Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 395, October 24, 1829

Author: Various

Release date: February 1, 2004 [eBook #11222]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, David Garcia and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

| Vol. XIV. No. 395.] | SATURDAY, OCTOBER 24, 1829. | [PRICE 2d. |

Four centuries since the Merchants of London could not boast of a public Exchange. They then assembled to transact business in Lombard-street, among the Lombard Jews, from whom the street derives its name, and who were then the bankers of all Europe. Here too they probably kept their benches or banks, as they were wont to do in the market-places of the continent, for transacting pecuniary matters; and thus drew around them all those of whose various pursuits money is the common medium.

At length, in 1534, Sir R. Gresham, who was agent for Henry the Eighth at Antwerp, and had been struck with the advantages attending the Bourse, or Exchange, of that city, prevailed upon his Royal Master to send a letter to the Mayor and Commonalty of London, recommending them to erect a similar building on their manor of Leadenhall. The Court of Common Council, however, were of opinion that such a removal of the seat of business would be impracticable, and the scheme was therefore dropped; but in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, Sir Thomas Gresham, who succeeded to the Antwerp agency, happily accomplished what had been denied to the hopes of his father. In 1564 Sir Thomas proposed to the Corporation—"That if the City would give him a piece of ground, in a commodious spot, he would erect an Exchange at his own expense, with large and covered walks, wherein the merchants might assemble and transact business at all seasons, without interruption from the weather, or impediments of any kind." The Corporation met the proposal with a spirit of equal liberality; and in 1566 various buildings, houses, tenements, &c. in Cornhill, were purchased for rather more than £3,530, and the materials re-sold for £478, on condition of pulling them down and carrying them away.—The ground plot was then levelled at the charge of the City, and possession given to Sir Thomas, who in the deed is styled, "Agent to the Queen's Highness," and who laid the foundation of the new Exchange on the 7th of June following; and the whole was covered in before November 1567.

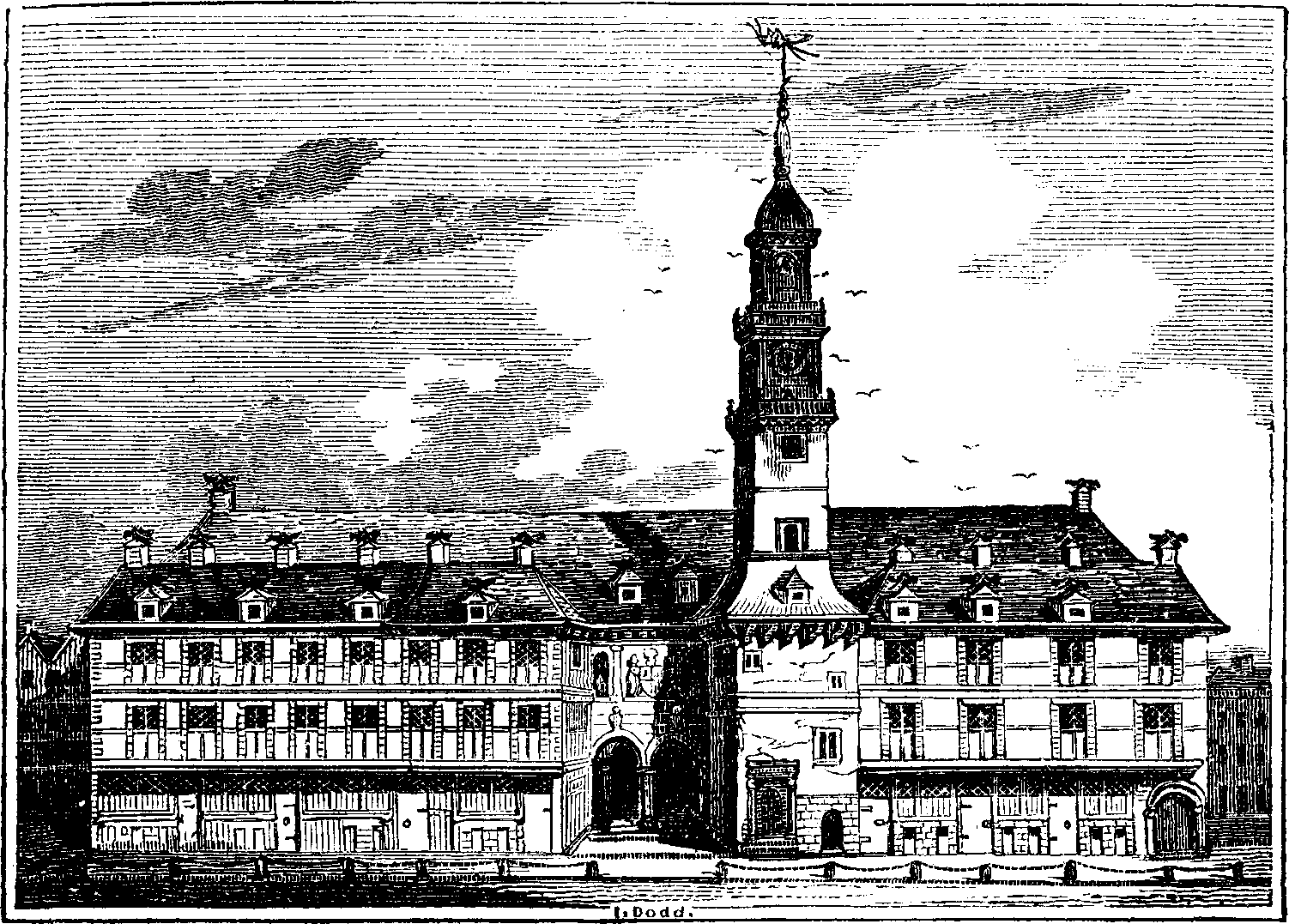

The plan adopted by Sir Thomas, in [pg 258] the formation of his building, was similar to the one at Antwerp. An open area was inclosed by a quadrangle of lofty stone-buildings, with a colonnade as at present, supported, by marble columns of the Doric order, over which ran a cornice, with Ionic pilasters above, having niches between, containing statues of the English Sovereigns. The entrances were from Cornhill and Broad-street. Over the first, between two Ionic three-quarter columns, were the Royal Arms, and on either side were those of the City and Sir Thomas; on the north side, but not exactly in the centre, rose a Corinthian pillar to about the same height as the tower in front surmounted with the grasshopper. In every other respect it was similar to the south, of which the previous engraving is a view.

Over the arcade were shops, to which you ascended by two staircases, north and south. Above stairs were about1 one hundred shops, varying from 2-3/4 feet to 20 in breadth and forming a sort of bazaar, then called the Pawne. These shops, for the first two or three years did not answer the expectation of the founder, for such was the force of habit, that the merchants, notwithstanding all the inconveniences attending Lombard-street, could not be prevailed upon to avail themselves of the new mart.

The building had been opened two or three years, when the Queen signified her intention of paying it a visit of inspection; but so many of the shops still remained unoccupied, that Sir Thomas found it necessary to go round to the shopkeepers, and beseech them "to furnish and adorne it with wares and wax lights, in as many shoppes as they either could or woulde, and they should have all those so furnished rent-free for that yeare."—Stowe.

Her Majesty on the day fixed (Jan. 23, 1570), having dined with the founder, at his house in Bishopsgate-street, returned by the way of Cornhill, and entered on the south side; and having viewed it, she expressed herself much pleased; and, with the national spirit which so eminently distinguished her, commanded that, instead of the foreign name Bourse, by which the citizens had begun to call it, it should be styled, in plain English—The Royal Exchange—which was proclaimed by sound of trumpet:—

"Proclaim through every high street of the city,

This place be no longer called a Burse;

But since the building's stately, fair, and strange,

Be it for ever called—The Royal Exchange!"2

The building could not have been very substantial, for by an entry in the Wardbook of Cornhill ward, we find that in 1581, not fourteen years after its completion, some of the arches of the arcade were in an unsafe condition, and the lives of the merchants passing under were in danger. And further—in 1603 another entry states, that the east and north walls were also unsafe; and thus it continued wanting still greater repairs, in which the Mercers' Company expended vast sums of money, till it was entirely destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

Sir Thomas Gresham, by his will, bequeathed this building, with his house in Bishopsgate-street, to the Mercers' Company and the Corporation of London, in joint trust: the house as a college, and the produce of the Exchange for the payment, in the first place, of the salaries of the lecturers and the other expenses of the college; and secondly, of certain annual sums to different hospitals, prisons, and almshouses.

Such was the origin of the Royal Exchange. After its destruction, in 1666, the funds in the hands of Sir Thomas Gresham's trustees amounted to no more than £234. 8s. 2d.; but, with a spirit beyond all praise, they contributed from their own resources the necessary sum for rebuilding the Exchange, which was completed and opened September 28, 1669, the total cost being £58,962, which the City Corporation and the Mercers' Company defrayed equally between them. Since that period it has undergone several reparations; but a most complete and substantial one was commenced in 1820, under the direction of Mr. Geo. Smith, architect to the Mercers' Company, the estimated expense of which was nearly £33,000; and staircases on the north, south, and west sides have since been built of stone, at an expense of about £6,000.

The emoluments derived by Lady Gresham from the Royal Exchange are stated to have amounted to £751. 5s. per annum; and these she continued to enjoy till her decease, in the year 1596; but the Mercers' Company, instead of profiting by the donation, had, after the [pg 259] late repairs, expended out of their own fund no less a sum than £200,500.

We are indebted to an active Correspondent for the original of the engraving (a pencil drawing), and the abridgment of the previous description, from a neatly compiled work—the Percy History of London, and from original and authentic sources. We are, however, compelled to omit the "dimensions of the ground on which the original Exchange stood," notwithstanding our Correspondent has been at the pains to copy the items from "an old record in the Chamber of London, never before made public." The document is of considerable value, in illustrating the topography of ancient London; but its interest is hardly popular enough for our pages.

Winton—ere thee I leave in hoary pride,

Thy hallow'd temples, and thine aged towers,

Lifting their heads amid the rural bowers

That grace fair Itchen's ever-rippling tide,

I gaze—and think how many a century

Hath slowly roll'd along, since in their might

The British Chieftain and the Roman Knight

First met in thee in triumph or to die.

But now in peace along thy vale I rove,

Or mark with awe thy venerable pile

Of mitred pomp, and down the lengthen'd aisle

Listen to notes divine, with those I love.

These are the charms that memory must renew,

Till I shall gaze again, with reverence due.

"Justum et tenacem propositi virum"

Nor direful rage, nor bois'trous tumult loud,

Nor looks infuriate of the threat'ning crowd—

Nor haughty tyrants, with their angry scowl,

Like beasts that o'er the traveller's pathway prowl—

Nor southern storm, that o'er the ocean raves,

And swells in mountain heights its restless waves,

Can aught avail, with all their force combined,

To shake the man with firm, though tranquil, mind!

Guided by Justice and by Wisdom's laws,

Secure he stands to guard his righteous cause.

What—tho' in awful haste the tott'ring world,

By Heaven's command, be into ruin hurl'd:

As on a rock unshaken he remains,

Upborne by Him who all the just sustains!

Destruction's thunders rage from pole to pole—

Yet he undaunted smiles, and bids them calmly roll!

Among the list of benefactions in the parish church of St. Sepulchre is the following, relative to the tolling of the church-bell on the eve of the execution of unhappy criminals:

"Robert Doue, Citizen and Merchant Tailor of London, gave to the parish church of St. Sepulchre's the somme of £50. That after the several Sessions of London, when the prisoners remain in the gaole as condemned men to death, expecting execution on the morrow following, the clarke (that is, the parson) of the church shoold come in the night time, and likewise in the morning, to the window of the prison where they lye, and there ringing certain tolls with a hand-bell appointed for the purpose, he doth afterwards (in most Christian manner) put them in mind of their present condition and ensuing execution, desiring them to be prepared therefore as they ought to be. When they are in the cart, and brought before the wall of the church, there he standeth ready with the same bell, and after certain toles rehearseth an appointed praier, desiring all the people there present to pray for them. The Beadle, also, of Merchant Taylors' Hall hath an honest stipend allowed to See that this is duly done."

It has been a very ancient custom, on the night previous to the execution of condemned criminals, for the bellman of the above parish to go under Newgate, and, ringing his bell, repeat the verses beneath (which, by the above extract, it would appear, should be the duty of the clergyman), as a friendly admonition to the wretched prisoners:

"All you that in the condemned hold do lie,

Prepare you, for to-morrow you shall die!

Watch all and pray, the hour is drawing near

That you before the Almighty must appear:

Examine well yourselves, in time repent,

That you may not t' eternal flames be sent.

And when St. Sepulchre's bell to-morrow tolls,

The Lord above have mercy on your souls!

Past twelve o'clock!"

In the case of Stephen Gardener, who was executed at Tyburn, in 1724, the bellman chanted the above verses. This man, with another, being brought to St. Sepulchre's watch-house, on suspicion of felony, which, however, was not validated, they were dismissed. "But," said the constable to Gardener, "beware how you come here again, or this bellman will certainly say his verses over you;" for the dreaded bellman happened to be then in the watch-house.—Such proved to be the case, for the same man suffered the penalty of the law, for housebreaking, "the day and year first above mentioned."

We lost sight of the Needles at sunset. There was little wind; but a heavy weltering sea throughout the night. Nevertheless, our bark drove merrily on her way, and at day-break the French coast, near Cape de la Hogue, was dimly visible through the haze of morning. At dawn the breeze died away; and as the tide set strongly against us, it was found necessary to let go an anchor, in order to prevent the current from carrying us out of our course. The surface of the ocean, though furrowed by the long deep swell peculiar to seas of vast extent, looked as if oil had been poured upon it. The vessel pitched prodigiously too; but neither foam-bubbles nor spray ruffled the glassy expanse. Wave after wave swept by in majesty, smooth and shining like mountains of molten crystal; and though the ocean was agitated to its profoundest depths, its convulsed bosom had a character of sublime serenity, which neither pen nor pencil could properly describe.

The night-dew had been remarkably heavy, and when the sun burst through the thick array of clouds that impended over the French coast, the cordage and sails discharged a sparkling shower of large pellucid drops. In the course of the forenoon, a small bird of the linnet tribe perched on the rigging in a state of exhaustion, and allowed itself to be caught. It was thoughtlessly encaged in the crystal lamp that lighted the cabin, where it either chafed itself to death, or died from the intense heat of the noon-day sun, which shone almost vertically on its prison. At the time this bird came on board, we were at least ten miles northward of the island of Alderney, the nearest land.

At one P.M. tide and wind favouring, we weighed anchor, and stood away for the Race of Alderney, which separates that island from Cape de la Hogue. In the Race the tide ran with a strength and rapidity scarcely paralleled on the coasts of Britain. The famous gulf of Coryvreckan in the Hebridean Sea, and some parts of the Pentland Firth, are perhaps the only places where the currents are equally irresistible. To the latter strait, indeed, the Alderney Race bears a great resemblance; and an Orkney man unexpectedly entering it, would be in danger of mistaking Alderney for Stroma, and Cape de la Hogue for Dunnet Head. In stormy weather the passage of the Race is esteemed by mariners an undertaking of some peril—a fact we felt no disposition to gainsay; for though the day was serene, and the swell from the westward completely broken by the intervention of the island, the conflict of counter-currents was tremendous. At some places the water appeared in a state of fierce ebullition, leaping and foaming as if convulsed by the action of submarine fires; at others it formed powerful eddies, which rendered the helm almost of no avail in the guidance of the vessel.

We steered as near to Alderney, or Aurigni as it is frequently called, as prudence warranted. It is a high, rugged, bare-looking island, encompassed by perilous reefs, but supporting a pretty numerous population. The only arborescent plants discernible from the deck of our vessel, were clumps of brushwood. The grain on the cultivated spots was uncut, and several wind-mills on the higher grounds, indicated the means by which the islanders, who have very little intercourse with the rest of the world, reduce their wheat into flour. The southern side of the island is precipitous, and its eastern cape terminates in a fantastic rock called the Cloak, which our captain consulted as a landmark in steering through the Race. There is only one village in Alderney—a paltry place, named St. Anne, or in common parlance La Ville; and there a detachment of troops is generally stationed. Small vessels only can enter the harbour, which is shelterless, and rendered difficult of access by a sunken reef. At sunset Alderney was far astern, and three of its sister islands, Sark, Herm, and Jethau, were in view ahead.

It was impossible to behold, without a portion of romantic enthusiasm, the dazzling radiance of the orb of day, as it went down in splendour beyond the gleaming waves. A thousand affecting emotions are liable to be excited by the prospect of that mighty sea whose farther boundaries lie in another hemisphere—whose waters have witnessed the noblest feats of maritime enterprise, and the fiercest conflicts of hostile fleets. Where shall we find the man to whom science is dear, who dreams not of Columbus, when he first feels himself rocked by the majestic billows of the Atlantic—who regards not the golden [pg 261] line of light, which the setting sun casts over the waste of waters, as a type of the intellectual illumination experienced by the ocean pilgrim, when he first steered his bark into its solitudes? Who can survey, even the hither strand of that vast sea, without reflecting that the waves that break at his feet have laved the palm-fringed shores of America; and that the bones of millions—the pride, and pomp, and treasure of nations—repose in the same capacious tomb?

Anxious to be a spectator of the perils that beset navigation among these islands, I repaired to the deck before day-break, at which time, according to our captain's calculation, we were likely to double the Corbiére—a well-known promontory on the western side of Jersey—which requires to be weathered with great circumspection. Jersey was already visible on our larboard bow—a lofty precipitous coast. Wind and tide were in our favour, and we swept smoothly and rapidly round the cape; but the jagged summits of the reefs that environ it, and the impetuosity of the currents, bore incontestable evidence to the verity of the tales of misfortune which our captain associated with its name. The rock which bears the appellation of the Corbiére, is close in shore, and so grotesque in form, as to be readily singled out from the adjacent cliffs. A reef, visible only at low water, shoots from it a considerable distance into the sea, and another ledge of the same aspect, lies still farther seaward; consequently the course of a careful pilot, is to hold his way free through the channel between them. If a lands-*man may be permitted to make an observation on a nautical point, I would say that our steersman kept the peak of the Corbiére exactly on a level with the adjacent precipices, till we were directly abreast of the headland, and then stood abruptly in-shore till within a few fathoms of the cliffs, under the shadow of which he afterwards held a steady course till we opened the bay of St. Aubin.

The fantastic and inconstant outline of the Corbiére, as we were hurried swiftly past it, was a subject of surprise and admiration. When first seen through the haze of morning, it resembled a huge elephant supporting an embattled tower; a little after, it assumed the similitude of a gigantic warrior in a recumbent posture, armed cap-a-pie; anon, this apparition vanished, and in its stead rose a fortalice in miniature, with pigmy sentinels stationed on its ramparts. The precipices between the Corbiére and the bay of St. Aubin, are no less worthy of notice than that promontory. They slope down to the water-edge in enormous protuberances, resembling billows of frozen lava, intersected by wide sinuous rifts, and present a most interesting field for geological research.

The bay of St. Aubin is embraced by a crescent of smiling eminences thickly sprinkled with villas and orchards. St. Helier crouches at the base of a lofty rock that forms the eastern cape: the village of St. Aubin is similarly placed near Noirmont Point, the westward promontory, and between the two, stretches a sandy shelving beach, studded with martello towers. The centre of the bay is occupied by Elizabeth Castle—a fortress erected on a lofty insulated rock, the jagged pinnacles of which shoot up in grotesque array round the battlements. The harbour is artificial, but capacious and safe, and so completely commanded by the castle, as to be nearly inaccessible to an enemy. The jetties and quays, which had only been recently constructed, are of great extent and superior masonry. The majority of the vessels in port were colliers from England; but summer is not the season to look for crowded harbours. The merchants of St. Helier engage deeply in the Newfoundland fishery, and are otherwise distinguished for maritime enterprise; consequently there is no reason to infer that the vast sum of money which must of necessity have been expended in the improvement of the harbour, has been unprofitably sunk. During the late war the islanders rapidly increased in opulence, as the island was filled with troops and emigrants, who greatly enhanced the value of home produce; but the cessation of hostilities restored matters to their natural order, and the Jerseymen bewail the return of peace and plenty with as much sincerity as any half-pay officer that ever doffed his martial appurtenances.

St. Helier may contain about 7,000 inhabitants. Internally it differs little from the majority of small sea-ports in England, save it may be in the predominance of foreign names on the signboards, and the groups of French marketwomen, distinguished by their fantastic head-gear, who perambulate the streets. The only place worthy of a visit is the market, which, for orderly arrangement, and plenteous supply, is scarcely excelled in any quarter of the world. It was occupied chiefly by Norman women, who repair here regularly once a-week from Granville to dispose of their fowls, [pg 262] fish, eggs, fruit, and vegetables. Most of them were seated at their stalls, and industriously plying their needles, when not occupied in serving customers. They had a mighty demure look, and never condescended to solicit any person to deal with them—a mode of behaviour which the butchers, fishmongers, fruiterers, and greengrocers, of Great Britain would do well to imitate. The generality were hard-featured; and their grotesque head-dresses, parti-coloured kerchiefs, and short clumsily-plaited petticoats, gave them a grotesque, antiquated air, altogether irreconcilable to an Englishman's taste. They were, however, wonderfully clean, and civil and honourable in their traffic, compared with the filthy, ribald, over-reaching hucksters who infest our markets; and it was gratifying to hear that the Jersey people encouraged their visits, and treated them with hospitality and respect.

The rock on which Elizabeth Castle is perched, is nearly a mile in circuit, and accessible on foot at low water by means of a mole, formed of loose stones and rubbish, absurdly termed "the Bridge," which connects it with the mainland. In times of war with France, this fortress was a post of great importance, and strongly garrisoned; but in these piping days of peace, I found only one sentinel pacing his "lonely round" on the ramparts. The barracks were desolate—the cannon dismounted—and grass sufficient to have grazed a whole herd, had sprung up in the courts, and among the pyramids of shot and shells piled up at the embrazures. The gate stood open, inviting all who listed to enter, and native or foreigner might institute what scrutiny he pleased without interruption.

The hermitage of St. Elericus, the patron saint of Jersey, a holy man who suffered martyrdom at the time the pagan Normans invaded the island, is said to have occupied an isolated peak, quite detached from the fortifications, which commands a noble seaward view of the bay. A small arched building of rude masonry, having the semblance of a watch-tower, covers a sort of crypt excavated in the rock, into which, by dint of perseverance, a man might introduce himself; and this, if we are to credit tradition, is the cave and bed of the ascetic. Here, like the inspired seer of Patmos, he could congratulate himself on having shaken off communion with mankind. Cliffs shattered by the warfare of the elements—a restless and irresistible sea, intersected by perilous reefs—and the blue firmament—were the only visible objects to distract the solemn contemplations of his soul.

An abbey, dedicated to St. Elericus, once occupied the site of Elizabeth Castle. The fortress was founded on the ruins of this edifice in 1551, in the reign of Edward VI., and according to tradition, all the bells in the island, with the reservation of one to each church, were seized by authority, and ordered to be sold, to defray in part the expense of its erection. The confiscated metal was shipped for St. Malo, where it was expected to bring a high price, but the vessel foundered in leaving the harbour, to the triumph of all good Catholics, who regarded the disaster as a special manifestation of divine wrath at the sacrilegious spoliation.

The works of Fort Regent occupy the precipitous hill that overhangs the harbour, and completely command Elizabeth Castle, and indeed the whole bay. They are of great strength, and immense masses of rock have been blown away from the cliff in order to render it impregnable. The barracks are bomb-proof, and scooped in the ramparts; and the parade ground, which in shape exactly resembles a coffin, forms the nucleus of the fortifications. This fortress had been completed since the peace, and we found the 12th regiment of the line garrisoning it; but little of the pomp and circumstance of warlike preparation was visible on its ramparts. The prospect seaward is magnificent, and includes a vast labyrinth of rocks called the Violet Bank, which fringes the south-eastern corner of the island. One glimpse of this submarine garden is sufficient to satisfy the most apprehensive patriot, that Jersey is in a great measure independent of "towers along the steep."

At St. Helier a stranger may, without any great stretch of imagination, fancy himself in England; but no sooner does he penetrate into the country, than such self-deception becomes impossible. The roads, even the best of them, are mere paths, narrow, deep sunk between enormous dikes, and so fenced by hedges and trees, as to be almost impervious to the light of day. The fields, of which it is scarce possible to obtain a glimpse from these "covered ways," are paltry paddocks, rarely exceeding two or three acres. Hedges and orchards render the face of the country like a forest, and nearly as much ground is occupied by lanes and fences as is under the plough.

(To be concluded in our next.)

Every reader of dramatic history has heard of Garrick's contest with Madam Clairon, and the triumph which the English Roscius achieved over the Siddons of the French stage, by his representation of the father struck with fatuity on beholding his only infant child dashed to pieces by leaping in its joy from his arms: perhaps the sole remaining conquest for histrionic tragedy is somewhere in the unexplored regions of the mind, below the ordinary understanding, amidst the gradations of idiotcy. The various shades and degrees of sense and sensibility which lie there unknown, Genius, in some gifted moment, may discover. In the meantime, as a small specimen of its undivulged dramatic treasures, we submit to our readers the following little anecdote:—

A poor widow, in a small town in the north of England, kept a booth or stall of apples and sweetmeats. She had an idiot child, so utterly helpless and dependent, that he did not appear to be ever alive to anger or self-defence.

He sat all day at her feet, and seemed to be possessed of no other sentiment of the human kind than confidence in his mother's love, and a dread of the schoolboys, by whom he was often annoyed. His whole occupation, as he sat on the ground, was in swinging backwards and forwards, singing "pal-lal" in a low pathetic voice, only interrupted at intervals on the appearance of any of his tormentors, when he clung to his mother in alarm.

From morning to evening he sang his plaintive and aimless ditty; at night, when his poor mother gathered up her little wares to return home, so deplorable did his defects appear, that while she carried her table on her head, her stock of little merchandize in her lap, and her stool in one hand, she was obliged to lead him by the other. Ever and anon as any of the schoolboys appeared in view, the harmless thing clung close to her, and hid his face in her bosom for protection.

A human creature so far below the standard of humanity was no where ever seen; he had not even the shallow cunning which is often found among these unfinished beings; and his simplicity could not even be measured by the standard we would apply to the capacity of a lamb. Yet it had a feeling rarely manifested even in the affectionate dog, and a knowledge never shown by any mere animal.

He was sensible of his mother's kindness, and how much he owed to her care. At night when she spread his humble pallet, though he knew not prayer, nor could comprehend the solemnities of worship, he prostrated himself at her feet, and as he kissed them, mumbled a kind of mental orison, as if in fond and holy devotion. In the morning, before she went abroad to resume her station in the market-place, he peeped anxiously out to reconnoitre the street, and as often as he saw any of the schoolboys in the way, he held her firmly back, and sang his sorrowful "pal-lal."

One day the poor woman and her idiot boy were missed from the market-place, and the charity of some of the neighbours induced them to visit her hovel. They found her dead on her sorry couch, and the boy sitting beside her, holding her hand, swinging and singing his pitiful lay more sorrowfully than he had ever done before. He could not speak, but only utter a brutish gabble! sometimes, however, he looked as if he comprehended something of what was said. On this occasion, when the neighbours spoke to him, he looked up with the tear in his eye, and clasping the cold hand more tenderly, sank the strain of his mournful "pal-lal" into a softer and sadder key.

The spectators, deeply affected, raised him from the body, and he surrendered his hold of the earthy hand without resistance, retiring in silence to an obscure corner of the room. One of them, looking towards the others, said to them, "Poor wretch! what shall we do with him?" At that moment he resumed his chant, and lifting two handfuls of dust from the floor, sprinkled it on his head, and sang with a wild and clear heart-piercing pathos, "pal-lal—pal-lal."—Blackwood's Magazine.

Comparative estimate respecting the dimensions of the head of the inhabitants in several counties of England.

The male head in England, at maturity, averages from 6-1/2 to 7-5/8 in diameter; the medium and most general size being 7 inches. The female head is smaller, varying from 6-3/8 to 7, or 7-1/2, the medium male size. Fixing the medium of the English head at 7 inches, there can be no difficulty in distinguishing [pg 264] the portions of society above from those below that measurement.

London.—The majority of the higher classes are above the medium, while amongst the lower it is very rare to find a large head. Spitalfields Weavers have extremely small heads, 6-1/2, 6-5/8, 6-3/4, being the prevailing admeasurement.

Coventry.—Almost exclusively peopled by weavers, the same facts are peculiarly observed.

Hertfordshire, Essex, Suffolk, and Norfolk, contain a larger proportion of small heads than any part of the empire; Essex and Hertfordshire, particularly. Seven inches in diameter is here, as in Spitalfields and Coventry, quite unusual—6-5/8 and 6-1/2 are more general; and 6-3/8, the usual size for a boy of six years of age, is frequently to be met with here in the full maturity of manhood.

Kent, Surrey, and Sussex.—An increase of size of the usual average is observed; and the inland counties, in general, are nearly upon the same scale.

Devonshire and Cornwall.—The heads of full sizes.

Herefordshire.—Superior to the London average.

Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cumberland, and Northumberland, have more large heads, in proportion, than any part of the country.

Scotland.—The full-sized head is known to be possessed by the inhabitants; their measurement ranging between 7-3/4 and 7-7/8 even to 8 inches; this extreme size, however, is rare.—Literary Gazette.

The laying-out of the tract of ground on the northern verge of the Regent's Park, and divided from the present garden of the Zoological Society, has at length been commenced, and is proceeding with great activity. We described this as part of the gardens in our illustrated account of them in No. 330 of the MIRROR, and we now congratulate the Society on their increased funds which have enabled them to begin this very important portion of their original design.

For the purposes of these alterations, the belt of trees and shrubs which formed so complete and natural a barrier between the road and canal, will be removed; but when the buildings, &c. are completed, trees and shrubs are to be replanted close to the road. In addition to huts, cages, &c. for the reception of living animals, it is said that a building will be erected in the new garden for the whole or part of the Society's Museum, now deposited in Bruton Street. This is very desirable, as the Establishment will then combine similar advantages to those of the Jardin des Plantes at Paris, where the Museum is in the grounds. The addition of a botanical garden would then complete the scheme, and it is reasonable to hope that some of the useless ground in the park may be applied to this very serviceable as well as ornamental purpose.

The communication between the present Zoological exhibition, and the additions in preparation, will be by a vaulted passage beneath the road. This subterranean passage will be useful for the abode of such portions of varied creation as love the shade, as bats, owls, &c.

The King's Giraffe died on Sunday week, at the Menagerie at Sandpit-gate, near Windsor. It was nearly four years and a half old, and arrived in England in August, 1827, as a present from the Pacha of Egypt to his Majesty.

About the same time another Giraffe arrived at Marseilles, being also a present from the Pacha to the King of France. This and the deceased animal were females, and were taken very young by some Arabs, who fed them with milk. The Governor of Sennaar, a large town of Nubia, obtained them from the Arabs, and forwarded them to the Pacha of Egypt. This ruler determined on presenting them to the Kings of England and France; and as there was some difference in size, the Consuls of each nation drew lots for them. The shortest and weakest fell to the lot of England. The Giraffe destined for our Sovereign was conveyed to Malta, under the charge of two Arabs; and was from thence forwarded to London, in the Penelope merchant vessel, and arrived on the 11th of August. The animal was conveyed to Windsor two days after, in a spacious caravan. The following were its dimensions, as measured shortly after its arrival at Windsor:

Ft. In.

From the top of the head to the bottom of the hoof ... 10 8

Length of the head ... 1 9

From the top of the head to the neck root ... 4 0

From the neck-root to the elbow ... 2 3 From the elbow to the upper part of the knee ... 1 8 From the upper part of the knee to the fetlock joint ... 1 11 From the fetlock joint to the bottom of the hoof ... 0 10 Length of the back ... 3 1 From the croup to the bottom of the hoof ... 5 8 From the hock to the bottom of the hoof ... 2 9 Length of the hoof ... 0 7-1/2

From the period of its arrival to June last, the animal grew 18 inches. Her usual food was barley, oats, split beans, and ash-leaves: she drank milk. Her health was not good; her joints appeared to shoot over, and she was very weak and crippled. She was occasionally led for exercise round her paddock, when she was well enough, but she was seldom on her legs: indeed, so great was the weakness of her fore legs for some time previous to her death, that a pulley was constructed, being suspended from the ceiling of her hovel, and fastened round her body, so as to raise her on her legs without any exertion on her part. When she first arrived she was exceedingly playful, and up to her death continued perfectly harmless.—Abridged from the library of Entertaining Knowledge.

(Concluded from page 256.)

On the 10th of April, 1764, the family arrived in England, and remained there until the middle of the following year. Leopold Mozart fell ill of a dangerous sore throat during his stay, and as no practising could go forward in the house at that time, his son employed himself in writing his first sinfonia. It was scored with all the instruments, not omitting drums and trumpets. His sister sat near him while he wrote, and he said to her, "remind me that I give the horns something good to do." An extract or two from the correspondence of the father will show how they were received in England:—

"A week after, as we were walking in St. James's Park, the king and queen came by in their carriage, and, although we were differently dressed, they knew us, and not only that, but the king opened the window, and, putting his head out and laughing, greeted us with head and hands, particularly our Master Wolfgang."

"On the 19th of May, we were with their Majesties from six to ten o'clock in the evening. No one was present but the two princes, brothers to the king and queen. The king placed before Wolfgang not only pieces of Wagenseil, but of Bach, Abel, and Handel, all of which he performed prima vista. He played upon the king's organ in such a style that every one admired his organ even more than his harpsichord performance. He then accompanied the queen, who sang an air, and afterwards a flute-player in a solo. At last they gave him the bass part of one of Handel's airs, to which he composed so beautifal a melody that all present were lost in astonishment. In a word, what he knew in Salzburg was a mere shadow of his present knowledge; his invention and fancy gain strength every day."

"A concert was lately given at Ranelagh for the benefit of a newly erected Lying-in-Hospital. I allowed Wolfgang to play a concerto on the organ at it. Observe—this is the way to get the love of these people."

A large portion of Leopold Mozart's letters is occupied with masses to be offered up for the health, &c.; and during his sojourn in the Five-fields, Chelsea, he appears to have been in considerable hope that he had converted a Mr. Sipruntini (a Dutch Jew, and a fine violoncello player), to Catholicism. After dedicating a set of sonatas to the queen, and experiencing great patronage from the nobility, Mozart, with his father and sister, in July, 1765, crossed over into the Netherlands. At the Hague, a fever attacked both children, and had nearly cost the daughter her life. On their recovery, they played before the Prince of Orange, and Wolfgang composed some variations on a national air, which was, just then, sung, piped, and whistled throughout the streets of Holland. The organist of the cathedral in Haerlem waited upon the Mozarts, and invited the son to try his instrument, which he did the next morning. Mozart senior describes the organ as a magnificent one, of sixty-eight stops, and built wholly of metal, "as wood would not endure the dampness of the Dutch atmosphere." Upon the return of the family to Salzburg, Mozart enjoyed a year of quiet and uninterrupted study in the higher walks of composition. Besides applying to the old masters, he was indefatigable in perusing the works of Emanuel Bach, Hasse, Handel, and Eberlin, and by the diligent performance [pg 266] of these authors, he acquired extraordinary brilliancy and power in the left hand. On the 11th of September, 1767, the whole family proceeded on their way to Vienna; but as the small pox was raging there, they went to Ollmütz instead, where both the children caught that disorder. At Vienna, Mozart wrote his first opera, by desire of the emperor. Though the singers extolled their parts to the skies, in presence of Leopold Mozart, they formed in secret a cabal against the work, and it was never performed. The Italian singers and composers who were established in this capital did not like to find themselves surpassed in knowledge and skill by a boy of twelve years old, and they therefore not only charged the composition with a want of dramatic effect, but they even went so far as to say, that he had not scored it himself. To counteract such calumnies, Leopold Mozart often obliged his son to put the orchestral parts to his compositions in the presence of spectators, which he did with wonderful celerity before Metastasio, Hasse, the Duke of Braganza, and others. The injurious opinion of the nobility, which these people hoped to excite against the young musician, had no success; for he composed a Mass—an Offertorium—and a Trumpet Concerto for a Boy—which were performed before the whole court, and at which he himself presided and beat the time. The year 1769 was employed by Wolfgang in studying the Italian language, and in the practice of composition; and at this time he was appointed concert master to the court of Salzburg.

Father and son now made the tour of Italy, and met in every city with an enthusiastic reception.

In Rome, Mozart gave a miraculous attestation of his quickness of ear, and extensive memory, by bringing away from the Sistine Chapel the "Miserere of Allegri," a work full of imitation and repercussion, mostly for a double choir, and continually changing in the combination and relation of the parts. This accomplished piece of thievery was thus performed:—the sketch was drawn out upon the first hearing, and filled up from recollection at home—Mozart then repaired to the second and last performance, with his manuscript in his hat, and corrected it.

The slow voluptuous movement of the style of dancing prevalent in Italy gave Mozart great pleasure; in the postscripts to his father's letters, which he generally addressed to his sister and playfellow, he speaks of this subject with as much zest as of his own art. Later in manhood he became a pupil of Vestris, and the gracefulness of his dancing was much admired, especially in the minuet.

About this time Mozart's voice began to break, and he ceased to sing in public, unless words were put before him; the violin he continued to play, but mostly in private. The alarming illnesses which had attacked his children on their journey kept Leopold Mozart in continual anxiety—the malaria of Rome and the heat of Naples were alike dreaded by him.

The travellers arrived at Naples in May, and fortunately procured cool and healthy lodgings. Here they visited the English Ambassador, Sir William Hamilton, whose acquaintance they had made in London, and whose lady was not only a very agreeable person, but a charming performer on the harpsichord. She trembled on playing before Mozart. The concerts given by the Mozarts in Naples were very successful, and they were treated with great distinction; the carriages of the nobility, attended by footmen with flambeaux, fetched them from home and carried them back; the queen greeted them daily on the promenade, and they received invitations to the ball given by the French Ambassador on the marriage of the Dauphin.

If Mozart had not been engaged to compose the carnival opera for Milan, he might have written that for Bologna, Rome, or Naples, as at these three cities offers were made to him, a proof of what his genius had effected in Italy.

The epoch at which Mozart's genius was ripe may be dated from his twentieth year; constant study and practice had given him ease in composition, and ideas came thicker with his early manhood—the fire, the melodiousness, the boldness of harmony, the inexhaustible invention which characterize his works, were at this time apparent; he began to think in a manner entirely independent, and to perform what he had promised as a regenerator of the musical art. The situation of his father as Kapell-meister, in Salzburg, indeed gave Mozart some opportunities of writing church music, but not such as he most coveted, the sacred musical services of the court being restricted to a given duration, and the orchestra but poorly supplied with singers; it was therefore his earnest desire to get some permanent [pg 267] appointment in which he could exercise freely his talent for composition, and reckon on a sufficient income. When childhood and boyhood had passed away, his quondam patrons ceased to wonder at, or feel interest in, his genius, and Mozart, whose early years had been spent in familiar intercourse with the principal nobility of Europe, who had been from court to court, and received distinctions and caresses unparalleled in the history of musicians, up to the period of his death gained no situation worthy his acceptance, but earned his fame in the midst of worldly cares and annoyances, in alternate abundance and poverty, deceived by pretended friendship, or persecuted by open enmity. The obstacles which Mozart surmounted in establishing the immortality of his muse, leave those without excuse who plead other occupations and the necessity of gaining a livelihood as an excuse for want of success in the art. Where the creative faculty has been bestowed, it will not be repressed by circumstances.

In the exterior of Mozart there was nothing remarkable; he was small in person, and had a very agreeable countenance, but it did not discover the greatness of his genius at the first glance. His eyes were tolerably large and well shaped, more heavy than fiery in the expression; when he was thin they were rather prominent. His sight was always quick and strong; he had an unsteady abstracted look, except when seated at the piano-forte, when the whole form of his visage was changed. His hands were small and beautiful, and he used them so softly and naturally upon the piano-forte, that the eye was no less delighted than the ear. It was surprising that he could grasp so much as he did in the bass. His head was too large in proportion to his body, but his hands and feet were in perfect symmetry, of which he was rather vain. The stunted growth of Mozart's body may have arisen from the early efforts of his mind; not, as some suppose, from want of exercise in childhood—for then he had much exercise—though at a later period the want of it may have been hurtful to him. Sophia, a sister-in-law of Mozart, who is still living, relates: "he was always good-humoured, but very abstracted, and in answering questions seemed always to be thinking of something else. Even in the morning when he washed his hands, he never stood still, but would walk up and down the room, sometimes striking one heel against the other; at dinner he would frequently make the ends of his napkin fast, and draw it backwards and forwards under his nose, seeming lost in meditation, and not in the least aware of what he did." He was fond of animals, and in his amusements delighted with any thing new; at one time of his life with riding, at another with billiards.

"O No, sweet Lady, not to thee

That set and chilling tone,

By which the feelings on themselves

So utterly are thrown,

For mine has sprung upon my lips,

Impatient to express

The haunting charm of thy sweet voice

And gentlest loveliness.

A very fairy queen thou art,

Whose only spells are on the heart.

The garden it has many a flower,

But only one for thee—

The early graced of Grecian song,

The fragant myrtle tree;

For it doth speak of happy love,

The delicate, the true.

If its pearl buds are fair like thee,

They seem as fragile too;

Likeness, not omens; for love's power

Will watch his own most precious flower.

Thou art not of that wilder race

Upon the mountain side,

Able alike the summer sun

And winter blast to bide;

But thou art of that gentle growth

Which asks some loving eye

To keep it in sweet guardianship,

Or it must droop and die;

Requiring equal love and care,

Even more delicate than fair.

I cannot paint to thee the charm

Which thou hast wrought on me;

Thy laugh, so like the wild bird's song

In the first bloom-touch'd tree.

You spoke of lovely Italy,

And of its thousand flowers;

Your lips had caught the music breath

Amid its summer bow'rs.

And can it be a form like thine

Has braved the stormy Apennine?

I'm standing now with one white rose

Where silver waters glide

I've flung that white rose on the stream—

How light it breasts the tide!

The clear waves seem as if they loved

So beautiful a thing;

And fondly to the scented leaves

The laughing sunbeams cling.

A summer voyage—fairy freight;—

And such, sweet Lady, be thy fate!"

Three volumes of tales and sketches of considerable graphic interest, have lately been published under the title of "Stories of Waterloo." The first inquiry will naturally be whether they [pg 268] throw any new lights on the ever-memorable struggle. The details of the day are vividly sketched, and as they must be familiar to all our readers, the following excellent general observations will be appreciated:—

"No situation could be more trying to the unyielding courage of the British army than their disposition in square at Waterloo. There is an excited feeling in an attacking body that stimulates the coldest, and blunts the thought of danger. The tumultuous enthusiasm of the assault spreads from man to man, and duller spirits catch a gallant frenzy from the brave around them. But the enduring and devoted courage which pervaded the British squares, when, hour after hour, mowed down by a murderous artillery, and wearied by furious and frequent onsets of lancers and cuirassiers; when the constant order—'Close up!—close up!' marked the quick succession of slaughter that thinned their diminished ranks; and when the day wore later, when the remnants of two, and even three regiments were necessary to complete the square which one of them had formed in the morning—to support this with firmness, and 'feed death,' inactive and unmoved, exhibited that calm and desperate bravery which elicited the admiration of Napoleon himself.

"There was a terrible sameness in the battle of the 18th of June, which distinguishes it in the history of modern slaughter. Although designated by Napoleon 'a day of false manoeuvres,' in reality there was less display of military tactics at Waterloo than in any general action we have on record. Buonaparte's favourite plan was perseveringly followed. To turn a wing, or separate a position, was his customary system. Both were tried at Hougomont to turn the right, and at La Haye Sainte to break through the left centre. Hence the French operations were confined to fierce and incessant onsets with masses of cavalry and infantry, generally supported by a numerous and destructive artillery.

"Knowing that to repel these desperate and sustained attacks a tremendous sacrifice of human life must occur, Napoleon, in defiance of their acknowledged bravery, calculated on wearying the British into defeat. But when he saw his columns driven back in confusion—when his cavalry receded from the squares they could not penetrate—when battalions were reduced to companies by the fire of his cannon, and still that 'feeble few' showed a perfect front, and held the ground they had originally taken, no wonder his admiration was expressed to Soult—'How beautifully these English fight!—but they must give way!'"

The closing scene is then described with great animation:—

"The irremediable disorder consequent on this decisive repulse, and the confusion in the French rear, where Bulow had fiercely attacked them, did not escape the eagle glance of Wellington. 'The hour is come!' he is said to have exclaimed; and closing his telescope, commanded the whole line to advance. The order was exultingly obeyed: forming four deep, on came the British:—wounds, and fatigue, and hunger, were all forgotten! With their customary steadiness they crossed the ridge; but when they saw the French, and began to move down the hill, a cheer that seemed to rend the heavens pealed from their proud array, and with levelled bayonets they pressed on to meet the enemy.

"But, panicstruck and disorganized, the French resistance was short and feeble. The Prussian cannon thundered in their rear; the British bayonet was flashing in their front; and, unable to stand the terror of the charge, they broke and fled. A dreadful and indiscriminate carnage ensued. The great road was choked with the equipage, and cumbered with the dead and dying; while the fields, as far as the eye could reach, were covered with a host of helpless fugitives. Courage and discipline were forgotten, and Napoleon's army of yesterday was now a splendid wreck—a terror-stricken multitude. His own words best describe it—'It was a total rout!'

"But although the French army had ceased to exist as such, and now (to use the phrase of a Prussian officer) exhibited rather the flight of a scattered horde of barbarians, than the retreat of a disciplined body—never had it, in the proudest days of its glory, shown greater devotion to its leader, or displayed more desperate and unyielding bravery, than during the long and sanguine battle of the 18th. The plan of Buonaparte's attack was worthy of his martial renown: it was unsuccessful; but let this be ascribed to the true cause—the heroic and enduring courage of the troops, and the man to whom he was opposed. Wellington without that army, or, that army without Wellington, must have fallen beneath the splendid efforts of Napoleon.

"While a mean attempt has been [pg 269] often made to lower the military character of that great warrior, who is now no more, those who would libel Napoleon rob Wellington of half his glory. It may be the proud boast of England's hero, that the subjugator of Europe fell before him, not in the wane of his genius, but in the full possession of those martial talents which placed him foremost in the list of conquerors—leading that very army which had overthrown every power that had hitherto opposed it, now perfect in its discipline, flushed with recent success, and confident of approaching victory."

1. The Juvenile Forget-me-not. Edited by Mrs. S.C. Hall.

2. The Amulet. By Mr. S.C. Hall.

The tone and temper of these two works—to us the first fruits of "the Annuals" are excellent, as their literary execution is admirable. The first has innumerable attractions for the young; its pleasantness consists in simplicity and truth, whilst its narratives of the playful incidents of childhood are interspersed with "good seed," and precept and pretty illustration spring up in every page. The second work, the Amulet, is calculated for maturer age, and its literary pretensions are consequently of a more advanced order: but of these we shall speak more at length on a future occasion. Our intention in coupling the works at the head of this slight notice is to express our high esteem of the taste which has dictated the scholar and the gentleman in the production of the Amulet, and his ingenious lady in the "delightful task" of writing and catering for those of tender growth, in the Juvenile Forget-me-not. The association is indeed delightful, and has all the interest of a family picture: it beams with affection and parental love, truth, and nature; and happy, thrice happy, must be the union that is crowned with so amiable an intercommunity of mind.

The first few pages of the Juvenile Forget-me-not are very appropriately occupied by a playful paper by the late Mrs. Barbauld, the sincerity and tenderness of whose Lessons and Hymns we have never forgotten even amidst all the cares and crosses of after life. How often and how fondly too have we lingered over their delightful pages; and it may be questioned whether any works ever produced a better or more lasting impression on the infantine mind—than these unassuming little volumes. Mrs. Barbauld's present article is entitled "the Misses, addressed to a careless girl"—as the Misses Chief, Management, Lay, Place, Understanding, Representation, Trust, Rule, Hap, Chance, Take, and Miss Fortune; the "latter, though she has it not in her power to be an agreeable acquaintance, has sometimes proved a valuable friend. The wisest philosophers have not scrupled to acknowledge themselves the better for her company, &c." Then follow some pleasing lines to "My Son, My Son," by Allan Cunningham, glorifying the bounty of Providence, "A Tale of a Triangle," by Mary Howitt, is a pretty school sketch. Next are some lines by James Montgomery, on Birds—as the Swallow, Skylark, &c. in all, numbering forty-five. "The Muscle," by Dr. Walsh, consists of half-a-dozen conversational pages, illustrating its natural history in a very pleasing style, which is really worth the attention of many who attempt to simplify science. Next Miss Mitford has a true story of "Two Dolls," and the author of Selwyn a pretty little story, entitled "Prison Roses;" Miss Jewsbury, "Aunt Kate and the Review;" and Mr. S.C. Hall a sketch of a "Blind Sailor"—both of which are very pleasing. "A Child's Prayer," by the Ettrick Shepherd, is a sweet and simple hymn of praise. "The Royal Sufferer," by Mrs. Hofland, follows, and gives the misfortunes of Prince Arthur in an interesting historiette.—We have only room to enumerate "The Birth-day," a sketch from Nature, by Mrs. Opie; an extremely well-drawn Irish sketch, by Mrs. S.C. Hall; and "The Shipwrecked Boy," a tale, by the author of Letters from the East.

The Engravings, twelve in number, are, for the most part, excellent. The Frontispiece—two lovely children—is exquisitely engraved by J. Thomson, as is also "Heart's Ease," by the same artist: the last, especially, is of great delicacy. "Holiday Time," from Richter, is well chosen for this delightful little work.

Altogether, we congratulate the fair Editoress on the very pleasing, attractive, and useful character of her volume for the coming season; and as that for the previous year did not reach us early enough for special notice at the time of publication, we are happy to make the amende, by placing the Juvenile Forget-me-not first on our list of Annuals for 1830.

As the waters of the Irawadi begin to fall, a yearly festival of three days is [pg 270] held, consisting chiefly of boat-racing. It is called the Water-festival, of which we have the following account in Crawfurd's Embassy to Ava:—

"According to promise, a gilt boat and six common war-boats were sent to convey us to the place where these races were exhibited, which was on the Irawadi, before the palace. We reached it at eleven o'clock. The Kyi-wun, accompanied by a palace secretary, received us in a large and commodious covered boat, anchored, to accommodate us, in the middle of the river. The escort and our servants were very comfortably provided for in other covered boats. The king and queen had already arrived, and were in a large barge at the east bank of the river. This vessel, the form of which represented two huge fishes, was extremely splendid; every part of it was richly gilt; and a spire of at least thirty feet high, resembling in miniature that of the palace, rose in the middle. The king and queen sat under a green canopy at the bow of the vessel, which, according to Burman notions, is the place of honour; indeed, the only part ever occupied by persons of rank. The situation of their majesties could be distinguished by the white umbrellas, which are the appropriate marks of royalty. The king, whose habits are volatile and restless, often walked up and down, and was easily known from the crowd of his courtiers by his being the only person in an erect position; the multitude sitting, crouching, or crawling all round him. Near the king's barge were a number of gold boats; and the side of the river, in this quarter, was lined with those of the nobility, decked with gay banners, each having its little band of music, and some dancers exhibiting occasionally on their benches. Shortly after our arrival, nine gilt, war-boats were ordered to manoeuvre before us. The Burmans nowhere appear to so much advantage as in their boats, the management of which is evidently a favourite occupation. The boats themselves are extremely neat, and the rowers expert, cheerful, and animated. In rowing, they almost always sing; and their airs are not destitute of melody. The burthen of the song, upon the present occasion, was literally translated by Dr. Price, and was as follows:—"The golden glory shines forth like the round sun; the royal kingdom, the country and its affairs, are the most pleasant." If this verse be in unison with the feelings of the people, (and I have no doubt it is,) they are, at least, satisfied with their own condition, whatever it may appear to others."

Boat-racing, taming wild elephants, and boxing-matches, are said to be the chief amusements of the king and the people. Mr. Crawfurd saw all these, and he tells us that in the last of them the populace formed a ring with as much regularity as if they had been true-born Englishmen, and preserved it with much greater regularity than is usually witnessed here—thanks to the assistance of the constables with their long staves. While these official persons were duly exercising their authority, the same good-natured monarch, who roasted his prime minister in the sun, frequently called out, "Don't hurt them—don't prevent them from looking on."

Mr. Madden, in his recent Travels in Turkey, having determined to experience the effects of that pestilent practice of eating opium, which is so common in Turkey, he repaired to the market of Theriaki Tchachissy, where he seated himself among the persons who were in the habit of resorting thither for the purpose of enjoying (?) this fatal pleasure. His description of those victims to sensuality is very striking, and is enough to cure any man of common sense of wishing to become an opium eater.

"Their gestures were frightful; those who were completely under the influence of the opium talked incoherently, their features were flushed, their eyes had an unnatural brilliancy, and the general expression of their countenances was horribly wild. The effect is usually produced in two hours, and lasts four or five; the dose varies from three grains to a drachm. I saw one old man take four pills, of six grains each, in the course of two hours; I was told he had been using opium for five-and-twenty years; but this is a very rare example of an opium eater passing thirty years of age, if he commence the practice early. The debility, both moral and physical, attendant on its excitement, is terrible; the appetite is soon destroyed, every fibre in the body trembles, the nerves of the neck become affected, and the muscles get rigid; several of these I have seen, in this place, at various times, who had wry necks and contracted fingers; but still they cannot abandon the custom; they are miserable till the hour arrives for taking their daily dose; and when its delightful influence begins, [pg 271] they are all fire and animation. Some of them compose excellent verses, and others addressed the bystanders in the most eloquent discourses, imagining themselves to be emperors, and to have all the harems in the world at their command. I commenced with one grain; in the course of an hour and a half it produced no perceptible effect, the coffee-house keeper was very anxious to give me an additional pill of two grains, but I was contented with half a one; and another half hour, feeling nothing of the expected reverie, I took half a grain more, making in all two grains in the course of two hours. After two hours and a half from the first dose, I took two grains more; and shortly after this dose, my spirits became sensibly excited; the pleasure of the sensation seemed to depend on a universal expansion of mind and matter. My faculties appeared enlarged; every thing I looked on seemed increased in volume; I had no longer the same pleasure when I closed my eyes which I had when they were open; it appeared to me as if it was only external objects, which were acted on by the imagination, and magnified into images of pleasure; in short, it was 'the faint exquisite music of a dream' in a waking moment. I made my way home as fast as possible, dreading, at every step, that I should commit some extravagance. In walking, I was hardly sensible of my feet touching the ground, it seemed as if I slid along the street, impelled by some invisible agent, and that my blood was composed of some ethereal fluid, which rendered my body lighter than air. I got to bed the moment I reached home. The most extraordinary visions of delight filled my brain all night. In the morning I rose, pale and dispirited; my head ached; my body was so debilitated that I was obliged to remain on the sofa all the day, dearly paying for my first essay at opium eating."

I had a friend that lov'd me;

I was his soul; he liv'd not but in me;

We were so close within each other's breast,

The rivets were not found that join'd us first.

That does not reach us yet; we were so mix'd,

As meeting streams, both to ourselves were lost.

We were one mass, we could not give or take,

But from the same: for He was I; I He;

Return my better half, and give me all myself,

For thou art all!

If I have any joy when thou art absent,

I grudge it to myself; methinks I rob

Thee of thy part.

As good and wise; so she be fit for me,

That is, to will, and not to will the same;

My wife is my adopted self, and she

As me, to what I love, to love must frame.

And when by marriage both in one concur,

Woman converts to man, not man to her.

What do you think of marriage?

I take't, as those that deny purgatory;

It locally contains or heaven or hell;

There's no third place in it.

Nor stand so much on your gentility,

Which is an airy, and mere borrow'd thing,

From dead men's dust and bones; and none of yours,

Except you make, or hold it.

Heav'n is a great way off, and I shall be

Ten thousand years in travel, yet 'twere happy

If I may find a lodging there at last,

Though my poor soul get thither upon crutches.

Dazzled with the height of place,

While our hopes our wits beguile,

No man marks the narrow space

Between a prison and a smile.

Then since fortune's favours fade,

You that in her arms do sleep,

Learn to swim and not to wade,

For the hearts of kings are deep.

But if greatness be so blind,

As to trust in tow'rs of air,

Let it be with goodness joyn'd,

That at least the fall be fair.

An honest soul is like a ship at sea,

That sleeps at anchor upon the occasion's calm;

But when it rages, and the wind blows high,

She cuts her way with skill and majesty.

O sweet woods, the delight of solitariness!

O how much do I like your solitariness!

Here nor reason is hid, vailed in innocence,

Nor envy's snaky eye, finds any harbour here.

Nor flatterer's venomous insinuations.

Nor coming humourist's puddled opinions,

Nor courteous ruin of proffer'd usury,

Nor time prattled away, cradle of ignorance,

Nor causeless duty, nor cumber of arrogance,

Nor trifling titles of vanity dazzleth us,

Nor golden manacles stand for a paradise.

Here wrong's name is unheard; slander a monster is,

Keep thy sprite from abuse, here no abuse doth haunt,

What man grafts in a tree dissimulation.

Each state must have its policies:

Kingdoms have edicts, cities have their charters.

Ev'n the wild outlaw, in his forest walk,

Keeps yet some touch of civil discipline.

For not since Adam wore his verdant apron,

Hath man with man in social union dwelt,

But laws were made to draw that union closer.

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.

Lady Morgan, in her Book of the Boudoir, says, "The late Marquess of Londonderry was a liveable, cheerful, give-and-take person." Again, "Vitality, or all-a-live-ness, energy, and activity, are the great elements of what we call talent;" which occasions a critic to observe, "What a prodigious quantity of this "all-a-liveness" her ladyship must have in her composition."

What burns to keep a secret?—Sealing Wax.

When is wine like a pig's tusk?—When it is in a hogs head.

The young Duke of Rutland, when Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, in a drunken frolic knighted the landlord of an inn in a country town. Being told the next morning what he had done, the duke sent for mine host, and begged of him to consider the ceremonial as merely a drunken frolic. "For my own part, my lord duke, I should readily comply with your excellency's wish; but Lady O'Shannessy!"

N.B. The figures are to be pronounced in French, as un, deux, trois, &c.

Ses vertus le feront admiré de chac 1

Il avait des Rivaux, mais il triompha 2

Les Batailles qu' il gagna sont au nombre de 3

Pour Louis son grand coeur se serait mis en 4

En amour, c'était peu pour lui d'aller à 5

Nous l'aurions s'il n'eut fait que le berger Tir3 6

Pour avoir trop souvent passé douze, "Hic-ja" 7

Il a cessé de vivre en Decembre 8

Strasbourg contient son corps dans un Tombeau tout 9

Pour tant de "Te Deum" pas un "De profun"4 10

——

He died at the age of 55

A lady consulted St. Francis of Sales on the lawfulness of using rouge. "Why," says he, "some pious men object to it; others see no harm in it; I will hold a middle course, and allow you to use it on one cheek."

The prevailing fashion of certain orators interlarding their speeches with frequent classical quotations, reminds us of a piece of mischievous waggery perpetrated by one of the greatest men of his time. Sheridan once electrified the country gentlemen in the House of Commons, by concluding an animated appeal to their patriotism, with a quotation from Herodotus, which they cheered most vociferously; when, in fact, he merely strung together a jumble of words, a jargon uttered on the instant, which sounded very much like Greek. Pitt, it is said, was in a convulsion of laughter all the time.

There is not a word of news stirring. Yesterday's papers may serve for to-day's, and Sunday's for all the week. There is, as it were, a syncope in all things; nothing is doing; art, science, and business, are alike at a stand-still. The stage, the press, the easel, the loom, the rudder of the merchantman, and the helm of the state, all are alike in a most extraordinary negative condition. The world is in a catalepsy. It hears and sees, but it can do nothing.—Blackwood.

g. d.

Mackenzie's Man of Feeling 0 6

Paul and Virginia 0 6

The Castle of Otranto 0 6

Almoran and Hamet 0 6

Elizabeth, or the Exiles of Siberia 0 6

The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne 0 5

Rasselas 0 8

The Old English Baron 0 8

Nature and Art 0 8

Goldsmith's Vicar of Wakefield 0 10

Sicilian Romance 1 0

The Man of the World 1 0

A Simple Story 1 4

Joseph Andrews 1 6

Humphry Clinker 1 8

The Romance of the Forest 1 8

The Italian 2 0

Zeluco, by Dr. Moore 2 6

Edward, by Dr. Moore 2 6

Roderick Random 2 6

The Mysteries of Udolpho 3 6

Peregrine Pickle 4 6

Footnote 1: (return)From an old Vestry-book belonging to St. Michael's we also learn the rents of the shops, which were at first only forty shillings, in the course of a few years were raised to four marks; afterwards to four pounds, and after the fire they were let at ten shillings per foot.

Footnote 4: (return)A great personage of the day remarked, that it was a pity after the marshal had by his victories been the cause of so many "Te Deums" that it would not be allowed (the marshal dying in the Lutheran faith) to chant one "de profundis" over his remains.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.