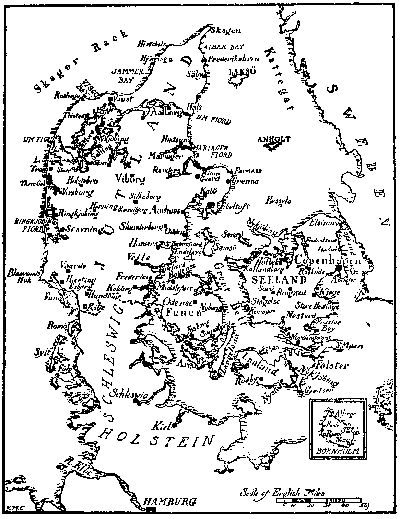

SKETCH-MAP OF DENMARK.

SKETCH-MAP OF DENMARK.

Title: Denmark

Author: M. Pearson Thomson

Release date: December 13, 2006 [eBook #20107]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Ralph Janke, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Ralph Janke,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net/)

[TN1] The section of the book about Norway is not included.

AND

WITH SIXTEEN FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR

64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York

1921

Copenhagen, the metropolis of Denmark, is a large and flourishing city, with all the modern improvements of a commercial capital. It has an atmosphere of its own, an atmosphere of friendliness and gaiety, particularly appreciated by English people, who in "Merry Copenhagen" always feel themselves at home.

The approach to this fine city from the North by the Cattegat is very charming. Sailing through the Sound, you come upon this "Athens of the North" at its most impressive point, where the narrow stretch of water which divides Sweden and Denmark lies like a silvery blue ribbon between the two countries, joining the Cattegat to the Baltic Sea. In summer the sparkling, blue Sound, of which the Danes are so justly proud, is alive with traffic of all kinds. Hundreds of steamers pass to and from the North Sea and Baltic, carrying their passengers and freights from Russia, Germany, Finland, and Sweden, to the whole world. In olden times Denmark exacted toll from these passing ships, which the nations found irksome, but the Danes most profitable. This "Sundtold" was abolished finally at the wish of the different nations using this "King's highway," who combined to pay a large lump sum to Denmark, in order that their ships might sail through the Sound without this annoyance in future.

Kronborg Castle, whose salute demanded this toll in olden days, still rears its stately pinnacles against the blue sky, and looking towards the old fortress of Kjärnan, on the Swedish coast, seems to say, "Our glory is of a bygone day, and in the land of memories."

Elsinore, the ancient town which surrounds this castle, is well known to English and American tourists as the supposed burial-place of Hamlet, the Prince of Denmark immortalized by Shakespeare. Kronborg Castle is interesting to us, in addition, as being the place where Anne of Denmark was married by proxy to James I. of England. Here, also, the "Queen of Tears," Caroline Matilda, sister of George III., spent some unhappy months in prison, gazing sadly over the Sound, waiting for the English ships to come and deliver her.

We pass up the Sound viewing the luxuriant cool green beech-woods of Denmark, and the pretty fishing villages lying in the foreground. Villas with charming gardens—their tiny rickety landing-stages, bathing sheds, and tethered boats, adding fascination to the homely scene—seem to welcome us to this land of fairy tales and the home of Hans Andersen.

The many towers and pinnacles of Copenhagen, with the golden dome of the Marble Church, flash a welcome as we steam into the magnificent harbour of this singularly well-favoured city. Here she stands, this "Queen of the North," as a gracious sentinel bowing acquiescence to the passing ships as they glide in and out of the Baltic. The broad quays are splendidly built, lined with fine warehouses, and present a busy scene of commercial activity. The warships lying at their moorings in the Sound denote that this is the station of the fleet; here also we see the country's only fortress—the formidable bulwarks which surround the harbour.

Kjöbenhavn in Danish means "merchants' harbour," and as early as the eleventh century it was a trading centre for foreign merchants attracted by the rich supply of herrings found by the Danish fishermen in the Baltic. Bishop Absalon was the founder of the city. This warrior Bishop strongly fortified the place, in 1167, on receiving the little settlement from King Valdemar the Great, and had plenty to do to hold it, as it was continually harassed by pirates and the Wends. These, however, found the Bishop more than a match for them. His outposts would cry, "The Wends are coming!" and the Bishop would leave his preaching, his bed, or anything else he might be doing, gather his forces together, and fight gallantly for his little stronghold. He perhaps recognized that this might one day be the key to the Baltic, which it has since become.

This city, therefore, is not a new one, but bombardment and conflagrations are responsible for its modern appearance. Fortunately, some of the handsome edifices raised during the reign of Christian IV. (1588-1648) still remain to adorn the city. This monarch was a great architect, sailor, warrior, and King, and is one of the most striking figures in Danish history. He was beloved by his people, and did much for his kingdom. The buildings planned and erected during this monarch's reign are worthy of our admiration. The beautiful Exchange, with its curious tower formed by four dragons standing on their heads, and entwining their tails into a dainty spire; Rosenborg Castle, with its delicate pinnacles; the famous "Runde Taarn" (Round Tower), up whose celebrated spiral causeway Peter the Great is said to have driven a carriage and pair, are amongst the most noteworthy. The originality in design of the spires and towers of Copenhagen is quite remarkable. Vor Frelsers Kirke, or Church of Our Saviour, has an outside staircase, running round the outside of its spire, which leads up to a figure of our Saviour, and from this height you get a fine view of the city. The tower of the fire-station, in which the fire-hose hangs at full length; the copper-sheathed clock and bell tower—the highest in Denmark—of the Town Hall; the Eiffel-like tower of the Zoo, are among the most singular. In all these towers there is a beautiful blending of copper and gold, which gives a distinctive and attractive character to the city. Other prominent features are the pretty fish-scale tiling, and the copper and bronze roofs of many of the buildings, with their "stepped" gables. Charming, too, are the city's many squares and public gardens, canals with many-masted ships making an unusual spectacle in the streets. But, after all, it is perhaps the innate gaiety of the Copenhagener which impresses you most. You feel, indeed, that these kindly Danes are a little too content for national development; but their light-hearted way of viewing life makes them very pleasant friends, and their hospitality is one of their chief characteristics. Every lady at the head of a Danish household is an excellent cook and manager, as well as being an agreeable and intelligent companion. The Copenhagener is a "flat" dweller, and the dining-room is the largest and most important room in every home. The Dane thinks much of his dinner, and dinner-parties are the principal form of entertainment. They joke about their appreciation of the good things of the table, and say, "a turkey is not a good table-bird, as it is a little too much for one Dane, but not enough for two!" A very pleasant side of Copenhagen life has sprung up from this appreciation, for the restaurants and cafés are numerous, and cater well for their customers. While the Dane eats he must have music, which, like the food, must be good; he is very critical, and a good judge of both. This gay café and restaurant life is one of the fascinations of Denmark's "too-large heart," as this pleasant capital is called by its people.

The climate of Copenhagen is delightful in summer, but quite the reverse in winter. Andersen says "the north-east wind and the sunbeams fought over the 'infant Copenhagen,' consequently the wind and the 'mud-king' reign in winter, the sunbeams in summer, and the latter bring forgetfulness of winter's hardships." Certainly, when the summer comes, the sunshine reigns supreme, and makes Copenhagen bright and pleasant for its citizens. Then the many water-ways and canals, running up from the sea as they do into the heart of the city, make it delightfully refreshing on a hot day. Nyhavn, for instance, which opens out of the Kongen's Nytorv—the fashionable centre of the town—is one of the quaintest of water-streets. The cobbled way on either side of the water, the curious little shops with sailors' and ships' wares, old gabled houses, fishing and cargo boats with their forests of masts, the little puffing motor-boats plying to and fro—all serve to make a distinctive picture. On another canal-side the fish-market is held every morning. A Danish fish-market is not a bit like other fish-markets, for the Dane must buy his fish alive, and the canal makes this possible. The fishing-smacks line up the whole side of the quay; these have perforated wooden boat-shaped tanks dragging behind them containing the lively fish. The market-women sit on the quay, surrounded by wooden tubs, which are half-filled with water, containing the unfortunate fish. A trestle-table, on which the fish are killed and cleaned, completes the equipment of the fish-wives. The customers scrutinize the contents of the tub, choose a fish as best they can from the leaping, gasping multitude, and its fate is sealed. When the market-women require more fish, the perforated tank is raised from the canal, and the fish extracted with a landing-net and deposited in their tubs. Small fish only can be kept alive in tanks and tubs; the larger kinds, such as cod, are killed and sold in the ordinary way. This market is not at all a pleasant sight, so it is better to turn our backs on it, and pass on to the fragrant flower-market.

Here the famous Amager women expose their merchandise. This market square is a gay spectacle, for the Dane is fond of flowers, and the Amager wife knows how to display her bright blooms to advantage. These vendors are notable characters. They are the descendants of the Dutch gardeners brought over by Christian II. to grow fruit and vegetables for Copenhagen, and settled on the fertile island of Amager which abuts on the city. Every morning these Amager peasants may be seen driving their laden carts across the bridge which joins their island to the mainland. These genial, stout, but sometimes testy Amager wives have it all their own way in the market-place, and are clever in attracting and befooling a customer. So it has become a saying, if you look sceptical about what you are told, the "story-teller" will say, "Ask Amager mother!" which means, "Believe as much as you like." These women still wear their quaint costume: bulky petticoats, clean checked apron, shoulder-shawl, and poke-bonnets with white kerchief over them; and the merry twinkle of satisfaction in the old face when a good bargain has been completed against the customer's inclination is quite amusing. These interesting old characters are easily irritated, and this the little Copenhageners know full well. When stalls are being packed for departure, a naughty band of urchins will appear round the corner and call out:

|

"Amager mother, Amager mo'er, Give us carrots from your store; You are so stout and roundabout, Please tell us if you find the door Too small to let you through!" |

The Amager wife's wrath is soon roused, and she is often foolish enough to try and move her bulky proportions somewhat quicker than usual in order to catch the boys. This of course she never manages to do, for they dart away in all directions. By this means the Amager woman gets a little much-needed exercise, the boys a great deal of amusement.

Sunday is a fête-day in Copenhagen, and the Dane feels no obligation to attend a Church service before starting out on his Sunday expedition. A day of leisure means a day of pleasure to the Copenhagener. The State helps and encourages him by having cheap fares, and good but inexpensive performances at the theatre and places of entertainment on Sunday. Even the poorest people manage to spare money for this periodical outing, mother and children taking their full share in the simple pleasures of the day. The Copenhagener looks forward to this weekly entertainment, and longs for the fresh air. This is not surprising, for many homes are stuffy, ventilation and open windows not seeming a necessity. A fine summer Sunday morning sees a leisurely stream of people—the Danes never hurry themselves—making for tram, train, or motor-boat, which will carry them off to the beautiful woods and shores lying beyond the city. Basking in the sunshine, or enjoying a stroll through the woods, feasting on the contents of their picnic baskets, with a cup of coffee or glass of pilsener at a café where music is always going on, they spend a thoroughly happy day. In the evening the tired but still joyous throng return home, all the better for the simple and pleasant outing. No country uses the bicycle more than Denmark, and Sunday is the day when it is used most. For the people who prefer to take their dinner at home on Sunday there is the pleasant stroll along the celebrated Langelinie. This famous promenade, made upon the old ramparts, overlooks the Sound with its innumerable yachts skimming over the blue water, and is a delightful place for pedestrians. A walk round the moat of the Citadel, on the waters of which the children sail their little boats, is also enjoyable. This Citadel, now used as barracks, was built by Frederik III. in 1663, and formerly served as a political prison. Struensee, the notorious Prime Minister, was imprisoned here and beheaded for treason. A few narrow, picturesque streets surrounding this fort are all that remain of old Copenhagen.

The art treasures contained in the museums of Copenhagen being renowned, I must tell you a little about them. Two or three of the palaces not now required by the Royal Family are used to store some of these treasures. Rosenborg Castle, built by Christian IV., and in which he died, contains a collection of family treasures belonging to the Oldenburg dynasty. This historical collection of these art-loving Kings is always open to the public. Besides Thorvaldsen's Museum, which contains the greater portion of his works, there is the Carlsberg Glyptotek, which contains the most beautiful sculpture of the French School outside France. The Danish Folk-Museum is another interesting collection. This illustrates the life and customs of citizens and peasants from the seventeenth century to the present day, partly by single objects, and partly by representations of their dwellings. The "Kunstmusæet" contains a superb collection of pictures, sculpture, engravings, and national relics. Here a table may be seen which formerly stood in Christian II.'s prison. History tells how the unhappy King was wont to pace round this table for hours taking his daily exercise, leaning upon his hand, which in time ploughed a groove in its hard surface. The Amalienborg, a fine tessellated square, contains four Royal palaces, in one of which our Queen Alexandra spent her girlhood. From the windows of these palaces the daily spectacle of changing the guard is witnessed by the King and young Princes.

Copenhagen is celebrated for its palaces, its parks, porcelain, statuary, art-treasures, and last, but not least, its gaiety.

I suppose the Dane best known to English boys and girls is Hans Christian Andersen, whose charming fairy-tales are well known and loved by them all. Most of you, however, know little about his life, but are interested enough in him, I dare say, to wish to learn more, especially as the knowledge will give you keener delight—if that is possible—in reading the works of this "Prince of Story-tellers."

Andersen himself said: "My life has been so wonderful and so like a fairy-tale, that I think I had a fairy godmother who granted my every wish, for if I had chosen my own life's way, I could not have chosen better."

Hans C. Andersen was the son of a poor shoemaker, an only child, born in Odense, the capital of the Island of Funen. His parents were devoted to him, and his father, who was of a studious turn of mind, delighted in teaching his little son and interesting him in Nature. Very early in life Hans was taken for long Sunday rambles, his father pointing out to him the beauties of woods and meadows, or enchanting him with stories from the "Arabian Nights."

At home the evenings were spent in dressing puppets for his favourite show, or else, sitting on his father's knee, he listened while the latter read aloud to his mother scenes from Holberg's plays. All day Hans played with his puppet theatre, and soon began to imagine plays and characters for the dolls, writing out programmes for them as soon as he was able. Occasionally his grandmother would come and take the child to play in the garden of the big house where she lived in the gardener's lodge. These were red-letter days for little Hans, as he loved his granny and enjoyed most thoroughly the pleasant garden and pretty flowers.

The boy's first great trouble came when his father caught a fever and died, leaving his mother without any means of support. To keep the little home together his mother went out washing for her neighbours, leaving little Hans to take care of himself. Being left to his own devices, Hans developed his theatrical tendencies by constructing costumes for his puppets, and making them perform his plays on the stage of his toy theatre. Soon he varied this employment by reading plays and also writing some himself. His mother, though secretly rejoicing in her son's talent, soon saw the necessity for his doing something more practical with his time and assisting her to keep the home together. So at twelve years of age Hans was sent to a cloth-weaving factory, where he earned a small weekly wage. The weavers soon discovered that Hans could sing, and the men frequently made him amuse them, while the other boys were made to do his work. One day the weavers played a coarse practical joke on poor sensitive Hans, which sent him flying home in such deep distress that his mother said he should not again return to the factory.

Hans was now sent to the parish school for a few hours daily, and his spare time was taken up with his "peep-show" and in fashioning smart clothes for his puppets. His mother intended to apprentice her son to the tailoring, but Hans had fully made up his mind to become an actor and seek his fortune in Copenhagen. After his Confirmation—on which great occasion he wore his father's coat and his first new boots—his mother insisted on his being apprenticed without further delay. With difficulty he finally succeeded in persuading her to let him start for the capital with his few savings. His mother had married again, so could not accompany him; therefore, with reluctance and with many injunctions to return at once if all did not turn out well, she let him go. Accompanying him to the town gate, they passed a gipsy on the way, who, on being asked what fortune she could prophesy for the poor lad, said he would return a great man, and his native place would be illuminated and decorated in his honour!

Hans arrived in Copenhagen on September 5, a date which he considered lucky for ever after. A few days in the city soon saw an end to his money. He applied and got work at a carpenter's shop, but was driven away by the coarseness of his fellow-workers. Hans made a friend of the porter at the stage-door of the theatre, and begged for some employment in the theatre; so occasionally he was allowed to walk across the stage in a crowd, but obtained scanty remuneration, and the lad was often hungry. Starving and destitute, the happy idea occurred to our hero to try and earn something by his voice. He applied to Siboni, the Director of the Music School, and was admitted to his presence whilst the latter was at dinner. Fortunately for Hans, Baggersen the poet and Weyse the celebrated composer were of the party, so for their amusement the boy was asked to sing and recite. Weyse was so struck by the quality of his voice and Baggersen with his poetic feeling, that they made a collection among them there and then for him, and Siboni undertook to train his voice. Unfortunately, in six months' time his voice gave way, and Siboni counselled him to learn a trade. Hans returned to the theatre in the hope of employment, and his persistence finally gained him a place in a market scene. Making a friend of the son of the librarian, he obtained permission to read at the library, and he wrote tragedies and plays, some of which he took to the director of the theatre. This man became Andersen's friend for life, for the grains of gold which he saw in his work, marred though it was by want of education, roused his interest. The director brought Andersen to the notice of the King, and he was sent to the Latin school, where he took his place—although now a grown man—among the boys in the lowest class but one. The master's tongue was sharp, and the sensitive youth was dismayed by his own ignorance. The kindness and sympathetic encouragement of the director was the only brightness of this period of Hans' life. University life followed that of school, and Andersen took a good degree. He now wrote a play, which was accepted and produced at the theatre with such success that he wept for joy. Soon his poems were published, and happiness and prosperity followed. Later the King granted him a travelling stipend, of forty-five pounds a year, and travelling became his greatest pleasure. Andersen visited England two or three times, and reckoned Charles Dickens among his friends. He was the honoured guest of Kings and Princes, and the Royal Family of Denmark treated him as a personal friend.

Though his "Fairy Tales" are the best known of his writings, he wrote successful novels, dramas and poems. Andersen's tastes were simple, and his child-like, affectionate nature made him much beloved by all. His native town, which he left as a poor boy, was illuminated and decorated to welcome his return. Thus the gipsy's prophecy came true. He died after the public celebration of his seventieth birthday, leaving all his fortune to the family of his beloved benefactor, the director of the theatre. A beautiful bronze monument is erected to his memory in the children's garden of the King's Park, Copenhagen. Here the little Danes have ever a gentle reminder of their great friend, Hans C. Andersen, who felt—to use his own words—"like a poor boy who had had a King's mantle thrown over him."

Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), the famous Danish sculptor, was born in Copenhagen. His father was an Icelander, his mother a Dane, and both very poor. Bertel's ambition when a little boy was to work his mother's spinning-wheel, which, of course, he was never permitted to do. One bright, moonlight night his parents were awakened by a soft, whirring sound, and found their little son enjoying his realized ambition. In the moonlit room he had successfully started the wheel and begun to spin, much to his parents' astonishment. This was the beginning of his creative genius, but many years went over his youthful head before he created the works which made him famous. His father carved wooden figure-heads for ships, and intended his son to follow the same calling. Bertel, however, soon showed talent and inclination for something better, and was sent to the Free School of the Art Academy, there making great progress. He received very little education beyond what the Art School gave him, and his youthful days were hard and poverty-stricken. When his hours at the Academy were over he went from house to house trying to sell his models, and in this way eked out a scanty living. In spite of his poverty he was wholly satisfied, for his wants were few. His dog and his pipe, both necessities for happiness, accompanied him in all his wanderings.

His true artistic career only began in earnest when he won a travelling scholarship and went to Rome, where he arrived on his twenty-seventh birthday. Stimulated to do his best by the many beautiful works of art which surrounded him, he found production easy, and the classical beauty of the Roman school appealed to him. Regretting his wasted years, he set to work in great earnest, and during the rest of his life produced a marvellous amount of beautiful work. A rich Scotsman bought his first important work, and the money thus obtained was the means of starting him firmly on his upward career. This highly talented Dane founded the famous Sculpture School of Denmark, which is of world-wide reputation. Thorvaldsen's beautiful designs—which were mainly classical—were conceived with great rapidity, and his pupils carried many of them out, becoming celebrated sculptors also. Dying suddenly in 1844, while seated in the stalls of the theatre watching the play, his loss was a national calamity. He bequeathed all his works to the nation, and these now form the famous Thorvaldsen Museum, which attracts the artistic-loving people of all nations to the city of Copenhagen.

In the courtyard of this museum lies the great man's simple grave, his beautiful works being contained in the building which surrounds it.

At the top of this Etruscan tomb stands a fine bronze allegorical group—the Goddess of Victory in her car, drawn by prancing horses—fitting memorial to this greatest of northern sculptors.

Holger Drachmann was the son of a physician, and quite early in life became a man of letters. Following the profession of an artist, he became a very good marine painter. This poet loved the sea in all its moods, and was never happier than when at Skagen—the extreme northern point of Jutland—where he spent most of his summers. His painting was his favourite pastime, but poetry the serious work of his life. He was a very prolific writer, not only of verse and lyrical poems, but of plays and prose works, and was a very successful playwright. Drachmann's personality was a strong one, though not always agreeable to his countrymen. He had a freedom-loving spirit, and lived every moment of his life. Some of his best poems are about the Skaw fishermen, and later in life he settled down among them, dying at Skagen in 1907. He was a picturesque figure, with white flowing locks, erratic and unpractical, as poets often are. Like other famous Danes, he chose a unique burial-place. Away at Grenen, in the sand-dunes, overlooking the fighting waters of the Skagerack and Cattegat, stands his cromlech-shaped tomb, near the roar of the sea he loved so much, where time and sand will soon obliterate all that remains of the Byron of Denmark.

Nikolai Frederik Grundtvig, the founder of the popular high-schools for peasants, was born at his father's parsonage, Udby, South Seeland. He was sent to school in Jutland, and soon learned to love his wild native moors. While attending the Latin School in Aarhus he made friends with an old shoemaker, who used to tell him interesting stories of the old Norse heroes and sagas, often repeating the old Danish folk-songs. The lad being a true Dane, a descendant of the old vikings, he soon became very interested in the history of his race. Being sent to the University of Copenhagen, he chose to study Icelandic in order to read the ancient sagas, English to read Shakespeare, and German to read Goethe. This studious youth was most patriotic, and the poetry of his country appealed to him especially. Øehlenschläger's (a Danish poet) works fired his poetical imagination.

Grundtvig's poems were for the people, the beloved Jutland moors and Nature generally his theme. His songs and poems are loved by the peasants, and used at all their festivals. He wrote songs "that would make bare legs skip at sound of them," and, "like a bird in the greenwood, he would sing for the country-folk." So successfully did he write these folk-songs, that "bare legs" do skip at the sound of them even to-day at every festivity. He was an educational enthusiast, and his high-schools are peculiar to Denmark. It is owing to these that the country possesses such a splendid band of peasant farmers. Being a priest, he was given the honorary title of Bishop, and founded a sect called "Grundtvigianere."

This noble man died in 1872, over ninety years of age, working and preaching till the last, his deep-set eyes, flowing white hair and beard, making him look like Moses of old.

Adam Øehlenschläger, the greatest Danish dramatist and poet, was a Professor at the University of Copenhagen, and a marvellously gifted man. He developed and gave character to Danish literature, and is known as the "Goethe of the North." Some of his finest tragedies have been translated into English. These have a distinctly northern ring about them, dealing as they do with the legends and sagas of the Scandinavian people. These tragedies of the mythical heroes of Scandinavia, the history of their race, and, indeed, all the works of this king of northern poets, are greatly loved by all Scandinavians. Every young Dane delights in Øehlenschläger as we do in Shakespeare, and by reading his works the youths of Denmark lay the foundation of their education in poetry. This bard was crowned Laureate in Lund (Sweden) by the greatest of Swedish poets, Esaias Tegner, 1829. Buried by his own request at his birth-place, Frederiksberg, two Danish miles (which means eight English miles) from Copenhagen, his loving countrymen insisted on carrying him the whole distance, so great was their admiration for this King of dramatists.

Niels Ryberg Finsen, whose name I am sure you have heard because his scientific research gave us the "light-cure"—which has been established at the London Hospital by our Queen Alexandra, who generously gave the costly apparatus required for the cure in order to benefit afflicted English people—was born at Thorshavn, the capital of the Faroe Islands. These islands are under Denmark, and lie north of the Shetlands. His father was magistrate there. His parents were Icelanders. At twelve years of age Niels was sent to school in Denmark, and after a few years at the Grammar School of Herlufholm, he returned to his parents, who were now stationed in their native town, Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland. Niels continued his studies there, and when old enough returned to Denmark to commence his medical work at the University of Copenhagen.

Hitherto he had shown no particular aptitude, but in his medical work he soon distinguished himself, and his skill gained him a place in the laboratory. He now began to study the effect of light as a curative remedy. All his life Finsen thought the sunlight the most beautiful thing in the world—perhaps because he saw so little of it in his childhood. He had watched its wonderful effect on all living things, being much impressed by the transformation caused in nature by the warm life-giving rays. With observations on lizards, which he found charmingly responsive to sun effects, he accidentally made his discovery, and gave to the world this famous remedy for diseases of the skin, which has relieved thousands of sufferers of all nations.

The legend of Holger Danske, who is to be Denmark's deliverer when heavy troubles come upon her, is one which has its counterpart in other countries, resembling that of our own King Arthur and the German Frederick Barbarossa. When Denmark's necessity demands, Holger Danske will come to her aid; till then he sits "in the deep dark cellar of Kronborg Castle, into which none may enter. He is clad in iron and steel, and rests his head on his strong arms; his long beard hangs down upon the marble table, into which it has become firmly rooted; he sleeps and dreams. But in his dreams he sees all that happens in Denmark. On each Christmas Eve an angel comes to him and tells him all he has dreamed is true, and that he may sleep again in peace, as Denmark is not yet in real danger. But should danger ever come, then Holger Danske will rouse himself, and the table will burst asunder as he draws out his beard. Then he will come forth in all his strength, and strike a blow that shall sound in all the countries of the world."

Holger Danske was the son of the Danish King Gotrick. While he was a youth his father sent him to Carolus Magnus, whom he served during all his wars. Thus he came to India, where he ate a fruit which made his body imperishable. When Denmark is near ruin, and all her young men have been slain in defending her, then Holger Danske will appear, and, gathering round him all the young boys and aged men, will lead them on to victory, routing the enemy, and thus saving the country. When a little plant growing in the Lake of Viborg has become a tree, so large that you can tie your horse to it, then the time draws near when all this will happen.

Once upon a time the Danes were in great trouble, for they had no King. But one day they saw a barque, splendidly decked, sailing towards the coast of Denmark. As the ship came nearer the shore they saw it was laden with quantities of gold and weapons, but not a soul was to be seen on board. When the Danes boarded the ship, they found a little boy lying asleep on the deck, and above his head floated a golden banner. Thinking that their god Odin had sent the boy, they brought him ashore and proclaimed him King. They named him Skjold, and he became a great and good King. His fame was such that the Danish Kings to this day are called "Skjoldunger." When this King died, his body was placed on board a ship which was loaded with treasure; and when it sailed slowly away over the blue water, the Danes stood on the shore looking after it with sorrow. What became of the ship no one ever knew.

Denmark is rich in legends. There is the legend about the "Danebrog," Denmark's national flag, which is a white cross on a crimson ground. This bright and beautiful flag looks thoroughly at home whatever its surroundings. The story goes that when Valdemar Seir (the Victorious) descended on the shores of Esthonia to help the knights who were hard pressed in a battle with the heathen Esthonians (1219), a miracle befell him. The valour of his troops soon made an impression on the pagans, and they began to sue for peace. It was granted, and the priests baptized the supposed converts. Very soon, however, the Esthonians, who had been secretly reinforcing while pretending submission, in order to throw dust in the eyes of the too confiding Danes, brought up their forces and commenced fighting anew. "It was the eve of St. Vitus, and the Danes were singing Vespers in camp, when suddenly a wild howl rang through the summer evening, and the heathens poured out of the woods, attacked the surprised Danes on all sides, and quickly thinned their ranks. The Danes began to waver, but the Prince of Rugen, who was stationed on the hill, had time to rally his followers and stay the progress of the enemy. It was a terrible battle. The Archbishop Andreas Sunesen with his priests mounted the hill to lay the sword of prayer in the scales of battle; the Danes rallied, and their swords were not blunt when they turned upon their enemies. Whilst the Archbishop and others prayed, the Danes were triumphant; but when his arms fell to his side through sheer weariness, the heathens prevailed. Then the priests supported the aged man's arms, who, like Moses of old, supplicated for his people with extended hands. The battle was still raging, and the banner of the Danes had been lost in the fight. As the prayers continued the miracle happened. A red banner, with the Holy Cross in white upon it, came floating gently down from the heavens, and a voice was heard saying, 'When this sign is borne on high you shall conquer.' The tide of battle turned, the Christians gathered themselves together under the banner of the Cross, and the heathens were filled with fear and fled. Then the Danes knelt down on the battle-field and praised God, while King Valdemar drew his sword, and for the first time under the folds of the Danebrog dubbed five-and-thirty of the bravest heroes knights." Another legend tells the fate of a wicked Queen of Denmark, Gunhild by name. This Queen was first the consort of a Norwegian monarch, who, finding her more than he or his people could stand, thrust her out of his kingdom. She made her way to Denmark, and soon after married the Danish King. Though beautiful, Queen Gunhild's pride and arrogance made her hateful to her new subjects, and her attendants watched their opportunity to rid themselves of such an obnoxious mistress. The time came for them when the Queen was travelling through Jutland. A sign was given to her bearers, whilst journeying through the marshes near Vejle, to drop her down into the bog. This was done, and a stake driven through her body. To-day in the church at Vejle a body lies enclosed in a glass coffin, with a stake lying beside it, the teeth and long black hair being in excellent preservation. This body was found in 1821, when the marshes near Vejle were being drained for cultivation. The stake was found through it, thus giving colour to the tradition. Poor Queen! lost in the eleventh century and found in the nineteenth.

The Danes, like all the Scandinavians, are renowned for their love of dancing. Lately they have revived the beautiful old folk-dances, realizing at last the necessity of keeping the ancient costumes, dances and songs before the people, if they would not have them completely wiped out. A few patriotic Danes have formed a society of ladies and gentlemen to bring about this revival. These are called the folk-dancers, their object being to stimulate the love of old-time Denmark in the modern Dane, by showing him the dance, accompanied by folk-song, which his forefathers delighted in. Old-time ways the Dane of to-day is perhaps a little too ready to forget, but dance and song appeal to his northern nature. The beautiful old costumes of the Danish peasants have almost entirely disappeared, but those worn by the folk-dancers are facsimiles of the costumes formerly worn in the districts they represent. These costumes, with heavy gold embroidery, curious hats, or pretty velvet caps, weighty with silver lace, must have been a great addition to local colouring. The men also wore a gay dress, and it is to be regretted that these old costumes have disappeared from the villages and islands of Denmark.

In olden times the voice was the principal accompaniment of the dance, and these folk-lorists generally sing while dancing; but occasionally a fiddler or flautist plays for them, and becomes the leader in the dance. Some of these dances are of a comical nature, and no doubt were invented to parody the shortcomings of some local character. Others represent local industries. A pretty dance is "Vœve Vadmel" (cloth-weaving). In this some dancers become the bobbins, others form the warp and woof; thus they go in and out, weaving themselves into an imaginary piece of cloth. Then, rolling themselves into a bale, they stand a moment, unwind, reverse, and then disperse. This dance is accompanied by the voices of the dancers, who, as they sing, describe each movement of the dance. A very curious dance is called "Seven Springs," and its principal figure is a series of springs from the floor, executed by the lady, aided by her partner. Another two are called respectively the "Men's Pleasure" and the "Girls' Pleasure." In these both men and girls choose their own partners, and coquet with them by alluring facial expressions during the dance. The "Tinker's Dance" is a solo dance for a man, which is descriptive and amusing; while the "Degnedans" is more an amusing performance in pantomime than a dance, executed by two men. Many more than I can tell you about have been revived by the folk-dancers, who take a keen delight in discovering and learning them. They are entertaining and instructive to the looker-on, and a healthy, though fatiguing, amusement for the dancers.

In the Faroe Islands the old-time way is still in vogue, and the dance is only accompanied by the voice and clapping of hands. Thus do these descendants of the old vikings keep high festival to celebrate a good "catch" of whales.

The old folk-songs, which were sung by the people when dancing and at other times, have a national value which the Danes fully realize, many being written down and treasured in the country's archives.

The Danes being a polite and well-mannered race, the children are early taught to tender thanks for little pleasures, and this they do in a pretty way by thrusting out their tiny hands and saying, "Tak" (Thank you). It is the Danish custom to greet everybody, including the servants, with "Good-morning," and always on entering a shop you give greeting, and say farewell on leaving. In the market-place it is the same; also the children, when leaving school, raise their caps to the teacher and call out, "Farvel! farvel!" In the majority of houses when the people rise from the table they say, "Tak for Mad"[1] to the host, who replies, "Velbekomme."[2] The children kiss their parents and say the same, while the parents often kiss each other and say, "Velbekomme." The Danes are rather too eager to wipe out old customs, and in Copenhagen the fashionable people ignore this pretty ceremony. The majority, however, feel uncomfortable if not allowed to thank their host or hostess for their food.

A Danish lady, about to visit England for the first time, was told that here it was customary to say "Grace" after meals. The surprise of the English host may be imagined when his Danish guest, on rising from the table, solemnly put out her hand and murmured the word "Grace!" After a day or two, when this ceremony had been most dutifully performed after every meal, the Englishman thought he had better ask for an explanation. This was given, and the young Dane joined heartily in the laugh against herself!

The Danes begin their day with a light breakfast of coffee, fresh rolls, and butter, but the children generally have porridge, or "öllebröd," before starting for school. This distinctly Danish dish is made of rye-bread, beer, milk, cream, and sometimes with the addition of a beaten-up egg. This "Ske-Mad"[3] is very sustaining, but I fear would prove a little too much for those unaccustomed to it. Øllebröd also is the favourite Saturday supper-dish of the working-classes, with the addition of salt herrings and slices of raw onion, which doubtless renders it more piquant.

At noon "Mid-dag"[4] is served. Another peculiar delicacy common both to this meal and supper is "Smörrebröd," a "variety" sandwich consisting of a slice of bread and butter covered with sausage, ham, fish, meat, cheese, etc. making a tempting display, not hidden as in our sandwich by a top layer of bread. The Danes are very hospitable, and often invite poor students to dine with them regularly once a week. Dinner consists of excellent soup (in summer made of fruit or preserves), meat, pudding or fruit, and cream, and even the poorest have coffee after this meal.

Prunes, stewed plums or apples, and sometimes cranberry jam, are always served with the meat or game course, together with excellent but rather rich sauce. The Danish housewife prides herself on the latter, as her cooking abilities are often judged by the quality of her sauces. It is quite usual for the Danish ladies to spend some months in learning cooking and housekeeping in a large establishment to complete their education.

"Vær saa god"[5] says the maid or waiter when handing you anything, and this formula is repeated by everyone when they wish you to enter a room, or, in fact, to do anything.

Birthdays and other anniversaries are much thought of in Denmark. The "Födelsdagsbarn"[6] is generally given pretty bouquets or pots of flowers, as well as presents. Flowers are used on every joyous occasion. Students, both men and women, may be seen almost covered with bright nosegays, given by their friends to celebrate any examination successfully passed.

Christmas Eve, and not Christmas Day, is the festive occasion in Denmark. Everybody, including the poorest, must have a Christmas-tree, and roast goose, apple-cake, rice porridge with an almond in it, form the banquet. The lucky person who finds the almond receives an extra present, and much mirth is occasioned by the search. The tree is lighted at dusk, and the children dance round it and sing. This performance opens the festivities; then the presents are given, dinner served, and afterwards the young people dance.

Christmas Day is kept quietly, but the day after (St. Stephen's Day) is one of merriment and gaiety, when the people go from house to house to greet their friends and "skaal" with them.

New Year's Eve brings a masque ball for the young folk, a supper, fireworks, and at midnight a clinking of glasses, when healths are drunk in hot punch.

On Midsummer's Night fires are lighted all over the country, and people gather together to watch the burning of the tar-barrels. Near a lake or on the seashore the reflections glinting on the water make a strangely brilliant sight. On some of the fjords a water carnival makes a pretty addition to these fires, which the children are told have been lighted to scare the witches!

The Monday before Lent is a holiday in all the schools. Early in the morning the children, provided with decorated sticks, "fastelavns Ris," rouse their parents and others from slumber. All who are found asleep after a certain time must pay a forfeit of Lenten buns. Later in the day the children dress themselves up in comical costume and parade the streets, asking money from the passer-by as our children do on Guy Fawkes' Day.

A holy-day peculiar to Denmark is called "Store-Bededag" (Great Day of Prayer), on the eve of which (Danes keep eves of festivals only) the church bells ring and the people promenade in their best clothes. "Store-Bededag" is the fourth Friday after Easter, and all business is at a standstill, so that the people can attend church. On Whit-Sunday some of the young folks rise early to see the sun dance on the water and wash their faces in the dew. This is in preparation for the greatest holiday in the year, Whit-Monday, when all give themselves up to outdoor pleasure.

"Grundlovsdag," which is kept in commemoration of the granting of a free Constitution to the nation by Frederik VII., gives the town bands and trade-unions an opportunity to parade the streets and display their capability in playing national music. "Children's Day" is a school holiday, and the children dress in the old picturesque Danish costumes; they then go about the town and market-places begging alms for the sanatoriums in their collecting-boxes. In this way a large sum is collected for these charities.

"Knocking-the-cat-out-of-the-barrel" is an old custom of the peasantry which takes place the Monday before Lent. The young men dress themselves gaily, and, armed with wooden clubs, hie them to the village green. Here a barrel is suspended with a cat inside it. Each man knocks the barrel with his club as he runs underneath it, and he who knocks a hole big enough to liberate poor puss is the victor. The grotesque costumes, the difficulty of stooping and running under the barrel in them, when all your energies and attention are required for the blow, result in many a comical catastrophe, which the bystanders enjoy heartily. Puss is frightened, but not hurt, and I think it would be just as amusing without the cat, but the Danish peasants think otherwise. Another pastime which takes place on the same day is called "ring-riding." The men, wearing paper hats and gay ribbons, gallop round the course, trying to snatch a suspended ring in passing. The man who takes the ring three times in succession is called "King," he who takes it twice "Prince." When the sport is over, King and Prince, with their train of unsuccessful competitors, ride round to the farms and demand refreshment for their gay cavalcade, of which "Æleskiver," a peasant delicacy, washed down by a glass of aqua-vitæ, forms a part.

On the eve of "Valborg's Dag" (May-Day) bonfires are lighted, and the young Danes have a dinner and dance given to them. Each dance is so long that it is customary for the young men to change their partners two or three times during the waltz.

A beautiful custom is still preserved among the older peasantry: when they cross the threshold of their neighbour's house they say, "God's peace be in this house."

All domestic servants, students, and other people who reside away from home for a time, take about with them a chest of drawers as well as a trunk. I suppose they find this necessary, because in Denmark a chest of drawers is seldom provided in a bedroom.

When the first snowdrops appear, the boys and girls gather some and enclose them in a piece of paper, on which is written a poem. This "Vintergække-Brev," which they post to their friends, is signed by ink-spots, as numerous as the letters in their name. The friend must guess the name of the sender within a week, or the latter demands a gift.

Confirmation means coming-out in Denmark. As this is the greatest festival of youth, the young folk are loaded with presents; then girls put up their hair and boys begin to smoke.

The marriage of a daughter is an expensive affair for parents in Denmark, as they are supposed to find all the home for the bride, as well as the trousseau. The wedding-ring is worn by both while engaged, as well as after the marriage ceremony.

The Epiphany is celebrated in many homes by the burning of three candles, and the children are given a holiday on this, the festival of the Three Kings. No doubt you know this is a commemoration of the three wise men of the East presenting their offerings of gold, frankincense, and myrrh to our Lord.

Storks are considered the sacred birds of Denmark. These harbingers of good-luck the children take great interest in, and more especially in the growth of the stork family on the roof-tree.

Jutland is the only province left to Denmark which can claim to be mainland, and though it is the most northern part of the country, some of its scenery is very beautiful.

The "Jyde," as the people of Jutland are called, are proud of their birthplace, of their language, and of their pronunciation, which the Copenhageners call "accent," but the Jyde declare they speak the purest Danish in the kingdom. However this may be, I am not in a position to judge, but I do know that I can understand the Jyde Danish better, and that it falls upon my ear with a more pleasing sound than does the Danish of the Copenhageners.

The east coast of Jutland is quite charming, so we will start our tour from the first interesting spot on this route, and try to obtain a glimpse of the country.

In Kolding stands a famous castle, which was partially burnt down in 1808. This gigantic ruin is now covered in, and used as an historical museum for war relics.

Fredericia is a very important place. Here that part of the train which contains the goods, luggage, and mails, as well as the first-class passenger carriages for Copenhagen, is shunted on to the large steam ferry-boat waiting to receive it. This carries it across the smiling waters of the Little Belt. A fresh engine then takes it across the island of Funen to the steam-ferry waiting to carry it across the Great Belt to Korsör, on the shores of Seeland, when a locomotive takes the train to Copenhagen in the ordinary way. These steam-ferries are peculiar to Denmark, and are specially built and equipped for this work. Danish enterprise overcomes the difficulties of transport through a kingdom of islands by these ferries.

Fredericia is an old fortified town with mighty city walls, which make a fine promenade for the citizens, giving them a charming view of the Little Belt's sunlit waters. In this town the Danes won a glorious victory over the Prussians in 1849.

Vejle is one of the most picturesque places on the east coast. Along the Vejlefjord the tall, straight pines of Jutland are reflected in the cool, still depths of blue water, and the tiniest of puffing steamers will carry you over to Munkebjerg. The fascinating and famous Munkebjerg Forest is very beautiful—a romantic place in which the youthful lovers of Denmark delight. These glorious beech woods extend for miles, the trees sloping down to the water's edge from a high ridge, whence you have a magnificent view of the glittering fjord. Most inviting are these cool green shades on a hot summer's day, but when clothed in the glowing tints of autumn they present to the eye a feast of gorgeous colour. A golden and warm brown carpet of crisp, crackling leaves underfoot, the lap of the fjord as a steamer ploughs along, sending the water hissing through the bowing reeds which fringe the bank, make the soothing sounds which fall on lovers' ears as they wander through these pleasant glades.

In winter this forest is left to the snow and hoarfrost, and cold, cairn beauty holds it fast for many days.

The pretty hotel of Munkebjerg, standing on the summit of the ridge, which you espy through a clearing in the trees, is reached by some scores of steps from the landing-stage. Patient "Moses," the hotel luggage-carrier, awaits the prospective guests at the pier. This handsome brown donkey is quite a character, and mounts gaily his own private zigzag path leading to the hotel when heavily laden. His dejection, however, when returning with empty panniers, is accounted for by the circumstance of "No load, no carrot!" at the end of the climb.

Grejsdal is another beautiful spot inland from the fjord, past which the primitive local train takes us to Jellinge. In this quaint upland village stand the two great barrows, the reputed graves of King Gorm and Queen Thyra, his wife, the great-grandparents of Canute the Great, the Danish King who ruled over England for twenty years. A beautiful Norman church stands between these barrows, and two massive Runic stones tell that "Harald the King commanded this memorial to be raised to Gorm, his Father, and Thyra, his Mother: the Harald who conquered the whole of Denmark and Norway, and Christianized the Danes." Steps lead to the top of these grassy barrows, and so large are they that over a thousand men can stand at the top. The village children use them as a playground occasionally.

Skanderborg, which is prettily situated on a lake, is a celebrated town. Here a famous siege took place, in which the valiant Niels Ebbesen fell, after freeing his country from the tyrannical rule of the German Count Gert.

Aarhus, the capital of Jutland, is the second oldest town in Denmark. Its interesting cathedral is the longest in the kingdom, and was built in the twelfth century. The town possesses a magnificent harbour, on the Cattegat, the shores of which make a pleasant promenade.

Randers is a pretty place, with many quaint thatched houses belonging to the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. The Gudenaa, Denmark's only river, skirts the town. This river is narrow and slow-moving, as there are no heights to give it force.

Hobro, situated on a fjord, wears an air of seclusion, lying as it does far away from the railway-station. A sail on this fjord will bring us to Mariager, the smallest town in Denmark. Renowned are the magnificent beech-woods and ancient abbey of this tiny town. In the surroundings we have a panoramic view of typical Jutish scenery—a charming landscape in the sunset glow, forest, fjord, farmsteads, and moor affording a rich variety of still life.

Aalborg, the delightful old market town on the Limfjord, is fascinating, especially at night, when its myriad lamps throw long shafts of light across the water. Scattered through the town are many old half-timbered houses. These beautiful buildings, with their cream-coloured rough-cast walls, oak beams, richly carved overhanging eaves, and soft-red tiled roofs, show little evidence of the ravages of time. The most famous of these houses was built, in the seventeenth century, by Jens Bang, an apothecary. The chemist's shop occupies the large ground-floor room, the windows of which have appropriate key-stones. On one is carved a man's head with swollen face, another with a lolling tongue, and similar grotesques.

To be an idler and watch the traffic going to and fro over the pontoon bridge which spans the Limfjord is a delightful way of passing the time. Warmed by the sun and fanned by the breezes which blow along the fjord, you may be amused and interested for hours by the life that streams past you. Occasionally the traffic is impeded by the bridge being opened to allow the ships to pass through. Small vessels can in this way save time and avoid the danger of rounding the north point of Jutland. If you look at your map you will see that this fjord cuts through Jutland, thus making a short passage from the Cattegat to the North Sea.

Jutland north of the Limfjord is called Vendsyssel. Curious effects of mirage may be seen in summer-time in the extensive "Vildmose"[7] of this district.

As we pass through Vendsyssel homely farmsteads and windmills add a charm to the landscape, while tethered kine and sportive goats complete a picture of rural life.

When we arrive at Frederikshavn we come to the end of the State railway. This terminus lies close to the port, which is an important place of call for the large passenger and cargo steamers bound for Norway and other countries, as well as being a refuge for the fishing-fleet.

A slow-moving local train takes us across the sandy wastes to Skagen, a straggling village, with the dignity of royal borough, bestowed upon it by Queen Margaret, in the fourteenth century, as a reward to the brave fishermen who saved from shipwreck some of her kins-folk. Skagen is a picturesque and interesting place, the home of many artists, as well as a noted seaside resort.

Bröndum's Hotel, a celebrated hostelry, where the majority of visitors and artists stay, is a delightfully comfortable, homely dwelling. The dining-room, adorned with many specimens of the artists' work, is a unique and interesting picture-gallery.

On the outskirts of the town the white tower of the old church of Skagen may be seen peeping over the sand-dunes. This "stepped" tower, with its red-tiled, saddle-back roof, forms a striking feature in this weird and lonely landscape. The church itself is buried beneath the sand, leaving only the tower to mark the place that is called the "Pompeii of Denmark," sand, not lava, being answerable for this entombment. It is said that the village which surrounded the church was buried by a sandstorm in the fourteenth century. This scene of desolation, on a windy day, when the "sand fiend" revels and riots, is best left to the booming surf and avoided by those who do not wish to be blinded.

To the south of Skagen lie other curious phenomena created by this "Storm King." The "Raabjerg Miler" are vast and characteristic dunes of powdery sand in long ridges, like huge waves petrified in the very act of turning over! In the neighbouring quicksands trees have been planted, but refuse to grow.

Viborg, the old capital of Jutland, possesses an historically interesting cathedral. In the crypt stands the tomb of King Eric Glipping, as well as those of other monarchs. The interior of the cathedral is decorated with fine frescoes by modern artists.

As we journey to Silkeborg we pass through the vast heathland, "Alhede," and are impressed by the plodding perseverance of the heath-folk. The marvellous enterprise of the Danes who started and have so successfully carried out the cultivation of these barren tracts of land deserves admiration. The convicts are employed in this work, planting, trenching, and digging, making this waste land ready for the farmer. These men have a cap with a visor-like mask, which can be pulled over the face at will. This shields the face from the cold blasts so prevalent on these moors; also, it prevents the prying eyes of strangers or fellow-workers.

Many baby forests are being nursed into sturdy growth, as a protection for farm-lands from the sand and wind storms.

This monotonous-looking heath is not without beauty; indeed, it has a melancholy charm for those who dwell on it. The children love it when the heather is in bloom, and spend happy days gathering berries from out of the gorgeous purple carpet. The great stacks of peat drying in the sun denote that this is the principal fuel of the moor-folk.

From Silkeborg we start to see the Himmelbjerget, the mountain of this flat country. It rises to a height of five hundred feet, being the highest point in Denmark.

'Tis the joy and pride of the Danes, who select this mountain and lake district before all others for their honeymoons!

A curious paddle-boat, worked by hand, or a small motor-boat will take us over the lake to the foot of Himmelbjerget. Our motor-boat, with fussy throb, carries us away down the narrow river which opens into the lake. The life on the banks of the river is very interesting. As we sail past the pretty villas, with background of cool, green beech-woods, we notice that a Danish garden must always have a summer-house to make it complete. In these garden-rooms the Danes take all their meals in summer-time. The drooping branches of the beech-trees dip, swish, and bend to the swirl of water created by our boat, which makes miniature waves leap and run along the bank in a playful way. How delightfully peaceful the surrounding landscape is as we skim over the silvery lake and then land! The climbing of this mountain does not take long. There is a splendid view from the top of Himmelbjerget, for the country lies spread out like a map before us. This lake district is very beautiful, and when the ling is in full bloom, the heather and forest-clad hills encircling the lakes blaze with colour.

At Silkeborg the River Gudenaa flows through the lakes Kundsö and Julsö, becoming navigable, but it is only used by small boats and barges for transporting wood from the forests. The termination "Sö" means lake, while "Aä" means stream. Steen Steensen Blicher, the poet of Jutland, has described this scenery, which he loved so much, quite charmingly in some of his lyrical poems. He sings:

|

"The Danes have their homes where the fair beeches grow, By shores where forget-me-nots cluster." |

This poet did much to encourage the home industries of the moor-dwellers, being in sympathy with them, as well as with their lonely moorlands.

The old-time moor-dwellers' habitations have become an interesting museum in Herning. This little mid-Jutland town is in the centre of the moors, so its museum contains a unique collection from the homes of these sturdy peasants. The amount of delicate needlework these lonely, thrifty folks accomplished in the long winter days is surprising. This "Hedebo" needlework is the finest stitchery you can well imagine, wrought on home-spun linen with flaxen thread. Such marvellous patterns and intricate designs! Little wonder that the best examples are treasured by the nation. The men of the family wore a white linen smock for weddings and great occasions. So thickly are these overwrought with needlework that they will stand alone, and seem to have a woman's lifetime spent upon them. Needless to say, these family garments were handed down as heirlooms from father to son.

Knitting, weaving, the making of Jyde pottery and wooden shoes (which all wear), are among the other industries of these people.

As we journey through Skjern and down the west coast to Esbjerg, the end of our journey, we notice the picturesque attire of the field-workers. An old shepherd, with vivid blue shirt and sleeveless brown coat, with white straggling locks streaming over his shoulders, tends his few sheep. This clever old man is doing three things at once—minding his sheep, smoking his pipe, and knitting a stocking. The Danes are great knitters, men and women being equally good at it. Many girls are working in the fields, their various coloured garments making bright specks on the landscape. Occasionally a bullock-cart slowly drags its way across the field-road, laden with clattering milk-cans. We pass flourishing farmsteads, with storks' nests on the roofs. The father-stork, standing on one leg, keeping guard over his young, looks pensively out over the moors, thinking, no doubt, that soon it will not be worth his while to come all the way from Egypt to find frogs in the marshes! For the indefatigable Dalgas has roused the dilatory Danes to such good purpose that soon the marshes and waste lands of Jutland will be no more.

"Have you been in Tivoli?" is the first question a Copenhagener would ask you on your arrival in the gay capital. If not, your Danish friend will carry you off to see these beautiful pleasure-gardens. Tivoli is for all classes, and is the most popular place of amusement in Denmark. This delightful summer resort is the place of all others in which to study the jovial side of the Danish character. Even the King and his royal visitors occasionally pay visits, incognito, to these fascinating gardens, taking their "sixpenn'orth of fun" with the people, whose good manners would never allow them to take the slightest notice of their monarch when he is enjoying himself in this way. To children Tivoli is the ideal Sunday treat. Every taste is catered for at Tivoli, and the Saturday classical concerts have become famous, for one of the Danes' chief pleasures is good music. Tivoli becomes fairyland when illuminated with its myriad lights outlining the buildings and gleaming through the trees. The light-hearted gaiety of the Dane is very infectious, and the stranger is irresistibly caught by it. The atmosphere of unalloyed merriment which pervades when tables are spread under the trees for the alfresco supper is distinctly exhilarating. These gardens have amusements for the frivolous also, such as switchbacks, pantomimes of the "Punch and Judy" kind, and frequently firework displays, which last entertainment generally concludes the evening.

The Royal Theatre in Copenhagen is a national school of patriotism, and the healthy spirit of its plays has an ennobling effect on the people. Everything is Danish here, and Denmark is the only small nation in Europe which has successfully founded a national dramatic art. The "Molière of the North," Ludwig Holberg, was the father of the Danish drama, and the first to make the people realize the beauty of their own language. This gifted Dane was a great comedy-writer, and had the faculty of making his fellows see the comic side of their follies.

The "Royal Ballet" played at this theatre is quite distinctive. Bournonville, its creator, was a poet who expressed himself in motion instead of words, and these "dumb poems" appeal strongly to the Scandinavian character. This poet aimed at something more than spectacular effects upon the people: his art consisted in presenting instructive tableaux, which, while holding the attention of his audience, taught them their traditional history. The delicate daintiness of the Danish ballet everyone must appreciate. The exquisite and intricate dances, together with the magnificent tableaux, are accompanied by wild and magical music of Danish composition. Bournonville ballets represent scenes from classical mythology, as well as from ancient Scandinavian history, and the Danish people are much attached to this Northern composer of ballet. "Ei blot til Lyst"—Not only for pleasure—is the motto over this National Theatre door, and it is in the Ballet School here that the young Danes begin their training. These young folk take great pleasure in learning the beautiful dances, as well as in the operatic and dramatic work which they have to study, for they must serve a certain period in this, as in any other profession.

Another place of amusement which gives pleasure to many of the poorer people is the Working Men's Theatre. Actors, musicians, as well as the entire management, are all of the working classes, who are trained in the evenings by professionals. The result is quite wonderful, and proves the pleasure and interest these working people take in their tuition, and how their artistic abilities are developed by it. On Sundays, and occasionally in the week, a performance is given, when the working classes crowd into the theatre to see their fellows perform. This entertainment only costs sixpence for good seats, drama and farce being the representations most appreciated. Notwithstanding that smoking is prohibited during the performances—a rule which you would think no Dane could tolerate, being seldom seen without pipe or cigarette—it is a great success, and denotes that their love of the play is greater than their pleasure in the weed.

Farming in Denmark is the most important industry of the kingdom, and gives employment to half the nation. The peasant is very enlightened and advanced in his methods; agricultural and farm products form the principal exports of the country. England takes the greater part of this produce. Three or four times a week the ships leave Esbjerg—this port being the only Danish one not blocked by ice during some part of the winter—for the English ports, laden with butter, bacon and eggs for the London market. Now, why can the Danish farmer, whose land is poorer and his climate more severe than ours, produce so much? Education, co-operation and the help given by the State to small farmers lay the foundation, so the Danes will tell you, of the farmer's prosperity. The thrift and industry of the peasant farmer is quite astonishing. He is able to bring up a large, well-educated family and live comfortably on seven or eight acres of land; whereas in England we are told that three acres will not keep a cow! The Danish farmer makes six acres keep two cows, many chickens, some pigs, himself, wife and family, and there is never any evidence of poverty on these small farms—quite the reverse. The farmer is strong and wiry, his wife fine and buxom, and his children sturdy, well-cared-for little urchins. All, however, must work—and work very hard—both with head and hands to produce this splendid result. The Danish farmer grows a rapid rotation of crops for his animals, manuring heavily after each crop, and never allowing his land to lie fallow as we do. On these small farms there is practically no grass-land; hedges and fences are unnecessary as the animals are always tethered when grazing. Omission of hedges is more economical also, making it possible to cultivate every inch of land. There is nothing wasted on a Danish farm. Many large flourishing farms also exist in Denmark, with acres of both meadow and arable land, just as in England; but the peasant farmer is the interesting example of the Danish system of legislation. The Government helps this small holder by every means in its power to become a freehold farmer should he be willing and thrifty enough to try.

The typical Danish farmstead is built in the form of a square, three sides of which are occupied by the sheds for the animals, the fourth side being the dwelling-house, which is generally connected with the sheds by a covered passage—a cosy arrangement for all, as in bad weather the farmer need not go outside to attend to the animals, while the latter benefit by the warmth from the farmhouse.

The Danes would never speak crossly to a cow or call her by other than her own name, which is generally printed on a board over her stall. The cow, in fact, is the domestic pet of the Danish farm. In the winter these animals are taken for a daily walk wearing their winter coats of jute!

These small farmers realize that "Union is Strength," and have built up for themselves a marvellous system of co-operation. This brings the market literally to the door of the peasant farmer. Carts collect the farm produce daily and transport it to the nearest factories belonging to this co-operation of farmers. At these factories the milk is turned into delicious butter, the eggs are examined by electric light, and "Mr. Pig" quickly changes his name to Bacon! These three commodities form the most remunerative products of the farm.

The Danish farmer is a strong believer in education, thanks to the Grundtvig High-schools. Bishop Grundtvig started these schools for the benefit of the sons and daughters of yeomen. When winter comes, and outside farm-work is at a standstill, the farmer and his family attend these schools to learn new methods of farming and dairy-work. The farmer's children are early taught to take a hand and interest themselves in the farm-work. The son, when school is over for the day, must help to feed the live-stock, do a bit of spade-work or carpentering, and perhaps a little book-keeping before bedtime. These practical lessons develop in the lad a love of farm-work and a pride in helping on the family resources.

Butter-making is an interesting sight at the splendidly equipped steam-factories, and we all know that Danish butter is renowned for its excellence. When the milk is weighed and tested it runs into a large receiver, thence to the separator; from there the cream flows into the scalder, and pours over the ice frame in a rich cool stream into a wooden vat.

Meanwhile the separated milk has returned through a pipe to the waiting milk-cans and is given back to the farmer, who utilizes it to feed his calves and pigs. The cream leaves the vat for the churn through a wooden channel, and when full the churn is set in motion. This combined churn and butter-worker completes the process of butter-making, and when the golden mass is taken out it is ready to be packed for the English market. The milk, on being received at the factory, is weighed and paid for according to weight. It takes 25 lbs. of milk to make 1 lb. of butter.

"Hedeselskabet" (Heath Company) is a wonderful society started by Captain Dalgas and other patriotic Danes, in 1866, for the purpose of reclaiming the moors and bogs. The cultivation of these lands seemed impossible to most people, but these few enthusiasts with great energy and perseverance set to work to overcome Nature's obstacles. These pioneers have been so successful in their efforts that in less than half a century three thousand square miles of useless land in Jutland have been made fertile. Trees have been planted and carefully nursed into good plantations, besides many other improvements made for the benefit of the agriculturalist and the country generally. All along the sandy wastes of the west coast of Jutland esparto grass has been sown to bind the shifting sand, which is a danger to the crops when the terrible "Skaj"[8] blows across the land with unbroken force. Thanks to the untiring energies of this society for reclaiming the moors, Denmark has gained land almost equal to that she lost in her beautiful province of Schleswig, annexed by Prussia in the unequal war of 1864.

In the town of Aarhus, the capital of Jutland, a handsome monument has been raised to the memory of Captain Dalgas, the father of the movement for reclaiming the moors, by his grateful countrymen.

Every Danish boy knows he must undergo a period of training as a soldier or sailor when he reaches his twentieth year. This is because Denmark is small and poor, and could not maintain a standing army, so her citizens must be able to defend her when called upon. This service is required from all, noble and peasant alike, physical weakness alone bringing exemption. This six or twelve months' training means a hard rough time for young men accustomed to a refined home, but it has a pleasant side in the sympathy and friendship of comrades. The generality of conscripts do not love their soldiering days, and look upon them as something to be got over, like the measles! "Jens" is the Danish equivalent for "Tommy Atkins," and "Hans" is the "Jack Tar" of Denmark.

To see the daily parade of Life Guards before the royal palace is to see a splendid military display. This parade the King and young Princes often watch from the palace windows. The crowd gathers to enjoy the spectacle of "Vagt-Paraden" (changing the guard) in the palace square, when the standard is taken from the Guard House and borne, to the stirring strains of the "Fane-Marsch," in front of the palace. As the standard-bearer marches he throws forward his legs from the hips in the most curious stiff way. This old elaborate German step is a striking feature of the daily parade. When the guard is changed and the band has played a selection of music, the same ceremony is repeated, and the standard deposited again in its resting-place. Then the released guard, headed by the band playing merry tunes, march back to their barracks followed by an enthusiastic crowd. The fresh guard take their place beside the sentry-boxes, which stand around the palace square. These are tall red pillar-boxes curiously like giant letter-boxes!

In the Schleswig-Holstein War of 1864, the last war Denmark was engaged in, many Danish soldiers proved their valour and heroism in the unequal encounter. These gallant men were buried in Schleswig, and as the Danish colours were forbidden by the tyrannical Prussian conquerors, the loyal Schleswigers hit upon a pretty way of keeping the memory of their heroes green. The "Danebrog" was designed by a cross of white flowers on a ground of red geraniums over each grave. In this way the kinsmen of these patriots covered their last resting-place with the colours of their glorious national flag, under which they fell in Denmark's defence. In Holmens Kirke, Copenhagen, many heroes lie buried. This building, originally an iron foundry, was converted into a church by the royal builder, Christian IV., for the dockyard men to worship in, and it is still used by them. This King's motto, "Piety strengthens the realm," stands boldly over the entrance of this mortuary chapel for famous Danes.

As Denmark is a kingdom composed mainly of islands and peninsula, she has a long line of sea-board to defend, and a good navy is essential for her safety. The Danes being descendants of Vikings and sea-rovers, you may be sure that their navy is well maintained.