Harry Collingwood

"Harry Escombe"

Chapter One.

How the Adventure Originated.

The hour was noon, the month chill October; and the occupants—a round dozen in number—of Sir Philip Swinburne’s drawing office were more or less busily pursuing their vocation of preparing drawings and tracings, taking out quantities, preparing estimates, and, in short, executing the several duties of a civil engineers’ draughtsman as well as they could in a temperature of 35° Fahrenheit, and in an atmosphere surcharged with smoke from a flue that refused to draw—when the door communicating with the chief draughtsman’s room opened and the head of Mr Richards, the occupant of that apartment, protruded through the aperture. At the sound of the opening door the draughtsmen, who were acquainted with Mr Richards’s ways, glanced up with one accord from their work, and the eye of one of them was promptly caught by Mr Richards, who, raising a beckoning finger, remarked:

“Escombe, I want you,” and immediately retired.

Thereupon Escombe, the individual addressed, carefully wiped his drawing pen upon a duster, methodically laid the instrument in its proper place in the instrument case, closed the latter, and, descending from his high stool, made his way into the chief draughtsman’s room, closing the door behind him. He did this with some little trepidation; for these private interviews with his chief were more often than not of a distinctly unpleasant character, having reference to some stupid blunder in a calculation, some oversight in the preparation of a drawing, or something of a similar nature calling for sharp rebuke; and as the lad—he was but seventeen—accomplished the short journey from one room to the other he rapidly reviewed his most recent work, and endeavoured to decide in which job he was most likely to have made a mistake. But before he could arrive at a decision on this point he was in the presence of Mr Richards, and a single glance at the chief draughtsman’s face—now that it could be seen clearly and unveiled by a pall of smoke—sufficed to assure Harry Escombe that in this case at least he had nothing in the nature of censure to fear. For Mr Richards’s face was beaming with satisfaction, and a large atlas lay open upon the desk at which he stood.

“Sit down, Escombe,” remarked the dreaded potentate as he pointed to a chair.

Escombe seated himself; and then ensued a silence of a full minute’s duration. The potentate seemed to be meditating how to begin. At length—

“How long have you been with us, Escombe?” he enquired, hoisting himself onto a stool as he put the question.

“A little over two years,” answered Escombe. “I signed my articles with Sir Philip on the first of September the year before last, and came on duty the next day.”

“Two years!” ejaculated Mr Richards. “I did not think it had been so long as that. But time flies when one is busy, and we have done a lot of work during the last two years. Then you have only another year of pupilage to serve, eh, Escombe?”

“Only one year more, Mr Richards,” answered the lad.

“Ah!” commented Mr Richards, and paused again, characteristically. “Look here, Escombe,” he resumed; “you have done very well since you came here; Sir Philip is very pleased with you, and so am I. I have had my eye on you, and have seen that you have been studying hard and doing your best to perfect yourself in all the details of your profession. So far as theory goes you are pretty well advanced. What you need now is practical, out-of-door work, and,” laying his hand upon the open atlas, “I have got a job here that I think will just suit you. It is in Peru. Do you happen to know anything of Peru?”

Escombe confessed that his knowledge of Peru was strictly confined to what he had learned about that interesting country at school.

“It is the same with me,” admitted Mr Richards. “All I know about Peru is that it is a very mountainous country, which is the reason, I suppose, why there is considerably less than a thousand miles of railway throughout the length and breadth of it. And what there is is made up principally of short bits scattered about here and there. But there is some talk of altering all that now, and matters have gone so far that Sir Philip has been commissioned to prepare a scheme for constructing a railway from a place called Palpa—which is already connected with Lima and Callao—to Salinas, which is connected with Huacho, and from Huacho to Cochamarca and thence to a place called Cerro de Pasco, which in its turn is connected with Nanucaca; and from Nanucaca along the shore of Lake Chinchaycocha to Ayacucho, Cuzco, and Santa Rosa, which last is connected by rail with Mollendo, on the coast. There is also another scheme afoot which will involve the taking of a complete set of soundings over the length and breadth of Lake Titicaca. Now, all this means a lot of very important and careful survey work which I reckon will take the best part of two years to accomplish. Sir Philip has decided to entrust the work to Mr Butler, who has already done a great deal of survey work for him, as of course you know; but Mr Butler will need an assistant, and Sir Philip, after consultation with me, has decided to offer that post to you. It will be a splendid opportunity for you to acquire experience in a branch of your profession that you know very little of, as yet; and if the scheme should be carried out, you, in consequence of the familiarity with the country which you will have acquired, will stand an excellent chance of obtaining a good post on the job. Now, what do you say, Escombe; are you willing to go? Your pay during the survey will be a guinea a day—seven days a week—beginning on the day you sail from England and ending on the day of your return; first-class passage out and home; all expenses paid; twenty-five pounds allowed for a special outfit; and everything in the shape of surveying instruments and other necessaries, found. After your return you will of course be retained in the office to work out the scheme, at a salary to be agreed upon, which will to a great extent depend upon the way in which you work upon the survey; while, in the event of the scheme being carried out, you will, as I say, doubtless get a good post on the engineering staff, at a salary that will certainly not be less than your pay during the survey, and may possibly be a good deal more.”

Young Escombe’s heart leapt within him, for here was indeed a rosy prospect suddenly opening out before him, a prospect which promised to put an abrupt and permanent end to certain sordid embarrassments that of late had been causing his poor widowed mother a vast amount of anxiety and trouble, and sowing her beloved head with many premature white hairs. For Harry’s father had died about four months before this story opens, leaving his affairs in a condition of such hopeless disorder that the family lawyer had only just succeeded in disentangling them, with the result that the widow had found herself left almost penniless, with no apparent resource but to allow her daughter Lucy to go out into a cold, unsympathetic world to earn her own living and face the many perils that lurk in the path of a young, lovely, innocent, and unprotected girl. But here was a way out of all their difficulties; for, as Harry rapidly bethought himself, if all his expenses were to be paid while engaged upon the survey, he could arrange for at least three hundred pounds of his yearly salary to be paid to his mother at home, which, with economy and what little she had already, would suffice to enable her and Lucy to live in their present modest home, free from actual want.

There was but one fly in his ointment, one disturbing item in the alluring programme which Mr Richards had sketched out, and that was Mr Butler, the man who was to be Escombe’s superior during the execution of the survey. This man was well known to the occupants of Sir Philip Swinburne’s drawing office as a most tyrannical, overbearing man, with an arrogance of speech and offensiveness of manner and a faculty for finding fault that rendered it absolutely impossible to work amicably with him, and at the same time retain one’s self respect. Moreover, it was asserted that if there were two equally efficient methods of accomplishing a certain task, he would invariably insist upon the adoption of that method which involved the greatest amount of difficulty, discomfort, and danger, and then calmly sit down in safety and comfort to see it done. Mr Richards had said that Escombe would, upon his return to England, be retained in the office to work out the scheme, at a salary the amount of which would “to a great extent depend upon the way in which he worked on the survey”; and it seemed to Harry that Sir Philip’s estimate of the way in which he worked on the survey would be almost entirely based upon Mr Butler’s report. Now it was known that, in addition to possessing the unenviable attributes already mentioned, Butler was a most vindictive man, cherishing an undying enmity against all who had ever presumed to thwart or offend him, and he seemed to be one of those unfortunately constituted individuals whom it was impossible to avoid offending. It is therefore not to be wondered at if Escombe hesitated a moment before accepting Mr Richards’s offer.

“Well, Escombe, what do you say?” enquired the chief draughtsman, after a somewhat lengthy pause. “You do not seem to be very keen upon availing yourself of the opportunity that I am offering you. Is it the climate that you are afraid of? I am told that Peru is a perfectly healthy country.”

“No, Mr Richards,” answered Escombe. “I am not thinking of the climate; it is Mr Butler that is troubling me. You must be fully aware of the reputation which he holds in the office as a man with whom it is absolutely impossible to work amicably. There is Munro, who helped him in that Scottish survey, declares that nothing would induce him to again put himself in Mr Butler’s power; and you will remember what a shocking report Mr Butler gave of Munro’s behaviour during the survey. Yet the rest of us have found Munro to be invariably most good natured and obliging in every way. Then there was Fielding—and Pierson—and Marshall—”

“Yes, I know,” interrupted Mr Richards rather impatiently. “I have never been able to rightly understand those affairs, or to make up my mind which was in the wrong. It may be that there were faults on both sides. But, be that as it may, Mr Butler is a first-rate surveyor; we have always found his work to be absolutely accurate and reliable; and Sir Philip has given him this survey to do; so it is too late for us to draw back now, even if Sir Philip would, which I do not think in the least likely. So, if you do not feel inclined to take on the job—”

“No; please do not mistake my hesitation,” interrupted Escombe. “I will take the post, most gratefully, and do my best in it; only, if Mr Butler should give in an unfavourable report of me when all is over, I should like you to remember that he has done the same with everybody else who has gone out under him; and please do not take it for granted, without enquiry, that his report is perfectly just and unbiased.”

This was a rather bold thing for a youngster of Escombe’s years to say in relation to a man old enough to be his father; but Mr Richards passed it over—possibly he knew rather more about those past episodes than he cared to admit—merely saying:

“Very well, then; I dare say that will be all right. Now you had better go to Mitford and draw the money for your special outfit; also get from him a list of what you will require; and to-morrow you can take the necessary time to give your orders before coming to the office. But you must be careful to make sure that everything is supplied in good time, for you sail for Callao this day three weeks.”

The enthusiasm which caused Escombe’s eyes to shine and his cheek to glow as he strode up the short garden path to the door of the trim little villa in West Hill, Sydenham, that night, was rather damped by the reception accorded by his mother and sister to the glorious news which he began to communicate before even he had stepped off the doormat. Where the lad saw only an immediate increase of pay that would suffice to solve the problem of the family’s domestic embarrassments, two years of assured employment, with a brilliant prospect beyond, a long spell of outdoor life in a perfect climate and in a most interesting and romantic country, during which he would be perfecting himself in a very important branch of his profession, and, lastly, the possibility of much exciting adventure, Mrs Escombe and Lucy discerned a long sea voyage, with its countless possibilities of disaster, two years of separation from the being who was dearer to them than all else, the threat of strange and terrible attacks of sickness, and perils innumerable from wild beasts, venomous reptiles and insects, trackless forests, precipitous mountain paths, fathomless abysses, swift-rushing torrents, fierce tropical storms, earthquakes, and, worse than all else, ferocious and bloodthirsty savages! What was money and the freedom from care and anxiety which its possession ensured, compared with all the awful dangers which their darling must brave in order to win it? These two gently nurtured women felt that they would infinitely rather beg their bread in the streets than suffer their beloved Harry to go forth, carrying his life in his hands, in order that they might be comfortably housed and clothed and sufficiently fed! And indeed the picture which they drew was sufficiently alarming to have daunted a lad of nervous and timid temperament, and perhaps have turned him from his purpose. But Harry Escombe was a youth of very different mould, and was built of much sterner stuff. There was nothing of the milksop about him, and the dangers of which his mother and sister spoke so eloquently had no terrors for him, but, on the contrary, constituted a positive and very powerful attraction; besides, as he pointed out to his companions, he would not always be clinging to the face of a precipice, or endeavouring to cross an impassable mountain torrent. Storms did not rage incessantly in Peru, any more than they did elsewhere; Mr Richards had assured him that the climate was healthy; ferocious animals and deadly reptiles did not usually attack a man unless they were interfered with; and reference to an Encyclopaedia disclosed the fact that Peru, so far from swarming with untamed savages, was a country enjoying a very fair measure of civilisation. Talking thus, making light of such dangers as he would actually have to face, and dwelling very strongly upon the splendid opening which the offer afforded him, the lad gradually brought his mother and sister into a more reasonable frame of mind, until at length, by the time that the bedroom candles made their appearance, the two women, knowing how completely Harry had set his heart upon going, and recognising also the strength of his contention as to the advantageous character of the opening afforded him by Mr Richards’s proposal, had become so far reconciled to the prospect of the separation that they were able to speak of it calmly and to conceal the heartache from which both were suffering. So on the following morning Mrs Escombe and Lucy were enabled to sally forth with cheerful countenance and more or less sprightly conversation as they accompanied the lad to town to assist him in the purchase of his special outfit, the larger portion of which was delivered at The Limes that same evening, and at once unpacked for the purpose of being legibly marked and having all buttons securely sewn on by two pairs of loving hands.

The following three weeks sped like a dream, so far as the individual chiefly interested was concerned; during the day he was kept continually busy by Mr Butler in the preparation of lists of the several instruments, articles, and things—from theodolites, levels, measuring chains, steel tapes, ranging rods, wire lines, sounding chains, drawing and tracing paper, cases of instruments, colour boxes, T-squares, steel straight-edges, and drawing pins, to tents, camp furniture, and saddlery—and procuring the same. The evenings were spent in packing and re-packing his kit as the several articles comprising it came to hand, diversified by little farewell parties given in his honour by the large circle of friends with whom the Escombes had become acquainted since their arrival and settlement in Sydenham. At length the preparations were all complete; the official impedimenta—so to speak—had all been collected at Sir Philip Swinburne’s offices in Victoria Street, carefully packed in zinc-lined cases, and dispatched for shipment in the steamer which was to take the surveyors to South America. Escombe had sent on all his baggage to the ship in advance, and the morning came when he must say good-bye to the two who were dearest to him in all the world. They would fain have accompanied him to the docks and remained on board with him until the moment arrived for the steamer to haul out into the river and proceed upon her voyage; but young Escombe had once witnessed the departure of a liner from Southampton and had then beheld the long-drawn-out agony of the protracted leave taking, the twitching features, the sudden turnings aside to hide and wipe away the unbidden tear, the heroic but futile attempts at cheerful, light-hearted conversation, the false alarms when timid people rushed ashore, under the unfounded apprehension that they were about to be carried off across the seas, and the return to the ship to say goodbye yet once again when they found that their fears were groundless. He had seen all this, and was quite determined that his dear ones should not undergo such torture of waiting, he therefore so contrived that his good-bye was almost as brief and matter of fact as though he had been merely going up to Westminster for the day, instead of to Peru for two years. Taking the train for London Bridge, he made his way thence to Fenchurch Street and so to Blackwall, arriving on board the s.s. Rimac with a good hour to spare.

But, early as he was, he found that not only had Mr Butler arrived on board before him, but also that that impatient individual had already worked himself into a perfect frenzy of irritation lest he—Harry—should allow the steamer to leave without him.

“Look here, Escombe,” he fumed, “this sort of thing won’t do at all, you know. I most distinctly ordered you to be on board in good time this morning. I have been searching for you all over the ship; and now, at a quarter to eleven o’clock, you come sauntering on board with as much deliberation as though you had days to spare. What do you mean by being so late, eh?”

“Really, Mr Butler,” answered Harry, “I am awfully sorry if I have put you out at all, but I thought that so long as I was on board in time to start with the ship it would be sufficient. As it is I am more than an hour to the good; for, as you are aware, the ship does not haul out of dock until midday. Have you been wanting me for anything in particular?”

“No, I have not,” snapped Butler. “But I was naturally anxious when I arrived on board and found that you were not here. If you had happened to miss the ship I should have been in a pretty pickle; for this Peruvian survey is far too big a job for me to tackle singlehanded.”

“Of course,” agreed Escombe. “But you might have been quite certain that I would not have been so very foolish as to allow the ship to leave without me. I am far too anxious to avail myself of the opportunity which this survey will afford me, to risk the loss of it by being late. Is there anything that you want me to do, Mr Butler? Because, if not, I will go below and arrange matters in my cabin.”

“Very well,” assented Butler ungraciously. “But, now that you are on board, don’t you dare to leave the ship and go on shore again—upon any pretence whatever. Do you hear?”

“You really need not feel the slightest apprehension, Mr Butler,” replied Harry. “I have no intention or desire to go on shore again.” And therewith he made his way to the saloon companion, and thence below to his sleeping cabin, his cheeks tingling with shame and anger at having been so hectored in public; for several passengers had been within earshot and had turned to look curiously at the pair upon hearing the sounds of Butler’s high-pitched voice raised in anger.

“My word,” thought the lad, “our friend Butler is beginning early! If he is going to talk to me in that strain on the day of our departure, what will he be like when we are ready to return home? However, I am not going to allow him to exasperate me into forgetting myself, and so answering him as to give him an excuse for reporting me to Sir Philip for insolence or insubordination; there is too much depending upon this expedition for me to risk anything by losing my temper with him. I will be perfectly civil to him, and will do my duty to the very best of my ability, then nothing very serious can possibly happen.”

Upon entering his cabin Escombe was greatly gratified to learn from the steward that he was to be its sole occupant. He at once annexed the top berth, and proceeded to unpack the trunk containing the clothing and other matters that he would need during the voyage, arranged his books in the rack above the bunk, and then returned to the deck just in time to witness the operation of hauling out of dock.

He found Butler pacing the deck in a state of extreme agitation.

“Where have you been all this while?” demanded the man, halting abruptly, square in Escombe’s path. “What do you mean by keeping out of my sight so long? Are you aware, sir, that I have spent nearly an hour at the gangway watching to see that you did not slink off ashore?”

“Have you, really?” retorted Harry. “There was not the slightest need for you to do so, you know, Mr Butler, for I distinctly told you that I did not intend to go ashore again. Didn’t I?”

“Yes, you did,” answered Butler. “But how was I to know that you would keep your word?”

“I always keep my word, sir; as you will learn when we become better acquainted,” answered the lad.

“I hope so, for your sake,” returned Butler. “But my experience of youngsters like yourself is that they are not to be trusted.” Then, glancing round him and perceiving that several passengers in his immediate neighbourhood were regarding him with unconcealed amusement, he hastily retreated below. As he did so, a man who had been lounging over the rail close at hand, smoking a cigar as he watched the traffic upon the river, turned, and regarding Escombe with a good-natured smile, remarked:

“Your friend seems to be a rather cantankerous chap, isn’t he? He will have to take care of himself, and keep his temper under rather better control, or he will go crazy when we get into the hot weather. Is he often taken like that?”

“I really don’t know,” answered Harry. “The fact is that I only made his acquaintance about three weeks ago; but I fear that he suffers a great deal from nervous irritability. It must be a very great affliction.”

“It is, both to himself and to others,” remarked the stranger dryly. “I have met his sort before, and I find that the only way to deal with such people is to leave them very severely alone. He seems to be a bit of a bully, so far as I can make out, but he will have to mind his p’s and q’s while he is on board this ship, or he will be getting himself into hot water and finding things generally made very unpleasant for him. You are in his service, I suppose?”

“Yes, in a way I am,” answered Escombe with circumspection; “that is to say, we are both in the same service, but he is my superior.”

“I see,” answered the stranger. “How far are you going in the ship?”

“We are going to Callao,” answered Harry.

“To Peru, eh?” returned the stranger. “So am I. I know the country pretty well. I have lived in Lima for the last nine years, and I can tell you that when your friend gets among the Peruvians he will have to pull in his horns a good bit. They are rather a peppery lot, are the Peruvians, and if he attempts to talk to them as he has talked to you to-day, he will stand a very good chance of waking up some fine morning with a long knife between his ribs.”

“Oh, I hope it will not come to that!” exclaimed Escombe. “But—to leave the subject of my friend and his temper for the present—since you have lived in Peru so long, perhaps you can tell me something about the country, what it is like, what is the character of its climate, and so on. It is possible that I may have to spend a year or so in it. I should therefore be glad to learn something about it, and to get such tips as to the manner of living, and so on, as you can give me before we land.”

“Certainly,” answered the stranger; “I shall be very pleased indeed to give you all the information that I possibly can, and I fancy there are very few people on board this ship who know more about Peru than I do.”

And therewith Escombe’s new acquaintance proceeded to hold forth upon the good and the bad points of the country to which they were both bound, describing in very graphic language the extraordinary varieties of climate to be met with on a journey inland from the coast, the grandeur of its mountain scenery, the astonishing variety of its products, its interesting historical remains; the character of the aboriginal Indians, the beliefs they cherish, and the legends which have been preserved and handed down by them from father to son through many generations; the character and abundance of its mineral wealth, and a variety of other interesting information; so that by the time that Harry went down below to luncheon, he had already become possessed of the feeling that to him Peru was no longer a strange and unknown land.

Chapter Two.

The Chief Officer’s Yarn.

Upon entering the saloon and searching for his place, Harry found that, much to his satisfaction, he had been stationed at the second table, presided over by the chief officer of the ship—a very genial individual named O’Toole, hailing from the Emerald Isle—and between that important personage and his recently-made Peruvian acquaintance, whose name he now discovered to be John Firmin; while Mr Butler, it appeared, had contrived to get himself placed at the captain’s table, which was understood to be occupied by the élite of the passengers. With the serving of the soup Escombe was given a small printed form, which he examined rather curiously, not quite understanding for the moment what it meant.

Mr Firmin volunteered enlightenment. “That,” he explained, “is an order form, upon which you write the particular kind of liquid refreshment—apart from pure water—with which you wish to be served. You fill it in and hand it to your own particular table steward, who brings you what you have ordered, and at the end of each week he presents you with the orders which you have issued, and you are expected to settle up in spot cash. Very simple, isn’t it?”

“Perfectly,” agreed Harry. “But supposing that one does not wish to order anything, what then?”

“You leave the order blank, that is all,” answered Firmin. Then noticing that the lad pushed the form away, he asked: “Are you a teetotaler?”

“By no means,” answered Harry; “I sometimes take a glass of wine or beer, and very occasionally, when I happen to get wet through or am very cold, I take a little spirits; but plain or aerated water usually suffices for me.”

“I see,” remarked Firmin. He remained silent for a few seconds, then turning again to Harry, he said: “I wonder if you would consider me very impertinent if, upon the strength of our extremely brief acquaintance, I were to offer you a piece of advice?”

“Certainly not,” answered Harry. “You are much older and more experienced than I, Mr Firmin, and have seen a great deal more of the world than I have; any advice, therefore, that you may be pleased to give me I shall be most grateful for, and will endeavour to profit by.”

“Very well, then,” said Firmin, “I will risk it, for I have taken rather a fancy to you, and would willingly do you a good turn. The advice that I wish to give you is this. Make a point of eschewing everything in the nature of alcohol. Have absolutely nothing to do with it. You are young, strong, and evidently in the best of health; your system has therefore no need of anything having the character of a stimulant. Nay, I will go farther than that, and say that you will be very much better, morally and physically, without it; and even upon the occasions which you mention of getting wet or cold, a cup of scalding hot coffee, swallowed as hot as you can take it, will do you far more good than spirits. I am moved to say this to you, my young friend, because I have seen so many lads like you insensibly led into the habit of taking alcohol, and when once that habit is contracted it is more difficult than you would believe to break it off. I have known many promising young fellows who have made shipwreck of their lives simply because they have not possessed the courage and strength of mind to say ‘no’ when they have been invited to take wine or spirits.”

“By the powers, Misther Firmin, ye niver spoke a thruer word in your life than that same,” cut in the chief officer, who had been listening to what was said. “Whin I was a youngster of about Misther Escombe’s age I nearly lost my life through the dhrink. I was an apprentice at the time aboard a fine, full-rigged iron clipper ship called the Joan of Arc. We were outward bound, from London to Sydney, full up with general cargo, and carried twenty-six passengers in the cuddy, and nearly forty emigrants in the ’tween decks. We had just picked up the north-east trades, blowing fresh, and the ‘old man’, who was a rare hand at carrying on, and was eager to break the record, was driving her along to the south’ard under every rag that we could show to it, including such fancy fakements as skysails, ringtails, water-sails, and all the rest of it. It was a fine, clear, starlit night, with just the trade-clouds driving along overhead, but there was no moon, and consequently, when an exceptionally big patch of cloud came sweeping up, it fell a bit dark. Still, there was no danger—or ought to have been none—for we were well out of the regular track of the homeward-bounders, and in any case, with a proper look-out, it would have been possible to see another craft plenty early enough to give her a good wide berth. But after Jack has got as far south as we then were he is apt to get a bit careless in the matter of keeping a look-out—trusts rather too much to the officer of the watch aft, you know, and is not above snatching a cat-nap in the most comfortable corner he can find, instead of posting himself on the heel of the bowsprit, with his eyes skinned and searching the sea ahead of him.

“Now, it happened—although none of us knew it until it was too late—that our chief mate had rather too strong a liking for rum; not that he was exactly what you might call a drunkard, you know, but he kept a bottle in his cabin, and was in the habit of taking a nip just whenever he felt like it, especially at night time; and on this particular night that I’m talking about he must have taken a nip too many, for when he came on deck at midnight to keep the middle watch he hadn’t been up above an hour before he coiled himself down in one of the passenger’s deck-chairs and—went to sleep. Of course, under such circumstances as those of which I am speaking—the weather being fine and the wind steady, with no necessity to touch tack or sheet—the watch on deck don’t make any pretence of keeping awake; they’re on deck and at hand all ready for a call if they’re needed, and that’s as much as is expected of ’em at night time, since there’s no work to be done; and the consequence was that all hands of us were sound asleep long before the mate; and there is no doubt that the look-out—who lost his life, poor chap! through his carelessness—fell asleep too. As to the man at the wheel, well he is not expected to steer the ship and keep a look-out at the same time, and, if he was, he couldn’t do it, for his eyes soon grow so dazzled by the light of the binnacle lamps that he can see little or nothing except the illuminated compass card.

“That, gentlemen, was the state of affairs aboard the Joan of Arc on the night about which I’m telling ye; the skipper, the passengers, the second mate, and the watch below all in their bunks; and the rest of us, those who were on deck and ought to have been broad awake, almost if not quite as sound asleep as those who were below. I was down on the main deck, sitting on the planks, with my back propping up the front of the poop, my arms crossed, and my chin on my chest, dhreaming that I was back at school in dear old Dublin, when I was startled broad awake by a shock that sent me sprawling as far for’ard as the coaming of the after-hatch, to the accompaniment of the most awful crunching, ripping, and crashing sounds, as the Joan sawed her way steadily into the vitals of the craft that we had struck. Then, amid the yelling of the awakened watch, accompanied by muffled shrieks and shouts from below, there arose a loud twang-twanging as the backstays and shrouds parted under the terrific strain suddenly thrown upon them, then an ear-splitting crash as the three masts went over the bows, and I found myself struggling and fighting to free myself from the raffle of the wrecked mizenmast. I felt very dazed and queer, and a bit sick, for I was dimly conscious of the fact that I had been struck on the head by something when the masts fell, and upon putting up my hand I found that my hair was wet with something warm that was soaking it and trickling down into my eyes and ears. Then I heard the voice of the ‘old man’ yelling for the mate and the carpenter; and as I fought myself clear of the raffle I became aware of many voices frantically demanding to know what had happened, husbands calling for their wives, mothers screaming for their children, the sound of axes being desperately used to clear away the wreck, a sudden awful wail from somewhere ahead, and a rushing and hissing of water as the craft that we had struck foundered under our forefoot, and the skipper’s voice again, cracked and hoarse, ordering the boats to be cleared away.”

O’Toole paused for a moment and gasped as if for breath; his soup lay neglected before him, his elbows were on the table, and his two hands locked together in a grip so tense that the knuckles shone white in the light that came streaming in through the scuttles in the ship’s side, his eyes were glassy and staring into vacancy with an intensity of gaze which plainly showed that the whole dreadful scene was again unfolding itself before his mental vision, and the perspiration was streaming down his forehead and cheeks. Then the table steward came up, and, removing his soup, asked him whether he would take cold beef, ham-and-tongue, or roast chicken. The sound of the man’s voice seemed to bring the dazed chief officer to himself again; he sighed heavily, and as though relieved to find himself where he was, considered for a moment, and, deciding in favour of cold beef, resumed his narrative.

“The next thing that I can remember, gentlemen,” he continued, “was that I was on the poop with the skipper, second and third mates, the carpenter, and a few others, lighting for our lives as we strove to keep back the frantic passengers and prevent them from interfering with the hands who were cutting the gripes and working furiously to sling the boats outboard. We carried four boats at the davits, two on each quarter, and those were all that were available, for the others were buried under the raffle and wreckage of the fallen masts, and it would have taken hours to clear them, with the probability that, when got at, they would have been found smashed to smithereens, while a blind man could have told by the feel of the ship that she was settling fast, and might sink under us at any moment. At last one of the boats was cleared and ready for lowering, and as many of the women and children as she would carry were bundled into her, the third mate, two able seamen, and myself being sent along with them by the skipper to take care of them. I would willingly have stayed behind, for there were other women and children—to say nothing of men passengers—to be saved, but I knew that a certain number of us Jacks must of necessity go in each boat to handle and navigate her, and there was no time to waste in arguing the matter; so in I tumbled, just as I was, and the next moment we were rising and falling in the water alongside, the tackle blocks were cleverly unhooked, and we out oars and shoved off, pulling to a safe distance and then lying on our oars to wait for the rest.

“I shall never, to my dying day, forget the look of that ship as we pulled away from her. The Joan had been as handsome a craft as ever left the stocks when we hauled out of dock at London some three weeks earlier; but now—her bows were crumpled in until she was as flat for’ard as the end of a sea-chest; her decks were lumbered high with the wreckage of her masts and spars; the standing and running rigging was hanging down over her sides in bights; and she had settled so low in the water that her channels were already buried; while her poop was crowded with madly struggling figures, from which arose a confused babel of sound—shouting, screaming, and cursing—than which I have never heard anything more awful in all my life.

“When we had pulled off about fifty fathoms the third mate, who was in charge of the boat, ordered us to lie upon our oars; and presently we saw that the second quarter-boat was being lowered. She reached the water all right, and then we heard the voice of the second mate yelling to the hands on deck to let run the after tackle. The next moment, as the sinking ship rolled heavily to starboard, we saw the stern of the lowered boat lifted high out of the water, the bow dipped under, and in a second, as it seemed, she had swamped, and the whole load of people, some twenty in number, were struggling and drowning alongside as they strove ineffectually to scramble back into the swamped boat, which had now by some chance become released from the tackle that had held her.

“For a moment we, in the boat that had got safely away, sat staring, dumb and paralysed with horror at the dreadful scene that was enacting before our eyes. But the next moment those of us who were at the oars started madly backing and pulling to swing the boat round and pull in to the help of the poor wretches who were perishing only a few fathoms away from us. We had hardly got the boat round, however, when Mr Gibson, the third mate, gave the order for us to hold water.

“‘We mustn’t do it,’ he said. ‘The boat is already loaded as deep as she will swim, and the weight of even one more person would suffice to swamp her! As it is, it will take us all our time, and tax our seamanship to the utmost, to keep her afloat; you can see for yourselves that it would be impossible for us to squeeze more than one additional person in among us, and, even if we had the room, we could not get that one in over the gunnel without swamping the craft. To attempt such a thing would therefore only be to throw away uselessly the lives of all of us; we must therefore stay where we are, and endure the awful sight as best we can—ah, there you have a hint of what will happen if we are not careful!’—as the boat, lying broadside-on to the sea, rolled heavily and shipped three or four bucketfuls of water—‘pull, starboard, and get her round stem-on to the sea; and you, O’Toole, get hold of the baler and dish that water out of her.’

“It was true, every word of it, as a child might have had sense to see. We could do absolutely nothing to help the poor wretches who were drowning there before our very eyes; and in a few minutes all was over, so far as they were concerned. Two or three men, I believe, managed to get back aboard the sinking ship by climbing up the davit tackles; but the rest quickly drowned—as likely as not because they clung to each other and pulled each other down.

“But the plight of those aboard the Joan was rapidly becoming desperate; and we could see that they knew it by observing the frantic efforts which they were making to get the other two boats into the water. We could distinctly hear the voice of the skipper rising from time to time above the clamour, urging the people to greater efforts, encouraging one, cautioning another, entreating the maddened passengers to keep back and give the crew room to work. Then, in the very midst of it all there came a dull boom as the decks blew up. We heard the loud hissing of the compressed air as it rushed out between the gaping deck planks; there arose just one awful wail—the sound of which will haunt me to my dying day—and with a long, sliding plunge the Joan lurched forward and dived, bows first, to the bottom.

“As for us, we could do nothing but just keep our boat head-on to the sea and let her drift, humouring and coaxing her as best we could when an extra heavy sea appeared bearing down upon us, and baling for dear life continuously to keep her free of the water that, in spite of us, persisted in slapping into her over the bows. The Canaries were the nearest bits of dry land to us, but Mr Jellicoe, the third mate, reckoned that they were a good hundred and fifty miles away, and dead to wind’ard; so it was useless for us to think of reaching them in a boat with her gunnels awash, and not a scrap of food or a drop of fresh water in her. The only thing that we could do was to exert our utmost endeavours to keep the craft afloat, and trust that Providence would send something along soon to pick us up. But—would you believe it?—although we were right in the track of the outward-bound ships, and although we sighted nine sailing craft and three steamers, nothing came near enough to see us, lying low in the water as we were, until the ninth day, when we were picked up by a barque bound for Cape Town. But by that time, gentlemen, Mr Jellicoe, one seaman, and I were all that remained alive of the boatload that shoved off from the stricken Joan of Arc on that fatal night. Don’t ask me by what means we contrived to keep the life in us for so long a time, for I won’t tell you. Thus you see that, of the complete complement of ninety-two persons who left London in the Joan of Arc, eighty-nine were drowned—to say nothing of those aboard the craft that we had run down—because the mate couldn’t—or wouldn’t—control his love of drink. Since that day, gentlemen, coffee is the strongest beverage that has ever passed my lips.”

“I am delighted to hear it,” remarked Firmin, “for observation has led me to the conviction that at least half the tragedies of human life have originated in the craving for intoxicants; and therefore,”—turning to Escombe—“I say again, my young friend, have absolutely nothing to do with them. I have no doubt that, ere you have been long in Peru, you will have made the discovery that it is a thirsty country; but, apart of course from pure water, there is nothing better for quenching one’s thirst than fresh, sound, perfectly ripe fruit, failing which, tea, hot or cold—the latter for preference—without milk, and with but a small quantity of sugar, will be found hard to beat. Now, if you are anxious for hints, there is one of absolutely priceless value for you; but I present it you free, gratis, and for nothing.”

“Thanks very much!” returned Harry. “I will bear it in mind and act upon it. No more intoxicants for me, thank you. Mr O’Toole, accept my thanks for telling us that terrible story of your shipwreck. It has brought home to me, as nothing else has ever done, the awful danger of tampering with so insidious an enemy as alcohol, which I now solemnly abjure for ever.”

Meanwhile, at the captain’s table, Mr Butler was expressing his opinion upon various subjects in loud, strident tones, and with a disputatiousness of manner that caused most of those about him mentally to dub him a blatant cad, and to resolve that they would have as little as possible to do with him.

One afternoon, when the Rimac had reached the other side of the Atlantic, Butler called Harry into the cabin of the former and said: “I understand that we shall be at Montevideo the day after to-morrow. Now I want you to understand that I shall expect you not to go on shore either at Montevideo or either of the other places that the Rimac will be stopping at. She will only remain at anchor at any of these places for a few hours; and if you were to go on shore it would be the easiest thing in the world for you to get lost and to miss your passage; therefore in order to obviate any such possibility I have decided not to allow you to leave the ship. Do you understand?”

“Yes,” answered Escombe, “I understand perfectly, Mr Butler, what you mean. But I certainly do not understand by what authority you attempt to interfere with my personal liberty to the extent of forbidding me to go on shore for a few hours when the opportunity presents itself. I agreed with Sir Philip Swinburne to accompany you to Peru as your assistant upon the survey which he has engaged you to make; and from the moment when that survey commences I will render you all the obedience and deference due to you as my superior, and will serve you to the best of my ability. But it was no part of my contract that I should surrender my liberty to you during the outward and homeward voyage; and when it comes to your forbidding me to leave the ship until our arrival at Callao, you must permit me to say that I feel under no obligation to defer to your wishes. And, quite apart from that, I may as well tell you that I have already accepted an invitation to accompany Mr and Mrs Westwood and a party ashore at Montevideo, and I see no reason why I should withdraw my acceptance.”

“W-h-a-t!” screamed Butler; “do I understand that you are daring to disobey and defy me?”

“Certainly not, sir,” answered Harry, “because, as I understand it, disobedience and defiance are impossible where no authority exists; and I beg to remind you that your authority over me begins only upon our arrival at Callao. Yet, purely as a matter of courtesy, I am of course not only prepared but perfectly willing to show all due deference to such reasonable wishes as you may choose to express. But I reserve to myself the right of determining where the line shall be drawn.”

“Very well, sir,” stuttered Butler, “I am glad to learn thus early what sort of behaviour I may expect from you. I shall write home at once to Sir Philip, reporting to him what has passed between us, and requesting him to send me out someone to take your place—someone who can be depended upon to render me implicit obedience at all times.” And therewith he whirled about and marched off to his own cabin, where, with the heat of his anger still upon him, he sat down and penned to Sir Philip Swinburne a very strong letter of complaint of what he was pleased to term young Escombe’s “insolently insubordinate language and behaviour”. As for Harry, Butler’s threat to report him to Sir Philip furnished him with a very valuable hint as to the wisest thing to do under the circumstances, and he too lost no time in addressing an epistle to Sir Philip, giving his own version of the affair. Thenceforward Butler pointedly ignored young Escombe’s existence for the remainder of the voyage; but by doing so he only made matters still more unpleasant for himself, for his altercation with Harry had been overheard by certain of the passengers, and by them repeated to the rest, with the final result that Butler was promptly consigned to Coventry, and left there by the whole of the saloon passengers.

Harry duly went ashore with his friends at Montevideo and—having first posted his letter to Sir Philip and another to his mother and sister—went out with them by train to Bellavista, where they all enjoyed vastly the little change from the monotony of life at sea, returning in the nick of time to witness a violent altercation between Butler and the boatman who brought him off from the shore. Also Harry went ashore for an hour or two at Punta Arenas, in the Straits of Magellan; and again at Valparaiso and Arica; finally arriving at Callao something over a month from the day upon which he sailed from London.

Chapter Three.

Butler the Tyrant.

At this point Escombe acknowledged himself to be legitimately under Butler’s rule and dominion, to obey unquestioningly all the latter’s orders, to go where bidden and to do whatever he might be told, even as did the soldiers of the Roman centurion; and Butler soon made him understand and feel that there was a heavy score to be wiped off—a big wound in the elder man’s self esteem to be healed. There were a thousand ways now in which Butler was able to make his power and authority over Harry felt; he was careful not to miss a single opportunity, and he spared the lad in nothing. He would not even permit Harry to land until the latter had personally supervised the disembarkation of every item of their somewhat extensive baggage; and when this was at length done he insisted that Escombe should in like manner oversee the loading of them into a railway wagon for Lima, make the journey thither in the same truck with them—ostensibly to ensure that nothing was stolen on the way—and finally, upon their arrival in Lima, he compelled Harry to remain by the truck and mount guard over it until it was coupled to the train for Palpa, and then to proceed to that town in the same truck without seeing anything more of the capital city than could be seen from the station yard. Then, again, at Palpa he insisted that Harry should remain by the truck and supervise the unloading of the baggage and its transference to a lock-up store, giving the lad to understand that he would be held responsible for any loss or damage that might occur during the operation; so that by the time that all this was done poor Escombe was more dead than alive, so utterly exhausted was he from long exposure to the enervating heat, and lack of proper food.

But Harry breathed no word of expostulation or complaint. He regarded everything that he now did as in the way of duty and merely as somewhat unpleasant incidents in the execution of the great task that lay before him, and he was content, if not quite as happy and comfortable as he might have been under a more congenial and considerate leader. Besides, he was learning something every minute of the day, learning how to do things and also how not to do them, for he very quickly recognised that although Butler might possibly be an excellent surveyor, he was but a very poor hand at organisation. Then, too, Butler had characteristically neglected the acquisition of any foreign language, consequently they had no sooner arrived at Palpa than he found himself absolutely dependent upon Harry’s knowledge of Spanish; and this advantage on Escombe’s part served in a great measure to place the two upon a somewhat more equal footing, and gradually to suppress those acts of petty tyranny which Butler had at first evinced a disposition to indulge in.

Palpa was the place at which their labours were to begin, and here it became necessary for them to engage a complete staff of assistants, comprising tent bearers, grooms, bush cutters, porters, cooks, and all the other attendants needed for their comfort and convenience during a long spell of camp life in a tropical climate, and in a country where civilisation is still elementary except in the more important centres. Luckily for them, the first section of their work comprised only a stretch of a little more than thirty miles of tolerably flat country, where no serious natural difficulties presented themselves, and that part of their work was soon accomplished. Yet Escombe found even this trifling bit of the great task before him sufficiently arduous; for Butler not only demanded that he should be up and at work in the open at daybreak, and that he should continue at work so long as daylight lasted, but that, when survey work was no longer possible because of the darkness, the lad should “plot” his day’s work on paper before retiring to rest. Thus it was generally close upon midnight before Escombe was at liberty to retire to his camp bed and seek his hard-earned and much-needed rest.

But it was when they got upon the second section of their work—between Huacho, Cochamarca, and Cerro de Pasco—that their real troubles and difficulties began, for here they had to find a practicable route up the face of the Western Cordillera in the first instance, and, having found it, to measure with the nicest accuracy not only the horizontal distances but the height of every rise and the depth of every declivity in the face of a country made up to a great extent of lofty precipices and fathomless ravines, the whole overgrown with dense vegetation through which survey lines had to be cut at enormous expense of time and labour. And here it was that Butler’s almost fiendish malice and ingenuity in the art of making things unpleasant for other people shone forth conspicuously. It was his habit to ride forth every morning accompanied by a strong band of attendants armed with axes and machetes, and well provided with ropes to assist in the scaling of precipitous slopes, for the purpose of selecting and marking out the day’s route, a task which could usually be accomplished in a couple of hours; and then to return and supervise the work of his subordinate, which he made as difficult and arduous as possible by insisting upon the securing of a vast amount of superfluous and wholly unnecessary information, in the obtaining of which Harry was obliged to risk his life at least a dozen times a day. Yet the lad never complained; indeed he could not have done so even had he been so disposed, for it was for Butler to determine what amount of information and of what nature was necessary for the proper execution of the survey; but Escombe began to understand now the means by which his superior had acquired the reputation of an accomplished surveyor. It is easy for a man in authority to stand or sit in safety and command another to perform a difficult task at the peril of his life!

And if Butler was tyrannically exacting in his treatment of Harry, he was still more so toward the unfortunate peons in his service, and especially those whom he detailed to accompany him daily to assist in the task of selecting and marking out the route of the survey line. These people knew no language but their own, and since Harry was always engaged elsewhere with theodolite, level, and chain, and was, therefore, not available to play the part of interpreter, it became necessary for Butler to secure the services of a man who understood enough English to translate his orders into the vernacular; and because this unfortunate fellow was necessarily always at Butler’s elbow, he became the scapegoat upon whose unhappy head the sins and shortcomings of the others were visited in the form of perpetual virulent abuse, until the man’s life positively became a burden to him, to such an extent, indeed, that he would undoubtedly have deserted but for the fact that Butler, suspecting his inclination perhaps, positively refused to pay him a farthing of wages until the conclusion of his engagement. It can easily be understood, therefore, that, under the circumstances described, an element of tragedy was steadily developing in the survey camp.

But although the overbearing and exacting behaviour of the chief of the expedition was thus making matters particularly unpleasant for everybody concerned, nothing of a really serious character occurred until the second section of the survey had been in progress for a little over two months, by which time the party had penetrated well into the mountain fastnesses, and were beginning to encounter some of the more formidable difficulties of their task. Butler was still limiting his share of the work to the mere marking out of the route, leaving Harry to perform the whole of the actual labour of the survey under his watchful eye, and stirring neither hand nor foot to assist the young fellow, although the occasions were frequent when, had he chosen to give a few minutes’ assistance at the theodolite or level, such help would have saved young Escombe some hours of arduous labour, and thus expedited the survey.

Now, it happened that a certain day’s work terminated at the edge of a quebrada, and Butler informed Harry that the first task of the latter, upon the following morning, would be to take a complete set of accurate measurements of this quebrada, before pushing on with the survey of the route. A quebrada, it may be explained, is a sort of rent or chasm in the mountain, usually with vertical, or at least precipitous sides, and very frequently of terrific depth, the impression suggested by its appearance being that at some period of the earth’s history the solid rock of the mountain had been riven asunder by some titanic force. Sometimes a quebrada is several hundreds of feet in width, and of a depth so appalling as to unnerve the most hardy mountaineer. The quebrada in question, however, was of comparatively insignificant dimensions, being only about forty feet wide at the point where the survey line crossed it, and some four hundred feet deep.

Now, although Harry was only an articled pupil, he knew quite enough about railway engineering to be perfectly well aware that the elaborate measurements which Butler had instructed him to take were absolutely unnecessary, the accurate determination of the width at the top—where a bridge would eventually have to be thrown across—being all that was really required. Yet he made no demur, for he had already seen that it would be possible to take as many measurements as might be required, with absolute accuracy and ease, by the execution of about a quarter of an hour’s preliminary surveying. But when, on the following morning, he commenced this bit of preliminary work, Butler rushed out of his tent and interrupted him.

“What are you doing?” he harshly demanded. “Have you forgotten that I ordered you to measure very carefully the quebrada this morning, before doing anything else?”

“No, sir,” answered Harry, “I have not forgotten. I am doing it now, or, rather, doing the necessary preliminary work.”

“Doing the necessary preliminary work?” echoed Butler. “What do you mean? I don’t understand you.”

“Then permit me to explain,” said Harry suavely. “I have ascertained that, by placing the theodolite over that peg yonder,”—pointing to a newly driven peg some four hundred feet away to the left—“I shall be able to get an uninterrupted view of the quebrada from top to bottom, and, by taking a series of vertical and horizontal angles from the top edge, can measure the contour of the two sides, at the point crossed by the survey line, with the nicest accuracy.”

“How do you mean?” demanded Butler.

Harry proceeded to elaborate his explanation, patiently describing each step of the intended operation, and making it perfectly clear that the elaborate series of unnecessary measurements demanded could be secured with the most beautiful precision.

“But,” objected Butler, “when you have taken all those angles you will have done only part of the work; you will still have to calculate the length of the vertical and horizontal lines subtended by them—”

“A matter of about half an hour’s work!” interjected Harry.

“Possibly,” agreed Butler. “But,” he continued, “I do not like your plan at all; I do not approve of it; it is amateurish and theoretical, and I won’t have it. A much simpler and more practical way will be for you to go down the quebrada at the end of a rope, measuring as you go.”

“That is one way certainly,” assented Harry; “but, with all submission, Mr Butler, I venture to think that it will not be nearly so accurate as mine. Besides, consider the danger. If the rope should happen to be cut in its passage over the sharp edge of that rock—”

“Look here,” interrupted Butler, “if you are afraid, you had better say so, and I will do the work myself. But I should like you to understand that timid people are of no use to me.”

The taunt was unjust, for Harry was not afraid; but he was convinced that his own plan was far and away the more expeditious and the more accurate, also it involved absolutely no danger at all; while it was patent to even the dullest comprehension that there was a distinct element of danger attaching to the other, inasmuch as that if anything should happen to the rope, the person suspended by it must inevitably be precipitated to the bottom, where a mountain stream roared as it leaped and boiled and foamed over a bed of enormous boulders.

Had Escombe been ten years older than he actually was he would probably not have hesitated—while disclaiming anything in the nature of cowardice—to express very strongly the opinion that where there were two methods of executing a certain task, one of them perfectly safe, and the other seriously imperilling a human life, it was the imperative duty of the person with whom the decision rested to select the safer method of the two, particularly when that method offered equally satisfactory results with the other. But, being merely a lad, and as yet scarcely certain of himself, remembering also that his future prospects were absolutely at Butler’s mercy, to make or mar as he pleased, Harry contented himself with a disclaimer of any such feeling as fear, and expressed his readiness to perform the task in any manner which Butler might choose to approve. At the same time he confessed his inability to understand precisely how the required measurements were to be taken, and requested instructions.

“Why,” explained Butler impatiently, “the thing is surely simple enough for a baby to understand. You will be lowered over the cliff edge and let down the cliff face exactly five feet at a time. As it happens to be absolutely calm, the rope by which you are to be lowered will hang accurately plumb; all that you will have to do, therefore, will be to measure the distance from your rope to the face of the rock, at every five feet of drop, and you will then have the particulars necessary to plot a contour of the cliff face, from top to bottom. You will do this on both sides of the quebrada, and then measure the width across at the top, which will enable us to produce a perfectly correct section of the gorge.”

“But how am I to measure the distance from the rope to the cliff face?” demanded Harry. “For, as you will have observed, sir, the rock overhangs at the top, and the gorge widens considerably as it descends.”

“You can do your measuring with a ranging-rod,” answered Butler tersely; “and if one is not long enough, tie two together.”

“Even so,” persisted Harry, “I fear I shall not be able to manage—”

“Will you, or will you not, do as you are told?” snapped Butler. “If you cannot manage with two rods, I will devise some other plan.”

“Very well, sir,” said Harry. “If you are quite determined to send me over the cliff, I am ready to go. What rope is it your pleasure that I shall use?”

“Take the tent ropes,” ordered Butler. “You will have an ample quantity if you join them all together. Make a seat for yourself in the end, and then mark off the rest of the rope into five-foot lengths, so that we may know exactly how much to pay out between the measurements. Then lash two ranging-rods together, and you will find that you will manage splendidly.”

Harry had his doubts, for to his own mind the tent ropes seemed none too strong for such a purpose. Moreover, the clips upon them would render the paying out over the cliff edge exceedingly awkward; still, since it seemed that the choice lay between risking his life and ruining his professional prospects, he chose the former, and set about making his preparations for what he could not help regarding as a distinctly hazardous experiment. These did not occupy him very long, and in about twenty minutes he was standing at the cliff edge, with a padded bight of the rope about his body, and the two joined ranging-rods in his hand, quite ready to be lowered down the face. Then two peons whom he had specially selected for the task, drew in the slack of the rope, passed a complete turn of it round an iron bar driven deep into a rock crevice, and waited for the command of a third who now laid himself prone on the ground, with his head projecting over the edge of the cliff, to watch and regulate the descent. Then Harry, fully realising, perhaps for the first time, the perilous nature of the enterprise, laid himself down and carefully lowered himself over the rocky edge.

“Lower gently, brothers!” ordered the man who was supervising the operation, and the rope was carefully eased away until the first five-foot mark reached the cliff edge, while Butler, who now also began at last to recognise and appreciate the ghastly peril to which his obstinacy had consigned a fellow creature, moved off to a point about a hundred yards distant, from which he could watch the entire descent. And he no sooner reached it than he perceived that Harry’s objections to the plan were well grounded, and that, even with the two joined rods, it would be impossible for the lad to take the required measurements over more than the first quarter of the depth. This being the case, it was obviously his duty at once to put a stop to so dangerous an attempt, especially as he knew perfectly well that it was as unnecessary as it was dangerous; but to do this would have been tantamount to confessing that he had made a mistake, and this his nature was too mean and petty to permit, so he simply sat down and watched in an ever-growing fever of anxiety lest anything untoward should happen for which he could be blamed.

Meanwhile, at the very first stoppage, Harry began to experience some of the difficulties that beset him in the task which he had undertaken. Despite the utmost care in lowering, the rope would persist in oscillating, very gently, it is true, but still sufficient to render it necessary to pause until the oscillation had ceased before attempting to take the measurement; also the torsion of the rope set up a slow revolving movement, so that, even when at length the oscillation ceased, it was only with difficulty that the correct measurement was taken and recorded in the book. This difficulty recurred as every additional five-foot length of rope was paid out, so that each measurement cost fully five minutes of precious time. Moreover, despite the padding of the rope, Harry soon began to find it cutting into his flesh so unpleasantly that he had grave doubts whether he would be able to endure it and hold out until the bottom, far below, should be reached.

At length, when about forty feet of rope had been very cautiously paid out, and some eight measurements taken, the peon who was superintending the operation of lowering was suddenly seen to stiffen his body, as though something out of the common had attracted his attention; he raised one hand as a sign to the other two to cease lowering, and gazed intently downward for several seconds. Then he signed for the lowering to be continued, and, to the astonishment of the others, wriggled himself back from the edge of the cliff until he had room to stand upright, when, scrambling hastily to his feet, he sprang to the two men who were lowering, and hissed between his set teeth:

“Lower! lower away as quickly and as steadily as you can, my brothers; the life of the young Señor depends upon your speed and steadiness. The rope has stranded—cut by the edge of the rock, most probably—and unless you can lower the muchacho to the bottom ere it parts altogether, he will be dashed to pieces!”

Meanwhile Harry, hanging there swinging and revolving in the bight of the rope, was not a little astonished when he found himself being lowered without pause, save such momentary jerks as were occasioned by the passage of the clips round the bar and over the cliff edge, and he instinctively glanced upward to see if he could discover what was wrong - for that something had gone amiss he felt tolerably certain. For a few seconds his eye sought vainly for an explanation, then his gaze was arrested by the sight of two severed ends of one strand of the rope standing out at a distance of about thirty feet above his head, and he knew!—knew that the strength of the slender rope had been decreased by one third, and that his life now depended upon the holding together of the two remaining strands!

Harry could see that those two remaining strands were stretched by his hanging weight to the utmost limit of their resistance, and he watched them with dull anxiety, as one in a dream, every moment expecting to see the yarns of which they were composed part one by one under the strain. And the worst of it was that that strain was not a steady one, otherwise there might be some hope that the strands would withstand it long enough to permit him to reach the bottom of the quebrada; but at frequent intervals there occurred a couple of jerks—one as a clip passed round the bar, and another as it slid over the cliff edge—and, of course, at every recurrence of the jerk the strain was momentarily increased to an enormous extent. And presently that which he feared happened, a more than usually severe jerk occurred, and one of the yarns in the remaining strands parted. Escombe dully wondered how far he still was from the bottom—a fearful distance, he believed—for he seemed to be cruelly close to the overhanging edge of the cliff, although he had been hanging suspended for a length of time that seemed to him more like hours than minutes. He did not dare to look down, for he had the feeling that if he removed his gaze from those straining and quivering strands for a single instant they would snap, and he would go plunging downward to destruction. Then, as he watched, another yarn parted, and another. A catastrophe was now inevitable, and the lad began to speculate curiously, and from a singularly impersonal point of view, what the sensation would be like when the last yarn had snapped. He had read somewhere that the sensation of falling from a great height was distinctly pleasurable; but what about the other, upon reaching the bottom? A quaint story came into his mind about an Irishman who was said to have fallen off the roof of a house, and who, upon being picked up, was asked whether he had been hurt by his fall, to which the man replied: “No, the fall didn’t hurt me a bit, it was stoppin’ so quick that did all the mischief!” The humour of the story was not very brilliant, yet somehow it seemed to Escombe at that moment to be ineffably amusing, and he laughed aloud at the quaintness of the conceit. And, as he did so, the remaining yarns of the second strand parted with a little jerk that thrilled him through and through, and he hung there suspended by a single strand, but still being lowered rapidly from above. His eyes were now fixed intently upon the unbroken strand, and he distinctly saw it stretching and straightening out under his weight, but, as it seemed to him, with inconceivable slowness. Then—to such a preternatural state of acuteness had his senses been wrought by the imminence and certainty of ghastly disaster—he saw the last strand slowly parting, not yarn by yarn but fibre by fibre, until, after what seemed to be a veritable eternity of suspense, the last fibre snapped, he heard a loud twang, and found himself floating—as it seemed to him—very gently downward, so gently, indeed, that, as he was swung round, facing the rocky wall, he was able to note clearly and distinctly every inequality, every projection, every crack, every indentation in the face of the rock; nay, he even felt that, were it worth while to do so, he would have had time enough to make sketches of every one of them as they drifted slowly upward. The next thing of which he was conscious was a loud swishing sound which rose even above the deafening brawl of water among rocks, that he now remembered with surprise had been thundering in his ears for—how many months—or years, was it? Then he became aware that he was somehow among leaves and branches; and again memory reproduced the scene upon which he had looked when, standing upon the cliff edge at a point from which he could command a view of the whole depth of the gorge, he had idly noted that, at the very bottom of it, a few inconsiderable shrubs or small trees, nourished by eternal showers of spray, grew here and there from interstices of the rock, and he realised that he had fallen into the heart of one of them. He contrived to grasp a fairly stout branch with each hand, and was much astonished when they bent and snapped like twigs as his body ploughed through the thick growth; but he knew that the force of his fall had been broken, and, for the first time since he had made the discovery of the severed strand, the hope came that, after all, he might emerge from this adventure with his life. Then he alighted—on his feet—on a great, moss-grown boulder, felt his legs double up and collapse under him, sank into a huddled heap upon the wet, slippery moss, shot off into the leaping, foaming water, and knew no more.

Chapter Four.

Mama Cachama.

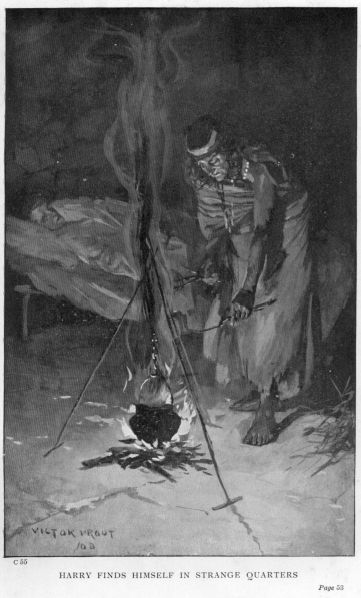

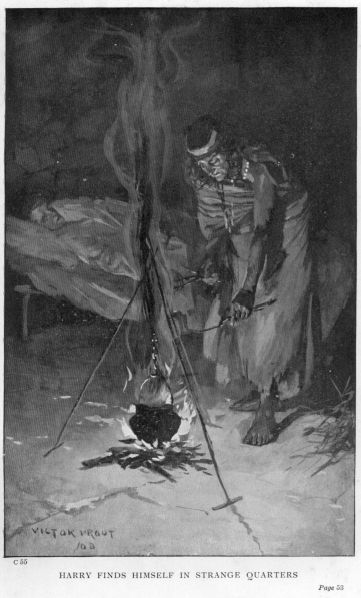

When young Escombe regained his senses it was night, or so he supposed, for all was darkness about him, save for such imperfect illumination as came from a small wood fire which flickered and crackled cheerfully in one corner of the apartment in which he found himself. The apartment! Nay, it was far too large, much too spacious in every dimension, to be a room in an ordinary house, and those walls—or as much as could be seen of them in the faint, ruddy glow of the firelight—were altogether too rough and rugged to have been fashioned by human hands, while the roof was so high that the flickering light of the flames was not strong enough to reach it. It was a cavern, without doubt, and Harry began to wonder vaguely by what means he had come there. For, upon awakening, his mind had been in a state of the most utter confusion, and it was not until he had lain patiently waiting for his ideas to arrange themselves, and had thereby come to the consciousness that he was aching in every bone and fibre of his body, while the latter was almost entirely swathed in bandages, that the recollection of his adventure returned to him. Even then the memory of it was but a dreamy one, and indeed he did not feel at all certain that the entire incident was not a dream from beginning to end, and that he should not presently awake to find himself on the cot in his tent, with the cold, clear dawn peering in past the unfolded flap, and another day’s arduous work before him. But he finally concluded that the fire upon which his eyes rested was too real, and, more especially, that his pain was too acute and insistent for him to be dreaming. Then he fell to wondering afresh how in the name of fortune he had found his unconscious way into that cave and upon the pallet which supported him.

The fire was the only thing in the cavern that was distinctly visible; certain objects there were here and there, a vague suggestion of which came and went with the rise and fall of the flame, but what they were Harry could not determine. There was, among other matters, an object on the far side of the fire, that looked not unlike a bundle of rags; but when Escombe, in attempting to turn himself over into a more comfortable position, uttered an involuntary groan as a sharp twinge of pain shot through his anatomy, the bundle stirred, and instantly resolved itself into the quaintest figure of a little, old, bowed Indian woman that it is possible to picture. But, notwithstanding her extreme age and apparent decrepitude, the extraordinary old creature displayed marvellous activity. In an instant she was on her feet and beside the pallet, peering eagerly and anxiously into Harry’s wide-open eyes. The result of her inspection appeared to be satisfactory, for presently she turned away and, muttering to herself in a tongue which was quite incomprehensible to her patient, disappeared in the all-enveloping darkness, only to reappear a moment later with a small cup in her hand containing a draught of very dark brown, almost black, liquid of an exceedingly pungent but rather agreeable bitter taste, which she placed to his lips, and  which the lad at once swallowed without demur. The effect of the draught was instantaneous, as it was marvellously stimulating and exhilarating; and it must also have possessed very remarkable tonic properties, for scarcely had Escombe swallowed it when a sensation of absolutely ravenous hunger assailed him.

which the lad at once swallowed without demur. The effect of the draught was instantaneous, as it was marvellously stimulating and exhilarating; and it must also have possessed very remarkable tonic properties, for scarcely had Escombe swallowed it when a sensation of absolutely ravenous hunger assailed him.

“Ah!” he sighed, “that was good; I feel ever so much better now. Mother,” he continued in Spanish, “I feel hungry: can you find me something to eat?”

“Aha! you feel hungry, do you?” responded the old woman in the same language. “Good! I am prepared for that. Wait but a moment, caro mio, until I can heat the broth, and your hunger shall soon be satisfied.” And with the birdlike briskness which characterised all her actions she moved away into the shadows, presently returning with three iron rods in her hand, which she dexterously arranged in the form of a tripod over the fire, and from which she suspended a small iron pot. Then, taking a few dry sticks from a bundle heaped up near the fire, she broke them into short lengths, which she carefully introduced, one by one, here and there, into the flame, coaxing it into a brisk blaze which soon caused a most savoury and appetising steam to rise from the pot. Next, from some hidden receptacle she produced a bowl and spoon, emptied the smoking contents of the pot into the former, and then, carefully propping her patient into a sitting position, proceeded to feed him. The stew was delicious, to such an extent, indeed, that Harry felt constrained to compliment his hostess upon its composition and to ask of what it was made. He was much astonished—and also, it must be confessed, a little disgusted—when the old lady simply answered, Lagarto (lizard). There was no doubt, however, that he had greatly enjoyed his meal, and felt distinctly the better for it; he therefore put his squeamishness on one side, and asked his companion to enlighten him as to the manner in which he came to be where he was.