Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 326, August 9, 1828

Author: Various

Release date: December 1, 2003 [eBook #10475]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram, Charles Bidwell, and the Prooject Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

| Vol. 12. No. 326. | SATURDAY, AUGUST 9, 1828. | [PRICE 2d. |

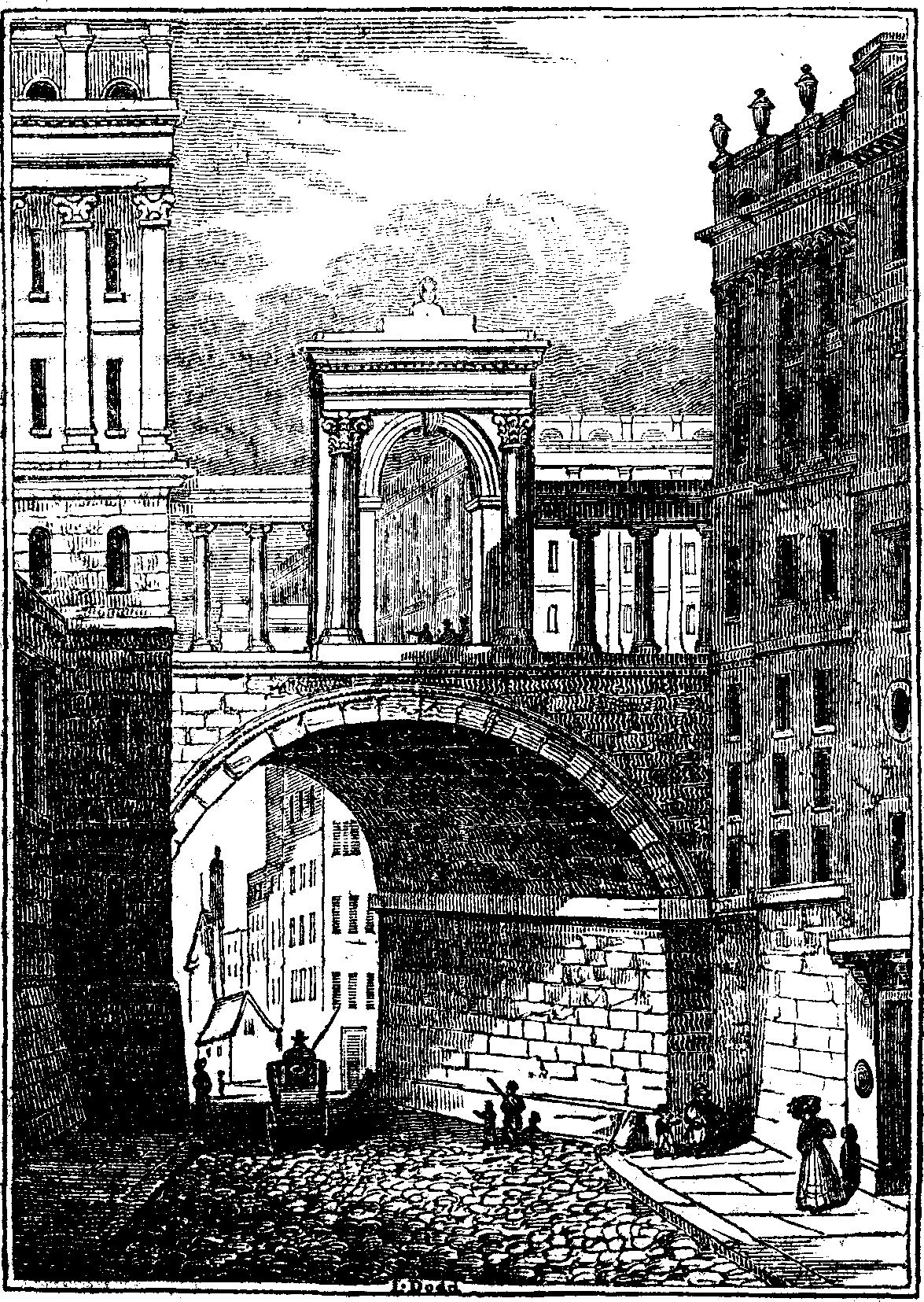

Edinburgh, "the Queen of the North," abounds in splendid specimens of classical architecture. Since the year 1769, when the building of the New Town commenced, its improvement has been prosecuted with extraordinary zeal; consequently, the city has not only been extended on all sides, but has received the addition of some magnificent public edifices, while the access to it from every quarter has been greatly facilitated and embellished. Of the last-mentioned improvement our engraving is a mere vignette, but it deserves to rank among the most superb of those additions.

The inconvenience of the access to Edinburgh by the great London road was long a subject of general regret. In entering the city from this quarter, the road lay through narrow and inconvenient streets, forming an approach no way suited to the general elegance of the place. In 1814, however, a magnificent entrance was commenced across the Calton Hill, between which and Prince's street a deep ravine intervened, which was formerly occupied with old and ill-built streets. In order to connect the hill with Prince's-street, all these have been swept away, and an elegant arch, called Regent Bridge, has been thrown over the hollow, which makes the descent from the hill into this street easy and agreeable. Thus, in place of being carried, as formerly, through long and narrow streets, the great road from [pg 82]the east into Edinburgh sweeps along the side of the steep and singular elevation of the Calton Hill; whence the traveller has first a view of the Old Town, with its elevated buildings crowning the summit of the adjacent ridges, and rising upon the eye in imposing masses; and, afterwards, of the New Town finely contrasted with the Old, in the regularity and elegance of its general outline.

Regent Bridge was begun in 1816, and finished in 1819. The arch is semicircular, and fifty feet wide. At the north front it is forty-five feet in height, and at the south front sixty-four feet two inches, the difference being occasioned by the ground declining to the south. The roadway is formed by a number of reverse arches on each side. The great arch is ornamented on the south and north by two open arches, supported by elegant columns of the Corinthian order. The whole property purchased to open the communication to the city by this bridge cost 52,000l, and the building areas sold for the immense sum of 35,000l. The street along the bridge is called Waterloo-place, as it was founded in the year on which that memorable battle was fought.

The engraving1 is an interesting picture of classic beauty; and as the "approaches" and proposed "dry arches" to the New London Bridge are now becoming matters of speculative interest, we hope this entrance to our metropolis will ultimately present a similar display of architectural elegance. LONDON, with all her opulence, ought not to yield in comparison with any city in the world; and it is high time that the march of taste be quickened in this quarter.

Weep, for the word is spoken—

Mourn, for the knell hath knoll'd—

The master chord is broken,

And the master's hand is cold!

Romance hath lost her minstrel,

No more his magic strain

Shall throw a sweeter spell around,

The legends of Almaine.

His fame had flown before him

To many a foreign land,

His lays are sung by every tongue,

And harp'd by every hand!

He came to cull fresh laurels,

But fate was in their breath,

And turn'd his march of triumph

Into a dirge of death.

O! all who knew him lov'd him,

For with his mighty mind,

He bore himself so meekly,

His heart it was so kind!

His wildly warbling melodies,

The storms that round them roll,

Are types of the simplicity

And grandeur of his soul.

Though years of ceaseless suffering

Had worn him to a shade,

So patient was his spirit,

No wayward plaint he made.

E'en death itself seem'd loath to scare

His victim pure and mild;

And stole upon him quietly

As slumber o'er a child.

Weep, for the word is spoken—

Mourn, for the knell hath knoll'd—

The master chord is broken,

And the master's hand is cold!

The master chord is broken,

And the master's hand is cold!

PLANCHE.

It is impossible at this time of day, to foretell how the future destinies of Europe may be influenced by the subject of these lines. To use the words of the talented author of the Improvisatrice, "Poetry needs no preface." However in this instance, a few remarks may not be uninteresting. Until I met with the following stanzas, I was not aware that Napoleon had been a votary of the muses. He has certainly climbed the Parnassian mount with considerable success, whether we take the interest of the subject, or the correctness of the versification into consideration. Memorials like these of such a man, are, in the highest degree, interesting; they serve to display the man, divested of the "pomp and circumstance" of royalty. That Napoleon had many faults cannot be disputed, but it is equally clear that he possessed many virtues the world never gave him credit for:—"Posterity will do me justice."

I subjoin two translations of the beautiful lines written by Napoleon at St. Helena, on the portrait of his son. The love he bore to his son was carried to enthusiasm. According to those persons who had access to his society at St. Helena, his young heir was the continual object of his solicitude during the period of seven years, "For him alone," he said, "I returned from the Island of Elba, and if I still form some expectations on earth, they are also for him." He has declared to several of his suite, that he every day suffered the greatest anxiety on his account. Since I met with these lines however, I have found that Napoleon had in his youth composed a poem on Corsica, some extracts of which are to be found in "Les Annales de l'Europe" a German collection. He was exceedingly anxious in after life to destroy the copies of this poem which had been circulated, and [pg 83] bought and procured them by every means in his power for the purpose of destroying them; it is probable not a single copy is in existence at the present period. It has been remarked, that, "it requires nothing short of the solitude of exile, and the idolatry which he manifested for his son, to inspire him once more. In neither of the original poems is it indicated which he preferred."

VYVYAN.

Delightful image of my much loved boy!

Behold his eyes, his looks, his cherub smile!

No more, alas! will he enkindle joy,

Nor on some kindlier shore my woes beguile.

My son! my darling son! wert thou but here,

My bosom should receive thy lovely form:

Thou'dst soothe my gloomy hours with converse dear:

Serenely mild behold the lowering storm.

I'd be the partner of thy infant cares,

And pour instruction o'er thy expanding mind;

Whilst in thy heart, in my declining years,

My wearied soul should an asylum find.

My wrongs—my cares—should be forgot with thee,

My power—imperial dignities—renown—

This rock itself would be a heaven to me;

Thine arms more cherished than the victor's crown.

O! in thine arms, my son! I could forget that fame

Shall give me, through all time, a never dying name.

(Signed.) NAPOLEON.

Another version is subjoined of lines, "To the Portrait of My Son."

O! Cherished image of my infant heir!

Thy surface does his lineaments impart:—

But ah! thou liv'st not. On this rock so bare

His living form shall never glad my heart.

My second-self! how would'st thy presence cheer

The settled sadness of thy hapless sire!

Thine infancy with tenderness I'd rear,

And thou should'st warm my age with youthful fire.

In thee, a truly glorious crown I'd find;

With thee, upon this rock a heaven should own:

Thy kiss would chase past conquests from my mind,

Which raised me demi-god on Gallia's throne.

(Signed.) NAPOLEON.

Observing in Number 323 of the MIRROR, an article respecting blue, as the appointed colour for the clothes of certain descriptions of persons, it may, perhaps, not be wholly irrelevant to observe that Bentley, in his "Dissertation on Phalaris," page 258, mentions blue as the costume of his guards, and quotes Cicero's "Tusculan Questions," lib. 5, for his authority. I cannot at present turn to the passage in Cicero, but Bentley's quotation may surely be accepted as evidence of the existence of the passage.

Twickenham. H. H.

On the trial of Henry Marshall, Dec. 4, 1723, for murder and deer-stealing, a very remarkable circumstance took place. Sentence of death had no sooner been pronounced on this offender, than he was immediately deprived of the use of his tongue; nor did he recover his speech till a few hours preceding his execution.

G. W. N.

July, 1736—Reynolds, condemned upon the Black Act, for going armed in disguise, in pulling down Lothbury turn-pike, with one Baylis, (reprieved, and transported for 14 years,) was carried to Tyburn, where, having prayed and sung psalms, he was turned off, and being thought dead, was cut down by the hangman as usual, who had procured a hole to be dug at some distance from the gallows, to bury him in; but just as they had put him into his coffin, and were about to fasten him up, he thrust back the lid, and to the astonishment of the spectators, placed his hands on the sides of the coffin in order to raise himself up. Some of the people, in their first surprise, were for knocking him on the head; but the executioner insisted upon hanging him up again; when the mob, thinking otherwise, cried, "Save his life," and fell upon the poor executioner, (who stickled hard for fulfilling the law,) and beat him in a miserable manner; they then carried the prisoner to a public-house at Bayswater, where he was put to bed; he vomited about three pints of blood, and it was thought he would recover; but he died soon after. The sheriffs' officers, believing the prisoner dead, had retired from the place of execution before he was cut down.

Sept. 3, 1736.—Venham and Harding, two malefactors, were executed this day at Bristol. After they were cut down, Venham was perceived to have life in him, when put in the coffin; and some lightermen and others, having carried him to a house, a surgeon, whom they sent for, immediately opened a vein, which so far recovered his senses, that he had the use of speech, sat upright, rubbed his knees, shook hands with divers persons he knew, [pg 84] and to all appearance a perfect recovery was expected. But notwithstanding this, he died about eleven o'clock in great agony, his bowels being very much convulsed, as appeared by his rolling from one side to the other.

It is remarkable also, that Harding came to life again, and was carried to Bridewell, and the next day to Newgate, where several people visited him and gave him money, who were very inquisitive whether he remembered the manner of his execution; to which he replied, he could only remember his having been at the gallows, and knew nothing of Venham being with him.

G. K.

In the happy period of the golden age when all the celestial inhabitants descended upon the earth and conversed familiarly with mortals, among the most cherished of the heavenly powers were twins, the offspring of Jupiter, Love, and Joy. Wherever they appeared, flowers sprung up beneath their feet, the sun shone with a brighter radiance, and all nature seemed embellished by their presence; they were inseparable companions, and their growing attachment was favoured by Jupiter, who had decreed that a lasting union should be solemnized between them as soon as they arrived at mature years. But in the meantime, the sons of men deviated from their native innocence; vice and ruin over-ran the earth with giant strides; and Astrea with her train of celestial visitants, forsook their polluted abode; Love alone remained, having been stolen away by Hope, who was his nurse, and conveyed by her to the forest of Arcadia, where he was brought up amongst the shepherds. But Jupiter assigned him a different partner, and commanded him to espouse Sorrow, the daughter of Até. He complied with reluctance, for her features were harsh, her eyes sunken, her forehead contracted into perpetual wrinkles, and her temples encircled with a wreath of cypress and wormwood. From this union sprung a virgin, in whom might be traced a strong resemblance to both her parents; but the sullen and unamiable features of her mother were so blended with the sweetness of the father, that her countenance, though mournful, was highly pleasing. The maids and shepherds gathered round and called her Pity. A red-breast was observed to build in the cabin where she was born; and while she was yet an infant, a dove, pursued by a hawk, flew for refuge into her bosom. She had a dejected appearance, but so soft and gentle a mien, that she was beloved to enthusiasm. Her voice was low and plaintive, but inexpressibly sweet; and she loved to lie for hours on the banks of some wild and melancholy stream singing to her lute. She taught men to weep, for she took a strange delight in tears; and often when the virgins of the hamlet were assembled at their evening sports, she would steal in among them and captivate their hearts by her tales of charming sadness. She wore on her head a garland, composed of her father's myrtles twisted with her mother's cypress. One day as she sat musing by the waters of Helicon, her tears by chance fell into the spring; and ever since, the muses' spring has tasted of the infusion. Pity was commanded by Jupiter to follow the steps of her mother through the world, dropping balm into the wounds she made, and binding up the hearts she had broken. She follows with her hair loose, her bosom bare and throbbing, her garments torn by the briars, and her feet bleeding with the roughness of the path. The nymph is mortal, for so is her mother; and when she has finished her destined course upon earth, they shall both expire together, and Love be again united to Joy, his immortal and long-betrothed bride.

There is a volcanic country on the left bank between Remagen and Andernach, highly interesting to the naturalist, but I believe not visited by the generality of travellers. The late accounts, however, of the formations of a similar kind in Auvergne and Clermont, in the centre of France, and the speculations to which these phenomena have given rise, determined me to explore this district whilst I was in the neighbourhood. Bidding adieu, therefore, to the green little island of Nonnenworth, I made the journey to Brohl, a convenient day's walk of sixteen miles, passing through Oberwinter, Remagen, and Breysig, and the other white and slated villages that enliven the river. It is here the valley of the Rhine narrows, and the succession of ridges and dales which the road skirts, are sometimes entirely barren, at others thickly covered with vines and fruit-trees. Though the former plant is pleasing in the tints of its leaf, and in the idea of cultivation and plenty that its thick plantations present, yet there is a stiffness in the regularity [pg 85] in which it grows, propped up by sticks; and it is so short, that one's fancy as to its luxuriance, (especially if formed from such poetry as Childe Harold,) is certainly disappointed. I made a digression from the road up the little river Aar, which falls into the Rhine near Sinzig. A more striking picture you cannot imagine. The stream is remarkably clear and rapid, the bottom rocky, and its banks, for a considerable distance, are literally perpendicular rocks. The Aar is a perfect specimen of the mountain torrent; it rises in the Eiffel mountains; and, I am told, in the winter does much mischief by inundations. It put me in mind of the Welsh rivulets, particularly some parts of the Dee. This détour having taken up more time than I expected, I reached Brohl, late, but in time for the supper at the rustic Gasthoff, which, with a flask of Rhenish wine, and the company of an agreeable German tourist who was staying there, made ample amends for the fatigues of the day.

In setting out from Brohl by the stream of the same name, which runs down from the Lake of Laach, where I was struck with the pieces of pumice-stone, and the charred remains of herbs and stalks of trees scattered over the marshes. I soon came to the valley, the sides of which are composed of what is called, in the language of geology, tufa, and in that of the country, dukstein, or trass. It is a stone, or a hard clay, of a dull blueish colour, and when dry, it assumes a shade of light gray. An immense quantity is quarried throughout the valley, and is sent down the Rhine to Holland, where it is in great request for building. The village of Nippes owes its origin to the trade in trass, having been founded by a Dutchman, who settled there about a century ago for the convenience of exportation. The lower part of the mass is the hardest and most compact, and is therefore preferred by the quarrymen; as it rises, the upper part becomes loose and sandy, and unfit for use. You must not suppose the stream to be clear like the Aar, for it is as thick as pea-soup, and about the same colour, being in fact a river of trass in solution. The banks, however, are picturesque and well wooded, particularly at Schweppenbourg, an old castle of peculiar architecture, built on an elevated rock, and formerly belonging to the family of Metternich, (God save the mark!) The tower is surrounded with caverns and halls, hollowed out of the trass stone, and profusely ornamented with fine oaks, pines, and spreading beech trees. You may almost fancy yourself on magic ground, and looking on a fairy castle, so peculiar is the effect. I next reached Burgbrohl and Wassenach, passing several of the trass mills, for the stone is in many places hard enough for mill-stones, and there is a considerable trade in them to Holland, and thence to England and other countries. Half an hour next brought me to the summit of the Feitsberg, one of the hills forming the circumference of the lake; here I enjoyed a magnificent prospect on the one side of the lake, well clothed with wood, with the old six-towered abbey on its bank, and the heights of the Eiffel chain enclosing it; on the other side, the view was so extensive as to give me a glimpse of Ehrenbreitstein, and of the line of hills from thence to the Siebengebrige. Though my object in climbing the Feitsberg was very different, my surprise and delight in unexpectedly catching Ehrenbreitstein at the distance of twenty-four miles even served to withdraw my attention some time from geologizing, or from the scene close under me. I recollect the same sensation on descrying Gravelines sometime ago from the heights of Dover Castle, not believing the distance to be within the powers of the telescope. True indeed is it that

"Tis distance lends enchantment to the view.

And robes the mountain in its azure hue."

I was now in a rude and barren country, presenting a strong contrast to the soft scenery I had left, and consisting of an elevated mountain plateau, or table land of slate of the Greywacke sort, the heights on the eastern side of the Rhine being of the same level, and the channel of the river appearing as a narrow valley, which the eye overlooks entirely. This table land is studded with isolated hills of volcanic formation, and of a conical form, some of them having central funnels or craters, from which the ancient eruptions have issued. The most complete are the Hirschenberg, near Burgbrohl, the Bousenberg, between that village and Olburg, the Poter, Pellenberg, and the Camillenberg, which last rises about one thousand feet above the level of the surrounding surface. There are many others extending for some distance in the Eiffel chain and in the vicinity, but those I have mentioned are sufficient to guide the footsteps of the inquirer. The basin of the Lake of Laach is nearly circular and crateriform; it is a mile and a half long, and about a mile and a quarter in breadth. Its average depth is two hundred feet, but it is full of holes, the measure of which is very uncertain. Its water is blueish, very cold, and of a nasty brackish taste. It has been examined by several geologists, British and foreign, among whom is the [pg 86] famous Humboldt, and there is no doubt that this great reservoir is the crater of an extinct volcano. The fragments and minerals thrown up on the banks are analogous to those found in other volcanic countries; and on one side (that towards Nieder-mennig) is a regular rock of continued lava, which is supposed to have flowed from the crater during the last eruption. Mr. Scrope, whose opinion is entitled to great weight, thinks it not improbable that this may have been the eruption recorded by Tacitus, (13 lib. Annal.,) as having ravaged the country of the Initones, near Cologne, in the reign of Nero. I should not forget to mention that there is a cavern within the basin of the lake, the air of which is so stifling and noxious, that animals die if forced to remain in it, and lights are extinguished by the gas—phenomena precisely similar to those of the well-known Grotto del Cane, near Naples.

While I am on the subject of volcanic phenomena, I may as well add a word on the origin of the trass or tufa, which is so thickly spread over this country. It is similar to that found near Naples, at Mont d'Or, Carbal, and other parts of Italy; and, indeed, all the products of the latter district are pretty nearly the same as these, allowing for the difference of a slate surface in the one case, and a sandy and alluvial soil in the other. The idea of the trass having any connexion with a deluge, is, I believe, now exploded; and geologists have agreed that it is the actual substance ejected by the volcano, subsided into a firm paste. The rain has always been observed to fall heavily after eruptions, and the water running down the sides of the hills, has formed this crust, which makes the bottom and sides of the Laach. The same causes are in action now; and if ever the lake should rise so high as to burst its banks, it would overflow the whole country, and carry terrible destruction with it. Such an event was actually foreseen by the sagacious monks who formerly inhabited the abbey, for they cut a canal nearly a mile long, to give the water vent; and the discharge by it continues to this day. The abbey is now untenanted, and is in a deplorable state of ruin; it was once celebrated for its hospitality and a fine gallery of pictures; all, however, have vanished, and the ruins are now the property of M. Delius, a magistrate of Treves. The situation is so beautiful, surrounded as it is with fine timber, that one would suppose it worth his while to repair the place, particularly as stone is so plentiful in the neighbourhood. It forms, however, as it is, a picturesque addition to the interest of the excursion to the lake, I returned by the mineral spring of Heilbrunn, well satisfied with my inspection of the country. The distance from Brohl to the abbey is little more than five miles, and it is one which I would advise all tourists on the Rhine to make if they have time, whether they be geologists or non-geologists. I fancied I had a clearer conception of. Aetna and Vesuvius, and the living fires, from having witnessed the funnels of the extinct ones. At all events, though little is known as to the causes of volcanic phenomena, enough is ascertained to convince us that subterranean fire exists under the whole of Europe, there not being one country or district exempt from occasional earthquakes, or some such signs of terror.

D.

The garden contains upwards of two acres, with a gravel-walk under the windows. A Gothic porch has been added, the bow-windows being surmounted with the same kind of parapet as the house, somewhat more ornamental. It lies to the morning sun; the road to the house, on the north, enters through a large arch. The garden is on a slope, commanding views of the surrounding country, with the tower of Calne in front, the woods of Bowood on the right, and the mansion and woods of Walter Heneage, Esq. Towards the south. The view to the south-east is terminated by the last chalky cliffs of the Marlborough downs, extending to within a few miles of Swindon. In the garden, a winding path from the gravel-walk, in front of the house, leads to a small piece of water, originally a square pond.

This walk, as it approaches the water, leads into a darker shade, and descending some steps, placed to give a picturesque appearance to the bank, you enter a kind of cave, with a dripping rill, which falls into the water below, whose bank is broken by thorns, and hazels, and poplars, among darker shrubs. Here an urn appears with the following inscription:—"M.S. Henrici Bowles, qui ad Calpen, febre ibi exitiali grassante, publicè missus, ipse miserrimè periit—1804. Fratri posuit."—Passing round the water, you come to an arched walk of hazels, which leads to the green in front of the house, where, dipping a small slope, the path passes near an old and ivied elm. As this seat looks on the magnificent line [pg 87]of Bowood park and plantations, the obvious thought could not be well avoided:

"When in thy sight another's vast domain

Spreads its dark sweep of woods, dost thou complain?

Nay! rather thank the God who placed thy state

Above the lowly, but beneath the great;

And still his name with gratitude revere,

Who bless'd the sabbath of thy leisure here."

The walk leads round a plantation of shrubs, to the bottom of the lawn, from whence is seen a fountain, between a laurel arch; and through a dark passage a gray sun-dial appears among beds of flowers, opposite the fountain.

The sun-dial, a small, antique, twisted column, gray with age, was probably the dial of the abbot of Malmesbury, and counted his hours when at the adjoining lodge; for it was taken from the garden of the farm-house, which had originally been the summer retirement of this mitred lord. It has the appearance of being monastic, but a more ornate capital has been added, the plate on which bears the date of 1688. I must again venture to give the appropriate inscription:—

"To count the brief and unreturning hours,

This Sun-Dial was placed among the flowers,

Which came forth in their beauty—smiled and died,

Blooming and withering round its ancient side.

Mortal, thy day is passing—see that flower,

And think upon the Shadow and the Hour!"

The whole of the small green slope is here dotted with beds of flowers; a step, into some rock-work, leads to a kind of hermit's oratory, with crucifix and stained glass, built to receive the shattered fragments, as their last asylum, of the pillars of Stanly Abbey.

The dripping water passes through the rock-work into a large shell, the gift of a valued friend, the author of "The Pleasures of Memory;" and I add, with less hesitation, the inscription, because it was furnished by the author of "The Pains of Memory," a poem, in its kind, of the most exquisite harmony and fancy, though the author has long left the bowers of the muses, and the harp of music, for the severe professional duties of the bar. I have some pride in mentioning the name of Peregrine Bingham, being a near relation, as well as rising in character and fame at the bar. The verses will speak for themselves, and are not unworthy his muse whose poem suggested the comparisons. The inscription is placed over the large Indian shell:—

"Snatch'd from an Indian ocean's roar,

I drink the whelming tide no more;

But in this rock, remote and still,

Now serve to pour the murmuring rill.

Listen! Do thoughts awake, which long have slept—

Oh! like his song, who placed me here,

The sweetest song to Memory dear,

When life's tumultuous storms are past,

May we, to such sweet music, close at last

The eyelids that have wept!"

Leaving the small oratory, a terrace of flowers leads to a Gothic stone-seat at the end, and, returning to the flower-garden, we wind up a narrow path from the more verdant scene, to a small dark path, with fantastic roots shooting from the bank, where a grave-stone appears, on which an hour-glass is carved.

A root-house fronts us, with dark boughs branching over it. Sit down in that old carved chair. If I cannot welcome some illustrious visitors in such consummate verse as Pope, I may, I hope, not without blameless pride, tell you, reader, in this chair have sat some public characters, distinguished by far more noble qualities than "the nobly pensive St. John!" I might add, that this seat has received, among other visiters, Sir Samuel Romilly, Sir George Beaumont, Sir Humphry Davy—poets as well as philosophers, Madame de Stael, Dugald Stewart, and Christopher North, Esq.

Two lines on a small board on this root-house point the application:—

"Dost thou lament the dead, and mourn the loss

Of many friends, oh! think upon the cross!"

Over an old tomb-stone, through an arch, at a distance in light beyond, there is a vista to a stone cross, which, in the seventeenth century, would have been idolatrous!

To detail more of the garden would appear ostentatious, and I fear I may be thought egotistical in detailing so much. I shall, however, take the reader, before we part, through an arch, to an old yew, which has seen the persecution of the loyal English clergy; has witnessed their return, and many changes of ecclesiastical and national fortune. Under the branches of that solitary but mute historian of the pensive plain, let us now rest; it stands at the very extreme northern edge of that garden which we have just perambulated. It fronts the tower, the churchyard, and looks on to an old sun-dial, once a cross. The cross was found broken at its foot, probably by the country iconoclasts of the day. I have brought the interesting fragment again into light, and placed it conspicuously opposite to an old Scotch fir in the churchyard, which I think it not unlikely was planted by Townson on his restoration. The accumulation of the soil of centuries had covered an ascent of four steps at the bottom of this record of silent hours. These steps have been worn in places, from the act of frequent prostration or kneeling, by the forefathers of [pg 88] the hamlet, perhaps before the church existed. From a seat near this old yew tree, you see the churchyard, and battlements of the church, on one side; and on the other you look over a great extent of country. On a still summer's evening, the distant sound of the hurrying coaches, on the great London road, are heard as they pass to and from the metropolis. On this spot this last admonitory inscription fronts you:—

"There lie the village dead, and there too I,

When yonder dial points the hour, shall lie.

Look round, the distant prospect is display'd,

Like life's fair landscape, mark'd with light and shade.

Stranger, in peace pursue thy onward road,

But ne'er forget thy lone and last abode!"

Paper, for the purpose of writing or printing, was first manufactured in this country, according to Anderson, about the year 1598, in the reign of Elizabeth. There is reason, however, to believe, that its manufacture existed here previous to that time. John Tate is recorded to have had a paper-mill at Hertford, in the reign of Henry VII. and the first book printed on English paper, came out in 1495 or 6. It was entitled "Bartholomeus de proprietatibus rerum," and was printed on paper made by John Tate, jun.

The different paper marks are objects of some curiosity. Probably they gave the names to the different sorts, many of which names are retained, though the original marks of distinction have been relinquished. Post paper originally bore the wire mark of a postman's horn, as appears on specimens of paper of the date 1679. The fleur de lis was the peculiar mark of demy, most likely originating in France. The open hand is a very ancient mark, giving name to a sort, which though still in use, is considerably altered in size and texture.

Fool's-Cap—the name is still continued though the original design of a fool's cap is relinquished.

Pot Paper.—There were various designs of pots or drinking vessels; this paper retains its proportions and size according to early specimens, but the mark is exchanged for that of the arms of England.

The original manufacturer in this country, John Tate, marked his paper with a star of eight points, within a double circle. The device of John Tate, jun. was a wheel; his paper is remarkably fine and good.

Various other paper marks were in use, adopted most likely at the will or caprice of the manufacturer. Thus we have the unicorn and other non-descript quadrupeds, the bunch of grapes, serpent, and ox'head surmounted by a star, a great favourite; the cross, crown, globe, initials of manufacturers' names; and, at the conclusion of the 17th century and commencement of the last, arms appear in escutcheons with supporters.

The only alteration in the following is the difference of the orthography which I have made for the benefit of your readers. They are extracts from a curious manuscript, containing directions for the household of HenryVIII.

"His highness' baker shall not put alum in the bread, or mix rye, oaten, or bean flour with the same, and if detected, he shall be put into the stocks.

"His highness' attendants are not to steal any locks or keys, tables, forms, cupboards, or other furniture of noblemen's or gentlemen's houses, where he goes to visit.

"Master cooks shall not employ such scullions as go about naked, or lie all night on the ground before the kitchen fire.

"No dogs to be kept in the court, but only a few spaniels for the ladies.

"Dinners to be at ten, and suppers at four.

"The officers of his privy chamber shall be loving together, no grudging or grumbling, or talking of the king's pastime.

"The king's barber is enjoined to be cleanly, not to frequent the company of misguided women, for fear of danger to the king's royal person.

"There shall be no romping with the maids on the staircase, by which dishes and other things are often broken!

"The pages shall not interrupt the kitchen maids.

"The grooms shall not steal his highness's straw for bed, sufficient being allowed to them.

"Coal only to be allowed to the king's, queen's, and lady Mary's chambers.2

"The brewers not to put any brimstone in the ale.

"Twenty-four loaves a-day for his highness' greyhounds.

"Ordered—that all noblemen and gentlemen at the end of the session of parliament, depart to their several counties, on pain of the royal displeasure."

The following items contain nothing very remarkable, and if they did, perhaps I have copied enough already for a specimen of this ludicrous manuscript.

W. H. H.

In an old tract printed in the year 1749, it is stated that one Richard Forthave, who lived in Bishopsgate-street Without, sold and invented "a vinegar," which had a great run, and he soon became noted; and from this it may be concluded that the length of time has caused the above corruption. The article in the pamphlet is headed "Forthave's Vinegar."

W. H. H.

Philip II. of Spain, the consort of our Queen Mary, gave a whimsical reason for not eating fish. "They are," said he, "nothing but element congealed, or a jelly of water."

It is related of Queen Aterbates, that she forbade her subjects ever to touch fish, "lest," said she, with calculating forecast, "there should not be enough left to regale their sovereign."

In the reign of Henry VII. Sir Philip Calthorpe, a Norfolk knight, sent as much cloth of fine French tawney, as would make him a gown, to a tailor in Norwich. It happened, one John Drakes, a shoemaker, coming into the shop, liked it so well, that he went and bought of the same, as much for himself, enjoining the tailor to make it of the same fashion. The knight was informed of this, and therefore commanded the tailor to cut his gown as full of holes as his shears could make. John Drakes's was made "of the same fashion," but he vowed he would never be of the gentleman's fashion again.

C. F E.

The oldest conveyance of which we have any account, namely, that of the Cave [pg 90] of Macpelah, from the sons of Heth to Abraham, has many unnecessary and redundant words in it. "And the field of Ephron, which was in Macpelah, which was before Manire, the field, and the cave which was therein, and all the trees that were in the field, that were in all the borders round about, were made sure unto Abraham." The parcels in a modern conveyance cannot well be more minutely characterized.

"Will she thy linen wash and hosen darn?"

GAY.

I'm utterly sick of this hateful alliance

Which the ladies have form'd with impractical Science!

They put out their washing to learn hydrostatics,

And give themselves airs for the sake of pneumatics.

They are knowing in muriate, and nitrate, and chlorine,

While the stains gather fast on the walls and the flooring—

And the jellies and pickles fall wofully short,

With their chemical use of the still and retort.

Our expenses increase, (without drinking French wines.)

For they keep no accounts, with their tangents and sines-.

And to make both ends meet they give little assistance,

With their accurate sense of the squares of the distance.

They can name every spot from Peru to El Arish,

Except just the bounds of their own native parish;

And they study the orbits of Venus and Saturn,

While their home is resign'd to the thief and the slattern.

Chronology keeps back the dinner two hours,

The smoke-jack stands still while they learn motive powers;

Flies and shells swallow up all our every-day gains,

And our acres are mortgaged for fossil-remains.

They cease to reflect with their talk of refraction—

They drive us from home by electric attraction—

And I'm sure, since they've bother'd their heads with affinity,

I'm repuls'd every hour from my learned divinity.

When the poor, stupid husband is weary and starving,

Anatomy leads them to give up the carving;

And we drudges the shoulder of mutton must buy,

While they study the line of the os humeri.

If we 'scape from our troubles to take a short nap,

We awake with a din about limestone and trap;

And the fire is extinguished past regeneration,

For the women were wrapt in the deep-coal formation.

'Tis an impious thing that the wives of the laymen,

Should use Pagan words 'bout a pistil and stamen,

Let the heir break his head while they fester a Dahlia,

And the babe die of pap as they talk of mammalia.

The first son becomes half a fool in reality,

While the mother is watching his large ideality;

And the girl roars uncheck'd, quite a moral abortion,

For we trust her benevolence, order, and caution.

I sigh for the good times of sewing and spinning,

Ere this new tree of knowledge had set them a sinning;

The women are mad, and they'll build female colleges,—

So here's to plain English!—a plague on their ologies!

London Mag.

July 28, 1828.

And so, most tasteful and provident public, you are going out of town on Saturday next?—We envy you. Mars is gone, and Sontag is gone, and Pasta is going—and Velluti is out of voice—and they are playing tragedies at the Haymarket—and Vauxhall will never be dry again—and the Funny Club are drenched to their skins every day—and "the sweet shady side of Pall Mall" is a forgotten blessing. You will be dull in the country if this weather continue—but not so dirty as upon the Macadam. So go.

We shall stay behind, with the Duke of Wellington, to look after business. It would not do for either of us to be gadding, while Ireland, and Turkey, and Portugal want watching. The times are getting ticklish. The stocks are rising most dreadfully, as the barometer falls; and the Squirearchy are beginning to dread that the patridges will be drowned. That will be a sad drawback from the delights of a two-shilling quartern-loaf. For ourselves, we have plenty of work cut out for us, in this our abiding place. The fewer the books which are published, the more we shall have to draw upon our own genius; and the duller the season, the more vivacious must we be to put our readers in spirits. But we have consolation approaching in the shape of amusing work. Immediately that parliament is up, the newspapers will begin to lie, "like thunder," Tom Pipes would say. What mysterious murders, what heart-rending accidents, what showers of bonnets in the Paddington Canal, what legions of unhappy children dropped at honest men's doors! We have got a file of the "Morning Herald" for the last ten years;—and we give the worthy labourers in the accident line, fair notice, that if they hash up the old stories with the self-same sauce, as they are wont to do, without substituting the pistol for the razor, and not even changing the Christian name of the young ladies who always drown themselves when parliament is up, we shall take the matter into our own hands, and write a "Chapter of Accidents" that will drive these poor pretenders [pg 91] to the secrets of hemp and rats-bane fairly out of the field.—Ibid.

Man is naturally the most awkward animal that inhales the breath of life. There is nothing, however simple, which he can perform with the smallest approach to gracefulness or ease. If he walks,—he hobbles, or jumps, or limps, or trots, or sidles, or creeps—but creeping, sidling, limping, hobbling, and jumping, are by no means walking. If he sits,—he fidgets, twists his legs under his chair, throws his arm over the back of it, and puts himself into a perspiration, by trying to be at ease. It is the same in the more complicated operations of life. Behold that individual on a horse! See with what persevering alacrity he hobbles up and down from the croupe to the pommel, while his horse goes quietly at an amble of from four to five miles in the hour. See how his knees, flying like a weaver's shuttle, from one extremity of the saddle to another, destroy, in a pleasure-ride from Edinburgh to Roslin, the good, gray kerseymeres, which were glittering a day or two ago in Scaife and Willis's shop. The horse begins to gallop—Bless our soul! the gentleman will decidedly roll off. The reins were never intended to be pulled like a peal of Bob Majors; your head, my friend ought to be on your own shoulders, and not poking out between your charger's ears; and your horse ought to use its exertions to move on, and not you. It is a very cold day, you have cantered your two miles, and now you are wiping your brows, as if you had run the distance in half the time on foot.

People think it a mighty easy thing to roll along in a carriage. Step into this noddy. That creature in the corner is evidently in a state of such nervous excitement that his body is as immovable as if he had breakfasted on the kitchen poker; every jolt of the vehicle must give him a shake like a battering-ram; do you call this coming in to give yourself a rest? Poor man, your ribs will ache for this for a month to come! But the other gentleman opposite: see how flexible he has rendered his body. Every time my venerable friend on the coach-box extends his twig with a few yards of twine at the end of it, which he denominates "a whupp," the suddenness of the accelerated motion makes his great, round head flop from the centre of his short, thick neck, and come with such violence on the unstuffed back, that his hat is sent down upon the bridge of his nose with a vehemence which might well nigh carry it away. Do you say that man is capable of taking a pleasure ride? Before he has been bumped three miles, every pull of wind will be jerked out of his body, and by the time he has arrived at Roslin, he will be a dead man. If that man prospers in the world, he commits suicide the moment he sets up his carriage.

We go to a ball. Mercy upon us! is this what you call dancing? A man of thirty years of age, and with legs as thick as a gate-post, stands up in the middle of the room, and gapes, and fumbles with his gloves, looking all the time as if he were burying his grandmother. At a given signal, the unwieldy animal puts himself in motion; he throws out his arms, crouches up his shoulders, and, without moving a muscle of his face, kicks out his legs, to the manifest risk of the bystanders, and goes back to the place puffing and blowing like an otter, after a half-hour's burst. Is this dancing? Shades of the filial and paternal Vestris! can this be a specimen of the art which gives elasticity to the most inert confirmation, which sets the blood glowing with a warm and genial flow, and makes beauty float before our ravished senses, stealing our admiration by the gracefulness of each new motion, till at last our souls thrill to each warning movement, and dissolve into ecstasy and love?

People seem even to labour to be awkward. One would think a gentleman might shake hands with a familiar friend without any symptoms of cubbishness. Not at all. The hand is jerked out by the one with the velocity of a rocket, and comes so unexpectedly to the length of its tether, that it nearly dislocates the shoulder bone. There it stands swaying and clutching at the wind, at the full extent of the arm, while the other is half poked out, and half drawn in, as if rheumatism detained the upper moiety and only below the elbow were at liberty to move. After you have shaken the hand, (but for what reason you squeeze it, as if it were a sponge, I can by no means imagine,) can you not withdraw it to your side, and keep it in the station where nature and comfort alike tell you it ought to be? Do you think your breeches' pocket the most proper place to push your daddle into? Do you put it there to guard the solitary half-crown from the rapacity of your friend; or do you put it across your breast in case of an unexpected winder from your apparently peaceable acquaintance on the opposite side?

Is it not quite absurd that a man can't [pg 92] even take a glass of wine without an appearance of infinite difficulty and pain? Eating an egg at breakfast, we allow, is a difficult operation, but surely a glass of wine after dinner should be as easy as it is undoubtedly agreeable. The egg lies under many disadvantages. If you leave the egg-cup on the table, you have to steady it with the one hand, and carry the floating nutriment a distance of about two feet with the other, and always in a confoundedly small spoon, and sometimes with rather unsteady fingers. To avoid this, you take the egg-cup in your hand, and every spoonful have to lay it down again, in order to help yourself to bread; so, upon the whole, we disapprove of eggs, unless, indeed, you take them in our old mode at Oxford; that is two eggs mashed up with every cup of tea, and purified with a glass of hot rum.

But the glass of wine—can anything be more easy? One would think not—but if you take notice next time you empty a gallon with a friend, you will see that, sixteen to one, he makes the most convulsive efforts to do with ease what a person would naturally suppose was the easiest thing in the world. Do you see, in the first place, how hard he grasps the decanter, leaving the misty marks of five hot fingers on the glittering crystal, which ought to be pure as Cornelia's fame? Then remark at what an acute angle he holds his right elbow as if he were meditating an assault on his neighbour's ribs; then see how he claps the bottle down again as if his object were to shake the pure ichor, and make it muddy as his own brains. Mark how the animal seizes his glass,—by heavens he will break it into a thousand fragments! See how he bows his lubberly head to meet half way the glorious cargo; how he slobbers the beverage over his unmeaning gullet, and chucks down the glass so as almost to break its stem after he has emptied it of its contents as if they had been jalap or castor-oil! Call you that taking a glass of wine? Sir, it is putting wine into your gullet as you would put small beer into a barrel,—but it is not—oh, no! it is not taking, so as to enjoy, a glass of red, rich port, or glowing, warm, tinted, beautiful caveza!

A newly married couple are invited to a wedding dinner. Though the lady, perhaps, has run off with a person below her in rank and station, see when they enter the room, how differently they behave.—How gracefully she waves her head in the fine recover from the withdrawing curtsy, and beautifully extends her hand to the bald-pated individual grinning to her on the rug! While the poor spoon, her husband, looks on, with the white of his eyes turned up as if he were sea-sick, and his hands dangle dangle on his thighs as if he were trying to lift his own legs. See how he ducks to the lady of the house, and simpers across the fire-place to his wife, who, by this time is giving a most spirited account of the state of the roads, and the civility of the postilions near the Borders.

Is a man little? Let him always, if possible, stoop. We are sometimes tempted to lay sprawling in the mud fellows of from five feet to five feet eight, who carry the back of their heads on the extreme summit of their back-bone, and gape up to heaven as if they scorned the very ground. Let no little man wear iron heels. When we visit a friend of ours in Queen-street we are disturbed from our labours or conversation by a sound which resembles the well-timed marching of a file of infantry or a troop of dismounted dragoons. We hobble as fast as possible to the window, and are sure to see some chappie of about five feet high stumping on the pavement with his most properly named cuddy-heels; and we stake our credit, we never yet heard a similar clatter from any of his majesty's subjects of a rational and gentlemanly height—We mean from five feet eleven (our own height) up to six feet three.

Is a man tall? Let him never wear a surtout. It is the most unnatural, and therefore the most awkward dress that ever was invented. On a tall man, if he be thin, it appears like a cossack-trouser on a stick leg; if it be buttoned, it makes his leanness and lankness still more appalling and absurd; if it be open, it appears to be no part of his costume, and leads us to suppose that some elongated habit-maker is giving us a specimen of that rare bird, the flying tailor.

We go on a visit to the country for a few days, and the neighbourhood is famous for its beautiful prospects. Though, for our own individual share, we would rather go to the catacombs alone, than to a splendid view in a troop, we hate to balk young people! and as even now a walking-stick chair is generally carried along for our behoof, we seldom or ever remain at home when all the rest of the party trudge off to some "bushy bourne or mossy dell." On these occasions how infinitely superior the female is to the male part of the species! The ladies, in a quarter of an hour after the proposal of the ploy, appear all in readiness to start, each with her walking-shoes and parasol, with a smart reticule dangling from her wrist. The gentlemen, on the other hand, get off with their great, heavy Wellingtons, [pg 93] which, after walking half a mile, pinch them at the toe, and make the pleasure excursion confine them to the house for weeks. Then some fool, the first gate or stile we come to, is sure to show off his vaulting, and upsets himself in the ditch on the opposite side, instead of going quietly over and helping the damosels across. And then, if he does attempt the polite, how awkwardly the monster makes the attempt! We come to a narrow ditch with a plank across it—He goes only half way, and standing in the middle of the plank, stretches out his hand and pulls the unsuspecting maiden so forcibly, that before he has time to get out of the way, the impetus his own tug has produced, precipitates them both among the hemlock and nettles, which, you may lay it down as a general rule, are to be found at the thoroughfares in every field.

We hold that every man behaves with awkwardness when he is in love, and the want of the one is a presumption of the absence of the other. When people are fairly engaged, there is perhaps less of this directly to the object, but there is still as much of it in her presence; but it is wonderful how soon the most nervous become easy when marriage has concluded all their hopes. Delicate girl! just budding into womanly loveliness, whose heart, for the last ten minutes, has been trembling behind the snowy wall of thy fair and beautiful bosom, hast thou never remarked and laughed at a tall and much-be-whiskered young man for the mauvaise honte with which he hands to thee thy cup of half-watered souchong? Laugh not at him again, for he will assuredly be thy husband.

Love, when successful is well enough, and perhaps it has treasures of its own to compensate for its inconveniences; but a more miserable situation than that of an unhappy individual before the altar, it is not in the heart of man to conceive. First of all, you are marched with a solitary male companion up the long aisle, which on this occasion appears absolutely interminable; then you meet your future partner dressed out in satin and white ribbons, whom you are sure to meet in gingham gowns or calico prints, every morning of your life ever after. There she is, supported by her old father, decked out in his old-fashioned brown coat, with a wig of the same colour, beautifully relieving the burning redness of his huge projecting ears; and the mother, puffed up like an overgrown bolster, encouraging the trembling girl, and joining her maiden aunts of full fifty years, in telling her to take courage, for it is what they must all come to. Bride's-maids and mutual friends make up the company; and there, standing out before this assemblage, you assent to everything the curate, or, if you are rich enough, the rector, or even the dean, may say, shewing your knock-knees in the naked deformity of white kerseymeres, to an admiring bevy of the servants of both families, laughing and tittering from the squire's pew in the gallery. Then the parting!—The mother's injunctions to the juvenile bride to guard herself from the cold, and to write within the week. The maiden aunts' inquiries, of, "My dear, have you forgot nothing?"—the shaking of hands, the wiping and winking of eyes! By Hercules!—there is but one situation more unpleasant in this world, and that is, bidding adieu to your friends, the ordinary and jailor, preparatory to swinging from the end of a halter out of it. The lady all this time seems not half so awkward. She has her gown to keep from creasing, her vinaigrette to play with; besides, that all her nervousness is interesting and feminine, and is laid to the score of delicacy and reserve.

Blackwood's Magazine.

No corpse is allowed to enter the gates of Pekin without an imperial order; because, it is said, a rebel entered in a coffin during the reign of Kienlung. However, even at Canton, and in all other cities of the empire, no corpse is permitted to enter the southern gate, because the Emperor of China gets on his throne with his face towards the south.

The Chinese make their new year commence on the new moon, nearest to the time when the sun's place is in the 15th degree of Aquarius. It is the greatest festival observed in the empire. Both the government and the people, rich and poor, take a longer or shorter respite from their cares and their labours at the new year.

The last day of the old year is an anxious time to all debtors and creditors, for it is the great pay-day, and those who cannot pay are abused and insulted, and often have the furniture of their house all smashed to pieces by their desperate creditors.

On the 20th of the twelfth moon, by an order from court, all the seals of office, [pg 94] throughout the empire, are locked up, and not opened till the 20th of the first moon. By this arrangement there are thirty days of rest from the ordinary official business of government. They attend, however, to extraordinary cases.

During the last few days of the old year, the people perform various domestic rites. On one evening they sweep clean the furnace and the hearth, and worship the god of their domestic fires.

On new-year's eve, they perfume hot water with the leaves of Wongpe and Pumelo trees, and bathe in it. At midnight they arise and dress in the best clothes and caps they can procure; then towards heaven kneel down, and perform the great imperial ceremony of knocking the forehead on the ground thrice three times. Next they illuminate as splendidly as they can, and pray for felicity towards some domestic idol. Then they visit all the gods in the various surrounding temples, burn candles, incense, gilt paper, make bows, and prostrate pray.

These services to the gods being finished, they sally forth about daylight in all directions, to visit friends and neighbours, leaving a red paper card at each house. Some stay at home to receive visitors. In the house, sons and daughters, servants and slaves, all dress, and appear before the heads of the family, to congratulate them on the new year.

After new year's day, drinking and carousing, visiting and feasting, idleness and dissipation, continue for weeks. All shops are shut, and workmen idle, for a longer or shorter period, according to the necessities, or the habits, of the several parties. It is, in Canton, generally a month before the business of life returns to its ordinary channel.

February 4, is a great holiday throughout the empire. It is called Yingchun, that is, meeting the spring, to-morrow, when the sun enters the 15º of Aquarius, being considered the commencement of the spring season. It is a sort of Lord Mayor's day. The chief magistrate of the district goes forth in great pomp, carried on men's shoulders, in an open chair, with gongs beating, music playing, and nymphs and satyrs seated among artificial rocks and trees, carried in procession.

He goes to the general parade-ground, on the east side of Canton, on the following day, being Lapchun, the first day of spring, in a similar style. There a buffalo, with an agricultural god made of clay, having been paraded through the streets, and pelted by the populace, to impel its labours, is placed on the ground, in solemn state, when this official priest of spring gives it a few strokes with a whip, and leaves it to the populace, who pelt it with stones till it is broken to pieces; and so the foolish ceremony terminates. The due observance of this ancient usage is supposed to contribute greatly to an abundant year.

Is carried on to a very great extent in China. The system seems divided into two parts; one branch affording aid to those in the very inferior walks of life, and chiefly confined to very small advances; the other granting loans upon deposits of higher value, and corresponding with similar establishments in England. These are authorized by the government; but there are others, we are informed, that exist without this sanction, and are directed to the relief of the mercantile interest. These assimilate very nearly to the late project in London of an Equitable Loan Company, making advances upon cargoes and large deposits of goods.

These houses are as conspicuously indicated, by an exterior sign over the door, as our shops in England are by the three golden balls; but, whether they indicate the same doctrine of chance as to the return of property, we will not pretend to say. Three years are allowed to redeem, with a grace of three months.

In China, the laws still permit torture, to a defined extent, and the magistrate often inflicts it, contrary to law. Compressing the ancles of men between wooden levers, and the fingers of women with a small apparatus, on the same principle, is the most usual form. But there are many other devices suggested and practised, contrary to law; and in every part of the empire, for some years past, there have been many instances of suspected persons, or those falsely accused, being tortured till death ensued. From Hoopih province, an appeal is now before the emperor, against a magistrate who tortured a man to death, to extort a confession of homicide; and we have just heard, from Kwang-se province, that on the 24th of the 11th moon, one Netseyuen, belonging to Canton, having received an appointment for his high literary attainments, to the magistracy of a Heen district, in a fit of drunkenness, subjected a young man, on his bridal day, to the torture, because he would not resign the band of music which he had engaged to accompany, according to law and usage, his intended wife to his father's house. The young [pg 95] man's name was Kwanfa. He died under the torture, and the affrighted magistrate went and hanged himself.

Prisoners who have money to spend, can be accommodated with private apartments, cards, servants, and every luxury. The prisoners' chains and fetters are removed from their bodies, and suspended against the wall, till the hour of going the rounds occurs; after that ceremony is over, the fetters are again placed where they hurt nobody. But those who have not money to bribe the keepers, are in a woful condition. Not only is every alleviation of their sufferings removed, but actual infliction of punishment is added, to extort money to buy "burnt-offerings" (of paper) to the god of the jail, as the phrase is. For this purpose the prisoners are tied up, or rather hung up, and flogged. At night, they are fettered down to a board, neck, wrists, and ancles, amidst ordure and filth, whilst the rats, unmolested, are permitted to gnaw their limbs! This place of torment is proverbially called, in ordinary speech, "Te-yuk," a term equivalent to the worst sense of the word "hell."

It is well known that the Chinese consider their walled towns in the same light as fortifications are regarded in Europe, and disallow foreigners entering them, excepting on special occasions. But there is no law against walking in the suburbs. Usage has, however, limited the Europeans in China to very small bounds. Some persons occasionally violate them, and attempt a longer walk. Once round the city walls has frequently been effected, but always at the risk of a scuffle, an assault and battery, from the idle and mischievous among the native population. On former occasions, some of the foreign tourists have returned to the factories relieved of the burden of their watches and clothes. An English baronet was once, on his passage round, robbed of his watch, and stripped either almost, or entirely naked.

A few days ago, a party of three started at six o'clock in the morning, and performed the circuit at about eight, with impunity. The distance round the walls they estimated to be nine miles. A few days afterwards, two persons set off in the evening for a walk under the city walls; but they were not so fortunate. They were violently assaulted by a rabble of men and boys, the former of whom pursued them with bludgeons, brickbats, and stones, which not only inflicted severe contusions, but really endangered their lives. The two foreigners were obliged to face about, and fight and run alternately the distance of several miles.

We, who know the hostile feelings of the population, are not surprised at the occurrence, and rather congratulate the tourists that they effected their escape so well. We notice the affair to put others on their guard; and (as the Chinese say) if they should get into a similar scrape, they cannot blame us for not warning them of their danger.

"A snapper-up of unconsidered trifles."

SHAKSPEARE.

One of the subjects for confirmation at a bishop's recent visitation, on being asked by the clergyman to whom she applied for her certificate of qualifications, what her godfathers and godmothers promised for her, said, with much naiveté, "I've a yeard that they promised to give me hafe a dozen zilver spoons, but I've never had 'em though."

The real portrait of a fine lady, wife to one of the ancient and noble family of the Fanes, Earls of Westmoreland, drawn by her husband, and inscribed in old characters upon a wall of a room in Buxton Place, a seat belonging to the noble family, near Maidstone, in Kent.—Taken from Mist's Journal.

"Shee feared God, and knew how to serve him; Shee assigned times for hir devotions and kept them; She was a perfect wife and a true friend, and shee joyed most to affect those nearest and dearest unto me; She was still the same: ever kind and never troublesome; oft preventing my desires, disputing none; providently managing all was mine; living in apparence above my state; yet advanced it; Shee was of a great spirit, sweetly tempered; of a sharp wit, without offence; of excellent speech, blest with silence; of a cheerfull temper modestly governed; of a brave fashion to win respect to daunt boldness; pleasing to all of hir sex; entyre with few, delighting in the best; ever avoiding all places and persons in the honours blemished; and was as free from doing ill as giving the occasion: Shee dyed as she lived, well and blessed; in hir greatest extremity most patient, sending up hir pure soule with many zealous prayers and hymnes to hir maker; powring forth hir passionate heart with affectionate streams of love to hir"—

"Husband" should have followed, but tradition tells us that by this time his grief swelled to such a height that he could not proceed any further.

T. H.

At the recent sale of a provincial theatre and its appurtenances, one article was to be included in the purchase, of which a short lease is by no means desirable—a new drop.

Who are so fond of harmony among themselves, have a great dislike to concord as applied to their enemies, and find even a disagreeable association in the very sound of the word, as the following anecdote will exemplify:—Among the illuminations for the last peace, were some of a very grand description, and on the door of a foreign ambassador in London, the words "Peace and Concord" figured at full length in characters of flame. "What say you, Mounsier, Conquered!" exclaimed an honest sailor, to whom a stander-by was explaining the mystic words; "shiver my timbers, who ever dared to call us 'Conquered' yet?" and so saying, was proceeding to extinguish the unlucky blaze, when a civil explanation, to which British bravery is ever ready to yield, restored Peace, and allowed Concord to continue.

Lord Dorset used to say of a very goodnatured, dull fellow, "'Tis a thousand pities that man is not illnatured! that one might kick him out of company."

The Englishmen at Paris find fault with the French roast beef; the Frenchmen in London complain of the British brandy.

The English who visit Paris, imagine that the tavern-keepers have served in the cavalry, as they are so expert in making a charge.

A foreigner inquiring the way to a friend's lodging, whom he said lived at Mr. Bailey's, senior, was shown to the Old Bailey, by a Bow-street officer. When he entered the court he imagined that it was his friend's levee.

A certain bishop declared one day, that the punishment used in schools did not make boys a whit better, or more tractable; it was insisted that whipping was of the utmost service, for every one must allow it made a boy smart.

"C'est la Soupe," says one of the best of proverbs, "qui fait le Soldat;" "It is the soup that makes the soldier." Excellent as our troops are in the field, there cannot be a more unquestionable fact, than their immense inferiority to the French in the business of cookery. The English soldier lays his piece of ration beef at once on the coals, by which means, the one and the better half is lost, and the other burnt to a cinder. Whereas six French troopers fling their messes into the same pot, and extract a delicious soup, ten times more nutritious than the simple Rôti could ever be.

The son-in-law of a chancery barrister having succeeded to the lucrative practice of the latter, came one morning in breathless ecstasy to inform him that he had succeeded in bringing nearly to its termination, a cause which had been pending in the court of scruples for several years. Instead of obtaining the expected congratulations of the retired veteran of the law, his intelligence was received with indignation. "It was by this suit," exclaimed he, "that my father was enabled to provide for me, and to portion your wife, and with the exercise of common prudence it would have furnished you with the means of providing handsomely for your children and grand-children."

It is related, that Fuseli, the celebrated artist, when he wished to summon Nightmare, and bid her sit for her picture, or any other grotesque or horrible personations, was wont to prime himself for the feat by supping on about three pounds of half-dressed pork-chops.

An infant was brought for baptism into a country church. The clergyman, who had just been drinking with his friends a more than usual quantum of the genial juice, could not find the place of the baptism in his ritual, and exclaimed, as he was turning over the leaves of the book, "How difficult this child is to baptize!"

St. Jerome says, that there is no book so dull, but it meets a suitable dull reader. "Nullus est imperitus scriptor, qui lectorem non inveniat."

Footnote 1: (return)

from an exquisite lithograph by J. Goldicutt.

Footnote 2: (return)

Hence it was found necessary for the pages and servants to run about to warm themselves with different diversions before going to bed.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD. 143, Strand, (near Somerset-House.) London: Sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.