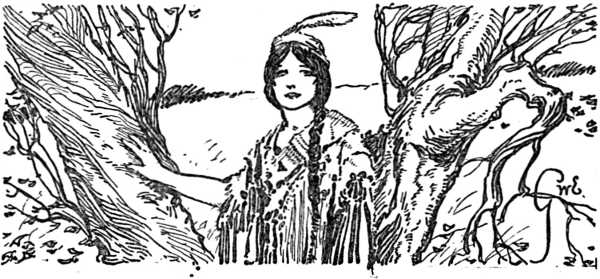

Title: The Princess Pocahontas

Author: Virginia Watson

Illustrator: George Wharton Edwards

Release date: August 6, 2005 [eBook #16458]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mark C. Orton, Taavi Kalju and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

To most of us who have read of the early history of Virginia only in our school histories, Pocahontas is merely a figure in one dramatic scene—her rescue of John Smith. We see her in one mental picture only, kneeling beside the prostrate Englishman, her uplifted hands warding off the descending tomahawk.

By chance I began to read more about the settlement of the English at Jamestown and Pocahontas' connection with it, and the more I read the more interesting and real she grew to me. The old chronicles gave me the facts, and guided by these, my imagination began to follow the Indian maiden as she went about the forests or through the villages of the Powhatans.

We are growing up in this new country of ours. And just as when children get older they begin to feel curious about the childhood of their own parents, so we have gained a new curiosity about the early history of our country. The earlier histories and stories dealing with the Indians and the wars between them and the colonists made the red man a devil incarnate, with no redeeming virtue but that of courage. Now, however, there is a new spirit of understanding. We are finding out how often it was the Indian who was wronged and the white man who wronged him. Many records there are of treaties faithfully kept by the Indians and faithlessly broken by the colonists. Virginia was the first permanent English settlement on this continent, and if not the most important, at least equally as important to our future development as that of New England. From how small a seed, sown on that island of Jamestown in 1607, has sprung the mighty State, that herself has scattered seeds of other states and famous men and women to multiply and enrich America. And amid what dangers did this seed take root! But for one girl's aid—as far as man may judge—it would have been uprooted and destroyed.

In truth, when I look over the whole world history, I can find no other child of thirteen, boy or girl, who wielded such a far-reaching influence over the future of a nation. But for the protection and aid which Pocahontas coaxed from Powhatan for her English friends at Jamestown, the Colony would have perished from starvation or by the arrows of the hostile Indians. And the importance of this Colony to the future United States was so great that we owe to Pocahontas somewhat the same gratitude, though in a lesser degree, that France owes to her Joan of Arc.

Pocahontas's greatest service to the colonists lay not in the saving of Captain Smith's life, but in her continued succour to the starving settlement. Indeed, there are historians who have claimed that the story of her rescue of Smith is an invention without foundation. But in opposition to this view let me quote from "The American Nation: A History." Lyon Gardiner Tyler, author of the volume "England in America" says:

"The credibility of this story has been attacked.... Smith was often inaccurate and prejudiced in his statements, but that is far from saying that he deliberately mistook plain objects of sense or concocted a story having no foundation."

and from "The New International Encyclopaedia":

"Until Charles Deane attacked it (the story of Pocahontas's rescue of Smith) in 1859, it was seldom questioned, but, owing largely to his criticisms, it soon became generally discredited. In recent years, however, there has been a tendency to retain it."

It is in Smith's own writings, "General Historie of Virginia" and "A True Relation," that we find the best and fullest accounts of these first days at Jamestown. He tells us not only what happened, but how the new country looked; what kinds of game abounded; how the Indians lived, and what his impressions of their customs were. Smith was ignorant of certain facts about the Indians with which we are now familiar. The curious ceremony which took place in the hut in the forest, just before Powhatan freed Smith and allowed him to return to Jamestown, was one he could not comprehend. Modern historians believe that it was probably the ceremony of adoption by which Smith was made one of the tribe.

In many places in this story I have not only followed closely Smith's own narrative of what occurred, but have made use of the very words in which he recorded the conversations. For instance the incident related on page 101 was set down by Smith himself; on pages 144, 154, 262 the words are those of Smith as given in his history; on pages 173, 195, 260, 300 the words of Powhatan or Pocahontas as Smith relates them.

There may be readers of this story who will want to know what became of Pocahontas. She fell ill of a fever just as she was about to sail home for Virginia and died in Gravesend, where she was buried. Her son Thomas Rolfe was educated in England and went to Virginia when he was grown. His daughter Jane married John Bolling, and among their descendants have been many famous men and women, including Edith Bolling (Mrs. Galt) who married President Woodrow Wilson.

Through the white forest came Opechanchanough and his braves, treading as silently as the flakes that fell about them. From their girdles hung fresh scalp locks which their silent Monachan owners did not miss.

But Opechanchanough, on his way to Werowocomoco to tell The Powhatan of the victory he had won over his enemies, did not feel quite sure that he had slain all the war party against which he and his Pamunkey braves had gone forth. The unexpected snow, coming late in the winter, had been blown into their eyes by the wind so that they could not tell whether some of the Monachans had not succeeded in escaping their vengeance. Perhaps, even yet, so near to the wigwams of his brother's town, the enemy might have laid an ambush. Therefore, it behooved them to be on their guard, to look behind each tree for crouching figures and to harken with all their ears that not even a famished squirrel might crack a nut unless they could point out the bough on which it perched.

Opechanchanough led the long thin line that threaded its way through the broad cutting between huge oaks, still bronze with last year's leaves. He held his head high and to himself he framed the words of the song of triumph he meant to sing to The Powhatan, as the chief of the Powhatans was called. Then, suddenly before his face shot an arrow.

At a shout from their leader, the long line swung itself to the right, and fifty arrows flew to the northward, the direction from which danger might be expected. Still there was silence, no outcry from an ambushed enemy, no sign of other human creatures.

Opechanchanough consulted with his braves whence had the arrow come; and even while they talked, another arrow from the right whizzed before his face.

"A bad archer," he grunted, "who cannot hit me with two shots." Then pointing to a huge oak that forked half way up, he commanded:

"Bring him to me."

Two braves rushed forward to the tree, on which all eyes were now fixed. It was difficult to distinguish anything through the falling snow and the mass of its flakes that had gathered in the crotch. All was white there, yet there was something white which moved, and the two braves on reaching the tree trunk yelled in delight and disdain.

The white figure moved rapidly now. Swinging itself out on a branch and catching hold of a higher one, it seemed determined to retreat from its pursuers to the very summit of the tree. But the braves did not waste time in climbing after it; they leapt up in the air like panthers, caught the branch and swung it vigorously back and forth so that the creature's feet slipped from under it and it fell into their outstretched arms.

Not waiting even to investigate the white bundle of fur, the warriors, surrounded by their curious fellows, bore it to Opechanchanough, and laid it on the ground before him. He knelt and lifted up the cap of rabbit skin with flapping ears that hid the face, then cried out in angry astonishment:

"Pocahontas! What meaneth this trick?"

And the white fur bundle, rising to her feet, laughed and laughed till the oldest and staidest warrior could not help smiling. But Opechanchanough did not smile; he was too angry. His dignity suffered at thus being made the sport of a child. He shook his niece, saying:

"What meaneth this, I ask? What meaneth this?"

Pocahontas then ceased laughing and answered:

"I wanted to see for myself how brave thou wert. Uncle, and to know just how great warriors such as ye are act when an enemy is upon them. I am not so bad an archer, Uncle; I would not shoot thee, so I aimed beyond thee. But it was such fun to sit up there in the tree and watch all of you halt so suddenly."

Her explanation set most of the party laughing again.

"In truth, is she well named," they cried—"Pocahontas, Little Wanton."

"I have yet another name," she said to an old brave who stood nearest her. "Knowest thou it not?—Matoaka, Little Snow Feather. Always when the moons of popanow (winter) bring us snow it calls me out to play. 'Come, Snow Feather,' it cries, 'come out and run with me and toss me up into the air.'"

Her uncle had now recovered his calm and was about to start forward again. Turning to the two who had captured Pocahontas, he commanded:

"Since we have taken a prisoner we will bear her to Powhatan for judgment and safekeeping. Had we shot back into the tree she might have been killed. See that she doth not escape you."

Then he stalked ahead through the forest, paying no further attention to Pocahontas.

The young braves looked sheepishly at each other and at their captive, not at all relishing their duty. Opechanchanough was not to be disobeyed, yet it was no easy thing to hold a young maid against her will, and no force or even show of force might be used against a daughter of the mighty werowance (chieftain).

Seeing their uncertainty, Pocahontas started to run to the left and they to pursue her. They came up with her before she had gone as far as three bows' lengths and led her back gently to their place in the line. Then she walked sedately along as if unconscious of their presence, until they were off their guard, believing she had resigned herself to the situation, when she sprang off to the right and was again captured and led back. She knew that they dared not bind her, and she took advantage of this to lead them in truth a dance, first to one side and then to the other. Behind them their comrades jeered and laughed each time the maiden ran away.

The regular order of the warpath was now no longer preserved. They had advanced to a point where there was no longer any possibility of danger from hostile attack. Werowocomoco lay now but a short distance away; already the smoke from its lodges could be seen across the cleared fields that surrounded the village of Powhatan. The older warriors were walking in groups, talking over their deeds of valor performed that day, and praising those of several of the young braves who had fought for the first time. Pocahontas and her captors had now fallen further behind.

Though well satisfied with the results of her enterprise and amusement, Pocahontas had no mind to be brought into her home as a captive, even though it be half in jest. Her father might not consider it so amusing and, moreover, she did not like to be outwitted. She was so busy thinking that she forgot to continue her game and walked quietly ahead, keeping up with the longer strides of the warriors by occasional little runs forward. The braves, their own heads full of their first campaign, kept fingering lovingly the scalps at their girdles, and paid little attention to her.

She stooped as if to fasten her moccasin, then, as their impetus carried them a few feet ahead of her before they stopped for her to come up, she darted like a flash to the left and had slid down into a little hollow before they thought of starting after her.

It was now almost dark and her white fur was indistinguishable against the snow below. Before they had reached the bottom, Pocahontas, who knew every inch of the ground that was less familiar to men from her uncle's village, had slipped back into the forest which skirted the fields the pursuers were now speeding across, and was lost at once in the darkness.

Opechanchanough knew nothing of this escape. He meant to explain to his royal brother how much mischief a child might do who was not kept at home performing squaw duties in her wigwam. And Powhatan's favorite daughter or not, Pocahontas should be kept waiting outside her father's lodge until he had related his important business and had recounted all the glorious deeds done by his Pamunkeys.

Now they had come to Werowocomoco itself, and the noise of their shoutings and of their war drums brought the inhabitants running out of their wigwams. As the Pamunkeys were an allied tribe, their cause against a common enemy was the same, yet the rejoicings at the victory against the Monachans was somewhat less than it would have been had the conquerors been Powhatans themselves. However, Opechanchanough and his braves could not complain of their reception, and runners sped ahead to advise Powhatan of their coming, while all the population of their village crowded about them, the men questioning, the boys fingering the scalps and each boasting how many he would have at his girdle when he was grown.

The great Werowance was not in his ceremonial lodge but in the one in which he ordinarily slept and ate when at Werowocomoco. Opechanchanough paused at the opening of the lodge and ordered:

"When I call out then bring ye in Pocahontas, and we shall see what Powhatan thinks of a squaw child that shoots at warriors."

The lodge was almost dark when he entered it. Before the fire in the centre he could see his brother Powhatan seated, and on each side of him one of his wives. Then he made out the features of his nephew Nautauquas and Pocahontas' younger sister, Cleopatra (for so it was the English later understood the girl's strange Indian name). They had evidently just been eating supper and the dogs behind them were gnawing the wild turkey bones that had been thrown to them. At Powhatan's feet crouched a child in a dark robe, with face in the shadow.

Powhatan greeted his brother gravely and bade him be seated. The lodge soon filled with braves packed closely together, and about the opening crowded all who could, and these repeated to the men and squaws left outside the words that were spoken within.

Proudly Opechanchanough began to tell how he had tracked the Monachans to a hill above the river, and how he and his war party had fallen upon them, driving them down the steep banks, slaying and scalping, even swimming into the icy water to seize those who sought to escape. And The Powhatan nodded in approval, uttering now and again a word of praise. When Opechanchanough had finished his recital the shaman, or medicine-man, rose and sang a song of praise about the brave Pamunkeys, brothers of the Powhatans.

Then, one after another, Opechanchanough's braves told of their personal exploits.

"I," sang one, "I, the Forest Wolf, have devoured mine enemy. Many suns shall set red between the forest trees, but none so red as the blood that flowed when my sharp knife severed his scalp lock."

And as each recited his deeds his words were received with clappings of hands and grunts of approval.

Powhatan gave orders to open the guest lodge and to prepare a feast for the victors. Then Opechanchanough rose again to speak. After he had finished another song of triumph, he turned to Powhatan and asked:

"Brother, how long hath it been that thy warriors keep within their lodges, leaving to young squaws the duty of sentinels who cannot distinguish friends from foes?"

Powhatan gazed at the speaker in astonishment.

"What dost thou mean by such strange words?" asked the chief.

"As we returned through the forest," explained Opechanchanough, "before we reached the boundary of thy fields, while we still believed that a part of the Monachans might lie in ambush for us there, an arrow, shot from the westward, flew before my face. Then came a second arrow out of the branches of an oak tree. We took the bowman prisoner, and what thinkest thou we found?—a squaw child!"

"A squaw child!" repeated Powhatan in astonishment. "Was it one of this village?"

"Even so. Brother. I have her captive outside that thou mayst pronounce judgment upon one who endangers thus the life of thy brother and who forgetteth she is not a boy. Bring in the prisoner," he commanded.

But no one came forward. The young braves to whom Pocahontas had been entrusted kept wisely on the outskirts of the crowd.

Then the little sombre figure at Powhatan's feet rose and stood with the firelight shining on her face and dark hair and asked in a gentle voice:

"Didst thou want me, mine uncle?"

"Pocahontas," exclaimed Opechanchanough, "how camest thou here ahead of us, and in that dark robe?"

"Pocahontas can run even better than she can shoot. Uncle, and the changing of a robe is the matter but of a moment."

"What meaneth this, Matoaka?" asked Powhatan, making use of her special intimate name, which signified Little Snow Feather. He spoke in a low tone, but one so stern that Cleopatra shivered and rejoiced that she was not the culprit.

"It was but a joke, my father," answered Pocahontas. "I meant no harm." She hung her head and waited until he should speak again.

"I will have no such jokes in my land," he said angrily, "remember that."

With a gesture of his hand and a whispered word of command he sent the Pamunkey braves to the guest lodge. Opechanchanough, still angry at the ridicule that a child had brought upon him, lingered to ask;

"Wilt thou not punish her?"

"Surely I will," Powhatan answered. "Go ye all to the guest lodge and I will follow. Away, Nautauquas, and carry my pipe thither."

They were now alone in the lodge, the great chief over thirty tribes and his daughter, who still stood with downcast head. The Powhatan gazed at her curiously. She waited for him to speak, then as he kept silent, she turned and looked straight into his face and asked:

"Father, dost thou know how hard it is to be a girl? Nautauquas, my brother, is a swift runner, yet I am fleeter than he. I can shoot as straight as he, though not so far. I can go without food and drink as long as he. I can dance without fatigue when he is panting. Yet Nautauquas is to be a great brave and I—thou bidst remember to be a squaw. Is it not hard, my father? Why then didst thou give me strong arms and legs and a spirit that will not be still? Do not blame me. Father, because I must laugh and run and play."

As she spoke she slipped to her knees and embraced his feet and when she had ceased speaking, she smiled up fearless into his face.

Powhatan tried not to be moved by the child's pleading. Yet he was a chief who always harkened to the excuses made by offenders brought before him and judged them justly, if sometimes harshly. This child of his was as dear to him as a running stream to summer heat. If at times its spray dashed too high, could he be angry?

And Pocahontas, seeing that his anger had gone from him, stood up and laid her head against his arm. She did not have to be told that the mighty Powhatan loved no wife nor child of his as he loved her. Then his hand stroked her soft hair and cheek, and she knew that she was forgiven.

"Thine uncle is very angry," he said.

"If thou couldst but have seen him. Father, when the arrow whizzed," and she laughed gaily in memory of the picture.

"I have promised to punish thee."

"Yea, as thou wilt." But she did not speak as if afraid.

"Hear what I charge thee," he said in mock solemnity. "Thou shalt embroider for me with thine own hands—thou that carest not for squaw's needles—a robe of raccoon skin in quills and bits of precious shells."

Pocahontas laughed.

"That is no punishment. 'Tis a strange thing, but when I do things I like not for those I love, why, then I pleasure in doing them. I will fashion for thee such a robe as thou hast never seen. Oh! I know how beautiful it will be. I will make new patterns such as no squaw hath ever dreamed of before. But thou wilt never be really angry with me. Father, wilt thou?" she questioned pleadingly. "And if I should at any time do what displeaseth thee, and thou wearest this robe I make thee, then let it be a token between us and when I touch it thou wilt forgive me and grant what I ask of thee?"

And Powhatan promised and smiled on her before he set forth for the guest lodge.

Some months later on there came a hot day such as sometimes appears in the early spring. The sun shone with almost as much power as if the corn were high above the ground in which it had only just been planted with song and the observance of ancient sacred rites and dances. Little leaves glistened like fish scales, as they gently unfurled themselves on the walnut and persimmon trees about Werowocomoco, and in the forest the ground was covered with flowers. The children tied them together and tossed them as balls to and fro or wound them into chaplets for their hair; the old squaws searched among them for certain roots and leaves for dyes to stain the grass cloth they spun, called pemmenaw.

The boys played hunters, pretending their dogs were wild beasts, but the bears and wolves did not always understand the parts assigned them and frolicked and leaped up in delight upon their little masters instead of turning upon them ferociously. The elder braves lay before their lodges, many of them idling in the sunshine, others busied themselves making arrows, fitting handles to stone knives or knotting crab nets. Two slaves, brought home prisoners by a war party, were hollowing out a dugout, which the Powhatans used instead of the birchbark canoes preferred by other tribes. They had cut down an oak tree that, judging from its rings, must have been an acorn when Powhatan was a papoose, seventy years before. They had burned out a portion of the outer and inner bark and were now hacking at the heart of the wood with sharp obsidian axes.

The squaws were also all busy out of doors, though they chatted in groups as eagerly as if their energy were being expended by their tongues only. Many were at work scraping deerskin to soften it before they cut it into robes for themselves or into moccasins for the men. Here and there little puffs of smoke that seemed to come from beneath the earth testified to the dinners that were being cooked under heated stones.

Pocahontas was seated upon a small hill overlooking the village. As the chief's daughter, it was only on special occasions and as an honored guest, that she joined the knots of squaws or maidens chatting before the wigwams. But she was not alone now in solitary grandeur. She was accustomed to surround herself, when she desired company, with a number of younger girls of the tribe who obeyed her, less because she was the daughter of the feared werowance, than because she had a way with her that made it pleasant to do as she willed and difficult to oppose her. Cleopatra, her youngest sister, sat beside her, trying to coax a squirrel on the branch above them to come down and eat some parched corn from her hands.

Over Pocahontas's knees was spread a robe of raccoon skin, smooth, painted in a wide border. Along the edge of this she was embroidering a deep pattern of white beads made from sea shells. A basket of reeds beside her was full of other beads, large and small, white, red, yellow and blue.

"What doth thy pattern mean, Pocahontas?" asked the girl nearest her. "As it is not one any of our mothers hath ever wrought before, thou must have a meaning for it in thy mind." "Yes," assented the worker, "it differeth from all other patterns because my father differeth from all other werowances. It meaneth this that I sing:

"See, this line is for the river, this one that goeth up straight is the oak tree and this long line all wavy is the heavens. I make this for my father because I am so proud of him."

"But why, Pocahontas," asked another of her companions, "dost thou not use more of these red beads? They are so like fire, like the blood of an enemy; why dost thou refer the white?"

Pocahontas held her bone needle still for a moment and her face wore a puzzled expression.

"I cannot answer thee exactly, Deer-Eye, since I do not know myself. I love the white beads as I love best to wear a white robe myself, or a white rabbit hood in winter. In the woods I always pick the white flowers, and I love the white wild pigeon best of all the birds except the white seagull. And the white soft clouds high in the heavens I love better than the red and yellow ones when the sun goeth down to sleep in the west. Yet I cannot say why it is so."

As noon approached the day grew hotter, and the fingers wearied of the work. Down in the village the men had ceased their activities and lay stretched out on the shady side of the lodges; only the squaws preparing dinner were still busy.

"Let us go to the waterfall," cried Pocahontas, jumping up suddenly. "Each of you go and beg some food from her mother and hurry back here. I will put my work away and await ye here."

The maidens flew down the hill while Pocahontas and Cleopatra carried the robe and the basket to their lodge. Then, a few minutes later, they were rejoined by their companions and all started off laughing as they ran through the woods.

The stream that flowed into the great river below was now still wide with its spring fulness. A mile away from Werowocomoco it fell over high rocks, then rushing down a gentle incline bubbled over smooth rocky slabs, and made a deep pool below them.

The maidens tossed off their skirts and stood for a moment hesitatingly on the shore. Mocking-birds sang in the oaks above them, startled by their shrill young voices, and on the bare branches of a sycamore tree that had been killed by a lightning bolt a score of raccoons lay curled up in the sunshine.

Pocahontas was the first to spring into the stream, but her comrades quickly followed her, laughing, pushing, crying out the first chill of the water. Only Cleopatra remained standing on the shore.

"Come," called Pocahontas to her; "why dost thou tarry, lazy one?"

"I will not come. The water is too cold."

Cleopatra was about to slip on her skirt again when her sister splashed through the stream to her and half pushed, half pulled her into the pool and then to the rocks partly submerged in the water. There was much screaming and calling, slipping from the rocks into the pool and clambering from the pool back on to the rocks. The water was now pleasantly warm and the dinner awaiting them was forgotten in the pleasure of the first bath of the season.

Deer-Eye, in trying to pull herself back on the rock, caught hold of Cleopatra's foot, who slipped on the mossy surface and fell backwards into the water, hitting her head against a sharp edge. She lost consciousness and sank down into the pool.

Almost before she had disappeared beneath the water Pocahontas had sprung after her, and groping about on the fine smooth sand of the bottom, she caught hold of her sister and brought her to the surface.

Then, with the aid of the terrified maidens, she lifted her up on the bank, the blood flowing freely from a cut on her head. After vainly trying to staunch the wound with damp moss, Pocahontas commanded:

"Hasten as though the Iroquois were coming, and cut me some strong branches."

They obeyed her, hurriedly throwing their skirts about them, and then with their stone knives severed branches and tied them together with deer thongs which they tore from the fringe of their girdles. On top of these they placed leafy branches and lifted the unconscious Cleopatra on to this improvised stretcher. In spite of their remonstrances, Pocahontas insisted upon taking one end of it, while the strongest two of her playmates bore the other.

Through the woods they walked, as silent now as they had been noisy before, but Pocahontas thought her heart-beats sounded as loud as the war drums of the Pamunkeys.

They were still distant many minutes' walk to the village when they caught sight of Pochins, a medicine man famous among many tribes for his powerful manitou, his guardian spirit, which enabled him to communicate with the manitous of the spirit world.

"Pochins, oh Pochins," cried out Pocahontas, "come and help us. I fear my sister is dying, and that I have killed her. She did not wish to go into the water, Pochins, and I pulled her in and now she hath cut her head and the blood floweth from it so that I can not stop it."

The shaman made no answer, but bent down from his great height and looked carefully at the wound, then he took the end of the stretcher from Pocahontas, saying:

"I will bear her to my prayer lodge here nearby."

Even then through the trees they caught sight of the bark covering of the lodge, which few persons had ever entered. The maidens shuddered at the sight of it, for none of them knew what mysterious terrors might lie in wait for them there. Nevertheless they followed Pochins as he bore Cleopatra inside and laid her on the ground. From an earthen bowl he took certain herbs and bound the leaves, after he had moistened them, over the wound. Soon Pocahontas, crouching at her sister's side, could see that the blood had ceased to flow. But no sign of life could be detected in the little body lying there. The hands and feet were clammy and though Pocahontas rubbed them vigorously, she could feel no warmth stirring in them.

The shaman paid, however, no further heed to her. From another bowl he took out a rattle of gourd, and from a peg on one of the rounded supports of the roof he lifted down a horrible mask painted in scarlet, and this he fastened over his face. Then, waving the children out of the way, he began to dance about the two sisters and to chant in a loud voice, shaking the rattle till it seemed as if the din must waken a dead person.

"My medicine is a mighty medicine," he exclaimed in his natural voice to Pocahontas. "Wait a little and thou shalt see what wonders it can do."

And indeed in a few moments Pocahontas felt the pulse start in her sister's arm, saw her eyelids quiver and her feet grow warm. And when the shouting and the shaking of the rattle grew even louder and more hideous, Cleopatra opened her eyes and looked about her in astonishment.

"Mighty indeed is the medicine (the magic) of Pochins," cried the shaman proudly as he laid aside mask and rattle; "it hath brought this maiden back from the dead."

Pocahontas now had to soothe the child, terrified by the sights she had seen and the sounds she had heard. She patted her arms and spoke to her as if she were a papoose on her back:

"Fear not, little one, no evil shall come to thee. Pocahontas watcheth over thee. She will not close her eyes while danger prowleth about. Fear naught, little one."

And Cleopatra clung to her, feeling a sense of security in her sister's fearlessness.

By this time the news of the accident had spread through the village and several squaws, led by Cleopatra's mother, came running to Pochins's lodge. Finding Cleopatra was able to rise, they carried her back with them. The other maidens, now the excitement was over, remembered their empty stomachs and hurried off to recover the dinner they had left behind at the waterfall.

Pocahontas did not go with them. She still sat on the ground beside the medicine man while he busied himself painting the mask where the color had worn off.

"Shaman," she asked, "tell me where went the manitou of my sister while she lay there dead?"

"On a distant journey," he answered; "therefore I had to call so loudly to make it hear me and return."

"Who taught thee thy medicine?" she questioned again.

"The Beaver, my manitou, daughter of Powhatan," he answered.

"And who then will teach me; how shall I learn?"

"Thou needest not such knowledge, since thou art neither a medicine man nor a brave. I, Pochins, will call to Okee, the Great Spirit, for thee when thou hast need of anything, food or raiment or a chief to take thee to his lodge."

"But I should like to do that myself, Pochins," she remonstrated. "Thou dost not know how many things I long to do myself. Let me put on thy mask and take thy rattle, just to see how they feel."

"Nay, nay, touch them not," he cried, stretching out his hand. "The Beaver would be angry with us and would work evil medicine on us."

Pochins was not fond of children. His dignity was so great that he never even noticed them as he strode through the village. But the eager look in Pocahontas's eyes seemed to draw words out of him. He began to talk to her of the many days and nights he had spent alone, fasting, in the prayer lodge until some message came to him from Okee, some message about the harvest or the success of a hunting party. Pocahontas was so interested that she asked him many questions.

"Tell me of Michabo, Michabo, the Great Hare," she coaxed, as she moved over on a mat Pochins had spread for her.

"Hearken, then, daughter of The Powhatan," he began, his voice changing its natural tone to one of chanting, "to the story of Michabo as it is told in the lodges of the Powhatans, the Delawares and of those tribes who dwell far away beyond our forests, away where abideth the West Wind and where the Sun strideth towards the darkness.

"Michabo dived down into the water when there was no land and no beast and no man or woman and he was lonely. From the bottom took he a grain of fine white sand and bore it safely in his hand in his journey upward through the dark waters. This he cast upon the waves and it sank not but floated like a tiny leaf. Then it spread out, circling round and round, wider and wider as the rings widen when thou casteth a stone into a still lake, till it had grown so large that a swift young wolf, though he ran till he dropped of old age, could not come to its ending. This earth rose all covered with trees and hills and beasts and men and women, and Michabo, the Great Hare, the Spirit of Light, the Great White One, hunted through earth's forests and he fashioned strong nets for fishing and he taught the stupid men, who knew naught, how to hunt also and to catch fish that they might not die of hunger.

"But Michabo had mightier deeds to do than the slaying of the fat deer or the netting of the salmon. His father was the mighty West Wind, Ningabiun, and he had slain his wife, the mother of Michabo. So when Michabo's grandmother had told him of the misdeeds of his father, Michabo rose up and called out to the four corners of the world: 'Now go I forth to slay the West Wind to avenge the death of my mother.'

"At last he found Ningabiun on the top of a high mountain, his cheeks puffed out and his headdress waving back and forth. At first they talked peacefully together and the West Wind told Michabo that only one thing in all the world could bring harm to him, and that was the black rock.

"'Wert thou the cause of my mother's death?' questioned Michabo, his eyes flashing, and Ningabiun calmly answered 'Yes.'

"So Michabo in his fury picked up a piece of black rock and struck at Ningabiun with all his might. A terrible conflict was this, such as hath never been seen since; the earth shook and the lightnings flashed down the sides of the mountain. So great was Michabo's strength that the West Wind was driven backwards. Over mountains and lakes Michabo drove him and across wide rivers, till they two came to the very brink of the world. Ningabiun feared that his son was going to push him off and cried out:

"Hold, my son, thou knowest not my power and that it is impossible to kill me. Desist and I will portion out to thee as much power as I have given to thy brothers. The four quarters of the globe are theirs, but thou canst do more than they, if thou wilt help the people of the earth. Go and do good, and thy fame will last forever.'

"So Michabo ceased from the battle and went down to help our fathers in the hunt and in the council and in the prayer-lodge; but to this day great cliffs of black rock show where Michabo strove with his father, the West Wind."

Nautauquas, son of Powhatan, was returning at night through the forest towards his lodge at Werowocomoco. Over his shoulder hung the deer he had gone forth to slay. His mother had said to him:

"Thy leggings are old and worn, and thou knowest that good luck cometh to the hunter wearing moccasins and leggings made from skins of his own slaying. Go thou forth and kill a deer that I may soften its hide and make a covering of it for thy feet."

So Nautauquas had taken his bow and a quiver of arrows, and while Pocahontas and Cleopatra were sporting at the waterfall he had sought a pond whose surface was all but covered with fragrant water lilies, and he had hidden behind a sumac, bush, waiting patiently till a buck came down alone to drink. Only one arrow did he spend, which found its place between the wide branched antlers; then the hunter had waded into the pond, pushing aside the lily pads, and with one cut of his knife he had put an end to the struggling deer. Now he was bearing it home and he thought with eagerness of the savory meat it would yield him on the morrow. There was no doubt that he would have appetite ready for it, as all day long he had eaten nothing. It had been easy enough for him to have killed a squirrel and roasted it, but Nautauquas, knowing it was part of a brave's training to accustom himself to hunger, often fasted a long time voluntarily.

The night was a dark one, but now that the moon had risen, long vistas of light shone down the forest avenues, generally at that time so free from underbrush. Nautauquas, looking up through the branches at the moon, thought how it was the squaw of the sun and remembered the queer tales the old women were fond of relating about it.

Suddenly before him he saw a creature dancing down the moon-path, whirling and springing about while a pair of rabbits, that were startled in crossing the path, scurried off into a clump of sassafras bushes nearby. Then, as if reassured, they sat there calmly, even when the dancing figure came closer to them. And Nautauquas heard singing, though the words of the song did not come to his ears. He slipped behind an oak tree and watched the dancer advance. Now that it was nearer he discovered that it was a young girl; her only garment, a skirt of white buckskin, napped against her firm bare brown legs and a necklace of white shells clicked as she spun about. In the branches above some squirrels, awakened from their slumber, straightened their furry tails and began to chatter and a screech-owl tuwitted and tuwhoed. There was something familiar in the outlines, and Nautauquas was therefore not completely astonished when, turning about, she showed the face of Pocahontas.

"Matoaka," he cried, stepping from the shadow; "what dost thou here alone at night?"

His sister did not scream nor jump at this sudden interruption. She seized her brother's hand and pressed it gently.

"It was such a beautiful night, Nautauquas," she replied, "that I could not lie sleeping in the lodge. I come often here."

"And hast thou no fear, little sister?" he asked affectionately; "no fear of wild animals or of our enemies?"

"Wild animals will not hurt me. I patted a mother bear with cubs one night, and she did not even growl."

Nautauquas did not doubt her word. He knew that there were certain human beings whom beasts will not hurt.

"And enemies," she continued, "would not venture so near the village of the mighty Powhatan."

"I heard thee singing, little White Feather; what was thy song?"

"I made it many moons ago," she answered, "and I sing it always when I dance here at night. Listen then, thou shalt hear the song Matoaka, daughter of Powhatan, made to sing in the woods by Werowocomoco."

And she danced slowly, imitating with head and hands, body and feet, the words of her song.

When she had finished she threw herself down at his feet, asking:

"Dost thou like my song, my brother?"

"Yes, it is a new song, Matoaka, and some day thou must sing it for our father. But it seemeth to me that thou art different from other maids. They do not care to rise from their sleeping mats and go forth alone into the forest."

"Perhaps they have not an arrow inside of them as have I."

Nautauquas had seated himself in the crotch of a dogwood-tree and looked with interest at his sister below him.

"An arrow?" he queried; "what dost thou mean?"

"I think," she answered, speaking slowly, "that within me is an arrow—not of wood and stone, but one of manitou—how shall I explain it to thee? I must go forth to distances, to deeds. I am shot forward by some bow and I may not hang idle in a quiver. I know," she continued, fingering the quiver on his back, "how thine own arrow feels after thou hast fashioned it carefully of strong wood and bound its head upon it with thongs. It says to itself; 'I am happy here, hanging in my warm bed on Nautauquas's back.' And then when thou takest it in thy hand and fittest its notch to the bowstring, it crieth out: 'Now I shall speed forth; now shall I cut the wind; now shall I journey where no arrow ever journeyed before; now shall I achieve what I was fashioned for!'"

"Strange thoughts are these, little sister, for a maid to think," and Nautauquas stroked the long braid against his knee.

"I am so happy, Nautauquas," she went on. "I love the warm lodge, the fire embers in the centre, the smoke curling up towards the stars I can see through the opening above me. I love to feel little Cleopatra's feet touching my head as we lie there together. But then I feel the arrow within me and I rise to my feet silently and creep out, and if the dogs hear me I whisper to them and they lie down quietly again. I love Werowocomoco, yet I long too to go beyond the village to where the sky touches the earth. I love the tales of the beasts the old squaws tell, but I want to hear the braves when they speak of war and ambushes. Springtime and the sowing of the corn are full of delight, yet I look forward eagerly to the earing of the corn and the fall of the leaf."

The maiden spoke passionately. So had she never spoken to anyone. She ceased for a moment and there was no sound save the call of the owl. Then she turned around and knelt, her elbows on her brother's knees, and asked:

"Tell me, Nautauquas, tell me the truth, since thou canst speak naught else; what manitou is in me that I am like to rushing water, to a stream that hurries forward? What shall I become?"

"Something great, Matoaka," he answered; "I know not whether a warrior—such there have been—a princess who shall hold many tribes in her hand, or a prophetess; but I am certain that the arrow of thy manitou shall bring down some fair game."

"Ah!" she breathed deeply. "I thank thee for thy words, Nautauquas, my brother, and that thou hast not made sport of me."

"Why should anyone make sport of thee? It is not strange that the aspen should quiver when the wind blows, nor that thou shouldst be swayed by the spirit that is within thee, Matoaka. Some day—"

He was interrupted by a piercing scream from the depth of the forest. He sprang to his feet; all the dreaminess of his attitude and mood had vanished; he pulled an arrow from his quiver fitted it to the string in readiness to shoot. Was it possible, he wondered, for any war party of their enemies to have ventured so near Powhatan's stronghold without having been halted at other villages belonging to his people? Pocahontas too was on her feet, her head on one side, listening intently.

Again came the scream, then Nautauquas loosened his bow, saying:

"That is no human cry. It is a wildcat in agony. Let us go and see what aileth it."

They ran swiftly towards the point from which the sound had come. Again came the cry to guide them, and then there was silence as they ran through the moonlight checkered by the shadows of the trees.

Nautauquas stood still suddenly, so suddenly that Pocahontas behind him could not stop quickly enough and fell against him and almost down into a ravine that lay beneath, but Nautauquas caught her on the very brink.

"It is down there," he pointed; "there must be a trap, I think. Let us descend very carefully."

They clambered down through the darkness made by the overhanging bushes and rocks. At the bottom the light was not obscured, and they beheld the striped body of a large wildcat caught in a trap.

"Look," cried Pocahontas excitedly, "there is another beast just there in those bushes. Our coming must have frightened it. He has been trying to kill the one in the trap, that cannot defend himself."

"That is so," assented Nautauquas, making ready to shoot the beast that was at liberty in case it should spring towards them. But the animal evidently had no taste that night for an encounter with human beings, and slouched off and up the side of the ravine. The imprisoned animal, they could see, was bleeding from a large wound on its back, and in the moonlight its eyes shone like fire.

"Poor beast!" exclaimed Nautauquas compassionately. "I would free him if he would let me touch him. As it is he will have to starve to death unless his enemy comes back to finish him."

"No," said Pocahontas, "that need not be. I will loose him and bind up his wound if thou wilt cut a strip off thy leggings."

"Silly child," he laughed. "A wild beast needs no balsam nor cloths for his wounds. If he were free to drag himself to safety he would lick his hurt till it healed. But he would bite thy hand off shouldst thou attempt to touch him."

"Nay, Nautauquas, he would not harm me. See how quiet he will grow."

She knelt down just beyond the reach of the wildcat and began to whisper to it. Nautauquas could not make out what she said, but to his amazement he beheld how the beast ceased to lash its tail and how its muscles seemed to relax. Nevertheless the young brave caught Pocahontas by the arm and tried to pull her away.

"There is no danger, my brother," she remonstrated. "Fear not. Hast thou not seen old Father Noughmass when the bees swarm over his neck and hands? They never sting him. He cannot tell thee why, nor do I know why wild beasts will not harm me."

So Nautauquas, knife in hand and breathing deeply, looked on while Pocahontas, speaking words in a low voice, moved nearer and nearer the wildcat. Taking her knife from her girdle, she began to cut through the thongs that held him. One paw was now loose and yet the beast did not move to touch his rescuer. Then when the other thongs were loose and it was free, it moved off slowly and painfully into the woods as if no human beings were there.

Nautauquas breathed a sigh of relief.

"It is wonderful, Matoaka, yet I pray thee test thy strange power not too far. I am glad though the poor beast got away. I like not to see them suffer. I shoot and kill for food and for skins, but I kill at once."

They now climbed up the ravine again and started off in the direction of Werowocomoco.

The night was already far advanced and Pocahontas was growing drowsier and drowsier. Nautauquas, seeing that she was almost asleep, took hold of her arm and made her lean on him. As they approached the spot where he had first come across her dancing, they noticed a human figure crouched on the ground. Even in the moonlight, grown dimmer as dawn approached, he could see that it was an old squaw. Pocahontas recognized old Wansutis, a gatherer of herbs and roots.

"What dost thou here, Wansutis?" she questioned.

"He! the little princess," cried the old woman, scowling up at them, "and the young brave Nautauquas. I seek roots and leaves by the light of the Sun's squaw. So is it meet for me and so will the drinks be stronger when brewed by old Wansutis. I have found many rare plants this night; it hath been a lucky one, perchance because the young princess was also abroad in the forest."

All the children of the tribe were afraid of the old woman. They told each other tales of how she could turn those she disliked into dogs, bats or turtles. And now even Nautauquas remembered how he had run from her when he was a little fellow. Her expression was so ugly and so malign that Pocahontas, though she did not fear her exactly, had no desire to stay longer, and so started forward.

"And what doth Pocahontas in the woods at night?" asked Wansutis. "Knoweth The Powhatan that she hath left his lodge?"

Pocahontas, though she often willingly allowed those about her to forget her rank, could yet be very conscious of it when she desired. Now it did not please her to be questioned in this manner by the old squaw and she did not answer.

"Oh hey," cried Wansutis, "thou wilt not answer me. Thou art proud of thy rank and thy youth. Yet one day thou wilt be an old squaw like me, without teeth, with weak legs, and life a burden to thee. Then thou wilt not be so proud."

Pocahontas stopped and turned around again.

"Nay, I will not grow old. I will not let the day come when life shall be a burden. Thou canst not read the future, Wansutis. I shall always be as fleet as now."

"Thinketh thou to ward off old age by some of my potions made from these roots I carry here, a bundle too heavy for an ancient crone like me to bear on her back? Thou shalt have none of them."

At these words Pocahontas's manner changed. Stooping, she picked up the bundle and pressed it into the net that lay on the ground and swung it on to her strong shoulders.

"Come, Wansutis," she cried. "Seek not to anger me with words and I will bear thy bundle to thy wigwam. It is in truth too heavy for thy old bones."

The old woman grunted ungraciously as she rose to her feet, then the three, one following the other, moved forward. They were obliged to go slowly, as Wansutis could only hobble along, and Nautauquas was sorry to see that dawn was approaching. He feared now that Pocahontas would not be able to steal unobserved back to her place beside Cleopatra and that she would be scolded. They went with Wansutis to her wigwam and Pocahontas let fall her bundle. Nautauquas took out his knife and cut off a hind quarter of the deer and laid it on the squaw's hearth.

"She hath no son to hunt for her," he said in explanation as he and Pocahontas went off unthanked.

Wansutis's wigwam was on the edge of the village. As they came nearer to the lodges they heard yelling and shouting from every side, and they saw small boys and young braves rush forth, glancing eagerly about them.

"Let us hasten," cried Pocahontas. "I wonder what hath befallen, Nautauquas."

"What hath happened?" Nautauquas called out to Parahunt, his brother, when he caught up with him hastening to the river.

"Word hath come by a runner that one of the tribes from the Chickahominy villages hath fallen upon a party of Massawomekes and hath vanquished them. Even now they are approaching with the prisoners."

In passing the front of his wigwam Nautauquas threw down the carcass of the deer, then ran on to join the ever increasing crowd of braves and children on the river bank.

Pocahontas too had mingled in the throng, and so Cleopatra and the squaws in the lodge had not noticed her absence, thinking when they saw her that she had been roused from sleep in the early dawn as they had been.

It was now almost light. Far down the river six large dugouts were approaching. But even that sight was not sufficient to make the onlookers forget the fact that the sun was rising and must be greeted with the customary ceremony. Two chiefs, whose duty it was, took from their pouches handfuls of dried uppowoc (tobacco), and each turning away from the other, walked in a large half-circle, scattering the uppowoc upon the ground, until when they met a brown ring had been formed. Within this braves and squaws hurried to seat themselves. With uplifted eyes and outstretched hands they greeted the Sun who had come back to them to warm their fields and to draw their young corn upright.

By the time this morning ceremony was over the dugouts were almost at the beach. There was now a great shouting and yelling from shore to boats and from boats to shore, and Pocahontas slipped into a thicket of bushes on to a higher point of the bank where she could be alone to watch the landing. She clapped her hands as their friends, the stalwart Chickahominies, leaped ashore, twenty to each huge dugout; and though her dignity would not permit her to call out derisively, as did the crowd, to the three prisoners each boat contained, she looked eagerly to see what kind of monsters these enemies of her tribe might be.

The eighteen Massawomekes were not bound; they stepped from the dugouts as firmly as if they were going to a feast instead of to torture. They were of the Iroquois nation; and Pocahontas, who had heard many stories of this race, always at enmity with her own, noticed certain differences in the way they were tattooed and in the shape of their headdresses.

Victors and prisoners, followed by the crowd, marched forward to the ceremonial lodge where The Powhatan was awaiting them. Pocahontas slipped into the already crowded space, though one of Powhatan's squaws tried to stay her. She made her way without further opposition between Chickahominies and Massawomekes, up to the dais where her father sat, and crouched down on a mat spread on raised hurdles at his feet, where she could observe all that went on.

One of the Chickahominy chiefs, whose face she remembered to have seen at the great autumn festivals, was the first to speak:

"Powhatan, ruler of two hundred villages and lord of thirty tribes, who rulest from the salt water to the western forests, we come to tell thee how we have pursued thine enemies, the Massawomekes, who two months ago did slay in ambush a party of our young men out hunting deer. By the Great Swamp (the Dismal Swamp of Virginia) we came upon them, and though they sought like bears to hide themselves in its secret places, lo! I, Water Snake, did track them and I and my braves fell upon them, and now they are no more."

Murmurs of assent and of approval were heard throughout the lodge. The prisoners alone were apparently as unconscious of Water Snake's recital as if they were still hidden in the fastnesses of the Great Swamp.

"There where we fought," continued the orator, waving his hand towards the southwest, "the white blossoms of the creeping plants turned crimson, and the hungry buzzards circled overhead. Many a Massawomeke squaw sits to-night in a lonely wigwam; many a man child among them hath lost the father to teach him how to bend a bow. We slew them all, Great Werowance, all but these captives we have brought before thee."

This time louder shouts of approval rewarded Water Snake's speech, which did not cease until it was seen that Powhatan meant to acknowledge it. He did not rise nor change his position in any way, and his voice was low and measured.

"A tree hath many branches, but one trunk only. Deep into the earth stretch its roots to suck up nourishment for every twig and leaf. I, Wahunsunakuk, Chief of the Powhatans and many tribes, am the trunk, and one of my many branches is that of the Chickahominies and one that is very close to my heart. My children have done well and the Powhatan thanks them for their brave deeds. Now can your young braves go forth upon the hunt unharmed and bring back meat for feastings and hides for their squaws to fashion."

He paused and all the eyes of his people in the lodge were bent on him with the same question.

"My children ask of me 'What shall we do with these captives?' and I make answer, feast them first, that they may not say that the Powhatans are greedy and give not to strangers. Then when they have feasted let them run the gauntlet."

He waved his hand in token that he had finished speaking, and the glad news was shouted from the lodge to the eager crowd without. Pocahontas knew as well as if she could see them that the squaws were hurrying about to prepare the food, and from her low seat she could see between the legs of the braves before her how a number of boys were lying on their stomachs, trying to wriggle into the lodge that they might hear for themselves the interesting things going on and observe for themselves whether the captives showed any sign of fear.

Now Powhatan gave an order and all seated themselves on the ground or on mats in lines facing him. Then in came the squaws bearing large wooden and grass-woven dishes of food. There were hot cakes of maize and wild turkeys and fat raccoons. The captives were served first and none of them refused. They would not let their enemies believe that fear of their coming fate could spoil their appetites. So, after throwing the first piece of meat into the fire as an offering to Okee, they ate eagerly.

One of them who sat nearest the front, Pocahontas noticed, was but little older than herself. He was too young to be a brave; perhaps, she thought, he had run off from home and had followed the war party, as she had heard of boys in her own tribe doing. She wondered if now he was regretting that his eagerness for adventure had made his first warpath his last one.

When they had feasted the squaws passed around bunches of turkey feathers for them to wipe their greasy fingers on, and in every way the captives were treated with that exaggerated courtesy that was customary towards those about to be tortured.

Then Powhatan rose, and, preceded and followed by several of his fifty armed guards chosen from the tallest men of his thirty tribes, he strode down the centre of the lodge and out into the sunshine. Pocahontas walked next behind him, and once outside, ran to tell the curious Cleopatra all she had witnessed.

"Why shouldst thou have seen it all?" asked her jealous sister of Pocahontas, "while I had naught of it all but the shouting?"

"Because," laughed Pocahontas, pulling her sister's long hair, "because my two feet took me in. Thine are too fearful, little mouse."

An open space stretched before the ceremonial lodge, used for games and feats of running and shooting at a mark. Now Powhatan and his guard and his sons seated themselves upon the firm red ground that rose in a little hillock to a height of several feet at one side of the lodge. Then other chieftains took up their places behind them, standing or sitting; the squaws crowded in among them and the boys sought the branches of a single walnut-tree, the only tree within the limits of Werowocomoco. They looked with longing eyes at the slanting roof of the great lodge. That was undoubtedly the point of vantage, but The Powhatan was a much dreaded werowance and they dared not risk his ire.

Pocahontas, who had been wondering where to bestow herself, noticed the envying glances they cast in its direction. She was not withheld by their restraining fear, so running to the opposite side of the lodge, she climbed its sides, finding foothold in its bark covering, and soon was curled up comfortably, her hands about her knees, where she would miss nothing of the spectacle.

Now she beheld two long rows of young braves, one of them composed of Powhatans, the other of Chickahominies, stride down the open space below her and form a lane of naked, painted human walls. In their hands they held bunches of fresh green reeds, sharp as knives, or heavy bludgeons of oak, or stone tomahawks. For a moment they stood there motionless as if they were merely spectators of some drama to be enacted by others.

Pocahontas recognized most of them: Black Arrow, whose ear had been clawed off by a bear; Leaping Sturgeon, who had hung two scalps at his girdle before the chiefs had pronounced him old enough to be a brave; her own cousin, White Owl, the most wonderfully tattooed of them all; and the Nansamond young chieftain who wore a live snake as an earring in the slit of his ear.

Then Powhatan gave the signal and the captives were led forward. They knew what awaited them; probably each of them, except the young boy, had himself meted out the same fate to others that was now to befall them. They did not repine; it was the fortune of war. Singing songs of triumph, of derision of all their enemies, they started to run down the awful lane of death. Blows rained upon them, on neck, on head, on arms, even on their legs from stooping adversaries. So swift came the blows from both sides that sometimes two fell upon the same spot almost at once.

Pocahontas marked with interest that the boy was last of the line, and that he bore himself as bravely as the others.

When they reached the end of the row there was no escape—no escape anywhere more for them. Back they darted, so swiftly that it seemed as if each escaped the blow aimed at himself, only to receive the one meant for his comrade ahead.

Pocahontas had a queer feeling as she looked down on them and saw the blood spurting from a hundred wounds. She thought perhaps it was the hot sun that made her feel a little sick. Her eyes followed the boy and as he came nearer she noticed that he was almost at the end of his strength. A few more blows would finish him. Already some of his elders had fallen to the ground, and if, when beaten unmercifully, they were still unable to rise, the tomahawk dashed out their brains.

To her astonishment, Pocahontas found herself wishing the boy might not fall, might escape in some miraculous manner. What a wrong thought! she said to herself: was he not an enemy of her tribe? Yet she could not help closing her eyes when she saw Black Arrow aiming a terrible blow at his head. She did not know what to make of herself. She suddenly began to think of the hurt wild-cat she and Nautauquas had pitied during the night. But no one ought ever to pity an enemy. What was she made of?

As she opened her eyes again she heard a woman's outcry and beheld a squaw rushing towards the end of the line where Black Arrow's blow had felled the boy. It was old Wansutis.

"I claim the boy," she panted; "I claim him by our ancient right. Cease, braves, and let me have him."

The astounded braves let their arms drop at their sides, and the panting, bleeding captives who had not already fallen, breathed for a moment long breaths.

"I claim the boy," the old woman cried again in a loud voice, turning towards Powhatan, "to adopt as a son. Many popanows (winters) and seed times have passed since my sons were slain. Now is Wansutis old and feeble and hath need of a young son to hunt for her. By our ancient custom this captive is mine."

There was an outcry of opposition from the younger braves at being robbed of one of their victims, but the older chiefs on the hill debated for a few moments, and then gave their decision: there was no doubt of the old woman's right to claim the boy. So Powhatan sent two of his guards to fetch him and to carry him to Wansutis's lodge.

Pocahontas suddenly felt at ease again. Yes, she couldn't help it, she said to herself, but she was glad the boy had not been beaten to pieces. As soon as he was carried off the running of the gauntlet began again. But Pocahontas had now had enough of it. It would continue, she knew, until all of the captives were dead. She slid down from the back of the lodge and led by curiosity, set off for Wansutis's wigwam. It was at the edge of the village, and before the slow procession of the two guards, the old woman and the boy had arrived, Pocahontas had hidden herself behind a mossy rock, from which hiding place she had a view right into the opening of the wigwam.

She watched the guards lay the unconscious boy gently down and Wansutis as she knelt and blew upon the embers under the smoke hole till they blazed up. Then she saw the old woman take a pot of water and heat it and throw herbs into it. With this infusion she bathed the wounds, anointing them afterwards with oil made from acorns. And while she worked she prayed, invoking Okee to heal her son, to make him strong that he might care for her old age.

Pocahontas was so eager to know whether the boy were alive that she crept closer to the wigwam, and when at last he opened his eyes they looked beyond the hearth and the crouching Wansutis, straight into those of Pocahontas. She saw that he had regained his senses, so she put her fingers to her lips. She did not want Wansutis to know that she had been watched. Already the touch of the wrinkled fingers was as tender as that of a mother, and Pocahontas felt sure that she would resent any intrusion. Now that she had seen all there was to see, she stole away.

After wandering through the woods to gather honeysuckle to make a wreath, she returned to the village. There was no longer a crowd in the open space; the captives were all dead and the spectators had gone to their various lodges. Only a number of boys were playing run the gauntlet, some with willow twigs beating those chosen by lot to run between them. A girl, imitating old Wansutis, rushed forward and claimed one of the runners for a son.

A few days later when the young Massawomeke lad had recovered there were ceremonies to celebrate his adoption as a member of the Powhatan tribe, of the great nation of the Algonquins. The other boys of his age looked up to him with envy. Had he not proved his valor on the warpath and under torture while they were only gaming with plumpits? They followed him about, eager to do his bidding, each trying to outdo his comrades in sports when his eye was on them. And all the elders had good words to say about Claw-of-the-Eagle, and Wansutis was so proud that she now often forgot to speak evil medicine.

Pocahontas wondered how Claw-of-the-Eagle liked his new life, and one day when she was running through the forest she came upon him. He had knelt to look through a thicket at a flock of turkeys he meant to shoot into, but his bow lay idle beside his feet, and she saw that his eyes seemed to be looking at something in the distance.

"What dost thou behold, son of Wansutis?" she asked.

He started but did not reply.

"Speak, Claw-of-the-Eagle," she said impatiently. "Powhatan's daughter is not wont to wait for a reply."

He saw that it was the same face he had beheld peering into the lodge at the moment he regained consciousness.

"I see the sinking sun. Princess of many tribes, the sun that journeys towards the mountains to the village whence I came."

"But thou art of us now," she rejoined.

"Yes, I am son of old Wansutis and I am loyal to my new mother and to my new people. And yet. Princess, I send each day a message by the sun to the lodge where they mourn Claw-of-the-Eagle. Perhaps it will reach them."

"Tell me of the mountains and of the ways of thy father's people. I long to learn of strange folk and different customs."

"Nay, Princess, I will not speak of them. Thou hast never bidden farewell to thy kindred forever. I would forget, not remember."

And Pocahontas, although it was almost the first time that any one had refused to obey her, was not angry. She was too occupied as she walked homeward wondering how it would seem if she were never to see Werowocomoco and her own people again.

Opechanchanough, brother of Wahunsunakuk, The Powhatan, had sent to Werowocomoco a boat full of the finest deep sea oysters and crabs. The great werowance had returned his thanks to his brother and the bearers of his gifts were just leaving when Pocahontas rushed in to her father's lodge half breathless with eagerness.

"Father," she cried, "I pray thee grant me this pleasure. It hath grown warm, and I and my maidens long for the cool air that abideth by the salty water. Therefore, I beseech thee, let us go to mine uncle for a few days' visit."

Powhatan did not answer at once. He did not like to have his favorite child leave him. But she, seeing that he was undecided, began to plead, to whisper in his ears words of affection and to stroke his hair till he gave his consent. Then Pocahontas ran off to get her long mantle and her finest string of beads and to summon the maidens who were to accompany her. They embarked in the dugout with her uncle's people and were rowed swiftly down the river.

At Kecoughtan they were received with much ceremony, for Pocahontas knew what was due her and how, when it was necessary, to put aside her childish manner for one more dignified. Opechanchanough greeted her kindly.

"Hast thou forgiven me, my uncle?" she asked as they sat down to a feast of the delicious little fish she always begged for when she visited him, and to steaks of bear meat; "hast thou forgiven the arrow I shot at thee last popanow?"

"I will remember naught unpleasant against thee, little kinswoman," he replied as he drank his cup of walnut milk.

"Indeed I am ashamed of my foolishness," continued his niece. "I was but a child then."

"And now?—it is but a few moons ago."

"But see how I grow, as the maize after a rain storm. Soon they will say I am ready for suitors."

"And whom wilt thou choose, Pocahontas?"

"I do not know. I have no thoughts for that yet."

"What then are thy thoughts of?"

"Of everything, of flowers and beasts, dancing and playing, of wars and ceremonies, of the new son of old Wansutis, of Nautauquas's new bow, of necklaces and earrings, of old stories and new songs—and of to-morrow's bathing."

"Fear not that thou hast yet left thy childhood behind thee," said her uncle.

Then when the fire died down and the storyteller's voice had grown drowsy, Pocahontas fell asleep, her arm resting on a baby bear that had been taken away from its dead mother and that would cuddle close to the person who lay nearest the fire.

Opechanchanough had not the same deep affection for children as that which Powhatan showed to his sons and daughters. He was as brave a fighter but not as great a leader in peace as Wahunsunakuk. It irked him that he had to give way to his brother and that he must obey his commands; yet he knew that only by unity between the different tribes of the seacoast could they be safe from their common enemies, the Iroquois. His vanity was very great and he had felt hurt at the ridicule which Pocahontas had caused to fall upon him. Had she come on her visit sooner he had surely not received her so kindly. But now there were other strange happenings and more important matters to consider, and he was too wise a chief to worry long over a child's pranks. Besides, he had learned, from his own observance and from the tongues of others, how his brother cherished her more than any of his squaws or children. So policy as well as his native hospitality dictated a kindly reception.

In the morning after they had eaten, Opechanchanough offered to send Pocahontas and her maidens in a canoe down to where a cape jutted out into the ocean that they might see the breakers at their highest, but Pocahontas declined.

"Nay, Uncle," she said, "but my maidens have never seen the sea. They be stay-at-homes and I would not affright them too sorely by the sight of mountains of water. Have no care for us save to bid some one supply us with food to take along. I know the way down to a smooth beach where we can disport ourselves."

So Opechanchanough, relieved to have them off his hands, let her have her will.

The town was within a mile of open water, and the maidens started off with a large supply of dried flesh slung in osier baskets on their backs. Some of the young braves looked after them as they went and disputed as to which of them they would like to choose as squaw when they were older.

Pocahontas led the way through wild rose bushes and sumac, with here and there an occasional tall pine tree, its lowest branches high above their heads. They were all of them in the gayest humor: it was a day made for pleasure, and they had not a care in the world. They sang as they walked and joked each other, Pocahontas herself not escaping.

"Did the bear, thy bedfellow, scratch thee?" asked one, "and didst thou outdo him, for this morning he was not to be found near the lodge."

"Perhaps," suggested another, "it was not a real bear cub but some evil manitou."

The maidens shuddered deliciously at this possibility.

"Nonsense," called back Pocahontas, "he was real enough; here is the mark of one claw on my foot. Besides, I do not believe the evil manitou can have such power on such a beautiful day as this. Okee must have bid them fly away."

Now suddenly the path turned and before them shone the silver mirror of the sea.

"Behold!" cried Pocahontas, and then Red Wing, her nearest companion, fell flat upon the ground, burying her face in the sand. The others stood and stared at the new watery world in front of them, hushed in an awed silence. Gradually their curiosity got the better of their fear and they began to question:

"How many leagues does it stretch, Pocahontas?"—"Can war canoes find their way on it?"—"Come the good oysters from its depths?" asked Deer-Eye, whose appetite was always made fun of.

Pocahontas answered as well as she was able, but to her who had seen several times before the great water, it was almost as much of a mystery as to her comrades. But to-day she greeted it as an old friend. She could scarcely wait to throw herself into the little rippling waves at her feet.

"Come on," she cried, "let us hasten. How wonderful to our heated bodies will its freshness be." And as she ran towards it she threw off her skirt, her moccasins and her necklace and dashed into the sea.

Though her companions were used to swimming from the day their mothers had thrown them as babies into the river to harden them, they had never been where there were not protecting banks on each side of them, and they were afraid to follow Pocahontas into this unknown. But gradually her evident safety and delight were too much for their caution, and they were soon at home in the gentle waves.

For nearly an hour they played their water games, chasing and ducking each other, racing and swimming underneath the surface. Then they grew hungry and bethought themselves of their food waiting to be cooked. But when they were on the shore again and about to start a fire to heat their meat, Pocahontas bade them wait.

"Here," she said, "is fresher food. See what the tide has left for us."

To their great astonishment the maidens, who did not know the sea retreated, saw how while they were bathing the water had bared the sand, leaving it full of little pools. Standing in one of them, Pocahontas stooped down and ran her hand through the mud, bringing up a soft-shelled crab.

"See," she cried, "there are hundreds of them for our dinner, but be careful to hold them just so, that they may not nip you."

And her maidens, laughing and shrieking, soon had a larger supply of crabs than they could eat. They found bits of wood on the beach and dried sea weed which they set on fire by twirling a pointed stick in a wooden groove they had brought along with their food. After they had eaten, they stretched out lazily on the sand and talked until they began to doze off, one by one.

Pocahontas had strolled a little further down the beach, picking up the fine thin shells of transparent gold and silver which she liked to make into necklaces. She had found a number of them and as they were more than she could hold in her hands, she sat down to string them on a piece of eel grass until she could transfer them to a thread of sinew. When she had finished she lay back against a ridge of sand and watched the gulls as they flew above her, dipping down into the waves every now and then to bring up a fish. Far away a school of porpoises was circling the waves, their black fins sinking out of sight and reappearing as regularly as if they moved to some marine music. Pocahontas wondered whence they came and whither they and the gulls were bound. How delightful it was to move so rapidly and so easily through water or air. But she did not think of envying them. Was she not as fleet as they in her element? She pressed her hand against the warm sand how she loved the feel of it; she stretched her naked foot to where the little waves could wet it. How she loved the lapping of the water! Within her was a welling up of feeling, a love for all things living.

It was a very quiet world just now; the sun was only a little over the zenith. Only the cries of the sea gulls and the soft swish of the waves broke the silence. It would be pleasant to sleep here as her comrades were sleeping, but if she slept then she would miss the consciousness of her enjoyment.

Yet, though she intended to keep awake, when she looked seaward, she felt sure that she must have fallen asleep and was dreaming the strangest of dreams. For nowhere save in dreamland had anyone ever beheld such a sight as seemed to stand out against the horizon. Three great birds, that some shaman had doubtless created with powerful medicine, so large that they almost touched the heavens, were skimming the waves, their white wings blown forward. One, much larger than the others, moved more swiftly than they.

Yet never, in a dream or in life, were such birds, and little Pocahontas, who had sprung to her feet, stood gaping in terrified wonder.

"Then must I be bewitched!" she cried aloud; "some evil medicine hath befallen me."

She called out, and there was a tone in her voice that roused the sleeping maidens as a war drum roused their fathers.

"What see ye?" she asked anxiously.

"Oh! Pocahontas, we know not," they answered in terror, huddling about her; "answer thou us. What are those strange things that speed over the waves? Whence come they—from the rim of the world?"

Pocahontas, the fearless, was frightened. She gave one more glance seaward, and then turning, took to her heels in terror. Her maidens, who had never seen her thus, added her fright to they own, and none stopped until they had reached the lodge at Kecoughtan.

The squaws rushed out when they caught sight of the frightened children and tried to soothe them, but they could get no explanation of what had startled them. Finally Opechanchanough strode out, and when Pocahontas had tried to tell him what she had seen his face grew stern.