Title: The Seven Great Monarchies Of The Ancient Eastern World, Vol 3: Media

Author: George Rawlinson

Release date: July 1, 2005 [eBook #16163]

Most recently updated: February 25, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

OF THE ANCIENT EASTERN WORLD; OR, THE HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, AND ANTIQUITIES

OF CHALDAEA, ASSYRIA BABYLON, MEDIA, PERSIA, PARTHIA, AND SASSANIAN, OR

NEW PERSIAN EMPIRE. BY GEORGE RAWLINSON, M.A., CAMDEN

PROFESSOR OF ANCIENT HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOLUME II. WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTRY.

CHAPTER II. CLIMATE AND PRODUCTIONS.

CHAPTER III. CHARACTER, MANNERS AND CUSTOMS.

CHAPTER IV. RELIGION.

CHAPTER V. LANGUAGE AND WRITING.

CHAPTER VI. CHRONOLOGY AND HISTORY.

List of Illustrations

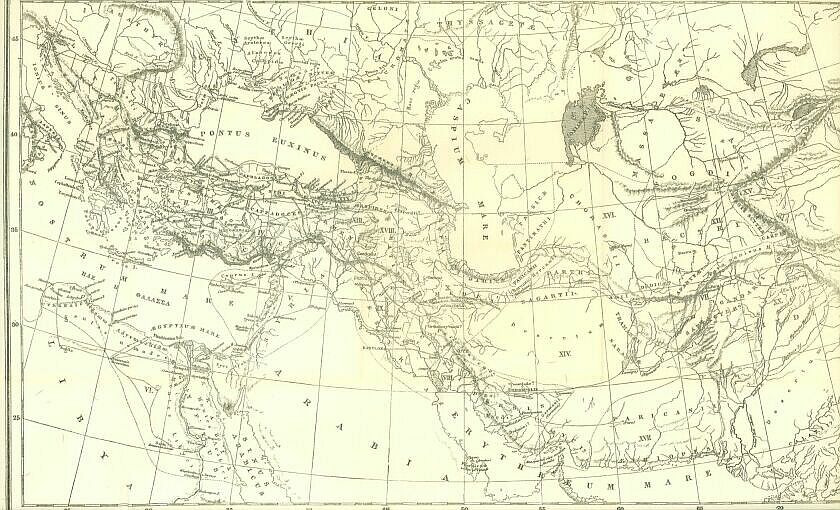

Map

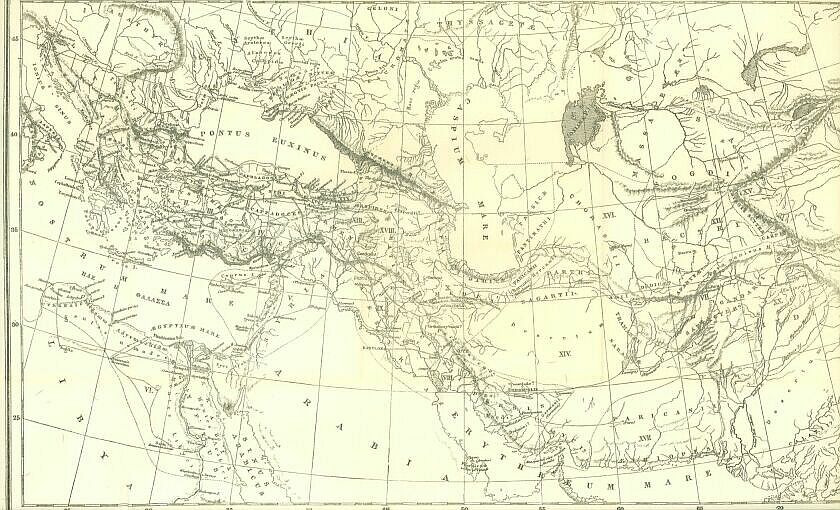

Plate I.

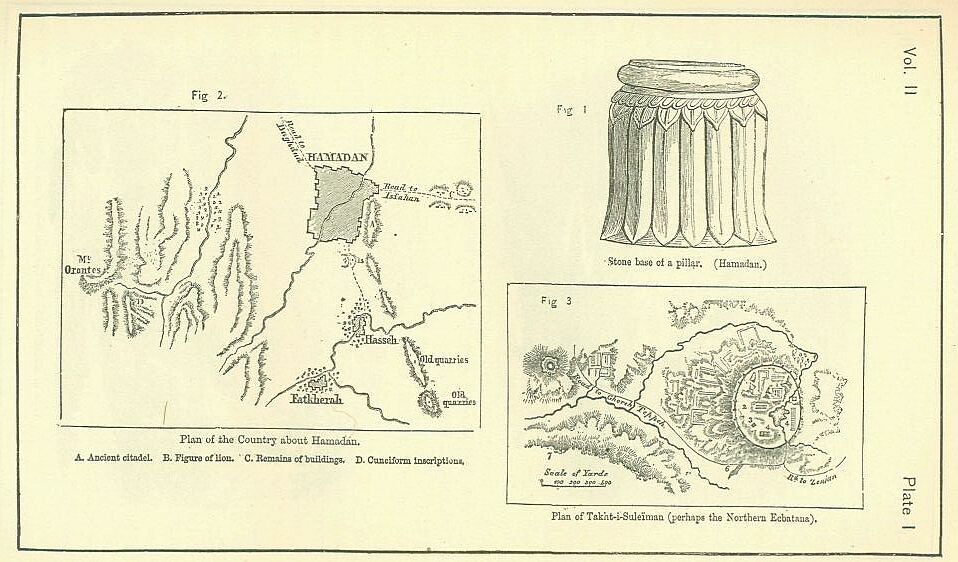

Plate II.

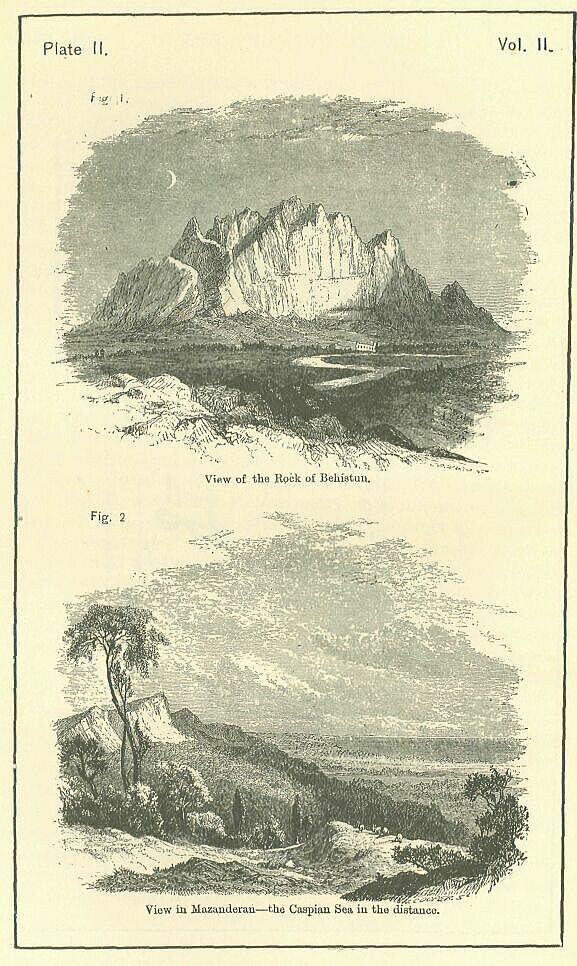

Plate III.

Plate IV.

Plate V.

Plate VI.

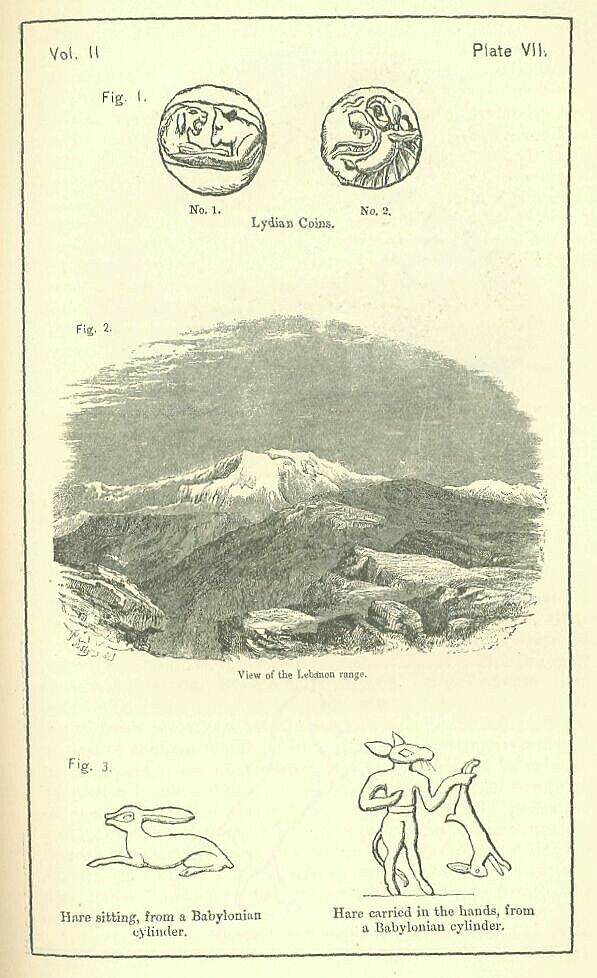

Plate VII.

Along the eastern flank of the great Mesopotamian lowland, curving round it on the north, and stretching beyond it to the south and the south-east, lies a vast elevated region, or highland, no portion of which appears to be less than 3000 feet above the sea-level. This region may be divided, broadly, into two tracts, one consisting of lofty mountainous ridges, which form its outskirts on the north and on the west; the other, in the main a high flat table-land, extending from the foot of the mountain chains, southward to the Indian Ocean, and eastward to the country of the Afghans. The western mountain-country consists, as has been already observed, of six or seven parallel ridges, having a direction nearly from the north-west to the south-east, enclosing between them, valleys of great fertility, and well watered by a large number of plentiful and refreshing streams. This district was known to the ancients as Zagros, while in modern geography it bears the names of Kurdistan and Luristan. It has always been inhabited by a multitude of warlike tribes, and has rarely formed for any long period a portion of any settled monarchy. Full of torrents, of deep ravines, or rocky summits, abrupt and almost inaccessible; containing but few passes, and those narrow and easily defensible; secure, moreover, owing to the rigor of its climate, from hostile invasion during more than half the year; it has defied all attempts to effect its permanent subjugation, whether made by Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Parthians, or Turks, and remains to this day as independent of the great powers in its neighborhood as it was when the Assyrian armies first penetrated its recesses. Nature seems to have constructed it to be a nursery of hardy and vigorous men, a stumbling-block to conquerors, a thorn in the side of every powerful empire which arises in this part of the great eastern continent.

The northern mountain country—known to modern geographers as Eiburz—is a tract of far less importance. It is not composed, like Zagros, of a number of parallel chains, but consists of a single lofty ridge, furrowed by ravines and valleys, from which spurs are thrown out, running in general at right angles to its axis. Its width is comparatively slight; and instead of giving birth to numerous large rivers, it forms only a small number of insignificant streams, often dry in summer, which have short courses, being soon absorbed either by the Caspian or the Desert. Its most striking feature is the snowy peak of Demavend, which impends over Teheran, and appears to be the highest summit in the part of Asia west of the Himalayas.

The elevated plateau which stretches from the foot of those two mountain regions to the south and east is, for the most part, a flat sandy desert, incapable of sustaining more than a sparse and scanty population. The northern and western portions are, however, less arid than the east and south, being watered to some distance by the streams that descend from Zagros and Elburz, and deriving fertility also from the spring rains. Some of the rivers which flow from Zagros on this side are large and strong. One, the Kizil-Uzen, reaches the Caspian. Another, the Zenderud, fertilizes a large district near Isfahan. A third, the Bendamir, flows by Persepolis and terminates in a sheet of water of some size—lake Bakhtigan. A tract thus intervenes between the mountain regions and the desert which, though it cannot be called fertile, is fairly productive, and can support a large settled population. This forms the chief portion of the region which the ancients called Media, as being the country inhabited by the race on whose history we are about to enter.

Media, however, included, besides this, another tract of considerable size and importance. At the north-western angle of the region above described, in the corner whence the two great chains branch out to the south and to the east, is a tract composed almost entirely of mountains, which the Greeks called Atropatene, and which is now known as Azerbijan. This district lies further to the north than the rest of Media, being in the same parallels with the lower part of the Caspian Sea. It comprises the entire basin of Lake Urumiyeh, together with the country intervening between that basin and the high mountain chain which curves round the south-western corner of the Caspian, It is a region generally somewhat sterile, but containing a certain quantity of very, fertile territory, more particularly in the Urumiyeh basin, and towards the mouth of the river Araxes.

The boundaries of Media are given somewhat differently by different writers, and no doubt they actually varied at different periods; but the variations were not great, and the natural limits, on three sides at any rate, may be laid down with tolerable precision. Towards the north the boundary was at first the mountain chain closing in on that side the Urumiyeh basin, after which it seems to have been held that the true limit was the Araxes, to its entrance on the low country, and then the mountain chain west and south of the Caspian. Westward, the line of demarcation may be best regarded as, towards the south, running along the centre of the Zagros region; and, above this, as formed by that continuation of the Zagros chain which separates the Urumiyeh from the Van basin. Eastward, the boundary was marked by the spur from the Elburz, across which lay the pass known as the Pylse Caspise, and below this by the great salt desert, whose western limit is nearly in the same longitude. Towards the south there was no marked line or natural boundary; and it is difficult to say with any exactness how much of the great plateau belonged to Media and how much to Persia. Having regard, however, to the situation of Hamadan, which, as the capital, should have been tolerably central, and to the general account which historians and geographers give of the size of Media, we may place the southern limit with much probability about the line of the thirty-second parallel, which is nearly the present boundary between Irak and Fars.

The shape of Media has been called a square; but it is rather a long parallelogram, whose two principal sides face respectively the north-east and the south-west, while the ends or shorter sides front to the south-east and to the northwest. Its length in its greater direction is about 600 miles, and its width about 250 miles. It must thus contain nearly 150,000 square miles, an area considerably larger than that of Assyria and Chaldaea put together, and quite sufficient to constitute a state of the first class, even according to the ideas of modern Europe. It is nearly one-fifth more than the area of the British Islands, and half as much again as that of Prussia, or of peninsular Italy. It equals three fourths of France, or three fifths of Germany. It has, moreover, the great advantage of compactness, forming a single solid mass, with no straggling or outlying portions; and it is strongly defended on almost every side by natural barriers offering great difficulties to an invader.

In comparison with the countries which formed the seats of the two monarchies already described, the general character of the Median territory is undoubtedly one of sterility. The high table-land is everywhere intersected by rocky ranges, spurs from Zagros, which have a general direction from west to east, and separate the country into a number of parallel broad valleys, or long plains, opening out into the desert. The appearance of these ranges is almost everywhere bare, arid, and forbidding. Above, they present to the eye huge masses of gray rock piled one upon another; below, a slope of detritus, destitute of trees or shrubs, and only occasionally nourishing a dry and scanty herbage. The appearance of the plains is little superior; they are flat and without undulations, composed in general of gravel or hard clay, and rarely enlivened by any show of water; except for two months in the spring, they exhibit to the eye a uniform brown expanse, almost treeless, which impresses the traveller with a feeling of sadness and weariness. Even in Azerbijan, which is one of the least arid portions of the territory, vast tracks consist of open undulating downs, desolate and sterile, bearing only a coarse withered grass and a few stunted bushes.

Still there are considerable exceptions to this general aspect of desolation. In the worst parts of the region there is a time after the spring rains when nature puts on a holiday dress, and the country becomes gay and cheerful. The slopes at the base of the rocky ranges are tinged with an emerald green: a richer vegetation springs up over the plains, which are covered with a fine herbage or with a variety of crops; the fruit trees which surround the villages burst out into the most luxuriant blossom; the roses come into bloom, and their perfume everywhere fills the air. For the two months of April and May the whole face of the country is changed, and a lovely verdure replaces the ordinary dull sterility.

In a certain number of more favored spots beauty and fertility are found during nearly the whole of the year. All round the shores of Lake Urumiyeh, more especially in the rich plain of Miyandab at its southern extremity, along the valleys of the Aras, the Kizil-uzen, and the Jaghetu, in the great valley of Linjan, fertilized by irrigation from the Zenderud, in the Zagros valleys, and in various other places, there is an excellent soil which produces abundantly with very slight cultivation.

The general sterility of Media arises from the scantiness of the water supply. It has but few rivers, and the streams that it possesses run for the most part in deep and narrow valleys sunk below the general level of the country, so that they cannot be applied at all widely to purposes of irrigation. Moreover, some of them are, unfortunately, impregnated with salt to such an extent that they are altogether useless for this purpose; and indeed, instead of fertilizing, spread around them desolation and barrenness. The only Median streams which are of sufficient importance to require description are the Aras, the Kizil-Uzen, the Jaghetu, the Aji-Su and the Zenderud, or river of Isfahan.

The Aras is only very partially a Median stream. It rises from several sources in the mountain tract between Kars and Erzeroum, and runs with a generally eastern direction through Armenia to the longitude of Mount Ararat, where it crosses the fortieth parallel and begins to trend southward, flowing along the eastern side of Ararat in a south-easterly direction, nearly to the Julfa ferry on the high road from Erivan to Tabriz. From this point it runs only a little south of east to long. 46° 30’ E. from Greenwich, when it makes almost a right angle and runs directly north-east to its junction with the Kur at Djavat. Soon after this it curves to the south, and enters the Caspian by several mouths in lat. 39° 10’ nearly. The Aras is a considerable stream almost from its source. At Hassan-Kaleh, less than twenty miles from Erzeroum, where the river is forded in several branches, the water reaches to the saddle-girths. At Keupri-Kieui, not much lower, the stream is crossed by a bridge of seven arches. At the Julfa ferry it is fifty yards wide, and runs with a strong current. At Megree, thirty miles further down, its width is eighty yards. In spring and early summer the stream receives enormous accessions from the spring rains and the melting of the snows, which produce floods that often cause great damage to the lands and villages along the valley. Hence the difficulty of maintaining bridges over the Aras, which was noted as early as the time of Augustus, and is attested by the ruins of many such structures remaining along its course. Still, there are at the present day at least three bridges over the stream—one, which has been already mentioned, at Keupri-Kieui, another a little above Nakshivan, and the third at Khudoperinski, a little below Megree. The length of the Aras, including only main windings, is 500 miles.

The Kizil-Uzen, or (as it is called in the lower part of its course) the Sefid-Rud, is a stream of less size than the Aras, but more important to Media, within which lies almost the whole of its basin. It drains a tract of 180 miles long by 150 broad before bursting through the Elburz mountain chain, and descending upon the low country which skirts the Caspian. Rising in Persian Kurdistan almost from the foot of Zagros, it runs in a meandering course with a general direction of north-east through that province into the district of Khamseh, where it suddenly sweeps round and flows in a bold curve at the foot of lofty and precipitous rocks, first northwest and then north, nearly to Miana, when it doubles back upon itself, and turning the flank of the Zenjan range runs with a course nearly south-east to Menjil, after which it resumes its original direction of north-east, and, rushing down the pass of Budbar, crosses Ghilan to the Caspian. Though its source is in direct distance no more than 320 miles from its mouth, its entire length, owing to its numerous curves and meanders, is estimated at 490 miles. It is a considerable stream, forded with difficulty, even in the dry season, as high up as Karagul, and crossed by a bridge of three wide arches before its junction with the Garongu river near Miana. In spring and early summer it is an impetuous torrent, and can only be forded within a short distance of its source.

The Jaghetu and the Aji-Su are the two chief rivers of the Urumiyeh basin. The Jaghetu rises from the foot of the Zagros chain, at a very little distance from the source of the Kizil-Uzen. It collects the streams from the range of hills which divides the Kizil-Uzen basin from that of Lake Urumiyeh, and flows in a tolerably straight course first north and then north-west to the south-eastern shore of the lake. Side by side with it for some distance flows the smaller stream of the Tatau, formed by torrents from Zagros; and between them, towards their mouths, is the rich plain of Miyandab, easily irrigated from the two streams, the level of whose beds is above that of the plain, and abundantly productive even under the present system of cultivation. The Aji-Su reaches the lake from the north-east. It rises from Mount Sevilan, within sixty miles of the Caspian, and flows with a course which is at first nearly due south, then north-west, and finally south-west, past the city of Tabriz, to the eastern shore of the lake, which it enters in lat. 37° 50’. The waters of the Aji-Su are, unfortunately, salt, and it is therefore valueless for purposes of irrigation.

The Zenderud or river of Isfahan rises from the eastern flank of the Kuh-i-Zerd (Yellow Mountain), a portion of the Bakhti-yari chain, and, receiving a number of tributaries from the same mountain district, flows with a course which is generally east or somewhat north of east, past the great city of Isfahan—so long the capital of Persia—into the desert country beyond, where it is absorbed in irrigation. Its entire course is perhaps not more than 120 or 130 miles; but running chiefly through a plain region, and being naturally a stream of large size, it is among the most valuable of the Median rivers, its waters being capable of spreading fertility, by means of a proper arrangement of canals, over a vast extent of country, and giving to this part of Iran a sylvan character, scarcely found elsewhere on the plateau.

It will be observed that of these streams there is not one which reaches the ocean. All the rivers of the great Iranic plateau terminate in lakes or inland seas, or else lose themselves in the desert. In general the thirsty sand absorbs, within a short distance of their source, the various brooks and streams which flow south and east into the desert from the northern and western mountain chains, without allowing them to collect into rivers or to carry fertility far into the plain region. The the river of Isfahan forms the only exception to this rule within the limits of the ancient Media. All its other important streams, as has been seen, flow either into the Caspian or into the great lake of Urumiyeh.

That lake itself now requires our attention. It is an oblong basin, stretching in its greater direction from N.N.W. to S.S. E., a distance of above eighty miles, with an average width of about twenty-five miles. On its eastern side a remarkable peninsula, projecting far into its waters, divides it into two portions of very unequal size—a northern and a southern.

The southern one, which is the largest of the two, is diversified towards its centre by a group of islands, some of which are of a considerable size. The lake, like others in this part of Asia, is several thousand feet above the sea level. Its waters are heavily impregnated with salt, resembling those of the Dead Sea. No fish can live in them. When a storm sweeps over their surface it only raises the waves a few feet; and no sooner is it passed than they rapidly subside again into a deep, heavy, death-like sleep. The lake is shallow, nowhere exceeding four fathoms, and averaging about two fathoms—a depth which, however, is rarely attained within two miles of the land. The water is pellucid. To the eye it has the deep blue color of some of the northern Italian lakes, whence it was called by the Armenians the Kapotan Zow or “Blue Sea.”

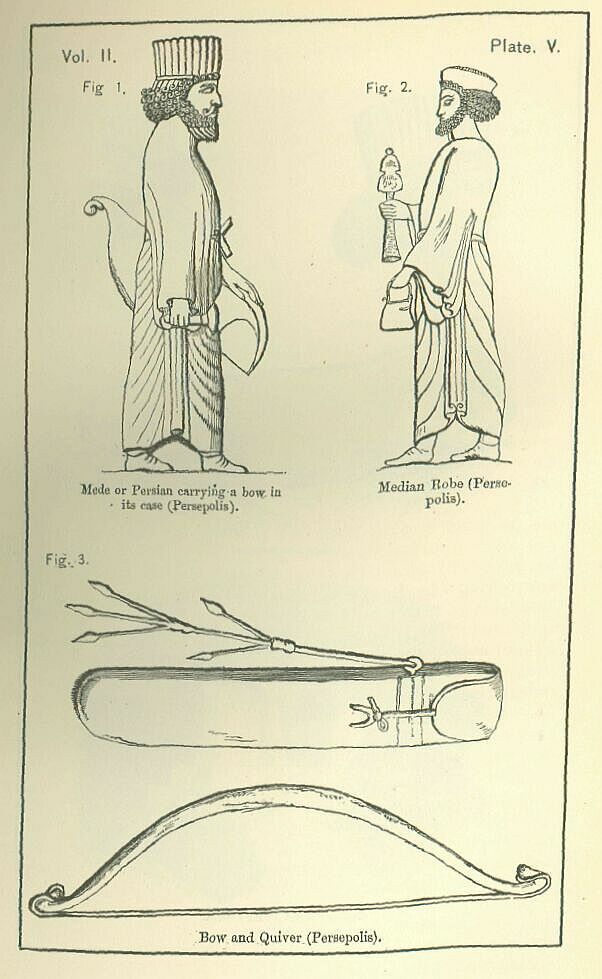

According to the Armenian geography, Media contained eleven districts; Ptolemy makes the number eight; but the classical geographers in general are contented with the twofold division already indicated, and recognized at the constituent parts of Media only Atropatene (now Azerbijan) and Media Magna, a tract which nearly corresponds with the two provinces of Irak Ajemj and Ardelan. Of the minor subdivisions there are but two or three which seem to deserve any special notice. One of these is Ehagiana, or the tract skirting the Elburz Mountains from the vicinity of the Kizil-Uzen (or Sefid-Eud) to the Caspian Gates, a long and narrow slip, fairly productive, but excessively hot in summer, which took its name from the important city of Rhages. Another is Nissea, a name which the Medes seem to have carried with them from their early eastern abodes, and to have applied to some high upland plains west of the main chain of Zagros, which were peculiarly favorable to the breeding of horses. As Alexander visited these pastures on his way from Susa to Ecbatana, they must necessarily have lain to the south of the latter city. Most probably they are to be identified with the modern plains of Kbawah and Alishtar, between Behistun and Khorramabad, which are even now considered to afford the best summer pasturage in Persia.

It is uncertain whether any of these divisions were known in the time of the great Median Empire. They are not constituted in any case by marked natural lines or features. On the whole it is perhaps most probable that the main division—that into Media Magna and Media Atropatene—was ancient, Astro-patene being the old home of the Medes, and Media Magna a later conquest; but the early political geography of the country is too obscure to justify us in laying down even this as certain. The minor political divisions are still less distinguishable in the darkness of those ancient times.

From the consideration of the districts which composed the Median territory, we may pass to that of their principal cities, some of which deservedly obtained a very great celebrity. Tho most important of all were the two Ecbatanas—the northern and the southern—which seem to have stood respectively in the position of metropolis to the northern and the southern province. Next to these may be named Rhages, which was probably from early times a very considerable place; while in the third rank may be mentioned Bagistan—rather perhaps a palace than a town—Concobar, Adrapan, Aspadan, Charax, Kudrus, Hyspaostes, Urakagabarna, etc.

The southern Ecbatana or Agbatana—which the Medes and Persians themselves knew as Hagmatan—was situated, as we learn from Polybius and Diodorus, on a plan at the foot of Mont Orontes, a little to the east of the Zagros range. The notices of these authors, combined with those of Eratosthenes, Isidore, Pliny, Arrian, and others, render it as nearly certain as possible that the site was that of the modern town of Hamadan, the name of which is clearly but a slight corruption of the true ancient appellation. [PLATE I., Fig. 2.] Mount Orontes is to be recognized in the modern Elwend or Erwend—a word etymologically identical with Oront-es—which is a long and lofty mountains standing out like a buttress from the Zagros range, with which it is connected towards the north-west, while on every other side it stands isolated, sweeping boldly down upon the flat country at its base. Copious streams descend from the mountain on every side, more particularly to the north-east, where the plain is covered with a carpet of the most luxuriant verdure, diversified with rills, and ornamented with numerous groves of large and handsome forest trees. It is here, on ground sloping slightly away from the roots of the mountain, that the modern town, which lies directly at its foot, is built. The ancient city, if we may believe Diodorus, did not approach the mountain within a mile or a mile and a half. At any rate, if it began where Hamadan now stands, it most certainly extended very much further into the plain. We need not suppose indeed that it had the circumference, or even half the circumference, which the Sicilian romancer assigns to it, since his two hundred and fifty stades would give a probable area of fifty square miles, more than double that of London! Ecbatana is not likely to have been at its most flourishing period a larger city than Nineveh; and we have already seen that Nineveh covered a space, within the walls, of not more than 1800 English acres.

The character of the city and of its chief edifices has, unfortunately, to be gathered almost entirely from unsatisfactory authorities. Hitherto it has been found possible in these volumes to check and correct the statements of ancient writers, which are almost always exaggerated, by an appeal to the incontrovertible evidence of modern surveys and explorations. But the Median capital has never yet attracted a scientific expedition. The travellers by whom it has been visited have reported so unfavorably of its character as a field of antiquarian research that scarcely a spadeful of soil has been dug, either in the city or in its vicinity, with a view to recover traces of the ancient buildings. Scarcely any remains of antiquity are apparent. As the site has never been deserted, and the town has thus been subjected for nearly twenty-two centuries to the destructive ravages of foreign conquerors, and the still more injurious plunderings of native builders, anxious to obtain materials for new edifices at the least possible cost and trouble, the ancient structures have everywhere disappeared from sight, and are not even indicated by mounds of a sufficient size to attract the attention of common observers. Scientific explorers have consequently been deterred from turning their energies in this direction; more promising sites have offered and still offer themselves; and it is as yet uncertain whether the plan of the old town might not be traced and the position of its chief edifices fixed by the means of careful researches conducted by fully competent persons. In this dearth of modern materials we have to depend entirely upon the classical writers, who are rarely trustworthy in their descriptions or measurements, and who, in this instance, labor under the peculiar disadvantage of being mere reporters of the accounts given by others.

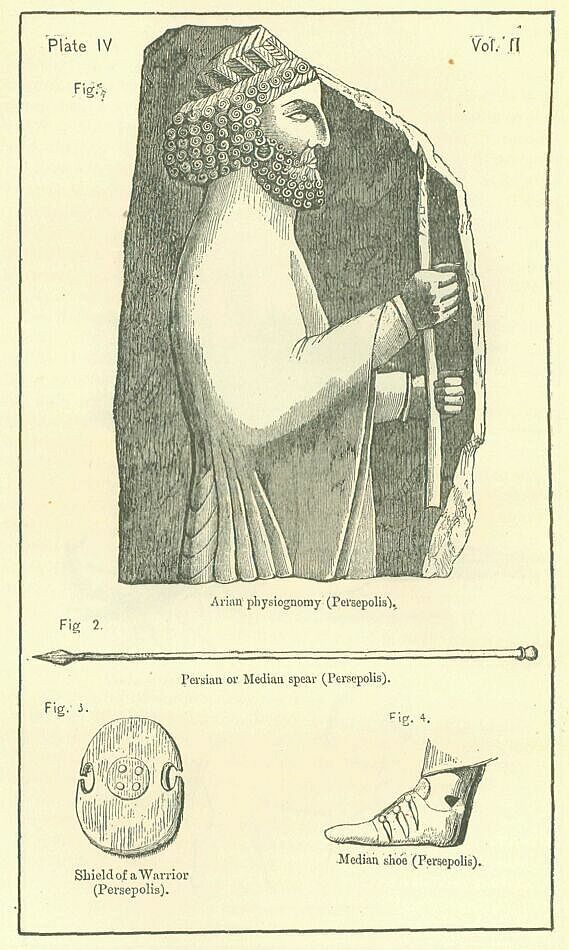

Ecbatana was chiefly celebrated for the magnificence of its palace, a structure ascribed by Diodorus to Semiramis, but most probably constructed originally by Cyaxares, and improved, enlarged, and embellished by the Achaemenian monarchs. According to the judicious and moderate Polybius, who prefaces his account by a protest against exaggeration and over-coloring, the circumference of the building was seven stades, or 1420 yards, somewhat more than four fifths of an English mile. This size, which a little exceeds that of the palace mound at Susa, while it is in its turn a little exceeded by the palatial platform at Persepolis, may well be accepted as probably close to the truth. Judging, however, from the analogy of the above-mentioned palaces, we must conclude that the area thus assigned to the royal residence was far from being entirely covered with buildings. One half of the space, perhaps more, would be occupied by large open courts, paved probably with marble, surrounding the various blocks of buildings and separating them from one another. The buildings themselves may be conjectured to have resembled those of the Achaemenian monarchs at Susa and Persepolis, with the exception, apparently, that the pillars, which formed their most striking characteristic, were for the most part of wood rather than o£ stone. Polybius distinguishes the pillars into two classes, those of the main buildings, and those which skirted the courts, from which it would appear that at Ecbatana the courts were surrounded by colonnades, as they were commonly in Greek and Roman houses. These wooden pillars, all either of cedar or of cypress, supported beams of a similar material, which crossed each other at right angles, leaving square spaces between, which were then filled in with woodwork. Above the whole a roof was placed, sloping at an angle, and composed (as we are told) of silver plates in the shape of tiles. The pillars, beams, and the rest of the woodwork were likewise coated with thin laminse of the precious metals, even gold being used for this purpose to a certain extent.

Such seems to have been the character of the true ancient Median palace, which served probably as a model to Darius and Xerxes when they designed their great palatial edifices at the more southern capitals. In the additions which the palace received under the Achaemenian kings, stone pillars may have been introduced; and hence probably the broken shafts and bases, so nearly resembling the Persepolitan, one of which Sir E. Ker Porter saw in the immediate neighborhood of Hamadan on his visit to that place in 1818. [PLATE I., Fig. 1.] But to judge from the description of Polybius, an older and ruder style of architecture prevailed in the main building, which depended for its effect not on the beauty of architectural forms, but on the richness and costliness of the material. A pillar architecture, so far as appears, began in this part of Asia with the Medes, who, however, were content to use the more readily obtained and more easily worked material of wood; while the Persians afterwards conceived the idea of substituting for these inartificial props the slender and elegant stone shafts which formed the glory of their grand edifices.

At a short distance from the palace was the “Acra,” or citadel, an artificial structure, if we may believe Polybius, and a place of very remarkable strength. Here probably was the treasury, from which Darius Codomanus carried off 7000 talents of silver, when he fled towards Bactria for fear of Alexander. And here, too, may have been the Record Office, in which were deposited the royal decrees and other public documents under the earlier Persian kings. Some travellers are of opinion that a portion of the ancient structure still exists; and there is certainly a ruin on the outskirts of the modern town towards the south, which is known to the natives as “the inner fortress,” and which may not improbably occupy some portion of the site whereon the original citadel stood. But the remains of building which now exist are certainly not of an earlier date than the era of Parthian supremacy, and they can therefore throw no light on the character of the old Median stronghold. It may be thought perhaps that the description which Herodotus gives of the building called by him “the palace of Deioces” should be here applied, and that by its means we might obtain an exact notion of the original structure. But the account of this author is wholly at variance with the natural features of the neighborhood, where there is no such conical hill as he describes, but only a plain surrounded by mountains. It seems, therefore, to be certain that either his description is a pure myth, or that it applies to another city, the Ecbatana of the northern province. It is doubtful whether the Median capital was at any time surrounded with walls. Polybius expressly declares that it was an unwalled place in his day and there is some reason to suspect that it had always been in this condition. The Medes and Persians appear to have been in general content to establish in each town a fortified citadel or stronghold, round which the houses were clustered, without superadding the further defence of a town wall. Ecbatana accordingly seems never to have stood a siege. When the nation which held it was defeated in the open field, the city (unlike Babylon and Nineveh) submitted to the conqueror without a struggle. Thus the marvellous description in the book of Judith, which is internally very improbable, would appear to be entirely destitute of any, even the slightest, foundation in fact.

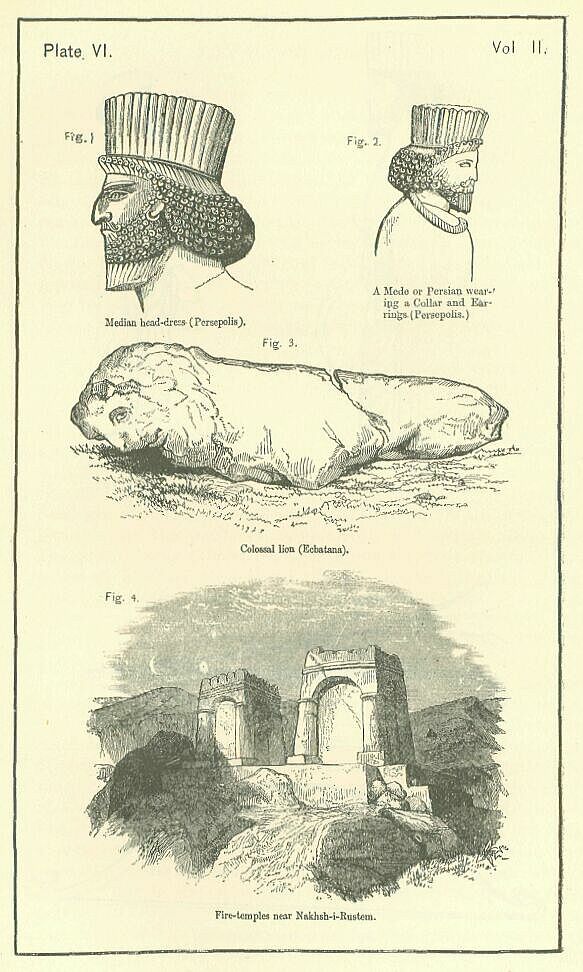

The chief city of northern Media, which bore in later times the names of Gaza, Gazaca, or Canzaca, is thought to have also been called Ecbatana, and to have been occasionally mistaken by the Greeks for the southern or real capital. The description of Herodotus, which is irreconcilably at variance with the local features of the Hamadan site, accords sufficiently with the existing remains of a considerable city in the province of Azerbijan; and it seems certainly to have been a city in these parts which was called by Moses of Chorene “the second Ecbatana, the seven-walled town.” The peculiarity of this place was its situation on and about a conical hill which sloped gently down from its summit to its base, and allowed of the interposition of seven circuits of wall between the plain and the hill’s crest. At the top of the hill, within the innermost circle of the defences, were the Royal Palace and the treasuries; the sides of the hill were occupied solely by the fortifications; and at the base, outside the circuit of the outermost wall, were the domestic and other buildings which constituted the town. According to the information received by Herodotus, the battlements which crowned the walls were variously colored. Those of the outer circle were white, of the next black, of the third scarlet, of the fourth blue, of the fifth orange, of the sixth silver, and of the seventh gold. A pleasing or at any rate a striking effect was thus produced—the citadel, which towered above the town, presenting to the eye seven distinct rows of colors.

If there was really a northern as well as a southern Ecbatana, and if the account of Herodotus, which cannot possibly apply to the southern capital, may be regarded as truly describing the great city of the north, we may with much probability fix the site of the northern town at the modern Takht-i-Suleiman, in the upper valley of the Saruk, a tributary of the Jaghetu. [PLATE I., Fig. 3.] Here alone in northern Media are there important ruins occupying such a position as that which Herodotus describes. Near the head of a valley in which runs the main branch of the Saruk, at the edge of the hills which skirt it to the north, there stands a conical mound projecting into the vale and rising above its surface to the height of 150 feet. The geological formation of the mound is curious in the extreme. It seems to owe its origin entirely to a small lake, the waters of which are so strongly impregnated with calcareous matter that wherever they overflow they rapidly form a deposit which is as hard and firm as natural rock. If the lake was originally on a level with the valley, it would soon have formed incrustations round its edge, which every casual or permanent overflow would have tended to raise; and thus, in the course of ages, the entire hill may have been formed by a mere accumulation of petrefactions. The formation would progress more or less rapidly according to the tendency of the lake to overflow its bounds; which tendency must have been strong until the water reached its present natural level—the level, probably, of some other sheet of water in the hills, with which it is connected by an underground siphon. The lake, which is of an irregular shape, is about 300 paces in circumference. Its water, notwithstanding the quantity of mineral matter held in solution, is exquisitely clear, and not unpleasing to the taste. Formerly it was believed by the natives to be unfathomable; but experiments made in 1837 showed the depth to be no more than 156 feet.

The ruins which at present occupy this remarkable site consist of a strong wall, guarded by numerous bastions and pierced by four gateways, which runs round the brow of the hill in a slightly irregular ellipse, of some interesting remains of buildings within this walled space, and of a few insignificant traces of inferior edifices on the slope between the plain and the summit. As it is not thought that any of these remains are of a date anterior to the Sassanian kingdom, no description will be given of them here. We are only concerned with the Median city, and that has entirely disappeared. Of the seven walls, one alone is to be traced; and even here the Median structure has perished, and been replaced by masonry of a far later age. Excavations may hereafter bring, to light some remnants of the original town, but at present research has done no more than recover for us a forgotten site.

The Median city next in importance to the two Ecbatanas was Raga or Rhages, near the Caspian Gates, almost at the extreme eastern limits of the territory possessed by the Medes.

The great antiquity of this place is marked by its occurrence in the Zendavesta among the primitive settlements of the Arians. Its celebrity during the time of the Empire is indicated by the position which it occupies in the romances of Tobit and Judith. It maintained its rank under the Persians, and is mentioned by Darius Hystaspis as the scene of the struggle which terminated the great Median revolt. The last Darius seems to have sent thither his heavy baggage and the ladies of his court, when he resolved to quit Ecbatana and fly eastward. It has been already noticed that Rhages gave name to a district; and this district maybe certainly identified with the long narrow tract of fertile territory intervening between the Elburz mountain-range and the desert, from about Kasvin to Khaar, or from long. 30° to 52° 30’. The exact site of the city of Rhages within this territory is somewhat doubtful. All accounts place it near the eastern extremity; and as there are in this direction ruins of a town called Rhei or Rhey, it has been usual to assume that they positively fix the locality. But similarity, or even identity, of name is an insufficient proof of a site; and, in the present instance, there are grounds for placing Rhages very much nearer to the Caspian Gates than the position of Rhei. Arrian, whose accuracy is notorious, distinctly states that from the Gates to Rhages was only a single day’s march, and that Alexander accomplished the distance in that time. Now from Rhei to the Girduni Surdurrah pass, which undoubtedly represents the Pylae Cacpise of Arrian, is at least fifty miles, a distance which no army could accomplish in less time than two days. Rhages consequently must have been considerably to the east of Rhei, about half-way between it and the celebrated pass which it was considered to guard. Its probable position is the modern Kaleh Erij, near Veramin, about 23 miles from the commencement of the Surdurrah pass, where there are considerable remains of an ancient town.

In the same neighborhood with Rhages, but closer to the Straits, perhaps on the site now occupied by the ruins known as Uewanukif, or possibly even nearer to the foot of the pass, was the Median city of Charax, a place not to be confounded with the more celebrated city called Gharax Spasini, the birthplace of Dionysius the geographer, which was on the Persian Gulf, at the mouth of the Tigris.

The other Median cities, whose position can be determined with an approach to certainty, were in the western portion of the country, in the range of Zagros, or in the fertile tract between that range and the desert. The most important of these are Bagistan, Adrapan, Concobar, and Aspadan.

Bagistan is described by Isidore as a “city situated on a hill, where there was a pillar and a statue of Semiramis.” Diodorus has an account of the arrival of Semiramis at the place, of her establishing a royal park or paradise in the plain below the mountain, which was watered by an abundant spring, of her smoothing the face of the rock where it descended precipitously upon the low ground, and of her carving on the surface thus obtained her own effigy, with an inscription in Assyrian characters. The position assigned to Bagistan by both writers, and the description of Diodorus, identify the place beyond a doubt with the now famous Behistun, where the plain, the fountain, the precipitous rock, and the scarped surface are still to be seen, through the supposed figure of Semiramis, her pillar, and her inscription have disappeared. [PLATE II., Fig. 1.] This remarkable spot, lying on the direct route between Babylon and Ecbatana, and presenting the unusual combination of a copious fountain, a rich plain, and a rock suitable for sculptures, must have early attracted the attention of the great monarchs who marched their armies through the Zagros range, as a place where they might conveniently set up memorials of their exploits. The works of this kind ascribed by the ancient writers to Semiramis were probably either Assyrian or Babylonian, and (it is most likely) resembled the ordinary monuments which the kings of Babylon and Nineveh delighted to erect in countries newly conquered. The example set by the Mesopotamians was followed by their Arian neighbors, when the supremacy passed into their hands; and the famous mountain, invested by them with a sacred character, was made to subserve and perpetuate their glory by receiving sculptures and inscriptions which showed them to have become the lords of Asia. The practice did not even stop here. When the Parthian kingdom of the Arsacidee had established itself in these parts at the expense of the Seleucidse, the rock was once more called upon to commemorate the warlike triumphs of a new race. Gotarzes, the contemporary of the Emperor Claudius, after defeating his rival Meherdates in the plain between Behistun and Kermanshah, inscribed upon the mountain, which already bore the impress of the great monarchs of Assyria and Persia, a record of his recent victory.

The name of Adrapan occurs only in Isidore, who places it between Bagistan and Ecbatana, at the distance of twelve schoeni—36 Roman or 34 British miles from the latter. It was, he says, the site of an ancient palace belonging to Ecbatana, which Tigranes the Armenian had destroyed. The name and situation sufficiently identify Adrapan with the modern village of Arteman, which lies on the southern face of Elwend near its base, and is well adapted for a royal residence. Here, during the severest winter, when Hamadan and the surrounding country are buried in snow, a warm and sunny climate is to be found; whilst in the summer a thousand rills descending from Elwend diffuse around fertility and fragrance. Groves of trees grow up in rich luxuriance from the well-irrigated soil, whose thick foliage affords a welcome shelter from the heat of the noonday sun. The climate, the gardens, and the manifold blessings of the place are proverbial throughout Persia; and naturally caused the choice of the site for a retired palace, to which the court of Ecbatana might adjourn when either the summer heat and dust or the winter cold made residence in the capital irksome.

In the neighborhood of Adrapan, on the road leading to Bagistan, stood Concobar, which is undoubtedly the modern Kungawar, and perhaps the Chavon of Diodorus. Here, according to the Sicilian historian, Semiramis built a palace and laid out a paradise; and here, in the time of Isidore, was a famous temple of Artemis. Colossal ruins crown the summit of the acclivity on which the town of Kungawar stands, which may be the remains of this latter building; but no trace has been found that can be regarded as either Median or Assyrian.

The Median town of Aspadan, which is mentioned by no writer but Ptolemy, would scarcely deserve notice here, if it were not for its modern celebrity. Aspadan, corrupted into Isfahan, became the capital of Persia, under the Sen kings, who rendered it one of the most magnificent cities of Asia. It is uncertain whether it existed at all in the time of the great Median empire. If so, it was, at best, an outlying town of little consequence on the extreme southern confines of the territory, where it abutted upon Persia proper. The district wherein it lay was inhabited by the Median tribe of the Parastaceni.

Upon the whole it must be allowed that the towns of Media were few and of no great account. The Medes did not love to congregate in large cities, but preferred to scatter themselves in villages over their broad and varied territory. The protection of walls, necessary for the inhabitants of the low Mesopotamian regions, was not required by a people whose country was full of natural fastnesses to which they could readily remove on the approach of danger. Excepting the capital and the two important cities of Gazaca and Rhages, the Median towns were insignificant. Even those cities themselves were probably of moderate dimensions, and had little of the architectural splendor which gives so peculiar an interest to the towns of Mesopotamia. Their principal buildings were in a frail and perishable material, unsuited to bear the ravages of time; they have consequently altogether disappeared, and in the whole of Media modern researches have failed to bring to light a single edifice which can be assigned with any show of probability to the period of the Empire.

The plan adopted in former portions of this work makes it necessary, before concluding this chapter, to glance briefly at the character of the various countries and districts by which Media was bordered—the Caspian district upon the north, Armenia upon the north-west, the Zagros region and Assyria upon the west, Persia proper upon the south, and upon the east Sagartia and Parthia.

North and north-east of the mountain range which under different names skirts the southern shores of the Caspian Sea and curves round its south-western corner, lies a narrow but important strip of territory—the modern Ghilan and Mazanderan. [PLATE II., Fig. 2.] This is a most fertile region, well watered and richly wooded, and forms one of the most valuable portions of the modern kingdom of Persia. At first it is a low flat tract of deep alluvial soil, but little raised above the level of the Caspian; gradually however it rises into swelling hills which form the supports of the high mountains that shut in this sheltered region, a region only to be reached by a very few passes over or through them. The mountains are clothed on this side nearly to their summit with dwarf oaks, or with shrubs and brushwood; while, lower down, their flanks are covered with forests of elms, cedars, chestnuts, beeches, and cypress trees. The gardens and orchards of the natives are of the most superb character; the vegetation is luxuriant; lemons, oranges, peaches, pomegranates, besides other fruits, abound; rice, hemp, sugar-canes, mulberries are cultivated with success; vines grow wild; and the valleys are strewn with flowers of rare fragrance, among which may be noted the rose, the honeysuckle, and the sweetbrier. Nature, however, with her usual justice, has balanced these extraordinary advantages with peculiar drawbacks; the tiger, unknown in any other part of Western Asia, here lurks in the thickets, ready to spring at any moment on the unwary traveller; inundations are frequent, and carry desolation far and wide; the waters, which thus escape from the river beds, stagnate in marshes, and during the summer and autumn heats pestilential exhalations arise, which destroy the stranger, and bring even the acclimatized native to the brink of the grave. The Persian monarch chooses the southern rather than the northern side of the mountains for the site of his capital, preferring the keen winter cold and dry summer heat of the high and almost waterless plateau to the damp and stifling air of the low Caspian region.

The narrow tract of which this is a description can at no time have sheltered a very numerous or powerful people. During the Median period, and for many ages afterwards, it seems to have been inhabited by various petty tribes of predatory habits—Cadusians, Mardi, Tapyri, etc.,—who passed their time in petty quarrels among themselves, and in plundering raids upon their great southern neighbor. Of these tribes the Cadusians alone enjoyed any considerable reputation. They were celebrated for their skill with the javelin—a skill probably represented by the modern Persian use of the djereed. According to Diodorus, they were engaged in frequent wars with the Median kings, and were able to bring into the field a force of 200,000 men! Under the Persians they seem to have been considered good soldiers, and to have sometimes made a struggle for independence. But there is no real reason to believe that they were of such strength as to have formed at any time a danger to the Median kingdom, to which it is more probable that they generally acknowledged a qualified subjection.

The great country of Armenia, which lay north-west and partly north of Media, has been generally described in the first volume; but a few words will be here added with respect to the more eastern portion, which immediately bordered upon the Median territory. This consisted of two outlying districts, separated from the rest of the country, the triangular basin of Lake Van, and the tract between the Kur and Aras rivers—the modern Karabagh and Erivan. The basin of Lake Van, surrounded by high ranges, and forming the very heart of the mountain system of this part of Asia, is an isolated region, a sort of natural citadel, where a strong military power would be likely to establish itself. Accordingly it is here, and here alone in all Armenia, that we find signs of the existence, during the Assyrian and Median periods, of a great organized monarchy.

The Van inscriptions indicate to us a line of kings who bore sway in the eastern Armenia—the true Ararat—and who were both in civilization and in military strength far in advance of any of the other princes who divided among them the Armenian territory. The Van monarchs may have been at times formidable enemies of the Medes. They have left traces of their dominion, not only on the tops of the mountain passes which lead into the basin of Lake Urumiyeh, but even in the comparatively low plain of Miyandab on the southern shore of that inland sea. It is probable from this that they were at one time masters of a large portion of Media Atropatene, and the very name of Urumiyeh, which still attaches to the lake, may have been given to it from one of their tribes. In the tract between the Kur and Aras, on the other hand, there is no sign of the early existence of any formidable power. Here the mountains are comparatively low, the soil is fertile, and the climate temperate. The character of the region would lead its inhabitants to cultivate the arts of peace rather than those of war, and would thus tend to prevent them from being formidable or troublesome to their neighbors.

The Zagros region, which in the more ancient times separated between Media and Assyria, being inhabited by a number of independent tribes, but which was ultimately absorbed into the more powerful country, requires no notice here, having been sufficiently described among the tracts by which Assyria was bordered. At first a serviceable shield to the weak Arian tribes which were establishing themselves along its eastern base upon the high plateau, it gradually passed into their possession as they increased in strength, and ultimately became a main nursery of their power, furnishing to their armies vast numbers both of men and horses. The great horse pastures, from which the Medes first and the Persians afterwards, supplied their numerous and excellent cavalry, were in this quarter; and the troops which it furnished—hardy mountaineers accustomed to brave the severity of a most rigorous climate—must have been among the most effective of the Median forces.

On the south Media was bounded by Persia proper—a tract which corresponded nearly with the modern province of Farsistan. The complete description of this territory, the original seat of the Persian nation, belongs to a future volume of this work, which will contain an account of the “Fifth Monarchy.” For the present it is sufficient to observe that the Persian territory was for the most part a highland, very similar to Media, from which it was divided by no strongly marked line or natural boundary. The Persian mountains are a continuation of the Zagros chain, and Northern Persia is a portion—the southern portion—of the same great plateau, whose western and north-western skirts formed the great mass of the Median territory. Thus upon this side Media was placed in the closest connection with an important country, a country similar in character to her own, where a hardy race was likely to grow up, with which she might expect to have difficult contests.

Finally, towards the east lay the great salt desert, sparsely inhabited by various nomadic races, among which the most important were the Cossseans and the Sagartians. To the latter people Herodotus seems to assign almost the whole of the sandy region, since he unites them with the Sarangians and Thamanseans on the one hand, with the Utians and Mycians upon the other. They were a wild race, probably of Arian origin, who hunted with the lasso over the great desert mounted on horses, and could bring into the field a force of eight or ten thousand men. Their country, a waste of sand and gravel, in parts thickly encrusted with salt, was impassable to an army, and formed a barrier which effectively protected Media along the greater portion of her eastern frontier. Towards the extreme north-east the Sagartians were replaced by the Cossseans and the Parthians, the former probably the people of the Siah-Koh mountain, the latter the inhabitants of the tract known now as the Atak, or “skirt,” which extends along the southern flank of the Elburz range from the Caspian Gates nearly to Herat, and is capable of sustaining a very considerable population. The Cossseans were plunderers, from whose raids Media suffered constant annoyance; but they were at no time of sufficient strength to cause any serious fear. The Parthians, as we learn from the course of events, had in them the materials of a mighty people; but the hour for their elevation and expansion was not yet come, and the keenest observer of Median times could scarcely have perceived in them the future lords of Western Asia. From Parthia, moreover, Media was divided by the strong rocky spur which runs out from the Elburz into the desert in long. 52° 10’ nearly, over which is the narrow pass already mentioned as the Caspian Gates. Thus Media on most sides was guarded by the strong natural barriers of seas, mountains, and deserts lying open only on the south, where she adjoined upon a kindred people. Her neighbors were for the most part weak in numbers, though warlike. Armenia, however, to the north-west, Assyria to the west, and Persia to the south, were all more or less formidable. A prescient eye might have foreseen that the great struggles of Media would be with these powers, and that if she attained imperial proportions it must be by their subjugation or absorption.

Media, like Assyria, is a country of such extent and variety that, in order to give a correct description of its climate, we must divide it into regions. Azerbijan, or Atropatene, the most northern portion, has a climate altogether cooler than the rest of Media; while in the more southern division of the country there is a marked difference between the climate of the east and of the west, of the tracts lying on the high plateau and skirting the Great Salt Desert, and of those contained within or closely abutting upon the Zagros mountain range. The difference here is due to the difference of physical conformation, which is as great as possible, the broad mountainous plains about Kasvin, Koum, and Kashan, divided from each other by low rocky ridges, offering the strongest conceivable contrast to the perpetual alternations of mountain and valley, precipitous height and deep wooded glen, which compose the greater part of the Zagros region.

The climate of Azerbijan is temperate and pleasant, though perhaps somewhat overwarm, in summer; while in winter it is bitterly severe, colder than that of almost any other region in the same latitude. This extreme rigor seems to be mainly owing to elevation, the very valleys and valley plains of the tract being at a height of from 4000 to 5000 feet above the sea level. Frost commonly sets in towards the end of November—or at latest early in December; snow soon covers the ground to the depth of several feet; the thermometer falls below zero; the sun shines brightly except when from time to time fresh deposits of snow occur; but a keen and strong wind usually prevails, which is represented as “cutting like a sword,” and being a very “assassin of life.” Deaths from cold are of daily occurrence; and it is impossible to travel without the greatest risk. Whole companies or caravans occasionally perish beneath the drift, when the wind is violent, especially if a heavy fall happen to coincide with one of the frequent easterly gales. The severe weather commonly continues till March, when travelling becomes possible, but the snow remains on much of the ground till May, and on the mountains still longer. The spring, which begins in April, is temperate and delightful; a sudden burst of vegetation succeeds to the long winter lethargy; the air is fresh and balmy, the sun pleasantly warm, the sky generally cloudless. In the month of May the heat increases—thunder hangs in the air—and the valleys are often close and sultry. Frequent showers occur, and the hail-storms are sometimes so violent as to kill the cattle in the fields. As the summer advances the heats increase, but the thermometer rarely reaches 90° in the shade, and except in the narrow valleys the air is never oppressive. The autumn is generally very fine. Foggy mornings are common; but they are succeeded by bright pleasant days, without wind or rain. On the whole the climate is pronounced healthy, though somewhat trying to Europeans, who do not readily adapt themselves to a country where the range of the thermometer is as much as 90° or 100°. In the part of Media situated on the great plateau—the modern Irak Ajemi—in which are the important towns of Teheran, Isfahan, Hamadan, Kashan, Kasvin, and Koum. the climate is altogether warmer than in Azerbijan, the summers being hotter, and the winters shorter and much less cold. Snow indeed covers the ground for about three months, from early in December till March; but the thermometer rarely shows more than ten or twelve degrees of frost, and death from cold is uncommon. The spring sets in about the beginning of March, and is at first somewhat cool, owing to the prevalence of the baude caucasan or north wind,a which blows from districts where the snow still lies. But after a little time the weather becomes delicious; the orchards are a mass of blossom; the rose gardens come into bloom; the cultivated lands are covered with springing crops; the desert itself wears a light livery of green. Every sense is gratified; the nightingale bursts out with a full gush of song; the air plays softly upon the cheek, and comes loaded with fragrance. Too soon, however, this charming time passes away, and the summer heats begin, in some places as early as June 18 The thermometer at midday rises to 90 or 100 degrees. Hot gusts blow from the desert, sometimes with great violence. The atmosphere is described as choking; and in parts of the plateau it is usual for the inhabitants to quit their towns almost in a body, and retire for several months into the mountains. This extreme heat is, however, exceptional; in most parts of the plateau the summer warmth is tempered by cool breezes from the surrounding mountains, on which there is always a good deal of snow. At Hamadan, which, though on the plain, is close to the mountains, the thermometer seems scarcely ever to rise above 90°, and that degree of heat is attained only for a few hours in the day. The mornings and evenings are cool and refreshing; and altogether the climate quite justifies the choice of the Persian monarchs, who selected Ecbatana for their place of residence during the hottest portion of the year. Even at Isfahan, which is on the edge of the desert, the heat is neither extreme nor prolonged. The hot gusts which blow from the east and from the south raise the temperature at times nearly to a hundred degrees; but these oppressive winds alternate with cooler breezes from the west, often accompanied by rain; and the average highest temperature during the day in the hottest month, which is August, does not exceed 90°.

A peculiarity in the climate of the plateau which deserves to be noticed is the extreme dryness of the atmosphere. In summer the rains which fall are slight, and they are soon absorbed by the thirsty soil. There is a little dew at nights, especially in the vicinity of the few streams; but it disappears with the first hour of sunshine, and the air is left without a particle of moisture. In winter the dryness is equally great; frost taking the place of heat, with the same effect upon the atmosphere. Unhealthy exhalations are thus avoided, and the salubrity of the climate is increased; but the European will sometimes sigh for the soft, balmy airs of his own land, which have come flying over the sea, and seem to bring their wings still dank with the ocean spray.

Another peculiarity of this region, produced by the unequal rarefaction of the air over its different portions, is the occurrence, especially in spring and summer, of sudden gusts, hot or cold, which blow with great violence. These gusts are sometimes accompanied with, whirlwinds, which sweep the country in different directions, carrying away with them leaves, branches, stubble, sand, and other light substances, and causing great annoyance to the traveller. They occur chiefly in connection with a change of wind, and are no doubt consequent on the meeting of two opposite currents. Their violence, however, is moderate, compared with that of tropical tornadoes, and it is not often that they do any considerable damage to the crops over which they sweep.

One further characteristic of the flat region may be noticed. The intense heat of the summer sun striking on the dry sand or the saline efflorescence of the desert throws the air over them into such a state of quivering undulation as produces the most wonderful and varying effects, distorting the forms of objects, and rendering the most familiar strange and hard to be recognized. A mud bank furrowed by the rain will exhibit the appearance of a magnificent city, with columns, domes, minarets, and pyramids; a few stunted bushes will be transformed into a forest of stately trees; a distant mountain will, in the space of a minute, assume first the appearance of a lofty peak, then swell out at the top, and resemble a mighty mushroom, next split into several parts, and finally settle down into a flat tableland. Occasionally, though not very often that semblance of water is produced which Europeans are are apt to suppose the usual effect of mirage. The images of objects are reflected at their base in an inverted position; the desert seems converted into a vast lake; and the thirsty traveller, advancing towards it, finds himself the victim of an illusion, which is none the less successful because he has been a thousand times forewarned of its deceptive power.

In the mountain range or Zagros and the tracts adjacent to it, the climate, owing to the great differences of elevation, is more varied than in the other parts of the ancient Media. Severe cold prevails in the higher mountain regions for seven months out of the twelve, while during the remaining five the heat is never more than moderate. In the low valleys, on the contrary, and in other favored situations, the winters are often milder than on the plateau; while in the summers, if the heat is not greater, at any rate it is more oppressive. Owing to the abundance of the streams and proximity of the melting snows, the air is moist; and the damp heat, which stagnates in the valleys, broods fever and ague. Between these extremes of climate and elevation, every variety is to be found; and, except in winter, a few hours’ journey will almost always bring the traveller into a temperate region.

In respect of natural productiveness, Media (as already observed) differs exceedingly in different, and even in adjacent, districts. The rocky ridges of the great plateau, destitute of all vegetable mold, are wholly bare and arid, admitting not the slightest degree of cultivation. Many of the mountains of Azerbijan, naked, rigid, and furrowed, may compare even with these desert ranges for sterility. The higher parts of Zagros and Elburz are sometimes of the same character; but more often they are thickly clothed with forests, affording excellent timber and other valuable commodities. In the Elburz pines are found near the summit, while lower down there occur, first the wild almond and the dwarf oak, and then the usual timber-trees of the country, the Oriental plane, the willow, the poplar, and the walnut. The walnut grows to a large size both here and in Azerbijan, but the poplar is the wood most commonly used for building purposes. In Zagros, besides most of these trees, the ash and the terebinth or turpentine-tree are common; the oak bears gall-nuts of a large size; and the gum-tragacanth plant frequently clothes the mountain-sides. The valleys of this region are full of magnificent orchards, as are the low grounds and more sheltered nooks of Azerbijan. The fruit-trees comprise, besides vines and mulberries, the apple, the pear, the quince, the plum, the cherry, the almond, the nut, the chestnut, the olive, the peach, the nectarine, and the apricot.

On the plains of the high plateau there is a great scarcity of vegetation. Trees of a large size grow only in the few places which are well watered, as in the neighborhood of Hamadan, Isfahan, and in a less degree of Kashan. The principal tree is the Oriental plane, which flourishes together with poplars and willows along the water-courses; cypresses also grow freely; elms and cedars are found, and the orchards and gardens contain not only the fruit-trees mentioned above, but also the jujube, the cornel, the filbert, the medlar, the pistachio nut, the pomegranate, and the fig. Away from the immediate vicinity of the rivers and the towns, not a tree, scarcely a bush, is to be seen. The common thorn is indeed tolerably abundant in a few places; but elsewhere the tamarisk and a few other sapless shrubs are the only natural products of this bare and arid region.

In remarkable contrast with the natural barrenness of this wide tract are certain favored districts in Zagros and Azerbijan, where the herbage is constant throughout the summer, and sometimes only too luxuriant. Such are the rich and extensive grazing grounds of Khawah and Alishtar, near Kermanshah, the pastures near Ojan and Marand, and the celebrated Chowal Moghan or plain of Moghan, on the lower course of the Araxes river, where the grass is said to grow sufficiently high to cover a man on horseback. These, however, are rare exceptions to the general character of the country, which is by nature unproductive, and scarcely deserving even of the qualified encomium of Strabo.

Still Media, though deficient in natural products, is not ill adapted for cultivation. The Zagros valleys and hillsides produce under a very rude system of agriculture, besides the fruits already noticed, rice, wheat, barley, millet, sesame, Indian corn, cotton, tobacco, mulberries, cucumbers, melons, pumpkins, and the castor-oilplant. In Azerbijan the soil is almost all cultivable, and if ploughed and sown will bring good crops of the ordinary kinds of grain. Even on the side of the desert, where Nature has shown herself most niggardly, and may seem perhaps to deserve the reproach of Cicero, that she behaves as a step mother to a man rather than as a mother, a certain amount of care and scientific labor may render considerable tracts fairly productive. The only want of this region is water; and if the natural deficiency of this necessary fluid can be anyhow supplied, all parts of the plateau will bear crops, except those which form the actual Salt Desert. In modern, and still more in ancient times, this fact has been clearly perceived, and an elaborate system of artifical irrigation, suitable to the peculiar circumstances of the country, has been very widely established. The system of kanats, as they are called at the present day, aims at utilizing to the uttermost all the small streams and rills which descend towards the desert from the surrounding mountains, and at conveying as far as possible into the plain the spring water, which is the indispensable condition of cultivation in a country where—except for a few days in the spring and autumn—rain scarcely ever falls. As the precious element would rapidly evaporate if exposed to the rays of the summer sun, the Iranian husbandman carries his conduit underground, laboriously tunnelling through the stiff argillaceous soil, at a depth of many feet below the surface. The mode in which he proceeds is as follows. At intervals along the line of his intended conduit he first sinks shafts, which he then connects with one another by galleries, seven or eight feet in height, giving his galleries a slight incline, so that the water may run down them freely, and continuing them till he reaches a point where he wishes to bring the water out upon the surface of the plain. Here and there, at the foot of his shafts, he digs wells, from which the fluid can readily be raised by means of a bucket and a windlass; and he thus brings under cultivation a considerable belt of land along the whole line of the kanat, as well as a large tract at its termination. These conduits, on which the cultivation of the plateau depends, were established at so remote a date that they were popularly ascribed to the mythic Semiramis, the supposed wife of Ninus. It is thought that in ancient times they were longer and more numerous than at present, when they occur only occasionally, and seldom extend more than a few miles from the base of the hills.

By help of the irrigation thus contrived, the great plateau of Iran will produce good crops of grain, rice, wheat, barley, Indian corn, doura, millet, and sesame. It will also bear cotton, tobacco, saffron, rhubarb, madder, poppies which give a good opium, senna, and assafoetida. Its garden vegetables are excellent, and include potatoes, cabbages, lentils, kidney-beans, peas, turnips, carrots, spinach, beetroot, and cucumbers. The variety of its fruit-trees has been already noticed. The flavor of their produce is in general good, and in some cases surpassingly excellent. No quinces are so fine as those of Isfahan, and no melons have a more delicate flavor. The grapes of Kasvin are celebrated, and make a remarkably good wine.

Among the flowers of the country must be noted, first of all, its roses, which flourish in the most luxuriant abundance, and are of every variety of hue. The size to which the tree will grow is extraordinary, standards sometimes exceeding the height of fourteen or fifteen feet. Lilacs, jasmines, and many other flowering shrubs are common in the gardens, while among wild flowers may be noticed hollyhocks, lilies, tulips, crocuses, anemones, lilies of the valley, fritillaries, gentians, primroses, convolvuluses, chrysanthemums, heliotropes, pinks, water-lilies, ranunculuses, jonquils, narcissuses, hyacinths, mallows, stocks, violets, a fine campanula (Michauxia levigata), a mint (Nepeta longiflora), several sages, salsolas, and fagonias. In many places the wild flowers during the spring months cover the ground, painting it with a thousand dazzling or delicate hues.

The mineral products of Media are numerous and valuable. Excellent stone of many kinds abounds in almost every part of the country, the most important and valuable being the famous Tabriz marble. This curious substance appears to be a petrifaction formed by natural springs, which deposit carbonate of lime in large quantities. It is found only in one place, on the flanks of the hills, not far from the Urumiyeh lake. The slabs are used for tombstones, for the skirting of rooms, and for the pavements of baths and palaces; when cut thin they often take the place of glass in windows, being semi-transparent. The marble is commonly of a pale yellow color, but occasionally it is streaked with red, green, or copper-colored veins.

In metals the country is thought to be rich, but no satisfactory examination of it has been as yet made. Iron, copper, and native steel are derived from mines actually at work; while Europeans have observed indications of lead, arsenic, and antimony in Azerbijan, in Kurdistan, and in the rocky ridges which intersect the desert. Tradition speaks of a time when gold and silver were procured from mountains near Takht-i-Suleman, and it is not unlikely that they may exist both there and in the Zagros range. Quartz, the well-known matrix of the precious metal, abounds in Kurdistan.

Of all the mineral products, none is more abundant than salt. On the side of the desert, and again near Tabriz at the mouth of the Aji Su, are vast plains which glisten with the substance, and yield it readily to all who care to gather it up. Saline springs and streams are also numerous, from which salt can be obtained by evaporation. But, besides these sources of supply, rock salt is found in places, and this is largely quarried, and is preferred by the natives.

Other important products of the earth are saltpetre, which is found in the Elburz, and in Azerbijan; sulphur, which abounds in the same regions, and likewise on the high plateau; alum, which is quarried near Tabriz; naphtha and gypsum, which are found in Kurdistan; and talc, which exists in the mountains near Koum, in the vicinity of Tabriz, and probably in other places.

The chief wild animals which have been observed within the limits of the ancient Media are the lion, the tiger, the leopard, the bear, the beaver, the jackal, the wolf, the wild ass, the ibex or wild goat, the wild sheep, the stag, the antelope, the wild boar, the fox, the hare, the rabbit, the ferret, the rat, the jerboa, the porcupine, the mole, and the marmot. The lion and tiger are exceedingly rare; they seem to be found only in Azerbijan, and we may perhaps best account for their presence there by considering that a few of these animals occasionally stray out of Mazanderan, which is their only proper locality in this part of Asia. Of all the beasts, the most abundant are the stag and the wild goat, which are numerous in the Elburz, and in parts of Azerbijan, the wild boar, which abounds both in Azerbijan, and in the country about Hamadan, and the jackal, which is found everywhere. Bears flourish in Zagros, antelopes in Azerbijan, in the Elburz, and on the plains near Sultaniyeh. The wild ass is found only in the desert parts of the high plateau; the beaver only in Lake Zeribar, near Sulefmaniyeh.

The Iranian wild ass differs in some respects from the Mesopotamian. His skin is smooth, like that of a deer, and of a reddish color, the belly and hinder parts partaking of a silvery gray; his head and ears are large and somewhat clumsy; but his neck is fine, and his legs are beautifully slender. His mane is short and black, and he has a black tuft at the end of his tail, but no dark line runs along his back or crosses his shoulders. The Persians call him the gur-khur, and chase him with occasional success, regarding his flesh as a great delicacy. He appears to be the Asinus onager of naturalists, a distinct species from the Asinus hemippus of Mesopotamia, and the Asinus hemionus of Thibet and Tartary.

It is doubtful whether some kind of wild cattle does not still inhabit the more remote tracts of Kurdistan. The natives mention among the animals of their country “the mountain ox;” and though it has been suggested that the beast intended is the elk, it is perhaps as likely to be the Aurochs, which seems certainly to have been a native of the adjacent country of Mesopotamia in ancient times. At any rate, until Zagros has been thoroughly explored by Europeans, it must remain uncertain what animal is meant. Meanwhile we may be tolerably sure that, besides the species enumerated, Mount Zagros contains within its folds some large and rare ruminant.

Among the birds the most remarkable are the eagle, the bustard, the pelican, the stork, the pheasant, several kinds of partridges, the quail, the woodpecker, the bee-eater, the hoopoe, and the nightingale. Besides these, doves and pigeons, both wild and tame, are common; as are swallows, goldfinches, sparrows, larks, blackbirds, thrushes, linnets, magpies, crows, hawks, falcons, teal, snipe, wild ducks, and many other kinds of waterfowl. The most common partridge is a red-legged species (Caccabis chukar of naturalists), which is unable to fly far, and is hunted until it drops. Another kind, common both in Azerbijan and in the Elburz, is the black-breasted partridge (Perdix nigra)—a bird not known in many countries. Besides these, there is a small gray partridge in the Zagros range, which the Kurds call seslca. The bee-eater (Merops Persicus) is rare. It is a bird of passage, and only visits Media in the autumn, preparatory to retreating into the warm district of Mazandoran for the winter months. The hoopoe (Upupa) is probably still rarer, since very few travellers mention it. The woodpecker is found in Zagros, and is a beautiful bird, red and gray in color.

Media is, on the whole, but scantily provided with fish. Lake Urumiyeh produces none, as its waters are so salt that they even destroy all the river-fish which enter them. Salt streams, like the Aji Su, are equally unproductive, and the fresh-water rivers of the plateau fall so low in summer that fish cannot become numerous in them. Thus it is only in Zagros, in Azerbijan, and in the Elburz, that the streams furnish any considerable quantity. The kinds most common are barbel, carp, dace, bleak, and gudgeon. In a comparatively few streams, more especially those of Zagros, trout are found, which are handsome and of excellent quality. The river of Isfahan produces a kind of crayfish, which is taken in the bushes along its banks, and is very delicate eating.

It is remarkable that fish are caught not only in the open streams of Media, but also in the kanats or underground conduits, from which the light of day is very nearly excluded. They appear to be of one sort only, viz., barbel, but are abundant, and often grow to a considerable size. Chardin supposed them to be unfit for food; but a later observer declares that, though of no great delicacy, they are “perfectly sweet and wholesome.”

Of reptiles, the most common are snakes, lizards, and tortoises. In the long grass of the Moghan district, on the lower course of the Araxes, the snakes are so numerous and venomous that many parts of the plain are thereby rendered impassable in the summer-time. A similar abundance of this reptile near the western entrance of the Girduni Siyaluk pass induces the natives to abstain from using it except in winter. Lizards of many forms and hues disport themselves about the rocks and stones, some quite small, others two feet or more in length. They are quite harmless, and appear to be in general very tame. Land tortoises are also common in the sandy regions. In Kurdistan there is a remarkable frog, with a smooth skin and of an apple-green color, which lives chiefly in trees, roosting in them at night, and during the day employing itself in catching flies and locusts, which it strikes with its fore paw, as a cat strikes a bird or a mouse.

Among insects, travellers chiefly notice the mosquito, which is in many places a cruel torment; the centipede, which grows to an unusual size; the locust, of which there is more than one variety; and the scorpion, whose sting is sometimes fatal.

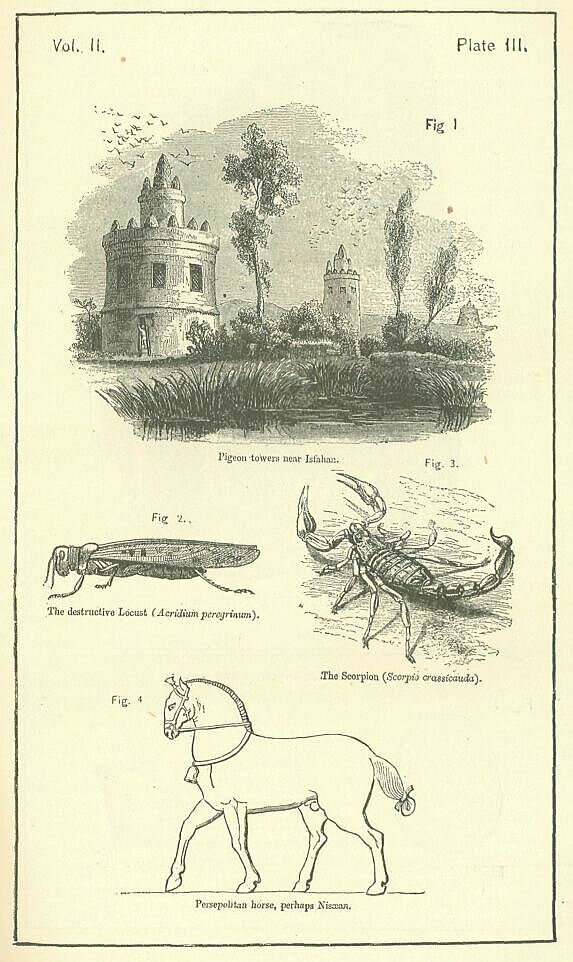

The destructive locust (the Acridium peregrinum, probably) comes suddenly into Kurdistan and southern Media in clouds that obscure the air, moving with a slow and steady flight and with a sound like that of heavy rain, and settling in myriads on the fields, the gardens, the trees, the terraces of the houses, and even the streets, which they sometimes cover completely. Where they fall, vegetation presently disappears; the leaves, and even the stems of the plants, are devoured; the labors of the husbandman through many a weary month perish in a day; and the curse of famine is brought upon the land which but now enjoyed the prospect of an abundant harvest. It is true that the devourers are themselves devoured to some extent by the poorer sort of people; but the compensation is slight and temporary; in a few days, when all verdure is gone, either the swarms move to fresh pastures, or they perish and cover the fields with their dead bodies, while the desolation which they have created continues. [PLATE III., Fig. 2.]