Harry Collingwood

"A Pirate of the Caribbees"

Chapter One.

A frigate fight in mid-Atlantic.

“Eight bells, there, sleepers; d’ye hear the news?—Rouse and bitt, my hearties! Show a leg! Eight bells, Courtenay! and Keene says he will be much obliged if you will relieve him as soon as possible!”

These words, delivered in a tone of voice that was a curious alternation of a high treble with a preternaturally deep bass—due to the fact that the speaker’s voice was “breaking”—and accompanied by the reckless banging of a tin pannikin upon the deal table that adorned the midshipmen’s berth of H.M. frigate Althea, instantly awoke me to the disagreeable consciousness that my watch below had come to an end, especially as the concluding portion of the harangue was addressed to me personally, and accompanied by a most uncompromising thump upon the side of my hammock. So I surlily growled an answer—

“All right, young ’un; there’s no occasion to make all that hideous row! Just see if you can make yourself useful by finding Black Peter, will you, and telling him to brew some coffee.”

The lad was turning away to do my bidding when a pattering of naked feet became audible as their owner approached, while a husky voice ejaculated—

“Who’s dat axin’ for Brack Petah? Was it you, Mistah Courtenay?” And at the same instant the shining, good-natured, grinning visage of a gigantic negro appeared in the narrow doorway, through which the fellow instantly passed into the berth, bearing a big pot of steaming hot coffee.

“Ay, you black demon, I it was,” answered I. “Is that coffee you have there? Then find my cup and fill it, there’s a good fellow, and I’ll owe you a glass of grog.”

“Hi, yi!” answered the black, his eyes sparkling and his teeth gleaming hilariously, “who you call ‘brack demon,’ eh, sah? Who eber hear of brack demon turnin’ out at four o’clock in de mornin’ to make coffee for young gentermen, eh? And about de grog, Mistah Courtenay; how many glasses do dis one make dat you now owe me, eh, sah? Ansah me dat, sah. You don’ keep no account, I expec’s, sah, but I do. Dis one makes seben, Mistah Courtenay, and I’d be much obleege, sah, if you’d pay some of dem off. It am all bery well to say you’ll owe ’em to me, sah, but what’s de use ob dat if you don’ nebber pay me, eh?”

“Pay you, you rascal?” shouted I, as I sprang to the deck and began hastily to scramble into my clothes, “do you mean to say that you have the impudence to actually expect to be paid? Is it not honour and reward enough that a gentleman condescends to become indebted to you? Pay, indeed! why, what is the world coming to, I wonder?”

“Bravo, Courtenay, well spoken!” shouted young Lindsay, the lad who had so ruthlessly interrupted my slumbers, “how well you express yourself; you ought to be in Parliament, man! Give it him again; bring him to his bearings. The impudence of the fellow is getting to be past endurance! Now then, you black swab, where’s the sugar? Do you suppose we can drink that stuff without sugar?”

After a search of some duration the sugar was eventually found in a locker, in loving contiguity to an open box of blacking, some boot brushes, a box of candles, a few fragments of brown windsor,—one of which had somehow found its way into the bowl,—and a few other fragrant trifles. In my haste to get on deck, and betrayed by the feeble light of the purser’s dip, which just sufficed to render the darkness visible, I managed to convey this stray morsel of soap into my coffee along with the sugar wherewith I intended to sweeten it, and only discovered what I had done barely in time to avoid gulping down the soap along with the scalding liquid into which I had plunged it. A midshipman, however, soon loses all sense of squeamishness, so I contented myself with muttering a sea blessing upon the head of the unknown individual who had deposited this “matter in the wrong place,” and dashed up the hatchway to relieve the impatient Keene.

I shivered and instinctively buttoned my jacket closely about me as I stepped out on deck, for, mild and bland as the temperature actually was, it felt raw and chill after the close, stifling atmosphere of the midshipman’s berth. It was very dark, for it was only just past the date of the new moon, and the thin silver sickle—which was all that the coy orb then showed of herself—had set some hours before; moreover, there was a thin veil of mist or sea fog hanging upon the surface of the water, through which only a few of the brighter stars could be faintly distinguished near the zenith. There was no wind—it had fallen calm the night before about sunset, and we were in the Horse latitudes—and the frigate was rolling uneasily upon a short, steep swell that had come creeping up out from the north-east during the middle watch, the precursor, as we hoped, of the north-east trades—for we were in the very heart of the North Atlantic, and bound to the West Indies. I duly received the anathemas of my shipmate Keene at my tardy appearance on deck, hurled a properly spirited retort after him down the hatchway, and then made my way up the poop ladder to tramp out my watch on the lee side of the deck—if there can be such a thing as a lee side when there is no wind.

It was dreary work, this tramping fore and aft, fore and aft, with nothing whatever to engage the attention, and nothing to do. I therefore eagerly watched for, and hailed with delight, the first faint pallid brightening of the eastern sky that heralded the dawn; for with daylight there would at least be the ship’s toilet to make—the decks to holystone and scrub, brasswork and guns to clean and polish, the paintwork to wash, sheets and braces to flemish-coil, and mayhap something to see, as well as the possibility that with the rising of the sun we might get a small slant of wind to push us a few miles nearer to the region where the trade wind was merrily blowing.

The dawn came slowly—or perhaps it merely seemed to my impatience to do so—and with daylight the mist that had hung about the ship all night thickened into a genuine, unmistakable fog, so thick that when standing by the break of the poop it was impossible to see as far as the jib-boom end.

The fog made Mr Hennesey, our second lieutenant and the officer of the watch, uneasy,—as well it might, for we were in the early spring of the year 1805, and Great Britain was at war with France, Spain, and Holland, at that time the three most formidable naval powers in the world, next to ourselves, and the chances were that every second ship we might meet would be an enemy,—and at length, just as seven bells were being struck, he turned to me and said—

“Mr Courtenay, you have good eyes; just jump up on to the main-royal yard, will you, and take a look round. This fog packs close, but I do not believe it reaches as high as our mastheads, and I feel curious to know whether anything has drifted within sight of us during the night.”

I touched my hat, and forthwith made my way into the main rigging, glad of even a journey aloft to break the dismal monotony of the blind, grey, stirless morning, and in due time swung myself up on to the slender yard, the sail of which had been clewed up but not furled. But, alas! the worthy second luff was mistaken for once in his life; it was every whit as thick up there as it was down on deck, and not a thing could I see but the fore and mizzenmasts, with their intricacies of standing and running rigging, their tapering yards, and their broad spaces of wet and drooping canvas, hanging limp and looming spectrally through the ghostly mist-wreaths. I was about to hail the deck and report the failure of my experimental journey, but was checked in the very act by feeling something like a faint stir in the damp, heavy air about me; another moment and a dim yellow smudge became visible on the port beam, which I presently recognised as the newly risen sun struggling to pierce with his beams the ponderous masses of white vapour that were now slowly working as though stirred by some subtle agency. By imperceptible degrees the pallid vision of the sun brightened and strengthened, and presently I became conscious of a faint but distinct movement of the air from off the port quarter, to which the cloths of the sail against which my feet dangled responded with a gentle rustling movement.

“On deck, there!” I shouted, “it is still as thick as a hedge up here, sir, but it seems inclined to clear, and I believe we are going to have a breeze out from the north-east presently.”

“So much the better,” answered the second luff, ignoring the first half of my communication; “stay where you are a little longer, if you please, Mr Courtenay.”

“Ay, ay, sir!” answered I, settling myself more comfortably upon the yard. And while the words were still upon my lips the stagnant air about me once more stirred, the great spaces of canvas beneath me swelled sluggishly out with a small pattering of reef-points from the three topsails, and a gentle creak of truss and parrel, as the strain of the filling canvas came upon the yards; and I saw the brightening disc of the sun begin to sweep round until it bore broad upon our larboard quarter. Then some sharp words of command from the poop, in Mr Hennesey’s well-known tones,—dulcet as those of a bullfrog with a bad cold,—came floating up to me, followed by the shrill notes of the boatswain’s pipe and his hoarse bellow of, “Hands make sail!” A few minutes of orderly confusion down on deck and on the yards below me now ensued, and when it ceased the Althea was running square away before the languid but slowly strengthening breeze, with studding-sails set on both sides.

Meanwhile the log was gradually clearing, for it was now possible to see to a distance of fully three lengths of the ship on either hand, before the curling and sweeping wreaths of vapour shut out the tiny dancing ripples that seemed to be merrily racing the ship to port and starboard. Occasionally a break or clear space in the fog-bank swept down upon and overtook us, when it would be possible to see for a distance of a quarter of a mile for a few seconds; then it would thicken again and be as blinding as ever. But every break that came was wider than the one that preceded it, showing that the windward edge of the bank was rapidly drawing down after us; and as these breaks occurred indifferently on either side of, or sometimes on both sides at once, with now and then a clear space right astern to give a spice of variety to the proceedings, my eyes, as may be guessed, were kept pretty busy.

At length an opening, very considerably wider than any that had thus far reached us, came sweeping down upon our starboard quarter, and as I peered into it, endeavouring to pierce the veil of fog that formed its farther extremity, I suddenly became aware of a vague shape indistinctly perceptible through the intervening wreaths of mist that were now sweeping rapidly along before the steadily freshening breeze. I saw it but during the wink of an eyelid, when it was shut in again, but I knew at once what it was; it could be but one thing—a ship, and I forthwith hailed—

“On deck, there! there’s a strange sail about a mile distant, sir, broad on our starboard quarter!”

“Thank you, Mr Courtenay,” promptly responded the “second.”

“What do you make her out to be?”

“It is impossible at present to say anything definite about her, sir,” I answered. “I saw her but for a second, and then only very indistinctly, but she loomed up through the fog like a craft of about our own size.”

“Very well, sir,” answered Hennesey; “stay where you are, and keep a sharp lookout for her next appearance.”

Once more I returned the stereotyped, “Ay, ay, sir!” as I sent my glances searching round the ship for further openings. The next that overtook us swept down upon our port quarter; it was fully a mile and a half wide, and when it bore about four points abaft the beam another shape slid into it, not vague and shadowy this time, as the other shape had been, but clearly distinct—a frigate, unmistakably, under a similar spread of canvas to our own, and as nearly as possible our own size. So close indeed was the resemblance that for a second or two I was disposed to fancy that by some strange trick of light and reflection the fog was treating me to a picture of the old Althea herself, but a more steadfast scrutiny soon dispelled the illusion. There were certain unmistakable points of difference between this second apparition and ourselves, some of which were so strongly characteristic that I at once set her down as a French frigate.

The plot was thickening, and it was not wholly without a certain feeling of exhilaration that I again hailed the deck—

“A frigate broad on our port quarter, sir, with a very Frenchified look about her!”

“Thank you again, Mr Courtenay,” answered Hennesey, with an unmistakable ring of delight in his jovial Irish accent, which, by the way, had a trick of growing more pronounced under the influence of excitement. “Ah, true for you, there she is,” he continued, “I have her! Mr Hudson, have the kindness to jump below and fetch me my glass, will ye, and look alive, you shmall anatomy!”

A gentle ripple of subdued laughter from the forecastle at this sally of our genial “second” floated up to me from the forecastle, a glimpse of which I could just catch under the foot of the fore-topsail, and I could see that the men were all alive down there with pleasurable excitement at the prospect of a possible fight. Young Hudson—a smart little fellow, barely fourteen years old, and the most juvenile member of our mess—was soon on deck again with the second lieutenant’s telescope; but by this time the fog had shut the stranger in again, so, for the moment, friend Hennesey’s curiosity had to remain unsatisfied. Not for long, however; the presumably French frigate had not been lost sight of more than two or three minutes when I caught a second glimpse of the other craft—the one first sighted—on our starboard quarter.

“There is the other fellow, sir!” I shouted. “You can see her distinctly now. And she too is a frigate, and French, unless I am greatly mistaken.”

“By the powers, Mr Courtenay, I hope you may be right,” answered Hennesey. “Ay, there she is,” he continued, “as plain as mud in a wineglass! And if she isn’t French her looks belie her. Mr Hudson, you spalpeen, slip down below and tell the captain that there are a brace of suspicious-looking craft within a mile of us. And ye may call upon Misther Dawson and impart the same pleasant information to him.” Then, turning his beaming phiz up to me, he continued—

“Mr Courtenay, it’s on the stroke of eight bells, but all the same you’d better stay where you are for the present, until the fog clears, since you know exactly the bearings of those two craft. And I’ll thank ye to keep your weather eye liftin’, young gentleman; there may be a whole fleet of Frenchmen within gun-shot of us, for all that we can tell.”

“Ay, ay, sir!” I cheerfully answered, my curiosity having by this time got the better of my keen appetite for breakfast; moreover, having been the discoverer of the two sail already sighted, I was anxious to add to the prestige thus gained by being the first to sight any other craft that might happen to be in our neighbourhood.

My stay aloft, however, was not destined to be a long one, for the fog was now clearing fast, and within ten minutes it had all driven away to leeward of us, revealing the fact that there were but the two sail already discovered in sight—unless there might happen to be others so far ahead as to be still hidden in the fog-bank to leeward. But before I left the royal yard I had succeeded in satisfying myself, by means of my glass—which had been sent up to me bent on to the signal halliards—that the two strangers were frigates, and almost certainly French. They were exchanging signals at a great rate, but we could make nothing of their flags, which at least proved that they were not British. To make assurance doubly sure, however, we had hoisted our private signal, to which neither ship had been able to reply. There was no doubt that they were enemies; and this fact having been satisfactorily established, I was permitted to descend and snatch a hasty breakfast.

And a hasty one it was, for I had scarcely been below five minutes when we were piped to clear for action, and I was obliged to hurry on deck again. But a hungry midshipman can achieve a good deal in the eating line in five minutes, and in that brief interval I contrived to stow away enough food to take the keen edge off my appetite, promising myself that I would make up my leeway at dinner-time—provided that I was still alive when the hour for that meal came round. This last thought sobered me down somewhat, and to a certain extent subdued my hilarious spirits; but they rose again as, upon gaining the deck, I looked round and saw the cheerful yet resolute faces of the captain and officers, and noted the gaiety with which the men went about their duty.

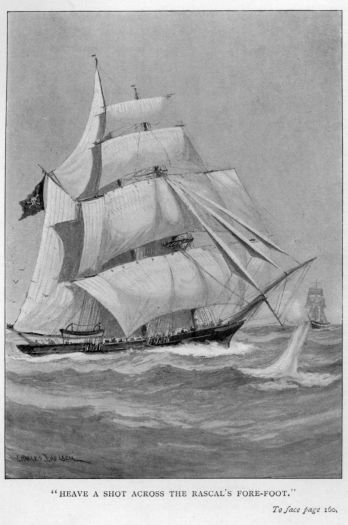

The strangers had by this time shown their bunting,—the tricolour,—so there was no further question of their nationality or of the fact that we were booked for a sharp fight, for they had the heels of us and were overhauling us in grand style; we could not therefore have escaped, had we been ever so anxious to do so. And, had we made the attempt, we should certainly have been quite justified, for it had now been ascertained that they were both forty-gun ships, while we mounted only thirty-six pieces on our gun deck. Escape, however, was apparently the very last thought likely to occur to Captain Harrison; for although he kept the studding-sails abroad while the ship was being prepared for action, no sooner had the first lieutenant reported everything ready than the order was given to shorten sail; and a pretty sight it was to see how smartly and with what beautifully perfect precision everything was done at once, the studding-sails all collapsing and coming in together at exactly the same moment that the three royals were clewed up and the flight of staysails on the main and mizzen masts hauled down.

“Very prettily done, Mr Dawson,” said the skipper approvingly. “Our friends yonder will see that they have seamen to deal with, at all events, even though we cannot sport such a clean pair of heels as their own.”

The two Frenchmen were by this time within less than half a mile of us, converging upon us in such a manner as to range up alongside the Althea within the toss of a biscuit on either hand, but neither of them manifested the slightest disposition to follow our example by shortening sail. Perhaps they believed that, were they to do so, we should at once make sail again and endeavour to escape, whereas by holding on to everything until they drew up alongside us, we should fall an easy prey to their superior strength, if indeed we did not surrender at discretion.

And, truly, the two ships formed a noble and a graceful picture as they came sweeping rapidly down upon us with every stitch of canvas set that they could possibly spread, their white sails towering spire-like into the deep, tender blue of the cloudless heavens, with the delicate purple shadows chasing each other athwart the rounded bosoms of them as the hulls that up-bore them swung pendulum-like, with a little curl of snow under their bows, over the low hillocks of swell that chased them, sparkling in the brilliant sunlight like a heaving floor of sapphire strewed broadcast with diamonds.

They stood on, silent as the grave, until the craft on our larboard quarter—which was leading by about a couple of lengths—had reached to within a short quarter of a mile of us, when, as we all stood watching them intently, a jet of flame, followed by a heavy burst of white smoke, leapt out from her starboard bow port, and the  next instant the shot went humming close past us, to dash up the water in a fountain-like jet a quarter of a mile ahead of us.

next instant the shot went humming close past us, to dash up the water in a fountain-like jet a quarter of a mile ahead of us.

“That, I take it, is a polite request to us to heave-to and haul down our colours,” remarked Captain Harrison to the first lieutenant, with a smile. “Well, we may as well return the compliment, Mr Dawson. Try a shot at each of them with the stern-chasers. If we could only manage to knock away an important spar on board either of them it might so cripple her as to cause her to drop astern, leaving us to deal with the other one and settle her business out of hand. Yes, aim at their spars, Mr Dawson. It would perhaps have been better had we opened fire directly they were within range, but I was anxious not to make a mistake. Now that they have fired upon us, however, we need hesitate no longer.”

The order was accordingly given to open fire with our stern-chasers, and in less than a minute the two guns spoke out simultaneously, jarring the old hooker to her keel. We were unable for a moment to see the effect of the shots, for the smoke blew in over our taffrail, completely hiding our two pursuers for a few seconds; but when it cleared away a cheer broke from the men who were manning the after guns, for it was seen that the flying-jib stay of our antagonist on the port quarter was cut and the sail towing from the jib-boom end, a neat hole in her port foretopmast studding-sail showing where the shot had passed. The other gun had been less successful, the shot having passed through the head of the second frigate’s foresail about four feet below the yard and half-way between the slings and the starboard yardarm, without inflicting any further perceptible damage.

“Very well-meant! Let them try again,” exclaimed the skipper approvingly. And as the words issued from his lips we saw the two pursuing frigates yaw broadly outward, as if by common consent, and the next instant they both let drive a whole broadside at us. I waited breathlessly while one might have counted “one—two,” and then the sound of an ominous crashing aloft told me that we were wounded somewhere among our spars. A block, followed by a shower of splinters, came hurtling down on deck, breaking the arm of a man at the aftermost quarter-deck gun on the port side, and then a louder crash aloft caused me to look up just in time to see our mizzen-topmast go sweeping forward into the hollow of the maintopsail, which it split from head to foot, the mizzen-topgallant mast snapping short off at the cap as it swooped down upon the maintopsail yard. Two topmen were swept out of the maintop by the wreckage in its descent, and terribly—one of them fatally—injured, and there were a few minor damages, which, however, were quickly repaired. Then, as some hands sprang aloft to clear away the wreck, our stern-chasers spoke out again, the one close after the other, and two new holes in the enemy’s canvas testified to the excellent aim of our gunners; but, unfortunately, that was the extent of the damage, both shots having passed very close to, but just missed, important spars.

The French displayed very creditable smartness in getting inboard the flying-jib that we had cut away for them, and by the time that this was accomplished they had drawn up so close to us that by bearing away a point or two to port and starboard respectively, both craft were enabled to bring their whole broadsides to bear upon us, which they immediately did, taking in their studding-sails, and otherwise reducing their canvas at the same time, until we were all three under exactly the same amount of sail—excepting, of course, that we had lost our mizzen-topsail with all above it, while theirs still stood intact. As for us, our guns were all trained as far aft as the port-holes would permit, and as our antagonists ranged up on either quarter, within pistol-shot, each gun was fired point-blank as it was brought to bear. And now the fight began in real, grim downright earnest, the crew of each gun loading and firing as rapidly as possible, while the French poured in their broadsides with a coolness and precision that extorted our warmest admiration, despite the disagreeable fact that they were playing havoc with us fore and aft, one of our guns having been dismounted within three minutes of the arrival of the enemy alongside us, while the tale of killed and wounded was growing heavier with every broadside that we received. But if we were suffering severely we were paying our punishment back with interest, as we could see by glancing at the hulls of our antagonists, the sides of which were torn and splintered and pierced all along the broad white streak that marked the line of ports,—some of which were knocked two into one,—while their yellow sides were here and there broadly streaked with crimson as the blood drained away through their scuppers. It is true they were fighting us two to one, but, after all, their advantage was more apparent than real, for, running level with us as they were, they could only fight one of their batteries, while we were fighting both ours, and our guns—every one of them double-shotted—were being better and more rapidly served than theirs.

I will not attempt to describe the fight in detail, for indeed any such attempt could only result in failure. And as a matter of fact there was very little to describe. We simply ran dead away to leeward, the three of us, fighting almost yardarm to yardarm, and exchanging broadsides as rapidly as the guns could be loaded and run out. After the first ten minutes of the fight there was little or nothing to be seen, for the wind was fast dropping again, and the three ships were wrapped in a dense white pall of smoke that effectually concealed everything that was going on at a greater distance than some fifty feet from the observer. The most impressive characteristic of the struggle was noise—the incessant crash of the guns, the discharge of which set up a continuous tremor of the ship throughout the entire fabric of her; the rending and splintering of timber as the enemy’s shot tore its way through the frigate’s sides; the shrieks and groans of the wounded and dying, cut into at frequent intervals by some sharp order from the captain or the first lieutenant; the curt commands of the captains of the guns: “Stop the vent! run in! sponge! load! run out!” and so on; the creak of the tackle blocks, the rumble of the gun carriages, the clatter of handspikes, the dull thud of the rammers driving home the shot, the rattling volleys of musketry from the marines on the poop, the occasional rending crash of a falling spar, and the terrific babble of the Frenchmen on either side of us, sounding high and clear in the occasional brief intervals when all the guns happened to be silent together for a moment,—I can only compare it all to the horrible confusion raging through the disordered imagination of one in the clutches of a fiercely burning fever. Our people fought grimly and in silence, save for an occasional cheer at some unusually successful shot; but the Frenchmen jabbered away incessantly, sometimes reviling us and shaking their fists at us through their open ports, and more often squabbling among themselves.

At length, when the fight had lasted about half an hour, the wind dropped to a dead calm, and the Frenchman on our starboard side, who had forged somewhat ahead of us, made an effort to lay himself athwart our bows before he lost way altogether. But we were too quick for him, for his mainmast was towing alongside and stopped his way; so we did with him what he tried to do to us, driving square athwart his bows as his bowsprit came thrusting in between our fore and main masts, when we lost not a moment in lashing the spar to our main rigging. But, after all, it resolved itself into tit for tat, for the other fellow put his helm hard aport and just managed to drive square athwart our stern, where he raked us most unmercifully for fully five minutes, until he drove clear, bringing down all three of our masts before he left us. Of course we could only retaliate upon him with our stern-chasers, which we played upon him with considerable effect; but what we lacked in the way of adequate retort to him we amply made up for to his consort, raking her time after time with such good-will that in a few minutes her bows were battered into a mere mass of torn and splintered timber. Somebody on board her cried out that they had struck, but as her marines kept up their fire upon us from the poop, while her main-deck guns continued to blaze away whenever she swung sufficiently for any of them to bear, no notice was taken of this intimation; and presently our skipper gave the order to cut her adrift, so that her people might have no chance to board—a proceeding that would have proved exceedingly awkward for us in our then weakened condition.

But it presently became evident that they had no thought of boarding us; on the contrary, their chief anxiety was clearly to escape from the warm berth that they had thrust themselves into; for a few minutes later, the fire on both sides having slackened somewhat, we observed that both craft had their boats in the water and were doing their best to tow off from us, and almost immediately afterwards the French ceased firing altogether. I believe our skipper—fire-eater though he was—felt unfeignedly thankful at this cessation of hostilities, for he immediately followed suit, giving the order for the men to leave the guns and proceed to repair damages. This was no light task, for not only were we completely dismasted, but the hull of the ship was terribly knocked about, the carpenter reporting five feet of water in the hold and twenty-seven shot-holes between wind and water, apart from our other damages, which were sufficiently serious. Moreover, our “butcher’s bill” was appallingly heavy, the list totalling up to no less than thirty-eight killed and one hundred and six wounded, out of a total of two hundred and eighty!

Chapter Two.

The Althea founders.

The French having ceased firing, and manifesting an unmistakable anxiety to withdraw from our proximity, we bestowed but little further attention on them, for it quickly became clear to us that our own condition was quite sufficiently serious to tax our energies to the utmost. The first task demanding the attention of the carpenter and his mates was of course the stoppage of our leaks, and a very difficult task indeed it proved to be, owing to the rapidity with which the water was rising in the hold; by manning the pumps, however, and employing the entire available remainder of the crew in baling, we succeeded in plugging all the shot-holes and clearing the hold of water by noon, when the men were knocked off to go to their well-earned dinner. Then, indeed, we found time to look around us and to ask ourselves and each other where the French were and what they were doing. There was no difficulty in furnishing a reply to either question, for our antagonists were only a bare four miles off, and close together. But bad as our own plight was, theirs was very much worse; for we now saw that the frigate which we had raked so unmercifully was in a sinking condition, having settled so low in the water indeed that the sills of her main-deck ports were awash and dipping with every sluggish heave of her upon the low and almost imperceptible swell, while her own boats and those of her consort were busily engaged in taking off her crew. With the aid of my telescope I could distinctly see all that was going on, and I saw also that the end of the gallant craft was so near as to render her disappearance a matter of but a few minutes. Hungry, therefore, as I was, I determined to remain on deck and see the last of her. Nor had I long to wait; I had scarcely arrived at the decision that I would do so, when, as I watched her through my glass, I saw the boats that hung around her shoving off hurriedly one after the other, until one only remained. Presently that one also shoved off, and, loaded down to her gunwale, pulled, as hastily as her overloaded condition would permit, toward the other frigate. She had scarcely placed half a dozen fathoms between herself and the sinking ship before the latter rolled heavily to port, slowly recovered herself, and then rolled still more heavily to starboard, completely burying the whole tier of her starboard ports as she did so. She hung thus for perhaps half a minute, settling visibly all the time; finally she staggered, as it were, once more to an even keel, but with her stern dipping deeper and deeper every second until her taffrail was buried, while her battered bows lifted slowly into the air, when, the inclination of her decks rapidly growing steeper, she suddenly took a sternward plunge and vanished from sight in the midst of a sudden swirl of water that was distinctly visible through the lenses of the telescope. The occupants of the boat that had so recently left her saw their danger and put forth herculean efforts to avoid it; they were too near, however, to escape, and despite all their exertions the boat was caught and dragged back into the vortex created by the sinking ship, into which she too disappeared. But a few seconds afterwards I saw heads popping up above the water again, here and there, while a couple of boats that had just discharged their cargo of passengers dashed away to the rescue and were soon paddling hither and thither among the little black spots that kept popping into view all round them. I waited until all had seemingly been picked up, and then went below to secure what dinner might be remaining for me.

When, after a hurried meal, I again went on deck, the horizon away to the northward and eastward was darkening to a light air from that quarter, that came gently stealing along the glassy surface of the ocean, first in cat’s-paws, then as a gentle breathing that caused the polished undulations to break into a tremor of laughing ripples, and finally into a light breeze, before which the surviving French frigate bore up with squared yards, leaving us unmolested.

Meanwhile the crew, having dined, turned to again for a busy afternoon’s work, which consisted chiefly in clearing away the wreck of our fallen spars, and saving as many of them and as much of our canvas and running gear as would be likely to be of use to us in fitting the ship with a jury-rig. And so well did the men work, that by sunset we were enabled to cut adrift from the wreck of our lower masts, and to bear up in the wake of the Frenchman, who by this time had run us out of sight in the south-western quarter.

But, tired as the men were, there was no rest for them that night, for it was felt to be imperatively necessary to get the ship under canvas again without a moment’s delay; moreover, despite the fact that the shot-holes had all been plugged, it was found that the battered hull was still leaking so seriously as to necessitate a quarter of an hour’s spell at the pumps every two hours. The hands were therefore kept at work, watch and watch, all through the night, with the result that when day broke next morning we had a pair of sheers rigged and on end, ready to rear into position the spars that had been prepared and fitted as lower masts. The end of that day found us once more under sail, after a fashion, and heading on our course to the southward and westward.

For the following two days all went well with us, save that the ship continued to make water so freely as to necessitate the use of the pumps at the middle and end of every watch, a fair breeze driving us along under our jury-canvas at the rate of five to six knots per hour. Toward evening, however, on the second day, signs of a change of weather began to manifest themselves, the sky to windward losing its rich tint of blue and becoming pallid and hard, streaked with mares’ tails and flecked with small, smoky-looking, swift-flying clouds, while the setting sun, as he neared the horizon, lost his radiance and became a mere shapeless blotch of angry red that finally seemed to dissolve and disappear in a broad bank of slate-hued vapour. The sea too changed its colour, from the clear steel-blue that it had hitherto worn to the hue of indigo smirched with black. Moreover, I heard the captain remark to Mr Dawson that the mercury was falling and that he feared we were in for a dirty night.

And, indeed, so it seemed; for about the middle of the second dog-watch the wind lulled perceptibly and we had a sharp rain-squall, soon after which it breezed up again, the wind coming first of all in gusts and then in a strong breeze that, as the night wore on, steadily increased until it was blowing half a gale, with every indication of worse to come. The sea, too, rose rapidly, and came rushing down upon our starboard quarter, high, steep, and foam-crested, causing the frigate to roll and tumble about most unpleasantly under her jury-rig and short canvas. Altogether, the prospects for the night were so exceedingly unpromising that I must plead guilty to having experienced a selfish joy at the reflection that it was my eight hours in.

When I went on deck at midnight that night, I found that the wind had increased to a whole gale, with a very high and confused sea running, over which the poor maimed Althea was wallowing along at a speed of about eight and a half knots, with a dismal groaning of timbers that harmonised lugubriously with the clank of the chain pumps and the swash of water washing nearly knee-deep about the decks—for the hooker laboured so heavily that she was leaking like a basket, necessitating the unremitting use of the pumps throughout the watch. And—worst of all—Keene whispered to me that, even with the pumps going constantly, the water was slowly but distinctly gaining. And thus it continued all through the middle watch.

It was hoped that the gale would not be of long duration, but at eight bells next morning the news was that the mercury was still falling, while the wind, instead of evincing a disposition to moderate, blew harder than ever. And oh, what a dreary outlook it was when, swathed in oilskins, I passed through the hatchway and stepped out on deck! The sky was entirely veiled by an unbroken mass of dark, purplish, slate-coloured cloud that was almost black in its deeper shadows, with long, tattered streamers of dirty whitish vapour scurrying wildly athwart it; a heavy, leaden-hued, white-crested, foam-flecked sea was running, and in the midst of the picture was the poor crippled frigate, rolling and labouring and staggering onward like a wounded sea-bird under her jury-spars and spray-darkened canvas, with a miniature ocean washing hither and thither athwart her heaving deck, and a crowd of panting, straining, half-naked men clustering about her pumps, while others were as busily employed in passing buckets up and down through the hatchways; the whole set to the dismal harmony of howling wind, hissing spray, the wearisome and incessant wash of water, and the groaning and complaining sounds of the labouring hull. The skipper and the first luff were pacing the weather side of the poop together in earnest converse, and at each turn in their walk they both paused for an instant, as by mutual consent, to cast a look of anxious inquiry to windward.

Presently I saw the carpenter coming along the deck with the sounding-rod in his hand. I intercepted him just by the foot of the poop ladder and remarked—

“Well, Chips, what is the best news you have to tell us?”

“The best news?” echoed Chips, with a solemn shake of the head; “there ain’t no best, Mr Courtenay, it’s all worst, sir; there’s over four foot of water in the hold now, and it’s gainin’ on us at the rate of five inches an hour; and if this here gale don’t break pretty quick I won’t answer for the consequences!”

And up he went to make his report to the skipper.

This was bad news indeed, especially for the unfortunate men who were compelled by dire necessity to toil unceasingly at the back-breaking labour of working the pumps; but I felt no apprehension as to our ultimate safety. Five inches of water per hour was a formidable gain for a leak to make in spite of all the pumping and baling that could be accomplished, yet it would take so many hours at that rate to reduce the frigate to a water-logged condition that ere the arrival of that moment the gale would certainly blow itself out, the labouring and straining of the ship would cease, the leak would be got under control again, and all would be well.

But when, at noon that day,—the gale showing no symptoms whatever of abatement,—the captain gave orders for the upper-deck guns to be launched overboard, I began to realise that our condition was such as might easily become critical. And when, about half an hour before sunset, orders were given to throw the main-deck guns overboard, it became borne in upon me that matters were becoming mighty serious with us.

With the approach of night the gale seemed rather to increase in strength than otherwise, while the sea was certainly considerably heavier; and the worst of it was that there was no indication of an approaching change for the better. As for the poor Althea, she certainly did not labour quite so heavily now that she was relieved of the weight of her guns, but the water in the hold still gained steadily upon the pumps, and the more experienced hands among us were beginning to hint at the possibility of our being compelled to leave her and take to the boats. And these hints received something of confirmation when, shortly after the commencement of the first watch, the carpenter and his mates were seen going the rounds of the boats and examining into their condition with the aid of lanterns. Nevertheless, and despite these omens, the men stuck resolutely to the pumps and the baling all through the night, the captain and the first lieutenant animating and encouraging them by their presence throughout the long, dismal, dreary hours of darkness.

About three bells in the morning watch the welcome news spread throughout the ship that the mercury had at length begun to rise again; and with the approach of dawn it became apparent that the gale was breaking, the sky to windward gave signs of clearing, and hope once more sprang up within our breasts. But the men, although still willing and even eager to continue the heart-breaking work of pumping and baling, were by this time utterly worn out; the water in the hold steadily and relentlessly gained upon them, despite their most desperate efforts, and by the arrival of breakfast-time it had become perfectly apparent to everybody that the poor old Althea was a doomed ship!

If, however, there was any doubt as to this in the minds of any of us, it was quickly dispelled, for after breakfast the order was passed to knock off baling; and the men thus relieved were at once set to work under the first and second lieutenants, the one party to prepare a sea anchor, and the other to attend to the provisioning of the boats and get them ready for launching. I was attached to the first lieutenant’s party, or that which undertook the preparation of the sea anchor; and as the idea impressed me as being rather ingenious, I will describe it for the benefit of those who may feel interested in such matters, prefacing my description with the explanation that, in consequence of the springing up of the gale so soon after our action with the Frenchmen, our jury-rig was of a very primitive and incomplete character, such as would enable us to run fairly well before the wind, but not such as would permit of our lying-to; hence the need for a sea anchor, now that the necessity had arisen for us to launch our boats in heavy weather.

The sea anchor was the offspring of the first lieutenant’s inventiveness, and it consisted of an old fore-topsail bent to a couple of booms of suitable length and stoutness. The head of the sail was bent to one of the booms with seizings, in much the same manner as it would have been bent to a topsail yard, while the clews were securely lashed to the extremities of the other boom. Then to the boom which represented the topsail yard was attached, a crow-foot made of two spans of stout hawser, having an eye in the centre of them to which to bend the cable. The lower boom was well weighted by the attachment to it of a number of pigs of iron ballast, as well as our stream anchor; after which the starboard cable was paid out and passed along aft, outside the fore rigging, the end being then brought inboard and bent on to the crow-foot. The whole was then made up as compactly as possible with lashings, after which, by means of tackles aloft, it was hoisted clear of the bulwarks and lowered down over the side; the lashings were then cut and the sail dropped into the water, opening out as it did so, when, the lower boom sinking with the weight attached to it, a broad surface was exposed, acting as a very efficient sea anchor. At the moment when everything was ready to let go, the ship’s helm was put hard over, bringing her broad-side-on to the sea, when, as she drove away to leeward, she brought a strain upon her cable that at once fetched her up head to wind. This part of the process having been successfully accomplished, it was an easy matter to bend a spring on to the cable and heave the ship round broadside-on to the sea once more, in which position she afforded an excellent lee under the shelter of which to launch our boats, which, but for this contrivance, must have inevitably been swamped.

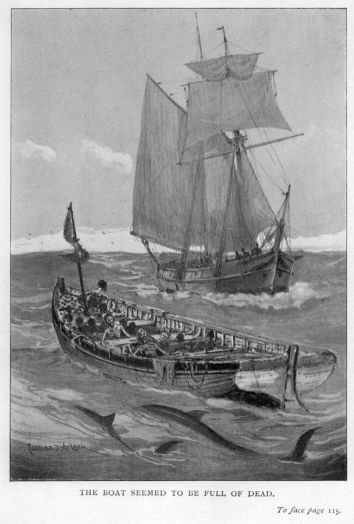

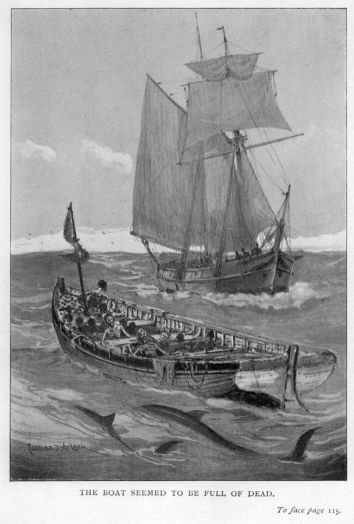

By the time that all this was done the boats were ready for launching, and the captain gave orders for this to be at once proceeded with, beginning with the launch; this being the heaviest boat in the ship, and the most difficult to get into the water. I felt exceedingly doubtful as to the ability of our jury-spars to support the weight of so heavy a craft, but, by staying them well, the delicate task was at length successfully accomplished, when the worst cases among the wounded were brought on deck and carefully lowered over the side into the boat beneath, the doctor, with his instruments and medicine-chest, being already there to receive them. And as soon as she had received her complement, the launch was veered away to leeward at the end of a long line—but still under the shelter of the ship’s hull—to make room for the first cutter. The rest of the boats followed in succession—the men preserving to the very last moment the most admirable order and discipline—until only the captain’s gig, of which I was placed in command, remained. The proper complement of this boat was six men, in addition to the coxswain; but in order that the wounded—who were placed in the launch and the first and second cutters—might be as little crowded as possible, the remainder of the boats received rather more than their full complement, in consequence of which my crew numbered ten, all told, instead of seven. We were the last boat to leave the ship, the skipper having gone below to his cabin for some purpose at the last minute; and I assure you that, the bustle and excitement of getting the men out of the ship being now all over, I found it rather nervous and trying work to stand there in the gangway, waiting for the reappearance of the captain on deck. For the ship was by this time in a sinking condition and liable to go down under our feet at any moment, having settled so low in the water that she rolled her closed main-deck ports completely under with every sickly lurch of her upon the still heavy sea that was now continuously breaking over her, while the water could be distinctly heard washing about down below.

At length the skipper came out of his cabin, bearing in his hand a large japanned tin box.

“Jump down, Mr Courtenay, and stand by to take this box from me,” he cried; and down the side I went, needing no second bidding. The box was carefully passed down to me, and I stowed it away in the stern-sheets. When I had done so, and looked up at the ship, Captain Harrison was standing in the gangway with his hat in his hand, looking wistfully and sorrowfully along the deserted decks and aloft at the jury-spars that, with their rigging, so pathetically expressed the idea of a mortally wounded creature gallantly but hopelessly struggling against the death that was inexorably drawing near. Some such fancy perhaps suggested itself to him, for I distinctly saw him dash his hand across his eyes more than once. At length he turned, descended the side-ladder, and, watching his opportunity, sprang lightly into the boat.

“Shove off, Mr Courtenay!” he ordered, as he wrapped himself in his boat cloak.

“Shove off!” I reiterated in turn, and forthwith away we went, the men nothing loath, as I could clearly see, for the ship was now liable to founder at any moment; indeed the wonder to me was that she remained afloat so long, for she had by this time sunk so deep that her channels were completely buried, only showing when she rolled heavily away from us. Poor old barkie! what a desolate and forlorn object she looked as we pulled away from her, with little more than her bulwarks showing above water, with the seas making a clean breach over her bows continually, as she rolled and plunged with sickening sluggishness to the great ridges of steel-grey water that incessantly swooped down upon her and into which her bows, pinned down by the weight of water within her hull, occasionally bored, as though, tired of the hopeless struggle for existence, she had at length summoned resolution to take the final plunge and so end it all. Again and again I thought she was gone, but again and yet again she emerged wearily and heavily out of the deluges of water that sought to overwhelm her; but at length an unusually heavy sea caught her with her bows pinned down after a plunge into the trough; clear, green, and unbroken it brimmed to her figure-head and poured in a foaming cataract over her bows, sweeping the whole length of her from stem to stern until her hull was completely buried. As the wave left her it was seen that her bows were still submerged, and a moment later it became apparent that the end had come and she was taking her final plunge.

“There she goes!” shouted one of the men; and as the fellow uttered the words the captain rose to his feet in the stern-sheets and doffed his hat, as though he had been standing beside the grave of a dear friend, watching the dear old barkie as, with her stern gradually rising high, she slid slowly and solemnly out of sight, the occupants of the boats giving her a parting cheer as she vanished. The captain stood motionless until the swirl that marked her grave had disappeared, then he replaced his hat, resumed his seat, and remarked—

“Give way, men! Mr Courtenay, be good enough to put me aboard the launch, if you please.”

Chapter Three.

The gig is caught in a hurricane.

Upon reaching the launch, the captain’s first care was to satisfy himself as to the well-being and comfort of the poor wounded fellows aboard her; but the doctor had already attended to this matter, with the result that they were as comfortable as the utmost care and forethought could render them. The master, meanwhile, had been ascertaining the exact latitude and longitude of the spot where the frigate had gone down, and he now communicated the result of his calculations to the captain, who thereupon gave orders for the boats to steer southwest on a speed trial for the day, the leading boat to heave-to at sunset and wait for the rest to close. I had not the remotest notion as to the meaning of this somewhat singular order, but my obvious duty was to execute it; so I forthwith made sail upon the gig, and a very few minutes sufficed to demonstrate that we were the fastest boat of the whole squadron. Nor was this at all surprising, for the gig was not an ordinary service boat; she was the captain’s own private property, having been built to order from his own design, with a special view to the development of exceptional sailing powers, boat-sailing being quite a hobby with him. She was a splendid craft of her kind, measuring thirty feet in length, with a beam of six feet, and she pulled six oars. She was a most beautiful model of the whale-boat type, double-ended, with quite an unusual amount of sheer fore and aft, which gave her a fine, bold, buoyant bow and stern; moreover, these were covered in with light turtle-back decks, that forward measuring six feet in length, while the after turtle-back measured five feet from the stern-post. She was fitted with a keel nine inches deep amidships, tapering off to four inches deep at each end; was rigged as a schooner, with standing fore and main lug and a small jib, and, with her ordinary crew on board and sitting to windward, required no ballast even in a fresh breeze. Small wonder, therefore, was it that, having such a boat under us, we had run the rest of the fleet out of sight by midday, the wind still blowing strong, although it was moderating rapidly.

The first lieutenant was, like the captain, fond of inventing and designing things, but his speciality took the form of logs for determining the speed of craft through the water; and in the course of his experiments he had provided each of the frigate’s boats with an ingenious spring arrangement which, attached to an ordinary fishing-line with a lead weight secured to its outer end, which was continuously towed astern, registered the speed of the boat with a very near approach to perfect accuracy.

The day passed uneventfully away, the wind moderating steadily all the time, and the sun breaking through considerably before noon, enabling me to secure a meridian altitude wherefrom to compute my latitude. The sea, too, was going down, and when the sun set that night the sky wore a very promising fine-weather aspect. As the great golden orb vanished below the horizon we rounded the boat to, lowered our sails, and moored her to a sea anchor made of the oars lashed together in a bundle with the painter bent on to them. And later on, when it fell dark, we lighted a lantern and hoisted it to our fore-masthead, as a beacon for which the other boats might steer. The gig had behaved splendidly all through the day, never shipping so much as a single drop of water, and now that she was riding to her oars she took the sea so easily and buoyantly that I felt as safe as I had ever done aboard the poor old Althea herself, and unhesitatingly allowed all hands to turn in as best they could in the bottom of the boat, undertaking to keep a lookout myself until the other boats had joined company.

The first boat to make her appearance was the service gig in charge of Mr Flowers, the third lieutenant; she ranged up alongside and hove-to about two hours after sunset, soon afterwards following our example by throwing out a sea anchor. Then came the first and second cutters, in command of the first and second lieutenants; the first cutter arriving about an hour after Mr Flowers, while the second cutter appeared about a quarter of an hour later. The launch followed about half an hour astern of the second cutter; but this was not to be wondered at, the former being rather deep, owing to the very generous supply of water that the doctor had insisted on carrying for the comfort of the wounded. Then, some three-quarters of an hour later, came the jolly-boat in charge of the boatswain; and finally the dinghy, carrying four hands and in charge of my friend and fellow-mid, Jack Keene, turned up close upon midnight.

Long ere this, however, we had each in succession spoken the launch, reporting the distance that we had traversed up to sunset. And, with the data thus supplied, the master had gone to work upon a calculation which formed the basis of a sort of table showing the ratio of the speeds of the several boats, with the aid of which the officer in charge of each boat could estimate with a moderate degree of accuracy the position of each of the other boats at any given moment—so long, that is to say, as the wind held fair enough to allow the boats to steer a given course. A copy of this table was then furnished to the officer in command of each boat, after which the captain ordered Mr Flowers to make the best of his way to Barbadoes, with instructions to report the loss of the frigate immediately upon his arrival, with a request to the senior naval officer that a craft of some sort might be forthwith despatched in search of the other boats. Similar instructions were next given to me, except that my port of destination was Bermuda. Of course we each carried a written as well as a verbal message to the senior naval officer of the port to which we were bound; and equally, of course, it was impressed upon us both that if we happened to encounter a friendly craft en route, and could induce her to undertake the search, it would be so much the better. Having received these instructions, and taken young Lindsay out of the launch, which was a trifle over-crowded, I at once made sail and parted company, the occupants of the other boats giving us the encouragement of a farewell cheer as we did so; they also making sail at the same time on a west-south-westerly course, which would afford them about an even chance of being picked up by a craft either from Bermuda or Barbadoes; while, in the event of their being found by neither, they stood a very good chance of hitting off one or another of the Leeward Islands.

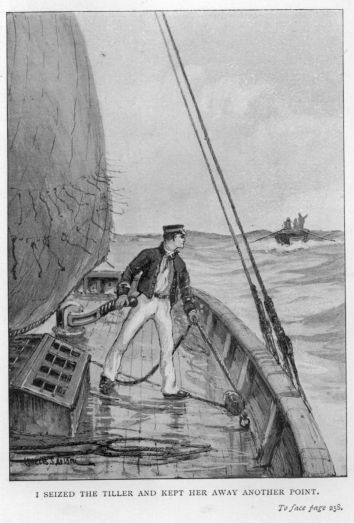

For the remainder of that night we sped gaily onward, with the wind about two points free, making splendid progress; although I am bound to admit that, with the height of sea and the strength of wind that still prevailed, there were moments when the task of sailing the boat became exciting enough to satisfy the cravings of even the most exacting individual. Lindsay and I relieved each other at the tiller, watch and watch, with one hand forward to keep a lookout ahead and to leeward, the rest of the poor fellows being so thoroughly worn out by their long spell at the pumps that rest and sleep was an even more imperative necessity for them than it was for us.

By the time of sunrise the wind had dwindled away to a topgallant breeze, with a corresponding reduction in the amount of sea; we were therefore enabled to shake out the double reef that we had thus far been compelled to carry in our canvas, while the aspect of the sky was more promising than it had been for several days past. The weather was now as favourable as we could possibly wish, the wind being just fresh enough to send us along at top speed, gunwale-to, under whole canvas, while the sea was going down rapidly. But, as the day wore on, the improvement in the weather progressed just a little too far; it became even finer than we wished it, the wind continuing to drop steadily, until by noon we were sliding over the long, mountainous swell at a speed of barely four knots, with the hot sun beating down upon us far too ardently to be pleasant. Needless to say, we kept a sharp lookout for a sail all through the day, but saw nothing; the flying-fish that sparkled out from the ridges of the swell and went skimming away to port and starboard, gleaming as brilliantly in the strong sunlight as a handful of new silver dollars, being the only objects to break the solitude that environed us. By sunset that day the wind had died completely out, leaving the ocean a vast surface of slow-moving, glassy undulations, and I was reluctantly compelled to order the canvas to be taken in, the masts to be struck, and the oars to be thrown out. Then, indeed, as the night closed down upon us and the stars came winking, one by one, out of the immeasurable expanse of darkening blue above us, the silence of the vast ocean solitude that hemmed us in became a thing that might be felt. So oppressive was it that, as by instinct, our conversation gradually dwindled to the desultory exchange of a few whispered remarks, uttered at lengthening intervals, until it died out altogether; while the profound stillness of air and ocean seemed to become accentuated rather than broken by the measured roll of the oars in the rowlocks, and the tinkling lap of the water under the bows and along the bends of the boat. We pulled four oars only instead of six, in order that we might have two relays, or watches, who relieved each other every four hours. The men pulled a long, steady, easy stroke, of a sort that enabled them to keep on throughout the watch without undue fatigue, by taking a five minutes’ spell of rest about once an hour; but it was weary work for the poor fellows, after all, and our progress soon became provokingly slow.

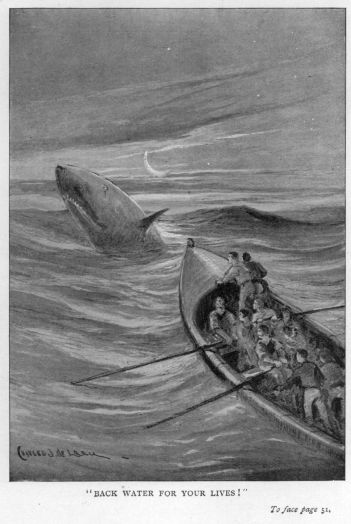

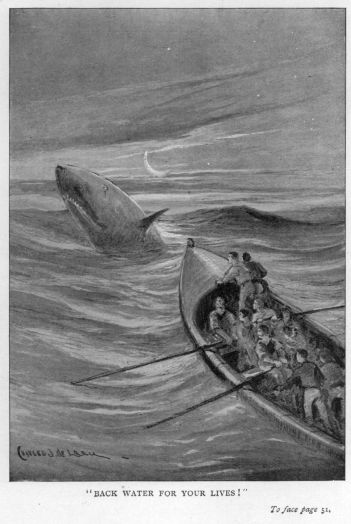

About three bells in the middle watch that night, as I half sat, half reclined in the stern-sheets, drowsily steering by a star, and occasionally glancing over my shoulder at the ruddy, glowing sickle of the rising moon, then in her last quarter, we were all suddenly startled by the sound of a loud, deep-drawn sigh that came to us from somewhere off the larboard bow, apparently at no great distance from the boat; and while we sat wondering and listening, with poised oars, the sound was repeated close aboard of us, but this time on our starboard quarter, accompanied by a soft washing of water; and turning sharply, I beheld, right in the shimmering, golden wake of the moon, a huge, black, shapeless, gleaming bulk noiselessly upheave itself out of the black water and slowly glide up abreast of us until it was alongside and all but within reach of our oars.

“A whale!” whispered one of the men, in tones that were a trifle unsteady from the startling surprise of the creature’s sudden appearance.

“Ay,” replied the man next him, “and that was another that we heard just now; bull and cow, most likely. I only hopes they haven’t got a calf with ’em, because if they have, the bull may take it into his head to attack us; they’re mighty short-tempered sometimes when they have young uns cruisin’ in company! I minds one time when I was aboard the old Walrus—a whaler sailin’ out of Dundee—that was afore I was pressed.”

Another long sigh-like expiration abruptly interrupted the yarn, and close under our bows there rose another leviathan, so closely indeed that, unless it was a trick of the imagination, I felt a slight tremor thrill through the boat, as though he had touched us! Involuntarily I  glanced over the side; and it was perhaps well that I did so, for there, right underneath the boat, far down in the black depths, I perceived a small, faint, glimmering patch of phosphorescence, that, as I looked, grew larger and more distinct, until, in the course of a very few seconds, it assumed the shape of another monster rising plumb underneath us.

glanced over the side; and it was perhaps well that I did so, for there, right underneath the boat, far down in the black depths, I perceived a small, faint, glimmering patch of phosphorescence, that, as I looked, grew larger and more distinct, until, in the course of a very few seconds, it assumed the shape of another monster rising plumb underneath us.

“Back water, men! back water, for your lives! There is one of them coming up right under our keel!” I cried; and, at the words, the men dashed their oars into the water and we backed out of the way, just in time to avoid being hove out of the water and capsized, this fellow happening to come up with something very like a rush. Meanwhile, others were rising here and there all around us, until we found ourselves surrounded by a school of between twenty and thirty whales. It was a rather alarming situation for us; for although the creatures appeared perfectly quiet and well-disposed, there was no knowing at what moment one of them might gather way and run us down, either intentionally or inadvertently; while there was also the chance that another might rise beneath us so rapidly as to render it impossible for us to avoid him. One of the men suggested that we should endeavour to frighten them away by making a noise of some sort; but the former whaler strongly vetoed this proposition, asserting—whether rightly or wrongly I know not—that if we startled them the chances were that those nearest at hand would turn upon us and destroy the boat. We therefore deemed it best to maintain a discreet silence; and in this condition of unpleasant suspense we remained, floating motionless for a full half-hour, the whales meanwhile lying as motionless as ourselves, when suddenly a stir seemed to thrill through the whole herd, and all in a moment they got under way and went leisurely off in a northerly direction, to our great relief. We gave them a full quarter of an hour to get well out of our way, and then the oars dipped into the water once more, and we resumed our voyage.

At daybreak the atmosphere was still as stagnant as it had been all through the night, the surface of the ocean being unbroken by the faintest ripple, save where, about a mile away, broad on our starboard bow, the fin of a solitary shark lazily swimming athwart our course turned up a thin, blue, wedge-shaped ripple as he swam. There was, however, a faint, scarcely perceptible mistiness in the atmosphere that led me to hope we might get a small breeze from somewhere—I little cared where—before the day grew many hours older. At nine o’clock I secured an excellent set of sights for my longitude,—having taken the precaution to set my watch by the ship’s chronometer before parting company with the launch,—and it was depressing to find, after I had worked out my calculations, how little progress we had made during the twenty-one hours since the previous noon. As the morning wore on the mistiness that I had observed in the atmosphere at daybreak passed away, but the sky lost its rich depth of blue, while the sun hung aloft, a dazzling but rayless globe of palpitating fire. A change of some sort was brewing, I felt certain, and I was somewhat surprised that, with such a sky above us, the atmosphere should remain so absolutely stagnant.

As the day wore on, the thin, scarcely perceptible veil of vapour that had dimmed the richness of the sky tints in the early morning gradually thickened and seemed to be assuming somewhat of a distinctness of shape. I just succeeded in securing the meridian altitude of the sun, for the determination of our latitude, but that was all. Half an hour after noon the haze had grown so dense that the great luminary showed through it merely as a shapeless blur of pale, watery radiance, and within another hour he had disappeared altogether from the overcast sky. Still the wind failed to come to our help; the atmosphere seemed to be dead, so absolutely motionless was it; and although the sun had vanished behind the murky vapours that were stealthily and imperceptibly veiling the firmament, the heat was so distressing that the perspiration streamed from every pore, the manipulation of the oars grew more and more languid, and at length, as though actuated by a common impulse, the men gave in, declaring that they were utterly exhausted and could do no more. And I could well believe their assertion, for even I, whose exertions were limited to the steering of the boat, felt that even such slight labour was almost too arduous to be much longer endured. The oars were accordingly laid in, we went to dinner, and then the men flung themselves down in the bottom of the boat, and, with their pipes clenched between their teeth, fell fast asleep, an example which was quickly followed by Lindsay and myself, despite all our efforts to the contrary.

When I awoke it was still breathlessly calm, and I thought for a moment that night had fallen, so dark was it; but upon consulting my watch I found that it still wanted nearly an hour to sunset. But, heavens! what a change had taken place in the aspect of the weather during the four hours or so that I had lain asleep in the stern-sheets of the boat! It is quite possible that, had I remained awake, I should scarcely have been aware of more than the mere fact that the sky was steadily assuming an increasingly sombre and threatening aspect; but, awaking as I did to the abrupt perception of the change that had been steadily working itself out during the previous four hours, it is not putting it too strongly to say that I was startled. For whereas my last conscious memory of the weather, before succumbing to the blandishments of the drowsy god, had been merely that of a lowering, overcast sky, that might portend anything, but probably meant no more than a sharp thunder-squall, I now awakened to the consciousness that the firmament above consisted of a vast curtain of frowning, murky, black-grey cloud, streaked or furrowed in a very remarkable manner from about east-south-east to west-nor’-west, the lower edges of the clouds presenting a curious frayed appearance, while the clouds themselves glowed here and there with patches of lurid, fiery red, as though each bore within its bosom a fiercely burning furnace, the ruddy light of which shone through in places. I had never before beheld a sky like it, but its aspect was sufficiently alarming to convince the veriest tyro in weather-lore that something quite out of the common was brewing; so I at once awoke the slumbering crew to inquire whether any of them could read the signs and tell me what we might expect.

The newly-awakened men yawned, stretched their arms above their heads, and dragged themselves stiffly up on the thwarts, gazing with looks of wonder and alarm at the portentous sky that hung above them.

“Well, if we was in the Chinese seas, I should say that a typhoon was goin’ to bust out shortly,” observed one of them—a grizzled, mahogany-visaged old salt, who had seen service all over the world. “But,” he continued, “they don’t have typhoons in the Atlantic, not as ever I’ve heard say.”

“No, they don’t have typhoons here, but they has hurricanes, which I take to mean pretty much the same thing,” remarked another.

“You are right, Tom,” said I, thus put upon the scent, as it were, “a Chinese typhoon and a West Indian hurricane are the same thing under different names. A third name for them is ‘cyclone’; and as this threatening sky seems to remind Dunn so powerfully of a Chinese typhoon, depend upon it we are going to have a taste of a West Indian hurricane, or cyclone. I have read somewhere that they frequently originate out here in the heart of the Atlantic.”

“If we’re agoin’ to have a typhoon, or a hurricane, or a cyclone—whichever you likes to call it—all I say is, ‘The Lord ha’ mercy upon us,’” remarked Dunn. “Big ships has all their work cut out to weather one o’ them gales; so what are we agoin’ to do in this here open boat, I’d like to know?”

“Have you ever been through a typhoon, Dunn?” I asked.

“Yes, sir, I have, and more than one of ’em,” was the reply. “I was caught in one off the Paracels, in the old Audacious frigate,—as fine a sea-boat as ever was launched,—and, in less time than it takes to tell of it, we was dismasted and hove down on our beam-ends; and it took us all our time to keep the hooker afloat and get her into Hong-Kong harbour. And the very next year I was catched again—in the Bashee Channel, this time—in the Lively schooner, of six guns. We knowed it was comin’; it gived us good warnin’ and left us plenty of time to get ready for it; so Mr Barker—the lieutenant in command—gived orders to send the yards and both topmasts down on deck, and rig in the jib-boom; and then he stripped her down to a close-reefed boom foresail. But we capsized—reg’larly ‘turned turtle’—when the gale struck us, and only five of us lived to tell the tale. As to this here boat, if a hurricane anything at all like them Chinee typhoons gets hold of her, why, we shall just be blowed clean away out o’ water and up among the clouds! And that’s just what’s goin’ to happen, if signs counts for anything.”

Wherewith the speaker thrust both hands into his trouser pockets, disgustedly spat a small ocean of tobacco-juice overboard, and subsided into gloomy silence.

It was a sufficiently alarming retrospect, in all conscience, to which we had just listened, and the prophetic utterance wherewith it had been wound up, while powerfully suggestive of a highly novel and picturesque experience in store for us, was certainly not attractive enough to cause us to look forward to its fulfilment with undisturbed serenity; nevertheless, I did not feel like tamely giving in without making some effort to save the boat and the lives with which I had been entrusted, so I set myself seriously to consider how we could best utilise such time as might be allowed us, in making some sort of preparation to meet the now confidently-expected outburst. I looked over our resources, and found that they consisted, in the main, of eight oars, two boat-hooks, two masts, two yards, three sails, half a coil of two-inch rope that some thoughtful individual had pitched into the boat when getting her ready for launching, half a coil of ratline and two large balls of spun-yarn, due to the forethought of the same or some other individual, a painter some ten fathoms long, and the boat’s anchor, together with the gratings, stretchers, and other fittings belonging to the boat, and a few oddments that might or might not prove useful.

Was it possible to do anything with these? After considering the matter carefully I thought it was. The greatest danger to which we were likely to be exposed seemed to me to consist in our being swamped by the flying spindrift and scud-water or by the breaking seas, and if we could by any means contrive to keep the water out there was perhaps a bare chance that we might be able to weather the gale. And, after a little further consideration, I thought that what I desired to do might possibly be accomplished by means of the boat’s sails, which were practically new, and made of very light, but closely woven canvas, that ought to prove water-tight. So, having unfolded my ideas to the men, we all went to work with alacrity to put them to the test of actual practice.

Of course it was utterly useless to think of scudding before the gale; our only hope of living through what was impending depended upon our ability to keep the boat riding bows-on to the sea, and to do this it became necessary for us to improvise a sea anchor again. This was easily done by lashing together six of our eight oars in a bundle, three of the blades at one end and three at the other, with the boat anchor lashed amidships to sink the oars somewhat in the water and give them a grip of it. A span, made by doubling a suitable length of our two-inch rope, was bent on to the whole affair, and the boat’s painter was then bent on to the span, when the apparatus was launched overboard, and our sea anchor was ready for service.

Our next task was to cut the two lug-sails adrift from their yards. The mainsail was then doubled in half, and one end spread over the fore turtle-back and drawn taut. Over this, outside the boat and under her keel, we then passed a length of our two-inch rope, girding the boat with it and confining the fore end of the sail to the turtle-back, when, with the aid of one of the stretchers, we were able to heave this girth-rope so taut as to render it impossible for the sail to blow away. But before heaving it taut, we passed a second girth-rope round the boat over the after turtle-back, next connecting both girth-ropes together by lengths of rope running fore and aft along the outside of the boat underneath the edge of the top strake. The doubled mainsail was then strained taut across the boat, and its edges tucked underneath the fore-and-aft lines outside the boat; the foresail was treated in the same way, but with its fore edge overlapped by about a foot of the after edge of the mainsail. Our girth-ropes were then hove taut, with the finished result that we had a canvas deck covering the boat from the fore turtle-back to within about six feet of the after one. The edges of the sails were next turned up and secured by seizings on either side, and our deck was complete. But, as it then stood, I was not satisfied with it, for at the after extremity of it there was an opening some six feet long, and as wide as the boat, through which a very considerable quantity of water might enter—quite enough, indeed, to swamp the boat. And with our canvas deck lying flat, as it then was, there was no doubt that very large quantities of water would wash over it, and pour down through the opening, should the sea run heavily. Our deck needed to be sloped upward from the forward to the after end of the boat, so that any water which might break over it would flow off on either side before reaching the opening to which I have referred. We accordingly laid the boat’s mainmast along the thwarts fore and aft, amidships, and lashed the heel firmly to the middle of the foremost thwart. Then, by lashing our two longest stretchers together, we made a crutch for the head or after end of the mast to rest in; when, by placing this crutch upright in the stern-sheets against the back-board, we were able to raise the mast underneath the sails until it not only formed a sort of ridge-pole, converting the sails into a sloping roof, but it also strained the canvas as tight as a drum-head, rendering it so much the less liable to blow away, while it at the same time afforded a smooth surface for the water to pour off, and it also possessed the further advantage that it gave us a little more headroom underneath the canvas deck or roof. This completed our preparations—none too soon, for it was now rapidly growing dark, and the light of our lantern was needed while putting the finishing touches to our work.

Our task accomplished, we of course at once extinguished our lantern,—for candles were scarce with us,—and we then for the first time became aware of the startling rapidity with which the night seemed to have fallen; for with the extinguishment of the lantern we found ourselves enwrapped in darkness so thick that it could almost be felt. This, however, proved to be only transitory, for with the lapse of a few minutes our eyes became accustomed to the gloom, and we were then able not only to discern the shapes of the vast pile of clouds that threateningly overhung us, but also their reflections in the oil-smooth water, the latter made visible by the dull, ruddy glow emanating from the clouds themselves, which was even more noticeable now than it had been before nightfall, and which was so unnatural and appalling a sight that I believe there was not one of us who was not more or less affected by it. It was the first time that I had ever beheld such a sight, and I am not ashamed to confess that the sensation it produced in me was, for a short time, something very nearly akin to terror, so dreadful a portent did it seem to be, and so profoundly impressed was I with our utter helplessness away out there in mid-ocean, in that small, frail boat, with no friendly shelter at hand, and nothing to protect us from the gathering fury of the elements—nothing, that is to say, but the hand of God; and—I say it with shame—I thought far too little of Him in those days.