement from the north-east was the first Asiatic invasion of Europe since the fall of the Persian Empire. Almost simultaneously with it the Saracen first entered from the south, as the ally of the Christian Emperor against the Goths; and another Gothic chronicler, Ammianus, tells how the Saracen warriors inspired [32]also a lively horror in the Gothic mind. They came into battle almost naked, and having sprung upon a foe "with a hoarse and melancholy howl, sucked his life-blood from his throat." The Saracen of Ammianus was the forerunner of the Turk, the Hun of Jordanes, the forerunner of the Bulgarian. In neither case, of course, can the Gothic chronicler be accepted as an unprejudiced witness. But it is interesting to note how the first warriors from the Asiatic steppes impressed their contemporaries!

The first effect of the invasion of the country of the Goths by the Huns was to force the Goths to recross the Danube and trespass again on Roman territory. They sought leave from the Emperor Valens to do this. A contemporary historian records:

The multitude of the Scythians escaping from the murderous savagery of the Huns, who spared not the life of woman or of child, amounted to not less than 200,000 men of fighting age [besides old men, women, and children]. These, standing upon the river-bank in a state of great excitement, stretched out their hands from afar with loud lamentations, and earnestly supplicated that they might be allowed to cross over the river, bewailing the calamity that had befallen them, and promising that they would faithfully adhere to the Imperial alliance if this boon were granted them.

[33]The Emperor Valens allowed the Gothic host to cross the Danube into Bulgaria and Thrace, and having given them shelter, starved them and treated them so harshly and cruelly that they were close to rebellion when another great Gothic host, under King Fritigern, crossed the Danube without leave and came down as far as Marcianople (now Schumla). Here he was entertained at a "friendly" banquet by the Roman general Lupicinus. But whilst the banquet was in progress disorder arose among the Goths and the Romans outside the hall. The Gothic historians tell:

News of this disturbance was brought to Lupicinus as he was sitting at his gorgeous banquet, watching the comic performers and heavy with wine and sleep. He at once ordered that all the Gothic soldiers, who, partly to do honour to their rank, and partly as a guard to their persons, had accompanied the generals into the palace, should be put to death. Thus, while Fritigern was at the banquet, he heard the cry of men in mortal agony, and soon ascertained that it proceeded from his own followers shut up in another part of the palace, whom the Roman soldiers at the command of their general were attempting to butcher. He drew his sword in the midst of the banqueters, exclaimed that he alone could pacify the tumult which had been raised among his followers, and rushed out of the dining-hall with his companions. They were received with shouts [34]of joy by their countrymen outside; they mounted their horses and rode away, determined to revenge their slaughtered comrades.

Delighted to march once more under the generalship of one of the bravest of men, and to exchange the prospect of death by hunger for death on the battlefield, the Goths at once rose in arms. Lupicinus, with no proper preparation, joined battle with them at the ninth milestone from Marcianople, was defeated, and only saved himself by a shameful flight. The barbarians equipped themselves with the arms of the slain legionaries, and in truth that day ended in one blow the hunger of the Goths and the security of the Romans; for the Goths began thenceforward to comport themselves no longer as strangers but as inhabitants, and as lords to lay their commands upon the tillers of the soil throughout all the Northern provinces.

That began a war which inflicted the third great blow on the Roman Empire—the defeat and death of the Emperor Valens before Adrianople. The Goths in this campaign seem to have brought in some of their old enemies, the Huns, as allies—pretty clear proof of the contention I have set up that the Huns were not such desperate savages; but these Asiatics made the war rather more brutal than was usual for those days, without a doubt. Theodosius, the younger (son of that brave general who had just won back Britain for the Roman Empire), restored somewhat the [35]Roman power in the provinces south of the Balkans for a time. But in the year 380 the Romans made peace again with the Goths, allowing them to settle in Bulgaria as well as north of the Danube as allies of the Roman Power.

In the latter part of the fourth century and the first half of the fifth century the Huns fill the pages of Bulgarian history. Then came the Slavs; and then, in the seventh century, the Bulgars, almost certainly a Hun tribe, but Huns modified by two centuries of time. But the death of Valens may be said to have ended the Roman Empire as a World Power. Let us retrace our steps a little and give the chief facts as to how a Bulgarian Empire for a time—a very short time—replaced the Roman Empire over a great area of the Balkan Peninsula.

The historian, rightly, must always march under a banner inscribed "Why?" The facts of history bring no real informing to the human mind unless they can be traced to their causes, and thus a chain of events followed link by link to see why some happening was so fruitful in results, and to search for the relation of apparently isolated and accidental incidents.

The Balkan Peninsula has to-day just emerged from a most bloody war. It prepares for another to break out as soon as the exhaustion of the moment has passed. Since ever the pages of history were inscribed it has been vexed by savage wars. Why?

There is an explanation near at hand and clear. In the Balkans there is a geographical area, which could house one nation comfortably, [37]and is occupied by the scraps of half a dozen nations.

(1) There are the remnants of the Turks who at one time threatened the conquest of all Europe. Back from the walls of Vienna they have been driven little by little until now they occupy the toe only of the Balkan Peninsula. But the days have not far departed when they held almost all the Peninsula, and the present smallness of their portion dates back only from 1913.

(2) There are the Greeks, heirs of the traditions of Philip and Alexander, and of the old Roman Empire. For centuries their national but not their racial existence was dormant under the heel of the Turk. Greek independence was restored recently, and since the war of 1912–1913 has established itself vigorously.

(3) There are the Roumanians, descendants of the old Roman colony of Trajan in Dacia.

(4) There are the Bulgars, originally a Tartar people coming from the banks of the Volga, who entered Bulgaria in the seventh century as the Normans entered England at a later date, and who mingled with a Slav race they found there—at first as conquerors, afterwards becoming the absorbed race.

[38](5) There are the Serbs, somewhat akin to the Bulgars, whose original home seems to have been that of the Don Cossacks, who also came into the Peninsula in the seventh century. They are of purer Slav blood than the Bulgars.

(6) There are the Montenegrins, an off-shoot of the Serbs, who in the fourteenth century, when the Servian Empire fell, took to the hills and maintained their independence.

Those are the six main racial elements. But there are other scraps of peoples—the Albanians, for example, and the Macedonians, and tribes of Moslem Bulgars, and some Asiatic elements brought in by the Turks.

So far, then, the answer to the question, "Why are the Balkans so often at war?" is easy of answer. Given the existence on one peninsula of six different races, four of which have past great traditions of Empire, and there is certain to be uneasy house-keeping. But the inquiry has to be pushed further. Why is it that this unhappy Peninsula should have been made thus a scrap-heap for bits of nations, a refuge for sore-headed remnants of Imperial peoples? The answer to that is chiefly geographical.

A study of the map will show that when there [39]was a great movement from the north of Europe to the south, its easiest line of march was down the valley of the Danube along the Balkan Peninsula. In prehistoric times the peoples around the European shores of the Mediterranean brought to accomplishment a very advanced type of civilisation. It owed its foundations to Egypt or to the Semitic peoples, such as the Phoenicians, the Tyrians, and the Carthaginians, whose race-home was Asia Minor. Whilst this Mediterranean civilisation was being shaped in the south—in the north, in the forests or plains along the shores of the Baltic and of the North Sea, the fecund Teutonic people were swelling to a mighty host and overflowing their boundaries. A flood of these people in time came surging south searching for new lands. The natural course of that flood was by the valley of the Danube to the Balkan Peninsula. Down that peninsula they cut their path—not without bloodshed one may guess—and founded the Grecian civilisation. Of this prehistoric movement there is no written evidence; but it is accepted by anthropologists as certain. Thus Sir Harry Johnston records, not as a surmise but as a fact:

[40] The Nordic races, armed with iron or steel swords, spears and arrow-heads, descended on the Alpine, Iberian, Lydian, and Aegean peoples of Southern Europe with irresistible strength. It was iron against bronze, copper, and stone; and iron won the day.

Prehistoric invasions of the Balkan Peninsula brought in the fair-haired, blue-eyed Greeks, the semi-barbarian conquerors of the Mukenaian and Minôan kingdoms. Tribes nearly allied to the Ancient Greeks diverged from them in Illyria, invaded the Italian Peninsula, and became the ancestors of the Sabines, Oscans, Latins, etc.

The parent ancestral speech of the German tribes about four to five thousand years ago was probably closely approximated in syntax, and in the form and pronunciation of words, to the other progenitors of European Aryan languages, especially the Lithuanian, Slav, Greek, and Italic dialects. Keltic speech was perhaps a little more different owing to its absorption of non-Aryan elements; but if we can judge of prehistoric German from what its eastern sister, the Gothic language, was like as late as the fifth century B.C., we can, without too much straining of facts, say that the prehistoric Greeks, when they passed across Hungary into the mountainous regions of the Balkans, and equally the early Italic invaders of Italy, were simply another branch of the Teutonic peoples later in separation than the Kelts, with whom, however, both the Italic and the Hellenic tribes were much interwoven.... Very English or German in physiognomy were most of the notabilities in the palmy days of Greece, to judge by their portrait-busts and the types of male and female beauty most in favour—as far south as Cyprus—in the periods when Greek art had become realistic and was released from the influence of an Aegean standard of beauty.

[41]The invasion from the North of people flowing south by way of the Balkan Peninsula began that unhappy area's record of race-struggles and constant warfare. The Greek civilisation had scarcely established itself before it was attacked by an Asiatic Power—Persia. Again the Balkan Peninsula was inevitably the scene of the conflict, and such battles as Thermopylae and Marathon made names to resound for ever in the mouths of men. The peril from Persia over, the Balkan Peninsula, after seeing the struggles between the different Greek states for supremacy, was given another great ordeal of blood by Philip of Macedonia and Alexander the Great. Alexander carried a great invasion from Greece into the very heart of Asia, but founded no permanent empire.

The next phase of Balkan history was under the Roman Power. When the Roman strength had reached its zenith and entered upon the curve of decay, it was on the Balkan boundaries of the Empire that the main attack came. Finally, the rulers of the Roman Empire found it necessary to concentrate their strength close to the point of attack, and the capital was moved from Rome to Constantinople: the Roman [42]Empire became the Greek Empire. Thus, as we have seen in the previous chapter, the Balkan Peninsula was chosen as the arena in which an Empire founded in the Italian Peninsula was to die its long, uneasy death. The fate of this Greek Empire had been hardly decided when a new racial element came on the scene, and over the tottering Empire, already fighting fiercely with Bulgar and Serb for its small surviving patch of territory, strode the Turk in the full flush of his youthful strength, giving the last blow to the rule of the Caesars, and threatening all Christian Europe with conquest.

Made thus by the Fates the cockpit of the great struggles for World-Empire, the Balkan Peninsula was doomed to a bloody history: and the doom has not yet passed away. Perhaps it is some unconscious effect on the mind of the pity of this that makes the traveller to the Balkans feel so often a sympathy, almost unreasonable in intensity, for the Balkan peoples. The Balkan acres which they till are home to them. To civilisation those acres are the tournament field for the battles of races and nations.

What is now Bulgaria was in the days of Herodotus inhabited by Thracian and Illyrian [43]tribes. They were united under the strong hand of Philip of Macedonia, and Bulgaria counts him the first great figure in her confused national history, and makes a claim to be the heir of his Macedonian Empire. The Romans appeared in Bulgaria during the period of the second war against Carthage. The Roman conquest of the Balkan country was slow, but shortly before the Christian era the Roman provinces of Moesia and Thracia comprised most of what is now Bulgaria.

In the days of Constantine, who removed the capital of his Empire to the Balkan Peninsula, Roman civilisation in what is now Bulgaria was already being swamped by barbarian invasions. The Goths and the Huns ravaged the land fiercely without attempting to colonise it. The Slavs were invaders of another type. They came to stay. It was at the beginning of the third century that the Slavs made their first appearance, and, crossing the Danube, began to settle in the great plains between the river and the Balkan Mountains. Later, they went south-wards and formed colonies among the Thraco-Illyrians, the Roumanians, and the Greeks. This Slav occupation went on for several centuries. [44]In the seventh century of the Christian era a Hunnish tribe reached the banks of the Danube. It is known that this tribe came from the Volga and, crossing Russia, proceeded towards ancient Moesia, where it took possession of the whole north-east territory of the Balkans between the Danube and the Black Sea. These were the Bulgars, or Bolgars. The Slavs had already imposed on the races they had found in the Peninsula their language and customs. The Bulgars, too, assumed the language of the Slavs, and some of their customs. The Bulgars, however, gave their name to the mixed race, and assumed the political supremacy.

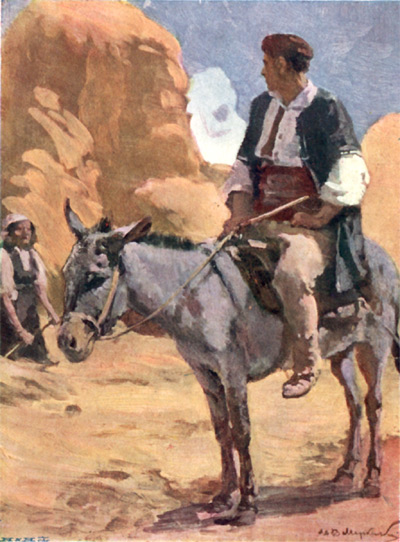

The analogy I have before suggested of the Norman invasion of England and the Bulgar invasion of Bulgaria generally holds good. The Slavs were a people who tilled the soil, cherished free institutions, fought on foot, were gentle in character. The Bulgars were nomads and pastoralists, obeying despotic chiefs, fighting as cavalry. They came as conquerors, but in time were absorbed in the more stable Slavonic type.

Without a doubt the Bulgars were racially nearly akin to the Turks—first cousins at least. Mingling with the Slavs they adopted their [45]language and many of their customs. But something of the Turk survives to this day in the character of the Bulgarian people. It shows particularly in their treatment of their women. Though the Bulgarian is monogamic he submits his wife to an almost harem discipline. Once married she lives for the family alone. Though she does not wear a veil in the streets it is not customary for her to go out from her home except with her husband, nor to receive company except in his presence, nor to frequent theatres, restaurants, or other places of public amusement. There is thus no social life in Bulgaria in the European sense of the term, and there is great scope there for a campaign for "women's rights."

The Bulgars taking command over the Slav population in Bulgaria began a warfare against the enfeebled Greek Empire. That Empire gave up Moesia to the Bulgarian King, Isperich, and agreed to pay him a tribute, it being the custom of the degenerate descendants of the Roman Empire of the period thus to attempt to buy safety with bribes. The Emperor Justinian II. stopped this tribute, and a war followed, in which the Bulgarians were successful, and Justinian lost his throne and was driven to exile. Later, [46]Justinian made another treaty with the Bulgarians and offered his daughter in marriage to the new Bulgarian King, Tervel, and with Bulgarian help he was restored to his throne. But war between the Bulgars and the Empire was chronic. To quote a Bulgarian chronicler:

The chief characteristics of the Bulgars were warlike virtues, discipline, patriotism, and enthusiasm. The Bulgarian kings brought their victorious armies to the gates of Constantinople, whose very existence they threatened. The Greek Emperor sought their friendship, and even consented to pay them tribute.

Bulgaria attained her greatest empire in the reign of King Kroum. Between King Isperich and King Kroum, however, Bulgaria had many ups and downs. The Bulgarian King, Kormisos, once almost reached the walls of Constantinople. But trouble among his own people prevented his victories being pushed home. Then a series of civil wars in Bulgaria weakened the nation, and a great section of it migrated to Asia Minor. The Roman Emperor, Constantine V., took this occasion to exact a full revenge for previous Bulgar attacks on Constantinople. The Bulgar army was routed, and an invading force carried the torch into every Bulgarian town. A new [47]Bulgar King, Cerig, restored his country's position somewhat by a secretly plotted massacre of all its enemies within its boundaries. The Empress Irene then ascended the Imperial throne at Constantinople and found herself unable to withstand the Bulgar power, and went back to the system of paying tribute to the Bulgarians as the price of safety.

King Kroum next ascended the throne of Bulgaria and, capable and savage warrior as he was, raised its power vastly. He defeated and slew the Greek Emperor, Nicephorus, in battle, and captured Sofia (809), the present capital of Bulgaria. Warfare was savage in those days, and between the Bulgars and the Greek emperors particularly savage. The defeated Imperial army was massacred to a man, from the Emperor down to the foot-soldier. King Kroum afterwards used the skull of the descendant of the Caesars as a drinking-cup.

A siege of Constantinople followed the defeat and death of the Emperor Nicephorus. The Bulgars affrighted the defenders of the city by their fierce orgies before the walls, by the human sacrifices they offered up in their sight, and by the resolute refusal of all quarter in the field. [48]The Empire tried to buy off the Bulgars with the promise of an annual tribute of gold, of cloth, and of young girls. The invaders finally retired with a great booty, and the death of King Kroum soon after relieved the anxiety of Constantinople.

Bulgaria seems now (the ninth century) to have suffered again from internal dissensions. These arose mostly out of religious issues. Many of the Slavs had become Christians, and some of the Bulgars also adopted the new faith. For a time the kings tried to crush out Christianity by persecutions, but in 864 the Bulgarian King, Boris, adopted Christianity—some say converted by his sister, who had been a prisoner of the Greeks and was baptized by them. His adherence to Christianity was announced in a treaty with the Greek Emperor, Michael III. Some of King Boris's subjects kept their affection for paganism and objected to the conversion of their king. Following the customs of the time they were all massacred, and Bulgaria became thus a wholly Christian kingdom.

King Boris, whom the Bulgarians look up to as the actual founder of the Bulgarian nation of to-day, hesitated long as to whether he should [49]attach himself and his nation to the Roman or to the Greek branch of the Christian Church. He made the issue a matter of close bargaining. The Church was sought which was willing to allow to Bulgaria the highest degree of ecclesiastical independence, and which seemed to offer as the price of adhesion the greatest degree of political advantage.

At first the Greek Church would not allow Bulgaria to have a Patriarch of her own. King Boris sent, then, a deputation to Pope Nicholas at Rome, seeking if a better national bargain could be made there. Two bishops came over from Rome to negotiate. But in time King Boris veered back to a policy of attaching himself to the Greek Church, which now offered Bulgaria an Archbishop with a rank in the Church second only to that of the Greek Patriarch. In 869 Bulgaria definitely threw in her lot with the Greek Church.

Curiously those old religious controversies of the ninth century were revived in the nineteenth. Bulgaria has a persistent sense of nationalism, and looks upon religion largely in a national sense. In the ninth century her first care in changing her religion was to safeguard national [50]interests. In the nineteenth century the first great concession she wrung from her Turkish masters was the setting up (1870) of a Bulgarian Exarch to be the official head of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church independent of the Greek Patriarch. A little later in the days of her freedom, when to her Roman Catholic ruler, King Ferdinand, was born a son (named Boris after the first Christian king of Bulgaria), the Bulgarians had him transferred in 1896 from the Roman to the Greek Church as a matter of national policy.

The controversy to-day between "Patriarchate" adherents of the Orthodox Church—i.e. Greeks, and the Exarchate adherents—i.e. Bulgarians, is perhaps the most bitter of all Balkan controversies. I have found it in places transcending far the religious gap between Turk and Christian, and in that particularly stormy North Macedonian corner of the Balkans a Patriarchate man gives first place in his hatred to an Exarchate man and second place to a Turk; and the Exarchate man reciprocates in like manner. Yet, as the Bulgarians insist, "the autonomous orthodox Bulgarian Church forms an inseparable part of the Holy Orthodox Church."

[51]The Bulgarian Exarchate used to comprise all the Bulgarian dioceses in the provinces of the Turkish Empire, as they were enumerated explicitly or in general terms by the Firman of 1870 as well as the dioceses of the Bulgarian Principality. Most of the orthodox Bulgarian population in Turkey recognise the authority of the Exarchate, but some still owe allegiance to the Greek Patriarchate. What the religious position will be now that the wars of 1912–1913 have changed boundaries so considerably it is hard to say. The Exarchate dioceses which used to be in Turkish territory but are now in Bulgarian territory, will, of course, pass into the main current of Bulgarian church life. But those Exarchate dioceses which have passed to Servia and to Greece will probably not find toleration.

King Boris of Bulgaria having raised his country to a great fame, and having endowed it with a national church, retired to a monastery in 888 to make his peace with the next world. His son Vladimir succeeded to the throne, but ruled so unwisely that King Boris came back from the cloister to depose Vladimir and to set in his stead upon the throne Simeon, who created the first Bulgarian Empire.

King Simeon reigned in Bulgaria thirty-four years, and raised his country during that time to the highest point of power it ever reached. Simeon had been educated at Constantinople and had learned all that the civilisation of the Grecian Empire could teach except a love and respect for the Grecian rule. He designed the overthrow of the tottering Grecian Empire, and dreamed of Bulgaria as the heir to the power of the Caesars.

When Simeon came to the throne, for many years the Grecian Empire and Bulgaria had been at peace. But a trade grievance soon enabled Simeon to enter upon a war against the feeble Greek Emperor then on the throne in Constantinople—Leo, known as the Philosopher. The Grecian forces were defeated and, following the [53]ferocious Balkan custom of the times, the Grecian prisoners were all mutilated by having their noses cut off, and thus returned to their city. Constantinople in desperation appealed for help to the Magyars, who had recently burst into Europe from the steppes of Russia and occupied the land north of the Danube. The Magyars responded to the appeal, and at first were successful against the Bulgars, but King Simeon's strategy overcame them in the final stages of the campaign. He took advantage then of the temporary absence of their army in the west, and descended upon their homes in the region now known as Bessarabia and massacred all their wives and children. This act of savage cruelty drove the Magyars away finally from the Danube, and they migrated north and west to found the present kingdom of Hungary.

Relieved of the fear of the Magyars, King Simeon now attacked the Grecian Empire again, captured Adrianople, and laid siege to Constantinople. There were two emperors in the city then, in succession to Leo the Philosopher—Romanus Lecapenus and Constantine Porphyrogenitus. For all the grandeur of their names they rivalled one another in incompetency and [54]timidity. Simeon was able to force upon the Grecian Empire a humiliating peace, which made Bulgaria now the paramount Power in the Balkans, since Servia had been already subdued by her arms. From the Roman Pope, Simeon received authority to be called "Czar of the Bulgarians and Autocrat of the Greeks." His capital at Preslav—now in ruins—was in his time one of the great cities of Europe, and a contemporary description of his palace says:

If a stranger coming from afar enters the outer court of the princely dwelling, he will be amazed, and ask many a question as he walks up to the gates. And if he goes within, he will see on either side buildings decorated with stone and wainscoted with wood of various colours. And if he goes yet farther into the courtyard he will behold lofty palaces and churches, bedecked with countless stones and wood and frescoes without, and with marble and copper and silver and gold within. Such grandeur he has never seen before, for in his own land there are only miserable huts of straw. Beside himself with astonishment, he will scarce believe his eyes. But if he perchance espy the prince sitting in his robe covered with pearls, with a chain of coins round his neck and bracelets on his wrists, girt about with a purple girdle and a sword of gold at his side, while on either hand his nobles are seated with golden chains, girdles, and bracelets upon them; then will he answer when one asks him on his return home what he has seen: [55]"I know not how to describe it; only thine own eyes could comprehend such splendour."

Under Simeon, art and literature flourished (in a Middle Ages sense) in Bulgaria; the Cyrillic alphabet—still used in Russia, Bulgaria, and Servia—had supplanted the Greek alphabet and had added to the growing sense of national consciousness. Simeon encouraged the production of books, and tradition credits him with having himself translated into the Slav language some of the writings of St. Chrysostom.

But all this Bulgarian prosperity had a serious check when Simeon died in 927 and the Czar Peter ascended the throne. Scarcely was Simeon cold in his grave before internal struggles had begun, owing to the jealousies of some of the nobles and their spirit of adventure. The boyars (knights) of Bulgaria had always had great authority. Now they took advantage of a monarch who was more suited for the cloister than the Court to revive old pretensions to independent power. Czar Peter turned to the Greek Empire for help, and sought to strengthen his position at home by a marriage with the grand-daughter of the Emperor Romanus Lecapenus. That policy served until a vigorous Greek Emperor came to [56]the throne at Constantinople and set himself to avenge the victories of Simeon. The Greek Emperor called in the aid of the northern Russians against their kinsfolk the Bulgarian Slavs. There followed a typical Balkan year of war. The Russians succeeded only too well against the Bulgarians, and then the Greeks, in fear, joined with the Bulgarians to resist their further progress. Then the Servians took advantage of the war to shake off the Bulgarian suzerainty and regain their independence. An opposition party in Bulgaria, disgusted with the misfortunes which had befallen their country under Peter, added to these misfortunes by a revolt, and seceded to found the kingdom of Western Bulgaria under the boyar Shishman Mokar (963). To add to the troubles of the Balkans, the Bogomil heresy appeared, dividing further the strength of the Bulgarian nation. The Bogomils were the first of a long series of Slavonic fanatics, ancestors in spirit of the Doukhobors, the Stundists, and the Tolstoyans of our days, preaching the hermit life as the only truly holy one, forbidding marriage as well as war and the eating of meat. It was with such dissensions among the Christian states of the Balkans that [57]the way was prepared for the coming of the Turk to the Peninsula.

In 969 Boris II. followed Peter on the Bulgarian throne. He was faced by a new Russian invasion and by an attack from Czar David of Western Bulgaria. This latter attack he beat off, but was overwhelmed before the tide of Russian invasion and himself captured in battle. The Russians passed over Bulgaria to attack Constantinople, and that brought the Greeks into line with the Bulgarians to resist the invader. The Emperor John Zemissius made bold war upon the Russians, and captured from them their Bulgarian prisoner, the Czar Boris II. The Greek Emperor made no magnanimous use of his victory. He deposed the Bulgarian Czar and the Bulgarian Patriarch, emasculated the Czar's brother, and turned Bulgaria into a Greek province. Only in the rebel province of West Bulgaria did Bulgarian independence at this time survive, and from that province there arose in time a deliverer, the Czar Samuel, who was the fourth son of that boyar Shishman who founded the Western Bulgarian kingdom. At the beginning of his reign, in 976, Samuel had control only over the territory which is now known as [58]Macedonia, but soon he united to it all the old Empire of Bulgaria, and stretched the sway of his race over much of the land which is now comprised in Albania, Greece, and Servia. He began, then, a stern war with the Greek Emperor, Basil II., known to history as "the Bulgar-slayer," against whom is alleged a cruelty horrible even for the Balkans.

Capturing a Bulgarian army of over 10,000 men, Basil II. had all the soldiers blinded, leaving to each of their centurions, however, one eye, so that the mutilated men might be led back to their own country. A realistically horrible picture in the Sofia National Gallery commemorates this classic horror.

The war between the Czar Samuel and the Emperor Basil II. was marked by fluctuating fortunes. At first the Bulgarians were altogether successful, and in 981 Basil was so completely defeated that for fifteen years he was obliged to leave Samuel as the real master of the Balkan Peninsula. Then the tide turned. Near Thermopylae, Samuel was decisively defeated by the Greeks, and soon after found his Empire reduced to the dimensions of Albania and West Macedonia. War troubles that the Greeks had with [59]Asia brought to the Czar Samuel a brief respite, but a campaign in 1014—this was the one marked by the blinding of the captive Bulgarian army—shattered finally his power. He died that year heart-broken, it is said, at the sight of the return of his blinded army.

Thus, to quote a Bulgarian chronicle:

In 1015 Bulgaria was brought to subjection. A new state of things began for the Bulgarians, who till then had never felt the control of an enemy. The people longed for liberty, and there were many attempts at revolt. Towards 1186, two brothers, John and Peter Assen, raised a revolt and succeeded in re-establishing the ancient kingdom, choosing as capital Tirnova, their native town. It was then that Tirnova became what it still remains, the historic town of Bulgaria. The reign of John and Peter Assen was a brilliant time for Bulgaria. Art and literature flourished as never before, and commerce developed to a considerable extent. Once more the Bulgarian Empire was respected and feared abroad.

But this Bulgarian Empire was doomed to as short a life as its predecessor, though for a brief while it held out the illusionary hope of permanency. Bulgaria, from the Danube to the Rhodope Mountains, was won from the Greeks, and John Assen was powerful enough to dream of entering into alliance with the Emperor [60]Frederick Barbarossa. An assassin's sword, however, ended John Assen's life prematurely. He was followed on the throne by his brother Peter. He, too, was assassinated, and was succeeded by his brother Kalojan, who had all the warlike virtues of John Assen, and re-established the Bulgarian Empire with territories which embraced more than half the whole Balkan Peninsula. Seeking to add to the reality of power some validity of title, Kalojan entered into negotiations with the Pope of Rome, made his submission to the Roman Church, and was crowned by a Papal nuncio as king.

It was about this time that Constantinople was captured by the Crusaders, and Count Baldwin of Flanders ascended the throne of the Caesars. The Greeks, driven from their capital but still holding some territory, made an alliance with Kalojan, and once again Greek and Bulgar fought side by side, defeating the Franks and taking the Emperor Baldwin prisoner. Then the alliance ended—never, it seems, can Bulgar and Greek be long at peace—and a war raged between the Greek Empire and Bulgaria, until in 1207 Kalojan was assassinated.

A brief period of prosperity continued for [61]Bulgaria while John Assen II. was on the throne. He was the most civilised and humane of all the rulers of ancient Bulgaria, and there is no stain of a massacre or a murder remembered against his name. He made wars reluctantly, but always successfully. An inscription in a church at Tirnova records his prowess:

In the year 1230, I, John Assen, Czar and Autocrat of the Bulgarians, obedient to God in Christ, son of the old Assen, have built this most worthy church from its foundations, and completely decked it with paintings in honour of the Forty holy Martyrs, by whose help, in the 12th year of my reign, when the church had just been painted, I set out to Roumania to the war and smote the Greek army and took captive the Czar Theodore Komnenus with all his nobles. And all lands have I conquered from Adrianople to Durazzo, the Greek, the Albanian, and the Servian land. Only the towns round Constantinople and that city itself did the Franks hold; but these too bowed themselves beneath the hand of my sovereignty, for they had no other Czar but me, and prolonged their days according to my will, as God had so ordained. For without Him no word or work is accomplished. To Him be honour for ever. Amen.

John Assen II. was a great administrator as well as a great soldier. Whilst he declared the Church of Bulgaria independent, repudiating alike the Churches of Rome and of Constantinople, he tolerated all religions and gave sound en[62]couragement to education. With his death passed away the last of the glory of ancient Bulgaria. Her story now was to be of almost unrelieved misfortune until the culminating misery of the Turkish conquest.

Internal dissensions, wars with the Venetians, the Hungarians, the Serbs, the Greeks, the Tartars,—all these vexed Bulgaria. The country became subject for a time to the Tartars, then recovered its independence, then came under the dominion of Servia after the battle of Kostendil (1330). The Servians, closely akin by blood, proved kind conquerors, and for some years the two Slav peoples of the Balkans kept peace by a common policy in which Bulgaria, if dependent, was not enslaved. But the Turk was rapidly pouring into Europe. In 1366 the Bulgarian Czar, Sisman III., agreed to become the vassal of the Turkish Sultan Murad, and the centuries of subjection to the Turk began. After the battle of Kossovo the grip of the Turk on Bulgaria was tightened. Tirnova was captured, the nobles of the nation massacred, the national freedom obliterated. The desire for independence barely survived. But there was one happy circumstance:

[63]"It is a noteworthy fact," writes a Bulgarian authority, "that the Osmanlis, being themselves but little civilised, did not attempt to assimilate the Bulgarians in the sense in which civilised nations try to effect the intellectual and ethnic assimilation of a subject race. Except in isolated cases, where Bulgarian girls or young men were carried off and forced to adopt Mohammedanism, the Government never took any general measures to impose Mohammedanism or assimilate the Bulgarians to the Moslems. The Turks prided themselves on keeping apart from the Bulgarians, and this was fortunate for our nationality. Contented with their political supremacy and pleased to feel themselves masters, the Turks did not trouble about the spiritual life of the rayas, except to try to trample out all desires for independence. All these circumstances contributed to allow the Bulgarian people, crushed and ground down by the Turkish yoke, to concentrate and preserve their own inner spiritual life. They formed religious communities attached to the churches. These had a certain amount of autonomy, and, beside seeing after the churches, could keep schools. The national literature, full of the most poetic melancholy, handed down from generation to generation and developed by tradition, still tells us of the life of the Bulgarians under the Ottoman yoke. In these popular songs, the memory of the ancient Bulgarian kingdom is mingled with the sufferings of the present hour. The songs of this period are remarkable for the Oriental character of their tunes, and this is almost the sole trace of Moslem influence.

"In spite of the vigilance of the Turks, the religious associations served as centres to keep alive the national feeling. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, [64]when Russia declared war against Turkey (1827), Bulgaria awoke."

From 1366 to 1827 Bulgaria had been enslaved by the Turk. Now within the space of a few days and with hardly an effort on her own behalf, she was suddenly to be restored to independence.

Significantly enough, the first sign of a renaissance of Bulgarian national feeling was an agitation not against the Turks but the Greeks. Patriotic Bulgarians, under the Sublime Porte, sought to re-establish their old National Church and shake it free from its subjection to the Greek Patriarch at Constantinople. The Sublime Porte was induced to look upon this demand with favour. A step which promised to emphasise the divisions between the Christians evidently should be of advantage to the Turks. The Greek Patriarch was urged to consent to the appointment of a Bulgarian bishop. He refused. In the face of that refusal Turkey acted as the creator of a new Christian Church, and in 1870 a firman of the Sultan created the Bulgarian Exarchate, and Bulgaria had again a national [66]ecclesiastical organisation. Two years later the first Exarch was elected by the Bulgarian clergy. But gratitude for this religious concession did not extinguish the longings for political independence of the Bulgarian people. When a Christian insurrection broke out in Herzegovina against Turkey in 1875, the Bulgarian patriots rose in arms in different parts of their country. The massacres of Batak were the Turkish response, those "Bulgarian atrocities" which sent a shudder through all Europe and set a term to Turkish rule over the Christian populations in her European provinces.