Title: The Lamp in the Desert

Author: Ethel M. Dell

Release date: October 16, 2004 [eBook #13763]

Most recently updated: December 18, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Audrey Longhurst, Gregory Smith, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Audrey Longhurst, Gregory Smith,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

A great roar of British voices pierced the jewelled curtain of the Indian night. A toast with musical honours was being drunk in the sweltering dining-room of the officers' mess. The enthusiastic hubbub spread far, for every door and window was flung wide. Though the season was yet in its infancy, the heat was intense. Markestan had the reputation in the Indian Army for being one of the hottest corners in the Empire in more senses than one, and Kurrumpore, the military centre, had not been chosen for any especial advantages of climate. So few indeed did it possess in the eyes of Europeans that none ever went there save those whom an inexorable fate compelled. The rickety, wooden bungalows scattered about the cantonment were temporary lodgings, not abiding-places. The women of the community, like migratory birds, dwelt in them for barely four months in the year, flitting with the coming of the pitiless heat to Bhulwana, their little paradise in the Hills. But that was a twenty-four hours' journey away, and the men had to be content with an occasional week's leave from the depths of their inferno, unless, as Tommy Denvers put it, they were lucky enough to go sick, in which case their sojourn in paradise was prolonged, much to the delight of the angels.

But on that hot night the annual flitting of the angels had not yet come to pass, and notwithstanding the heat the last dance of the season was to take place at the Club House. The occasion was an exceptional one, as the jovial sounds that issued from the officers' mess-house testified. Round after round of cheers followed the noisy toast, filling the night with the merry uproar that echoed far and wide. A confusion of voices succeeded these; and then by degrees the babel died down, and a single voice made itself heard. It spoke with easy fluency to the evident appreciation of its listeners, and when it ceased there came another hearty cheer. Then with jokes and careless laughter the little company of British officers began to disperse. They came forth in lounging groups on to the steps of the mess-house, the foremost of them—Tommy Denvers—holding the arm of his captain, who suffered the familiarity as he suffered most things, with the utmost indifference. None but Tommy ever attempted to get on familiar terms with Everard Monck. He was essentially a man who stood alone. But the slim, fair-haired young subaltern worshipped him openly and with reason. For Monck it was who, grimly resolute, had pulled him through the worst illness he had ever known, accomplishing by sheer force of will what Ralston, the doctor, had failed to accomplish by any other means. And in consequence and for all time the youngest subaltern in the mess had become Monck's devoted adherent.

They stood together for a moment at the top of the steps while Monck, his dark, lean face wholly unresponsive and inscrutable, took out a cigar. The night was a wonderland of deep spaces and glittering stars. Somewhere far away a native tom-tom throbbed like the beating of a fevered pulse, quickening spasmodically at intervals and then dying away again into mere monotony. The air was scentless, still, and heavy.

"It's going to be deuced warm," said Tommy.

"Have a smoke?" said Monck, proffering his case.

The boy smiled with swift gratification. "Oh, thanks awfully! But it's a shame to hurry over a good cigar, and I promised Stella to go straight back."

"A promise is a promise," said Monck. "Have it later!" He added rather curtly, "I'm going your way myself."

"Good!" said Tommy heartily. "But aren't you going to show at the Club House? Aren't you going to dance?"

Monck tossed down his lighted match and set his heel on it. "I'm keeping my dancing for to-morrow," he said. "The best man always has more than enough of that."

Tommy made a gloomy sound that was like a groan and began to descend the steps by his side. They walked several paces along the dim road in silence; then quite suddenly he burst into impulsive speech.

"I'll tell you what it is, Monck!"

"I shouldn't," said Monck.

Tommy checked abruptly, looking at him oddly, uncertainly. "How do you know what I was going to say?" he demanded.

"I don't," said Monck.

"I believe you do," said Tommy, unconvinced.

Monck blew forth a cloud of smoke and laughed in his brief, rather grudging way. "You're getting quite clever for a child of your age," he observed. "But don't overdo it, my son! Don't get precocious!"

Tommy's hand grasped his arm confidentially. "Monck, if I don't speak out to someone, I shall bust! Surely you don't mind my speaking out to you!"

"Not if there's anything to be gained by it," said Monck.

He ignored the friendly, persuasive hand on his arm, but yet in some fashion Tommy knew that it was not unwelcome. He kept it there as he made reply.

"There isn't. Only, you know, old chap, it does a fellow good to unburden himself. And I'm bothered to death about this business."

"A bit late in the day, isn't it?" suggested Monck.

"Oh yes, I know; too late to do anything. But," Tommy spoke with force, "the nearer it gets, the worse I feel. I'm downright sick about it, and that's the truth. How would you feel, I wonder, if you knew your one and only sister was going to marry a rotter? Would you be satisfied to let things drift?"

Monck was silent for a space. They walked on over the dusty road with the free swing of the conquering race. One or two 'rickshaws met them as they went, and a woman's voice called a greeting; but though they both responded, it scarcely served as a diversion. The silence between them remained.

Monck spoke at last, briefly, with grim restraint. "That's rather a sweeping assertion of yours. I shouldn't repeat it if I were you."

"It's true all the same," maintained Tommy. "You know it's true."

"I know nothing," said Monck. "I've nothing whatever against Dacre."

"You've nothing in favour of him anyway," growled Tommy.

"Nothing particular; but I presume your sister has." There was just a hint of irony in the quiet rejoinder.

Tommy winced. "Stella! Great Scott, no! She doesn't care the toss of a halfpenny for him. I know that now. She only accepted him because she found herself in such a beastly anomalous position, with all the spiteful cats of the regiment arrayed against her, treating her like a pariah."

"Did she tell you so?" There was no irony in Monck's tone this time. It fell short and stern.

Again Tommy glanced at him as one uncertain. "Not likely," he said.

"Then why do you make the assertion? What grounds have you for making the assertion?" Monck spoke with insistence as one who meant to have an answer.

And the boy answered him, albeit shamefacedly. "I really can't say, Monck. I'm the sort of fool that sees things without being able to explain how. But that Stella has the faintest spark of real love for that fellow Dacre,—well, I'd take my dying oath that she hasn't."

"Some women don't go in for that sort of thing," commented Monck dryly.

"Stella isn't that sort of woman." Hotly came Tommy's defence. "You don't know her. She's a lot deeper than I am."

Monck laughed a little. "Oh, you're deep enough, Tommy. But you're transparent as well. Now your sister on the other hand is quite inscrutable. But it is not for us to interfere. She probably knows what she is doing—very well indeed."

"That's just it. Does she know? Isn't she taking a most awful leap in the dark?" Keen anxiety sounded in Tommy's voice. "It's been such horribly quick work, you know. Why, she hasn't been out here six weeks. It's a shame for any girl to marry on such short notice as that. I said so to her, and she—she laughed and said, 'Oh, that's beggar's choice! Do you think I could enjoy life with your angels in paradise in unmarried bliss? I'd sooner stay down in hell with you.' And she'd have done it too, Monck. And it would probably have killed her. That's partly how I came to know."

"Haven't the women been decent to her?" Monck's question fell curtly, as if the subject were one which he was reluctant to discuss.

Tommy looked at him through the starlight. "You know what they are," he said bluntly. "They'd hunt anybody if once Lady Harriet gave tongue. She chose to eye Stella askance from the very outset, and of course all the rest followed suit. Mrs. Ralston is the only one in the whole crowd who has ever treated her decently, but of course she's nobody. Everyone sits on her. As if," he spoke with heat, "Stella weren't as good as the best of 'em—and better! What right have they to treat her like a social outcast just because she came out here to me on her own? It's hateful! It's iniquitous! What else could she have done?"

"It seems reasonable—from a man's point of view," said Monck.

"It was reasonable. It was the only thing possible. And just for that they chose to turn the cold shoulder on her,—to ostracize her practically. What had she done to them? What right had they to treat her like that?" Fierce resentment sounded in Tommy's voice.

"I'll tell you if you want to know," said Monck abruptly. "It's the law of the pack to rend an outsider. And your sister will always be that—married or otherwise. They may fawn upon her later, Dacre being one to hold his own with women. But they will always hate her in their hearts. You see, she is beautiful."

"Is she?" said Tommy in surprise. "Do you know, I never thought of that!"

Monck laughed—a cold, sardonic laugh. "Quite so! You wouldn't! But Dacre has—and a few more of us."

"Oh, confound Dacre!" Tommy's irritation returned with a rush. "I detest the man! He behaves as if he were conferring a favour. When he was making that speech to-night, I wanted to fling my glass at him."

"Ah, but you mustn't do those things." Monck spoke reprovingly. "You may be young, but you're past the schoolboy stage. Dacre is more of a woman's favourite than a man's, you must remember. If your sister is not in love with him, she is about the only woman in the station who isn't."

"That's the disgusting part of it," fumed Tommy. "He makes love to every woman he meets."

They had reached a shadowy compound that bordered the dusty road for a few yards. A little eddying wind made a mysterious whisper among its thirsty shrubs. The bungalow it surrounded showed dimly in the starlight, a wooden structure with a raised verandah and a flight of steps leading up to it. A light thrown by a red-shaded lamp shone out from one of the rooms, casting a shaft of ruddy brilliance into the night as though it defied the splendour without. It shone upon Tommy's face as he paused, showing it troubled and anxious.

"You may as well come in," he said. "She is sure to be ready. Come in and have a drink!"

Monck stood still. His dark face was in shadow. He seemed to be debating some point with himself.

Finally, "All right. Just for a minute," he said. "But, look here, Tommy! Don't you let your sister suspect that you've been making a confidant of me! I don't fancy it would please her. Put on a grin, man! Don't look bowed down with family cares! She is probably quite capable of looking after herself—like the rest of 'em."

He clapped a careless hand on the lad's shoulder as they turned up the path together towards the streaming red light.

"You're a bit of a woman-hater, aren't you?" said Tommy.

And Monck laughed again his short, rather bitter laugh; but he said no word in answer.

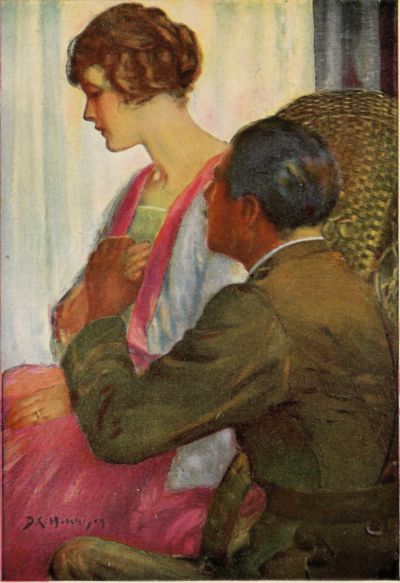

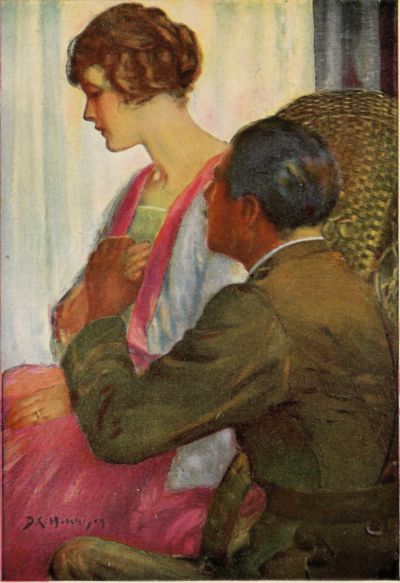

In the room with the crimson-shaded lamp Stella Denvers sat waiting. The red glow compassed her warmly, striking wonderful copper gleams in the burnished coils of her hair. Her face was bent over the long white gloves that she was pulling over her wrists, a pale face that yet was extraordinarily vivid, with features that were delicate and proud, and lips that had the exquisite softness and purity of a flower.

She raised her eyes from her task at sound of the steps below the window, and their starry brightness under her straight black brows gave her an infinite allurement. Certainly a beautiful woman, as Monck had said, and possessing the brilliance and the wonder of youth to an almost dazzling degree! Perhaps it was not altogether surprising that the ladies of the regiment had not been too enthusiastic in their welcome of this sister of Tommy's who had come so suddenly into their midst, defying convention. Her advent had been utterly unexpected—a total surprise even to Tommy, who, returning one day from the polo-ground, had found her awaiting him in the bachelor quarters which he had shared with three other subalterns. And her arrival had set the whole station buzzing.

Led by the Colonel's wife, Lady Harriet Mansfield, the women of the regiment had—with the single exception of Mrs. Ralston whose opinion was of no account—risen and condemned the splendid stranger who had come amongst them with such supreme audacity and eclipsed the fairest of them. Stella's own simple explanation that she had, upon attaining her majority and fifty pounds a year, decided to quit the home of some distant relatives who did not want her and join Tommy who was the only near relation she had, had satisfied no one. She was an interloper, and as such they united to treat her. As Lady Harriet said, no nice girl would have dreamed of taking such an extraordinary step, and she had not the smallest intention of offering her the chaperonage that she so conspicuously lacked. If Mrs. Ralston chose to do so, that was her own affair. Such action on the part of the surgeon's very ordinary wife would make no difference to any one. She was glad to think that all the other ladies were too well-bred to accept without reservation so unconventional a type.

The fact that she was Tommy's sister was the only consideration in her favour. Tommy was quite a nice boy, and they could not for his sake entirely exclude her from the regimental society, but to no intimate gathering was she ever invited, nor from the female portion of the community was there any welcome for her at the Club.

The attitude of the officers of the regiment was of a totally different nature. They had accepted her with enthusiasm, possibly all the more marked on account of the aloofness of their women folk, and in a very short time they were paying her homage as one man. The subalterns who had shared their quarters with Tommy turned out to make room for her, treating her like a queen suddenly come into her own, and like a queen she entered into possession, accepting all courtesy just as she ignored all slights with a delicate self-possession that yet knew how to be gracious when occasion demanded.

Mrs. Ralston would have offered her harbourage had she desired it, but there was pride in Stella—a pride that surged and rebelled very far below her serenity. She received favours from none.

And so, unshackled and unchaperoned, she had gone her way among her critics, and no one—not even Tommy—suspected how deep was the wound that their barely-veiled hostility had inflicted. In bitterness of soul she hid it from all the world, and only her brother and her brother's grim and somewhat unapproachable captain were even vaguely aware of its existence.

Everard Monck was one of the very few men who had not laid themselves down before her dainty feet, and she had gradually come to believe that this man shared the silent, side-long disapproval manifested by the women. Very strangely that belief hurt her even more deeply, in a subtle, incomprehensible fashion, than any slights inflicted by her own sex. Possibly Tommy's warm enthusiasm for the man had made her more sensitive regarding his good opinion. And possibly she was over ready to read condemnation in his grave eyes. But—whatever the reason—she would have given much to have had him on her side. Somehow it mattered to her, and mattered vitally.

But Monck had never joined her retinue of courtiers. He was never other than courteous to her, but he did not seek her out. Perhaps he had better things to do. Aloof, impenetrable, cold, he passed her by, and she would have been even more amazed than Tommy had she heard him describe her as beautiful, so convinced was she that he saw in her no charm.

It had been a disheartening struggle, this hewing for herself a way along the rocky paths of prejudice, and many had been the thorns under her feet. Though she kept a brave heart and never faltered, she had tired inevitably of the perpetual effort it entailed. Three weeks after her arrival, when the annual exodus of the ladies of the regiment to the Hills was drawing near, she became engaged to Ralph Dacre, the handsomest and most irresponsible man in the mess.

With him at least her power to attract was paramount. He was blindly, almost fulsomely, in love. Her beauty went to his head from the outset; it fired his blood. He worshipped her hotly, and pursued her untiringly, caring little whether she returned his devotion so long as he ultimately took possession. And when finally, half-disdainfully, she yielded to his insistence, his one all-mastering thought became to clinch the bargain before she could repent of it. It was a mad and headlong passion that drove him—not for the first time in his life; and the subtle pride of her and the soft reserve made her all the more desirable in his eyes.

He had won her; he did not stop to ask himself how. The women said that the luck was all on her side. The men forebore to express an opinion. Dacre had attained his captaincy, but he was not regarded with great respect by any one. His fellow-officers shrugged their shoulders over him, and the commanding officer, Colonel Mansfield, had been heard to call him "the craziest madman it had ever been his fate to meet." No one, except Tommy, actively disliked him, and he had no grounds for so doing, as Monck had pointed out. Monck, who till then had occupied the same bungalow, declared he had nothing against him, and he was surely in a position to form a very shrewd opinion. For Monck was neither fool nor madman, and there was very little that escaped his silent observation.

He was acting as best man at the morrow's ceremony, the function having been almost thrust upon him by Dacre who, oddly enough, shared something of Tommy's veneration for his very reticent brother-officer. There was scant friendship between them. Each had been accustomed to go his own way wholly independent of the other. They were no more than casual acquaintances, and they were content to remain such. But undoubtedly Dacre entertained a certain respect for Monck and observed a wariness of behaviour in his presence that he never troubled to assume for any other man. He was careful in his dealings with him, being at all times not wholly certain of his ground.

Other men felt the same uncertainty in connection with Monck. None—save Tommy—was sure what manner of man he was. Tommy alone took him for granted with whole-hearted admiration, and at his earnest wish it had been arranged between them that Monck should take up his abode with him when the forthcoming marriage had deprived each of a companion. Tommy was delighted with the idea, and he had a gratifying suspicion that Monck himself was inclined to be pleased with it also.

The Green Bungalow had become considerably more homelike since Stella's arrival, and Tommy meant to keep it so. He was sure that Monck and he would have the same tastes.

And so on that eve of his sister's wedding, the thought of their coming companionship was the sole redeeming feature of the whole affair, and he turned in his impulsive fashion to say so just as they reached the verandah steps.

But the words did not leave his lips, for the red glow flung from the lamp had found Monck's upturned face, and something—something about it—checked all speech for the moment. He was looking straight up at the lighted window and the face of a beautiful woman who gazed forth into the night. And his eyes were no longer cold and unresponsive, but burning, ardent, intensely alive. Tommy forgot what he was going to say and only stared.

The moment passed; it was scarcely so much as a moment. And Monck moved on in his calm, unfaltering way.

"Your sister is ready and waiting," he said.

They ascended the steps together, and the girl who sat by the open window rose with a stately movement and stepped forward to meet them.

"Hullo, Stella!" was Tommy's greeting. "Hope I'm not awfully late. They wasted such a confounded time over toasts at mess to-night. Yours was one of 'em, and I had to reply. I hadn't a notion what to say. Captain Monck thinks I made an awful hash of it though he is too considerate to say so."

"On the contrary I said 'Hear, hear!' to every stutter," said Monck, bowing slightly as he took the hand she offered.

She was wearing a black lace dress with a glittering spangled scarf of Indian gauze floating about her. Her neck and shoulders gleamed in the soft red glow. She was superb that night.

She smiled at Monck, and her smile was as a shining cloak hiding her soul. "So you have started upon your official duties already!" she said. "It is the best man's business to encourage and console everyone concerned, isn't it?"

The faint cynicism of her speech was like her smile. It held back all intrusive curiosity. And the man's answering smile had something of the same quality. Reserve met reserve.

"I hope I shall not find it very arduous in that respect," he said. "I did not come here in that capacity."

"I am glad of that," she said. "Won't you come in and sit down?"

She motioned him within with a queenly gesture, but her invitation was wholly lacking in warmth. It was Tommy who pressed forward with eager hospitality.

"Yes, and have a drink! It's a thirsty right. It's getting infernally hot. Stella, you're lucky to be going out of it."

"Oh, I am very lucky," Stella said.

They entered the lighted room, and Tommy went in search of refreshment.

"Won't you sit down?" said Stella.

Her voice was deep and pure, and the music in it made him wonder if she sang. He sat facing her while she returned with apparent absorption to the fastening of her gloves. She spoke again after a moment without raising her eyes. "Are you proposing to take up your abode here to-morrow?"

"That's the idea," said Monck.

"I hope you and Tommy will be quite comfortable," she said. "No doubt he will be a good deal happier with you than he has been for the past few weeks with me."

"I don't know why he should be," said Monck.

"No?" She was frowning slightly over her glove. "You see, my sojourn here has not been—a great success. I think poor Tommy has felt it rather badly. He likes a genial atmosphere."

"He won't get much of that in my company," observed Monck.

She smiled momentarily. "Perhaps not. But I think he will not be sorry to be relieved of family cares. They have weighed rather heavily upon him."

"He will be sorry to lose you," said Monck.

"Oh, of course, in a way. But he will soon get over that." She looked up at him suddenly. "You will all be rather thankful when I am safely married, Captain Monck," she said.

There was a second or two of silence. Monck's eyes looked straight back into hers while it lasted, but they held no warmth, scarcely even interest.

"I really don't know why you should say that, Miss Denvers," he said stiffly at length.

Stella's gloved hands clasped each other. She was breathing somewhat hard, yet her bearing was wholly regal, even disdainful.

"Only because I realize that I have been a great anxiety to all the respectable portion of the community," she made careless reply. "I think I am right in classing you under that heading, am I not?"

He heard the challenge in her tone, delicately though she presented it, and something in him that was fierce and unrestrained sprang up to meet it. But he forced it back. His expression remained wholly inscrutable.

"I don't think I can claim to be anything else," he said. "But that fact scarcely makes me in any sense one of a community. I think I prefer to stand alone."

Her blue eyes sparkled a little. "Strangely, I have the same preference," she said. "It has never appealed to me to be one of a crowd. I like independence—whatever the crowd may say. But I am quite aware that in a woman that is considered a dangerous taste. A woman should always conform to rule."

"I have never studied the subject," said Monck.

He spoke briefly. Tommy's confidences had stirred within him that which could not be expressed. The whole soul of him shrank with an almost angry repugnance from discussing the matter with her. No discussion could make any difference at this stage.

Again for a second he saw her slight frown. Then she leaned back in her chair, stretching up her arms as if weary of the matter. "In fact you avoid all things feminine," she said. "How discreet of you!"

A large white moth floated suddenly in and began to beat itself against the lamp-shade. Monck's eyes watched it with a grim concentration. Stella's were half-closed. She seemed to have dismissed him from her mind as an unimportant detail. The silence widened between them.

Suddenly there was a movement. The fluttering creature had found the flame and fallen dazed upon the table. Almost in the same second Monck stooped forward swiftly and silently, and crushed the thing with his closed fist.

Stella drew a quick breath. Her eyes were wide open again. She sat up.

"Why did you do that?"

He looked at her again, a smouldering gleam in his eyes. "It was on its way to destruction," he said.

"And so you helped it!"

He nodded. "Yes. Long-drawn-out agonies don't attract me."

Stella laughed softly, yet with a touch of mockery. "Oh, it was an act of mercy, was it? You didn't look particularly merciful. In fact, that is about the last quality I should have attributed to you."

"I don't think," Monck said very quietly, "that you are in a position to judge me." She leaned forward. He saw that her bosom was heaving. "That is your prerogative, isn't it?" she said. "I—I am just the prisoner at the bar, and—like the moth—I have been condemned—without mercy."

He raised his brows sharply. For a second he had the look of a man who has been stabbed in the back. Then with a swift effort he pulled himself together.

In the same moment Stella rose. She was smiling, and there was a red flush in her cheeks. She took her fan from the table.

"And now," she said, "I am going to dance—all night long. Every officer in the mess—save one—has asked me for a dance."

He was on his feet in an instant. He had checked one impulse, but even to his endurance there were limits. He spoke as one goaded.

"Will you give me one?"

She looked him squarely in the eyes. "No, Captain Monck."

His dark face looked suddenly stubborn. "I don't often dance," he said. "I wasn't going to dance to-night. But—I will have one—I must have one—with you."

"Why?" Her question fell with a crystal clearness. There was something of crystal hardness in her eyes.

But the man was undaunted. "Because you have wronged me, and you owe me reparation."

"I—have wronged—you!" She spoke the words slowly, still looking him in the eyes.

He made an abrupt gesture as of holding back some inner force that strongly urged him. "I am not one of your persecutors," he said. "I have never in my life presumed to judge you—far less condemn you."

His voice vibrated as though some emotion fought fiercely for the mastery. They stood facing each other in what might have been open antagonism but for that deep quiver in the man's voice.

Stella spoke after the lapse of seconds. She had begun to tremble.

"Then why—why did you let me think so? Why did you always stand aloof?"

There was a tremor in her voice also, but her eyes were shining with the light half-eager, half-anxious, of one who seeks for buried treasure.

Monck's answer was pitched very low. It was as if the soul of him gave utterance to the words. "It is my nature to stand aloof. I was waiting."

"Waiting?" Her two hands gripped suddenly hard upon her fan, but still her shining eyes did not flinch from his. Still with a quivering heart she searched.

Almost in a whisper came his reply. "I was waiting—till my turn should come."

"Ah!" The fan snapped between her hands; she cast it from her with a movement that was almost violent.

Monck drew back sharply. With a smile that was grimly cynical he veiled his soul. "I was a fool, of course, and I am quite aware that my foolishness is nothing to you. But at least you know now how little cause you have to hate me."

She had turned from him and gone to the open window. She stood there bending slightly forward, as one who strains for a last glimpse of something that has passed from sight.

Monck remained motionless, watching her. From another room near by there came the sound of Tommy's humming and the cheery pop of a withdrawn cork.

Stella spoke at last, in a whisper, and as she spoke the strain went out of her attitude and she drooped against the wood-work of the window as if spent. "Yes; but I know—too late."

The words reached him though he scarcely felt that they were intended to do so. He suffered them to go into silence; the time for speech was past.

The seconds throbbed away between them. Stella did not move or speak again, and at last Monck turned from her. He picked up the broken fan, and with a curious reverence he laid it out of sight among some books on the table.

Then he stood immovable as granite and waited.

There came the sound of Tommy's footsteps, and in a moment the door was flung open. Tommy advanced with all a host's solicitude.

"Oh, I say, I'm awfully sorry to have kept you waiting so long. That silly ass of a khit had cleared off and left us nothing to drink. Stella, we shall miss all the fun if we don't hurry up. Come on, Monck, old chap, say when!"

He stopped at the table, and Stella turned from the window and moved forward. Her face was pale, but she was smiling.

"Captain Monck is coming with us, Tommy," she said.

"What?" Tommy looked up sharply. "Really? I say, Monck, I'm pleased. It'll do you good."

Monck was smiling also, faintly, grimly. "Don't mix any strong waters for me, Tommy!" he said. "And you had better not be too generous to yourself! Remember, you will have to dance with Lady Harriet!"

Tommy grimaced above the glasses. "All right. Have some lime-juice! You will have to dance with her too. That's some consolation!"

"I?" said Monck. He took the glass and handed it to Stella, then as she shook her head he put it to his own lips and drank as a man drinks to a memory. "No," he said then. "I am dancing only one dance to-night, and that will not be with Lady Harriet Mansfield."

"Who then?" questioned Tommy.

It was Stella who answered him, in her voice a note that sounded half-reckless, half-defiant. "It isn't given to every woman to dance at her own funeral," she said: "Captain Monck has kindly consented to assist at the orgy of mine."

"Stella!" protested Tommy, flushing. "I hate to hear you talking like that!"

Stella laughed a little, softly, as though at the vagaries of a child. "Poor Tommy!" she said. "What it is to be so young!"

"I'd sooner be a babe in arms than a cynic," said Tommy bluntly.

Lady Harriet's lorgnettes were brought piercingly to bear upon the bride-elect that night, and her thin, refined features never relaxed during the operation. She was looking upon such youth and loveliness as seldom came her way; but the sight gave her no pleasure. She deemed it extremely unsuitable that Stella should dance at all on the eve of her wedding, and when she realized that nearly every man in the room was having his turn, her disapproval by no means diminished. She wondered audibly to one after another of her followers what Captain Dacre was about to permit such a thing. And when Monck—Everard Monck of all people who usually avoided all gatherings at the Club and had never been known to dance if he could find any legitimate means of excusing himself—waltzed Stella through the throng, her indignation amounted almost to anger. The mess had yielded to the last man.

"I call it almost brazen," she said to Mrs. Burton, the Major's wife. "She flaunts her unconventionality in our faces."

"A grave mistake," agreed Mrs. Burton. "It will not make us think any the more highly of her when she is married."

"I am in two minds about calling on her," declared Lady Harriet. "I am very doubtful as to the advisability of inviting any one so obviously unsuitable into our inner circle. Of course Mrs. Ralston," she raised her long pointed chin upon the name, "will please herself in the matter. She will probably be the first to try and draw her in, but what Mrs. Ralston does and what I do are two very different things. She is not particular as to the society she keeps, and the result is that her opinion is very justly regarded as worthless."

"Oh, quite," agreed Mrs. Burton, sending an obviously false smile in the direction of the lady last named who was approaching them in the company of Mrs. Ermsted, the Adjutant's wife, a little smart woman whom Tommy had long since surnamed "The Lizard."

Mrs. Ralston, the surgeon's wife, had once been a pretty girl, and there were occasions still on which her prettiness lingered like the gleams of a fading sunset. She had a diffident manner in society, but yet she was the only woman in the station who refused to follow Lady Harriet's lead. As Tommy had said, she was a nobody. Her influence was of no account, but yet with unobtrusive insistence she took her own way, and none could turn her therefrom.

Mrs. Ermsted held her up to ridicule openly, and yet very strangely she did not seem to dislike the Adjutant's sharp-tongued little wife. She had been very good to her on more than one occasion, and the most appreciative remark that Mrs. Ermsted had ever found to make regarding her was that the poor thing was so fond of drudging for somebody that it was a real kindness to let her. Mrs. Ermsted was quite willing to be kind to any one in that respect.

They approached now, and Lady Harriet gave to each her distinctive smile of royal condescension.

"I expected to see you dancing, Mrs. Ermsted," she said.

"Oh, it's too hot," declared Mrs. Ermsted. "You want the temperament of a salamander to dance on a night like this."

She cast a barbed glance towards Stella as she spoke as Monck guided her to the least crowded corner of the ball-room. Stella's delicate face was flushed, but it was the exquisite flush of a blush-rose. Her eyes were of a starry brightness; she had the radiant look of one who has achieved her heart's desire.

"What a vision of triumph!" commented Mrs. Ermsted. "It's soothing anyway to know that that wild-rose complexion won't survive the summer. Captain Monck looks curiously out of his element. No doubt he prefers the bazaars."

"But Stella Denvers is enchanting to-night," murmured Mrs. Ralston.

Lady Harriet overheard the murmur, and her aquiline nose was instantly elevated a little higher. "So many people never see beyond the outer husk," she said.

Mrs. Burton smiled out of her slitty eyes. "I should scarcely imagine Captain Monck to be one of them," she said. "He is obviously here as a matter of form to-night. The best man must be civil to the bride—whatever his feelings."

Lady Harriet's face cleared a little, although her estimate of Mrs. Burton's opinion was not a very high one. "That may account for Captain Dacre's extremely complacent attitude," she said. "He regards the attentions paid to his fiancée as a tribute to himself."

"He may change his point of view when he is married," laughed Mrs. Ermsted. "It will be interesting to watch developments. We all know what Captain Dacre is. I have never yet seen him satisfied to take a back seat."

Mrs. Burton laughed with her. "Nor content to occupy even a front one at the same show for long," she observed. "I marvel to see him caught in the noose so easily."

"None but an adventuress could have done it," declared Mrs. Ermsted. "She has practised the art of slinging the lasso before now."

"My dear," said Mrs. Ralston, "forgive me, but that is unworthy of you."

Mrs. Ermsted flicked an eyelid in Mrs. Burton's direction with an insouciance that somehow robbed the act of any serious sting. "Poor Mrs. Ralston holds such a high opinion of everybody," she said, "that she must meet with a hundred disappointments in a day."

Lady Harriet's down-turned lips said nothing, but they were none the less eloquent on that account.

Mrs. Ralston's eyes of faded blue watched Stella with a distressed look. She was not hurt on her own account, but she hated to hear the girl criticized in so unfriendly a spirit. Stella was more brilliantly beautiful that night than she had ever before seen her, and she longed to hear a word of appreciation from that hostile group of women. But she knew very well that the longing was vain, and it was with relief that she saw Captain Dacre himself saunter up to claim Mrs. Ermsted for a partner.

Smiling, debonair, complacent, the morrow's bridegroom had a careless quip for all and sundry on that last night. It was evident that his fiancée's defection was a matter of no moment to him. Stella was to have her fling, and he, it seemed, meant to have his. He and Mrs. Ermsted had had many a flirtation in the days that were past and it was well known that Captain Ermsted heartily detested him in consequence. Some even hinted that matters had at one time approached very near to a climax, but Ralph Dacre knew how to handle difficult situations, and with considerable tact had managed to avoid it. Little Mrs. Ermsted, though still willing to flirt, treated him with just a tinge of disdain, now-a-days; no one knew wherefore. Perhaps it was more for Stella's edification than her own that she condescended to dance with him on that sweltering evening of Indian spring.

But Stella was evidently too engrossed with her own affairs to pay much attention to the doings of her fiancé. His love-making was not of a nature to be carried on in public. That would come later when they walked home through the glittering night and parted in the shadowy verandah while Tommy tramped restlessly about within the bungalow. He would claim that as a right she knew, and once or twice remembering the methods of his courtship a little shudder went through her as she danced. Very willingly would she have left early and foregone all intercourse with her lover that night. But there was no escape for her. She was pledged to the last dance, and for the sake of the pride that she carried so high she would not shrink under the malicious eyes that watched her so unsparingly. Her dance with Monck was quickly over, and he left her with the briefest word of thanks. Afterwards she saw him no more.

The rest of the evening passed in a whirl of gaiety that meant very little to her. Perhaps, on the whole, it was easier to bear than an evening spent in solitude would have been. She knew that she would be too utterly weary to lie awake when bedtime came at last. And the night would be so short—ah, so short! And so she danced and laughed with the gayest of the merrymakers, and when it was over at last even the severest of her critics had to admit that her triumph was complete. She had borne herself like a queen at a banquet of rejoicing, and like a queen she finally quitted the festive scene in a 'rickshaw drawn by a team of giddy subalterns, scattering her careless favours upon all who cared to compete for them.

As she had foreseen, Dacre accompanied the procession. He had no mind to be cheated of his rights, and it was he who finally dispersed the irresponsible throng at the steps of the verandah, handing her up them with a royal air and drawing her away from the laughter and cheering that followed her.

With her hand pressed lightly against his side, he led her away to the darkest corner, and there he pushed back the soft wrap from her shoulders and gathered her into his arms.

She stood almost stiffly in his embrace, neither yielding nor attempting to avoid. But at the touch of his lips upon her neck she shivered. There was something sensual in that touch that revolted her—in spite of herself.

"Ralph," she said, and her voice quivered a little, "I think you must say good-bye to me. I am tired to-night. If I don't rest, I shall never be ready for to-morrow."

He made an inarticulate sound that in some fashion expressed what the drawing of his lips had made her feel. "Sweetheart—to-morrow!" he said, and kissed her again with a lingering persistence that to her overwrought nerves had in it something that was almost unendurable. It made her think of an epicurean tasting some favourite dish and smacking his lips over it.

A hint of irritation sounded in her voice as she said, drawing slightly away from him, "Yes, I want to rest for the few hours that are left. Please say good night now, Ralph! Really I am tired."

He laughed softly, his cheek laid to hers. "Ah, Stella!" he said. "What a queen you have been to-night! I have been watching you with the rest of the world, and I shouldn't mind laying pretty heavy odds that there isn't a single man among 'em that doesn't envy me."

Stella drew a deep breath as if she laboured against some oppression. "It's nice to be envied, isn't it?" she said.

He kissed her again. "Ah! You're a prize!" he said. "It was just a question of first in, and I never was one to let the grass grow. I plucked the fruit while all the rest were just looking at it. Stella—mine! Stella—mine!"

His lips pressed hers between the words closely, possessively, and again involuntarily she shivered. She could not return his caresses that night.

His hold relaxed at last. "How cold you are, my Star of the North!" he said. "What is it? Surely you are not nervous at the thought of to-morrow after your triumph to-night! You will carry all before you, never fear!"

She answered him in a voice so flat and emotionless that it sounded foreign even to herself. "Oh, no, I am not nervous. I'm too tired to feel anything to-night."

He took her face between his hands. "Ah, well, you will be all mine this time to-morrow. One kiss and I will let you go. You witch—you enchantress! I never thought you would draw old Monck too into your toils."

Again she drew that deep breath as of one borne down by some heavy weight. "Nor I," she said, and gave him wearily the kiss for which he bargained.

He did not stay much longer, possibly realizing his inability to awake any genuine response in her that night. Her remoteness must have chilled any man less ardent. But he went from her too encompassed with blissful anticipation to attach any importance to the obvious lack of corresponding delight on her part. She was already in his estimation his own property, and the thought of her happiness was one which scarcely entered into his consideration. She had accepted him, and no doubt she realized that she was doing very well for herself. He had no misgivings on that point. Stella was a young woman who knew her own mind very thoroughly. She had secured the finest catch within reach, and she was not likely to repent of her bargain at this stage.

So, unconcernedly, he went his way, throwing a couple of annas with careless generosity to a beggar who followed him along the road whining for alms, well-satisfied with himself and with all the world on that wonderful night that had witnessed the final triumph of the woman whom he had chosen for his bride, asking nought of the gods save that which they had deigned to bestow—Fortune's favourite whom every man must envy.

It was remarked by Tommy's brother-officers on the following day that it was he rather than the bride who displayed all the shyness that befitted the occasion.

As he walked up the aisle with his sister's hand on his arm, his face was crimson and reluctant, and he stared straight before him as if unwilling to meet all the watching eyes that followed their progress. But the bride walked proudly and firmly, her head held high with even the suspicion of an upward, disdainful curve to her beautiful mouth, the ghost of a defiant smile. To all who saw her she was a splendid spectacle of bridal content.

"Unparalleled effrontery!" whispered Lady Harriet, surveying the proud young face through her lorgnettes.

"Ah, but she is exquisite," murmured Mrs. Ralston with a wistful mist in her faded eyes.

"'Faultily faultless, icily regular, splendidly null,'" scoffed little Mrs. Ermsted upon whose cheeks there bloomed a faint fixed glow.

Yes, she was splendid. Even the most hostile had to admit it. On that, the day of her final victory, she surpassed herself. She shone as a queen with majestic self-assurance, wholly at her ease, sublimely indifferent to all criticism.

At the chancel-steps she bestowed a brief smile of greeting upon her waiting bridegroom, and for a single moment her steady eyes rested, though without any gleam of recognition, upon the dark face of the best man.

Then the service began, and with the utmost calmness of demeanour she took her part.

When the service was over, Tommy extended his hesitating invitation to Lady Harriet and his commanding officer to follow the newly wedded pair to the vestry. They went. Colonel Mansfield with a species of jocose pomposity specially assumed for the occasion, his wife, upright, thin-lipped, forbidding, instinct with wordless disapproval.

The bride,—the veil thrown back from her beautiful face,—stood laughing with her husband. There was no fixity in the soft flush of those delicately rounded cheeks. Even Lady Harriet realized that, though she had never seen so much colour in the girl's face before. She advanced stiffly, and Ralph Dacre with smiling grace took his wife's arm and drew her forward.

"This is good of you, Lady Harriet," he declared. "I was hoping for your support. Allow me to introduce—my wife!"

His words had a pride of possession that rang clarion-like in every syllable, and in response Lady Harriet was moved to offer a cold cheek in salutation to the bride. Stella bent instantly and kissed it with a quick graciousness that would have melted any one less austere, but in Lady Harriet's opinion the act was marred by its very impulsiveness. She did not like impulsive people. So, with chill repression, she accepted the only overture from Stella that she was ever to receive.

But if she were proof against the girl's ready charm, with her husband it was quite otherwise. Stella broke through his pomposity without effort, giving him both her hands with a simplicity that went straight to his heart. He held them in a tight, paternal grasp.

"God bless you, my dear!" he said. "I wish you both every happiness from the bottom of my soul."

She turned from him a few seconds later with a faintly tremulous laugh to give her hand to the best man, but it did not linger in his, and to his curtly proffered felicitations she made no verbal response whatever.

Ten minutes later, as she left the vestry with her husband, Mrs. Ralston pressed forward unexpectedly, and openly checked her progress in full view of the whole assembly.

"My dear," she murmured humbly, "my dear, you'll allow me I know. I wanted just to tell you how beautiful you look, and how earnestly I pray for your happiness."

It was a daring move, and it had not been accomplished without courage. Lady Harriet in the background stiffened with displeasure, nearer to actual anger than she had ever before permitted herself to be with any one so contemptible as the surgeon's wife. Even Major Ralston himself, most phlegmatic of men, looked momentarily disconcerted by his wife's action.

But Stella—Stella stopped dead with a new light in her eyes, and in a moment dropped her husband's arm to fling both her own about the gentle, faded woman who had dared thus openly to range herself on her side.

"Dear Mrs. Ralston," she said, not very steadily, "how more than kind of you to tell me that!"

The tears were actually in her eyes as she kissed the surgeon's wife. That spontaneous act of sympathy had pierced straight through her armour of reserve and found its way to her heart. Her face, as she passed on down the aisle by her husband's side, was wonderfully softened, and even Mrs. Ermsted found no gibe to fling after her. The smile that quivered on Stella's lips was full of an unconscious pathos that disarmed all criticism.

The sunshine outside the church was blinding. It smote through the awning with pitiless intensity. Around the carriage a curious crowd had gathered to see the bridal procession. To Stella's dazzled eyes it seemed a surging sea of unfamiliar faces. But one face stood out from the rest—the calm countenance of Ralph Dacre's magnificent Sikh servant clad in snowy linen, who stood at the carriage door and gravely bowed himself before her, stretching an arm to protect her dress from the wheel.

"This is Peter the Great," said Dacre's careless voice, "a highly honourable person, Stella, and a most efficient bodyguard."

"How do you do?" said Stella, and held out her hand.

She acted with the utmost simplicity. During her four weeks' sojourn in India she had not learned to treat the native servant with contempt, and the majestic presence of this man made her feel almost as if she were dealing with a prince.

He straightened himself swiftly at her action, and she saw a sudden, gleaming smile flash across his grave face. Then he took the proffered hand, bending low over it till his turbaned forehead for a moment touched her fingers.

"May the sun always shine on you, my mem-sahib!" he said.

Stella realized afterwards that in action and in words there lay a tacit acceptance of her as mistress which was to become the allegiance of a lifelong service.

She stepped into the carriage with a feeling of warmth at her heart which was very different from the icy constriction that had bound it when she had arrived at the church a brief half-hour before with Tommy.

Her husband's arm was about her as they drove away. He pressed her to his side. "Oh, Star of my heart, how superb you are!" he said. "I feel as if I had married a queen. And you weren't even nervous."

She bent her head, not looking at him. "Poor Tommy was," she said.

He smiled tolerantly. "Tommy's such a youngster."

She smiled also. "Exactly one year younger than I am."

He drew her nearer, his eyes devouring her. "You, Stella!" he said. "You are as ageless as the stars."

She laughed faintly, not yielding herself to the closer pressure though not actually resisting it. "That is merely a form of telling me that I am much older than I seem," she said. "And you are quite right. I am."

His arm compelled her. "You are you," he said. "And you are so divinely young and beautiful that there is no measuring you by ordinary standards. They all know it. That is why you weren't received into the community with open arms. You are utterly above and beyond them all."

She flinched slightly at the allusion. "I hope I am not so extraordinary as all that," she said.

His arm became insistent. "You are unique," he said. "You are superb."

There was passion barely suppressed in his hold and a sudden swift shiver went through her. "Oh, Ralph," she said, "don't—- don't worship me too much!"

Her voice quivered in its appeal, but somehow its pathos passed him by. He saw only her beauty, and it thrilled every pulse in his body. Fiercely almost, he strained her to him. And he did not so much as notice that her lips trembled too piteously to return his kiss, or that her submission to his embrace was eloquent of mute endurance rather than glad surrender. He stood as a conqueror on the threshold of a newly acquired kingdom and exulted over the splendour of its treasures because it was all his own.

It did not even occur to him to doubt that her happiness fully equalled his. Stella was a woman and reserved; but she was happy enough, oh, she was happy enough. With complacence he reflected that if every man in the mess envied him, probably every woman in the station would have gladly changed places with her. Was he not Fortune's favourite? What happier fate could any woman desire than to be his bride?

It was a fortnight after the wedding, on an evening of intense heat, that Everard Monck, now established with Tommy at The Green Bungalow, came in from polo to find the mail awaiting him. He sauntered in through the verandah in search of a drink which he expected to find in the room which Stella during her brief sojourn had made more dainty and artistic than the rest, albeit it had never been dignified by the name of drawing-room. There was light green matting on the floor and there were also light green cushions in each of the long wicker chairs. Curtains of green gauze hung before the windows, and the fierce sunlight filtering through gave the room a strangely translucent effect. It was like a chamber under the sea.

It had been Monck's intention to have his drink and pass straight on to his own quarters for a bath, but the letters on the table caught his eye and he stopped. Standing in the green dimness with a tumbler in one hand, he sorted them out. There were two for himself and two for Tommy, the latter obviously bills, and under these one more, also for Tommy in a woman's clear round writing. It came from Srinagar, and Monck stood for a second or two holding it in his hand and staring straight out before him with eyes that saw not. Just for those seconds a mocking vision danced gnomelike through his brain. Just at this moment probably most of the other men were opening letters from their wives in the Hills. And he saw the chance he had not taken like a flash of far, elusive sunlight on the sky-line of a troubled sea.

The vision passed. He laid down the letter and took up his own correspondence. One of the letters was from England. He poured out his drink and flung himself down to read it.

It came from the only relation he possessed in the world—his brother. Bernard Monck was the elder by fifteen years—a man of brilliant capabilities, who had long since relinquished all idea of worldly advancement in the all-absorbing interest of a prison chaplaincy. They had not met for over five years, but they maintained a regular correspondence, and every month brought to Everard Monck the thin envelope directed in the square, purposeful handwriting of the man who had been during the whole of his life his nearest and best friend. Lying back in the wicker-chair, relaxed and weary, he opened the letter and began to read.

Ten minutes later, Tommy Denvers, racing in, also in polo-kit, stopped short upon the threshold and stared in shocked amazement as if some sudden horror had caught him by the throat.

"Great heavens above, Monck! What's the matter?" he ejaculated.

Perhaps it was in part due to the green twilight of the room, but it seemed to him in that first startled moment that Monck's face had the look of a man who had received a deadly wound. The impression passed almost immediately, but the memory of it was registered in his brain for all time.

Monck raised the tumbler to his lips and drank before replying, and as he did so his customary grave composure became apparent, making Tommy wonder if his senses had tricked him. He looked at the lad with sombre eyes as he set down the glass. His brother's letter was still gripped in his hand.

"Hullo, Tommy!" he said, a shadowy smile about his mouth. "What are you in such a deuce of a hurry about?"

Tommy glanced down at the letters on the table and pounced upon the one that lay uppermost. "A letter from Stella! And about time, too! She isn't much of a correspondent now-a-days. Where are they now? Oh, Srinagar. Lucky beggar—Dacre! Wish he'd taken me along as well as Stella! What am I in such a hurry about? Well, my dear chap, look at the time! You'll be late for mess yourself if you don't buck up."

Tommy's treatment of his captain was ever of the airiest when they were alone. He had never stood in awe of Monck since the days of his illness; but even in his most familiar moments his manner was not without a certain deference. His respect for him was unbounded, and his pride in their intimacy was boyishly whole-hearted. There was no sacrifice great or small that he would not willingly have offered at Monck's behest.

And Monck knew it, realized the lad's devotion as pure gold, and valued it accordingly. But, that fact notwithstanding, his faith in Tommy's discretion did not move him to bestow his unreserved confidence upon him. Probably to no man in the world could he have opened his secret soul. He was not of an expansive nature. But Tommy occupied an inner place in his regard, and there were some things that he veiled from all beside which he no longer attempted to hide from this faithful follower of his. Thus far was Tommy privileged.

He got to his feet in response to the boy's last remark. "Yes, you're right. We ought to be going. I shall be interested to hear what your sister thinks of Kashmir. I went up there on a shooting expedition two years after I came out. It's a fine country."

"Is there anywhere that you haven't been?" said Tommy. "I believe you'll write a book one of these days."

Monck looked ironical. "Not till I'm on the shelf, Tommy," he said, "where there's nothing better to do."

"You'll never be on the shelf," said Tommy quickly. "You'll be much too valuable."

Monck shrugged his shoulders slightly and turned to go. "I doubt if that consideration would occur to any one but you, my boy," he said.

They walked to the mess-house together a little later through the airless dark, and there was nothing in Monck's manner either then or during the evening to confirm the doubt in Tommy's mind. Spirits were not very high at the mess just then. Nearly all the women had left for the Hills, and the increasing heat was beginning to make life a burden. The younger officers did their best to be cheerful, and one of them, Bertie Oakes, a merry, brainless youngster, even proposed an impromptu dance to enliven the proceedings. But he did not find many supporters. Men were tired after the polo. Colonel Mansfield and Major Burton were deeply engrossed with some news that had been brought by Barnes of the Police, and no one mustered energy for more than talk.

Tommy soon decided to leave early and return to his letters. Before departing, he looked round for Monck as was his custom, but finding that he and Captain Ermsted had also been drawn into the discussion with the Colonel, he left the mess alone.

Back in The Green Bungalow he flung off his coat and threw himself down in his shirt-sleeves on the verandah to read his sister's letter. The light from the red-shaded lamp streamed across the pages. Stella had written very fully of their wanderings, but her companion she scarcely mentioned.

It was like a gorgeous dream, she said. Each day seemed to bring greater beauties. They had spent the first two at Agra to see the wonderful Taj which of course was wholly beyond description. Thence they had made their way to Rawal Pindi where Ralph had several military friends to be introduced to his bride. It was evident that he was anxious to display his new possession, and Tommy frowned a little over that episode, realizing fully why Stella touched so lightly upon it. For some reason his dislike of Dacre was increasing rapidly, and he read the letter very critically. It was the first with any detail that she had written. From Rawal Pindi they had journeyed on to exquisite Murree set in the midst of the pines where only to breathe was the keenest pleasure. Stella spoke almost wistfully of this place; she would have loved to linger there.

"I could be happy there in perfect solitude," she wrote, "with just Peter the Great to take care of me." She mentioned the Sikh bearer more than once and each time with growing affection. "He is like an immense and kindly watch-dog," she said in one place. "Every material comfort that I could possibly wish for he manages somehow to procure, and he is always on guard, always there when wanted, yet never in the way."

Their time being limited and Ralph anxious to use it to the utmost, they had left Murree after a very brief stay and pressed on into Kashmir, travelling in a tonga through the most glorious scenery that Stella had ever beheld.

"I only wished you could have been there to enjoy it with me," she wrote, and passed on to a glowing description of the Hills amidst which they had travelled, all grandly beautiful and many capped with the eternal snows. She told of the River Jhelum, swift and splendid, that flowed beside the way, of the flowers that bloomed in dazzling profusion on every side—wild roses such as she had never dreamed of, purple acacias, jessamine yellow and white, maiden-hair ferns that hung in sprays of living green over the rushing waterfalls, and the vivid, scarlet pomegranate blossom that grew like a spreading fire.

And the air that blew through the mountains was as the very breath of life. Physically, she declared, she had never felt so well; but she did not speak of happiness, and again Tommy's brow contracted as he read.

For all its enthusiasm, there was to him something wanting in that letter—a lack that hurt him subtly. Why did she say so little of her companion in the wilderness? No casual reader would have dreamed that the narrative had been written by a bride upon her honeymoon.

He read on, read of their journey up the river to Srinagar, punted by native boatmen, and again, as she spoke of their sad, droning chant, she compared it all to a dream. "I wonder if I am really asleep, Tommy," she wrote, "if I shall wake up in the middle of a dark night and find that I have never left England after all. That is what I feel like sometimes—almost as if life had been suspended for awhile. This strange existence cannot be real. I am sure that at the heart of me I must be asleep."

At Srinagar, a native fête had been in progress, and the howling of men and din of tom-toms had somewhat marred the harmony of their arrival. But it was all interesting, like an absorbing fairy-tale, she said, but quite unreal. She felt sure it couldn't be true. Ralph had been disgusted with the hubbub and confusion. He compared the place to an asylum of filthy lunatics, and they had left it without delay. And so at last they had come to their present abiding-place in the heart of the wilderness with coolies, pack-horses, and tents, and were camped beside a rushing stream that filled the air with its crystal music day and night. "And this is Heaven," wrote Stella; "but it is the Heaven of the Orient, and I am not sure that I have any part or lot in it. I believe I shall feel myself an interloper for all time. I dread to turn each corner lest I should meet the Angel with the Flaming Sword and be driven forth into the desert. If only you were here, Tommy, it would be more real to me. But Ralph is just a part of the dream. He is almost like an Eastern potentate himself with his endless cigarettes and his wonderful capacity for doing nothing all day long without being bored. Of course, I am not bored, but then no one ever feels bored in a dream. The lazy well-being of it all has the effect of a narcotic so far as I am concerned. I cannot imagine ever feeling active in this lulling atmosphere. Perhaps there is too much champagne in the air and I am never wholly sober. Perhaps it is only in the desert that any one ever lives to the utmost. The endless singing of the stream is hushing me into a sweet drowsiness even as I write. By the way, I wonder if I have written sense. If not, forgive me! But I am much too lazy to read it through. I think I must have eaten of the lotus. Good-bye, Tommy dear! Write when you can and tell me that all is well with you, as I think it must be—though I cannot tell—with your always loving, though for the moment strangely bewitched, sister, Stella."

Tommy put down the letter and lay still, peering forth under frowning brows. He could hear Monck's footsteps coming through the gate of the compound, but he was not paying any attention to Monck for once. His troubled mind scarcely even registered the coming of his friend.

Only when the latter mounted the steps on to the verandah and began to move along it, did he turn his head and realize his presence. Monck came to a stand beside him.

"Well, Tommy," he said, "isn't it time to turn in?"

Tommy sat up. "Oh, I suppose so. Infernally hot, isn't it? I've been reading Stella's letter."

Monck lodged his shoulder against the window-frame. "I hope she is all right," he said formally.

His voice sounded pre-occupied. It did not convey to Tommy the idea that he was greatly interested in his reply.

He answered with something of an effort. "I believe she is. She doesn't really say. I wish they had been content to stay at Bhulwana. I could have got leave to go over and see her there."

"Where exactly are they now?" asked Monck.

Tommy explained to the best of his ability. "Srinagar seems their nearest point of civilization. They are camping in the wilderness, but they will have to move before long. Dacre's leave will be up, and they must allow time to get back. Stella talks as if they are fixed there for ever and ever."

"She is enjoying it then?" Monck's voice still sounded as if he were thinking of something else.

Tommy made grudging reply. "I suppose she is, after a fashion. I'm pretty sure of one thing." He spoke with abrupt force. "She'd enjoy it a deal more if I were with her instead of Dacre."

Monck laughed, a curt, dry laugh. "Jealous, eh?"

"No, I'm not such a fool." The boy spoke recklessly. "But I know—I can't help knowing—that she doesn't care twopence about the man. What woman with any brains could?"

"There's no accounting for women's tastes or actions at any time," said Monck. "She liked him well enough to marry him."

Tommy made an indignant sound. "She was in a mood to marry any one. She'd probably have married you if you'd asked her."

Monck made an abrupt movement as if he had lost his balance, but he returned to his former position immediately. "Think so?" he said in a voice that sounded very ironical. "Then possibly she has had a lucky escape. I might have been moved to ask her if she had remained free much longer."

"I wish to Heaven you had!" said Tommy bluntly.

And again Monck uttered his short, sardonic laugh. "Thank you, Tommy," he said.

There fell a silence between them, and a hot draught eddied up through the parched compound and rattled the scorched twigs of the creeping rose on the verandah with a desolate sound, as if skeleton hands were feeling along the trellis-work. Tommy suppressed a shudder and got to his feet.

In the same moment Monck spoke again, deliberately, emotionlessly, with a hint of grimness. "By the way, Tommy, I've a piece of news for you. That letter I had from my brother this, evening contained news of an urgent business matter which only I can deal with. It has come at a rather unfortunate moment as Barnes, the policeman, brought some disturbing information this evening from Khanmulla and the Chief wanted to make use of me in that quarter. They are sending a Mission to make investigations and they wanted me to go in charge of it."

"Oh, man!" Tommy's eyes suddenly shone with enthusiasm. "What a chance!"

"A chance I'm not going to take," rejoined Monck dryly. "I applied for leave instead. In any case it is due to me, but Dacre had his turn first. The Chief didn't want to grant it, but he gave way in the end. You boys will have to work a little harder than usual, that's all."

Tommy was staring at him in amazement. "But, I say, Monck!" he protested. "That Mission business! It's the very thing you'd most enjoy. Surely you can't be going to let such an opportunity slip!"

"My own business is more pressing," Monck returned briefly.

Then Tommy remembered the stricken look that he had surprised on his friend's face that evening, and swift concern swallowed his astonishment. "You had bad news from Home! I say, I'm awfully sorry. Is your brother ill, or what?"

"No. It's not that. I can't discuss it with you, Tommy. But I've got to go. The Chief has granted me eight weeks and I am off at dawn." Monck made as if he would turn inwards with the words.

"You're going Home?" ejaculated Tommy. "By Jove, old fellow, it'll be quick work." Then, his sympathy coming uppermost again, "I say, I'm confoundedly sorry. You'll take care of yourself?"

"Oh, every care." Monck paused to lay an unexpected hand upon the lad's shoulder. "And you must take care of yourself, Tommy," he said. "Don't get up to any tomfoolery while I am away! And if you get thirsty, stick to lime-juice!"

"I'll be as good as gold," Tommy promised, touched alike by action and admonition. "But it will be pretty beastly without you. I hate a lonely life, and Stella will be stuck at Bhulwana for the rest of the hot weather when they get back."

"Well, I shan't stay away for ever," Monck patted his shoulder and turned away. "I'm not going for a pleasure trip, and the sooner it's over, the better I shall be pleased."

He passed into the room with the words, that room in which Stella had sat on her wedding-eve, gazing forth into the night. And there came to Tommy, all-unbidden, a curious, wandering memory of his friend's face on that same night, with eyes alight and ardent, looking upwards as though they saw a vision. Perplexed and vaguely troubled, he thrust her letter away into his pocket and went to his own room.

The Heaven of the Orient! It was a week since Stella had penned those words, and still the charm held her, the wonder grew. Never in her life had she dreamed of a land so perfect, so subtly alluring, so overwhelmingly full of enchantment. Day after day slipped by in what seemed an endless succession. Night followed magic night, and the spell wound closer and ever closer about her. She sometimes felt as if her very individuality were being absorbed into the marvellous beauty about her, as if she had been crystallized by it and must soon cease to be in any sense a being apart from it.

The siren-music of the torrent that dashed below their camping-ground filled her brain day and night. It seemed to make active thought impossible, to dull all her senses save the one luxurious sense of enjoyment. That was always present, slumbrous, almost cloying in its unfailing sweetness, the fruit of the lotus which assuredly she was eating day by day. All her nerves seemed dormant, all her energies lulled. Sometimes she wondered if the sound of running water had this stultifying effect upon her, for wherever they went it followed them. The snow-fed streams ran everywhere, and since leaving Srinagar she could not remember a single occasion on which they had been out of earshot of their perpetual music. It haunted her like a ceaseless refrain, but yet she never wearied of it. There was no thought of weariness in this mazed, dream-world of hers.

At the beginning of her married life, so far behind her now that she scarcely remembered it, she had gone through pangs of suffering and fierce regret. Her whole nature had revolted, and it had taken all her strength to quell it. But that was long, long past. She had ceased to feel anything now, but a dumb and even placid acquiescence in this lethargic existence, and Ralph Dacre was amply satisfied therewith. He had always been abundantly confident of his power to secure her happiness, and he was blissfully unconscious of the wild impulse to rebellion which she had barely stifled. He had no desire to sound the deeps of her. He was quite content with life as he found it, content to share with her the dreamy pleasures that lay in this fruitful wilderness, and to look not beyond.

He troubled himself but little about the future, though when he thought of it that was with pleasure too. He liked, now and then, to look forward to the days that were coming when Stella would shine as a queen—his queen—among an envious crowd. Her position assured as his wife, even Lady Harriet herself would have to lower her flag. And how little Netta Ermsted would grit her teeth! He laughed to himself whenever he thought of that. Netta had become too uppish of late. It would be amusing to see how she took her lesson.

And as for his brother-officers, even the taciturn Monck had already shown that he was not proof against Stella's charms. He wondered what Stella thought of the man, well knowing that few women liked him, and one evening, as they sat together in the scented darkness with the roar of their mountain-stream filling the silences, he turned their fitful conversation in Monck's direction to satisfy his lazy curiosity in this respect.

"I suppose I ought to write to the fellow," he said, "but if you've written to Tommy it's almost the same thing. Besides, I don't suppose he would be in the smallest degree interested. He would only be bored."

There was a pause before Stella answered; but she was often slow of speech in those days. "I thought you were friends," she said.

"What? Oh, so we are." Ralph Dacre laughed, his easy, complacent laugh. "But he's a dark horse, you know. I never know quite how to take him. Your brother Tommy is a deal more intimate with him than I am, though I have stabled with him for over four years. He's a very clever fellow, there's no doubt of that—altogether too brainy for my taste. Clever fellows always bore me. Now I wonder how he strikes you."

Again there was that slight pause before Stella spoke, but there was nothing very vital about it. She seemed to be slow in bringing her mind to bear upon the subject. "I agree with you," she said then. "He is clever. And he is kind too. He has been very good to Tommy."

"Tommy would lie down and let him walk over him," remarked Dacre. "Perhaps that is what he likes. But he's a cold-blooded sort of cuss. I don't believe he has a spark of real affection for anybody. He is too ambitious."

"Is he ambitious?" Stella's voice sounded rather weary, wholly void of interest.

Dacre inhaled a deep breath of cigar-smoke and puffed it slowly forth. His curiosity was warming. "Oh yes, ambitious as they're made. Those strong, silent chaps always are. And there's no doubt he will make his mark some day. He is a positive marvel at languages. And he dabbles in Secret Service matters too, disguises himself and goes among the natives in the bazaars as one of themselves. A fellow like that, you know, is simply priceless to the Government. And he is as tough as leather. The climate never touches him. He could sit on a grille and be happy. No doubt he will be a very big pot some day." He tipped the ash from his cigar. "You and I will be comfortably growing old in a villa at Cheltenham by that time," he ended.

A little shiver went through Stella. She said nothing and silence fell between them again. The moon was rising behind a rugged line of snow-hills across the valley, touching them here and there with a silvery radiance, casting mysterious shadows all about them, sending a magic twilight over the whole world so that they saw it dimly, as through a luminous veil. The scent of Dacre's cigar hung in the air, fragrant, aromatic, Eastern. He was sleepily watching his wife's pure profile as she gazed into her world of dreams. It was evident that she took small interest in Monck and his probable career. It was not surprising. Monck was not the sort of man to attract women; he cared so little about them—this silent watcher whose eyes were ever searching below the surface of Eastern life, who studied and read and knew so much more than any one else and yet who guarded knowledge and methods so closely that only those in contact with his daily life suspected what he hid.

"He will surprise us all some day," Dacre placidly reflected. "Those quiet, ambitious chaps always soar high. But I wouldn't change places. with him even if he wins to the top of the tree. People who make a specialty of hard work never get any fun out of anything. By the time the fun comes along, they are too old to enjoy it."

And so he lay at ease in his chair, feasting his eyes upon his young wife's grave face, savouring life with the zest of the epicurean, placidly at peace with all the world on that night of dreams.

It was growing late, and the moon had topped the distant peaks sending a flood of light across the sleeping valley before he finally threw away the stump of his cigar and stretched forth a lazy arm to draw her to him.

"Why so silent, Star of my heart? Where are those wandering thoughts of yours?"

She submitted as usual to his touch, passively, without enthusiasm. "My thoughts are not worth expressing, Ralph," she said.

"Let us hear them all the same!" he said, laying his head against her shoulder.

She sat very still in his hold. "I was only watching the moonlight," she said. "Somehow it made me think—of a flaming sword."

"Turning all ways?" he suggested, indolently humorous. "Not driving us forth out of the garden of Eden, I hope? That would be a little hard on two such inoffensive mortals as we are, eh, sweetheart?"

"I don't know," she said seriously. "I doubt if the plea of inoffensiveness would open the gates of Heaven to any one."

He laughed. "I can't talk ethics at this time of night, Star of my heart. It's time we went to our lair. I believe you would sit here till sunrise if I would let you, you most ethereal of women. Do you ever think of your body at all, I wonder?"

He kissed her neck with the careless words, and a quick shiver went through her. She made a slight, scarcely perceptible movement to free herself.

But the next moment sharply, almost convulsively, she grasped his arm. "Ralph! What is that?"

She was gazing towards the shadow cast by a patch of flowering azalea in the moonlight about ten yards from where they sat. Dacre raised himself with leisurely self-assurance and peered in the same direction. It was not his nature to be easily disturbed.