Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 562, Saturday, August 18, 1832.

Author: Various

Release date: March 1, 2004 [eBook #11568]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Bill Walker and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

| VOL. XX. NO. 562.] | SATURDAY, AUGUST 18, 1832. | [PRICE 2d. |

The Genesee is one of the most picturesque rivers of North America. Its name is indeed characteristic: the word Genesee being formed from the Indian for Pleasant Valley, which term is very descriptive of the river and its vicinity. Its falls have not the majestic extent of the Niagara; but their beauty compensates for the absence of such grandeur.

The Genesee, the principal natural feature of its district, rises on the Grand Plateau or table-land of Western Pennsylvania, runs through New York, and flows into Lake Ontario, at Port Genesee, six miles below Rochester. At the distance of six miles from its mouth are falls of 96 feet, and one mile higher up, other falls of 75 feet.1 Above [pg 98] these it is navigable for boats nearly 70 miles, where are other two falls, of 60 and 90 feet, one mile apart, in Nunda, south of Leicester. At the head of the Genesee is a tract six miles square, embracing waters, some of which flow into the gulf of Mexico, others into Chesapeake Bay, and others into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This tract is probably elevated 1,600 or 1,700 feet above the tide waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

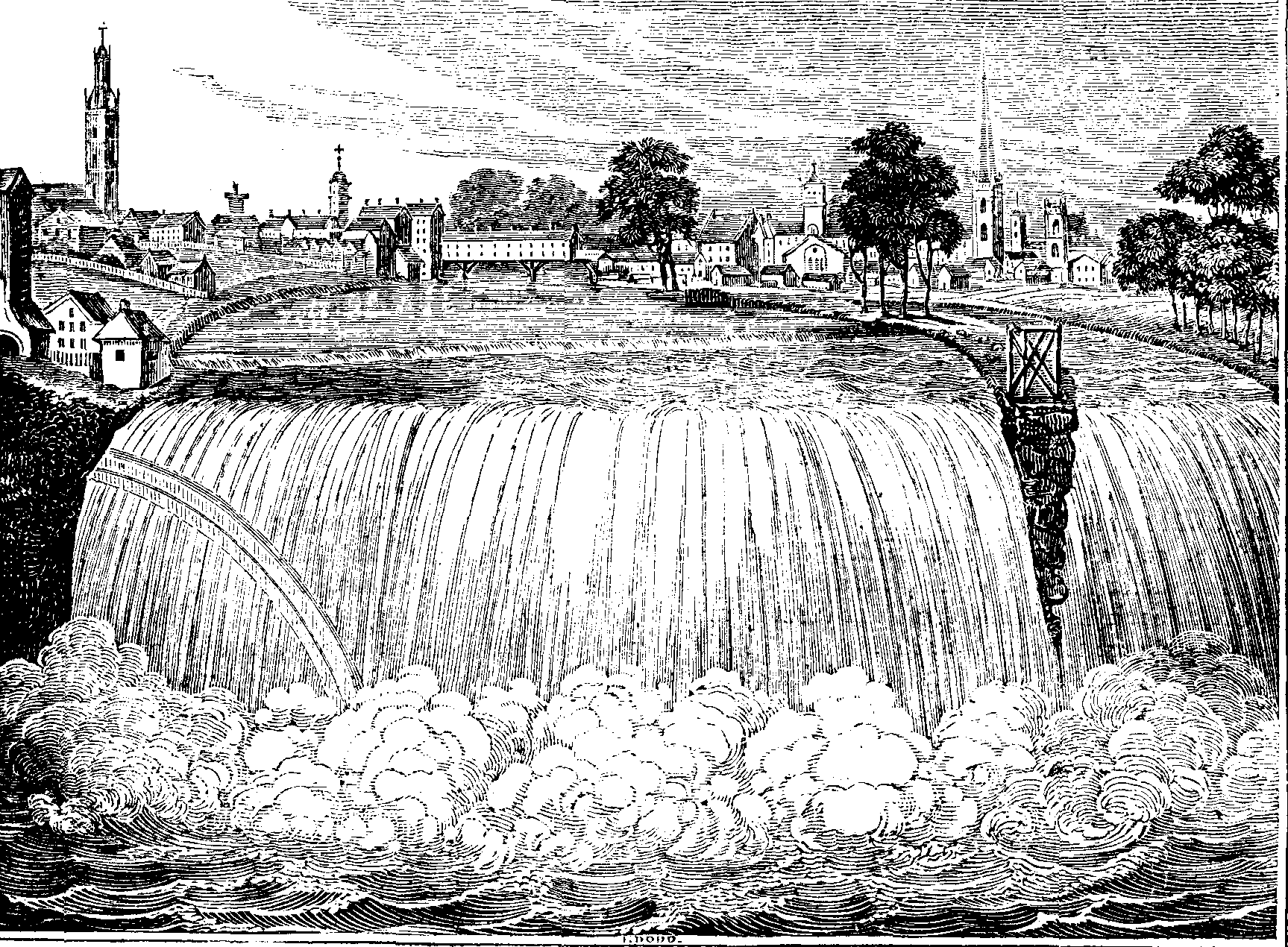

The Engraving includes the falls of the river, with the village of Rochester, seven miles south of Lake Ontario. This place, for population, extent, and trade, will soon rank among the American cities: it was not settled until about the close of the last war; its progress was slow until the year 1820, from which period it has rapidly improved. In 1830 it contained upwards of 12,000 inhabitants: the first census of the village was taken in December, 1815, when the number of inhabitants was three hundred and thirty-one. The aqueduct which takes the Erie canal across the river forms a prominent object of interest to all travellers. It is of hewn stone, containing eleven arches of 50 feet span: its length is 800 feet, but a considerable part of each end is hidden from view by mills erected since its construction.

On the brink of the island which separates the main stream of the river from that produced by the waste water from the mill-race, will be seen a scaffold or platform from which an eccentric but courageous adventurer, named Sam Patch, made a desperate leap into the gulf beneath. Patch had obtained some celebrity in freaks of this description, though his feats be not recorded, like the hot-brained patriotism of Marcus Curtius in olden history. At the fall of Niagara, Patch had before made two leaps in safety—one of 80 and the other of 130 feet, in a vast gulf, foaming and tost aloft from the commotion produced by a fall of nearly 200 feet. In November, 1829, Patch visited Rochester to astonish the citizens by a leap from the falls. His first attempt was successful, and in the presence of thousands of spectators he leaped from the scaffold to which we have directed the attention of the reader, a distance of 100 feet, into the abyss, in safety. He was advertised to repeat the feat in a few days, or, as he prophetically announced it his "last jump," meaning his last jump that season. The scaffold was duly erected, 25 feet in height, and Patch, an hour after the time was announced, made his appearance. A multitude had collected to witness the feat; the day was unusually cold, and Sam was intoxicated. The river was low, and the falls near him on either side were bare. Sam threw himself off, and the waters (to quote the bathos of a New York newspaper) "received him in their cold embrace. The tide bubbled as the life left the body, and then the stillness of death, indeed, sat upon the bosom of the waters." His body was found past the spring at the mouth of the river, seven miles below where he made his fatal leap. It had passed over two falls of 125 feet combined, yet was not much injured. A black handkerchief taken from his neck while on the scaffold, and tied about the body, was still there. He is stated to have had perfect command of himself while in the air; and, says the journalist already quoted, "had he not been given to habits of intoxication, he might have astonished the world, perhaps for years, with the greatest feats ever performed by man."

The Genesee river waters one of the finest tracts of land in the state of New York. Its alluvial flats are extensive, and very fertile. These are either natural prairies, or Indian clearings, (of which, however, the present Indians have no tradition,) and lying, to an extent of many thousand acres, between the villages of Genesee, Moscow, and Mount Morris, which now crown the declivities of their surrounding uplands; and, contrasting their smooth verdure with the shaggy hills that bound the horizon, and their occasional clumps of spreading trees, with the tall and naked relics of the forest, nothing can be more agreeable to the eye, long accustomed to the uninterrupted prospect of a level and wooded country.

Away o'er the dancing wave,

Like the wings of the white seamew;

How proudly the hearts of the youthful brave

Their dreams of bliss renew!

And as on the pathless deep,

The bark by the gale is driven,

How glorious it is with the stars to keep

A watch on the beautiful heaven.

The winds o'er the ocean bear

Rich fragrance from the flow'rs,

That bloom on the sward, and sparkle there

Like stars in their dark blue bow'rs.

The visions of those that sail

O'er the wave with its snow-white foam,

Are haunted with scenes of the beauteous vale

That encloses their peaceful home.

They have wander'd through groves of the west,

Illumed with the fire-flies' light;

But their native land kindles a charm in each breast,

Unwaken'd by regions more bright.

The haunts that were dear to the heart

As an exquisite dream of romance,

Strew thoughts, like sweet flow'rs, round its holiest part,

And their fancy-bound spirits entrance.

Then away with the fluttering sail!

And away with the bounding wave!

While the musical sounds of the ocean-gale

Are wafted around the brave!

Ray wittily observes that an obscure and prolix author may not improperly be compared to a Cuttle-fish, since he may be said to hide himself under his own ink.

Doubt-beladen, dim and hoary,

O'er us breaks the mighty day,

And the sunbeam, cold and gory,

Lights us on our fearful way.

In the womb of coming hours,

Destinies of empires lie,

Now the scale ascends, now lowers,

Now is thrown the noble die.

Brothers, the hour with warning is rife;

Faithful in death as you're faithful in life,

Be firm, and be bound by the holiest tie,

In the shadows of the night,

Lie behind us shame and scorn;

Lies the slave's exulting might,

Who the German oak has torn.

Speech disgrac'd in future story,

Shrines polluted (shall it be?)

To dishonour pledg'd our glory,

German brothers, set it free.

Brothers, your hands, let your vengeance be burning,

By your actions, the curses of heaven be turning,

On, on, set your country's Palladium free.

Hope, the brightest, is before us,

And the future's golden time,

Joys, which heaven will restore us,

Freedom's holiness sublime.

German bards and artists' powers,

Woman's truth, and fond caress,

Fame eternal shall be ours,

Beauty's smile our toils shall bless.

Yet 'tis a deed that the bravest might shake,

Life and our heart's blood are set on the stake;

Death alone points out the road to success.

God! united we will dare it;

Firm this heart shall meet its fate,

To the altar thus I bear it,

And my coming doom await.

Fatherland, for thee we perish,

At thy fell command 'tis done,

May our loved ones ever cherish

Freedom, which our blood has won.

Liberty, grow o'er each oak-shadow'd plain,

Grow o'er the tombs of thy warriors slain,

Fatherland, hear thou the oath we have sworn.

Brothers, towards your hearts' best treasures,

Cast one look, on earth the last,

Turn then from those once prized pleasures,

Wither'd by the hostile blast.

Though your eyes be dim with weeping,

Tears like these are not from fear,

Trust to God's own holy keeping,

With your last kiss, all that's dear.

All lips that pray for us, all hearts that we rend

With parting, O father, to thee we commend,

Protect them and shield them from wrongs and despair.

H.

Goodness of temper may be defined, to use the happy imagery of Gray, "as the sunshine of the heart." It is a more valuable bosom-attendant under the pressure of poverty and adversity, and when we are approaching the confines of infirmity and old age, than when we are revelling in the full tide of plenty, amid the exuberant strength and freshness of youth. Lord Bacon, who has analyzed some of the human accompaniments so well, is silent as to the softening sway and pleasing influence of this choice attuner of the human mind. But Shaftesbury, the illustrious author of the Characteristics, was so enamoured of it, that he terms "gravity (its counterpart,) the essence of imposture;" and so it is, for to what purpose does a man store his brain with knowledge, and the profitable burden of the sciences, if he gathers only superciliousness and pride from the hedge of learning? instead of the milder traits of general affection, and the open qualities of social feelings. I remember, when a youth, I was extremely fond of attending the House of Commons, to hear the debates; and I shall never forget the repulsive loftiness which I thought marked the physiognomy of Pitt; harsh and unbending, like a settled frost, he seemed wrapped in the mantle of egotism and sublunary conceit; and it was from the uninviting expression of this great man's countenance, that I first drew my conceptions as to how a proud and unsociable man looked. With very different emotions I was wont to survey the mild but expressive features of his great opponent, Fox: there was a placidity mixed up with the graver lines of thought and reflection, that would have invited a child to take him by the hand; indeed, the witchcraft of Mr. Fox's temper was such, that it formed a triumphant source of gratulation in the circle of his friends, from the panegyric of the late Earl of Carlisle, during his boyish days at Eton, to the prouder posthumous circles of fame with which the elegant author of The Pleasures of Memory, has entwined his sympathetic recollections. The late Mr. Whitbread, although an unflinching advocate for the people's rights, and an incorruptible patriot in the true sense of the word, was unpopular in his office as a country magistrate, owing to a tone of severity he generally used to those around him. The wife of that indefatigable toiler in the Christian field, John Wesley, was so acid and acrimonious in her temper, that that mild advocate for spiritual affection, found it impossible to live with her. Rousseau was tormented by such a host of ungovernable passions, that he became a burden to himself and to every one around him. Lord Byron suffered a badness of temper to corrode him in the flower of his days. Contrasted with this unpleasing part of the perspective, let us quote the names of a few wise and good men, who have been proverbial for the goodness of their tempers; as Shakspeare, Francis I., and Henry IV. of France; "the great and good Lord Lyttleton," as he is called to the present day; John Howard, Goldsmith, Sir Samuel Romilly, Franklin, Thomson, the poet, Sheridan,2 and Sir Walter Scott. The late Sir William Curtis was known to be one of the best tempered men of his day, which made him a great favourite with the late king. I remember a little incident of Sir William's good-nature, which occurred about a year [pg 100] after he had been Lord Mayor. In alighting from his carriage, a little out of the regular line, near the Mansion House, upon some day of festivity, he happened inadvertently, with the skirts of his coat, to brush down a few apples from a poor woman's stall, on the side of the pavement. Sir William was in full dress, but instead of passing on with the hauteur which characterizes so many of his aldermanic brethren, he set himself to the task of assisting the poor creature to collect her scattered fruit; and on parting, observing some of her apples were a little soiled by the dirt, he drew his hand from his pocket and generously gave her a shilling. This was too good an incident for John Bull to lose: a crowd assembled, hurraed, and cried out, "Well done, Billy," at which the good-natured baronet looked back and laughed. How much more pleasing is it to tell of such demeanour than of the foolish pride of the late Sir John Eamer, who turned away one of his travellers merely because he had in one instance used his bootjack.

Probably our correspondent may recollect Sir William and the orange, at one of the contested City elections. A "greasy rogue" before the hustings, seeing the baronet candidate take an orange from his pocket, put up for the fruit, with the cry "Give us that orange, Billy." Sir William threw him the fruit, which the fellow had no sooner sucked dry, than he began bawling with increased energy, "No Curtis," "No Billy," &c. Such an ungrateful act would have soured even Seneca; but Sir William merely gave a smile, with a good-natured shake of the head. Sir William Curtis possessed a much greater share of shrewdness and good sense than the vulgar ever gave him credit for. At the Sessions' dinners, he would keep up the ball of conversation with the judges and gentlemen of the bar, in a fuller vein than either of his brother aldermen. It is true that he had wealth and distinction, all which his fellow citizens at table did not enjoy; and these possessions, we know, are wonderful helps to confidence, if they do not lead the holder on to assurance.—Ed. M.

A short time since, a brother sub. in my regiment was riding out round some hills adjoining the cantonment, when a cheetar, small tiger (or panther,) pounced on his dog. Seeing his poor favourite in the cheetar's mouth, like a mouse in Minette's, he put spurs to his horse, rode after the beast, and so frightened him, that he dropped the dog and made off. Three of us, including myself, then agreed to sit up that night, and watch for the tiger, feeling assured that his haunt was not far from our cantonment. So we started late at night, armed cap-à-pied, and each as fierce in heart as ten tigers; arrived at the appointed spot, and having selected a convenient place for concealment, we picketed a sheep, brought with us purposely to entice the cheetar from his lair. Singular to relate, this poor animal, as if instinctively aware of its critical situation, was as mute as if it had been mouthless, and during two or three hours in which we tormented it, to make it utter a cry, our efforts were of no avail. Hour after hour slipped away, still no cheetar; and about three o'clock in the morning, wearied with our fruitless vigil, we all began to drop asleep. I believe I was wrapped in a most leaden slumber, and dreaming of anything but watching for, and hunting tigers, when I was aroused by the most unnatural, unearthly, and infernal roaring ever heard. This was our friend, and for his reception, starting upon our feet, we were all immediately ready; but the cunning creature who had no idea of becoming our victim, made off, with the most hideous howlings, to the shelter of a neighbouring eminence; when sufficient daylight appeared, we followed the direction of his voice, and had the felicity of seeing him perched on the summit of an immense high rock, just before us, placidly watching our movements. We were here, too far from him to venture a shot, but immediately began ascending, when the creature seeing us approach, rose, opened his ugly red mouth in a desperate yawn, and stretched himself with the utmost nonchalance, being, it seems, little less weary than ourselves. We presented, but did not fire, because at that very moment, setting up his tail, and howling horribly, he disappeared behind the rock. Quick as thought we followed him, but to our great disappointment and chagrin, he had retreated into one of the numerous caverns formed in that ugly place, by huge masses of rock, piled one upon the other. Into some of these dangerous places, however, we descended, sometimes creeping, sometimes walking, in search of our foe; but not finding him, at length returned to breakfast, which I thought the most agreeable and sensible part of the affair. Some wit passed amongst us respecting the propriety of changing the name cheetar, into cheat-us; but were, on the whole, not pleased by the failure of our expedition; and I have [pg 101] only favoured you with this romantic incident in the life of a sub. as a specimen of the sort of amusement we meet with in quarters.

Natural Zoological Garden.

Secunderabad, 1828.

Your description of the London Zoological Garden, reminds me that there is, what I suppose I must term, a most beautiful Zoological Hill, just one mile and a half from the spot whence I now write; on this I often take my recreation, much to the alarm of its inhabitants; viz. sundry cheetars, bore-butchers, (or leopards) hyenas, wolves, jackalls, foxes, hares, partridges, etc.; but not being a very capital shot, I have seldom made much devastation amongst them. Under the hill are swamps and paddy-fields, which abound in snipe and other game. Now, is not this a Zoological Garden on the grandest scale?

Faire stood the wind for France,

When we, our sayles advance,

Nor now to proue our chance

Longer will tarry;

But putting to the mayne,

At Kaux, the mouth of Sene,

With all his martiall trayne,

Landed King Harry.

And taking many a fort,

Furnished in warlike sort,

Marcheth towards Agincourt,

In happy houre.

Skirmishing day by day,

With those that stop'd his way,

Where the French gen'ral lay

With all his power.

Which in his hight of pride.

King Henry to deride,

His ransom to prouide,

To our king sending.

Which he neglects the while,

As from a nation vile,

Yet with an angry smile,

Their fall portending.

And turning to his men,

Quoth our brave Henry, then,

"Though they to one be ten,

Be not amazed,

Yet have we well begunne,

Battells so bravely wonne,

Have ever to the sonne,

By fame beene raysed."

"And for myself," quoth he,

"This my full rest shall be,

England ne'er mourn for me,

Nor more esteem me.

Victor I will remaine,

Or on this earth be slaine,

Never shall shee sustaine

Losse to redeeme me."

Poiters and Cressy tell,

When most their pride did swell,

Under our swords they fell.

No lesse our skill is,

Then when oure grandsire great,

Clayming the regall seate,

By many a warlike feate,

Lop'd the French lillies.

The Duke of York so dread,

The vaward led,

Wich the maine Henry sped,

Amongst his Henchmen,

Excester had the rere,

A brauer man not there,

O Lord, how hot they were,

On the false Frenchmen.

They now to fight are gone,

Armour on armour shone,

Drumme now to drumme did grone,

To hear was wonder,

That with cryes they make,

The very earth did shake,

Thunder to thunder.

Well it thine age became

O noble Erpingham,

Which didst the signall ayme,

To our hid forces;

When from a meadow by,

Like a storme suddenly,

The English archery

Struck the French horses.

With Spanish Ewgh so strong,

Arrowes a cloth yard long,

That like to serpents stung,

Piercing the weather.

None from his fellow starts,

But playing manly parts,

And like true English hearts,

Stuck close together.

When downe their bowes they threw,

And forth their bilbowes drew,

And on the French they flew,

Not one was tardie;

Armes were from shoulders sent,

Scalpes to the teeth were rent,

Down the French pesants went,

Our men were hardie.

This while oure noble king,

His broad sword brandishing,

Downe the French host did ding,

As to o'erwhelme it.

And many a deep wound lent,

His armes with bloud besprent,

And many a cruel dent

Bruised his helmet.

Glo'ster, that duke so good,

Next of the royal blood,

For famous England stood,

With his braue brother,

Clarence, in steele so bright,

Though but a maiden knight.

Yet in that furious light

Scarce such another.

Warwick, in bloud did wade,

Oxford, the foe inuade,

And cruel slaughter made;

Still as they ran up,

Suffolk, his axe did ply,

Beavmont and Willovghby,

Ferres and Tanhope.

Upon Saint Crispin's day,

Fought was this noble fray,

Which fame did not delay,

To England to carry.

O when shall English men,

With such acts fill a pen,

Or England breed againe

Such a King Harry.

[The very recent publication of the ninth volume of the Encyclopaedia Americana6 enables us to lay before our readers the following interesting notices, connected with the national weal and internal economy of the United States of North America.]

Navy.—Since the late war, the growth and improvement of our navy has kept pace with our national prosperity. We could now put to sea, in a few mouths, with a dozen ships of the line; the most spacious, efficient, best, and most beautiful constructions that ever traversed the ocean. This is not merely an American conceit, but an admitted fact in Europe, where our models are studiously copied. In the United States, a maximum and uniform calibre of cannon has been lately determined on and adopted. Instead of the variety of length, form, and calibre still used in other navies, and almost equal to the Great Michael with her "bassils, mynards, hagters, culverings, flings, falcons, double dogs, and pestilent serpenters," our ships offer flush and uniform decks, sheers free from hills, hollows, and excrescences, and complete, unbroken batteries of thirty-two or forty-two pounders. Thus has been realized an important desideratum—the greatest possible power to do execution coupled with the greatest simplification of the means.

But, while we have thus improved upon the hitherto practised means of naval warfare, we are threatened with a total change. This is by the introduction of bombs, discharged horizontally, instead of shot from common cannon. So certain are those who have turned their attention to this subject that the change must take place, that, in France, they are already speculating on the means of excluding these destructive missiles from a ship's sides, by casing them in a cuirass of iron. Nor are these ideas the mere offspring of idle speculation. Experiments have been tried on hulks, by bombs projected horizontally, with terrible effect. If the projectile lodged in a mast, in exploding it overturned it, with all its yards and rigging; if in the side, the ports were opened into each other; or, when near the water, an immense chasm was opened, causing the vessel to sink immediately. If it should not explode until it fell spent upon deck, besides doing the injury of an ordinary ball, it would then burst, scattering smoke, fire, and death, on every side. When this comes to pass, it would seem that the naval profession would cease to be very desirable. Nevertheless, experience has, in all ages, shown that, the more destructive are the engines used in war, and the more it is improved and systematized, the less is the loss of life. Salamis and Lepanto can either of them alone count many times the added victims of the Nile, Trafalgar, and Navarino.

One effect of the predicted change in naval war, it is said, will be the substitution of small vessels for the larger ones now in use. The three decker presents many times the surface of the schooner, while her superior number of cannon does not confer a commensurate advantage; for ten bombs, projected into the side of a ship, would be almost as efficacious to her destruction as a hundred. As forming part of a system of defence for our coast, the bomb-cannon, mounted on steamers, which can take their position at will, would be terribly formidable. With them—to say nothing of torpedoes and submarine navigation—we need never more be blockaded and annoyed as formerly. Hence peaceful nations will be most gainers by this change of system; but it is not enough that we should be capable of raising a blockade: we are a commercial people: our merchant ships visit every sea, and our men-of-war must follow and protect them there.

Newspapers.—No country has so many newspapers as the United States. The following table, arranged for the American Almanac of 1830, is corrected from the Traveller, and contains a statement of the number of newspapers published in the colonies at the commencement of the revolution; and also the number of newspapers and other periodical works, in the United States, in 1810 and 1828.

STATES. 1775. 1810. 1828.

Maine 29

Massachusetts 7 32 78

New Hampshire 1 12 17

Vermont 14 21

Rhode Island 2 7 14

Connecticut 4 11 33

New York 4 66 161

New Jersey 8 22

Pennsylvania 9 71 185

Delaware 2 4

Maryland 2 21 37

District of Columbia 6 9

Virginia 2 23 34

North Carolina 2 10 20

South Carolina 3 10 16

Georgia 1 13 18

Florida 1 2

Alabama 10

Mississippi 4 6

Louisiana 10 9

Tennessee 6 8

Kentucky 17 23

Ohio 14 66

Indiana 17

Michigan 2

Illinois 4

Missouri 5

Arkansas 1

Cherokee Nation 1

Total 37 358 802

The present number, however, amounts to about a thousand. Thus the state of New [pg 103] York is mentioned in the table as having 161 newspapers; but a late publication states that there are 193, exclusive of religious journals. New York has 1,913,508 inhabitants. There are about 50 daily newspapers in the United States, two-thirds of which are considered to give a fair profit. The North American colonies, in the year 1720, had only seven newspapers: in 1810, the United States had 359; in 1826, they had 640; in 1830, 1,000, with a population of 13,000,000; so that they have more newspapers than the whole 190 millions of Europe.

In drawing a comparison between the newspapers of the three freest countries, France, England, and the United States, we find, as we have just said, those of the last country to be the most numerous, while some of the French papers have the largest subscription; and the whole establishment of a first-rate London paper is the most complete. Its activity is immense. When Canning sent British troops to Portugal, in 1826, we know that some papers sent reporters with the army. The zeal of the New York papers also deserves to be mentioned, which send out their news-boats, even fifty miles to sea, to board approaching vessels, and obtain the news that they bring. The papers of the large Atlantic cities are also remarkable for their detailed accounts of arrivals, and the particulars of shipping news, interesting to the commercial world, in which they are much more minute than the English. From the immense number of different papers in the United States, it results that the number of subscribers to each is limited, 2,000 being considered a respectable list. One paper, therefore, is not able to unite the talent of many able men, as is the case in France. There men of the first rank in literature or politics occasionally, or at regular periods, contribute articles. In the United States, few papers have more than one editor, who generally writes upon almost all subjects himself. This circumstance necessarily makes the papers less spirited and able than some of the foreign journals, but is attended with this advantage, that no particular set of men is enabled to exercise a predominant influence by means of these periodicals. Their abundance neutralizes their effects. Declamation and sophistry are made comparatively harmless by running in a thousand conflicting currents.

Paper-making.—The manufacture of paper has of late rapidly increased in the United States. According to an estimate in 1829, the whole quantity made in this country amounted to about five to seven millions a year, and employed from ten to eleven thousand persons. Rags are not imported from Italy and Germany to the same amount as formerly, because people here save them more carefully; and the value of the rags, junk, &c., saved annually in the United States, is believed to amount to two millions of dollars. Machines for making paper of any length are much employed in the United States. The quality of American paper has also improved; but, as paper becomes much better by keeping, it is difficult to have it of the best quality in this country, the interest of capital being too high. The paper used here for printing compares very disadvantageously with that of England. Much wrapping paper is now made of straw, and paper for tracing through is prepared in Germany from the poplar tree. A letter of Mr. Brand, formerly a civil officer in Upper Provence, in France (which contains many pine forests), dated Feb. 12, 1830, has been published in the French papers, containing an account of his successful experiments to make coarse paper of the pine tree. The experiments of others have led to the same results. Any of our readers, interested in this subject, can find Mr. Brand's letter in the Courrier Francais of Nov. 27, 1830, a French paper published in New York. In salt-works near Hull, Massachusetts, in which the sea-water is made to flow slowly over sheds of pine, in order to evaporate, the writer found large quantities of a white substance—the fibres of the pine wood dissolved and carried off by the brine—which seemed to require nothing but glue to convert it into paper.

Is one of the most curious creatures of "the watery kingdom." It is popularly termed a fish, though it is, in fact, a worm, belonging to the order termed Mollusca, (Molluscus, soft,) from the body being of a pulpy substance and having no skeleton. It differs in many respects from other animals of its class, particularly with regard to its internal structure, the perfect formation of the viscera, eyes, and even organs of hearing. Moreover, "it has three hearts, two of which are placed at the root of the two branchiae (or gills); they receive the blood from the body, and propel it into the branchiae. The returning veins open into the middle heart, from which the aorta proceeds."7 Of Cuttle-fish there are several species. That represented in the annexed Cut is the common or officinal Cuttle-fish, (Sepia officinalis, Lin). It consists of a soft, pulpy, body, with processes or arms, which are furnished with small holes or suckers, by means of which the animal fixes itself in the manner of cupping-glasses. These holes increase with the age of the animal; and in some species amount to upwards of one thousand. [pg 104] The arms are often torn or nipped off by shell or other fishes, but the animal has the power of speedily reproducing the limbs. By means of the suckers the Cuttle-fish usually affects its locomotion. "It swims at freedom in the bosom of the sea, moving by sudden and irregular jerks, the body being nearly in a perpendicular position, and the head directed downwards and backwards. Some species have a fleshy, muscular fin on each side, by aid of which they accomplish these apparently inconvenient motions; but, at least, an equal number of them are finless, and yet can swim with perhaps little less agility. Lamarck, indeed, denies this, and says that these can only trail themselves along the bottom by means of the suckers. This is probably their usual mode of proceeding; that it is not their only one, we have the positive affirmation of other observers."8 Serviceable as these arms undoubtedly are to the Cuttle-fish, Blumenbach thinks it questionable whether they can be considered as organs of touch, in the more limited sense to which he has confined that term.9

The jaws of the Cuttle-fish, it should be observed, are fixed in the body because there is no head to which they can be articulated. They are of horny substance, and resemble the bill of a parrot. They are in the centre of the under part of the body, surrounded by the arms. By means of these parts, the shell-fish which are taken for food, are completely triturated.

We now come to the most peculiar parts of the structure of the Cuttle-fish, viz. the ear and eye, inasmuch as it is the only animal of its class, in which any thing has hitherto been discovered, at all like an organ of hearing, or that has been shown to possess true eyes.10 The ears consist of two oval cavities, in the cartilaginous ring, to which the large arms of the animal are affixed. In each of these is a small bag, containing a bony substance, and receiving the termination of the nerves, like those of the vestibulum (or cavity in the bone of the ear) in fishes. The nature of the eyes cannot be disputed. "They resemble, on the whole, those of red-blooded animals, particularly fishes; they are at least incomparably more like them than the eyes of any known insects; yet they are distinguished by several extraordinary peculiarities. The front of the eye-ball is covered with a loose membrane instead of a cornea; the iris is composed of a firm substance; and a process projects from the upper margin of the pupil, which gives that membrane a semilunar form."11 The exterior coat or ball is remarkably strong, so as to seem almost calcareous, and is, when taken out, of a brilliant pearl colour; it is worn in some parts of Italy, and in the Grecian islands by way of artificial pearl in necklaces.

Next we may notice the curious provision by which the Cuttle-fish is enabled to elude the pursuit of its enemies in the "vasty deep." This consists of a black, inky fluid, (erroneously supposed to be the bile,) which is contained in a bag beneath the body. The fluid itself is thick, but miscible with water to such a degree, that a very small quantity will colour a vast bulk of water.12 Thus, the comparatively small Cuttle-fish may darken the element about the acute eye of the whale. What omniscience is displayed in this single provision, as well as in the faculty possessed by the Cuttle-fish of reproducing its mutilated arms! All Nature beams with such beneficence, and abounds with such instances of divine love for every creature, however humble: in observing these provisions, how often are we reminded of the benefits conferred by the same omniscience upon our own species. It is thus, by the investigation of natural history, that we are led to the contemplation of the sublimest subjects; thus that man with God himself holds converse.

The "bone" of the Cuttle-fish now claims attention. This is a complicated calcareous plate, lodged in a peculiar cavity of the back, which it materially strengthens. This plate has long been known in the shop of the apothecary under the name of Cuttle-fish bone: an observant reader may have noticed scores of these plates in glasses labelled Os Sepiae. [pg 105] Reduced to powder, they were formerly used as an absorbent, but they are now chiefly sought after for the purpose of polishing the softer metals. It is however improper to call this plate bone, since, in composition, "it is exactly similar to shell, and consists of various membranes, hardened by carbonate of lime, (the principal material of shell,) without the smallest mixture of phosphate of lime,13 (or the chief material of bone.)

Lastly, are the ovaria, or egg-bags of the Cuttle-fish, which are popularly called sea-grapes. The female fish deposits her eggs in numerous clusters, on the stalks of fuci, on corals, about the projecting sides of rocks, or on any other convenient substances. These eggs, which are of the size of small filberts, are of a black colour.

The most remarkable species of Cuttle-fish inhabits the British seas; and, although seldom taken, its bone or plate is cast ashore on different parts of the coast from the south of England to the Zetland Isles. We have picked up scores of these plates and bunches of the egg-bags or grapes, after rough weather on the beach between Worthing and Rottingdean; but we never found a single fish.

The Cuttle-fish was esteemed a delicacy by the ancients, and the moderns equally prize it. Captain Cook speaks highly of a soup he made from it; and the fish is eaten at the present day by the Italians, and by the Greeks, during Lent. We take the most edible species to be the octopodia, or eight-armed, found particularly large in the East Indies and the Gulf of Mexico. The common species here figured, when full-grown, measures about two feet in length, is of a pale blueish brown colour, with the skin marked by numerous dark purple specks.

The Cuttle-fish is described by some naturalists, as naked or shell-less. It is often found attached to the shell of the Paper Nautilus, which it is said to use as a sail. It is, however, very doubtful whether the Cuttle-fish has a shell of its own. There is a controversy upon the subject. Aristotle, and our contemporary, Home, maintain it to be parasitical: Cuvier and Ferrusac, non-parasitical; but the curious reader will find the pro and con.—the majority and minority—in the Magazine of Natural History, vol. iii. p. 535.

[Captain Skinner, in his Excursions in India, makes the following sensible observations on the tyranny over servants in India:]

There are throughout the mountains many of the sacred shrubs of the Hindoos, which give great delight, as my servants fall in with them. They pick the leaves; and running with them to me, cry, "See, sir, see, our holy plants are here!" and congratulate each other on having found some indication of a better land than they are generally inclined to consider the country of the Pariahs. The happiness these simple remembrances shed over the whole party is so enlivening, that every distress and fatigue seems to be forgotten. When we behold a servant approaching with a sprig of the Dona in his hand, we hail it as the olive-branch, that denotes peace and good-will for the rest of the day, if, as must sometimes be the case, they have been in any way interrupted.

Even these little incidents speak so warmly in favour of the Hindoo disposition, that, in spite of much that may be uncongenial to an European in their character, they cannot fail to inspire him with esteem, if not affection. I wish that many of my countrymen would learn to believe that the natives are endowed with feelings, and surely they may gather such an inference from many a similar trait to the one I have related. Hardness of heart can never be allied to artless simplicity: that mind must possess a higher degree of sensibility and refinement, that can unlock its long-confined recollections by so light a spring as a wild flower.

I have often witnessed, with wonder and sorrow, an English gentleman stoop to the basest tyranny over his servants, without even the poor excuse of anger, and frequently from no other reason than because he could not understand their language. The question, from the answer being unintelligible, is instantly followed by a blow. Such scenes are becoming more rare, and indeed are seldom acted but by the younger members of society; they are too frequent notwithstanding: and should any thing that has fallen from me here, induce the cruelly-disposed to reflect a little upon the impropriety and mischief of their conduct, when about to raise the hand against a native, and save one stripe to the passive people who are so much at the mercy of their masters' tempers, I shall indeed be proud.

[Again, speaking of the condition of servants, Captain Skinner remarks—]

It is impossible to view some members of the despised class without sorrow and pity, particularly those who are attached, in the lowest offices, to the establishments of the [pg 106] Europeans. They are the most melancholy race of beings, always alone, and apparently unhappy: they are scouted from the presence even of their fellow-servants. None but the mind of a poet could imagine such outcasts venturing to raise their thoughts to the beauty of a Brahmin's daughter; and a touching tale in such creative fancy, no doubt, it would make, for, from their outward appearances, I do not perceive why they should not be endowed with minds as sensitive at least as those of the castes above them. There are among them some very stout and handsome men; and it is ridiculous to see sometimes all their strength devoted to the charge of a sickly puppy;—to take care of dogs being their principal occupation!

Our attention has been drawn to the above passage in Captain Skinner's work, by its ready illustration of the views and conclusions of the late Dr. Knox, in his invaluable Spirit of Despotism, Section 2, "Oriental manners, and the ideas imbibed in youth, both in the East and West Indies, favourable to the spirit of despotism." How forcibly applicable, on the present occasion, is the following extract:—"from the intercourse of England with the East and West Indies, it is to be feared that something of a more servile spirit has been derived than was known among those who established the free constitutions of Europe, and than would have been adopted, or patiently borne, in ages of virtuous simplicity. A very numerous part of our countrymen spend their most susceptible age in those countries, where despotic manners remarkably prevail. They are themselves, when invested with office, treated by the natives with an idolatrous degree of reverence, which teaches them to expect a similar submission to their will, on their return to their own country. They have been accustomed to look up to personages greatly their superiors in rank and riches, with awe; and to look down on their inferiors in property with supreme contempt, as slaves of their will and ministers of their luxury. Equal laws and equal liberty at home appear to them saucy claims of the poor and the vulgar, which tend to divest riches of one of the greatest charms, over-bearing dominion. We do, indeed, import gorgeous silks and luscious sweets from the Indies, but we import, at the same time, the spirit of despotism, which adds deformity to the purple robe, and bitterness to the honied beverage." "That Oriental manners are unfavourable to liberty, is, I believe, universally conceded. The natives of the East Indies entertain not the idea of independence. They treat the Europeans, who go among them to acquire their riches, with a respect similar to the abject submission which they pay to their native despots. Young men, who in England scarcely possessed the rank of the gentry, are waited upon in India, with more attentive servility than is paid or required in many courts of Europe. Kings of England seldom assume the state enjoyed by an East India governor, or even by subordinate officers. Enriched at an early age, the adventurer returns to England. His property admits him to the higher circles of fashionable life. He aims at rivalling or excelling all the old nobility in the splendour of his mansions, the finery of his carriages, the number of his liveried train, the profusion of his tables, in every unmanly indulgence which an empty vanity can covet, and a full purse procure. Such a man, when he looks from the window of his superb mansion, and sees the people pass, cannot endure the idea, that they are of as much consequence as himself in the eye of the law; and that he dares not insult or oppress the unfortunate being who rakes his kennel or sweeps his chimney."

It is well known, that during the revolutionary troubles of France, not only all the churches were closed, but the Catholic and Protestant worship entirely forbidden; and, after the constitution of 1795, it was at the hazard of one's life that either the mass was heard, or any religious duty performed. It is evident that Robespierre, who unquestionably had a design which is now generally understood, was desirous, on the day of the fête of the Supreme Being, to bring back public opinion to the worship of the Deity. Eight months before, we had seen the Bishop of Paris, accompanied by his clergy, appear voluntarily at the bar of the Convention, to abjure the Christian faith and the Catholic religion. But it is not as generally known, that at that period Robespierre was not omnipotent, and could not carry his desires into effect. Numerous factions then disputed with him the supreme authority. It was not till the end of 1793, and the beginning of 1794, that his power was so completely established that he could venture to act up to his intentions.

Robespierre was then desirous to establish the worship of the Supreme Being, and the belief of the immortality of the soul. He felt that irreligion is the soul of anarchy, and it was not anarchy but despotism which he desired; and yet the very day after that magnificent fête in honour of the Supreme Being, a man of the highest celebrity in science, and as distinguished for virtue and probity as philosophic genius, Lavoisier, was led out to the scaffold. On the day following that, Madame Elizabeth, that Princess whom the executioners could not guillotine, till they had turned aside their eyes from the sight of her angelic visage, stained the same axe with her blood!—And [pg 107] a month after, Robespierre, who wished to restore order for his own purposes—who wished to still the bloody waves which for years had inundated the state, felt that all his efforts would be in vain if the masses who supported his power were not restrained and directed, because without order nothing but ravages and destruction can prevail. To ensure the government of the masses, it was indispensable that morality, religion, and belief should be established—and, to affect the multitude, that religion should be clothed in external forms. "My friend," said Voltaire, to the atheist Damilaville, "after you have supped on well-dressed partridges, drunk your sparkling champaigne, and slept on cushions of down in the arms of your mistress, I have no fear of you, though you do not believe in God.—-But if you are perishing of hunger, and I meet you in the corner of a wood, I would rather dispense with your company." But when Robespierre wished to bring back to something like discipline the crew of the vessel which was fast driving on the breakers, he found the thing was not so easy as he imagined. To destroy is easy—to rebuild is the difficulty. He was omnipotent to do evil; but the day that he gave the first sign of a disposition to return to order, the hands which he himself had stained with blood, marked his forehead with the fatal sign of destruction.

The great audibility of sounds during the night is a phenomenon of considerable interest, and one which had been observed even by the ancients. In crowded cities or in their vicinity, the effect was generally ascribed to the rest of animated beings, while in localities where such an explanation was inapplicable, it was supposed to arise from a favourable direction of the prevailing wind. Baron Humboldt was particularly struck with this phenomenon when he first heard the rushing of the great cataracts of the Orinoco in the plain which surrounds the mission of the Apures. These sounds he regarded as three times louder during the night than during the day. Some authors ascribed this fact to the cessation of the humming of insects, the singing of birds, and the action of the wind on the leaves of the trees, but M. Humboldt justly maintains that this cannot be the cause of it on the Orinoco, where the buzz of insects is much louder in the night than in the day, and where the breeze never rises till after sunset. Hence he was led to ascribe the phenomenon to the perfect transparency and uniform density of the air, which can exist only at night after the heat of the ground has been uniformly diffused through the atmosphere. When the rays of the sun have been beating on the ground during the day, currents of hot air of different temperatures, and consequently of different densities, are constantly ascending from the ground and mixing with the cold air above. The air thus ceases to be a homogeneous medium, and every person must have observed the effects of it upon objects seen through it which are very indistinctly visible, and have a tremulous motion, as if they were "dancing in the air." The very same effect is perceived when we look at objects through spirits and water that are not perfectly mixed, or when we view distant objects over a red hot poker or over a flame. In all these cases the light suffers refraction in passing from a medium of one density into a medium of a different density, and the refracted rays are constantly changing their direction as the different currents rise in succession. Analogous effects are produced when sound passes through a mixed medium, whether it consists of two different mediums or of one medium where portions of it have different densities. As sound moves with different velocities through media of different densities, the wave which produces the sound will be partly reflected in passing from one medium to the other, and the direction of the transmitted wave changed; and hence in passing through such media different portions of the wave will reach the ear at different times, and thus destroy the sharpness and distinctness of the sound. This may be proved by many striking facts. If we put a bell in a receiver containing a mixture of hydrogen gas and atmospheric air, the sound of the bell can scarcely be heard. During a shower of rain or of snow, noises are greatly deadened, and when sound is transmitted along an iron wire or an iron pipe of sufficient length, we actually hear two sounds, one transmitted more rapidly through the solid, and the other more slowly through the air. The same property is well illustrated by an elegant and easily repeated experiment of Chladni's. When sparkling champagne is poured into a tall glass till it is half full, the glass loses its power of ringing by a stroke upon its edge, and emits only a disagreeable and a puffy sound. This effect will continue while the wine is filled with bubbles of air, or as long as the effervescence lasts; but when the effervescence begins to subside, the sound becomes clearer and clearer, and the glass rings as usual when the air-bubbles have vanished. If we reproduce the effervescence by stirring the champagne with a piece of bread the glass will again cease to ring. The same experiment will succeed with other effervescing fluids.—Sir David Brewster.

No man is so insignificant as to be sure his example can do no hurt.

Paddy Fooshane kept a shebeen house at Barleymount Cross, in which he sold whisky—from which his Majesty did not derive any large portion of his revenues—ale, and provisions. One evening a number of friends, returning from a funeral—-all neighbours too—stopt at his house, "because they were in grief," to drink a drop. There was Andy Agar, a stout, rattling fellow, the natural son of a gentleman residing near there; Jack Shea, who was afterwards transported for running away with Biddy Lawlor; Tim Cournane, who, by reason of being on his keeping, was privileged to carry a gun; Owen Connor, a march-of-intellect man, who wished to enlighten proctors by making them swallow their processes; and a number of other "good boys." The night began to "rain cats and dogs," and there was no stirring out; so the cards were called for, a roaring fire was made down, and the whisky and ale began to flow. After due observation, and several experiments, a space large enough for the big table, and free from the drop down, was discovered. Here six persons, including Andy, Jack, Tim—with his gun between his legs—and Owen, sat to play for a pig's head, of which the living owner, in the parlour below, testified, by frequent grunts, his displeasure at this unceremonious disposal of his property.

Card-playing is very thirsty, and the boys were anxious to keep out the wet; so that long before the pig's head was decided, a messenger had been dispatched several times to Killarney, a distance of four English miles, for a pint of whisky each time. The ale also went merrily round, until most of the men were quite stupid, their faces swoln, and their eyes red and heavy. The contest at length was decided; but a quarrel about the skill of the respective parties succeeded, and threatened broken heads at one time. At last Jack Shea swore they must have something to eat;——him but he was starved with drink, and he must get some rashers somewhere or other. Every one declared the same; and Paddy was ordered to cook some griskins forthwith. Paddy was completely nonplussed:—all the provisions were gone, and yet his guests were not to be trifled with. He made a hundred excuses—"'Twas late—'twas dry now—and there was nothing in the house; sure they ate and drank enough." But all in vain. The ould sinner was threatened with instant death if he delayed. So Paddy called a council of war in the parlour, consisting of his wife and himself.

"Agrah, Jillen, agrah, what will we do with these? Is there any meat in the tub? Where is the tongue? If it was yours, Jillen, we'd give them enough of it; but I mane the cow's." (aside.)

"Sure the proctors got the tongue ere yesterday, and you know there an't a bit in the tub. Oh the murtherin villains! and I'll engage 'twill be no good for us, after all my white bread and the whisky. That it may pison 'em!"

"Amen! Jillen; but don't curse them. After all, where's the meat? I'm sure that Andy will kill me if we don't make it out any how;—and he hasn't a penny to pay for it. You could drive the mail coach, Jillen, through his breeches pocket without jolting over a ha'penny. Coming, coming; d'ye hear 'em?"

"Oh, they'll murther us. Sure if we had any of the tripe I sent yesterday to the gauger."

"Eh! What's that you say? I declare to God here's Andy getting up. We must do something. Thonom an dhiaoul, I have it. Jillen run and bring me the leather breeches; run woman, alive! Where's the block and the hatchet? Go up and tell 'em you're putting down the pot."

Jillen pacified the uproar in the kitchen by loud promises, and returned to Paddy. The use of the leather breeches passed her comprehension; but Paddy actually took up the leather breeches, tore away the lining with great care, chopped the leather with the hatchet on the block, and put it into the pot as tripes. Considering the situation in which Andy and his friends were, and the appetite of the Irish peasantry for meat in any shape—"a bone" being their summum bonum—the risk was very little. If discovered, however, Paddy's safety was much worse than doubtful, as no people in the world have a greater horror of any unusual food. One of the most deadly modes of revenge they can employ is to give an enemy dog's or cat's flesh; and there have been instances where the persons who have eaten it, on being informed of the fact, have gone mad. But Paddy's habit of practical jokes, from which nothing could wean him, and his anger at their conduct, along with the fear he was in did not allow him to hesitate a moment. Jillen remonstrated in vain. "Hould your tongue, you foolish woman. They're all as blind as the pig there. They'll never find it out. Bad luck to 'em too, my leather breeches! that I gave a pound note and a hog for in Cork. See how nothing else would satisfy 'em!" The meat at length was ready. Paddy drowned it in butter, threw out the potatoes on the table, and served it up smoking hot with the greatest gravity.

"By ——," says Jack Shea, "that's fine stuff! How a man would dig a trench after that."

"I'll take a priest's oath," answered Tim Cohill, the most irritable of men, but whose [pg 109] temper was something softened by the rich steam;—

"Yet, Tim, what's a priest's oath? I never heard that."

"Why, sure, every one knows you didn't ever hear of anything of good."

"I say you lie, Tim, you rascal."

Tim was on his legs in a few moments, and a general battle was about to begin; but the appetite was too strong, and the quarrel was settled; Tim having been appeased by being allowed to explain a priest's oath. According to him, a priest's oath was this:—He was surrounded by books, which were gradually piled up until they reached his lips. He then kissed the uppermost, and swore by all to the bottom. As soon as the admiration excited by his explanation, in those who were capable of hearing Tim, had ceased, all fell to work; and certainly, if the tripes had been of ordinary texture, drunk as was the party, they would soon have disappeared. After gnawing at them for some time, "Well," says Owen Connor, "that I mightn't!—but these are the quarest tripes I ever eat. It must be she was very ould."

"By ——," says Andy, taking a piece from his mouth to which he had been paying his addresses for the last half hour, "I'd as soon be eating leather. She was a bull, man; I can't find the soft end at all of it."

"And that's true for you, Andy," said the man of the gun; "and 'tis the greatest shame they hadn't a bull-bait to make him tinder. Paddy, was it from Jack Clifford's bull you got 'em? They'd do for wadding, they're so tough."

"I'll tell you, Tim, where I got them—'twas out of Lord Shannon's great cow at Cork, the great fat cow that the Lord Mayor bought for the Lord Lieutenant—Asda churp naur hagushch."14

"Amen, I pray God! Paddy. Out of Lord Shandon's cow? near the steeple, I suppose; the great cow that couldn't walk with tallow. By ——, these are fine tripes. They'll make a man very strong. Andy, give me two or three libbhers more of 'em."

"Well, see that! out of Lord Shandon's cow: I wonder what they gave her, Paddy. That I mightn't!—but these would eat a pit of potatoes. Any how, they're good for the teeth. Paddy, what's the reason they send all the good mate from Cork to the Blacks?"

But before Paddy could answer this question, Andy, who had been endeavouring to help Tim, uttered a loud "Thonom an dhiaoul! what's this? Isn't this flannel?" The fact was, he had found a piece of the lining, which Paddy, in his hurry, had not removed; and all was confusion. Every eye was turned to Paddy; but with wonderful quickness he said "'Tis the book tripe, agragal, don't you see?"—and actually persuaded them to it.

"Well, any how," says Tim, "it had the taste of wool."

"May this choke me," says Jack Shea, "if I didn't think that 'twas a piece of a leather breeches when I saw Andy chawing it."

This was a shot between wind and water to Paddy. His self-possession was nearly altogether lost, and he could do no more than turn it off by a faint laugh. But it jarred most unpleasantly on Andy's nerves. After looking at Paddy for some time with a very ominous look, he said, "Yirroo Pandhrig of the tricks, if I thought you were going on with any work here, my soul and my guts to the devil if I would not cut you into garters. By the vestment I'd make a furhurmeen of you."

"Is it I, Andy? That the hands may fall off me!"

But Tim Cohill made a most seasonable diversion. "Andy, when you die, you'll be the death of one fool, any how. What do you know that wasn't ever in Cork itself about tripes. I never ate such mate in my life; and 'twould be good for every poor man in the County of Kerry if he had a tub of it."

Tim's tone of authority, and the character he had got for learning, silenced every doubt, and all laid siege to the tripes again. But after some time, Andy was observed gazing with the most astonished curiosity into the plate before him. His eyes were rivetted on something; at last he touched it with his knife, arid exclaimed, "Kirhappa, dar dhia!"—[A button by G—.]

"What's that you say?" burst from all! and every one rose in the best manner he could, to learn the meaning of the button.

"Oh, the villain of the world!" roared Andy, "I'm pisoned! Where's the pike? For God's sake Jack, run for the priest, or I'm a dead man with the breeches. Where is he?—yeer bloods won't ye catch him, and I pisoned?"

The fact was, Andy had met one of the knee-buttons sewed into a piece of the tripe, and it was impossible for him to fail discovering the cheat. The rage, however, was not confined to Andy. As soon as it was understood what had been done, there was an universal rush for Paddy and Jillen; but Paddy was much too cunning to be caught, after the narrow escape he had of it before. The moment after the discovery of the lining, that he could do so without suspicion, he stole from the table, left the house, and hid himself. Jillen did the same; and nothing remained for the eaters, to vent their rage, but breaking every thing in the cabin; which was done in the utmost fury. Andy, however, continued watching for Paddy with a gun, a whole month after. He might be [pg 110] seen prowling along the ditches near the shebeen-house, waiting for a shot at him. Not that he would have scrupled to enter it, were he likely to find Paddy there; but the latter was completely on the shuchraun, and never visited his cabin except by stealth. It was in one of those visits that Andy hoped to catch him.

One of our first rides with Lord Byron was to Nervi, a village on the sea-coast, most romantically situated, and each turn of the road presenting various and beautiful prospects. They were all familiar to him, and he failed not to point them out, but in very sober terms, never allowing any thing like enthusiasm in his expressions, though many of the views might have excited it.

His appearance on horseback was not advantageous, and he seemed aware of it, for he made many excuses for his dress and equestrian appointments. His horse was literally covered with various trappings, in the way of cavesons, martingales, and Heaven knows how many other (to me) unknown inventions. The saddle was à la Hussarde with holsters, in which he always carried pistols. His dress consisted of a nankeen jacket and trousers, which appeared to have shrunk from washing; the jacket embroidered in the same colour, and with three rows of buttons; the waist very short, the back very narrow, and the sleeves set in as they used to be ten or fifteen years before; a black stock, very narrow; a dark-blue velvet cap with a shade, and a very rich gold band and large gold tassel at the crown; nankeen gaiters, and a pair of blue spectacles, completed his costume, which was any thing but becoming. This was his general dress of a morning for riding, but I have seen it changed for a green tartan plaid jacket. He did not ride well, which surprised us, as, from the frequent allusions to horsemanship in his works, we expected to find him almost a Nimrod, It was evident that he had pretensions on this point, though he certainly was what I should call a timid rider. When his horse made a false step, which was not unfrequent, he seemed discomposed; and when we came to any bad part of the road, he immediately checked his course and walked his horse very slowly, though there really was nothing to make even a lady nervous. Finding that I could perfectly manage (or what he called bully) a very highly-dressed horse that I daily rode, he became extremely anxious to buy it; asked me a thousand questions as to how I had acquired such a perfect command of it, &c. &c. and entreated, as the greatest favour, that I would resign it to him as a charger to take to Greece, declaring he never would part with it, &c. As I was by no means a bold rider, we were rather amused at observing Lord Byron's opinion of my courage; and as he seemed so anxious for the horse, I agreed to let him have it when he was to embark. From this time he paid particular attention to the movements of poor Mameluke (the name of the horse), and said he should now feel confidence in action with so steady a charger.

April—. Lord Byron dined with us today. During dinner he was as usual gay, spoke in terms of the warmest commendation of Sir Walter Scott, not only as an author, but as a man, and dwelt with apparent delight on his novels, declaring that he had read and re-read them over and over again, and always with increased pleasure. He said that he quite equalled, nay, in his opinion, surpassed Cervantes. In talking of Sir Walter's private character, goodness of heart, &c., Lord Byron became more animated than I had ever seen him; his colour changed from its general pallid tint to a more lively hue, and his eyes became humid: never had he appeared to such advantage, and it might easily be seen that every expression he uttered proceeded from his heart. Poor Byron!—for poor he is even with all his genius, rank, and wealth—had he lived more with men like Scott, whose openness of character and steady principle had convinced him that they were in earnest in their goodness, and not making believe, (as he always suspects good people to be,) his life might be different and happier! Byron is so acute an observer that nothing escapes him; all the shades of selfishness and vanity are exposed to his searching glance, and the misfortune is, (and a serious one it is to him,) that when he finds these, and alas! they are to be found on every side, they disgust and prevent his giving credit to the many good qualities that often accompany them. He declares he can sooner pardon crimes, because they proceed from the passions, than these minor vices, that spring from egotism and self-conceit. We had a long argument this evening on the subject, which ended, like most arguments, by leaving both of the same opinion as when it commenced. I endeavoured to prove that crimes were not only injurious to the perpetrators, but often ruinous to the innocent, and productive of misery to friends and relations, whereas selfishness and vanity carried with them their own punishment, the first depriving the person of all sympathy, and the second exposing him to ridicule which to the vain is a heavy punishment, but that their effects were not destructive to society as are crimes.

He laughed when I told him that having heard him so often declaim against vanity, and detect it so often in his friends, I began to suspect he knew the malady by having had it himself, and that I had observed through life, that those persons who had the most [pg 111] vanity were the most severe against that failing in their friends. He wished to impress upon me that he was not vain, and gave various proofs to establish this; but I produced against him his boasts of swimming, his evident desire of being considered more un homme de societe than a poet, and other little examples, when he laughingly pleaded guilty, and promised to be more merciful towards his friends.

Byron attempted to be gay, but the effort was not successful, and he wished us good night with a trepidation of manner that marked his feelings. And this is the man that I have heard considered unfeeling! How often are our best qualities turned against us, and made the instruments for wounding us in the most vulnerable part, until, ashamed of betraying our susceptibility, we affect an insensibility we are far from possessing, and, while we deceive others, nourish in secret the feelings that prey only on our own hearts!

Canary Birds.—In Germany and the Tyrol, from whence the rest of Europe is principally supplied with Canary birds, the apparatus for breeding Canaries is both large and expensive. A capacious building is erected for them, with a square space at each end, and holes communicating with these spaces. In these outlets are planted such trees as the birds prefer. The bottom is strewed with sand, on which are cast rapeseed, chickweed, and such other food as they like. Throughout the inner compartment, which is kept dark, are placed bowers for the birds to build in, care being taken that the breeding birds are guarded from the intrusion of the rest. Four Tyrolese usually take over to England about sixteen hundred of these birds; and though they carry them on their backs nearly a thousand miles, and pay twenty pounds for them originally, they can sell them at 5s. each.

Braithwaite's Steam Fire Engine—will deliver about 9,000 gallons of water per hour to an elevation of 90 feet. The time of getting the machine into action, from the moment of igniting the fuel, (the water being cold,) is 18 minutes. As soon as an alarm is given, the fire is kindled, and the bellows, attached to the engine, are worked by hand. By the time the horses are harnessed in, the fuel is thoroughly ignited, and the bellows are then worked by the motion of the wheels of the engine. By the time of arriving at the fire, preparing the hoses, &c. the steam is ready.

Fisher, bishop of Rochester, was accustomed to style his church his wife, declaring that he would never exchange her for one that was richer. He was a zealous adherent of Pope Paul III. who created him a cardinal. The king, Henry VIII., on learning that Fisher would not refuse the dignity, exclaimed, in a passion, "Yea! is he so lusty? Well, let the pope send him a hat when he will. Mother of God! he shall wear it on his shoulders, for I will leave him never a head to set it on."

Flax is not uncommon in the greenhouses about Philadelphia, but we have not heard of any experiments with it in the open air.—Encyclopaedia Americana.

The Schoolmaster wanted in the East.—Mr. Madden, in his travels in Turkey, Egypt, Nubia, and Palestine, says:—"In all my travels, I could only meet one woman who could read and write, and that was in Damietta; she was a Levantine Christian, and her peculiar talent was looked upon as something superhuman."

La Fontaine had but one son, whom, at the age of 14, he placed in the hands of Harlay, archbishop of Paris, who promised to provide for him. After a long absence, La Fontaine met this youth at the house of a friend, and being pleased with his conversation, was told that it was his own son. "Ah," said he, "I am very glad of it."

Universal Genius.—Rivernois thus describes the character of Fontenelle: "When Fontenelle appeared on the field, all the prizes were already distributed, all the palms already gathered: the prize of universality alone remained, Fontenelle determined to attempt it, and he was successful. He is not only a metaphysician with Malebranche, a natural philosopher with Newton, a legislator with Peter the Great, a statesman with D'Argenson; he is everything with everybody."

Forest Schools.—There are a number of forest academies in Germany, particularly in the small states of central Germany, in the Hartz, Thuringia, &c. The principal branches taught in them are the following:—forest botany, mineralogy, zoology, chemistry; by which the learner is taught the natural history of forests, and the mutual relations, &c. of the different kingdoms of nature. He is also instructed in the care and chase of game, and in the surveying and cultivation of forests, so as to understand the mode of raising all kinds of wood, and supplying a new growth as fast as the old is taken away. The pupil is too instructed in the administration of the forest taxes and police, and all that relates to forests considered as a branch of revenue.

The Weather.—Meteorological journals are now given in most magazines. The first statement of this kind was communicated by Dr. Fothergill to the Gentleman's Magazine, and consisted of a monthly account of the weather and diseases of London. The latter [pg 112] information is now monopolized by the parish-clerks.

Goethe.—The wife of a Silesian peasant, being obliged to go to Saxony, and hearing that she had travelled (on foot) more than half the distance to Goethe's residence, whose works she had read with the liveliest interest, continued her journey to Weimar for the sake of seeing him. Goethe declared that the true character of his works had never been better understood than by this woman. He gave her his portrait.

Liverpool and Manchester Railway.—The Company has reported the following result:

Passengers entered in the Company's

books during the half-year

ending June 30, 1831 £188,726

Ditto, ditto, ending

December 31, 1831 256,321

Increase £67,595

Being upwards of 33 per cent. increase of the first six months of the year, and upwards of 135 per cent. increase on the travellers between the two towns during the corresponding months, previously to opening the railway.—Gordon, on Steam Carriages.

Caliga.—This was the name of the Roman soldier's shoe, made in the sandal fashion. The sole was of wood, and stuck full of nails. Caius Caesar Caligula, the fourth Roman Emperor, the son of Germanicus and Agrippina, derived his surname from "Caliga," as having been born in the army, and afterwards bred up in the habit of a common soldier; he wore this military shoe in conformity to those of the common soldiers, with a view of engaging their affections. The caliga was the badge, or symbol of a soldier; whence to take away the caliga and belt, imported a dismissal or cashiering. P.T.W.

The Damary Oak-tree.—At Blandford Forum, Dorsetshire, stood the famous Damary Oak, which was rooted up for firing in 1755. It measured 75 feet high, and the branches extended 72 feet; the trunk at the bottom was 68 feet in circumference, and 23 feet in diameter. It had a cavity in its trunk 15 feet wide. Ale was sold in it till after the Restoration; and when the town was burnt down in 1731, it served as an abode for one family.—Family Topographer, vol. ii.

Brent Tor Church, Devonshire, situate upon a rock.—On Brent Tor is a church, in which is appositely inscribed from Scripture, "Upon this rock will I build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it." It is said that the parishioners make weekly atonement for their sins, for they cannot go to the church without the previous penance of climbing the steep; and the pastor is frequently obliged to humble himself upon his hands and knees before he can reach the house of prayer. Tradition says it was erected by a merchant to commemorate his escape from shipwreck on the coast, in consequence of this Tor serving as a guide to the pilot. There is not sufficient earth to bury the dead. At the foot of the Tor resided, in 1809, Sarah Williams, aged 109 years. She never lived further out of the parish of Brent Tor, than the adjoining one: she had had twelve children, and a few years before her death cut five new teeth.—Ibid.

The Dairyman's Daughter.—In Arreton churchyard, Isle of Wight, is a tombstone, erected in 1822, by subscription, to mark the grave of Elizabeth Wallbridge, the humble individual whose story of piety and virtue, written by the Rev. Leigh Richmond, under the title of the "Dairyman's Daughter," has attained an almost unexampled circulation. Her cottage at Branston, about a mile distant, is much visited.—Ibid.

Singular distribution of common land in Somersetshire.—In the parishes of Congresbury and Puxton were two large pieces of common land, called East and West Dolemoors (from the Saxon word dol, a portion or share,) which were occupied till within these few years in the following manner:—-The land was divided into single acres, each bearing a peculiar mark, cut in the turf, such as a horn, an ox, a horse, a cross, an oven, &c. On the Saturday before Old Midsummer Day, the several proprietors of contiguous estates, or their tenants, assembled on these commons, with a number of apples marked with similar figures, which were distributed by a boy to each of the commoners from a bag. At the close of the distribution, each person repaired to the allotment with the figure corresponding to the one upon his apple, and took possession of it for the ensuing year. Four acres were reserved to pay the expenses of an entertainment at the house of the overseer of the Dolemoors, where the evening was spent in festivity.—Ibid.

Anna Maria, Countess of Shrewsbury.—At Avington Park, in Hampshire, resided the notorious and infamous Anna-Maria, Countess of Shrewsbury, who held the horse of the Duke of Buckingham while he fought and killed her husband. Charles II frequently made it the scene of his licentious pleasures; and the old green-house is said to have been the apartment in which the royal sensualist was entertained.—Ibid.

Footnote 1: (return)It may be as well here to quote the formation of Cataracts and Cascades, from Maltebrun's valuable System of Universal Geography. "It is only the sloping of the land which can at first cause water to flow; but an impulse having been once communicated to the mass, the pressure alone of the water will keep it in motion, even if there were no declivity at all. Many great rivers, in fact, flow with an almost interruptible declivity. Rivers which descend from primitive mountains into secondary lands, often form cascades and cataracts. Such are the cataracts of the Nile, of the Ganges, and some other great rivers, which, according to Desmarest, evidently mark the limits of the ancient land. Cataracts are also formed by lakes: of this description are the celebrated Falls of the Niagara; but the most picturesque falls are those of rapid rivers, bordered by trees and precipitous rocks. Sometimes we see a body of water, which, before it arrives at the bottom, is broken and dissipated into showers, like the Staubbach, (see Mirror, vol. xiv. p. 385.); sometimes it forms a watery arch, projected from a rampart of rock, under which the traveller may pass dryshod, as the "falling spring" of Virginia; in one place, in a granite district, we see the Trolhetta, and the Rhine not far from its source, urge on their foaming billows among the pointed rocks; in another, amidst lands of a calcareous formation, we see the Czettina and the Kerka, rolling down from terrace to terrace, and presenting sometimes a sheet, and sometimes a wall, of water. Some magnificent cascades have been formed, at least in part, by the hands of man: the cascades of Velino, near Terni, have been attributed to Pope Clement VIII.; other cataracts, like those of Tunguska, in Siberia, have gradually lost their elevation by the wearing away of the rocks, and have now only a rapid descent."—Maltebrun, vol. i.

Footnote 5: (return)A Collection of Poems of the Sixteenth Century.—Communicated by J.F., of Gray's Inn. We thank our Correspondent for the present, and shall be happy to receive further specimens from the same source.