Title: The Lost Trail

Author: Edward Sylvester Ellis

Release date: February 1, 2004 [eBook #11151]

Most recently updated: December 23, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Wilelmina Mallière and Project Gutenberg Distributed Proofreaders

E-text prepared by Wilelmina Mallière

and Project Gutenberg Distributed Proofreaders

| Note: |

Project Gutenberg also has another text file version of

this book from a different source. See etext04/lstrl10.txt or etext04/lstrl10.zip: http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/etext04/lstrl10.txt or http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/etext04/lstrl10.zip |

NEW YORK HURST & COMPANY PUBLISHERS

"A purty question, ye murtherin haythen!"

"Where does yees get the jug?"

Dealt the savage a tremendous blow

"Well, At-to-uck," said he, kindly, "you seem troubled."

"And so, Teddy, ye're sayin' it war a white man that took away the missionary's wife."

"It's all up!" muttered the dying man. "I am wiped out at last, and must go under!"

"Harvey Richter—don't you know me?" he gasped.

One day in the spring of 1820, a singular occurrence took place on one of the upper tributaries of the Mississippi.

The bank, some fifteen or twenty feet in height, descended quite abruptly to the stream's edge. Though both shores were lined with dense forest, this particular portion possessed only several sparse clumps of shrubbery, which seemed like a breathing-space in this sea of verdure—a gate in the magnificent bulwark with which nature girts her streams. This green area commanded a view of several miles, both up and down stream.

Had a person been observing this open spot on the afternoon of the day in question, he would have seen a large bowlder suddenly roll from the top of the bank to bound along down the green declivity and fall into the water with a loud splash. This in itself was nothing remarkable, as such things are of frequent occurrence in the great order of things, and the tooth of time easily could have gnawed away the few crumbs of earth that held the stone in poise.

Scarcely five minutes had elapsed, however, when a second bowlder rolled downward in a manner precisely similar to its predecessor, and tumbled into the water with a rush that resounded across and across from the forest on either bank.

Even this might have occurred in the usual course of things. Stranger events take place every day. The loosening of the first stone could have opened the way for the second, although a suspicious observer might naturally have asked why its fall did not follow more immediately.

But, when precisely the same interval had elapsed, and a third stone followed in the track of the others, there could be no question but what human agency was concerned in the matter. It certainly appeared as if there were some intent in all this. In this remote wilderness, no white man or Indian would find the time or inclination for such child's play, unless there was a definite object to be accomplished.

And yet, scrutinized from the opposite bank, the lynx-eye of a veteran pioneer would have detected no other sign of the presence of a human being than the occurrences that we have already narrated; but the most inexperienced person would have decided at once upon the hiding-place of him who had given the moving impulse to the bodies.

Just at the summit of the bank was a mass of shrubbery of sufficient extent and density to conceal a dozen warriors. And within this, beyond doubt, was one person, at least, concealed; and it was certain, too, that from his hiding-place, he was peering out upon the river. Each bowlder had emerged from this shrubbery, and had not passed through it in its downward course; so that their starting-point may now be considered a settled question.

Supposing one to have gazed from this stand-point, what would have been his field of vision? A long stretch of river—a vast, almost interminable extent of forest—a faint, far-off glimpse of a mountain peak projected like a thin cloud against the blue sky, and a solitary eagle that, miles above, was bathing his plumage in the clear atmosphere. Naught else?

Close under the opposite shore, considerably lower down than the point to which we first directed our attention, may be descried a dark object. It is a small Indian canoe, in which are seated two white men and a female, all of whom are attired in the garb of civilization. The young man near the stern is of slight mold, clear blue eye, and a prepossessing countenance. He holds a broad ashen paddle in his hand with which to assist his companion, who maintains his proximity to the shore for the purpose of overcoming more deftly the opposition of the current. The second personage is a short but square-shouldered Irishman, with massive breast, arms like the piston-rods of an engine, and a broad, good-natured face. He is one of those beings who may be aptly termed "machines," a patient, plodding, ox-like creature who takes to the most irksome labor as a flail takes to the sheafs on the threshing-floor. Work was his element, and nothing, it would seem, could tire or overcome those indurated muscles and vice-like nerves. The only appellation with which he was ever known to be honored was that of "Teddy."

Near the center of the canoe, which was of goodly size and straight, upon a bed of blankets, sat the wife of the young man in the stern. A glance would have dissipated the slightest suspicion of her being anything other than a willing voyager upon the river. There was the kindling eye and glowing cheek, the eager look that flitted hither and yon, and the buoyant feeling manifest in every movement, all of which expressed more of enthusiasm than of willingness merely. Her constant questions to her husband or Teddy, kept up a continual run of conversation, which was now, for the first time, momentarily interrupted by the occurrence to which we have alluded.

At the moment we introduce them the young man was holding his paddle stationary and gazing off toward his right, where the splash in the water denoted the fall of the third stone. His face wore an expression of puzzled surprise, mingled with which was a look of displeasure, as if he were "put out" at this manifestation. His eyes were fixed with a keen, searching gaze upon the river-bank, expecting the appearance of something more.

Teddy also was resting upon his paddle, and scrutinizing the point in question; but he seemed little affected by what had taken place. His face was as expressionless as one of the bowlders, save the ever-present look of imperturbable good-humor.

The young woman seemed more absorbed than either of her companions, in attempting to divine this mystery that had so suddenly come upon them. More than once she raised her hand, as an admonition for Teddy to preserve silence. Finally, however, his impatience got the better of his obedience, and he broke the oppressive stillness.

"And what does ye make of it, Miss Cora, or Master Harvey?" he asked, after a few moments, dipping his paddle at the same time in the water. "Arrah, now, has either of ye saan anything more than the same bowlders there?"

"No," answered the man, "but we may; keep a bright look-out, Teddy, and let me know what you see."

The Irishman inclined his head to one side, and closed one eye as if sighting an invisible gun. Suddenly he exclaimed, with a start:

"I see something now, sure as a Bally-ma-gorrah wake."

"What is it?"

"The sun going down in the west, and tilling us we've no time to shpare in fooling along here."

"Teddy, don't you remember day before yesterday when we came out of the Mississippi into this stream, we observed something very similar to this?"

"An' what if we did, zur? Does ye mane to say that a rock or two can't git tired of layin' in bed for a thousand years and roll around like a potaty in a garret whin the floor isn't stiddy?"

"It struck us as so remarkable that we both concluded it must have been caused purposely by some one."

"Me own opinion was, ye remember, that it was a lot of school-boys that had run away from their master, and were indulging themselves in a little shport, or that it was the bears at a shindy, or that it was something else."

"Ah! Teddy, there are times when jesting is out of place," said the young wife, reproachfully; "and it seems to me that when we are alone in this vast wilderness, with many and many a long mile between us and a white settlement, we should be grave and thoughtful."

"I strives to be so, Miss Cora, but it's harder than paddling this cockle-shell of a canoe up-shtream. My tongue will wag jist as a dog's tail when he can't kape it still."

The face of the Irishman wore such a long, woebegone expression, that it brought a smile to the face of his companion. Teddy saw this, and his big, honest blue eyes twinkled with humor as he glanced upward from beneath his hat.

"I knows yees prays for me, Misther Harvey and Miss Cora, ivery night and morning of your blessed life, but I'm afeard your prayers will do as little good for Teddy as the s'arch-warrant did for Micky, the praist's boy, who stole the praist's shirt and give it away because it was lou—"

"Look!"

From the very center of the clump of bushes of which we have made mention, came a white puff of smoke, followed immediately by the faint but sharp report of a rifle. The bullet's course could be seen as it skipped over the surface of the water, and finally dropped out of sight.

"What do you say, now?" asked the young man. "Isn't that proof that we've attracted attention?"

"So it saams; but, little dread need we have of disturbance if they always kaap at such a respictable distance as that. Whisht, now! but don't ye saa those same bushes moving? There's some one passing through them! Mebbe it's a shadow, mebbe it's the divil himself. If so, here goes after the imp!"

Catching up his rifle, Teddy discharged it toward the bank, although it was absolutely impossible for his bullet to do more than reach the shore.

"That's to show the old gintleman we are ready and ain't frightened, be he the divil himself, or only a few of his children, that ye call the poor Injuns!"

"And whoever it is, he is evidently as little frightened as you; that shot was a direct challenge to us."

"And it's accepted. Hooray! Now for some Limerick exercise!"

Ere he could be prevented, the Irishman had headed his canoe across stream, and was paddling with all his might toward the spot from which the first shot had been fired.

"Stop!" commanded his master. "It is fool-hardiness, on a par with your general conduct, thus to run into an undefined danger."

Teddy reluctantly changed the course of the boat and said nothing, although his face plainly indicated his disappointment. He had not been mistaken, however, in the supposition that he detected the movements of some person in the shrubbery. Directly after the shot had been fired, the bushes were agitated, and a gaunt, grim-visaged man, in a half-hunter and half-civilized dress, moved a few feet to the right, in a manner which showed that he was indifferent as to whether or not he was observed. He looked forth as if to ascertain the result of his fire. The man was very tall, with a face by no means unhandsome, although it was disfigured by a settled scowl, which better befitted a savage enemy than a white friend. He held his long rifle in his right hand, while he drew the shrubbery apart with his left, and looked forth at the canoe.

"I knew the distance was too great," he muttered, "but you will hear of me again, Harvey Richter. I've had a dozen chances to pick you off since you and your friends started up-stream, but I don't wish to do that. No, no, not that. Fire away; but you can do me no more harm than I can you, at this moment."

Allowing the bushes to resume their wonted position, the stranger deliberately reloaded his piece and as deliberately walked away in the wood.

In the meantime, the voyagers resumed their journey and were making quite rapid progress up-stream. The sun was already low in the sky, and it was not long before darkness began to envelop wood and stream. At a sign from the young man, the Irishman headed the canoe toward shore. In a few moments they landed, where, if possible, the wood was more dense than usual. Although quite late in the spring, the night was chilly, and they lost no time in kindling a good fire.

The travelers appeared to act upon the presumption that there were no such things as enemies in this solitude. Every night they had run their boat in to shore, started a fire, and slept soundly by it until morning, and thus far, strange as it may seem, they had suffered no molestation and had seen no signs of ill-will, if we except the occurrences already related. Through the day, the stalwart arms of Teddy, with occasional assistance from the more delicate yet firm muscles of Harvey, had plied the paddle. No attempt at concealment was made. On several occasions they had landed at the invitation of Indians, and, after smoking, and presenting them with a few trinkets, had departed again, in peace and good-will.

Not to delay information upon an important point, we may state that Harvey Richter was a young minister who had recently been appointed missionary to the Indians. The official members of his denomination, while movements were on foot concerning the spiritual welfare of the heathen in other parts of the world, became convinced that the red-men of the American wilds were neglected, and conceding fully the force of the inference drawn thence, young men were induced to offer themselves as laborers in the savage American vineyard. Great latitude was granted in their choice of ground—being allowed an area of thousands upon thousands of square miles over which the red-man roamed in his pristine barbarism. The vineyard was truly vast and the laborers few.

While his friends selected stations comparatively but a short distance from the bounds of civilization, Harvey Richter decided to go to the Far Northwest. Away up among the grand old mountains and majestic solitudes, hugging the rills and streams which roll eastward to feed the great continental artery called the Mississippi, he believed lay his true sphere of duty. Could the precious seed be deposited there, if even in a single spot, he was sure its growth would be rapid and certain, and, like the little rills, it might at length become the great, steadily-flowing source of light and life.

Harvey Richter had read and studied much regarding the American aborigines. To choose one of the wildest, most untamed tribes for his pupils, was in perfect keeping with his convictions and his character for courage. Hence he selected the present hunting-grounds of the Sioux, in upper Minnesota. Shortly before he started he was married to Cora Brandon, whose devotion to her great Master and to her husband would have carried her through any earthly tribulations. Although she had not urged the resolution which the young minister had taken, yet she gladly gave up a luxurious home and kind friends to bear him company.

There was yet another whose devotion to the young missionary was scarcely less than that of the faithful wife. We refer to the Irishman, Teddy, who had been a favorite servant for many years in the family of the Richters. Having fully determined on sharing the fortunes of his young master, it would have grieved his heart very deeply had he been left behind. He received the announcement that he was to be a life-long companion of the young man, with an expression at once significant of his pride and his joy.

"Be jabers, but Teddy McFadden is in luck!"

And thus it happened that our three friends were ascending one of the tributaries of the upper Mississippi on this balmy day in the spring of 1820. They had been a long time on the journey, but were now nearing its termination. They had learned from the Indians daily encountered, the precise location of the large village, in or near which they had decided to make their home for many and many a year to come.

After landing, and before starting his fire, Teddy pulled the canoe up on the bank. It was used as a sort of shelter by their gentler companion, while he and his master slept outside, in close proximity to the camp-fire. They possessed a plentiful supply of game at all times, for this was the Paradise of hunters, and they always landed and shot what was needed.

"We must be getting well up to the northward," remarked the young man, as he warmed his hands before the fire. "Don't you notice any difference in the atmosphere, Cora?"

"Yes; there is a very perceptible change."

"If this illigant fire only keeps up, I'm thinking there'll be a considerable difference afore long. The ways yees be twisting and doubling them hands, as if ye had hold of some delightsome soap, spaaks that yees have already discovered a difference. It is better nor whisky, fire is, in the long run, providin' you don't swaller it—the fire, that is."

"Even if swallowed, Teddy, fire is better than whisky, for fire burns only the body, while whisky burns the soul," answered the minister.

"Arrah, that it does; for I well remimbers the last swig I took a'most burnt a hole in me shirt, over the bosom, and they say that is where the soul is located."

"Ah, Teddy, you are a sad sinner, I fear," laughingly observed Mrs. Richter, at this extravagant allusion.

"A sad sinner! Divil a bit of it. I haven't saan the day for twinty year whin I couldn't dance at me grandmother's wake, or couldn't use a shillalah at me father's fourteenth weddin'. Teddy sad? Well, that is a—is a—a mistake," and the injured fellow further expressed his feelings by piling on the fuel until he had a fire large enough to have roasted a battalion of prize beeves, had they been spitted before it.

Darkness at length fairly settled upon the wood and stream; the gloom around became deep and impressive. The inevitable haunch of venison was roasting before the roaring fire, Teddy watching and attending it with all the skill of an experienced cook. While thus engaged, the missionary and his wife were occupied in tracing the course of the Mississippi and its tributaries upon a pocket map, which was the chief guide in that wilderness of streams and "tributaries." Who could deny the vastness of the field, and the loud call for laborers, when such an immense extent then bore only the name of "Unexplored Region!" And yet, this same headwater territory was teeming with human beings, as rude and uncultivated as the South Sea Islanders. What were the feelings of the faithful couple as their eyes wandered to the left of the map, where these huge letters confronted them, we can only surmise. That they felt that ten thousand self-sacrificing men could be employed in this portion of the country we may well imagine.

As the evening meal was not yet ready, the missionary folded the map and fell to musing—musing of the future he had marked out for himself; enjoying the sweet approval of his conscience, higher and purer than any enjoyment of earth. All at once came back the occurrence of the afternoon, which had been absent from his thoughts for the hour past. But, now that it was recalled, it engaged his mind with redoubled force.

Could he be assured that it was a red-man who had fired the shot, the most unpleasant apprehension would be dissipated; but a suspicion would haunt him, in spite of himself, that it was not a red-man, but a white, who had thus signified his hostility. The rolling of the stones must have been simply to call his attention, and the rifle-shot was intended for nothing more than to signify that he was an enemy.

And who could this enemy be? If a hunter or an adventurer, would he not naturally have looked upon any of his own race, whom he encountered in the wilderness, as his friends, and have hastened to welcome them? What could have been more desirable than to unite with them in a country where whites were so scarce, and almost unknown? Was it not contrary to all reason to suppose that a hermit or misanthrope would have penetrated thus far to avoid his brother man, and would have broken his own solitude by thus betraying his presence?

Such and similar were the questions Harvey Richter asked himself again and again, and to all he was able to return an answer. He had decided who this strange being might possibly be. If it was the person suspected, it was one whom he had met more frequently than he wished, and he prayed that he might never encounter him again in this world. The certainty that the man had dogged him to this remote spot in the West; that he had patiently plodded after the travelers for many a day and night; that even the trackless river had not sufficed to place distance between them; that, undoubtedly, like some wild beast in his lair, he had watched Richter and his companions as they sat or slumbered near their camp-fire—these, we may well surmise, served to render the missionary for the moment excessively uncomfortable, and to dull the roseate hues in which he had drawn the future.

The termination of this train of thought was the sudden suspicion that this very being was at that moment in close proximity. Unconsciously, Harvey rose to the sitting position and looked around, half expecting to descry the too well remembered figure.

"Supper is waiting, and so is our appetites, be the same token in your stomachs that is in mine. How bees it with yourself, Mistress Cora?"

The young wife had risen to her feet, and the husband was in the act of doing the same, when the sharp crack of a rifle broke the stillness, and Harvey plainly heard and felt the whiz of the bullet as it passed before his eyes.

"To the devil wid yer nonsense!" shouted Teddy, furiously springing forward, and glaring around him in search of the author of the well-nigh fatal shot. Deciding upon the quarter whence it came, he seized his ever-ready rifle, which he had learned to manage with much skill, dashed off at the top of his speed, not heeding the commands of his master, nor the appeals of Mrs. Richter to return.

Guided only by his blind rage, it happened, in this instance, that the Irishman proceeded directly toward the spot where the hunter had concealed himself, and came so very near that the latter was compelled to rise to his feet to escape being trampled upon. Teddy caught the outlines of a tall form tearing hurriedly through the wood, as if in terror of being caught, and he bent all his energies toward overtaking him. The gloom of the night, that had now fairly descended, and the peculiar topography of the ground, made it an exceedingly difficult matter for both to keep their feet. The fugitive, catching in some obstruction, was thrown flat upon his face, but quickly recovered himself. Teddy, with a shout of exultation, sprung forward, confident that he had secured their persecutor at last, but the Irishman was caught by the same obstacle and "floored" even more completely than his enemy.

"Bad luck to it!" he exclaimed, frantically scrambling to his feet, "but it has knocked me deaf and dumb. I'll have ye, owld haythen, yit, or me name isn't Teddy McFadden, from Limerick downs."

Teddy's fall had given the fugitive quite an advantage, and as he was fully as fleet of foot as the Irishman, the latter was unable to regain his lost ground. Still, it wasn't in his nature to give in, and he dashed forward as determinedly as ever. To his unutterable chagrin, however, it was not long before he realized that the footsteps of his enemy were gradually becoming more distant. His rage grew with his adversary's gradual escape, and he would have pursued had he been certain of rushing into destruction itself. All at once he made a second fall, and, instead of recovering, went headlong down into a gully, fully a dozen feet in depth.

Teddy, stunned by his heavy fall, lay insensible for some fifteen or twenty minutes. He returned to consciousness with a ringing sensation in his ears, and it was some time before he could recall all the circumstances of his predicament. Gradually the facts dawned upon him, and he listened. Everything was oppressively still. He heard not the voice of his master, and not even the sound of any of the denizens of the wood.

His first movement was to feel for his rifle, which he had brought with him in his descent, and which he found close at hand. In the act of rising, he caught the sound of a footstep, and saw, at the same instant, the outlines of a person that he knew at once could be no other than the man whom he had been pursuing. The hunter was about a dozen feet distant, and seemed perfectly aware of the Irishman's presence, for he stood with folded arms, facing his pursuer. The darkness prevented Teddy's discovering anything more than his enemy's outline But this was enough for a shot to do its work. Teddy cautiously brought his rifle to his shoulder, and lifted the hammer. Pointing it at the breast of his adversary, so as to be sure of his aim, he pulled the trigger, but there was no response. The gun either was unloaded, or had been injured by its rough usage. The dull click of the lock reached the ear of the target, who asked, in a low, gruff voice:

"Why do you seek me? You and I have no quarrel."

"A purty question, ye murtherin' haythen! I'll settle with yees, if yees only come down here like a man. Jist play the wolf and belave me a sheep, and come down here for your supper."

"My quarrel is not with you, I tell you, but with your psalm-singing master—"

"And ain't that meself?" interrupted Teddy. "What's mine is his, and what's his is mine, and what's me is both, and what's both is me, barring neither one is my own, but all belong to Master Harvey, and Miss Cora, God bless their souls. Don't talk of quarreling wid him and being friendly to me, ye murtherin' spalpeen! Jist come down here a bit, I say, if ye's got a spick of honor in yer rusty shirt."

"My ill-will is not toward you, although, I repeat, if you step in my way you may find it a dangerous matter. You think I tried to shoot you, but you are mistaken. Do you suppose I could have come as near and missed without doing so on purpose? To-night I could have brought you and your master, or his wife, and sent you all out of the world in a twinkling. I've roamed the woods too long to miscarry at a dozen yards."

Teddy began to realize that the man told the truth, yet it cannot be said that his anger was abated, although a strong curiosity mingled with it.

"And what's yer raison for acting in that shtyle, to as good a man as iver asked God's blessing on a sunny morning, and who wouldn't tread on one of yer corns, that is, if yer big feet isn't all corns, like a toad's back, as I suspict, from the manner in which ye leaps over the ground."

"He knows who I am, and he knows he has given me good cause to remind him of my existence. He can tell you, if he chooses; I shall not. But let yourself and him take warning from what you already know."

"And be the same token, let yourself be taking warning. As sure as I'm the ninth son of the seventh mother, I'll—"

The hunter was gone!

With extreme difficulty, Teddy made his way out of the ravine into which purposely he had been led by the hunter. He was full of aches and pains when he attempted to walk, and more than once was compelled to halt to ease his bruised limbs.

As he painfully made his way back to the camp he did a vast deal of cogitation. When in extreme pain of body, produced by a mishap intentionally conceived by another, it is but following the natural law of cause and effect to feel a certain degree of exasperation toward the evil-doer; and, as the Irishman at every step experienced a sharp twinge that ofttimes made him cry out, his ejaculations were neither conceived in charity nor uttered in good-will toward all men. Still, he pondered deeply upon what the hunter had said, and was perplexed to know what could possibly be its meaning.

The simple nature of the Irishman was unable to fathom the mystery. He could not have believed even had Harvey Richter himself confessed to having perpetrated a crime or a wrong, that the minister had been guilty of anything sufficient to give cause of enmity. The strange hunter whom they had unexpectedly encountered several times, must be some crack-brained adventurer, the victim of a fancied wrong, who, most likely, had mistaken Harvey Richter for another person.

What could be the object in firing at the missionary, yet taking pains that no harm should be inflicted? That was another impenetrable mystery; but, let it be comprehensible or not, the wrathful servitor inwardly vowed that, if the man crossed the path of himself or his master again, and the opportunity offered, he should shoot him down as he would a wild animal.

In the midst of his absorbing reverie, Teddy suddenly paused and looked around him. He was lost. Shrewd enough to understand that to attempt to extricate himself would only lead into a greater entanglement, from which it might not be possible to escape at all, he wisely concluded to remain where he was until daylight. Gathering a few twigs and leaves, with his well-stored "punk-box" he soon started a small fire, by the light of which he collected a sufficient quantity of fuel to last until morning.

Few scenes of nature are more impressive than a forest at night. That low deep roar, born of silence itself—the sad sighing of the wind—the tall, column-like trunks, resembling huge sentinels keeping guard over the mysteries of ages—the silent sea of foliage overhead, that seems to shut in a world of its own—all have an influence, peculiar, irresistible and sublime.

The picket upon duty is a prey to many an imaginary danger. The rustling of a leaf, the crackling of a twig, the flitting shadows of the ever-changing clouds, are made to assume the guise of a foe, endeavoring to steal upon him unawares. Again and again Teddy was certain he heard the stealthy tread of the strange hunter, or some prowling Indian, and his heart throbbed violently at the expected encounter. Then, as the sound ceased, a sense of his utter loneliness came over him, and he pined for his old home in the States, which he had so lately left.

A tremulous wail, which came faintly through the silence of the boundless woods, reminded him that there were other inhabitants of the solitude besides human beings. At such times, he drew nearer to the fire, as a child would draw near to a friend to shun an imaginary danger.

But, finally the drowsy god asserted himself, and the watcher passed off into a deep slumber. His last recollection was a dim consciousness of hearing the tread of something near the camp-fire. But his stupor was so great that he had not the inclination to arouse himself, and with his face buried in the leaves of his bushy couch, he quickly lost cognizance of all things, and floated off into the illimitable realms of sleep—Sleep, the sister of Death.

He came out of his heavy slumber from feeling something snuffing and clawing at his shoulder. He was wide awake at once, and all his faculties, even to his anger, were aroused.

"Git out, ye owld sarpent!" he shouted, springing to his feet. "Git out, or I'll smash yer head the same as I smashed the assassin's, barring I didn't do it!"

The affrighted animal leaped back several yards, as lightly as a shadow. Teddy caught only a glimpse of the beast, but could plainly detect the phosphorescent glitter of his angry eyes, that watched every movement. The Irishman's first proceeding was to replenish the fire. This kept the creature at a safe distance, although he began trotting around and around, as if to seek some unguarded loophole through which to compass the destruction of the man who had thus invaded his dominions.

The tread of the animal resembled the rattling of raindrops upon the leaves, while its silence, its gliding motion, convinced the inexperienced Irishman of the brute's exceedingly dangerous character. His rifle was too much injured to be of use and he could therefore only keep his precocious foe at a safe distance by piling on fuel until the camp-fire burned defiantly.

There was no more sleep for Teddy that night. He had received too great a shock, and the impending danger was too imminent for him to do any thing but watch, so long as darkness and the animal remained. Several times he thought there was evidence of the presence of another beast, but he failed to discover it, and finally believed he had been mistaken.

It was a tiresome and lonely occupation, this incessant watching, and Teddy had recourse to several expedients to while away the weary hours. The first and most natural was that of singing. He trolled forth every song that he could recall to remembrance, and it may be truly said that he awoke echoes in those forest-aisles never before heard there. As in the pauses he heard the volume of sound that seemed quivering and swaying among the tree-trunks, like the confined air in an organ, he was awed into silence.

"Whist, ye son of Patrick McFadden; don't ye hear the responses all around ye, as if the spirits were in the organ loft, thinkin' ye a praist and thimselves the choir-boys. I belaves, by me sowl, that ivery tree has got a tongue, for hear how they whispers and mutters. Niver did I hear the likes. No more singin', Teddy my darlint, to sich an audience."

He thereupon relapsed into silence, but it was only momentary. He suddenly looked out into the darkness which shrouded the still watchful beast from sight, and exclaimed:

"Ye owld shivering assassin, out there, did yees ever hear till how Tom O'Reilly got his wife? Yees never did, eh? Well, then, be aisy now, and I'll give yees the truths of the matter.

"Tom was a great, rollicking boy, that had an eye gouged out at the widow Mulloney's wake, and an ugly cut that made his mouth six inches wide: and, before he got the cut, it was as broad as yer own out there. Besides, his hair being of a fire's own red, you may safely say that he was not the most beautiful young man in Limerick, and that there wasn't many gals that were dying of a broken heart for the same Tom.

"But Tom thought a mighty sight of the gals and a great deal more of Kitty McGuire, that lived close by the brook as yees come a mile or two out of this side of Limerick. Tom was possessed after that same gal, and it only made him the more determined when he found that Kitty didn't like him at all. He towld the boys he was bound to have her, and any one who said he wasn't would get his head broke.

"There was a little orphan girl, whose father had gone to Ameriky and whose mother was dead, that was found one night, years before, in front of old Mrs. McGuire's door. She was about the same age as Kitty, and the owld woman took her out of kindness and brought them up together. She got to be jist as ugly a looking a gal as Tom was a man. Her hair was redder than his, and her face was just that freckled that yees couldn't tell which was the freckle and which was the skin itself. And her nose had a twist, on the ind of it, that made one think it had been made for a corkscrew, or some machine that you bore holes with.

"This gal, Molly Mulligan, used to encourage Tom to come to the house, and was always so mighty kind to him that he used to kiss and shpark her by way of compinsating her for her trouble. She used to take this all very well, for she was a great admirer of Tom's, and always spoke his praise. But Tom didn't make much headway with Kitty. It wasn't often that he could saa her, and when he did; she was mighty offish, and was sure to have the owld woman present, like a dumb-waiter, to be sure. She come to tell him at length that she didn't admire his coming, and that he would greatly plaise her if he would make his visits by staying away altogether. The next time Tom went he found the door locked, and, after hammering a half-hour, and being towld there was no admittance, he belaved it was meant as a kind hint that his company was not agreeable. Be yees listening, ye riptile?

"Tom might have stood it very well, if another chap hadn't begun calling on Kitty about this time. He used to go airly in the evening, and not come out of the house till after midnight, so that one might belave his visits were welcome. This made Tom feel mighty bad, and so he hid behind the wall and waylaid the chap one night. He would have killed the chap, his timper was so ruffled, if the man hadn't nearly killed him afore he had the chance. He laid all night in the gutter, and was just able to crawl home next day, while the fellow went a-courting the next night, as if nothing had happened.

"Tom begun to git melancholy, and his mouth didn't appear quite as broad as usual. Molly Mulligan thought he had taken slow poison and it was gradually working through his system; but he could ate his pick of praties the same as iver. But Tom felt mighty bad; that fact can't be denied, and he went frequently to consult with a praist that lived near this ind of Limerick, and who was knowed to cut up a trick or two during his lifetime. When Tom came out one day looking bright and cheery, iverybody belaved they had been conspiring togither, and had hit on some thavish trick they was to play on little Kitty McGuire.

"When the moon was bright, Kitty used to walk to Limerick and back again of an evening. Her beau most likely went with her, but sometimes she preferred to go alone, as she knowed no one would hurt a bonny little gal as herself. Tom knowed of these doings, as in days gone by he had jined her once or twice. So one night he put a white sheet around him as she was coming back from Limerick, and hid under the little bridge over the brook. It was gitting quite late, and the moon was just gone down, so, when she stepped on the bridge, and he came out afore her, she gave one shriek, and like to have fainted intirely.

"'Make no noise, or I'll ate ye up alive,' said Tom, trying to talk like a ghost.

"'What isht yees want?' she asked, shaking like a leaf, 'and who are yees?'

"'I'm a shpirit, come to warn ye of your ill-doings.'

"'I know I'm a great sinner,' she cried, covering her face with her hands; 'but I try to do as well as I can.'

"'Do you know Tom O'Reilly?' he asked, loud enough to be heard in Limerick. 'You have treated him ill.'

"'That I know I have,' she sobbed, 'and how can I do him justice?'

"'He loves you.'

"'I know he does!'

"'He is a shplendid man, and will make a much bitter husband than the spalpeen that ye now looks on with favor.'

"'Shall I make him my husband?'

"'Yis; if ye wish to save yourself from purgatory. If the other man marries yees, he'll murder yees the same night.'

"'Oh!' shrieked the gal, as if she'd go down upon the ground, 'and how shall I save meself?'

"'By marrying Tom O'Reilly.'

"'Is that the only way?'

"'Ay. Does yees consint?'

"'I do; I must do poor Tom justice.'

"'Will ye marry him this same night?'

"'That I will.'

"'Tom is hid under this bridge; I'll go down and bring him up, and he'll go to the praist's with yees. Don't ye shtir or I'll ate yees.'

"So Tom whisked under the ind of the bridge, slipped off the sheet, all the time kaaping one eye cocked above to saa that Kitty didn't give him the shlip. He then came up and spoke very smilingly to the gal, as though he hadn't seen her afore that night. He didn't think that his voice was jist the same.

"Kitty didn't say much, but she walked very quiet by his side, till they came to the praist's house at this ind of Limerick. The owld fellow must have been expecting him, for before he could knock, he opened the door and let him in. The praist didn't wait long, and in five minutes he towld them they were man and wife, and nothing but death could iver make them different. Tom gave a regular yell that made the windys rattle, for he couldn't kaap his faalings down. He then threw his arms around his wife, gave her another hug, and then dropped her like a hot potato. For instead of being Kitty McGuire, it was Molly Mulligan! The owld praist wasn't so bad after all. He had told Kitty and Molly of Tom's plans, and they had fixed the matter atween thim.

"Wal, the praist laughed, and Tom looked melancholier than iver; but purty soon he laughed too, and took the praist's advice to make the bist of the bargain. Whisht!"

Teddy paused abruptly, for he heard a prolonged but faint halloo. It was, evidently, the call of his master, and indicated the direction of the camp. He replied at once, and without thinking one moment of the prowling brute which might be upon him instantly, he passed beyond the protecting circle of his fire, and dashed off at top of his speed through the woods, and ere long reached the camp-fire of his friends. As he came in, he observed that Mrs. Richter still was asleep beneath the canoe, while her husband stood watching beside her. Teddy had determined to conceal the particulars of the conversation he had held with the officious hunter, but he related the facts of his pursuit and mishap, and of his futile attempt to make his way back to camp. After this, the two seated themselves by the fire, and the missionary was soon asleep. The adventures of the night, however, affected Teddy's nerves too much for him even to doze, and he therefore maintained an unremitting watch until morning.

At an early hour, our friends were astir, and at once launched forth upon the river. They noted a broadening of the stream and weakening of the current, and at intervals they came upon long stretches of prairie. The canoe glided closely along, where they could look down into the clear depths of the water, and discover the pebbles glistening upon the bottom. Under a point of land, where the stream made an eddy, they halted, and with their fishing-lines, soon secured a breakfast which the daintiest gourmand might have envied. They were upon the point of landing so as to kindle a fire, when Mr. Richter spoke:

"Do you notice that large island in the stream, Cora? Would you not prefer that as a landing-place?"

"I think I should."

"Teddy, we'll take our morning meal there."

The powerful arms of the Irishman sent the frail vessel swiftly over the water, and a moment later its prow touched the velvet shore of the island. Under the skillful manipulations of the young wife, who insisted upon taking charge, their breakfast was quickly prepared, and, one might say, almost as quickly eaten.

They had now advanced so far to the northward that all felt an anxiety to reach their destination. Accordingly no time was lost in the ascent of the stream.

The exhilarating influence of a clear spring morning in the forest, is impossible to resist. The mirror-like sparkle of the water that sweeps beneath the light canoe, or glitters in the dew-drops upon the ashen blade; the golden blaze of sunshine streaming up in the heavens; the dewy woods, flecked here and there by the blossoms of some wild fruit or flower; the cool air beneath the gigantic arms all a-flutter with the warbling music of birds; all conjoin to inspire a feeling which carries us back to boyhood again—to make us young once more.

As Richter sat in the canoe's stern, and drank in the influence of the scene, his heart rose within him, and he could scarcely refrain from shouting. His wife, also, seemed to partake of this buoyancy, for her eyes fairly sparkled as he glanced from side to side. All at once Teddy ceased paddling and pointed to the left shore. Following the direction of his finger, Richter saw, standing upon the bank in full view, the tall, spare figure of the strange hunter. He seemed occupied in watching them, and was as motionless as the tree-trunks behind him—so motionless, indeed, that it required a second scrutiny to prove that it really was not an inanimate object. The intensity of his observation prevented him from observing that Teddy had raised his rifle from the canoe. He caught the click of the lock, however, and spoke in a sharp tone:

"Teddy, don't you dare to—"

His remaining words were drowned in the sharp crack of the piece.

"It's only to frighten him jist, Master Harvey. It'll sarve the good purpose of giving him the idee we ain't afeard, and if he continues his thaiving tricks, he is to be shot at sight, as a shaap-stalin' dog, that he is, to be sure."

"You've hit him!" said his master, as he observed the hunter leap into the woods.

"Thank the Lord for that, for it was an accident, and he'll l'arn we've rifles as well as himself. It's mighty little harm, howiver, is done him, if he can travel in that gay style."

"I am displeased, for your shot might have taken his life, and—but, see yonder, Teddy, what does that mean?"

Close under the opposite bank, and several hundred yards above them was discernible a long canoe, in which was seated at least a dozen Indians. They were coming slowly down-stream, and gradually working their way into the center of the river. Teddy surveyed them a moment and said:

"That means they're after us. Is it run or fight?"

"Neither; they are undoubtedly from the village, and we may as well meet them here as there. What think you, dear wife?"

"Let us join them, by all means, at once."

All doubts were soon removed, when the canoe was headed directly toward them, and under the propulsion of the many skillful arms, it came like a bird over the surface of the waters. A few rods away its speed was slackened, and, before approaching closer, it made a circuit around the voyageurs' canoe, as if the warriors were anxious to assure themselves there was no decoy or design in this unresisting surrender.

Evidently satisfied that it was a bona fide affair, the Indians swept up beside our friends, and one of the warriors, stretching out his hands, said:

"Gib guns me—gib guns."

"Begorrah, but it would be mighty plaisant to us, if it would be all the same to yees, if ye'd be clever enough to let us retain possission of 'em," said Teddy, hesitating about complying with the demand. "They might do ye some injury, ye know, and besides, I didn't propose to—"

"Let them have them," said Richter. The Irishman reluctantly obeyed, and while he passed his rifle over with his left hand, he doubled up his right, shaking it under the savage's nose.

"Ye've got me gun, ye old log of walnut, but ye hain't got me fists, begorrah, but, by the powers, ye shall have them some of these fine mornings whin yer eyes want opening."

"Teddy, be silent!" sharply commanded the missionary.

But the Indians, understanding the significance of the Irishman's gestures, only smiled at them, and the chief who had taken his gun, nodded his head, as much as to say he, too, would enjoy a fisticuff.

When the whites were defenseless, one of the savages vaulted lightly into their canoe, and took possession of the paddle.

"I'm highly oblaiged to ye," grinned Teddy, "for me arms have been waxin' tired ever sin' I l'arned the Injin way of driving a canoe through the water. When ye gets out o' breath jist ax another red-skin to try his hand, while I boss the job."

The canoes were pulled rapidly up-stream. This settled that the whites were being carried to the village which was their original destination. Both Harvey and his wife were rather pleased than otherwise with this, although the missionary would have preferred an interview or conversation in order to make himself and intentions known. He was surprised at the knowledge they displayed of the English language. He overheard words exchanged between them which were as easy to understand as much of Teddy's talk. They must be, therefore, in frequent communication with white men. Their location was so far north that, as Richter plausibly inferred, they were extensive dealers in furs and peltries, which must be disposed of to traders and the agents of the American Fur and Hudson Bay Companies. The Selkirk or Red river settlement also, must be at an easily accessible distance.

It may seem strange that it never occurred to the captives that the savages might do them harm. In fact, nothing but violence itself would have convinced the missionary that such was contemplated. He had yielded himself, heart and soul, to his work; he felt an inward conviction that he was to accomplish great good. Trials and sufferings of all imaginable kinds he expected to undergo, but his life was to be spared until the work was accomplished. Of that he never experienced a moment's doubt.

Our readers will bear in mind that the period of which we write, although but a little more than forty years since, was when the territory west of the Mississippi was almost entirely unknown. Trappers, hunters and fur-traders in occasional instances, penetrated into the heart of the mighty solitude. Lewis and Clarke had made their expedition to the head-waters of the Columbia, but the result of all these visits, to the civilized world, was much the same as that of the adventurers who have penetrated into the interior of Africa.

It was known that on the northwest dwelt the warlike Blackfeet, the implacable foes of every white man. There, also, dwelt other tribes, who seemed resolved that none but their own race should dwell upon that soil. Again, there were others with whom little difficulty was experienced in bartering and trading, to the great profit of the adventurous whites, and the satisfaction of the savages; still, the shrewd traders knew better than to trust to Indian magnanimity or honor. Their reliance under heaven, was their tact in managing the savages, and their own goodly rifles and strong arms. The Sioux were among the latter class, and with them it was destined that the lot of Harvey Richter and his wife should be cast.

The Indian village was reached in the course of a couple of hours. It was found to be much larger than Richter could have anticipated. The missionary soon made known his character and wishes. This secured an audience with the leading chief, when Harvey explained his mission, and asked permission for himself and companions to settle among them. With the ludicrous dignity so characteristic of his people, the chief deferred his reply until the following day, at which time he gave consent, his manner being such as to indicate that he was rather unwilling than otherwise.

That same afternoon, the missionary collected the dusky children of the forest together and preached to them, as best he could, through the assistance of a rude interpreter. He was listened to respectfully by the majority, among whom were several whom he inferred already had heard the word of life. There were others, however, to whom the ceremony was manifestly distasteful. The hopeful minister felt that his Master had directed him to this spot, and that now his real life-work had begun.

A year has passed since the events recorded in the preceding pages, and it is summer again. Far up, beside one of those tributaries of the Mississippi, in the western portion of what is now the State of Minnesota, stands a small cabin, such as the early settlers in new countries build for themselves. About a quarter of a mile further up the stream is a large Sioux village, separated from the hut by a stretch of woods through which runs a well-worn footpath. This arrangement the young missionary, Harvey Richter, preferred rather than to dwell in the Indian village. While laboring with all his heart and soul to regulate these degraded people, and while willing to make their troubles and afflictions his own, he still desired a seclusion where his domestic cares and enjoyments were safe from constant interruption. This explains why his cabin had been erected at such a distance from his people.

Every day, no matter what might be the weather, the missionary visited the village, and each Sabbath afternoon, when possible, service was held. This was almost invariably attended by the entire population, who now listened attentively to what was uttered, and often sought to follow the counsels uttered by the good man. A year's residence had sufficed to win the respect and confidence of the Indians, and to convince the faithful servant that the seed he had sown was already springing up and bearing fruit.

About a mile from the river, in a dense portion of the wood, are seated two persons, in friendly converse. But a glance would be required to reveal that one of these was our old friend Teddy, in the most jovial and communicative of moods. The other, painted and bedaubed until his features were scarcely recognizable, and attired in the gaudy Indian apparel, sufficiently explains his identity. A small jug sitting between them, and which is frequently carried to the mouth of each, may disclose why, on this particular morning, they seemed on such confidential terms. The sad truth was that the greatest drawback to Harvey Richter's ministrations was his own servant Teddy. The Indians could not understand why he who lived constantly with the missionary, should be so careless and reckless, and should remain "without the fold," when the good man exhorted them in such earnest language to become Christians. It was incomprehensible to their minds, and served to fill more than one with a suspicion that all was not what it should be. Harvey had spent many an hour with Teddy, in earnest, prayerful expostulation, but, thus far, to no purpose.

For six months after the advent of the missionary and his wife, nothing had been seen or heard of the strange hunter, when, one cold winter's morning, as the former was returning from the village through the path, a rifle was discharged, and the bullet whizzed within an inch or two of his eyes. He might have believed it to be one of the Indians, had he not secured a fair look at the man as he ran away. He said nothing of it to his wife or Teddy, although it occasioned him much trouble and anxiety of mind.

A month or two later, when Teddy was hunting in the woods, and had paused a moment for rest, a gun was discharged at him, from a thick mass of undergrowth. Certain that the unknown hunter was at hand, he dashed in as before, determined to bring the transgressor to a personal account. Teddy could hear him fleeing, and saw the agitation of the undergrowth, but did not catch even a glimpse of his game.

While prosecuting the search, Teddy suddenly encountered an Indian, staggering along with a jug in his hand. The savage manifested a friendly disposition, and the two were soon seated upon the ground, discussing the fiery contents of the vessel and exchanging vows of eternal friendship. When they separated it was with the understanding that they were to meet again in a couple of days.

Both kept the appointment, and since that unlucky day they had encountered quite frequently. Where the Indian obtained the liquor was a mystery, but it was an attraction that never failed to draw Teddy forth into the forest. The effect of alcoholic stimulants upon persons is as various as are their temperaments. The American Indian almost always becomes sullen, vindictive and dangerous. Now and then there is an exception, as was the case with the new-made friend of Teddy. Both were affected in precisely a similar manner; both were jolly.

"Begorrah, but yees are a fine owld gintleman, if yer face does look like a paint-jug, and ye isn't able to lay claim to one-half the beauty meself possesses. That ye be," said Teddy, a few moments after they had seated themselves, and before either had been affected by the poisonous liquid.

"I loves you!" said the savage, betraying in his manner of speech a remarkable knowledge of the English language. "I think of you when I sleep—I think of you when I open my eyes—I think of you all the time."

"Much obleeged; it's meself that thinks and meditates upon your beauty and loving qualities all the time, barring that in which I thinks of something else, which is about all the time—all the same to yer honor."

"Loves you very much," repeated the savage; "love Mister Harvey, too, and Miss Harvey."

"Then why doesn't ye come to hear him preach, ye rose of the wilderness?"

"Don't like preaching."

"Did yees ever hear him?"

"Neber hear him."

"Yer oughter come; and that minds me I've never saan ye around the village, for which I axes yees the raison?"

"Me ain't Sioux—don't like 'em."

"Whinever yees are discommoded with this jug, p'raps it wouldn't be well for yees to cultivate the acquaintance of any one except meself, for they might be dispoused to relave yees of the article, when yees are well aware it's an aisy matter for us to do that ourselves. Where does yees get the jug?"

"Had him good while."

"I know; but the contents I mean. Where is it ye secures the vallyble contents?"

"Me get 'em," was the intelligent reply..

"That's what I've been supposing, that yees was gitting more nor your share; so here's to prevint," remarked Teddy, as he inverted the jug above his head. "Now, me butternut friend, what 'bjections have yees to that?"

"All right—all be good—like Miss Harvey?"

Teddy stared at the savage, as if he failed to take in his question.

"Like Miss Harvey—good man's squaw—t'ink she be good woman?"

"The loveliest that iver trod the airth—bless her swate soul. She niver has shpoken a cross word to Teddy, for all he's the biggest scamp that iver brought tears to her eyes. If there be any thing that has nigh fotched this ould shiner to his marrowbones it was to see something glistening in her eyes," said the Irishman, as he wiped his own. "God bliss Miss Cora," he added, in the same manner of speech that he had been wont to use before she became a wife. "She might make any man glad to come and live alone in the wilderness wid her. It's meself that ought to be ashamed to come away and l'ave her alone by herself, though I thinks even a wild baste would not harm a hair of her blissid head. If it wasn't for this owld whisky-jug I wouldn't be l'aving her," said Teddy, indignantly.

"How be 'lone?—Mister Harvey dere."

"No, he isn't, by a jug-full—barring the jug must be well-nigh empty, and the divil save the jug, inny-how; but not until it's impty."

"Where Mr. Harvey go, if not in cabin?" asked the savage, betraying a suspicious eagerness that would have been observed by Teddy upon any other occasion.

"To the village, that he may preach and hould converse wid 'em. I allers used to stay at home when he's gone, for fear that owld thaif of a hunter might break into the pantry and shtail our wines—that is, if we had any, which we haven't. Blast his sowl—that hunter I mane, an' if iver I cotch him, may I be used for a flail if I don't settle his accounts."

"When Mister Harvey go to village?"

"Whin he plaises, which is always in the afternoon, whin his dinner has had a fair chance to sittle. Does ye take him for a michanic, who goes to work as soon as he swallows his bread and mate?" said the Irishman, with official dignity.

"Why you not stay with squaw?"

"That's the raison," replied Teddy, imbibing from the vessel beside him. "But you will plaise not call Miss Cora a shquaw any more. If ye does, it will be at the imminent risk of havin' this jug smashed over yer head, afther the whisky is all gone, which it very soon will be if a plug isn't put into your mouth."

"Nice woman—much good."

"You may well say that, Mister Copperskin, and say nothing else. And it's a fine man is Mister Harvey, barring he runs me purty close once in a while on the moral quishtion. I'm afeard I shall have to knock under soon. If I could but slay that thaif of a hunter that has been poking around here, I think I could go the Christian aisy; but whin I thinks of that man, I faals like the divil himself. They's no use tryin' to be pious whin he's around; so pass the jug if ye don't mane to fight meself."

"He bad man—much bad," said the savage, who had received an account of him from his companion.

"I promised Master Harvey not to shoot the villain, excipt it might be to save his life or me own; but I belave if I had the chance, I'd jist conveniently forgit me promise, and let me gun go off by accident. St. Pathrick! wouldn't I like to have a shindy wid the sn'akin, mean, skulkin' assassin!"

"Does he want kill you?"

"Arrah, be aisy now; isn't it me master he's after, and what's the difference? Barring I would rather it was meself, that I might sittle it gintaaly wid him;" and Teddy, "squaring" himself, began to make threatening motions at the Indian's head.

"Bad man—why not like Mr. Harvey?" said the savage, paying no attention to Teddy's demonstrations.

"There yees has me. There's something atween 'em, though what it might be none but Mr. Harvey himself knows, less it mought be the misthress, that I don't belave knows a word on it. But what is it yer business, Mr. Mahogany?"

"Mebbe Mr. Harvey hurt him some time—do bad with him," added the Indian, betraying an evident interest in the subject.

"Begorrah, if yees can't talk better sinse nor that, ye'd bist put a stopper on yer blab. The idaa of me master harming any one is too imposterous to be intertained by a fraa and inlightened people—a fraa and inlightened people, as I used to spell out in the newspapers at home. But whisht! Ye are a savage, as don't know anything about Fourth of July, an' all the other affections of the people."

"You dunno what mebbe he done."

"Do ye know?" asked Teddy, indignantly.

"Nebber know what he do—how me know?"

"Thin what does ye mane by talking in that shtyle? I warns ye, there's some things that can't be passed atween us and that is one of 'em. If ye wants to fight, jist you say that again. I'm aching for a shindy anyhow: so now s'pose ye jist say that again." And Teddy began to show unmistakable signs of getting ready.

"Sorry—didn't mean—feel bad." "Oh blarney! Why didn't ye stick to it, and jist give me a chance to express meself? But all's right; only, be careful and don't say anything like it again, that's all. Pass along the jug, to wash me timper down, ye know."

By this time Teddy's ideas were beginning to be confused, and his manner maudlin. He had imbibed freely, and was paying the consequences. The savage, however, had scarcely taken a swallow, although he had made as if to do so several times. His actions would have led an inexperienced person to think that he was under the influence of liquor; but he was sober, and his conduct was feigned, evidently, for some purpose of his own. Teddy grew boisterous, and insisted on constantly shaking hands and renewing his pledges of eternal friendship to the savage, who received and responded to them in turn. Finally, he squinted toward the westering sun.

"I told Mr. Harvey, when I left, I was going to hunt, and if I expects to return to-day, I thinks, Mr. Black Walnut, we should be on our way. The jug is intirely impty, so there is no occasion for us to remain longer."

"Dat so—me leave him here."

"Now let's shake hands agin afore we rise."

The shaking of hands was all an excuse for Teddy to receive assistance in rising to his feet. He balanced himself a moment, and stared around him, with that aimless, blinking stare peculiar to a drunken man.

"Me honey, isn't there an airthquake agitatin' this solitude?" he asked, steadying himself against a sapling, "or am I standing on a jug?"

"Dunno—mebbe woods shake—feel him a little—earth must be sick," said the savage, feigning an unsteadiness of the head.

"Begorrah, but it's ourselves that's the sickest," laughed Teddy, fully sensible of his sad condition. "It'll niver do to return to Master Harvey in this shtyle. There'd be a committee of investigation appointed on the spot, an' I shouldn't pass muster excipt for a whisky-barrel, och hone!"

"Little sick—soon be well—then shoot."

"I wonder now whether I could howld me gun straight enough to drop a buffler at ten paces. There sits a bird in that tree that is grinning at me. I'll t'ach him bitter manners."

The gun was discharged, the bullet passing within a few inches of the head of the Indian, who sprung back with a grunt.

"A purty good shot," laughed Teddy; "but it would be rayther tiresome killing game, being I could only hit them as run behind me, and being I can't saa in that direction, I'll give over the idaa; and turn me undivided attention to fishing. Ah, divil a bit of difference is it to the fish, whin a worm is on the right ind, whether a drunken man or a gintleman is at the other."

The Indian manifested a readiness to assist every project of the Irishman, and he now advised him to fish by all means, urging that they should proceed to the river at once. But Teddy insisted upon going to a small creek near at hand. The savage strongly demurred, but finally yielded, and the two set out, making their way somewhat after the fashion of a yoke of oxen.

Upon reaching the stream, Teddy, instead of pausing upon the bank, continued walking on until he was splashing up to his waist in water. Had it not been for the prompt assistance of the Indian, the poor fellow most probably would have had his earthly career terminated. This incident partially sobered Teddy, and made him ashamed of his condition. He saw the savage was by no means so far gone as himself, and he bewailed his foolishness in unmeasured terms.

"Who knows but Master Harvey has gone to the village, and Miss Cora stands in the door this minute, 'xpacting this owld spalpaan?"

"No go till arternoon," said the savage.

"What time might it be jist now?"

"'Tain't noon yit—soon be—bimeby."

"It's all the same; I shan't be fit to go home afore night, whin I might bist stay away altogether. And you, Mr. Copperskin, was the maans of gittin' me in this trouble."

"Me make you drink him?" asked the savage. "You not ax for jug, eh? You not want him?"

"Yes, begorrah, it was me own fault. Whisky is me waikness. Its illigant perfume always sits me wild fur it. Mister Harvey was belaving, whin he brought me here, that I wouldn't be drinking any of the vile stuff, for the good rais'n that I couldn't git none; but, what'll he say now? Niver was I drunker at Donnybrook, and only once, an' that was at me father's fourteenth weddin'."

"Don't want more?"

"NO!" thundered Teddy. "I hope I may niver see nor taste another drop so long as I live. I here asserts me ancient honor agin, an' I defy the jug, ye spalpeen of a barbarian what knows no better." Teddy's reassertion of dignity was very ludicrous, for a tree had to support him as he spoke; but he evidently was in earnest.

"Neber gib it—if don't want it."

"They say an Indian never will tell a lie to a friend," said Teddy, dropping his voice as if speaking to himself. "Do you ever lie, Mr. What's-your-name?"

"No," replied the savage, thereby uttering an unmitigated falsehood.

"You give me your promise, then, that ye'll niver furnish me anither drap?"

"Yis."

"Give me yer hand."

The two shook hands, Teddy's face, despite its vacant expression, lighting up for the time with a look of delight.

"Now I'll fish," said Teddy. "P'raps it is best that ye l'ave these parts; not that I intertains inmity or bad-will toward you, but thin ye know----hello! yees are gone already, bees you?"

The Indian had departed, and Teddy turned his attention toward securing the bait. In a few moments he had cast the line out in the stream and was sound asleep, in which condition he remained until night set in.

The sun passed the meridian, on that summer day in 1821 and Harvey Richter, the young missionary, came to the door of his cabin, intending to set forth upon his walk to the Indian village. It was rather early; the day was pleasant and as his wife followed him, he lingered awhile upon the steps, loth to leave a scene of such holy joy.

The year which the two had spent in that wilderness had been one of almost unalloyed happiness. The savages, among whom they had come to labor, had received them more kindly than they deemed it right to anticipate, and had certified their esteem for them in numberless ways. The missionary felt that a blessing was upon his labor.

An infant had been given them, and the little fellow brought nothing but gladness and sunlight into the household. Ah! none but a father can tell how precious the blue-eyed image of his mother was to Harvey Richter; none but a mother can realize the yearning affection with which she bent over the sleeping cherub; and but few can enter into the rollicking pride of Teddy over the little stranger. At times, his manifestations were fairly uproarious, and it became necessary to check them, or to send him further into the woods to relieve himself of his exuberant delight.

Harvey lingered upon the threshold, gazing dreamily away at the mildly-flowing river, or at the woods, through which for a considerable distance, he could trace the winding path which his own feet had worn. Cora, his wife, stood beside him, looking smilingly down in his face, while her left hand toyed with a stray ringlet that would protrude itself from beneath her husband's cap.

"Cora, are you sorry that we came into this wild country?"

The smile on her face grew more radiant, as she shook her head without speaking. She was in that pleasant, dreamy state, in which it seems an effort to speak—so much so that she avoided it until compelled to do so by some direct question.

"You are perfectly contented—happy, are you?"

Again the same smile, as she answered in the affirmative by an inclination of the head.

"You would not change it for a residence at home with your own people if you could?"

The same sweet denial in pantomime.

"Do you not become lonely sometimes, Cora, hundreds of miles away from the scenes of your childhood?"

"Have I not my husband and boy?" she asked, half reproachfully, as the tears welled up in her eyes. "Can I ask more?"

"I have feared sometimes, when I've been in the village, that perhaps you were lonely and sorrowful, and often I have hurried my footsteps that I might be with you a few moments sooner. When preaching and talking to the Indians, my thoughts would wander away to you and the dear little fellow there. And what husband could prevent them?" said Harvey, impulsively, as he drew his wife to him, and kissed her again and again.

"You must think of the labor before you."

"There is scarcely a moment of my life in which I don't, but it is impossible to keep you and him from my mind. I am sorry that I am compelled to leave you alone so often. It seems to me that Teddy has acted in a singular manner of late. He is absent every afternoon. He says he goes hunting and yet he rarely, if ever, brings anything back with him."

"Yesterday he returned shortly after you left, and acted so oddly, I did not know what to make of him. He appeared very anxious to keep me at a distance, but once he came close enough for me to catch his breath, and if it did not reveal the fumes of liquor then I was never more mistaken in my life."

"Impossible! where could he obtain it?"

"The question I asked myself and which I could not answer; nevertheless his manner and the evidence of his own breath proved it beyond all doubt to my mind. You have noticed how set he is every afternoon about going away in the woods. Such was not his custom, and I think makes it certain some unusual attraction calls him forth."

"What can it all mean?" asked the missionary of himself. "No; it cannot be that he brought any of the stuff with him and concealed it in the boat. It must have been discovered."

"Every article that came with us is in this house."

"Then some one must furnish him with it, and who now can it be?"

"Are there not some of your people who are addicted to the use of liquor?"

"Alas! there are too many who cannot withstand the tempter; but I never yet heard of an Indian who knew how to make it. It is only when they visit some of the ports, or the Red river settlement, that they obtain it. Or perhaps a trader may come this way, and bring it with him."

"And could not Teddy have obtained his of such a man?"

"There has been none here since last autumn, and then those who visited the village had no liquor with them. They always come to the village first so that I could not avoid learning of their presence. Let me see, he has been away since morning?"

"Yes; he promised an early return."

"He will probably make his appearance in the course of an hour or so. Watch him closely. I will be back sooner to-day, and we shall probe this matter to the bottom. Good-by!"

Again he embraced his wife, and then strode rapidly across the Clearing in the direction of the woods. His wife watched his form winding in and out among the trees, until it finally disappeared from view; and then, waiting a few moments longer, as if loth to withdraw her gaze from the spot where she had last seen him, she finally turned within the house to engage in her domestic duties.

The thrifty housewife has seldom an idle moment on her hands, and Cora passed hither and thither, performing the numerous little acts that were not much in themselves, but collectively were necessary, if not indispensable, in her household management. Occasionally she paused and bent over her child, that lay sleeping on the bed, and like a fond mother, could not restrain herself from softly touching her lips to its own, although it was at the imminent risk of awaking it.

An hour passed. She went to the door and looked out to see whether Teddy was in sight; but the woods were as silent as if they contained no living thing. Far away over the river, nearly opposite the Indian village, she saw two canoes crossing the stream, resembling ordinary-sized water-birds in the distance. These, so in harmony with the lazy, sunshiny afternoon, were all that gave evidence that man had ever invaded this solitude.

Cora Richter could but be cheerful, and, as she moved to and fro, she sung a hymn, one that was always her husband's favorite. She sung it unconsciously, from her very blithesomeness of spirits, not knowing she was making music which the birds themselves might have envied.

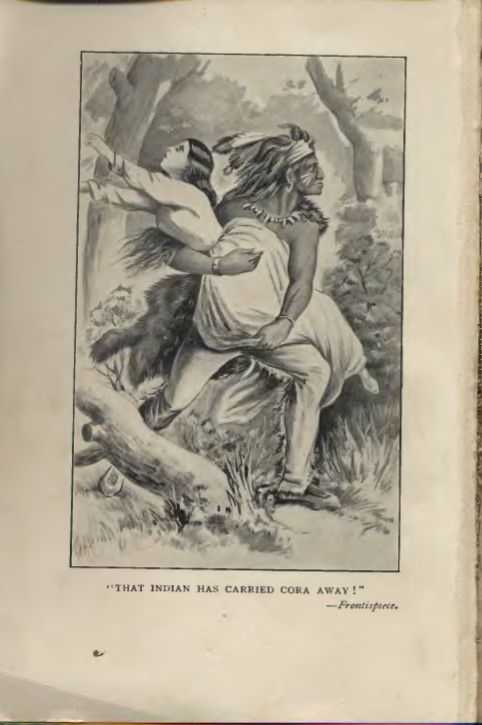

All at once her ear caught the sound of a footstep, and confident that Teddy had come, she turned her face toward the door to greet him. She uttered a slight scream, as she saw, instead of the honest Hibernian, the form of a towering, painted savage, glaring in upon her.

Ordinarily such a visitor would have occasioned her no surprise or alarm. In fact, it was rare that a day passed without some Indian visiting the cabin—either to consult with the missionary himself, or merely to rest a few moments. Sometimes several called together, and it often happened that they came while none but the wife was at home. They were always treated kindly, and were respectful and pleased in turn. During the nights in winter, when the storm howled through the forest, a light burned at the missionary's window, and many a savage, who belonged often to a distant tribe, had knocked at the door and secured shelter until morning. Ordinarily we say, then, the visit of an Indian gave the young wife no alarm.

But there was something in the appearance of this painted sinewy savage that filled her with dread. There was a treacherous look in his black eyes, and a sinister expression visible in spite of vermilion and ocher, that made her shrink from him, as she would have shrunk from some loathsome monster.

As the reader may have surmised, he was no other than Daffodil or Mahogany, who had left Teddy on purpose to visit the cabin, while both the servant and his master were absent. In spite of the precaution used, he had taken more liquor than he intended; and, as a consequence, was just in that reckless state of mind, when he would have hesitated at no deed, however heinous. From a jovial, good-natured Indian, in the company of the Hibernian, he was transformed into a sullen, vindictive savage in the presence of the gentle wife of Harvey Richter. He supported himself against the door and seemed undecided whether to enter or not. The alarm of Cora Richter was so excessive that she endeavored to conceal it.

"What do you wish?" she asked.

"Where Misser Richter?"

"Gone to the village," she replied, bravely resolving that no lie should cross her lips if her life depended upon it.

"When come back?"

"In an hour or so perhaps."

"Where Ted?"

"He has gone hunting."

"Big lie—he drunk—don't know nothing—lay sleep on ground."

"How do you know? Did you see him?"

"Me gib him fire-water—much like it—drink good deal—tumble over like tree hain't got root."

"Did you ever give it him before?" asked the young wife, her curiosity supplanting her alarm for the moment.

"Gib him offin—gib him every day—much like it—drink much."

Again the wife's instinctive fear came back to her, and she endeavored to conceal it by a calm, unimpassioned exterior.

"Won't you come in and rest yourself until Mr. Richter returns?"

"Don't want to see him," replied the savage, sullenly.

"Who do you wish to see then?"

"You—t'ink much of you."

The wife felt as if she would sink to the floor. There was something in the tones of his voice that had alarmed her from the first. She was almost certain this savage intended rudeness, now that he knew the missionary himself was gone. She glanced up at the rifle which was hung above the fireplace. It was charged, and she had learned how to fire it since her marriage. Several times she was on the point of springing up and seizing it and placing herself upon the defensive. Her heart throbbed wildly at the thought, but she finally concluded to resort to such an act only at the last moment. She might still conciliate the Indian by kindness, and after all, perhaps he meditated no harm or rudeness.

"Come and sit down then, and talk with me awhile," said she, as pleasantly as it was possible.

The savage stumbled forward a few feet, and dropped into a seat, where he glared fully a minute straight into the face of the woman. This was the most trying ordeal of all, especially when she raised her own blue eyes, and addressed him. It seemed impossible to combat the fierce light of those orbs, although she bore their scrutiny like a heroine. He had seated himself near the door, but he was close enough for her to detect the fumes of the liquor he had drank, and she knew a savage was never so dangerous as when in a half-intoxicated condition.

"Have you come a long distance?" she asked.

"Good ways—live up north."

"You are not a Sioux, then?"

"No—don't like Sioux—bad people."

"Why do you come in their neighborhood—in their country?"