Title: At Sunwich Port, Part 2.

Author: W. W. Jacobs

Release date: January 1, 2004 [eBook #10872]

Most recently updated: December 23, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

For the first few days after his return Sunwich was full of surprises to Jem Hardy. The town itself had changed but little, and the older inhabitants were for the most part easily recognisable, but time had wrought wonders among the younger members of the population: small boys had attained to whiskered manhood, and small girls passing into well-grown young women had in some cases even changed their names.

The most astounding and gratifying instance of the wonders effected by time was that of Miss Nugent. He saw her first at the window, and with a ready recognition of the enchantment lent by distance took the first possible opportunity of a closer observation. He then realized the enchantment afforded by proximity. The second opportunity led him impetuously into a draper's shop, where a magnificent shop-walker, after first ceremoniously handing him a high cane chair, passed on his order for pins in a deep and thrilling baritone, and retired in good order.

By the end of a week his observations were completed, and Kate Nugent, securely enthroned in his mind as the incarnation of feminine grace and beauty, left but little room for other matters. On his second Sunday at home, to his father's great surprise, he attended church, and after contemplating Miss Nugent's back hair for an hour and a half came home and spoke eloquently and nobly on "burying hatchets," "healing old sores," "letting bygones be bygones," and kindred topics.

"I never take much notice of sermons myself," said the captain, misunderstanding.

"Sermon?" said his son. "I wasn't thinking of the sermon, but I saw Captain Nugent there, and I remembered the stupid quarrel between you. It's absurd that it should go on indefinitely."

"Why, what does it matter?" inquired the other, staring. "Why shouldn't it? Perhaps it's the music that's affected you; some of those old hymns—"

"It wasn't the sermon and it wasn't the hymns," said his son, disdainfully; "it's just common sense. It seems to me that the enmity between you has lasted long enough."

"I don't see that it matters," said the captain; "it doesn't hurt me. Nugent goes his way and I go mine, but if I ever get a chance at the old man, he'd better look out. He wants a little of the starch taken out of him."

"Mere mannerism," said his son.

"He's as proud as Lucifer, and his girl takes after him," said the innocent captain. "By the way, she's grown up a very good-looking girl. You take a look at her the next time you see her."

His son stared at him.

"She'll get married soon, I should think," continued the other. "Young Murchison, the new doctor here, seems to be the favourite. Nugent is backing him, so they say; I wish him joy of his father-in-law."

Jem Hardy took his pipe into the garden, and, pacing slowly up and down the narrow paths, determined, at any costs, to save Dr. Murchison from such a father-in-law and Kate Nugent from any husband except of his choosing. He took a seat under an old apple tree, and, musing in the twilight, tried in vain to think of ways and means of making her acquaintance.

Meantime they passed each other as strangers, and the difficulty of approaching her only made the task more alluring. In the second week he reckoned up that he had seen her nine times. It was a satisfactory total, but at the same time he could not shut his eyes to the fact that five times out of that number he had seen Dr. Murchison as well, and neither of them appeared to have seen him.

He sat thinking it over in the office one hot afternoon. Mr. Adolphus Swann, his partner, had just returned from lunch, and for about the fifth time that day was arranging his white hair and short, neatly pointed beard in a small looking-glass. Over the top of it he glanced at Hardy, who, leaning back in his chair, bit his pen and stared hard at a paper before him.

"Is that the manifest of the North Star?" he inquired.

"No," was the reply.

Mr. Swann put his looking-glass away and watched the other as he crossed over to the window and gazed through the small, dirty panes at the bustling life of the harbour below. For a short time Hardy stood gazing in silence, and then, suddenly crossing the room, took his hat from a peg and went out.

"Restless," said the senior partner, wiping his folders with great care and putting them on. "Wonder where he's put that manifest."

He went over to the other's desk and opened a drawer to search for it. Just inside was a sheet of foolscap, and Mr. Swann with growing astonishment slowly mastered the contents.

"See her as often as possible."

"Get to know some of her friends."

"Try and get hold of the old lady."

"Find out her tastes and ideas."

"Show my hand before Murchison has it all his own way."

"It seems to me," said the bewildered shipbroker, carefully replacing the paper, "that my young friend is looking out for another partner. He hasn't lost much time."

He went back to his seat and resumed his work. It occurred to him that he ought to let his partner know what he had seen, and when Hardy returned he had barely seated himself before Mr. Swann with a mysterious smile crossed over to him, bearing a sheet of foolscap.

"Try and dress as well as my partner," read the astonished Hardy. "What's the matter with my clothes? What do you mean?"

Mr. Swann, in place of answering, returned to his desk and, taking up another sheet of foolscap, began to write again, holding up his hand for silence as Hardy repeated his question. When he had finished his task he brought it over and placed it in the other's hand.

"Take her little brother out for walks."

Hardy crumpled the paper up and flung it aside. Then, with his face crimson, he stared wrathfully at the benevolent Swann.

"It's the safest card in the pack," said the latter. "You please everybody; especially the little brother. You should always hold his hand—it looks well for one thing, and if you shut your eyes—"

"I don't want any of your nonsense," said the maddened Jem. "What do you mean by reading my private papers?"

"I came over to look for the manifest," said Mr. Swann, "and I read it before I could make out what it was. You must admit it's a bit cryptic. I thought it was a new game at first. Getting hold of the old lady sounds like a sort of blind-man's buff. But why not get hold of the young one? Why waste time over—"

"Go to the devil," said the junior partner.

"Any more suggestions I can give you, you are heartily welcome to," said Mr. Swann, going back to his seat. "All my vast experience is at your service, and the best and sweetest and prettiest girls in Sunwich regard me as a sort of second father."

"What's a second father?" inquired Jim, looking up—"a grandfather?"

"Go your own way," said the other; "I wash my hands of you. You're not in earnest, or you'd clutch at any straw. But let me give you one word of advice. Be careful how you get hold of the old lady; let her understand from the commencement that it isn't her."

Mr. Hardy went on with his work. There was a pile of it in front of him and an accumulation in his drawers. For some time he wrote assiduously, but work was dry after the subject they had been discussing. He looked over at his partner and, seeing that that gentleman was gravely busy, reopened the matter with a jeer.

"Old maids always know most about rearing children," he remarked; "so I suppose old bachelors, looking down on life from the top shelf, think they know most about marriage."

"I wash my hands of you," repeated the senior, placidly. "I am not to be taunted into rendering first aid to the wounded."

The conscience-stricken junior lost his presence of mind. "Who's trying to taunt you?" he demanded, hotly. "Why, you'd do more harm than good."

"Put a bandage round the head instead of the heart, I expect," assented the chuckling Swann. "Top shelf, I think you said; well, I climbed there for safety."

"You must have been much run after," said his partner.

"I was," said the other. "I suppose that's why it is I am always so interested in these affairs. I have helped to marry so many people in this place, that I'm almost afraid to stir out after dark."

Hardy's reply was interrupted by the entrance of Mr. Edward Silk, a young man of forlorn aspect, who combined in his person the offices of messenger, cleaner, and office-boy to the firm. He brought in some letters, and placing them on Mr. Swann's desk retired.

"There's another," said the latter, as the door closed. "His complaint is Amelia Kybird, and he's got it badly. She's big enough to eat him, but I believe that they are engaged. Perseverance has done it in his case. He used to go about like a blighted flower—"

"I am rather busy," his partner reminded him.

Mr. Swann sighed and resumed his own labours. For some time both men wrote in silence. Then the elder suddenly put his pen down and hit his desk a noisy thump with his fist.

"I've got it," he said, briskly; "apologize humbly for all your candour, and I will give you a piece of information which shall brighten your dull eyes, raise the corners of your drooping mouth, and renew once more the pink and cream in your youthful cheeks."

"Look here—" said the overwrought Hardy.

"Samson Wilks," interrupted Mr. Swann, "number three, Fullalove Alley, at home Fridays, seven to nine, to the daughter of his late skipper, who always visits him on that day. Don't thank me, Hardy, in case you break down. She's a very nice girl, and if she had been born twenty years earlier, or I had been born twenty years later, or you hadn't been born at all, there's no saying what might not have happened."

"When I want you to interfere in my business," said Hardy, working sedulously, "I'll let you know."

"Very good," replied Swann; "still, remember Thursdays, seven to nine."

"Thursdays," said Hardy, incautiously; "why, you said Fridays just now."

Mr. Swann made no reply. His nose was immersed in the folds of a large handkerchief, and his eyes watered profusely behind his glasses. It was some minutes before he had regained his normal composure, and even then the sensitive nerves of his partner were offended by an occasional belated chuckle.

Although by dint of casual and cautious inquiries Mr. Hardy found that his partner's information was correct, he was by no means guilty of any feelings of gratitude towards him; and he only glared scornfully when that excellent but frivolous man mounted a chair on Friday afternoon, and putting the clock on a couple of hours or so, urged him to be in time.

The evening, however, found him starting slowly in the direction of Fullalove Alley. His father had gone to sea again, and the house was very dull; moreover, he felt a mild curiosity to see the changes wrought by time in Mr. Wilks. He walked along by the sea, and as the church clock struck the three-quarters turned into the alley and looked eagerly round for the old steward.

The labours of the day were over, and the inhabitants were for the most part out of doors taking the air. Shirt-sleeved householders, leaning against their door-posts smoking, exchanged ideas across the narrow space paved with cobble-stones which separated their small and ancient houses, while the matrons, more gregariously inclined, bunched in little groups and discussed subjects which in higher circles would have inundated the land with libel actions. Up and down the alley a tiny boy all ready for bed, with the exception of his nightgown, mechanically avoided friendly palms as he sought anxiously for his mother.

The object of Mr. Hardy's search sat at the door of his front room, which opened on to the alley, smoking an evening pipe, and noting with an interested eye the doings of his neighbours. He was just preparing to draw himself up in his chair as the intruder passed, when to his utter astonishment that gentleman stopped in front of him, and taking possession of his hand shook it fervently.

"How do you do?" he said, smiling.

Mr. Wilks eyed him stupidly and, releasing his hand, coyly placed it in his trouser-pocket and breathed hard.

"I meant to come before," said Hardy, "but I've been so busy. How are you?"

Mr. Wilks, still dazed, muttered that he was very well. Then he sat bolt upright in his chair and eyed his visitor suspiciously.

"I've been longing for a chat with you about old times," said Hardy; "of all my old friends you seem to have changed the least. You don't look a day older."

"I'm getting on," said Mr. Wilks, trying to speak coldly, but observing with some gratification the effect produced upon his neighbours by the appearance of this well-dressed acquaintance.

"I wanted to ask your advice," said the unscrupulous Hardy, speaking in low tones. "I daresay you know I've just gone into partnership in Sunwich, and I'm told there's no man knows more about the business and the ins and outs of this town than you do."

Mr. Wilks thawed despite himself. His face glistened and his huge mouth broke into tremulous smiles. For a moment he hesitated, and then noticing that a little group near them had suspended their conversation to listen to his he drew his chair back and, in a kind voice, invited the searcher after wisdom to step inside.

Hardy thanked him, and, following him in, took a chair behind the door, and with an air of youthful deference bent his ear to catch the pearls which fell from the lips of his host. Since he was a babe on his mother's knee sixty years before Mr. Wilks had never had such an attentive and admiring listener. Hardy sat as though glued to his chair, one eye on Mr. Wilks and the other on the clock, and it was not until that ancient timepiece struck the hour that the ex-steward suddenly realized the awkward state of affairs.

"Any more 'elp I can give you I shall always be pleased to," he said, looking at the clock.

Hardy thanked him at great length, wondering, as he spoke, whether Miss Nugent was of punctual habits. He leaned back in his chair and, folding his arms, gazed thoughtfully at the perturbed Mr. Wilks.

"You must come round and smoke a pipe with me sometimes," he said, casually.

Mr. Wilks flushed with gratified pride. He had a vision of himself walking up to the front door of the Hardys, smoking a pipe in a well-appointed room, and telling an incredulous and envious Fullalove Alley about it afterwards.

"I shall be very pleased, sir," he said, impressively.

"Come round on Tuesday," said his visitor. "I shall be at home then."

Mr. Wilks thanked him and, spurred on to hospitality, murmured something about a glass of ale, and retired to the back to draw it. He came back with a jug and a couple of glasses, and draining his own at a draught, hoped that the example would not be lost upon his visitor. That astute person, however, after a modest draught, sat still, anchored to the half-empty glass.

"I'm expecting somebody to-night," said the ex-steward, at last.

"No doubt you have a lot of visitors," said the other, admiringly.

Mr. Wilks did not deny it. He eyed his guest's glass and fidgeted.

"Miss Nugent is coming," he said.

Instead of any signs of disorder and preparations for rapid flight, Mr. Wilks saw that the other was quite composed. He began to entertain a poor idea of Mr. Hardy's memory.

"She generally comes for a little quiet chat," he said.

"Indeed!"

"Just between the two of us," said the other.

His visitor said "Indeed," and, as though some chord of memory had been touched, sat gazing dreamily at Mr. Wilks's horticultural collection in the window. Then he changed colour a little as a smart hat and a pretty face crossed the tiny panes. Mr. Wilks changed colour too, and in an awkward fashion rose to receive Miss Nugent.

"Late as usual, Sam," said the girl, sinking into a chair. Then she caught sight of Hardy, who was standing by the door.

"It's a long time since you and I met, Miss Nugent," he said, bowing.

"Mr. Hardy?" said the girl, doubtfully.

"Yes, miss," interposed Mr. Wilks, anxious to explain his position. "He called in to see me; quite a surprise to me it was. I 'ardly knowed him."

"The last time we three met," said Hardy, who to his host's discomfort had resumed his chair, "Wilks was thrashing me and you were urging him on."

Kate Nugent eyed him carefully. It was preposterous that this young man should take advantage of a boy and girl acquaintance of eleven years before—and such an acquaintance!—in this manner. Her eyes expressed a little surprise, not unmixed with hauteur, but Hardy was too pleased to have them turned in his direction at all to quarrel with their expression.

"You were a bit of a trial in them days," said Mr. Wilks, shaking his head. "If I live to be ninety I shall never forget seeing Miss Kate capsized the way she was. The way she——"

"How is your cold?" inquired Miss Nugent, hastily.

"Better, miss, thankee," said Mr. Wilks.

"Miss Nugent has forgotten and forgiven all that long ago," said Hardy.

"Quite," assented the girl, coldly; "one cannot remember all the boys and girls one knew as a child."

"Certainly not," said Hardy. "I find that many have slipped from my own memory, but I have a most vivid recollection of you."

Miss Nugent looked at him again, and an idea, strange and incredible, dawned slowly upon her. Childish impressions are lasting, and Jem Hardy had remained in her mind as a sort of youthful ogre. He sat before her now a frank, determined-looking young Englishman, in whose honest eyes admiration of herself could not be concealed. Indignation and surprise struggled for supremacy.

"It's odd," remarked Mr. Wilks, who had a happy knack at times of saying the wrong thing, "it's odd you should 'ave 'appened to come just at the same time as Miss Kate did."

"It's my good fortune," said Hardy, with a slight bow. Then he cocked a malignant eye at the innocent Mr. Wilks, and wondered at what age men discarded the useless habit of blushing. Opposite him sat Miss Nugent, calmly observant, the slightest suggestion of disdain in her expression. Framed in the queer, high-backed old chair which had belonged to Mr. Wilks's grandfather, she made a picture at which Jem Hardy continued to gaze with respectful ardour. A hopeless sense of self-depreciation possessed him, but the idea that Murchison should aspire to so much goodness and beauty made him almost despair of his sex. His reverie was broken by the voice of Mr. Wilks.

"A quarter to eight?" said that gentleman in-credulously; "it can't be."

"I thought it was later than that," said Hardy, simply.

Mr. Wilks gasped, and with a faint shake of his head at the floor abandoned the thankless task of giving hints to a young man who was too obtuse to see them; and it was not until some time later that Mr. Hardy, sorely against his inclinations, gave his host a hearty handshake and, with a respectful bow to Miss Nugent, took his departure.

"Fine young man he's growed," said Mr. Wilks, deferentially, turning to his remaining visitor; "greatly improved, I think."

Miss Nugent looked him over critically before replying. "He seems to have taken a great fancy to you," she remarked.

Mr. Wilks smiled a satisfied smile. "He came to ask my advice about business," he said, softly. "He's 'eard two or three speak o' me as knowing a thing or two, and being young, and just starting, 'e came to talk it over with me. I never see a young man so pleased and ready to take advice as wot he is."

"He is coming again for more, I suppose?" said Miss Nugent, carelessly.

Mr. Wilks acquiesced. "And he asked me to go over to his 'ouse to smoke a pipe with 'im on Tuesday," he added, in the casual manner in which men allude to their aristocratic connections. "He's a bit lonely, all by himself."

Miss Nugent said, "Indeed," and then, lapsing into silence, gave little occasional side-glances at Mr. Wilks, as though in search of any hidden charms about him which might hitherto have escaped her.

At the same time Mr. James Hardy, walking slowly home by the edge of the sea, pondered on further ways and means of ensnaring the affection of the ex-steward.

The anticipations of Mr. Wilks were more than realized on the following Tuesday. From the time a trim maid showed him into the smoking-room until late at night, when he left, a feted and honoured guest, with one of his host's best cigars between his teeth, nothing that could yield him any comfort was left undone. In the easiest of easy chairs he sat in the garden beneath the leafy branches of apple trees, and undiluted wisdom and advice flowed from his lips in a stream as he beamed delightedly upon his entertainer.

Their talk was mainly of Sunwich and Sunwich people, and it was an easy step from these to Equator Lodge. On that subject most people would have found the ex-steward somewhat garrulous, but Jem Hardy listened with great content, and even brought him back to it when he showed signs of wandering. Altogether Mr. Wilks spent one of the pleasantest evenings of his life, and, returning home in a slight state of mental exhilaration, severely exercised the tongues of Fullalove Alley by a bearing considered incompatible with his station.

Jem Hardy paid a return call on the following Friday, and had no cause to complain of any lack of warmth in his reception. The ex-steward was delighted to see him, and after showing him various curios picked up during his voyages, took him to the small yard in the rear festooned with scarlet-runner beans, and gave him a chair in full view of the neighbours.

"I'm the only visitor to-night?" said Hardy, after an hour's patient listening and waiting.

Mr. Wilks nodded casually. "Miss Kate came last night," he said. "Friday is her night, but she came yesterday instead."

Mr. Hardy said, "Oh, indeed," and fell straight-way into a dismal reverie from which the most spirited efforts of his host only partially aroused him.

Without giving way to undue egotism it was pretty clear that Miss Nugent had changed her plans on his account, and a long vista of pleasant Friday evenings suddenly vanished. He, too, resolved to vary his visits, and, starting with a basis of two a week, sat trying to solve the mathematical chances of selecting the same as Kate Nugent; calculations which were not facilitated by a long-winded account from Mr. Wilks of certain interesting amours of his youthful prime.

Before he saw Kate Nugent again, however, another old acquaintance turned up safe and sound in Sunwich. Captain Nugent walking into the town saw him first: a tall, well-knit young man in shabby clothing, whose bearing even in the distance was oddly familiar. As he came closer the captain's misgivings were confirmed, and in the sunburnt fellow in tattered clothes who advanced upon him with out-stretched hand he reluctantly recognized his son.

"What have you come home for?" he inquired, ignoring the hand and eyeing him from head to foot.

"Change," said Jack Nugent, laconically, as the smile left his face.

The captain shrugged his shoulders and stood silent. His son looked first up the road and then down.

"All well at home?" he inquired.

"Yes."

Jack Nugent looked up the road again.

"Not much change in the town," he said, at length.

"No," said his father.

"Well, I'm glad to have seen you," said his son. "Good-bye."

"Good-bye," said the captain.

His son nodded and, turning on his heel, walked back towards the town. Despite his forlorn appearance his step was jaunty and he carried his head high. The captain watched him until he was hidden by a bend in the road, and then, ashamed of himself for displaying so much emotion, turned his own steps in the direction of home.

"Well, he didn't whine," he said, slowly. "He's got a bit of pride left."

Meantime the prodigal had reached the town again, and stood ruefully considering his position.

He looked up the street, and then, the well-known shop of Mr. Kybird catching his eye, walked over and inspected the contents of the window. Sheath-knives, belts, tobacco-boxes, and watches were displayed alluringly behind the glass, sheltered from the sun by a row of cheap clothing dangling from short poles over the shop front. All the goods were marked in plain figures in reduced circumstances, Mr. Kybird giving a soaring imagination play in the first marking, and a good business faculty in the second.

At these valuables Jack Nugent, with a view of obtaining some idea of prices, gazed for some time. Then passing between two suits of oilskins which stood as sentinels in the doorway, he entered the shop and smiled affably at Miss Kybird, who was in charge. At his entrance she put down a piece of fancy-work, which Mr. Kybird called his sock, and with a casual glance at his clothes regarded him with a prejudiced eye.

"Beautiful day," said the customer; "makes one feel quite young again."

"What do you want?" inquired Miss Kybird.

Mr. Nugent turned to a broken cane-chair which stood by the counter, and, after applying severe tests, regardless of the lady's feelings, sat down upon it and gave a sigh of relief.

"I've walked from London," he said, in explanation. "I could sit here for hours."

"Look here——" began the indignant Miss Kybird.

"Only people would be sure to couple our names together," continued Mr. Nugent, mournfully.

"When a handsome young man and a good-looking girl——"

"Do you want to buy anything or not?" demanded Miss Kybird, with an impatient toss of her head.

"No," said Jack, "I want to sell."

"You've come to the wrong shop, then," said Miss Kybird; "the warehouse is full of rubbish now."

The other turned in his chair and looked hard at the window. "So it is," he assented. "It's a good job I've brought you something decent to put there."

He felt in his pockets and, producing a silver-mounted briar-pipe, a battered watch, a knife, and a few other small articles, deposited them with reverent care upon the counter.

"No use to us," declared Miss Kybird, anxious to hit back; "we burn coal here."

"These'll burn better than the coal you buy," said the unmoved customer.

"Well, we don't want them," retorted Miss Kybird, raising her voice, "and I don't want any of your impudence. Get up out of our chair."

Her heightened tones penetrated to the small and untidy room behind the shop. The door opened, and Mr. Kybird in his shirt-sleeves appeared at the opening.

"Wot's the row?" he demanded, his little black eyes glancing from one to the other.

"Only a lovers' quarrel," replied Jack. "You go away; we don't want you."

"Look 'ere, we don't want none o' your nonsense," said the shopkeeper, sharply; "and, wot's more, we won't 'ave it. Who put that rubbish on my counter?"

He bustled forward, and taking the articles in his hands examined them closely.

"Three shillings for the lot—cash," he remarked. "Done," said the other.

"Did I say three?" inquired Mr. Kybird, startled at this ready acceptance.

"Five you said," replied Mr. Nugent, "but I'll take three, if you throw in a smile."

Mr. Kybird, much against his inclinations, threw in a faint grin, and opening a drawer produced three shillings and flung them separately on the counter. Miss Kybird thawed somewhat, and glancing from the customer's clothes to his face saw that he had a pleasant eye and a good moustache, together with a general air of recklessness much appreciated by the sex.

"Don't spend it on drink," she remarked, not unkindly.

"I won't," said the other, solemnly; "I'm going to buy house property with it."

"Why, darn my eyes," said Mr. Kybird, who had been regarding him closely; "darn my old eyes, if it ain't young Nugent. Well, well!"

"That's me," said young Nugent, cheerfully; "I should have known you anywhere, Kybird: same old face, same old voice, same old shirt-sleeves."

"'Ere, come now," objected the shopkeeper, shortening his arm and squinting along it.

"I should have known you anywhere," continued the other, mournfully; "and here I've thrown up a splendid berth and come all the way from Australia just for one glimpse of Miss Kybird, and she doesn't know me. When I die, Kybird, you will find the word 'Calais' engraven upon my heart."

Mr. Kybird said, "Oh, indeed." His daughter tossed her head and bade Mr. Nugent take his nonsense to people who might like it.

"Last time I see you," said Mr. Kybird, pursing up his lips and gazing at the counter in an effort of memory; "last time I see you was one fifth o' November when you an' another bright young party was going about in two suits o' oilskins wot I'd been 'unting for 'igh and low all day long."

Jack Nugent sighed. "They were happy times, Kybird."

"Might ha' been for you," retorted the other, his temper rising a little at the remembrance of his wrongs.

"Have you come home for good? inquired Miss Kybird, curiously. Have you seen your father? He passed here a little while ago."

"I saw him," said Jack, with a brevity which was not lost upon the astute Mr. Kybird. "I may stay in Sunwich, and I may not—it all depends."

"You're not going 'ome?" said Mr. Kybird.

"No."

The shopkeeper stood considering. He had a small room to let at the top of his house, and he stood divided between the fear of not getting his rent and the joy to a man fond of simple pleasures, to be obtained by dunning the arrogant Captain Nugent for his son's debts. Before he could arrive at a decision his meditations were interrupted by the entrance of a stout, sandy-haired lady from the back parlour, who, having conquered his scruples against matrimony some thirty years before, had kept a particularly wide-awake eye upon him ever since.

"Your tea's a-gettin' cold," she remarked, severely.

Her husband received the news with calmness. He was by no means an enthusiast where that liquid was concerned, the admiration evoked by its non-inebriating qualities having been always something in the nature of a mystery to him.

"I'm coming," he retorted; "I'm just 'aving a word with Mr. Nugent 'ere."

"Well, I never did," said the stout lady, coming farther into the shop and regarding the visitor. "I shouldn't 'ave knowed 'im. If you'd asked me who 'e was I couldn't ha' told you—I shouldn't 'ave knowed 'im from Adam."

Jack shook his head. "It's hard to be forgotten like this," he said, sadly. "Even Miss Kybird had forgotten me, after all that had passed between us."

"Eh?" said Mr. Kybird.

"Oh, don't take any notice of him," said his daughter. "I'd like to see myself."

Mr. Kybird paid no heed. He was still thinking of the son of Captain Nugent being indebted to him for lodging, and the more he thought of the idea the better he liked it.

"Well, now you're 'ere," he said, with a great assumption of cordiality, "why not come in and 'ave a cup o' tea?"

The other hesitated a moment and then, with a light laugh, accepted the offer. He followed them into the small and untidy back parlour, and being requested by his hostess to squeeze in next to 'Melia at the small round table, complied so literally with the order that that young lady complained bitterly of his encroachments.

"And where do you think of sleeping to-night?" inquired Mr. Kybird after his daughter had, to use her own expressive phrase, shown the guest "his place."

Mr. Nugent shook his head. "I shall get a lodging somewhere," he said, airily.

"There's a room upstairs as you might 'ave if you liked," said Mr. Kybird, slowly. "It's been let to a very respectable, clean young man for half a crown a week. Really it ought to be three shillings, but if you like to 'ave it at the old price, you can."

"Done with you," said the other.

"No doubt you'll soon get something to do," continued Mr. Kybird, more in answer to his wife's inquiring glances than anything else. "Half a crown every Saturday and the room's yours."

Mr. Nugent thanked him, and after making a tea which caused Mr. Kybird to congratulate himself upon the fact that he hadn't offered to board him, sat regaling Mrs. Kybird and daughter with a recital of his adventures in Australia, receiving in return a full and true account of Sunwich and its people up to date.

"There's no pride about 'im, that's what I like," said Mrs. Kybird to her lord and master as they sat alone after closing time over a glass of gin and water. "He's a nice young feller, but bisness is bisness, and s'pose you don't get your rent?"

"I shall get it sooner or later," said Mr. Kybird. "That stuck-up father of 'is 'll be in a fine way at 'im living here. That's wot I'm thinking of."

"I don't see why," said Mrs. Kybird, bridling. "Who's Captain Nugent, I should like to know? We're as good as what 'e is, if not better. And as for the gell, if she'd got 'all Amelia's looks she'd do."

"'Melia's a fine-looking gal," assented Mr. Kybird. "I wonder——"

He laid his pipe down on the table and stared at the mantelpiece. "He seems very struck with 'er," he concluded. "I see that directly."

"Not afore I did," said his wife, sharply.

"See it afore you come into the shop," said Mr. Kybird, triumphantly. "It 'ud be a strange thing to marry into that family, Emma."

"She's keeping company with young Teddy Silk," his wife reminded him, coldly; "and if she wasn't she could do better than a young man without a penny in 'is pocket. Pride's a fine thing, Dan'l, but you can't live on it."

"I know what I'm talking about," said Mr. Kybird, impatiently. "I know she's keeping company with Teddy as well as wot you do. Still, as far as money goes, young Nugent 'll be all right."

"'Ow?" inquired his wife.

Mr. Kybird hesitated and took a sip of his gin and water. Then he regarded the wife of his bosom with a calculating glance which at once excited that lady's easily kindled wrath.

"You know I never tell secrets," she cried.

"Not often," corrected Mr. Kybird, "but then I don't often tell you any. Wot would you say to young Nugent coming into five 'undred pounds 'is mother left 'im when he's twenty-five? He don't know it, but I do."

"Five 'undred," repeated his wife, "sure?"

"No," said the other, "I'm not sure, but I know. I 'ad it from young Roberts when 'e was at Stone and Dartnell's. Five 'undred pounds! I shall get my money all right some time, and, if 'e wants a little bit to go on with, 'e can have it. He's honest enough; I can see that by his manner."

Upstairs in the tiny room under the tiles Mr. Jack Nugent, in blissful ignorance of his landlord's generous sentiments towards him, slept the sound, dreamless sleep of the man free from monetary cares. In the sanctity of her chamber Miss Kybird, gazing approvingly at the reflection of her yellow hair and fine eyes in the little cracked looking-glass, was already comparing him very favourably with the somewhat pessimistic Mr. Silk.

Mr. Nugent's return caused a sensation in several quarters, the feeling at Equator Lodge bordering close upon open mutiny. Even Mrs. Kingdom plucked up spirit and read the astonished captain a homily upon the first duties of a parent—a homily which she backed up by reading the story of the Prodigal Son through to the bitter end. At the conclusion she broke down entirely and was led up to bed by Kate and Bella, the sympathy of the latter taking an acute form, and consisting mainly of innuendoes which could only refer to one person in the house.

Kate Nugent, who was not prone to tears, took a different line, but with no better success. The captain declined to discuss the subject, and, after listening to a description of himself in which Nero and other celebrities figured for the purpose of having their characters whitewashed, took up his hat and went out.

Jem Hardy heard of the new arrival from his partner, and, ignoring that gentleman's urgent advice to make hay while the sun shone and take Master Nugent for a walk forthwith sat thoughtfully considering how to turn the affair to the best advantage. A slight outbreak of diphtheria at Fullalove Alley had, for a time, closed that thoroughfare to Miss Nugent, and he was inclined to regard the opportune arrival of her brother as an effort of Providence on his behalf.

For some days, however, he looked for Jack Nugent in vain, that gentleman either being out of doors engaged in an earnest search for work, or snugly seated in the back parlour of the Kybirds, indulging in the somewhat perilous pastime of paying compliments to Amelia Kybird. Remittances which had reached him from his sister and aunt had been promptly returned, and he was indebted to the amiable Mr. Kybird for the bare necessaries of life. In these circumstances a warm feeling of gratitude towards the family closed his eyes to their obvious shortcomings.

He even obtained work down at the harbour through a friend of Mr. Kybird's. It was not of a very exalted nature, and caused more strain upon the back than the intellect, but seven years of roughing it had left him singularly free from caste prejudices, a freedom which he soon discovered was not shared by his old acquaintances at Sunwich. The discovery made him somewhat bitter, and when Hardy stopped him one afternoon as he was on his way home from work he tried to ignore his outstretched hand and continued on his way.

"It is a long time since we met," said Hardy, placing himself in front of him.

"Good heavens," said Jack, regarding him closely, "it's Jemmy Hardy— grown up spick and span like the industrious little boys in the school-books. I heard you were back here."

"I came back just before you did," said Hardy. "Brass band playing you in and all that sort of thing, I suppose," said the other. "Alas, how the wicked prosper—and you were wicked. Do you remember how you used to knock me about?"

"Come round to my place and have a chat," said Hardy.

Jack shook his head. "They're expecting me in to tea," he said, with a nod in the direction of Mr. Kybird's, "and honest waterside labourers who earn their bread by the sweat of their brow—when the foreman is looking —do not frequent the society of the upper classes."

"Don't be a fool," said Hardy, politely.

"Well, I'm not very tidy," retorted Mr. Nugent, glancing at his clothes. "I don't mind it myself; I'm a philosopher, and nothing hurts me so long as I have enough to eat and drink; but I don't inflict myself on my friends, and I must say most of them meet me more than half-way."

"Imagination," said Hardy.

"All except Kate and my aunt," said Jack, firmly. "Poor Kate; I tried to cut her the other day."

"Cut her?" echoed Hardy.

Nugent nodded. "To save her feelings," he replied; "but she wouldn't be cut, bless her, and on the distinct understanding that it wasn't to form a precedent, I let her kiss me behind a waggon. Do you know, I fancy she's grown up rather good-looking, Jem?"

"You are observant," said Mr. Hardy, admiringly.

"Of course, it may be my partiality," said Mr. Nugent, with judicial fairness. "I was always a bit fond of Kate. I don't suppose anybody else would see anything in her. Where are you living now?"

"Fort Road," said Hardy; "come round any evening you can, if you won't come now."

Nugent promised, and, catching sight of Miss Kybird standing in the doorway of the shop, bade him good-bye and crossed the road. It was becoming quite a regular thing for her to wait and have her tea with him now, an arrangement which was provocative of many sly remarks on the part of Mrs. Kybird.

"Thought you were never coming," said Miss Kybird, tartly, as she led the way to the back room and took her seat at the untidy tea-tray.

"And you've been crying your eyes out, I suppose," remarked Mr. Nugent, as he groped in the depths of a tall jar for black-currant jam. "Well, you're not the first, and I don't suppose you'll be the last. How's Teddy?"

"Get your tea," retorted Miss Kybird, "and don't make that scraping noise on the bottom of the jar with your knife. It puts my teeth on edge."

"So it does mine," said Mr. Nugent, "but there's a black currant down there, and I mean to have it. 'Waste not, want not.'"

"Make him put that knife down," said Miss Kybird, as her mother entered the room. Mrs. Kybird shook her head at him. "You two are always quarrelling," she said, archly, "just like a couple of—couple of——"

"Love-birds," suggested Mr. Nugent.

Mrs. Kybird in great glee squeezed round to him and smote him playfully with her large, fat hand, and then, being somewhat out of breath with the exertion, sat down to enjoy the jest in comfort.

"That's how you encourage him," said her daughter; "no wonder he doesn't behave. No wonder he acts as if the whole place belongs to him."

The remark was certainly descriptive of Mr. Nugent's behaviour. His easy assurance and affability had already made him a prime favourite with Mrs. Kybird, and had not been without its effect upon her daughter. The constrained and severe company manners of Mr. Edward Silk showed up but poorly beside those of the paying guest, and Miss Kybird had on several occasions drawn comparisons which would have rendered both gentlemen uneasy if they had known of them.

Mr. Nugent carried the same easy good-fellowship with him the following week when, neatly attired in a second-hand suit from Mr. Kybird's extensive stock, he paid a visit to Jem Hardy to talk over old times and discuss the future.

"You ought to make friends with your father," said the latter; "it only wants a little common sense and mutual forbearance."

"That's all," said Nugent; "sounds easy enough, doesn't it? No, all he wants is for me to clear out of Sunwich, and I'm not going to—until it pleases me, at any rate. It's poison to him for me to be living at the Kybirds' and pushing a trolley down on the quay. Talk about love sweetening toil, that does."

Hardy changed the subject, and Nugent, nothing loath, discoursed on his wanderings and took him on a personally conducted tour through the continent of Australia. "And I've come back to lay my bones in Sunwich Churchyard," he concluded, pathetically; "that is, when I've done with 'em."

"A lot of things'll happen before then," said Hardy.

"I hope so," rejoined Mr. Nugent, piously; "my desire is to be buried by my weeping great-grandchildren. In fact, I've left instructions to that effect in my will—all I have left, by the way."

"You're not going to keep on at this water-side work, I suppose?" said Hardy, making another effort to give the conversation a serious turn.

"The foreman doesn't think so," replied the other, as he helped himself to some whisky; "he has made several remarks to that effect lately."

He leaned back in his chair and smoked thoughtfully, by no means insensible to the comfort of his surroundings. He had not been in such comfortable quarters since he left home seven years before. He thought of the untidy litter of the Kybirds' back parlour, with the forlorn view of the yard in the rear. Something of his reflections he confided to Hardy as he rose to leave.

"But my market value is about a pound a week," he concluded, ruefully, "so I must cut my coat to suit my cloth. Good-night."

He walked home somewhat soberly at first, but the air was cool and fresh and a glorious moon was riding in the sky. He whistled cheerfully, and his spirits rose as various chimerical plans of making money occurred to him. By the time he reached the High Street, the shops of which were all closed for the night, he was earning five hundred a year and spending a thousand. He turned the handle of the door and, walking in, discovered Miss Kybird entertaining company in the person of Mr. Edward Silk.

"Halloa," he said, airily, as he took a seat. "Don't mind me, young people. Go on just as you would if I were not here."

Mr. Edward Silk grumbled something under his breath; Miss Kybird, turning to the intruder with a smile of welcome, remarked that she had just thought of going to sleep.

"Going to sleep?" repeated Mr. Silk, thunder-struck.

"Yes," said Miss Kybird, yawning.

Mr. Silk gazed at her, open-mouthed. "What, with me 'ere?" he inquired, in trembling tones.

"You're not very lively company," said Miss Kybird, bending over her sewing. "I don't think you've spoken a word for the last quarter of an hour, and before that you were talking of death-warnings. Made my flesh creep, you did."

"Shame!" said Mr. Nugent.

"You didn't say anything to me about your flesh creeping," muttered Mr. Silk.

"You ought to have seen it creep," interposed Mr. Nugent, severely.

"I'm not talking to you," said Mr. Silk, turning on him; "when I want the favour of remarks from you I'll let you know."

"Don't you talk to my gentlemen friends like that, Teddy," said Miss Kybird, sharply, "because I won't have it. Why don't you try and be bright and cheerful like Mr. Nugent?"

Mr. Silk turned and regarded that gentleman steadfastly; Mr. Nugent meeting his gaze with a pleasant smile and a low-voiced offer to give him lessons at half a crown an hour.

"I wouldn't be like 'im for worlds," said Mr. Silk, with a scornful laugh. "I'd sooner be like anybody."

"What have you been saying to him?" inquired Nugent.

"Nothing," replied Miss Kybird; "he's often like that. He's got a nasty, miserable, jealous disposition. Not that I mind what he thinks."

Mr. Silk breathed hard and looked from one to the other.

"Perhaps he'll grow out of it," said Nugent, hopefully. "Cheer up, Teddy. You're young yet."

"Might I arsk," said the solemnly enraged Mr. Silk, "might I arsk you not to be so free with my Christian name?"

"He doesn't like his name now," said Nugent, drawing his chair closer to Miss Kybird's, "and I don't wonder at it. What shall we call him? Job? What's that work you're doing? Why don't you get on with that fancy waistcoat you are doing for me?"

Before Miss Kybird could deny all knowledge of the article in question her sorely tried swain created a diversion by rising. To that simple act he imparted an emphasis which commanded the attention of both beholders, and, drawing over to Miss Kybird, he stood over her in an attitude at once terrifying and reproachful.

"Take your choice, Amelia," he said, in a thrilling voice. "Me or 'im— which is it to be?"

"Here, steady, old man," cried the startled Nugent. "Go easy."

"Me or 'im?" repeated Mr. Silk, in stern but broken accents.

Miss Kybird giggled and, avoiding his gaze, looked pensively at the faded hearthrug.

"You're making her blush," said Mr. Nugent, sternly. "Sit down, Teddy; I'm ashamed of you. We're both ashamed of you. You're confusing us dreadfully proposing to us both in this way."

Mr. Silk regarded him with a scornful eye, but Miss Kybird, bidding him not to be foolish, punctuated her remarks with the needle, and a struggle, which Mr. Silk regarded as unseemly in the highest degree, took place between them for its possession.

Mr. Nugent secured it at last, and brandishing it fiercely extorted feminine screams from Miss Kybird by threatening her with it. Nor was her mind relieved until Mr. Nugent, remarking that he would put it back in the pincushion, placed it in the leg of Mr. Edward Silk.

Mr. Kybird and his wife, entering through the shop, were just in time to witness a spirited performance on the part of Mr. Silk, the cherished purpose of which was to deprive them of a lodger. He drew back as they entered and, raising his voice above Miss Kybird's, began to explain his action.

"Teddy, I'm ashamed of you," said Mr. Kybird, shaking his head. "A little joke like that; a little innercent joke."

"If it 'ad been a darning-needle now—" began Mrs. Kybird.

"All right," said the desperate Mr. Silk, "'ave it your own way. Let 'Melia marry 'im—I don't care—-I give 'er up."

"Teddy!" said Mr. Kybird, in a shocked voice. "Teddy!"

Mr. Silk thrust him fiercely to one side and passed raging through the shop. The sound of articles falling in all directions attested to his blind haste, and the force with which he slammed the shop-door was sufficient evidence of his state of mind.

"Well, upon my word," said the staring Mr. Kybird; "of all the outrageyous—"

"Never mind 'im," said his wife, who was sitting in the easy chair, distributing affectionate smiles between her daughter and the startled Mr. Nugent. "Make 'er happy, Jack, that's all I arsk. She's been a good gal, and she'll make a good wife. I've seen how it was between you for some time."

"So 'ave I," said Mr. Kybird. He shook hands warmly with Mr. Nugent, and, patting that perturbed man on the back, surveyed him with eyes glistening with approval.

"It's a bit rough on Teddy, isn't it?" inquired Mr. Nugent, anxiously; "besides—"

"Don't you worry about 'im," said Mr. Kybird, affectionately. "He ain't worth it."

"I wasn't," said Mr. Nugent, truthfully. The situation had developed so rapidly that it had caught him at a disadvantage. He had a dim feeling that, having been the cause of Miss Kybird's losing one young man, the most elementary notions of chivalry demanded that he should furnish her with another. And this idea was clearly uppermost in the minds of her parents. He looked over at Amelia and with characteristic philosophy accepted the position.

"We shall be the handsomest couple in Sunwich," he said, simply.

"Bar none," said Mr. Kybird, emphatically.

The stout lady in the chair gazed ax the couple fondly. "It reminds me of our wedding," she said, softly. "What was it Tom Fletcher said, father? Can you remember?"

"'Arry Smith, you mean," corrected Mr. Kybird.

"Tom Fletcher said something, I'm sure," persisted his wife.

"He did," said Mr. Kybird, grimly, "and I pretty near broke 'is 'ead for it. 'Arry Smith is the one you're thinking of."

Mrs. Kybird after a moment's reflection admitted that he was right, and, the chain of memory being touched, waxed discursive about her own wedding and the somewhat exciting details which accompanied it. After which she produced a bottle labelled "Port wine" from the cupboard, and, filling four glasses, celebrated the occasion in a befitting but sober fashion.

"This," said Mr. Nugent, as he sat on his bed that night to take his boots off, "this is what comes of trying to make everybody happy and comfortable with a little fun. I wonder what the governor'll say."

The news of his only son's engagement took Captain Nugent's breath away, which, all things considered, was perhaps the best thing it could have done. He sat at home in silent rage, only exploding when the well-meaning Mrs. Kingdom sought to minimize his troubles by comparing them with those of Job. Her reminder that to the best of her remembrance he had never had a boil in his life put the finishing touch to his patience, and, despairing of drawing-room synonyms for the words which trembled on his lips, he beat a precipitate retreat to the garden.

His son bore his new honours bravely. To an appealing and indignant letter from his sister he wrote gravely, reminding her of the difference in their years, and also that he had never interfered in her flirtations, however sorely his brotherly heart might have been wrung by them. He urged her to forsake such diversions for the future, and to look for an alliance with some noble, open-handed man with a large banking account and a fondness for his wife's relatives.

To Jem Hardy, who ventured on a delicate re-monstrance one evening, he was less patient, and displayed a newly acquired dignity which was a source of considerable embarrassment to that well-meaning gentleman. He even got up to search for his hat, and was only induced to resume his seat by the physical exertions of his host.

"I didn't mean to be offensive," said the latter. "But you were," said the aggrieved man. Hardy apologized.

"Talk of that kind is a slight to my future wife," said Nugent, firmly. "Besides, what business is it of yours?"

Hardy regarded him thoughtfully. It was some time since he had seen Miss Nugent, and he felt that he was losing valuable time. He had hoped great things from the advent of her brother, and now his intimacy seemed worse than useless. He resolved to take him into his confidence.

"I spoke from selfish motives," he said, at last. I wanted you to make friends with your father again."

"What for?" inquired the other, staring.

"To pave the way for me," said Hardy, raising his voice as he thought of his wrongs; "and now, owing to your confounded matrimonial business, that's all knocked on the head. I wouldn't care whom you married if it didn't interfere with my affairs so."

"Do you mean," inquired the astonished Mr. Nugent, "that you want to be on friendly terms with my father?"

"Yes."

Mr. Nugent gazed at him round-eyed. "You haven't had a blow on the head or anything of that sort at any time, have you?" he inquired.

Hardy shook his head impatiently. "You don't seem to suffer from an excess of intellect yourself," he retorted. "I don't want to be offensive again, still, I should think it is pretty plain there is only one reason why I should go out of my way to seek the society of your father."

"Say what you like about my intellect," replied the dutiful son, "but I can't think of even one—not even a small one. Not—Good gracious! You don't mean—you can't mean—"

Hardy looked at him.

"Not that," said Mr. Nugent, whose intellect had suddenly become painfully acute—"not her?"

"Why not?" inquired the other.

Mr. Nugent leaned back in his chair and regarded him with an air of kindly interest. "Well, there's no need for you to worry about my father for that," he said; "he would raise no objection."

"Eh?" said Hardy, starting up from his chair.

"He would welcome it," said Mr. Nugent, positively. "There is nothing that he would like better; and I don't mind telling you a secret—she likes you."

Hardy reddened. "How do you know?" he stammered.

"I know it for a fact," said the other, impressively. "I have heard her say so. But you've been very plain-spoken about me, Jem, so that I shall say what I think."

"Do," said his bewildered friend.

"I think you'd be throwing yourself away," said Nugent; "to my mind it's a most unsuitable match in every way. She's got no money, no looks, no style. Nothing but a good kind heart rather the worse for wear. I suppose you know she's been married once?"

"What!" shouted the other. "Married?"

Mr. Nugent nodded. His face was perfectly grave, but the joke was beginning to prey upon his vitals in a manner which brooked no delay.

"I thought everybody knew it," he said. "We have never disguised the fact. Her husband died twenty years ago last——"

"Twenty" said his suddenly enlightened listener. "Who?—What?"

Mr. Nugent, incapable of reply, put his head on the table and beat the air frantically with his hand, while gasping sobs rent his tortured frame.

"Dear—aunt," he choked, "how pleas—pleased she'd be if—she knew. Don't look like that, Hardy. You'll kill me."

"You seem amused," said Hardy, between his teeth.

"And you'll be Kate's uncle," said Mr. Nugent, sitting up and wiping his eyes. "Poor little Kate."

He put his head on the table again. "And mine," he wailed. "Uncle jemmy!—will you tip us half-crowns, nunky?"

Mr. Hardy's expression of lofty scorn only served to retard his recovery, but he sat up at last and, giving his eyes a final wipe, beamed kindly upon his victim.

"Well, I'll do what I can for you," he observed, "but I suppose you know Kate's off for a three months' visit to London to-morrow?"

The other observed that he didn't know it, and, taught by his recent experience, eyed him suspiciously.

"It's quite true," said Nugent; "she's going to stay with some relatives of ours. She used to be very fond of one of the boys—her cousin Herbert—so you mustn't be surprised if she comes back engaged. But I daresay you'll have forgotten all about her in three months. And, anyway, I don't suppose she'd look at you if you were the last man in the world. If you'll walk part of the way home with me I'll regale you with anecdotes of her chilhood which will probably cause you to change your views altogether."

In Fullalove Alley Mr. Edward Silk, his forebodings fulfilled, received the news of Amelia Kybird's faithlessness in a spirit of' quiet despair, and turned a deaf ear to the voluble sympathy of his neighbours. Similar things had happened to young men living there before, but their behaviour had been widely different to Mr. Silk's. Bob Crump, for instance, had been jilted on the very morning he had arranged for his wedding, but instead of going about in a state of gentle melancholy he went round and fought his beloved's father—merely because it was her father—and wound up an exciting day by selling off his household goods to the highest bidders. Henry Jones in similar circumstances relieved his great grief by walking up and down the alley smashing every window within reach of his stick.

But these were men of spirit; Mr. Silk was cast in a different mould, and his fair neighbours sympathized heartily with him in his bereavement, while utterly failing to understand any man breaking his heart over Amelia Kybird.

His mother, a widow of uncertain age, shook her head over him and hinted darkly at consumption, an idea which was very pleasing to her son, and gave him an increased interest in a slight cold from which he was suffering.

"He wants taking out of 'imself," said Mr. Wilks, who had stepped across the alley to discuss the subject with his neighbour; "cheerful society and 'obbies—that's what 'e wants."

"He's got a faithful 'eart," sighed Mrs. Silk. "It's in the family; 'e can't 'elp it."

"But 'e might be lifted out of it," urged Mr. Wilks. "I 'ad several disappointments in my young days. One time I 'ad a fresh gal every v'y'ge a'most."

Mrs. Silk sniffed and looked up the alley, whereat two neighbours who happened to be at their doors glanced up and down casually, and retreated inside to continue their vigil from the windows.

"Silk courted me for fifteen years before I would say 'yes,'" she said, severely.

"Fifteen years!" responded the other. He cast his eyes upwards and his lips twitched. The most casual observer could have seen that he was engaged in calculations of an abstruse and elusive nature.

"I was on'y seven when 'e started," said Mrs. Silk, sharply.

Mr. Wilks brought his eyes to a level again. "Oh, seven," he remarked.

"And we was married two days before my nineteenth birthday," added Mrs. Silk, whose own arithmetic had always been her weak point.

"Just so," said Mr. Wilks. He glanced at the sharp white face and shapeless figure before him. "It's hard to believe you can 'ave a son Teddy's age," he added, gallantly.

"It makes you feel as if you're getting on," said the widow.

The ex-steward agreed, and after standing a minute or two in silence made a preliminary motion of withdrawal.

"Beautiful your plants are looking," said Mrs. Silk, glancing over at his window; "I can't think what you do to 'em."

The gratified Mr. Wilks began to explain. It appeared that plants wanted almost as much looking after as daughters.

"I should like to see 'em close," said Mrs. Silk. "Come in and 'ave a look at 'em," responded her neighbour.

Mrs. Silk hesitated and displayed a maidenly coyness far in excess of the needs of the situation. Then she stepped across, and five seconds later the two matrons, with consternation writ large upon their faces, appeared at their doors again and, exchanging glances across the alley, met in the centre.

They were more surprised an evening or two later to see Mr. Wilks leave his house to pay a return visit, bearing in his hand a small bunch of his cherished blooms. That they were blooms which would have paid the debt of Nature in a few hours at most in no way detracted from the widow's expressions of pleasure at receiving them, and Mr. Wilks, who had been invited over to cheer up Mr. Silk, who was in a particularly black mood, sat and smiled like a detected philanthropist as she placed them in water.

"Good evenin', Teddy," he said, breezily, with a side-glance at his hostess. "What a lovely day we've 'ad."

"So bright," said Mrs. Silk, nodding with spirit.

Mr. Wilks sat down and gave vent to such a cheerful laugh that the ornaments on the mantelpiece shook with it. "It's good to be alive," he declared.

"Ah, you enjoy your life, Mr. Wilks," said the widow.

"Enjoy it!" roared Mr. Wilks; "enjoy it! Why shouldn't I? Why shouldn't everybody enjoy their lives? It was what they was given to us for."

"So they was," affirmed Mrs. Silk; "nobody can deny that; not if they try."

"Nobody wants to deny it, ma'am," retorted Mr. Wilks, in the high voice he kept for cheering-up purposes. "I enjoy every day o' my life."

He filled his pipe, chuckling serenely, and having lit it sat and enjoyed that. Mrs. Silk retired for a space, and returning with a jug of ale poured him out a glass and set it by his elbow.

"Here's your good 'ealth, ma'am," said Mr. Wilks, raising it. "Here's yours, Teddy—a long life and a 'appy one."

Mr. Silk turned listlessly. "I don't want a long life," he remarked.

His mother and her visitor exchanged glances.

"That's 'ow 'e goes on," remarked the former, in an audible whisper. Mr. Wilks nodded, reassuringly.

"I 'ad them ideas once," he said, "but they go off. If you could only live to see Teddy at the age o' ninety-five, 'e wouldn't want to go then. 'E'd say it was crool hard, being cut off in the flower of 'is youth."

Mrs. Silk laughed gaily and Mr. Wilks bellowed a gruff accompaniment. Mr. Edward Silk eyed them pityingly.

"That's the 'ardship of it," he said, slowly, as he looked round from his seat by the fireplace; "that's where the 'ollowness of things comes in. That's where I envy Mr. Wilks."

"Envy me?" said the smiling visitor; "what for?"

"Because you're so near the grave," said Mr. Silk.

Mr. Wilks, who was taking another draught of beer, put the glass down and eyed him fixedly.

"That's why I envy you," continued the other.

"I don't want to live, and you do, and yet I dessay I shall be walking about forty and fifty years after you're dead and forgotten."

"Wot d'ye mean—near the grave?" inquired

Mr. Wilks, somewhat shortly.

"I was referring to your age," replied the other; "it's strange to see 'ow the aged 'ang on to life. You can't 'ave much pleasure at your time o' life. And you're all alone; the last withered branch left."

"Withered branch!" began Mr. Wilks; "'ere, look 'ere, Teddy——"

"All the others 'ave gone," pursued Mr. Silk, and they're beckoning to you."

"Let 'em beckon," said Mr. Wilks, coldly. "I'm not going yet."

"You're not young," said Mr. Silk, gazing meditatively at the grate, "and I envy you that. It can only be a matter of a year or two at most before you are sleeping your last long sleep."

"Teddy!" protested Mrs. Silk.

"It's true, mother," said the melancholy youth. "Mr. Wilks is old. Why should 'e mind being told of it? If 'e had 'ad the trouble I've 'ad 'e'd be glad to go. But he'll 'ave to go, whether 'e likes it or not. It might be to-night. Who can tell?"

Mr. Wilks, unasked, poured himself out another glass of ale, and drank it off with the air of a man who intended to make sure of that. It seemed a trifle more flat than the last.

"So many men o' your age and thereabouts," continued Mr. Silk, "think that they're going to live on to eighty or ninety, but there's very few of 'em do. It's only a short while, Mr. Wilks, and the little children'll be running about over your grave and picking daisies off of it."

"Ho, will they?" said the irritated Mr. Wilks; "they'd better not let me catch 'em at it, that's all."

"He's always talking like that now," said Mrs. Silk, not without a certain pride in her tones; "that's why I asked you in to cheer 'im up."

"All your troubles'll be over then," continued the warning voice, "and in a month or two even your name'll be forgotten. That's the way of the world. Think 'ow soon the last five years of your life 'ave passed; the next five'll pass ten times as fast even if you live as long, which ain't likely."

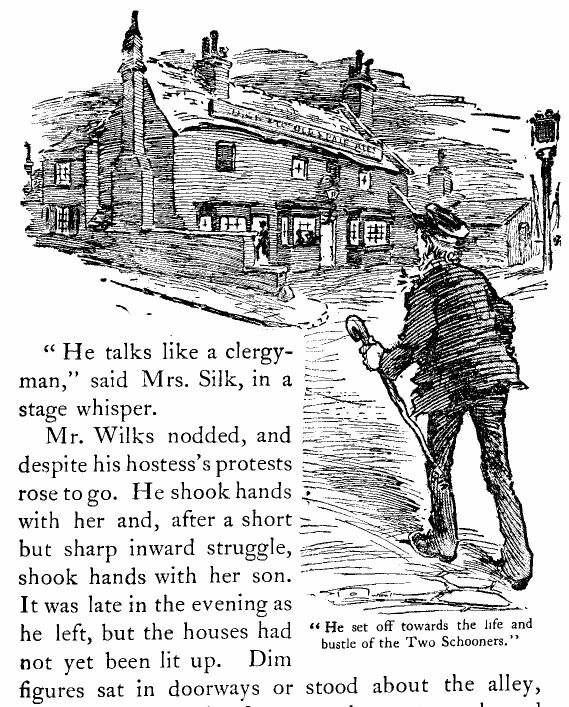

"He talks like a clergyman," said Mrs. Silk, in a stage whisper.

Mr. Wilks nodded, and despite his hostess's protests rose to go. He shook hands with her and, after a short but sharp inward struggle, shook hands with her son. It was late in the evening as he left, but the houses had not yet been lit up. Dim figures sat in doorways or stood about the alley, and there was an air of peace and rest strangely and uncomfortably in keeping with the conversation to which he had just been listening. He looked in at his own door; the furniture seemed stiffer than usual and the tick of the clock more deliberate. He closed the door again and, taking a deep breath, set off towards the life and bustle of the Two Schooners.

Time failed to soften the captain's ideas concerning his son's engagement, and all mention of the subject in the house was strictly forbidden. Occasionally he was favoured with a glimpse of his son and Miss Kybird out together, a sight which imparted such a flavour to his temper and ordinary intercourse that Mrs. Kingdom, in unconscious imitation of Mr. James Hardy, began to count the days which must elapse before her niece's return from London. His ill-temper even infected the other members of the household, and Mrs. Kingdom sat brooding in her bedroom all one afternoon, because Bella had called her an "overbearing dish-pot."

The finishing touch to his patience was supplied by a little misunderstanding between Mr. Kybird and the police. For the second time in his career the shopkeeper appeared before the magistrates to explain the circumstances in which he had purchased stolen property, and for the second time he left the court without a stain on his character, but with a significant magisterial caution not to appear there again.

Jack Nugent gave evidence in the case, and some of his replies were deemed worthy of reproduction in the Sunwich Herald, a circumstance which lost the proprietors a subscriber of many years' standing.

One by one various schemes for preventing his son's projected alliance were dismissed as impracticable. A cherished design of confining him in an asylum for the mentally afflicted until such time as he should have regained his senses was spoilt by the refusal of Dr. Murchison to arrange for the necessary certificate; a refusal which was like to have been fraught with serious consequences to that gentleman's hopes of entering the captain's family.

Brooding over his wrongs the captain, a day or two after his daughter's return, strolled slowly down towards the harbour. It was afternoon, and the short winter day was already drawing towards a close. The shipping looked cold and desolate in the greyness, but a bustle of work prevailed on the Conqueror, which was nearly ready for sea again. The captain's gaze wandered from his old craft to the small vessels dotted about the harbour and finally dwelt admiringly on the lines of the whaler Seabird, which had put in a few days before as the result of a slight collision with a fishing-boat. She was high out of the water and beautifully rigged. A dog ran up and down her decks barking, and a couple of squat figures leaned over the bulwarks gazing stolidly ashore.

There was something about the vessel which took his fancy, and he stood for some time on the edge of the quay, looking at her. In a day or two she would sail for a voyage the length of which would depend upon her success; a voyage which would for a long period keep all on board of her out of the mischief which so easily happens ashore. If only Jack——

He started and stared more intently than before. He was not an imaginative man, but he had in his mind's eye a sudden vision of his only son waving farewells from the deck of the whaler as she emerged from the harbour into the open sea, while Amelia Kybird tore her yellow locks ashore. It was a vision to cheer any self-respecting father's heart, and he brought his mind back with some regret to the reality of the anchored ship.

He walked home slowly. At the Kybirds' door the proprietor, smoking a short clay pipe, eyed him with furtive glee as he passed. Farther along the road the Hardys, father and son, stepped briskly together. Altogether a trying walk, and calculated to make him more dissatisfied than ever with the present state of affairs. When his daughter shook her head at him and accused him of going off on a solitary frolic his stock of patience gave out entirely.

A thoughtful night led to a visit to Mr. Wilks the following evening. It required a great deal of deliberation on his part before he could make up his mind to the step, but he needed his old steward's assistance in a little plan he had conceived for his son's benefit, and for the first time in his life he paid him the supreme honour of a call.

The honour was so unexpected that Mr. Wilks, coming into the parlour in response to the tapping of the captain's stick on the floor, stood for a short time eyeing him in dismay. Only two minutes before he had taken Mr. James Hardy into the kitchen to point out the interior beauties of an ancient clock, and the situation simply appalled him. The captain greeted him almost politely and bade him sit down. Mr. Wilks smiled faintly and caught his breath.

"Sit down," repeated the captain.

"I've left something in the kitchen, sir," said Mr. Wilks. "I'll be back in half a minute."

The captain nodded. In the kitchen Mr. Wilks rapidly and incoherently explained the situation to Mr. Hardy.

"I'll sit here," said the latter, drawing up a comfortable oak chair to the stove.

"You see, he don't know that we know each other," explained the apologetic steward, "but I don't like leaving you in the kitchen."

"I'm all right," said Hardy; "don't you trouble about me."

He waved him away, and Mr. Wilks, still pale, closed the door behind him and, rejoining the captain, sat down on the extreme edge of a chair and waited.

"I've come to see you on a little matter of business," said his visitor.

Mr. Wilks smiled; then, feeling that perhaps that was not quite the right thing to do, looked serious again.

"I came to see you about my—my son," continued the captain.

"Yes, sir," said Mr. Wilks. "Master Jack, you mean?"

"I've only got one son," said the other, unpleasantly, "unless you happen to know of any more."

Mr. Wilks almost fell off the edge of the chair in his haste to disclaim any such knowledge. His ideas were in a ferment, and the guilty knowledge of what he had left in the kitchen added to his confusion. And just at that moment the door opened and Miss Nugent came briskly in.

Her surprise at seeing her father ensconced in a chair by the fire led to a rapid volley of questions. The captain, in lieu of answering them, asked another.

"What do you want here?"

"I have come to see Sam," said Miss Nugent. "Fancy seeing you here! How are you, Sam?"

"Pretty well, miss, thank'ee," replied Mr. Wilks, "considering," he added, truthfully, after a moment's reflection.

Miss Nugent dropped into a chair and put her feet on the fender. Her father eyed her restlessly.

"I came here to speak to Sam about a private matter," he said, abruptly.

"Private matter," said his daughter, looking round in surprise. "What about?"

"A private matter," repeated Captain Nugent. "Suppose you come in some other time."

Kate Nugent sighed and took her feet from the fender. "I'll go and wait in the kitchen," she said, crossing to the door.

Both men protested. The captain because it ill-assorted with his dignity for his daughter to sit in the kitchen, and Mr. Wilks because of the visitor already there. The face of the steward, indeed, took on such extraordinary expressions in his endeavour to convey private information to the girl that she gazed at him in silent amazement. Then she turned the handle of the door and, passing through, closed it with a bang which was final.

Mr. Wilks stood spellbound, but nothing happened. There was no cry of surprise; no hasty reappearance of an indignant Kate Nugent. His features working nervously he resumed his seat and gazed dutifully at his superior officer.

"I suppose you've heard that my son is going to get married?" said the latter.

"I couldn't help hearing of it, sir," said the steward in self defence— "nobody could."

"He's going to marry that yellow-headed Jezebel of Kybird's," said the captain, staring at the fire.

Mr. Wilks murmured that he couldn't understand anybody liking yellow hair, and, more than that, the general opinion of the ladies in Fullalove Alley was that it was dyed.

"I'm going to ship him on the Seabird," continued the captain. "She'll probably be away for a year or two, and, in the meantime, this girl will probably marry somebody else. Especially if she doesn't know what has become of him. He can't get into mischief aboard ship."

"No, sir," said the wondering Mr. Wilks. "Is Master Jack agreeable to going, sir?"

"That's nothing to do with it," said the captain, sharply.

"No, sir," said Mr. Wilks, "o' course not. I was only a sort o' wondering how he was going to be persuaded to go if 'e ain't."

"That's what I came here about," said the other. "I want you to go and fix it up with Nathan Smith."

"Do you want 'im to be crimped, sir?" stammered Mr. Wilks.

"I want him shipped aboard the Seabird," returned the other, "and Smith's the man to do it."

"It's a very hard thing to do in these days, sir," said Mr. Wilks, shaking his head. "What with signing on aboard the day before the ship sails, and before the Board o' Trade officers, I'm sure it's a wonder that anybody goes to sea at all."

"You leave that to Smith," said the captain, impatiently. "The Seabird sails on Friday morning's tide. Tell Smith I'll arrange to meet my son here on Thursday night, and that he must have some liquor for us and a fly waiting on the beach."

Mr. Wilks wriggled: "But what about signing on, sir?" he inquired.

"He won't sign on," said the captain, "he'll be a stowaway. Smith must get him smuggled aboard, and bribe the hands to let him lie hidden in the fo'c's'le. The Seabird won't put back to put him ashore. Here is five pounds; give Smith two or three now, and the remainder when the job is done."

The steward took the money reluctantly and, plucking up his courage, looked his old master in the face.

"It's a 'ard life afore the mast, sir," he said, slowly.

"Rubbish!" was the reply. "It'll make a man of him. Besides, what's it got to do with you?"

"I don't care about the job, sir," said Mr. Wilks, bravely.

"What's that got to do with it?" demanded the other, frowning. "You go and fix it up with Nathan Smith as soon as possible."

Mr. Wilks shuffled his feet and strove to remind himself that he was a gentleman of independent means, and could please himself.

"I've known 'im since he was a baby," he murmured, defiantly.

"I don't want to hear anything more from you, Wilks," said the captain, in a hard voice. "Those are my orders, and you had better see that they are carried out. My son will be one of the first to thank you later on for getting him out of such a mess."

Mr. Wilks's brow cleared somewhat. "I s'pose Miss Kate 'ud be pleased too," he remarked, hope-fully.

"Of course she will," said the captain. "Now I look to you, Wilks, to manage this thing properly. I wouldn't trust anybody else, and you've never disappointed me yet."

The steward gasped and, doubting whether he had heard aright, looked towards his old master, but in vain, for the confirmation of further compliments. In all his long years of service he had never been praised by him before. He leaned forward eagerly and began to discuss ways and means.

In the next room conversation was also proceeding, but fitfully. Miss Nugent's consternation when she closed the door behind her and found herself face to face with Mr. Hardy was difficult of concealment. Too late she understood the facial contortions of Mr. Wilks, and, resigning herself to the inevitable, accepted the chair placed for her by the highly pleased Jem, and sat regarding him calmly from the other side of the fender.

"I am waiting here for my father," she said, in explanation.

"In deference to Wilks's terrors I am waiting here until he has gone," said Hardy, with a half smile.

There was a pause. "I hope that he will not be long," said the girl.

"Thank you," returned Hardy, wilfully misunderstanding, "but I am in no hurry."

He gazed at her with admiration. The cold air had heightened her colour, and the brightness of her eyes shamed the solitary candle which lit up the array of burnished metal on the mantelpiece.

"I hope you enjoyed your visit to London," he said.

Before replying Miss Nugent favoured him with a glance designed to express surprise at least at his knowledge of her movements. "Very much, thank you," she said, at last.

Mr. Hardy, still looking at her with much comfort to himself, felt an insane desire to tell her how much she had been missed by one person at least in Sunwich. Saved from this suicidal folly by the little common sense which had survived the shock of her sudden appearance, he gave the information indirectly.

"Quite a long stay," he murmured; "three months and three days; no, three months and two days."

A sudden wave of colour swept over the girl's face at the ingenuity of this mode of attack. She was used to attention and took compliments as her due, but the significant audacity of this one baffled her. She sat with downcast eyes looking at the fender occasionally glancing from the corner of her eye to see whether he was preparing to renew the assault. He had certainly changed from the Jem Hardy of olden days. She had a faint idea that his taste had improved.

"Wilks keeps his house in good order," said Hardy, looking round.

"Yes," said the girl.