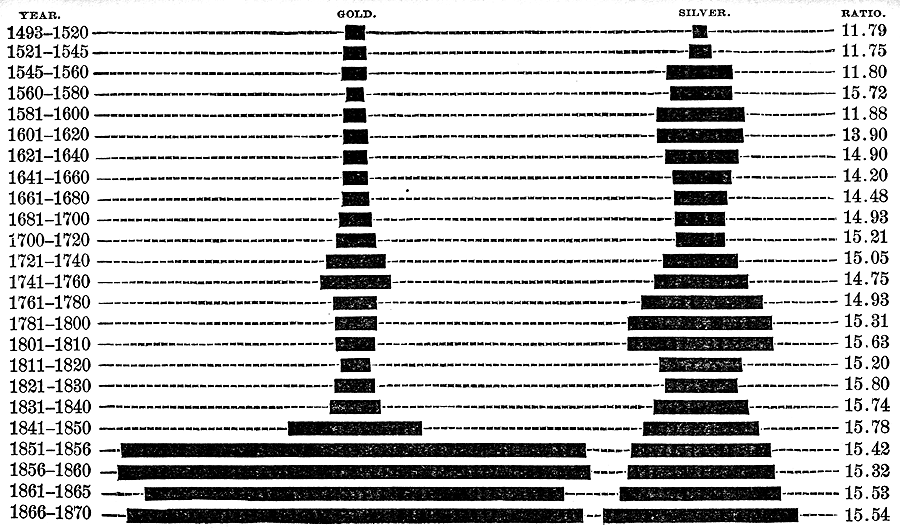

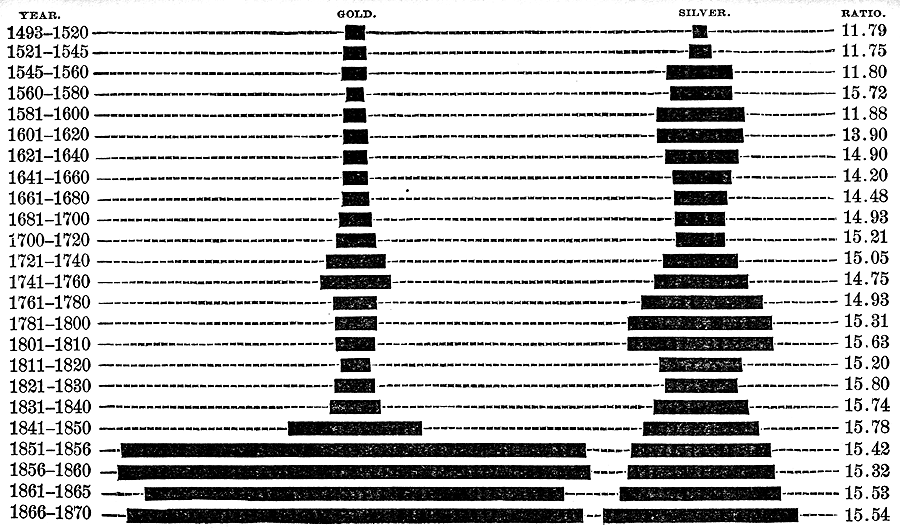

The above diagram shows the relative annual production of gold and silver from 1493 to 1870, and also average ratio of values of the two metals.

Title: If Not Silver, What?

Author: John W. Bookwalter

Release date: July 17, 2005 [eBook #16320]

Most recently updated: December 12, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bill Tozier, Barbara Tozier and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

“If you will show me a system which gives absolute permanence, I will take it in preference to any other. But of all conceivable systems of currency, that system is assuredly the worst which gives you a standard steadily, continuously, indefinitely appreciating, and which, by that very fact, throws a burden upon every man of enterprise, upon every man who desires to promote the agricultural or the industrial resources of the country, and benefits no human being whatever but the owner of fixed debts in gold.”—Speech of the Right Hon. A. J. Balfour, at Manchester, England, October 27, 1892.

As a manufacturer and somewhat extensive land owner I have a great personal interest in the money question. As a traveller I have studied the situation in other nations, and thus, I may modestly say, have enjoyed the great advantage of getting a view in no wise disturbed by partisan politics. As one whose prosperity depends almost entirely upon that of the farmers, I have naturally thought most of the effect monometallism has had, and will continue to have, upon them. I have, in a sense, been compelled to think much on this great issue. These facts are my apology, if any apology is needed, for giving my thoughts to the public. But is any apology needed? Providence has granted to a few the leisure and the opportunity to study these economic problems, on the correct solution of which the welfare of millions, whose toil leaves them little leisure for study, depends. Is it not the supreme moral duty of those few to give their conclusions to the public? I have always thought so, and in that spirit I present this little work, and ask the laboring producers to give a candid consideration to the views herein presented. It may be that some of these views will be successfully controverted, but the duty remains the same. If they should aid in arriving at a correct solution of the great problem, though the solution be different from that I have indicated, I shall be many times repaid for my labor.

John W. Bookwalter.

Springfield, Ohio, August 5, 1896.

Silver is too bulky for use in large sums.

That objection is obsolete. We do not now carry coin; we carry its paper representatives, those issued by government being absolutely secured. This combines all the advantage of coin, bank paper, and the proposed fiat money. A silver certificate for $500 weighs less than a gold dollar. In that denomination the Jay Gould estate could be carried by one man.

But silver certificates would not remain at par.

At par with what? Everything in the universe is at par with itself. The volume of certificates issued by the government would be exactly the amount of the metal deposited, and that amount could never be suddenly increased or diminished, for the product of the mines in any one year is very seldom more than three per cent. of the stock already on hand, and half of that is used in the arts. It is self-evident, therefore, that such certificates would be many times more stable in value than any form of bank paper yet devised.

Gold would go out of circulation.

It has already gone out. Under the present policy of the government we have all the disadvantages of both systems and the advantages of neither, with the added element of chronic uncertainty and an artificial scare gotten up for political purposes.

And that very scare shows an important fact which you silverites ought to heed—that nearly all the bankers and heavy moneyed men are opposed to free coinage.

Nearly all the slaveholders were opposed to emancipation. All the landlords in Great Britain were opposed to the abolition of the Corn Laws, and all the silversmiths of Ephesus were violently opposed to the “agitation” started by St. Paul. And what of it? The silversmiths were honest enough to admit the cause of their opposition (Acts xix. 24, 28), but these fellows are not. The Ephesians got up a riot; these fellows get up panics. “Have ye not read that when the devil goeth out of a man then it teareth him?”

But are not bankers and other men who handle money as a business better qualified than other people to judge of the proper metal?

Certainly not. On the contrary, they are for many reasons much less competent, as experience has repeatedly shown. All students of social science know, indeed all close observers know, that those who do the routine work in any vocation seldom form comprehensive views of it, and those who manage the details of a business are very rarely indeed able to master the higher philosophy thereof. This is a general truth applicable to all vocations except those, like law, in which a mastery of the science is a necessity for conducting the details. Experts in details often make the worst blunders in general management. Nearly all the inventions of perpetual motion come from practical mechanics. Nearly all the crazy designs in motors come from engineers. The educational schemes of truly colossal absurdity come mostly from teachers; all the quack nostrums and elixirs to “restore lost manhood” are invented by doctors, and nearly all the crazy religions are started by preachers.

On the other hand, three-fourths of the great inventions have been by men who did not work at the business they improved. The world’s great financiers have not been bankers. Alexander Hamilton was not a banker. Neither was Albert Gallatin, nor Robert J. Walker, nor James Guthrie, nor Salmon P. Chase. William Patterson, who founded the Bank of England, was a sailor and trader; and of the British Chancellors of the Exchequer whose names shine in history, scarcely one was a banker. One of Christ’s disciples was a banker, and the end of his scientific financiering is reported in Acts i. 18. John Law also, whose very name is a synonym for foolish financial schemes, was a banker, and a very successful one. Where was there ever a crazier scheme than the so-called “Baltimore Plan,” exclusively the work of bankers?

But as the bankers and great capitalists have no faith in it, the free coinage of silver would certainly precipitate a panic.

The gold basis has already precipitated several panics. Even in so conservative a country as England they have, since adopting monometallism, had a severe currency panic every four years, and a great industrial depression on an average once in seven years. The only reason we have not done worse is that the rapid development of the natural resources of the country saves us from the consequences of our folly. We draw on the future, and in no long time it honors our drafts. Nevertheless, in the twenty-three years since silver was demonetized we have had two grand panics, several minor currency panics, hundreds of thousands of bankruptcies with liabilities of billions, and five labor wars in which 900 persons were killed and $230,000,000 worth of property destroyed. Could a silver basis do worse?

You admit, then, that the immediate adoption of free coinage would, for a while at least, drive gold abroad?

And what then? Why do the gold men always stop with that statement and so carefully avoid inquiry into what would follow? Let us look into it. We may have in this country $500,000,000 in gold, though no one can tell where it is. Assuming that free coinage would send it all abroad, the inevitable result would be a gold inflation in Europe, which would cause a rise in prices. I observe that of late the gold organs have been denying this—denying, in fact, the quantitative principle in finance, something never denied before this discussion arose. It is too true, as some philosopher has said, that if a property interest depended on it, there would soon be plenty of able men to deny the law of gravitation. But as the men who deny it in one breath admit it in the next by assuring us that we shall soon have a great increase in the production of gold, and that prices will therefore rise, we may with confidence adhere to the established truth of political economy.

Sending our gold to Europe, then, would raise prices there, which would raise the price of our staple exports, such as wheat, meat, and cotton; the great rise in the price of these would, of course, stimulate exports, and thus aid us in maintaining a favorable balance, would restore to the farmers that income which they have lost by the decline of prices, would thus put into their hands the power to buy manufactured goods and to pay our annual interest debt to Europe by commodities instead of gold. In short, if the gold went abroad, it would necessarily be but a short time till much of it would come back to pay for our agricultural exports, and at the same time our farmers would get the benefit of higher prices by both operations. If any man doubts that an increased gold supply in Europe would increase the selling price of our farm surplus, I ask him to examine the figures for the twelve years following the discovery of gold in California, or the history of prices in the century following the discovery of America—an era described by all economists as one of inflation. Is there any reason why a like cause should not now produce like effects?

In the meantime, however, all the other nations would dump their silver upon us and we should be overloaded with it.

Where would the silver come from? The best authorities agree that there is not enough free silver in the world to even fill the place of our gold, which, you say, would be expelled. And right here is where the advocates of the gold standard contradict every well-established principle of political economy, and every lesson of experience, by declaring that the transfer of all our gold to Europe would not cheapen it there, and that free coinage would not increase the value of silver. They insist that we should still have “50-cent dollars.” Stripped of all its fine garniture of rhetoric, their proposition simply amounts to this: The sudden addition of 20 per cent. to Europe’s supply of gold would not cheapen it, and making a market here for all the free silver in the world would not raise its value; laying the burden of sustaining an enormous mass of credit currency on one metal instead of two has added nothing to the value of that metal; a thirty years’ war on the other metal was not the cause of its depreciation in terms of gold, and if the conditions were reversed, greatly increasing the demand for silver and decreasing the demand for gold, they would remain in relative values just the same. If those propositions are true, all political economy is false.

Government cannot create values, in silver or anything else.

You have seen it done fifty times if you are as old as I. During the war, government once raised the price of horses $20 per head in a single day. On a certain day the land in the Platte Valley, for perhaps one hundred miles west of Omaha, was worth preëmption price; the next day it was worth much more, and in a year three or four times as much. Government had authorized the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad, and before a single spade of earth was turned, millions of dollars in value had been added to the land. It had created a new use for the land. Value inheres in use when the thing used can be bought and sold. Whatever creates a use creates value, and a great increase in use forces an increase in value, provided that the supply does not increase equally fast; and with silver that is an impossibility. If you think government cannot add value to a metal, consider this conundrum: “What would be the present value of gold if all nations should demonetize it? It can be calculated approximately. There is on hand enough gold to supply the arts for forty years at the present rate of consumption. What, then, is the present value of a commodity of which the world has forty years’ supply on hand and all prepared for immediate use?

Take notice, also, that in the decade 1850-60 Germany, Austria, and Belgium completely demonetized gold, and Holland and Portugal partially did so, thus depriving it of its legal tender quality among 70,000,000 people, and that this added very greatly to its then depression.

Free coinage would bring us to a silver basis, and that would take us out of the list of superior nations, and put us on the grade of the low-civilization countries.

That is, I presume, we should become as dirty as the Chinese, and as unprogressive as the Central Americans, agnostics like the Japanese, and revolutionary like the Peruvians. And, by a parity of reasoning, the gold standard will make us as fanatical as the Turks, as superstitious as the Spaniards, and as hot-tempered and revengeful as the Moors. If not, why not? They all have the gold standard. You may say that this answer is foolish, and I don’t think much of it myself, but it is strictly according to Scripture (Proverbs xxv. 5). The retort is on a par with the proposition, and both are claptrap. The progress of nations and their rank in civilization depend on causes quite aside from the metal basis of their money.

We must remember that for many years after the establishment of the Mint we had in this country little or no coin in circulation except silver, and were just as much on a silver basis then as Mexico is now. Were our forefathers, then, inferior to us, or on a par with the Mexicans and Chinamen of the present day? Even down to 1840 the silver in circulation greatly exceeded the gold in amount.

By the way, where do you goldites get the figures to justify you in creating the impression on the public mind that Mexico and the Central and South American States are overloaded with silver, having a big surplus which we are in danger of having “dumped” on us? Didn’t you know that they are really suffering from a scarcity of silver? that altogether they have not a sixth of what we have? One who judged from goldite talk only, would conclude that silver is a burden in those countries, that they have to carry it about in hods. Now what are the facts?

In all the Spanish American States there are 60,000,000 people, and they have a little less than $100,000,000 in silver. Not $2 per capita! This is a startling statement, I know, but it is official, and you will find it in the last report of the Director of the Mint (1895). The South American States have but 83 cents per capita in silver, and Mexico has but $4.50. With a population nearly twice that of Great Britain, they have much less silver, and less than half of that of Germany, though having a much larger population. In fact, to give the Spanish American nations as large a silver circulation per capita as the average of England, France and Germany, they must needs have nearly $300,000,000 more, or nearly three times as much as they now have. It looks very much as if the “dump” would have to be the other way.

From these figures it would seem that the trouble, if monometallists are right in saying there is trouble there, is due not to their having too much silver, but that they do not have enough. Not having enough, they have followed the usual course of nations lacking a sufficient coin basis, and have issued a great volume of irredeemable paper money. By reference to the authority above cited, you will find that they have in circulation $560,000,000 in paper money. One fourth of all the uncovered paper in the world is in those countries, though their total population is less than that of the United States. Who will say that it will be a calamity to them to coin $200,000,000 more in silver and retire that much of their uncovered paper?,

Gold ought to be the standard metal, because, apart from its use as money, it has a fixed intrinsic value.

There is no such thing as intrinsic value. Qualities are intrinsic; value is a relation between exchangeable commodities, and, in the eternal nature of things, never can be invariable. Value is of the mind; it is the estimate placed upon a salable article by those able and willing to buy it. I have seen water sell on the Sahara at two francs a bucketful. Was that its intrinsic value? If so, what is its intrinsic value on Lake Superior?

Well, if what you say be true, there is no intrinsic value in any of the precious metals, and we cannot have an invariable standard of value at all.

No more than an invariable standard of friendship or love. Value is, in fact, a purely ideal relation. All this talk about an invariable dollar which shall be like the bushel measure or the yard stick is the merest claptrap. The fact that gold men stoop to such language goes far to prove that their contention is wrong. The argument violates the very first principle of mental philosophy, in that it applies the fixed relations of space, weight, and time to the operations of the mind. Would you say a bushel of discontent or eighteen inches of friendship? Men who compare the dollar to the pound weight or yard stick are talking just that unscientifically. Invariable value being an impossibility, and an invariable standard of value a correlative impossibility, all we can do is to select those commodities which vary the least and use them as a measure for other things; but you will not find in any economic writer that any metal is a fixed standard. And this brings me to consider that singular piece of folly which furnishes the basis of so much monometallist literature, namely, that gold is less variable in value than silver, and that one metal as a basis varies less than two. Some of our statesmen have got themselves into such a condition of mind on this point as to really believe that, while all other products of human labor are changing in value, gold alone is gifted with the great attribute of God—immutability. It is sheer blasphemy. It is conclusively proved, and by many different lines of reasoning, that silver is many times more stable in value than gold.

I never heard such a proposition in my life! How on earth can it be proved that silver, as things now stand, has not changed in value more than gold?

By the simplest of all processes. If we were in a mining country, I could easily prove it to you by the observed facts of geology, mineralogy, and metallurgy; but that is perhaps too remote and scientific, so we will take the range of prices since silver was demonetized. Of course you have seen the various tables, such as Soetbeer’s and Mulhall’s. Take their figures, or, better still, take those of the United States Statistical Abstract, and you will find the following facts demonstrated:

In February, 1873, a ten-ounce bar of uncoined silver sold in New York city for $13 in gold, or $14.82 in greenbacks. To-day the ten-ounce bar sells there for $6.90.

“Awful depreciation,” isn’t it? “Debased money,” and all that sort of thing. But hold on. Let us see how it is with other things. For prices in the first half of 1873 we will take the United States Abstract, and for present prices to-day’s issue of the New York Tribune. Wheat then was $1.40 in New York city, so our silver bar would have brought ten and four-sevenths bushels; to-day wheat is “unsteady” in the near neighborhood of 64 cents, and our silver bar would buy ten and five-sixths bushels. No. 2 red is the standard in both cases.

Going through a long list in the same manner, we find that the ten-ounce bar of uncoined silver would buy in ’73, in New York city, twenty-three and a half bushels of corn, to-day twenty-four bushels; of cotton then eighty pounds, to-day eighty-six pounds—and there is “a great speculative boom in cotton,” and has been for some time, but on the average price of this year silver would buy much more. Of rye, then about fifteen bushels (grading not well settled), to-day thirteen bushels; of bar iron then 310 pounds, to-day 460 pounds, and so on through the market. In the Central West in 1873 it would have taken ten such silver bars to buy a standard farm horse, Clydesdale or Percheron-Norman.

Will it take anymore bars to-day at $6.90 each?

There is another way to calculate the decline, and that is by taking the average farm value instead of the export or New York city price, and including all roots and garden products not exported, and this makes the showing far more favorable to silver. The Agricultural Department at Washington has recently issued a pamphlet showing the crops of every year since 1870, and the average home or farm price, together with the total for which the whole crop was sold. Send for it and contrast the prices given in it with those known to you to-day, and you will find that in rye, barley, oats, potatoes, and many other things the decline has been very much greater than is given above. In short, it takes more farm produce to buy an ounce of silver than it did in 1873, and twice as much to buy an ounce of gold. Of Ohio medium scoured wool, for instance—and that is the standard wool of the market—it would have taken in 1873 two and a half pounds to have bought an ounce of silver, while to-day it will take considerably over three pounds. The monometallists habitually talk, and have talked it so long that they believe it themselves, as if silver had become so cheap that the farmer ought to rank it with tin, lead, or spelter; but if the farmer will try the experiment he will find that it takes a good deal more of his product to buy a given amount of silver than it did in 1873.

The plain truth of the matter is that the time has come for both gold and silver to increase in purchasing power; but by reason of demonetization almost the entire increase has been concentrated in gold, leaving silver almost stationary as to commodities in general, but somewhat enhanced as to farm products. In the name of common, honesty, is it not a high-handed outrage to make the old debts of that period payable in the rapidly appreciating metal, instead of one that has merely retained its value? and is it not hypocrisy to speak of such a system as “honest money,” and affect to deplore the dishonesty of those who insist upon their right to pay in the least variable metal, which was constitutional and the unit of our money from the very start?

We certainly do want to pay our debts in honest money.

Gospel truth! And there is but one kind of perfectly honest money—that which will give the creditor an equivalent in commodities for what he could have bought with the money he loaned. Surely no honest man will pretend that gold today does that. At this point we must admit the painful truth that, in that sense, there is no perfectly honest money, that is, no money that does not change somewhat in purchasing power; and how to remedy this has been the great problem with the greatest minds among financiers—with all financiers, in fact, who are more anxious for justice than greedy of gain. But surely there should not be added to an innate variability that much greater variability due to the mischievous interference of interested parties, through the power of the government. And herein is made manifest the reckless folly of the gold men in fighting against the soundest conclusions of science and honesty, in striving for a standard of one metal allowing the greatest variation, instead of two which by varying in different directions might counteract each other.

Gold alone has varied in production in this century from $15,000,000 to $150,000,000 per year, or tenfold; but gold and silver combined have never varied more than sixfold. It is self evident, therefore, that the two combined form a much more stable mass than gold alone, and it cannot be too often repeated that the great desideratum in money, the one quality more important than all others, is stability in value, to the end that a dollar or pound or franc may command as nearly as possible the same amount of commodities when a contract is completed as when it is made. Economists dispute about almost everything else, but they are unanimous in this: That a money which changes rapidly in purchasing power is destructive of all stability and even of commercial morality. Will anybody pretend that gold has not changed rapidly in purchasing power within the last twenty years? Has not the universal experience shown that the variation has been very much greater in one metal than it ever was when the two metals were treated equally at the mint? The very least that could be asked on the score of honesty would be free coinage of both, with a proviso that debts should be paid with one-half of each. Back of all that, however, comes in the great principle of compensatory action, the variation of one metal counteracting that of the other; and from the standpoint of pure science and honesty it is greatly to be regretted that, instead of two precious metals, we have not at least five.

The market reports do indeed show an unprecedented decline in the prices of farm products, except in a few articles such as butter, eggs, and poultry, in places where increased population counteracts the tendency to greater cheapness; but this decline is due to increased invention, and the great cheapening in transportation.

How much of it? The records of the Patent Office show, and the experience of farmers confirms it, that all the improvements in farm machinery since 1870 have not reduced the labor cost of farm produce on the general average more than 2½ per cent. Here is a little paradox for you to study. In the twenty-five years from 1845 to 1870 the progress of invention in farm machinery was greater than in all the previous history of the world, marvellously rapid, in fact, and during those years the farm price of the produce steadily increased; but in the ensuing twenty-five years to 1895 there were very few improvements, and the price has declined with steadily increasing speed. This fact is either ignorantly or skilfully evaded by Edward Atkinson and David A. Wells in their elaborate articles on the subject; so I will present some facts and figures which were obtained early this year in the Patent Office, and carefully verified by members of Congress from every portion of the farming regions.

Since 1795 there have been granted 6,700 patents for plows, but since 1870 there have been but three really valuable improvements. Farmers are divided in opinion as to whether the riding plow reduces the labor cost. The lister, recently patented, throws the earth into a ridge and enables the farmer to plant without previously breaking the soil. It is valuable in the dry regions of the West, but useless where the rainfall is great, as the soil must there be broken up anyhow. There have been 920 corn gatherers patented, of which only one is considered a success, and most farmers reject it on account of the waste. The general verdict is that the labor of producing corn has been reduced very little, if any. In the labor of producing potatoes there has been no reduction whatever, nor in the finer garden products, nor in fruits. It takes the same labor to produce a fat hog or a fat ox, a sheep, horse, or mule, as in 1870. In wool growing many patents have been taken out for shearers, and three of them are said to be savers of labor, provided the wool grower is so situated that he can attach the shearer to a horse or steam power.

There have been since the opening of the Office 6,620 patents for harvesters, of which the only great improvement since 1870 is the twine binder, for which over 900 patents have been taken out. The beheader is used in California, as it was before 1870, and in the prairie regions the sheaf-carrier has recently been introduced, holding the sheaves until enough are collected to make a shock. Counting the labor of the men who did the binding after the original McCormick reaper at $2 per day, the total saving by all these improvements since 1870 is estimated at 6 cents per bushel for wheat, rye, and oats. Much of this saving in labor is neutralized by cost of machines, interest, and repairs. There have been nearly 3,000 patents in fences, over 5,000 in the making of boots and shoes, and in stoves and heaters 8,240, none affecting farm labor except the first. In cotton growing exactly the same processes are used, from planting to picking, as in 1850; but out of many hundred attempts to invent a cotton picker it is now claimed that one is a success, though it has not yet got into use. The cost of ginning the cotton has been reduced about two-fifths of a cent per pound. There have been 176 patents for saw gins, 63 for roller gins, and 47 for feeders to gins, out of all of which there has been a new gin evolved which will be in use hereafter. I might thus go around the list, but enough has been said to show that nearly all our farm machinery was in use before 1870, and that since that date, as I said, the reduction of labor cost has not upon the whole field exceeded 2½ per cent. The assertion that reduced transportation lowers the farm price is in flat contradiction of political economy, as, according to that, the benefits should be divided between producer and consumer, the farm price rising and the city or export price declining.

The price of what the farmer has to buy has declined in equal if not greater ratio, and so his margin is as great as ever.

It is evident that you are not a practical farmer. However, your non-acquaintance with the figures is not to be wondered at when we consider what has been said by great scholars and statesmen. I recently heard a politician, and one of perfectly Himalayan greatness, say in debate that a day’s work on an Illinois farm would now produce more than twice as much as in 1870, and another clinched it by adding that a man could pay for a good farm by his surplus from five years’ crops. Now go to some practical farmer and get him to make the calculation, and you will find that what he has saved by reduced prices is less than one-fifth of what he has lost from the same cause. The average farm family in the central West consists of five persons, and their greatest saving has been on clothing. You may set that at $30 per year. The next is in sugar, for which they pay but half the price of 1873. There is no other item that will reach $5, not even including all the iron or steel they have to buy in a year. The largest estimate of gains, unless they go into luxuries, does not exceed $90 per year. At least a third of this gain is offset by increased taxes.

Now let us see what this farm family has lost, counting only the price of the surplus it sells and taking our average from the official reports. On 500 bushels of wheat, at least $250; on 600 bushels of corn, $120; on ten tons of hay, $30; on rye, oats, potatoes, and so forth, $50; on three horses and mules sold per year, $100. Total, $550, being more than ten times the net gain over taxes.

The Agricultural Department figures indicate that, taking the United States as a whole, including even the intensive farming near the cities, the reduction of annual income is a few cents over $6 per acre. Thus something like $1,800,000,000 has been taken from the farmers’ annual income, and the farmer being just like any other man, in that he cannot spend money that he does not get, this withdraws $1,800,000,000 from the manufacturers’ and general market. In view of these figures—and if anything I have understated them—what conceivable good would a raise in the tariff do the manufacturers so long as our farmers must sell on a gold basis and be subject at the same time to the rapidly increasing competition of silver basis countries? I have said nothing of fixed charges which do not decline, or of the cost of the federal government, which steadily and rapidly increases. Have you heard of any decline in official salaries, taxes, debts, bonds, or mortgages?

That is plausible at first view, but it cannot be true as to the country generally, because wages have risen; or at least they had risen continuously till 1892, as is clearly shown in the Aldrich Report.

The Aldrich Report is a miserable fraud. It does not so much as mention farmers and planters or any of the laboring classes immediately dependent on farmers. It gives only the wages of the highest class of skilled laborers and in those trades only where the men are organized in ironbound trades unions which force up the wages of their members. Take the lists and census and add the numbers employed in every trade mentioned in that report, and you will find that all together they only amount to one fourth the number of farmers, or about 12 per cent. of the labor of the country. Furthermore, it takes no account whatever of the immense percentage of men in each trade who are out of employment. One who didn’t know better would conclude from it that our coal miners worked 300 days in the year, and that stone masons, plasterers, and the like worked all the year in the latitude of New York and Chicago. And these are but a few of the tricks and absurdities of the report.

Wages are labor’s share of its own product. The claim that wages generally can rise on a declining market involves a flat contradiction of arithmetic; it assumes that the separate factors can increase while the sum total is decreasing, and that the operator can pay more while he is every day getting less. The whole philosophy of the subject was admirably summed up by a Southern negro with whom I recently talked. “If wages be up, how come ’em up? We all’s gittin’ but half what we useter git for our cotton, and how kin five cents a pound pay me like ten cents a pound, and me a pickin’ out no mo’ cotton?” His philosophy applies to 60 per cent. of all the working people in the United States, for that proportion do not work for money wages. They produce, and what they sell the product for is their wages. Viewed in this, the only true light, the wages of 60 per cent. of our laborers have declined nearly one half, making the average decline for all laborers nearly a third. How, indeed, could it be otherwise? Will any sensible man believe that a farmer could pay men as much to produce wheat at $.50 as at $1.50? Or take the case of the cotton grower. It takes a talented negro to make and save 3,000 pounds of lint cotton; when he sold it at $.10 he got $300, and when he sells it at $.05 he gets $150, and all the tricks of all the goldbugs in the world cannot make it otherwise. To tell such men that their wages have increased, in the face of what they know to be the facts, is arrogant and insulting nonsense.

This nation should have the best money in the world.

Very true. And the question of what is the best can only be determined by science and experience. It is certain that gold standing alone is not; for its fluctuations in purchasing power have been so tremendous as again and again to throw the commercial world into jimjams. History shows that it has varied 100 per cent. in a century, and we have seen in this country that its value declined about 25 per cent. from 1848 to 1857, and that it has increased something like 60 per cent. since 1873. Without desiring to be ill-natured, I must say it seems to me that a man has a queerly constituted mind who insists that that is the only “honest money.”

But we don’t want 50-cent dollars.

And you can’t have ’em, my dear sir. A dollar consists of 100 cents. The phrase “50-cent dollar” and that other phrase “honest money” remind me of what I used to hear in my boyhood when the slavery question was debated with such heat: “What! Would you want your sister to marry a nigger? Whoosh!” It was assumed, if a man denounced slavery, that he wanted the colored man for a brother-in-law. Men who employ such phrases show a secret consciousness of having a weak cause. And while I am about it I may as well add that I do not admire the way some of our fellows have of denouncing gold as “British money.” Great fools, indeed, the British would be if they did not fight for a gold basis, for by reason of it they get twice as much of our wheat, meat, and cotton for the $200,000,000 per year we have to pay them in interest. According to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the world owes England $12,000,000,000, on which she realizes a little over four and a half per cent., or pretty nearly $600,000,000 per year. Fully that, if we add income from property her citizens own in this and other countries. On the day we demonetized silver, that $600,000,000 could have been paid in gold in the port of New York with 450,000,000 bushels of wheat; to-day it would take 900,000,000 bushels. In short, the amount of grain England has made clear because of the rest of the world adopting monometallism would bread all her people, feed all her live stock, and make three gallons of whiskey for every person on the island. Why shouldn’t they take what the world willingly gives them? I have my opinion, however, of the common sense of a world which does things that way.

We want money that is equally good all over the world.

There is no such money. The coin we send abroad is only bullion when it gets there, and most dealers prefer government bars. The exchange must be calculated exactly the same whether we use gold, silver, or paper in our domestic trade; and this notion that we “should be at a disadvantage in the exchange” is a delusion. The variations in the value of the greenback during our war era were calculated daily, and prices in this country rose or fell to correspond. It must, I say, be calculated just the same in gold or silver, and any smart schoolboy can do it in a minute on any transaction.

What I mean is that the silver dollar is worth only 50 cents in gold.

And by the same token the gold dollar is worth 200 cents in silver. The answer is as logical as the quip, and neither is worth notice. Such a process merely assumes an arbitrary standard and measures all other things by it, as the drunkard in a certain stage of intoxication thinks that his company is drunk while he is duly sober. And, by the way, where do you get your moral right to say that a dollar which will buy two bushels of wheat or twenty pounds of cotton is any more honest than one which will buy one bushel or ten pounds? Is it because with the dear dollar the farmer must work twice as long to pay off a mortgage, that the interest paid on the great debts of the world will buy twice as much, and the debtor nations are put at a terrible disadvantage as to the creditor nations personally? Is that honest?

A very safe test of any theory is to follow it to its logical conclusion. Take your “honest” money argument, on the basis of twenty years’ experience, and see where it will take you in the near future. The dollar which buys two bushels of wheat or sixteen pounds of cotton is “honest,” you say, and a dollar which buys but one bushel or eight pounds is not. By and by, if your fallacy prevails, the dollar will buy three bushels of wheat or twenty-five pounds of cotton, and will then, by your reasoning, be much more “honest” than now. Is that your idea? How much lower must prices go before you will admit that gold has gained in purchasing power?

But it cannot be that prices have fallen because of the scarcity of money, for the low rate of interest now prevailing proves that money is abundant and cheap.

That is a very old fallacy, and a singularly tenacious one, as it seems that no amount of experience drives it from the minds of men. Look over the history of our panics and you will find that after the first convulsion is past the banks are soon crowded with idle money, and the rate of interest falls. Take notice, however, that the money lenders always declare that they must have “gilt-edged paper.” Interest on first-class securities is never lower than in the hardest times which follow a particularly severe panic, and the reason is obvious: all far-seeing business men know that prices are likely to fall, and, consequently, investments become unprofitable: therefore they do not invest; therefore they do not want money; therefore they do not borrow, and idle money accumulates. This is a phenomenon always observed in hard times. In good times, on the contrary, when investments are reasonably sure to be profitable, there is naturally an increased demand for money, and so the rate of interest rises. As a matter of fact, however, interest rates, when properly estimated, have been for several years past very much higher than previously—that is, the borrower has, in actual value, paid very much more; so rapid has been the increase of the purchasing power of money, that the six per cent. now paid on a loan will buy more than the ten per cent. paid a few years ago. In addition to that, the value of the loan has been steadily increasing. Make a calculation for either of the years since 1890, and you will find it to be something like this: the six per cent. paid as interest has the purchasing power of at least ten per cent. a few years ago, and the lender has gained at least two per cent. a year, if not twice that, by the increased value of his money; so the borrower will have paid, at the maturity of his obligation, at least twelve per cent. per annum, and probably much more.

The silent and insidious increase of their obligations, by reason of the enhanced and steadily enhancing value of gold, has ruined many thousands of business men who are even now unconscious of the real cause or of the power that has destroyed them.

I may add in this connection that the three per cent. now paid on a United States bond is worth about as much in commodities as the six per cent. paid previous to 1870, and at the same time the bond has doubled in value for the same reason; thus, calculated on the basis of twenty-five years, the bondholder is really receiving, or has received, the equivalent of ten per cent. interest.

Gold has an intrinsic value, says the monometallist, which makes it the money of the world. It is sound and stable, while silver fluctuates. See how much more silver an ounce of gold will buy than in 1873, but the gold dollar remains the same, worth its face as bullion anywhere in the world.

But suppose there had been a general demonetization of gold instead of silver, how would the ratio have stood then? Would not the same reasoning prove silver unchangeable, and gold the fluctuating metal?

Oh, nonsense! it is impossible to demonetize gold, because the civilized world recognizes it as an invariable standard by which all commodities are measured in value. The supposition is absurd. It would be very much like deoxygenizing the air.

But, my dear sir, gold has been demonetized, and not very long ago, either, and very extensively, too. It was deprived of its legal tender quality by four great nations, comprising some seventy million people; demonetized because it was cheap and because the world’s creditors believed it was going to be cheaper; the demonetization, so far as it went, produced enormous evils, and nothing but the firmness of France and the far-seeing wisdom of her financiers prevented the demonetization becoming general on the continent of Europe, which would have reversed the present position of the two metals in the public mind.

Of the many singular features in the present overheated controversy, probably the most singular is the fact that comparatively few bimetallists know of, or, at any rate, say much about, this demonetization of gold, while the monometallists ignore it entirely, and many of them, who ought to know better, absolutely deny it.

So extensive was this demonetization of gold, and so far-reaching were its consequences, that it may easily be believed that it was the beginning of all our misfortunes, and that the crime of the century, instead of being the demonetization of silver in 1873, was really the demonetization of gold in 1857; for that was the first general or preconcerted international action to destroy the monetary functions of one of the metals and throw the burden upon the other, and it first familiarized the minds of financiers, and especially of the creditor classes, with the fact that the thing might easily be done and that it would work enormously to their advantage.

It may also be said that it led logically to the action of 1867, which was but the beginning of a general demonetization of silver.

The history of gold demonetization is full of instruction and is here given in detail.

In 1840-45 the world was hungering for gold. All the leading nations had just passed through financial convulsions which shook the very foundations of society. Several American states had either repudiated their debts outright or scaled them in ways that to the English mind looked dishonest, and there was a general uneasiness among the creditor classes of the world. A universal fall of prices had produced the same results with which we are now so painfully familiar. In the half century terminating with 1840 the world had produced but $529,942,000 in gold, coinage value, and $1,364,697,000 in silver, or some forty ounces of silver to one of gold; yet their ratio of values had varied but little, and the variation was not increasing. Why? Monometallists have raked the world in vain for an answer. Bimetallists point to the only one that is satisfactory, namely, the persistence of France in treating both metals equally at her mints. But there were grave apprehensions that France alone could not maintain the parity, and so, as aforesaid, all the world was hungry for gold.

And in all the world there was not one observer who dreamed that this hunger would soon be far more than satiated, and the philosopher who should have predicted half of what was soon to come would have been jeered at as a crazy optimist. In 1848 gold was discovered in California, and three years later in Australia. The supply from Africa and the sands of the Ural Mountains had previously increased, so that in 1847-8 it was equal to that of silver. But how trifling was this increase to what followed. In 1849 there was still a slight excess of silver production, and in 1850 the proportion was but $44,450,000 of gold to $39,000,000 in silver. Then gold production went forward by great leaps and bounds. How much was produced?

Well, the estimates vary greatly. Soetbeer places the amount at $1,407,000,000 by the close of 1860; but Tooke and Newmarche have put it about $100,000,000 less. In the same era the production of silver varied but a trifle from $40,000,000 a year. A committee of the United States Senate, appointed for investigating the facts, reported that in the twelve years ending with 1860 the gold produced was $1,339,400,000; and in the next thirteen years, ending with 1873, it was $1,411,825,000. Thus, in the thirteen years following the California discovery the stock of gold in the world was doubled, and in the twenty-five years ending with 1873 it was more than tripled. Several economic writers have made the statement very much stronger than this, and M. Chevalier, in his famous argument for the demonetization of gold, written in 1857, declares that the production of gold as compared with silver had increased fivefold in six years and fifteenfold in forty years, and that, owing to the export of silver to Asia and its use in the arts, there would, in a very little while, be no possible method of maintaining the parity of the two metals in money at any ratio which would be honest and profitable.

And what was the real fact? The ratio, which in 1849 was 1578/100 of silver to 1 of gold in the London market, and the same in 1850, never sank below 1519/100 to 1, and never rose above the ratio of 1849 till after silver was demonetized. Why this wonderful steadiness? The answer is easy. In the eight years of 1853-60 France imported gold to the value of 3,082,000,000 f., or $616,000,000, and exported silver to the value of $293,000,000; in short, her bullion operations amounted to $909,000,000. She stood it without a quiver; she grew and prospered as never before. She resolutely refused to change her ratio. Her mints stood open to all the gold and silver of the world, and thus did she save the world from a great calamity.

Scarcely, however, had the golden flood begun when the moneyed classes and those with fixed incomes raised a loud cry. From the laboring producers no complaint was heard. They never complain of increased coinage. In the United States we knew nothing of this clamor, for we then had no large creditor class, no great amount of bonds, and very few people interested more in the value of money than in the rewards of labor. In Europe, however, all the leading writers on finance and industries took part. In 1852 M. Leon Faucher wrote: “Every one was frightened ten years ago at the prospect of the depreciation of silver; during the last eighteen months it is the diminution in the price of gold that has been alarming the public.” In England, the philosopher DeQuincey wrote that California and Australia might be relied upon to furnish the world $350,000,000 in gold per year for many years, thus rendering the metal practically worthless for monetary purposes, and another Englishman, as if resolved to go one better, declared that gold would soon be fit only for the dust pan. M. Chevalier took up the task of convincing the nations that gold should be demonetized as too cheap for a currency, and of course the interested classes soon organized for action.

Holland had already begun the process in 1847, but had managed it so awkwardly that her condition is not easily understood or described as it was in 1857. The estimated amount to be thrown out of use was only half the real amount, and in the attempt to avoid a small evil they produced a very great one.

Austria was at that time involved in trouble with her paper money system, and thought the cheapening of gold offered a fair opportunity to come to a metallic basis. The reasoning of her statesmen was singularly like that of General Grant in 1874, when he pointed to the great silver discoveries in Nevada as a providential aid to the restoration of specie payments, being at the time in sublime ignorance that he had long before signed an act demonetizing silver, and thereby depriving this country of the benefit of such providential aid. But the strength of the creditor classes was entirely too much for Austria and Prussia, and the German States allied with them almost unanimously declared for throwing gold out of circulation. A convention had been held at Dresden in 1838, with the view to unifying the coinage, but little had been accomplished, and now a convention was called at Vienna, which was attended by authorized representatives of Prussia, Austria, and the South German States. It was there stated that, besides various minor coins, there were three great competing systems in Germany, namely, those of Austria, Prussia, and Bavaria. It is needless to go into details of this once famous convention, but suffice it to say that the following points were agreed upon: (1) The Prussian thaler was to be the standard for Prussia and the South German States, and was to be a silver standard exclusively. (2) The Austrian silver standard was to prevail throughout that empire. (3) The contracting powers could coin trade coins in gold, but none others, except Austria, which retained the right of coining ducats, and these gold coins were to have their value fixed entirely by the relation of the supply to the demand. “They were not therefore to be considered as mediums of payments in the same nature as the legal silver currency, and nobody was legally bound to receive them as such;” in short, none of the gold coins permitted by the convention were to be legal tender, but all were to be mere trade coins precisely for the same purpose as the trade dollar once so famous in the United States. The result, of course, was to make silver the standard and gold the fluctuating money or token money. The effects of this convention remained with but little change till 1871.

Of course, gold at once became “dishonest money.” It was worth less than silver, and a regular gold panic set in. Holland had already demonetized most of her gold coinage, that is, had deprived it of the legal tender quality, and Portugal now practically prohibited any gold from having current value, except English sovereigns. Belgium demonetized all its gold at one sweep, and Russia prohibited the export of silver. Thus, in an alarmingly short space of time five nations had practically demonetized gold, and others were threatening to do so, and the world was rapidly being taught that gold was the discredited metal, while silver was the stable and sound money.

Some curious and a few amusing results followed. Among a certain class in England a regular panic broke out, and in Holland and Belgium even the masses of the people became suspicious of gold and disliked to take it in payment. In the latter country a few traders hung out signs to attract customers, to this effect, “L’or est recu sans perte,” meaning that gold money would be taken there without a discount. It is probably not known to one American in a thousand that the practice of inserting a silver clause in contracts became at that time so common in Europe that it was actually transferred to the United States, and in England life insurance companies were established on a silver basis. Several American corporations stipulated for payment in silver, especially of rents, and to this day a New England establishment is receiving a certain number of ounces of fine silver yearly under leases then drawn up.

It is equally interesting to note in the literature of that period arguments against gold almost word for word like those now used against silver. The financial managers threw gold out of use and then urged its non-use as a reason for its demonetization. “None in circulation,” “variation shows impossibility of bimetallism”—such were the phrases then applied to gold, as we now find them applied to silver. An artificial disturbance was created, and then pleaded as a reason for further disturbance.

All this while the financiers of England were bombarded with arguments and prophecies of evil, but her geologists pointed out clearly that Australian and Californian products were almost entirely from the washing of alluvial sands and consequently must be very temporary. Her statesmen believed the geologists rather than the panic-stricken financiers, and so she held for gold monometallism.

But it is to France that the world is indebted for maintaining the parity through those years of alarm and panic. M. Chevalier urged upon French statesmen the importance of returning to the system which had been in force previous to 1785, when silver was the standard and gold was rated to it by a law or proclamation. The proposition was actually brought forward in Council and urged upon the Emperor that silver should be made the standard and gold re-rated in proportion to it every six months. The net result was, by France taking in gold and letting out silver, that in 1865 that country had a larger stock of gold than any other in Europe. Suffice it to repeat that several nations, including seventy million people, actually demonetized gold, deprived it of its legal tender, and treated it as a ratable commodity; while France, single-handed and alone upon the continent of Europe, was able to absorb the enormous surplus of gold and maintain the parity by the simple process of keeping her mints open to both at the ancient ratio.

Thus ended the scheme to drive gold out of circulation and base the business of the world upon one metal, and that the dearer metal, silver. But suppose the scheme had succeeded; suppose France had been less firm; what a wonderful flood of wisdom on the virtues of silver we should have had from the monometallists! How arrogantly they would have denounced us—who should, I trust, in that case have been laboring to restore gold to free coinage—how arrogantly they would have denounced us as the advocates of cheap money, dishonest tricksters, repudiators! How they would have rung the changes on “dishonest money,” “fifty-cent gold dollars!” What long, long columns of figures should we have had to prove the stability of silver, the fluctuating nature of gold! What denunciations, what sneers, what gibes, what slurs would have filled the New York city papers in regard to those Western fellows who want to degrade the standard! How glib would have been the tongues of their orators in denouncing all who advocated the remonetization of gold as cranks, socialists, populists, anarchists, ne’er-do-wells, and Adullamites, kickers, visionaries, and frauds! Is there any practical doubt that we should have witnessed all this? None whatever; in fact, something of the same sort was heard in Europe at the time of the demonetization of gold. It all goes to show that self-interest blinds the intellects of the best of men so that they readily believe that which is to their interest is honest, but that the farmer who seeks to raise the price of what he has to sell thereby throws himself down as dishonest. Of course, the successful demonetization of gold would have brought about an enormous appreciation of the value of silver, since it would have thrown the whole burden of maintaining the business of the world upon one metal, and equally, of course, we should have had the same attacks upon the owners of gold mines that we now have upon the owners of silver mines. As the withdrawal of silver from its place as primary money and its reduction to the level of token money has thrown the burden of sustaining prices upon gold, so unquestionably would the reverse process have occurred had gold been reduced to token money in place of silver. All this we know would have taken place from what actually did take place, and this makes important the history of the demonetization of gold.

Among the many plausible pleas of the monometallists, the most plausible, perhaps, is the plea that the great divergence between the metals since 1873 has been due entirely to the increased production of silver. A very brief examination, I think, will show its falsity, and that it is equally false in fact and fallacious in logic; for, first, there has been no great “depreciation” in silver, that metal having almost the same power to command commodities, excepting gold, that it had in 1873; and, second, the claim that the increased production of ten or twenty years would alone greatly cheapen silver is flatly contradicted by all previous experience. Of many statements of the fallacy, I take a recent one from the New York Times as the most terse and catchy for popular reading, and likewise most ludicrously absurd:

“Why Silver is Cheap.

“In 1873 the total product of silver in the world was 61,100,000 ounces, and the silver in a dollar was worth $1.04 in gold.

“Last year the world’s product of silver was 165,000,000 ounces, and the silver in a dollar was worth only 50.7 cents.

“In 1894 the potato crop of the United States was, in round numbers, 170,000,000 bushels, and the average price 53c.

“In 1895 the estimated potato crop was 400,000,000 bushels, and the average price was 26c.

“The fall in both cases was due to the same cause.”

Observe the assumptions: 1. That the output of one year determined the value of silver as the crop of potatoes does their price for that year! The schoolboy who does not know better deserves the rattan. If the theory were correct, gold in 1856 should have been worth but a fourth what it was in 1848, whereas the largest estimate of its decline in value puts it at 25 per cent.

2. That the increased silver production of twenty-two years would reduce its value in the exact mathematical proportions of the increase. This theory ignores the two most important facts determining the value of money: that the silver or gold mined in any one year is added to the existing stock, to which it is but a minute increase; and that wealth, population, and production are also increasing rapidly, relative to which the increase of silver is but a trifle indeed. The yield of the Monte Real a thousand years ago may have cost five times as much labor per ounce, and that of Laurium ten or even twenty times as much; but all of both which is not lost goes with the last ounce mined into the general stock, which is now about $4,000,000,000 in coin alone. The greatest annual production has in but a very few cases added so much as 3 per cent. to the stock on hand, and about half of it is consumed in the arts. If the increase of the annual production of silver by 2¾ to 1 in twenty-two years reduced its value one-half, will the Times tell us what should have been the reduction in the value of gold when this product increased by fivefold in eight years? It should further be noted that the discovery of a “Big Bonanza” is an event so rare that it has not happened, on an average, more than once in three centuries since the dawn of history, and that since 1873 the growth in the world’s production and trade has been, relative to former times, even greater than the increase in the production of silver.

Consider the following facts, which I have condensed from Mulhall: In 1800 the total yearly international commerce of the world was estimated at $1,510,000,000. Forty years later it had only increased 90 per cent., amounting in 1840 to $2,865,000,000, and in that year there were in all the world but 4,315 miles of railroad and no electric telegraph. The total horse-power of all the steamships of the world was but 330,000, and the carrying power of all the shipping but 10,482,000 tons. To-day the international commerce of the world is almost $20,000,000,000, and increasing at the rate of $1,000,000,000 per year; there are in the world over 400,000 miles of railway and a very much greater mileage of magnetic telegraph, including 14 intercontinental cables; the ocean tonnage of Great Britain alone is very much greater than was that of the whole world in 1840; and tremendous as this increase of international trade has been, it is the merest trifle compared with the increase of the internal trade in several of the greater nations.

What then has caused the “great depreciation”? Nothing has caused it. There has been but a trifling depreciation indeed. It is as clearly proved as anything unseen can be that if the nations had left silver and gold as they were in 1870, both would have gained materially in value, that is, in the power to command commodities, because of the vastly greater relative increase of the latter; but by demonetization all the increase has been concentrated in gold, leaving silver almost exactly as it was. At present, however, I devote myself to the question whether there has been such an increase in the production as would normally cheapen it. On this point we have evidence to convince any unbiased mind, for the relative production of silver and gold has in former ages varied very much more than in the last twenty-three years, and the variation has extended over much longer periods, without causing more than the most trifling divergences in value. And the explanation is simple: the two metals received equal recognition at the mint and in legal tender laws; the greatly increased use of the cheaper maintained its value in coinage, while disuse of the dearer tended equally to check its appreciation. In this sense government can “create value” by creating a use.

From 1660 to 1700, for instance, the production of silver averaged in value much more than twice that of gold, and in quantity some thirty-three times as much; yet all those years, the highest mint ratio was 15.20 to 1 and the lowest 14.81—a variation in money value of but .39 or 2.6 per cent. From 1701 to 1760 inclusive, the proportion of gold produced gradually rose from a little over a third to 40 per cent. in values, yet the money ratio remained remarkably constant, the highest being 15.52 of silver to 1 of gold and the lowest 14.14. In other words, for sixty years there were produced on an average about 28 ounces of silver to 1 of gold, yet the widest variation of their money values in all those years was less than 9 per cent. In the face of such facts as these, we are asked to believe that while an average of over 30 ounces to 1 created an average variation of less than 6 per cent., and a greatest variation of less than 9 per cent., a production of some 20 ounces to 1 since 1882 has created a variation of 100 per cent. And that the variation began nine years before the value production of silver exceeded that of gold! It is an affront to our common sense.

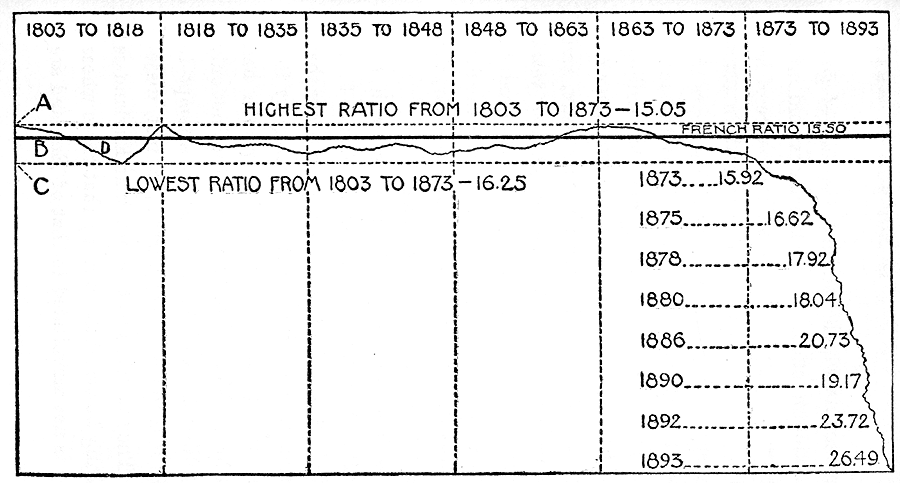

The above diagram shows the relative annual production of gold and silver from 1493 to 1870, and also average ratio of values of the two metals.

I should say, at this point, that my figures are taken from the latest, and in my opinion the most scholarly work in favor of monometallism, “The History of Currency,” by Prof. W. A. Shaw, Fellow of the Royal Historical and Royal Statistical Societies. As the ratio between silver and gold varied considerably in the different marts of Europe, I follow his plan (which is Soetbeer’s) of taking it as it stood at any particular time in the city which might then be called the greatest commercial centre, whether Venice, Hamburg, Antwerp, or London. His history comprises the entire period from 1252 to 1894. It is only fair that I should also give his explanation of the stability of the metals, which is extremely interesting.

He begins his second chapter with the statement that the discovery of America was “the monetary salvation and resurrection of the Old World”; that it was a time of unexampled increase in the precious metals and equally unexampled rise of prices, but there was also “feverish instability and want of equilibrium in the monetary systems of Europe.” He shows how the first great import was of gold, which began to affect prices in 1520; how this was followed by a very much greater increase in silver, and how, while prices were rising so rapidly as to stimulate trade and incidentally do damage by causing great fluctuations, yet there must have been some great regulator preventing the evil which we should a priori have expected. He finds it in the fact that Antwerp had taken the place of Venice and Florence, and conducted a great trade with the far East. His language is: “The centre of European exchanges—Antwerp in the sixteenth century as London to-day—has always performed one supremest function, that of regulating the flow of metals from the New World by means of exporting the overplus to the East. The drain of silver to the East, discernible from the very birth of European commerce, has been the salvation of Europe, and in providing for it Antwerp acted as the safety-valve of the sixteenth century system as London has done since. The importance of the change of the centre of gravity and exchange from Venice to Antwerp, therefore, lies in this fact. Under the old system of overland and limited trade, Venice could only provide for such puny exchange and flow as the mediæval system of Europe demanded; she would have been unable to cope with such a flood of inflowing metal as the sixteenth century witnessed, and Europe would have been overwhelmed.”

Professor Shaw argues that without the Eastern safety-valve Europe would have been ruined by an excess of the precious metals, that India furnished the needed reservoir—did she not take gold as well as silver?—and that Venice was so far limited to an overland trade that she could not have performed the function Antwerp did. Later he sets forth the current monometallist position that the nations are now as one in trade and the interchange of the precious metals, and therefore even the partial equilibrium of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries could not be maintained. Let us, then, bring the figures down to the present, and it will be found, I think, that the farther down we come the weaker does the monometallist contention appear.

The improved, more extended, and more intimate intercourse of the nations brought about by the introduction of steam, electricity, and other agencies tends to minimize the fluctuations of the two metals, and indicates that the divergences of the metals in mediæval times was due rather to the want of speedy, easy, and certain intercourse and communication of the nations than to an innate commercial tendency of the two metals to diverge. Had the same intimate and speedy commercial relation existed between the nations of the world in those times as now exists, the equalizing tendencies of trade would evidently have prevented not only the ratio of divergence to which the metals attained at different periods, but would have prevented a difference of ratio existing between the different nations at the same period of time.

From 1761 to 1800, inclusive, the relative production of gold decreased steadily, until it was but 23.4 per cent. of the total value, to 76.6 per cent. of silver. In other words, there were for many of the later years over 50 ounces of silver produced to 1 of gold, and yet the ratio stood long at 15.68 to 1. This is almost exactly the ratio fixed by Hamilton and Jefferson, fixed because of its long-continued maintenance in European markets. During these forty years the production of silver in proportion to gold was never for even one year as low as the highest proportion of any year since 1873, and yet the money value only varied from 14.42 to 15.72, or a fraction over 8 per cent. In the face of such figures as these, the change in relative production since 1873 seems too trifling to be taken into account, especially since in that year and some time after the value production of gold at 16 to 1 was much the greater, nor was it till 1883 that the world’s silver product exceeded that of gold.

In 1800-10 the annual production of gold was $12,069,000 and of silver almost exactly $39,000,000, or some 50 ounces to 1; yet the highest ratio was 16.08, and the lowest 15.26. This relative production changed very slowly, and in 1831-40 of the total in values produced 34.5 per cent. was gold and 65.5 per cent. silver.

That is, there were, for ten years, about thirty times as many ounces of silver mined as of gold, and during these years the change in the ratio was so minute that it can only be calculated in small fractions of 1 per cent. In 1841-50, for the first time since the middle of the sixteenth century, we find the production of gold the greater, that metal being 52.1 per cent. of the total product, and silver but 47.9 per cent. During the decade the lowest value ratio of silver to gold was 15.70, and the highest 15.93, a variation of only 1.4 per cent. Then California and Australia poured out their wonderful golden flood, and all the world was changed. In 1851-55 the gold yield was 77.6 per cent, of the total, and the silver yield 22.4, and for the next five years the change was but .2 of 1 per cent. In other words, during those ten years the average annual yield of silver was less than 5 ounces to 1 of gold; so if the “overproduction theory” laid down by the Times were correct, gold should have lost—well, at least 70 per cent. of its value in silver. The actual variation was from a ratio of 15.98 to one of 15.46, or a relative depreciation of gold of considerably less than 3 per cent. Now, it is alleged by many who have made a study of prices during that period, that in actual value gold depreciated 25 per cent.; so it is plain that it carried down silver with it, and the only logical explanation is that the mints were equally open to both.

We have seen that in all the century and a half when the mines were pouring forth silver at the rate of from 20 ounces to 1 of gold up to 55 ounces to 1, the greatest variation in their value was less than 9 per cent., and in the twenty years when the silver production was to that of gold as less than 5 ounces to 1, the value of gold produced being more than three times that of silver, their money value varied less than 3 per cent., and yet we are coolly asked to believe that since 1873 silver is to be rated among variable commodities like potatoes, the size of the crop each year determining the value. Monometallists have had much to say about the relative cheapness of gold during those years, and have laid much stress upon the fact that it was an era of great prosperity and rapid development, with rise of wages and the prices of farm produce. In this argument they admit three things: that we have a moral and constitutional right to use the cheaper metal at any time; that we did use gold for all those years simply because it was easier to pay debts with it, that is, it was cheaper, and that the use of the cheaper metal aided greatly in making prosperity. That is all that any bimetallist claims. As the entire burden was not then thrown upon silver, we claim that it should not now be thrown upon gold, doubling or trebling the rate of its advancing value; and as the privilege to use the cheaper metal then checked the advance of the dearer and enhanced prosperity, we insist that the system of that time shall be restored.

The subsequent figures are equally convincing. In 1861-65 the gold products were 72.1 per cent. of the total, the silver 27.9 per cent., the variation in ratio from 15.26 to 15.44. In 1866-70 the production stood 69.4 to 30.6, the variation in ratio 15.43 to 15.60. In 1871-75 production was still 58.5 to 41.5, but the variation in coin value was from 15.57 to 16.62. That something had happened quite aside in its effects from relative production was evident, but the people did not find out what it was till late in 1875. At the time the demonetization act was passed, the ratio was still 15.55 to 1, and one of the reasons given for the act of February 12,1873, was that the silver dollar was worth $1.03 in gold; yet before the close of that year, and before it was known that there was to be any great increase in the product of silver, its relative value ran down till it was below that of gold. Can any one doubt the cause? Surely not if he observes the additional fact that the relative decline of silver continued despite the greater value production of gold, and that 1882, ten years after demonetization, was actually the first year since 1849 in which the world’s production of silver exceeded that of gold. What one hundred and ninety years of continuous and often enormous relative overproduction of silver had not done, ten years of demonetization had accomplished, and that while the relative supply of gold was still the greater. Is it possible to miss the real cause? Is there in Euclid a demonstration more conclusive?

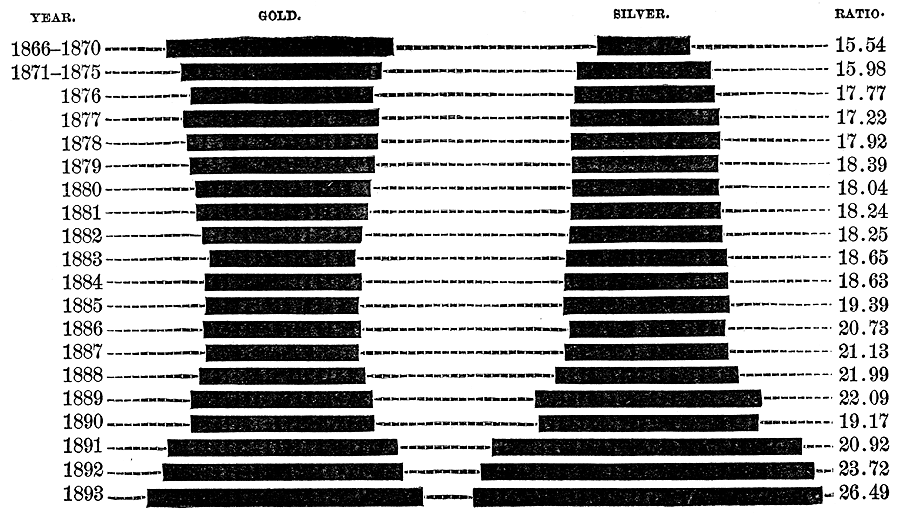

The above diagram shows the relative annual production of gold and silver from 1870 to 1893, and ratio of values.

Monometallists have exhausted the resources of verbal gymnastics to make these figures fit their theories. Determined not to admit that demonetization was the cause, they have given so many explanations that, expressed in the briefest words, they would cover many pages like this. The first was that the opening of the “Big Bonanza” on the Comstock lode had given notice that silver was coming in a flood; but that was only for popular use in this country. Scientific men knew that to be a rare find indeed, not likely to occur again for centuries. The next explanation was that China and India, so long the reservoir into which the surplus flowed, had ceased to absorb it; and the next, demonetization of silver by Germany and her throwing her old silver on the market. And with this the people began to get at the true reason—the general demonetization by so many nations.

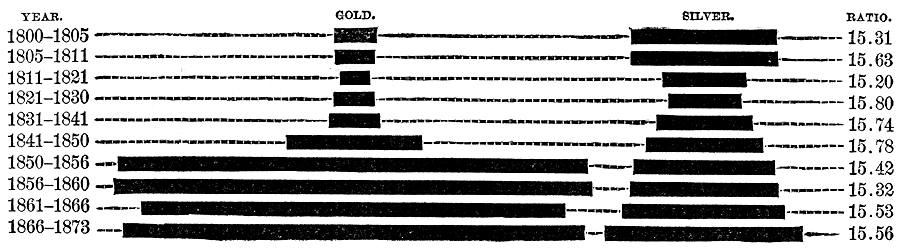

The following table gives the annual production of gold and silver from the discovery of America to and including the year 1892; and the highest and lowest ratio of silver to gold from 1681 to and including the year in which silver ceased to be in this country primary money:

| YEARS. | GOLD. | SILVER. | RATIO. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1493-1520 | $3,855,000 | $1,953,000 | |

| 1521-1544 | 4,759,000 | 3,749,000 | |

| 1545-1560 | 5,657,000 | 12,950,000 | |

| 1561-1580 | 4,546,000 | 12,447,000 | |

| 1581-1600 | 4,905,000 | 17,409,000 | |

| 1601-1620 | 5,662,000 | 17,538,000 | |

| 1621-1640 | 5,516,000 | 16,358,000 | |

| 1641-1660 | 5,829,000 | 15,223,000 | |

| 1661-1680 | 6,154,000 | 14,006,000 | |

| 1681-1700 | 7,154,000 | 14,209,000 | 14.81-15.20 |

| 1701-1720 | 8,520,000 | 14,779,000 | 15.04-15.52 |

| 1721-1740 | 12,681,000 | 17,921,000 | 14.81-15.41 |

| 1741-1760 | 16,356,000 | 22,158,000 | 14.14-15.26 |

| 1761-1780 | 13,761,000 | 27,128,000 | 14.52-15.27 |

| 1781-1800 | 11,823,000 | 36,534,000 | 14.42-15.74 |

| 1801-1810 | 11,815,000 | 37,161,000 | 15.26-16.08 |

| 1811-1820 | 7,606,000 | 22,474,000 | 15.04-16.25 |

| 1821-1830 | 9,448,000 | 19,141,000 | 15.70-15.95 |

| 1831-1840 | 13,484,000 | 24,788,000 | 15.62-15.93 |

| 1841-1850 | 36,393,000 | 32,434,000 | 15.70-15.93 |

| 1851-1855 | 131,268,000 | 36,827,000 | 15.33-15.59 |

| 1856-1860 | 136,946,000 | 37,611,000 | 15.19-15.38 |

| 1861-1865 | 131,728,000 | 45,764,000 | 15.26-15.44 |

| 1866-1870 | 127,537,000 | 55,652,000 | 15.43-15.60 |

| 1871-1872 | 113,431,000 | 81,849,000 | 15.57-15.65 |

| 1873 | 96,200,000 | 81,800,000 | |

| 1874 | 90,750,000 | 71,500,000 | |

| 1875 | 97,500,000 | 80,500,000 | |

| 1876 | 103,700,000 | 87,600,000 | |

| 1877 | 114,000,000 | 81,000,000 | |

| 1878 | 119,000,000 | 95,000,000 | |

| 1879 | 109,000,000 | 96,000,000 | |

| 1880 | 106,500,000 | 96,700,000 | |

| 1881 | 103,000,000 | 102,000,000 | |

| 1882 | 102,000,000 | 111,800,000 | |

| 1883 | 95,400,000 | 115,300,000 | |

| 1884 | 101,700,000 | 105,500,000 | |

| 1885 | 108,400,000 | 118,500,000 | |

| 1886 | 106,000,000 | 120,600,000 | |

| 1887 | 105,000,000 | 124,366,000 | |

| 1888 | 109,900,000 | 142,107,000 | |

| 1889 | 118,800,000 | 162,690,000 | |

| 1890 | 118,848,700 | 172,234,500 | |

| 1891 | 126,183,500 | 186,446,880 | |

| 1892 | 138,861,000 | 196,458,800 |