Title: Captain Sam: The Boy Scouts of 1814

Author: George Cary Eggleston

Release date: June 19, 2006 [eBook #18622]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by David Edwards, Sankar Viswanathan, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by David Edwards, Sankar Viswanathan,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net/)

from scanned images of public domain material

generously made available by the Google Books Library Project

(http://books.google.com/intl/en/googlebooks/library.html)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through the the Google Books Library Project. See http://books.google.com/books?vid=LCCN04016133&id |

Transcriber's Note:

The Table of Contents is not part of the original book.

Copyright.

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS.

1876.

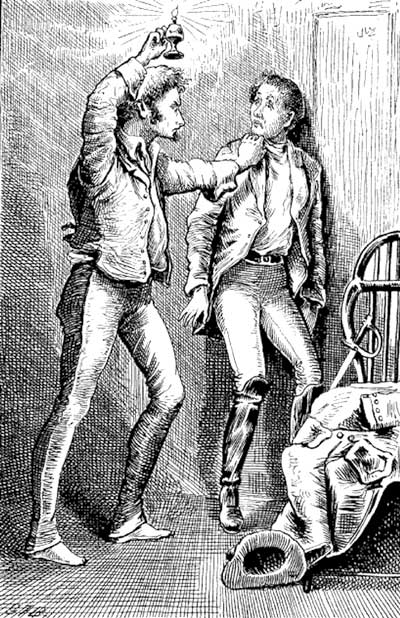

f you open your mouth again, I'll drive my fist down your throat!"

The young man, or boy rather,—for he was not yet eighteen years old,—who made this very emphatic remark, was a stalwart, well-built youth, lithe of limb, elastic in movement, slender, straight, tall, with a rather thin face, upon which there was as yet no trace of coming beard, high cheek bones, and eyes that seemed almost to emit sparks of fire as their lids snapped rapidly together. He spoke in a low tone, without a sign of anger in his voice, but with a look of earnestness which must have convinced the person to whom he ad[8]dressed his not very suave remark, that he really meant to do precisely what he threatened.

As he spoke he laid his left hand upon the other's shoulder, and placed his face as near to his companion's as was possible without bringing their noses into actual contact; but he neither clenched nor shook his fist. Persons who mention weapons which they really have made up their minds to use, do not display them in a threatening manner. That is the device of bullies who think to frighten their adversaries by the threatening exhibition as they do by their threatening words. Sam Hardwicke was not a bully, and he did not wish to frighten anybody. He merely wished to make the boy hold his tongue, and he meant to do that in any case, using whatever measure of violence he might find necessary to that end. He mentioned his fist merely because he meant to use that weapon if it should be necessary.

His companion saw his determination, and remained silent.

"Now," resumed Sam, "I wish to say something to all of you, and I will say it to you as an officer should talk to soldiers on a subject of[9] this sort. Fall into line! Right dress! steady, front!"

The boys were drawn up in line, and their commander stood at six paces from them.

"Attention!" he cried, "I wish you to know and remember that we are engaged in no child's play. We are soldiers. You have not yet been mustered into service, it is true, but you are soldiers, nevertheless, and you shall obey as such. Listen. When it became known in the neighborhood that I had determined to join General Jackson and serve as a soldier you boys proposed to go with me. I agreed, with a condition, and that condition was that we should organize ourselves into a company, elect a captain, and march to Camp Jackson under his command, not go there like a parcel of school-boys or a flock of sheep and be sent home again for our pains. You liked the notion, and we made a fair bargain. I was ready to serve under anybody you might choose for captain. I didn't ask you to elect me, but you did it. You voted for me, ever one of you, and made me Captain. From that moment I have been responsible for everything.[10]

"I lead you and provide necessary food. I plan everything and am responsible for everything. If you misbehave as you go through the country I shall be held to blame and I shall be to blame. But not a man of you shall misbehave. I am your commander, you made me that, and you can't undo it. Until we get to Camp Jackson I mean to command this company, and I'll find means of enforcing what I order. That is all. Right face! Break ranks!"

A shout went up, in reply.

"Good for Captain Sam!" cried the boys. "Three cheers for our captain!"

"Huzza! Huzza! Huzza!"

All the boys,—there were about a dozen of them—joined in this shout, except Jake Elliott, the mutineer, who had provoked the young captain's anger by insisting upon quitting the camp without permission, and had even threatened Sam when the young commander bade him remain where he was.

The revolt was effectually quelled. The mutineer had found a master in his former school-mate, and forebore to provoke the threatened corporal punishment further.[11]

The camp was in the edge of a strip of woods on the bank of the Alabama river, the time, afternoon, in the autumn of the year 1814. The boys had marched for three days through canebrakes, and swamps, and had still a long march before them. Sam had called a halt earlier than usual that day for reasons of his own, which he did not explain to his fellows. Jake Elliott had objected, and his objection being peremptorily overruled by Sam, he had undertaken to go on alone to the point at which he wished to pass the remainder of the day, and the night. Sam had ordered him to remain within the lines of the camp. He had replied insolently with a threat that he would himself take charge of the camp, as the oldest person there, when Sam quelled the mutiny after the manner already set forth.

Now that he was effectually put down, he brooded sulkily, meditating revenge.

As night came on, the camp fire of pitch pine threw a ruddy glow over the trees, and the boys, weary as they were with marching, gathered around the blazing logs, and laughed and sang merrily, Jake Elliott was silent and sullen through it all,[12] and when at last Sam ordered all to their rest for the night, Jake crept off to a tree near the edge of the prescribed camp limits and threw himself down there. Presently a companion joined him, a boy not more than fourteen years of age, who was greatly awed by Sam's sternness, and who naturally sought to draw Jake into conversation on the subject.

"You're as big as Sam is," he said after a while, "and I wonder you let him talk so sharp to you. You're afraid o' him, aint you?"

"No, but you are."

"Yes I am. I'm afraid o' the lightning too, and he's got it in him, or I'm mistaken."

"Yes 'n' you fellows hurrahed for him, 'cause you was afraid to stand up for yourselves."

"To stand up for you, you mean, Jake. It wasn't our quarrel. We like Sam, if we are afraid o' him, an' between him an' you there wa'nt no call for us to take sides against him. Besides we're soldiers, you know, an' he's capt'n."

"A purty capt'n he is, aint he, an' you're a purty soldier, aint you. A soldier owning up that he's afraid," said Jake tauntingly.[13]

"Well, you're afraid too, you know you are, else you wouldn't 'a' shut up that way like a turtle when he told you to."

"No, I aint afraid, neither, and you'll find it out 'fore you're done with it. I didn't choose to say anything then, but I'll get even with Sam Hardwicke yet, you see if I don't."

"Mas' Jake," said a lump of something which had been lying quietly a little way off all this time, but which now raised itself up and became a black boy by the name of Joe, who had insisted upon accompanying Sam in his campaigns; "Mas' Jake, I'se dun know'd Mas' Sam a good deal better'n you know him, an' I'se dun seed a good many things try to git even wid him, 'fore now; Injuns, water, fire, sunshine, fever 'n ager, bullets an' starvation all dun try it right under my eyes, an' bless my soul none on 'em ever managed it yit."

"You shut up, you black rascal," was the only reply vouchsafed the colored boy.

"Me?" he asked, "oh, I'll shut up, of course, but I jist thought I'd tell you 'cause you might make a sort o' 'zastrous mistake you know. Other folks dun dun it fore now, tryin' to git even wid Mas' Sam."[14]

"Go to sleep, you rascal," replied Jake, "or I'll skin you alive."

Joe snored immediately and Jake's companion laughed as he crept away toward the fire. An hour later the camp was slumbering quietly in the starlight, Sam sleeping by himself under a clump of bushes on the side of the camp opposite that chosen by Jake Elliott for his resting-place.

am Hardwicke had thrown himself down under a clump of bushes, as I have said, a little apart from the rest of the boys. Before he went to sleep, however, his brother Tom, a lad about twelve years of age, but rather large for his years, came and lay down by his side, the two falling at once into conversation.

"What made you fire up so quick with Jake Elliott, Sam?" asked the younger boy.

"Because he is a bully who would give trouble if he dared. I didn't want to have a fight with him and so I thought it best to take the first opportunity of teaching him the first duty of a soldier,—obedience."

"But you might have reasoned with him, as you generally do with people."[16]

"No I couldn't," replied Sam.

"Why not?" Tom asked.

"Because he isn't reasonable. He's the sort of person who needs a master to say 'do' and 'don't.' Reasoning is thrown away on some people."

"But you had good reasons, didn't you, for stopping here instead of going on further?" asked Tom.

"Certainly. There's the Mackey house five miles ahead, and if we'd gone on we must have stopped near it to night?"

"Well, what of that?"

"Jake Elliott would have pilfered something there."

"How do you know?" asked Tom in some surprise at his brother's positiveness.

"Because," Sam replied, "he tried to steal some eggs last night at Bungay's. I stopped him, and that's why I choose to camp every night out of harm's way, and keep all of you within strict limits. I don't mean to have people say we're a set of thieves. Besides, Jake Elliott has meant to give trouble from the first, and I have only waited for a chance to put him down. He isn't satisfied[17] yet, but he's afraid to do anything but sneak. He'll try some trick to get even with me pretty soon."

"Oh, Sam, you must look out then," cried Tom in alarm for his brother. "Why don't you send him back home?"

"For two or three reasons. In the first place General Jackson needs all the volunteers he can get."

"Well, what else?"

"That's enough, but there's another good reason. If I let him go away it would be saying that I can't manage him, and that would be a sorry confession for a soldier to make. I can manage him, and I will, too."

"But Sam, he'll do you some harm or other."

"Of course he will if he can, but that is a risk I have to take."

"Well, I'm going to sleep here by you, any how," said Tom.

"No you mustn't," replied the elder boy. "You must go over by the fire where the other boys are, and sleep there."

"Why, Sam?"[18]

"Well, in the first place, if I'm not a match in wits for Jake Elliott, I've no business to continue captain, and I've no right to shirk any trial of skill that he may choose to make. Besides you're my brother, and it will make the other boys think I'm partial if you stay here with me. Go back there and sleep by the fire. I'll take care of myself."

"But Sam—" began Tom.

"You've seen me take care of myself in tighter places than any that he can put me in, haven't you?" asked Sam. "There's the root fortress within ten feet of us. You haven't forgotten it have you?"

"No," said Tom, rising to go, "and I don't think I shall forget it soon; but I don't like to let my 'Big Brother' sleep here alone with Jake Elliott around."

"Never mind me, I tell you, but go to the boys and go to sleep. I'll take care of myself."

With that the two boys separated, Tom walking away to the fire, and Sam rolling himself up in his blanket for a quiet sleep. He had already removed his boots, coat and hat, and thrown them together in a pile, as he had done every night[19] since the march began, partly because he knew that it is always better to sleep with the limbs as free as possible from pressure of any kind, and partly because he suffered a little from an old wound in the foot, received about a year before in the Indian assault upon Fort Sinquefield, and found it more comfortable, after walking all day, to remove his boots.

The camp grew quiet only by degrees. Boys have so many things to talk about that when they are together they are pretty certain to talk a good while before going to sleep, and especially so when they are lying in the open air, under the starlight, near a pile of blazing logs. They all stretched themselves out on the ground, weary with their day's march, and determined to go at once to sleep, but somehow each one found something that he wanted to say and so it was more than an hour before the camp was quite still. Then every one slept except Jake Elliott. He lay quietly by a tree, and seemed to be sleeping soundly enough, but in fact he was not even dozing. He was laying plans. He had a grudge against Sam Hardwicke, as we know, and was very[20] busily thinking what he could do by way of revenge. He meant to do it at night, whatever it might be, because he was afraid to attempt any thing openly, which would bring on a conflict with Sam, of whom he was very heartily afraid. He was ready to do any thing that would annoy Sam, however mean it might be, for he was a coward seeking revenge, and cowardice is so mean a thing itself, that it always keeps the meanest kind of company in the breasts of boys or men who harbor it. Boys are apt to make mistakes about cowardice, however, and men too for that matter, confounding it with timidity and nervousness, and imagining that the ability to face unknown danger boldly is courage. There could be no greater mistake than this, and it is worth while to correct it. The bravest man I ever knew was so timid that he shrunk from a shower bath and jumped like a girl if any one clapped hands suddenly behind him. Cowardice is a matter of character. Brave men are they who face danger coolly when it is their duty to do so, not because they do not fear danger but because they will not run away from a duty. Cowards often go into danger boastfully and with[21]out seeming to care a fig for it, merely because they are conscious of their own fault and afraid that somebody will find it out. Cowards are men or women or boys, who lack character, and a genuine coward is very sure to show his lack of moral character in other ways than by shunning danger. They lie, because they fear to tell the truth, which is a thing that requires a good deal of moral courage sometimes. They are apt to be revengeful, too, because they resent other people's superiority to themselves, and are not strong enough in manliness to be generous. They seek revenge for petty wrongs, real or imaginary, in sly, sneaking, cowardly ways because—well because they are cowards. Jake Elliott was a boy of this sort. He was always a bully, and people who imagined that courage is best shown by fighting and blustering, thought Jake a very brave fellow. If they could have known him somewhat better, they would have discovered that all his fighting was done merely to conceal the fact that he was afraid to fight. He measured his adversaries pretty accurately, and in ordinary circumstances he would have fought Sam, when that young man talked to[22] him as he did in the beginning of this story. There was that in Sam's bearing, however, which made Jake afraid to resist the imperious will that asserted itself more in the quiet tone than in the threatening words. He was Sam's full equal physically, but he had quailed before him, and he could scarcely determine why. It annoyed him sorely as he remembered the loud cheering of the boys. He chafed under the consciousness of defeat, and dreaded, the hints he was sure to receive whenever he should bully any of his companions, that he had a score still unsettled with Sam Hardwicke. He knew that he was a coward, and that the other boys had found it out, and he almost groaned as he lay there in the silence and darkness, meditating revenge.

A little after midnight he got up silently and crept along the river bank to the clump of bushes where Sam lay soundly sleeping. His first impulse was to jump upon the sleeper and fight him with an unfair advantage, but he was not yet free from the restraining influence of Sam's eye and voice so recently brought to bear upon him.

No, he dared not attack Sam even with so[23] great an advantage. He must injure him secretly as he had determined to do.

Creeping along upon all-fours, he felt about for Sam's boots, and finding them at last, was just about to move away with them when Sam turned over.

Jake sank down into the sand and listened, his heart beating and the sweat standing in great drops on his forehead. Sam did not move again, however, but seemed still to sleep. After waiting a long time Jake crept away noiselessly, as he had come.

Slipping down over the low sand bank he stood by the river's edge with the boots in his hand.

"Now," he muttered to himself, "I guess I'll be even with 'Captain Sam.' By the time he marches a day or two barefoot with that game foot o' his'n, I guess he'll begin to wish he hadn't been quite so sassy."

Filling the boots with sand he swung them back and forth, meaning to toss them as far out into the river as he could. Just as he was about quitting his hold of them, a terrifying thought seized him. The sand-filled boots would make a[24] good deal of noise in striking the water, and Sam on the bank above would be sure to hear. Jake was ready enough to injure Sam, but he was not by any means ready to encounter that particularly cool and determined youth, while engaged in the act of doing him a surreptitious injury. He must go higher up the stream before putting his purpose into execution.

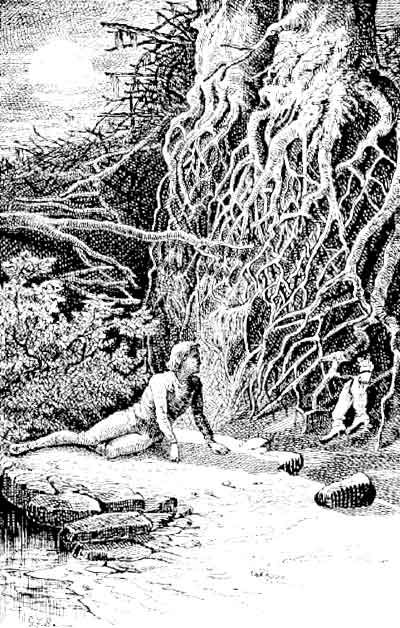

The bank at this point was crowned with a great pile of drift wood, the accumulation of many floods, which had been caught and held in its place by two great trees from the roots of which the water had gradually washed the sand away until the trees themselves stood up upon great root legs, fifteen feet long. The trees and the drift pile were the same in which Sam Hardwicke had hidden his little party a year before, when the fortunes of Indian war had thrown him, with Tom and his sister, and the black boy Joe, upon their own resources in the Indian haunted forest. The story is told in a former volume of this series.[1] Sam's resting place just now was within [25]a few feet of the great tree roots, but Sam was not sleeping there, as Jake Elliott supposed. He had been wide enough awake, ever since Jake first startled him out of sleep, and he had silently observed that worthy's manœuvres through the bushes. Jake crept along the edge of the drift pile to its further end, intending to toss the boots into the river as soon as he should be sufficiently far from Sam for safety. As he went, however, his awakened caution grew upon him. He reflected that Sam would suspect him when he should miss his boots the next morning, and might see fit to call him to account for their absence. He intended, in that case, stoutly to deny all knowledge of the affair, but he could not tell in advance precisely how persistent Sam's[26] suspicion might be, and it seemed to him better to leave himself a "hole to crawl through," as he phrased it, if the necessity should come. He resolved, therefore, that instead of throwing the boots away, he would hide them so securely that no one else could possibly find them. "Then," thought he, "if the worst comes to the worst I can find 'em, and still stick to it that I didn't take 'em away." An opening in the pile of drift-wood just at hand, was suggestive, and Jake crept into it passing under a great log that lay lengthwise just over the entrance. The passage way through the drift was a very narrow one but it did not come to an end at the end of the great log as Jake had expected, and he felt his way further. The passage turned and twisted about, but he went on, dark as it was. After a while he found himself in a sort of chamber under one of the great trees, and inside the line of its great twisted roots. He did not know where he was, however, but Sam or Tom or Joe could have told him all about the place.

[1] The Big Brother, published by G. P. Putnam's Sons. A friend suggests that many northern readers may doubt the existence of such trees as those which I have described briefly here, and more fully in "The Big Brother." I think it right to explain, therefore, that I have seen many such trees with roots exposed in the manner described, in the west and south, and my favorite playing place as a boy was under precisely such a tree. Of course no tree could stand the sudden removal of ten or fifteen feet of earth from beneath it; but the trees described have gradually undergone this process, and the roots have struck constantly deeper, their exposed parts gradually changing from roots, in the proper sense, to something like a downward-branching tree trunk.

Here his journey seemed to be effectually interrupted, and he thrust the boots, as he supposed, into a hole, driving them with some little force[27] through a tangled net work of small roots. What he really did do, however, was to drive them through a net work of small roots, between two great ones, into the outer air, at the very spot from which he had taken them. When he quitted his hold of them, leaving them, as he supposed, buried in the centre of a great drift pile, they lay in fact by Sam's coat and hat, right where they had lain when Sam went to sleep.

Sam had silently observed him as he entered the drift pile, and running quickly to the entrance he seized a stick of timber and drew it toward him with all his force. Sam Hardwicke had an excellent habit of remembering not only things that were certainly useful to know, but things also which might be useful. When Jake entered the drift pile, Sam remembered that during his own stay there a year before, he had carefully examined the great log which formed the archway of the entrance, and that it was kept in its place only by this single stick of timber acting as a wedge. Pulling this out, therefore, he let the farther end of the great tree trunk fall, and completely blocked the passage way.

o matter where one begins to tell a story there is always something back of the beginning that must be told for the sake of making the matter clear. Whatever you tell, something else must have happened before it and something else before that and something else before that, so that there is really no end to the beginnings that might be made. The only way I can think of by which a whole story could be told would be to begin back at Adam and Eve and work on down to the present time; and even then the story would not be finished and nobody but a prophet ever could finish it.

The only way to tell a story then is to plunge into it somewhere as I did two chapters back, follow it until we get hold of it, and then go back[29] and explain how it came about before going on with it. I must tell you just now who these boys were, where they were and how they came to be there. All this must be told sometime and whenever it is told somebody or something must wait somewhere, and I really think Jake Elliott may as well wait there in the drift-pile as not. He deserves nothing better.

During the summer of the year 1813, while the United States and great Britain were at war, a general Indian war came on which raged with especial violence in middle and southern Alabama. The Indians fought desperately, but General Jackson managed to conquer them thoroughly. He was empowered by the government to make a treaty with them and he insisted that they should make a treaty which they could not help keeping. He made them give up a large part of their land, and so arranged the boundaries as to make the Indians powerless for further harm.

The Indians hesitated a long time before they would sign the treaty, but it was Jackson's way to finish whatever he undertook, and not leave it to be done over again. As the people of the border[30] used to say, he "left no gaps in the fences behind him," and so he insisted upon the treaty and the Indians at last signed it. Meantime, however, a great many of the Indians, and among them several of their most savage chiefs had escaped to Florida, which was then Spanish territory.

Jackson remained at his camp in southern Alabama through the summer of 1814 bringing the Indians to terms. During the summer it became evident that the British were preparing an expedition against Mobile and New Orleans, and Jackson was placed in command of the whole southwest, with instructions to defend that part of the country. This was all very well, and very wise, too, for there was no man in the country who was fitter than he for the kind of work he was thus called on to do; but there was one very serious obstacle in his way. He had his commission; he had full authority to conduct the campaign; he had everything in fact except an army, and it does not require a very shrewd person to guess that an army is a rather important part of a general's outfit for defending a large territory. He called for volunteers and accepted any kind that came. He[31] even published a special address to the free negroes within the threatened district and asked them to become soldiers, a thing that nobody had ever thought of before.

The boys in the southwest were strong, hearty fellows, used to the woods, accustomed to hardship and not afraid of danger. Many of them had fought bravely during the Indian war, and when Jackson called for volunteers, a good many of these boys joined him, some of them being mere lads just turning into their teens.

Sam Hardwicke, was noted all through that country for several reasons. In the first place he was a boy of very fine appearance and unusual skill in all the things which help to make either a boy or a man popular in a new country. He was a capital shot with rifle or shot-gun; he was a superb horseman, a tireless walker, and an expert in all the arts of the hunter.

He was strong and active of body, and better still he was a boy of better intellect and better education than was common in that country at that early day when there were few schools and poor ones. His father was a gentleman of wealth[32] and education, who had removed to Alabama for the sake of his health a few years before, bringing a large library with him, and he had educated his children very carefully, acting as their teacher himself. Sam was ready for college, and but for Jackson's call for troops he would have been on his way to Virginia, to attend the old William and Mary University there, at the time our story begins. When it became known, however, that men were needed to defend the country against the British, Sam thought it his duty to help, and reluctantly resolved to postpone the beginning of his college course for another year.

All these things made Sam Hardwicke a special favorite, and persons a great deal older than he was, held him in very high regard, on account of his superior education, but more particularly on account of the real superiority which was the result of that education; and I want to say, right here, that the difference between a man or boy whose education has been good and one who has had very little instruction, is a good deal greater than many persons think. It is a mistake to suppose that the difference lies only in what[33] one has learned and the other has not. What you learn in school is the smallest part of the good you get there. Half of it is usually worthless as information, and much of it is sure to be forgotten; but the work of learning it is not thrown away on that account. In learning it you train and discipline and cultivate your mind, making it grow both in strength and in capacity, and so the educated man has really a stronger and better intellect than he ever would have had without education. Many persons suppose,—and I have known even college professors who made the mistake,—that a boy's mind is like a meal-bag, which will hold just so much and needs filling. They fill it as they would fill the meal-bag, for the sake of the meal and without a thought of the bag. In fact a boy's mind is more like the boy himself. It will not do to try to make a man out of him by stuffing meat and bread down his throat. The meat and bread fill him very quickly, but he isn't fully-grown when he is full. To make a man of him we must give him food in proper quantities, and let it help him to grow, and the things you learn in school are chiefly valuable[34] as food for the mind. Education makes the intellect grow as truly as food makes the body do so; and so I say that Sam Hardwicke's superiority in intellect to the boys and even to most of the men about him, consisted of something more than merely a larger stock of information. He was intellectually larger than they, and if any boy who reads this book supposes that a well-trained intellect is of no account in the practical affairs of life, it is time for him to begin correcting some very dangerous notions.

To get back to the story, I must stop moralizing and say that when Sam made up his mind to volunteer, a number of boys in the neighborhood determined to follow his example, and, as Sam has already explained, the little company was organized, under Sam's command as captain. Of course Sam had no real military authority, and he did not for a moment suppose that his little band of boys would be recognized as a company or he as a captain, on their arrival at Camp Jackson; but they had agreed to march under Sam's command, and he knew how to exercise authority, even when it was held by so loose a[35] tenure as that of mere agreement among a lot of boys.

We now come back to the drift-pile. When Jake had carefully hidden Sam's boots, as he supposed, deep within the recesses of the great pile of logs and brush and roots, he began groping his way back toward the entrance. It was pitch dark of course, but by walking slowly and feeling his way carefully, he managed to follow the passage way. Just as he began to think that he must be pretty nearly out of the den, however, he came suddenly upon an obstruction. Feeling about carefully he found that the passage in which he stood had come to an abrupt termination. We know, of course what had happened, but Jake did not. He had come to the end of the log which Sam had thrown down to stop up the passage way, and there was really no way for him to go. He supposed, of course, that he had somehow wandered out of his way, leaving the main alley and following a side one to its end. He therefore retraced his steps, feeling, as he went, for an opening upon one side or the other. He found several, but none of them did him any good. Fol[36]lowing each a little way he came to its end in the matted logs, and had to try again. Presently he began to get nervous and frightened. He imagined all sorts of things and so lost his presence of mind that he forgot the outer appearance and size of the drift pile, and frightened himself still further by imagining that it must extend for miles in every direction, and that he might be hopelessly lost within its dark mazes. When he became frightened, he hurried his footsteps, as nervous people always do, and the result was that he blacked one of his eyes very badly by running against a projecting piece of timber. He was weary as well as frightened, but he dared not give up his effort to get out. Hour after hour—and the hours seemed weeks to him,—he wandered back and forth, afraid to call for assistance, and afraid above everything else that morning would come and that he would be forced to remain there in the drift pile while the boys marched away, or to call aloud for assistance and be caught in his own meanness without the power to deny it. Finally morning broke, and he could hear the boys as they began preparing for breakfast. It was[37] his morning, according to agreement, to cut wood for the fire and bring water, and so a search was made for him at once. He heard several of the boys calling at the top of their lungs.

"Jake Elliott! Jake! Ja-a-a-ke!!" He knew then that his time had come.

What had Sam been doing all this time? Sleeping, I believe, for the most part, but he had not gone to sleep without making up his mind precisely what course to pursue. When he threw the log down, he meant merely to shut Jake Elliott and his own boots up for safe keeping, and it was his purpose, when morning should come, to "have it out" with the boot thief, in one way or another, as circumstances, and Jake's temper after his night's adventure, might determine.

He walked back, therefore, to his place of rest, after he had blocked up the entrance of the drift-pile, and threw himself down again under the bushes. Ten or fifteen minutes later he heard a slight noise at the root of the great tree near him, and, looking, saw something which looked surprisingly like a pair of boots, trying to force themselves out between two of the exposed roots. Then he heard[38] retreating footsteps within the space enclosed by the circle of roots, and began to suspect the precise state of affairs. Examining the boots he discovered that they were his own, and he quickly guessed the truth that Jake had pushed them out from the inside, under the impression that he was driving them into a hole in the centre of the tangled drift.

Sam was a brave boy, too brave to be vindictive, and so he quickly decided that as he had recovered his boots he would subject his enemy only to so much punishment as he thought was necessary to secure his good behavior afterward. He knew that the boys would torment Jake unmercifully if the true story of the night's exploits should become known to them, and while he knew that the culprit deserved the severest lesson, he was too magnanimous to subject him to so sore a trial. He went to sleep, therefore, resolved to release his enemy quietly in the morning, before the other boys should be astir. Unluckily he overslept himself, and so the first hint of the dawn he received was from the loud calling of the boys for Jake Elliott. Fortunately Jake had not yet nerved himself[39] up to the point of answering and calling for assistance, and so Sam had still a chance to execute his plan.

"Never mind calling Jake," he cried, as he rose from his couch of bushes, "but run down to the spring and bring some water. I have Jake engaged elsewhere."

The boys suspected at once that Sam and Jake had arranged a private battle to be fought somewhere in the woods beyond camp lines, a battle with fists for the mastery, and they were strongly disposed to follow their captain as he started up the river.

"Stop," cried Sam. "I have business with Jake, which will not interest you. Besides, I think it best that you shall remain here. Go to the spring, as I tell you, and then go back to the fire, and get breakfast. Jake and I will be there in time to help you eat it. If one of you follows me a foot of the way, I—never mind; I tell you you must not follow me, and you shall not."

There were some symptoms of a turbulent, but good-natured revolt, but Sam's earnestness quieted it, and the boys reluctantly drew back.[40]

Passing around to the further side of the drift-pile, more than a hundred yards away from the nearest point of the camp, Sam called in a low tone:—

"Jake! Jake!"

"What is it?" asked Jake presently, trembling in voice as he trembled in limb, for he was now thoroughly broken and frightened. He dreaded the meeting with Sam nearly as much as he dreaded the terrible fate which seemed to him the only alternative, namely, that of remaining in the drift-pile to starve.

"Come down this way," said Sam.

"Well," answered Jake when he had moved a little way toward Sam.

"Do you see a hole in the top, just above your head?" asked Sam.

"Yes, but I can't see the sky through it."

"Never mind, get a stick to boost you, and climb up into it."

Jake did as he was told to do, and upon climbing up found that there was a sort of passage way running laterally through the upper part of the timber, crooked and so narrow that he could scarce[41]ly force his way through it. Whither it led, he had no idea, but he obeyed Sam's injunction to follow it, though he did so with great difficulty, as in many places sticks were in the way, which it required his utmost strength to remove. The passage through which he was crawling so painfully, was one which Sam and his companions had made by dint of great labor, during their residence in the tree root cavern a year before. It led from the main alley way to their post of observation on top of the pile, their look-out, from which they had been accustomed to examine the country around, to see if there were Indians about, when they had occasion to expose themselves outside of their place of refuge. As the only way into this passage was through a "blind" hole in the roof of the main alley way, no one would ever have suspected its existence.

After awhile Jake's head emerged from the very top of the drift pile, and he saw Sam lying flat down, just before him. He instinctively shrank back.

"Come on," said Sam; "but don't rise up or the boys will see us. Crawl out of the hole and then follow me on your hands and knees."[42]

Jake obeyed, and the two presently jumped down to the ground on the side of the hummock furthest from camp.

Jake's first glance revealed Sam fully dressed, and standing firmly in his boots. There could be no mistake about it, and yet a moment before he would have made oath that those very boots were hidden hopelessly within the deepest recesses of the drift-pile. He could not restrain the exclamation which rose to his lips:—

"Where DID you get them boots?"

"Never mind where, or how. I have a word or two to say to you. You took my boots and were on the point of throwing them into the river. If you think such an act by way of revenge was manly and worthy of a soldier, I will not dispute the point. You must determine that for yourself."

"Let me tell you about it, Sam," began Jake in an apologetic voice.

"No, it isn't necessary," replied Sam. "I know all about it, and it will not help the matter to lie about it. Listen to me. You were about to throw the boots into the river; but you changed your mind. You know why, of course, while I can[43] only guess; but it doesn't matter. You took them into the drift pile and put them into a hole there. The next thing you know of them I have them on my feet, and I assure you I haven't been inside the drift pile since you entered it. Solve that riddle in any way you choose. I blocked up the entrance, and this morning I have let you out. Not one of the boys knows anything about this affair, and not one of them shall know, unless you choose to tell them, which you won't, of course. Now come on to camp and get ready for breakfast."

With that Sam led the way. Presently Jake halted.

"Sam," he said.

"Well."

"My eye's all bunged up. What'll the boys say?"

"I don't know."

"What must I tell 'em?"

"Anything you choose. It is not my affair."

"They'll think you've whipped me?" exclaimed Jake in alarm.

"Well, I have, haven't I?"[44]

"No, we hain't fit at all."

"Yes we have,—not with our fists, but with our characters, and I have whipped you fairly. Never mind that. You can say you did it by accident in the dark, which will be true."

"But Sam!" said Jake, again halting.

"Well, what is it now?"

"What made you let me out an' keep the secret from the boys?"

"Because I thought it would be mean, unmanly and wrong in me to take such a revenge."

"Is that the only reason?"

"Yes, that is the only reason."

"You didn't do it 'cause you was afraid?" he asked, incredulously.

"No, of course not. I'm not in the least afraid of you, Jake."

"Why not? I'm bigger'n you."

"Yes, but you're an awful coward, Jake, and nobody knows it better than I do, except you. You wouldn't dare to lay a finger on me. I could make you lie down before me and—Pshaw! you know you're a coward and that's enough about it."[45]

"Why didn't you leave me for the boys to find, then, and tell the whole story?"

"Because I'm not a coward or a sneak. I've told you once, but of course you can't understand it; come along. I'm hungry."

hree or four days after the morning of Jake Elliott's release, Sam led his little company into Camp Jackson and reported their arrival.

As Sam had anticipated, General Jackson decided at once that the boys could become useful to him only by volunteering in some of the companies already organized, and Sam began to look about for a company in which he and Tom would be acceptable. The other boys were of course free to choose for themselves, and Sam declined to act for them in the matter. As for Joe the black boy, he knew how to make himself useful in any command, as a servant, and he was resolved to follow Sam's fortunes, wherever they might lead.[47]

"You see Mas' Sam," he said, "you'n Mas' Tommy might git yer selves into some sort o' scrape or udder, an' then yer's sho' to need Joe to git you out. Didn't Joe git you out 'n dat ar fix dar in de drifpile more'n a yeah ago? Howsomever, 'taint becomin' to talk 'bout dat, 'cause your fathah he dun pay me fer dat dar job, he is. But you'll need Joe any how, an' wha you goes Joe goes, an' dey aint no gettin roun' dat ar fac, nohow yer kin fix it."

On the very morning of Sam's arrival, as he was beginning his search for a suitable command in which to enlist, he met Tandy Walker, the celebrated guide and scout, whose memory is still fondly cherished in the southwest for his courage, his skill and his tireless perseverance. Tandy was now limping along on a rude crutch, with one of his feet bandaged up.

Sam greeted him heartily and asked, of course, about his hurt, which Tandy explained as the result of "a wrestle he had had with an axe," meaning that he had cut his foot in chopping wood. He tarried but a moment with Sam, excusing himself for his hurried departure on the ground that he had[48] been sent for by General Jackson. Having heard Sam's story and plans Tandy limped on, and was soon ushered into Jackson's inner apartment.

When the general saw him he exclaimed—

"What, you're not on the sick list are you, Walker?"

"Well no, not adzac'ly, giner'l, but I ain't adzac'ly a walker now, fur all that's my name."

"What's the matter?" asked Jackson.

"Nothin', only I've dun split my foot open with a axe, giner'l."

"That is very unfortunate," replied Jackson, "very unfortunate, indeed."

"Yes, it aint adzac'ly what you might call lucky, giner'l."

"It certainly isn't!" said Jackson, a smile for a moment taking the place of the look of vexation which his face wore; "and it isn't lucky for me either, for I need you just now."

"I'm sorry, giner'l, if ther's any work to be done in my line, but it can't be helped, you know."

"Of course not. The fact is Tandy, I want something done that I can't easily find any body else to do. I'm satisfied now that the British are[49] at Pensacola and are arming Indians there, and that the treacherous Spanish governor is harboring them on his neutral territory. I have proof of that now. Look at that rifle there. That's one of the guns they have given out to Indians, and a friendly Indian brought it to me this morning. But you know the Indians, Walker; I can't get anything definite out of them. I must find out all about this affair, and you're the only man I could trust with the task."

"I b'lieve that's jist about the way the land lays, giner'l," replied Tandy, "but I'll tell you what it is; if ther' aint a man here you kin tie to fur that sort o' work, ther's a purty well grown boy that'll do it up for you equal to me or anybody else, or my name aint Tandy Walker, and that's what the old woman at home calls me."

A little further conversation revealed the fact that the boy alluded to was none other than our friend Sam Hardwicke. General Jackson hesitated, expressing some doubts of Sam's qualifications for so delicate a task. He feared that so young a person might lack the coolness and discretion necessary, and said so. To all of this Tandy replied:[50]—

"You'd trust the job to me, if I could walk, wouldn't you, giner'l?"

"Certainly; no other man would be half so good."

"Well then, giner'l, lem me tell you, that Sam Hardwicke is Tandy Walker, spun harder an' finer, made out'n better wool, doubled an' twisted, and mighty keerfully waxed into the bargain. He's a smart one, if there ever was one. He's edicated too, an' knows books like a school teacher. He's the sharpest feller in the woods I ever seed, an' he's got jist a little the keenest scent for the right thing to do in a tight place that you ever seed in man or boy. Better'n all, he never loses that cool head o' his'n no matter what happens."

"That is a hearty recommendation, certainly," said the general. "Suppose you send young Hardwicke to me; of course nothing must be said of all this."

"Certainly giner'l. Nobody ever gits any news out'n my talk." And with that Tandy made his awkward bow, his awkwarder salute, and limped away.

alf an hour later Sam Hardwicke entered General Jackson's private office, and was received with some little surprise upon the commander's part.

"Why, you're the young man who reported in command of some young recruits, are you not?" he asked.

Sam replied that he was.

"I didn't understand it so," replied Jackson, "when Walker recommended you for this service. However, it is all the better so, because I know your devotion, and Tandy has assured me of your competence. Sit down, our talk is likely to be a long one."

When Sam was comfortably seated, with his[52] hat "hung up on the floor," as Tandy Walker would have said, the general resumed.

"You understand of course," he said, "that whatever I say to you, must be kept a profound secret, now and hereafter, whether you go on the expedition I have in mind or not."

"You may depend upon my discretion, sir. I think I know how to be silent."

"Do you? Then you have learned a good lesson well. Take care that you never forget it. Let me tell you in the outset that the task I want you to undertake is a difficult and perhaps a dangerous one. It will require patience, pluck, intelligence and tact. Tandy Walker tells me that you have these qualities, and he ought to know, perhaps, but I shall find out for myself before we have done talking. I shall tell you what the circumstances are and what I wish to have done. Then you must decide whether or not you wish to undertake it; and if you do, you must take what time you wish for consideration, and then tell me what your plans are for its accomplishment. I shall then be able to judge whether or not you are likely to succeed. You understand me of course?"[53]

"Perfectly, I think," replied Sam.

"Very well then. You know that a good many of the worst of these Creeks escaped to Florida, Peter McQueen among them. I could not pursue them beyond the border, because Florida is Spanish territory, and Spain is, or at least professes to be, friendly to the United States, and neutral in our war with the British. Now, however, I have good authority for believing that the Spanish Governor at Pensacola is treacherously aiding not only the Indians but the British also. A force of British, I hear, has landed there, and friendly Indians tell me that they are arming the runaway Creeks, meaning to use them against us. The Indians tell big stories, so big that I can place no reliance upon them, and what I want is accurate information about affairs at Pensacola. If there is a British force there, it means to make an attack on Mobile or New Orleans. I must know the exact facts, whatever they are, so that I may take proper precautions. I must know the size of the force, the number of their ships, and on what terms they have been received by the Spaniards. If they are made welcome at Pensacola, and per[54]mitted by the Spaniards to make that a convenient base of operations against us, the government may see fit to authorize me to break up the hornet's nest before the swarm gets too big to be handled safely. However, that is another matter. What I want is positive information of the exact facts, whatever they are. The difficulties in the way are great. We are at peace with Spain, and must do no hostile act upon her soil. I cannot even send an armed scouting party to get the information I need. If you go, you must go unarmed, and even then you may be arrested and dealt hardly with. It will require the utmost discretion as well as courage, to accomplish the task, and I have no wish that you should undertake it if you hesitate to do so."

"I do not hesitate, sir," replied Sam, "if, after hearing my plan, you think me competent for the business."

"Very well then," replied the general, "when will you be ready to lay your plan before me?"

"I am ready now, sir," said Sam, "so far at least as the general plan is concerned; little things will have to be dealt with as they arise."[55]

"Certainly. What is your plan in outline?"

"To go to Florida on a trapping and fishing excursion. I am not a soldier yet, and may go, if I like, peacefully into the territory of a friendly nation. I can take some of my boys with me, and camp by the water side. I can easily go into Pensacola and find out what is going on there. I shouldn't wish to be a spy, general, but this is scarcely that, I think. The enemy has been received by a power professing to be friendly. That power has given us no notice of hostility, and until that is done I see no impropriety in going into his territory for information not about his affairs at all, unless he is proving treacherous, which would entitle us to do that, but about those of our enemy, whom he should regard as an invader, however he may regard him in fact."

"You've read some law, I see," said the general.

"No sir," replied Sam, blushing to think how he had been expounding to the general, a nice point which that officer must understand much better than he did. "No sir, I have read no law except a book or two on the laws of nations,[56] which my father said every gentleman should be familiar with."

"A very wise and excellent father he must be," replied Jackson, "if I may judge of him by the training he has given his son."

"Thank you, sir, in his name," answered Sam, rising and making his best bow.

"To come back to the business in hand," resumed Jackson. "You'll need a boat and some camp equipments."

"A boat, yes, but as for camp equipments, I can make out without them very well. I've camped a good deal and I know how to manage."

"Very well, then, you'll be all the lighter. How many of your boys will you need?"

"Two or three,—partly to make a show of a camp, but more because it may be necessary to send some of them back with news. My brother Tom and my black boy, with one or two others will be enough."

"Very well. Now you must be off as soon as possible. I shall march to Mobile in a day or two, and organize for defence there. Send your news there. You had better march directly from[57] this place, so that your arrival will excite no suspicion. I will provide you with a map of the country. Have you a compass?"

"Yes sir, I brought one with me from home."

"There are boats enough to be had among the fishermen, I suppose, but how to provide you with one is the most serious problem I have to solve in this matter. My army chest is empty, and my personal purse is equally so."

"I can manage all that, sir, if I may take an axe or two and an adze from the shop here."

"How?"

"By digging out a canoe. I've done it before, and know how to handle the tools."

"You certainly do not lack the sort of resources which a commander needs in such a country as this, where he must first create his army and then arm and feed it without money. You'll make a general yet, I fancy."

"At present I am not even a private," replied Sam, "though the boys call me Captain Sam."

"Do they? Then Captain Sam it shall be, and I wish you a successful campaign before Pensacola, Captain. Get your forces into marching order at[58] once. Take all of your boys, unless some of them have already enlisted,—it won't do to take actual soldiers with you, as yours must be a citizen's camp,—and march as early as you can. I'll see that you are properly provided with the tools you need."

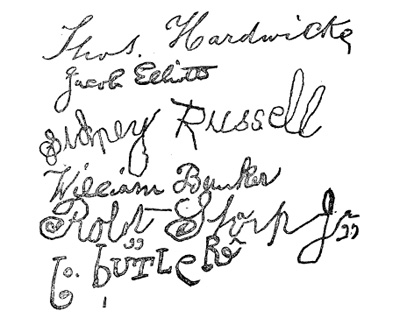

t noon the next day Sam marched away from the camp at the head of his little company, reduced now to precisely six boys in all, counting the colored boy Joe, but not counting Captain Sam himself. Jake Elliott was one of the company, rather against Sam's wish, but he had begged for permission to go, and Sam thought his size and strength might be of use in some emergency. Tommy was of the party of course, and the other boys were Billy Bunker—called Billy Bowlegs by the boys, because he was not bow-legged at all but on the contrary badly knock-kneed,—Bob Sharp, a boy of about Tommy's size and age, and Sidney Russell, a boy of thirteen, who had "run to legs," his companions said, and was already nearly six feet high, and so[60] slender that, notwithstanding his extreme height, he was the lightest boy in the company. The rest of the party had already enlisted and could not go.

The outfit was complete, after Sam's notions of completeness; that is to say, it included every thing which was absolutely necessary and not an ounce of anything that could be safely spared. For tools they had two axes, with rather short handles, a small hatchet, a pocket rule and an adze; to this list might be added their large pocket knives, which every man and boy on the frontier carries habitually. For camp utensils each boy had a tin cup and that was all, except a single light skillet, which they were to carry alternately, as they were to do with the tools. Each boy carried a blanket tightly rolled up, and each had, at the start, eight pounds of corn meal and four pounds of bacon, with a small sack of salt each, which could be carried in any pocket. This was all. They had no arms and no ammunition.

Their destination and the purpose of their journey were wholly unknown to anybody in the[61] camp, except General Jackson and Tandy Walker. The boys themselves were as ignorant as anybody on this subject. Sam had enlisted them in the service, merely telling them that he was going on an expedition which might prove difficult, dangerous and full of hardship. He told them that he could not make them legal soldiers before leaving, but that implicit obedience was absolutely necessary, and that he wanted no boy to go with him who was not willing to trust his judgment absolutely and obey orders as a soldier does, without knowing why they are given or what they are meant to accomplish. To put this matter on a proper basis, he drew up an enlistment paper as follows:—

"We, whose names are signed below, volunteer to go with Samuel Hardwicke and under his command, on the expedition which he is about beginning. We have been duly warned of the dangers and hardships to be encountered; we freely undertake to endure the hardships without shrinking, and to face the dangers as soldiers should; and, understanding the necessity of discipline and obedience, we promise, each of us upon[62] his honor, fully to recognize the authority of Samuel Hardwicke as our Captain, appointed by General Jackson; we promise upon honor, to obey his command, as implicity as if we were regularly enlisted soldiers, and he a properly commissioned officer."

(Signed.)

When this paper was signed by all the boys, including black Joe, who insisted upon attaching his[63] name to it in the printing letters which "little Miss Judie" had taught him, it was placed in General Jackson's hands for keeping, and Sam marched his party away, amid the wondering curiosity of the few troops who were in camp. They knew that this party went out under orders of some sort from head quarters, but they could not imagine whither it was going or why. Many of them had tried to get information from the boys themselves, but as the boys knew absolutely nothing about it, they could answer no questions, except with the rather unsatisfactory formula "I dunno."

he boys marched steadily until sunset, when Sam called a halt and selected a camping place for the night. He ordered a fire built and himself superintended the preparation of supper, limiting the amount of food cooked for each member of the party, a regulation which he enforced strictly throughout the march, lest any of the boys should imprudently eat their rations too fast, which, as their route lay through woods and swamps in a part of the country scarcely at all settled, would bring disaster upon the expedition of course. Sam had calculated the march to last about ten days, but he hoped to accomplish it within a briefer time. The supplies they had would last ten days, and Sam hoped to add to them by killing game from time to time, for al[65]though the party were unarmed, Sam knew ways of getting game without gunpowder, and meant to put some of them in practice.

Toward evening of the first day out, he had stopped in a canebrake and cut three well seasoned canes, selecting straight, tall ones, about an inch in diameter, and taking care that they tapered as little and as regularly as possible. Cutting them off at both ends and leaving them about fifteen feet in length, he next cut three or four small canes, very long and green ones, without flaw.

That night, as soon as supper was over he brought his canes to the fire and laid them down, preparatory to beginning work upon them.

"What are you a goin' to do with them canes, Sam?" asked Billy Bowlegs.

"What do you think, Billy?"

"Dog-gone ef I know," replied Billy.

"Suppose you quit saying 'dog-gone' Billy," said Sam. "It isn't a very good thing to say, and you've said it thirty-two times this afternoon."

"Have I? well, what's the odds if I have?"

"Well, it's a bad habit, and if you'll quit it, I'll give you one of those canes when I get them ready."[66]

"What 'er you goin' to make 'em into?"

"Guns," said Sam, working away as hard as he could with his jack-knife.

"Guns! what sort o' guns? Powder'd burst 'em in a minute, and besides we aint got no powder."

"No, but I'm going to make guns out of these canes, and I'm going to kill something with them too."

"What sort o' guns?"

"Blow guns."

"What's a blow gun, Mas. Sam?" asked Joe, becoming interested, as all the boy were now.

Sam was too busy to answer at the moment and so Tom, who had seen Sam's blow guns at home, answered for him.

"He's going to burn out the joints and then make arrows with iron points and some rabbit fur around the light ends. The fur fills up the hole in the cane, and when he blows in the end it sends the arrow off like a bullet. But Sam!" he cried, suddenly thinking of something.

"What is it?" asked the elder brother without looking up.[67]

"What are you going to burn them out with?"

"With that little rod," answered Sam, tossing a bit of iron about six inches long towards his brother, "I brought it with me on purpose."

"Well, but it won't reach; you've got to reach all the joints you know, and the rod must be as long as the cane."

"Oh no, not by any means."

"Yes it must, of course it must," exclaimed all the boys in a breath. "It's just like burning out a pipe stem with a wire."

"No it is not," replied Sam, smiling, "but suppose it is. I can burn out a pipe stem with a wire half as long as the stem."

"How?" asked two or three boys at once.

"By burning first from one end and then from the other."

"Yes, that's so," answered Sid Russell slowly, drawling his words out as if he had to drag them up through his long legs, "but that don't tell how you're goin' to bore out a big cane, fifteen feet long with a little iron rod not more 'n six or eight inches long."

"Well, if you will be patient a moment, I'll show[68] you," answered Sam, picking up the bit of iron. Trimming off the end of one of his small green canes, Sam measured it by the iron rod and trimmed again. He continued this process until he had the end of the cane a trifle larger than the iron was. Then taking an iron tube or band out of his pocket, he drove the iron rod firmly into it for the distance of about half an inch, leaving the other end of the tube open. Into this he forced the end of the small green cane and having made it firm he had a rod about ten feet long.

"There," he said, "I have a rod long enough to reach a good deal more than half way through either one of my big canes. It isn't iron except at the end, and it doesn't need to be," and with that he thrust the end of the bit of iron into the fire to heat.

"Now, Tom," he said, "you must burn the canes out while I do something else."

I wonder if there is any boy who needs a fuller explanation than the one which Sam has already given, of what was going forward. There may be boys enough, for aught I know, who never went fishing in their lives, and so do not know what[69] canes, or reeds, or cane-poles, as they are variously called, are like. I must explain, therefore, that the canes which Sam proposed to burn out, were precisely such as those that are commonly used as fishing rods. These canes grow all over the South, in the swamps. They are, in fact, a kind of gigantic grass, although the people who are most familiar with them do not dream of the fact. The botanists call them a grass, at any rate, and the botanists know. Each cane is a long, straight rod, tapering very gently, with "joints," as they are called, about eight or ten inches apart. These joints are simply places where the cane, outside, is a little larger than it is between joints, while inside each joint consists of a hard woody partition, across the hollow tube, which is otherwise continuous. Sam's plan was simply to burn these partitions away with a hot iron, which would convert the cane into a long, slender, wooden tube, very hard, very light, and straight as an arrow.

Tom went to work at once to burn out the joints, a work which occupied a good deal of time, as the iron had to be re-heated a great many times. He worked very steadily, however with the assist[70]ance of two or three of the boys, and managed during that first evening to get two of the blow guns burned out.

Meantime Sam made an arrow, very small and only about ten inches long, out of some dry cedar.

"Now," he said, "I want those of you who are not busy burning out the canes, to go to work making arrows just like that, while I do something else."

The boys went to work with a will, while Sam, going into the nearest thicket, cut a green stick about three quarters of an inch in diameter. Returning to the fire, he split one end of this stick for a little way, converting it into a sort of rude pincer. He then unrolled his blanket, and revealed to the astonished gaze of his companions several pounds of horse shoe nails.

"What on earth are you goin' to do with them horse shoe nails?" asked Hilly Bowlegs, looking up from the cedar arrow on which he was working.

"I'm going to make arrow heads out of them," answered Sam, thrusting several of them into the bed of coals.[71]

With the side of an axe for an anvil, and the hatchet for a hammer, Sam was soon very busy forging his wrought nails into sharp arrow points, holding the hot iron in his wooden pincers. Among the things that Sam had thought it worth while to learn something about, was blacksmithing, and he was really expert in the simpler arts of the smith. He could shoe a horse, "point" a plow, or weld iron or steel, very well indeed.

He had learned this as he had learned a good many other things, merely because he thought that every young man should know how to do tolerably well whatever he might sometime need to do, and in a new country where shops are scarce and workmen are not always to be found, there is no mechanical art which it is not sometimes very convenient to know something about.

Sam wrought now so expertly that within less than an hour he had made six arrow points. These he fitted to six of the arrows, and then he suspended work for the evening, and marked progress on his map; that is to say, he pricked on his map with a pin the course followed during the afternoon, estimating the distance travelled as accurately as he could.

he next day the march was resumed, and continued with some haltings for rest until about three o'clock, when Sam chose a camp for the night, saying that they had already made a better march than he had planned for that day, and that there was no occasion to break themselves down by going further.

The work was at once resumed upon guns and arrows, Sam beginning by finishing the arrows already made. He cut strips from a hare's skin which Tommy had brought with him at Sam's request, making each strip about four or five inches long, and just wide enough to meet around the end of an arrow. Binding these strips firmly, the arrows were complete. Each was a slender, light stick of cedar, shod at one end with a slen[73]der iron point, and bound around at the other, for a distance of several inches, with the fur of the hare. Pushing one of these into the mouth end of his blow gun, Sam showed his companions that the fur completely filled the tube, so that when he should blow in the end the arrow would be driven through and out with considerable force.

Pointing the gun toward a tree a little way off, Sam blew, and in a moment the arrow was seen sticking in the tree, its head being almost wholly buried in the solid wood.

The boys all wanted to try the new guns, of course, and Sam permitted them to do so, greatly to their delight, as long as the daylight lasted. Then the manufacture of new arrows began, the boys working earnestly now, because they were interested.

After awhile Sam took out his map and began pricking the course upon it.

"I say, Sam," said Bob Sharp, "how do you do that?"

"How do I do what? Prick the map?"

"No, I mean how do you know where we are and which way we go?"[74]

"That's just what I want to know," said Sid Russell.

"And me, too," chimed in Billy Bunker and Jake Elliott.

"Well, come here, all of you," replied Sam, "and I'll show you. We started there, at camp Jackson,—you see, don't you, where the Coosa and the Tallapoosa rivers come together and we are going down there," pointing to a spot on the map, "to the sea, or rather to the Bay near Pensacola."

"Are we! Good! I never saw the sea," said Sid Russell, speaking faster than any of the boys had ever heard him speak before.

"Yes, that is the place we're going to, and presently I'll tell you what we're going for; but one thing at a time. You see the course is a little west of south, nearly but not quite southwest. The distance, in an air line is about a hundred and twenty-five miles: that is to say Pensacola is about a hundred and ten miles further south than camp Jackson, and about fifty miles further west."

"That would be a hundred and sixty miles then," said Billy Bowlegs.

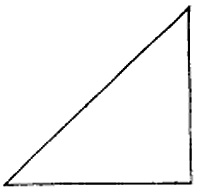

"Yes," replied Sam, "it would if we went due[75] south and then due west, taking the base and perpendicular of a right angled triangle, instead of its hypothenuse."

"Whew, what's all them words I wonder," exclaimed Billy.

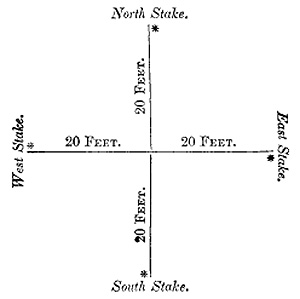

"Well, I'll try to show you what I mean," said Sam, taking a stick and drawing in the sand a figure like this:

"There," said Sam, "that's a right angled triangle, but you may call it a thingimajig if you like; it doesn't matter about the name. Suppose we start at the top to go to the left hand lower corner; don't you see that it would be further to go straight down to the right hand lower corner and then across to the left hand lower corner, than to go straight from the top to the left hand lower corner."

"Certainly," replied Billy, "it's just like going cat a cornered across a field."[76]

"Well," said Sam, pointing with his finger, "if I were to draw a triangle here on the map beginning at camp Jackson and running due south to the line of Pensacola, and then due west to Pensacola itself, with a third line running 'cat a cornered' as you say, from camp Jackson straight to Pensacola, the line due south would be about a hundred and ten miles long and the one due west about fifty miles long, while the 'cat a cornered' line would be about a hundred and twenty five miles long."

"How do you find out that last,—the cat a cornered line's length?" asked Tom.

"I can't explain that to you," said Sam, "because you haven't studied geometry."

"Oh well, tell us anyhow, if we don't understand it," said Sid Russell, who sat with his mouth open.

"Sid wants to find out how to tell how far it is from his head to his heels, without having to make the trip when he's tired," said Bob Sharp, who was always poking fun at Sid's long legs.

"Well," said Sam smiling, "I know the length of that line because I know that the square[77] described on the hypothenuse of a right angled triangle is equal to the sum of the squares described on the other two sides."

"Whew! it fairly takes the breath out of a fellow to hear you rattle that off," replied Sid.

"Come," resumed Sam, "we aren't getting on with what we undertook. Now look and listen. Here is the line we would follow if we could go straight from Camp Jackson to Pensacola. If we could follow it, I would only have to guess how many miles we march each day, and mark it down on the map. But we can't go straight, because of swamps and creeks and canebrakes, so I must keep looking at my compass to find out what direction we do go; then I mark on the map the route we have followed each day, and the distance, and each night's camp gives me a new starting point."

"Yes, but Sam," said Tom, suddenly thinking of something.

"Well, what is it, Tom?"

"Suppose you guess wrong as to the distance travelled each day?"

"Well, suppose I do; I can't miss it very far."[78]

"No, but it gives you a wrong starting-point for the next day, and two or three mistakes would throw you clear out."

"Yes, but I make corrections constantly. You see, I have changed the place of last night's camp a little on the map."

"How do you make corrections?"

"By the creeks and rivers. Here, for instance, is a creek that we ought to cross about ten miles ahead. If we come to it short of that, or if it proves to be further off, I shall know that I have got to-night's camp placed wrong on the map. I shall then correct my estimate. When we come to the next creek I shall be able to make my guess still more certain, and by the time we get to Pensacola I shall have the whole march marked pretty nearly right on the map."

"I'd give a purty price for that there head o' your'n, Sam," said Sid Russell.

"It isn't for sale, Sid, and besides it will be a good deal cheaper to use the one you have, taking care to make it as good as anybody's. Now let me explain to all of you why we are going to Pensacola," and with that Sam entered[79] into the plans which we know all about already, and which need not be repeated here. When he had finished the boys plied him with questions, which he answered as well as he could. Jake Elliott said nothing for a time, but after a while he ventured to ask:—

"Don't they hang fellows they ketch in that sort o' business?"

"They hang spies," replied Sam, "but they can scarcely hold us to be spies, especially as we shall be in the territory of a friendly neutral nation, where there cannot properly be a British camp at all."

"Well, but mayn't they do it anyhow, just as they are a campin' there, anyhow?"

"Of course they may, but I do not think it likely. In the first place we mustn't let them suspect us, and in the second, we must make use of what law there is if we should be arrested."

"Well, but if it all failed, what then?" asked Jake.

"Oh, shut up Jake," cried Billy Bowlegs. "You're afeard, that's what's the matter with you."

"Well," replied Sam "that is simply a risk[80] that we have to run, like any other risk in war. I told you all in advance that the expedition was a hazardous one."

"Of course you did, an' what's more you didn't want Jake Elliott to come either," said Billy Bowlegs.

"Go into your hole, Jake, if you're scared," said Bob Sharp.

"Jake ain't scared, he's only bashful," drawled Sid Russell.

"I ain't afraid no more'n the rest of you," said Jake, "but you're all fools enough to run your heads into a noose."

"What do you mean by that?" asked Sam, looking up quickly from the map over which he had been poring.

"I mean just this," replied Jake, "that this here business 'll end in gettin' us into trouble that we wont git out of soon, an' I move we draw out'n it right now, afore its too late."

Sam was on his feet in an instant.

"Do you know what you're saying sir?" he cried. "Do you understand who is master here? Do you know that no motions are in order? Let [81]me tell you once for all that I will tolerate no further mutinous words from you. If I hear another word of the kind from you, or see a sign of misconduct on your part, I shall take measures for your punishment. Stop! I want no answer. I have warned you and that is enough."

Sam's sudden assertion of his authority, in terms so peremptory, took Jake completely by surprise. Sam was a good tempered fellow, and not at all disposed to "put on airs" as boys say, and hence he had been as easy and familiar with his companions as if they had been merely a lot of school boys out for a holiday; but when Jake Elliott suggested a revolt, Sam, the good natured companion, became Captain Sam, the stern commander, at once.

The other boys saw at once the necessity and propriety of the rebuke he had administered. They believed Jake Elliott to be a coward and a bully, and they were glad to see him properly and promptly checked in his effort to give trouble.

It was growing late and the boys presently threw themselves down on their beds of soft gray moss and were soon sound asleep.

ake Elliott was a coward all over, and clear through. He had always been a bully and pretended to the possession of unusual courage. He had tyrannized over small boys, threatened boys of his own size and sneered at boys whom he thought able to hold their own against him in a fight. He had had many fights in his time, but had always managed to get the best of his opponents, by the very simple process of choosing for the purpose, boys who were not as strong as he was. As a result of all this he had acquired a great reputation among his fellows, and most of the boys in his neighborhood were very careful not to provoke him; but he was a great coward through it all, and when he first came in collision with Sam[83] Hardwicke his cowardice showed itself too plainly to be mistaken. Now there is a curious thing about cowards of this sort. When they are once found out they lose the little appearance of courage that they have taken such pains to maintain, and become at once the most abject and shameless dastards imaginable. That was what happened to Jake Elliott. When Sam conquered him so effectually on the occasion of the boot stealing, he lost all the pride he had and all his meanness seemed to come to the surface. If he had had a spark of manliness in him, he would have recognized Sam's generosity in sparing him at that time, and would have behaved himself better afterward. As it was he simply cherished his malice and resolved to do Sam all the injury he could in secret.

When Sam organized his expedition at Camp Jackson, Jake had two motives in joining it. In the first place things around the camp looked too much like genuine preparation for a hard fight with the enemy, and Jake thought that if he should enlist he would be forced to fight, which was precisely what he did not mean to do if he[84] could help it. By joining Sam's party, however, he would escape the necessity of enlisting, and he thought that the little band was going away from danger instead of going into it. He thought, too, that if any real danger should come, under Sam's leadership, he could run away from it, or sneak out in some way, and as he would not be a regularly enlisted soldier, no punishment could follow.

This was his first reason for joining. His second one was still more unworthy. He was bent upon doing Sam all the secret injury he could, and he thought that by going with him he would have opportunities to wreak his vengeance, which he would otherwise lose.

When he learned, as we have seen, whither Sam was leading his party, and on what errand, he was really frightened, and Sam's sharp rebuke made him still bitterer in his feelings toward his young commander. A coward with a grudge which he is afraid to avenge openly, is a very dangerous foe. He will do anything against his adversary which he thinks he can do safely, by sneaking, and when Jake Elliott threw himself[85] down on his pile of moss he did not mean to go to sleep. He meant to revenge himself on Sam before morning, and at the same time to make it impossible for the expedition to go on. If he could force Sam to return to Camp Jackson, he said to himself, he would humiliate that young man beyond endurance, and at the same time get himself out of the danger into which Sam was leading him. Everybody would laugh at Sam, and call him a coward, and suspect him of failing in his expedition purposely, all of which would please Jake Elliott mightily.

How to accomplish all this was a problem which Jake thought he had solved by a sudden inspiration. He had formed his plan at the very moment of receiving Sam's rebuke, and he waited now only for a chance to execute it.