Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 541, April 7, 1832

Author: Various

Release date: June 1, 2004 [eBook #12551]

Most recently updated: December 15, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Allen Siddle and PG Distributed Proofreaders

| Vol. XIX. No. 541.] | SATURDAY, APRIL 7, 1832. | [PRICE 2d. |

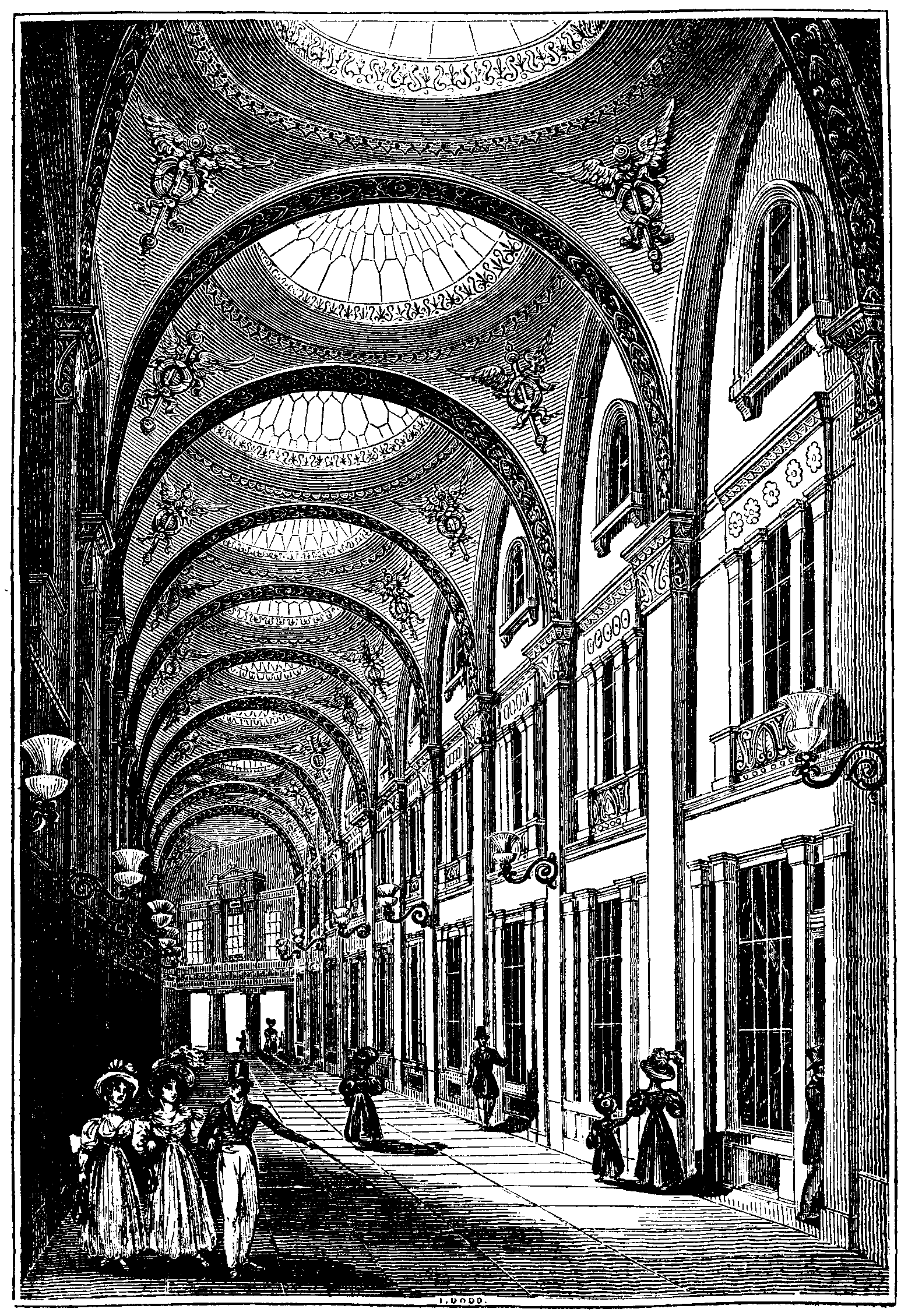

In No. 514 of The Mirror we explained the situation of the Lowther Arcade. We may here observe that this covered way or arcade intersects the insulated triangle of buildings lately completed in the Strand, the principal façade of which is designated West Strand.

The Engraving represents the interior of the Arcade, similar in its use to the Burlington Arcade, and, although wider and more lofty, including three stories in height, it is not so long. The passage forms an acute angle with the Strand, running to the back of St. Martin's Church, and is divided by large pilasters into a succession of compartments; the pilasters are joined by an arch; and the compartments are domed over, and lighted in the centre by large domical lights, which illuminate the whole passage in a perfect manner. "All the shop-fronts are decorated in a similar manner, and the whole has been designed and executed with great care by the builder, Mr. Herbert. The shops on the exterior are designed to have the appearance of one great whole. The style of architecture is Grecian, and the order employed Corinthian: the angles are finished in a novel manner, with double circular buildings, having the roof domed in brick, with an ornament as a finish to the top of the dome. The effect of the whole would be agreeable if it had the appearance of a solid basement to stand upon; but as tradesmen find it necessary to have as much open space as possible to exhibit their goods, the mass of architecture above must appear to be supported by the window-frames of the shops, although in reality they are based upon small iron columns of four and six inches diameter, which are scarcely seen, and which offer the slightest possible impediment to the exhibition of goods."

We may add that the Arcade at night is lit with gas within elegant vase-shaped shades of ground glass, branching from each side. The ornaments of the domes, especially that of the Caduceus, are introduced with good effect.

We take the introduction of this and similar passages in the British metropolis to have been originally from the French capital. Thus, in Paris are the Passage des Panoramas; the Passage Delorme; the Passage d'Artois; the Passage Feydeau; the Passage de Caire; and the Passage Montesquieu. A more grandiloquent name applied by the French to some of their passages is galerie: we remember the Galerie Vivienne as one of the most splendid specimens, with its marchands of artificial luxuries. The Galerie Vero Dodat, (we think shorter than the Lowther Arcade,) is in the extreme of shop-front magnificence: the floor is of alternate squares of black and white marble, and the fronts are of plate-glass with highly-polished brass frames, and we doubt whether that common material, wood, is to be seen in the doors. This Galerie is named after its proprietor, M. Vero Dodat, an opulent charcutier, (a pork-butcher) in the neighbouring street; but we are unable to inform the reader by how many horse power his sausage-chopping machine is worked.

In No. 533 of The Mirror is a Cut of the Cascade at Virginia Water (which by the way is a very correct one, with the keeper's lodge in the distance) which you state was the late King's own planing; but such was not the case, as it was built in the reign of George the Third; the late king merely added improvements about it, one of which was the building of a rude bridge a little below the cascade, of stones similar to the fall: this bridge connects a favourite drive down to the nursery.

Brighton.

E.E.

It may be entertaining to many of your readers now that emigration occupies the thoughts of so many, to sketch a short account of the method chiefly employed in Canada, in capturing fish, which to very many settlers is an important adjunct to their domestic economy. Those living on the borders of the numerous lakes and rivers of Canada, which are invariably stored with fine fish, are provided with either a light boat, log, or what is by far the best, a bark canoe; a barbed fishing spear, with light tapering shaft, about twelve or sixteen feet long, and an iron basket for holding pine knots, and capable of being suspended at the head of the boat when fired. In the calm evenings after dusk, many of these lights are seen stealing out from the woody bays in the lakes, towards the best fishing grounds, and two or three canoes together, with the reflection of the red light from the clear green water on the bronzed faces of either the native Indian, or the almost as wild Backwoodsman, compose an extraordinary scene: the silence of the night is undisturbed, save by the [pg 211] gurgling noise of the paddles, as guided by the point of the spear; the canoe whirls on its axis with an almost dizzing velocity, or the sudden dash of the spear, followed by the struggles of the transfixed fish, or perhaps the characteristic "Eh," from the Indian steersman. In this manner, sometimes fifty or sixty fish of three or four pounds are speared in the course of a night, consisting of black bass, white fish, and sometimes a noble maskimongi. A little practice soon enables the young settler to take an active part in this pursuit. The light seems to attract the fish, as round it they thickly congregate. But few fish are caught in this country by the fly: at some seasons, however, the black bass will rise to it. A CANADIAN.

No. 538, of The Mirror, contains a very interesting memoir on the subject of the Cross-bow, but I do not find that the mode of bending the steel bow has been described; which from its great strength it is evident could not be accomplished without the assistance of some mechanical power. This in the more modern bows is attained by the application of a piece of steel, which lies along the front of the stem, and is moved forward on a pivot until the string is caught by a hook, and a lever is thus obtained, by means of which the bow is drawn to its proper extent. It seems to me that this is the description of bow of which your correspondent has furnished a drawing. Another mode, and which appears to have been applied to the ancient bows, was by a sort of two-handed windlass, with ropes and pulleys, called a "moulinet," which was temporarily attached to the butt-end of the Cross-bow; of this a drawing is given in the illustrations of Froissart's Chronicles, particularly in that one descriptive of the Siege of Aubenton; in which two bowmen are shown, one in the act of winding up the bow, and the other taking his aim, the moulinet, &c. lying at his feet. Of this latter description, there are two specimens preserved in the Tower of London, both of about the period of our Henry the Sixth.

C.P.C.

Upon thy happy flight to heaven, again, sweet

bird, thou art;

The morning beam is on thy wings, its influence

in thy heart;

Like matin hymns blest spirits sing in yonder

happy sky,

Break on the ear, the small, sweet notes of thy

wild melody.

Cold winter winds are far away, the cruel snows

have past;

And spring's sweet skies, and blushing flowers

shine o'er the world at last;

Where the young corn springs fresh, and green,

sweet flowerets gather'd he,

And form around thy lowly nest a shelter sweet

for thee.

Is it not this which wakes thy song, with thoughts of

summer hours,

When warmer hues shall clothe the skies, and

darker shades the bowers;

Has nature to thy throbbing heart such glowing

feelings given,

That thou canst feel the beautiful, of this bright

earth and heaven.

If so, how blest must be thy lot, from azure

skies to gaze,

When the fresh morn is in the heavens, or

mid-day splendours blaze;

Or when the sunset's canopy of golden light is

spread,

And thou unseen, enshrin'd in light, art singing

overhead.

Oh then thy happy song comes down upon the

glowing breast,

Soft as rich sunlight, on the flowers, comes from

the golden west:

And fain the heart would soar with thee, enshrin'd

in thought as sweet,

As the rich tones, which from thy heart, thou

dost in song repeat.

Oh there is not on earth a breast, but turns

with joy to thee.

From the cold wither'd years of age, to smiling

infancy.

Thou claimest smiles from ev'ry lip, and praise

from ev'ry tongue;

Such sympathy each happy heart finds in thy

joyous song.

Dorking.

SYLVA.

The following curious notice of the Acherontia Atropos, or Death's-head Moth, we extract from "The Journal of a Naturalist:"—"The yellow and brown-tailed moths," he observes, "the death-watch, our snails, and many other insects, have all been the subjects of man's fears, but the dread excited in England by the appearance, noises, or increase of insects, are petty apprehensions compared with the horror that the presence of this Acherontia occasions to some of the more fanciful and superstitious natives of northern Europe, [pg 212] maintainers of the wildest conceptions. A letter is now before me from a correspondent in German Poland, where this insect is a common creature, and so abounded in 1824 that my informant collected fifty of them in a potato field of his village, where they call them the 'death's-head phantom,' the 'wandering death-bird,' &c. The markings on the back represent to their fertile imaginations the head of a perfect skeleton, with the limb bones crossed beneath; its cry becomes the voice of anguish, the moaning of a child, the signal of grief; it is regarded, not as the creation of a benevolent being, but as the device of evil spirits—spirits, enemies to man, conceived and fabricated in the dark; and the very shining of its eyes is supposed to represent the fiery element whence it is thought to have proceeded. Flying into their apartments in an evening, it at times extinguishes the light, foretelling war, pestilence, famine, and death to man and beast. * * * This insect has been thought to be peculiarly gifted in having a voice and squeaking like a mouse when handled or disturbed; but, in truth, no insect that we know of has the requisite organs to produce a genuine voice; they emit sounds by other means, probably all external."

The Icelanders believe Seals to be the offspring of Pharaoh and his host; who, they assert, were changed into these animals when overwhelmed in the Red Sea. The Grampus, Porpoise, and Dolphin, have each from the earliest ages been the subject of numerous superstitions and fables, particularly the latter, which was believed to have a great attachment to the human race, and to succour them in accidents by sea; it is a perfectly straight fish, yet even painters have promulgated a falsity respecting it, by representing it from the curved form in which it appears above water, bent like the letter S reversed. "The inhabitants of Pesquare," says Dr. Belon, "and of the borders of Lake Gourd are firmly persuaded that the Carp of those lakes are nourished with pure gold; and a great portion of the people in the Lyonnois are fully satisfied that the fish called humble and ernblons eat no other food than gold. There is not a peasant in the environs of the Lake of Bourgil who will not maintain that the Laurets, a fish sold daily in Lyons, feed on pure gold alone. The same is the belief of the people of the Lake Paladron in Savoy, and of those near Lodi. But," adds the Doctor, "having carefully examined the stomachs of these several fishes, I have found that they lived on other substances, and that from the anatomy of the stomach it is impossible that they should be able to digest gold." This fable, therefore, with that of the Chameleon living on air only, and some others which we shall have occasion to mention, may be regarded amongst those exploded by science.

The fable of the Kraken has been referred to imperfect and exaggerated accounts of monstrous Polypi infesting the northern seas; how far may not the Cuttle-fish have given rise to this fiction? In hot countries (our readers will remember that in a late paper, Mirror, vol. xvii. pp. 282-299, we directed their attention to the similarity of superstitions in every country of the world, hence infering a common, and most probably oriental origin for all)—in hot countries cuttle-fish are found of gigantic dimensions; the Indians affirm that some have been seen two fathoms broad over their centre; and each arm (for this kind is the eight-armed cuttle-fish) nine fathoms long!!! Lest these animals should fling their arms over the Indians' light canoes, and draw them and their owners into the sea, they fail not to be provided with an axe to chop them off.

The ancients believed that the oil of the Grayling obliterated freckles and small-pox marks. The adhesive qualities of the Remora, or Sucking-fish, and its habit of darting against and fixing itself to the side of a vessel, caused the ancients to believe that the possessors of it had the power of arresting the progress of a ship in full sail.

Some Catholics, in consequence of the John Doree having a dark spot, like a finger-mark, on each side of the head, believe this to have been the fish, and not the Haddock, from which the Apostle Peter took the tribute-money, by order of our Saviour. The modern Greeks denominate it "the fish of St. Christopher," from a legend which relates that it was trodden on by that saint, when he bore his divine burden across an arm of the sea. Some species of Echini, fossilized, and seen frequently in Norfolk, are termed by the ignorant peasantry, and considered, Fairy Loaves, to take which, when found, is highly unlucky.

The Amphisbaena, from its faculty of moving backwards or forwards at pleasure, has been thought to have a head at either extremity of its reptile body, but close inspection proves this opinion false. The fascinating power of the Rattlesnake, of which so many stories have in times past been related, and which was asserted to exist in its glittering [pg 213] eyes, has been of late years resolved into that extreme nervous terror of its victim (at sight of so certain a foe) which deprives it of the power of motion, and causes it to fall, an unresisting prey, into the reptile's jaws. We may here pause to observe, en passant, that the antipathy which people of all ages and nations have felt against every reptile of the serpent tribe, from the harmless worm to the hosts of deadly "dragons" which infest the torrid zone, and the popular opinion that all are venomous, often in spite of experience, seems to be not so much superstition, as a terror of the species, implanted, since the fall, in our bosoms, by the same Divine Being who at that period pronounced the serpent to be the most accursed beast of the field.

Nothing if not political appears to be the order of the new magazine and other literary enterprises of the present day. Is this good policy in itself? it may be so from the vivifying aid it lends to the springs of imaginative writing. We have therefore no right to complain of the leaven of Mr. Tait's Magazine: it is anything but dull: e.g. the life and jauntiness of the following paper is very pleasant, shrewd, and clever:

The Martinet.

The "Martinet" is the name of a genus, not of a species; the title of a race variously feathered, but having specific qualities in common. There is your military martinet, your clerical martinet, your legal martinet, and the martinet of common life, ("Gallicrista fastidiosa communis," Linnaeus would class him,) who is to the others what the house-sparrow is to the rest of his tribe. It is with him alone we have to do. The "martinet" is a person who is all his life violently busied in endeavouring to be a perfect gentleman, and who almost succeeds. He misses the point by over-stepping it. He is like one of those greyhounds which outrun the hare fleetly enough, but cannot "take" her when they have done so. They have a little too much speed, and a little too little tact. The martinet is always bent upon thinking, saying, doing, and having, every thing after a nicer fashion than other people, until his nicety runs into downright mannerism; all his ideas become "clipped taffeta," and all his eggs are known to have "two yolks." He rarely comes of age or is thoroughly ripe till near forty, before which he may be a little of the precise fop, and after which he changes to the somewhat foppish precisian, which is the best definition of him. He would be an excellent member of society were he not a little too nice for its every-day work, which, to speak a truth in metaphor, will not always admit of white gloves. He is remarkably consistent in all his proceedings, however, and the outward man is a perfect and complete type of the inward, and vice versa. His soul is never out of pumps and silk stockings, and picks its way amidst the little mental puddles and cross-roads of this world with a chariness of step, which is at once edifying and amusing. Of inward show he is not less "elaborate" than of outward; and, though a descendant of Eve, takes equal care of the clothing of both mind and body.

Were his tailor to be abandoned enough to attempt to palm upon him a coat of the very best Yorkshire, instead of the very best Wiltshire broad-cloth, (an enormity of which—horresco referens—he was once very near being the victim,) the one would be sure to lose, if discovered, the best of his customers, and the other the best of a month's sleep. If he wears a wig, his expenditure with his peruquier is never less than five-and-twenty guineas a-year. His cigars, though he smokes little, cost him nearly as much. His hat is water-proof; his stop-watch and repeater are of a scapement that never varies more than six seconds in the twelve months from the time-piece at the Observatory at Greenwich, where he has a friend, who is so good as sometimes to compare notes with him. By the advice of his boot-maker—who, by the way, has some knowledge of the length of his foot—he never puts on a new pair until they are at least a year old; and he parted with his last footboy because he one day discovered a perceptible difference between the polish of the right and left foot. In winter, he wears and recommends cork soles. His toilet is no sinecure; and on the table are always to be found, besides his dressing-box, which contains an assortment of combs, scissors, tweezers, pomades, and essences, not easily equalled, a bottle of "Eau de Cologne, veritable," a Packwood and Criterion strop; a case of gold-mounted razors, (the best in England,) which he bought, nearly thirty years ago, of the successor of "Warren," in the Strand, and a silvered shaving-pot, upon a principle of his own, redolent of Rigges' [pg 214] "patent violet-scented soap." His net-silk purse is ringed with gold at one end, and with silver at the other; and although not much of a snuff-taker, he always carries a box, on the lid of which smiles the portrait of the once celebrated and beautiful, though now somewhat forgotten, Duchess of D——, or the equally resplendent Lady Emily M——.

His table is of the same finish with his wardrobe. If he sat down to dinner, even when alone, in boots, that visitation which Quin ascribed to the prevalent neglect of "pudding on a Sunday"—an earthquake might be expected to follow. His spoons and silver forks are marked with his crest; and he omits no opportunity to inform his friends, that the right of the family to the arms was proved at Herald's College by his great uncle John. He has receipts for mulligatawny and oyster soups, not to be equalled; and another for currie-powder, which a friend of his obtained, as the greatest of favours, from Sir Stamford Raffles, and which, though bound in honour not to make known, he means to leave to his son by will, under certain injunctions. His cookery of a "French rabbit," provided the claret be first-rate, is superb; and on very particular occasions, he condescends to know how to concoct a bowl of punch, especially champagne punch, for the which he has a formula in rhyme, the poetry of which never, as is its happy case, losing sight of correctness and common-sense, comes, as well as its subject matter, home to "his business and his bosom." His "caviar" is, through the kindness of a commercial friend, imported from the hand of the very Russian cuisinier, who prepares it (unctuous relish!) for the table of the Emperor himself. His cheese is Stilton or Parmesan.

Like "Mrs. Diana Scapes," he is also "curious in his liquors," and, in despite of Beau Brummell, patronizes "malt," as far as to take one glass of excellent "college ale,"—which he gets through his friend Dr. Dusty of All Souls—between pastry and Parmesan. After cheese, he can relish one, and only one, glass of port—all the better if of the "Comet vintage," or of some vintage ten years anterior to that. His drink, however, is claret, old hock, Madeira, and latterly, since it has become a sort of fashion, old sherry. In these he is a connoisseur not to be sneezed at; and if asked his opinion, makes it a rule never to give it upon the first glass, invariably observing, that "if he would he couldn't, and if he could he wouldn't!" He produces anchovy toast as an indispensable in a long evening, after dinner, and to it he recommends a liqueur-glass of cherry-brandy, which he believes is of that incomparable recipe, of which the late King was so fond. If he be a bachelor, he has, in his dining-room, a cellaret, in which repose this, and other similar liquid rarities, and beneath his sideboard stands a machine, for which he paid twelve guineas, for producing ice extempore.

His literary tastes bear a certain resemblance to, and have a certain analogy with, his gustatory—proving the truth of that intimate connexion between the stomach and the head, upon which physiologists are so delighted to dwell. In poetry the heresies and escapades of Lord Byron are too much for him, although as a Peer and a gentleman he always speaks well and deferentially of him. Shelley he can make nothing of, and therefore says, which is the strict truth in one sense at least, that he has never read him. He praises Campbell, Crabbe, and Rogers, and shakes his head at Tom Moore; but Pope is his especial favourite; and if anything in verse has his heart, it is the "Rape of the Lock." Peter Pindar he partly dislikes, but Anstey, the "Bath Guide," is high in his estimation; and with him "Gray's Odes" stand far above those of Collins'. Of the "Elegy in a Country Church" he thinks, as he says, "like the rest of the world." "Shenstone's Pastorals" he has read. Burns he praises, but in his heart thinks him a "wonderful clown," and shrugs his shoulders at his extreme popularity. He says as little about Shakespeare as he can, and has by heart some half dozen lines of Milton, which is all he really knows of him. In the drama he inclines to the "unities;" and of the English Theatre "Sheridan's School for Scandal," and Otway's "Venice Preserved," or Rowe's "Fair Penitent," are what he best likes in his heart. John Kemble is his favourite actor—Kean he thinks somewhat vulgar. In prose he thinks Dr. Johnson the greatest man that ever existed, and next to him he places Addison and Burke. His historian is Hume; and for morals and metaphysics he goes to Paley and Dr. Reid, or Dugald Stewart, and is well content. For the satires of Swift he has no relish. They discompose his ideas; and he of all things detests to have his head set a spinning like a tetotum, either by a book or by anything else. Bishop Berkeley once did this [pg 215] for him to such a tune, that he showed a visible uneasiness at the mention of the book ever after. In Tristram Shandy, however, he has a sort of suppressed delight, which he hardly likes to acknowledge, the magnet of attraction being, though he knows it not, in the characters of Uncle Toby, Corporal Trim, and the Widow Wadman. His religious reading is confined to "Blair's Sermons," and the "Whole Duty of Man," in which he always keeps a little slip of double gilt-edged paper as a marker, without reflecting that it is a sort of proof that he has never got through either. His Pocket Bible always lies upon his toilet table. He knows a little of Mathematics in general, a little of Algebra, and a little of Fluxions, which is principally to be discovered from his having Emmerson, Simpson, and Bonnycastle's works in his library. In classical learning he confesses to having "forgotten" a good deal of Greek; but sports a Latin phrase upon occasion, and is something of a critic in languages. He prefers Virgil to Homer, and Horace to Pindar, and can, upon occasion, enter into a dissertation on the precise meaning of a "Simplex munditiis." He also delights in a pun, and most especially in a Latin one; and when applied to for payment of paving-rate, never fails to reply "Paveant illi, non paveam ego!" which, though peradventure repeated for the twentieth time, still serves to sweeten the adieu between his purse and its contents. He is also an amateur in etymologies and derivatives, and is sorry that the learned Selden's solution of the origin of the term "gentleman" seems to include in it something not altogether complimentary to religion. This is his only objection to it. He speaks French; and his accent is, he flatters himself, an approximation to the veritable Parisian. Modern novels he does not read, but has read "Waverley" and "Pelham."

His library is not large, but select; and as he does not sit in it excepting very occasionally, the fire grate is a movable one, and can be turned at will from parlour to library and vice versa,—a whim of his old acquaintance Dr. Trifle of Oxford. In it are his library table and stuffed chair; a bust of Pitt and another of Cicero; a patent inkstand and silver pen; an atlas, and maps upon rollers; a crimson screen, an improved "Secretaire;" a barometer and a thermometer. Upon the shelves may be found almost for certain Boswell's Johnson; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Peptic Precepts and Cook's Oracle; the Miseries of Human Life; Prideaux' Connexion of the Old and New Testament; Dr. Pearson's Culina Famulatrix Medecinae; Soame Jenyn's Essays; the Farrier's Guide; Selden's Table-talk; Archbishop Tillotson's Sermons; Henderson on Wines; Boscawen's Horace; Croker's Battles of Talavera and Busaco; Dictionary of Quotations; Lord Londonderry's Peninsular Campaigns; the Art of Shaving, with directions for the management of the Razor; Todd's Johnson's Dictionary; Peacham's Complete Gentleman; Harris' Hermes; Roget on the Teeth; Memoirs of Pitt; Jokeby, a Burlesque on Rokeby; English Proverbs; Paley's Moral Philosophy; Chesterfield's Letters; Buchan's Domestic Medicine; Debrett's Peerage; Colonel Thornton's Sporting Tour; Court Kalendar; the Oracle, or Three Hundred Questions explained and answered; Gordon's Tacitus an Elzevir Virgil; Epistolae obscurorum virorum; Martial's Epigrams; Tully's Offices; and Henry's Family Bible.

His general character for nicety is excellent, both in a moral and religious point of view: and he holds himself to have done a questionable thing in looking into a number of Harriette Wilson, in which a gay quondam friend of his figured. When he marries, the ceremony is performed by the Honourable and very Reverend the Dean of some place, to whom he claims a distant relationship. He takes his wine in moderation; never bets, nor plays above guinea points, and always at whist. He goes to church regularly; his pew is a square one, with green curtains. He dines upon fish on Good Friday, and declines visiting during Passion week in mixed parties. If he ever had any peccadilloes of any kind, they are buried in a cloud as snug as that which shrouded the pious Eneas when he paid his first visit to Queen Dido.

He dies, aged fifty-seven, of a pleuritic attack, complicated with angina pectoris; and having left fifty pounds to each of the principal charitable institutions of his neighbourhood, and fifty pounds to the churchwardens of his parish, to be distributed amongst the poor professing the religion of the Church of England, he is buried in his "family vault," and his last wish fulfilled,—that is to say, his epitaph is composed in Latin, and the inscription put up under the especial care and inspection of his friend Dr. Dusty of Oxford. Requiescat.

In the New Monthly Magazine, just published is a powerful poem—the Splendid Village, by the author of "Corn-law Rhymes." from which we extract the following passage:

I sought the churchyard where the lifeless lie,

And envied them, they rest so peacefully.

"No wretch comes here, at dead of night." I said,

"To drag the weary from his hard-earn'd bed;

No schoolboys here with mournful relics play,

And kick the 'dome of thought' o'er common clay;

No city cur snarls here o'er dead men's bones;

No sordid fiend removes memorial stones.

The dead have here what to the dead belongs,

Though legislation makes not laws, but wrongs."

I sought a letter'd stone, on which my tears

Had fall'n like thunder-rain, in other years,

My mother's grave I sought, in my despair,

But found it not! our grave-stone was not there!

No we were fallen men, mere workhouse slaves,

And how could fallen men have names or graves?

I thought of sorrow in the wilderness,

And death in solitude, and pitiless

Interment in the tiger's hideous maw:

I pray'd, and, praying, turn'd from all I saw;

My prayers were curses! But the sexton came;

How my heart yearn'd to name my Hannah's name!

White was his hair, for full of days was he,

And walk'd o'er tombstones, like their history.

With well feign'd carelessness I rais'd a spade,

Left near a grave, which seem'd but newly made,

And ask'd who slept below? "You knew him well,"

The old man answer'd, "Sir, his name was Bell.

He had a sister—she, alas! is gone,

Body and soul. Sir! for she married one

Unworthy of her. Many a corpse he took

From this churchyard." And then his head he shook,

And utter'd—whispering low, as if in fear

That the old stones and senseless dead would hear—

A word, a verb, a noun, too widely famed,

Which makes me blush to hear my country named.

That word he utter'd, gazing on my face,

As if he loath'd my thoughts, then paus'd a space.

"Sir," he resumed, "a sad death Hannah died;

Her husband—kill'd her, or his own son lied.

Vain is your voyage o'er the briny wave,

If here you seek her grave—she had no grave!

The terror-stricken murderer fled before

His crime was known, and ne'er was heard of more.

The poor boy died, sir! uttering fearful cries

In his last dreams, and with his glaring eyes,

And troubled hands, seem'd acting, as it were,

His mother's fate. Yes, Sir, his grave is there."

Our readers are already in possession of the outline of this memorable journey; though nothing but an attentive perusal of the Discoverers' Narrative can afford them the remotest idea of the dangers they encountered in their progress. To gratify this curiosity, Mr. Murray has considerately enough, printed their Journal in three volumes of the Family Library, and to say that they are, in interest, equal if not superior to any of the Series would be praise inadequate to their merits. The simple, unvarnished style of the Narrative is just suitable for a family fireside. We intend to quote a few scenes: at present

An African Horse-Race,

at Kiáma, in the kingdom of Borgoo from the first volume.

"In the afternoon, all the inhabitants of the town, and many from the little villages in its neighbourhood, assembled to witness the horse-racing, which takes place always on the anniversary of the 'Bebun Sàlah,' and to which every one had been looking forward with impatience. Previous to its commencement, the king, with his principal attendants, rode slowly round the town, more for the purpose of receiving the admiration and plaudits of his people than to observe where distress more particularly prevailed, which was his avowed intention. A hint from the chief induced us to attend the course with our pistols, to salute him as he rode by; and as we felt a strong inclination to witness the amusements of the day, we were there rather sooner than was necessary, which afforded us, however, a fairer opportunity of observing the various groups of people which were flocking to the scene of amusement.

"The race-course was bounded on the north by low granite hills; on the south by a forest; and on the east and west by tall shady trees, among which were habitations of the people. Under the shadow of these magnificent trees the spectators were assembled, and testified their happiness by their noisy mirth and animated gestures. When we arrived, the king had not made his appearance on the course; but his absence was fully compensated by the pleasure we derived from watching the anxious and animated countenances of the multitude, and in passing our opinions on the taste of the women in the choice and adjustment of their fanciful and many-coloured dresses. The chief's wives and younger children sat near us in a group by themselves; and were distinguished from their companions by their superior dress. Manchester cloths of inferior quality, but of the most showy patterns, and dresses made of common English bed-furniture, were fastened round the waist of several sooty maidens, who, for the sake of fluttering a short hour in the [pg 217] gaze of their countrymen, had sacrificed in clothes the earnings of a twelve-month's labour. All the women had ornamented their necks with strings of beads, and their wrists with bracelets of various patterns, some made of glass beads, some of brass, others of copper; and some again of a mixture of both metals: their ancles also were adorned with different sorts of rings, of neat workmanship.

"The distant sound of drums gave notice of the king's approach, and every eye was immediately directed to the quarter from whence he was expected. The cavalcade shortly appeared, and four horsemen first drew up in front of the chief's house, which was near the centre of the course, and close to the spot where his wives and children and ourselves were sitting. Several men bearing on their heads an immense quantity of arrows in huge quivers of leopard's skin came next, followed by two persons who, by their extraordinary antics and gestures, we concluded to be buffoons. These two last were employed in throwing sticks into the air as they went on, and adroitly catching them in falling, besides performing many whimsical and ridiculous feats. Behind these, and immediately preceding the king, a group of little boys, nearly naked came dancing merrily along, flourishing cows' tails over their heads in all directions. The king rode onwards, followed by a number of fine-looking men, on handsome steeds; and the motley cavalcade all drew up in front of his house, where they awaited his further orders without dismounting. This we thought was the proper time to give the first salute, so we accordingly fired three rounds; and our example was immediately followed by two soldiers, with muskets which were made at least a century and a half ago.

"Preparations in the mean time had been going on for the race, and the horses with their riders made their appearance. The men were dressed in caps and loose tobes and trousers of every colour; boots of red morocco leather, and turbans of white and blue cotton. The horses were gaily caparisoned; strings of little brass bells covered their heads; their breasts were ornamented with bright red cloth and tassels of silk and cotton; a large quilted pad of neat embroidered patchwork was placed under the saddle of each; and little charms, enclosed in red and yellow cloth, were attached to the bridle with bits of tinsel. The Arab saddle and stirrup were in common use; and the whole group presented an imposing appearance.

"The signal for starting was made, and the impatient animals sprung forward and set off at a full gallop. The riders brandished their spears, the little boys flourished their cows' tails, the buffoons performed their antics, muskets were discharged, and the chief himself, mounted on the finest horse on the ground, watched the progress of the race, while tears of delight were starting from his eyes. The sun shone gloriously on the tobes of green, white, yellow, blue, and crimson, as they fluttered in the breeze; and with the fanciful caps, the glittering spears, the jingling of the horses' bells, the animated looks and warlike bearing of their riders, presented one of the most extraordinary and pleasing sights that we have ever witnessed. The race was well contested, and terminated only by the horses being fatigued and out of breath; but though every one was emulous to outstrip his companion, honour and fame were the only reward of the competitors.

"A few naked boys, on ponies without saddles, then rode over the course, after which the second and last heat commenced. This was not by any means so good as the first, owing to the greater anxiety which the horsemen evinced to display their skill in the use of the spear and the management of their animals. The king maintained his seat on horseback during these amusements, without even once dismounting to converse with his wives and children who were sitting on the ground on each side of him. His dress was showy rather than rich, consisting of a red cap, enveloped in the large folds of a white muslin turban; two under tobes of blue and scarlet cloth, and an outer one of white muslin; red trousers, and boots of scarlet and yellow leather. His horse seemed distressed by the weight of his rider, and the various ornaments and trappings with which his head, breast, and body, were bedecked. The chief's eldest and youngest sons were near his women and other children, mounted on two noble looking horses. The eldest of these youths was about eleven years of age. The youngest being not more than three, was held on the back of his animal by a male attendant, as he was unable to sit upright in the saddle without this assistance. The child's dress was ill suited to his age. He wore on his head a tight cap of Manchester cotton, but it overhung the upper part of his face, and together with its ends, which flapped over each cheek, [pg 218] hid nearly the whole of his countenance from view; his tobe and trousers were made exactly in the same fashion as those of a man, and two large belts of blue cotton, which crossed each other, confined the tobe to his body. The little legs of the child were swallowed up in clumsy yellow boots, big enough for his father; and though he was rather pretty, his whimsical dress gave him altogether so odd an appearance, that he might have been taken for anything but what he really was. A few of the women on the ground by the side of the king wore large white dresses, which covered their persons like a winding-sheet. Young virgins, according to custom, appeared in a state of nudity; many of them had wild flowers stuck behind their ears, and strings of beads, &c., round their loins; but want of clothing did not seem to damp their pleasure in the entertainment, for they appeared to enter into it with as much zest as any of their companions. Of the different coloured tobes worn by the men, none looked so well as those of a deep crimson colour on some of the horsemen; but the clean white tobes of the Mohammedan priests, of whom not less than a hundred were present on the occasion, were extremely neat and becoming. The sport terminated without the slightest accident, and the king's dismounting was a signal for the people to disperse.

"We have here endeavoured, to the best of our ability, to describe an African horse-race, but it is impossible to convey a correct idea of the singular and fantastic appearance of the numerous groups of people that met our view on all sides, or to describe their animation and delight; the martial equipment of the soldiers and their noble steeds, and the wild, romantic, and overpowering interest of the whole mass. Singing and dancing have been kept up all night, and the revellers will not think of retiring to rest till morning."

Mr. Haydon has completed his Xenophon and the 10,000 first seeing the Sea from Mount Thèches—a brilliantly glowing page of Grecian heroism, and a splendid specimen of the highest order of historical painting. It represents the celebrated retreat of the 10,000 valorous Greeks, with Xenophon at their head, whose only hope of release from one of the most perilous situations—was to reach the sea. The action of the picture is thus described by the artist:

"This, of course, was accepted—they altered their course, and, while the army was in full march over Mount Thèches, the advanced guard, in coming to the top, came suddenly in view of a magnificent valley, with the SEA in the extreme distance, glittering along an extended coast, and mingling with the hazy horizon!

"The whole guard burst out into a furious shout of enthusiastic exultation the SEA! the SEA! was echoed along the whole army, below in the passes; Xenophon, from the uproar, thinking they were attacked, galloped forward with the cavalry; 1 but seeing the cause, joined in the shout! The feeling was too powerful to be resisted—men, women, and children, the veteran, the youth, the officer, the private, beasts of burden, cattle, and horses, broke up like a torrent that had burst a mountain rock, and rushed, headlong to the summit!

"As each, in succession, lifted his head up above the rocks, and really saw the SEA, nothing could exceed the affecting display of gratitude and enthusiastic rapture!—some embraced, some cried like children, some stamped like madmen, some fell on their knees and thanked the gods, others were mute with gratitude, and stared as if bewildered!

"Never was such a scene seen! as soon as the soldiers recovered something like reason, a trophy on a heap of stones and shields, was erected. The army descended the Colchian Mountains, and reached Trapezus, the modern Trebizon, after a march of 1,155 leagues, during two hundred and fifteen days, where they embarked for their native country.

"The moment I have taken is when Xenophon seeing the sea has rode forward to shout it to the army. He is waving his helmet with one hand, and pointing to the sea with the other, mounted on a skew-bald charger.

"Below the army are rushing up—in the centre is an officer, on a blood Arab, carrying his wife. A veteran soldier on his left is supporting an exhausted youth who has sunk on his shield, and pointing out the path to the army. On the right, is a young man carrying up on his back his aged father who has lost his helmet—the trumpeter lower down, is blowing a blast to collect the rear guard which are mounting behind him, while near the mare's head is the [pg 219] Greek band with trumpets and cymbals encouraging the men. The army is rushing up under an opening of the rock to the left, while the advanced guard of cavalry are trotting down the shelving top of a precipice, the horses excited and snuffing up the sea air with ecstasy."

It would, however, be difficult to convey, by description, the overpowering energy and mighty struggle of the scene before us, or the masterly skill with which the painter has brought within a few square feet of canvass, one of the most astounding events in the history of man. Its moral tendency should be a lasting lesson of the secret spring of honourable success in life—decision of character and well-directed energies to accomplish great ends—though applicable to every station of life, however humble.

Xenophon is a distant figure in this effective picture: his action, as well as that of the cavalry, about him is admirably expressed: he appears on the pinnacle of triumph; his charger snuffs the very gale of glory, and the uncurbed energy of exultation seems to animate those immediately around him. The eye descends to the checkered toil beneath: the brawny soldier bearing the delicate form of his lovely wife, which is well contrasted with the bold, muscular figure of the former: the exhausted youth, and the veteran directing the army, but especially the former, are finely drawn and painted: the bare head of the aged man, with his few last locks fluttering in the wind, contrasts with the burly-headed trumpeter, whose thick throat and outblown cheeks denote the energy which he is throwing into this last inspiring call to victory over difficulty. The head of the soldier's blood Arab is one of the finest studies of the group: you almost see the breath of his nostrils; the hinder parts and tail of the horse are not quite of equal merit. These are but a few of the points of excellence in the picture: its colouring is censurable for its roughness, especially by those who enjoy the smoothly-finished productions of certain British artists; but we may look to such in vain for the powerful drawing and forcible expression which characterize this, the finest of Mr. Haydon's pictures.

In the same room, vis a vis the Xenophon, is the Mock Election picture described at some length in No. 304, of The Mirror. About the walls are thirteen finished sketches and studies also by Mr. Haydon. We may notice them anon.

An exhibition of paintings in enamel colours on glass has been opened at No. 357, Strand, which is likely to prove attractive to the patrons of art as well as to the sight-seeing public. It consists of faithful copies of Harlow's Kemble Family; Martin's Belshazzar, Joshua, and Love among the Roses; Sir Joshua Reynolds's celebrated group of Charity, and a tasteful composition of a Vase of Flowers with fruit, &c. The whole are ably executed, and calculated to advance the art of painting on glass to its olden eminence. The copies from Martin are of the size of his prints, and are perhaps the most successful: that of Joshua commanding the Sun to stand still is powerfully striking: the supernal light breaking from the dense panoply of clouds is admirably executed, and the minuteness of the architectural details and the fighting myriads is indescribable. In the Hall of Belshazzar, the perspective is ably preserved throughout, though the interest of the picture is not of that intense character that we recognise in Joshua. The painting of the Trial of Queen Katherine is of the size of Clint's masterly print: it required greater delicacy in copying than did either of its companion pictures, since it has few of the strong lights and vivid contrasts so requisite for complete success on glass. The costumes are well managed, as the red of Wolsey's robes, and the massy velvet dress of Katherine. Of this print, by the way, there are appended to the Catalogue a few particulars which may be new and pleasant to the reader. Thus:—

"The Picture is on mahogany panel, 1-1/2 inch in thickness, and in size, about 7 feet by 5 feet. It originated with Mr. T. Welsh, the meritorious professor of music, in whose possession the picture remains. This gentleman commissioned Harlow to paint for him a kit-cat size portrait of Mrs. Siddons, in the character of Queen Katherine in Shakspeare's Play of Henry VIII., introducing a few of the scenic accessories in the distance. For this portrait Harlow was to receive twenty-five guineas; but the idea of representing the whole scene occurred to the artist, who, with Mr. Welsh, prevailed upon most of the actors to sit for their portraits: in addition to these, are introduced portraits of the friends of both parties, including the artist himself. The sum ultimately paid by Mr. Welsh was one hundred guineas; and a like sum was paid by Mr. Cribb, for Harlow's permission to engrave the well-known print, to which we have already [pg 220] adverted. The panel upon which the picture is painted, is stated to have cost the artist 15l.

"Concerning this picture we find the following notice by Knowles, in his Life of Fuseli. 'In the performance of this work, he (Harlow) owed many obligations to Fuseli for his critical remarks; for, when he first saw the picture, chiefly in dead-colouring, he said, 'I do not disapprove of the general arrangement of your work, and I see you will give it a powerful effect of light and shadow; but you have here a composition of more than twenty figures, or, I should rather say, parts of figures, because you have not shown one leg or foot, which makes it very defective. Now, if you do not know how to draw legs and feet, I will show you,' and taking up a crayon, he drew two on the wainscot of the room. Harlow profited by these remarks; and the next time we saw the picture, the whole arrangement in the fore-ground was changed. Fuseli then said, 'so far you have done well: but now you have not introduced a back figure, to throw the eye of the spectator into the picture;' and then pointed out by what means he might improve it in this particular. Accordingly, Harlow introduced the two boys who are taking up the cushion." 2

"It has been stated that the majority of the actors in the scene sat for their portraits in this picture. Mr. Kemble, however, refused, when asked to do so by Mr. Welsh, strengthening his refusal with emphasis profane. Harlow was not to be defeated, and he actually drew Mr. Kemble's portrait in one of the stage-boxes of Covent Garden Theatre, while the great actor was playing his part on the stage. The vexation of such a ruse to a man of Mr. Kemble's temperament, can better be imagined than described: how it succeeded, must be left to the judgment of the reader. Egerton, Pope, and Stephen Kemble, were successively painted for Henry VIII., the artist retaining the latter. The head of Mr. Charles Kemble was likewise twice painted: the first, which cost Mr. C. Kemble many sittings, was considered by himself and others, very successful. The artist thought otherwise; and, contrary to Mr. Kemble's wish and remonstrance, he one morning painted out the approved head: in a day or two, however, entirely from recollection, Harlow re-painted the portrait with increased fidelity. Mr. Cunningham, we may here notice, has erroneously stated, that Harlow required but one sitting of Mrs. Siddons. The fact is, the accomplished actress held her up-lifted arm frequently till she could hold it raised no longer, and the majestic limb was finished from another original."

The lights of Love among the Roses are vivid and beautiful: the whole composition will be recollected as of a charming character.

By the way, persons unpractised in the art of painting on glass, or in transparent enamel, have but a slender idea of its difficulties. Crown-glass is preferred for its greater purity. The artist has not only to paint the picture, but to fire it in a kiln, with the most scrupulous attention to produce the requisite effects, and the uncertainty of this branch of the art is frequently a sad trial of patience. Hence, the firing or vitrification of the colours is of paramount importance, and the art thus becomes a two-fold trial of skill. Its cost is, however, only consistent with its brilliant effect.

What can we do with this pamphlet?—British Relations with the Chinese Empire—Comparative Statement of the English and American Trade with India and Canton. What a book for a tea-drinking old lady, or Dr. Johnson, of tea-loving notoriety, with his thirteen cups to the dozen.

"The writer has passed the last eleven years of his life in visiting every quarter of the globe, and the colonial possessions of Great Britain, in order to acquire an intimate knowledge of her commercial affairs, for political purposes." The reader will, perhaps, say this pamphlet is purely political, and what have you to do with it? But it is not so: there are facts in these pages which interest every one and come home to every man's mouth: the political purpose is to us like chaff; and these facts like grains of wheat, so we will even pick a few. Meanwhile, the whole pamphlet must be important to all, as to ourselves parts are interesting: it represents the literature of the tea trade, and, best of all, the profitable literature of L.s.d. It is written in a patriotic spirit; witness this extract from the preface: "To a commercial union of wealth, and a co-operation of talent and patriotism, a small island in the Western Atlantic is indebted for the acquisition of one of the most splendid empires that ever was subjected to the dominion of man, and [pg 221] also for the rise and progress of an extraordinary commerce with a people inhabiting a distant hemisphere, and heretofore shut out from all intercourse with the majority of the human race;—a commerce equal in extent to 10,000,000l. annually, and involving property to the amount of ten times that sum."

Our facts must stand isolated, since to weave them into an argument would be altogether foreign to our purpose.

East India Company.—Although the East India Company can alone import tea, they cannot choose their own time of sale; they are compelled to put up the tea at an advance of one penny (they do at one farthing) per lb.; they are obliged to have twelve months' stock in hand; and while the tea in America has increased in price and diminished in consumption, the very reverse has taken place in England, as official returns prove!

China presents the very remarkable spectacle of a civilization entirely political, whose principal aim has constantly been to draw closer the bonds which unite the society it formed, and to merge, by its laws, the interest of the individual in that of the public; an empire possessing an active, skilful, and contented population of 155,000,000 souls, who are spread over 1,372,450 square miles of the fairest and, probably, earliest inhabited region of the globe—that maintains a standing army of 1,182,000 men, and levies a revenue of only 11,649,912l. sterling—an empire that has preserved the records of its dominion and the integrity of its name from a period of three thousand years antecedent to our era, while the most powerful monarchies of remote or modern ages have dwindled into nothingness, or been borne towards the ocean of eternity, by the swiftly destructive gulf of time,—an empire whose people have materially contributed to advance the civilization of Europe and America, by the discovery of the most useful arts and sciences, such as writing, 3 astronomy, the mariner's compass, gunpowder, sugar, silk, porcelain, the smelting and combination of metals,—and, in fine, enjoying within its own territories all the necessaries and conveniencies, and most of the luxuries of life; standing, as it proudly asserts, in no need of intercourse with other countries, 4 which it is its studied policy to prohibit, 5 openly and arrogantly proclaims its total independence of every nation in the world!

Origin of the Tea Trade of the East India Company.—In 1668, the East India Company ordered "one hundred pounds weight of goode tey" to be sent home on speculation. A taste for the Chinese herb was created and carefully fostered; the invoice was increased from year to year, until it now amounts to 30,000,000 pounds weight (notwithstanding the excessive duty of 100 per cent, and the onerous restrictions of the commutation act, since 1784), yielding an annual revenue to government, on a luxury of life, of about 3,300,000l. sterling, with scarcely any trouble or expense in the collecting;—employing 35,000 tons of the finest shipping,—requiring annually nearly 1,000,000l. sterling worth of cotton, woollen, and iron manufactures, and affording employment to a numerous class of society, for the wholesale and retail dealing in a leaf collected on the mountains of a distant continent!

To enable them the better to prosecute this valuable commerce, the East India Company sought and obtained permission to build a factory at Canton, where their agents were permitted to reside six months in the year—a favour specifically accorded as a matter of compassion to foreigners, who are carefully debarred all intercourse with the interior of the country; a dread being entertained that the introduction of Europeans to settle in China, would lead (according also to ancient prophecy) to the total subversion of the empire.

Other brunches of trade were subsequently added to that of tea. In 1773, the East India Company made a small adventure of opium 6 from Bengal to Canton; and the consumption of opium increased as rapidly among the Chinese as tea did among the English, until it now yields (although a contraband trade) 14,000,000 Spanish dollars annually, 7 and pays a revenue to the Indian Government of 1,800,000l. sterling. Raw cotton forms another extensive article of export to China; it is in general a less profitable remittance than bills of exchange, but the exportation is [pg 222] encouraged for the benefit of the Indian territories.

Character of the Chinese.—The Chinese are a haughty and independent race of people, whose commercial policy it is to prohibit, as much as possible, every species of manufactures 8 and bullion; and encourage the importation of food, and raw produce; holding themselves aloof from Europeans, and particularly jealous of Great Britain, on account of the proximity of her Indian empire; exacting upwards of 1,000l. in fees and port dues 9 on each foreign vessel that enters Canton, the only harbour to which they are admitted, 10 imposing severe sea and inland customs and regulations regarding woollen and other manufactures, entirely interdicting some branches of trade, and permitting all by sufferance, or as a matter of favour rather than from necessity, or by right.

Tea in Ireland.—In Ireland, the consumption of tea in the year 1828, was 1,300,000 lbs. less than in 1827; and although the population of Ireland has rapidly increased, indeed, nearly doubled itself, since the commencement of the present century, yet the quantity of tea imported into that country is 400,000 lbs. less in 1828, than it was in 1800!

Tea in America and England.--

American consumption of tea.

1819--5,480,884 lbs.

1827--5,372,956

---------

Decrease! 107,828 lbs.

British consumption of tea.

1819--24,093,619 lbs.

1827--27,841,284

----------

Increase 3,747,665 lbs.

Consumption of Sugar.--

In France each individual, annually 5 lbs.

Hamburgh do. do. 10

Germany do. throughout 6

United States do. do. 8

Ireland do. do. 3

Great Britain do. do. 14

Fourteen pounds of sugar per annum, will afford but little more than half an ounce a day to each individual; a quantity, which it is well known the youngest child will consume, and yet a large portion of the sugar entered for home consumption, is used in breweries, and distilleries, so that it is even doubtful, whether the personal direct consumption of tea or sugar be the greatest; notwithstanding the latter may be had in such great abundance and in every country within the tropics.

Price of Tea in China.—Bohea, which cannot be purchased in China at less than eight-pence half-penny, may be obtained at Antwerp for 7-3/4d.; in France for 6-1/2d.; and at Hamburg for 5d.! Congou, of which the Canton price is from 11d. to 1s. per lb., may be bought in France at 10-1/2d., and at Hamburg from 8-1/4d. to 10-1/4d.! Canton price for Hyson, 1s. 9-3/4d.; French price 1s. 8-1/2d. Young Hyson costs in Canton about 1s. 8-1/2d. per lb., and only one half that sum at Hamburg!! The Chinese cannot afford to sell Twankay at less than 11d. per lb.; but the American speculators enable the good people of Hamburg to drink it at seven-pence farthing! Souchong, a good quality tea, sells at Hamburg for five-pence per lb., which is the same price as the vilest Bohea costs in the Hamburg market, and is only one-half the price of Bohea in Canton.

Cost of a pound of Seven Shilling Tea.—Take a pound of Congou for instance, according to the evidence of Mr. Mills, a tea broker, before the House of Lords:

One pound of good Congou,

put up at the East India

Company's sales at --------------- 1 8

Buyers purposely and for

their own advantage raise it ----- 0 9

----

Purchasing price by the Brokers --- 2 5

Duty levied by the Crown ----------------- 2 5

Retailer's profit, brokerage, &c. -------- 2 2

----

Shop price 7 0

Thus it will be seen, the tea that the Company offers for sale to the consumer at 1s. 8d., or at the utmost say 2s., is enhanced to 7s. before it finds its way to the drinker's breakfast table.

Coffee-Shops.—There are 3,000 coffee shops in London, in which are daily consumed 2,000 lbs. of tea and 15,000 lbs. of coffee. The consumption of coffee in these establishments has increased as follows:—In 1829, 1,978,600 lbs. In 1830, 2,251,300 lbs. In 1831, 2,899,870. Of tea the increase has only been, during the same periods, 239,700 lbs.—249,400 lbs.—263,000 lbs.

The following are the items of expenses, laid down by Colonel Cooke, in his "Observations on Fox-hunting," published a few years since. The calculation supposes a four-times-a-week country; but it is generally below the mark; we should say, at least one-half:—

Fourteen horses ................................. £700

Hounds' food, for fifty couples .................. 275

Firing ............................................ 50

Taxes ............................................ 120

Two whippers-in, and feeder ...................... 210

Earth stopping .................................... 80

Saddlery ......................................... 100

Farriery, shoeing, and medicine .................. 100

Young hounds purchased, and expenses at walks..... 100

Casualties ....................................... 200

Huntsman's wages and his horses .................. 300

-----

£2235

Of course, countries vary much in expense from local circumstance; such as the necessity for change of kennels, hounds sleeping out, &c.&c. In those which are called hollow countries, consequently abounding in earths, the expense of earth-stopping often amounts to 200l. per annum, and Northamptonshire is of this class. In others, a great part of the foxes are what is termed stub-bred (bred above ground), which circumstance reduces the amount of this item.—Quarterly Review.

Curious Epitaph.—In Nichols's History of Leicestershire, is inserted the following epitaph, to the memory of Theophilus Cave, who was buried in the chancel of the church of Barrow on Soar:

"Here in this Grave there lies a Cave;

We call a Cave a Grave;

If Cave be Grave, and Grave be Cave,

Then reader, judge, I crave,

Whether doth Cave here lye in Grave,

Or Grave here lye in Cave:

If Grave in Cave here bury'd lye,

Then Grave, where is thy victory?

Goe, reader, and report here lyes a Cave

Who conquers death, and buryes his own Cave."

P.T.W.

Equality.—All men would necessarily have been equal, had they been without wants; it is the misery attached to our species, which places one man in subjection to another: Inequality is not the real grievance, but dependence. It is of little consequence for one man to be called his highness, and another his holiness; but it is hard for one to be the servant of another.—Voltaire.

The famous Duke of Cumberland showed more cleverness as a boy, than he ever did as a general. Having displeased his mother one day, she sent him to his chamber, and when he appeared again, she asked him what he had been doing. "Reading," replied the boy.—"Reading what?"—"The Scriptures."—"What part of the Scriptures?"—"That part where it is written, 'Woman! what hast thou to do with me?'" After the loss of a battle, an English prisoner observing to a French officer, that they might have taken the duke himself prisoner; "Yes," replied the Frenchman, "but we took care not to do that—he is of far more use to us at the head of your army."—Georgian Era.

The letter Y.—Pythagoras used the Y as a symbol of human life. "Remember (says he) that the paths of virtue and of vice resemble the letter Y. The foot representing infancy, and the forked top the two paths of vice and virtue, one or the other of which people are to enter upon, after attaining to the age of discretion."

P.T.W.

Royal Combat.—Near the city of Gloucester, on the Severn, the river dividing, forms a small island called Alney, which is famous for a royal combat fought on it, between Edmund Ironside and Canute the Dane, to decide the fate of the kingdom, in sight of both their armies. Canute was wounded, when he proposed an amicable division, and accordingly he obtained the northern part; the southern falling to Edmund.

E.F.

Effect of Music.—A Scotch bag-piper traversing the mountains of Ulster, in Ireland, was one evening encountered by a starved Irish wolf. In his distress the poor man could think of nothing better than to open his wallet, and try the effects of his hospitality; he did so, and the savage swallowed all that was thrown to him, with so improving a voracity as if his appetite was but just returning to him. The whole stock of provision was, of course, soon spent, and now his only recourse was to the virtues of his bagpipe; which the monster no sooner heard, than he took to the mountains with the same precipitation he had left them. The poor piper could not so perfectly enjoy his deliverance, but that, with an angry look, at parting, he shook his head, saying, "Ay, are these your tricks? Had I [pg 224] known your humour, you should have had your music before supper."—Bowyer's Anecdotes.

Epitaph on Mr. Nightingale, Architect.

As the birds were the first of the architect kind,

And are still better builders than men,

What wonders may spring from a Nightingale's mind,

When St. Paul's was produced by a Wren.

Poets.

The effects of disappointed love ......Akenside. Part of a lady's dress ................Spencer. What the ladies do, and a weight ......Chatterton. A manufactory, and a weight ...........Milton. The prayers of a glutton ..............Moore. An indication of old age ..............Gray. What a mortgage will do ...............Cumberland. The contributions of a miser ..........Little. A troublesome companion ...............Bunyan. The soldier's home, and an alarm ......Campbell.

The Pyramids.—The Egyptians, according to Herodotus, hated the memory of the kings who built the pyramids. The great pyramid occupied a hundred thousand men for twenty years in its erection, without counting the workmen who were employed in hewing the stones and conveying them to the spot where the pyramid was built. Herodotus speaks of this work as a torment to the people, and doubtless, the labour engaged in raising huge masses of stone, that was extensive enough to employ a hundred thousand men for twenty years, equal to two millions of men for one year, must have been fearfully tormenting. It has been calculated that the steam engines of England worked by thirty-six thousand men, would raise the same quantity of stones from the quarry, and elevate them to the same height as the great pyramid, in the short space of eighteen hours. It was recorded on the pyramid, that the onions, radishes, and garlic, which the labourers consumed, cost sixteen hundred talents of silver, which is equivalent to several million pounds.

SWAINE.

The generality of mankind will not bear to be viewed too closely, or too often: they lose their value on a nearer approach; which made the honest countrymen say to his friend, who was boasting of a legacy bestowed upon him by a person, into whose company he had accidentally fallen only once in his life, "Ah, Jonathan, if he had seen thee twice, he would not have left thee a farthing."

Friendship.—Friendship is of so delicate and so nice a texture, so defenceless against evil impressions, and so apt to wither at the least blast of jealousy, that we may say with Horace,

Felices ter et amplius,

Quos irrupta tenet copula; nec malis

Divulsus querimoniis,

Suprema citius solvet amor die.

Ode 13, lib. i.

"Happy, thrice happy they, whose friendships prove

One constant scene of unmolested love,

Whose hearts right temper'd feel no various turns,

No coolness chills them, and no madness burns.

But free from anger, doubts, and jealous fear,

Die as they liv'd, united and sincere."

The love between friends is certainly most harmonious when wound up to the highest pitch; but at that very time, is in greatest danger of breaking: and upon the whole, the strongest friendships may be compared to the strongest towns, which are too well fortified to be taken by open attacks; but are always liable to be undermined by treachery or surprise.

A.J.

In the ancient German empire, such persons as endeavoured to sow sedition, and disturb the public tranquillity, were condemned to become objects of public notoriety and derision, by carrying a dog upon their shoulders, from one great town to another. The Emperors, Otho I. and Frederick Barbarossa, inflicted this punishment on noblemen of the highest rank.

With Engravings, price 5s.

ARCANA OF SCIENCE And Annual Register of the Useful Arts for 1832. Fifth Year.

The Volume for 1828, (fourth edition,) 4s. 6d. The Volume for 1829 and 1830, (nearly out of print.) and 1831, 5s. each.

"Any young gardener, who besides prosecuting his particular profession, wishes to be apprized of what is going on in the great world of human action generally, cannot possibly spend 5s. more efficiently than in the purchase of this book; * * * the first spare sovereign to the acquisition of the four back volumes, and then subsequently continue the work annually."—Gardeners' Magazine, (just published.)

Printed for JOHN LIMBIRD, 143, Strand.

Footnote 3: (return)A celebrated Hungarian, named Cosmös de Körös, has lately discovered in a Thibetian monastery, where he has been engaged translating an Encyclopaedia, that lithography and movable wooden types were known to the Chinese many centuries ago.

Footnote 4: (return)A Chinese who leaves his country is considered as a traitor, and is punished with death if he ever return to it.

Footnote 6: (return)The Chinese use this stimulant as we do wine and spirits, and with perhaps, less deleterious consequences to their health, and less evil results to their morals.

Footnote 7: (return)About 7,000,000 of which, or bars or moulds of silver to that amount, are sent to India, the Chinese being unable to make sufficient return in merchandise. This remittance is of material assistance in helping to provide funds on the spot for the purchase of tea.

Footnote 8: (return)A late No. of the Canton Register, mentions a fact, which is one instance out of many, of the desire to be independent of foreigners; it is as follows:—"Prussian blue, an article which was formerly brought in considerable quantities from England, is now totally shut out from the list of imports, in consequence of its mode of manufacture being acquired by a Chinaman in London; and from timely improvement it has been brought to that perfection which renders the consumers independent of foreign supply!"

Footnote 10: (return)The Chinese will not admit a foreign nation to trade at two places; for instance, the Russians are excluded from Canton because they enjoy an overland trade at Kiachia, which is 4,311 miles from St. Petersburgh, and 1,014 miles distant from Pekin.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD, 143, Strand, (near Somerset House.) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic, G.G. BENNIS, 55, Rue Neuve, St. Augustin, Paris; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.