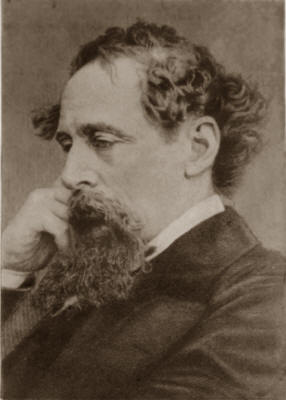

Title: Life of Charles Dickens

Author: Sir Frank T. Marzials

Release date: October 1, 2005 [eBook #16787]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Jason Isbell, Linda Cantoni, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Jason Isbell, Linda Cantoni,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(https://www.pgdp.net/)

EDITED BY

ERIC S. ROBERTSON, M.A.,

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY IN THE

UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE.

LIFE OF DICKENS.

LONDON

WALTER SCOTT

24 WARWICK LANE, PATERNOSTER ROW

1887

That I should have to acknowledge a fairly heavy debt to Forster's "Life of Charles Dickens," and "The Letters of Charles Dickens," edited by his sister-in-law and his eldest daughter, is almost a matter of course; for these are books from which every present and future biographer of Dickens must perforce borrow in a more or less degree. My work, too, has been much lightened by Mr. Kitton's excellent "Dickensiana."

The lottery of education; Charles Dickens born February 7, 1812; his pathetic feeling towards his own childhood; happy days at Chatham; family troubles; similarity between little Charles and David Copperfield; John Dickens taken to the Marshalsea; his character; Charles employed in blacking business; over-sensitive in after years about this episode in his career; isolation; is brought back into family and prison circle; family in comparative comfort at the Marshalsea; father released; Charles leaves the blacking business; his mother; he is sent to Wellington House Academy in 1824; character of that place of learning; Dickens masters its humours thoroughly. 11

Dickens becomes a solicitor's clerk in 1827; then a reporter; his experiences in that capacity; first story published in The Old Monthly Magazine for January, 1834; writes more "Sketches"; power of minute observation thus early shown; masters the writer's art; is paid for his contributions to the Chronicle; marries Miss Hogarth on April 2, 1836; appearance at that date; power of physical endurance; admirable influence of his peculiar education; and its drawbacks 27

Origin of "Pickwick"; Seymour's part therein; first number published on April 1, 1836; early numbers not a success; suddenly the book becomes the rage; English literature just then in want of its novelist; Dickens' kingship acknowledged; causes of the book's popularity; its admirable humour, and other excellent qualities; Sam Weller; Mr. Pickwick himself; book read by everybody 40

[Pg 8]Dickens works "double tides" from 1836 to 1839; appointed editor of Bentley's Miscellany at beginning of 1837, and commences "Oliver Twist"; Quarterly Review predicts his speedy downfall; pecuniary position at this time; moves from Furnival's Inn to Doughty Street; death of his sister-in-law Mary Hogarth; his friendships; absence of all jealousy in his character; habits of work; riding and pedestrianizing; walking in London streets necessary to the exercise of his art 49

"Oliver Twist"; analysis of the book; doubtful probability of Oliver's character; "Nicholas Nickleby"; its wealth of character; Master Humphrey's Clock projected and begun in April, 1840; the public disappointed in its expectations of a novel; "Old Curiosity Shop" commenced, and miscellaneous portion of Master Humphrey's Clock dropped; Dickens' fondness for taking a child as his hero or heroine; Little Nell; tears shed over her sorrows; general admiration for the pathos of her story; is such admiration altogether deserved? Paul Dombey more natural; Little Nell's death too declamatory as a piece of writing; Dickens nevertheless a master of pathos; "Barnaby Rudge"; a historical novel dealing with times of the Gordon riots 57

Dickens starts for United States in January, 1842; had been splendidly received a little before at Edinburgh; why he went to the United States; is enthusiastically welcomed; at first he is enchanted; then expresses the greatest disappointment; explanation of the change; what the Americans thought of him; "American Notes"; his views modified on his second visit to America in 1867-8; takes to fierce private theatricals for rest; delight of the children on his return to England; an admirable father 71

Dickens again at work and play; publication of "Martin Chuzzlewit" begun in January, 1843; plot not Dickens' strong point; this not of any vital consequence; a novel not really remembered by its story; Dickens' books often have a higher unity than that of plot; selfishness the central idea of "Martin Chuzzlewit"; a great book, and yet not at the time successful; Dickens foresees money embarrassments;[Pg 9] publishes the admirable "Christmas Carol" at Christmas, 1843; and determines to go for a space to Italy 84

Journey through France; Genoa; the Italy of 1844; Dickens charmed with its untidy picturesqueness; he is idle for a few weeks; his palace at Genoa; he sets to work upon "The Chimes"; gets passionately interested in the little book; travels through Italy to read it to his friends in London; reads it on December 2, 1844; is soon back again in Italy; returns to London in the summer of 1845; on January 21, 1846, starts The Daily News; holds the post of editor three weeks; "Pictures from Italy" first published in Daily News 93

Dickens as an amateur actor and stage-manager; he goes to Lausanne in May, 1846, and begins "Dombey"; has great difficulty in getting on without streets; the "Battle of Life" written; "Dombey"; its pathos; pride the subject of the book; reality of the characters; Dickens' treatment of partial insanity; M. Taine's false criticism thereon; Dickens in Paris in the winter of 1846-7; private theatricals again; the "Haunted Man"; "David Copperfield" begun in May, 1849; it marks the culminating point in Dickens' career as a writer; Household Words started on March 30, 1850; character of that periodical and its successor, All the Year Round; domestic sorrows cloud the opening of the year 1851; Dickens moves in same year from Devonshire Terrace to Tavistock House, and begins "Bleak House"; story of the novel; its Chancery episodes; Dickens is overworked and ill, and finds pleasant quarters at Boulogne 102

Dickens gives his first public (not paid) readings in December, 1853; was it infra dig. that he should read for money? he begins his paid readings in April, 1858; reasons for their success; care bestowed on them by the reader; their dramatic character; Carlyle's opinion of them; how the tones of Dickens' voice linger in the memory of one who heard him 121

[Pg 10] "Hard Times" commenced in Household Words for April 1, 1854; it is an attack on the "hard fact" school of philosophers; what Macaulay and Mr. Ruskin thought of it; the Russian war of 1854-5, and the cry for "Administrative Reform"; Dickens in the thick of the movement; "Little Dorrit" and the "Circumlocution Office"; character of Mr. Dorrit admirably drawn; Dickens is in Paris from December, 1855, to May, 1856; he buys Gad's Hill Place; it becomes his hobby; unfortunate relations with his wife; and separation in May 1858; lying rumours; how these stung Dickens through his honourable pride in the love which the public bore him; he publishes an indignant protest in Household Words; and writes an unjustifiable letter 126

"The Tale of Two Cities," a story of the great French Revolution; Phiz's connection with Dickens' works comes to an end; his art and that of Cruikshank; both too essentially caricaturists of an old school to be permanently the illustrators of Dickens; other illustrators; "Great Expectations"; its story and characters; "Our Mutual Friend" begun in May, 1864; a complicated narrative; Dickens' extraordinary sympathy for Eugene Wrayburn; generally his sympathies are so entirely right; which explains why his books are not vulgar; he himself a man of great real refinement 139

Dickens' health begins to fail; he is much shaken by an accident in June, 1865; but bates no jot of his high courage, and works on at his readings; sails for America on a reading tour in November, 1867; is wretchedly ill, and yet continues to read day after day; comes back to England, and reads on; health failing more and more; reading has to be abandoned for a time; begins to write his last and unfinished book, "Edwin Drood"; except health all seems well with him; on June 8, 1870, he works at his book nearly all day; at dinner time is struck down; dies on the following day, June the 9th; is buried in Westminster Abbey among his peers; nor will his fame suffer eclipse 149

Education is a kind of lottery in which there are good and evil chances, and some men draw blanks and other men draw prizes. And in saying this I do not use the word education in any restricted sense, as applying exclusively to the course of study in school or college; nor certainly, when I speak of prizes, am I thinking of scholarships, exhibitions, fellowships. By education I mean the whole set of circumstances which go to mould a man's character during the apprentice years of his life; and I call that a prize when those circumstances have been such as to develop the man's powers to the utmost, and to fit him to do best that of which he is best capable. Looked at in this way, Charles Dickens' education, however untoward and unpromising it may often have seemed while in the process, must really be pronounced a prize of value quite inestimable.

His father, John Dickens, held a clerkship in the Navy Pay Office, and was employed in the Portsmouth Dockyard when little Charles first came into the world, at [Pg 12]Landport, in Portsea, on February 7, 1812. Wealth can never have been one of the familiar friends of the household, nor plenty have always sat at its board. Charles had one elder sister, and six other brothers and sisters were afterwards added to the family; and with eight children, and successive removals from Portsmouth to London, and London to Chatham, and no more than the pay of a Government clerk[1]—pay which not long afterwards dwindled to a pension,—even a better domestic financier than the elder Dickens might have found some difficulty in facing his liabilities. It was unquestionably into a tottering house that the child was born, and among its ruins that he was nurtured.

But through all these early years I can do nothing better than take him for my guide, and walk as it were in his companionship. Perhaps no novelist ever had a keener feeling of the pathos of childhood than Dickens, or understood more fully how real and overwhelming are its sorrows. No one, too, has entered more sympathetically into its ways. And of the child and boy that he himself had once been, he was wont to think very tenderly and very often. Again and again in his writings he reverts to the scenes and incidents and emotions of his earlier days. Sometimes he goes back to his young life directly, speaking as of himself. More often he goes back to it indirectly, placing imaginary children and boys in the position he had once occupied. Thus it is almost possible, by judiciously [Pg 13]selecting from his works, and using such keys as we possess, to construct as it were a kind of autobiography. Nor, if we make due allowance for the great writer's tendency to idealize the past, and intensify its humorous and pathetic aspects, need we at all fear that the self-written story of his life should convey a false impression.

He was but two years old when his father left Portsea for London, and but four when a second migration took the family to Chatham. Here we catch our first glimpse of him, in his own word-painting, as a "very queer small boy," a small boy who was sickly and delicate, and could take but little part in the rougher sports of his school companions, but read much, as sickly boys will—read the novels of the older novelists in a "blessed little room," a kind of palace of enchantment, where "'Roderick Random,' 'Peregrine Pickle,' 'Humphrey Clinker,' 'Tom Jones,' 'The Vicar of Wakefield,' 'Don Quixote, 'Gil Blas,' and 'Robinson Crusoe,' came out, a glorious host, to keep him company." And the queer small boy had read Shakespeare's "Henry IV.," too, and knew all about Falstaff's robbery of the travellers at Gad's Hill, on the rising ground between Rochester and Gravesend, and all about mad Prince Henry's pranks; and, what was more, he had determined that when he came to be a man, and had made his way in the world, he should own the house called Gad's Hill Place, with the old associations of its site, and its pleasant outlook over Rochester and over the low-lying levels by the Thames. Was that a child's dream? The man's tenacity and steadfast strength of purpose turned it into fact. The house became the home of his later life. It was there that he died.

[Pg 14]But death was a long way forward in those old Chatham days; nor, as the time slipped by, and his father's pecuniary embarrassments began to thicken, and make the forward ways of life more dark and difficult, could the purchase of Gad's Hill Place have seemed much less remote. There is one of Dickens' works which was his own special favourite, the most cherished, as he tells us, among the offspring of his brain. That work is "David Copperfield." Nor can there be much difficulty in discovering why it occupied such an exceptional position in "his heart of hearts;" for in its pages he had enshrined the deepest memories of his own childhood and youth. Like David Copperfield, he had known what it was to be a poor, neglected lad, set to rough, uncongenial work, with no more than a mechanic's surroundings and outlook, and having to fend for himself in the miry ways of the great city. Like David Copperfield, he had formed a very early acquaintance with debts and duns, and been initiated into the mysteries and sad expedients of shabby poverty. Like David Copperfield, he had been made free of the interior of a debtor's prison. Poor lad, he was not much more than ten or eleven years old when he left Chatham, with all the charms that were ever after to live so brightly in his recollection,—the gay military pageantry, the swarming dockyard, the shifting sailor life, the delightful walks in the surrounding country, the enchanted room, tenanted by the first fairy day-dreams of his genius, the day-school, where the master had already formed a good opinion of his parts, giving him Goldsmith's "Bee" as a keepsake. This pleasant land he left for a dingy house in a dingy London suburb, [Pg 15]with squalor for companionship, no teaching but the teaching of the streets, and all around and above him the depressing hideous atmosphere of debt. With what inimitable humour and pathos has he told the story of these darkest days! Substitute John Dickens for Mr. Micawber, and Mrs. Dickens for Mrs. Micawber, and make David Copperfield a son of Mr. Micawber, a kind of elder Wilkins, and let little Charles Dickens be that son—and then you will have a record, true in every essential respect, of the child's life at this period. "Poor Mrs. Micawber! she said she had tried to exert herself; and so, I have no doubt, she had. The centre of the street door was perfectly covered with a great brass-plate, on which was engraved 'Mrs. Micawber's Boarding Establishment for Young Ladies;' but I never found that any young lady had ever been to school there; or that any young lady ever came, or proposed to come; or that the least preparation was ever made to receive any young lady. The only visitors I ever saw or heard of were creditors. They used to come at all hours, and some of them were quite ferocious." Even such a plate, bearing the inscription, Mrs. Dickens's Establishment, ornamented the door of a house in Gower Street North, where the family had hoped, by some desperate effort, to retrieve its ruined fortunes. Even so did the pupils refuse the educational advantages offered to them, though little Charles went from door to door in the neighbourhood, carrying hither and thither the most alluring circulars. Even thus was the place besieged by assiduous and angry duns. And when, in the ordinary course of such sad stories, Mr. Dickens is arrested for debt, and carried [Pg 16]off to the Marshalsea prison,[2] he moralizes over the event in precisely the same strain as Mr. Micawber, using, indeed, the very same words, and calls on his son, with many tears, "to take warning by the Marshalsea, and to observe that if a man had twenty pounds a year, and spent nineteen pounds nineteen shillings and sixpence, he would be happy; but that a shilling spent the other way would make him wretched."

The son was taking note of other things besides these moral apothegms, and reproduced, in after days, with a quite marvellous detail and fidelity, all the incidents of his father's incarceration. Probably, too, he was beginning, as children will, almost unconsciously, to form some estimate of his father's character. And a very queer study in human nature that must have been, giving Dickens, when once he had mastered it, a most exceptional insight into the ways of impecuniosity. Charles Lamb, as we all remember, divided mankind into two races, the mighty race of the borrowers, and the mean race of the lenders; and expatiated, with a whimsical and charming eloquence, upon the greatness of one Bigod, who had been as a king among those who by process of loan obtain possession of other people's money. Shift the line of division a little, so that instead of separating borrowers and lenders, it separates those who pay their debts from those who do not pay them, and then Dickens the elder may succeed to something of Bigod's kingship. He was of the great race of debtors, [Pg 17] possessing especially that ideal quality of mind on which Lamb laid such stress. Imagination played the very mischief with him. He had evidently little grasp of fact, and moved in a kind of haze, through which all clear outlines would show blurred and unreal. Sometimes—most often, perhaps—that haze would be irradiated with sanguine visionary hopes and expectations. Sometimes it would be fitfully darkened with all the horrors of despair. But whether in gloom or gleam, the realities of his position would be lost. He never, certainly, contracted a debt which he did not mean honourably to pay. But either he had never possessed the faculty of forming a just estimate of future possibilities, or else, through the indulgence of what may be called a vague habit of thought, he had lost the power of seeing things as they are. Thus all his excellencies and good gifts were neutralized at this time, so far as his family were concerned, and went for practically nothing. He was, according to his son's testimony, full of industry, most conscientious in the discharge of any business, unwearying in loving patience and solicitude when those bound to him by blood or friendship were ill or in trouble, "as kind-hearted and generous a man as ever lived in the world." Yet as debts accumulated, and accommodation bills shed their baleful shadow on his life, and duns grew many and furious, he became altogether immersed in mean money troubles, and suffered the son who was to shed such lustre on his name to remain for a time without the means of learning, and to sink first into a little household drudge, and then into a mere warehouse boy.

So little Charles, aged from eleven to twelve, first [Pg 18]blacked boots, and minded the younger children, and ran messages, and effected the family purchases—which can have been no pleasant task in the then state of the family credit,—and made very close acquaintance with the inside of the pawnbrokers' shops, and with the purchasers of second-hand books, disposing, among other things, of the little store of books he loved so well; and then, when his father was imprisoned, ran more messages hither and thither, and shed many childish tears in his father's company—the father doubtless regarding the tears as a tribute to his eloquence, though, heaven knows, there were other things to cry over besides his sonorous periods. After which a connection, James Lamert by name, who had lived with the family before they moved from Camden Town to Gower Street, and was manager of a worm-eaten, rat-riddled blacking business, near old Hungerford Market, offered to employ the lad, on a salary of some six shillings a week, or thereabouts. The duties which commanded these high emoluments consisted of the tying up and labelling of blacking pots. At first Charles, in consideration probably of his relationship to the manager, was allowed to do his tying, clipping, and pasting in the counting-house. But soon this arrangement fell through, as it naturally would, and he descended to the companionship of the other lads, similarly employed, in the warehouse below. They were not bad boys, and one of them, who bore the name of Bob Fagin, was very kind to the poor little better-nurtured outcast, once, in a sudden attack of illness, applying hot blacking-bottles to his side with much tenderness. But, of course, they were rough and quite uncultured, and the sensitive, [Pg 19]bookish, imaginative child felt that there was something uncongenial and degrading in being compelled to associate with them. Nor, though he had already sufficient strength of character to learn to do his work well, did he ever regard the work itself as anything but unsuitable, and almost discreditable. Indeed it may be doubted whether the iron of that time did not unduly rankle and fester as it entered into his soul, and whether the scar caused by the wound was altogether quite honourable. He seems to have felt, in connection with his early employment in a warehouse, a sense of shame such as would be more fittingly associated with the commission of an unworthy act. That he should not have habitually referred to the subject in after life, may readily be understood. But why he should have kept unbroken silence about it for long years, even with his wife, even with so very close a friend as Forster, is less clear. And in the terms used, when the revelation was finally made to Forster, there has always, I confess, appeared to me to be a tone of exaggeration. "My whole nature," he says, "was so penetrated with grief and humiliation, ... that even now, famous and caressed and happy, I often forget in my dreams that I have a dear wife and children; even that I am a man, and wander desolately back to that time of my life." And again: "From that hour until this, at which I write, no word of that part of my childhood, which I have now gladly brought to a close, has passed my lips to any human being.... I have never, until I now impart it to this paper, in any burst of confidence with any one, my own wife not excepted, raised the curtain I then dropped, thank God." Great part, perhaps the greatest part, of [Pg 20]Dickens' success as a writer, came from the sympathy and power with which he showed how the lower walks of life no less than the higher are often fringed with beauty. I have never been able to entirely divest myself of a slight feeling of the incongruous in reading what he wrote about the warehouse episode in his career.

At first, when he began his daily toil at the blacking business, some poor dregs of family life were left to the child. His father was at the Marshalsea. But his mother and brothers and sisters were, to use his own words, "still encamped, with a young servant girl from Chatham workhouse, in the two parlours in the emptied house in Gower Street North." And there he lived with them, in much "hugger-mugger," merely taking his humble midday meal in nomadic fashion, on his own account. Soon, however, his position became even more forlorn. The paternal creditors proved insatiable. The gipsy home in Gower Street had to be broken up. Mrs. Dickens and the children went to live at the Marshalsea. Little Charles was placed under the roof—it cannot be called under the care—of a "reduced old lady," dwelling in Camden Town, who must have been a clever and prophetic old lady if she anticipated that her diminutive lodger would one day give her a kind of indirect unenviable immortality by making her figure, under the name of "Mrs. Pipchin," in "Dombey and Son." Here the boy seems to have been left almost entirely to his own devices. He spent his Sundays in the prison, and, to the best of his recollection, his lodgings at "Mrs. Pipchin's" were paid for. Otherwise, he "found himself," in childish fashion, out of the six or seven weekly shillings, breakfasting on [Pg 21]two pennyworth of bread and milk, and supping on a penny loaf and a bit of cheese, and dining hither and thither, as his boy's appetite dictated—now, sensibly enough, on à la mode beef or a saveloy; then, less sensibly, on pudding; and anon not dining at all, the wherewithal having been expended on some morning treat of cheap stale pastry. But are not all these things, the lad's shifts and expedients, his sorrows and despair, his visits to the public-house, where the kindly publican's wife stoops down to kiss the pathetic little face—are they not all written in "David Copperfield"? And if so be that I have a reader unacquainted with that peerless book, can I do better than recommend him, or her, to study therein the story of Dickens' life at this particular time?

At last the child's solitude and sorrows seem to have grown unbearable. His fortitude broke down. One Sunday night he appealed to his father, with many tears, on the subject, not of his employment, which he seems to have accepted at the time manfully, but of his forlornness and isolation. The father's kind, thoughtless heart was touched. A back attic was found for Charles near the Marshalsea, at Lant Street, in the Borough—where Bob Sawyer, it will be remembered, afterwards invited Mr. Pickwick to that disastrous party. The boy moved into his new quarters with the same feeling of elation as if he had been entering a palace.

The change naturally brought him more fully into the prison circle. He used to breakfast there every morning, before going to the warehouse, and would spend the larger portion of his spare time among the inmates. Nor do Mr. Dickens and his family, and Charles, who is to us the [Pg 22]family's most important member, appear to have been relatively at all uncomfortable while under the shadow of the Marshalsea. There is in "David Copperfield" a passage of inimitable humour, where Mr. Micawber, enlarging on the pleasures of imprisonment for debt, apostrophizes the King's Bench Prison as being the place "where, for the first time in many revolving years, the overwhelming pressure of pecuniary liabilities was not proclaimed from day to day, by importunate voices declining to vacate the passage; where there was no knocker on the door for any creditor to appeal to; where personal service of process was not required, and detainers were lodged merely at the gate." There is a similar passage in "Little Dorrit," where the tipsy medical practitioner of the Marshalsea comforts Mr. Dorrit in his affliction by saying: "We are quiet here; we don't get badgered here; there's no knocker here, sir, to be hammered at by creditors, and bring a man's heart into his mouth. Nobody comes here to ask if a man's at home, and to say he'll stand on the door-mat till he is. Nobody writes threatening letters about money to this place. It's freedom, sir, it's freedom!" One smiles as one reads; and it adds a pathos, I think, to the smile, to find that these are records of actual experience. The Marshalsea prison was to Mr. Dickens a haven of peace, and to his household a place of plenty. Not only could he pursue his career there untroubled by fears of arrest, but he exercised among the other "gentlemen gaol-birds" a supremacy, a kind of kingship, such as that to which Charles Lamb referred. They recognized in him the superior spirit, ready of pen, and affluent of speech, and with a certain grandeur in his conviviality. [Pg 23]He it was who drew up their memorial to George of England on an occasion no less important than the royal birthday, when they, the monarch's "unfortunate subjects,"—so they were described in the memorial—besought the king's "gracious majesty," of his "well-known munificence," to grant them a something towards the drinking of the royal health. (Ah, with what keen eyes and penetrative genius did little Charles, from his corner, watch the strange sad stream of humanity that trickled through the room, and may be said to have smeared its approval of that petition!) And while Mr. Dickens was enjoying his prison honours, he was also enjoying his Admiralty pension,[3] which was not forfeited by his imprisonment; and his wife and children were consequently enjoying a larger measure of the necessaries of life than had been theirs for many a month. So all went on merrily enough at the Marshalsea.

But even under the old law, imprisonment for debt did not always last for ever. A legacy, and the Insolvent Debtors Act, enabled Mr. Dickens to march out of durance, in some sort with the honours of war, after a few months' incarceration—this would be early in 1824;—and he went with his family, including Charles, to lodge with the "Mrs. Pipchin" already mentioned. Charles meanwhile still toiled on in the blacking warehouse, now removed to Chandos Street, Covent Garden; and had reached such skill in the tying, pasting, and labelling of the bottles, that small crowds used to collect at the window for the purpose of watching his deft fingers. There was pride in [Pg 24]this, no doubt, but also humiliation; and release was at hand. His father and Lamert quarrelled about something—about what, Dickens seems never to have known—and he was sent home. Mrs. Dickens acted the part of the peacemaker on the next day, probably feeling that amid the shadowy expectations on which she and her husband had subsisted for so long, even six or seven shillings a week was something tangible, and not to be despised. Yet in spite of this, he did not return to the business. His father decided that he should go to school. "I do not write resentfully or angrily," said Dickens, in the confidential communication made long afterwards to Forster, and to which reference has already been made; "but I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back."

The mothers of great men is a subject that has been handled often, and eloquently. How many of those who have achieved distinction can trace their inherited gifts to a mother's character, and their acquired gifts to a mother's teaching and influence. Mrs. Dickens seems not to have been a mother of this stamp. She scarcely, I fear, possessed those admirable qualities of mind and heart which one can clearly recognize as having borne fruit in the greatness and goodness of her famous son. So far as I can discover, she exercised no influence upon him at all. Her name hardly appears in his biographies. He never, that I can recollect, mentions her in his correspondence; only refers to her on the rarest occasions. And perhaps, on the whole, this is not to be wondered at, if we accept the constant tradition that she had, [Pg 25]unknown to herself, sat to her son for the portrait of Mrs. Nickleby, and suggested to him the main traits in the character of that inconsequent and not very wise old lady. Mrs. Nickleby, I take it, was not the kind of person calculated to form the mind of a boy of genius. As well might one expect some very domestic bird to teach an eaglet how to fly.

The school to which our callow eaglet was sent (in the spring or early summer of 1824), belonged emphatically to the old school of schools. It bore the goodly name of Wellington House Academy, and was situated in Mornington Place, near the Hampstead Road. A certain Mr. Jones held chief rule there; and as more than fifty years have now elapsed since Dickens' connection with the establishment ceased, I trust there may be nothing libellous in giving further currency to his statement, or rather, perhaps, to his recorded impression,[4] that the head master's one qualification for his office was dexterity in the use of the cane;—especially as another "old boy" corroborates that impression, and declares Mr. Jones to have been "a most ignorant fellow, and a mere tyrant." Dickens, however, escaped with comparatively little beating, because he was a day-boy, and sound policy dictated that day-boys, who had facilities for carrying home their complaints, should be treated with some leniency. So he had to get his learning without tears, which was not at all considered the orthodox method in the good old days; and, indeed, I doubt if he finally took away from Wellington House Academy very much of the book knowledge that would tell in a modern com[Pg 26]petitive examination. For though in his own account of the school it is implied that he resumed his interrupted studies with Virgil, and was, before he left, head boy, and the possessor of many prizes, yet this is not corroborated by the evidence of his surviving fellow pupils; nor can we, of course, in the face of their direct counter evidence, treat statements made in a fictitious or half-fictitious narrative as if made in what professed to be a sober autobiography. Dickens, I repeat, seems to have acquired a very scant amount of classic lore while under the instruction of Mr. Jones, and not too much lore of any kind. But if he learned little, he observed much. He thoroughly mastered the humours of the place, just as he had mastered the humours of the Marshalsea. He had got to know all about the masters, and all about the boys, and all about the white mice—of which there were many in various stages of civilization. He acquired, in short, a fund of school knowledge that seemed inexhaustible, and on which he drew again and again, with the most excellent results, in "David Copperfield," in "Dombey," in such inimitable short papers as "Old Cheeseman." And while thus, half unconsciously perhaps, assimilating the very life of the school, he was himself a thorough schoolboy, bright, alert, intelligent; taking part in all fun and frolic; amply indemnifying himself for his enforced abstinence from childish games during the dreary warehouse days; good at recitations and mimic plays; and already possessed of a reputation among his peers as a writer of tales.

[1] £200 a year "without extras" from 1815 to 1820, and then £350. See "Childhood and Youth of Charles Dickens," by Robert Langton, a very valuable monograph.

[2] Mr. Langton appears to doubt whether John Dickens was not imprisoned in the King's Bench. But this seems scarcely a point on which Dickens himself can have been mistaken.

[3] According to Mr. Langton's dates, he would still be drawing his pay.

[4] See paper entitled "Our School."

Dickens cannot have been very long at Wellington House Academy, for before May, 1827, he had been at another school near Brunswick Square, and had also obtained, and quitted, some employment in the office of a solicitor in New Square, Lincoln's Inn Fields. It seems clear, therefore, that the whole of his school life might easily be computed in months; and in May, 1827, it will be remembered, he was still but a lad of fifteen. At that date he entered the office of a second solicitor, in Gray's Inn this time, on a salary of thirteen shillings and sixpence a week, afterwards increased to fifteen shillings. Here he remained till November, 1828, again picking up a good deal of information that cannot perhaps be regarded as strictly legal, but such as he was afterwards able to turn to admirable account. He would seem to have studied the profession exhaustively in all its branches, from the topmost Tulkinghorns and Perkers, to the lowest pettifoggers like Pell and Brass, and also to have given particular attention to the parasites of the law—the Guppys and Chucksters; and altogether to have stored his mind, as he had done at school, with a series of invaluable notes and observations. All very well, no doubt, [Pg 28]as we look at the matter now. But then it must often have seemed to the ambitious, energetic lad, that he was wasting his time. Was he to remain for ever a lawyer's clerk who has not the means to be an articled clerk, and who can never, therefore, aspire to become a full-blown solicitor? Was he to spend the future obscurely in the dingy purlieus of the law? His father, in whose career "something," as Mr. Micawber would have said, had at last "turned up," was now a reporter for the press. The son determined to be a reporter too.

He threw himself into this new career with characteristic energy. Of course a reporter is not made in a day. It takes many months of drudgery to obtain such skill in shorthand as shall enable the pen of the ready-writer to keep up with the winged words of speech, and make dots and lines that shall be readable. Dickens laboured hard to acquire the art. In the intervals of his work he made it a kind of holiday task to attend the Reading-room of the British Museum, and so remedy the defects in the literary part of his education. But the best powers of his mind were directed to "Gurney's system of shorthand." And in time he had his reward. He earned and justified the reputation of being one of the best reporters of his day.

I shall not quote the autobiographical passages in "David Copperfield" which bear on the difficulties of stenography. The book is in everybody's hands. But I cannot forego the pleasure of brightening my pages with Dickens' own description of his experiences as a reporter, a description contained in one of those charming felicitous speeches of his which are almost as unique in kind as his [Pg 29]novels. Speaking in May, 1865, as chairman of a public dinner on behalf of the Newspaper Press Fund, he said: "I have pursued the calling of a reporter under circumstances of which many of my brethren at home in England here, many of my modern successors, can form no adequate conception. I have often transcribed for the printer, from my shorthand notes, important public speeches, in which the strictest accuracy was required, and a mistake in which would have been, to a young man, severely compromising, writing on the palm of my hand, by the light of a dark lantern, in a post-chaise and four, galloping through a wild country, and through the dead of the night, at the then surprising rate of fifteen miles an hour. The very last time I was at Exeter, I strolled into the castle-yard there to identify, for the amusement of a friend, the spot on which I once took, as we used to call it, an election speech of my noble friend Lord Russell, in the midst of a lively fight maintained by all the vagabonds in that division of the county, and under such pelting rain, that I remember two good-natured colleagues, who chanced to be at leisure, held a pocket-handkerchief over my note-book, after the manner of a State canopy in an ecclesiastical procession. I have worn my knees by writing on them on the old back row of the old gallery in the old House of Commons; and I have worn my feet by standing to write in a preposterous pen in the old House of Lords, where we used to be huddled together like so many sheep, kept in waiting, say, until the woolsack might want re-stuffing. Returning home from excited political meetings in the country to the waiting press in London, I do verily believe I have been upset in almost every de[Pg 30]scription of vehicle known in this country. I have been, in my time, belated in miry by-roads, towards the small hours, forty or fifty miles from London, in a wheel-less carriage, with exhausted horses, and drunken postboys, and have got back in time for publication, to be received with never-forgotten compliments by the late Mr. Black, coming in the broadest of Scotch from the broadest of hearts I ever knew."

What shall I add to this? That the papers on which he was engaged as a reporter, were The True Sun, The Mirror of Parliament, and The Morning Chronicle; that long afterwards, little more than two years before his death, when addressing the journalists of New York, he gave public expression to his "grateful remembrance of a calling that was once his own," and declared, "to the wholesome training of severe newspaper work, when I was a very young man, I constantly refer my first success;" that his income as a reporter appears latterly to have been some five guineas a week, of course in addition to expenses and general breakages and damages; that there is independent testimony to his exceptional quickness in reporting and transcribing, and to his intelligence in condensing; that to an observer so keen and apt, the experiences of his business journeys in those more picturesque and eventful ante-railway days must have been invaluable; and, finally, that his connection with journalism lasted far into 1836, and so did not cease till some months after "Pickwick" had begun to add to the world's store of merriment and laughter.

But I have not really reached "Pickwick" yet, nor anything like it. That master-work was not also a first work. [Pg 31]With all Dickens' genius, he had to go through some apprenticeship in the writer's art before coming upon the public as the most popular novelist of his time. Let us go back for a little to the twilight before the full sunrise, nay, to the earliest streak upon the greyness of night, to his first original published composition. Dickens himself, and in his preface to "Pickwick" too, has told us somewhat about that first paper of his; how it was "dropped stealthily one evening at twilight, with fear and trembling, into a dark letter-box, in a dark office, up a dark court in Fleet Street;" how it was accepted, and "appeared in all the glory of print;" and how he was so filled with pleasure and pride on purchasing a copy of the magazine in which it was published, that he went into Westminster Hall to hide the tears of joy that would come into his eyes. The paper thus joyfully wept over was originally entitled "A Dinner at Poplar Walk," and now bears, among the "Sketches by Boz," the name of "Mr. Minns and his Cousin"; the periodical in which it was published was The Old Monthly Magazine, and the date of publication was January 1, 1834.

"A Dinner at Poplar Walk" may be pronounced a very fairly told tale. It is, no doubt, always easy to be wise after the event, in criticism particularly easy, and when once a writer has achieved success, there is but too little difficulty in showing that his earlier productions were prophetic of his future greatness. At the risk, however, of incurring a charge of this kind, I repeat that Dickens' first story is well told, and that the editor of The Old Monthly Magazine showed due discernment in accepting it and encouraging his unknown contributor to further [Pg 32]efforts. Quite apart from the fact that the author was only a young fellow of some two or three and twenty, both this first story and the stories that followed it in The Old Monthly Magazine, during 1834 and the early part of 1835, possessed qualities of a very remarkable kind. So also did the humorous descriptive papers shortly afterwards published in The Evening Chronicle, papers that, with the stories, now compose the book known as "Sketches by Boz." Sir Arthur Helps, speaking of Dickens, just after Dickens' death,[5] said, "His powers of observation were almost unrivalled.... Indeed, I have said to myself when I have been with him, he sees and observes nine facts for any two that I see and observe." This particular faculty is, I think, almost as clearly discernible in the "Sketches" as in the author's later and greater works. London—its sins and sorrows, its gaieties and amusements, its suburban gentilities, and central squalor, the aspects of its streets, and the humours of the dingier classes among its inhabitants,—all this had certainly never been so seen and described before. The power of exact minute delineation lavished upon the picture is admirable. Again, the dialogue in the dramatic parts is natural, well-conducted, characteristic, and so used as to help, not impede, the narrative. The speech, for instance, of Mr. Bung, the broker's man, is a piece of very good Dickens. Of course there is humour, and very excellent fooling some of it is; and equally, of course, there is pathos, and some of that is not bad. Do I mean at all that this earlier work stands on the same level of excellence as the masterpieces of the writer? Clearly not. It [Pg 33]were absurd to expect the stripling, half-furtively coming forward, first without a name at all, and then under the pseudonym of Boz,[6] to write with the superb practised ease and mastery of the Charles Dickens who penned "David Copperfield." By dint of doing blacksmith's work, says the French proverb, one becomes a blacksmith. The artist, like the handicraftsman, must learn his art. Much in the "Sketches" betrays inexperience; or, perhaps, it would be more just to say, comparative clumsiness of hand. The descriptions, graphic as they undoubtedly are, lack for the most part the final imaginative touch; the kind of inbreathing of life which afterwards gave such individual charm to Dickens' word-painting. The humour is more obvious, less delicate, turns too readily on the claim of the elderly spinster to be considered young, and the desire of all spinsters to get married. The pathos is often spoilt by over-emphasis and declamation. It lacks simplicity.

For the "Sketches" published in The Old Monthly Magazine, Dickens got nothing, beyond the pleasure of seeing himself in print. The Chronicle treated him somewhat more liberally, and, on his application, increased his salary, giving him, in view of his original contributions, seven guineas a week, instead of the five guineas which he had been drawing as a reporter. Not a particularly brilliant augmentation, perhaps, and one at which he must often have smiled in after years, when his pen was dropping gold as well as ink. Still, the addition to his income was substantial, and the son of John Dickens must [Pg 34]always, I imagine, have been in special need of money. Moreover the circumstances of the next few months would render any increased earnings doubly pleasant. For Dickens was shortly after this engaged to be married to Miss Catherine Hogarth, the daughter of one of his fellow-workers on the Chronicle. There had been, so Forster tells us, a previous very shadowy love affair in his career,—an affair so visionary indeed, and boyish, as scarcely to be worthy of mention in this history, save for three facts: first, that his devotion, dreamlike as it was, seems to have had love's highest practical effect in inducing him to throw his whole strength into the study of shorthand; secondly, that the lady of his love appears to have had some resemblance to Dora, the child-wife of David Copperfield; and thirdly, that he met her again long years afterwards, when time had worked its changes, and the glamour of love had left his eyes, and that to that meeting we owe the passages in "Little Dorrit" relating to poor Flora. This, however, is a parenthesis. The engagement to Miss Hogarth was neither shadowy nor unreal—an engagement only in dreamland. Better for both, perhaps—who knows?—if it had been. Ah me, if one could peer into the future, how many weddings there are at which tears would be more appropriate than smiles and laughter! Would Charles Dickens and Catherine Hogarth have foreborne to plight their troth, one wonders, if they could have foreseen how slowly and surely the coming years were to sunder their hearts and lives?—They were married on the 2nd of April, 1836.

This date again leads me to a time subsequent to the publication of the first number of "Pickwick," which had [Pg 35]appeared a day or two before;—and again I refrain from dealing with that great book. For before I do so, I wish to pause a brief space to consider what manner of man Charles Dickens was when he suddenly broke on the world in his full popularity; and also what were the influences, for good and evil, which his early career had exercised upon his character and intellect.

What manner of man he was? In outward aspect all accounts agree that he was singularly, noticeably prepossessing—bright, animated, eager, with energy and talent written in every line of his face. Such he was when Forster saw him, on the occasion of their first meeting, when Dickens was acting as spokesman for the insurgent reporters engaged on the Mirror. So Carlyle, who met him at dinner shortly after this, and was no flatterer, sketches him for us with a pen of unwonted kindliness. "He is a fine little fellow—Boz, I think. Clear, blue, intelligent eyes, eyebrows that he arches amazingly, large protrusive rather loose mouth, a face of most extreme mobility, which he shuttles about—eyebrows, eyes, mouth and all—in a very singular manner while speaking. Surmount this with a loose coil of common-coloured hair, and set it on a small compact figure, very small, and dressed à la D'Orsay rather than well—this is Pickwick. For the rest, a quiet, shrewd-looking little fellow, who seems to guess pretty well what he is and what others are."[7] Is not this a graphic little picture, and characteristic even to the touch about D'Orsay, the dandy French Count? For Dickens, like the young men [Pg 36]of the time—Disraeli, Bulwer, and the rest—was a great fop. We, of these degenerate days, shall never see again that antique magnificence in coloured velvet waistcoats.

But to return. Dickens, it need scarcely be said, had by this [time][8] long out-lived the sickliness of his earlier years. The hardships and trials of his childhood and boyhood had served but to brace his young manhood, knitting the frame and strengthening the nerves. Light and small, as Carlyle describes him, he was wiry and very active, and could bear without injury an amount of intellectual work and bodily fatigue that would have killed many men of seemingly stronger build. And as what might have seemed unfortunate in his youth had helped perchance to develop his physical powers, so had it assisted to strengthen his character and foster his genius. I go back here to the point from which I started. No doubt a weaker man would have been crushed by such a youth. He would have been indolently content to remain a warehouse drudge, would have listlessly fallen into his father's ways about money, would have had no ambition beyond his desk and salary as a lawyer's clerk, would have never cared to piece together and supplement the scattered scraps of his education, would have rested on his oars when he had once shot into the waters of ordinary journalism. With Dickens it was not so. The alchemy of a fine nature had transmuted his disadvantages into gold. To him the lessons of such a childhood and boyhood as he had had, were energy, self-reliance, a determination to overcome all obstacles, to fight the battles of life, in all honour and rectitude, so as to win. From the muddle of his father's affairs he had taken away [Pg 37]a lesson of method, order, and punctuality in business and other arrangements. "What is worth doing at all is worth doing well," was not only one of his favourite maxims—it was the rule of his life.

And for what was to be his life work, what better preparation could there have been than that which he received? I am far from recommending warehouses, squalid solitary lodgings, pawnshops, debtors' prisons,—if such could now be found,—ill-conducted private schools,—which probably could be found,—attorneys' offices, and the hand-to-mouth of journalism, as constituting generally the highest ideal of a liberal education. I am equally far from asserting that the majority of men do not require more training of a purely scholastic kind than fell to Dickens' lot. But Dickens was not a bookish man. His genius did not lie in that direction. To have forced him unduly into the world of books would have made him, doubtless, an average scholar, but might have weakened his hold on life. Such a risk was certainly not worth the running. Fate arranged it otherwise. What he was above all was a student of the world of men, a passionately keen observer of the ways of humanity. Men were to be his books, his special branch of knowledge; and in order to graduate and take high honours in that school, I repeat, he could have had no better training. Not only had he passed through a range of most unwonted experiences, experiences calculated to quicken to the uttermost his superb faculties of observation and insight; but he had been placed in sympathetic communication with a strange assortment of characters, lying quite out of the usual ken of the literary classes. Knowledge and sympathy, the [Pg 38]seeing eye and the feeling heart—were these nothing to have acquired?

That so abnormal an education can have been entirely without drawbacks, it is no part of my purpose to affirm. Tossed, as one may say, to sink or swim amid the waves of life, where those waves ran turbid and brackish, Dickens had emerged strengthened, triumphant. But that some little signs should not remain of the straining and effort with which he had won the land, was scarcely to be expected. He himself, in his more confidential communications with Forster, seems to avow a consciousness that this was so; and Forster, though he speaks guardedly, lovingly, appears to be of opinion that a certain self-assertiveness and fierce intolerance of advice or control[9] occasionally discernible in his friend, might justly be attributed to the harsh influence of early struggles and privations. But what then? That system of education has yet to be devised which shall mould this poor human clay of ours into flawless shapes of use and beauty. A man may be considered fortunate indeed, when his training has left in him only what the French call the "defects [Pg 39]of his virtues," that is, the exaggeration of his good qualities till they turn into faults. Without his immense strength of purpose and iron will, Dickens might never have emerged from obscurity, and the world would have been very distinctly the poorer. One cannot be very sorry that he possessed these gifts in excess.

And now, at last, having slightly sketched the history of his earlier years, and endeavoured to show, however perfectly, what influences had gone to the formation of his character, I proceed to consider the book that lifted him to fame and fortune. The years of apprenticeship are over, and the master-workman brings forth his finished work in its flower of perfection. Let us study "Pickwick."

[5] Macmillan's Magazine, July, 1870.

[6] It was the pet name of one of his brothers; that was why he took it.

[7] Froude's "Thomas Carlyle: A History of his Life in London."

[8] Transcriber's Note: The word "time" appears to be missing from the original text.

[9] "I have heard Dickens described by those who knew him," says Mr. Edmund Yates, in his "Recollections," "as aggressive, imperious, and intolerant, and I can comprehend the accusation.... He was imperious in the sense that his life was conducted on the sic volo sic jubeo principle, and that everything gave way before him. The society in which he mixed, the hours which he kept, the opinions which he held, his likes and dislikes, his ideas of what should or should not be, were all settled by himself, not merely for himself, but for all those brought into connection with him, and it was never imagined they could be called in question.... He had immense powers of will."

Dickens has told us, in his preface to the later editions, much of how "Pickwick" came to be projected and published. It was in this wise: Seymour, a caricaturist of very considerable merit, though not, as we should now consider, in the first rank of the great caricaturists, had proposed to Messrs. Chapman and Hall, then just starting on their career as publishers, a "series of Cockney sporting plates." Messrs. Chapman and Hall entertained the idea favourably, but opined that the plates would require illustrative letter-press; and casting about for some suitable author, bethought themselves of Dickens, whose tales and sketches had been exciting some little sensation in the world of journalism; and who had, indeed, already written for the firm a story, the "Tuggs at Ramsgate," which may be read among the "Sketches." Accordingly Mr. Hall called on Dickens for the purpose of proposing the scheme. This would be in 1835, towards the latter end of the year; and Dickens, who had apparently left the paternal roof for some little time, was living bachelorwise, in Furnival's Inn. What was his astonishment, when Mr. Hall came in, to find he was the same person who had sold him the copy of the magazine containing his [Pg 41]first story—that memorable copy at which he had looked, in Westminster Hall, through eyes bedimmed with joyful tears. Such coincidences always had for Dickens a peculiar, almost a superstitious, interest. The circumstance seemed of happy augury to both the "high contracting parties." Publisher and author were for the nonce on the best of terms. The latter, no doubt, saw his opening; was more than ready to undertake the work, and had no quarrel with the remuneration offered. But even then he was not the man to play second fiddle to anybody. Before they parted, he had quite succeeded in turning the tables on Seymour. The original proposal had been that the artist should produce four caricatures on sporting subjects every month, and that the letter-press should be in illustration of the caricatures. Dickens got Mr. Hall to agree to reverse that position. He, Dickens, was to have the command of the story, and the artist was to illustrate him. How far these altered relations would have worked quite smoothly if Seymour had lived, and if Dickens' story had not so soon assumed the proportions of a colossal success, it is idle to speculate. Seymour died by his own hand before the second number was published, and so ceased to be in a position to assert himself. It was, however, in deference to the peculiar bent of his art that Mr. Winkle, with his disastrous sporting proclivities, made part of the first conception of the book; and it is also very significant of the book's origin, that the design on the green wrapper in which the monthly parts made their appearance, should have had a purely sporting character, and exhibited Mr. Pickwick sleepily fishing in a punt, and Mr. Winkle shooting at what looks like a cock-sparrow, [Pg 42]the whole surrounded by a chaste arabesque of guns, rods, and landing-nets. To Seymour, too, we owe the portrait of Mr. Pickwick, which has impressed that excellent old gentleman's face and figure upon all our memories. But to return to Dickens' interview with Mr. Hall. They seem to have parted in mutual satisfaction. At least it is certain Dickens was satisfied, for in a letter written, apparently on the same day, to "my dearest Kate," he thus sums up the proposals of the publishers: "They have made me an offer of fourteen pounds a month to write and edit a new publication they contemplate, entirely by myself, to be published monthly, and each number to contain four wood-cuts.... The work will be no joke, but the emolument is too tempting to resist."[10]

So, little thinking how soon he would begin to regard the "emolument" as ludicrously inadequate, he set to work on "Pickwick." The first part was published on the 31st of March or 1st of April, 1836.

That part seems scarcely to have created any sensation. Mr James Grant, the novelist, says indeed, that the first five parts were "a dead failure," and that the publishers were even debating whether the enterprise had not better be abandoned altogether, when suddenly Sam Weller appeared upon the scene, and turned their gloom into laughter. Be that as it may, certain it is that before many months had passed, Messrs. Chapman and Hall must have been thoroughly confirmed in a policy of perseverance. "The first order for Part I.," that is, the first order for binding, "was," says the bookbinder who executed the work, "for four hundred copies [Pg 43]only." The order for Part XV. had risen to forty thousand. All contemporary accounts agree that the success was sudden, immense. The author, like Lord Byron, some twenty-five years before, "awoke and found himself famous." Young as he was, not having yet numbered more than twenty-four summers, he at one stride reached the topmost height of popularity. Everybody read his book. Everybody laughed over it. Everybody talked about it. Everybody felt, confusedly perhaps, but very surely, that a new and vital force had arisen in English literature.

And English literature just then was in one of its times of slackness, rather than full flow. The great tide of the beginning of the century had ebbed. The tide of the Victorian age had scarcely begun to do more than ripple and flash on the horizon. Byron was dead, and Shelley and Keats and Coleridge and Lamb; Southey's life was on the decline; Wordsworth had long executed his best work; while of the coming men, Carlyle, though in the plenitude of his power, having published "Sartor Resartus," had not yet published his "French Revolution,"[11] or delivered his lectures on the "Heroes," and was not yet in the plenitude of his fame and influence; and Macaulay, then in India, was known only as the essayist and politician; and Lord Tennyson and the Brownings were more or less names of the future. Looking especially at fiction, the time may be said to have been waiting for its master-novelist. Five years had gone by since the good and great Sir Walter Scott had been laid to rest in Dryburgh Abbey, [Pg 44] there to sleep, as is most fit, amid the ruins of that old Middle Age world he loved so well, with the babble of the Tweed for lullaby. Nor had any one shown himself of stature to step into his vacant place, albeit Bulwer, more precocious even than Dickens, was already known as the author of "Pelham," "Eugene Aram," and the "Last Days of Pompeii;" and Disraeli had written "Vivian Grey," and his earlier books; while Thackeray, Charlotte Brontë, Kingsley, George Eliot were all, of course, to come later. No, there was a vacant throne among the novelists. Here was the hour—and here, too, was the man. In virtue of natural kingship he took up his sceptre unquestioned.

Still, it may not be superfluous to inquire into the why and wherefore of his success. All effects have a cause. What was the cause of this special phenomenon? In the first place, the admirable freshness of the book won its way into every heart. There is a fervour of youth and healthy good spirits about the whole thing. In a former generation, Byron had uttered his wail of despair over a worthless world. We, in our own time, have got back to the dreary point of considering whether life be worth living. Here was a writer who had no such misgivings. For him life was pleasant, useful, full of delight—to be not only tolerated, but enjoyed. He liked its sights, its play of character, its adventures—affected no superiority to its amusements and convivialities—thoroughly laid himself out to please and to be pleased. And his characters were in the same mood. Their fund of animal spirits seemed inexhaustible. For life's jollities they were never unprepared. No doubt there were [Pg 45]"mighty mean moments" in their existence, as there have been in the existence of most of us. It cannot have been pleasant to Mr. Winkle to have his eye blackened by the obstreperous cabman. Mr. Tracy Tupman probably felt a passing pang when jilted by the maiden aunt in favour of the audacious Jingle. No man would elect to occupy the position of defendant in an action for breach of promise, or prefer to sojourn in a debtors' prison. But how jauntily do Mr. Pickwick and his friends shake off such discomforts! How buoyantly do they override the billows that beset their course! And what excellent digestions they have, and how slightly do they seem to suffer the next day from any little excesses in the matter of milk punch!

Then besides the good spirits and good temper, there is Dickens' royal gift of humour. As some actors have only to show their face and utter a word or two, in order to convulse an audience with merriment, so here does almost every sentence hold good and honest laughter. Not, perhaps, objects the superfine and too dainty critic, humour of the most delicate sort—not humour that for its rare and exquisite quality can be placed beside the masterpieces in that kind of Lamb, or Sterne, or Goldsmith, or Washington Irving. Granted freely; not humour of that special character. But very good humour nevertheless, the thoroughly popular humour of broad comedy and obvious farce—the humour that finds its account where absurd characters are placed in ridiculous situations, that delights in the oddities of the whimsical and eccentric, that irradiates stupidity and makes dulness amusing. How thoroughly wholesome it is too! To be at the same time [Pg 46]merry and wise, says the old adage, is a hard combination. Dickens was both. With all his boisterous merriment, his volleys of inextinguishable laughter, he never makes game of what is at all worthy of respect. Here, as in his later books, right is right, and wrong wrong, and he is never tempted to jingle his jester's bell out of season, and make right look ridiculous. And if the humour of "Pickwick" be wholesome, it is also most genial and kindly. We have here no acrid cynic sneeringly pointing out the plague spots of humanity, and showing pleasantly how even the good are tainted with evil. Rather does Dickens delight in finding some touch of goodness, some lingering memory of better things, some hopeful aspiration, some trace of unselfish devotion in characters where all seems soddened and lost. In brief, the laughter is the laughter of one who sees the foibles, and even the vices of his fellow-men, and yet looks on them lovingly and helpfully.

So much the first readers of "Pickwick" might note as the book unfolded itself to them, part by part; and they might also note one or two things besides. They might note—they could scarcely fail to do so—that though there was a touch of caricature in nearly all the characters, yet those characters were, one and all, wonderfully real, and very much alive. It was no world of shadows to which the author introduced them. Mr. Pickwick had a very distinct existence, and so had his three friends, and Bob Sawyer, and Benjamin Allen, and Mr. Jingle, and Tony Weller, and all the swarm of minor characters. While as to Sam Weller, if it be really true that he averted impending ruin from the book, and turned defeat [Pg 47]into victory, one can only say that it was like him. When did he ever "stint stroke" in "foughten field"? By what array of adverse circumstances was he ever taken at a disadvantage? To have created a character of this vitality, of this individual force, would be a feather in the cap of any novelist who ever lived. Something I think of Dickens' own blood passed into this special progeniture of his. It has been irreverently said that Falstaff might represent Shakespeare in his cups, just as Hamlet might represent him in his more sober moments. So I have always had a kind of fancy that Sam Weller might be regarded as Dickens himself seen in a certain aspect—a sort of Dickens, shall I say?—in an humbler sphere of life, and who had never devoted himself to literature. There is in both the same energy, pluck, essential goodness of heart, fertility of resource, abundance of animal spirits, and also an imagination of a peculiar kind, in which wit enters as a main ingredient. And having noted how highly vitalized were the characters in "Pickwick," I think the first readers might also fairly be expected to note,—and, in fact, it is clear from Dickens' preface that they did note—how greatly the book increased in scope and power as it proceeded. The beginning was conceived almost in a spirit of farce. The incidents and adventures had scarcely any other object than to create amusement. Mr. Pickwick himself appeared on the scene with fantastic honours and the badge of absurdity, as "the man who had traced to their source the mighty ponds of Hampstead, and agitated the scientific world with the Theory of Tittlebats." But in all this there is a gradual change. Mr. Pickwick is presented to us latterly as an exceedingly sound-headed as well as [Pg 48]sound-hearted old gentleman, whom we should never think of associating with the sources of Hampstead Ponds or any other folly. While in such scenes as those at the Fleet Prison, the author is clearly endeavouring to do much more than raise a laugh. He is sounding the deeper, more tragic chords in human feeling.

Ah, if we add to all this—to the freshness, the "go," the good spirits, the keen observation, the graphic painting, the humour, the vitality of the characters, the gradual development of power—if we add to all this that something which is in all, and greater than all, viz., genius, and genius of a highly popular kind, then we shall have no difficulty in understanding why everybody read "Pickwick," and how it came to pass that its publishers made some £20,000 by a work that they had once thought of abandoning as worthless.[12]

[10] See the Letters published by Chapman and Hall.

[11] It was finished in January, 1837, and not published till six months afterwards.

[12] They acknowledged to Dickens that they had made £14,000 by the sale of the monthly parts alone.

Dickens was not at all the man to rest on his oars while "Pickwick" was giving such a magnificent impetus to the boat that contained his fortunes. The amount of work which he accomplished in the years 1836, 1837, 1838, and 1839 is, if we consider its quality, amazing. "Pickwick," as we have seen, was begun with the first of these years, and its publication continued till the November of 1837. Independently of his work on "Pickwick," he was, in the year 1836, engaged in the arduous profession of a reporter till the close of the parliamentary session, and also wrote a pamphlet on Sabbatarianism, a farce in two acts, "The Strange Gentleman," for the St. James's Theatre, and a comic opera, "The Village Coquettes," which was set to music by Hullah. With the very commencement of 1837—"Pickwick," it will be remembered, going on all the while—he entered upon the duties of editor of Bentley's Miscellany, and in the second number began the publication of "Oliver Twist," which was continued into the early months of 1839, when his connection with the magazine ceased. In the April of 1838, and simultaneously, of course, with "Oliver Twist," appeared [Pg 50]the first part of "Nicholas Nickleby"—the last part appearing in the October of the following year. Three novels of more than full size and of first-rate importance, in less than four years, besides a good deal of other miscellaneous work—certainly that was "good going." The pace was decidedly fast. Small wonder that The Quarterly Review, even so early as October, 1837, was tempted to croak about "Mr. Dickens" as writing "too often and too fast, and putting forth in their crude, unfinished, undigested state, thoughts, feelings, observations, and plans which it required time and study to mature," and to warn him that as he had "risen like a rocket," so he was in danger of "coming down like the stick." Small wonder, I say, and yet to us now, how unjust the accusation appears, and how false the prophecy. Rapidly as those books were executed, Dickens, like the real artist that he was, had put into them his best work. There was no scamping. The critics of the time judged superficially, not making allowance for the ample fund of observations he had amassed, for the genuine fecundity of his genius, and for the admirable industry of an extremely industrious man. "The World's Workers"—there exists under that general designation a series of short biographies, for which Miss Dickens has written a sketch of her father's life. To no one could the description more fittingly apply. Throughout his life he worked desperately hard. He possessed, in a high degree, the "infinite faculty for taking pains," which is so great an adjunct to genius, though it is not, as the good Sir Joshua Reynolds held, genius itself. Thus what he had done rapidly was done [Pg 51]well; and, for the rest, the writer, who had yet to give the world "Martin Chuzzlewit," "The Christmas Carol," "David Copperfield," and "Dombey," was not "coming down like a stick." There were many more stars, and of very brilliant colours, to be showered out by that rocket; and the stick has not even yet fallen to the ground.[13]

Naturally, with the success of "Pickwick," came a great change in Dickens' pecuniary position. He had, as we have seen, been glad enough, before he began the book, to close with the offer of £14 for each monthly part. That sum was afterwards increased to £15, and the two first payments seem to have been made in advance for the purpose of helping him to defray the expenses of his marriage. But as the sale leapt up, the publishers themselves felt that such a rate of remuneration was altogether insufficient, and sent him, first and last, a goodly number of supplementary cheques, for sums amounting in the aggregate, as they computed, to £3,000, and as Forster computes to about £2,500. This Dickens, who, to use his own words, "never undervalued his own work," considered a very inadequate percentage on their gains—forgetting a little, perhaps, that the risks had been wholly theirs, and that he had been more than content with the original bargain. Similarly he was soon utterly dissatisfied with his arrangements with Bentley about the editorship of the Miscellany and "Oliver Twist,"—arrangements which had been [Pg 52]entered into in August, 1836, while "Pickwick" was in progress; and he utterly refused to let that publisher have "Gabriel Varden, The Locksmith of London" ("Barnaby Rudge") on the terms originally agreed upon. With Macrone also, who had made some £4,000 by the "Sketches," and given him about £400, he was no better pleased, especially when that enterprising gentleman threatened a re-issue in monthly parts, and so compelled him to re-purchase the copyright for £2,000. But however much he might consider himself ill-treated by the publishing fraternity, he was, of course, rapidly getting far richer than he had been, and so able to enlarge his mode of life. He had begun, modestly enough, by taking his wife to live with him in his bachelor's quarters in Furnival's Inn,—much as Tommy Traddles, in "David Copperfield," took his wife to live in chambers at Gray's Inn; and there, in Furnival's Inn, his first child, a boy, was born on the 6th of January, 1837. But in the March of that year he moved to a more commodious dwelling, at 48, Doughty Street, where he remained till the end of 1839, when still increasing means enabled him to move to a still better house at 1, Devonshire Terrace, Regent's Park. But the house in Doughty Street must have been endeared to him by many memories. It was there, on the 7th of May, 1837, that he lost, at the early age of seventeen, and quite suddenly, a sister-in-law, Mary Hogarth, to whom he was greatly attached. The blow fell so heavily at the time as to incapacitate him from all work, and delayed the publication of one of the numbers of "Pickwick." Nor was the sorrow only sharp and [Pg 53]transient. He speaks of her in the preface to the first edition of that book. Her spirit seemed to be hovering near as he stood looking at Niagara. He felt her hallowing influence when in danger of growing too much elated by his first reception in America. She came back to him in dreams in Italy. Her image remained in his heart, unchanged by time, as he declared, to the very end. She represented to his mind all that was pure and lovely in opening womanhood, and lives, in the world created by his art, as the Little Nell of "The Old Curiosity Shop." It was in Doughty Street, too, that he began to gather round him the circle of friends whose names seem almost like a muster-roll of the famous men and women in the first thirty years of Queen Victoria's reign. I shall not enumerate them. The list of writers, artists, actors, would be too long. But this at least it would be unjust not to note, that among his friends were included nearly all those who by any stretch of fancy could be regarded as his rivals in the fields of humour and fiction. With Washington Irving, Hood, Douglas Jerrold, Lord Lytton, Harrison Ainsworth, Mr. Wilkie Collins, Mrs. Gaskell, and, save for a passing foolish quarrel, with Thackeray, the novelist who really was his peer, he maintained the kindliest and most cordial relations. Nor when George Eliot published her first books, "The Scenes of Clerical Life" and "Adam Bede," did any one acknowledge their excellence more freely. Petty jealousies found no place in the nature of this great writer.