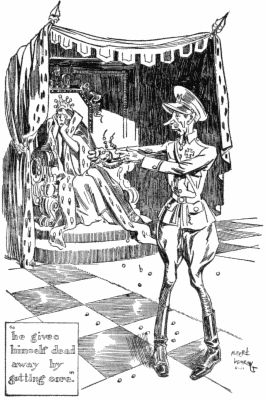

"he gives himself dead away by getting sore."

Title: Potash and Perlmutter Settle Things

Author: Montague Glass

Release date: November 28, 2006 [eBook #19948]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Books by

MONTAGUE GLASS

POTASH AND PERLMUTTER SETTLE THINGS

WORRYING WON'T WIN

HARPER & BROTHERS NEW YORK

[Established 1817]

"he gives

himself dead

away by

getting sore."

by

MONTAGUE GLASS

Author of "Worrying Won't Win"

Harper & Brothers Publishers

New York and London

Potash and Perlmutter Settle Things

Copyright, 1919, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

Published September, 1919

"Nu, what's the matter now?" Morris Perlmutter asked, as he entered the office one morning after the cessation of hostilities on the western front.

"Ai, tzuris!" Abe moaned in reply, and for at least a minute he continued to rock to and fro in his chair and to make incoherent noises through his nostrils in the manner of a person suffering either from toothache or the recent cancelation of a large order.

"It serves you right," Morris said. "I told you you shouldn't eat that liberty roast at Wasserbauer's yesterday. It used to give you the indigestion when it was known as Koenigsburger Klops, which it is like the German Empire now calling itself the German Republic; changing its name ain't going to alter its poisonous disposition none."[Pg 2]

"That's right!" Abe said. "Make jokes, why don't you? You are worser as this here feller Zero."

"What feller Zero?" Morris demanded.

"Zero the emperor what fiddled when Rome was burning," Abe replied. "He's got nothing on you. You would fiddle if Rome, Watertown, and Ogdensburg was burning."

"I don't know what you are talking about at all," Morris said. "And, besides, the feller's name was Nero, not Zero."

"That's what you say," Abe commented, "which you also said that the operators was only bluffing and that they wouldn't strike on us in a thousand years, and considering that you said this only yesterday, Mawruss, it's already wonderful how time flies."

"Well," Morris said, "how could I figure that them lunatics is going to pick out the time when we've got practically no work for them and was going to fire them, anyway, to call a strike on us?"

"You should ought to have figured that way," Abe declared. "Didn't the Kaiser abdicate just before them Germans got ready to kick him out?"

"The king business ain't the garment business," Morris observed.

"I know it ain't," Abe agreed. "Kings has got their worries, too, but when it comes to laying awake nights trying to figure out whether them designers somewheres in France is going to turn out long, full skirts or short, narrow skirts for the[Pg 3] fall and winter of nineteen-nineteen and nineteen-twenty, Mawruss, I bet yer the entire collection of kings, active or retired, doesn't got to take two grains of trional between them."

"If everybody worried like you do, Abe," Morris said, "the government would got to issue sleeping-powder cards like sugar cards and limit the consumption of sleeping-powders to not more than two pounds of sleeping-powders per person per month in each household."

"Well, some one has got to do the worrying around here, Mawruss," Abe said, "which if it rested with you, y'understand, we could make up a line of samples for next season that wouldn't be no more like Paris designs than General Pershing looks like his pictures in the magazines."

"Say, for that matter," Morris said, "we are just as good guessers as our competitors; on account the way things is going nowadays, nobody is going to try to make a trip to Paris to get fashion designs, because if he figured on crossing the ocean to buy model gowns for the fall and winter of nineteen-nineteen and nineteen-twenty, y'understand, between the time that he applied for his passport and the time the government issued it to him, y'understand, it would already be the spring and summer season of nineteen-twenty-four and nineteen-twenty-five. So the best thing we could do is to snoop round among the trade, and whatever we find the majority is making up for next year, we would make up the same styles also, and that's all there would be to it."[Pg 4]

"We wouldn't do nothing of the kind," Abe declared. "I've been thinking this thing over, and I come to the conclusion that it's up to you to go over to Paris and see what is going on over there."

"I don't got to go to Paris for that, Abe," Morris said. "I can read the papers the same like anybody else, and just so long as there is a chance that the war would start up again and them hundred-mile guns is going to resume operations, I am content to get my ideas of Paris styles at a distance of three thousand miles if I never sold another garment as long as I live."

"But when it was working yet, it only went off every twenty minutes," Abe said.

"I don't care if it went off every Fourth of July," Morris said, "because if I went over there it would be just my luck that the peace nogotiations falls through and the Germans invent a gun leaving Frankfort ever hour on the hour and arriving in Paris daily, including Sundays, without leaving enough trace of me to file a proof of death with. Am I right or wrong?"

"All right," Abe said. "If that's the way you feel about it, I will go to Paris."

"You will go to Paris?" Morris exclaimed.

"Sure!" Abe declared. "The operators is on strike, business is rotten, and I'm sick and tired of paying life-insurance premiums, anyway. Besides, if Leon Sammet could get a passport, why couldn't I?"

"You mean to say that faker is going to Paris to buy model gowns?" Morris demanded.[Pg 5]

"I seen him on the Subway this morning, and the way he talked about how easy he got his passport, you would think that every time he was in Washington with a line of them masquerade costumes which Sammet Brothers makes up, if he didn't stop in and take anyhow a bit of lunch with the Wilsons, y'understand, the President raises the devil with Tumulty why didn't he let him know Leon Sammet was in town."

"Then that settles it," Morris declared, reaching for his hat.

"Where are you going?" Abe asked.

"I am going straight down to see Henry D. Feldman and tell that crook he should get for me a passport," Morris said.

"You wouldn't positively do nothing of the kind," Abe said. "Did you ever hear the like? Wants to go to a lawyer to get a passport! An idea!"

"Well, who would I go to, then—an osteaopath?" Morris asked.

"Leon Sammet told me all about it," Abe said. "You go down to a place on Rector Street where you sign an application, and—"

"That's just what I thought," Morris interrupted, "and the least what happens to fellers which signs applications without a lawyer, y'understand, is that six months later a truck-driver arrives one morning and says where should he leave the set of Washington Irving in one hundred and fifty-six volumes or the piano with stool and scarf complete, as the case may be. So I am[Pg 6] going to see Feldman, and if it costs me fifteen or twenty dollars, it's anyhow a satisfaction to know that when you do things with the advice of a smart crooked lawyer, nobody could put nothing over on you outside of your lawyer."

When Morris returned an hour later, however, instead of an appearance of satisfaction, his face bore so melancholy an expression that for a few minutes Abe was afraid to question him.

"Nu!" he said at last. "I suppose you got turned down for being overweight or something?"

"What do you mean—overweight?" Morris demanded. "What do you suppose I am applying for—a twenty-year endowment passport or one of them tontine passports with cash surrender value after three years?"

"Then what is the matter you look so rachmonos?" Abe said.

"How should I look with the kind of partner which I've got it?" Morris asked. "Paris models he must got to got. Domestic designs ain't good enough for him. Such high-grade idees he's got, and I've got to suffer for it yet."

"Well, don't go to Europe. What do I care?" Abe said.

"We must go," Morris replied.

"What do you mean—we?" Abe demanded.

"I mean you and me," Morris said. "Feldman says that just so long as it is one operation he would charge the same for getting one passport as for getting two, excepting the government fee of two dollars. So what do you think—I am[Pg 7] going to pay Henry D. Feldman two hundred dollars for getting me a passport when for two dollars extra I can get one for you also?"

"But who is going to look after the store?" Abe exclaimed.

"Say!" Morris retorted, "you've got relations enough working around here, which every time you've hired a fresh one, you've given me this blood-is-redder-than-water stuff, and now is your chance to prove it. We wouldn't be away longer as six weeks at the outside, so go ahead, Abe. Here is the application for the passport. Sign your name on the dotted line and don't say no more about it."

"Yes, Mawruss," Abe said, three weeks later, as they sat in the restaurant of their Paris hotel, "in a country where the coffee pretty near strangles you, even when it's got cream and sugar in it, y'understand, the cooking has got to be good, because in a two-dollar-a-day American plan hotel the management figures that no matter how rotten the food is, the guests will say, 'Well, anyhow, the coffee was good,' and get by with it that way."

"On the other hand, Abe," Morris suggested, "maybe the French hotel people figure that if they only make the coffee bad enough, the guests would say, 'Well, one good thing, while the food is terrible, it ain't a marker on the coffee.'"

"But the food tastes pretty good to me, Mawruss," Abe said.[Pg 8]

"Wait till you've been here a week, Abe," Morris advised him. "Anything would taste good to you after what you went through on that boat."

"What do you mean—after what I went through?" Abe demanded. "What I went through don't begin to compare with what you went through, which honestly, Mawruss, there was times there on that second day out where you acted so terrible, understand me, that rather as witness such human suffering again, if any one would of really and truly had your interests at heart, they would of give a couple of dollars to a steward that he should throw you overboard and make an end of your misery."

"Is that so!" Morris retorted. "Well, let me tell you something, Abe. If you think I was in a bad way, don't kid yourself, when you lay there in your berth for three days without strength enough to take off even your collar and necktie, y'understand, that the captain said to the first officer ain't it wonderful what an elegant sailor that Mr. Potash is or anything like it, understand me, which on more than one occasion when I seen the way you looked, Abe, I couldn't help thinking of what chances concerns like the Equittable takes when they pass a feller as A number one on his heart and kidneys, and ain't tried him out on so much as a Staten Island ferry-boat to see what kind of a traveler he is."

"Listen, Mawruss," Abe interrupted, "did we come over here paying first-class fares for practically[Pg 9] steerage accommodations to discuss life insurance, or did we come over here to buy model garments and get through with it, because believe me, it is no pleasure for me to stick around a country where you couldn't get no sugar or butter in a hotel, not if you was to show the head waiter a doctor's certificate with a hundred-dollar bill pinned on it. So let us go round to a few of these high-grade dressmakers and see how much we are going to get stuck for, and have it over with."

Accordingly, they paid for the coffee and milk without sugar and the dark sour rolls without butter which nowadays form the usual hotel breakfast in France, and set out for the office of the commission agent whose place of business is the rendezvous for American garment-manufacturers in search of Parisian model gowns. The broad avenues in the vicinity of the hotel seemed unusually crowded even to people as accustomed to the congested traffic of lower Fifth Avenue as Abe and Morris were, but as they proceeded toward the wholesale district of Paris the streets became less and less traveled, until at length they walked along practically deserted thoroughfares.

"And we thought business was rotten in America," Morris said. "Why, there ain't hardly one store open, hardly."

Abe nodded gloomily.

"It looks to me, Mawruss, that if there is any new garments being designed over here," he said, "they would be quiet morning gowns appropriate[Pg 10] for attending something informal like a sale by a receiver in supplementary proceedings, or a more or less elaborate afternoon costume, not too showy, y'understand, but the kind of model that a fashionable Paris dressmaker could wear to a referee in bankruptcy's office so as not to make the attending creditors say she was her own best customer, understand me."

"Well, what could you expect?" Morris said, as they toiled up the stairs to the commission agent's office. "The chances is that up to a couple of months ago, in a Paris dressmaker's shop, a customer arrived only every other week, whereas a nine-inch bomb arrived every twenty minutes, and furthermore, Abe, it was you that suggested this trip, not me, so now that we are over here, we should ought to make the best of it, and if this here commission agent can't show us no new designs, he could, anyhow, show us the sights."

But even this consolation was denied them, for when they reached the commission agent's door it was locked and barred, as were all the other offices on that floor, and bore a placard reading:

FERME

À Cause Du Jour de Fête

"Nu!" Morris said, after he had read and re-read the notice a number of times, "what are we going to do now?"[Pg 11]

"This is the last hair," Abe said, "because you know how it is with these Frenchers, if they close for a death in the family, it is liable to be a matter of weeks already."

"Maybe it says gone to lunch, will be back in half an hour," Morris suggested, hopefully.

"Not a chance," Abe declared. "More likely it means this elegant office with every modern improvement except an elevator, steam heat, and electric light, to be sublet, because it would be just our luck that the commission agent is back in New York right now with a line of brand-new model gowns, asking our bookkeeper will either of the bosses be back soon."

"We wouldn't get back in ten years, I'll tell you that, unless we hustle," Morris declared. He led the way down-stairs to the ground floor, where, after a few minutes, they managed to attract the attention of the concierge, who emerged from her shelter at the foot of the stairs and in rapid French explained to Abe and Morris that all Paris was celebrating with a public holiday the arrival of President Wilson.

"It's a funny thing about the French language," Morris said, as she concluded. "Even if you don't understand what the people mean, you could 'most always tell what they've been eating, which if the French people was limited by law to a ton of garlic a month per person, Abe, this lady would go to jail for the rest of her life."

"Attendez!" said the concierge. "Au dessus il yà un monsieur qui parle anglais."[Pg 12]

She motioned for them to wait and ascended the stairs to the floor above, where they heard her knock on an office door. Evidently the person who opened it was annoyed by the interruption, for his voice—and to Abe and Morris it was a strangely familiar voice—was raised in angry protest.

"Now listen," said the tenant, "I told you before that I've only got this place temporarily, and as long as I am in here I don't want you to do no cleaning nor nothing, because the air is none too good here as it is, and furthermore—"

He proceeded no farther, however, for Abe and Morris had taken the stairs three at a jump and began to wring his hands effusively upon the principle of any port in a storm.

"Well, well, well, if it ain't Leon Sammet!" Abe cried, and his manner was as cordial as though, instead of their nearest competitor, Leon were Potash & Perlmutter's best customer.

"The English language bounces off of that woman like water from a duck's neck," Leon said, "which every five minutes she comes up here and talks to me in French high speed with the throttle wide open like a racing-car already."

"And the exhaust must be something terrible," Abe said.

"I am nearly frozen from opening the windows to let out her conversation," Leon said, "and especially this morning, when I thought I could get a lot of letter-writing done without being interrupted, on account of the holiday."[Pg 13]

"So that's the reason why everything is closed up!" Morris exclaimed.

"But Christmas ain't for pretty near two weeks yet," Abe said.

"What has Christmas got to do with it?" Leon retorted. "To-day is a holiday because President Wilson arrives in Paris."

"And you are working here?" Abe cried.

"Why not?" Leon asked.

"You mean to say that President Wilson is arriving in Paris to-day and you ain't going to see him come in?" Morris exclaimed. "What for an American are you, anyway?"

"Say, for that matter, President Wilson has been arriving in New York hundreds of times in the past four years," Leon said, "and I 'ain't heard that you boys was on the reception committee exactly."

"That's something else again," Abe said. "In New York we've got business enough to do without fooling away our time rubbering at parades, but President Wilson only comes to Paris once in a lifetime."

"And some of the people back home is kicking because he comes to Paris even that often," Leon commented.

"Let 'em kick," Morris declared, "which the way some Americans runs down President Wilson only goes to show that it's an old saying and a true one that there is no profit for a man in his own country, so go ahead and write your letters if you want to, Leon, but Abe and me is going[Pg 14] down-town to the Champs Elizas and give the President a couple of cheers like patriotic American sitsons should ought to do."

"In especially," Abe added, "as it is a legal holiday and we wouldn't look at no model garments to-day."

"After all, Mawruss," Abe Potash said, as he sat with his partner, Morris Perlmutter, in their hotel room on the night after the President's arrival in Paris, "a President is only human, and it seems to me that if they would of given him a chance to go quietly to a hotel and wash up after the trip, y'understand, it would be a whole lot better as meeting him at the railroad depot and starting right in with the speeches."

"What do you mean—give him a chance to wash up?" Morris asked. "Don't you suppose he had a chance to wash up on the train, or do you think him and Mrs. Wilson sat up all night in a day-coach?"

"I don't care if they had a whole section," Abe retorted; "it ain't the easiest thing in the world to step off a train in a stovepipe hat, with a clean shave, after a twenty-hour trip, even if it would of been one of them eighteen-hour limiteds even, and begin right away to get off a lot of schmooes about he don't know how to express the surprise and gratification he feels at such an enthusiastic reception, in especially as he probably lay awake half the night trying to memorize the bigger part[Pg 16] of the speech following the words, 'and now, gentlemen, I wouldn't delay you no longer.' So that's why I say if they would have let him go to his hotel first, y'understand, why, then he—"

"But Mr. and Mrs. Wilson ain't putting up at no hotel. They are staying with a family by the name of Murat," Morris explained.

"Relations to the Wilsons maybe?" Abe inquired.

"Not that I heard tell of," Morris replied.

"Well, whoever they are they've got my sympathy," Abe said; "because once, when the Independent Order Mattai Aaron held its annual Grand Lodge meeting in New York, me and Rosie put up the Grand Master, by the name Louis M. Koppelman, used to was Koppelman & Fine, the Fashion Store, Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and the way that feller turned the house upside down, if he would have stayed another week with us, understand me, I would have hired a first-class A number one criminal lawyer to defend me and wired the relations for instructions as to how to ship the body home."

"I bet yer the Murats feel honored to got Mr. and Mrs. Wilson staying with them," Morris said.

"For the first few days maybe," Abe admitted, "but wait till a couple weeks go by! I give them until January 1, 1919, and after that Mr. and Mrs. Murat would be signaling each other to come up-stairs into the maid's room and be holding a few ain't-them-people-got-no-home conversations. Also, Mawruss, for the rest of their married life,[Pg 17] Mawruss, every time the tropic of who invited them in the first place comes up at meal-times, y'understand, either Mr. or Mrs. Murat is going to get up from the table and lock themselves up in the bedroom for the remainder of the evening. Am I right or wrong?"

"I wouldn't argue with you," Morris said, "because if I would give you the slightest encouragement you are liable to go to work and figure where Mrs. Murat is kicking to Mr. Murat that she couldn't make out with the housekeeping money while the Wilsons is in Paris, on account of having to buy an extra bottle of Grade B milk every day, or something like that, which you talk like Mr. and Mrs. Wilson was in Paris on a couple of weeks' vacation, whereas the President has come here to settle the peace of the world."

"Did I say he didn't?" Abe protested.

"And while you are sitting here talking a lot of nonsense," Morris went on, "big things is happening, which with all the questions he has got to think about, I bet yer the President oser worries his head about a little affair like board and lodging. Also I read in one of them Paris editions of an American paper that there come over to France on the same steamer with him over three hundred experts—college professors and the like—and them fellers is now staying in Paris at various hotels, which, if that don't justify Mr. Wilson in putting up with a private family, y'understand, I don't know what does!"

"I thought at the time I read about them[Pg 18] experts coming over to help the President in the Peace Conference that he was letting himself in for something," Abe observed.

"I bet yer!" Morris said. "And that's where Colonel House was wise when he comes over on a steamer ahead of them, because it is bad enough when you are crossing the ocean in winter-time to be President of the United States and to have to try not to act otherwise, without having three hundred experts dogging your footsteps and thinking up ways to start a conversation and swing it towards the subject they are experts in. Which I bet yer every time the President tried to get a little exercise by walking around the promenade deck after lunch there was an expert on Jugo-Slobs laying for him who was all worked up to tell everything he knew about Jugo-Slobs in a couple of laps, provided the President lasted that long."

"Well, I'll tell you," Abe said, "a man which employs experts to ask advice from deserves all he gets, Mawruss, because you know how it is when you ask an advice from somebody which don't know a thing in the world about what he is advising you. He'll talk you deaf, dumb, and blind, anyhow. So you can imagine what it must be like when you are getting advice from an expert!"

"It seems to me that before the President gets through he will be looking around for an expert which is expert in choking off advice from experts, otherwise the first time the President consults[Pg 19] one of them experts, if he's going to wait for the expert to get through, he will have to be elected to a third term and then maybe hold over, at that," Morris commented.

"I should think the President would be glad when this Peace Conference is over," Abe said.

"Say! For that matter he'll be glad when it's started," Morris said. "Which the way it looks now, Abe, the preliminaries of a peace conference is harder on a President in the way of speeches and parades than two Liberty Loan campaigns and an inauguration. Take, for instance, the matter of dinners, and I bet yer before he even goes to London next week he would have six meals with the President of France alone—I can't remember his name."

"Call him Lefkowitz," Abe said, "I'll know who you mean."

"Well, whatever it is, he looks like a hearty eater, Abe," Morris remarked.

"In fact, Mawruss, from what I seen of them French politicians in the parade this morning," Abe observed, "none of them looked like they went slow on starchy foods and red meats, whereas take the American Peace Commissioners, from the President down, and while they don't all of them give you the impression that they eat breakfast food for dinner exactly, still at the same time if these here peace preliminaries is going to include more dinners than parades, the French Commissioners has got them under a big handicap."

"Maybe you're right," Morris agreed. "But[Pg 20] my idee is that with these here preliminary peace dinners it ain't such a bad thing for us if our Peace Commissioners wouldn't be such hearty eaters, y'understand, because you know how it is when we've got a hard-boiled egg come into the place to look over our line, it's a whole lot better to get an idee of about how much he expects to buy after lunch than before, in especially if we pay for the lunch. So if this here President Lefkowitz, or whatever the feller's name is, expects to fill up the President with a big meal of them French à la dishes until Mr. Wilson gets so good-natured that he is willing to tell not only his life history, but also just exactly what he means by a League of Nations, y'understand, the dinner might just as well start and end with two poached eggs on toast, for all the good it will do."

"Still, it ain't a bad idee to have all these dinners over and done with before the business of the Peace Conference begins, Mawruss," Abe remarked, "because hafterwards, when Mr. Wilson's attitude on some of them fourteen propositions for peace becomes known, y'understand, it ain't going to be too pleasant for Mrs. Wilson to be sitting by the side of her husband and watch the looks of some of the guests sitting opposite during the fish course, for instance, not wishing him no harm, but waiting for a good-sized bone to lodge sideways in his throat, or something."

"She is used to that from home already, whenever she has a few Republican Senators to dinner[Pg 21] at the White House," Morris said. "But that ain't here nor there, anyhow, because after the Peace Conference begins the President will be so busy, y'understand, that sending out one of the Assistant Secretaries of State to a Busy Bee lunch-room to bring him a couple of sandwiches and some coffee will be the nearest to a formal dinner that the President will come to for many a day. Take, for instance, the proposition of the Freedom of the Seas, and there's a whole lot to be said on both sides by people like yourself which don't know one side from the other."

"And I don't want to know, neither," Abe said, "because it wouldn't make no difference to me how free the seas was made, once I get back on terra cotta, Mawruss; they could not only make the seas free, y'understand, but they could also offer big bonuses in addition, and I wouldn't leave America again not if they was to give me a life pass good on the Olympic or Aquitania with meals included."

"So your idea is that the freedom of the seas means traveling for nothing on ocean steamers?" Morris commented.

"Say!" Abe retorted, "why should I bother my head what such things mean when I got for a partner a feller which really by rights belongs down at the Peace headquarters, along with them other big experts?"

"I never claimed to be an expert, but at the same time, I ain't an ignerammus, neither, which even before I left New York, I knew all about[Pg 22] this here Freedom of the Seas," Morris said, "which the day before we sailed I was talking to Henry Binder, of Binder & Baum, and he says to me—"

"Excuse me, but what does Binder & Baum know about the Freedom of the Seas?" Abe demanded. "They are in the wholesale pants business, ain't it?"

"Sure, I know," Morris continued, "and Paderewski is a piano-player, and at the same time he went over to Poland to organize the new Polish Republic."

"And the result will be that when the new Polish Republic gets started under the direction of this here piano-player," Abe said, "and they get a new Polish National Anthem, it will be an expert piano-player's idea of something which is easy to play, and the consequence is that until the next Polish revolution, every time a band plays the Polish National Anthem, them poor Polacks would got to stand up for from forty-five minutes to an hour while the band struggles to get through with what it would have taken Paderewski three minutes at the outside."

"Henry Binder is a college graduate even if he would be in the pants business," Morris said, "and he said to me: 'Perlmutter,' he said, 'the Freedom of the Seas is like this,' he says. 'You take a country like Norway and it stands in the same relation to the big naval powers like we would to the other big manufacturers. Now, for instance,' he says, 'last year we did a business of over two million dollars, and—'"[Pg 23]

Abe raised his right hand like a traffic policeman.

"Stop right there, Mawruss," he said, "because if the Freedom of the Seas is anything like Binder & Baum doing a business of two million dollars last year, I don't believe a word of it, which it wouldn't make no difference if Henry Binder was talking about the Freedom of the Seas or astronomy, sooner or later he is bound to ring in the large amount of goods he is selling, and, anyway, no matter what Henry Binder tells you, you must got to reckon ninety-eight per cent. discount before you could believe a word he says."

"And do you suppose for one moment that the members of the Peace Conference is going to act any different from Henry Binder in that respect?" Morris asked. "Every one of the representatives of the countries engaged in this here Peace Conference is coming to France with a statement of the very least they would accept, and it is pretty generally understood that all such statements are subject to a very stiff discount, which that is what these here preliminaries is for, Abe—to get a line on the discounts before the Peace Conference discusses the claims themselves."

"Well, when it comes to the Allies scrapping between themselves about League of Nations and Freedoms of Seas, I am content that they should be allowed a liberal discount on what they say for what they mean, Mawruss, but when it comes to Germany," he concluded, "she's got to pay, and pay in full, net cash, and then some."

"The alphabet ain't what it used to be before the war, Mawruss," Abe said, as he read the paper at breakfast in his Paris hotel shortly after President Wilson's visit to England. "Former times if a feller understood C. O. D. and N. G., y'understand, he could read the papers and get sense out of it the same like he would be a college gradgwate, already; but nowadays when you pick up a morning paper and read that Colonel Harris Lefkowitz, we would say, for example, A. D. C. to the C. O. at G. H. Q. of the A. E. F., has been decorated with the D. S. O., you feel that the only way to get a line on what is going on in the world is to get posted on this—now—algebry which ambitious young shipping-clerks gets fired for studying during office hours."

"Well, if you get mixed up by these here letters, think what it must be like for President Wilson to suddenly get one of them English statesmen sprung on him by—we would say—the King—where the King says: 'Mr. President, shake hands with the Rutt Hon. Duke of Cholomondley, K.C.M.G., R.V.O., K.C.B., F.P.A., G.S.I., and sometimes W. and Y.'" Morris said, "in especially[Pg 25] as I understand Cholomondley is pronounced as if written Rabinowitz."

"It would anyhow give the President a tropic for conversation such as ain't it the limit what you got to pay to get visiting-cards engraved nowadays, which it really and truly must cost the English aristocracy a fortune for such things," Abe said, "in particularly if the daughter of such a feller gets married with engraved invitations, Mawruss, after he had paid the stationery bill, y'understand, he wouldn't got nothing left for her dowry."

"Well, I guess the President wasn't in no danger of running out of tropics of conversation while he was in England, Abe," Morris said, "which during all the spare time Mr. Wilson had on his trip he did nothing but hold conversations with Mr. Balfour, and this here Lord George, and you could take it from me, Abe, there wasn't many pauses to be filled up by Mr. Wilson saying ain't it a funny weather we are having nowadays, or something like that."

"How do you know?" Abe asked. "Was you there?"

"I wasn't there," Morris said, "but last night I was speaking in the lobby of the hotel to one of them newspaper reporters which made the trip with the President, and after I had given the young feller one of the cigars we brought with us from New York he got quite friendly and told me all about it. It seems, Abe, that the visit was a wonderful success, in particular the first[Pg 26] day Mr. Wilson was in England. The weather was one of the finest days they had in winter over in England for years already. Only six inches of rain, and the passage across the English Channel was so smooth for this time of the year that less than eighty per cent. of the passengers was ill as against the normal percentage of 99.31416. As Mr. Wilson had requested that no fuss should be made over his visit, things was kept down as much as possible, so that, on leaving Calais, the President's boat was escorted by only ten torpedo-boat destroyers, a couple battle-ships, three cruisers, and eight-twelfths of a dozen assorted submarines. There was also a simple and informal escort of about fifty airy-oplanes, the six dirigible balloons having been cut out of the program in accordance from the President's wishes. However, Abe, all this simplicity was nothing compared to the way they acted when the President arrived at Dover. There the arrangements was what you might expect when the President of a plain, democratic people visits the country of another plain, democratic people, Abe. The only people there to meet them was about twenty or thirty dukes, a few field-marshals, three regiments of soldiers, including the bands, and somebody which the newspaper reporter says he at first took for Caruso in the second act of 'Aïda' and afterwards proved to be the mayor of Dover in his official costume.

"The ceremony of welcoming Mr. and Mrs. Wilson to the shores of England was very short,[Pg 27] the whole thing being practically over in two hours and thirty minutes," Morris continued. "It consisted of either the firing of a Presidential salute of twenty-one guns or the playing of the American National Anthem by the massed bands of three regiments, the reporter says he couldn't tell which, on account he stood behind one of the drums. Later the President made a short speech, in which he said: 'May I not say how glad I am to land in Dover,' or something to that effect."

"And after that boat-ride from France he would have said so if it had been Barren Island, or any other place-just so long as it was free from earthquakes and didn't roll none," Abe agreed. "Also, Mawruss," he continued, "some day the President is going to begin a speech with, 'May I not,' and the chairman of the meeting will take him at his word and put it to a standing vote, and it is going to surprise the President how few people is going to remain seated on the proposition of whether or not he shall continue to begin letters and speeches with, 'May I not.'"

"Say!" Morris exclaimed. "When we get by mail a cancelation and answer it, 'Dear Gents, Your favor received,' does that mean we think the customer is doing us a favor by canceling an order on us? Oser a Stuck. And in the same way, when Mr. Wilson says, 'May I not?' nobody fools themselves for a minute that the President is asking permission. That's just a habit us and him got into, Abe, and in fact, Abe, Mr. Wilson's[Pg 28] 'May-I-nots' have always meant that not only was he going to say what he intended to say, but that he was also going to do it, too. So, therefore, you take the speech he made at the Gelthall in London, and—"

"But as I understand your story, Mawruss, he only just arrived in Dover," Abe said, "so go ahead with your lies, and tell me what happened next."

"Well," Morris went on to say, "after the mayor of Dover had presented Mr. Wilson with the Freedom of the City in a gold casket—"

"Excuse me, Mawruss," Abe interrupted, "but what is this here Freedom of the City that mayors is all the time presenting to Mr. Wilson?"

"I don't know," Morris replied, "except that seemingly a Freedom of the City always comes in a gold casket."

"Sure, I know," Abe said, "but what does Mr. Wilson gain by all these here Freedoms of Cities?"

"Gold caskets," Morris replied, "although I think myself that some of these mayors ain't above getting by with a gold-plated silver casket, or even a rolled-gold casket, relying on the fact that Mr. Wilson is too much of a gentleman to get an appraisal, anyhow till he returns to America."

"Well, if I would be Mr. Wilson, I wouldn't take it so particular to act too gentlemanly to them mayors," Abe commented, "because I see in the papers that when the mayor of London presented him with the Freedom of the City,[Pg 29] Mr. Wilson got the Freedom part, but he was told that the gold casket was in preparation, which I admit that I don't know nothing about this here mayor of London, but you know how it is when a customer gets married, Mawruss, and we put off sending him a wedding present till we could get round to it, y'understand, which we are all human, Mawruss, and it wouldn't surprise me in the least if six months from now the mayor of London would be going round saying, 'Why should we give that feller a gold casket—am I right or wrong?'—and let the whole gold-casket thing die a natural death."

"They'll probably come across with it after a few how-about-casket cables, and, anyhow, if they didn't, Abe, the English people certainly done enough for Mr. Wilson," Morris continued, "because that newspaper reporter told me that the reception which Mr. Wilson got in London was something enormous, y'understand. The King and Queen was waiting to meet him and the station platform was covered with a red-velvet pile carpet which was so thick, understand me, that they 'ain't been able as yet to locate a couple of suit-cases which was carelessly put down by the Rutt Hon. the Duke of Warrington, K.G.Y., Y.M.H.A., First Lord Red Cap in Waiting, and sunk completely out of sight while he helped a couple of Assistant Red Caps in Waiting, also dukes, load the Presidential wardrobe trunks on the Royal Baggage Transfer truck."

"What do you mean—also dukes?" Abe demanded.[Pg 30] "Do you mean to say that the Red Caps which hustles the King's baggage is dukes?"

"At the very least," Morris declared, "because the Master of the Royal Fox-hounds is an earl, Abe, and I leave it to you, Abe, if handling baggage ain't a better job than feeding dogs. Also, Abe, there is Lords in Waiting and Ladies in Waiting, and it wouldn't surprise me in the slightest if during their stay in Buckingham Palace some of the members of Mr. Wilson's party which ain't been tipped off have telephoned down to the office for towels and kept the Marquis of Hendersonville, Lanes County, England, Knight Commander of the Bath, waiting at the bedroom door ten minutes, while they went through all their clothes trying to find something smaller than a quarter to slip him."

"And do you believe for one moment, Mawruss—if there was a Marquis of Hendersonville, which I never heard of such a person, Mawruss—and he did happen to be Knight Commander of the Bath, y'understand, that he is actually handing out soap and towels in the King of England's palace?" Abe inquired.

"Certainly I don't believe it," Morris replied, "and I also don't believe that calling anybody Right Honorable is going to make him any more right than he is honorable, unless, of course, he is honorable to start with and really and truly wants to be right, y'understand. And that is what Mr. Wilson went to England to find out, Abe, because it ain't going to affect the Peace[Pg 31] Conference one way or the other if the Master of the Royal Fox-hounds don't know a dawg-biscuit from a gingersnap, y'understand, whereas if this here war is going to be settled once and for all, Abe, it's quite important that the Right Honorable English statesmen should have right and honorable intentions."

"And did Mr. Wilson find out?" Abe asked.

"Sure he did," Morris said, "although from what this here newspaper reporter tells me, Abe, there was a whole lot of lost motion about the investigation. Take, for instance, the attitude of Mr. Lord George on the Freedom of the Seas, for instance, and you would think that in the case of a busy man like Mr. Wilson, y'understand, he would of rung him up on the telephone, made an appointment for luncheon the next morning, and by half past one at the outside they would have got the matter in such shape that the only point not settled between 'em would be a friendly quarrel as to see who should pay for the eats, y'understand. Actually, however, the arrangements for having Mr. Wilson get into touch with Lord George was conducted by the Comptroller of the Royal Household, and the line of march was down Piccadilly as far as Forty-second Street, over to Hyde Park, and by way of Hyde Park west to Eighth Avenue to Mr. Lord George's office in the London & Liverpool Title Guarantee and Trust Company Building. The order of procession was as follows:

"Twelve mounted policemen.[Pg 32]

"The band of the King's Own Sixty-ninth Regiment.

"Typographical Union No. 6, Allied Printing Trades Council of Great Britain and Ireland.

"William J. Mustard Association, Drum and Fife Corps.

"Household Guards.

"First carriage—Mr. Wilson and the King.

"Second carriage—Mrs. Wilson and the Queen.

"Third carriage—Mr. George Creel.

"Fourth carriage—Master of the Royal Fox-hounds, Master of the Royal Buck-hounds, Master of the Royal Stag-hounds, two Masters of Assorted hounds.

"Six Motor-cycle Policemen.

"The Stock Exchange closed, and promissory notes falling due on that date became automatically payable on the following day. Admission to the reviewing-stand was by card, some of which found their way into the hands of the speculators, and will shortly be the subject of a John Doe investigation by the district attorney of Middlesex County, so the newspaper feller told me."

"But what is this here Lord George's attitude towards the Freedom of the Seas, Mawruss?" Abe asked.

"That the newspaper feller didn't know," Morris said.

"Well, who does know?" Abe insisted.

"Lord George," Morris replied.

"Yes, Abe," Morris Perlmutter said to his partner, Abe Potash, a few days after Mr. Wilson's return from his visit to Italy, "up to a short time ago hardly anybody in America had ever even heard about Italy's claims to the Dalmatian territory."

"Naturally!" Abe replied; "because if there is six people in the whole United States which is engaged in the business of selling spotted dogs to fire-engine houses, Mawruss, that would be big already."

Morris threw up both hands in a gesture of despair. "What is the use talking foreign politics to a feller which thinks that Italy's claims to the Dalmatian territory means she wants the exclusive right to make New York, Cleveland, Chicago, and St. Louis with a line of spotted dogs for fire-engine companies!" he exclaimed.

"And I wouldn't even have known that it meant that much," Abe retorted, entirely unabashed, "excepting that six months ago my wife's sister's cousin wanted me I should advance her a hundred dollars to pay a lawyer he should[Pg 34] bring suit against the city for her on account she got bitten by one of them fire-house Dalmatians, Mawruss, which up to that time I always had an idea they was splashed-up white dogs. So go ahead, Mawruss, I'll be the goat. What is Italy's claims to the Dalmatian territory?"

"Well, in the first place, Italy thinks she should be awarded all them towns where a majority of the people which lives in them speaks Italian," Morris said; "like Fiume, Spalato, Ragusa—"

"Also New Rochelle, Mount Vernon, and The Bronx," Abe added; "and if she wants to get nasty, Mawruss, she could claim all the territory east of Third Avenue, from Ninetieth Street up to the Harlem River, too. Furthermore, Mawruss, there is neighborhoods south of Washington Square where not only the majority of the people speaks Italian, but the minority speaks it also. So you see how complicated things becomes when a new beginner like me starts in to talk foreign politics."

"For that matter, all us Americans is new beginners on foreign politics, from Mr. Wilson down, Abe," Morris said. "And that is why Mr. Wilson done a wise thing when he visited Italy the other day, and took a lot of American newspaper fellers with him, because, between you and me, Abe, it wouldn't surprise me in the least if some of them reporters went down there under the impression that the only thing which distinguished Ragusa from Ravioli or Spalato from[Pg 35] Spaghetti was the difference in the shape of the noodles, but that otherwise they was cooked the same, with chicken livers and tomato sauce, which you know how it is in America: ninety per cent. of the people gets their education from reading in newspapers, and the consequence is that if the American newspaper reporters has a sort of hazy idea that Sonnino is either an item on the bill of fare, to be passed up on account of having garlic in it, or else a tenor which the Metropolitan Opera House ain't given a contract to as yet, y'understand, then the American public has got the same sort of hazy idea. So Mr. Wilson done the right thing traveling to Italy, even if he did have an uncomfortable journey."

"What do you mean—an uncomfortable journey?" Abe demanded. "Why, I understand he traveled on the King of Italy's royal train!"

"Sure, I know," Morris agreed; "but when a king is sleeping on a royal train in Europe, Abe, he can be pretty near as comfortable as a traveling-salesman sitting up all night on a day-coach in America, and if he spends two nights on such a royal train, the way President Wilson did in going from Paris to Rome, which is about as far as from New York to Chicago, y'understand, it wouldn't make no difference how many people is waiting at the station to holler 'Long live the King!' understand me, he is going to feel half dead, anyway."

"And yet there is people which claims that Mr. Wilson don't give a whoop whether he makes himself popular or not," Abe commented, "which[Pg 36] before I could lay awake two nights on a train, I wouldn't care if every newspaper reporter in the United States never got no nearer to Italy than a fifty-cent table d'hôte, including wine."

"Maybe you would care if you was going to Italy to make speeches the way Mr. Wilson did," Morris said. "Which if the King of Italy was to go to America and make speeches in Italian at the Capitol in Washington, it would be just as well if he would bring along an audience of a few dozen Italians with him, and not depend on enough barbers, shoe-blacks, and vegetable-stand keepers horning in on the proceedings to give the Congressmen and Senators a hint as to where the applause should come in. In fact, I was speaking to one of them newspaper fellers which went to Italy, Abe, and he says that he listened carefully to all the speeches which was made in Italian, Mawruss, and that once he thought he heard the word Chianti mentioned, but he couldn't say for certain. He told me, however, that the correspondent of The New York Evening Post also claims that he heard Orlando, the Prime Minister, in a speech delivered in Rome, use the words Il Trovatore, but that otherwise the whole thing was like having the misfortune to see somebody give an imitation of Eddie Foy when you've escaped seeing Eddie Foy in the first place, so you can imagine what chance Mr. Wilson would have stood with them Italians if the American correspondents hadn't been along to start the cries of 'Bravo!' in the right spot.[Pg 37]

"So you see, Abe, it's a good thing for them newspaper men to see what kind of people the Italians is in their own country," Morris continued, "because if this here League of Nations idea is going to be put over by Mr. Wilson, Americans should ought to know from the start that Italy is a Big League nation and its batting average in this war is just as good as the other Big League nations."

"Did any one say it wasn't?" Abe demanded.

"I know they didn't," Morris said. "But just the same, Abe, there's a whole lot of people in America which judges the Italians by the way they behave in the ice business and 'Cavalleria Rusticana,' and also a feller can get a very unfavorable opinion of Italians by being shaved in one of them ten-cent palace barber shops, understand me, so even if them newspaper men couldn't appreciate the performance without a libretto, y'understand, they could anyhow see for themselves that the Italians in Italy is doctors and lawyers, clothing-dealers and bankers, just the same like the Americans are in America, and if they can pass the word back home, with a few details of how it feels to be a foreigner in a foreign country, that wouldn't do no harm, neither."

"That is something which an American newspaper correspondent wouldn't touch on at all," Abe said, "because I bet that every last one of them has already sent back to America an article about this trip to Italy, which, when the readers of his newspaper looks at it, Mawruss, not only[Pg 38] would they think that he understood Sonnino's speech from start to finish, y'understand, but also that every time the newspaper feller is in Rome, which the article would lead one to believe has been on an average of once a week for the past ten years, Mawruss, him and Sonnino drink coffee together."

"Ain't he taking a big chance when he writes a thing like that?" Morris commented.

"Yow! A chance!" Abe exclaimed. "Why, to read the things that a few of these here Washington correspondents used to write when they was in America yet, you would think every one of them was pestered to death with telephone messages from the White House where Mr. Tumulty says if the newspaper feller has got a little spare time that evening the President would consider it a big favor if he would step around to the White House, as Mr. Wilson would like to ask him an advice about a diplomatic note which has just been received from Lord George in regards to the Freedom of the Seas or something."

"But don't you suppose the newspaper which a nervy individual like that is working for would fire him on the spot?" Morris observed.

"Not at all," Abe said, "because the newspaper-owner likes people to get the idea that the newspaper has got such an important feller for a Washington correspondent, just as much as the correspondent does himself, Mawruss, so you can imagine the bluff some of them fellers is going to throw now that they really got something interesting[Pg 39] to write about like this here Peace Conference. If Mr. Wilson gains all his fourteen points, y'understand, the special Paris correspondent of the Bridgetown, Pa., Daily Register is going to write home, 'And he could have gained fifteen if he would only have listened to me.' Also, Mawruss, during the next three months, if the Peace Conference lasts that long, the readers of the Cyprus, N. J., Evening Chronicle is going to get the idea that President Wilson, Clemenceau, Lord George, and a feller by the name of Delos M. Jones, who is writing Peace Conference articles for the Cyprus, N. J., Evening Chronicle, are in secret conference together every day, including Sundays, from 10 a.m. to midnight, fixing up the boundaries between Rumania and Servia."

"Well, them boys has got to produce something to make their bosses back in America continue paying salary and traveling expenses," Morris said, "because from what this here newspaper correspondent tells me, if he didn't get his imagination working, all he could write for his paper would be descriptions of Paris scenery, including the outside of the buildings where on the insides, with the doors locked and the curtains pulled, Mr. Wilson and the American Peace Commissioners is openly and notoriously carrying on open and notorious peace conversations with the other allied Peace Commissioners, and for all the newspaper correspondents know to the contrary, Abe, the only point on which them Peace Commission[Pg 40] fellers ain't breaking up the furniture over is that when they come out, y'understand, it is agreed that the newspaper correspondents will be told that everything is proceeding satisfactorily."

"But I thought Mr. Wilson promised before he left America that the old secret diplomacy would be a thing of the past," Abe said.

"So he did," Morris agreed, "and by what I gather from this here newspaper man he kept his promise, too, and we now have got a new diplomacy, compared to which the fellers who were working under the rules of the old secret diplomacy bladded everything they knew."

"But I distinctly read it in the papers the other day that every morning at half past ten, Mawruss, Mr. Lansing meets the newspaper correspondents and lets them know what's been going on," Abe said.

"He meets them," Morris replied, "but so far as letting them know what has been going on is concerned, all he says that everything is proceeding satisfactorily and is there any gentleman there which would like to ask him any questions, which naturally any newspaper correspondent who could ask Mr. Lansing such questions as would make Mr. Lansing give out any information he didn't want to give out, wouldn't be wasting his time working as a newspaper correspondent, Abe, but would be considering offers from the law firm of Hughes, Brandeis, Stanchfield, Hughes & Stanchfield to come in as a full partner and take exclusive charge of the cross-examination of busted railroad presidents."[Pg 41]

"Maybe the reason why Mr. Lansing don't tell them newspaper correspondents nothing is that he ain't got nothing to tell them," Abe suggested.

"Well, then, if I would be him, Abe, I would make up something," Morris said, "because if he don't they will, or anyhow some of them will, and there is going to be a lot of stuff printed in American papers where the correspondent says he learns from high authority that things ain't going so good in the Peace Conference as Mr. Wilson would like, because Mr. Wilson is the doctor in the case, and you know how it is when somebody is too sick to be seen and the doctor is worried, Abe, he sends down word by the nurse that everything is proceeding satisfactorily, and the visitor goes away trying to remember did he or did he not throw away that fifty-cent black four-in-hand tie he wore to the last funeral he went to."

"I got a whole lot of confidence in Mr. Wilson as the doctor for this here war-sickness which Europe is suffering from, Mawruss," Abe said.

"So have I," Morris said: "but you've got to remember that there's a whole lot of those doctors on the case, Abe—some of them quack doctors, too, and, when the doctors disagree, who is to decide?"

"I don't know," Abe said; "but I think I know who would like to."

"Who?" Morris asked.

"Some of these here Washington newspaper correspondents you was talking about," Abe concluded.

"Well, Mawruss," Abe Potash said, as he and his partner, Morris Perlmutter, sat at breakfast in their Paris hotel one Sunday morning, "I see that the Peace Conference had a meeting the other day where it was regularly moved and seconded that there should be a League of Nations, and, in spite of what them Republican Senators back home predicted, Mawruss, when Chairman Clemenceau said, 'Contrary minded,' you could of heard a pin drop."

"Sure you could," Morris Perlmutter agreed, "because the way this here Peace Conference is being run, Abe, when Mr. Clemenceau says: 'All those in favor would please say Aye,' he ain't asking them, he's telling them, which I was speaking to the newspaper feller last night, Abe, and he says that, compared to the delegates at this here Peace Convention, y'understand, the delegates of a New York County Democratic Convention are free to act as they please. In fact, Abe, as I understand it, at the sewed-up political conventions which they hold it in America, the bosses do occasionally let a delegate get up[Pg 43] and say a few words which ain't on the program exactly, but at this here Peace Convention a delegate who tries to get off a speech which 'ain't first been submitted in writing ten days in advance should ought to go into training for it by picking quarrels with waiters in all-night restaurants.

"Take this here meeting which they held it on Saturday, Abe," Morris continued, "and it was terrible the way Chairman Clemenceau jumps, for instance, on a feller from Belgium by the name M. Hyman."

"That ain't the same M. Hyman which used to was M. Hyman & Co. in the coat-pad business?" Abe inquired.

"This here M. Hyman used to was a Belgium minister in London," Morris went on, "which he got up and objected to the way the five big nations—America, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan—was, so to speak, hogging the convention."

"Well, I think the Reverend Hyman was right, at that," Abe said, "which I just finished reading Mr. Wilson's speech at that meeting, Mawruss, in which he said that no longer should the select classes govern the rest of mankind, y'understand, and after the American, French, British, Italian, and Japanese delegates gets through applauding what Mr. Wilson says, they select themselves to run the rest of the nations in the League of Nations. Naturally an ex-minister like the Reverend Hyman is going to say, 'Why don't you practise what you preach?'"[Pg 44]

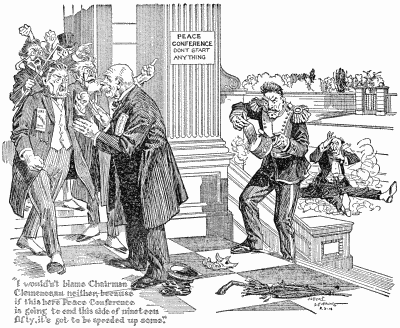

"And if he wouldn't of been an ex-minister, Abe," Morris said, "the chances is that Chairman Clemenceau would of whispered a few words into the cauliflower ear of one of the sergeants-at-arms, and when the session closed, y'understand, the hat-check boy would have had one hat left over with the initials M. H. in it which Mr. Hyman didn't have time to claim before he hit the car tracks, y'understand, and I wouldn't blame Chairman Clemenceau, neither, because, if this here Peace Conference is going to end this side of nineteen-fifty, it's got to be speeded up some."

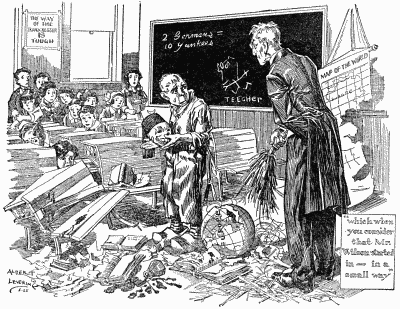

"I wouldn't blame Chairman

Clemenceau neither, because

if this here Peace Conference

is going to end this side of nineteen

fifty, it's got to be speeded up some."

"Nobody says it 'ain't," Abe agreed, "but this here M. Hyman is a Belgium and he's got a right to be heard."

"He would have if everybody didn't admit that Belgium shall be protected in every which way, Abe," Morris agreed, "but there is also a lot of small nations which has got delegates at the Peace Convention, like Cuba, y'understand, and some of them South American republics, and, once you begin with them fellers, where are you going to leave off? Take, for instance, the Committee on Reparation, which has got charge of deciding how much money Germany ought to pay for losses suffered by the countries which made war on her, y'understand, and there wasn't one of them Spanish-American republics which didn't want to get appointed on that committee, because, when the Reparation Committee gets to work, practically all of them republics is going[Pg 45] to come along with claims for smoke damages, bills for labor in connection with ripping out the fixtures of confiscated German steamers, loss of services of the Presidents of such republics by reason of tonsillitis from talking about how bravely they would have fought if they had raised an army and navy which they didn't, y'understand, and any other claims against Germany which they think they might have had a chance to get by with."

"Well, of course there is bound to be a lot of them small republics which is going to make a play for a little easy money, Mawruss," Abe said, "but the indications is that when the proofs of claims is filed by the alleged creditors, y'understand, there would be a couple of them comma hounds on the Reparation Committee which would reject such claims on the grounds of misplaced semicolons alone. Then six months hafterwards, when the representative of one of them republics goes over to what used to was the office of the Peace Conference with a revised proof of claim, which he has just received by return mail, understand me, he would find the premises temporarily occupied by one of them crooked special-sale trunk concerns, and that's all there would be to it."

"Then you think that this here Peace Conference would only last six months, Abe?" Morris asked.

"Sure I do," Abe replied, "and less, even, because right now already the interest is beginning[Pg 46] to die out, which it wouldn't surprise me in the slightest, Mawruss, if in three weeks or so, when Mr. Wilson is temporarily out of the cast on account of going home to America to sign the new tax bill, y'understand, the attendance of the delegates would begin to fall off so bad, understand me, that the Peace Conference managers would got to spend a lot of money for putting in advertisements that George Clemenceau presents:

|

"'The International Peace Conference

Quai d'Orsay |

"And even then they wouldn't get an audience, Abe," Morris said, "because those kind of advertisements don't fool nobody but the suckers which pays for them, Abe."

"Maybe not," Abe agreed, "but if the delegates stays away, Mawruss, the Peace Conference could always get an audience by letting in the newspaper correspondents, which I don't care if[Pg 47] in addition to Mr. Lord George and Colonel House they would got performing at this here Peace Conference Douglas Fairbanks and Caruso, it wouldn't be a success as a show, anyhow, because no theayter could get any audiences if they would make it a policy to bar out the newspaper crickets."

"Well, I'll tell you," Morris began. "Nobody likes to read in newspapers more than I do, Abe. They help to pass away many unpleasant minutes in the Subway when a feller would otherwise be figuring on if God forbid the brakes shouldn't hold what is going to become of his wife and children, y'understand; but, at the same time, from the way this here newspaper feller which hogs our cigars is talking, Abe, I gather that the big majority of newspaper reporters now in Paris has got the idea that this here Peace Conference is being held mainly to give newspaper reporters a chance to write home a lot of snappy articles about peace conferences, past and present. Although, of course, there is certain more or less liberal-minded newspaper men which think that if, incidentally, Mr. Wilson puts over the League of Nations and the Freedom of the Seas, why, they 'ain't got no serious objections, just so long as it don't involve talking the matter over privately without a couple of hundred newspaper reporters present."

"Sure, I know," Abe said; "but if them newspaper fellers has got such an idee, Mawruss, it is Mr. Wilson's own fault, because ever since we[Pg 48] got into the war, y'understand, Mr. Wilson has been talking about open covenants of peace openly arrived at, and even before we went into the war he got off the words 'pitiful publicity,' and also it was him and not the newspaper men which first give the readers of newspapers to understand that the old secret diplomacy was a thing of the past, Mawruss, so the consequences was that, when Mr. Wilson come over here, the owners of newspapers sent to Paris everybody that was working for them—from dramatic crickets to baseball experts—just so long as they could write the English language, y'understand, because them newspaper-owners figured that, according to Mr. Wilson's own suggestions, this here Peace Conference was not only going to be a wide-open affair, openly arrived at, y'understand, but also pitifully public, whereas not only it ain't wide open, Mawruss, but it is about as pitifully public as a conference between the members of the financial committee of Tammany Hall on the day before Election. Also, Mawruss, a newspaper reporter could arrive at that Peace Conference openly or he could arrive at it disguised with false whiskers till his own wife wouldn't know him from a Jugo-Slob delegate, y'understand, and he couldn't get past the elevator-starter even."

"That was when the conference opened," Morris said; "but I understand they are now letting them into the next room and giving them once in a while a look through the door during the supper[Pg 49] turns when the Polack and Servian delegates is performing."

"And that ain't going to do them a whole lot of good, neither," Abe declared, "because this here newspaper feller told me last night, when he was smoking my last cigar, that he has been mailing back an article a day to America ever since the President arrived here and there ain't not one of them which has got there yet."

"And I was reading in the America edition of the Paris edition of the London edition of the Manchester, England, Daily News that the newspaper correspondents couldn't only send back a couple of hundred words or so by telegraph, Abe," Morris said, "which the way it looks to me, Abe, if some news don't find its way back to America pretty quick about this here Peace Conference and Mr. Wilson, y'understand, people back home in Washington is going to say to each other, 'I wonder whatever become of this here—now—Wilson?' and the friend is going to say, 'What Wilson?' And the other feller would then say, 'Why, this here Woodruff Wilson.' And then the friend would say, 'Oh, him! Didn't he move away to Paris or something?' And the other feller would then say, 'I see where Benny Leonard put up a wonderful fight in Madison Square Garden yesterday,' and that's all there would be to that conversation."

"Maybe it is because of this, and not because of signing the new tax bill, that the President is[Pg 50] going home in a few days for a short stay in America," Abe suggested.

"Sure, I know," Morris agreed; "but what good is them short visits going to do him, because I ain't such an optician like you are, Abe. I believe that this here Peace Conference is going to last a whole lot longer than six months, Abe, and, if Mr. Wilson keeps on going home and coming back, maybe the first time he goes back he would get some little newspaper publicity out of it, and the second time also, perhaps, but on the third when he returns from France only the Democratic newspapers would give him more as half a column about it, and later on, when he lands from his third to tenth trips, inclusive, all the notice the papers would take from it would be that in the ship's news on the ninth page there would be a few lines saying that among those returning on the S.S. George Washington was J. L. Abrahams, and so on through the B's, C's, and D's right straight down to the W's, which you would got to read over several times before you would discover the President tucked away as W. Wilson between two fellers named Max Wangenheim and Abraham Welinsky."

"There is something in what you say, Mawruss," Abe admitted; "but, at the same time, a big man like Mr. Wilson ain't looking to get no newspaper notoriety. He is working to become famous."

"Sure, I know," Morris said; "but the only difference between notoriety and fame is that with[Pg 51] notoriety you get the publicity now, whereas with fame you get the publicity fifty years from now, and the publicity which Mr. Wilson is going to get fifty years from now ain't going to help him a whole lot in the next presidential campaign."

"Mr. Wilson ain't worrying about the next presidential campaign, Mawruss," Abe declared. "What he is trying to do is to make a success of this here Peace Conference."

"Then he would better get a press agent for it," Morris observed, "because, if they don't get some more publicity, it will die on its feet."

"I see where several Americans took advantage to join the Legion of Honor while they was over here," Morris Perlmutter remarked, as he sat at luncheon with his partner, Abe Potash, in the restaurant of their Paris hotel.

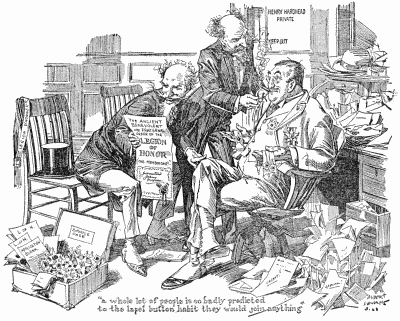

"Some people is crazy for life insurance," Abe Potash commented, "in especially if they could combine it with the privilege to make speeches at lodge-meetings. Also, Mawruss, a whole lot of people is so badly predicted to the lapel-button habit that they would join anything just so long as they get a lapel-button to show for it."

"a whole lot of people is so badly predicted

to the lapel button habit they join anything"

"But this here Legion of Honor must be a pretty good fraternal-insurance proposition at that," Morris observed, "because it says here in the paper where several New York bankers has gone into it, which it's a mighty hard thing to separate them fellers from their money even with first-class, A-number-one, gilt-edged, two-name commercial paper, and if this here Legion of Honor was just a lapel-button affair which assessed its members every time they had a death claim to pay, you could take it from me, Abe, not one of them bankers would of went near it, so maybe[Pg 53] it would be a good thing if we looked into it, Abe."

"If you want to join this here Legion of Honor, that's your business, Mawruss," Abe said, "but I already belong to the Independent Order Mattai Aaron, which I've been paying them crooks for three years now that I should get a sick benefit fifteen dollars a week without being laid up with so much as tonsillitis even."

"About the sick benefit I wasn't thinking about at all," Morris declared; "but you take a feller like Sam Feder, president of the Kosciusko Bank, for instance, and if we should be maybe next year a little short and wanted an accommodation from two to three thousand dollars, y'understand, it wouldn't do us no harm if we could give him the L. of H. grip for a starter. Am I right or wrong?"

"Say!" Abe exclaimed. "The chances is that when them New York bankers gets back to New York they will want to forget all about joining this here L. of H."

"Why, what is there so disgraceful about joining the L. of H.?" Morris asked.

"Nobody said nothing about its being disgraceful, because lots of decent, respectable fellers is liable to make a mistake of that kind, understand me," Abe said; "but you take one of these here members of the firm of—we would say, for example, J. G. Morgan, y'understand, which comes back from Paris after joining this here L. of H., and what happens him? The first morning he comes down to the office wearing[Pg 54] an L. of H. button, Mawruss, everybody from the paying-teller up is going to ask him what is the idea of the button, and he is going to spend the rest of the day listening to stories about people joining insurance fraternities which busted up and left the members with undetermined sentences of from three to five years, y'understand. The consequence would be that if any of his depositors expect to get an accommodation by giving him the L. of H. grip or wearing an L. of H. button, y'understand, they might just so well send him an invitation to a banquet where, in order to gain his confidence and respect, they are going to drink champagne out of an actress's slipper, and be done with it. Am I right or wrong?"

"Well, you couldn't exactly blame them fellers which joined the L. of H.," Morris observed, "because Paris has a very funny effect on some of the most level-headed Americans which goes there without their families and business associates, which if this here League of Nations had been fixed up at a Peace Conference held somewheres down on Lower Broadway instead of the Quai d'Orsay, Abe, the chances is that the United States Senate would of had a whole lot more confidence in it than they have at present."

"Say!" Abe explained. "This here League of Nations could of been pulled off in Paris or it could of been pulled off in a respectable neighborhood like Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, Mawruss, for all the spare time it gave the fellers which framed it to indulge in any wild night life.[Pg 55] Take, for instance, the proposed constitution and by-laws, which was printed on three pages of the newspaper the other day, Mawruss, and anybody which dictated that megillah to a stenographer would be too hoarse for weeks afterwards to order so much as a plain Benedictine. Also, Mawruss, nobody which didn't lead a blameless life could have a brain clear enough to understand the thing, let alone composing it, which last night I sat up till two o'clock this morning reading them twenty-six articles, Mawruss, and ten grains of asperin hardly touched the headache which I got from it."

"Naturally," Morris said, "because when Mr. Wilson wrote that constitution, Abe, he figured that people which is going to read it has got a better education as one year in night school."

"Sure, I know," Abe agreed, satirically, "but at the same time everybody ain't such a natural-born Harvard gradgawate like you are, Mawruss, and furthermore, Mawruss, it's a big mistake for Mr. Wilson to go ahead on the idea that we are, y'understand, because, so far as I remember it, the Constitution of the United States didn't say that this was a government of the college gradgawates by the college gradgawates for the college gradgawates, y'understand; neither did the Declaration of Independence start in by saying, 'We, the college gradgawates of the United States,' Mawruss. The consequences is that most of us ingeramusses which has got one vote apiece, even around last November already, begun to[Pg 56] feel neglected, and you could take it from me, Mawruss, if Mr. Wilson tries to win the confidence of the American people with a few more of them documents with the twin-six words in them, y'understand, by the time he gets ready to run for President again, Mawruss, the only people which is going to vote for him would be the Ph.D. and A.M. fellers."

"Well, Mawruss," Abe said, a few days after the conversation above set forth, "I see that President Wilson got back to America after a rough passage."

"Was he seasick?" Morris asked.

"Not a day," Abe replied.

"Then that accounts for it," Morris commented.

"Accounts for what?" Abe asked.

"Doctor Grayson being an admiral," Morris replied, "which a couple of years ago, when Mr. Wilson appointed Doctor Grayson to be an admiral over the heads of a couple of hundred fellers which had been captains of ships for years already, a lot of people got awful sore about it, and now it appears that he got the appointment because he can cure seasickness."

"I suppose if Doctor Grayson could cure locomotive ataxia the President would of appointed him Director-General of Railroads," Abe remarked.

"For my part, Abe," Morris said, "if I had a good doctor like Doctor Grayson attending me, and it was necessary to appoint him to something in order to keep him, Abe, I would appoint him a field-marshal, just so long as he could make[Pg 57] me comfortable on an Atlantic trip in winter-time."

"But there isn't no office in the army or navy that President Wilson could appoint Doctor Grayson to which would have been a big enough reward if Doctor Grayson could have made the President feel comfortable in Washington when he got there, Mawruss," Abe said, "which I see by the paper this morning that thirty-seven United States Senators, coming from every state in the Union except Missouri, suddenly discovered they was from Missouri, in particular the Senator from Massachusetts, and not only does them Senators want to know what the meaning of that constitution of the League of Nations means, but they also give notice that, whatever it means, they are going to knife it, anyway."

"Sure, I know," Morris said; "they're like a lot of business men you and me has had experience with, Abe. They claim a shortage and kick about the quality of the shipment before they even start to unpack the goods. Why don't they wait till Mr. Wilson goes back and finishes up his job?"

"They haven't got the time," Abe replied, "because the session ends on March 4th at noon, just about twenty-four hours before Admiral Grayson is paying his first professional call on President Wilson aboard the George Washington, and by the time Congress gets together again President Wilson expects to have the League of Nations proposition sewed up so tight that there[Pg 58] will be nothing left for them Senators to do but to indorse it."

"But, as I understand it, them Senators just loafed away their time during the end of the session and didn't pass a whole lot of laws which they should ought to have passed, Abe, so that it will be necessary for President Wilson to call an extra session in a few days," Morris said.

"That's what them Senators figured," Abe agreed, "but they was mistaken, Mawruss, because the President ain't going to run any chances of being interrupted while he is working on this here Peace Conference by S O S messages from Washington to please come home if he wants to save anything out of the wreck Congress is making of the inside of the Capitol."

"But I thought that before he went to Europe in the first place, Abe, President Wilson said to Congress that it wouldn't make any difference to them about his being in Europe, because he was in close touch with them, and that the cables and the wireless would make him available just as though he was still living in the White House," Morris said.