Title: An Onlooker in France 1917-1919

Author: Sir William Orpen

Release date: December 29, 2006 [eBook #20215]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Geetu Melwani, Christine P. Travers, Chuck

Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian

Libraries)

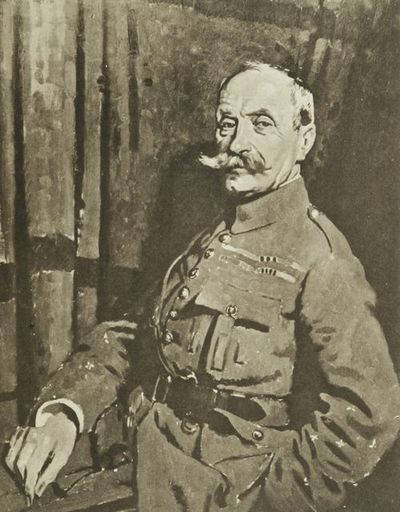

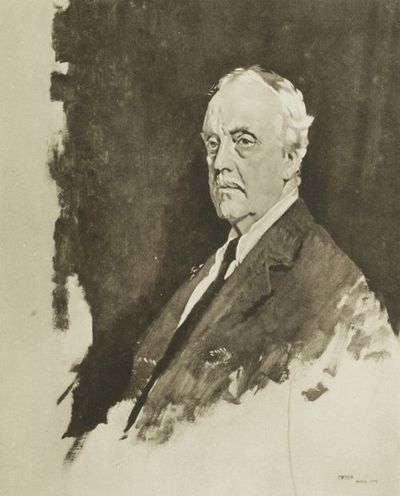

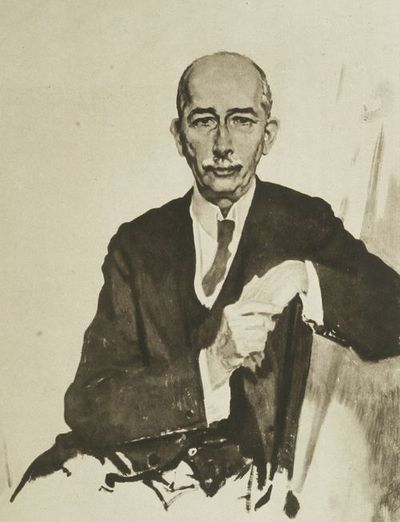

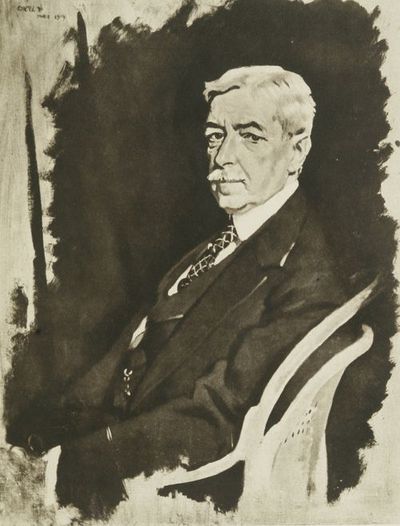

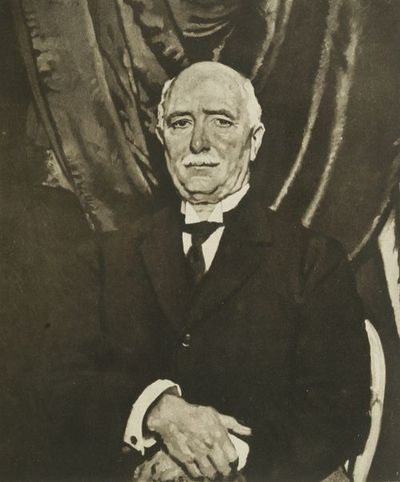

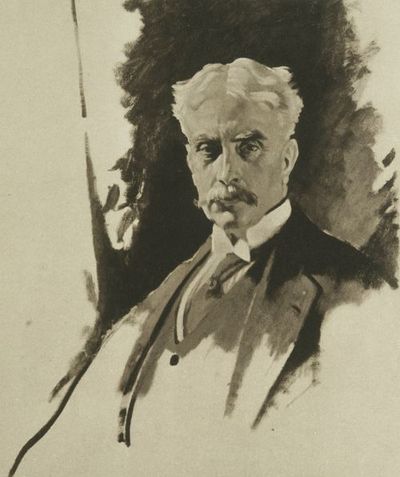

I. Field-Marshal Earl Haig of Bemersyde, O.M., K.T., etc.

This book must not be considered as a serious work on life in France behind the lines, it is merely an attempt to record some certain little incidents that occurred in my own life there.

The only thought I wish to convey is my sincere thanks for the wonderful opportunity that was given me to look on and see the fighting man, and to learn to revere and worship him—that is the only serious thing. I wish to express my worship and reverence to that gallant company, and to convey to those who are left my most sincere thanks for all their marvellous kindness to me, a mere looker on.

Chap.

PREFACE

I.

TO FRANCE (APRIL 1917)

II.

THE SOMME (APRIL 1917)

III.

AT BRIGADE HEADQUARTERS AND

ST. POL (MAY-JUNE 1917)

IV.

THE YPRES SALIENT (JUNE-JULY 1917)

V.

THE SOMME IN SUMMER-TIME (AUGUST 1917)

VI.

THE SOMME (SEPTEMBER 1917)

VII.

WITH THE FLYING CORPS (OCTOBER 1917)

VIII.

CASSEL AND IN HOSPITAL (NOVEMBER 1917)

IX.

WINTER (1917-1918)

X.

LONDON (MARCH-JUNE 1918)

XI.

BACK IN FRANCE (JULY-SEPTEMBER 1918)

XII.

AMIENS (OCTOBER 1918)

XIII.

NEARING THE END (OCTOBER 1918)

XIV.

THE PEACE CONFERENCE

XV.

PARIS DURING THE PEACE CONFERENCE

XVI.

THE SIGNING OF THE PEACE

INDEX

Plate

I.

Field-Marshal Earl Haig of Bemersyde, O.M., K.T., etc.

II.

The Bapaume Road.

III.

Men Resting, La Boisselle.

IV.

A Tank, Pozières.

V.

Warwickshires entering Péronne.

VI.

No Man's Land.

VII.

Three Weeks in France: Shell-shock.

VIII.

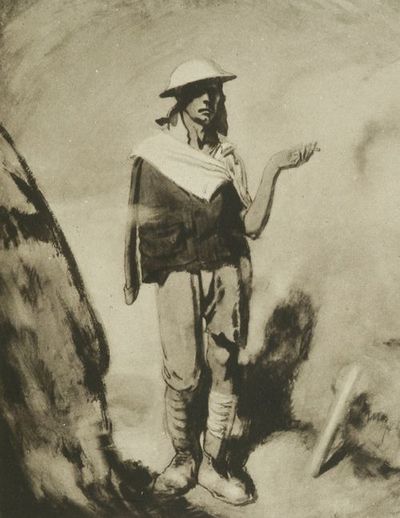

Man in the Glare, Two Miles from the Hindenburg Line.

IX.

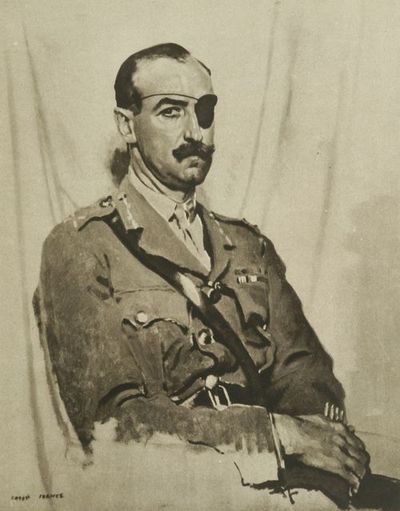

Air-Marshal Sir H. M. Trenchard, Bart., K.C.B., etc.

X.

A Howitzer in Action.

XI.

German 'Planes visiting Cassel.

XII.

Soldiers and Peasants, Cassel.

XIII.

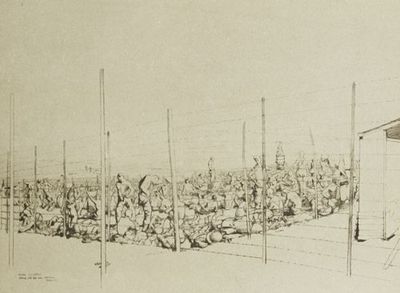

German Prisoners.

XIV.

View from the old English Trenches, looking towards

La Boisselle.

XV.

Adam and Eve at Péronne.

XVI.

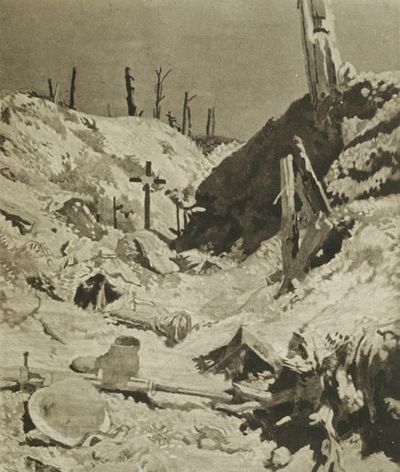

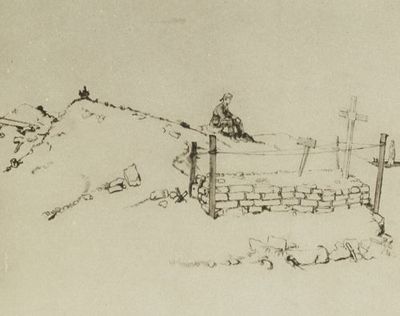

A Grave in a Trench.

XVII.

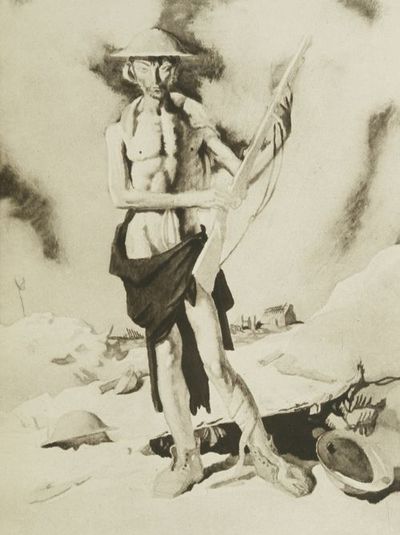

The Deserter.

XVIII.

The Great Mine, La Boisselle.

XIX.

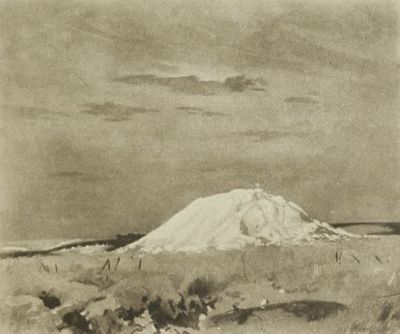

The Butte de Warlencourt.

XX.

Lieut. A. P. F. Rhys Davids, D.S.O., M.C., etc.

XXI.

Lieut. R. T. C. Hoidge, M.C.

XXII.

The Return of a Patrol.

XXIII.

Changing Billets.

XXIV.

The Receiving-room, 42nd Stationary Hospital.

XXV.

A Death among the Wounded in the Snow.

XXVI.

Some Members of the Allied Press Camp.

XXVII.

Poilu and Tommy.

XXVIII.

Major-General The Right Hon. J. E. B. Seely,

C.B., etc.

XXIX.

Bombing: Night.

XXX.

Major J. B. McCudden, V.C., D.S.O., etc.

XXXI.

The Refugee.

XXXII.

Lieut.-Col. A. N. Lee, D.S.O., etc.

XXXIII.

Marshal Foch, O.M.

XXXIV.

A German 'Plane passing St. Denis.

XXXV.

British and French A.P.M.'s, Amiens.

XXXVI.

General Lord Rawlinson, Bart., G.C.B., etc.

XXXVII.

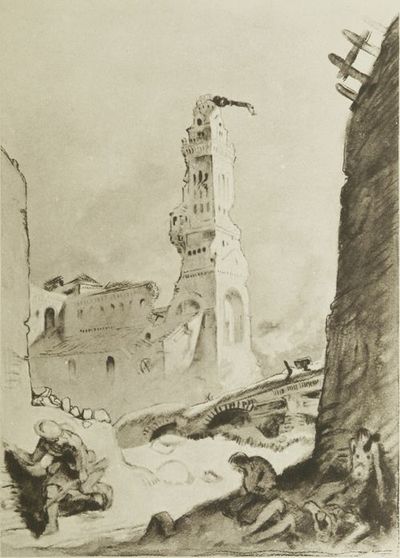

Albert.

XXXVIII.

The Mad Woman of Douai.

XXXIX.

Field-Marshal Lord Plumer of Messines, G.C.B., etc.

XL.

Armistice Night, Amiens.

XLI.

The Official Entry of the Kaiser.

XLII.

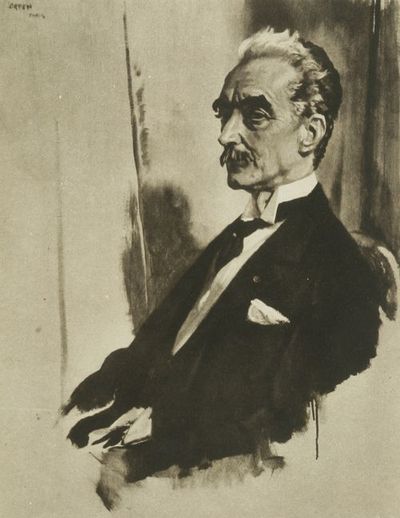

General Sir J. S. Cowans, G.C.B., etc.

XLIII.

Field-Marshal Sir Henry H. Wilson, Bart., K.C.B., etc.

XLIV.

The Right Hon. Louis Botha, P.C., LL.D.

XLV.

The Right Hon. A. J. Balfour, O.M.

XLVI.

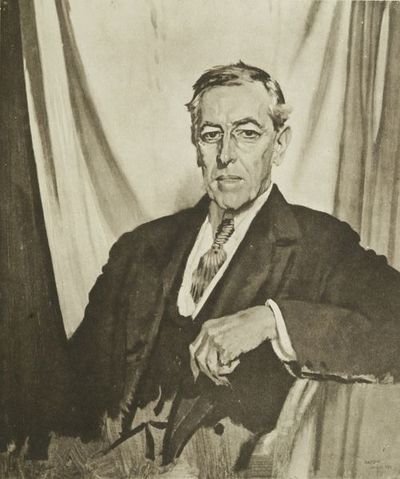

President Woodrow Wilson.

XLVII.

The Marquis Siongi.

XLVIII.

A Polish Messenger.

XLIX.

Lord Riddell.

L.

The Right Hon. The Earl of Derby, E.G., etc.

LI.

Signing the Peace Treaty.

LII.

The End of a Hero and a Tank, Courcelette.

LIII.

General Birdwood returning to his Headquarters, Grévillers.

LIV.

A Skeleton in a Trench.

LV.

Flight-Sergeant, R.F.C.

LVI.

N.C.O., Grenadier Guards.

LVII.

Stretcher-bearers.

LVIII.

Man Resting, near Arras.

LIX.

Going Home to be Married.

LX.

Household Brigade passing to the Ypres Salient. Cassel.

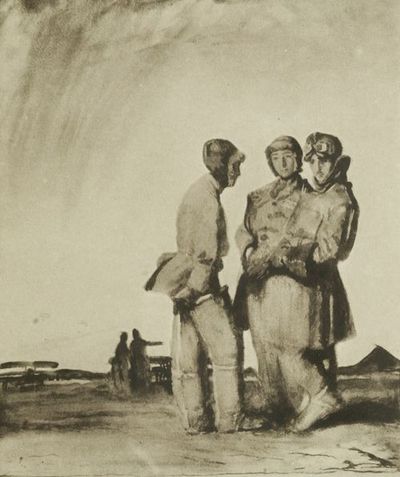

LXI.

Ready to Start.

LXII.

A German Prisoner with the Iron Cross.

LXIII.

A Big Gun and its Guardian.

LXIV.

Good-bye-ee.

LXV.

The Château, Thiepval.

LXVI.

German Wire, Thiepval.

LXVII.

Thiepval.

LXVIII.

Highlander passing a Grave.

LXIX.

M. R. D. de Maratrayl.

LXX.

A Man, Thinking, on the Butte de Warlencourt.

LXXI.

Major-General Sir Henry Burstall, K.C.B., etc.

LXXII.

Major-General L. J. Lipsett, C.M.G., etc.

LXXIII.

A Village, Evening (Monchy).

LXXIV.

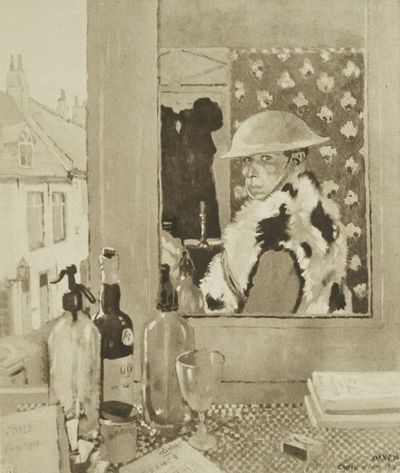

Christmas Night, Cassel.

LXXV.

Blown Up: Mad.

LXXVI.

A Support Trench.

LXXVII.

Major-General Sir H. J. Elles, K.C.M.G., etc.

LXXVIII.

Dead Germans in a Trench.

LXXIX.

A German Prisoner.

LXXX.

A Highlander Resting.

LXXXI.

Man with a Cigarette.

LXXXII.

Mr. Lloyd George, President Wilson, M. Clemenceau.

LXXXIII.

A Meeting of the Peace Conference.

LXXXIV.

Admiral of the Fleet Lord Wester Wemyss, G.C.B., etc.

LXXXV.

Colonel Edward M. House.

LXXXVI.

Mr. Robert Lansing.

LXXXVII.

The Emir Feisul.

LXXXVIII.

M. Eleutherios Venezelos.

LXXXIX.

Admiral of the Fleet Sir David Beatty, Viscount Borodale of

Wexford, O.M., G.C.B., etc.

XC.

The Right Hon. W. F. Massey, P.C.

XCI.

General The Right Hon. J. C. Smuts, P.C., C.H.

XCII.

The Right Hon. G. N. Barnes, P.C.

XCIII.

The Right Hon. W. M. Hughes, P.C., K.C.

XCIV.

Brigadier-General A. Carton de Wiart, K.C., C.B., etc.

XCV.

M. Paul Hymans.

XCVI.

The Right Hon. Sir Robert Borden, G.C.M.G., etc.

The boat was crowded. Khaki, everywhere khaki; lifebelts, rain and storm, everything soaked. Destroyers, churning through the waves, played strange games all round us. Some old-time Tommies, taking everything for granted, smoked and laughed and told funny stories. Others had the look of dumb animals in pain, going to what they knew only too well. The new hands for France asked many questions, pretended to laugh, pretended not to care, but for the most part were in terror of the unknown.

It was strange to watch this huddled heap of humanity, study their faces and realise that perhaps half of them would meet a bloody end before a new moon was over, and wonder how they could do it, why they did it—Patriotism? Yes, and perhaps it was the chance of getting home again when the war was over. Think of the life they would have! The old song:—

"We don't want to lose you,

But we think you ought to go,

For your King and your Country

Both need you so.

"We

(p. 012)

shall-want you and miss you,

But with all our might and main

We shall cheer you, thank you, kiss you,

When you come back again."

Did they think of that, and all the joys it seemed to promise them? I pray not.

What a change had come over the world for me since the day before! On that evening I had dined with friends who had laughed and talked small scandal about their friends. One, also, was rather upset because he had an appointment at 10.30 the next day—and there was I, a few hours later, being tossed about and soaked in company with men who knew they would run a big chance of never seeing England again, and were certainly going to suffer terrible hardships from cold, filth, discomfort and fatigue. There they stood, sat and lay—a mass of humanity which would be shortly bundled off the boat at Boulogne like so many animals, to wait in the rain, perhaps for hours, before being sent off again to whatever spot the unknown at G.H.Q. had allotted for them, to kill or to be killed; and there was I among them, going quietly to G.H.Q., everything arranged by the War Office, all in comfort. Yet my stomach was twitching about with nerves. What would I have been like had I been one of them?

At Boulogne we lunched at the "Mony" (my companion, Aikman, had been to France before during the war and knew a few things). It was an excellent lunch, and, as we were not to report at G.H.Q. till the next day, we walked about looking at lorries and trains, all going off to the unknown, filled with humanity in khaki weighed down with their packs.

II. The Bapaume Road.

The (p. 013) following morning at breakfast at the "Folkestone Hotel" we sat at the next table to a Major with red tabs. He did not speak to us, but after breakfast he said: "Is your name Orpen?" "Yes, sir," said I. "Have you got your car ready?" "Yes, sir," said I. "Well, you had better drive back with me. Pack all your things in your car." "Yes, sir," said I. He explained to me that he had come to Boulogne to fetch General Smuts' luggage, otherwise he gave us no idea of who or what he was, and off we drove to the C.-in-C.'s house, where he went in with the General's luggage and left us in the car for about an hour. Then we went on to Hesdin, where he reported us to the Town Major, who said he had found billets for us. The Red Tab Major departed, as he said he was only just in time for his lunch, and told us to come to Rollencourt soon and report to the Colonel. The Town Major brought us round to our billet—the most filthy, disgusting house in all Hesdin, and the owner, an old woman, cursed us soundly, hating the idea of people being billeted with her. Anyway, there he left us and went off to his "Mess."

This was all very depressing, so we talked together and went on a voyage of discovery and found an hotel; then we went back to the billet and said "good-bye" to Madame and moved our stuff there. But the hotel wasn't a dream—at least we had no chance of dreaming—bugs, lice and all sorts of little things were active all night. I had been told by the War Office to go slow and not try to hustle people, so we decided we would not go and report to the Colonel till the next day after lunch.

Looking into the yard from my window in the afternoon, I saw two men I knew, one an artist from Chelsea, the (p. 014) other a Dublin man, who used to play lawn tennis. They were "Graves." My Dublin friend was "Adjutant, Graves," in fact he proudly told me that "Adjutant, Graves, B.E.F., France," would always find him. We dined with them that night at H.Q. Graves. They were very friendly, and said we could travel all over the back of the line by going from one "Graves" to another "Graves." All good chaps, I'm sure, and cheerful, but we did not do it.

The next day after lunch we drove to Rollencourt, and found the Major in his office (a hut on the lawn in front of the château). He left, and returned to say the Colonel could not see us then. Would we come back at 5 p.m.? So off we went and sat by the side of the road for two hours. Then again to the Major's at 5 p.m., when he informed us the Colonel had gone out. Would we come back at 7 p.m.? (No tea offered.) This we did and waited until 7.50, when the Major informed us that the Colonel would not see us that evening, but we were to report the next morning at 9 a.m. (No dinner offered.) We left thinking very hard—things did not seem so simple after all. We reported at 9 a.m. and waited, and got a message at 11 a.m. that the Colonel would see us, and we were shown in to a wizened, sour-faced little man, his breast ablaze with strange colours. I explained to him that I did not like the billets at Hesdin, that Hesdin was too far away from anything near the front, and that I intended to go to Amiens at once. To my surprise he did not seem to object, and just as we were leaving, he said: "By the way, General Charteris wants you to go and see him this morning. You had better go at once." So that was it! If General Charteris had not sent that message I might not have been admitted to the presence (p. 015) of the Colonel for weeks. Off we went, full of hope, packed our bags and on to G.H.Q. proper, and got in to see the General at once—a bluff, jovial fellow who said: "You go anywhere you like, do anything you like, but don't ask me to get any Generals to sit to you; they're fed up with artists." I said: "That's the last thing I want." "Right," said he, "off you go." So we "offed" it to Amiens, arriving there about 7 p.m. on a cold, black, wet night. We went to see the Allied Press "Major," to find out some place to stop in, etc. Again we were rather depressed. The meeting was very chilly, the importance of the Major was great—the full weight and responsibility of the war seemed on him. "The Importance of being Ernest" wasn't in it with him. As I learnt afterwards, when he came in late for a meal all the other officers and Allied Press correspondents stood up. Many a time I got a black look for not doing so. However, he advised the worst and most expensive hotel in the town, and off we went (no dinner offered), rather depressed and sad.

III. Men resting. La Boisselle.

Amiens was the one big town that could be reached easily from the Somme front for dinner, so every night it was crowded with officers and men who had come back in cars, motor-bikes, lorries or any old thing in or on which they could get a lift. After dinner they would stand near the station and hail anything passing, till they found something that would drop them near their destination. As there was an endless stream of traffic going out over the Albert and Péronne Roads during that time (April 1917), it was easy.

Amiens is a dirty old town with its seven canals. The cathedral, belfry and the theatre are, of course, wonderful, but there is little else except the dirt.

I remember later lunching with John Sargent in Amiens, after which I asked him if he would like to see the front of the theatre. He said he would. When we were looking at it he said: "Yes, I suppose it is one of the most perfect things in Europe. I've had a photograph of it hanging over my bed for the last thirty years."

But Amiens was a danger trap for the young officer from the line, also for the men. "Charlie's Bar" was always full of officers; mirth ran high, also the bills for drinks—and the drink the Tommies got in the little cafés was terrible stuff, and often doped.

Then, when darkness came on, strange women—the riff-raff from (p. 017) Paris, the expelled from Rouen, in fact the badly diseased from all parts of France—hovered about in the blackness with their electric torches, and led the unknowing away to blackened side-streets and up dim stairways—to what? Anyway, for an hour or so they were out of the rain and mud, but afterwards? Often did I go with Freddie Fane, the A.P.M., to these dens of filth to drag fine men away from disease.

IV. A Tank. Pozières.

The wise ones dined well—if not too well—at the "Godbert," with its Madeleine, or the "Cathedral," with its Marguerite, who was the queen of the British Army in Picardy, or, not so expensively, at the "Hôtel de la Paix." Some months later the club started, a well-run place. I remember a Major who used to have his bath there once a week at 4 p.m. It was prepared for him, with a large whisky-and-soda by its side. What more comfort could one wish? Then there were dinners at the Allied Press, after which the Major would give a discourse amid heavy silence; then music. The favourite song at that time was:—

"Jackie Boy!

Master?

Singie well?

Very well.

Hey down,

Ho down,

Derry, Derry down,

All among the leaves so green, O.

"With my Hey down, down,

With my Ho down, down,

Hey down,

Ho down,

Derry, Derry down,

All among the leaves so green, O."

Later, (p. 018) perhaps, if the night was fine, the Major would retire to the garden and play the flute. This was a serious moment—a great hush was felt, nobody dared to move; but he really didn't play badly. And old Hale would tell stories which no one could understand, and de Maratray would play ping-pong with extraordinary agility. It would all have been great fun if people had not been killing each other so near. Why, during that time, the Boche did not bomb Amiens, I cannot understand, it was thick every week-end with the British Army. One could hardly jamb oneself through the crowd in the Place Gambetta or up the Rue des Trois Cailloux. It was a struggling mass of khaki, bumping over the uneven cobblestones. What streets they were! I remember walking back from dinner one night with a Major, the agricultural expert of the Somme, and he said, "Don't you think the pavement is very hostile to-night?"

I shall never forget my first sight of the Somme battlefields. It was snowing fast, but the ground was not covered, and there was this endless waste of mud, holes and water. Nothing but mud, water, crosses and broken Tanks; miles and miles of it, horrible and terrible, but with a noble dignity of its own, and, running through it, the great artery, the Albert-Bapaume Road, with its endless stream of men, guns, food lorries, mules and cars, all pressing along with apparently unceasing energy towards the front. Past all the little crosses where their comrades had fallen, nothing daunted, they pressed on towards the Hell that awaited them on the far side of Bapaume. The mud, the cold, the noise, the misery, and perhaps death;—on they went, plodding through the mud, those wonderful men, perhaps singing one of their cheer-making songs, such as:—

"I

(p. 019)

want to go home.

I want to go home.

I don't want to go to the trenches no more,

Where the Whizz-bangs and Johnsons do rattle and roar.

Take me right over the sea,

Where the Allemande can't bayonet me.

Oh, my!

I don't want to die,

I want to go home."

V. Warwickshires entering Péronne.

How did they do it? "I want to go home."—Does anyone realise what those words must have meant to them then? I believe I do now—a little bit. Even I, from my back, looking-on position, sometimes felt the terrible fear, the longing to get away. What must they have felt? "From battle, murder and sudden death, Good Lord, deliver us."

On up the hill past the mines to Pozières. An Army railway was then running through Pozières, and the station was marked by a big wooden sign painted black and white, like you see at any country station in England, with POZIÈRES in large Roman letters, but that's all there was of Pozières except a little red in the mud. I remember later, at the R.F.C. H.Q., Maurice Baring showed me a series of air-photographs of Pozières as it was in 1914, with its peaceful little streets and rows of trees. What a contrast to the Pozières as it was in 1917—MUD. Further on, the Butte stood out on the right, a heap of chalky mud, not a blade of grass round it then—nothing but mud, with a white cross on the top. On the left, the Crown Prince's dug-out and Gibraltar—I suppose these have gone now—and Le Sars and Grévillers, at that time General Birdwood's H.Q., where the church had been knocked into a fine shape. I tried to draw it, but was much put off by air fighting. It seemed a favourite spot for this.

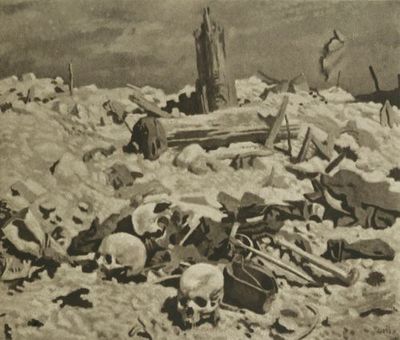

Bapaume (p. 020) must always have been a dismal place, like Albert, but Péronne must have been lovely, looking up from the water; and the main Place must have been most imposing, but then it was very sad. The Boche had only left it about three weeks, and it had not been "cleaned up." But the real terribleness of the Somme was not in the towns or on the roads. One felt it as one wandered over the old battlefields of La Boisselle, Courcelette, Thiepval, Grandcourt, Miraumont, Beaumont-Hamel, Bazentin-le-Grand and Bazentin-le-Petit—the whole country practically untouched since the great day when the Boche was pushed back and it was left in peace once more.

A hand lying on the duckboards; a Boche and a Highlander locked in a deadly embrace at the edge of Highwood; the "Cough-drop" with the stench coming from its watery bottom; the shell-holes with the shapes of bodies faintly showing through the putrid water—all these things made one think terribly of what human beings had been through, and were going through a bit further on, and would be going through for perhaps years more—who knew how many?

I remember an officer saying to me, "Paint the Somme? I could do it from memory—just a flat horizon-line and mud-holes and water, with the stumps of a few battered trees," but one could not paint the smell.

Early one morning in Amiens I got a message from Colonel John Buchan asking me to breakfast at the "Hôtel du Rhin." While we were having breakfast, there was a great noise outside—an English voice was cursing someone else hard and telling him to get on and not make an ass of himself. Then a Flying Pilot was pushed in by an Observer. The Pilot's hand and arm were temporarily bound up, but blood (p. 021) was dropping through. The Observer had his face badly scratched and one of his legs was not quite right. They sat at a table, and the waiter brought them eggs and coffee, which they took with relish, but the Pilot was constantly drooping towards his left, and the drooping always continued, till he went crack on the floor. Then the Observer would curse him soundly and put him back in his chair, where he would eat again till the next fall. When they had finished, the waiter put a cigarette in each of their mouths and lit them. After a few minutes four men walked in with two stretchers, put the two breakfasters on the stretchers, and walked out with them—not a word was spoken.

VI. No Man's Land.

I found out afterwards that the Pilot had been hit in the wrist over the lines early that morning and missed the direction back to his aerodrome. Getting very weak, he landed, not very well, outside Amiens. He got his wrist bound up and had asked someone to telephone to the aerodrome to tell them that they were going to the "Rhin" for breakfast, and would they send for them there?

After I had been in Amiens for about a fortnight, going out to the Somme battlefields early in the morning and coming back when it got dark, I received a message one evening from the Press "Major" to go to his château and ring up the "Colonel" at Rollencourt, which I did. The following was the conversation as far as I remember:—

"Is that Orpen?"

"Yes, sir."

"What do you mean by behaving this way?"

"What way, please, sir?"

"By not reporting to me."

"I'm (p. 022) sorry, sir, but I do not understand."

"Don't you know you must report to me, and show me what work you have been doing?"

"I've practically done nothing yet, sir."

"What have you been doing?"

"Looking round, sir."

"Are you aware you are being paid for your services?"

"Yes, sir."

"Well, report to me and show me your work regularly.—Tell the Major to speak to me."

The Major spoke, and I clearly heard him say my behaviour was damnable.

This wonderful Colonel expected me to work all day, and apparently, in the evening, to take what I had done and show it to him—the distance by motor to him and back was something like 110 miles!

I saw there was nothing for it, if I wanted to do my work, but to fight, so I decided to lay my views of people and things before those who were above the Colonel. This I did, and had comparative peace, but the seed of hostility was sown in the Colonel's Intelligence (F) Section, G.H.Q., as I think it was then called, and they made me suffer as much as was in their power.

A fair spring morning—not a living soul is near,

Far, far away there is the faint grumble of the guns;

The battle has passed long since—

All is Peace.

At times there is the faint drone of aeroplanes as

They pass overhead, amber specks, high up in the blue;

Occasionally there is the movement of a rat in the

Old battered trench on which I sit, still in the

Confusion in which it was hurriedly left.

The sun is baking hot.

Strange odours come from the door of a dug-out

With its endless steps running down into blackness.

The land is white—dazzling.

The distance is all shimmering in heat.

A few little spring flowers have forced their way

Through the chalk.

He lies a few yards in front of the trench.

We are quite alone.

He makes me feel very awed, very small, very ashamed.

He has been there a long, long time—

Hundreds of eyes have seen him,

Hundreds of bodies have felt faint and sick

Because of him.

Then this place was Hell,

But now all is Peace.

And the sun has made him Holy and Pure—

He and his garments are bleached white and clean.

A

(p. 024)

daffodil is by his head, and his curly, golden

Hair is moving in the slight breeze.

He, the man who died in "No Man's Land," doing

Some great act of bravery for his comrades and

Country—

Here he lies, Pure and Holy, his face upward turned;

No earth between him and his Maker.

I have no right to be so near.

VII. Three Weeks in France. Shell shock.

About this time Freddie Fane (Major Fane, A.P.M.) sent me up to his old division, which was then fighting in front of Péronne. We arrived on a lovely afternoon at Divisional H.Q., which were in a pretty fir-wood, and consisted of beautifully camouflaged little huts. The guns were booming a few miles off, but everything was very peaceful there, and the dinner was excellent; but, just as we finished, the first shell shrieked overhead, and this I was told afterwards went on all night. Personally I had another large whisky-and-soda, and slept like a log.

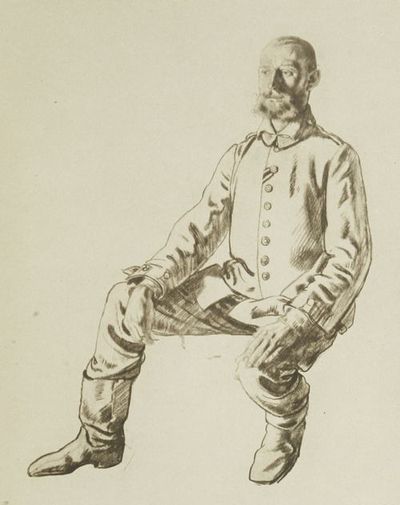

The next morning the General's A.D.C. motored me to a village about four kilometres off and handed me over to a 2nd Lieutenant, who walked me off to Brigade H.Q. These were behind an old railway embankment. Everyone was most kind, but I saw no quiet place to work. Everyone was rushing about, and the noise of the guns was terrific. The young 2nd Lieutenant advised me to take the men I wanted to draw and to go to the other side of the embankment. He said that there was no one there and that I could work in peace, and he was right. The noise from our batteries immediately gave me a bad headache, but apparently the Boche did not respond at all till the afternoon. Then they started, and the noise was HELL. Whenever there was a big bang I couldn't help giving (p. 026) a jump. The old Tommy I was drawing said, "It's all right, Guv'ner, you'll get used to it very soon." I didn't think so, but to make conversation I said: "How long is it since you were home?"

"Twenty-two months," said he.

"Twenty-two months!" said I.

"Yes," said he, "but one can't complain. That bloke over there hasn't been home for twenty-eight."

What a life! Twenty-four hours of it was enough for me at a time. Before evening came my head felt as if it were filled with pebbles which were rattling about inside it. After lunch I sat with the Brigadier for a time and watched the men coming out from the trenches. Some sick; some with trench feet; some on stretchers; some walking; worn, sad and dirty—all stumbling along in the glare. The General spoke to each as they passed. I noticed that their faces had no change of expression. Their eyes were wide open, the pupils very small, and their mouths always sagged a bit. They seemed like men in a dream, hardly realising where they were or what they were doing. They showed no sign of pleasure at the idea of leaving Hell for a bit. It was as if they had gone through so much that nothing mattered. I was glad when I was back at Divisional H.Q. that evening. We had difficulty on one part of the road, as a "Sausage" had been brought down across it.

Shortly afterwards I went to live at St. Pol, a dirty little town, but full of character. The hotel was filthy and the food impossible. We ate tinned tongue and bully-beef for the most part. Here I met Laboreur, a Frenchman, who was acting as interpreter—a very good artist. I think his etchings are as good as any line work the war has produced. A (p. 027) most amusing man. We had many happy dinners together at a little restaurant, where the old lady used to give us her bedroom as a private sitting-room dining-room. It was a bit stuffy, but the food was eatable.

VIII. Man in the Glare. Two miles from the Hindenburg Line.

One fine morning I got a message, "Would I ring up the P.S. of the C.-in-C. at once?" so I went to the Camp Commandant's office. No one was there except a corporal, so I asked him to get through to Sir Philip Sassoon, and said that I would wait outside till he did so. Presently he called me in, and Sassoon said I was to paint the Chief, and would I come to lunch the next day at Advanced H.Q., G.H.Q.? after which we talked and laughed a bit. When I hung up the receiver, I turned round, and there was a large A.S.C. Colonel glaring at me. I was so taken aback, as I had not heard him come in, that I didn't even salute him. He roared at me, "Are you an S.S.O.?" (Senior Supply Officer). "No," said I, "I'm a painter!" I never saw a man in such a fury in my life. I thought he was going to hit me. However, I made him understand in the end that I really was speaking the truth and in no way wanted to be cheeky.

I had lunch at Advanced G.H.Q. the next day. The C.-in-C. was very kind, and brought me into his room afterwards, and asked me if everything was going all right with me. I told him I had a few troubles and was not very popular with certain people. He said: "If you get any more letters that annoy you, send them to me and I'll answer them." I went back to St. Pol with my head in the air. A great weight seemed to have been lifted off me.

Sir Douglas was a strong man, a true Northerner, well inside himself—no pose. It seemed it would be impossible to upset him, impossible to make him show any strong feeling, and (p. 028) yet one felt he understood, knew all, and felt for all his men, and that he truly loved them; and I knew they loved him. Never once, all the time I was in France, did I hear a "Tommy" say one word against "'Aig." Whenever it became my honour to be allowed to visit him, I always left feeling happier—feeling more sure that the fighting men being killed were not dying for nothing. One felt he knew, and would never allow them to suffer and die except for final victory.

When I started painting him he said, "Why waste your time painting me? Go and paint the men. They're the fellows who are saving the world, and they're getting killed every day."

The second time I was there, just after lunch, the Chief had gone to his room, and several Generals, Colonel Fletcher, Sassoon and myself were standing in the hall, when suddenly a most violent explosion went off, all the windows came tumbling in, and there was great excitement, as they thought the Boche had spotted the Chiefs whereabouts. The explosions went on, and out came the Chief. He walked straight up to me, laid his hand on my shoulder and said: "That's the worst of having a fellow like you here, Major. I thought the Huns would spot it," and, having had his joke, went back to his work. He was a great man. It turned out to be a munition dump which had exploded near by, and the noise was deafening for about eight hours.

This was the time of the great fight round the chemical works at Rœux, and I was drawing the men as they came out for rest. They were mostly in a bad state, but some were quite calm. One, I remember, was quite happy. He had ten days' leave and was going back to some village near Manchester (p. 029) to be married. He showed me her photograph, a pretty girl. Perhaps he was killed afterwards.

IX. Air-Marshal Sir H. M. Trenchard, Bart., K.C.B., etc.

The view from Mont St. Eloy was fine, with the guns belching out flame on the plain in the midday sun.

One day I was painting the C.-in-C., and at lunch-time the news came in that General Trenchard was there. The C.-in-C. said: "Orpen must see 'Boom,' he's great," so I was taken off and we met him in the garden. A huge man with a little head and a great personality, proud of one thing only, that is, that he is a descendant of Jack Sheppard. With him, to my delight, was Maurice Baring (his A.D.C.). The General was told that I wanted to see the aerodromes, and Maurice shyly said: "May I take Orpen round, sir? I know him." Gee! How happy I was when the General said: "All right, you see to it, Baring."

I painted "Boom" a few days later in a beautiful château with the most wonderful old stables. They have all been burnt down since. "Boom" worked hard all the time I painted. A few days later Baring told me that he had spoken to "Boom" and told him how much I admired his head. "Boom" replied: "Damned if he showed it in his painting." And yet he was worshipped by all the flying boys.

About this time I had sent from England Maurice Baring's "In Memoriam" to Lord Lucas. It made a tremendous impression on me then, and still does. I think it is one of the greatest poems ever written, and by far the greatest work of art the war has produced.

Baring took me out for a great day round the aerodromes. We visited several and lunched with a Wing-Commander, Colonel Freeman, who was most kind, a great lover of books, a lot of which Maurice used to supply him with. After this, (p. 030) we visited a squadron where there was to be a test fight between a German Albatross, which had been captured intact, and one of our machines. The fight was a failure, however, as just after they got up something went wrong with the radiator of the Albatross; but later Captain Little did some wonderful stunts on a triplane. I also saw Robert Gregory there, but had no chance to speak to him. But I learnt that he was doing very well and was most popular in the squadron, and that he had painted some fine scenery for their theatre.

St. Pol possessed an open-air swimming-bath, a strange thing for St. Pol, but there it was—a fine large swimming-bath, full of warm water which came from some chemical works. I used to swim there every evening when I got back from work. The one thing that struck me at that time was the difference between nudity and uniform—while bathing one could look at and study all these fine lads, and I would think of one, "Gee! there's an aristocrat. What a figure! What refinement!" and of another, "What a badly-bred, vulgar, common brute!" Later they would both come out of their bathing-boxes, and the "brute" would be a smartly dressed officer carrying himself with ease and distinction, and the "aristocrat" would be an untidy, uncouth "Tommy" shambling along. Truly on sight one should never judge a man with his clothes on.

X. Howitzer in Action.

It was about this time we moved to Cassel. Nothing very interesting in the journey till one comes to Arques and St. Omer (at one time Lord French's G.H.Q.). The road from Arques to the station at the foot of Cassel Hill was always lined on each side by lorries, guns, pontoons and all manner of war material. A gloomy road, thick with mud for the most part, if not dust. It was always a pleasure to start climbing Cassel Hill, past the seven windmills and up to the little town perched on the summit.

Cassel is a picturesque little spot, with its glazed tiles and sprinkling of Spanish buildings, and the view from it is marvellous. On a clear day one could see practically the whole line from Nieuport to Armentières and the coast from Nieuport to Boulogne. At that time, the 2nd Army H.Q. were in the one-time casino, which was the summit of the town, and from its roof one got a clear view all round. Cassel was to the Ypres Salient what Amiens was to the Somme, and the little "Hôtel Sauvage" stood for the "Godbert," the "Cathedral" and "Charlie's Bar" all in one. The dining-room, with its long row of windows showing the wonderful view, like the Rubens landscape in the National Gallery, was packed every night for the most part with fighting boys from the Salient, who had come in for a couple of hours to eat, drink, play the piano and sing, forgetting their (p. 032) misery and discomfort for the moment. It was enormously interesting to watch and study what happened in that room. One saw gaiety, misery, fear, thoughtfulness and unthoughtfulness all mixed up like a kaleidoscope. It was a well-run, romantic little hotel, built round a small courtyard, which was always noisy with the tramp of cavalry horses and the rattle of harness. The hotel was managed by Madame Loorius and her two daughters, Suzanne and Blanche, who were known as "The Peaches."

Suzanne was undoubtedly the Queen of the Ypres Salient, as sure as Marguerite was that of the Somme. One look from the eyes of Suzanne, one smile, and these wonderful lads would go back to their gun-pits—or who knows where?—proud.

Suzanne wore an R.F.C. badge on her breast. She was engaged to be married to an R.F.C. officer at that time. Whether the marriage ever came off I know not. Certainly not before the end of the war, and now Madame is dead, and they have given up the "Sauvage," and are, as far as I am concerned, lost.

Here the Press used to come when any particular operation was going on in the North. In my mind now I can look clearly from my room across the courtyard and can see Beach Thomas by his open window, in his shirt-sleeves, writing like fury at some terrific tale for the Daily Mail. It seemed strange his writing this stuff, this mild-eyed, country-loving dreamer; but he knew his job.

Philip Gibbs was also there—despondent, gloomy, nervy, realising to the full the horror of the whole business; his face drawn very fine, and intense sadness in his very kind eyes; also Percival Phillips—that deep thinker on war, who probably (p. 033) knew more about it than all the rest of the correspondents put together.

XI. German 'Planes visiting Cassel.

The people of Cassel loved the Tommy, so the latter had a good time there.

One day I drew German prisoners at Bailleul. They had just been captured, 3,500 in one cage, all covered with lice—3,500 men, some nude, some half-nude, trying to clean the lice off themselves. It was a strange business. The Boche at the time were sending over Jack Johnsons at the station, and these men used to cheer as each shell shrieked overhead.

It was at Cassel I first began to realise how wonderful the women of the working class in France were, how absolutely different and infinitely superior they were to the same class at home; in fact no class in England corresponded to them at all. Clean, neat, prim women, working from early dawn till late at night, apparently with unceasing energy, they never seemed to tire and usually wore a smile.

I remember one girl, a widow; her name was Madame Blanche, who worked at the "Hôtel Sauvage." She was about twenty-two years of age, and she owned a house in Cassel. A few months before I arrived there her husband had contracted some sort of poisoning in the trenches and had been brought back to Cassel, where he died. Madame Blanche interested me; she was very slim and prim and neat and tightly laced. Her fair hair was always very carefully crimped. She looked like a girl out of a painting by Metsu or Van Meer. I could see her posing at a piano for either, calm, gentle and silent; and could imagine her in the midst of all the refined surroundings in which these artists would have painted her. But now her surroundings were khaki, and her background was the wonderful Flemish view from the windows—miles (p. 034) and miles of country, with the old sausage balloons floating sleepily in the distance.

I must have looked at Madame Blanche a lot—perhaps too much. I remember she used to smile at me; but that was as far as our friendship could get—smiles, as I only knew about ten words of French, and she less of English.

But one day she surprised me, and left me thinking and wondering more of the strange, unbelievable things that happen to one in this world.

It was after lunch one Sunday: I had just got back to my room to work when there was a knock on the door, and in walked Madame Blanche, who, after much trouble to us both, I gathered wished me to go for a walk with her. Impossible! I, a major, a Field Officer, to walk at large through the streets of Cassel, 2nd Army H.Q., with a serving-girl from the "Hôtel Sauvage"! I succeeded in explaining this after some time; and then, to my amazement, she broke down and wept. The convulsive sobbing continued, and I thought and wondered, and in the end decided that I was crazy to make a woman weep because I would not go for a walk with her. So I told her I would do so; and she dried her eyes and asked me to meet her in the hotel yard in ten minutes.

When I got down to the yard the rain was coming down in torrents, and there she was, dressed in her widow's weeds and holding in her arms a mass of flowers. Solemnly we went out into the streets. Not a civilian, not a soldier, not even a military policeman was to be seen. All other human beings had taken refuge from the deluge: we were quite alone. Right through the town we went and out to the little cemetery, into which she brought me and led to her husband's grave, on which she placed the mass of flowers, and then knelt in the mud (p. 035) and prayed for about half an hour in the pouring rain; after which we walked solemnly and silently back to the hotel, soaked through and through. It was a strange affair. I may be stupid, but I cannot yet see her reason for wishing to take me out in the wet.

XII. Soldiers and Peasants, Cassel.

After working up there for about six weeks I began to feel very tired, and thought I would go for a change; so I decided to run away and go and see some "Bases"—Dieppe, Le Havre and Rouen. The day after I reached Dieppe I received a telegram from the "Colonel": "When do you return?" to which I replied: "Return where, please?" to which apparently no reply could be made. But two days later I received a letter from him saying he was moving to another job, but would always remember the honour of his having had me working under him. This was a nasty one for me, and I had no answer to give. About the same time I received a telegram from Sir Philip Sassoon: "Where the devil are you? aaa Philip." Months later he sent me a great parcel of correspondence as to whether this telegram, sent by the P.S. of the C.-in-C., could be regarded as an official telegram, its language, etc. The minutes were signed by Lieutenants, Captains, Majors, Colonels, all up to the last one, which was signed by a General, and ran thus: "What the —— hell were you using this disgusting language for, Philip?"

After a week I went back to Cassel, packed up and went south to Amiens.

Never shall I forget my first sight of the Somme in summer-time. I had left it mud, nothing but water, shell-holes and mud—the most gloomy, dreary abomination of desolation the mind could imagine; and now, in the summer of 1917, no words could express the beauty of it. The dreary, dismal mud was baked white and pure—dazzling white. White daisies, red poppies and a blue flower, great masses of them, stretched for miles and miles. The sky a pure dark blue, and the whole air, up to a height of about forty feet, thick with white butterflies: your clothes were covered with butterflies. It was like an enchanted land; but in the place of fairies there were thousands of little white crosses, marked "Unknown British Soldier," for the most part. (Later, all these bodies were taken up and nearly all were identified and re-buried in Army cemeteries.) Through the masses of white butterflies, blue dragon-flies darted about; high up the larks sang; higher still the aeroplanes droned. Everything shimmered in the heat. Clothes, guns, all that had been left in confusion when the war passed on, had now been baked by the sun into one wonderful combination of colour—white, pale grey and pale gold. The only dark colours were the deep red bronze of the "wire" and one black cat which lived in a shelter in what once was the main street of Thiepval. It was strange, this black cat living there (p. 037) all alone. No humans, or those of her own species, lived within miles of her. It took me days to make friends and get her to come to me; and when at last I succeeded, the friendship did not last long. No matter where I worked round that district, the black cat of Thiepval would find me, and would approach silently, and would suddenly jump on my knees and dig all her long nails deeply into my flesh, with affection. I stood it for a little time, and then gave her a good smack, after which I never saw my little black friend again.

XIII. German Prisoners.

Thiepval Château, one of the largest in the north of France, was practically flattened. What little mound was left was covered with flowers. Some bricks had been collected from it and marked the grave of "An Unknown British Soldier." Even Albert, that deadly uninteresting little town, looked almost beautiful and cheerful. Flowers grew by the sides of the streets; roses were abundant in what were once back-gardens; a hut was up at the corner by the Cathedral and Daily Mails were sold there every evening at four o'clock, and the golden leaning Lady holding her Baby, looking down towards the street, gleamed in the sun on top of the Cathedral tower.

A family had come back from Corbie and re-started their restaurant—a father and three charming girls. They patched up the little house by the station and did a roaring trade, and some few other families came back. Once more a skirt could be seen, even a few silk stockings occasionally tripping about.

Péronne was now like a polished skeleton—very clean, but very brittle: a little breeze, and whole houses would tumble to bits. I started painting, one day, a little picture from the hall of the College for Young Ladies. When I went the next day I found my point of view had been raised several feet: the top walls (p. 038) had come down. But here again they had patched up a great big house as a club. It was airy, not intentionally so, but on a hot day it was ideal, with its view down over the Somme. Bully-beef pie, cheese and beer—if one could only have had French coffee instead of that terrible black mixture imported from England, things would have been more perfectly complete.

About August, a burial party worked round Thiepval. Lieutenant Clark was in charge of it, a sturdy little Scot. During the month or so they worked there, they dug up, identified and re-buried thousands of bodies. Some could not be identified, and what was found on these in the way of money, knives, etc., was considered fair spoil for the burial party.

Often, coming down Thiepval Hill in the evening, everything golden in the sunlight, one would come across a little group of men, sitting by the side of the battered Hill Road, counting out and dividing the spoils of the day. It was a sordid sight, but for a non-combatant job, to be a member of a burial party was certainly not a pleasant one, and I do not think anyone could grudge them whatever pennies they made, and most of them would have to go back in the trenches when their burial party disbanded.

Down in the Valley of the Ancre, just beside the Thiepval Hill Road, there was a great colony of Indians. They were all Catholics, and were headed by an old padre who had worked in India for forty-five years—a fine old fellow. He held wonderful services each Sunday afternoon on the side of the Hill in the open air; he had an altar put up with wonderful coloured draperies behind it, which hung from a structure about thirty feet high. In the mornings, it was a very beautiful (p. 039) sight to see these nut-brown men washing themselves and their bronze vessels among the reeds in the Ancre; one could hardly believe one was in France. And where was one? Surely in a place and seeing a life that never existed before, and never will again. The rapidity with which these Indians (they were a cleaning-up party) changed the whole face of Thiepval and that part of the Ancre Valley was incredible.

XIV. View from the Old English Trenches. Looking towards La Boisselle.

When working in the Valley of the Ancre region, coming home in the evening, we would bring the car down to the water near Aveluy. It is a long stretch of water, and the Tommies had put up a springboard. It was a joy to take off one's clothes in the car and jump into the cool water and watch all these wonderful young men stripping, diving, swimming, drying and dressing in the evening sun, all full of life and health. At one period, Joffroy, a very good French artist, who had lost a leg, right up to his trunk, early in the War, used to swim there with me. He had been a great athlete, and had a very strong arm-stroke, and possessed one of the most beautifully-developed bodies I have ever seen. One evening, after bathing, as we were driving back to Amiens in the car, he stretched out his arms and said, "Orpen, I feel like a young Greek god!" And, after a pause, added: "But only a fragment, you know, only a fragment." He was a great man, and could clamber over trenches with his wooden stump in a marvellous way.

I remember that summer a strange thing happened. One day I found, and started painting, the remains of a Britisher and a Boche—just skulls, bones, garments—up by the trenches at Thiepval. I was all alone. My faithful Howlett was about half a mile away with the car. When I had been working about a (p. 040) couple of hours I felt strange. I cannot say even now what I felt. Afraid? Of what? The sun shone fiercely. There was not a breath of air. Perhaps it was that—a touch of the sun. So I stopped painting and went and sat on the trunk of a blown-up tree close by, when suddenly I was thrown on the back of my head on the ground. My heavy easel was upset, and one of the skulls went through the canvas. I got up and thought a lot, but came to the conclusion I had better just go on working, which I did, and nothing further strange happened. That night I happened to meet Joffroy, and told him about these skulls, and how peculiar one was, as it had a division in the frontal bone (the Britisher's). He said he would like to go and make a study of it; so I brought him out the next morning to the place, I myself working that day in Thiepval Wood, about half a mile further up the hill. I left him, saying I would come back and bring him lunch from the car, as it was difficult for him to get about. When I did get back I found him lying down, not very near the place, saying he felt very ill and he thought it was the smell "from those remains." He had done no work, and refused even to try to eat till we got a long way away from the skulls. I explained to him that there was no smell, and he said, "But didn't you see one has an eye still?" But I knew that all four eyes had withered away months before. There must have been something strange about the place.

Most of these summer months John Masefield was working on the Somme battlefields. He preferred to work out there on the spot. He would get a lift out from Amiens in the morning on a motor or lorry, work all day by himself at some spot like La Boisselle, and walk back to the bridge at Albert and look out for a lift back to Amiens. If we worked out in this direction, on (p. 041) the way home our eye was always kept on the look-out for him; but really it never appeared to matter to him if he got back or not. I don't believe he minded where he was as long as he could ponder over things all alone.

XV. Adam and Eve at Péronne.

The small towns and villages in this part of the country, behind the old fighting line of 1916, were, for the most part, dirty and usually uninteresting; but once clear of them the plains of Picardy had much charm and beauty, great, undulating, rolling plains, cut into large chequers made by the different crops. When a hill became too steep to work on, it was cut into terraces, like one sees in many of the vineyards in the South; these often have great decorative charm. A fair country—I remember Joffroy sometimes used the word "graceful" regarding different views in those parts, and the word gives the impression well.

There is a beautiful valley on the left, as one goes from Amiens to Albert: one looked down into it from the road, a patchwork of greens, browns, greys and yellows. I remember John Masefield said one day it looked to him like a post-impressionist table-cloth; later, white zigzagging lines were cut all through it—trenches.

In the spring of 1917 it was strange motoring out from Amiens to Albert. Just beyond this valley everything changed. Suddenly one felt oneself in another world. Before this point one drove through ordinary natural country, with women and children and men working in the fields; cows, pigs, hens and all the usual farm belongings. Then, before one could say "Jack Robinson!" not another civilian, not another crop, nothing but a vast waste of land; no life, except Army life; nothing but devastation, desolation and khaki.

About this time I got a telegram from Lord Beaverbrook asking me to meet him the next morning at Hesdin (Canadian Representatives' H.Q.); so I left Amiens early, arriving at Hesdin about 11.45 a.m. There they handed me a letter from him explaining to me that something very important had happened, and that he had left for Cassel. Would I have some lunch and follow him there? I lunched alone at the H.Q. and started for Cassel, where I arrived about 2.30, and found a letter telling me that he found that the aerodrome from which he wanted to get the news he desired was not near Cassel, so he had left, but would I meet him at the "Hôtel du Louvre," Boulogne, at 4 p.m., as his boat left at 4.20? Away I went to Boulogne, and walked up and down outside the "Louvre." About ten minutes past four up breezed a car, and in it was a slim little man with an enormous head and two remarkable eyes. I saluted and tried to make military noises with my boots. Said he: "Are you Orpen?" "Yes, sir," said I. "Are you willing to work for the Canadians?" said he. "Certainly, sir," said I. "Well," said he, "that's all right. Jump in, and we'll go and have a drink." So down to the buffet we went, and we had a bottle of champagne in very quick time, and away he went on to the boat, without another word, smiling; and the smile continued till (p. 043) I lost sight of him round the corner of the jetty. A strange day: I wondered a lot on the way back to Amiens, where I arrived about 9.45. I never knew then what a good friend I had met.

XVI. A Grave in a Trench.

As before, in Cassel, I first began to realise how wonderful the workwomen of France were, so in Amiens I began to realise how different the young men of France were to what one was brought up at home to imagine. I had always been led to believe that an Englishman was a far finer example of the human race than a Frenchman; but it certainly is not so now. The young Frenchman is a keen, strong, hardy fellow, and his general level of physical development is very high.

I remember this was brought home to me by having baths at Amiens. There was one bathroom in the hotel, and it contained a bath, but no hot water ran into it. So I told my batman to get hot water brought there in the mornings. The bathroom was on the first floor of the hotel, across on the other side of the courtyard from where I slept. The assistant cook, a man six feet odd high, and weighing about thirteen stone, a merry, jovial great giant, used to heat water for me and put it into an enormous bronze tub, which held a whole bathful; and he and my batman used to carry this upstairs; but if I happened to come along at the same time, this great man used to bend down and pick me up with his free hand and set me on his shoulder, and so to the bathroom.

One morning, about a year later, he told me he was going to leave. I asked him if he had got the "sack," or if he were leaving of his own free will. "Neither," said he. "I'm called up; I'm of age." This great, enormous man had only (p. 044) then reached the age of seventeen years. It amazed me. I remember a sad thing happened. When he left I gave him fifty francs and one hundred "Gold Flake" cigarettes. He had to go through Paris to get to his regiment, and when he arrived at the Gare du Nord they searched him, and found the cigarettes, took them from him, and fined him two hundred and fifty francs. It was a sad gift.

About this time I painted de Maratray—philosopher, musician, correspondent and clown.

Fane had gone, and Captain Maude was A.P.M. Amiens. Maude was a good A.P.M. His police were well looked after and adored him. He never wanted an officer or man from the trenches to get into trouble, but did his best to get them out of it when they were in it. Often have I been sitting at dinner with him at the "Hôtel de la Paix" and one of his police would come in and say, "A young officer is at the 'Godbert,' sir. He's had too much to drink, and is behaving very badly." Maude would curse loudly at his dinner being spoilt, but would always leave at once, and would calm down whatever young firebrand it was, find out where he had to go, and have him seen off by lorry or train to his destination. All this meant much more trouble for Maude than to have him arrested, and much less trouble for the culprit; but he always put them on their honour never to do it again; and many are the letters I have seen thanking him for being "a sport," and promising never "to do it again"; and asking would he dine with them the next time they got a night off? That was Maude's idea: he could not do too much for the men from the trenches, and they appreciated it. Maude was loved all through the North of (p. 045) France, except by a few rival A.P.M.'s. One could easily judge what his character was like from his favourite song:—

"Mulligatawny soup,

A mackerel or a sole,

A Banbury and a Bath bun,

And a tuppenny sausage roll.

A little glass of sherry,

Just a tiny touch of cham,

A roly-poly pudding

And Jam! Jam!! JAM!!!"

XVII. The Deserter.

A lot of nice people used to come to Amiens at that period; Colonel Woodcock and Colonel Belfield, the "Spot King," and Ernest Courage, "Jorrocks," in particular. It all became one large party at night for dinner. Maude was very popular with all the French officials, and great goodwill existed between the French and the British, and Marcelle's black eyes smiled at us from behind the desk, with its books, fruit, cheese and bottles; smiled so well that had she been different she might have out-pointed Marguerite as "Queen of the British Troops in Picardy." But no, her book-keeping and an occasional smile were enough for Marcelle, and she did them both exceedingly well.

Poor Marcelle! Afterwards I was told that when the Huns began to bomb Amiens badly she completely broke down and cried and sobbed at her desk. She was sent away down South, to Bordeaux, I think, and we never saw her again. It was sad. She was a sweet child, with her great dark eyes, and the little curl on her forehead, and her keen sense of the ridiculous.

The song of that time was:—

"Dear face that holds so sweet a smile for me.

Were it not mine, how 'Blotto' I should be."

But (p. 046) one night Carroll Carstairs of the Grenadier Guards breezed into Amiens, bringing with him a new American song which became very popular. The chorus ran something like this:—

"When Uncle Sam comes

He brings his Infantry;

He brings Artillery;

He brings his Cavalry.

Then, by God, we'll all go to Germany!

God help Kaiser Bill!

God help Kaiser Bill!

God help Kaiser Bill!

"For when Uncle Sam comes...." (Repeat)

One day Maude asked me to go to the belfry, the old sixteenth-century prison of Amiens, a beautiful building outside, but inside it was very black and awe-inspiring. The cells, away up in the tower, with their stone beds and straw, rats and smaller animals, made one's flesh creep. I am sorry I never painted the old fat lady who kept the keys in the entrance hall, a black place, lit by an oil lamp which hung over the stone fireplace. I put off painting her and her hall then for some reason, and later she was killed by a shell at the door during the bombardment. Here in the belfry the deserters were put, in an endeavour to make them say who they were, and Maude asked me to go this day because he had an interesting case.

A young man in a captain's tunic had been found in a brothel, and his papers were very incomplete. He had no leave warrant. They found he had been living at the "Hôtel de la Paix" for about a week. He had come to Amiens on a motor-bicycle, which he left in the street. They telephoned to the "Captain's" regiment and found the "Captain" was with his (p. 047) unit, but a tunic had been stolen from him at Calais. They also found a motor-bicycle had been stolen from Calais, and that it corresponded in number with the one found in the street.

XVIII. The Great Mine. La Boisselle.

We were given a candle, and climbed the black stairs to his cell. The youth was in a bad state, sobbing. Maude told him how sorry he was for him, and asked him not to be a fool, but to tell him the truth, and he would have him out of that place at once. He agreed, and told a long story, or rather—another long story. This was his third day and his third story, and it turned out there was not a word of truth in this one either.

He was one of the best-looking young men I ever saw, tall, clean-cut and smart-looking. The next day Maude found out that most of his tears were due to the fact that he was very badly diseased, and of course, without any treatment, was getting worse daily. Maude could not stand this, so he sent him to the hospital for treatment, from which the youth promptly escaped, and was not found again for ten days. They knew some one must have been hiding him, probably a woman; which proved right. In ten days he was found, plus forty pounds, which the lady had given him.

Maude gave him one more twenty-four hours' chance in the belfry; but it was no good, only more lies. So he was sent to Le Havre, where I believe no deserter has ever lasted more than forty-eight hours without telling the truth and nothing but the truth. I presumed that after that he was shot. The only thing I learnt for certain, was that he was a Colonial private. Some time later I used to go very often to a little restaurant in Paris, and became friends with one of the head waiters. He said a customer had come in, giving the name of Lord X——, and had engaged a table for dinner. He evidently had some doubt about Lord X——, and asked me if I would know (p. 048) him if I saw him. I said, "Certainly," as the name given was that of the son of one of the best-known Earls in England. In he came for dinner, a very good-looking man, wearing the Légion d'Honneur. Lord X——, the deserter of the belfry!

The great mine at La Boisselle was a wonderful sight. One morning I was wandering about the old battlefield, and I came across a great wilderness of white chalk—not a tuft of grass, not a flower, nothing but blazing chalk; apparently a hill of chalk dotted thickly all over with bits of shrapnel. I walked up it, and suddenly found myself on the lip of the crater. I felt myself in another world. This enormous hole, 320 yards round at the top, with sides so steep one could not climb down them, was the vast, terrific work of man. Imagine burrowing all that way down in the belly of the earth, with Hell going on overhead, burrowing and listening till they got right under the German trenches—hundreds and hundreds of yards of burrowing. And here remained the result of their work, on the earth at least, if not on humanity. The latter had disappeared; but the great chasm, with one mound in the centre at the bottom, and one skull placed on top of it, remained. They had cut little steps down one of its sides, and had cleared up all the human remains and buried them in this mound. That one mound, with the little skull on the top, at the bottom of this enormous chasm, was the greatest monument I have ever seen to the handiwork of man.

There was another fairly large mine here, just by the Bapaume Road, and there was a large mine at Beaumont-Hamel, and also the "Cough-drop" at High Wood. These were wonderful, but they could not compare in dignity and grandeur with the great mine of La Boisselle.

XIX. The Butte de Warlencourt.

Working (p. 049) out on the Somme, in the evenings as the sun was going down, one heard constantly a drone of aeroplanes, which quickly grew louder and louder, and before one could think, two of these great birds would pass just over one's head, quite close to the ground. A couple of minutes later, Bang! bang! bang! bang! and the boom and crash of the guns. Presently you would see the two birds, high up, returning to their aerodrome. They had gone up to the Boche trenches, in the eye of the sun, machine-gunning them and dropping small bombs.

The Butte de Warlencourt looked very beautiful in the afternoon light that summer. Pale gold against the eastern sky, with the mangled remains of trees and houses, which was once Le Sars, on its left. But what must it have looked like when the Somme was covered with snow, and the white-garmented Tommies used to raid it at night? It must surely have been a ghostly sight then, in the winter of 1916.

About this time I went to Paris several week-ends at odd times and painted for the Canadians Generals Burstall, Watson and Lipsett, also Major O'Connor. Poor Lipsett was killed by a shell later. He was a thoughtful, clever, quiet man, and was greatly respected. Burstall was a great, bluff, big, hearty fellow, and Watson was a fine chap, a real "sport." O'Connor was A.D.C. to General Currie, and had been twice wounded.

Paris! What a city!

"Paree!

That's the place for me.

Just across the sea

From Dover!"

About this time, the C.-in-C. was granted the Order of a Knighthood of the Thistle. It was given to him by the King during his visit to France in a château at Cassel. No one was present when he received this honour. Just afterwards I did a little interior of the room.

General Trenchard and Maurice Baring chose out two flying boys for me to paint, and they sat to me at Cassel. One was 2nd Lieutenant A. P. Rhys Davids, D.S.O., M.C., a great youth. He had brought down a lot of Germans, including two cracks, Schaffer and Voss. The first time I saw him was at the aerodrome at Estre Blanche. I watched him land in his machine, just back from over the lines. Out he got, stuck his hands in his pockets, and laughed and talked about the flight with Hoidge and others of the patrol, and his Major, Bloomfield. A fine lad, Rhys Davids, with a far-seeing, clear eye. He hated fighting, hated flying, loved books and was terribly anxious for the war to be over, so that he could get to Oxford. He had been captain of Eton the year before, so he was an all-round chap, and must have been a magnificent pilot. The 56th Squadron was very sad when he was reported missing, and refused to believe for one moment that he had been killed till they got the certain news. It was a great loss.

The other airman chosen was Captain Hoidge, M.C. and Bar—"George" (p. 051) of Toronto. Hoidge had also brought down a lot of Germans. His face was wonderfully fitted for a man-bird. His eyes were bird's eyes. A good lad was Hoidge, and I became very fond of him afterwards. I arranged with Maurice Baring and Major Bloomfield that Hoidge was to come to Cassel one morning at 11 a.m. to sit to me. The morning arrived and 11 o'clock and no Hoidge. Eleven-thirty, 12—no Hoidge. About 12:30 he strolled into the yard and I heard him asking for me in a slow voice. I was raging with anger by this time. He came upstairs and I told him there was no use doing anything before lunch, and that we had better go down and get some food. We ate silently. I could see he was rather depressed. About halfway through our meal, he said: "I'm lucky to be here with you this morning!" "Why?" said I. "Oh," he said, "I made a damned fool of myself this morning. Let an old Boche get on my tail. Damned fool I was—with my experience. Never saw the blighter. I was following an old two-seater at the time. He put a bullet through the box by my head, and cut two of my stays. If old B. hadn't happened to come up and chased him off I was for it. Damned fool! But the morning wasn't wasted, afterwards I got two two-seaters." I said: "Do you realise you have killed four men this morning?" "No," he said, "but I winged two damned nice birds." Then we went upstairs and he sat like a lamb.

XX. Lieut. A. P. F. Rhys Davids, D.S.O., M.C.

One evening, during the King's stay at Cassel, I was working in my room about 7 o'clock, when a little scrap of paper was brought me on which was written, "I am dining downstairs.—M. B." I went downstairs and there was Maurice Baring, and, with luck for me, alone. We had a great dinner. He was in his best form; for after dinner we went up to my room (p. 052) and sat by the open window and talked and talked. Suddenly Maurice stopped, and said: "What's that noise?" "What noise?" said I. So we looked down into the courtyard—only about ten feet—and there was "Boom," who had been dining with the King, and Philip Sassoon. "What the devil are you two doing?" said "Boom." "We've both been shouting ourselves hoarse for ten minutes. It's the last damned time you dine with Orpen, Maurice!" It's true we never heard them—but then Maurice was talking.

One morning, when the wind was very fresh, I got a telephone message from Major Bloomfield telling me to come to the squadron at once and see some "crashes." It was a glorious morning, blue sky, with great white clouds sailing by. I got down to the squadron as quickly as I could. A whole lot of novices from England had been sent out on trials, and the Major expected "great fun" when they landed.

The fire was made big and a great line of blue smoke whirled down the aerodrome to give the direction of the wind. Presently they began to come back. Some landed beautifully—one in particular—and the Major said to me: "Come on, I must go and congratulate that chap," and started running for the machine. When we got closer, he stopped and said: "Damn it! it's Hoidge, I forgot he was out."

I remember one poor chap in particular. He circled the aerodrome twelve times, each time coming down for a landing and each time funking it at the last moment. At last he did land, two or three bumps, and then—apparently slowly—the machine's nose went to the ground and gracefully it turned turtle. "Come along," said the Major, and when we got to the machine the wretched pilot was getting out from under it. "You unspeakable creature," said the Major. "Don't let me see (p. 053) your face again for twenty-four hours." And away limped the "unspeakable creature," covered with oil and dirt. I must add that after lunch the Major went up to him and patted his back and said he hoped he felt none the worse. But the thing that amazed me was, that although the machine seemed to land so gently, the damage to it was terrific—propeller and all sorts of strong things smashed to bits.

XXI. Lieut. R. T. C. Hoidge, M.C.

Ping-pong was the great game at this squadron (56th), and I used to play with a lot of them, including Hoidge and McCudden, but I did not know the latter's name at that time. It was before he became famous.

One day I went there with Maurice Baring, and the Major was greatly excited because they had just finished making a little circular saw to cut firewood for the squadron for the winter. The Major had a great idea that, as the A.D.C. to "Boom" was lunching, after lunch there would be an "official" opening of the circular saw. It was agreed that all officers and men were to attend (no flying was possible that day) and that Maurice should make a speech, after which he was to cut the end of a cigar with the saw, then a box was made with a glass front in which the cigar was to be placed after the A.D.C. had smoked a little of it, and the box was to be hung in the mess of the squadron. It was all a great success. Maurice made a splendid speech. We all cheered, and then the cigar was cut (to bits nearly). Maurice smoked a little, and it was put safely in its box. Then Maurice was given the first log to cut. This was done, but Maurice was now worked up, so he took his cap off and cut this in halves. He was then proceeding to take off his tunic for the same purpose, but was carried away from the scene of execution by a cheering crowd. It was a great day. I remember Maurice saw me back to Cassel about 1 a.m., (p. 054) after much ping-pong and music. "I'll go back to the shack where the black-eyed Susans," etc., was the song of the moment then in the squadron.

Shortly after this Major Bloomfield was ordered home, promoted and, I think, sent to America. At this loss, a great gloom fell over the 56th Squadron. I never saw any squadron in France that was run nearly so well as the 56th under Bloomfield, nor any Major loved more by his boys.

XXII. The Return of a Patrol.

About this time I went to Paris and met several Generals and Mr. Andrew Weir (now Lord Inverforth), and it was arranged that Aikman was to go home to the War Office and that I, perhaps, might have my brother out later to look after me. Aikman left, and I was very lonely. A better-hearted companion and a kinder man one could not meet, and regarding the intricacies of "King's Regulations" and such-like things, he was a past master.

After this, whenever I went to Paris, the great thing was to stop on the way at Clermont and lunch with "Hunchie." "Hunchie" kept the buffet at the station. He had a broken back and had been a chemist in Paris, but said he had come to the station at Clermont for excitement. It was so exciting that Maude proposed stopping there for a rest cure! But "Hunchie's" lunches were excellent. I remember one day on my way to Paris, I asked him at lunch if he had any Worcestershire Sauce; he had not. He asked me when I was coming back North again. I said the next day, which I did, and stopped for lunch. He had the sauce. He had been to Paris to get it. "Hunchie" was a wonder, so was Madame, and so was their dog "Black."

One spot in Paris, the Gare du Nord, will always mean a lot to the British Army on the Western Front. What sights one saw there!—masses of humanity, mostly British officers and men, (p. 056) each with their little "movement order": there they were in the heart of the Gay City. Yet that little slip of paper would, in a couple of hours, send them to Amiens, and a little later they would be at the front suffering Hell. Laboreur did a wonderful etching of an officer bidding farewell to his wife at the Gare du Nord. It gave the whole tragedy of the place—the blackness, smoke, smell and crush. There, any night during an air raid, one could not help thinking what would happen if the Boche got a bomb on the Gare, with its thousands of fighting men all jambed together under its glass roof in the semi-darkness. What a slaughter! And yet through it all, if the old Gare could only speak, it could tell some strange and amusing tales of that time—tales that would make one laugh, but with the laughter there would be a catch in the throat and a swimming in the eyes. It is extraordinary how funny sometimes the most tragic things can be.

The weather had become very bad and cold, and I worked on all impossible out-of-door days in my room in the "Hôtel de la Paix," which was known as the "Bar." My only rule was that the "Bar" was not open till 6.30 p.m. At times it nearly rivalled "Charlie's Bar." At what hour the "Bar" closed I was not always certain, as, no matter who was there, at about 10:30 I used to undress and go to bed, and so accustomed did I get to the clink of glasses and the squirt of the syphons that I slept calmly through it all. Among the regular attendants when in Amiens were Captain Maude, "Major" Hogg, Colonel MacDowall of the 42nd G.H., Colonel Woodcock, Colonel Belfield (the Spot King), Captain Ernest Courage (Jorrocks), Captains Hale and Inge (then of the Press), Bedelo (Italian correspondent), and Captain Brickman—a merry lot, taking them all round, and that room heard some good stories; some (p. 057) may have been not quite nice, but none were as dirty or disreputable as the room itself, with its smell of mud, paint, drink, smoke, and the fumes from the famous "Flamme Bleue" stove. The last man to leave the bar had to open the window. This was a firm rule. It sometimes took the last man a long time to do it, but it was always done.

XXIII. Changing Billets.

By this period of the war nearly every French girl could speak some English, and great was their anger if one could not understand them. I remember a very nice girl, who worked at the "Hôtel de la Paix," came to me one day and said solemnly, "My grandfadder he kill him." "Gracious!" I said, "whom did he kill?" "He kill him," was the furious reply. Apparently the poor grandfather, living under German rule at Landrecies, had committed suicide.

I went back to Cassel and began to itch, mildly at first, and I was not in the least put out. My brother came to France, and I went to Boulogne to meet him. His boat was to arrive at 6.15 p.m., but did not get in till just 10 p.m. They had been away down the Channel avoiding something. Driving back to Cassel we had a fine sight of bombing and searchlights. Hardly a night passed at this period that the Boche did not have a "go" at St. Omer. One night, just then, they dropped three torpedoes in Cassel as we were having dinner, but Suzanne, the "Peach," at her desk, never fluttered an eyelid. I believe afterwards, during the summer of 1918, when things were quite nasty at Cassel, she never showed any signs of being nervous: just sat at her desk, made out the bills, and occasionally made some lad happy by a look and a smile.

On some evenings we used to give great entertainments in the kitchen of the "Sauvage." I would stand the drinks, and Howlett (my chauffeur) played the mouth-organ, and Green (my batman) (p. 058) step-danced. It was an amusing sight watching the expressions of those old, fat Flemish workwomen of the hotel.