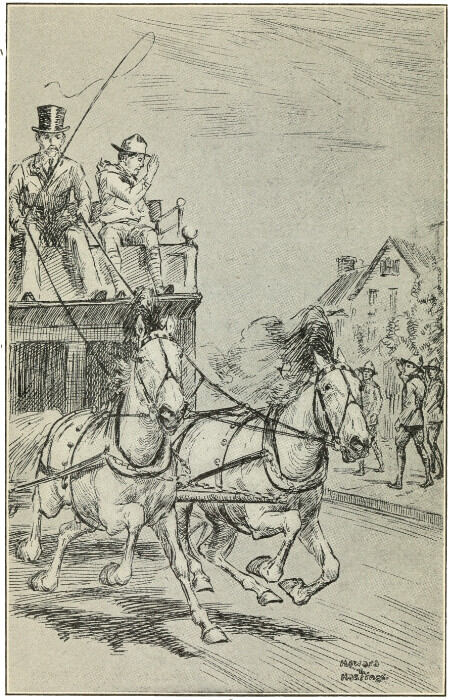

“I GAVE THEM THE SCOUT SALUTE.”

Title: Roy Blakeley, Pathfinder

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh

Illustrator: Howard L. Hastings

Release date: November 14, 2006 [eBook #19815]

Most recently updated: June 26, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by James Eager and revised by Roger Frank from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/royblakeleypathf00fitz |

“I GAVE THEM THE SCOUT SALUTE.”

ROY BLAKELEY,

PATHFINDER

By

PERCY KEESE FITZHUGH

Author of

TOM SLADE, BOY SCOUT, TOM SLADE

WITH THE COLORS, TOM SLADE ON

THE RIVER, ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

Published with the approval of

THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS : : NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1920, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

CONTENTS

| I | Hello, Here I Am Again |

| II | An Awful Wilderness |

| III | Undaunted! |

| IV | Go! |

| V | I Go on an Errand |

| VI | I Discover Some Tracks |

| VII | I Meet the Stranger |

| VIII | Up a Tree |

| IX | Awful Sticky |

| X | I Make a Promise |

| XI | Seeing Is Believing |

| XII | Marshal Foch |

| XIII | Around The Camp-Fire |

| XIV | But I Didn’t Write It |

| XV | No! No! No! Go On! Go On! |

| XVI | The Mystery |

| XVII | Appalling! Wonderful! Magnificent! |

| XVIII | On to Glory |

| XIX | Jib Jab, Is He Human? |

| XX | The Parade |

| XXI | We Visit The Side Show |

| XXII | Brent Gaylong |

| XXIII | Brent’s Story |

| XXIV | The Light In The Woods |

| XXV | In The Dark |

| XXVI | Dorry And I And The Cricket |

| XXVII | We Take Harry Into Our Confidence |

| XXVIII | In The Woods |

| XXIX | Jib Jab And Harry |

| XXX | Jib Jab Is Surprised |

| XXXI | Jib Jab’s Story |

| XXXII | Jib Jab Turns Out To Be Human |

| XXXIII | We Part Company |

| XXXIV | A Good Idea |

| XXXV | What I Heard On The Telephone |

| XXXVI | Up The Trail |

| XXXVII | A Voice |

| XXXVIII | We Fight And Run Away |

| XXXIX | Welcome Home |

| XL | Mmm-Mm-M-M! |

ROY BLAKELEY, PATHFINDER

This story is all about a hike. It starts on Bridge Street and ends on Bridge Street. Maybe you’ll think it’s just a street story. But that’s where you’ll get left. It starts at the soda fountain in Warner’s Drug Store on Bridge Street in Catskill, New York, and it ends at the soda fountain in Bennett’s Candy Store on Bridge Street in Bridgeboro, New Jersey. That’s where I live; not in Bennett’s, but in Bridgeboro. But I’m in Bennett’s a lot.

Believe me, that hike was over a hundred miles long. If you rolled it up in a circle it would go around Black Lake twenty times. Black Lake would be just a spool—good night! In one place it was tied in a bowline knot, but we didn’t count that. It was a good thing Westy Martin knew all about bowline knots or we’d have been lost.

Harry Donnelle said it would be all right for me to say that we hiked all the way, except in one place where we were carried away by the scenery. Gee, that fellow had us laughing all the time. I told him that if the story wasn’t about anything except just a hike, maybe it would be slow, but he said it couldn’t be slow if we went a hundred miles in one book. He said more likely the book would be arrested for speeding. I should worry. “Forty miles are as many as it’s safe to go in one book,” he said, “and here we are rolling up a hundred. We’ll bunk right into the back cover of the book, that’s what we’ll do.” Oh boy, you would laugh if you heard that fellow talk. He’s a big fellow; he’s about twenty-five years old, I guess.

“Believe me, I hope the book will have a good strong cover,” I told him.

Then Will Dawson (he’s the only one of us that has any sense), he said, “If there are two hundred pages in the book, that means you’ve got to go two miles on every page.”

“Suppose a fellow should skip,” I told him.

“Then that wouldn’t be hiking, would it?” he said.

I said, “Maybe I’ll write it scout pace.”

“I often skip when I read a book, but I never go scout pace,” Charlie Seabury said.

“Well,” I told him, “this is a different kind of a book.”

“I often heard about how a story runs,” Harry Donnelle said, “but I never heard of one going scout pace.”

“You leave it to me,” I said, “this story is going to have action.”

Then Will Dawson had to start shouting again. Cracky, that fellow’s a fiend on arithmetic. He said, “If there are two hundred pages and thirty lines on a page, that means we’ve got to go more than one-sixteenth of a mile for every line.”

“Righto,” I told him, “action in every word. The only place a fellow can get a chance to rest, is at the illustrations.”

Dorry Benton said, “I wish you luck.”

“The pleasure is mine,” I told him.

“Anyway, who ever told you, you could write a book?” he asked me.

“Nobody had to tell me; I admit I can,” I said.

“How about a plot?” he began shouting.

“There’s going to be a plot forty-eight by a hundred feet,” I came back at him, “with a twenty foot frontage. I should worry about plots.”

Harry Donnelle said he guessed maybe it would be better not to have any plot at all, because a plot would be kind of heavy to carry on a hundred mile hike.

“Couldn’t we carry it in a wheelbarrow?” Will wanted to know.

“We’d look nice,” I told him, “hiking through a book with the plot in a wheelbarrow.”

“Yes, and it would get heavier too,” Westy Martin said, “because plots grow thicker all the time.”

“Let’s not bother with a plot,” I said; “there’s lots of books without plots.”

“Sure, look at the dictionary,” Harry Donnelle said.

“And the telephone book,” I told him, “It’s popular too; everybody reads it.”

“We should worry about a plot,” I said.

By now I guess you can see that we’re all crazy in our patrol. Even Harry Donnelle, he’s crazy, and he isn’t in our patrol at all. I guess it’s catching, hey? And, oh boy, the worst is yet to come.

So now I guess I’d better begin and tell you how it all happened. The story will unfold itself or unwrap itself or untie itself or whatever you call it. This is going to be the worst story I ever wrote and it’s going to be the best, too. This chapter isn’t a part of the hike, so really the story doesn’t begin till you get to Warner’s Drug Store. You’ll know it by the red sign. This chapter is just about our past lives. When I say, “go” then you’ll know the story has started. And when I finish the pineapple soda in Bennett’s, you’ll know that’s the end. So don’t stop reading till I get to the end of the soda. The story ends way down in the bottom of the glass.

Maybe you don’t know who Harry Donnelle is, so I’ll tell you. He was a lieutenant, but he’s mustered out now. He got a wound on his arm. His hair is kind of red, too. That’s how he got the wound—having red hair. The Germans shot at the fellow with red hair, but one good thing, they didn’t hit him in the head.

He came up to Temple Camp where our troop was staying and paid us a visit and if you want to know why he came, it’s in another story. But, anyway, I’ll tell you this much. Our three patrols went up to camp in his father’s house-boat. His father told us we could use the house-boat for the summer. Those patrols are the Ravens and the Elks and the Solid Silver Foxes. I’m head of the Silver Foxes.

The reason he came to camp was to get something belonging to him that was in one of the lockers of the house-boat. I wrote to him and told him about it being there and so he came up. He liked me and he called me Skeezeks. Most everybody that’s grown up calls me by a nickname. As long as he was there he decided to stay a few days, because he was stuck on Temple Camp. All the fellows were crazy about him. At camp-fire he told us about his adventures in France. He said you can’t get gum drops in France.

Gee, I wouldn’t want to live there.

After he’d been at camp three or four days, Harry Donnelle said to me, “Skeezeks, are you game for a real hike—you and your patrol?”

I said, “Real hikes are our specialties—we eat ’em alive.”

“I don’t mean just a little stroll down to the village or even over as far as the Hudson,” he said; “but a hike that is a hike. Do you think you could roll up a hundred miles?”

“As easy as rolling up my sleeves,” I told him. “We’re so game that a ball game isn’t anything compared with us. Speak out and tell us the worst.”

He said, “Well, I was thinking of a little jaunt back home.”

“Good night,” I told him, “I thought maybe you meant as far as Kingston or Poughkeepsie, But Bridgeboro! Oh boy!”

“Of course, we wouldn’t get very far from the Hudson,” he said, “and we could jump on a West Shore train most anywhere, if you kids got tired.”

“The only thing we’ll jump on will be you—if you talk like that,” I said; “Silver Foxes don’t jump on trains. But how about the other fellows—the Elks and the raving Ravens? United we stand, divided we sprawl.”

He said, “Let them rave; I’m not going to head a whole kindergarten. Eight of you are enough. Who do you think I am, General Pershing?” And then he ruffled up my beautiful curly hair and he gave me a shove—same way as he always did. “This is not a grand drive,” he said, “it’s a hike. Just a few shock troops will do.”

“We’ll shock you all right,” I said, “but first you’d better speak to Mr. Ellsworth (he’s our scoutmaster), and get the first shock out of the way.”

“I think I have Mr. Ellsworth eating out of my hand,” he said; “you leave that to me. I just wanted to sound you and find out if you were game or whether you’re just tin horn scouts—parlor scouts.”

“Well, do I sound all right?” I said. “Believe me, there are only two things that keep us from hiking around the world, and those are the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean.”

“Think you could climb over the Equator?” he said, laughing all the while. And he gave me another one of those shoves—you know.

Then he said, “Well then, Skeezeks, I’ll tell you what you do. You call a meeting of the Foxes and lay this matter on the table——”

“Why should I lay it on the table?” I said; “you’d think it was a plate of soup. I’ll stand on the table and address them, that’s what I’ll do.”

He said, “All right, you just picture the hardships to them. Tell them that for whole hours at a time, we may have to go without ice cream sodas. Tell them that we’ll have to penetrate a wilderness where there is no peanut brittle. Tell them that we’ll have to enter a jungle where gum drops are unknown. Tell them that we may have to live on grasshoppers. Tell them about the vast morass near Kingston, where you can’t even get a piece of chocolate cake; miles and miles of barren waste where the foot of white man has never trod upon a marshmallow——”

“Sure you can find marshmallows in the marshes,” I said. “We should worry.”

“You ask Willie and Tommy and Dorrie and the others if they are prepared to make the sacrifice—and I’ll do the rest. I’ll speak to Mr. Ellsworth. But remember about the heartless desert with its burning sands just above Newburgh. Now go chase yourself and round them up. I guess you know how to do it.”

So I got all the Silver Foxes into our patrol cabin and gave them a spooch. I guess I might as well tell you who they all are. First there’s me—I mean I. Correct, be seated. You learn that in the primary grade. I’m patrol leader and it’s some job. Then comes Westy Martin; he’s my special chum. My sister says he has dandy hair. Then comes Dorry Benton—he’s got a wart on his wrist. Then comes Huntley Manners—Badleigh, that’s his middle name. Sometimes we call him Bad Manners. Then comes Charlie Seabury and then comes Will Dawson and then come Tom Warner and Ralph Warner—they’re twins. They’re both better looking than each other—that’s what Pee-wee Harris said. He’s a scream—he’s in the raving Raven patrol. Thank goodness he isn’t in this story—not much anyway. Ralph says Tom is crazy and Tom says Ralph is crazy and Will Dawson says they’re both right. I guess we’re all crazy. Anyway, Ralph and Tom came from Maine, so they’re both maniacs, hey?

This is the speech I spooched:

Fellow Foxes:

Shut up and give me a chance to talk. Sit down, Bad Manners. I’ve got something to tell you and don’t all shout at once——

Good night! They all began shouting separately. Then I said:

Harry Donnelle says he’s going to hike it all the way home to Bridgeboro. He says we can go with him if we want to. Our time is up Saturday, but we’ll have to start three or four days sooner.

He said for me to sound you fellows, but believe me, there’s so much sound that I can’t. I suppose the other patrols will go back down the Hudson in the house-boat. Every fellow that’s in favor of hiking it home with Mr. Harry Donnelle, will say aye—but don’t say it yet. He said to tell you that we take our lives in our hands——

“Why can’t we put them in our duffel bags?” Westy shouted.

“Did you think we’d take them in our feet?” Dorry yelled.

Then they all began shouting, “Aye, aye, aye!” even before I told them about the forests and morasses and jungles and deserts and things. Honest, you can’t do anything with that bunch.

One thing about Harry Donnelle, he was a dandy fixer. When he fixed the camouflage for us so we could watch a chipmunk, I knew he was a good fixer. He said he learned how in France. He fixed the chimney on the cooking shack, too. That fellow could fix anything.

But a scoutmaster isn’t so easy to fix. Lots of times I tried to fix it with Mr. Ellsworth and I just couldn’t. He’d make me think that I wanted to do his way. He’s awful funny, he can just make you think that there’s more fun doing things his way. And I was trembling in my shoes—I mean I was trembling in my bare feet—for fear Harry Donnelle wouldn’t be able to fix it with him. But that fellow could fix it with the sun to shine—that’s what Mr. Burroughs said.

Pretty soon he came strolling down to the spring-board where a lot of us were having a dip in the lake.

“All right,” he said, “how about you?”

“Did you fix it?” I asked him.

“All cut and dried,” he said; “are you ready for the big adventure?”

That afternoon we had a special troop meeting, to find out how the fellows felt about splitting the troop for the journey home. Because you see our three patrols always hung together. Mr. Ellsworth made a speech and said how Harry Donnelle had offered to lead the fierce and fiery Silver Foxes through the perilous wilds of New York State. He said that the journey would be filled with interest and data of scientific value (that’s just the way he talked) and how we hoped to cross the Ashokan Reservoir and visit other wild places. He said that we planned to enter the heart of the Artists Colony at Woodstock and see the artists in their native state and stalk some authors and poets, maybe, and study their habits.

Oh boy, you ought to have seen Harry Donnelle. He just sat there on the edge of Council Rock (that’s where we have important meetings at Temple Camp) and laughed and laughed and laughed.

Mr. Ellsworth said, “It is hoped that these brave scouts may succeed in capturing a poet and bringing him home as a specimen, and that they may find other fossils of interest. Meanwhile, the Ravens and the Elks and myself will drift down in our house-boat and endeavor to find someone to tow us from Poughkeepsie to New York and up our own dear river to Bridgeboro. The Ravens and the Elks wish me to offer the brave explorer, Mr. Harry Donnelle, a vote of thinks for taking the Silver Foxes away. They appreciate that he does this for the sake, not of the Silver Foxes, but as a good turn to the Ravens and the Elks. The Ravens and the Elks hope to have a little peace meanwhile. They thank him. In the familiar words of one of our famous patrol leaders, ‘we should worry.’ And we wish you all good luck in your daring enterprise.”

I could see that he winked at Harry Donnelle and Harry Donnelle was laughing so hard that he couldn’t make a speech. So I climbed up on Council Rock and shouted, “Hear, hear!” Then I made a speech and this is it, because afterwards I wrote it out in our troop book.

The Silver Foxes thank the Ravens and the Elks for their kind wishes. I bequeath all my extra helpings of dessert to Pee-wee Harris of the Ravens—up to three helpings. After that it reverts to Vic Norris of the Elks. Reverts means goes to. Who ever reaches Bridgeboro, New Jersey, first will send out a searching part for the others. The searching party will bring their own eats. If we’re never heard of again, that’s a sign you won’t hear from us. If we get to Bridgeboro and don’t find you, that’ll be a sign that you’re not there. If you are there it won’t be our fault. We should worry. We go forth for the sake of prosperity—I mean posterity. So please tell posterity in case we don’t reach home safely. If our friends and parents are anxious, tell them to wait at Bennett’s on Bridge Street, because that’ll be the first place we go to.

The next day was Wednesday and we started early in the morning. The others were going to start down in the house-boat on Saturday. I think the Ravens and the Elks must have sat up all night making crazy signs on cardboard just so as to guy us. And Mr. Ellsworth helped them, too. They had the whole camp with them—even Uncle Jeb; he’s manager. He used to be a trapper.

When we got out onto the main road, we saw signs tacked up on all the trees and I guess every scout in camp was there. One of the signs read, Olive oil, but not good-bye. Another one read Day-day to the brave explorers. Another one read, Don’t forget to wear rubbers going through the Newburgh morass. Another one read, Beware of the treacherous Ashokan Reservoir. A lot we cared. Didn’t people even make fun of Christopher Columbus?

But remember, I told you that the hike didn’t really begin till we got to Catskill. The reason I don’t count the hike from Temple Camp to Catskill is because we were all the time hiking down there. It wasn’t a hike, it was a habit. I wouldn’t be particular about three or four miles. Besides, I wouldn’t ask you to take them, because they’ve been used before. I wouldn’t give you any second hand miles.

When we got to Catskill we bought some egg powder and bacon (gee, I love bacon) and coffee and sugar and camera films and mosquito dope and beans and flour and chocolate. You can make a dandy sandwich putting a slice of bacon between two slabs of chocolate. Mm-um! We had a pretty good bivouac outfit, because the Warner twins have a balloon silk shelter that rolls up so small you can almost put it in a fountain pen—that’s what Harry Donnelle said. Dorry Benton had his aluminum cooking set along, saucepans, cups, dishes, coffee pot—everything fits inside of everything else. One thing, we wouldn’t starve, that was sure, because we had enough stuff to make coffee and flapjacks for more than a week, counting six flapjacks to every fellow and fourteen to Hunt Manners; oh boy, but that fellow has some appetite! We had plenty of beans, too. Don’t you worry about our having plenty to eat.

When we got through shopping, we went to Warner’s Drug Store for sodas. Harry Donnelle said he’d treat us all, because maybe, those would be the last sodas that we’d ever have. As we came along we saw Mr. Warner standing in the doorway and he was smiling with a regular scout smile.

“There’s something wrong,” I said; “there’s some reason for him smiling like that.”

“Have a smile for everyone you meet,” Will Dawson began singing.

But, believe me, I know all the different kinds of smiles and there was something funny about Mr. Warner’s smile. When we got inside we saw a big sign hanging on the soda fountain. It read:

A LAST FAREWELL

TO THE SILVER PLATED FOXES

BEFORE THEY ENTER THE JUNGLE

By that I knew that some of the fellows up at camp had been down to Warner’s the night before and put it there, because they knew that would be the last store we’d go to.

Harry Donnelle said, “All right, line up.” So we all sat in a row and some summer people who were in there began to laugh. What did we care? One girl said she wished she was a boy; girls are always saying that. So that proves we have plenty of fun. I could see Harry Donnelle wink at Mr. Warner while the latter (that means Mr. Warner) was getting the sodas ready. Then all of a sudden Harry said:

“Attention! Present spoons. Go!”

So then we all started at once and that was the beginning of the big hike. Just as I told you, it started at the top of the glasses in Warner’s and ended in the bottom of the glasses at Bennett’s. When you hear me say M-mm-that’s good in Bennett’s, you’ll know the hike is over.

“Now to skirt the lonesome Catskills,” Harry said.

“Now to what them?” Dorry Benton asked him.

“Skirt them,” he said, “that’s Latin for hiking around the edge of them. We don’t want to be all the time stumbling over mountains.”

“Believe me, if I see one in the road, I’ll tell you,” I said.

“And we don’t want to get mixed up with panthers and wild cats either,” Harry said. And he gave me a wink.

“There aren’t any wild animals in the Catskills,” Charlie Seabury said.

“There are wild flowers,” I said, “but they won’t hurt anybody.”

“How about poison ivy?” Westy Martin said.

All the while as we hiked along the road toward Saugerties, we kept joking about the wild animals in the Catskills. Harry Donnelle said there used to be lots of wild cats and foxes, but not any more. He said there were some foxes, though.

Westy said, “I bet there are some bears; once Uncle Jeb saw a bear; he said there weren’t any foxes any more.”

“I guess there are some grey ones and maybe a few silver,” Harry Donnelle said.

“Silver?” I shouted. “Oh boy!” Then I asked him what they fed on mostly.

“Mostly on ice cream sodas,” he said; “they’re very dangerous after a half dozen raspberry sodas.”

We didn’t go near Saugerties, because we wanted to keep in the country, so we hit down southwest along the road that goes to Woodstock. Then we were going to hike it south past West Hurley so we’d bunk our noses right into the Ashokan Reservoir. And the next day we were going to spend trying to keep out of Kingston.

When it got to be about five o’clock in the afternoon, we hit in from the road to find a good place to camp. Maybe you think that’s easy, but you have to find a place where the drainage is good and where there’s good drinking water.

Pretty soon we found a dandy place about a quarter of a mile off the road, and we put up our tent there.

Harry Donnelle said, “There’s one kind of wild animal that I forgot to mention and I guess we’ll be hunting them all right; that’s mosquitoes. I guess one or two of you kids had better hit the trail for the nearest village and complete our shopping before we get any further. What do you say? We’re a little short on mosquito dope and we ought to have some crackers, and let’s see, a little meat would go good. I’m hungry.”

When we turned into the woods from the road, we knew that we were coming to a village and I guess that’s what put the idea into Harry’s head to have somebody go there and get two or three things that we hadn’t been able to get in Catskill. I told him that I’d go, because the rest would be busy getting in fire wood and I said it would be good if two or three of them tried to catch some fish in the brook.

Oh boy, I had hardly said that, when Ralph Warner shouted that he had a perch and that the brook was full of them. Harry Donnelle went over and saw for himself how it was, and then he came back and said to me that as long as there seemed to be plenty of fish I needn’t bother about meat, but that I’d better go and see if I could scare up some more mosquito dope and some sinkers for fishing and a trowel to dig bait with, because if we liked the place we might stay there till noon the next day. That’s the best way on a long hike—take it easy.

“How about Charlie Seabury?” I said; “he doesn’t like fish.”

“All right, get him a couple of chops, then,” Harry said; “now can you remember all the things you’re going to get? Mosquito dope, fishing sinkers, a writing pad and some stamps, and let’s see——”

“Some crackers,” I said.

“Righto,” he shouted after me.

I went back through the woods and when I got to the road I noticed how it curved, and just then I saw a very narrow path on the opposite side of the road that led into the woods. I decided it must be a short cut to the village. So I started along that path.

Pretty soon the woods grew very thick and it wasn’t so easy to follow the trail, because it was all overgrown with bushes. But I managed to keep hold of it all right, and after about fifteen minutes I came to a little stone house with the windows all boarded up and the door standing a little open. There was a staple on the door with an old padlock hanging on it, but I guess the padlock wasn’t any good. One thing sure, nobody lived there. I went and peeked inside and saw that it wasn’t meant for people at all, because there wasn’t any floor and it was all dark and damp and there were lots of spider webs around. Even there was one across the doorway, so by that I knew that nobody had been there lately.

Right in the middle, inside, were a couple of rocks and water was trickling up from under them. That’s what made me think that the place was just a spring house. Anyway, I didn’t wait because I was in a hurry. When I came out I pushed the door open a little and then I closed it all but about a foot or so. Inside of an hour I was mighty sorry that I hadn’t left it wide open, and you’ll see why.

I guess I had gone about a hundred yards further when I noticed something in the trail that started me guessing. It was the print of an animal; or anyway, if it wasn’t, I didn’t know what else it was. There were six prints, something like a cat’s, only the paw that made them had five toes. The other mark was the paw mark. It was the biggest print that I ever saw.

The first animal I thought about was a wild cat. But of course, I knew there weren’t any wild cats right there. Even if there were any in that part of the country, they wouldn’t be roaming around near villages. Anyway, the five toe prints had me guessing, because a wild cat has only four. I could see that the animal must have been crossing the path, because the print was sideways and the bushes alongside of the path were kind of trampled down.

You can bet I took a good look in those bushes for hairs, but I couldn’t find any and I kept wondering what kind of an animal had a paw as big as a man’s hand and five toes.

After I had gone a little further, I came plunk on a whole line of them along the path. I wasn’t exactly scared, but anyway, they made me feel sort of funny, because they were so big and printed so plain. The animal that made those tracks must have been a pretty big animal, I knew that.

Then, all of a sudden, I discovered something else. Some of the prints had five toe marks and some of them only four. Maybe that means the animal was lame, I said to myself, and doesn’t make a full print with one of its feet. But in a minute I had sense enough to see that wasn’t the way it was, because there were always two of one kind pretty close together and then two of the other kind pretty close together. This is the way it was; there was a five toe print then another one about a foot in back of it, then about three or four feet in back of that a couple more about a foot apart with only four toe marks.

Good night! I They had me all flabbergasted.

Pretty soon they left the path altogether and I looked in the bushes for hairs, but I couldn’t find a single one.

“Anyway,” I said to myself, “one thing sure, that animal has five toes on his front feet and only four on his hind feet and I never saw any tracks like that before or even pictures of them.”

I wasn’t exactly scared, but just the same I was kind of glad when I got to the village.

Anyway, that was the smallest village I ever saw to have such big tracks right near it. All I could see was two houses and the post office, and the post office was so small that you could almost put your arm down the chimney and open the front door. But, one thing sure, you could buy everything you wanted in that post office. You could buy a plough or a lollypop or anything. It smelled kind of like corn inside.

I got some lead sinkers and some crackers and a couple of chops for Charlie Seabury, because it makes him thirsty to eat fish—that’s what he says. The man didn’t have any mosquito dope, but there were some boxes of fly paper on the counter and I just happened to think that if we stayed in our bivouac camp the next morning, it might be good to have some on account of the flies at dinner time. So I bought a box full.

Then I said to the man, “I guess there are wild animals around here.”

He said, “Wall, I reckon thar daon’t be many no more. Yer ain’t expectin’ ter catch ’em with fly paper, be yer?”

“Just the same,” I told him, “I saw the tracks of one that must be big enough to eat this whole village. You’d better put the village in the safe before you go home. Safety first.” You can bet I know how to jolly if it comes to jollying. “I want to get some rope, too,” I told him.

He just leaned back and pushed his great big straw hat to the back of his head and looked over his spectacles and began to grin. He kept his spectacles ’way down near the end of his nose.

“Ye’re one of them scaouts, hey?” he said. “Yer ain’t thinkin’ to lead any elephants home with that thar rope naow, be yer?”

I said, “No, I’m going to use the rope to lasso mosquitoes as long as you haven’t got any mosquito dope.”

He said, “Wall naow, ye’re quite a comic be’nt yer?”

I told him I was a little cut up and my mother and father couldn’t do anything with me.

“’N what else can I do fer yer?” he said, laughing all the while. “Them tracks wuz caow tracks, youngster, so daon’t yer be sceered of ’em.”

I told him I wasn’t scared of any tracks, not even a railroad track and that I’d buy the village for seventy-five cents, if he’d send it C. O. D. He just stood there laughing. Anyway, it makes me mad when grown up people jolly scouts about tracking and signaling and all that, just as if it was only play. Because what do they know about tracks? Who ever heard of a cow with feet like a cat? Good night! And, besides, often it turns out that scouts are right. You wait and see.

Now the things I bought I had in a kind of a flat bundle and I hung it over my back, because I like to have my hands free. What’s the use of wasting your hands? You’ll never find anything out with your back; all your back is good for, is bundles.

I didn’t have any adventures on the way back till I got to that spring house in the woods. I was in such a hurry that I didn’t even notice the tracks again. That’s how much I was afraid of them. When I got to the spring house, I went in for a drink of water, and believe me, it was good. I squeezed in, instead of opening the door wide, because it scraped so hard on the ground that it was easier to do that than to open it; and I did the same coming out.

I was just going to start along the path again, when I got a good idea. That’s just the way you get them, sudden like. I decided to shinny up a tree that was there and see if I couldn’t squint our camp over in the west, because if I could once see it, maybe I’d be able to get to it by a shorter way than by the path. I did that because it was getting late.

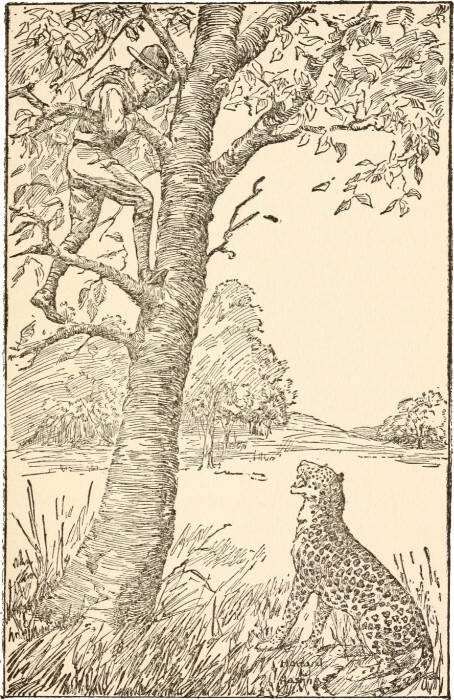

When I got up to the second branch I looked off to the west, but all I could see was a little smoke curling up into the sky, and I wasn’t sure whether it was from our camp or from some house. The sun was going down over that way and all the clouds were kind of red on the edges and the sky looked dandy. At Temple Camp they’d be just about washing up for supper then. I thought I could tell about where the road was, but I couldn’t decide about the camp and I was just going to shinny down and hit the trail when I heard a kind of a sound like leaves rustling and then a funny sort of growl, different from anything I had ever heard before. I looked around and then I saw, coming through the woods, an animal with big spots on it and a long tail. I guess it was almost as big as a tiger; anyway, it was a good deal bigger than a wild cat. It was making a noise as if it was grumbling to itself, then all of a sudden, it opened its mouth wide, as if it was going to roar, but it didn’t. It came almost up to the tree and stood still and its tail hung on the ground and wriggled like a snake.

I have to admit that I was good and scared. I just held onto the tree and didn’t make a move; I guess I hardly breathed. Then, all of a sudden, the branch I was standing on cracked.

Good night!

First I thought I was going to fall, but I reached up and got hold of the branch above and scrambled up to it. The animal was crouching on the ground, looking up, and its eyes were just like fire. Its tail was wriggling just like a snake. Oh boy, I was scared.

But anyway, I wasn’t rattled. There’s a difference between being scared and rattled. That’s one thing scouts don’t get—rattled. I looked down and saw him there and I knew I was in a mighty dangerous fix, but that only made me think harder. It seemed to me that that animal must be a leopard because he had spots, but of course, I knew there weren’t any leopards in America. Africa is where they hang out. But you can bet I didn’t think much about how he happened to be there. He was there, and that was enough for me. Gee, I like natural history all right, but not when there’s a wild animal just below me. Nix! He was crouching and he looked just as if he was going to make a spring for the tree. Mr. Ellsworth says that most fights are won by quick thinking, so I knew that if I could only think of something to do quicker than that animal could spring, I’d be all right.

First I thought I’d just shinny down and run and maybe he wouldn’t follow me. That was a punk think. All of a sudden he opened his mouth wide and kind of hissed at me and came just about two or three inches closer to the tree.

Then, all in a jiffy I had a—you know—what do you call those things? An inspiration. I pulled the bundle around from my back and tore it open and tore open the paper that the two chops were in. Charlie Seabury says he ought to have the gold cross because he saved my life, but I don’t see it. Do you? Just because I was bringing the chops to him. He says he made a sacrifice. I should worry.

Even the sound of the paper crunching made the animal move a little nearer and hiss louder and paw the ground with one of its fore feet. I guess in a couple more seconds he would have had me, but I just threw one of the chops right at him and he pounced on it.

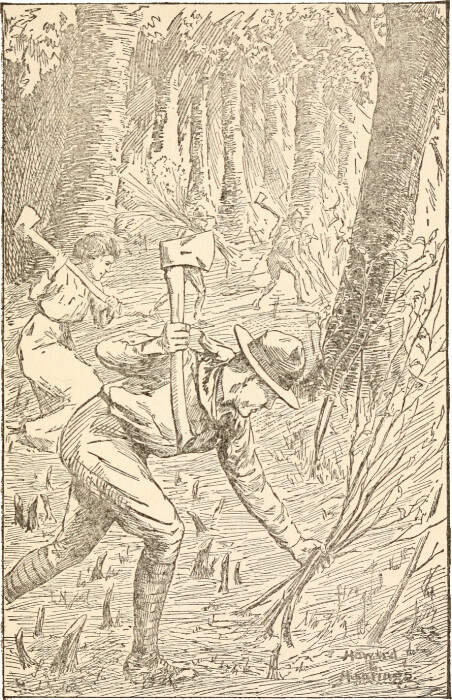

THE ANIMAL WAS CROUCHING ON THE GROUND, LOOKING UP.

That gave me two or three seconds to think. Because you can see for yourself that if an animal is ready to eat a boy scout it wouldn’t take him very long to eat a chop. Maybe you’ll say it wasn’t good to give him raw meat, but how about me. Wasn’t I raw meat? It was better to give him the chop and have a few seconds to think than to let him do the thinking and get me.

That was the time when I did some thinking in four or five seconds. Gee whiz, you have to think quick at school exams, but cracky, leopards are worse than school principals, I should hope. Anyway, they’re just as bad.

Now was the time I wished that I had left the door of the spring house open a little wider, because I had a dandy idea. As long as the animal knew what it was I was throwing, he’d go after the other chop when I threw it. Because chops were his favorite food, I could see that. So if I could only just throw the other chop into the doorway he’d go in there after it, and while he was eating it I’d shinny down in a hurry and shut the door and wedge a board against it. I said to myself that I could do that quicker than he could eat the chop, and one thing sure, he wouldn’t bother with me while he was doing it. An animal can never think about two things at once and he thinks about food most of all. Maybe scouts think about food a lot, too, but anyway, they can think about two things at once. That’s the difference between scouts and wild animals.

Oh, if I had only left that door wide open! Then I could have thrown the other chop right through the opening and ’way into the house. But now I had to throw it down and almost around a corner, as you might say; and even if the meat went in at all, it wouldn’t go in far. But if I could only throw it in far enough so that I could slam the door shut, that would be enough.

Anyway, I saw that if I didn’t throw it quick I’d be worse off than before, because the animal had had a taste of raw meat and he’d be on the war path. I could see he was looking up at me and his eyes were blazing and he was making a sound that gave me the shudders. It seemed as if he was giving me notice that he was going to spring for the tree. I guess he would have done it that very second, too, only he noticed a leaf stuck to his paw and I guess it bothered him, because he raised his paw just as a cat does when she washes her face, and rubbed it off.

Oh boy, that made me think of something, but you can bet there wasn’t any time to stop and think then. I guess I felt as nervous as William Tell when he was going to shoot the apple off his son’s head. Only I had the chop in my hand instead of a bow and arrow. Oh, didn’t I watch that open space and take a good aim! My heart was just pounding and my wrist hurt, because my pulse was going so fast. Because, suppose I should miss? I’d be the third chop, I knew that. I just couldn’t throw the chop for fear I’d miss. You can see for yourself that was the only chance I had. All of a sudden I happened to think about tearing the chop in half and that would give me two chances. But if one of the pieces landed inside maybe it wouldn’t be big enough to keep him busy two or three seconds. So I decided to take a good careful aim and throw the whole chop. If it went in, all right; maybe I’d have time enough. If it didn’t——

All of a sudden, I heard the animal give a kind of a hissing growl and I just closed one eye and braced myself against the tree and took a good, long, careful aim and threw the chop.

It struck the edge of the door and fell outside the little stone house. Almost before I saw where it landed, the animal had it.

I just crouched there in that tree shuddering and waiting for what would happen next. First I thought I’d take a chance and drop down and run. Then I decided I wouldn’t. I didn’t exactly decide. I stayed where I was, because I was too scared to move. I didn’t even dare to climb higher for fear the animal would hear me and give a spring. I could even feel my teeth chattering.

Now that it was too late, I could see that if I had only landed that meat inside the house, it would have been easy to get away. And the animal would have been a prisoner, too, because he could never have got out of that house. The windows were boarded on the inside and the door was good and heavy. But what was the good of thinking about that when it was too late?

I have to admit that for about half a minute I wasn’t a good scout. I was just scared and excited and I didn’t do anything. Then I saw the animal prowling around the tree and looking up and heard him making that noise. Oh boy, it was terrible!

Then, bang, just like that, I remembered about him wiping the leaf off his paw by rubbing it on his face. It was lucky for me he did that, because it put into my head something I had read, about the way the natives in India catch tigers. I read it in a natural history book. There’s a kind of a tree in India named the prauss tree; anyway, it’s something like that. And it has big flat leaves. So the natives spread gum on those leaves. They get the gum from the trees, too. Then they put the leaves in the path and when the tiger comes along he steps on them and rubs his paws over his face, so as to get the leaves off. But that only makes it worse for him, because they stick to his face and over his eyes and everywhere. He gets just plastered up with them. Then he gets excited—gee whiz, you can’t blame him. And he rolls around on the ground and can’t see and just rolls and rolls and bangs against trees and gets all played out and then he lies still just like a horse does when he falls down. And that’s when the natives come and get him. And it’s easy, too, because he can’t see and all the fight is knocked out of him.

Oh boy, wasn’t I glad I remembered that! I just tore out that box of fly paper and pulled the sheets apart and dropped them on the ground. Some of them fell upside down. I should worry. I tried to drop them so they’d fall around the foot of the tree and a lot of them did. More than half of them fell right side up. A couple of them stuck to the trunk, but I didn’t care. Maybe that would be good, I thought. Believe me, in about ten seconds I had the ground around the tree covered with fly paper. He’d have to do a fancy two-step if he wanted to get between them.

All the while he was crouching and watching me with those two eyes that were just like fire. Pretty soon a sheet of fly paper drifted down right near him and he pawed it. Maybe he thought it was a chop, hey? It just caught his paw and he tried to wipe it off against his face. Good night! There he was with one of his eyes and the whole top of his head plastered flat. He looked as if he had been in a fight.

Then he came closer to the trunk, pawing at his head all the time and stepped, kerflop, right on another sheet—plunked his foot right down in the middle of it. Oh bibbie, then you should have seen him! He tried to rub it off against his head and it stuck there and then there was a circus. He rolled over on the ground and caught another sheet against his side. In another second he had one flopping on the end of his tail and he kept going around after it until pretty soon it got stuck to one of his legs. Jiminetty! But you should have heard him howl. I bet he was mad clean through.

But safety first—oh boy! I dropped another one and it landed right on his nose; lucky shot.

By now he was acting just like a cat having a fit and howling like mad. I guess he couldn’t see at all, because he went, kerplunk, up against a tree and then rolled away and went banging against the spring house. He had two sheets on his face and another one on his paw and the whole front of him was all mucked up with gum and the grass and dirt were sticking to him. Believe me, he was a sight. He didn’t look much like a lord of the jungle; he looked more as if he was on his way home from the hospital.

You can talk about tanks and machine guns and poison gas and hand grenades, and all the other new fangled weapons, but tanglefoot for mine; that’s what I say. If the Allies had used tanglefoot, the war would have been over three years ago. And if they had spread it all along the banks of the Marne, the Germans would never have gotten across, that’s one sure thing.

Honestly, inside of five minutes that wild animal was a wreck. Every time he tried to claw the paper from his head he howled, because it pulled his hair and hurt him. I don’t say I was glad to sit up there and watch him, because there isn’t much fun in seeing animals suffer. Maybe he wasn’t suffering, but anyway, he was half crazy. But how about me? Safety first.

Pretty soon he kind of half rolled and half staggered over against the trunk of my tree and I knew he couldn’t see at all. Then he lay there with his back up against it trying to rub the sheet off his back, and all the while he kept pawing his head and making it worse for himself. I guess even if he had gotten the paper off, he’d still be blind, because the gum would keep his eyes shut.

By that time I knew I was safe, because he was even more helpless than he would have been if I had shot him and not killed him. It was mostly because he couldn’t see, and that got him rattled, and you’re no good when you’re rattled. All I wanted was for him to get away from the tree so I wouldn’t have to be too near him, and then I’d shinny down and hit the trail for camp.

But just then I had another thought. Maybe you won’t believe me, but I felt sorry for that wild animal. I knew how I’d feel if I was in such a fix as that. If I had only had a pistol I would have shot him, but boy scouts don’t carry pistols—only in crazy story books. We never shoot anything, except the chutes in Coney Island, and you can’t call that cruelty to animals.

And if I just went off and left him there, maybe he’d stagger around in the woods and claw at himself and tear himself all to pieces and get all bloody and just die. That wouldn’t be much fun, would it? As soon as I wasn’t scared any more I felt sorry for him—that’s the honest truth. I saw how he was beaten and I felt sorry for him. I knew he was really stronger than I was, and that it wasn’t a fair fight. I don’t care what he intended to do, it wasn’t a fair fight. Even if I had shot him he might have looked brave and noble, kind of. But with all that stuff on him and the dirt and grass sticking to his fur, I just sort of felt as if nobody has a right to make an animal look like that.

So I took the rope and made a lasso knot in it and let myself down the trunk as far as I dared. I have to admit I was sort of scared, but you have to be decent when you win. You have to be, even if it’s only a wild animal.

I tried two or three times to get the noose over his head, but I couldn’t, because he wasn’t still enough. But after a couple of minutes I managed it and then I tied the other end of the rope to the tree. After that, I climbed away out to the end of the lowest branch and it bent down with me and I dropped to the ground.

First I thought I’d go over and touch him to see how he felt, but I just didn’t dare to. I was scared of him even then. So I just started off along the path, going scout pace, and when I got a little way off so I knew I was safe, I looked back and said, “You stay where you are and don’t get excited, and I’ll fix it for you.”

Because anyway, I hadn’t done my good turn yet and it was pretty near dark.

The fellows were just thinking about sending a couple of scouts to hunt for me when I went running pell-mell into camp, shouting that I had captured a leopard.

“A what?” Westy asked.

“A leopard,” I shouted, “as sure as I stand here. Come and see for yourselves. He’s tied by a rope; he’s got fly paper all over him!”

“How many sodas did you have?” Harry Donnelle asked me.

I said, “That’s all right, you just come and see. It’s a leopard; you can see it for yourself.”

Harry said, “Sit down, Kiddo, and rest and have a cup of coffee. Guess you fell asleep by the wayside, hey? Tell us all about your dream. Here’s a plate of beans. Did you see any mermaids?”

“Never you mind about beans and mermaids,” I told him; “one man told me already that they were cow tracks I saw. I guess he wouldn’t want to go through what I’ve been through since then. The animal had five toes on his fore feet and four on his hind feet—that’s a leopard, I’m pretty sure. Anyway, he’s got spots. You come and see.”

“You don’t think it could have been a spotted calf, do you, Kid?” Harry said in that nice easy way he has of jollying. “I don’t know much about calves’ toes, but I’ve eaten calves’ feet.”

Even after I had told them all about it, they all said I must have been seeing things and that probably the animal was a raccoon or maybe possibly a wildcat. Anyway, Harry Donnelle said they’d all go back with me to the place, because they thought maybe we’d get in trouble on account of plastering some honest, hard working calf with fly paper. But just the same he took his rifle, I noticed that. I carried the lantern.

All the way through the woods they were jollying me and calling me Roy the Leopard Killer, and Harry Donnelle said I must have been carried off on the magic carpet to India, just like the people in the Arabian Nights. All the while I didn’t say anything and when we came to the tree and the spring house, I went ahead and saw that the animal was lying close to the tree, as if he were asleep. I guess he was all exhausted. The rope was fast around his body just behind his fore legs where it couldn’t choke him and where he couldn’t get free of it. He started up when I went near him, but didn’t seem to get excited.

I just held the lantern and said, “You see what a fine calf this is. He ought to win a prize at the County Fair. He’s disguised as a leopard, but he can’t fool us—I mean you fellows. You can bet boy scouts know a calf when they see one.”

They just stood there about fifteen or twenty feet off, staring. Even Harry Donnelle stood stark still, staring. “What’s the matter?” I said. “Are you afraid of a poor calf? Come down in the front row; I won’t let him hurt you.”

Then Harry came nearer, but the other fellows stood over near the spring house, so they could scoot inside, I suppose. The Safety First Patrol!

Harry Donnelle just looked and then he said, “By—the—great—horn—spoon! It’s a leopard.”

“I thought maybe it was a nanny goat,” I said.

He just shook his head and looked at the animal all over and said, “Jumping Christopher! That’s a leopard, as sure as you live.”

“Well, if you insist,” I said.

“I never heard of a leopard on the North American Continent,” he said, shaking his head.

“I guess he swam over, hey?” I said.

“Jingoes, I hate to shoot him,” he said.

By now all the bold, brave, heroic Silver Foxes began coming closer to get a good pike at the leopard. Every time the animal stirred, they’d back away again. Once the leopard stood up and pulled against the rope and rubbed his paw over his face, and gee whiz, you should have seen that bunch scatter. Dorry Benton went scooting into the well house.

But pretty soon they all saw that there wasn’t any fight left in that wild beast. He wasn’t suffering, but he was blind and all exhausted. Even still none of us exactly liked to touch him and we didn’t get too near; even I didn’t, I have to admit it.

Harry Donnelle held the lantern over toward the animal and looked at him ever so long, as if he just couldn’t believe his eyes. “He’s a magnificent specimen,” he said; “I’d give a good deal to know how he happened in these parts.”

“Oh,” I said, “the woods are full of them, they were prowling all around here when I came through. One of them was about twice as big as that.” Oh boy, you should have seen those fellows look around through the woods. Will Dawson went into the spring house to get a drink of water; he was thirsty all of a sudden.

All the while Harry Donnelle was kind of pondering and then he said, “A couple of you kids go into the village and get a wheelbarrow or a cart or something. I don’t think this fellow is in pain; I’m going to take him alive. I can’t put a bullet into him. I never saw such a magnificent specimen.”

“Suppose we should meet some more,” Hunt Manners said, just as he and Westy were starting along the path.

“Take some fly paper with you,” I said, “and think of your brave patrol leader.”

“You won’t meet any more,” Harry Donnelle said; “this fellow must have strayed down out of the mountains. There is a species of leopard found in America, but I never knew they grew to such a size as this, or had spots either. Trot along and get back as soon as you can.”

While the two fellows were gone, Harry tied the leopard’s fore feet and then his hind feet together with rope. He wound it around good and plenty and tied it fast, you can bet, and then we just sat around waiting.

Pretty soon along came the whole village, postmaster and all, and Hunt and Westy with a wheelbarrow. Some escort! You’d think Westy and Hunt were General Pershing getting home from France. I should think they would have been afraid someone would steal the village while they were gone. Because you know yourself that there are lots of robberies and hold-ups and thefts and things since the war.

I was sitting up on a branch of a tree when they came along and I heard the postmaster saying that Cy Berry had lost his heifer and he guessed maybe now it was found.

I shouted, “You have one more guess. I think the leopard ate his heifer; he was terribly hungry.”

Well, you should have heard them as soon as they had a look at the animal. One of them said, “I haint seed no leo-pods around these parts—neverrr. And I been livin’ here nigh on to forty year.”

Harry Donnelle said, “Well, the animal is a leopard just the same. Either you’ve been staying home most of the time or else he has.” I had to laugh, it was so funny the way he said it.

Another one said, “There be’nt no leopards in the Catskills, that’s sartin.”

“Well, maybe he was just spending the summer here then,” Harry said; “but here he is, anyway, and I’d like to get him away from here.”

“Yer be’nt goin’ ter try to keep him, be yer?” the man asked.

Harry said, “Yes, I’m just that reckless. I think he’s worth more alive than dead, if I can spruce him up a bit.”

“Ye’ll get yer hand bit off,” one of the men said.

Then Harry said that all he wanted was a place to put the animal till morning, and he’d see if he couldn’t get some kind of medicine to dope him with, while he tried to get the fly paper off. I guess they didn’t like the idea very much, but one of the men whose name was Hasbrook, said we could put the leopard in his barn till morning if we wanted to. So they got him into the wheelbarrow and it wasn’t hard doing it on account of his legs being tied. Then we all started back to the village.

While we were going along Harry said, “I’ve often heard of a man having an elephant on his hands, but never a leopard. Maybe we’ll have to shoot him, but I just hate to do it. I have an idea that gasoline will melt that stuff, only we’ll have to be careful about his eyes. I’d try it to-night, only I’m afraid to use the gasoline near a lamp. I’m going to send a line to the Historical Museum people though, to-night, and one of you kids can drop it at the office. I daresay there’s a train out of this burg in a few days.”

I just couldn’t help saying to him, “I’ll be glad if you don’t shoot him—I will.”

He laughed and gave me a rap on the head and said, “You see I know what it is to be shot, Kiddo. I was shot twice in France. Maybe I’m not much use, but I’d be less use if I was shot, wouldn’t I? Nobody’s much good after they’re shot. Ever think of that?”

“Maybe I didn’t,” I said, “but anyway, I know you’re right. I guess you’re always right. Anyway, I think the same as you do.”

“Shooting is no fun,” he said; “don’t shoot till you have to. What do you say?”

I said, “You’re right, that’s one sure thing and I’m glad I met you, you bet.” And you bet I was glad, because he was one fine fellow. Maybe he was kind of wild sort of, but he was one fine fellow. Mr. Ellsworth said so, and he ought to know.

When we came into the village, there was a Fraud car standing in front of a house and a man just getting out of it.

“Whatcher got thar, Cy?” he called.

“A leo-pod,” Cy called back, “an honest ter goodness leo-pod.”

“Who’s them fellers? The posse?” the man asked.

“What posse?” Cy called.

“I thought mebbe you’d caught up with that beast from Costello’s. That you, Hiram? Taint no reg’lar leo-pod is it?”

“Reg’lar as church goin’; look on ’em yourself.”

Harry Donnelle just stood there smiling. Then he said, “Have a look; it won’t cost you a cent.”

After the man had looked and Harry had told him all about it, he hauled out of his overalls a newspaper and said, “Lookee here.”

We all crowded around him and Harry held the lantern so we could see the paper.

“Jest fetched it from Kingston,” the man said.

Then Harry began reading out loud. This is what he read, because I pasted that article in our hike record book:

WILD ANIMAL AT LARGE

INFURIATED LEOPARD ESCAPES FROM VISITING

CIRCUS—ARMED POSSE SEARCHING WOODS

While transferring one of the leopards from a cage to a parade wagon at Costello’s Circus yesterday, the animal becoming frightened at the sudden striking up of the brass band, forced his way between the two barred enclosures and made its escape from the circus grounds.

An attempt to shoot it as it crouched beneath a Roman chariot in panic fright was unsuccessful, and before its keeper was joined by others with revolvers, the animal had sped through the adjacent fields, frightening some boys who were playing ball, and was last seen at the foot of Merritt’s hill, near the west turnpike road. It is supposed that the animal entered the woods and made for the mountains where a party of circus attaches and volunteer citizens, fully armed, hope to encounter and destroy it.

No serious damage was done by the animal, except the tearing of a tent which had not yet been raised, as it tore at a rope in which its leg became entangled.

When seen this morning Mr. Rinaldo Costello, owner of the circus, said that no fear need be entertained by citizens, as the animal would undoubtedly avoid human haunts. He added that little hope is entertained of catching the beast alive, as these animals are always taken when cubs, and when grown, fight to the death all efforts to capture them. The escaped animal, a magnificent specimen of the leopard family, was imported by Mr. Costello at a cost of more than six thousand dollars. In captivity it was said to be comparatively docile. The leopard is distinctive among animals of the cat family, in having five toes on its fore paws and four on its hind paws, this being its unique characteristic. It is said that few full grown leopards have ever been captured by man, and their value is hence greater than that of all other animals save the giraffe, which is said to be all but extinct. This leopard was known as Marshall Foch, and was a favorite with all the circus people.

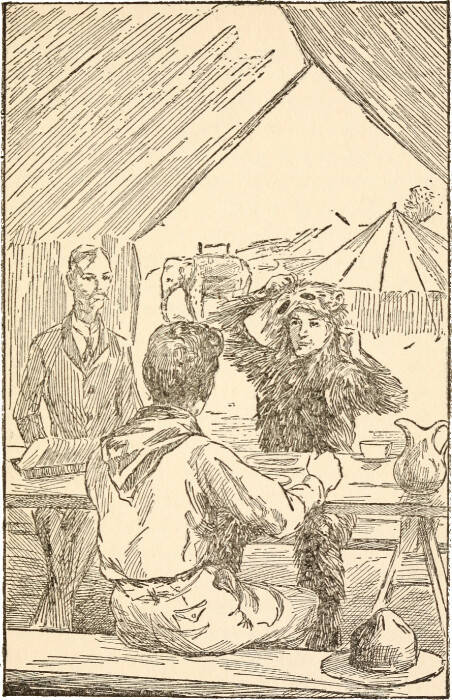

As soon as we got the leopard into Mr. Hasbrook’s barn, we made a hay bed in one of the stalls and laid him there. I felt awful sorry for him now that I knew about his history. And I wished that he had never come near me, but got away into the mountains. Harry Donnelle held the lantern into the stall and he looked so helpless lying there, with his feet tied together and grass and dirt all over him and the fly paper on his face, that I kind of blamed myself. Anyway, I was glad that his people liked him and missed him. Maybe he’d be glad to get back, hey?

Harry said, “Good night, Marshal Foch, and good luck to you. Just have a little patience.”

He was awfully nice, Harry was. That was just the way he talked.

Before we went into the house he said, “Suppose three or four of you kids go back and bring our stuff here and we’ll camp right here on the spot till we get through with this business.” So the Warner twins and Will Dawson went back by the road and the rest of us went in the house with Harry and Mr. Hasbrook.

When we got in the parlor, Harry looked over the paper and found a big ad. This is how it read:

COSTELLO’S MAMMOTH SHOW!

THREE DAYS IN KINGSTON.

BEASTS OF THE JUNGLE.

WORLD’S CONGRESS OF FREAKS.

DARING ACROBATS.

JIB JAB, THE WORLD’S MYSTERY.

SEE HIM!

IS HE HUMAN?

GRAND STREET PARADE TO-MORROW.

AT THREE P. M. SEE THE ELEPHANTS.

FREE! FREE! FREE!

TWO PERFORMANCES DAILY.

COME!

GRANDEST COMBINATION OF WONDERS

EVER GATHERED UNDER CANVAS.

SUPERB SPECTACLE

GORGEOUS! STUPEFYING!

ASTOUNDING!

Harry Donnelle said, “I rather like Mr. Costello already; he’s so modest. I bet he’s one of those quiet, retiring little ‘after you, please’ men that blushes when you speak to him. We’ll just drop him a line and one of you kids can hike it over to Saugerties and catch an early train down to Kingston and hand it to him.”

I said, “I’ll go.”

But he said, “No, you’ve had adventures enough and if they ever get you in a circus they’ll keep you there in the congress of freaks.” So it was decided that Dorry Benton would go.

While we were waiting for the fellows to come back with our stuff, Harry wrote the letter and this is what he said. It’s copied word for word out of our hike record:

Mr. Rinaldo Costello, Proprietor,

Costello’s Mammoth Show.

Kingston, N. Y.

Dear Sir:

This is to inform you that your leopard, Marshall Foch, has been captured by a boy scout and is alive and well, save that he is suffering from nervous shock and requires to have his face washed.

You may call in your armed posse. You are greatly mistaken in supposing that leopards may not be captured alive. It requires only the proper apparatus.

The bearer of this letter will give you any further information which you may require, and we shall be glad to see you here, as soon as it may be convenient for you to call.

Respectfully,

HARRY C. DONNELLE,

In charge of Boy Scouts en route. Silver Fox Patrol,

Bridgeboro, New Jersey. Stopping on farm of Mr. Silas

Hasbrook, Bently Centre, N. Y.

After a little while the fellows came back with our stuff and we put up our tent between a couple of trees in Mr. Hasbrook’s orchard. He said we could camp in the house if we wanted, but how can anybody camp in a house, I’d like to know? You might as well talk about going swimming in a bath tub. No siree, the orchard for us. Mr. Hasbrook said we could eat all the apples we wanted to, but we didn’t eat many. I ate five—that isn’t very many.

We gathered some sticks and started a camp-fire and I made coffee and flapjacks and scrambled eggs with egg powder. Mr. Hasbrook’s daughter brought us out some pie and um, um, wasn’t it good! Oh boy, it was nice sprawling around there. But anyway, we turned in early—one o’clock in the morning is early. You couldn’t turn in much earlier or it would be the night before. I guess we wouldn’t have turned in then, except that Dorry had to roll out at about six, so as to catch the train down to Kingston.

Harry Donnelle said, “I suppose Mr. Rinaldo Costello will send a mammoth, astounding, bewildering, astonishing, amazing, stupifying, extraordinary, remarkable, dazzling, baffling, cavalcade after Marshal Foch, as soon as he gets our staggering, unbelievable, incredible letter.”

We were all of us just sprawling around the fire and Harry was sitting on a little three legged milking stool and kind of guying Costello’s mammoth show, in that funny way he had, and saying that Mr. Costello would probably say I was a matchless, intrepid, dauntless, fearless hero and adventurer, when all of a sudden that word adventurer put a thought into my head.

I said, “When it comes to being a dauntless, fearless adventurer, I guess nobody has anything on you, that’s one thing sure.”

“Oh, I’ve had a few games of basketball,” he said.

“I bet you’ve been to lots of places,” I told him.

He said, “Well, I’ve attended one or two pink teas and strawberry festivals. Once I was usher at a concert in an Old Ladies’ Home. The wildest time I ever had was umpiring a game of checkers.”

“You didn’t win that Distinguished Service Cross umpiring a game of checkers,” Westy said.

“No, I won that playing hide and seek with Fritzie in No Man’s Land,” he said. “Chuck a little more wood on the fire, Roy.”

I said, “There’s one thing you never told me about, and you promised to tell it, too. It’s an adventure, but it’s a kind of a mystery, too.”

“Well,” he said, “adventures aren’t so much, but I’ll have to make an extra charge for mysteries. The high cost of mysteries is something terrible. I don’t know what the mystery may be, but if you’ll go in the house and get my cigarette case out of the pocket of my coat that’s hanging in the sitting room, I’ll let you have any mystery I happen to have in stock at the wholesale price.”

Oh bibbie, didn’t I scoot in after that cigarette case. He was always smoking cigarettes, that fellow. He told us never to do it, but he was always doing it himself. He said he was too old to reform.

When I came back I said, “It’s about that money of yours—that two hundred dollars that we found in the locker of the house-boat. It made a lot of trouble in Temple Camp, that’s one sure thing. Don’t you remember how you said that you’d tell me all about how you got it, some day?”

He said, “Oh that; that wasn’t an adventure; that was just an episode.”

“I know what episodes are all right,” I told him; “didn’t my father have a couple of them. If there’s a narrow escape, that’s a sign it’s not an episode; it’s an adventure. You can have episodes any day.

“Well, there wasn’t a very narrow escape to that one, anyhow,” he said, laughing all the while; “it was about six feet wide, I guess. But here goes, if you want it. Gather closer around the fire, because this adventure is mighty wet.”

“That’s a sure sign it’s an adventure,” I told him, “because how can an episode get wet?”

“I guess you’re right,” he said; “it might get a little damp, but not really wet. Anyway, do you think you can keep still for about ten minutes?”

The reason I said that about the two hundred dollars causing a lot of trouble at Temple Camp was, because a little fellow there named Skinny McCord (you’ll see him after a while) was suspected of stealing it. A lot of fellows thought he took it from a fellow while he was saving the fellow from drowning and then hid it in the house-boat. They thought that just because he went to the house-boat, and because they found out that he had a key to the locker. But all the while that money belonged to Harry Donnelle and he came up to Temple Camp and claimed it, after I wrote and told him all about Skinny. That’s how he happened to visit Temple Camp and you can bet I’m glad he did. Anyway, that’s all part of another story, and maybe you read it.

Now part of the story that Harry Donnelle told us, I knew already, but the other fellows didn’t, because I never told them how I had met him before. So this is the story just the way he told it to us that night, because afterward I got him to write it out for our hike record. And the reason I put it in here is, because it has something to do with the story that comes after this. So here it is, and oh boy, didn’t we listen as we sat around that camp-fire in Mr. Hasbrook’s orchard. That’s where stories are best—around the camp-fire.

HARRY DONNELLE’S YARN

Well, messmates, when my father told you that you could have the old house-boat for the summer, you never knew he had a son in the army, now, did you? But just the same, little Harry was trotting around in Camp Dix, all dolled up in his lieutenant’s uniform, waiting to be mustered out. Little Harry had just come home from France where he had been mixed up in the big—episode.

One fine day I said to myself, “While I’m waiting here, I guess I’ll go home.” So I got a short leave and the next that was seen of me I was stepping off the train in Bridgeboro. That was early in the morning; the dawn was just breaking. Pretty soon it broke. Just as it was all broken I saw Jake Holden, the fisherman, standing near the milk train. You’ll see that this is a fish story. It is a fishing episode.

That man persuaded me to go fishing with him. I knew that if I went home I’d have to meet all my sister’s friends and maybe drink tea and play tennis. So I decided to go fishing with Jake. I thought I’d be safer. I was a coward. I was afraid to go home and drink tea and play tennis. So I went up to the old house-boat where the governor had it tied up in the creek near home. The scene was dark and gloomy. It was early in the morning. Even the swamp grass wasn’t up; it was all trampled down. Not a sound could be heard—except the milkman rattling bottles up near the house.

I crept into the house-boat, took off my uniform, put it into a locker that I had the key of, and togged myself out in a set of old rags which I found there. Many were the times I had fished in those rags. I don’t know how long I stayed in the house-boat. Jake was to come through the creek in his motor boat and I was to meet him. But I was foiled—foiled by the Boy Scouts. I heard voices in the distance and pretty soon I recognized my father’s voice and the voice of Skeezeks Blakeley and the uproarious clamor and frantic utterances of Pee-wee Harris. I can hear it now, it haunts me night and day.

I didn’t wait to meet those unexpected guests. I didn’t know that the house-boat was to become theirs on an extended loan. I sneaked out and beat it through the marsh grass for all I was worth.

I love, I love, I love my home,

But, oh, you yellow perch!

So now you know of my miraculous escape from the boy scouts and the awful peril I averted of drinking tea and playing tennis. I am now approaching the darkest scenes of that frightful adventure.

After my escape from the boy scouts and my honored parent, I went fishing off the bleak and barren coast of Coney Island. I was swept by ocean breezes and the smoke from Jake Holden’s pipe. In the distance we beheld the wild and rugged scenery of Luna Park. I caught some perch, some bass, a couple of crabs, an eel, two blue fish and a bad cold. We landed at the iron pier and sold our catch to a man who keeps a restaurant and serves shore dinners.

Then we went forth again. The wind was starting to blow a gale and the smoke from Jake Holden’s pipe enveloped me like a fog. The sky grew dark. Jake wanted to lift anchor and go ashore, but I said, “No, let’s stay out, because the fish are biting.”

What happened next was my fault, not his. We stayed out there fishing in a blinding gale, the sea coming in in great rollers. Pretty soon the Luna Park tower was ’way around the corner. Either they had moved it or else our anchor was dragging.

“Jake,” I said, “we’re tearing the bottom of the ocean all to pieces; it’s a shame. We’ll be off Rockaway in about ten minutes, if this keeps up.”

“The boat’ll be all tore to pieces, you mean” he said, “and we’ll be in the bottom of the ocean if this keeps up. We’re shipping water by the bucketful. Let’s get out of this.”

So we hauled in the anchor and tried to get our power started, but it was too late. Our plug was short circuiting, the coil was gone plumb crazy, and most of the Atlantic Ocean seemed to be in the carburetor. The rest of it was on the floor. Besides all this, the pump was on a strike—shorter hours, I suppose.

Kids, we were in one dickens of a fix. It was late afternoon and there we were blowing around the ocean, bailing to keep on top, and with the land moving farther and farther away all the time. By dusk the shore was just a misty line, that was all. Every wave that hit us, meant bailing like mad to keep our gunwale above water. We took off the muffler and used it to bail with.

A dozen times we lighted our lantern and a dozen times the wind or the sea put it out. It was water-soaked, useless. I said, “Jake, it’s all up with us,” and he said he guessed it was.

Boys, I’ve gone forty-eight hours without sleeping, in France. I’ve gone three days without food. I’ve seen a shell burst into smithereens ten feet from me. But I’d rather go through all that again, I’d rather play tennis and drink tea, even, than to go through another night like that. All night we couldn’t so much as see each other’s faces. Our arms were stiff. We just bailed, bailed, bailed and kept her from swamping.

In the morning the weather eased up a little and if we had only had her running, she would have taken the seas all right. She’s a filthy little boat, but game. But an engine is never game; it’s always the boat that’s game. A gas engine is a natural born coward and a quitter. A hull will fight to the last. If our engine hadn’t lain down, we could have hit the sea crossways and we’d have skimmed over it like a car on a scenic railway. But the swell got us sideways and we swung like a hammock.

Anyhow, we could ease up a little on the bailing and before the sun was well up, we were able to use the oar. We had only one, because the other one was carried away. But we managed to keep that little jitney head-on, and pretty soon we knew it wasn’t a case of drowning, but more likely a case of starving. There wasn’t a speck of land in sight. We might have been half way to Europe for all I knew.

Well, after a while Jake said, “What’s that? Looks like a log floating.”

It didn’t look like anything much, but it wasn’t the ocean, that was sure, and we tried to make it with our oar. The thing was drifting in on us, so we didn’t have to do all the work—just get in its path. We could slacken our own drifting with the oar, so pretty soon we were alongside it and saw it was a swamped life boat. There was one man floating around in it-dead. That two hundred dollars belonged—or rather was in his pocket. There were some other things in his pockets too; some things that started me guessing. I think you kids had better tarn in now; it’s getting late.

All right, there isn’t much more. We had no guess how long the man had been in the boat or whether he had starved or what. He might have been dead several days, I thought. The life boat was awash. There was the name of some ship or other on the bows, but the boat had been painted since the name was printed there, and all I could make out was a few indistinct letters under the fresh paint. I made out an L, then DY, then NNE. I have a hunch the name was Lady Anne, but maybe not.

The man must have been a pretty rough character from all I could judge; a sailor, I daresay. It was out of the question rescuing the body. Every ounce of weight in our own boat made it worse for us, and we couldn’t have hauled it over the side without danger. So we did the next best thing and that was to go through his pockets in the hope of finding something to identify him.

You getting sleepy? No? Well, we found a weather wallet on him. Know what that is? It’s a pocket-book made of rubber. You can see them in ship supply stores all along South street in New York. In there he had two hundred and seven dollars and a letter. The writing was all smeared and some of it I couldn’t read at all. I couldn’t make out the address, but I think it was signed “Father.”

That was no place to be doping things out, with the seas rolling us goodness knows where, so I just stuffed the money in my trouser pocket, because it made too big a wad to go in my wallet. But I dried the letter as best I could and put it away in this little case I always carry. Here’s the case and here’s the letter now. And I suppose that if there’s any mystery, as you call it, why this is it.

Now just wait and don’t get excited and you’ll see the letter. Just let me finish. We pushed off from the life boat and I think it must have sunk soon afterward. The sea got pretty calm after a while and late that afternoon we were picked up by a schooner and set ashore.

Jake and I agreed to say nothing about our discovery; I’ll tell you the reason in a minute. He forgot and blurted out something about our finding a life boat and it got into the newspapers, but no harm was done, because after our rescue we gave the names of Mike Corby and Dan McCann and after we had started home, no one knew who to hunt for, even if they wanted to.

But the principal reason we gave false names was, because my leave from camp was already up and I didn’t want anybody, my own folks especially, to know that I had sidestepped home and mother to go off on a crazy fishing trip. Get me?

Jake went home and I haven’t seen him since. I hustled to Bridgeboro by train, sneaked over to Little Valley in a big hurry to change my duds and—the house-boat was gone. The boy scouts had carried away my uniform and Lieutenant Donnelle was a ragged outcast, a couple of days overdue at camp.

How to get my uniform, that was the question. The boy scouts had done me a bad turn. I traced the fugitive house-boat to St. George, Staten Island. I lurked near shore till dark, and when a party of you kids came ashore and one of you mentioned to another that a certain Roy had remained on board, I said, “Here is my chance.”

I rowed over, made his acquaintance, took him into my confidence, obtained his promise of silence, and changed my clothes. I found him a bully little scout. The old rags which went by the name of trousers I put into the locker, forgetting in my hurry, to take the two hundred and seven dollars. After fastening the locker I took some change out of my uniform to reward our young friend, but he spurned my offer. I must have dropped the locker key when I pulled the change out of my pocket. As you all know, little Skinny found it and got himself suspected of hiding the money in the locker. So much for that. I returned to camp and got slapped on the wrist for being late.

But the letter which I had taken from that dead man I had with me, and here it is now. When I visited Temple Camp upon the urgent plea of my old pal Skeezeks, I claimed the two hundred and seven dollars, but it was not mine.

It wasn’t the dead man’s either.

Now listen to this water-soaked letter, or as much of it as I can make out:

—hundred dol—is a good deal of money. — to —be careful. —such places— are likely —get robbed.

thought you—glad—get the ring. —wear —on second finger of left hand —war. —these fifty years. —real cameo—head— Lincoln. —getting along—to—make two ends meet—to each one who left our village——

There is quite a lot more, but I can’t make it out.