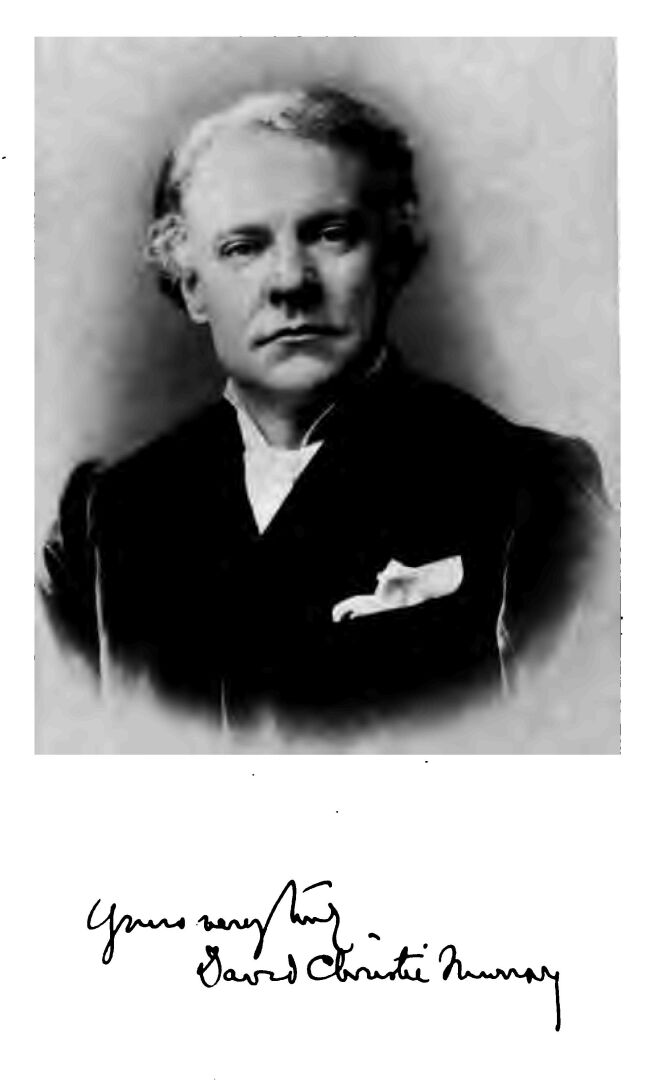

Title: Recollections

Author: David Christie Murray

Release date: August 1, 2007 [eBook #22200]

Most recently updated: February 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

Illustrations

The Unlucky Day of the Fool's Month—High Street, West

Bromwich—My First Pedestrian Triumph—The Common English

Bracken—The Sense of Beauty.

I remember that in a fit of petulance at some childish misdemeanour, my mother once told me that I came into the world on the unlucky day of the fool's month. It was her picturesque way of saying that I was born on the thirteenth of April. I have often since had occasion to think that there was a wealth of prophetic wisdom in the phrase which neither she nor I suspected at the time.

I did the world the poor service of being born into it in the year 1847, in a house not now to be identified in the straggling High Street of West Bromwich, which in those days was a rather doleful hybrid of a place—neither town nor country. It is a compact business-like town now, and its spreading industries have defaced the lovely fringe of country which used to be around it.

Its great peculiarity to a thoughtful child lay in the fact that even at his small rate of progress he could pass in an hour from the clink, clink, clink on the anvils of the poor nailmakers, who worked in their own sordid back kitchens about the Ling or Virgin's End, to a rural retirement and quiet as complete as you may find to-day about Charlcote or Arden, or any other nook of the beautiful Shakespeare country. Since the great South Staffordshire coal fault was circumvented, nearly all the wide reaches of rural land which I remember are overgrown and defaced by labour. The diamond stream in which I used to bathe as a boy, where you could have counted the pebbles at the bottom, was running ink, and giving forth vile odours, when last I saw it. But fifty years ago, or more, there was the most exquisite green fringe to that fire-rotted, smoke-stained, dirty mantle of a Black Country. In the extreme stillness of the summer fields, and more especially, as I seem to remember, in a certain memorable hush which came when afternoon was shading into evening, you could hear the clank of pig-iron which was being loaded into the boats on the canal at Bromford, quite two miles away, and the thump of a steam hammer at Dawes's foundry.

I have begun many a child's ramble by a walk down Bromford Lane, to look in at the half-naked figures there sweating and toiling at the puddling furnaces, and have brought it to an end in the middle of the fairy ring on Stephenson's hills, only a couple of miles away, in what felt like the very heart of nature's solitude. Thus the old parish, which was not by any means an ideal place to be born and bred in, had its compensations for a holiday schoolboy who had Milton, and Klopstock, and Bunyan at his finger-ends, and had hell and the plains of heaven within an easy ramble from the paternal doorstep. But the special memory about which I set out to write was the one which immediately follows on the baby experience already recorded. It is almost as brief and isolated in itself; but I know by after association precisely where it took place, and I am almost persuaded that I know who was my companion.

I think it is Mr Ruskin who speaks of our rural hedgerows as having been the pride and glory of our English fields, and the shame and disgrace of English husbandry. In the days I write of, they were veritable flower-gardens in their proper season. What with the great saucer-shaped elderberry blooms, and the pink and white dogroses, and the honeysuckle, and the white and purple foxgloves, and harebell and bluebell, and the starlike yellow-eyed daisy, there was an unending harvest for hand and eye. But the observation of all these things came later. Below the hedges the common English bracken grew, in occasional profusion, and it was a young growing spray of this plant which excited in my mind the very first sense of beauty I had ever known. It was curved in a gentle suggestion of an interrogation note. In colour, it was of a greenish-red and a very gentle yet luxuriant green. It was covered with a harmless baby down, and it was decorated at the curved tip with a crown-shaped scroll. There is really no need in the world to describe it, for one supposes that even the most inveterate Cockney has, at one time or another, seen the first tender offshoot of the commonest fern which grows in England.

From the time at which I achieved my first pedestrian triumph until I looked at this delight and wonder, I remember nothing. A year or two had intervened, and I was able to toddle about unaided; but, for anything I can actually recall, I might as well have been growing in my sleep. But I shall never forget it, and I have never experienced anything like it since. Whether I could at that time think in words at all, I do not know; but the beauty, the sense of the charm of the slender, tender thing went into my heart with an actual pang of pleasure, and my companion reproved me for crying about nothing. I don't remember crying; but I recall the question, and I know that nothing has ever since moved me in the same way.

I was about nineteen years of age, I think, when I first awoke to the fact that I had been born shortsighted. I bad had a year in the army, and when we were at the targets, or were out at judging-distance drill, I was aware that I did not see things at all as the musketry instructor represented them. But it happened one starlight night, after I had returned to civilian life, that a companion of little more than my own age, who had always worn spectacles in my remembrance of him, began to talk about the splendid brilliance of the heavens. I could discern a certain milky radiance, with here and there a dim twinkle in it, but no more. I borrowed my comrade's glasses, and I looked. The whole thing sprang at me, but rather with a sense of awe and wonder than of beauty; and even this much greater episode left the first impression of the child unchanged.

There is, or used to be, a little pleasure-steamer which starts at stated times for a voyage on Lake Wakatipu in New Zealand. For a while it passes along a gloomy channel which is bounded on either side by dark and lofty rocks of a forbidding aspect. This passage being cleared, the steamer bears away to the left, across the lake, and, beyond the jutting promontory near at hand, there lifts into sight on a fair day the first mountain of the Glenorchy Range. When I first saw it, the sky at the horizon was almost white; but the peaks of the distant mountains had, as Shakespeare says, a whiter hue than white, and through field-glasses its outlines could be perfectly distinguished. Then swung into sight a second mountain, and a third, and a fourth, and so on, in a progression which began to look endless. There is a form of delight which is very painful to endure, and I do not know that I ever experienced it more keenly than here. The huge snow-capped range gliding slowly up, “the way of grand, dull, Odyssean ghosts,” was impressive, and splendid, and majestic beyond anything I have known in a life which has been rich in travel; but if I want, at a fatigued or dispirited hour, to bathe my spirit clear in the memory of beautiful things seen, I go back, because I cannot help it, to that tender little fern-frond in a lane on the edge of the Black Country, which brought to me, first of all, the message that there is such a thing as beauty in the world.

My Father—The Murrays—The Courage of Childhood—The Girl

from the Workhouse—Witchcraft—The Dudley Devil—The

Deformed Methodist—A Child's idea of the Creator—The

Policeman—Sir Ernest Spencer's Donkey—The High Street Pork

Butcher.

My father was a printer and stationer, and would have been a bookseller if there had been any book buyers in the region. There was a good deal of unsaleable literary stock on the dusty shelves. I remember The Wealth of Nations, Paley's Evidences of Christianity, Locke on the Human Understanding, and a long row of the dramatists of the seventeenth century. I burrowed into all these with zeal, and acquired in very early childhood an omnivorous appetite for books which has never left me.

There was a family legend, the rights and wrongs of which are long since drowned in mist, to the effect that our little Staffordshire branch of the great Murray family belonged to the elder and the higher, and the titular rights of the Dukedom of Athol were held by a cadet of the house. My father's elder brother, Adam Goudie Murray, professed to hold this belief stoutly, and he and the reigning duke of a century ago had a humorous spar with each other about it on occasion. “I presume your Grace is still living in my hoose,” Adam would say.

“Ay, I'm still there, Adam,” the duke would answer, and the jest was kept up until the old nobleman died. Sir Bernard Burke knew of the story, but when as a matter of curiosity I broached the question to him, he said there were too many broken links in the chain of evidence to make it worth investigation. My father had, or humorously affected, a sort of faith in it, and used to say that we were princes in disguise. The disguise was certainly complete, for the struggle for life was severe and constant, but there was enough in the vague rumour to excite the imagination of a child, and I know that I built a thousand airy day-dreams on it.

To me the most momentous episodes of life appear to resolve themselves naturally into first occasions. Those times at which we first feel, think, act, or experience in any given way, form the true stepping-stones of life. Memory is one of the most capricious of the faculties. There is a well-known philosophical theory to the effect that nothing is actually forgotten or forgetable which has once imprinted itself upon the mind. But, bar myself, I do not remember to have encountered anybody who professed to recall his very earliest triumph in pedestrianism—the first successful independent stagger on his feet. When I have sometimes claimed that memory carries me back so far, I have been told that the impression is an afterthought, or an imagination, or a remembrance of the achievement of some younger child. I know better. It is an actual little fragment of my own experience, and nothing which ever befell me in my whole lifetime is more precise or definite. I do not know who held my petticoats bunched up behind to steady me for the start, nor who held out a roughened finger to entice me. But I remember the grip, and the feel of the finger when I reached it, as well as I remember anything. And what makes the small experience so very definite is, that after all this lapse of time I can still feel the sense of peril and adventure, and the ringing self-applause which filled me when the task was successfully accomplished. There was a fire in the grate on my right hand side, and beneath my feet there was a rug which was made up of hundreds of rough loops of parti-coloured cloth; and it was the idea of getting over those loops which frightened me, and brought its proper spice of adventure into the business. There is nothing before this, and for two or three years, as I should guess, there is nothing after it. That little firelit episode of infancy is isolated in the midst of an impenetrable dark.

Where a child is not beaten, or bullied, or cautioned overmuch, it is almost always very courageous to begin with. Where it survives the innumerable mishaps incident to the career of what Tennyson calls “dauntless infancy,” it learns many lessons of caution. But the great faculty of cowardice, which most grown men have developed in a hundred forms, is no part of the child's original stock in trade. Even cowardice, in its own degree, is a wholesome thing, because it is a part and portion of that self-protective instinct which helps towards the preservation of the individual of the race. But it would be a good thing to place, if such a thing were possible, a complete embargo on its importation into the infant kingdom. I suppose the true faculty for being afraid belongs to very few people. There are many forms of genius, and it is very likely, I believe, that the genius for a true cowardice is as rare as the genius for writing great verse, or constructing a great story, or guiding the ship of state through the crises of tempest to a safe harbour. But every human faculty may be cultivated, and this is a field in which, with least effort, and with least expenditure of seed, you may reap the fullest crop.

Whilst I was yet a very little fellow, a certain big-boned, well-fleshed, waddling wench from the local workhouse became a unit in my mother's household. Her chief occupation seemed to be to instruct my brothers and sisters and myself in various and many methods of being terrified. Three score years ago there was, in that part of the country, a fascinating belief in witchcraft. There was in our near neighbourhood, for example, a person known as the Dudley Devil, who could bewitch cattle, and cause milch kine to yield blood. He had philtres of all sorts—noxious and innocuous—and it was currently believed that he went lame because, in the character of an old dog-fox, he had been shot by an irate farmer whose hen-roost he had robbed beyond the bounds of patience. He used to discover places where objects were hidden which had been stolen from local farmhouses, and he was reckoned to do this by certain forms of magical incantation. In my maturer mind, I am disposed to believe that he was a professional receiver of stolen goods, and I am pretty sure that the modern police would have made short work of him. But from the time that foolish, fat scullion came into the household service, we were all impressed with a dreadful sense of this gentleman's potentialities for evil; and darkened rooms and passages about the house, into which we had hitherto ventured without any hint of fear, were suddenly and horribly alive with this man's presence.

Speaking for myself, as I have sole right to do, I know that he haunted every place of darkness. He positively peopled the back kitchen to which we went for coals. He haunted a little larder on the left, and stood on each of the three steps which led down to its red brick floor, whilst at the same instant he was horribly ready to pounce upon one from the rear; was waiting in the doorway just in front; was crouching in each corner of the darkened chamber, and hidden in the chimney. That fat, foolish scullion slept in the same room with my brother and myself. He, as I find by reference to contemporary annals, was seven at this time, and I was five, and we got to know afterwards that the sprawling wench grew hungry in the night-time, and went downstairs to filch heels of loaves and cheese, or anything our rather spare household economy left open to her petty larcenies. And in order that these small depredations should be hidden, she used to play the ghost upon us, and I suppose it to be a literal fact that many and many a time when she stole back to our room, and found us awake and quaking, she must have driven us into a clean swoon of terror by the very simple expedient of drawing up the hinder part of her nightdress, and making a ghostly head-dress of it about her face. That I fainted many a time out of sheer horror at this apparition, I am quite certain; but the sense of real fear was, after all, left in reserve. I had rambled alone, as children will, along the High Street on a lovely summer day, each sight, and scent, and sound of which comes to me at this moment with a curious distinctness, and I had turned at the corner; had wandered along New Street, which by that time was old-fashioned enough to seem aged, even to my eyes; had diverged into Walsall Street, which was then the shortest way to the real country, and on to the Ten Score; past the Pearl Well, where Cromwell's troops once stopped to drink; through Church Vale, and on to Perry Bar, and even past the Horns of Queeslett, beyond which lay a plain road to Sutton Coldfield, a place full of wonder and magic, and already memorable to a reading child through its association with one Shakespeare, and a Sir John Falstaff, who afterwards became more intimate companions.

I had never been so far from home before, and the sense of adventure was very strong upon me. By-and-bye, I found myself in what I still remember as a sort of primeval forest, though a broad country lane was cut between the umbrageous shade on either side. I saw a rabbit cross the road, and I saw a slow weasel track him, and heard the squeak of despair which bunny uttered when the fascinating pursuer, as I now imagine, first fixed upon him what Mr Swinburne calls “the bitter blossom of a kiss.” I very clearly remember an adder, with a bunch of its young, disporting in the sunlight; but there was nothing to alarm a child, and everything to charm and enlist the fancy. The sunlight fell broadly along the route. Birds were singing, and butterflies were fanning their feathery, irresponsible way from shade to shade. I saw my first dragonfly that day, and tried to catch him in my cap, but he evaded me. All on a sudden, the prospect changed. A cloud floated over the sun, and a sort of preliminary waiting horror took possession of the harmless woods on either side. Just there the road swerved, and I could hear a halting footstep coming. Somehow, the Dudley Devil was associated in my mind with that halting step, and there was I, in the middle of a waste universe, in which all the bird voices had suddenly grown silent, and the companionable insects had ceased to hum and flutter, left to await the coming of this awful creature. The stammering step came round the bend of the lane, and I saw for the first time a person whom I grew to respect and pity later on, but who struck me then with such an abject sense of terror as I have sometimes since experienced in dreams.

One might have travelled far before meeting a more harmless creature. He was on the local Plan of the Wesleyan Methodists, as I found out afterwards. He had been a metal-worker of some sort, and the victim of an explosion which had wrecked one side of his face and figure, and had made nothing less than a ghastly horror of him. The upward-flying stream of metal had struck him on the cheek and chin, and had left him writhen and distorted there almost beyond imagination. It had literally boiled one eye, which revolved amid its facial seams dead-white in a sightless orbit. The sideward and downward streams had left him with a dangling atrophied arm and a scalded hip, so that he came down on me, with my preconceived ideas about him, like an actual lop-sided demon. I let out one screech, and fled; but even in the act of flight I saw the poor fellow's face, and read in it the bitter regret he felt that the disaster which had befallen him should have made him unbearable to the imagination of a child.

A great many years after, when I was quite a young man, and was invited to read a paper on “Liberty” before a society of earnest Wes-leyan youths who called themselves the “Young Bereans,” this identical man stood up to take a part in the discussion, and I knew him in a flash. He began his speech by saying something about the inscrutable designs of Providence, and I recall even now some fragmentary idea of the words he used. “I was a handsome lad to begin with,” he said, “but God saw fit to deform me, and to make me what I am.” And now, when I am settling down to these reminiscences in late middle age, the most dreadful waking sense of real horror, and the first real touch of human pity, seem to meet each other, and to blend.

It is fully half a century ago, for I could not have been quite six years of age, when my brother Will and I were taken to chapel on one very well-remembered Sunday evening. The preacher was the grandfather of a gentleman who now lives in a castle, and does an enormous trade in soap. His theme was the omniscience of the Deity, and he told his simple audience how the same God who made all rolling spheres made the minutest living things also, and all things intermediate. It was a very impressive sermon for a child to listen to, and I can recall a great deal of it to this day. It set my brother's mental apparatus moving, and he thought to such effect that he started a new theory as to the origin of the universe. If God had made all things, it appeared clear to him that somebody must have made God. He suggested that it might have been a policeman. I accepted this idea with an absolutely tranquil faith, and I was immediately certain of the very man. The High Constables Act was not passed until some fourteen or fifteen years later, and it was that Act which finally abolished the old watchman and installed the policeman in his place, even in our remotest villages. But I cannot recall a time when there was not a police barracks in my native High Street. Its inmates were all “bobbies” or “peelers,” out of compliment to “Bobby” Peel, who called them officially into being in 1829. I know no better grounds than those afforded by a baby memory that the particular policeman whom I supposed to have created the Creator was a somewhat remarkable person in his way. He was six feet four in height, for one thing, and he was astonishingly cadaverous. I once found a tremulous occasion to speak to him, and as I looked upward from about the height of his knee at God Almighty's maker, I thought his stature more than Himalayan. I forget what I asked, or what he answered; but the sense of incredible daring is with me still.

I learned later that this elongated solemn coffin of a man was the champion eater of the district I am not inclined to be nice in my remembrance of recorded weights and measures; but they had him registered to an ounce at the “Lewisham Arms,” which was only a yard or two beyond the police barracks, on the road to Handsworth, where he figured as having consumed a shoulder of mutton, a loaf of bread, a pan of potatoes, and a dish of cabbage, each of such and such a weight, in such and such a time. I cannot be sure whether it were at this house of entertainment, or at another in the neighbourhood, where there was a glass case on view in which was displayed the ashy remnant of a pound of tobacco smoked, and the desiccated remnant of a pound of tobacco chewed, within so many given minutes by the local champion in these inviting arts. I am pretty certain now that the local glutton was not identical with the local champion consumer of tobacco; but at that time I heaped all these honours on his head, and my belief in his original responsibility for the launching of the universe was not, so far as I remember, in any way disturbed by the contemplation of these smaller attributes of power.

It is something, even in the flights of baby fancy, to have known and conversed with the origin of all created things. It is perhaps something of a throwback to be forced to the recognition of that prodigious figure as it really was. But, after all, it is not quite impossible that a similar awaking may await the grown man who imagines himself to have mastered something of the real philosophies of life. The cadaverous peeler with the abnormal appetite fades out of recollection, and my next hero is a blacksmith, who, in a countryside once rich in amateur pugilists, had earned a local distinction for himself before he made a settlement for life at the “Farriers' Arms,” in Queen Street. His name was Robert Pearce, and he dawns on me as second hero because of a physical strength which must have been remarkable even when all allowance for the childish ideal is made.

Sir Ernest Spencer, who was for many years the Parliamentary representative of my native parish, was an infant schoolfellow of mine, and on a birthday, or some other such occasion for celebration, his father made him a present of a small donkey; and we two took the beast to Bob Pearce's to be shod. I can see the great, broad-shouldered, hairy farrier at this minute, as if I saw him in a picture, with his smoky shirt thrown wide open at the collar, and his breast as bearded as his chin. When the small beast was trotted in to the farriery, the grimy giant laughed aloud. He stooped, and, placing his great palm under the donkey's belly, he raised the animal in one hand, and poised him at the ceiling, swaying him here and there as if he had been a weathervane in a high and varying wind. I suppose that the donkey was a little donkey; but I am sure that he was only an averagely little donkey, and that not one man in a British regiment could have performed Bob Pearce's feat with any approach to the air of ease and dexterity he gave it. There was no effort at all about the action, and no apparent idea that any exhibition of strength was being offered. There was a conquering comic spontaneity in that exhibition of great muscular power which irresistibly appealed to the imagination, and made the Queen Street farrier a god for years to come.

When I was sent to a regular day-school, many years afterwards, there were legends amongst us of this man's super-normal strength. There was a great lath of a fellow who kept the “Star and Garter” public-house. After all this lapse of time one hopes that one may not hit on any surviving prejudice against the use of names and places. His name was Tom Woolley, and I saw Pearce set his big hand underneath the chair on which he sat, and place him on an ordinary table in a smoke-room for some slight wager of a pint of beer or so. This was one of the ameliorations of the rigours of a committee meeting, of which my father was chairman, called to decide on the form of the public reception of a returning Chartist, who had spent six months in Stafford Gaol for the expression of such extreme opinions as are now daily enunciated in the columns of The Times.

There are no such liars as schoolboys, and no set of men could possibly be found who could as religiously believe each other's lies as they do.

We used to invent for each other's delight stories about this particular hero which went beyond grown-up credence altogether. But there are some few narratives that survive the application of the laws of evidence. For instance, it is recorded that, taking advantage of the temporary absence of a rival smith, he carried away an anvil under his cloak without exciting suspicion that he was bearing any weight at all.

There was a pork butcher in the High Street who sprang to the most dazzling height of fame amongst the schoolboys and other well-practised, self-believing liars of the parish. On the Wednesday the man was as mere and simple a salesman of dead pig as might be found within the limits of the land. On the Thursday he had obliterated the memory of the achievements of Nelson and Six-teen-String Jack. Surveying the circumstances from a considerable distance, I am inclined to think that there was some authenticity in the story which sent the whole parish into a gaping admiration. The tale was that the pork butcher had gone money-hunting on the afternoon of that eventful day which made a hero of him. He had gathered, so the local story ran, something like two hundred pounds, and he made an incautious brag of this fact in the bar-room of the old “Blue Posts,” at Smethwick. Midway up Roebuck Lane, which was then without a house from end to end, three men sprang out upon him from the shadows of the bridge then just newly-erected across the Great Western line of railway, over which, if I remember rightly, no train at that time had ever travelled.

Then that pork butcher proved himself a paladin. He thrust one of his assailants to the rails at the bottom of the cutting with his foot; he laid out another upon the pathway with one prodigious buffet; and, seizing the third by the coat collar, he kicked him half a mile to the police station. Even now, I believe this story to be true, or near the truth; and the sympathetic reader may fancy what we boys made of the hero of it. I have worshipped many people in my time, and I have thrilled at the thought of many splendid deeds; but I have never since reached that high-water mark of hero-worship at which I sailed when I followed that pork butcher down the West Bromwich High Street, and persuaded myself beyond the evidence of my senses that he was ten feet high.

My Father's Printing Office—The Prize Ring—The Fistic Art—

First Steps in Education—A Boy's Reading—Carlyle—Parents

and Children—A School Chum—Technical Education—Plaster

Medallions.

At the age of twelve I was taken from school and set to work in my father's printing office. There must have been a serious fall in the family fortunes about this time, for a year earlier I had been removed from the respectable little private seminary I had hitherto attended and transferred to a school of the roughest sort, where the pupils paid threepence a week apiece to the schoolmaster and we used to give off the result of our lessons in platoons. I learned a little freehand drawing here in the South Kensington manner, for we had a night school which was affiliated to the Art department there, and our teachers came to us once a week from Birmingham. I was secretly very unhappy all this time, and brooded much on the disguised prince idea among my rough companions.

My way to school led me past the Champion of England public-house, kept by the Tipton Slasher—William Perry, from whom Tom Sayers afterwards wrested the honours of the Prize Ring. I got to know that knock-kneed giant well, and took an enormous pride in my acquaintance with him. I remember one summer evening, seeing him eject an enormous fat Frenchman from his door—one of the colony of artificers in glass which lived there at this time. The champion's was the last house in the parish, and beside it lay the Birmingham and Worcester Canal. The big pugilist conducted his captive to the bridge and dumped him down there on the wall, the top of which was all frayed and crumbled by the action of the towing ropes. The fat Frenchman, who was good-naturedly tipsy, picked up a loose half brick and tossed it after the departing Slasher. The missile took him between the shoulders, and he, turning in wrath, flung out one windy buffet at his assailant, and toppled him over the bridge into the canal. There was a momentary flurry, and then a bystander lent the immersed Frenchman one end of a barge-pole, and he was drawn to the side, apparently quite sobered. The Slasher stood guffawing on the bridge, a little crowd of loafers roared with laughter, and the fat victim of the incident seemed as much amused by it as anybody. He struck a burlesque fighting attitude on the tow-path, and then went dripping homeward.

This small episode was quite in tune with the place and the time, and nobody thought it worth more than a laugh. The good old Prize Ring was even then sinking into disrepute and only the giant fight of years later, when England and America were matched against each other in the persons of Tom Sayers and The Benecia Boy, gave it a momentary flicker before, as it were, it fell into the socket, and one form of British valour died.

The Slasher was, of course, the central luminary, but there were scores and scores of lesser lights revolving round him. The fistic art in those days was very generally practised and a stand-up fight between two local champions was often undertaken for the mere love of the thing. It was not at all an uncommon practice for a party of eight to be brought together, lots would be drawn, and four would stand up against four, then two against two, and the survivors of the competition would fight it out between them. I witnessed many of these contests and can bear evidence that there was less rowdyism displayed than can be noted any day amongst the crowd on a modern race-course. It was good, serious, scientific fighting and the rules of the Ring were strictly observed. Any violation of them would indeed have aroused the spontaneous anger of the crowd, for the laws of the game were known to everybody and were universally respected. I hope I am not going to sermonise often in the course of this narrative, but I have always thought that the legislative meddling with the Prize Ring was a grave mistake. The hooliganism of modern days was absolutely unknown at the time of which I write and the roughest crowd might be relied upon to see fair play between any chance pair of combatants. But the best of the sport was that it was commonly carried on out of that pure hardihood which at one time made the rougher sort of Englishman the pick of the world for valour and endurance. The sentimentalists and humanitarians abolished the Prize Ring because of its brutality, and the result is that all sense of honour has gone out among the rougher classes, and the record of the police courts have familiarised everybody with the use of the knife in private warfare, a thing almost unknown until the Prize Ring was abolished.

I have very often thought it odd that I have not even a fragmentary memory of the very earliest steps in education. I recall quite easily a time when I could not read, and the recollection of one superb moment is very often with me. That moment came with the reading of a story, entitled The Mandatés Revenge; or the Riccaree War Spear, which came from the pen of Mr Percy B. St John, and may still be found in some far-away number of Chambers's Journal. I have never gone back to that story. I have never had the courage to go back. It would be something like a crime to dissipate the halo of romance and splendour which lives about it, as I know most certainly I should do if I read it over again. I daresay Mr St John was an estimable person in his day; but he could not have written one such story as that my memory so dimly, yet splendidly recalls, without having made himself immortal. In sober truth, I do not believe that any man, whatever, in any time or country, ever wrote a story quite as enthralling and as wonderful as I thought the Mandans Revenge to be. The curious part about this recollection to me is, not that I should have found so intense a joy in what was probably a very commonplace piece of hackwork, but that the faculty of reading at all was, as it were, sprung upon me, and that I remember clearly a feeling of surprise that I had not discovered this wonderful resource before. In effect, I said to myself, “This is the best thing I have yet encountered, and I am never going to do anything else, henceforward.” Fortunately for myself, I have not quite kept that promise, though the printed page has never ceased to be a joy.

In my father's shop we sold not only such serious literature as the population cared to buy, but we dealt, too, in the ephemeral. Mr J. F. Smith wove stories for Cassell's Illustrated Family Journal and the London Journal which would have made the fortune of a modern man; and there was one writer in Reynolds' Miscellany who was most delightfully fertile in horrors. In one chapter he buried a nobleman alive in the family vault, and described his sensations in his coffin so poignantly that for weeks I was afraid to go to sleep lest I should dream about him. My father was an uncommonly well-read man; but he made no attempt to regulate my studies, except that now and then he would suggest to me that I was wasting time in the perusal of rubbish; and I do suppose that, as a boy, I read as much actually worthless stuff as anybody ever did within an equal time. But I do not know whether, after all, it matters very greatly what a child reads, so long as he has full and free access to the best of books.

Amongst my earliest literary treasures was a fat, close-printed volume, the binding of which had been torn away. I do not suppose it had ever been issued in the form of a single volume; but it contained Roderick Random, Gil Blas, The Devil on Two Sticks and Zadig; or, the Book of Fate, and it was my companion through many hundreds of delightful hours. It is both curious and touching to remember the innocence with which one's childish fancy ranged through those pages. I have not turned back to look at my old friend, Asmodeus, for a good many years; but there is one episode in the story of the unroofed city in which an artist is unable to take his mistress to a ball because she has no stockings, and the brilliant idea occurs to him that he should paint a pair upon her legs. There is a special sly mention of the work upon the garter; and the whole business used to seem to me most magnificently comic. There was no more of a suggestion of an impropriety about it than there was about my breakfast bowl of bread and milk. It was just simply, innocently, and gloriously funny; and it has long been my belief that the time at which it is best that a reader should make acquaintance with our rather indelicate old classics is the time of innocence, when no grossness of suggestion has a meaning, though the mind is fully open to the reception of all the reader's own experience teaches him to understand.

I suppose I am going to say a Scythian sort of thing, but I do not remember any very keen or special pleasure in my first encounter with Shakespeare. Perhaps it came when I was too young; but at first the impression made upon me was certainly much inferior to that produced by Mr Percy B. St John, and he was only one of that assembly of wonder-workers of whom the nameless hacks of Reynolds' and Bow Bells were members. When it began to dawn upon me that the spell he exercised was of another kind, I cannot tell. I suppose that the conception of his greatness slowly expanded with the expanding mind; but I know that I had come to young manhood before any special sense of wonder dawned.

After that first discovery of the power to read at all, which came with the Mandans Revenge, the one salient thing in memory is the sudden finding of Carlyle's Heroes and Sartor Resartus. Some literary-minded compositor in my father's employ had placed the book in a rack of type-cases, and had apparently forgotten it. It bore on many pages the stamp of some Young Men's Christian Association in a Northern town, and my literary-minded compositor seems to have looted it. It was my most valued possession for some years. It was, no doubt, a very obvious duty to return it to the institution whose inscription it bore, but I do not think the idea ever presented itself to me.

How shall I speak of the extraordinary emotions which were excited in my mind at a chance opening of the pages at the first chapter of the Sartor? The hurling satire of the opening paragraph—the torch of learning having so illuminated every cranny and dog-hole in the universe that the creation of the world had now become no more mysterious than the making of a dumpling, though concerning this last there were still some to whom the question as to how the apples were got in presented an insoluble problem—this seized me with an amazement of pleasure. I do not mean to say a presumptuous thing at all; but it is a simple fact that from this first beginning of acquaintance with Carlyle, he never once appeared to teach me anything in the way of thought. I know he did so; I know that he profoundly coloured the fountains of my mind for many years; that long and long after the experience I am recording, I thought Carlyle, and wrote Carlyle; and that neither the thinking nor the literary mode could ever have occurred to me without his influence; but in my first reading of his pages, he seemed to be telling me things which were deeply implanted in my soul already. The truth about the matter is, probably, that he dominated me so completely that I did not think at all of domination. But all I know is, that I seemed suddenly to have found an unexpected and hitherto unimagined self. I leapt in transport to encounter a majestic Me; and in this impulse I can honestly aver that there was no tinge of vanity. I should say, rather, that it sprang from the utter humility of the disciple who instantly, absolutely, and unquestionably accepted the master's word. Be these things as they may, the Carlylean gospel came to me, not as a revelation of another's mind, but as an unveiling of a something which seemed to have been for ever my own, though until that great hour I had not dreamed of its possession.

I do not propose to make any immediate flight into sentiment. The thing for which I am trying is a genuine recollection of the way in which the growth of this emotion was marked within myself. Things are very much otherwise to-day; but nearly three-score years ago there was a certain purposed austerity practised by the most dutiful and praiseworthy parents, which froze the natural budding affections of a child. Before I had arrived at the technical age of manhood, my father had become the dearest friend I had in the world, and the friendship lasted till his death; but as a child I feared him. He was by nature as kindly a man as ever lived; but he had been bred in the old rigid Calvinistic creed of Scotland, and though I knew very well, in later years, how his heart had rebelled against him, he was, throughout my childhood and early youth, the embodiment of justice, certainly, so far as he could see it, but always of an apparently unpitying severity. Any judgment of his character based on the system of discipline in which he devoutly believed would have been false in the extreme, for the infliction of pain was actually abhorrent to him. I remember how, on scores of occasions, when I put him to the ordeal of administering a hiding to myself, his face would grow pale, and his hand would tremble.

Between my mother and myself there were none of those intimacies of affection which make life so happy to a child. The whole atmosphere of the house repelled love, and its whole principle seemed to be embodied in the belief that a child should think despitefully of himself, and should repress all natural ebullitions of fondness or of gaiety. I have been trying hard to recall the surname of the boy to whom my heart first flowed out in a real affection, but memory fails me. He was a schoolfellow of mine, and I guess that he may have been of Scottish parentage, because his Christian name was Gavin. I can give no reason, at this time of day—nor ever in my maturer years have I been able to find a reason—why I should have loved that small contemporary as I did. I cannot say that he was conspicuously gifted in any way. He was certainly no Steerforth to my Copperfield, being neither distinguished for good looks, nor for brilliance at his schoolwork, nor for success in games.

It was at this time that there was an ebb in the family fortunes, and I was hastily taken away from a respectable private school in the High Street, and sent, as I have explained, to a big vulgar establishment a mile away, where a crowd of some three hundred lads attended, at a cost to their parents of threepence a week per head. I did not stay there long, but whilst I was kept there, by the strain on the family exchequer, I was very unhappy. It was in the midst of a sore-hearted loneliness that I encountered Gavin, who, to the best of my belief, was the son of a bargee who worked on the Worcester and Birmingham Canal. The impulse which took me towards him I have always regarded as one of the strangest, as it was undoubtedly one of the strongest, I have known. He and I were pretty much alike in age—somewhere between nine and ten we must have been—and we seemed to slide together like two separate rainspots which meet upon a window-pane in wet weather. We used to wander about the stony playground, from which every blade of grass was trampled, except in the remoter corners, and to walk with our arms about each other's shoulders, and to exchange almost daily such trumpery schoolboy treasures as we owned. I never had a child sweetheart, and I never knew anybody with whom I exchanged a caress, or bartered a word of real kindness, until I fell in with this fascinating young ragamuffin. I never spoke about him to a soul, but he filled my thoughts night and day, and I was never happy out of his society. I am guilty of no exaggeration when I say that. The feeling I had towards him was, in its own time, so tender, so yearning, so complete in its absorption of my whole nature, that it stands altogether apart in my experience. And when, after a period of some six months, perhaps, the family fortunes revived a little, and I was restored once more to the society of my own social equals, I was broken-hearted at the thought of losing him.

The master of this rough school had a glimmering of the necessity for technical education, and on occasional afternoons a chosen number of us were drafted off into a big class-room to watch some craftsman working at his trade. One of these men set the whole class on fire with a spirit of emulation. He brought with him a number of medallions, a quantity of plaster-of-paris, a stick or two of common sulphur, and a small brazier, and he proceeded to show us how plaster casts were taken from his medallions. The first part of the process was to oil the surface of the medal, and to bind a strip of brown paper about its edge, so as to form a shallow little well. The next business was to melt enough of the sulphur to secure a cast of the medallion. This part of the process resulted in the production of a most appalling smell, which was not lessened in pungency when the odour of singed brown paper was added to that of melting sulphur. When the cast was cool it also was bound round with brown paper, and a compound of plaster-of-paris and water was poured over it When this had hardened, behold! a snowy reproduction of the original medallion. We all went quite wild about this process, and when the workman filled in the hollowed head in the mould—it was a portrait of John Wesley—with the white preparation, very carefully, by the aid of a small spoon and a camel-hair pencil, we watched with wonder for the next development. The craftsman took a small quantity of chrome-yellow, and, having mixed it carefully with his creamy paste, poured it over the white stuff, so that in a few minutes we saw a snowy bas-relief of the great divine set on a golden-coloured background. From then until I left the school there was an actual fever for the making of plaster medallions, mainly from the heavy, half-effaced Bolton pennies which at that time were in circulation; and among those who were most devoted to this pursuit were my friend Gavin and myself.

We made casts by the dozen and the score, and when it was known definitely that I was leaving the school, he gave to me his chef d'oeuvre, in the shape of a reproduction in two colours of a medal which had been struck to commemorate the opening of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park. There was a solemn understanding between us that I, likewise, should make a cast in two colours, and present it to my chum, and this was to be the symbol and token of an eternity of friendship. I took home the medal; I saved my infrequent pence for the purchase of materials; and one night, all being ready, I set to work to melt my sulphur in a cracked teacup in the kitchen oven. The whole family was assembled in that apartment, for the sitting-room was never used save upon unfrequent gala days, and before long there were sniffs of bewilderment and suspicion at the stench which began to fill the room. I had not thought of this, and I was afraid for the life of me to withdraw the teacup. It was a winter night, and a great fire was blazing on the hearth, so that it was no wonder when the cracked teacup burst asunder, and let out its contents on to the iron floor of the oven. Then there arose an odour of mere and perfect Tophet, and the room was filled with a sulphurous smoke. I confessed myself the author of the mischief by trying to bolt, and I suffered then and there. We were very near being driven entirely out of house and home that night, and I was very shy of reviving the experiment. But my promise lay upon my conscience like a cloud. I had to keep it. To fail in that would have been an unspeakable disloyalty, and very tremulously I made a new occasion when, as I fancied, the coast was clear. It was not so disastrous, in one respect, as the first, but the burning sulphur again betrayed me, and the very natural judgment was that I had been guilty of pure contumacy.

A First View of London—Charles Dickens—The Photograph—On

the Coach to Oxford—The Manuscript of Our Mutual Friend—

An Unpublished Chapter—Dickens as Reader—The British

Museum Reading Room.

I worked in the ramshackle, bankrupt, old printing office at home until I was nearly eighteen years of age, and it was then decided to send me to London to complete my education in the business.

It is like an exhibition of the biograph, in which the scenes depicted go by at such a racing speed that it is difficult for the eye to follow them. There is an instantaneous vision of the old kitchen, seen at some abnormal unaccustomed hour of early morning in the winter-time. Three o'clock on the morning of January 3, 1865. A gas-lit scene of bustle and hurry. Gone. A minute's waiting in a snow-powdered road, carpet-bag in hand, and four-horsed coach ramping along with a frosty gleam of lamps. A jingle of harness, and an adventurous tooting from the guard's horn, as if a charge was being sounded. Gone. Snow Hill, Birmingham, all white and glistening. An extraordinary bustle and clamour. A phantasmagoria of strange faces and figures. Gone. A station all in darkness, but full of echoes and voices. Gone.

A buffet at Oxford, and an instantaneous glimpse of people scalding their throats with an intolerable decoction called coffee extract. The figure of an imperious guard with a waving lamp. The vision of a stampede. Gone. Then an interlude of sleep, during which an orchestra plays dream music, with a roll, roll, roll of wheels as a musical groundwork to the theme. Then Paddington, in a fog—a real London particular, now for the first time seen, felt, tasted, sneezed at, coughed at, wept over. Distracted biographic figures rampant everywhere. Gone. A vision of streets, populous, and full of movement, but half-invisible in a pea-soup haze, through which the gas that takes the place of daylight most ineffectually glimmers. Gone. Then a room, still gas-lit when it should be broad day; a table spread with napery none too clean; a landlady in a dressing-gown and curl-papers; and breakfast. The biograph ceases to whirl by at its original speed, and I can take breath here, and can begin to analyse myself and my own surroundings.

To begin with, this is London; and to continue, I don't think much of it. This is a London egg, and this is London bacon, and this exiguous liquid which “laves the milk-jug with celestial blue” is London milk. All the flavours are strange. The atmosphere is strange. The sight of a lady in curlpapers at 10 a.m. is strange.

Now, in setting down all these things, I begin to take new notice of a fact which has long been familiar to me. It has been expressed by more than one poet, and the reason for it may be found in the works of more than one man of science; but the fact itself is that every one of these cinemato-graphical exercises is associated with a special odour. These special odours have each one so often recurred that they have driven home certain memories in such wise as to make them stick. The fire in the old home kitchen had been “raked” as we used to say in South Staffordshire, overnight, and it gave forth a scent of smouldering ash which, whenever and wherever I have encountered it, has not failed to bring back the scene in which I smelt it first. There is an odour less easy to define, but just as easy to recognise, in the air of the morning street; in the reek of horse and harness going up Snow Hill; in a mingling of wet rot and dry rot in the station; in the acrid, faintly-tinctured coffee smell at Oxford; in the scent of a London fog, or the fragrance of a London egg—any one of which will infallibly take me back to the scene and the time at which it was first perceived.

This, however, is an after-reflection; and here am I in London for the first time as a free man, and, to my own mind, master of my destiny. It really seems at moments as if one might pat it into any form one chose; and it really seems at times as if one were an insect without wings at the bottom of some unfathomable cranny. The fog of my first week in London is, I believe, historic, and its five or six days of tearful blindness and catarrh began to look as if they would reach to the very crack of doom. Those fog-bound days, in which it was impossible for a Midland-bred stranger to stray ten yards from his own door without hopelessly losing himself, are amongst the most despondent and mournful of my life. But, on a sudden, the dawning day revealed to me the other side of the street in an air as crisp, clear, and invigorating as the heart of any youngster, inured to the smoke of the Black Country, could wish for. Then what a joy it was to walk about amongst the bustling crowds, reading stories in the faces of the passers-by, and identifying scores and hundreds of people with the creatures of the great fiction writers. Above all, the people whose life-long friendship we owe to the works of Charles Dickens declared themselves. I lived off the Goswell Road, and that fact alone predisposed me to recognise Mr Pickwick in any spectacled, well-fleshed old gentleman of benevolent aspect. I tumbled across Sam Weller constantly. I was quite certain as to the living personality of one of the Cheeryble twins. When I knew him he was a tailor in Cheapside. It was merely by the accident of time that the shadows I identified with living men had assumed a dress dissimilar to that of the early Victorian era, and I think I may honestly say that for a month or two, at least, my London was mainly peopled by the creations of the author of Pickwick, Little Dorrit, and Dombey.

I never exchanged a word with Dickens in my life; but at this period, by some extraordinary chance, I met him twice. I knew his personal aspect well, for I had heard him read his own works in Birmingham. I was, indeed, a unit in the packed audience which greeted his very first professional appearance as a platform exponent of his own pages. That event took place at the old Broad Street Music Hall in Birmingham, a building which was superseded by the Prince of Wales' Theatre. It was not easy to mistake so characteristic a figure for that of any other man living.

There used to be in Cheapside, at the time of which I write, a window in which the Stereoscopic Company exhibited the latest achievements in photography; and it was my custom, in the dinner hour, to spend some odd minutes in front of this display. I was impressed one day by a new life-sized portrait of Dickens, an enlargement by a process then quite novel. The hair and beard, I remember, had a look of being made out of telegraph wire; but the features were quite natural and unexaggerated. I had taken a good look at the picture, and had, indeed, so firmly fixed it in my mind that I can positively see it now, and could, if I were artist enough, reproduce it; when, having an unoccupied quarter of an hour still on my hands, I turned to stroll towards St Paul's Churchyard, and there, at my elbow, stood the original of the picture. He was looking at it with his head a little thrown back, and somewhat set on one side, and his look was very keen and critical. I gave a start which attracted his attention, and, in the extremity of my surprise, I am afraid that I stared at him rather rudely. I looked back at the photograph, and I looked back at the living face of the great master of tears and laughter, who was then my reigning deity. I can only suppose that my face was full of a foolish wonder and worship, for when I had looked from Dickens to the portrait again, and then back to Dickens, the great man laughed, and gave me a little comic affirmative nod, as much as to say: “It is so, my young friend.” With that he turned briskly, and walked away along Cheapside, leaving me wonder-stricken at what was not, perhaps, so very wonderful an adventure after all.

I rubbed shoulders with the great man again, within a month or two, on a coach which travelled from Thame to Oxford. I climbed that coach on purpose to enjoy the privilege of sitting next to him. He had a travelling companion, who was nursing between his knees quite a little stack of walking-sticks and umbrellas, and I overheard a brief colloquy between him and Dickens.

“Charles,” said the man with the bundle, “why don't you have your name engraved on these?”

“Good God!” said Dickens, in a tone of almost querulous indignation. “Isn't it bad enough already?”

One can well believe that the poor great man found it hard to get about England without being stared at, and pointed out and run after; and we know, from his own pen, that outside his public hours he had a self-respecting passion for privacy.

I came into contact with Dickens in a far different way in the course of that spring. It is a little boast of mine that I was the first person in the world to make acquaintance with Silas Wegg and Nicodemus Boffin and Mr. Venus. My name-father, David Christie, was chief reader at Clowes' printing office in Stamford Street, Blackfriars, and month by month as the proofs of Our Mutual Friend were printed, it was his habit to borrow the Dickens manuscript from Mr Day, the overseer of the establishment, and to take it home with him for his own delectation before it reached the hands of the compositors. On each occasion, until I left London behind me, Christie would wire me always in the same phrase: “Dickens is here,” and I would go down to his lodgings in Duke Street and would read aloud to him the work fresh from the master's hand. It was written on long ruled foolscap on rather darkish blue paper in a pale blue ink, and it needed young eyes to decipher it. There were only a few of such nights, but the enjoyment of them remains as a remembrance. I shall never forget how he laughed over Mr Wegg's earlier lapses into poetry:

“And my elder brother leaned upon his sword, Mr Boffin, And wiped away a tear, Sir.”

Hereabouts befell the first tragedy of my life. In his time Christie had been “reader's” boy at Ballantyne's, in Edinburgh, and in that capacity he had laid hands with a jackdaw assiduity on every scrap of literary interest which he could secure. He had proof sheets corrected by the hands of every notable man of his time. He had been engaged for at least fifty years in making his collection, and he kept it all loosely tumbled together in a big chest, which he used to tell me would become my property on the occasion of his death. Amongst other treasures, I remember the first uncorrected proofs of Marmion and a manuscript play by Sheridan Knowles.

When Christie died I was in Ireland, and on my return to London I discovered that the whole collection had been sold to a butterman as waste-paper at a farthing per pound. There was one literary relic, however, of inestimable value; it consisted of an unpublished chapter in Our Mutual Friend, in which the golden dustman was killed by Silas Wegg. Dickens excised this chapter, had the type broken up, and all the proofs, with the exception of this unique survival, were destroyed. I am not ashamed to confess that when I got back to London and learned the fate which had befallen my old friend's collection, I had a bitter cry over it, which lasted me a good two hours. Christie was a very accomplished man, and was on terms of friendly correspondence with most writers of his time.

I think that first and last I heard Charles Dickens in everything he read in public. What an amazing artist he was in this direction can be realised only by those who heard him. A great actor is always a legend. In these days he may leave something behind him by means of the phonograph and science may yet contrive such an exhibition of facial display and gesture as will enable those who come after us to appreciate his greatness, but in a few years at the utmost, the last man who sat spellbound under the magic of the Dickens personality will have vanished from the face of the earth and nothing but a record will be left.

He depended, as I remember, in a most extraordinary degree upon the temper of his audience. I have heard him read downright flatly and badly to an unresponsive house, and I have seen him vivified and quickened to the most extraordinary display of genius by an audience of the opposite kind. The first occasion on which he ever read for his own profit was in the old Broad Street Music Hall at Birmingham, which for many years now has been known as the Prince of Wales' Theatre. There is so little that is subtle about his work as a writer that it was surprising to find what an illumination he sometimes cast over passages in his work. For example, in his reading of the Christmas Carol, there was one astonishing little episode where the ghost of Jacob Marley first appears to Scrooge. “The dying fire leapt up as if it cried: I know him—Marley's ghost.” The unexpected wild vehemence and weirdness of it were striking in the extreme. He peopled a whole stage sometimes in his best hours, and his Sykes and Fagin, his Claypole and Nancy, were all as real and as individual as if the parts had been sustained by separate performers, and each one a creature of genius. Who that saw it could forget the clod-pated glutton, with the huge imaginary sandwich and the great clasp knife in his hands, bolting the bulging morsel in the midst of the torrent of Fagin's instructions, and complaining “that a man got no time to eat his victuals in that house.” Concerning the scene between Sykes and Nancy, Charles Dickens the younger told me a curious story, at the time when I was writing for him on All the Year Round. They were living at Gad's Hill, and it was the novelist's practice to rehearse in a grove at the bottom of a big field behind the house. Nobody knew of this practice until one day the younger Charles heard sounds of violent threatening in a gruff, manly voice, and shrill calls of appeal rising in answer, and thinking that murder was being done, he unfastened a great household mastiff and raced along the field to find the tragedy of Sykes and Nancy in full swing.

I am afraid that like most newly emancipated lads I used my freedom in many foolish ways; but most of them were harmless, and some of my truancies from work were even useful to me. Do what I would, I could not find the strength of will to go and pick up types in a frowsy printing office when the picture-gazing fit was on me; and many a time I shirked my duties for the vicious pleasure of a long day's intercourse with Turner in the National Gallery, or for a lingering stroll amongst the marbles at the Museum. One never-to-be forgotten day, my old name-father, David Christie, lent me a reader's ticket, and I found myself for the first time in that central citadel of books, the Museum Library. I went in gaily, with a heart full of ardour; but as I looked about me my spirits fell to zero. I knew that what I saw in the storied shelves which run round the walls, under the big glass dome, made but a little part of the vast collection stored away below and around them; and the impossibility of making even a surface acquaintance with that which lay in sight came strongly home to me.

I Enlist—St George's Barracks—The Recruits—From Bristol

to Cork—Sergeants—The Bounty and the Free Kit—Life in the

Army—My Discharge—A Sweet Revenge.

I am not very good at dates, but there are a few which I can recall with unfailing accuracy. On 25th May 1865, whilst I was staring at one of the sunlit fountains in Trafalgar Square, and listening to the bells of Westminster as they chimed the hour of four, a venerable old spider in a blue uniform with brass buttons, and a triple chevron of gold lace upon his arm, accosted me without introduction and asked me what I thought about life in the Army. Until then, so far as I can remember, I had never thought about the Army at all. My eighteenth birthday was just one month and twelve days behind me; I had one and sevenpence in the wide world; I was smoking the last cigar of an expensive box, in the purchase of which I had not been justified by the means at my disposal; and I was in mortal terror of my landlady. It had been discovered at the printing office of Messrs Unwin Bros., at which I had been engaged as an “improver,” that I had no regular indentures, and I had been thrown upon a merely casual employment amongst as undesirable and as hopeless a set as could have been found at that time in my trade in London. Apart from all these considerations, the world had come to an end because a certain young lady, who, to the best of my belief, is still alive, and a prosperous and happy grandmother, had unequivocally declined to marry me. The blue-clad spider had no need to spread the web of temptation. I resolved in an instant, and he and I adjourned to a backyard somewhere in the neighbourhood, for which I have long since sought in vain. I rather fancy that the wide spaces of Northumberland Avenue have displaced it; but, in any case, the route we took led us towards the river, the smell of which comes back to my nostrils at the moment at which I write, with a queer mingled suggestion of sludge, and sunlight, and sewage.

In that backyard I was put to a sort of mild ordeal by question. Was I married? Was I an apprentice? Had I ever been refused for either of Her Majesty's Services on account of any physical defect? Was I aware of any such defect as would debar me from service? Had I ever been convicted of any crime or misdemeanour? To all these queries I was able to answer in the negative; but, whilst the solemn interrogation was going on, a young man with his head full of flour, and his hands and arms covered with little spirals and pills of dough, appeared at the top of a neighbouring wall. “Don't you believe a word of what that cove is telling you,” he counselled, and so disappeared, in obedience to a rather urgent gesture from the blue old spider. I took the shilling, and the spider hinting that a dry bargain was likely to prove a bad bargain, I expended it in two glasses of sherry at some neighbouring “wine shade,” to which he conducted me—the sort of institution which the Bodega Company has very advantageously superseded. It was a dirty place, with rotting sawdust on the floor, and little hollows beaten into the pewter counter, in which were small lakes of stale wasted liquors of various kinds; and the smell of it, also, is in my nostrils as I write. I was instructed to present myself at St George's Barracks, Westminster, at eleven o'clock on the following morning, and was told that if I failed in that respect I should become in the eye of the law a rogue and vagabond, and should be liable to summary indictment. I was dressed in my best, because I was going out to tea that evening with an old family friend in the Haymarket, a picture-restorer, whose shop and studio were next door to the old Hay-market Theatre. My host told me that at the very last appearance of Madame Goldschmit (Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale), he had sat at his open window, and had heard her sing as clearly as if he had been one of a paying audience who spent anything from a hundred pounds to a guinea to enjoy that privilege; and I can well believe him, because I heard easily the quaint chuckle of old Buckstone's voice through the open windows of the studio. I am not sure at this distance of time, but I think he was then playing the part of Asa Trenchard, with Sothern, in Dundreary Married and Done For.

I got home that night without any interview with the dreaded landlady, and made a bolt very early in the morning, leaving books, pictures, and wardrobe to solve my bill. That night I slept in the great London depot barracks. I know perhaps as well as anybody how Tommy Atkins has improved in character and conduct since those days, but I can aver that never before or since have I encountered a crew so wholly shameless and abominable as I found that night at St George's, Westminster. It is not a pretty thing to be the only decently bred and sober man amongst a howling crowd of yokel drunkards, whose every phrase is built on a foundation of hitherto unconceived obscenities. The night was enough; and, with three half-crowns in my pocket, paid to me as subsistence money for the three days ensuing between that date and the date of my departure, I betook myself to a common lodging-house, and lived in comparative decency. Some score of us, or perhaps a dozen, went up together for surgical examination, and were made to strip stark naked in each other's presence. I had never objected to this amongst my own kind and kindred, when one exposed one's nudity by the side of the clean brook or yellow canal in which we used to bathe in boyhood; but amongst this crew it was hard, and even terrible. We had all been bathed, perforce, before the medical examination began; but a mere tubbing does not cleanse the mind or tongue, and I loathed alike the ceremony itself and the men amongst whom I was forced to submit to it.

We marched through the London streets to Paddington, and I, having ingratiated the sergeant who escorted us by a drink or two, was permitted to walk by his side, whilst the ragged, semi-drunken contingent went rolling and cursing ahead. We embarked for Bristol, and there spent a night at the Gloucester Barracks, where a cross-grained old sergeant, who had vainly tempted me to sell my clothes, and to exchange them for a suit of rags, compelled me to carry endless loads of coals up endless flights of stairs. He began his intercourse with me by addressing me in Greek, of which language I knew nothing; and he followed it with a dog-French which, ignorant as I was, I was able to detect. In the morning we were taken aboard the paddleship Appollo, bound for Cork, and I am in debt to the chief officer of that craft for the advice he gave me. “It's the ambition of these beggars,” he said, intending thereby the convoying sergeants, “to land any decent chap at the barracks looking like a scarecrow. There's a good half of them no better than dealers in old clothes. You take my advice: go to your regiment looking like a gentleman. When you get your regimentals, you can sell your civilian clothes for twice as much as these sharks would give you.” I followed the advice thus given, and I had reason to be grateful to the adviser.

The drunken, howling, cursing, foolish contingent with which I started were scattered far and wide from the Catshill Barracks at Cork, and I travelled thence under the care of a sedate old sergeant to Cahir, in Tipperary. The sergeant was talkative and friendly, but I paid little heed to him, for it was here, if I mistake not, that the joy of landscape first entered into my soul. I have an impression only of an abounding green and blue in general, but one or two stopping-points are as clear in my mind as if I had seen them yesterday. Amongst them is some old grey stone bridge near Limerick, where the train slowed down and my Irish companion—Limerick born and bred, and rejoicing to show his own country to a landscape lover—declared that he had travelled almost dry-shod over the backs of the salmon which once thronged along that river. I had my doubts at the moment as to the literal truth of this statement, and I am not quite sure that I do not nurse them still. Anyhow, the country struck me with that deceptive sense of fruitfulness which besets every Englishman on his first travels into the fertile districts of Ireland; and partly, perhaps, because I was half a Celt to begin with, the “wearing of the green” became then and there a symbol in my mind.

Finally, at the end of a fairly long day's run—for the cheaper kind of train travelled slowly in those days—the convoying sergeant and I were dumped down at the station at Cahir, which had not yet become celebrated in that gorgeous fiction which was woven about it in later years by the claimant to the Tichborne estates. Night was falling as we tramped through the village, and on the road beyond we came across the ghostly shell of an old castle, standing, I think, in the Byrne demesne, which was packed full of jackdaws, who had caught one or two human phrases from some half-Christianised member of their fellowship, and who woke the echoes in answer to our footsteps with a hundred semi-human cries. They had only a phrase or two amongst them, but they gave one clearly the impression that they represented a Babylonian crowd intent on insurrection.

I was passed from one sergeant to another in the course of my transfer from St George's Barracks to Clare in the county Tipperary, and there was not one of them who did not try to induce me to change a reputable garb for a set of garments that would have done justice to a scare-crow.

The contingent with which I was shipped from Bristol to Cork composed as ribald and foul-mouthed a crew as I remember to have seen, and long before I assumed Her Majesty's uniform, I was sickened of the enterprise on which I had embarked. I think I am justified in saying that I was instrumental in bringing about one great and much needed reform. In those days, the recruit on enlistment was supposed to receive a bounty and a free kit; as the thing was worked out by the regimental quartermaster, he never saw one or the other. He had served out to him on his arrival at his depot a set of obsolete garments which he was forbidden to wear and was compelled to return to stores, when a new outfit at his own cost had been supplied to him. My gorge rose at this bare-faced iniquity, and as a protest against it, I attired myself on my first Sunday in barracks in the clothes which had been fraudulently assigned to me, and joined the regiment on church parade. I suppose no soldier had been so attired since Waterloo, and my appearance was the signal for a roar of laughter in which men and officers alike joined, and which was not extinguished until I had been ignominiously hustled back to quarters. In the Fourth Royal Irish Dragoon Guards at least, I know myself to have been the last man whom the wicked system attempted to pillage in that fashion. As a matter of course, I was marked from that moment.

People who have a practical knowledge of modern Army life tell me that things have changed altogether for the better since those far bygone days of 1865; and I am disposed to believe that no such shameless swindles as were then perpetrated could possibly continue for a week under existing conditions. A Press which makes us familiar with all sorts of grievances, and an inquiring Parliamentarian or two, would provide a short shrift and a long rope for the perpetrator of any such bare-faced robbery as I suffered under when I first joined the Fourth Royal Irish Dragoon Guards. The motive of my enlistment had no remotest connection with the bounty offered. I joined the Army simply out of that green-sickness of the mind from which so many young men suffer, and some nebulous notions of heroism in falling against a savage foe in some place not geographically defined. But in the printed terms of the agreement which I signed it was promised that I should receive a three pound bounty and a free kit. As a matter of fact, I received neither one nor the other. I was served out, as I have stated, with an absolutely obsolete uniform, which I was forbidden to wear, and my bounty was impounded to pay for regulation clothing.

This initial struggle made me from the first a personage of mark in the regiment; for when I was summoned to my first parade, I had deliberately donned the clothes which had been dealt out to me from the quartermaster's stores, and presented myself to public view in a uniform which had probably been seen on no parade ground in England since Her late Majesty's accession to the throne. It was a sufficiently solemn proceeding on my own part, for I was warned that I was being guilty of a military misdemeanour of the gravest sort But if the thing was serious to me, it was a matter of rejoicing comedy—or even, if you like, of screaming farce—to the troops who were paraded for church that Sunday morning. Men fairly shrieked with laughter at the sight of the old Kilmarnock cap, the ridiculous tailed jacket, and the rough shoddy trousers bagging at the seat. The officers made an attempt at decorum which was not too successful; and I was hustled from the ground, and escorted to the guard-room, for the high crime and misdemeanour of presuming to appear in the clothes which had officially been served out to me. I appeared at the orderly-room next morning, and underwent a severe wigging from the officer who was in temporary command of the regiment; but the incident was mercifully allowed to close with a mere reprimand. It did a little good, perhaps, for I never knew any other recruit to be served out with an utterly obsolete and useless kit so long as I remained with the regiment; but, until the hour at which my discharge was purchased, I was taught that it was not conducive to personal comfort to rebel against any form of tyranny and extortion which might be condoned by tradition in the Army.