Title: The Infernal Marriage

Author: Earl of Beaconsfield Benjamin Disraeli

Release date: December 3, 2006 [eBook #20003]

Most recently updated: February 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

Proserpine was the daughter of Jupiter and Ceres. Pluto, the god of Hell, became enamoured of her. His addresses were favoured by her father, but opposed by Ceres. Under these circumstances, he surprised her on the plains of Enna, and carried her off in his chariot.

A Sublime Elopement

IT WAS clearly a runaway match—never indeed was such a sublime elopement. The four horses were coal-black, with blood-red manes and tails; and they were shod with rubies. They were harnessed to a basaltic car by a single rein of flame. Waving his double-pronged trident in the air, the god struck the blue breast of Cyane, and the waters instantly parted. In rushed the wild chariot, the pale and insensible Proserpine clinging to the breast of her grim lover.

Through the depths of the hitherto unfathomed lake the infernal steeds held their breathless course. The car jolted against its bed. ‘Save me!’ exclaimed the future Queen of Hades, and she clung with renewed energy to the bosom of the dark bridegroom. The earth opened; they entered the kingdom of the gnomes. Here Pluto was popular. The lurid populace gave him a loud shout. The chariot whirled along through shadowy cities and by dim highways, swarming with a busy race of shades.

‘Ye flowery meads of Enna!’ exclaimed the terrified Proserpine, ‘shall I never view you again? What an execrable climate!’

‘Here, however, in-door nature is charming,’ responded Pluto. ‘Tis a great nation of manufacturers. You are better, I hope, my Proserpine. The passage of the water is never very agreeable, especially to ladies.’

‘And which is our next stage?’ inquired Proserpine.

‘The centre of Earth,’ replied Pluto. ‘Travelling is so much improved that at this rate we shall reach Hades before night.’

‘Alas!’ exclaimed Proserpine, ‘is not this night?’

‘You are not unhappy, my Proserpine?’

‘Beloved of my heart, I have given up everything for you! I do not repent, but I am thinking of my mother.’

‘Time will pacify the Lady Ceres. What is done cannot be undone. In the winter, when a residence among us is even desirable, I should not be surprised were she to pay us a visit.’

‘Her prejudices are so strong,’ murmured the bride. ‘Oh my Pluto! I hope your family will be kind to me.’

‘Who could be unkind to Proserpine? Ours is a very domestic circle. I can assure you that everything is so well ordered among us that I have no recollection of a domestic broil.’

‘But marriage is such a revolution in a bachelor’s establishment,’ replied Proserpine, despondingly. ‘To tell the truth, too, I am half frightened at the thought of the Furies. I have heard that their tempers are so violent.’

‘They mean well; their feelings are strong, but their hearts are in the right place. I flatter myself you will like my nieces, the Parcæ. They are accomplished, and favourites among the men.’

‘Indeed!’

‘Oh! quite irresistible.’

‘My heart misgives me. I wish you had at least paid them the compliment of apprising them of our marriage.’

‘Cheer up. For myself, I have none but pleasant anticipations. I long to be at home once more by my own fireside, and patting my faithful Cerberus.’

‘I think I shall like Cerberus; I am fond of dogs.’

‘I am sure you will. He is the most faithful creature in the world.’

‘Is he very fierce?’

‘Not if he takes a fancy to you; and who can help taking a fancy to Proserpine?’

‘Ah! my Pluto, you are in love.’

‘Is this Hades?’ inquired Proserpine.

An avenue of colossal bulls, sculptured in basalt and breathing living flame, led to gates of brass, adorned with friezes of rubies, representing the wars and discomfiture of the Titans. A crimson cloud concealed the height of the immense portals, and on either side hovered o’er the extending walls of the city; a watch-tower or a battlement occasionally flashing forth, and forcing their forms through the lurid obscurity.

‘Queen of Hades! welcome to your capital!’ exclaimed Pluto.

The monarch rose in his car and whirled a javelin at the gates. There was an awful clang, and then a still more terrible growl.

‘My faithful Cerberus!’ exclaimed the King.

The portals flew open, and revealed the gigantic form of the celebrated watch-dog of Hell. It completely filled their wide expanse. Who but Pluto could have viewed without horror that enormous body covered with shaggy spikes, those frightful paws clothed with claws of steel, that tail like a boa constrictor, those fiery eyes that blazed like the blood-red lamps in a pharos, and those three forky tongues, round each of which were entwined a vigorous family of green rattlesnakes!

‘Ah! Cerby! Cerby!’ exclaimed Pluto; ‘my fond and faithful Cerby!’

Proserpine screamed as the animal gambolled up to the side of the chariot and held out its paw to its master. Then, licking the royal palm with its three tongues at once, it renewed its station with a wag of its tail which raised such a cloud of dust that for a few minutes nothing was perceptible.

‘The monster!’ exclaimed Proserpine.

‘My love!’ exclaimed Pluto, with astonishment.

‘The hideous brute!’

‘My dear!’ exclaimed Pluto.

‘He shall never touch me.’

‘Proserpine!’

‘Don’t touch me with that hand. You never shall touch me, if you allow that disgusting animal to lick your hand.’

‘I beg to inform you that there are few beings of any kind for whom I have a greater esteem than that faithful and affectionate beast.’

‘Oh! if you like Cerberus better than me, I have no more to say,’ exclaimed the bride, bridling up with indignation.

‘My Proserpine is perverse,’ replied Pluto; ‘her memory has scarcely done me justice.’

‘I am sure you said you liked Cerberus better than anything in the world,’ continued the goddess, with a voice trembling with passion.

‘I said no such thing,’ replied Pluto, somewhat sternly.

‘I see how it is,’ replied Proserpine, with a sob; ‘you are tired of me.’

‘My beloved!’

‘I never expected this.’

‘My child!’

‘Was it for this I left my mother?’

‘Powers of Hades! How you can say such things!’

‘Broke her heart?’

‘Proserpine! Proserpine!’

‘Gave up daylight?’

‘For the sake of Heaven, then, calm yourself!’

‘Sacrificed everything?’

‘My love! my life! my angel! what is all this?’

‘And then to be abused for the sake of a dog!’

‘By all the shades of Hell, but this is enough to provoke even immortals. What have I done, said, or thought, to justify such treatment?’

‘Oh! me!’

‘Proserpine!’

‘Heigho!’

‘Proserpine! Proserpine!’

‘So soon is the veil withdrawn!’

‘Dearest, you must be unwell. This journey has been too much for you,’

‘On our very bridal day to be so treated!’

‘Soul of my existence, don’t make me mad. I love you, I adore you; I have no hope, no wish, no thought but you. I swear it; I swear it by my sceptre and my throne. Speak, speak to your Pluto: tell him all your wish, all your desire. What would you have me do?’

‘Shoot that horrid beast.’

‘Ah! me!’

‘What, you will not? I thought how it would be. I am Proserpine, your beloved, adored Proserpine. You have no wish, no hope, no thought but for me! I have only to speak, and what I desire will be instantly done! And I do speak, I tell you my wish, I express to you my desire, and I am instantly refused! And what have I requested? Is it such a mighty favour? Is it anything unreasonable? Is there, indeed, in my entreaty anything so vastly out of the way? The death of a dog, a disgusting animal, which has already shaken my nerves to pieces; and if ever (here she hid her face in his breast), if ever that event should occur which both must desire, my Pluto, I am sure the very sight of that horrible beast will—I dare not say what it will do.’

Pluto looked puzzled.

‘Indeed, my Proserpine, it is not in my power to grant your request; for Cerberus is immortal, like ourselves.’

‘Me! miserable!’

‘Some arrangement, however, may be made to keep him out of your sight and hearing. I can banish him.’

‘Can you, indeed? Oh! banish him, my Pluto! pray banish him! I never shall be happy until Cerberus is banished.’

‘I will do anything you desire; but I confess to you I have some misgivings. He is an invaluable watch-dog; and I fear, without his superintendence, the guardians of the gate will scarcely do their duty.’

‘Oh! yes: I am sure they will, my Pluto! I will ask them to, I will ask them myself, I will request them, as a particular and personal favour to myself, to be very careful indeed. And if they do their duty, and I am sure they will, they shall be styled, as a reward, “Proserpine’s Own Guards.”’

‘A reward, indeed!’ said the enamoured monarch, as, with a sigh, he signed the order for the banishment of Cerberus in the form of his promotion to the office of Master of the royal and imperial bloodhounds.

The burning waves of Phlegethon assumed a lighter hue. It was morning. It was the morning after the arrival of Pluto and his unexpected bride. In one of the principal rooms of the palace three beautiful females, clothed in cerulean robes spangled with stars, and their heads adorned with golden crowns, were at work together. One held a distaff, from which the second spun; and the third wielded an enormous pair of adamantine shears, with which she perpetually severed the labours of her sisters. Tall were they in stature and beautiful in form. Very fair; an expression of haughty serenity pervaded their majestic countenances. Their three companions, however, though apparently of the same sex, were of a different character. If women can ever be ugly, certainly these three ladies might put in a valid claim to that epithet. Their complexions were dark and withered, and their eyes, though bright, were bloodshot. Scantily clothed in black garments, not unstained with gore, their wan and offensive forms were but slightly veiled. Their hands were talons; their feet cloven; and serpents were wreathed round their brows instead of hair. Their restless and agitated carriage afforded also not less striking contrast to the polished and aristocratic demeanour of their companions. They paced the chamber with hurried and unequal steps, and wild and uncouth gestures; waving, with a reckless ferocity, burning torches and whips of scorpions. It is hardly necessary to add that these were the Furies, and that the conversation which I am about to report was carried on with the Fates.

‘A thousand serpents!’ shrieked Tisiphone. ‘I will never believe it.’

‘Racks and flames!’ squeaked Megæra. ‘It is impossible.’

‘Eternal torture!’ moaned Alecto. ‘‘Tis a lie.’

‘Not Jupiter himself should convince us!’ the Furies joined in infernal chorus.

‘‘Tis nevertheless true,’ calmly observed the beautiful Clotho.

‘You will soon have the honour of being presented to her,’ added the serene Lachesis.

‘And whatever we may feel,’ observed the considerate Atropos, ‘I think, my dear girls, you had better restrain yourselves.’

‘And what sort of thing is she?’ inquired Tisiphone, with a shriek.

‘I have heard that she is lovely,’ answered Clotho. ‘Indeed, it is impossible to account for the affair in any other way.’

‘‘Tis neither possible to account for nor to justify it,’ squeaked Megæra.

‘Is there, indeed, a Queen in Hell?’ moaned Alecto.

‘We shall hold no more drawing-rooms,’ said Lachesis.

‘We will never attend hers,’ said the Furies.

‘You must,’ replied the Fates.

‘I have no doubt she will give herself airs,’ shrieked Tisiphone.

‘We must remember where she has been brought up, and be considerate,’ replied Lachesis.

‘I dare say you three will get on very well with her,’ squeaked Megasra. ‘You always get on well with people.’

‘We must remember how very strange things here must appear to her,’ observed Atropos.

‘No one can deny that there are some very disagreeable sights,’ said Clotho.

‘There is something in that,’ replied Tisiphone, looking in the glass, and arranging her serpents; ‘and for my part, poor girl, I almost pity her, when I think she will have to visit the Harpies.’

At this moment four little pages entered the room, who, without exception, were the most hideous dwarfs that ever attended upon a monarch. They were clothed only in parti-coloured tunics, and their breasts and legs were quite bare. From the countenance of the first you would have supposed he was in a convulsion; his hands were clenched and his hair stood on end: this was Terror! The protruded veins of the second seemed ready to burst, and his rubicund visage decidedly proved that he had blood in his head; this was Rage! The third was of an ashen colour throughout: this was Paleness! And the fourth, with a countenance not without traces of beauty, was even more disgusting than his companions from the quantity of horrible flies, centipedes, snails, and other noisome, slimy, and indescribable monstrosities that were crawling all about his body and feeding on his decaying features. The name of this fourth page was Death!

‘The King and Queen!’ announced the pages.

Pluto, during the night, had prepared Proserpine for the worst, and had endeavoured to persuade her that his love would ever compensate for all annoyances. She was in excellent spirits and in very good humour; therefore, though she could with difficulty stifle a scream when she recognised the Furies, she received the congratulations of the Parcæ with much cordiality.

‘I have the pleasure, Proserpine, of presenting you to my family,’ said Pluto.

‘Who, I am sure, hope to make Hades agreeable to your Majesty,’ rejoined Clotho. The Furies uttered a suppressed sound between a murmur and a growl.

‘I have ordered the chariot,’ said Pluto. ‘I propose to take the Queen a ride, and show her some of our lions.’

‘She will, I am sure, be delighted,’ said Lachesis.

‘I long to see Ixion,’ said Proserpine.

‘The wretch!’ shrieked Tisiphone.

‘I cannot help thinking that he has been very unfairly treated,’ said Proserpine.

‘What!’ squeaked Megæra. ‘The ravisher!’

‘Ay! it is all very well,’ replied Proserpine; ‘but, for my part, if we knew the truth of that affair——-’

‘Is it possible that your Majesty can speak in such a tone of levity of such an offender?’ shrieked Tisiphone.

‘Is it possible?’ moaned Alecto.

‘Ah! you have heard only one side of the question; but for my part, knowing as much of Juno as I do——-’

‘The Queen of Heaven!’ observed Atropos, with an intimidating glance.

‘The Queen of Fiddlestick!’ said Proserpine; ‘as great a flirt as ever existed, with all her prudish looks.’

The Fates and the Furies exchanged glances of astonishment and horror.

‘For my part,’ continued Proserpine, ‘I make it a rule to support the weaker side, and nothing will ever persuade me that Ixion is not a victim, and a pitiable one.’

‘Well! men generally have the best of it in these affairs,’ said Lachesis, with a forced smile.

‘Juno ought to be ashamed of herself,’ said Proserpine. ‘Had I been in her situation, they should have tied me to a wheel first. At any rate, they ought to have punished him in Heaven. I have no idea of those people sending every mauvais sujet to Hell.’

‘But what shall we do?’ inquired Pluto, who wished to turn the conversation.

‘Shall we turn out a sinner and hunt him for her Majesty’s diversion?’ suggested Tisiphone, flanking her serpents.

‘Nothing of the kind will ever divert me,’ said Proserpine; ‘for I have no hesitation in saying that I do not at all approve of these eternal punishments, or, indeed, of any punishment whatever.’

‘The heretic!’ whispered Tisiphone to Megæra. Alecto moaned.

‘It might be more interesting to her Majesty,’ said Atropos, ‘to witness some of those extraordinary instances of predestined misery with which Hades abounds. Shall we visit OEdipus?’

‘Poor fellow!’ exclaimed Proserpine. ‘For myself, I willingly confess that torture disgusts and Destiny puzzles me.’

The Fates and the Furies all alike started.

‘I do not understand this riddle of Destiny,’ continued the young Queen. ‘If you, Parcæ, have predestined that a man should commit a crime, it appears to me very unjust that you should afterwards call upon the Furies to punish him for its commission.’

‘But man is a free agent,’ observed Lachesis, in as mild a tone as she could command.

‘Then what becomes of Destiny?’ replied Proserpine.

‘Destiny is eternal and irresistible,’ replied Clotho. ‘All is ordained; but man is, nevertheless, master of his own actions.’

‘I do not understand that,’ said Proserpine.

‘It is not meant to be understood,’ said Atropos; ‘but you must nevertheless believe it.’

‘I make it a rule only to believe what I understand,’ replied Proserpine.

‘It appears,’ said Lachesis, with a blended glance of contempt and vengeance, ‘that your Majesty, though a goddess, is an atheist.’

‘As for that, anybody may call me just what they please, provided they do nothing else. So long as I am not tied to a wheel or whipped with scorpions for speaking my mind, I shall be as tolerant of the speech and acts of others as I expect them to be tolerant of mine. Come, Pluto, I am sure that the chariot must be ready!’

So saying, her Majesty took the arm of her spouse, and with a haughty curtsey left the apartment.

‘Did you ever!’ shrieked Tisiphone, as the door closed.

‘No! never!’ squeaked Megaera.

‘Never! never!’ moaned Alecto.

‘She must understand what she believes, must she?’ said Lachesis, scarcely less irritated.

‘I never heard such nonsense,’ said Clotho.

‘What next!’ said Atropos.

‘Disgusted with torture!’ exclaimed the Furies.

‘Puzzled with Destiny!’ said the Fates.

It was the third morning after the Infernal Marriage; the slumbering Proserpine reposed in the arms of the snoring Pluto. There was a loud knocking at the chamber-door. Pluto jumped up in the middle of a dream.

‘My life, what is the matter?’ exclaimed Proserpine.

The knocking was repeated and increased. There was also a loud shout of ‘treason, murder, and fire!’

‘What is the matter?’ exclaimed the god, jumping out of bed and seizing his trident. ‘Who is there?’

‘Your pages, your faithful pages! Treason! treason! For the sake of Hell, open the door. Murder, fire, treason!’

‘Enter!’ said Pluto, as the door was unlocked.

And Terror and Rage entered.

‘You frightful things, get out of the room!’ cried Proserpine.

‘A moment, my angel!’ said Pluto, ‘a single moment. Be not alarmed, my best love; I pray you be not alarmed. Well, imps, why am I disturbed?’

‘Oh!’ said Terror. Rage could not speak, but gnashed his teeth and stamped his feet.

‘O-o-o-h!’ repeated Terror.

‘Speak, cursed imps!’ cried the enraged Pluto; and he raised his arm.

‘A man! a man!’ cried Terror. ‘Treason, treason! a man! a man!’

‘What man?’ said Pluto, in a rage.

‘A man, a live man, has entered Hell!’

‘You don’t say so?’ said Proserpine; ‘a man, a live man. Let me see him immediately.’

‘Where is he?’ said Pluto; ‘what is he doing?’

‘He is here, there, and everywhere! asking for your wife, and singing like anything.’

‘Proserpine!’ said Pluto, reproachfully; but, to do the god justice, he was more astounded than jealous.

‘I am sure I shall be delighted to see him; it is so long since I have seen a live man,’ said Proserpine. ‘Who can he be? A man, and a live man! How delightful! It must be a messenger from my mother.’

‘But how came he here?’

‘Ah! how came he here?’ echoed Terror.

‘No time must be lost!’ exclaimed Pluto, scrambling on his robe. ‘Seize him, and bring him into the council chamber. My charming Proserpine, excuse me for a moment.’

‘Not at all; I will accompany you.’

‘But, my love, my sweetest, my own, this is business; these are affairs of state. The council chamber is not a place for you.’

‘And why not?’ said Proserpine. ‘I have no idea of ever leaving you for a moment. Why not for me as well as for the Fates and the Furies? Am I not Queen? I have no idea of such nonsense!’

‘My love!’ said the deprecating husband.

‘You don’t go without me,’ said the imperious wife, seizing his robe.

‘I must,’ said Pluto.

‘Then you shall never return,’ said Proserpine.

‘Enchantress! be reasonable.’

‘I never was, and I never will be,’ replied the Goddess.

‘Treason! treason!’ screamed Terror.

‘My love, I must go!’

‘Pluto,’ said Proserpine, ‘understand me once for all, I will not be contradicted.’

Rage stamped his foot.

‘Proserpine, understand me once for all, it is impossible,’ said the God, frowning.

‘My Pluto!’ said the Queen. ‘Is it my Pluto who speaks thus sternly to me? Is it he who, but an hour ago, a short hour ago, died upon my bosom in transports and stifled me with kisses! Unhappy woman! wretched, miserable Proserpine! Oh! my mother! my kind, my affectionate mother! Have I disobeyed you for this! For this have I deserted you! For this have I broken your beloved heart!’ She buried her face in the crimson counterpane, and bedewed its gorgeous embroidery with her fast-flowing tears.

‘Treason!’ shouted Terror.

‘Ha! ha! ha!’ exclaimed the hysterical Proserpine.

‘What am I to do?’ cried Pluto. ‘Proserpine, my adored, my beloved, my enchanting Proserpine, compose yourself; for my sake, compose yourself. I love you! I adore you! You know it! oh! indeed you know it!’

The hysterics increased.

‘Treason! treason!’ shouted Terror.

‘Hold your infernal tongue,’ said Pluto. ‘What do I care for treason when the Queen is in this state?’ He knelt by the bedside, and tried to stop her mouth with kisses, and ever and anon whispered his passion. ‘My Proserpine, I beseech you to be calm; I will do anything you like. Come, come, then, to the council!’

The hysterics ceased; the Queen clasped him in her arms and rewarded him with a thousand embraces. Then, jumping up, she bathed her swollen eyes with a beautiful cosmetic that she and her maidens had distilled from the flowers of Enna; and, wrapping herself up in her shawl, descended with his Majesty, who was quite as much puzzled about the cause of this disturbance as when he was first roused.

Crossing an immense covered bridge, the origin of the Bridge of Sighs at Venice, over the royal gardens, which consisted entirely of cypress, the royal pair, preceded by the pages-in-waiting, entered the council chamber. The council was already assembled. On either side of a throne of sulphur, from which issued the four infernal rivers of Lethe, Phlegethon, Cocytus, and Acheron, were ranged the Eumenides and Parcæ. Lachesis and her sisters turned up their noses when they observed Proserpine; but the Eumenides could not stifle their fury, in spite of the hints of their more subdued but not less malignant companions.

‘What is all this?’ inquired Pluto.

‘The constitution is in danger,’ said the Parcæ in chorus.

‘Both in church and state,’ added the Furies. ‘‘Tis a case of treason and blasphemy;’ and they waved their torches and shook their whips with delighted anticipation of their use.

‘Detail the circumstances,’ said Pluto, waving his hand majestically to Lachesis, in whose good sense he had great confidence.

‘A man, a living man, has entered your kingdom, unknown and unnoticed,’ said Lachesis.

‘By my sceptre, is it true?’ said the astonished King. ‘Is he seized?’

‘The extraordinary mortal baffles our efforts,’ said Lachesis. ‘He bears with him a lyre, the charmed gift of Apollo, and so seducing are his strains that in vain our guards advance to arrest his course; they immediately begin dancing, and he easily eludes their efforts. The general confusion is indescribable. All business is at a standstill: Ixion rests upon his wheel; old Sisyphus sits down on his mountain, and his stone has fallen with a terrible plash into Acheron. In short, unless we are energetic, we are on the eve of a revolution.’

‘His purpose?’

‘He seeks yourself and—her Majesty,’ added Lachesis, with a sneer.

‘Immediately announce that we will receive him.’

The unexpected guest was not slow in acknowledging the royal summons. A hasty treaty was drawn up; he was to enter the palace unmolested, on condition that he ceased playing his lyre. The Fates and the Furies exchanged significant glances as his approach was announced.

The man, the live man, who had committed the unprecedented crime of entering Hell without a licence, and the previous deposit of his soul as security for the good behaviour of his body, stood before the surprised and indignant Court of Hades. Tall and graceful in stature, and crowned with laurels, Proserpine was glad to observe that the man, who was evidently famous, was also good-looking.

‘Thy purpose, mortal?’ inquired Pluto, with awful majesty.

‘Mercy!’ answered the stranger in a voice of exquisite melody, and sufficiently embarrassed to render him interesting.

‘What is mercy?’ inquired the Fates and the Furies.

‘Speak, stranger, without fear,’ said Proserpine. ‘Thy name?’

‘Is Orpheus; but a few days back the too happy husband of the enchanting Eurydice. Alas! dread King, and thou too, beautiful and benignant partner of his throne, I won her by my lyre, and by my lyre I would redeem her. Know, then, that in the very glow of our gratified passion a serpent crept under the flowers on which we reposed, and by a fatal sting summoned my adored to the shades. Why did it not also summon me? I will not say why should I not have been the victim in her stead; for I feel too keenly that the doom of Eurydice would not have been less forlorn, had she been the wretched being who had been spared to life. O King! they whispered on earth that thou too hadst yielded thy heart to the charms of love. Pluto, they whispered, is no longer stern: Pluto also feels the all-subduing influence of beauty. Dread monarch, by the self-same passion that rages in our breasts alike, I implore thy mercy. Thou hast risen from the couch of love, the arm of thy adored has pressed upon thy heart, her honied lips have clung with rapture to thine, still echo in thy ears all the enchanting phrases of her idolatry. Then, by the memory of these, by all the higher and ineffable joys to which these lead, King of Hades, spare me, oh! spare me, Eurydice!’

Proserpine threw her arms round the neck of her husband, and, hiding her face in his breast, wept.

‘Rash mortal, you demand that which is not in the power of Pluto to concede,’ said Lachesis.

‘I have heard much of treason since my entrance into Hades,’ replied Orpheus, ‘and this sounds like it.’

‘Mortal!’ exclaimed Clotho, with contempt.

‘Nor is it in your power to return, sir,’ said Tisiphone, shaking her whip.

‘We have accounts to settle with you,’ said Megæra.

‘Spare her, spare her,’ murmured Proserpine to her lover.

‘King of Hades!’ said Lachesis, with much dignity, ‘I hold a responsible office in your realm, and I claim the constitutional privilege of your attention. I protest against the undue influence of the Queen. She is a power unknown in our constitution, and an irresponsible agent that I will not recognise. Let her go back to the drawing-room, where all will bow to her.’

‘Hag!’ exclaimed Proserpine. ‘King of Hades, I, too, can appeal to you. Have I accepted your crown to be insulted by your subjects?’

‘A subject, may it please your Majesty, who has duties as strictly defined by our infernal constitution as those of your royal spouse; duties, too, which, let me tell you, madam, I and my order are resolved to perform.’

‘Gods of Olympus!’ cried Proserpine. ‘Is this to be a Queen?’

‘Before we proceed further in this discussion,’ said Lachesis, ‘I must move an inquiry into the conduct of his Excellency the Governor of the Gates. I move, then, that Cerberus be summoned.

Pluto started, and the blood rose to his dark cheek. ‘I have not yet had an opportunity of mentioning,’ said his Majesty, in a low tone, and with an air of considerable confusion, ‘that I have thought fit, as a reward for his past services, to promote Cerberus to the office of the Master of the Hounds. He therefore is no longer responsible.’

‘O-h!’ shrieked the Furies, as they elevated their hideous eyes.

‘The constitution has invested your Majesty with a power in the appointment of your Officers of State which your Majesty has undoubtedly a right to exercise,’ said Lachesis. ‘What degree of discretion it anticipated in the exercise, it is now unnecessary, and would be extremely disagreeable, to discuss. I shall not venture to inquire by what new influence your Majesty has been guided in the present instance. The consequence of your Majesty’s conduct is obvious, in the very difficult situation in which your realm is now placed. For myself and my colleagues, I have only to observe that we decline, under this crisis, any further responsibility; and the distaff and the shears are at your Majesty’s service the moment your Majesty may find convenient successors to the present holders. As a last favour, in addition to the many we are proud to remember we have received from your Majesty, we entreat that we may be relieved from their burthen as quickly as possible.’ (Loud cheers from the Eumenides.)

‘We had better recall Cerberus,’ said Pluto, alarmed, ‘and send this mortal about his business.’

‘Not without Eurydice. Oh! not without Eurydice,’ said the Queen.

‘Silence, Proserpine!’ said Pluto.

‘May it please your Majesty,’ said Lachesis, ‘I am doubtful whether we have the power of expelling anyone from Hades. It is not less the law that a mortal cannot remain here; and it is too notorious for me to mention the fact that none here have the power of inflicting death.’

‘Of what use are all your laws,’ exclaimed Proserpine, ‘if they are only to perplex us? As there are no statutes to guide us, it is obvious that the King’s will is supreme. Let Orpheus depart, then, with his bride.’

‘The latter suggestion is clearly illegal,’ said Lachesis.

‘Lachesis, and ye, her sisters,’ said Proserpine, ‘forget, I beseech you, any warm words that may have passed between us, and, as a personal favour to one who would willingly be your friend, release Eurydice. What! you shake your heads! Nay; of what importance can be a single miserable shade, and one, too, summoned so cruelly before her time, in these thickly-peopled regions?’

‘‘Tis the principle,’ said Lachesis; ‘‘tis the principle. Concession is ever fatal, however slight. Grant this demand; others, and greater, will quickly follow. Mercy becomes a precedent, and the realm is ruined.’

‘Ruined!’ echoed the Furies.

‘And I say preserved!’ exclaimed Proserpine with energy. ‘The State is in confusion, and you yourselves confess that you know not how to remedy it. Unable to suggest a course, follow mine. I am the advocate of mercy; I am the advocate of concession; and, as you despise all higher impulses, I meet you on your own grounds. I am their advocate for the sake of policy, of expediency.’

‘Never!’ said the Fates.

‘Never!’ shrieked the Furies.

‘What, then, will you do with Orpheus?’

The Parcæ shook their heads; even the Eumenides were silent.

‘Then you are unable to carry on the King’s government; for Orpheus must be disposed of; all agree to that. Pluto, reject these counsellors, at once insulting and incapable. Give me the distaff and the fatal shears. At once form a new Cabinet; and let the release of Orpheus and Eurydice be the basis of their policy.’ She threw her arms round his neck and whispered in his ear.

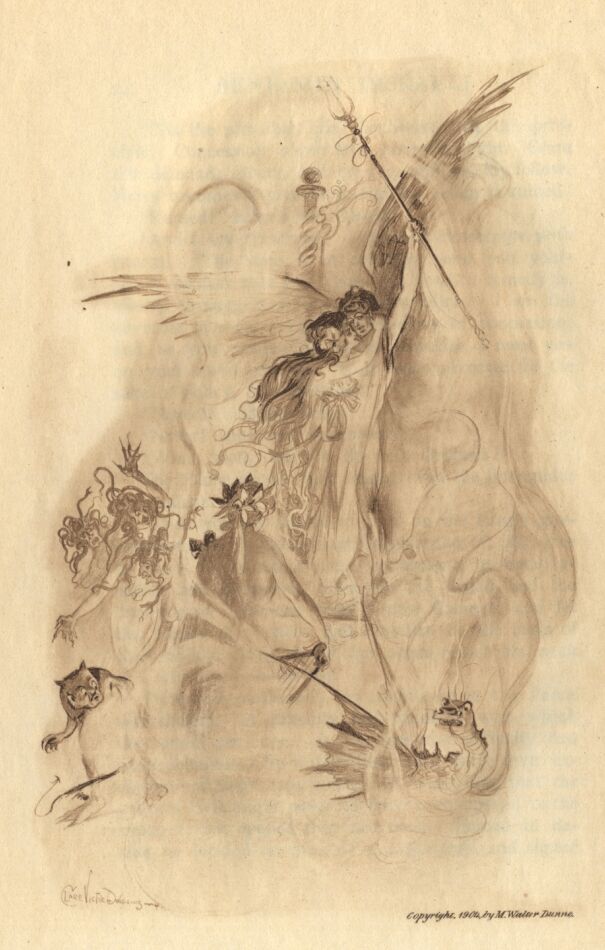

Pluto was perplexed; his confidence in the Parcae was shaken. A difficulty had occurred with which they could not cope. It was true the difficulty had been occasioned by a departure from their own exclusive and restrictive policy. It was clear that the gates of Hell ought never to have been opened to the stranger; but opened they had been. Forced to decide, he decided on the side of expediency, and signed a decree for the departure of Orpheus and Eurydice. The Parcas immediately resigned their posts, and the Furies walked off in a huff. Thus, on the third day of the Infernal Marriage, Pluto found that he had quarrelled with all his family, and that his ancient administration was broken up. The King was without a friend, and Hell was without a Government!

A Visit to Elysium

LET us change the scene from Hades to Olympus.

A chariot drawn by dragons hovered over that superb palace whose sparkling steps of lapislazuli were once pressed by the daring foot of Ixion. It descended into the beautiful gardens, and Ceres, stepping out, sought the presence of Jove.

‘Father of gods and men,’ said the majestic mother of Proserpine, ‘listen to a distracted parent! All my hopes were centred in my daughter, the daughter of whom you have deprived me. Is it for this that I endured the pangs of childbirth? Is it for this that I suckled her on this miserable bosom? Is it for this that I tended her girlish innocence, watched with vigilant fondness the development of her youthful mind, and cultured with a thousand graces and accomplishments her gifted and unrivalled promise? to lose her for ever!’

‘Beloved Bona Dea,’ replied Jove, ‘calm yourself!’

‘Jupiter, you forget that I am a mother.’

‘It is the recollection of that happy circumstance that alone should make you satisfied.’

‘Do you mock me? Where is my daughter?’

‘In the very situation you should desire. In her destiny all is fulfilled which the most affectionate mother could hope. What was the object of all your care and all her accomplishments? a good parti; and she has found one.’

‘To reign in Hell!’

‘“Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.” What! would you have had her a cup-bearer, like Hebe, or a messenger, like Hermes? Was the daughter of Jove and Ceres to be destined to a mere place in our household! Lady! she is the object of envy to half the goddesses. Bating our own bed, which she could not share, what lot more distinguished than hers? Recollect that goddesses, who desire a becoming match, have a very limited circle to elect from. Even Venus was obliged to put up with Vulcan. It will not do to be too nice. Thank your stars that she is not an old maid like Minerva.’

‘But Mars? he loved her.’

‘A young officer only with his half-pay, however good his connections, is surely not a proper mate for our daughter.’

‘Apollo?’

‘I have no opinion of a literary son-in-law. These scribblers are at present the fashion, and are very well to ask to dinner; but I confess a more intimate connection with them is not at all to my taste.’

‘I meet Apollo everywhere.’

‘The truth is, he is courted because every one is afraid of him. He is the editor of a daily journal, and under the pretence of throwing light upon every subject, brings a great many disagreeable things into notice, which is excessively inconvenient. Nobody likes to be paragraphed; and for my part I should only be too happy to extinguish the Sun and every other newspaper were it only in my power.’

‘But Pluto is so old, and so ugly, and, all agree, so ill-tempered.’

‘He has a splendid income, a magnificent estate; his settlements are worthy of his means. This ought to satisfy a mother; and his political influence is necessary to me, and this satisfies a father.’

‘But the heart——-’

‘As for that, she fancies she loves him; and whether she do or not, these feelings, we know, never last. Rest assured, my dear Ceres, that our girl has made a brilliant match, in spite of the gloomy atmosphere in which she has to reside.’

‘It must end in misery. I know Proserpine. I confess it with tears, she is a spoiled child.’

‘This may occasion Pluto many uneasy moments; but that is nothing to you or me. Between ourselves, I shall not be at all surprised if she plague his life out.’

‘But how can she consort with the Fates? How is it possible for her to associate with the Furies? She, who is used to the gayest and most amiable society in the world? Indeed, indeed, ‘tis an ill-assorted union!’

‘They are united, however; and, take my word for it, my dear madam, that you had better leave Pluto alone. The interference of a mother-in-law is proverbially never very felicitous.’

In the meantime affairs went on swimmingly in Tartarus. The obstinate Fates and the sulky Furies were unwittingly the cause of universal satisfaction. Everyone enjoyed himself, and enjoyment when it is unexpected is doubly satisfactory. Tantalus, Sisyphus, and Ixion, for the first time during their punishment, had an opportunity for a little conversation.

‘Long live our reforming Queen,’ said the ex-king of Lydia. ‘You cannot conceive, my dear companions, anything more delightful than this long-coveted draught of cold water; its flavour far surpasses the memory of my choicest wines. And as for this delicious fruit, one must live in a hot climate, like our present one, sufficiently to appreciate its refreshing gust. I would, my dear friends, you could only share my banquet.’

‘Your Majesty is very kind,’ replied Sisyphus, ‘but it seems to me that nothing in the world will ever induce me again to move. One must have toiled for ages to comprehend the rapturous sense of repose that now pervades my exhausted frame. Is it possible that that damned stone can really have disappeared?’

‘You say truly,’ said Ixion, ‘the couches of Olympus cannot compare with this resting wheel.’

‘Noble Sisyphus,’ rejoined Tantalus, ‘we are both of us acquainted with the cause of our companion’s presence in those infernal regions, since his daring exploit has had the good fortune of being celebrated by one of the fashionable authors of this part of the world.’

‘I have never had time to read his work,’ interrupted Ixion. ‘What sort of a fellow is he?’

‘One of the most conceited dogs that I ever met with,’ replied the King. ‘He thinks he is a great genius, and perhaps he has some little talent for the extravagant.’

‘Are there any critics in Hell?’

‘Myriads. They abound about the marshes of Cocytus, where they croak furiously. They are all to a man against our author.’

‘That speaks more to his credit than his own self-opinion,’ rejoined Ixion.

‘A nous moutons!’ exclaimed Tantalus; ‘I was about to observe that I am curious to learn for what reason our friend Sisyphus was doomed to his late terrible exertions.’

‘For the simplest in the world,’ replied the object of the inquiry; ‘because I was not a hypocrite. No one ever led a pleasanter life than myself, and no one was more popular in society. I was considered, as they phrased it, the most long-headed prince of my time, and was in truth a finished man of the world. I had not an acquaintance whom I had not taken in, and gods and men alike favoured me. In an unlucky moment, however, I offended the infernal deities, and it was then suddenly discovered that I was the most abandoned character of my age. You know the rest.’

‘You seem,’ exclaimed Tantalus, ‘to be relating my own history; for I myself led a reckless career with impunity, until some of the gods did me the honour of dining with me, and were dissatisfied with the repast. I am convinced myself that, provided a man frequent the temples, and observe with strictness the sacred festivals, such is the force of public opinion, that there is no crime which he may not commit without hazard.’

‘Long live hypocrisy!’ exclaimed Ixion. ‘It is not my forte. But if I began life anew, I would be more observant in my sacrifices.’

‘Who could have anticipated this wonderful revolution!’ exclaimed Sisyphus, stretching himself. ‘I wonder what will occur next! Perhaps we shall be all released.’

‘You say truly,’ said Ixion. ‘I am grateful to our reforming Queen; but I have no idea of stopping here. This cursed wheel indeed no longer whirls; but I confess my expectations will be much disappointed if I cannot free myself from these adamantine bonds that fix me to its orb.’

‘And one cannot drink water for ever,’ said Tantalus.

‘D—n all half measures,’ said Ixion. ‘We must proceed in this system of amelioration.’

‘Without doubt,’ responded his companion.

‘The Queen must have a party,’ continued the audacious lover of Juno. ‘The Fates and the Furies never can be conciliated. It is evident to me that she must fall unless she unbinds these chains of mine.’

‘And grants me full liberty of egress and regress,’ exclaimed Sisyphus.

‘And me a bottle of the finest golden wine of Lydia,’ said Tantalus.

The infernal honeymoon was over. A cloud appeared in the hitherto serene heaven of the royal lovers. Proserpine became unwell. A mysterious languor pervaded her frame; her accustomed hilarity deserted her. She gave up her daily rides; she never quitted the palace, scarcely her chamber. All day long she remained lying on a sofa, and whenever Pluto endeavoured to console her she went into hysterics. His Majesty was quite miserable, and the Fates and the Furies began to hold up their heads. The two court physicians could throw no light upon the complaint, which baffled all their remedies. These, indeed, were not numerous, for the two physicians possessed each only one idea. With one every complaint was nervous; the other traced everything to the liver. The name of the first was Dr. Blue-Devil; and of the other Dr. Blue-Pill. They were most eminent men.

Her Majesty, getting worse every day, Pluto, in despair, determined to send for Æsculapius. It was a long way to send for a physician; but then he was the most fashionable one in the world. He cared not how far he travelled to visit a patient, because he was paid by the mile; and it was calculated that his fee for quitting earth, and attending the Queen of Hell, would allow him to leave off business.

What a wise physician was Æsculapius! Physic was his abhorrence. He never was known, in the whole course of his practice, ever to have prescribed a single drug. He was a handsome man, with a flowing beard curiously perfumed, and a robe of the choicest purple. He twirled a cane of agate, round which was twined a serpent of precious stones, the gift of Juno, and he rode in a chariot drawn by horses of the Sun. When he visited Proserpine, he neither examined her tongue nor felt her pulse, but gave her an account of a fancy ball which he had attended the last evening he passed on terra firma. His details were so interesting that the Queen soon felt better. The next day he renewed his visit, and gave her an account of a new singer that had appeared at Ephesus. The effect of this recital was so satisfactory, that a bulletin in the evening announced that the Queen was convalescent. The third day Æsculapius took his departure, having previously enjoined change of scene for her Majesty, and a visit to the Elysian Fields!

‘Heh, heh!’ shrieked Tisiphone.

‘Hah, hah!’ squeaked Megæra.

‘Hoh, hoh!’ moaned Alecto.

‘Now or never,’ said the infernal sisters. ‘There is a decided reaction. The moment she embarks, unquestionably we will flare up.’ So they ran off to the Fates.

‘We must be prudent,’ said Clotho.

‘Our time is not come,’ remarked Lachesis.

‘I wish the reaction was more decided,’ said Atropos; ‘but it is a great thing that they are going to be parted, for the King must remain.’

The opposition party, although aiming at the same result, was therefore evidently divided as to the means by which it was to be obtained. The sanguine Furies were for fighting it out at once, and talked bravely of the strong conservative spirit only dormant in Tartarus. Even the Radicals themselves are dissatisfied: Tantalus is no longer contented with water, or Ixion with repose. But the circumspect Fates felt that a false step at present could never be regained. They talked, therefore, of watching events. Both divisions, however, agreed that the royal embarkation was to be the signal for renewed intrigues and renovated exertions.

When Proserpine was assured that she must be parted for a time from Pluto, she was inconsolable. They passed the night in sorrowful embraces. She vowed that she could not live a day without him, and that she certainly should die before she reached the first post. The mighty heart of the King of Hades was torn to pieces with contending emotions. In the agony of his overwhelming passion the security of his realm seemed of secondary importance compared with the happiness of his wife. Fear and hatred of the Parcæ and the Eumenides equalled, however, in the breast of Proserpine, her affection for her husband. The consciousness that his absence would be a signal for a revolution, and that the crown of Tartarus might be lost to her expected offspring, animated her with a spirit of heroism. She reconciled herself to the terrible separation, on condition that Pluto wrote to her every day.

‘Adieu! my best, my only beloved!’ ejaculated the unhappy Queen; ‘do not forget me for a moment; and let nothing in the world induce you to speak to any of those horrid people. I know them; I know exactly what they will be at: the moment I am gone they will commence their intrigues for the restoration of the reign of doom and torture. Do not listen to them, my Pluto. Sooner than have recourse to them, seek assistance from their former victims.’

‘Calm yourself, my Proserpine. Anticipate no evil. I shall be firm; do not doubt me. I will cling with tenacity to that juste milieu under which we have hitherto so eminently prospered. Neither the Parcæ and the Eumenides, nor Ixion and his friends, shall advance a point. I will keep each faction in awe by the bugbear of the other’s supremacy. Trust me, I am a profound politician.’

It was determined that the progress of Proserpine to the Elysian Fields should be celebrated with a pomp and magnificence becoming her exalted station. The day of her departure was proclaimed as a high festival in Hell. Tiresias, absent on a secret mission, had been summoned back by Pluto, and appointed to attend her Majesty during her journey and her visit, for Pluto had the greatest confidence in his discretion. Besides, as her Majesty had not at present the advantage of any female society, it was necessary that she should be amused; and Tiresias, though old, ugly, and blind, was a wit as well as a philosopher, the most distinguished diplomatist of his age, and considered the best company in Hades.

An immense crowd was assembled round the gates of the palace on the morn of the royal departure. With what anxious curiosity did they watch those huge brazen portals! Every precaution was taken for the accommodation of the public. The streets were lined with troops of extraordinary stature, whose nodding plumes prevented the multitude from catching a glimpse of anything that passed, and who cracked the skulls of the populace with their scimitars if they attempted in the slightest degree to break the line. Moreover, there were seats erected which any one might occupy at a reasonable rate; but the lord steward, who had the disposal of the tickets, purchased them all for himself, and then resold them to his fellow-subjects at an enormous price.

At length the hinges of the gigantic portals gave an ominous creak, and, amid the huzzas of men and the shrieks of women, the procession commenced.

First came the infernal band. It consisted of five hundred performers, mounted on different animals. Never was such a melodious blast. Fifty trumpeters, mounted on zebras of all possible stripes and tints, and working away at huge ramshorns with their cheeks like pumpkins. Then there were bassoons mounted on bears, clarionets on camelopards, oboes on unicorns, and troops of musicians on elephants, playing on real serpents, whose prismatic bodies indulged in the most extraordinary convolutions imaginable, and whose arrowy tongues glittered with superb agitation at the exquisite sounds which they unintentionally delivered. Animals there were, too, now unknown and forgotten; but I must not forget the fellow who beat the kettledrums, mounted on an enormous mammoth, and the din of whose reverberating blows would have deadened the thunder of Olympus.

This enchanting harmony preceded the regiment of Proserpine’s own guards, glowing in adamantine armour and mounted on coal-black steeds. Their helmets were quite awful, and surmounted by plumes plucked from the wings of the Harpies, which were alone enough to terrify an earthly host. It was droll to observe this troop of gigantic heroes commanded by infants, who, however, were arrayed in a similar costume, though, of course, on a smaller scale. But such was the admirable discipline of the infernal forces, that, though lions to their enemies, they were Iambs to their friends; and on the present occasion their colonel was carried in a cradle.

After these came twelve most worshipful baboons, in most venerable wigs. They were clothed with scarlet robes lined with ermine, and ornamented with gold chains, and mounted on the most obstinate and inflexible mules in Tartarus. These were the judges. Each was provided with a pannier of choice cobnuts, which he cracked with great gravity, throwing the shells to the multitude, an infernal ceremony, there held emblematic of their profession.

The Lord Chancellor came next in a grand car. Although his wig was even longer than those of his fellow functionaries, his manners and the rest of his costume afforded a strange contrast to them. Apparently never was such a droll, lively fellow. His dress was something between that of Harlequin and Scaramouch. He amused himself by keeping in the air four brazen balls at the same time, swallowing daggers, spitting fire, turning sugar into salt, and eating yards of pink ribbon, which, after being well digested, re-appeared through his nose. It is unnecessary to add, after this, that he was the most popular Lord Chancellor that had ever held the seals, and was received with loud and enthusiastic cheers, which apparently repaid him for all his exertions. Notwithstanding his numerous and curious occupations, I should not omit to add that his Lordship, nevertheless, found time to lead by the nose a most meek and milk-white jackass that immediately followed him, and which, in spite of the remarkable length of its ears, seemed the object of great veneration. There was evidently some mystery about this animal difficult to penetrate. Among other characteristics, it was said, at different seasons, to be distinguished by different titles; for sometimes it was styled ‘The Public,’ at others ‘Opinion,’ and occasionally was saluted as the ‘King’s Conscience.’

Now came a numerous company of Priests, in flowing and funereal robes, bearing banners, inscribed with the various titles of their Queen; on some was inscribed Hecate, on others Juno Inferna, on others Theogamia, Libera on some, on others Cotytto. Those that bore banners were crowned with wreaths of narcissus, and mounted on bulls blacker than night, and of a severe and melancholy aspect. Others walked by their side, bearing branches of cypress.

And here I must stop to notice a droll characteristic of the priestly economy of Hades. To be a good pedestrian was considered an essential virtue of an infernal clergyman; but to be mounted on a black bull was the highest distinction of the craft. It followed, therefore, that, originally, promotion to such a seat was the natural reward of any priest who had distinguished himself in the humbler career of a good walker; but in process of time, as even infernal as well as human institutions are alike liable to corruption, the black bulls became too often occupied by the halt and the crippled, the feeble and the paralytic, who used their influence at Court to become thus exempted from the performance of the severer duties of which they were incapable. This violation of the priestly constitution excited at first great murmurs among the abler but less influential brethren. But the murmurs of the weak prove only the tyranny of the strong; and so completely in the course of time do institutions depart from their original character, that the imbecile riders of the black bulls now avowedly defended their position on the very grounds which originally should have unseated them, and openly maintained that it was very evident that the stout were intended to walk, and the feeble to be carried.

The priests were followed by fifty dark chariots, drawn by blue satyrs. Herein was the wardrobe of the Queen, and her Majesty’s cooks.

Tiresias came next, in a basalt chariot, yoked to royal steeds. He was attended by Manto, who shared his confidence, and who, some said, was his daughter, and others his niece. Venerable seer! Who could behold that flowing beard, and the thin grey hairs of that lofty and wrinkled brow, without being filled with sensations of awe and affection? A smile of bland benignity played upon his passionless and reverend countenance. Fortunate the monarch who is blessed with such a counsellor! Who could have supposed that all this time Tiresias was concocting an epigram on Pluto!

The Queen! The Queen!

Upon a superb throne, placed upon an immense car, and drawn by twelve coal-black steeds, four abreast, reposed the royal daughter of Ceres. Her rich dark hair was braided off her high pale forehead, and fell in voluptuous clusters over her back. A tiara sculptured out of a single brilliant, and which darted a flash like lightning on the surrounding multitude, was placed somewhat negligently on the right side of her head; but no jewels broke the entrancing swell of her swan-like neck, or were dimmed by the lustre of her ravishing arms. How fair was the Queen of Hell! How thrilling the solemn lustre of her violet eye! A robe, purple as the last hour of twilight, encompassed her transcendent form, studded with golden stars!

Through the dim hot streets of Tartarus moved the royal procession, until it reached the first winding of the river Styx. Here an immense assemblage of yachts and barges, dressed out with the infernal colours, denoted the appointed spot of the royal embarkation. Tiresias, dismounting from his chariot, and leaning on Manto, now approached her Majesty, and requesting her royal commands, recommended her to lose no time in getting on board.

‘When your Majesty is once on the Styx,’ observed the wily seer, ‘it may be somewhat difficult to recall you to Hades; but I know very little of Clotho, may it please your Majesty, if she have not already commenced her intrigues in Tartarus.’

‘You alarm me!’ said Proserpine.

‘It was not my intention. Caution is not fear.’

‘But do you think that Pluto———’

‘May it please your Majesty, I make it a rule never to think. I know too much.’

‘Let us embark immediately!’

‘Certainly; I would recommend your Majesty to get off at once. Myself and Manto will accompany you, and the cooks. If an order arrive to stay our departure, we can then send back the priests.’

‘You counsel well, Tiresias. I wish you had not been absent on my arrival. Affairs might have gone better.’

‘Not at all. Had I been in Hell, your enemies would have been more wary. Your Majesty’s excellent spirit carried you through triumphantly; but it will not do so twice. You turned them out, and I must keep them out.’

‘So be it, my dear friend.’ Thus saying, the Queen descended her throne, and leaving the rest of her retinue to follow with all possible despatch, embarked on board the infernal yacht, with Tiresias, Manto, the chief cook, and some chosen attendants, and bid adieu for the first time, not without agitation, to the gloomy banks of Tartarus.

The breeze was favourable, and, animated by the exhortations of Tiresias, the crew exerted themselves to the utmost. The barque swiftly scudded over the dark waters. The river was of great breadth, and in this dim region the crew were soon out of sight of land.

‘You have been in Elysium?’ inquired Proserpine of Tiresias.

‘I have been everywhere,’ replied the seer, ‘and though I am blind have managed to see a great deal more than my fellows.’

‘I have often heard of you,’ said the Queen, ‘and I confess that yours is a career which has much interested me. What vicissitudes in affairs have you not witnessed! And yet you have somehow or other contrived to make your way through all the storms in which others have sunk, and are now, as you always have been, in an exalted position. What can be your magic? I would that you would initiate me. I know that you are a prophet, and that even the gods consult you.’

‘Your Majesty is complimentary. I certainly have had a great deal of experience. My life has no doubt been a long one, but I have made it longer by never losing a moment. I was born, too, at a great crisis in affairs. Everything that took place before the Trojan war passes for nothing in the annals of wisdom. That was a great revolution in all affairs human and divine, and from that event we must now date all our knowledge. Before the Trojan war we used to talk of the rebellion of the Titans, but that business now is an old almanac. As for my powers of prophecy, believe me, that those who understand the past are very well qualified to predict the future. For my success in life, it may be principally ascribed to the observance of a simple rule—I never trust anyone, either god or man. I make an exception in favour of the goddesses, and especially of your Majesty,’ added Tiresias, who piqued himself on his gallantry.

While they were thus conversing, the Queen directed the attention of Manto to a mountainous elevation which now began to rise in the distance, and which, from the rapidity of the tide and the freshness of the breeze, they approached at a swift rate.

‘Behold the Stygian mountains,’ replied Manto. ‘Through their centre runs the passage of Night which leads to the regions of Twilight.’

‘We have, then, far to travel?’

‘Assuredly it is no easy task to escape from the gloom of Tartarus to the sunbeams of Elysium,’ remarked Tiresias; ‘but the pleasant is generally difficult; let us be grateful that in our instance it is not, as usual, forbidden.’

‘You say truly; I am sorry to confess how very often it appears to me that sin is enjoyment. But see! how awful are these perpendicular heights, piercing the descending vapours, with their peaks clothed with dark pines! We seem land-locked.’

But the experienced master of the infernal yacht knew well how to steer his charge through the intricate windings of the river, which here, though deep and navigable, became as wild and narrow as a mountain stream; and, as the tide no longer served them, and the wind, from their involved course, was as often against them as in their favour, the crew were obliged to have recourse to their oars, and rowed along until they arrived at the mouth of an enormous cavern, from which the rapid stream apparently issued.

‘I am frightened out of my wits,’ exclaimed Proserpine. ‘Surely this cannot be our course?’

‘I hold, from your Majesty’s exclamation,’ said Tiresias, ‘that we have arrived at the passage of Night. When we have proceeded some hundred yards, we shall reach the adamantine portals. I pray your Majesty be not alarmed. I alone have the signet which can force these mystic gates to open. I must be stirring myself. What, ho! Manto.’

‘Here am I, father. Hast thou the seal?’

‘In my breast. I would not trust it to my secretaries. They have my portfolios full of secret despatches, written on purpose to deceive them; for I know that they are spies in the pay of Minerva; but your Majesty perceives, with a little prudence, that even a traitor may be turned to account.’

Thus saying, Tiresias, leaning on Manto, hobbled to the poop of the vessel, and exclaiming aloud, ‘Behold the mighty seal of Dis, whereon is inscribed the word the Titans fear,’ the gates immediately flew open, revealing the gigantic form of the Titan Porphyrin, whose head touched the vault of the mighty cavern, although he was up to his waist in the waters of the river.

‘Come, my noble Porphyrion,’ said Tiresias, ‘bestir thyself, I beseech thee. I have brought thee a Queen. Guide her Majesty, I entreat thee, with safety through this awful passage of Night.’

‘What a horrible creature,’ whispered Proserpine. ‘I wonder you address him with such courtesy.’

‘I am always courteous,’ replied Tiresias. ‘How know I that the Titans may not yet regain their lost heritage? They are terrible fellows; and ugly or not, I have no doubt that even your Majesty would not find them so ill-favoured were they seated in the halls of Olympus.’

‘There is something in that,’ replied Proserpine. ‘I almost wish I were once more in Tartarus.’

The Titan Porphyrion in the meantime had fastened a chain-cable to the vessel, which he placed over his shoulder, and turning his back to the crew, then wading through the waters, he dragged on the vessel in its course. The cavern widened, the waters spread. To the joy of Proserpine, apparently, she once more beheld the moon and stars.

‘Bright crescent of Diana!’ exclaimed the enraptured Queen, ‘and ye too, sweet stars, that I have so often watched on the Sicilian plains; do I, then, indeed again behold you? or is it only some exquisite vision that entrances my being? for, indeed, I do not feel the freshness of that breeze that was wont to renovate my languid frame; nor does the odorous scent of flowers wafted from the shores delight my jaded senses. What is it? Is it life or death; earth, indeed, or Hell?’

‘‘Tis nothing,’ said Tiresias, ‘but a great toy. You must know that Saturn—until at length, wearied by his ruinous experiments, the gods expelled him his empire—was a great dabbler in systems. He was always for making moons brighter than Diana, and lighting the stars by gas; but his systems never worked. The tides rebelled against their mistress, and the stars went out with a horrible stench. This is one of his creations, the most ingenious, though a failure. Jove made it a present to Pluto, who is quite proud of having a sun and stars of his own, and reckons it among the choice treasures of his kingdoms.’

‘Poor Saturn! I pity him; he meant well.’ ‘Very true. He is the paviour of the high-street of Hades. But we cannot afford kings, and especially Gods, to be philosophers. The certainty of misrule is better than the chance of good government; uncertainty makes people restless.’

‘I feel very restless myself; I wish we were in Elysium!’

‘The river again narrows!’ exclaimed Manto. ‘There is no other portal to pass. The Saturnian moon and stars grow fainter, there is a grey tint expanding in the distance; ‘tis the realm of Twilight; your Majesty will soon disembark.’

Containing an Account of Tiresias at His Rubber

TRAVELLERS who have left their homes generally grow mournful as the evening draws on; nor is there, perhaps, any time at which the pensive influence of twilight is more predominant than on the eve that follows a separation from those we love. Imagine, then, the feelings of the Queen of Hell, as her barque entered the very region of that mystic light, and the shadowy shores of the realm of Twilight opened before her. Her thoughts reverted to Pluto; and she mused over all his fondness, all his adoration, and all his indulgence, and the infinite solicitude of his affectionate heart, until the tears trickled down her beautiful cheeks, and she marvelled she ever could have quitted the arms of her lover.

‘Your Majesty,’ observed Manto, who had been whispering to Tiresias, ‘feels, perhaps, a little wearied?’

‘By no means, my kind Manto,’ replied Proserpine, starting from her reverie. ‘But the truth is, my spirits are unequal; and though I really cannot well fix upon the cause of their present depression, I am apparently not free from the contagion of the surrounding gloom.’

‘It is the evening air,’ said Tiresias. ‘Your Majesty had perhaps better re-enter the pavilion of the yacht. As for myself, I never venture about after sunset. One grows romantic. Night was evidently made for in-door nature. I propose a rubber.’

To this popular suggestion Proserpine was pleased to accede, and herself and Tiresias, Manto and the captain of the yacht, were soon engaged at the proposed amusement.

Tiresias loved a rubber. It was true he was blind, but then, being a prophet, that did not signify. Tiresias, I say, loved a rubber, and was a first-rate player, though, perhaps, given a little too much to finesse. Indeed, he so much enjoyed taking in his fellow-creatures, that he sometimes could not resist deceiving his own partner. Whist is a game which requires no ordinary combination of qualities; at the same time, memory and invention, a daring fancy, and a cool head. To a mind like that of Tiresias, a pack of cards was full of human nature. A rubber was a microcosm; and he ruffed his adversary’s king, or brought in a long suit of his own with as much dexterity and as much enjoyment as, in the real business of existence, he dethroned a monarch, or introduced a dynasty.

‘Will your Majesty be pleased to draw your card?’ requested the sage. ‘If I might venture to offer your Majesty a hint, I would dare to recommend your Majesty not to play before your turn. My friends are fond of ascribing my success in my various missions to the possession of peculiar qualities. No such thing: I owe everything to the simple habit of always waiting till it is my turn to speak. And believe me, that he who plays before his turn at whist, commits as great a blunder as he who speaks before his turn during a negotiation.’

‘The trick, and two by honours,’ said Proserpine. ‘Pray, my dear Tiresias, you who are such a fine player, how came you to trump my best card?’

‘Because I wanted the lead. And those who want to lead, please your Majesty, must never hesitate about sacrificing their friends.’

‘I believe you speak truly. I was right in playing that thirteenth card?’

‘Quite so. Above all things, I love a thirteenth card. I send it forth, like a mock project in a revolution, to try the strength of parties.’

‘You should not have forced me, Lady Manto,’ said the Captain of the yacht, in a grumbling tone, to his partner. ‘By weakening me, you prevented me bringing in my spades. We might have made the game.’

‘You should not have been forced,’ said Tiresias. ‘If she made a mistake, who was unacquainted with your plans, what a terrible blunder you committed to share her error without her ignorance!’

‘What, then, was I to lose a trick?’

‘Next to knowing when to seize an opportunity,’ replied Tiresias, ‘the most important thing in life is to know when to forego an advantage.’

‘I have cut you an honour, sir,’ said Manto.

‘Which reminds me,’ replied Tiresias, ‘that, in the last hand, your Majesty unfortunately forgot to lead through your adversary’s ace. I have often observed that nothing ever perplexes an adversary so much as an appeal to his honour.’

‘I will not forget to follow your advice,’ said the Captain of the yacht, playing accordingly.

‘By which you have lost the game,’ quietly remarked Tiresias. ‘There are exceptions to all rules, but it seldom answers to follow the advice of an opponent.’

‘Confusion!’ exclaimed the Captain of the yacht.

‘Four by honours, and the trick, I declare,’ said Proserpine. ‘I was so glad to see you turn up the queen, Tiresias.’

‘I also, madam. Without doubt there are few cards better than her royal consort, or, still more, the imperial ace. Nevertheless, I must confess, I am perfectly satisfied whenever I remember that I have the Queen on my side.’

Proserpine bowed.

‘I have a good mind to do it, Tiresias,’ said Queen Proserpine, as that worthy sage paid his compliments to her at her toilet, at an hour which should have been noon.

‘It would be a great compliment,’ said Tiresias.

‘And it is not much out of our way?’

‘By no means,’ replied the seer. ‘‘Tis an agreeable half-way house. He lives in good style.’

‘And whence can a dethroned monarch gain a revenue?’ inquired the Queen.

‘Your Majesty, I see, is not at all learned in politics. A sovereign never knows what an easy income is till he has abdicated. He generally commences squabbling with his subjects about the supplies; he is then expelled, and voted, as compensation, an amount about double the sum which was the cause of the original quarrel.’

‘What do you think, Manto?’ said Proserpine, as that lady entered the cabin; ‘we propose paying a visit to Saturn. He has fixed his residence, you know, in these regions of twilight.’

‘I love a junket,’ replied Manto, ‘above all things. And, indeed, I was half frightened out of my wits at the bare idea of toiling over this desert. All is prepared, please your Majesty, for our landing. Your Majesty’s litter is quite ready.’

‘‘Tis well,’ said Proserpine; and leaning on the arm of Manto, the Queen came upon deck, and surveyed the surrounding country, a vast grey flat, with a cloudless sky of the same tint: in the distance some lowering shadows, which seemed like clouds but were in fact mountains.

‘Some half-dozen hours,’ said Tiresias, ‘will bring us to the palace of Saturn. We shall arrive for dinner; the right hour. Let me recommend your Majesty to order the curtains of your litter to be drawn, and, if possible, to resume your dreams.’

‘They were not pleasant,’ said Proserpine, ‘I dreamt of my mother and the Parcæ. Manto, methinks I’ll read. Hast thou some book?’

‘Here is a poem, Madam, but I fear it may induce those very slumbers you dread.’

‘How call you it?’

‘“The Pleasures of Oblivion.” The poet apparently is fond of his subject.’

‘And is, I have no doubt, equal to it. Hast any prose?’

‘An historical novel or so.’

‘Oh! if you mean those things as full of costume as a fancy ball, and almost as devoid of sense, I’ll have none of them. Close the curtains; even visions of the Furies are preferable to these insipidities.’

The halt of the litter roused the Queen from her slumbers. ‘We have arrived,’ said Manto, as she assisted in withdrawing the curtains.

The train had halted before a vast propylon of rose-coloured granite. The gate was nearly two hundred feet in height, and the sides of the propylon, which rose like huge moles, were sculptured with colossal figures of a threatening aspect. Passing through the propylon, the Queen of Hell and her attendants entered an avenue in length about three-quarters of a mile, formed of colossal figures of the same character and substance, alternately raising in their arms javelins or battle-axes, as if about to strike. At the end of this heroic avenue appeared the palace of Saturn. Ascending a hundred steps of black marble, you stood before a portico supported by twenty columns of the same material and shading a single portal of bronze. Apparently the palace formed an immense quadrangle; a vast tower rising from each corner, and springing from the centre a huge and hooded dome. A crowd of attendants, in grey and sad-coloured raiment, issued from the portal of the palace at the approach of Proserpine, who remarked with strange surprise their singular countenances and demeanour; for rare in this silent assemblage was any visage resembling aught she had seen, human or divine. Some bore the heads of bats; of owls and beetles others; some fluttered moth-like wings, while the shoulders of other bipeds were surmounted, in spite of their human organisation, with the heads of rats and weasels, of marten-cats and of foxes. But they were all remarkably civil; and Proserpine, who was now used to wonders, did not shriek at all, and scarcely shuddered.

The Queen of Hell was ushered through a superb hall, and down a splendid gallery, to a suite of apartments where a body of damsels of a most distinguished appearance awaited her. Their heads resembled those of the most eagerly-sought, highly-prized, and oftenest-stolen lap-dogs. Upon the shoulders of one was the visage of the smallest and most thorough-bred little Blenheim in the world. Upon her front was a white star, her nose was nearly flat, and her ears were tied under her chin, with the most jaunty air imaginable. She was an evident flirt; and a solemn prude of a spaniel, with a black and tan countenance, who seemed a sort of duenna, evidently watched her with no little distrust. The admirers of blonde beauties would, however, have fallen in love with a poodle, with the finest head of hair imaginable, and most voluptuous shoulders. This brilliant band began barking in the most insinuating tone on the appearance of the Queen; and Manto, who was almost as dexterous a linguist as Tiresias himself, informed her Majesty that these were the ladies of her bed-chamber; upon which Proserpine, who, it will be remembered had no passion for dogs, ordered them immediately out of her room.

‘What a droll place!’ exclaimed the Queen. ‘Do you know, we are later than I imagined? A hasty toilet to-day; I long to see Saturn. It is droll, I am hungry. My purple velvet, I think; it may be considered a compliment. No diamonds, only jet; a pearl or two, perhaps. Didst ever see the King?

They say he is gentlemanlike, though a bigot. No! no rouge to-day; this paleness is quite apropos. Were I as radiant as usual, I should be taken for Aurora.’

So leaning on Manto, and preceded by the ladies of her bed-chamber, whom, notwithstanding their repulse, she found in due attendance in the antechamber, Proserpine again continued her progress down the gallery, until they stopped at a door, which opening, she was ushered into the grand circular saloon, crowned by the dome, whose exterior the Queen had already observed. The interior of this apartment was entirely of black and grey marble, with the exception of the dome itself, which was of ebony, richly carved and supported by more than a hundred columns. There depended from the centre of the arch a single chandelier of frosted silver, which was itself as big as an ordinary chamber, but of the most elegant form, and delicate and fantastic workmanship. As the Queen entered the saloon, a personage of venerable appearance, dressed in a suit of black velvet, and leaning on an ivory cane, advanced to salute her. There was no mistaking this personage; his manners were at once so courteous and so dignified. He was clearly their host; and Proserpine, who was quite charmed with his grey locks and his black velvet cap, his truly paternal air, and the beneficence of his unstudied smile, could scarcely refrain from bending her knee, and pressing her lips to his extended hand.

‘I am proud that your Majesty has remembered me in my retirement,’ said Saturn, as he led Proserpine to a seat.

Their mutual compliments were soon disturbed by the announcement of dinner, and Saturn offering his arm to the Queen with an air of politeness which belonged to the old school, but which the ladies admire in old men, handed Proserpine to the banqueting-room. They were followed by some of the principal personages of her Majesty’s suite, and a couple of young Titans, who enjoyed the posts of aides-de-camp to the ex-King, and whose duties consisted of carving at dinner.

It was a most agreeable dinner, and Proserpine was delighted with Saturn, who, of course, sat by her side, and paid her every possible attention. Saturn, whose manners, as has been observed, were of the old school, loved a good story, and told several. His anecdotes, especially of society previous to the Trojan war, were highly interesting. There ran through all his behaviour, too, a tone of high breeding and of consideration for others which was really charming; and Proserpine, who had expected to find in her host a gloomy bigot, was quite surprised at the truly liberal spirit with which he seemed to consider affairs in general. Indeed this unexpected tone made so great an impression upon her, that finding a good opportunity after dinner, when they were sipping their coffee apart from the rest of the company, she could not refrain from entering into some conversation with the ex-King upon the subject, and the conversation ran thus:

‘Do you know,’ said Proserpine, ‘that much as I have been pleased and surprised during my visit to the realms of twilight, nothing has pleased, and I am sure nothing has surprised me more, than to observe the remarkably liberal spirit in which your Majesty views the affairs of the day.’

‘You give me a title, beautiful Proserpine, to which I have no claim,’ replied Saturn. ‘You forget that I am now only Count Hesperus; I am no longer a king, and believe me, I am very glad of it.’

‘What a pity, my dear sir, that you would not condescend to conform to the spirit of the age. For myself, I am quite a reformer.’

‘So I have understood, beautiful Proserpine, which I confess has a little surprised me; for to tell you the truth, I do not consider that reform is exactly our trade.’

‘Affairs cannot go on as they used,’ observed Proserpine, oracularly; ‘we must bow to the spirit of the age.’

‘And what is that?’ inquired Saturn.

‘I do not exactly know,’ replied Proserpine, ‘but one hears of it everywhere.’

‘I also heard of it a great deal,’ replied Saturn, ‘and was also recommended to conform to it. Before doing so, however, I thought it as well to ascertain its nature, and something also of its strength.’

‘It is terribly strong,’ observed Proserpine.

‘But you think it will be stronger?’ inquired the ex-King.

‘Certainly; every day it is more powerful.’

‘Then if, on consideration, we were to deem resistance to it advisable, it is surely better to commence the contest at once than to postpone the struggle.’

‘It is useless to talk of resisting; one must conform.’

‘I certainly should consider resistance useless,’ replied Saturn, ‘for I tried it and failed; but at least one has a chance of success; and yet, having resisted this spirit and failed, I should not consider myself in a worse plight than you would voluntarily place yourself in by conforming to it.’

‘You speak riddles,’ said Proserpine.

‘To be plain, then,’ replied Saturn, ‘I think you may as well at once give up your throne, as conform to this spirit.’

‘And why so?’ inquired Proserpine very ingenuously.’