SWAN RIVER.

SWAN RIVER.

Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 480, March 12, 1831

Author: Various

Release date: June 1, 2004 [eBook #12597]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram, David Garcia, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Vol. 17, No. 480, Saturday, March 12, 1831, by Various

| VOL. XVII, NO. 480.] | SATURDAY, MARCH 12, 1831. | [PRICE 2d. |

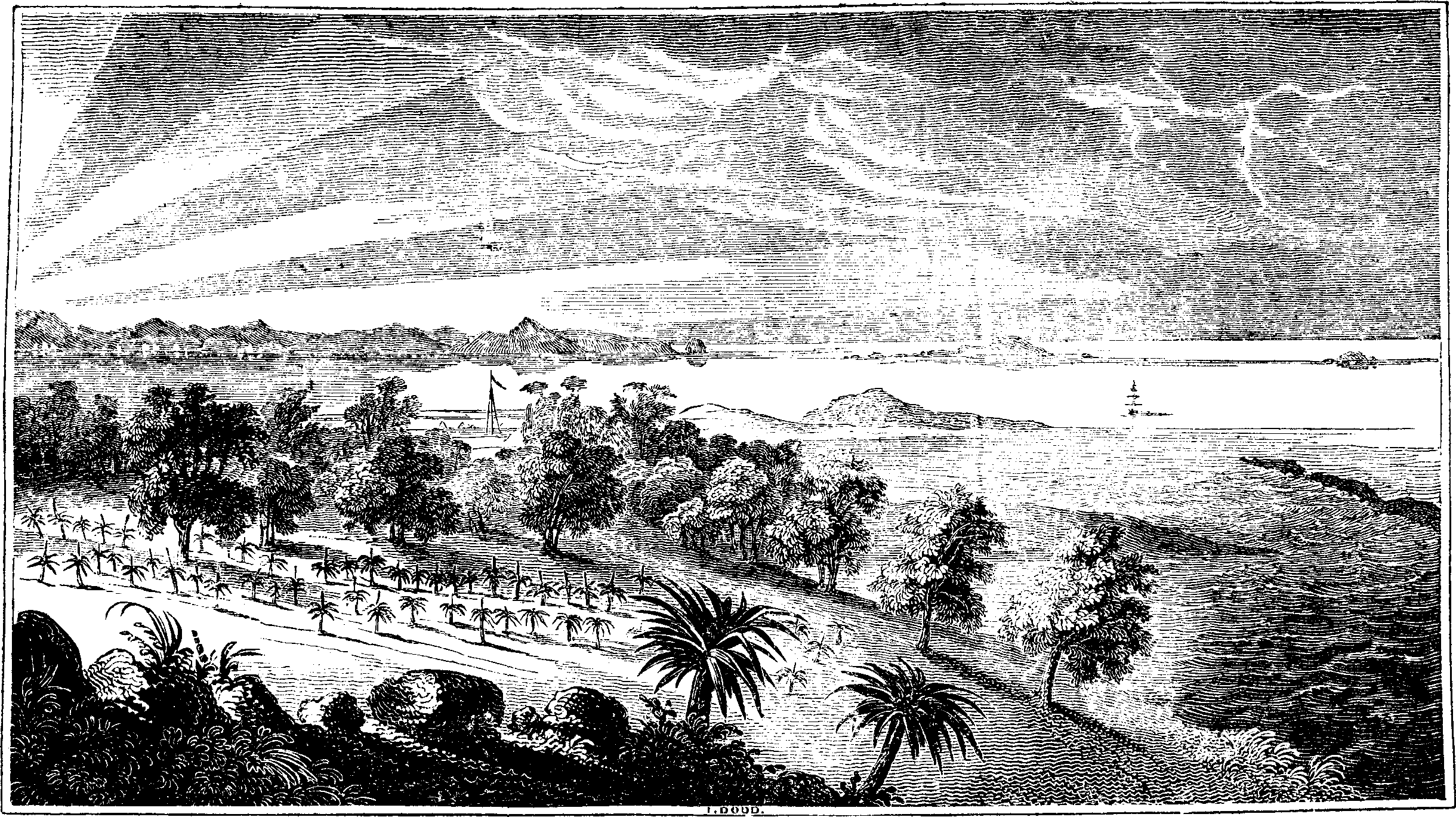

"A view in Western Australia, taken from a hill, the intended site of a Fort, on the left bank of the Swan River, a mile and a quarter from its mouth. The objects are, on the left, in the distance, Garden Island, that on the right of it Pulo Carnac; between the two is the only known entrance for shipping into Cockburn Sound, which lies between Garden Island and the main land; the anchorage being off the island. On the right is the mouth of the Swan River. On the left, a temporary mud work, overlooking a small bay where the troops disembarked. In the foreground tis a road leading to the intended fort and cantonment on the river."

Few subjects in our recent volumes have excited more attention than the facts we have there assembled relative to the New Colony on Swan River. The most substantial and agreeable proofs of this popularity have been the frequent reprints of the Numbers containing these Notices, and the continued inquiries for them to the present moment. For the information of such persons as are casual purchasers of our work, we subjoin the numbers:

No. 368 and 369 contain the papers (abridged) from the Quarterly Review, with the Regulations issued from the Colonial Office; and an Engraved Chart which is more correct than that in the Q. Rev.

Nos. 410 and 411 contain an Engraved View on the Banks of the River, from an original drawing by one of the expedition; and a copy of Mr. Fraser's Report of the Botanical and other productions of the Colony.

No. 430 contains an important Letter from the Colony.

No. 464 contains an account (with extracts,) of the first Newspaper written, not printed, in the settlement.

The annexed Engraving is from a well-drawn lithograph distributed with No. 12 of the Foreign Literary Gazette date March, 1830; the support of which work by the public was by no means commensurate with its claims.

The letter-press with which the Engraving was circulated contains little beyond the earliest settlement. The most recently received account is that conveyed through the Literary Gazette, a fortnight since; and as no paper is more to be relied on for information connected with expeditions of discovery, colonial matters, &c. we extract nearly the whole of the communication:—

Perth Town, Swan River, Western Australia, Oct. 4, 1830.

My dear ——, a ship being about to sail in the course of a week for England, I must not lose the opportunity of giving you a few lines respecting our movements and the state of the colony. I am somewhat late in my communications to my friends; but as this is the second ship only that has sailed direct for England since our arrival, you must not attribute the delay to any neglect on my part. The information which I can give you may be implicitly depended on. By the late accounts from England, it appears that the most exaggerated and false reports prevail regarding the present state and probable prospects of the colony, like all other reports that are a mixture of truth and falsehood; and as it is usual to paint the latter in the brightest colours, so it usually stands foremost in the picture: they have been industriously disseminated by a set of idle, worthless vagabonds, and have been eagerly taken up by the inhabitants of Cape Town and Van Dieman's Land.—These two places are so excessively jealous of the colony of Swan River, lest the tide of emigration should turn towards us, that the former use every means in their power to induce the settlers in their way here to remain with them; and they have been, I am sorry to say, too successful, having detained nearly two hundred labourers. The grounds of complaint are, that the colony is not equal to the representations given of it, and that it has not answered their expectations. The account in the Quarterly Review, as far as it goes, is correct, with one exception; but the impression it is calculated to make, when in unison with the hopes of needy adventurers, is too favourable to be realized. The Review observes, that the land seen on the banks of the Swan is of a very superior description; and this is undoubtedly true; but the imagination and enthusiastic feelings of many have induced them to suppose that all the land on the banks of the Swan, and the whole country besides, is included in that description. Now, the good land is chiefly confined to the banks of the rivers, as you will see by a map which I have sent to ——; the rest is sandy, but it is covered throughout the year with luxuriant vegetation. The cause of this arises in some measure from the composition of the soil beneath, which, at an average depth of five or six feet, is principally clay, which holds the water in lagoons, that are to be met with in every hollow in every part of the [pg 179] country on this side the mountains. It unfortunately happens that none of the good land is to be seen even as far up the river as Perth, the whole soil of which is sandy; hence all new-comers are at first disappointed; and, without taking any further trouble to examine the country, leave the colony in disgust altogether. But it has now been found that the land at Perth, notwithstanding its unpromising appearance, possesses capabilities which intelligent and experienced persons foresaw, and that it only requires time and patience to develope its surprising qualities: at this moment there are vegetables growing to an enormous size, scarcely credible, and which for the sake of truth I actually measured. What say you to radishes twenty inches round, and grown in nothing but sand, without any manure or preparation of the ground? Turnips, cabbages, peas, lettuces, all flourish in the worst soils here; but I fear the climate is too warm for potatoes, though well adapted for most of the tropical fruits, as yams, bananas, &c.

The soil and aspect of the country seems well suited for the vine, which, from the little experience we have had, does exceedingly well. There are no esculent productions worth mentioning indigenous, but there is some fine timber, which will no doubt become a valuable article of exportation: it is between the mahogany and the elder, and may be applied to all the purposes of the former. Its greatest recommendation is, that the white ant will not touch it, and it will consequently be a great desideratum where that insect abounds. We have likewise the red and blue gum, but in no great quantity, in the immediate vicinity of Perth. The animal productions are the same as on the other side of the island, as also the birds. The rivers swarm with fish, every one of which is good eating; but it is only lately that we have been well supplied with them. There is abundance of limestone ready at hand in most parts of the river, as well as the finest and strongest clay, plenty of which runs along the shore that bounds Perth, for a mile and a half, as you will see by the map. Of the mineral resources of the country nothing is as yet known; for every one has been too much occupied in locating himself to give that subject any attention. By the reports from England, it appears that from the misfortunes which happened to the first ships that came out, a very unfavourable opinion is formed of the safety of the port. Gage's roads afford a very good anchorage during the summer months; but, being exposed to the north-west winds, it is a very insecure station during the winter, the ground being rocky and a loose sand; but this evil, I am happy to say, is in a great measure obviated by the discovery of a good anchorage about four miles to the southward of the mouth of the river, and marked in the map as the Britannia Roads. The bottom is firm holding ground, and has been proved to be a very secure anchorage during the late gales, when all the ships in Gage's Roads went on shore, while those on the Britannia Roads rode it out, with the exception of one ship, which broke her anchor. Besides, a passage has lately been found out from Gage's Roads to Cockburn, into which ships may run, if they are too much leeward of the Britannia Roads; so that you see we may always have a refuge from the storm. I hope you will take care to give publicity to this circumstance, because it is one upon which the success of the colony mainly depends. The bar at the mouth of the river, and the flats in various parts of its course, are a great drawback to our communications; but these evil will no doubt be remedied in the course of time, and that without much expense. There is a clear channel all the way up the river for vessels of 500 tons, commencing about a mile and a half above Freemantle to Perth; then there are a succession of flats until you pass the islands, where the navigation continues clear for many miles up the river.

The prospects of the colony are every day improving, to the satisfaction of all classes; and the great number of respectable settlers, and their patience and perseverance in establishing themselves, are the surest grounds for the ultimate prosperity of the settlement. The only objections, as I can see, that can be urged with any degree of plausibility against the success of the colony, are, that the land at Perth and in the neighbourhood is not of that description to induce the settlers to cultivate, and that all the good land being now granted, there is no more on this side the mountains to satisfy the demands of new settlers; but these objections are, I am happy to say, about to be removed, as an ensign of the 63rd regiment (a Mr. Dale) has lately returned from a tour of discovery into the interior, and has brought intelligence, that to the eastward of the Swan River there is a large and fertile tract of beautiful country, with a river passing through it, which, from a subsequent visit by Mr. Erskine, [pg 180] a lieutenant of the 63rd, is likely to prove of the greatest importance to the colony. Those of the settlers who have not taken up their grants of land mean to secure them here, and myself among the number, a grant having been allowed me, at the rate of 3,200 acres. The governor is quite delighted, and now considers the ultimate success of the colony to be certain. He intends visiting the country, and tracing the course of the river, in a few days; and it is my wish to accompany him, if possible, that I may select my own grant.

The spirit of detraction to which the writer alludes in the early part of his letter is thus noticed in the Cabinet Cyclopaedia, vol. iii. of Maritime and Inland Discovery: "The difficulties and embarrassments which the settlers at the Swan River have been obliged to endure, have been industriously exaggerated by the colonial press; the strong desire which exists in New South Wales to attract emigrants to that country being naturally allied with a disposition to disparage every other settlement."

I am no pilgrim unto Becket's shrine,

To kneel with fervour on his knee-worn grave,

And with my tears his sainted ashes lave,

Yet feel devotion rise no less divine—

As rapt I gaze from Harbledown's decline

And view the rev'rend temple where was shed

That pamper'd prelate's blood—his marble bed

Midst pillar'd pomp, where rainbow windows shine;

Where bent the 1anointed of a nation's throne

And brooked the lashes of the church's ire;

And where, as yesterday, with soul of fire,

Transcendent Byron view'd the hallow'd stone.

Sure Chaucer's pilgrims, on this crowning height,

Repress'd their mirth, and kindled at the sight.

Couch'd in the bosom of a bounteous vale,

The ancient city, to the enamour'd sight,

Gleams like a vision of the fairy night,

Or Be-ulah, in Banyan's holy tale.

The silvery clouds that o'er the valley sail

Dim not the sinking sun, whose lustre fires

The old cathedral and its gorgeous spires,

The ruin'd abbey, garlanded and pale

The vesper choristers in each lone wood

Chant to the peeping moon their serenade;

Now creeps the far-off forest into shade,

And twilight comes o'er heath, and field, and flood.

Oh! had I genius now the task to try,

My picture should Italian Claude's outvie!

In no. 477 of the Mirror you have given a spirited engraving of Mount St. Michael, with a succinct account annexed, to which the following particulars may serve as addenda:—

Its most ancient name was Belinus, when it was inhabited by Druidesses. After the abolition of the Druids, it took the name of Mons Jovis; to which was substituted that of Tumba, when a monastery was erected upon it. In 708, Bishop Auber raised upon it a church, which he dedicated to St. Michael.—Ethelred, the second, of England, had a particular veneration for Mount St. Michael. Abbot Roger had been almoner to William the Conqueror. Henry II. of England made a pilgrimage to Mount St. Michael, when he met Louis VII. King of France, with a splendid suite.

In 1203 the fortifications consisted only of wooden palisades. Being attacked by the Bretons, they set fire to them: the fire reached the church and abbey, which was completely destroyed. The monastery was restored in 1226, by Abbot Adulph de Villedieu. His successor, Richard Justin, obtained from the Pope the most distinguished privileges.

In 1418 the English made a fruitless attack upon it.

In 1423 it was attempted again, with a very considerable force and powerful artillery, two pieces of which now stand at the main gate: one has a stone ball in it of about fifteen inches diameter. Among the distinguished English officers who perished at the siege, was a Chevalier M. Burdet.

In 1577 a Protestant chief (Dutouchet) succeeded by stratagem in getting possession of it. After two day's possession, he was obliged to evacuate it.

In 1591 a similar attempt proved most destructive to the assailants.

In 1594, the spire, the bells, and the church, were considerably injured by lightning.

Mount St. Michael was visited in 1518 by Francis I. of France; in 1561, by Charles IX.; in 1576, by the Duchess de Bourbon; in 1624, by the Duke de Nevers, who made a rich present to the abbey; in 1689, by Madame de Levigné, who designated it Le Mont fier et orgueilleux. In 1689, Philip Duke of Orleans, brother to Louis XIV., was one of its visiters.

The most remarkable circumstance is the visit paid to it on the 10th of May, 1777, by the Ex-King of France, the Count d'Artois (twenty years old). On [pg 181] inspecting the state-prison, a wooden cage was shown to him. The prince, struck with horror at the sight of it, ordered it to be destroyed. Shortly after, the young princes of Orleans, among whom the present King Philip, accompanied by Madame de Lillery, stopped at Mount St. Michael. After having inspected the subterraneous passages and magazines, the wooden cage was shown to them. They asked for workmen and axes, and giving the first blow themselves, this infernal machine was completely destroyed.

The prior of the abbey was formerly governor of the town and castle, and the keys were brought to him every evening. It gives name to the late military order of St. Michael, founded by Louis XI, in 1479. The view from the summit is fine, embracing the coasts of Normandy and Britanny, with the town and ruins of the cathedral of Avranches, elevated on a mountain, and the intervening valley, with the open sea of the British Channel.

Though rough, not lengthened, is our worldly way;

Then wipe thy pearly eyes, no more to weep—

Thy feet from falling let this memory keep—

Our love hath lasted through the stormy day.

These clouds like early mist shall melt away,

And show the vale beyond the pointed steep;

For they who sow in tears, in smiles shall reap—

Then be thy spirits as the morning gay.

For thou alone art gifted with the power

To still the tempest in my stubborn soul;

Thy smile creates around the billows roll

The blissful quiet of a halcyon hour.

Then shed no tear—then heave no sorrowing sigh

Since love like thine may time and toil defy.

In 478 of your entertaining little miscellany, I observe a short account of an unparalleled feat of riding, performed by John Lepton, of Reprich, in 1603. As I know you wish to be "quite correct," the following may be acceptable: it is copied verbatim from a scarce book (in my possession) entitled, "The Abridgement of the English Chronicle," by Edmund Howes, imprinted at London, 1668 (15th James I.):—

"In this month, John Lenton, of Kepwick, in the county of Yorke, Esq., a gentleman of an ancient family there, and of good reputation, his majesty's servant, and one of the grooms of his most honourable privy chamber, performed so memorable a journey as I may not omit to record the same to future ages; the rather for that I did hear sundry gentlemen, who were good horsemen, and likewise many good physicians, affirm it was impossible to be done without danger of his life.

"He undertook to ride five several times betwixt London and Yorke, in sixe dayes, to be taken in one weeke, between Monday morning and Saturday following. He began his journey upon Monday, being the 29th of May, betwixt two and three of the clock in the morning, forthe of St. Martin's, neere to Aldersgate, within the city of London, and came into Yorke the same day, between the hours of 5 and 6 in the afternoon, where he rested that night. The next morning, being Tuesday, about 3 of the clock he tooke his journey forthe of Yorke, and came to lodgings in St. Martins aforesaid, betwixt the hours of 6 and 7 in the afternoon, where he rested that night. The next morning, being Wednesday, betwixt 2 and 3 of the clock, he tooke his journey for the of the city of London, and came into Yorke about 7 of the clock the same day, where he rested that night. The next morning, being Thursday, betwixt 2 and 3 of the clock he tooke his journey forthe of Yorke, and came to London the same day betwixt 7 and 8 of the clock. The next day, being Friday, betwixt 2 and 3 of the clock he tooke his journey towards Yorke, and came thither the same day, betwixt the hours of 7 and 8 in the afternoon. So as he finished his appointed journey (to the admiration of all men, in five days, according to his promise). And upon Monday, the 27th of this month, he went from Yorke, and came to the court of Greenwich upon Tuesday the 28th, to his majesty, in as fresh and cheerful a manner as when he began."

"I'll sing you a new song to-night."

I'll sing you a new song to-night,

I'll wake a joyous strain,

An air to kindle keen delight,

And banish silent pain;

Bright thoughts shall chase the clouds of care,

And gloom of deepest sadness,

For oh! my spirit loves to wear

The sunny ray of gladness.

I love to mix alone with those,

Whose hearts are wildly free,

For human griefs, and human woes,

Are strangers yet to me;

I will not early learn to pine

My summer life away,

But ever bend at pleasure's shrine,

And mingle with the gay.

Should sorrow come with coming years,

And touch the strings of woe,

I'll learn to smile away its tears,

Or check their idle flow;

And still I'll sing; a song as bright,

And wake as glad a measure,

Bid grief and sorrow wing their flight,

And hail the reign of pleasure.

When the sulphate of iron and the infusion of galls are added together, for the purpose of forming ink, we may presume that the metallic salt or oxide enters into combination with at least four proximate vegetable principles—gallic acid, tan, mucilage, and extractive matter—all of which appear to enter into the composition of the soluble parts of the gall-nut. It has been generally supposed, that two of these, gallic acid and the tan, are more especially necessary to the constitution of ink; and hence it is considered, by our best systematic writers, to be essentially a tanno-gallate of iron. It has been also supposed that the peroxide of iron alone possesses the property of forming the black compound which constitutes ink, and that the substance of ink is rather mechanically suspended in the fluid than dissolved in it.

Ink, as it is usually prepared, is disposed to undergo certain changes, which considerably impair its value. Of these the three following are the most important: its tendency to moulding, the liability of the black matter to separate from the fluid, the ink then becoming what is termed ropy, and its loss of colour, the black first changing to brown, and, at length, almost entirely disappearing.

Besides these, there are objects of minor importance to be attended to in the formation of ink. Its consistence should be such as to enable it to flow easily from the pen, without, on the one hand, its being so liquid as to blur the paper, or, on the other, so adhesive as to clog the pen, and to be long in drying. The shade of colour is also not to be disregarded: a black, approaching to blue, is more agreeable to the eye than a browner ink; and a degree of lustre, or glossiness, if compatible with the due consistence of the fluid, tends to render the characters more legible and beautiful. With respect to the chemical constitution of ink, I may remark, that although, as usually prepared, it is a combination of the metallic salt or oxide, with all the four vegetable principles mentioned above; yet I am inclined to believe that the last three of them, so far from being essential, are the principal cause of the difficulty which we meet with in the formation of a perfect and durable ink. I endeavoured to prove this point by a series of experiments, of which the following is a brief abstract:—Having prepared a cold infusion of galls, I allowed a portion of it to remain exposed to the atmosphere, in a shallow capsule, until it was covered with a thick stratum of mould; the mould was removed by filtration, and the proper proportion of sulphate of iron being added to the clear fluid, a compound was formed of a deep black colour, which showed no farther tendency to mould, and which remained for a long time without experiencing any alteration.

Another portion of the same infusion of galls had solution of isinglass added to it until it no longer produced a precipitate; by employing the sulphate of iron, a black compound was produced, which, although paler than that formed from the entire fluid, appeared to be a perfect and durable ink. Lastly, a portion of the infusion of galls was kept for some time at the boiling temperature, by means of which a part of its contents became insoluble; this was removed by filtration, when, by the addition of the sulphate of iron, a very perfect and durable ink was produced. In the above three processes I conceive that a considerable part of the mucilage, the tan, and the extract, were respectively removed from the infusion, while the greater part of the gallic acid would be left in solution.

The three causes of deterioration in ink, the moulding, the precipitation of the black matter, and the loss of colour, as they are distinct operations, so we may presume that they depend on the operation of different proximate principles. It is probable that the moulding more particularly depends on the mucilage; and the precipitation on the extract, from the property which extractive matter possesses of forming insoluble compounds with metallic oxides. As to [pg 183] the operation of the tan, from its affinity for metallic salts, we may conjecture, that, in the first instance, it forms a triple compound with the gallic acid and the iron; and that, in consequence of the decomposition of the tan, this compound is afterwards destroyed. Owing to the difficulty, if not impossibility, of entirely depriving the infusion of galls of any one of its ingredients, without, in some degree, affecting the others, I was not able to obtain any results which can be regarded as decisive; but the general result of my experiments favours the above opinion, and leads me to conclude, that, in proportion as ink consists merely of the gallate of iron, it is less liable to decomposition, or to experience any kind of change.

The experiments to which I have alluded above, consisted in forming a standard infusion by macerating the powder of galls in five times its weight in water, and comparing this with other infusions, which had either been suffered to mould, from which the tan had been extracted by gelatine, or which had been kept for some time at the boiling temperature; and by adding to each of these respectively, both the recent solution of the sulphate of iron, and a solution of it, which had been exposed for some time to the atmosphere. The nature of the black compound produced was examined by putting portions of it into cylindrical jars, and observing the changes which they experienced with respect either to the formation of mould, the deposition of their contents, or any change of colour. The fluids were also compared by dropping portions of them upon white tissue paper, in which way both their colour and their consistence might be minutely ascertained. A third method was, to add together the respective infusions, and the solutions of the sulphate of iron, in a very diluted state, by which I was enabled to form a more correct comparison of the quantity, and of the state of the colouring matter, and of the degree of its solubility.

The practical conclusions that I think myself warranted in drawing from these experiments, are as follow:—In order to procure an ink which may be little disposed either to mould or to deposit its contents, and which, at the same time, may possess a deep black colour, not liable to fade, the galls should be macerated for some hours in hot water, and the fluid be filtered; it should then be exposed for about fourteen days to a warm atmosphere, when any mould which may have been produced must be removed. A solution of sulphate of iron is to be employed, which has also been exposed for some time to the atmosphere, and which, consequently, contains a certain quantity of the red oxide of iron diffused through it. I should recommend the infusion of galls to be made of considerably greater strength than is generally directed; and I believe that an ink, formed in this manner, will not necessarily require the addition of any mucilaginous substance to render it of a proper consistence.

I have only further to add, that one of the best substances for diluting ink, if it be, in the first instance, too thick for use, or afterwards become so by evaporation, is a strong decoction of coffee, which appears in no respect to promote the decomposition of the ink, while it improves its colour, and gives it an additional lustre.

Once—whether in a dream, a waking vision, a poetical hallucination, or in sober reality, I know not—once was I favoured with a distinct and glorious vision of the Faries' Land! I found myself in a country more enchantingly beautiful than the warm, romantic dream of the poet has ever yet conceived:—therein bloomed trees, and plants, and flowers, in beauty and luxuriance never to fade; therein was the soft air strongly imbued with the ambrosial odour of the orient rose; but ever as a gentle breeze enfolded me, it seemed on its refreshing wings to bear the heavenly fragrance of unknown flowers. The sky was of an effulgent azure, altogether indescribable—but under the influence of stealing twilight, insensibly was it darkening, though the yet undimmed colours of sunset were inexpressibly varied and vivid. Radiant and exquisitely beautiful beings, fair miniatures of mortals, inhabited this charming region, wherein was assembled all that had power to inebriate the soul with pure and rapturous felicity, and imbue it with an intense perception of its immortality and blessedness. Now stole the faint, delicious sound of very distant bells—clear, silvery, and sweet—upon mine ear, as the tones of a well-touched harp: sad were they—luxuriously sad; and their unearthly melody infused into my bosom a repose unknown to mortality. As I listened with awe and rapture to that [pg 184] delicate minstrelsy, I seemed to become all soul; tears—far indeed from tears of sorrow—suffused my wondering eyes, and my heart, in the delirium of gratitude, raised itself in solemn thanksgivings to its Creator.

"Favoured mortal!" sighed near me a voice soft as a zephyr-breath. I turned, and beheld a constellation of the radiant inhabitants of this ethereal country clustered about a portal, whose frame-work was of shining stones, and whose firm, but slender bars, were of purest gold.—"Favoured mortal!" (the speaker was beside me)—"favoured beyond even thine own conception, know that thou art permitted to behold the Elfin Paradise—the true, the veritable Fairy Land. Pollute it not by the tone of mortal speech; to us are thy thoughts not unknown, and partially are we permitted to gratify thy desire for information. Thinkest thou—so indeed hath man taught thee—that this sweet world is but a vain illusion? Know then, that we, the Elfin Band, are, in the order of the universe, spirits inferior to the angels, but superior to thee. We are the creatures and servants of the Most High! (be His glorious name by all His infinite creation reverenced and adored!)—and we, in conjunction with the most exalted hierarchies of Heaven, are spirits, ministrant to man! Amongst us, alas! are evil and wretched Fays, whose terrible study it is to subvert our beneficent labours, to prevent our entrance into this ethereal region, and in their own desolate and accursed country to insult the veritable Fairy Land by employing their small remnant of celestial power in creating imitations of it, as paltry as absurd. Know also, O mortal! that whilst with, and for, man, we abide upon earth, we have no land, no home;—like himself, 'strangers and pilgrims' are we; nor is it until the period when our ministry is accomplished (and of the finale of that period are none of us informed) that we are wafted on the gentle breezes of heaven to this celestial planet, which, lighted by the same sun which blesseth your own, is too small to be visible to the eyes of its inquisitive philosophers. Hark! this day was a Fairy emancipated from earthly thraldom, and the bells of the Golden City are singing for joy!"

The voice died away in the breeze; yet still I listened, in the hope of hearing again those accents, as pure, distinct, and musical, as were the small, sweet harps which, seated on the greensward at no great distance from me, a group of Fays were tuning, whilst sundry light and rapid flourishes seemed to prelude an intended song. The bells of the City of the Fairies sunk one by one into silence; the scented breeze flowed languidly as dropping into slumber; a hush of nature pervaded the blessed region; and sad was my spirit to think that it could not dwell in this Elfin Eden for ever! A stream of melody now broke the holy quietness of the land, which resembled the aspirations of those who know neither sorrow nor sin. The breathing instruments sighed, rather than distinctly uttered, tones, according well with those fine and delicate voices which, as they stole in gentle words upon my entranced senses, were sweet and penetrating as the aroma of unfading flowers:—

Farewell! farewell! departing sun!

Thy disk is dim, thy course is run;

Long hast thou lit our land of flowers,—

Now, night must veil our hallow'd bowers.

Farewell bright sun! farewell sweet day!

We mourn not that ye glide away,

Since ev'ry fleeting hour doth bless

Where days and dreams are numberless.

Farewell bright sun! thou'lt wander forth

From hence, to east, and south, and north,

Till, weary of man's guilt and pain,

Thoul't turn thee to our land again.

Farewell sweet day! our songs shall hail

Thine earliest dawn so pure, and pale,—

For shadowy night ere long must, cease

To veil the pleasant Land of Peace.

My dear B.—On my return to the Neptune all was in readiness to set sail. The wind sprang up, and we were presently wafted into a broad sheet of water, "the Sea of Tappan." The river here suddenly expands, and for the distance of ten miles will average about four miles in breadth; in many places the water is so shallow, that the helmsman, his track being already marked out, steers by the direction of posts, stationed here and there in the river, that he may keep his vessel free from sand-banks. The shore on each side of us presented a level, agreeably interrupted in places by the intervention of minor hills, apparently fertile, and in fine cultivation. The villages of Tappan and Nyack, a few framed houses and huts scattered irregularly on the western side, and about one mile from the river, claim the attention of the traveller. They are [pg 185] situated near the foot of a valley, and overlooked by some stupendous and abrupt ridges, whose frowning and murky heads throw a grand and solemn, but somewhat suitable, aspect upon the landscape of this memorable place. Old Tappan, which consists of only two or three small houses, and lies a short distance up this valley, was the place selected for the execution of the once brave, noble-hearted, patriotic, and accomplished Major André. I was anxious to make a pilgrimage to the grave of my unfortunate countryman; and, as the wind was scarcely sufficient to bear us up against a strong ebb-tide, I easily prevailed on the captain to anchor his charge, and allow the small boat to go on shore.

Major André, you may recollect, was taken prisoner by the Americans during the revolution as a British spy. The house or hut in which he was kept in confinement had only very lately gone into ruins. It was then a tavern, and its landlord, now extremely old, still resides close by, and recites the melancholy tale with much affection and feeling. He witnessed the gentlemanly manners and equanimity of this heroic soldier, while in his house, under the most trying circumstances, and from its threshold to the fatal spot. In his room the prisoner could hear the sound of the axe employed in erecting the scaffold; and on one occasion, in the presence of a friend, when these sounds, terrible to all but himself, were more than usually distinct, he is said to have observed, with great composure, "that every sound he heard from that axe was indeed an important lesson, it taught him how to live and how to die." When conducted to the place of execution, and on coming near to the scaffold, he made a sudden halt, and momentarily shrunk at the sight; because he had, to the last, entertained hopes that his life would have been taken by the musket, and not by the halter. This apparent want of resolution quickly passed away, and the disappointment he felt told more against the uncompromising spirit of the times than against himself. Rejecting assistance, he approached and ascended the platform with a steady pace and lofty demeanour, and submitted to his fate with the pious resignation of a great and good man. A large concourse of spectators, among whom were several well dressed females, had assembled on this sorrowful occasion; and it is reported that scarcely a dry cheek could be found throughout the whole multitude. André was then seen as he always had been, and moved by that which had through life presided over all his actions, resolved beyond presumption, and firm without ostentation.

The person and appearance of Major André were prepossessing; he was well proportioned, and above the common size of men; the lines of his face were regular, well marked, and beautifully symmetrical, which gave him an expression of countenance at once dignified and commanding. His address was graceful and easy; in manners he was truly exemplary, and in conversation affable and instructive. Polite to all ranks and classes of people, he was universally respected; fond of discipline, and always alive to the just claims and feelings of others, he was beloved in the army, and generally appealed to as the common arbitrator and conciliator of the contentions of those around him. In a word, he was a sincere friend, a scholar, and accomplished gentleman, a patriot, a gallant soldier, an able commander, and a Christian.

General Washington, when called upon to sign his death-warrant, which he did not do without hesitation, it is said, dropped a tear upon the paper, and spoke at the same time to the following effect:—"That were it not infringing upon the duty and responsibility of his office, and disregarding the high prerogative of those who would fill that office after him, the tear, which now lay upon that paper, should annihilate the confirmation of an act to which his name would for ever stand as a sanction. He was summoned that day to do a deed at which his heart revolted; but it was required of him by the justice of his country, the desires and expectations of the people: he owed it to the cause in which he was solemnly engaged, to the welfare of an infant confederacy, the safety of a newly organized constitution which he had pledged his honour to protect and defend, and a right given to him that was acknowledged to be just by the ruling voice of all nations."

André, after he had heard his condemnation, addressed a letter to Washington; it contained a feeling appeal to him as a man, a soldier, and a general, on the mode of death he was to die. It was his wish to be shot. This, however, could not be granted: he had been taken and condemned as a spy, and the laws of nations had established the manner of his death. But where were the humanity and feeling of the British on this occasion? Why did they not give up the dastardly Arnold in exchange for [pg 186] the brave André; as it was generously proposed by the United States?3 This they refused on a paltry plea, and suffered, in consequence, the life of one of their finest officers to be ignominiously lost.

On a green eminence, over which hangs the dark and funereal shade of the willow, is the grave of this unfortunate soldier; it is a short distance south and west of the village. "No urn nor animated bust," only a few rough and unshapely stones, without a word of inscription, and carelessly laid upon a mound of rudely piled earth, are shown to the traveller as the spot where rest the remains of poor André.4

Complaints are frequently made of the vanity and shortness of human life, when, if we examine its smallest details, they present a world by themselves. The most trifling objects, retraced with the eye of memory, assume the vividness, the delicacy, and importance of insects seen through a magnifying glass. There is no end of the brilliancy or the variety. The habitual feeling of the love of life may be compared to "one entire and perfect chrysolite," which, if analyzed, breaks into a thousand shining fragments. Ask the sum-total of the value of human life, and we are puzzled with the length of the account, and the multiplicity of items in it: take any one of them apart, and it is wonderful what matter for reflection will be found in it! As I write this, the Letter-Bell passes: it has a lively, pleasant sound with it, and not only fills the street with its importunate clamour, but rings clear through the length of many half-forgotten years. It strikes upon the ear, it vibrates to the brain, it wakes me from the dream of time, it flings me back upon my first entrance into life, the period of my first coming up to town, when all around was strange, uncertain, adverse—a hub-*bub of confused noises, a chaos of shifting objects—and when this sound alone, startling me with the recollection of a letter I had to send to the friends I had lately left, brought me as it were to myself, made me feel that I had links still connecting me with the universe, and gave me hope and patience to persevere. At that loud tinkling, interrupted sound (now and then,) the long line of blue hills near the place where I was brought up waves in the horizon, a golden sunset hovers over them, the dwarf-oaks rustle their red leaves in the evening breeze, and the road from —— to ——, by which I first set out on my journey through life, stares me in the face as plain, but from time and change not less visionary and mysterious, than the pictures in the Pilgrim's Progress. I should notice, that at this time the light of the French Revolution circled my head like a glory, though dabbled with drops of crimson gore: I walked confident and cheerful by its side—

"And by the vision splendid

Was on my way attended."

It rose then in the east: it has again risen in the west. Two suns in one day, two triumphs of liberty in one age, is a miracle which I hope the laureate will hail in appropriate verse. Or may not Mr. Wordsworth give a different turn to the fine passage, beginning—

"What, though the radiance which was once so bright,

Be now for ever vanished from my sight;

Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of glory in the grass, of splendour in the flower?"

For is it not brought back, "like morn risen on mid-night;" and may he not yet greet the yellow light shining on the evening bank with eyes of youth, of genius, and freedom, as of yore? No, never! But what would not these persons give for the unbroken integrity of their early opinions—for one unshackled, uncontaminated strain—one Io paean to Liberty—one burst of indignation against tyrants and sycophants, who subject other countries to slavery by force, and prepare their own for it by servile sophistry, as we see the huge serpent lick over its trembling, helpless victim with its slime and poison, before it devours it! On every stanza so penned would be written the word RECREANT! Every taunt, every reproach, every note of exultation at restored light and freedom, would recall to them how their hearts failed [pg 187] them in the Valley of the Shadow of Death. And what shall we say to him—the sleep-walker, the dreamer, the sophist, the word-hunter, the craver after sympathy, but still vulnerable to truth, accessible to opinion, because not sordid or mechanical? The Bourbons being no longer tied about his neck, he may perhaps recover his original liberty of speculating; so that we may apply to him the lines about his own Ancient Mariner—

"And from his neck so free

The Albatross fell off, and sank

Like lead into the sea."

This is the reason I can write an article on the Letter-Bell, and other such subjects; I have never given the lie to my own soul. If I have felt any impression once, I feel it more strongly a second time; and I have no wish to revile and discard my best thoughts. There is at length a thorough keeping in what I write—not a line that betrays a principle or disguises a feeling. If my wealth is small, it all goes to enrich the same heap; and trifles in this way accumulate to a tolerable sum.—Or if the Letter-Bell does not lead me a dance into the country, it fixes me in the thick of my town recollections, I know not how long ago. It was a kind of alarm to break off from my work when there happened to be company to dinner or when I was going to the play. That was going to the play, indeed, when I went twice a year, and had not been more than half a dozen times in my life. Even the idea that any one else in the house was going, was a sort of reflected enjoyment, and conjured up a lively anticipation of the scene. I remember a Miss D——, a maiden lady from Wales (who in her youth was to have been married to an earl,) tantalized me greatly in this way, by talking all day of going to see Mrs. Siddons' "airs and graces" at night in some favourite part; and when the Letter-Bell announced that the time was approaching, and its last receding sound lingered on the ear, or was lost in silence, how anxious and uneasy I became, lest she and her companion should not be in time to get good places—lest the curtain should draw up before they arrived—and lest I should lose one line or look in the intelligent report which I should hear the next morning! The punctuating of time at that early period—every thing that gives it an articulate voice—seems of the utmost consequence; for we do not know what scenes in the ideal world may run out of them: a world of interest may hang upon every instant, and we can hardly sustain the weight of future years which are contained in embryo in the most minute and inconsiderable passing events. How often have I put off writing a letter till it was too late! How often had to run after the postman with it—now missing, now recovering, the sound of his bell—breathless, angry with myself—then hearing the welcome sound come full round a corner—and seeing the scarlet costume which set all my fears and self-reproaches at rest! I do not recollect having ever repented giving a letter to the postman, or wishing to retrieve it after he had once deposited it in his bag. What I have once set my hand to, I take the consequences of, and have been always pretty much of the same humour in this respect. I am not like the person who, having sent off a letter to his mistress, who resided a hundred and twenty miles in the country, and disapproving, on second thoughts, of some expressions contained in it, took a post-chaise and four to follow and intercept it the next morning. At other times, I have sat and watched the decaying embers in a little back painting-room (just as the wintry day declined,) and brooded over the half-finished copy of a Rembrandt, or a landscape by Vangoyen, placing it where it might catch a dim gleam of light from the fire; while the Letter-Bell was the only sound that drew my thoughts to the world without, and reminded me that I had a task to perform in it. As to that landscape, methinks I see it now—

"The slow canal, the yellow-blossom'd vale,

The willow-tufted bank, the gliding sail."

There was a windmill, too, with a poor low clay-built cottage beside it:—how delighted I was when I had made the tremulous, undulating reflection in the water, and saw the dull canvass become a lucid mirror of the commonest features of nature! Certainly, painting gives one a strong interest in nature and humanity (it is not the dandy-school of morals or sentiment)—

"While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things."

Perhaps there is no part of a painter's life (if we must tell "the secrets of the prison-house") in which he has more enjoyment of himself and his art, than that in which after his work is over, and with furtive sidelong glances at what he has done, he is employed in washing his brushes and cleaning his pallet for the day. Afterwards, when he gets a servant in livery to do this for him, he may have other and more ostensible sources of satisfaction—greater [pg 188] splendour, wealth, or fame; but he will not be so wholly in his art, nor will his art have such a hold on him as when he was too poor to transfer its meanest drudgery to others—too humble to despise aught that had to do with the object of his glory and his pride, with that on which all his projects of ambition or pleasure were founded. "Entire affection scorneth nicer hands." When the professor is above this mechanical part of his business, it may have become a stalking-horse to other worldly schemes, but is no longer his hobby-horse and the delight of his inmost thoughts—

"His shame in crowds, his solitary pride!"

I used sometimes to hurry through this part of my occupation, while the Letter-Bell (which was my dinner-bell) summoned me to the fraternal board, where youth and hope

"Made good digestion wait on appetite

And health on both"—

or oftener I put it off till after dinner, that I might loiter longer and with more luxurious indolence over it, and connect it with the thoughts of my next day's labours.

The dustman's-bell, with its heavy, monotonous noise, and the brisk, lively tinkle of the muffin-bell, have something in them, but not much. They will bear dilating upon with the utmost license of inventive prose. All things are not alike conductors to the imagination. A learned Scotch professor found fault with an ingenious friend and arch-critic for cultivating a rookery on his grounds: the professor declared "he would as soon think of encouraging a froggery." This was barbarous as it was senseless. Strange that a country that has produced the Scotch Novels and Gertrude of Wyoming should want sentiment!

The postman's double-knock at the door the next morning is "more germain to the matter." How that knock often goes to the heart! We distinguish to a nicety the arrival of the Two-penny or the General Post. The summons of the latter is louder and heavier, as bringing news from a greater distance, and as, the longer it has been delayed, fraught with a deeper interest. We catch the sound of what is to be paid—eightpence, ninepence, a shilling—and our hopes generally rise with the postage. How we are provoked at the delay in getting change—at the servant who does not hear the door! Then if the postman passes, and we do not hear the expected knock, what a pang is there! It is like the silence of death—of hope! We think he does it on purpose, and enjoys all the misery of our suspense. I have sometimes walked out to see the Mail-Coach pass, by which I had sent a letter, or to meet it when I expected one. I never see a Mail-Coach, for this reason, but I look at it as the bearer of glad tidings—the messenger of fate. I have reason to say so.—The finest sight in the metropolis is that of the Mail-Coaches setting off from Piccadilly. The horses paw the ground, and are impatient to be gone, as if conscious of the precious burden they convey. There is a peculiar secresy and despatch, significant and full of meaning, in all the proceedings concerning them. Even the outside passengers have an erect and supercilious air, as if proof against the accidents of the journey. In fact, it seems indifferent whether they are to encounter the summer's heat or winter's cold, since they are borne through the air in a winged chariot. The Mail-Carts drive up; the transfer of packages is made; and, at a signal given, they start off, bearing the irrevocable scrolls that give wings to thought, and that bind or sever hearts for ever. How we hate the Putney and Brentford stages that draw up in a line after they are gone! Some persons think the sublimest object in nature is a ship launched on the bosom of the ocean; but give me, for my private satisfaction, the Mail-Coaches that pour down Piccadilly of an evening, tear up the pavement, and devour the way before them to the Land's End!

In Cowper's time, Mail-Coaches were hardly set up; but he has beautifully described the coming in of the Post-Boy:—

"Hark! 'tis the twanging horn o'er yonder bridge,

That with its wearisome but needful length

Bestrides the wintry flood, in which the moon

Sees her unwrinkled face reflected bright;—

He comes, the herald of a noisy world,

With spattered boots, strapped waist, and frozen locks;

News from all nations lumbering at his back.

True to his charge, the close packed load behind,

Yet careless what he brings, his one concern

Is to conduct it to the destined inn;

And having dropped the expected bag, pass on.

He whistles as he goes, light-hearted wretch!

Cold and yet cheerful; messenger of grief

Perhaps to thousands, and of joy to some;

To him indifferent whether grief or joy.

Houses in ashes and the fall of stocks.

Births, deaths, and marriages, epistles wet

With tears that trickled down the writer's cheeks

Fast as the periods from his fluent quill,

Or charged with amorous sighs of absent swains

Or nymphs responsive, equally affect

His horse and him, unconscious of them all."

And yet, notwithstanding this, and so many other passages that seem like the [pg 189] very marrow of our being, Lord Byron denies that Cowper was a poet!—The Mail-Coach is an improvement on the Post-Boy; but I fear it will hardly bear so poetical a description. The picturesque and dramatic do not keep pace with the useful and mechanical. The telegraphs that lately communicated the intelligence of the new revolution to all France within a few hours, are a wonderful contrivance; but they are less striking and appalling than the beacon fires (mentioned by Aeschylus,) which, lighted from hill-top to hill-top, announced the taking of Troy and the return of Agamemnon.

There is a certain valley in Languedoc, at no great distance from the palace of the Bishop of Mendes, where to this day the traveller is struck by some singular diversities of scenery. The valley itself is the most quiet and delightful that France can boast. A stream wanders through it, with just rapidity enough to keep its waters sweet and clear; and, on either side of this line of beauty, some gently swelling meadows extend—on one side to a chain of smooth green hills, and on the other, to the base of a mountain of almost inaccessible rocks. The river is bordered by willows and other shrubs, crowding to dip their branches in the transparent wave; and here and there in its neighbourhood, groves of walnut-trees stud the meadows, serving as a rendezvous of amusement for innumerable nightingales, which at the first dawn of summer assemble on the branches, and, as if in mockery of the poets, fill the evening air with their mirthful music.

The village of Rossignol (so named, probably, on account of the abundance of nightingales in the neighbourhood) was inhabited by very poor, but very happy people. It is true that, in common with other cultivators of the fickle earth, they had sometimes to mourn the overthrow of the husbandman's hopes; and that even their remote and lonely situation did not always protect them from the exactions of those whom birth, violence, or accident had made the lords of the domain. But in such cases, the villagers of Rossignol had a resource, limited, indeed, and attended by hardship, and even danger, but, to a certain extent, absolutely unfailing.

It must not be supposed, however, that, even in an Arcadia like this,

"The course of true love always did run smooth."

There was one young girl, called Julie, who was cruel enough to have depopulated a whole nation of lovers. She was the most beautiful creature, it is said, that ever skimmed the surface of this breathing world. Her light brown hair was illumined in the bends of the curls with gleams resembling those of auburn, and it was so long and luxuriant, that when, in the ardour of the chase, it became unbound, and floated in clouds around her, that seemed just touched on their golden summits by the sun, she looked more like a thing of air than of earth.

Nor was the illusion dissipated when, flinging away with her white arm the redundant tresses, her face flashed upon the gazer. There was nothing in it of that tinge of earth—for there is no word for the thought—which identifies the loveliest and happiest faces with mortality. There was no shade of care upon her dazzling brow—no touch of tender thought upon her lip—no flash, even of hope, in her radiant eyes. Her expression spoke neither of the past nor the future—neither of graves nor altars. She was a thing of mere physical life—a gay and glorious creature of the sun, and the wind, and the dews; who exchanged as carelessly and unconsciously as a flower, the sweet smell of her beauty for the bounties of nature, and pierced the ear of heaven with her mirthful songs, from nothing higher than the instinct of a bird.

It seemed as if what was absent in her mind had been added to her physical nature. She had the same excess of animal life which is observed in young children; but, unlike them, her muscular force was great enough to give it play. Her walk was like a bounding dance, and her common speech like a gay and sparkling song;—her laugh echoed from hill to hill, like the tone of some sweet, but wild and shrill instrument of music. She out-stripped the boldest of the youths in the chase; skimmed like some phantom shape along the edge of precipices approached even by the wild goat with fear; and looked round with careless joy, from pinnacles which interrupted the flight of the eagle through the air.

With such beauty, and such accomplishments, for the place and time, how [pg 190] many hearts might not Julie have broken! Julie did not break one. She was admired, loved, followed; and she fled, rending the air with her shrieks of musical laughter. Disconcerted, stunned, mortified, and alarmed, the wooer pursued his mistress only with his eyes, and blessed the saints that he had not gained such a phantom for a wife.

If in exterior magnificence St. Paul's surpasses all our other buildings, the interior, however, from many causes, is not so beautiful. You enter, and the naked loftiness of the walls, and the cold and barren stateliness of every thing around, would induce one to believe that an enemy—were such a thing possible in Britain—had taken London, and plundered the cathedral of all its national and religious paintings, together with a world of such rare works of curiosity or antiquity as find a sanctuary in the great churches of other countries. A few statues, some of them of moderate worth, are scattered about the recesses; and certain coloured drawings, done by the yard by Sir James Thornhill, may be distinguished far above; but all between is empty space, save where some tattered banners, pierced with many a shot, the memorials of our naval victories, hang dusty half-pillar high. This nakedness, however, is not so much the fault of the architect as of the clergy, who aught to have adorned this noble pile more largely by the hand of the painter and the sculptor. It was the wish of Wren to beautify the inside of the cupola with rich and durable Mosaic, and he intended to have sought the help of four of the most eminent artists in Italy for that purpose; but he was frustrated by the seven commissioners, who said the thing was so much of a novelty that it would not be liked, and also so expensive that it could not be paid for. The present work, too, over the communion table was intended only to serve till something more worthy could be prepared; and, to supply its place, Wren had modelled a magnificent altar, consisting of four pillars wreathed of the finest Greek marbles, supporting a hemispherical canopy, richly decorated with sculpture. But marble, such as he liked, could not readily be procured: dissensions arose, and the work remained in the models. The interposition of the Duke of York—the malevolence of the commissioners—the Puritanic, for I will not call them Protestant, prejudices of the clergy—and, I must add, the tastelessness of the nation at large, have all conspired to diminish the interior glory of St. Paul's, and render it less imposing on the mind than many a cathedral of less mark and reputation.—George III. saw what was wanting, and would have endeavoured to supply it; but all his efforts to overcome the ecclesiastical objections were unavailing. Let us hope that some of that truly good and English king's descendents may have better success.—Family Library, No. xix.

Richelieu in the meantime had reached his palace in the capital. Roman despot was never more courted nor more feared; but death was coming fast to close his triumphant career. A mortal malady wasted him: yet the cardinal abated nothing of his pride, nor of his vindictiveness. He exiled some of the king's personal and cherished officers; he insulted Anne of Austria, the queen: remained seated during a visit that she paid him, and threatened to separate her from her children. Even his guards no longer lowered their arms in the presence of the monarch. His demeanor to Louis XIII. was that of one potentate to another. In December of 1642 the malady of the cardinal became inveterate, and every hope of life was denied him. He summoned the king to his dying bed, recapitulated the great and successful acts of his administration, and recommended Mazarin as the person to continue its spirit, and to be his successor. Louis promised obsequiousness. Richelieu then received the last consolations of religion, and went through these pious and touching ceremonies with an apparently firm and undisturbed conscience. The man of blood knew no remorse. His acts had all been, he asserted, for his country's good; and the same unbending pride and unshaken confidence that had commanded the respect of men, seemed to accompany him into the presence of his Maker. He died like a hero of the Stoics, though clad in the trappings of a prince of the church. Most of those present were edified by his firmness; but one bishop, calling to mind the life, the arrogance, and the crimes of the minister, observed, that "the confidence of the dying Richelieu filled him with terror." The crime of having trodden out the last spark of his country's liberties, and of having converted its monarchic government into pure despotism, is that for which Richelieu is most generally [pg 191] condemned. But the state of anarchy which he removed was license, not liberty. The task of reconciling private independence with public peace, civil rights with the existence of justice,—and this without precedent or tradition, without that rooted stock on which freedom, in order to grow and bear fruit, must be grafted,—was a conception which, however familiar to our age, was utterly unknown, and impracticable to that of Richelieu. With the horrors of civil war fresh in the memory of all, the general desire was for tranquillity and peace, not liberty; to which, moreover, had it been contemplated, the first necessary step was that of humbling the aristocracy. It was impossible that constitutional freedom could grow out of the chaos of privileges, and anarchy, and organized rebellion, that the government had to contend with. In building up her social fabric France had in fact gone wrong, destroyed the old foundations, and rebuilt on others without solidity or system. To introduce order or add solidity to so ill-constructed a fabric, was impossible; Richelieu found it necessary to raze all at once to the ground, except the central donjon of despotism, which he left standing. Had Richelieu, with all his genius and sagacity, undertaken for liberty what he achieved for royalty, his age would have rejected or misunderstood him, as it did Bacon and Galileo. He might, indeed, as a man of letters, have consigned such a political dream to the volume of an Utopia, but from action or administration he would have been soon discarded as a dreamer. Liberty must come of the claim of the mass; of the general enlightenment, firmness, and probity. It is no great physical secret, which a single brain, finding, may announce and so establish: it is a moral truth, which, like a gem, hides its ray and its preciousness in obscurity, nor becomes refulgent till all around it is beaming with light.—Cabinet Cyclopaedia—History of France.

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.

SHAKSPEARE.

From what town in England does all the butter come in the London market?—Cowes.

Which is the closest town in Ireland, and is the best when drawn?—Cork.

A Dirty Member.—A member of a certain house was noticed the other night to be very dirty in his appearance, which a wit accounted for by saying he supposed the gentleman had been assisting the Chancellor of the Exchequer in taking the duty off coals!—From "the Age."

Was once restricted by an English law, wherein the prelates and nobility were confined to two courses at every meal, and two kinds of food in every course, except on great festivals: it also prohibited all who did not enjoy a free estate of £100. per annum, from wearing furs, skins, or silk, and the use of foreign cloth was confined to the royal family alone, to all others it was prohibited, 1337. In 1340, an edict was issued by Charles VI. of France, which says, "Let no one presume to treat with more than a soup and two dishes."

Formerly signified valet or servant as appears from Wickliffe's New Testament, kept in Westminster Library, and where we read—"Paul the knave of Jesus Christ." Hence the introduction of the knave in the pack of cards.

Steel may be made three hundred times dearer than standard gold, weight for weight; six steel wire pendulums, weight one grain, to the artists 7s. 6d. each, 2l. 5s.; one grain of gold only 2d.

Omai, the South Sea Islander, was once at a dinner in London, where stewed Morello cherries were offered to him. He instantly jumped up, and quitted the room. Several followed him; but he told them that he was no more accustomed to partake of human blood than they were. He continued rather sulky for some time, and it was only by the rest of the company partaking of them, that he would be convinced of his error, and induced to return to the table.

At White Hall Mill, in Derbyshire, a sheet of paper was manufactured last year, which measured 13,800 feet in length, four feet in width, and would cover an acre and a half of ground.

Among the ancient Saxons at Magdeburgh, the greatest beauties were at stated times deposited in charge of the magistrates, with a sum of money as the portion of each, to be publicly [pg 192] fought for; and fell to the lot of those who were famous at tilting.

When London did not extend so far as Knightsbridge, George II. as he was one morning riding, met an old soldier who had served under him at the battle of Dettingen; the king accosted him, and found that he made his living by selling apples in a small hut. "What can I do for you?" said the king.—"Please your majesty to give me a grant of the bit of ground my hut stands on, and I shall be happy."—"Be happy," said the king, and ordered him his request. Years rolled on, the appleman died, and left a son, who from dint of industry became a respectable attorney. The then chancellor gave lease of the ground to a nobleman, as the apple-stall had fallen to the ground, where the old apple man and woman laid also. It being conceived the ground had fallen to the crown, a stately mansion was soon raised, when the young attorney put in claims; a small sum was offered as a compromise and refused; finally, the sum of four hundred and fifty pounds per annum, ground rent, was settled upon.

Comets, doubtless, answer some wise and good purpose in the creation; so do women. Comets are incomprehensible, beautiful, and eccentric; so are women. Comets shine with peculiar splendour, but at night appear most brilliant; so do women. * * * * Comets confound the most learned, when they attempt to ascertain their nature; so do women. Comets equally excite the admiration of the philosopher, and of the clod of the valley; so do women. Comets and women, therefore are closely analogous: but the nature of each being inscrutable, all that remains for us to do is, to view with admiration the one, and almost to adoration love the other.

Dr. John Thomas, Bishop of Lincoln, was married four times. The motto, or posy, on the wedding ring, at his fourth marriage was—

"If I survive

I'll make them five."

Casimir the second, King of Poland, when Prince of Sandomir, won at play all the money of one of his nobility, the loser, who, incensed at his ill-fortune, struck the prince a blow on the ear. The offender instantly fled; but being pursued and taken, he was condemned to lose his head: Casimir interposed. "I am not surprised," said the prince, "that, not having it in his power to revenge himself on Fortune, he should attack her favourite." He revoked the sentence, returned the nobleman his money, and declared that he alone was faulty, as he had encouraged, by his example, a pernicious practice, that might terminate in the ruin, of his people.

So falls that stately Cedar; while it stood

That was the onely glory of the wood;

Great Charles, thou earthly God, celestial man,

Whose life, like others, though it were a span;

Yet in that span, was comprehended more

Than earth hath waters, or the ocean shore;

Thy heavenly virtues, angels should rehearse,

It is a theam too high for humane verse:

Hee that would know thee right, then let him look

Upon thy rare-incomparable book,

And read it or'e; which if he do,

Hee'l find thee King, and Priest, and Prophet too;

And sadly see our losse, and though in vain,

With fruitlesse wishes, call thee back again.

Nor shall oblivion sit upon thy herse,

Though there were neither monument, nor verse.

Thy suff'rings and thy death let no man name;

It was thy Glorie, but the kingdom's shame.

Footnote 2: (return)Chairman of the Committee of Chemistry, in the Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. This valuable article is extracted from the 47th Vol. of its Transactions.

Footnote 3: (return)Arnold was a General in the American service, and had distinguished himself on former occasions like a brave soldier, an experienced commander, and a sincere citizen; but, like another Judas Iscariot, he afterwards thought fit to turn traitor. He deserted to the English as soon as the news reached him of the apprehension of André (because he knew then that his name and the plans arranged previously between him and the British General would be exposed and frustrated,) with the expectation of receiving a few pieces of silver for betraying his country. Whatever was his recompense in this way I know not, but I am certain he was despised as long as he lived, and his memory will for ever be pointed at as contemptible and degrading by the people of both nations.

Footnote 4: (return)The remains of Major André were lately, by a special request from the British government to the United States, brought to England, and placed among the worthies of Westminster Abbey.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; G.G. BENNIS, 55, Rue Neuve, St. Augustin, Paris; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.